Abstract

Objective

Disturbances in the basal ganglia portions of Cortico-Striato-Thalamo-Cortical (CSTC) circuits likely contribute to the symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). This study examines the morphologic features of the basal ganglia nuclei (caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus) in children with ADHD.

Design

We examined 104 individuals (47 with combined-type ADHD and 57 controls) aged 7 to 18 years, in a cross-sectional case-control study using anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. We measured conventional volumes and the surface morphology for the basal ganglia.

Results

Overall volumes were significantly smaller only in the putamen. Analysis of the morphological surfaces revealed significant inward deformations in each of the three nuclei that were localized primarily in portions of these nuclei that are components of limbic, associative, and sensorimotor pathways in the CSTC circuits in which these nuclei reside. The more prominent these inward deformations were in the patient group, the more severe were their ADHD symptoms. Surface analyses also demonstrated significant outward deformations of all basal ganglia nuclei in the ADHD children treated with stimulants compared to those with ADHD who were untreated. These stimulant-associated enlargements were in locations similar to the reduced volumes detected in the ADHD group relative to controls. The outward deformations associated with stimulant medications attenuated the statistical effects of the primary group comparisons.

Conclusion

These findings potentially represent evidence of anatomical dysregulation in the circuitry of the basal ganglia of children with ADHD and suggest that stimulants may “normalize” morphological features of the basal ganglia in children with ADHD.

INTRODUCTION

The pathogenesis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is thought to involve anatomical and functional disturbances in Cortico-Striato-Thalamo-Cortical (CSTC) circuits. These circuits traverse portions of the frontal cortex and basal ganglia that support the learning of emotional responses to reinforcing stimuli, the regulation of attentional resources, and the programming of simple and complex motor behaviors. This pathophysiological model for ADHD is based as much on what is known of the neural bases of these processes from animal models(1) and neurobiological studies of healthy humans as it is on direct experimental evidence from youth who have ADHD (2). Indeed, findings from brain imaging studies of children with ADHD have been highly variable, with the preponderance of the largest and methodologically most rigorous studies indicating the presence of reduced volumes of the cerebral cortex(3), particularly of the lateral prefrontal cortex(4, 5) and reduced volumes of one or more basal ganglia nuclei(6–8) (caudate, putamen, or globus pallidus). With one exception (9), those studies have not examined the local volumes of basal ganglia nuclei to determine which portions of those nuclei, and by implication which portions of the CSTC pathways, are involved in the pathogenesis of ADHD. None of the studies have yet reported the presence of significant effects of stimulant medications on basal ganglia morphology, despite the fact that stimulant medications are among the most robustly and most predictably helpful medications available for any neuropsychiatric illness.

Herein we present a magnetic resonance imaging study of the three basal ganglia nuclei – caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus- in 104 children with ADHD and control subjects. We examine the conventional volumes of the basal ganglia and their detailed surface morphologic features. We hypothesize that these measures will differ between youth with ADHD and controls and that the morphological features of basal ganglia nuclei in ADHD youth treated with stimulants will differ from patients not taking stimulants.

METHODS

Further details of the recruitment, behavioral assessments, MRI pulse sequence, and image processing are described in the Supplemental Material.

Participants

We acquired magnetic resonance images in 47 children with ADHD and 57 healthy controls, aged 7–18 years (Table 1). All patients met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)(10) criteria for combined-type ADHD. Exclusion criteria for patients with ADHD included a history of obsessive-compulsive, bipolar, psychotic, anxiety, tic, conduct, or pervasive developmental disorders. In the ADHD group, a total of 23 (48.9%) patients had a co-occurring lifetime-diagnosis of depression (n=12), oppositional defiant disorder (n=12), or specific developmental disorder (e.g., reading, mathematics, written expression, or motor coordination; n=7).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics.

