Abstract

To examine the fidelity of DNA synthesis during double-strand break (DSB) repair in S. cerevisiae we studied gene conversion (GC) in which both strands of DNA are newly synthesized. The mutation rate increases up to 1400 times over spontaneous events, with a significantly different mutation signature. Especially prominent are microhomology-mediated template switches. Recombination-induced mutations are largely independent of mismatch repair, Polζ, Polη, and Pol32, but result from errors made by Polδ and Polε. These observations suggest that increased DSB frequencies in oncogene-activated mammalian cells may also increase the probability of acquiring mutations required for transition to a cancerous state.

A significant increase in mutation rates has been proposed to explain how a single cell can sustain multiple mutations within a finite lifespan resulting in malignancy (1). The origin of this mutator phenotype remains unknown, though an interesting correlation exists between increased DNA damage levels observed in oncogene activated precancerous cells (2) and the timing of this necessary mutation rate increase. Most oncogene-induced DNA damage appears to be DSBs, which pose a severe challenge to maintaining genome integrity. Various homologous recombination (HR) mechanisms (3) repair DSBs, among which GCs pose the least genomic threat. GCs have been associated with increased mutation rates (4–6), largely dependent on the error-prone translesion polymerase, Polζ; however, these errors were measured in presumably single stranded DNA adjacent to a DSB.

To directly examine GC-associated mutation rates occurring in repaired DNA consisting of two newly synthesized strands, we took advantage of budding yeast mating-type (MAT) switching initiated by an HO endonuclease-induced DSB and repaired by synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) (Fig. 1A) (7). We modified the heterochromatic donor HMRa, replacing the HMRa1 open reading frame (ORF) with K. lactis URA3 (Kl-URA3) (Fig. S1). DSB repair efficiency was ~99% and nearly all repair events yielded Ura+ (i.e. mata1::Kl-URA3) cells. However, Ura− mutants were selected using 5-fluoroorotic acid. Cells acquiring Ura− mutations during recombination become Ura+ if hmr::Kl-URA3 remains unaltered and is desilenced (8). Among exponentially growing cells, recombination-induced Ura− mutagenesis was 240 times higher than the spontaneous rate of mata1::Kl-URA3 (Table 1) and was specific to the repaired MAT locus. The GC-associated mutation rate in cells synchronously released from G1 was 5.9-fold higher than asynchronous cultures (p = 0.0001) and 1400 times higher than spontaneous events (Table 1).

Figure 1.

(A) MATα switching occurs via SDSA (4). DNA synthesis beginning in HMR-Z copies Y sequences and progresses into HMR-X. The nascent strand dissociates and anneals to MAT-X sequences on the other side of the DSB. Nonhomologous sequences are clipped off and second strand synthesis initiates using the first strand as a template. Nonprocessive DNA synthesis results in premature dissociation from HMR, which can result in error-prone reannealing to the HMR donor template or to other ectopic templates. To complete the GC, template switch events must dissociate again and reanneal to HMR. (B) GC-associated quasi-palindrome template switch at position 584-585 within the Kl-URA3 ORF. (C) GC-associated ectopic template switch into Sc-ura3-52 and then back to hmr::Kl-URA3 in which a frameshift is introduced due to misalignment at a shared 5-bp sequence. Underlined sequences indicate Kl-URA3 microhomology (nts 423-427).

Table 1. Spontaneous and GC dependent mutation rates.

Fold changes from the corresponding WT rate are in parentheses.

| Genotype | Spontaneous Mutation Rate (×10−8) |

MAT-Switching Mutation Rate (×10−5) |

Fold Change in Rate From Spontaneous |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 5.8 ± 2.3(1) | 1.4 ± 0.5 (1) | 240 |

