Abstract

This research examines the awareness of evidence based practices by the public organizations that fund services in the North American Quitline Consortium (NAQC). NAQC is a large, publicly funded, goal-directed “whole network,” spanning both Canada and the U.S., working to get people to quit smoking. Building on prior research on the dissemination and diffusion of innovation and evidence based practices, and considering differences between network ties that are homophilous versus instrumental, we found that awareness of evidence based practices was highest for quitline funders that were strongly connected directly to researchers and indirectly to the network administrative organization, controlling for quitline spending per capita and decision making locus of control. The findings support the importance of maintaining instrumental (a technical-rational argument) rather than homophilous ties for acquisition of evidence based practice knowledge. The findings also offer ideas for how public networks might be designed and governed to enhance the likelihood that the organizations in the network are better aware of what evidence based practices exist.

Collaboration within a network of cooperating organizations has been an especially important strategy for addressing the public's most pressing health and human services needs, such as mental health, homelessness, child and youth services for low income families, HIV/AIDS services, and emergency response. In particular, networks have become important mechanisms for building capacity to recognize complex health and social problems, systematically planning for how such problems might best be addressed, mobilizing and leveraging scarce resources, facilitating research on the problem, and delivering needed public services (Provan and Milward, 1995; Graddy and Chen, 2006; Agranoff, 2007; Wells and Weiner, 2007; Moynihan, 2009; Leischow et al., 2010; Saz-Carranza and Ospina, 2011).

To achieve these gains, however, critical information must flow between and among the organizations involved in the network. When addressing complicated health needs, for example, information about practices that are known to be effective must be disseminated to those who actually utilize the practices (Ferlie et al., 2005). In this regard, networks have been found to be essential for the dissemination of knowledge leading to adoption of innovation (c.f. Powell et al., 1996; Valente, 1996, Rogers, 2003; Greenhalgh et al., 2004). New approaches to methods of practice may, of course, be generated from a variety of sources, including research, experimentation, and mandate. However, a critical mechanism for transmission of ideas is through the network of connections maintained by individuals and organizations that are immersed in a field of study and practice. What is not clear, however, is which network ties are most useful in facilitating this process.

The research presented here is an examination of the network ties of organizations operating within a single, publicly funded, goal-directed whole network (Provan, Fish, and Sydow, 2007). The network, the North American Quitline Consortium, operates in the U.S. and Canada and provides telephone-based services to people trying to quit smoking. Our study examines the flow of information among the many organizations that comprise the quitline network, and the relationship between these information flows and the awareness by organizational decision makers of those tobacco cessation practices that are both evidence-based and recommended as being a “best practice.” It is these practices that are considered by tobacco control experts to be effective. While internal factors such as organizational culture, capacity, professionalism, and influences on individual decision makers are likely to affect decisions to actually adopt and implement new practices (cf. Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Denis et al., 2002; Ferlie et al., 2005), our focus on awareness of these practices is critical since it is a prerequisite to adoption and implementation (Rogers, 2003). Thus, for developing a clear understanding of why practices get adopted and implemented, it is first essential to know why some organizations are aware of these practices and others are not (Fitzgerald et al., 2002).

This research contributes to a deeper understanding of the role that network ties in general, and specific types of network ties in particular, play in transferring knowledge about those practices that have either been shown through scientific research to be most effective, or have specifically been recommended by a highly credible national organization as being effective. We refer here to both types of practices as being evidence based, although we recognize that the nature of evidence for each type may be different.

Most research on knowledge flow through networks has focused on the value of network ties for transferring knowledge that enables organizations to become more innovative themselves. Thus, the information transferred is most valuable for what March (1991) has referred to as “exploration,” where new ideas are created. But many fields, such as in health services or public policy (cf. Boaz and Pawson, 2005; Jennings and Hall, 2012), organizations are not themselves major sources of innovation, but instead, depend on others for determining what works best. In such settings it thus becomes especially important to know if and how ties to other individuals and organizations facilitate the transfer of information about practices that have been determined to be effective. This is consistent with March's (1991) concept of “exploitation” in organizational learning, where the basic idea already exists but may be adopted and perhaps embellished on by others.

In view of the cost and complexity of developing and maintaining network relationships (cf. Huxham and Vangen, 2005), it is of important theoretical significance to understand which types of ties are most relevant for enhancing awareness of practices, especially for those known to be effective. This knowledge also contributes to an understanding of how such networks; especially where all participants operate within a common service domain, might be designed and governed so that organizations in the network can enhance their awareness of practices that work, ultimately leading to their adoption and implementation.

BACKGROUND

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. and causes over 400,000 deaths per year (CDC, 2010), yet it has been difficult to lower the incidence of smoking, which now stands at about 19.3% of the adult population in the U.S. (CDC Vital Signs, 2011). Research on behavioral and pharmacological approaches to treat tobacco dependence has resulted in a number of evidence-based treatments to help smokers quit. Among the behavioral approaches, interventions by healthcare providers and group counseling have been effective, with recent meta-analyses demonstrating the effectiveness of proactive quitline intervention (Fiore et al., 2008). This evidence, coupled with the potential for quitlines to treat larger numbers of smokers than other methods, contributed to a dramatic increase in tobacco treatment quitlines in the last 20 years (Anderson and Zhu, 2007). The first US quitline was started in California in 1992, and based on the efficacy of this and other early adopters, combined with a major tobacco settlement agreement to the states in 1998, quitlines in the U.S. and Canada proliferated rapidly (Provan, Beagles and Leischow, 2011).

With a few exceptions, quitlines consist of two organizations; a funder, usually in a public health department in every state/province, and a service provider that may serve multiple quitlines. Our focus is on the public funder entity as the representative of each quitline. While the provider organizations actually counsel the smokers, provide drug therapy, etc., it is the funders that are ultimately responsible for how much can be spent on quitline services in their state/province, what specific services can or should be offered, and what entity should provide these services. While funders need not understand the details of the services they fund, they do need to be aware of what services are available and their efficacy, in order to make decisions about which services should be adopted. Such knowledge may come from a variety of sources, including the provider. These public funder organizations thus are responsible for what services get provided, while contracting out the provision of services to provider organizations that may be public, nonprofit, or for-profit. Quitlines represent an example of the “hollow state” (Milward and Provan, 2000), where government determines what services are needed and affordable, and then “contracts out” the services it might otherwise provide directly (Brown, Potoski and Van Slyke, 2006). As with government contracting, it is also up to the funder to monitor the provider to ensure that contractual obligations are met (Klijn, 2003).

Quitlines provide both direct services, through telephone counseling, and access to other needed services, such as medication. Surveys have shown smokers are four times more likely to use a quitline than to seek face-to-face counseling (Zhu et al., 2002). Every state in the U.S. (50 states plus three territories) and all ten Canadian provinces now have access to a toll-free tobacco quitline, with all quitlines in the U.S. linked via one number (1-800-QUIT-NOW). Quitline organizations have also spread to other parts of the world, with 29 European countries currently having quitlines, including one that also coordinates and promotes quitline activities (see the European Network of Quitlines at www.enqonline.org).

