Abstract

Background

Trust in physicians is an essential part of therapeutic relationships. Complications are common after colorectal cancer procedures, but little is known of their effect on patient-surgeon relationships. We hypothesized that unexpected complications impair trust and communication between patients and surgeons.

Methods

We performed a population-based survey of surgically diagnosed stage III colorectal cancer patients in the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results registries for Georgia and Metropolitan Detroit between August 2011 and October 2012. Using published survey instruments, we queried subjects about trust in and communication with their surgeon. The primary predictor was the occurrence of an operative complication. We examined patient factors associated with trust and communication then compared the relationship between operative complications and patient-reported trust and communication with their surgeons.

Results

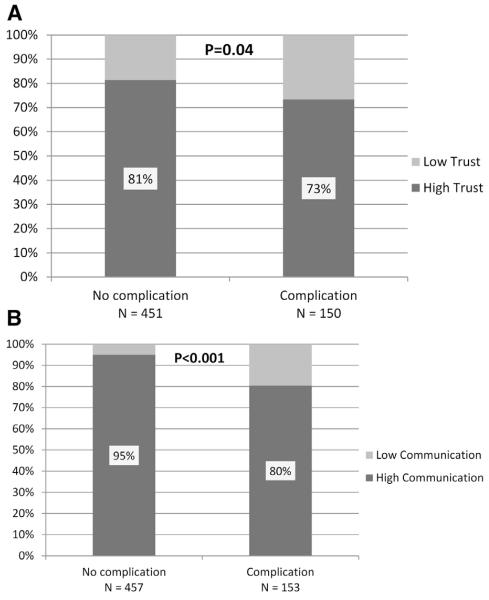

Among 622 preliminary respondents (54% response rate), 25% experienced postoperative complications. Those with complications were less likely to report high trust (73% vs 81%, P = .04) and high-quality communication (80% vs 95%, P < .001). Complications reduced trust among only 4% of patient-surgeon dyads with high-quality communication, whereas complications diminished patients’ trust in 50% with poorer communication (P < .001). After controlling for communication ratings, we found there was no residual effect of complications on trust (P = .96).

Conclusion

Most respondents described trust in and communication with their surgeons as high. Complications were common and were associated with lower trust and poorer communication. However, the relationship between complications and trust was modified by communication. Trust remained high, even in the presence of complications, among respondents who reported high levels of patient-centered communication with their surgeons.

Patients’ trust in their physicians and the quality of communication between patients and doctors are key determinants of adherence to recommended courses of treatment1-6 and satisfaction with care and outcomes.7,8 Although trust has a central role in all medical care-giving relationships, its importance in surgery may be amplified by the invasiveness and risk involved in major operative procedures and the requirement that patients cede to their surgeons control of the critical aspect of therapy—the operation itself.9,10 Patients’ trust in the relationship with their surgeon may be particularly strained, however, in the setting of major cancer operations, given the frequency and severity of complications.

Operative resection for colorectal cancer (CRC), for example, incurs frequent morbidity due to adverse events and major complications, which result in significant morbidity and cost.11-13 CRC is the third most common cancer in men and women in the United States,14 and more than a quarter of a million colon resections are performed each year.15 Among operations in the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, colectomy accounts for 10% of general operations, but 25% of the complications—more than double the share held by any other operation—and colectomy is the most common cause of postoperative death and prolonged hospitalization.12

In this context, we sought to understand the associations between operative complications and patient-reported levels of trust in and communication with their surgeon after CRC resections. We also investigated the possibility that effective communication might modify the effects of complications on trust. We draw on data from a detailed, population-based cohort survey of patients with stage III CRC, which provides rich insights into patient-reported aspects of their interactions in cancer therapy.

METHODS

Study population

We identified all patients with pathologic stage III colon or rectal cancer between August 2011 and October 2012 through the population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results cancer registries of Metropolitan Detroit, Michigan, and the State of Georgia. All patients in the registry who were 21–99 years of age at diagnosis were eligible for recruitment within 3–12 months after operative resection for CRC. This study is nested within a broader survey in which we sought to understand patient decision-making around adjuvant therapy and was limited to patients with stage III disease because of pragmatic limitations of funding and sample-size considerations.