At the time of scanning, 31 (66.0%) patients in the ADHD group were taking stimulants. In the ADHD group, patients on and off stimulants were similar in age (12.9±3.3 vs. 12.4±2.9; p=0.47) and sex (69% male vs. 87% male, χ2=2.29; p=0.13). Symptom severity was significantly higher in the ADHD group off stimulants compared to those on stimulants (31.9±10.3 vs. 24.6±11.4; p=0.04. For those patients taking stimulants, 5 were concomitantly treated with α-agonists (n=2), or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (n=3). Of the unmedicated patients, one received medicine for 30 months in the past and was off medications for 19 months at the time of the scan; the remainder were all drug–naïve. Patients on stimulants had a 43.3 ± 29.1 month mean (±SD) duration of stimulant use at the time of scan (range: 3 to 108 months). No controls were on psychotropic medications. In the ADHD group, a total of 23 (48.9%) patients had a co-occurring lifetime-diagnosis of depression (n=12), oppositional defiant disorder (n=12), and specific developmental disorder (e.g., reading, mathematics, written expression, or motor coordination; n=7). Total symptom severity scores on the DePaul-Barkley ADHD rating scale(11) were obtained on the day of the scan. They therefore reflect, in part, the treatment effects of stimulants for those youth who were taking medication.

| Patients with ADHD (n=47) | Controls (n=57) | Test Statistics | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Boys | 38 | 38 | χ2=2.63, df=1 | 0.11 |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 12.5 ± 3.0 | 11.7 ± 3.1 | t=1.31, df=102 | 0.19 |

| SES, mean ± SD | 45.2 ± 13.4 | 48.4 ± 10.7 | t=1.37, df=102 | 0.18 |

| Full-Scale IQ, mean ± SD | 109.7 ± 18.3 | 115.6 ± 17.2 | t=1.67, df=102 | 0.1 |

| Number Right-Handed | 45 | 53 | χ2=0.36, df=1 | 0.55 |

| Total ADHD symptom severity | 27.1 ± 11.3 | 5.8 ± 6.2 | t=11.56, df=94 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; IQ, intelligence quotient; SD, standard deviation; SES, socioeconomic status

We estimated symptom severity using the DePaul Barkley ADHD rating scale(11). We excluded control participants who had a history of medical, psychiatric, or neurologic disorders. Additional exclusion criteria for both groups included any previous seizure, head trauma with loss of consciousness, current or previous substance abuse, or IQ below 70. The Institutional Review Boards of Yale and Columbia Universities approved the study. Parents provided written informed consent, and participants provided verbal assent.

Surface Morphology

We evaluated the surface morphology of the basal ganglia by computing the signed Euclidean distance from each point on the surface of the basal ganglia nuclei of an individual participant to the corresponding point on the basal ganglia nuclei of a healthy control reference template. We encoded outward deformations using positive distances and inward deformations using negative distances.

We previously validated these procedures to identify known regional increases and decreases in volumes at the surface of brain structures(12). Procedures are detailed elsewhere(13–15) and summarized here. We applied a two-step procedure for surface morphometry of the basal ganglia. First, we coregistered each participant’s brain with the template brain using a similarity transformation. The parameters estimated for this transformation are: global scaling, three translations, and three rotations of the brain. The translation and rotation parameters were applied to place the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus into the template space. The global scaling parameters controlled for any scaling differences in these structures caused by differing whole-brain volumes. Second, we independently and rigidly coregistered each basal ganglia nucleus and then nonlinearly warped it to the exact size and shape of the corresponding nucleus in the template, allowing precise identification of corresponding points along the surface of these regions. Next, we unwarped each region while preserving the labels assigned to corresponding points on the surface of each region. We then computed the distance from each point on the surfaces of the basal ganglia nuclei for each participant to its corresponding point on the template. Therefore, at each point on the surface of a basal ganglia nucleus in the template brain, we had a set of 57 distances for the healthy control group and a set of 47 distances for the ADHD group. Finally these two sets of distances were compared statistically to determine local regions of significant differences between the groups of participants (below).