The complexity of helping smokers quit makes the process of decision-making regarding which treatments to provide, to whom, under what circumstances, and for what duration, a major challenge. Because the problem is complex, it is one that can benefit by close communication and collaboration among the organizations that fund and provide quitline services. In particular, a translational knowledge network among quitline organizations is likely to foster greater awareness of practices that are known to be effective, based on both research evidence and the recommendations of national organizations. Assuming resource availability and favorable influences over internal decision practices, the awareness of such practices is thus an important and necessary first step in the five stage decision process discussed by Rogers (2003) for innovation diffusion.

Unfortunately, but perhaps not surprisingly, even though there is substantial evidence available as to which quitline practices are effective for quitting smoking, the awareness and ultimate implementation of these practices is highly uneven across quitlines. The gap between what is known based on scientific evidence and what is actually implemented has been documented and researched in many areas including health care (Drake, Goldman, Leff et al., 2001; Ferlie et al., 2005), management (Rousseau, 2006), and public policy (Bax, de Jong, and Koppenjan, 2010; Maynard, 2006). However, there is far less known about the sources of information about these practices (see Jennings and Hall, 2012, for an exception), and especially, the role that different types of network ties play in the practice dissemination process. While network ties are certainly not the only way in which evidence based practice information is learned, it is a major source of such information (Greenhalgh et al., 2004), and thus, it is important to understand more deeply the role that networks play. From a practical perspective, networks might then be designed and governed in ways that facilitate establishment and maintenance of those particular types of network ties that make it easier for participating organizations to acquire new knowledge. For theory, research on the topic would help to develop a more precise understanding of the impact of network ties of different types on the flow of critical knowledge to public organizations. We argue that awareness of evidence based practices can be explained by the connections maintained by quitline funder organizations to other key individuals and organizations that comprise the broader quitline network, but that not all types of ties are necessarily equal in their capacity to transfer this information.

CONCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT

The role of social networks for learning and innovation has been studied in a number of contexts (see review by Brass et al., 2004). Through work on the topic over the past decade or so, network scholars have by now established the importance of examining the role of networks for organizational learning, moving beyond the notion that innovative ideas are generated within organizational hierarchies (Ahuja, 2000). For instance, in their early research on network learning in biotechnology, Powell and colleagues (1996: 118) noted: “Knowledge creation occurs in the context of a community, one that is fluid and evolving rather than rigidly bound or static. Sources of innovation do not reside exclusively inside firms; instead, they are commonly found in the interstices between firms, universities, research laboratories, suppliers, and customers.”

For the most part, the research on networks and knowledge has focused on the flow of knowledge through network relationships and on the innovation that presumably follows. In general, organizations with critical ties to other organizations in the same field learn more, and thus, are likely to be more innovative than organizations that are less well-connected. While networks have been shown to be essential for the dissemination of new ideas, especially in such areas as biotechnology (Powell et al., 1996) and health (Greenhalgh et al., 2004; Wipfli, Fujimoto and Valente, 2010; Mascia and Cicchetti, 2011) where information is complex and new ideas are often not “home grown,” non-network sources of information are certainly possible. For instance, in a recent study of the use of evidence based practices for decisions about policies, Jennings and Hall (2012) found that the main source of such information was “internal agency staff.” However, their research focused primarily on the acquisition of evidence based practice information from a broad range of external sources, with the most frequent source being “comparable agencies in other states,” an indicator of network involvement with similar actors. While we recognize that evidence based practices for smoking quitlines can be attained from different sources, like scientific journals, the literature on the flow of new information and ideas is highly consistent in demonstrating the importance of external ties to outside individuals and organizations. Network ties seem especially important for the managers of public agencies, like quitline funders, where key decision makers may not have the time or ability to read through scientific journals or attend specialized conferences. In addition, as noted earlier, most of the organizational network literature has focused on the value of network ties for the transfer of ideas that can foster innovation, which involves exploration. Our focus here is on the spread of ideas developed by others, which involves exploitation.

Consistent with the literature on innovations (Rogers, 2003), especially in a health care context (Denis et al., 2002; Greenhalgh et al., 2004; Wipfi et al., 2010; Mascia and Cicchetti, 2011), the awareness of practices is likely to be influenced by the flow of knowledge among individuals and organizations within a common service domain related to a specific health problem or service. To take advantage of these knowledge flows, organizations must develop and maintain network ties to others who are themselves knowledgeable about practices (i.e., within the whole network), in contrast to having ties to those outside the community where such knowledge is likely to be low. While this basic argument is by now well-established regarding innovation/exploration (Powell et al., 1996), the question of which specific network ties might be most advantageous for learning about new knowledge that involves exploitation has not been studied, particularly within the context of a whole, goal-directed network designed specifically to enhance the flow of knowledge among members. In this context, it seems highly unlikely that all types of network connections will have the same effect on the transfer of information, although which types of ties might be most beneficial is not clear.

Assuming that organizations have a basic desire and need to know what practices work best, regardless of whether or not they ultimately implement a particular practice, there are mixed views as to why organizations might form ties with certain types of partners and not others to acquire such knowledge. In the broad literature on interorganizational relations and networks a number of explanations have been offered for relationship formation (cf. Oliver, 1990, Kilduff and Tsai, 2003, and Brass et al., 2004 for reviews), but two fundamental reasons are either relational or technical/rational (cf. Ibarra, 1992; Hite and Hesterly, 2001). Especially when considering relational network ties between organizations rather than individuals, homophily has been found to be highly important (cf. Rowley et al., 2005), as organizations build and strengthen ties to other organizations that are similar to themselves. In contrast, the rational/technical argument is based on developing ties that are instrumental to task accomplishment. Organizations seek out others for acquiring knowledge primarily, but not necessarily exclusively, from those entities that are known to possess the desired knowledge, regardless of whether or not the source of that knowledge is similar to the focal organization. Thus, the relationship is clearly more instrumental than ties based on homophily.

Despite their different rationales, each basic argument has the potential to explain the acquisition of new knowledge. On one hand, in the case of homophily, organizational boundary spanners will feel more comfortable talking to and sharing information with the managers of organizations that provide similar services and deal with the same sorts of challenges. On the other hand, by connecting directly to those who are known to have knowledge about new practices, the rational/technical argument is potentially more efficient. Ties to many other similar organizations may provide a broader pool of potential knowledge, with an emphasis on what has actually worked in practice. But maintaining and managing these relations can be time consuming and complex since the range of issues addressed may be quite broad, resulting in less focused interactions about new practices. In addition, many of these homophilous partner organizations may only have knowledge about those practices that they themselves have adopted, and not those that are new or evidence based.

While organizations often maintain both types of relationships, network theory has not specified whether evidence based practice knowledge is more readily transfered through one type of tie or another. Rather, the predominant focus in the general organizational network literature has been on tie strength, or relationship intensity, to explain the transfer of different types of information. The focus has also primarily been on relations within organizations and project teams rather than across organizations in a whole network context. Regarding tie strength, strong, trust-based ties have been shown to be best for clarifying existing knowledge, or exploitation (Lechner, Frankenberger, and Floyd, 2010), while weaker, less trust-based ties are best for transfering new and more complex tacit knowledge involving exploration (cf. Hansen, 1999; Reagans and McEvily, 2003). Past network research has not, however, addressed which types of organizational ties (homophilous or rational/technical) might be more effective in the transfer of new knowledge related to exploitation, in either public or private contexts.