Data collection

We identified physicians of record from pathology reports and notified them of our intention to contact the study subjects. Allowing a brief response period for the physicians, subjects were then contacted by mail and invited to participate in the survey. After initial patient and physician contact, 55 (4.5%) patients were excluded because of either stage 4 disease, change in diagnosis based on final histology, or residence outside of the catchment area. A modified version of the Dillman approach was used for recruitment, including sequential follow-up steps in the event of nonresponse.16 Upon receipt of surveys, extensive data checks for logic, errors, and omissions were performed.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Michigan, Wayne State University, Emory University, the State of Michigan, and the State of Georgia. The research information sheet in the survey packet included a statement of the study purpose, risks and benefits of participation, and subject confidentiality. A waiver of documentation of informed consent was obtained from all participating institutional review boards.

Measures

The analyses in this study focus on four comparisons: (1) the association between operative complications and patient-reported trust in the surgeon; (2) the association between surgical complications and patient-reported communication with the surgeon; (3) among respondents who experienced a complication, the reported change in trust due to the surgeon’s management of the complication; and (4) the modifying effect of patient-reported communication on the relationship between management of complications and change in trust. The primary outcomes, trust and communication, were assessed by a series of questions (10 for trust, 5 for communication), each with five-point Likert response scales, derived from validated instruments (Appendix). Each set of questions was scaled to create continuous measures of trust and communication, which were dichotomized in accordance with their treatment by other investigators.2 Respondents with aggregate responses in the top two categories (an arithmetic mean of 4 points or greater) were considered “high” and those with lower scores (average responses less than 4) were considered “low.” As a sensitivity analysis, we also repeated the primary analyses using the continuous scales and found little to no change in results.

For this study, trust was defined as “the optimistic acceptance of vulnerability,”3 in which the patient, in a position of uncertainty and illness, believes the physician will care for his or her best interests. Toward this concept, the survey items for the assessment of trust in surgeons were derived from the Wake Forest physician trust scale,3,5 a 10-item unidimensional instrument, which evaluates fidelity (two questions), competence (three questions), honesty (one question), and global trust (four questions). The scale has been validated among general medical patients, and has high construct validity and internal reliability (α = .93).3

Doctor-patient communication was assessed by subscales of the Patient Reactions Assessment.8 Each subscale contains five items. The Affective subscale evaluates the physician’s value, understanding, and respect for the patient, and the Information subscale measures the provision and understanding of explanations about disease, testing, and treatment. The scale has been found to have high internal consistency (α = .91) and correlates with measures of effective provider-patient relationship.8 The specific questions were adapted from Kahn et al.2

The primary predictor for this study was the occurrence of one or more postoperative complications. This measure was determined by response to the query, “Did you have any unexpected complications after your surgery?” Additional covariates included self-reported demographics (age at diagnosis, sex, race and marital status), socioeconomic status (based on measures defined by the National Health Interview Survey, including measures of education and income), type of health insurance, overall health status (patients were asked to rate their overall health in one of five categories, as shown in Tables I and II) and comorbidities. Respondents with missing data were treated as a separate category for income because of the relatively large number of nonresponders for this item.

Table I.

The association of respondent characteristics and postoperative complications

| No complications, n = 467 (75) | Complications, n = 155 (25) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, y | .27 | ||