| WT G1/S | N/A | 8.1 ± 1.0(5.9)*** | 1400 |

| mlh1Δ | 239 ± 46 (41)*** | 5.6 ± 1.4 (4)** | 23 |

| msh6Δ | 229 ± 42 (39)*** | 2.3 ± 0.35 (1.6) | 10 |

| rev3Δ | 8.1 ± 2.4(1.4) | 1.6 ± 0.31(1.1) | 200 |

| rev3Δ/rad30Δ | 10.1 ± 2.3(1.7) | 3.2 ± 0.66 (2.3)** | 310 |

| pol32Δ | 20 ± 7.5 (3)* | 0.66 ± 0.5 (0.5) | 33 |

| pol30(K127,164R) | 4.6 ± 0.02(1) | 2.9 ± 0.3 (2.1) | 630 |

| pol2-4 | 43 ± 11 (7)** | 6.0 ± 0.78 (4.3)** | 140 |

| pol3-01 | 440 ± 35 (76)** | 3.1 ± 1.0(2.2) | 7 |

| dun1Δ | 15 ± 6 (3) | 2.0 ± 0.6 (1.5) | 130 |

indicates p < 0.05 (t-test) vs. the corresponding WT rate,

indicates p < 0.01,

indicates p < 0.001.

± indicates Standard Error of the Mean. N/A = not applicable.

Sequences of independent Ura− GC events (Fig. 2 and Table 2) reveal both synchronous and asynchronous WT cells produce mainly single base-pair substitutions (BPSs) with a significant fraction being −1 frameshifts; these data were combined for subsequent statistical comparisons. The proportions of BPSs, −1 deletions, +1 insertions, and complex mutations differ significantly (p = 0.015) from our analysis of spontaneous K.l.-URA3 mutations as well as from a recent study on spontaneous mutations of S. cerevisiae URA3 (Sc-URA3) (9) (Table 2). Nearly all GC-associated −1 frameshifts occur in homonucleotide runs (≥2 bases) compared to about half among spontaneous events (p = 0.04) (9).

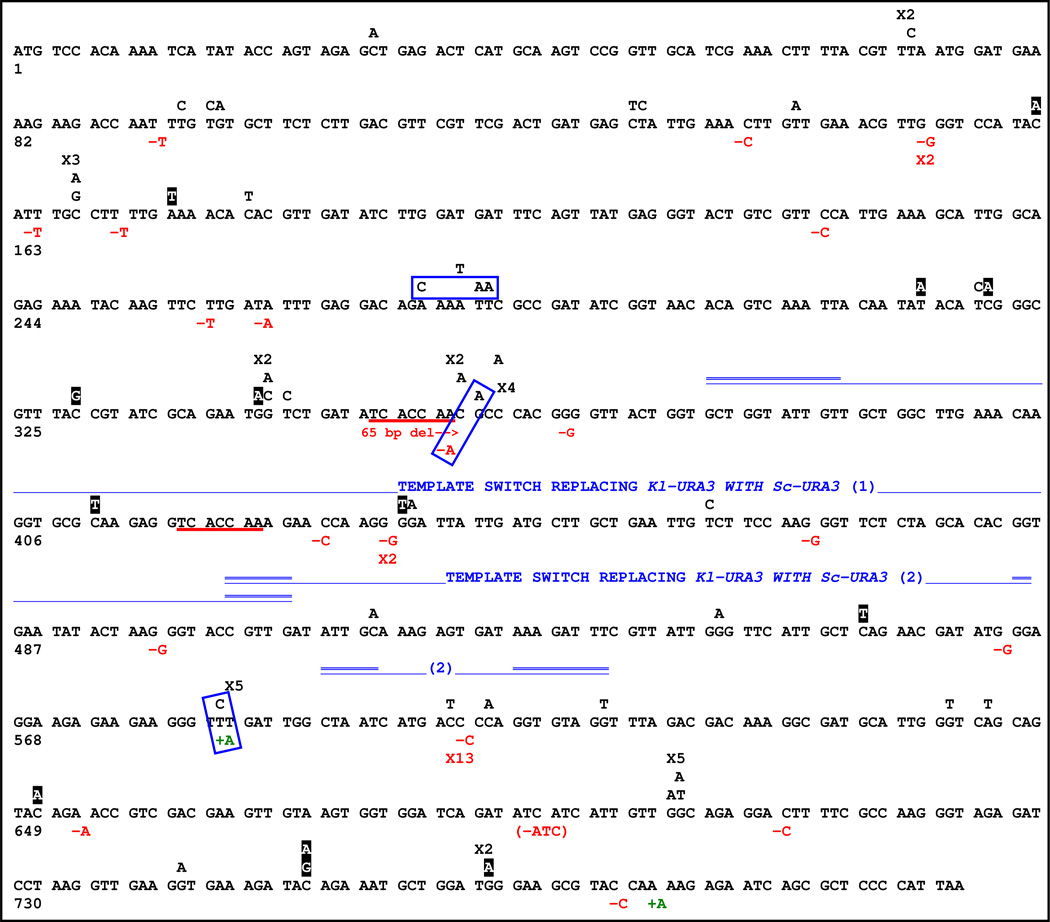

Figure 2.