To shed light on these theoretical issues, we examine whether ties to certain types of network partners may be more advantageous than others for enhancing practice awareness. To do this, we study a range of network ties, first focusing on ties to those individuals and organizations that are known to be especially knowledgeable about evidence-based practices but who do not actually provide any services (the technical/rational argument), and then examine ties to the other funder and provider organizations within the quitline community (the homophily argument). Since past research by Hansen (1999) and Reagans and McEvily (2003), Letchner et al. (2010) and others has demonstrated that relationship intensity matters for complex knowledge flow, at least within rather than across organizations, we focus not simply on the existence of network ties, but only on those relationships that are on-going and important to the focal organization, rather than occasional and superficial. This more intensive tie approach is consistent with our focus on evidence based practice awareness, which involves knowledge exploitation rather than exploration.

HYPOTHESES

Consistent with the technical/rational perspective, in tobacco quitlines, one key source of information about the efficacy of practices is the tobacco control researchers who either conduct the actual studies leading to evidence based knowledge or who are most familiar with the research being done on the topic by other colleagues. When quitline funder organizations are directly and intensively connected to these researchers, especially those who are themselves most embedded in the quitline community through their connections to other quitlines, we argue that awareness of evidence based practices will tend to be high. Strong network ties to the most well-connected researchers will facilitate the diffusion of information about these practices to those who may ultimately adopt and implement them.

A second important source of information that is consistent with the technical/rational perspective is NAQC's network administrative organization. As previously discussed, a key role and purpose of the NAO is to ensure that knowledge about effective practices gets disseminated to the quitlines so they can ultimately be implemented to help reduce the incidence of smoking. In this regard, the NAO works closely with researchers and is actively engaged in mechanisms to disseminate new knowledge, including online research presentations, teleconferences, work groups, and individual consultations. While nearly all quitline organizations interact at least marginally with the NAO, it is mainly through intensive ties that a quitline organization can learn about evidence based practices. The idea that the NAO should be an important conveyer of information about quitline practices is also supported by Greenhalgh et al. (2004) in their review of literature on innovation diffusion in health services organizations. They argued that a key source of information about innovations is through “champions,” one of which may be the network facilitator (pp. 602-603, 609). This is similar to the role of network broker (Burt, 2004).

As discussed above, one important way in which organizations acquire information is through their ties to other, similar organizations that share similar tasks, challenges, and demands for producing effective outcomes. For quitline funder organizations, this means establishing information ties to other quitline organizations, including ties to both other funders and other providers. Based on homophily arguments, in which individuals and organizations with similar backgrounds and characteristics tend to cluster together, quitline funders may seek out information and ideas on a range of issues based on the fact that they are engaged in similar activities and have the same basic goal (Fitzgerald et al., 2002) as the organizations in other quitlines. As a result of this interaction, especially when the relationship is strong and frequent, quitline funders are likely to gain knowledge about practices that they may not be aware of.

Finally, it is likely that quitline funders get information about practices through their own provider organization, but mainly when their provider organization is itself connected to a key source of information. In particular, when a funder's provider is strongly connected to the NAO, it will receive information on practices, just as the funder would if strongly and directly connected to the NAO. In this case, however, the connection is indirect. The provider that receives information about evidence based practices from NAQC's NAO must then convey this information to the funder, if the funder is to be aware of the practice. We consider this to be a technical-rational argument for developing a network tie. The connection between the funder's provider and the NAO is for the instrumental reason of acquiring knowledge about practices and the funder's provider connection is instrumental in that it is a business relationship based on the contract established by the funder to provide a set of services.

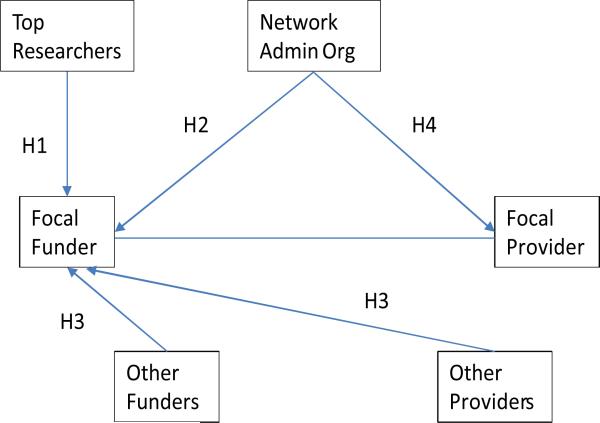

Based on these ideas, we will test the following four hypotheses concerning a quitline organization's network ties:

Hypothesis 1: The greater the number of intensive information ties a quitline funder organization has to the most highly embedded researchers in the tobacco control network, the more likely it will be aware of evidence-based practices.

Hypothesis 2: Quitline funder organizations that have intensive information ties to the network's administrative organization will more likely to be aware of evidence-based practices than those quitline funders that do not have these ties.

Hypothesis 3: The greater the number of intensive information ties a quitline funder organization has to other funders and providers, the more likely it will be aware of evidence-based practices.

Hypothesis 4: The greater the number of intensive information ties a quitline funder's provider organization has to the network's administrative organization, the more likely the quitline's funder will be aware of evidence-based practices (i.e., indirect ties).

Figure 1 provides an overview of the quitline relationships described above, indicating which relationship reflects each of the four hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Model of Quitline Relationships and Hypotheses

RESEARCH METHODS

Research Setting

The context of our work is the North American Quitline Consortium. NAQC was established in 2004 and is the network administrative organization (NAO) for the 63 quitlines in the US and Canada, providing coordination and governance of the network in the absence of any hierarchy (Provan and Kenis, 2008). In particular, NAQC was set up to improve access to and use of quitline services, primarily through enhancing the flow of practice and research-based knowledge on effective quitline practices (Anderson and Zhu, 2007). NAQC currently has a full time executive director plus four staff people, including a research director, and an advisory council of quitline members to develop strategic direction. NAQC is a “whole network” since it is bounded by membership, is formally governed, and has clear goals surrounding both the provision of smoking cessation services using a quitline methodology and the dissemination of knowledge related to improving both the efficacy and efficiency of those services.

As previously noted, each quitline consists of a public funder entity and a service provider organization. In some cases (n=13), the provider only serves one state/province. In other cases (n=7), a provider serves multiple states/provinces. The largest service provider is a for-profit entity that, at the time of our data collection, contracted with 18 state quitlines.