| <50 | 81 (17) | 20 (13) | |

| 50–64 | 162 (35) | 53 (34) | |

| 65–74 | 106 (23) | 46 (30) | |

| 75+ | 118 (25) | 36 (23) | |

| Sex | .64 | ||

| Male | 248 (53) | 84 (54) | |

| Female | 216 (46) | 67 (43) | |

| Race | .03 | ||

| White | 329 (70) | 123 (79) | |

| Black | 100 (21) | 27 (17) | |

| Other | 32 (7) | 3 (2) | |

| Marital status | .02 | ||

| Married/partnered | 279 (60) | 108 (70) | |

| Not married/partnered | 181 (39) | 43 (28) | |

| Education | .18 | ||

| Less than high school | 79 (17) | 19 (12) | |

| High school | 117 (25) | 33 (21) | |

| Some college | 158 (34) | 54 (35) | |

| College grad+ | 107 (23) | 47 (30) | |

| Annual income | .32 | ||

| <$20,000 | 76 (16) | 23 (15) | |

| $20,000–$49,000 | 128 (27) | 44 (28) | |

| $50,000–$89,000 | 103 (22) | 30 (19) | |

| ≥$90,000 | 65 (14) | 32 (21) | |

| Missing | 95 (20) | 26 (17) | |

| Insurance | .053 | ||

| Private | 197 (42) | 60 (39) | |

| Medicare | 211 (45) | 78 (50) | |

| Medicaid | 11 (2) | 8 (5) | |

| None | 45 (10) | 7 (5) | |

| Overall health | .67 | ||

| Poor | 29 (6) | 8 (5) | |

| Fair | 69 (15) | 18 (12) | |

| Good | 173 (37) | 57 (37) | |

| Very good | 126 (27) | 50 (32) | |

| Excellent | 64 (14) | 19 (12) | |

| Comorbidities | <.001 | ||

| None | 138 (30) | 23 (15) | |

| 1 | 139 (30) | 49 (32) | |

| ≥2 | 190 (41) | 83 (54) |

Data shown are N (%). P values are derived from χ2 tests. Proportions may not add to 100% because of rounding and missing data.

Table II.

The association of respondent characteristics and trust and communication

|

Low trust, N = 124 (21) |

High trust, N = 477 (79) |

P value |

Low communication, N = 53 (9) |

High communication, N = 557 (91) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, y | .93 | .96 | ||||