GC-associated Kl-URA3 mutant spectrum. Single letters above the Kl-URA3 ORF indicate BPSs. Black boxes with white text indicate nonsense mutations. Insertions and deletions are shown below the ORF; insertions are green and deletions are red. A large deletion occurring between direct repeats is indicated with repeats underlined in red. Blue lines below the ORF mark two ectopic events where Kl-URA3 sequences were replaced by Sc-ura3-52 sequences; double blue lines depict microhomology junctions. The template switch marked as (2) contained two independent jumps to Sc-ura3-52, one of which contained a frameshift. Quasi-palindrome mediated template switch mutations are within blue boxes (Figs. 1C & S3 depict these mechanisms). Recurrent mutations are indicated by an “X” followed by the number of times that mutation was observed.

Table 2. Spontaneous and gene conversion dependent spectra for K. lactis URA3.

For 1 bp deletions, 1 bp insertions, BPSs and complex mutations, numbers in parentheses indicate percentage of total mutations represented by each respective mutation.

| Type of mutation | WT spont. |

S.C.-URA3 spont. (9) |

WT GC comb. |

pol2-4 GC |

pol2-4 spont. |

pol3-01 GC |

pol3-01 spont. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bp substitutions |

46 (75%) | 167(81%) | 56 (54%) | 21 (46%) | 41 (82%) | 48 (98%) | 49 (98%) |

| transitions |

19 | 46 | 32 | 10 | 8 | 20 | 17 |

| tranversions |

27 | 121 | 24 | 11 | 33 | 28 | 32 |

| −1 deletions |

5 (8.0%) | 22(11%) | 32(31%) | 12(26%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.0%) |

| −1 in homo nt |

3 | 14 | 29 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| −1 in mono nt |

2 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| +1 insertions |

1 (2.0%) | 3 (1.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 7(15%) | 9(18%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0 |

| +1 in homo nt |

1 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| +1 in mono nt |

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| template switches |

0 | n/a | 12(12%) | 5(11%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ectopic (S.c.ura3-52) |

0 | n/a | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| quasi-palindrome |

0 | n/a | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| other complex |

9(15%) | 15(7.0%) | 2 (2.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total mutations | 61 | 207 | 104 | 46 | 50 | 49 | 50 |

−1 deletions and +1 insertions are divided into events occurring in either homonucleotide runs ≥2 nt or non-repeating sequences.

10 out of 12 GC-associated complex mutations can be explained by template switches occurring in the context of quasi-palindromes (Fig. 1A, 1B, & 2); similar mutations have been observed from E. coli to human p53 tumors (10–12). Two other complex GC events resulted from interchromosomal template switches between the hmr::Kl-URA3 donor, on chromosome 3, and the endogenous Sc-ura3-52 allele, on chromosome 5, which share only 73% identity. In these events the nascent DNA strand must prematurely dissociate from its donor template, hmr::Kl-URA3, invade a new donor, Sc-ura3-52, and eventually come back to hmr::Kl-URA3 to complete MAT switching (Fig. 1A). Homology at the junctions within these Kl-Sc-Kl-ura3 chimeras ranges from 2–11 bp. Of 455 GC-dependent Ura− mutants sequenced in WT and several mutant backgrounds, 10 such interchromosomal template switches and 27 presumptive quasi-palindrome events were identified (Table 2 & Table S1). No such events were detected in spontaneous mat::Kl-URA3 mutations (Table 2). All 10 ectopic template switches used a shared 5-bp microhomology which misaligns during strand invasion and introduces a frameshift, −1 if used as the entry point or +1 if used as the exit point (Fig 1C); all DNA synthesis subsequent to the template switch was error free. Without this misalignment these events would apparently result in Ura+ chimeric Kl-Sc-Kl-ura3 GC products and avoid detection. To generate Ura− outcomes not requiring the 5-bp misaligning sequence, we inserted two 4-bp sequences into Sc-URA3 such that in-frame template switches would generate Ura− outcomes (Fig. S4A). This modification increased interchromosomal template switch rates approximately 3-fold. Junctions contained 2–17 bp microhomologies, and only one of six used the 5-bp misaligning sequence (Fig. S4B). We conclude that GC is significantly less processive than normal DNA replication, even though GC requires the PCNA clamp that should anchor DNA polymerases to the template (13).