Data Collection

Data were collected from all quitline organizations during the summer and early fall of 2009. The total initial population was 63 funder entities and 20 service providers plus the NAQC NAO. Depending on organization size, data were collected from 1 to 5 funder respondents, although the vast majority of funders had 3 or fewer respondents (53/60 = 88.3%). Respondents were selected carefully and systematically. NAQC's NAO maintains a database of primary contacts for each quitline organization. Each primary contact was contacted by NAQC staff during the recruitment phase of the project, and asked to submit a list of all individuals within their organization who were involved with decision making for the quitline. “Involved” was defined as “playing a key and direct role in, or contributing information to, the decision making process for implementing new practices for the quitline.” In a few cases, individuals who had been identified by the organization's primary contact indicated to the research team that they were not, in fact, involved with or central to decision making for the quitline. In those cases, the individuals were removed from the list of respondents and not pursued as a potential responder.

Primary data were collected using a web-based survey developed expressly for this project but based on reliable methods and measures utilized previously by the lead author and colleagues (self reference). In addition, questions and methods were pre-tested on a “working group” of key quitline members who agreed to provide initial feedback. After extensive follow-up efforts using email and telephone, our final results included completed surveys from 186 of 277 individual respondents (67.1% response rate), representing 85 of 94 quitline component organizations (90.4% response rate) plus the NAQC NAO, and from 60 of the 63 quitline funders (95.2% response rate).

Our unit of analysis is the quitline, represented by the funder organization. We focused on the funder for a number of reasons. First, as noted earlier, it is the funder that is ultimately responsible for which services are offered (if only for reasons of funding availability), thus making awareness of evidence-based practices important. This is true even though actual decisions about which practices to adopt and implement may be done jointly with the provider. Second, we had complete data on network ties and awareness of evidence-based practices from 60 of the 63 quitlines, but only partial data from a number of the larger, multi-quitline provider organizations. In particular, one of the largest providers did not complete the practice questions since its management felt strongly that because the funder organization initiates the contract and pays the bills, it is the funder who decides what practices to use. We used this logic as well in our decision to focus on the funder. Third, many of the providers served multiple states and provinces, making it difficult to disentangle the effects of the role of these providers relative to one of its quitlines versus another. Each U.S. state (and territory) and each Canadian province is represented by a quitline funder organization, each with its own separate budget and network connections, making it possible to compare meaningfully across quitlines and thus, test our hypotheses. Finally, while providers represent public, nonprofit, and for-profit entities, all quitlines are predominantly funded by a public entity, thereby minimizing variation based on sector differences. Hence, our analytical focus is the funder organization as the representative of each quitline.

Measures

Network relationships were based on receipt of financial, general management, service delivery, or promotion/outreach information. Respondents were presented with a list of all quitline funders and provider organizations. For each, respondents were asked to indicate if they received information from that organization (i.e., indegree, coded 0 if no tie) regarding which of the four types of information, and at what level of relationship intensity in terms of frequency and importance (scored on a 1 to 3 scale). The highest level of intensity (level 3) referred to “ongoing interactions or a link that is very important to your quitline organization.” Only responses scored at this highest level of intensity were utilized in the final analysis reported here. 1 Because a link of any of the four information types was highly correlated with a link of any other type, we did not distinguish among types of ties, simply coding whether or not any of the four types was reported, and if so, at what level of intensity. If any respondent in an organization having multiple respondents indicated a relationship existed with another organization, the relationship was counted, based on the presumption that this individual had information on network connections that others in the organization did not (Maurer and Ebers, 2006).

Using these data, a series of network variables were constructed to test the four hypotheses. Consistent with the survey data and the hypotheses, six distinct types of network ties were constructed, all based on indegree (information received) centrality and all based on the highest level of intensity of involvement. The network measures are: quitline funder ties to the NAO (coded 0 or 1), provider ties to the NAO (0, 1), the number of funder ties to other funders and other providers (i.e., other than their own service provider), and the number of funder ties to the 10 most highly connected tobacco control researchers (from a drop-down list of 42 tobacco control researchers previously identified). For this last measure, each quitline respondent was allowed to list up to five researchers but responses were weighted so no quitline organization could score more than a single point for any one researcher and no more than five points total. Our logic for using only the top ten researchers is that these individuals were identified by the funders as the most knowledgeable and legitimate sources of research information on quitline practices. This meant considering ties to those researchers identified by at least 8 other funders as a key source of practice knowledge.

Data on the dependent variable, awareness of evidence-based practices related to quitting tobacco through quitlines, was measured by asking respondents to respond to and score a list of 23 quitline practices that were determined by a workgroup of practitioners and researchers involved with NAQC to be effective in both attracting smokers to receive help (“reach”) and to actually get them to reduce or quit smoking (efficacy). Once data were collected, we then refined this list. First, to determine research evidence, we conducted a thorough examination of the treatment practice research literature in tobacco control. Based on this review, 14 practices were found to have at least one scientific article demonstrating the efficacy of that practice. Five other practices were also retained as they were recommended by the Centers for Disease Control as having significant practice-based, but not scientific evidence. Finally, two of the 23 practices were dropped due to the absence of either research or significant practice-based evidence and two other practices were dropped from analysis since they applied to the US quitlines only (regarding Medicaid and health insurance). Thus, our research overcomes concerns discussed in the public policy literature that evidence based practices are often based on rather dubious or ambiguous evidence (Boaz and Pawson, 2005). Respondents were asked to indicate whether they were aware of each of the practices listed (i.e., knowledge dissemination). Our dependent variable is a count of the number of practices the key respondents of each quitline funder organization reported being either aware of or unaware of for each of the 19 practices (mean unawareness score = 3.05).

A funder organization was considered to be aware of a practice if at least one key informant acknowledged being aware of that practice. Because the respondents in any one funder organization work closely on quitline operations, and all respondents were pre-identified as being decision makers, awareness by one of these individuals would likely constitute awareness by others in the organization, especially as practices were considered for adoption. This logic was reinforced by selective follow-up interviews and discussions with the working group of quitline decision makers we assembled to check our methods and measures. As a final check, we recalculated responses for awareness, this time using the criterion that at least half the respondents at each funder had to agree. We then correlated this measure with the single respondent responses. Responses differed very little from the single respondent approach (r = .82), providing further evidence of the validity of our method.

Two control variables were also used in the analysis. The first is quitline spending per smoker in the state/province (r = .98 with spending per capita). Consistent with research by Cohen and Levinthal (1990), Szulanski (1996) and others, quitline funders with more resources available for spending on smokers will have higher “absorptive capacity,” and thus, would be in a stronger position to both seek out and eventually implement a broader range of new practices than their low spending counterparts. They can also hire better trained professionals who might know about many practices regardless of the network involvement of their organization.

Our second control variable is the locus of control for decisions about adoption and implementation of practices. As mentioned earlier, quitlines consist of a pair of organizations – a funder and a service provider. The funder, a government entity, has a network tie to a provider organization through its contract for the services needed for smokers in its state or province. However, despite the fact that the funder controls the budget and decides which organization should actually receive the quitline contract, the funder does not necessarily make the decisions as to which specific services should be adopted and implemented. In some cases, the decision rests solely with the funder. But in other cases, the decision is shared or decided by the provider. This is consistent with the idea of the “hollow state” (Milward and Provan, 2000) in government contracting where government agencies act primarily as a conduit for distribution of public funds for services deemed as necessary, but retain little actual control over service level decisions. Drawing on this logic, it is reasonable to conclude that when the decision to adopt and implement a quitline practice is typically made by the funder, then the funder must be aware of what these practices are and whether or not they work, based on research evidence. Conversely, when the decision rests with the service provider, there is far less incentive or need for the funder to be aware of the practices being considered. Thus, the network connection between funder and provider may not be balanced as to which partner exerts the most influence in the relationship.