| <50 | 18 (15) | 82 (17) | 8 (15) | 93 (17) | ||

| 50–64 | 44 (35) | 168 (35) | 20 (38) | 194 (34) | ||

| 65–74 | 31 (25) | 117 (25) | 12 (23) | 138 (25) | ||

| 75+ | 31 (25) | 113 (24) | 13 (25) | 138 (25) | ||

| Sex | .40 | .15 | ||||

| Male | 61 (49) | 262 (55) | 24 (45) | 306 (55) | ||

| Female | 59 (48) | 213 (45) | 29 (55) | 245 (44) | ||

| Race | .69 | .44 | ||||

| White | 88 (71) | 355 (74) | 40 (75) | 402 (72) | ||

| Black | 25 (20) | 92 (19) | 12 (23) | 114 (20) | ||

| Other | 9 (7) | 26 (5) | 1 (2) | 34 (6) | ||

| Marital status | .40 | .11 | ||||

| Married/partnered | 40 (32) | 176 (37) | 24 (45) | 193 (35) | ||

| Not married/partnered | 81 (65) | 297 (62) | 28 (53) | 356 (64) | ||

| Education | .93 | .94 | ||||

| Less than high school | 18 (15) | 76 (16) | 9 (17) | 87 (16) | ||

| High school | 28 (23) | 116 (24) | 11 (21) | 135 (24) | ||

| Some college | 45 (36) | 162 (34) | 19 (36) | 191 (34) | ||

| College grad+ | 32 (26) | 119 (25) | 14 (26) | 138 (25) | ||

| Annual income | .71 | .04 | ||||

| <$20,000 | 19 (15) | 75 (16) | 15 (28) | 83 (15) | ||

| $20,000–$49,000 | 39 (31) | 130 (27) | 16 (30) | 153 (27) | ||

| $50,000–$89,000 | 23 (19) | 106 (22) | 5 (9) | 127 (23) | ||

| ≥$90,000 | 17 (14) | 79 (17) | 7 (13) | 90 (16) | ||

| Missing | 26 (21) | 87 (18) | 10 (19) | 104 (19) | ||

| Insurance | .96 | .08 | ||||

| Private | 51 (41) | 198 (42) | 14 (26) | 240 (43) | ||

| Medicare | 58 (47) | 220 (46) | 33 (62) | 250 (45) | ||

| Medicaid | 3 (2) | 16 (3) | 1 (2) | 17 (3) | ||

| None | 11 (9) | 40 (8) | 5 (9) | 46 (8) | ||

| Overall health | .03 | .08 | ||||

| Poor | 7 (6) | 29 (6) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | ||

| Fair | 25 (20) | 55 (12) | 12 (23) | 72 (13) | ||

| Good | 47 (38) | 178 (37) | 15 (28) | 212 (38) | ||

| Very good | 35 (28) | 139 (29) | 19 (36) | 156 (28) | ||

| Excellent | 8 (6) | 72 (15) | 3 (6) | 78 (14) | ||

| Comorbidities | .63 | .13 | ||||

| None | 29 (23) | 128 (27) | 11 (21) | 148 (27) | ||

| 1 | 37 (30) | 147 (31) | 12 (23) | 174 (31) | ||

| ≥2 | 58 (47) | 202 (42) | 30 (57) | 235 (42) |

Data shown are N (%). P values are derived from χ2 tests. Proportions may not add to 100% because of rounding and missing data.

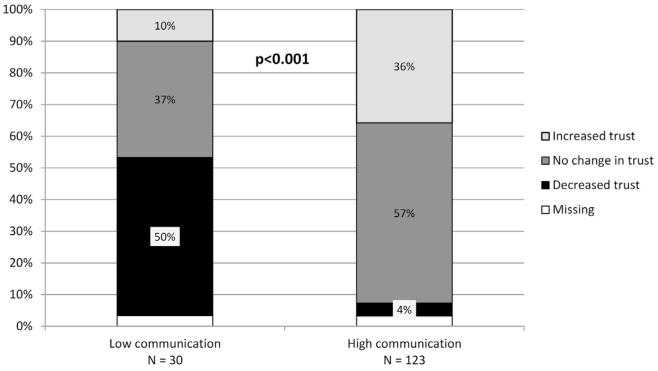

To further assess the causal relationship between complications and trust, those respondents who reported complications were asked, “Did the way that your surgeon handled the complications.” increase, decrease or have no effect on trust in the surgeon. We then evaluated the association between patient-reported level of communication and the effect that the complications had on trust in the surgeon.

Statistical analyses

We evaluated associations between complications, covariates, and the primary outcomes using χ2 tests. We used multivariable logistic regression to control for covariates in the relationships between complications and trust. Candidates for model entry were those variables with P < .2 for association with either the predictor (complications) or the outcome (trust). We then used backward selection to remove nonsignificant variables with adjusted P >.1. Finally, we used the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test to evaluate the effect of complications on trust, controlling for communication. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using the SAS 9.3 software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study sample and response rate

Of 1,158 eligible patients, 60 (5.2%) could not be located for contact, and 528 (46%) were contacted but did not complete or return the survey. Thus, 630 completed surveys were available for evaluation (54% response rate). We excluded from all analyses eight respondents (1.3%) who did not answer the question about complications (the primary predictor), leaving a final sample of 622.

Respondent characteristics and complications

Postoperative complications were reported by 155 (25%) of the respondents. Relationships between the incidence of complications and the demographics, socioeconomic factors and health status of respondents are displayed in Table I. Patients with complications were significantly more likely than those without complications to be white (79% vs 70%, P = .03), married/partnered (70% vs 60%, P = .02), or have more than one comorbid condition (54% vs 41%, P < .001). There was no clinically relevant difference in the likelihood of complications by age, sex, education, income, insurance, or overall health.

Respondent characteristics, trust and communication

There were 17 (2.7%) respondents with incomplete data for trust, 8 (1.2%) with incomplete data for communication, and 4 (0.6%) with incomplete data for both. Overall ratings of trust and communication were high. A total of 477 of 601 (79%) reported high trust in their surgeons, and 557 of 610 (91%) reported high-quality communication (Table II). The only patient characteristic greatly associated with trust was overall health—those reporting high trust were more likely to report excellent health (15% vs 6%) and less likely to report their health was fair (12% vs 20%, P = .03). Those who reported high-quality communication with their surgeon were more likely than those reporting poor communication to have annual incomes greater than $50,000 (39% vs 23%), and less likely to have incomes under $20,000 (15% vs 28%, P = .04).