These ectopic template switches are reminiscent of spontaneous segmental duplications in yeast and copy number variation in human cancers, which are proposed to occur via microhomology-mediated break-induced replication (BIR) (14, 15) and in yeast require the nonessential Polδ subunit, Pol32 (16). GC-associated mutations rates and mutant spectra do not change in the absence of Pol32 (Table 1, Table S1 & Fig. S2F). Moreover, ectopic template jumps proved to be Pol32-independent (Fig. S2C); thus we suggest they arise by a novel microhomology-mediated SDSA pathway.

Mismatch repair (MMR) effectively repairs mismatches in heteroduplex DNA formed during MAT switching strand invasion (17). However, MMR plays a minor role in discouraging mutations arising during repair DNA synthesis (Table 1). Moreover, mutant spectra of mlh1Δ and msh6Δ strains were not different from WT (Fig. S2B, S2C & Table S1). Thus, either the extending DNA strand does not recruit MMR proteins during GC or MMR cannot distinguish old from new strands and hence mutations are as likely to be introduced as removed.

Error-prone Rev3 (DNA Polζ) appears to play a central role in generating BPSs but not frameshift mutations in presumably single-stranded DNA adjacent to a repaired DSB (4–6). We investigated the role for REV3 where both DNA strands are newly synthesized. REV3 does not significantly affect recombination efficiency, nor the GC mutation rate or spectrum (Table 1, Table S1 & Fig S1D). We suggest Rev3 plays a nonessential role filling-in single-strand gaps adjacent to the repaired locus, but not within the gap-repair region. We also created a rev3Δ rad30Δ double mutant, lacking both Polζ and the error-prone polymerase Polη (18). MAT-switching efficiency and mutant spectra were not affected, but there was a modest, statistically significant increase in the GC mutation rate (Table 1 & Fig. S1E), suggesting Polη plays an error-free role during GC. Further evidence that TLS polymerases do not greatly affect GCs is illustrated by the observation that GC mutation rates are not changed by pol30-K127,164R, an allele insensitive to Ubiquitylation or SUMOylation, modifications that recruit TLS polymerases (Table 1).

Both Polδ and Polε DNA polymerases are important for HR (13, 16, 19–23). To test for preferential usage during GC we examined proofreading deficient, error-prone alleles, pol3-01 and pol2-4, respectively. The GC mutation rate for pol2-4 is 4.3-fold higher than WT (p = 0.004), indicating Polε plays an important replicative role during GC (Table 1). The spontaneous and GC mutation spectra for pol2-4 were significantly different from WT with a large increase in +1 frameshifts (Table 2 & Fig S1G, S1H).

The GC-dependent mutation rate for pol3-01 was only 2.2-fold above WT (p > 0.05) suggesting that Polδ plays a less substantial role during GC than previously suggested (22); however, the Ura− mutation spectrum revealed that Polδ plays a major role. Most striking, pol3-01 eliminated all −1 frameshifts and complex events (p < 0.0001) (Table 2 & Fig. S1I), which also occurred among spontaneous mutations (p < 0.05) (Table 2 & Fig S1J). The lack of −1 frameshifts and other template switches may be explained from the fact that a Polδ proofreading-defective protein is actually more processive than WT (24). Much of the increased spontaneous mutation rate in pol3-01 appears to be a consequence of activating a Dun1 kinase-dependent S-phase or DNA damage checkpoint (25). It is possible that the GC-associated effects with pol3-01 could be the result of activating a Dun1-dependent checkpoint; however we find that deleting Dun1 alone has no effect on the rate of spontaneous or GC mutation rates or mutant spectra (Table 1, Table S1 & Fig S2K).