For locus of control, respondents from quitline funders were asked to report the extent to which their organization was typically the primary decision maker for decisions related to practice adoption, as opposed to the decision being made by the provider organization, or shared. Responses were based on a Likert-type 5-point scale ranging from 1 (funder decides) to 5 (service provider decides), with 3 = decision is shared equally. The mean score was used as the organization's response when there were multiple responses for a funder. Table 1 reports the means, standard deviations, and correlations for all the variables used in the study.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for All Variablesa

| mean | s.d. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Unawareness of EBP | 3.050 | 2.931 | - | ||||||

| 2 Ties to top researchers | 2.467 | 1.682 | −.424 | - | |||||

| 3 Funder tie to NAO | 0.317 | 0.469 | −.246 | .282 | - | ||||

| 4 Provider tie to NAO | 0.850 | 0.360 | −.362 | .034 | −.015 | - | |||

| 5 Ties to other funders/providers | 2.540 | 2.520 | −.163 | .278 | .163 | .075 | - | ||

| 6 Locus of decision control | 2.503 | 0.715 | .071 | .216 | .027 | −.064 | −.001 | - | |

| 7 Spending/smoker | 2.629 | 3.165 | −.204 | .030 | −.149 | .147 | −.092 | −.015 | - |

n = 60

If r>.21, p<.10; If r> .26, p<.05; If r>.33, p<.01

Abbreviations: EBP = evidence based practices, NAO = network administrative organization

FINDINGS

The data were first analyzed descriptively using Ucinet 6 (Borgatti, Everett, and Freeman, 2002), which uses network matrices to calculate relationships among the organizations that comprise the whole network. Using NetDraw, which is the plotting routine for Ucinet 6, we developed a plot of the overall structure of the NAQC network based on information flows for all quitline funders, providers, researchers, and the NAQC network administrative organization. The plot revealed the very high centrality of the NAO, high centrality of the largest funders and several provider organizations, and some large differences in the relative connectedness of the researchers to the quitline organizations (plot is available upon request from the lead author).

The main analysis tests the four hypotheses, as reported in Tables 2 and 3. Because the dependent variable, practice awareness, is a count variable that does not meet the distribution requirements of either OLS regression or a Poisson distribution, we used negative binomial regression, which allowed us to test and control for over-dispersion in the dependent variable (Long and Freese, 2006). To be consistent with the assumptions of a negative binomial distribution, which is highly skewed to the left, the dependent variable was reverse coded so that a zero reflects awareness of all 19 evidence based practices and values above zero reflects the number of the 19 practices that a funder is unaware of. Thus, support for the hypotheses would be demonstrated by a significant negative coefficient in the regression models.

Table 2.

Negative Binomial Regression Results Explaining Lack of Quitline Funder Awareness of Evidence Based Practices: N=60

| Unawareness – Full Model | level of significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coefficient | s.e. | log odds | %* | ||

| QL spending/smoker | −0.069 | 0.046 | 0.934 | −6.63% | |

| Locus of decisions | 0.200 | 0.171 | 1.221 | 22.11% | |

| Ties to top researchers | −0.221 | 0.085 | 0.802 | −19.83% | .009 |

| Funder tie to NAO | −0.382 | 0.292 | 0.682 | −31.76% | |

| Provider tie to NAO | −0.699 | 0.312 | 0.497 | −50.31% | .025 |

| Ties to other funders & providers | −0.025 | 0.055 | 0.976 | −2.43% | |

| Constant | 1.953 | 0.530 | 7.046 | 604.63% | .001 |

| Alpha | 0.461 | 0.195 | .001 | ||

| Chi Square | 19.12 | ||||

| Prob>Chi Square | .0040 | ||||

| Pseudo R Square | .0704 | ||||

| Log Likelihood | −126.25 | ||||

| BIC | 285.25 | ||||

% = For every unit increase (or decrease) in the independent variable, the odds of a quitline funder being unaware of an additional practice increases (decreases) by x%.

Table 3.

Negative Binomial Regression Results Explaining Lack of Quitline Funder Awareness of Evidence Based Practices: US Only, N=50

| Unawareness – Full Model | level of significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coefficient | s.e. | log odds | %* | ||

| QL spending/smoker | −0.067 | 0.051 | 0.935 | −6.47% | |

| Locus of decisions | 0.228 | 0.238 | 1.256 | 25.56% | |

| Ties to top researchers | −0.202 | 0.098 | 0.817 | −18.30% | .039 |

| Funder tie to NAO | −0.324 | 0.353 | 0.723 | −27.67% | |

| Provider tie to NAO | −0.824 | 0.384 | 0.439 | −56.11% | .032 |

| Ties to other funders & providers | −0.050 | 0.086 | 0.951 | −4.88% | |

| Constant | 1.979 | 0.746 | 7.233 | 623.32% | .008 |

| Alpha | 0.591 | 0.254 | .001 | ||

| Chi Square | 14.66 | ||||

| Prob>Chi Square | .023 | ||||

| Pseudo R Square | .066 | ||||

| Log Likelihood | −103.89 | ||||

| BIC | 239.08 | ||||

% = For every unit increase (or decrease) in the independent variable, the odds of a quitline funder being unaware of an additional practice increases (decreases) by x%.

Table 2 reports findings for the full sample of 60 quitlines for which we had funder organization data, while Table 3 reports findings for the 50 U.S. quitlines only. We felt that it was important to separately examine the US quitline funders for two reasons. The first is the more obvious reason that not only are the U.S. and Canada different culturally and with different forms of government at state and federal levels, but especially, because the two systems of health services are quite different (c.f. Lasser, Himmelstein, and Woolhandler, 2006). Second, scores for our control variable measure, locus of control over decisions, were significantly different (p<.05) when comparing quitlines in each of the two countries. In the U.S., the funders clearly made most practice adoption decisions (mean = 2.396 with none of the 50 funders reporting provider dominated decisions). In contrast, in Canada, the providers were much more involved in the practice adoption decision process (mean = 3.033, with only 3 of 10 funders reporting that they were most influential in the process).

Overall, the findings offer support for hypotheses 1 and 4, while hypotheses 2 and 3 were not supported. In all models, neither of the two control variables were significant. Specifically, neither total quitline spending per smoker (in the state or province) nor the locus of control for adoption decisions were significant explanatory factors for the awareness of evidence based practices by quitline funders.