Complications, trust and communication

Figure 1 shows the association between the occurrence of postoperative complications and patient-reported trust and communication with surgeons. Those who experienced complications were less likely to report high trust (73% vs 81%, P = .04) or high-quality communication (80% vs 95%, P < .001) than those without complications. Among patients without complications, mean composite scores were greater for both trust (90.1 vs 85.6, P < .001) and communication (95.6 vs 89.8, P < .001). In multivariable analyses, after accounting for the incidence of complications, we found that the only patient characteristic predictive of high trust was overall health, and the only characteristic predictive of communication quality was annual income. Adjusting for overall health did not significantly attenuate the association between complications and trust (unadjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.59, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.03–2.45; adjusted OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.07–2.59); likewise, adjusting for income did not significantly attenuate the association between complications and communication (unadjusted OR 4.60, 95% CI 2.58–8.21; adjusted OR 4.72, 95% CI 2.60–8.59).

Fig 1.

Measures of surgeon-patient relationship, by the occurrence of postoperative complications. (A) Proportion of respondents reporting high and low trust (P = .04); (B) Proportion reporting high and low communication (P < .001).

When we specifically asked respondents who experienced complications about how their surgeons’ management of complications affected trust, only 13% reported that their trust was diminished as a result; 55% reported no change; and 32% reported that the surgeons’ conduct around the complication actually increased their trust in him or her. As depicted in Fig 2, the patient-reported quality of surgeon communication appeared to mediate the likelihood that a complication would affect trust in the surgeon. Of respondents who reported a complication, 123 (80%) rated the surgeon’s communication highly. Among these patient-surgeon dyads with highly rated communication, only 4% of respondents reported a decrement in trust attributable to the complication; instead, the surgeons’ management of the complication increased trust in 36% of these pairings. In contrast, among patient-surgeon dyads whose communication was rated more poorly, 50% of respondents reported that the surgeons’ management resulted in decreased trust (P < .001).

Fig 2.

Among respondents who experienced complications, the effect of the handling of the complication on trust in the surgeon, according to the level of communication. The reported level of communication was significantly correlated with the change in trust associated with the surgeon’s handling of the postoperative complication.

Accordingly, stratifying respondents by their level of communication with the surgeon explained the entire causal relationship between complications and trust. Among respondents who reported high-quality communication, trust was high among 85% of those with complications and 85% of those without complications, whereas among those who reported low quality communication, trust was high in 22% of those with complications and 23% of those without complications (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel, P = .96).

DISCUSSION

Patients generally have very high levels of trust in their health care providers.3,5,17 Correspondingly, we found that respondents who underwent operative resection for colon cancer generally reported strongly positive relationships with their surgeons. Nearly 80% reported very high levels of trust, and more than 90% rated their surgeon very highly on measures of patient-centered communication. Even among the 25% of patients who experienced unexpected surgical complications, only 13% reported that the complication specifically reduced their trust in the surgeon.

Still, those with operative complications were significantly less likely to report high levels of trust or communication. Furthermore, the quality of communication between patient and surgeon appeared to modify the effect of complications on trust. Respondents who reported that their surgeons’ communication was highly patient-centered were substantially more likely to report high trust in the surgeon and were markedly less likely to experience a loss of trust when complications occurred. In fact, the patients’ assessment of surgeon communication explained essentially all of the effect of complications on trust. In contrast, patient characteristics, including race, education socioeconomic status, and comorbidity, had very little impact on quality of the surgeon-patient relationship and did not seem to modify or mediate the effect of complications on trust in this cohort. This difference suggests that when clinical outcomes are compromised, the relationship may be strained, and perhaps may depend on the use of high-level interpersonal skills to prevent decay. Because of the need for longitudinal therapy and surveillance, patients undergoing operation for cancer may have particularly high needs and demands for communication from their surgeons.18

These findings are consistent with research in doctor-patient relationships showing that patients’ perceptions of their physicians are determined more by physicians’ interpersonal skills5,19 and by subjective assessments of the physicians’ good will and intentions than by objective evaluation of technical skill,3,19 or health outcomes.20 Patients report significantly more satisfaction in their relationships with physicians when they feel that they are being heard and respected.8 Trust—an emotional, subjective judgment of motivations—is carefully distinguished in the literature from satisfaction—a judgment of the objective results of actions.21 Satisfaction may be mutable, depending on the most recent or salient results, whereas established trust will tend to persist even if satisfaction declines.22 This durability exemplifies the definition of trust—the optimistic acceptance of vulnerability.