We conclude that Polε and Polδ are both involved in DNA synthesis during GCs with no apparent preference for using one polymerase over the other. Whether first and second-strand syntheses are carried out by different DNA polymerases we cannot ascertain. The presence of frequent template switches suggests that DNA synthesis during GC has decreased processivity compared to S-phase replication. During a non-processive GC where there is premature dissociation of the nascent DNA strand from the template, followed by reinitiation, there may be an opportunity to switch between polymerases.

Although GCs are generally thought to be the most error-free pathway of DSB repair, it exhibits a significantly elevated mutation rate. Weinberg (26) argues that mammalian cells must suffer ≥6 mutations before transitioning to a fully cancerous state. How cells experience such high mutation levels during limited life spans remains unknown, except when MMR genes or proofreading activity of replicative polymerases are mutated (27–29). The observation that activated oncogenes promote dramatic increases in DSB formation (2) suggests that some mutations required for carcinogenesis may arise by increased recombination-associated mutation rates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Kl-URA3 (GenBank: Y00454) was a gift from Oliver Zill and Jasper Rine. pol30-K127,164R was a gift from Helle Ulrich. NIH Genetics Training Grant GM007122 supported W.M.H. NIH Grant GM20056 to J.E.H. supported the research.

References and Notes

- 1.Loeb LA, Bielas JH, Beckman RA. Cancer Res. 2008 May 15;68:3551. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halazonetis TD, Gorgoulis VG, Bartek J. Science. 2008 Mar 7;319:1352. doi: 10.1126/science.1140735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paques F, Haber JE. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999 Jun;63:349. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holbeck SL, Strathern JN. Genetics. 1997 Nov;147:1017. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.3.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rattray AJ, Shafer BK, McGill CB, Strathern JN. Genetics. 2002 Nov;162:1063. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.3.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Y, Sterling J, Storici F, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA. PLoS Genet. 2008 Nov;4:e1000264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haber JE. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bitterman KJ, Anderson RM, Cohen HY, Latorre-Esteves M, Sinclair DA. J Biol Chem. 2002 Nov 22;277:45099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang GI, Murray AW. Genetics. 2008 Jan;178:67. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.071506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenblatt MS, Grollman AP, Harris CC. Cancer Res. 1996 May 1;56:2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ripley LS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Jul;79:4128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.13.4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strathern JN, Shafer BK, McGill CB. Genetics. 1995 Jul;140:965. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.3.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2004 Aug;24:6891. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.6891-6899.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payen C, Koszul R, Dujon B, Fischer G. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hastings PJ, Lupski JR, Rosenberg SM, Ira G. Nat Rev Genet. 2009 Aug;10:551. doi: 10.1038/nrg2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lydeard JR, Jain S, Yamaguchi M, Haber JE. Nature. 2007 Aug 16;448:820. doi: 10.1038/nature06047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haber JE, Ray BL, Kolb JM, White CI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Apr 15;90:3363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunkel TA, Pavlov YI, Bebenek K. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003 Feb 3;2:135. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budd ME, Campbell JL. Mol Cell Biol. 1995 Apr;15:2173. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halas A, Ciesielski A, Zuk J. Acta Biochim Pol. 1999;46:862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards S, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2003 Apr;23:2733. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2733-2748.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maloisel L, Fabre F, Gangloff S. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 Feb;28:1373. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01651-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith CE, Lam AF, Symington LS. Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Mar;29:1432. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01469-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stith CM, Sterling J, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA, Burgers PM. J Biol Chem. 2008 Dec 5;283:34129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806668200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Datta A, et al. Mol Cell. 2000 Sep;6:593. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinberg RA. Sci Am. 1996 Sep;275:62. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0996-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leach FS, et al. Cell. 1993 Dec 17;75:1215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90330-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papadopoulos N, et al. Science. 1994 Mar 18;263:1625. doi: 10.1126/science.8128251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albertson TM, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Oct 6;106:17101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907147106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.