As predicted by hypothesis 1, those quitline funder organizations that were well-connected to tobacco control researchers who were themselves most active in the overall quitline network, were more likely to be aware of evidence-based practices than quitlines with few ties to these researchers (p=.009). In general, ties to researchers reflects connections to those who are most likely to be aware of what practices work to help people to gain access to quitline services and to actually treat them effectively. However, rather than merely being connected to any tobacco control researcher (a simple count of a funder's ties to any of the researchers was not significant when tested), it was connections to the researchers who were themselves most involved with quitline organizations that mattered. Alternatively stated, it is the information ties to those tobacco control researchers who are most structurally embedded (Granovetter, 1985) in the whole network that explains how quitline funders acquire practice knowledge.

Another critical source of information for evidence-based quitline practices from a technical-rational perspective is the network administrative organization. As noted earlier, and consistent with ideas developed by Provan and Kenis (2008) on whole network governance, this entity was set up expressly for developing, coordinating, and facilitating the flow of information among NAQC members. While nearly all quitline organizations are connected to the NAO, many of these ties are not intensive, limiting the capacity of the NAO to exchange useable information about research-based practices. Our findings offer mixed support for the idea that strong quitline ties to the NAO are beneficial for enhancing awareness of practices. On one hand, surprisingly, hypothesis 2 was not supported (although in the predicted direction), demonstrating that quitline funders that are intensively and directly tied to the NAO are generally no more likely than those that are more weakly connected to enhance their awareness of evidence-based practices.

On the other hand, hypothesis 4, which focuses on the role of the funder's provider organization, was supported (p=.025). The hypothesis is based on the assumption that when a funder works with a provider that is itself strongly tied to the NAO, key practice information will be passed from the NAO to the provider. This information is then passed on to the funder indirectly, through the provider, but not directly by the NAO. The likely reason for this indirect knowledge flow path may simply be a practical one. That is, it is easier and quicker for NAO staff to work closely with a subset of 20 unique provider entities which can then disseminate needed knowledge to their contracted funders, rather than trying to work closely with over 60 funders. In addition, it may make more sense for the NAO to direct the flow of relevant information concerning practices through those entities that are actually providing services, rather than just funding them. Of course the funders still must know about these practices if they are to fund them. Our findings indicate that it is the funders who contract with providers who are themselves intensively connected to the NAO that have an information advantage in the network over those funders whose providers are not so strongly tied to the NAO.

Hypothesis 3 received no support for either the full sample or in the US only sample of quitlines. Consistent with a homophily argument, we predicted that quitline funders intensively connected to other quitline organizations; namely, to other funders and to providers other than their own, would have greater access to knowledge about evidence-based practices since many of these organizations would themselves know about these practices through their own ties to researchers and the NAO and through their own practice-based experience. We predicted that practice information might flow readily to the funder through these channels since they shared similar experiences and challenges. However, this homophily argument was not supported. Having many ties, even intensive ones, to many other similar organizations within the network, appears to have little impact on practice awareness, as opposed to being strongly connected directly to well-connected tobacco control researchers, and indirectly, to the NAO. Unlike other funders and providers, these two groups have more direct and immediate access to information about evidence based practices (i.e., the technical/rational argument). Other funders and providers certainly do have practice knowledge that may be useful, but this knowledge may be based more on their own particular experiences. For funders, it simply appears to be more efficient to acquire practice knowledge directly through researchers or through their own provider (assuming it is strongly connected to the NAO), rather than through other funders and providers who themselves acquire this knowledge through others.

As a further test of our arguments, we broke down the 19 practices into two categories. As discussed previously, the 19 practices we considered in our full models were based either on research evidence or on the fact that they were recommended by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) as being a “best practice.” Because the CDC recommended practices had no identifiable research evidence, we considered these 5 practices separately from the 14 practices for which research evidence was available and ran separate regression models on each set of practices. Our findings for those practices with actual research evidence were nearly identical to the full model, with significant support for hypotheses 1 and 4. However, for the 5 CDC recommended practices, only hypothesis 1, reflecting ties to well-connected researchers, was supported and only barely, at p= .055.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The findings presented here provide support for the general idea that awareness of evidence-based health practices is enhanced through network ties. In view of what is already known about the value of networks for transferring information, this is perhaps not a surprising finding. However, the extent to which practice knowledge is actually transferred within a bounded, goal-directed network like NAQC, and which types of ties are most useful, is not clear. Our findings demonstrate that not all types of network ties have the same outcome. In particular, we found that while strong ties to similar organizations (i.e., homophily) are relatively common and undoubtedly result in some receipt of information about practices, it is only through strong ties (direct and indirect ties, depending on the information source) to known sources of evidence based knowledge (i.e., the technical-rational argument) that results in enhanced awareness of this knowledge. These findings were strongest for those practices that were based on actual scientific evidence, rather than those that were simply “recommended.” Based on these findings, we can draw some conclusions that contribute to both theory and practice.

For one thing, the study has contributed to a deeper understanding of how strong, intensive ties facilitate the flow of knowledge within a network comprised of organizations operating within a common service domain. Our research focused on information about effective quitline practices, which is knowledge designed for implementation, consistent with March's (1991) idea of exploitation in organizational learning. In contrast, much of the research on knowledge flows in networks has focused on their value for exploration, which involves the creation of new knowledge through innovation (cf. Hansen, 1999; Reagans and McEvily, 2003). That research, as well as work by Granovetter (1973), Burt (2004), and others, has also focused on the benefit of weak, rather than strong ties for acquiring knowledge that is new, complex, and tacit. Our findings provide evidence that strong ties can be especially effective in conveying existing knowledge, like evidence based practices, but that not all strong ties are alike in terms of their effectiveness in conveying this knowledge in a way that results in active awareness. Strong homophilous ties may provide an effective way of sharing general information about operations that is similar across quitlines; however, our work shows that evidence based practice knowledge is generally not conveyed through these ties. Instead, organizations that need this information appear to seek out more dissimilar, but perhaps more reliable sources. Thus, a more technical-rational rationale for acquiring new practice knowledge seems to prevail. In our study, this meant connections to the NAO, albeit only indirect ties through a funder's specific provider organization, and direct ties to well-connected researchers.

Our research also contributes to the burgeoning literature on evidence based practices. As noted earlier, most of this literature, whether in public policy (Bax, de Jong, and Koppenjan, 2010; Jennings and Hall, 2012; Maynard, 2006), medicine and health (Denis et al., 2002; Drake, Goldman, Leff et al., 2001; Ferlie et al., 2005), or business management (Rousseau, 2006), has focused on practice implementation, especially on why practices known to have scientific evidence have been weakly or not at all implemented. Until recently (Jennings and Hall, 2012), there has been very little research on the sources of information used by public agencies to acquire this practice knowledge. Our study was not an attempt to document all possible sources of information used by quitline funders. Rather, we built on ideas of Rogers (2003), Greenhalgh et al. (2004), and others who have argued for the importance of network relations for information dissemination and diffusion. Like Jennings and Hall, we affirmed the value of external sources for practice information. But beyond that, we demonstrated the specific importance of network ties, while indicating clear differences in the impact of different types of network ties on practice awareness, a conclusion not previously recognized in the evidence based practice literature.