Most of this literature around trust comes from medical, rather than operative, care. But there are reasons to believe that the degree, importance, and durability of trust in a surgeon may be even greater.9,10 Specialty physicians in general engender additional trust, attributed to their depth of expertise23 and the status and prestige that comes along with it.24 However, surgery brings the additional vulnerability of putting one’s life in the surgeon’s hands and ceding autonomy for treatment to proceed. This greater sense of vulnerability offers greater potential for trust and high resiliency and resistance to decay,3 which may help explain patients’ tendency for forgiveness and increased trust after the occurrence of complications.20,25 Patients who undergo surgery for CRC are intrinsically vulnerable, both because of their illness state and their dependence on providers for the choice of and access to proper treatment modalities.

Our finding that high ratings of patient-centered communication can protect against the loss of trust that can accompany surgical complications gives important insights. First, it suggests that patient-centered communication is an extremely important skill for surgeons who perform CRC resections. There is increasing recognition of the need to train surgical residents in communication skills for informed consent, delivering bad news, and counseling patients in decision-making.26,27 However, this study suggests that patient-centered communication skills may be especially important in the management of adverse events and unexpected complications.

Efforts to maintain trust and interpersonal relationships between patients and their medical providers continue to be important, as they have often been considered fundamental goods in themselves.21 Trust is an essential component of the medical relationship but also has an independent effect on health outcomes.28 Patients’ reported trust in their physicians is strongly associated with the likelihood of adherence to treatment recommendations4,6,28-32 and maintenance of continuity.33,34 In fact, trust and communication are more predictive of treatment adherence than satisfaction with outcomes.33 Trust is believed to be an important mediator in racial disparities in receipt of recommended health care,35,36 as it may underlie some of the relationship between socioeconomic pressures and nonadherence for patients with the most severe external challenges.30 Thus, efforts to maintain trust in surgeons, even in the setting of adverse events, may aid in the successful delivery of recommended care.

This study is limited primarily by its observational nature, which includes the possibility of recall bias and the inability to specify the nature or severity of complications that patients reported. We do not have detailed information about the surgeons’ identities or attributes. In addition, the survey was administered at a single point in time, whereas levels of trust in surgeons may vary with the time elapsed since surgery. However, it is important to note that trust tends to be much more stable than other patient-reported states such as satisfaction or even quality of life.3 In addition, as with any survey, we are also limited by the sample from which the data were drawn, but the effect of this limitation is mitigated by the population-based nature of the study and the broad geographical representation. It is possible that patients who underwent procedures may be predisposed to a greater level of trust compared with those who decline surgery after consultation, and those who complete the survey may be healthier and more optimistic than nonresponders. Finally, the concepts of interest—trust and communication—are hard to define and measure. They are complex and multidimensional,37 subject to respondents’ desirability bias, and patients’ vulnerability itself may engender a need for trust that results in overestimation of their actual relationships with the physician.38

We rely on patient-reported clinical outcomes for the primary predictor, surgical complications, which may limit clinical precision regarding operative complications. However, patient-reported complications are generally highly valid39 and strongly correlated with surgeon reports.40 Likewise, self-assessments of overall health are reliable predictors of health outcomes.41,42 In contrast, patients’ and surgeons’ global assessments of surgical outcomes and postoperative quality of life often diverge in important ways.40 With increasing interest in patient-reported outcomes in surgery and cancer care,43 the insight into patients’ perceptions and experiences in our survey probably outweighs any loss of clinical precision.

In summary, we find that for patients who undergo CRC surgery, postoperative complications are common and greatly affect the patients’ trust in their surgeons. Thus, operative safety and prevention of complications are important measures for maintenance of the surgeon-patient relationship. Just as importantly, however, surgeons who care for CRC should be encouraged to learn, practice, and implement effective patient-centered communication skills, because surgeons who are highly rated communicators are able to maintain high levels of trust, even in adverse clinical circumstances.

Acknowledgments

Dr Morris and the study are supported by a generous grant from the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA (Research Scholar Grant #RSG-11-097-01-CPHPS). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the American Cancer Society.

Appendix. Survey instrument for respondents’ trust and communication in surgeons

| Dimension | Question | Response options (points) |

|---|---|---|

| Trust | ||

| Fidelity | “My surgeon will do whatever it takes to get me all the care I need.” |

Strongly agree (5) Agree (4) |

| “Sometimes my surgeon cares more about what is convenient for him/her than about my needs.”* |

Neither agree nor disagree (3) Disagree (2) |

|

| Competence | “My surgeon’s medical skills are not as good as they should be.”* |

Strongly disagree (1) |

| “My surgeon is extremely thorough and careful.” | ||

| “Sometimes my surgeon does not pay full attention to what I’m trying to tell him/her.”* |

||

| Honesty | “My surgeon is totally honest in telling me about all of the different treatment options available for my condition.” |

|

| Global | “I completely trust my surgeon’s decisions about which medical treatments are best for me.” |

|

| “My surgeon only thinks about what is best for me.” | ||

| “I have no worries about putting my life in my surgeon’s hands.” |

||

| “All in all, I have complete trust in my surgeon.” | ||

| Communication | “Thinking about your conversations with your surgeon, how often did he/she listen to you carefully?” |

Always (5) Usually (4) |

| “Thinking about your conversations with your surgeon, how often did he/she explain things to you in a way you could understand?” |

Sometimes (3) Rarely (2) Never (1) |

|

| “Thinking about your conversations with your surgeon, how often did he/she show respect for what you had to say?” |

||

| “Thinking about your conversations with your surgeon, how often did he/she spend enough time with you?” |

Each item was assessed with a 5-point Likert scale. Scoring was inverted for the three items in the trust scale indicated with asterisks, with 1 point for “Strongly Agree,” 2 points for “Agree,” 3 points for “Neither,” 4 points for “Disagree,” and 5 points for “Strongly disagree.”

Footnotes

Presented at the 2013 ASCRS Annual Meeting (Poster P346), Phoenix, AZ, April 30, 2013.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morris A, Alexander G, Murphy M, Thompson P, Elston-Lafata J, Birkmeyer J. Race & Patient Perspectives on Chemotherapy for Colorectal Cancer; Academy Health 26th Annual Research Meeting; Chicago, IL. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn KL, Schneider EC, Malin JL, Adams JL, Epstein AM. Patient centered experiences in breast cancer: predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen use. Med Care. 2007;45:431–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000257193.10760.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q. 2001;79:613–39. v. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caterinicchio RP. Testing plausible path models of interpersonal trust in patient-physician treatment relationships. Soc Sci Med Part A. 1979;13:81–99. doi: 10.1016/0160-7979(79)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall MA, Zheng B, Dugan E, et al. Measuring patients’ trust in their primary care providers. Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59:293–318. doi: 10.1177/1077558702059003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trachtenberg F, Dugan E, Hall MA. How patients’ trust relates to their involvement in medical care. J Family Practice. 2005;54:344–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inui TS, Carter WB, Kukull WA, Haigh VH. Outcome-based doctor-patient interaction anaylsis: I. Comparison of techniques. Med Care. 1982;20:535–49. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198206000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galassi JP, Schanberg R, Ware WB. The Patient Reactions Assessment: a brief measure of the quality of the patient-provider medical relationship. Psychol Assess. 1992;4:346–51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Axelrod Da GS. Maintaining trust in the surgeon-patient relationship: challenges for the new millennium. Arch Surg. 2000;135:55–61. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heer F. The place of trust in our changing surgical environment. Arch Surg. 1997;132:809–14. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430320011001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Hall BL. Development of an American College of Surgeons National Surgery Quality Improvement Program: morbidity and mortality risk calculator for colorectal surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:1009–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schilling PL, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer JD. Prioritizing quality improvement in general surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:698–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.06.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gawande AA, Thomas EJ, Zinner MJ, Brennan TA. The incidence and nature of surgical adverse events in Colorado and Utah in 1992. Surgery. 1999;126:66–75. doi: 10.1067/msy.1999.98664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cancer Facts & Figures. American Cancer Society; Atlanta (GA): 2012. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Center for Health Statistics NCHS FASTATS—Inpatient surgery. 2009 Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/4procedures/2009pro4_numberprocedureage.pdf.