In addition, the fact that our findings were strongly supported only when focusing on practices based on actual research-based evidence, rather than on practice-based evidence recommended by a key national organization (in this case, the CDC), is consistent with observations made by Greenhalgh et al. (2004) in their comprehensive review of the literature and helps to refine theorizing on the role of networks in information dissemination. Specifically, they note that while previous research supports the importance of a centralized network governance structure for the spread of innovations in a healthcare context, there seems to be an understudied tension between the dissemination of “proactively developed innovations” through centralized means and the diffusion of good ideas (consistent with Rogers, 2003)“which spread informally and in a largely uncontrolled way.” The results of our study highlight this tension in that practices with actual research-based evidence do seem to be disseminated through a centralized network structure (i.e., through the NAO and top researchers) while the practice based innovations in our study appear to be spreading much more informally. While it seems reasonable to conclude that network ties are important for the general dissemination and diffusion of knowledge among organizations, our study reinforces the idea that the two processes are not the same. Future research needs to consider these differences in greater depth, carefully considering both the different types of network ties that might spread new ideas as well as the range of evidence that may exist for different practices.

While our study focused only on a single network, we believe that the research also provides a deeper understanding of the relative benefit to organizations of being involved, at least regarding the flow of information, in a formally constructed, goal-directed, whole network. Such benefits are consistent with the conclusions of a recent analysis of tobacco control leadership in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (Leischow et al, 2010). Even though our work primarily focused on the impact of a funder's ego-centric network ties on its practice awareness, these ties, and the funders themselves, were embedded in a broader whole network context. In this regard, the role of a formal governance entity; specifically, NAQC's NAO, was especially important (cf. Moynihan, 2009; Provan et al., 2011). The NAO's main role was to bring together the many funders, providers, and researchers that were involved with quitline activities, encouraging interactions across the network and facilitating learning, especially for enhancing quitline efforts to get people to stop smoking. How or if evidence based practice knowledge would have been shared had a formalized NAQC network and its NAO not existed is impossible to say. However, without the NAO or an alternative whole network governance mechanism, we can speculate that critical information would likely be shared less widely. Under such circumstances, homophilous ties might play a greater role and researchers might themselves be less knowledgeable about what others in the network are doing. In addition, the flow of evidence based knowledge might be quite different in a network comprised of organizations that were not operating in a common service domain, and thus, would have very different information needs about practices.

Finally, our research has implications for practice, especially for public entities, like those studied here, that choose to contract out for provision of services. Contracting entities should be aware, not only of the services they are currently funding, but also, about new practices that have been shown to be effective. Our research has demonstrated how these entities might best learn about evidence based practices through network ties that are themselves embedded in a whole network. Such knowledge would mean that funders could improve the return on investment for services they are paying for by maximizing the likelihood that only practices shown to be effective are implemented by contracted providers. Doing so would limit some of the problems inherent to contracting out discussed in the public management literature (cf. Brown et al., 2006).

This research is, of course, not without limitations. First, although our express intent was to focus on awareness of evidence based practices, awareness does not necessarily result in adoption or full implementation. Adoption and implementation are likely to depend on internal organizational factors like resources, capacity, and managerial politics and preferences (cf. Boaz and Pawson, 2005). A second potential limitation of the research is the focus on funders as the quitline representative. We provided what we believe is a strong case for why our approach was appropriate including use of locus of decisions regarding practices as a control variable. However, due to the limitations of our data, we cannot be sure if funder or provider awareness is ultimately more critical in the final decision to adopt and then implement. Third, since our data are cross-sectional, the causal relationship between our independent and dependent variables is not clear. We have assumed, consistent with the literature on networks and dissemination of knowledge, that network relationships lead to greater practice awareness. But it may be that awareness, based on alternative sources of information like reading journals or attending conferences, may result in a greater desire and willingness to seek out information from other organizations. Fourth, while we drew heavily on qualitative data when formulating our research ideas and measures, we did not collect qualitative data to supplement our quantitative findings. In particular, it would be highly beneficial to examine in a more in-depth way exactly how each quitline funder acquires practice knowledge through its network ties as well as through other means (cf. Denis et al., 2002). Finally, our analysis was restricted due to network size. Although NAQC is a large network, examining 60 quitlines meant that we could only include a modest number of independent and control variables in our models. This is a common problem with research on a single, bounded network, but it does not mean that the research should not be done. Hopefully, future research will be conducted in other publicly funded and organized health services settings to test the reliability of our findings. Ideally, studies could be done on a large number of networks, although such research would be costly and time consuming.

Overall, despite some limitations, the findings presented here extend our understanding of the importance of network involvement for the dissemination and awareness of critical knowledge; in this case, evidence based practices for quitting smoking. The research also adds to the limited literature on whole, goal-directed networks providing publicly funded services (cf. recent research by Herranz, 2008; Moynihan, 2009; and Saz-Carranza and Ospina, 2011), how they operate, and their effectiveness, as well as the role that individual organizations play in whole networks that are organized around a single complex problem. In the case reported here, that problem, reducing the incidence of smoking, is a significant health concern, not only in the US and Canada, but also, throughout the world.

Acknowledgments

Work on this paper was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01CA128638-01A11). Additional support was provided by Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG - CA 023074). The authors would like to thank Jessie Saul and Gregg Moor for their invaluable assistance on the project.

Footnotes

Data on “weak” (Granovetter, 1973) and moderate intensity ties were not utilized here for two key reasons. First, although we have data on weak ties, since we were unable to confirm network relationships between partners, we were concerned that weak tie findings were not reliable. Thus, we developed matrices only for the moderate and intensive level relationships. Second, the transmission of evidence based practice information involves what March (1991) has called the exploitation of knowledge, rather than exploration, which involves creation of new knowledge. As discussed by Lechner et al. (2010) and others, knowledge for exploitation is best transferred through strong network ties, while weaker ties are best for exploration. Third, nearly every quitline organization (both funders and providers) had at least moderately intensive ties to the NAO based on their network participation. The NAO routinely deals with nearly all quitline organizations at moderate intensity for transmission of information, acquiring data for their annual survey, etc. Hence, there would be almost no variance on two of our independent variables if low or moderate intensity ties were used (for funder-NAO ties and provider-NAO ties), which would make meaningful analysis impossible. Thus, the link that is most relevant for our analysis is not the more routine connections to the NAO, but the intensive ties, where there is on-going interaction between the funder and/or provider and the NAO that allows for the meaningful transmission of critical practice information. This is the focus of our analysis.