- 16.Dillman DA. Mail and telephone surveys: the total design method. Wiley; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaiser K, Rauscher GH, Jacobs EA, Strenski TA, Ferrans CE, Warnecke RB. The import of trust in regular providers to trust in cancer physicians among White, African American, and Hispanic Breast Cancer Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:51–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Angelica M, Hirsch K, Ross H, Passik S, Brennan MF. Surgeon-patient communication in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Arch Surg. 1998;133:962–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.9.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts CA, Aruguete MS. Task and socioemotional behaviors of physicians: a test of reciprocity and social interaction theories in analogue physician–patient encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:309–15. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Sira Z. Affective and instrumental components in the physician-patient relationship: an additional dimension of interaction theory. J Health Social Behav. 1980;21:170–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thom DH, Hall MA, Pawlson LG. Measuring patients’ trust in physicians when assessing quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:124–32. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thom DH, Campbell B. Patient-physician trust: an exploratory study. J Family Pract. 1997;44:169–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating NL, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, Bates DW, Ayanian JZ. Patient characteristics and experiences associated with trust in specialist physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1015–20. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosoff SM, Leone MC. The public prestige of medical specialties:overviews and undercurrents. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:321–6. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bosk C. University of Chicago; Chicago: 1979. Forgive and remember: managing medical failure; pp. 112–46. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandawarkar RY, Ruscher KA, Krajewski A, et al. Pretraining and posttraining assessment of residents’ performance in the fourth accreditation council for graduate medical education competency: patient communication skills. Arch Surg. 2011;146:916–21. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutul OA, Carpenter RO, Tarpley JL, Lomis KD. Missed opportunities: a descriptive assessment of teaching and attitudes regarding communication skills in a surgical residency. Curr Surg. 2006;63:401–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YY, Lin JL. How much does trust really matter? A study of the longitudinal effects of trust and decision-making preferences on diabetic patient outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:406–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs EA, Rolle I, Ferrans CE, Whitaker EE, Warnecke RB. Understanding African Americans’ views of the trustworthiness of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:642–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piette JD, Heisler M, Krein S, Kerr EA. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1749–55. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Family Practice. 1998;47:213–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penman DT, Holland JC, Bahna GF, et al. Informed consent for investigational chemotherapy: patients’ and physicians’ perceptions. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:849–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.7.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thom DH, Ribisl KM, Stewart AL, Luke DA. Further validation and reliability testing of the Trust in Physician Scale. The Stanford Trust Study Physicians. Med Care. 1999;37:510–7. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Safran DG, Montgomery JE, Chang H, Murphy J, Rogers WH. Switching doctors: predictors of voluntary disenrollment from a primary physician’s practice. J Family Practice. 2001;50:130–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):146–61. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med. 2004;38:777–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armstrong K, McMurphy S, Dean LT, et al. Differences in the patterns of health care system distrust between blacks and whites. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:827–33. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0561-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hillen MA, Onderwater AT, van Zwieten MCB, de Haes H, Smets EMA. Disentangling cancer patients’ trust in their oncologist: a qualitative study. Psycho-Oncol. 2012;21:392–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grosse Frie K, van der Meulen J, Black N. Relationship between patients’ reports of complications and symptoms, disability and quality of life after surgery. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1156–63. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bream E, Black N. What is the relationship between patients’ and clinicians’ reports of the outcomes of elective surgery? J Health Services Res Policy. 2009;14:174–82. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.008115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGee DL, Liao Y, Cao G, Cooper RS. Self-reported health status and mortality in a multiethnic US cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:41–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mossey JM, Shapiro E. Self-rated health: a predictor of mortality among the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:800–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.8.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Macefield RC, Avery KN, Blazeby JM. Integration of clinical and patient-reported outcomes in surgical oncology. Br J Surg. 2013;100:28–37. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]