Contributor Information

Keith G. Provan, Eller College of Management and School of Government & Public Policy 1130 E. Helen Street, McClelland Hall University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721 (kprovan@eller.arizona.edu)

Jonathan E. Beagles, University of Arizona, jbeagles@email.arizona.edu

Liesbeth Mercken, Maastricht University, liesbeth.mercken@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Scott J. Leischow, University of Arizona, sleischow@azcc.arizona.edu

REFERENCES

- Agranoff Robert. Managing Within Networks. Georgetown Univ. Press.; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja Gautam. Collaboration networks, structural holes, and innovation: A longitudinal study. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2000;45:425–455. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Christopher M., Zhu Shu-Hung. Tobacco quitlines: Looking back and looking ahead. Tobacco Control. 2007;16(Suppl I):i81–i86. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boaz Annette, Pawson Ray. The perilous road from evidence to policy: Five journeys compared. Journal of Social Policy. 2005;34:175–94. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti Steve P., Everett Martin G., Freeman Lin C. Ucinet for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. Analytic Technologies; Harvard: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bax Charolotte, de Jong Martin, Koppenjan Joop. Implementing evidence-based policy in a network-setting: Dutch road safety policy in a shift from a home to an away match. Public Administration. 2010;88:871–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brass Daniel J., Galaskiewicz Joseph, Greve Henrich R., Tsai Wenpin. Taking stock of networks and organizations: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Journal. 2004;47:795–817. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Trevor L., Potoski Matthew, Van Slyke David M. Managing public service contracts: Aligning values, institutions, and markets. Public Administration Review. 2006;66:323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Burt Ronald. Brokerage and closure: An introduction to social capital. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Health, United States, 2009. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville (MD): 2010. [Google Scholar]

- CDC Vital Signs Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011 Sep; http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/?source=govdelivery.

- Cohen Wesley M., Levinthal Daniel A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1990;35:128–152. [Google Scholar]

- Denis Jean-Louis, Hébert Yann, Langley Ann, Lozeau Daniel, Trottier Louise-Hélène. Explaining diffusion patterns for complex health care innovations. Health Care Management Review. 2002;27:60–73. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake Robert E., Goldman Howard H., Stephen Leff H, Lehman Anthony F., Dixon Lisa, Mueser Kim T., Torrey William C. Implementing Evidence-Based Practices in Routine Mental Health Service Settings. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:179–182. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie Ewan, Fitzgerald Louise, Wood Martin, Hawkins Chris. The (non) spread of innovations: The mediating role of professionals. Academy of Management Journal. 2005;48:117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore Michael C., Jaén Carlos R., Baker Timothy B., Bailey William C. Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2008. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald Louise, Ferlie Ewan, Wood Martin, Hawkins Chris. Interlocking interactions, the diffusion of innovations in health care. Human Relations. 2002;55:1429–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Graddy Elizabeth A., Chen Bin. Influences on the size and scope of networks for social service delivery. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2006;16:533–552. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter Mark. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;78:1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter Mark. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology. 1985;91:481–510. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh Trisha, Robert Glenn, MacFarlane Fraser, Bate Paul, Kyriakidou Olivia. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82:581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen Morten T. The search-transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1999;44:82–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hite Julie M., Hesterly William S. The evolution of firm networks: From emergence to early growth of the firm. Strategic Management Journal. 2001;22:275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Herranz Joaquin., Jr. The multisectoral trilemma of network management. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2008;18:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham Chris, Vangen Siv. Managing to Collaborate. Routledge; London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra Herminia. Homophily and differential returns: Sex differences in network structure and access in an advertising firm. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1992;37:422–447. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings Edward T., Jr., Hall Jeremy. Evidence-based practice and the use of information in state agency decision making. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2012;22 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kilduff Martin, Tsai Wenpin. Social networks and organizations. Sage; London: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn Erik-Hans. Governing networks in the hollow state: Contracting out, process management, or a combination of the two? Public Management Review. 2003;4:149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lasser Karen E., Himmelstein David U., Woolhandler Steffie. Access to care, health status, and health disparities in the United States and Canada: Results of a cross-national population-based survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1300–1307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner Christoph, Frankenberger Karolin, Floyd Stephen W. Task contingencies in the curvilinear relationships between intergroup networks and initiative performance. Academy of Management Journal. 2010;53:865–889. [Google Scholar]

- Leischow Scott J., Luke Douglas A., Mueller Nancy, Harris Jenine K., Ponder Paris, Marcus Stephen, Clark Pamela I. Mapping U.S. government tobacco control leadership: Networked for success? Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12:888–894. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott Long, J., Freese Jeremy. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. 3rd ed. Stata Press; College Station, TX: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- March James G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science. 1991;2:71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mascia Daniele, Cicchetti Americo. Physician social capital and the reported adoption of evidence-based medicine: Exploring the role of structural holes. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;72:798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer Indre, Ebers Mark. Dynamics of social capital and their performance implications: Lessons from biotechnology startups. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2006;51:262–292. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard Rebecca. Presidential address: Evidence-based decision making: What will it take for decision makers to decide? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2006;25:249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Brinton Milward, H., Provan Keith G. Governing the hollow state. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2000;10:359–380. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan Don P. The network governance of crisis response: Case studies of incident command systems. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2009;19:895–915. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver Christine. Determinants of interorganizational relationships: Integration and future directions. Academy of Management Review. 1990;15:241–265. [Google Scholar]

- Powell Walter W., Koput Kenneth W., Smith-Doerr Laurel. Interorganizational collaboration and the locus of innovation: Networks of learning in biotechnology. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1996;41:116–145. [Google Scholar]

- Provan Keith G., Beagles JE, Leischow Scott J. Network formation, governance, and evolution in public health: The North American Quitline Consortium case. Health Care Management Review. 2011;36:315–326. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31820e1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provan Keith G., Kenis Patrick. Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2008;18:229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Provan Keith G., Brinton Milward H. A preliminary theory of interorganizational network effectiveness: A comparative study of four community mental health systems. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1995;40:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Provan Keith G., Fish Amy, Sydow Jorg. Interorganizational networks at the network level: A review of the empirical literature on whole networks. Journal of Management. 2007;33:479–516. [Google Scholar]

- Reagans Ray, McEvily Bill. Network structure and knowledge transfer: The effects of cohesion and range. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2003;48:240–267. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers Everett M. Diffusion of innovations. Free Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau Denise M. Is there such a thing as “evidence based management”? Academy of Management Review. 2006;31:256–269. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley Timothy, Baum Joel A. C., Greve Henrich R., Rao Hayagreeva, Shipilov Andrew V. Time to break up: Social and instrumental antecedents of firm exits from exchange cliques. Academy of Management Journal. 2005;48:499–520. [Google Scholar]

- Saz-Carranza Angel, Ospina Sonia M. The behavioral dimension of governing interorganizational goal-directed networks: Managing the unity-diversity tension. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2011;21:327–365. [Google Scholar]

- Szulanski Gabriel. Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal. 1996;17(special issue):27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Valente Tomas W. Network models of the diffusion of innovations. Hampton Press; Cresskill: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wells Rebecca, Weiner Bryan J. Adapting a dynamic model of interorganizational cooperation to the health care sector. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64:518–543. doi: 10.1177/1077558707301166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipfli Heather L., Fujimoto Kayo, Valente Tomas W. Global tobacco control diffusion: The case of the framework convention on tobacco control. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1260–1266. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Shu-Hung, Tedeschi Gary, Anderson Christopher M., Rosbrook Bradley, Byrd Michael, Johnson Cynthia E., Gutiérrez-Terrell Elsa. Telephone counseling as adjuvant treatment for nicotine replacement therapy in a real-world setting. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31:357–63. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]