Template Selection

Conceivably, localization and interpretation of point correspondences may depend on the selected template(14). Therefore, we selected the template brain by a two-step process. First, we selected as a preliminary template the brain of the healthy participant that best represented, demographically, the healthy participants in the study. The remaining healthy participants were coregistered to this preliminary template. We then computed the distances between the corresponding points on the surface of the basal ganglia nuclei, as detailed above. Second, we determined the final template by selecting the brain for which all points across the surface of the basal ganglia nuclei were closest to the average of the computed distances. The surface morphometry is then repeated for our entire cohort of healthy and affected participants using the final template brain.

We used a single representative brain as a template rather than an averaged brain because a single brain has well-defined tissue interfaces, such as the CSF-gray matter or gray-white matter interfaces. Averaging images for a template blurs these boundaries and increases registration errors that are subtle but important when distinguishing subtle effects across populations. In addition, precise surface morphometry requires a brain with smooth gray and white surfaces that are devoid of topological defects, which cannot be reconstructed by averaging brains from several participants.

Statistical Analysis

For conventional volumes, to test the a priori hypothesis that patients with ADHD have different volumes of basal ganglia nuclei compared to healthy controls, we calculated the statistical significance of the main effects of diagnosis (between-factor) and the interaction of diagnosis with nucleus (within-factor) in a mixed-model analysis of covariance (PROC MIXED; SAS Institute Inc) with repeated measures over a spatial domain (the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus). Covariates included in the mixed-model for assessment of conventional volumes included whole-brain volume (to control for scaling effects), age, sex, and hemisphere (left or right). To control for possible confounds, lifetime diagnoses of comorbid depression, oppositional-defiant disorder, or specific-developmental disorders (e.g., reading, mathematics, written expression, or motor coordination problems) were used in confirmatory models to assess the effects of these comorbid conditions. Statistically nonsignificant terms (P ≥ 0.10) were eliminated from the final mixed-model. The variables age and sex remained in all final statistical models because of the biological plausibility that these variables could influence overall findings. All dependent measures were normally distributed, as assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

For analysis surface features, the distances between each point on the surface of the basal ganglia for each participant and the corresponding point on the template basal ganglia were compared statistically between groups using multiple linear regression while covarying for age and sex. Because global scaling parameters controlled for any scaling differences across brains, covarying for whole-brain volume was not necessary. We used the theory of Gaussian Random Fields (GRFs) to correct p-values appropriately for the multiple comparisons performed across the basal ganglia surface(16).

We used two complementary approaches to test the hypothesis that the morphological features of basal ganglia nuclei in youth with ADHD who are currently treated with stimulant medication differ from the basal ganglia of patients not taking stimulant medications. First, we analyzed the effects of stimulant use in the ADHD group alone. For conventional volumes, we tested the main effect of stimulant use (between-subject factor) and the interaction of stimulant use with nuclei (within-subject factor) in a mixed effects model (while covarying for age, sex, and whole-brain volume). For surface morphology, we tested the significance of stimulant use in a multiple linear regression model while covarying for age and sex. Second, we assessed the main effects of diagnosis (as detailed above) on surface features in the subgroup of ADHD youth who were taking stimulants (n=31) compared with healthy controls, and in the subgroup of ADHD youth off stimulants (n=16) compared with healthy controls.

Symptom Severity

In the ADHD group, we explored correlations of basal ganglia nuclei volumes or surface features with symptom severity at the time of scanning as measured with the DePaul-Barkley ADHD rating scale(11).

RESULTS

Effects of Diagnosis

The main effect of diagnosis on the conventional volumes of the basal ganglia nuclei was significant (F95=8.30; p=0.005; Table 2). The significant diagnosis-by-nucleus interaction demonstrated nucleus specificity in diagnosis effects (diagnosis-by-nucleus interaction, F204=10.53; p<0.0001). Least square means between the diagnostic groups indicated that the contribution to group differences derived mainly from smaller putamen volumes (±SD) in the youth with ADHD than in the controls (4966.7±74 vs 5311.8±67 mm3; p<0.001). Overall volumes of the caudate (3683.9±79 vs 3808.3±71 mm3; p=0.11) and globus pallidus (1698.1±26 vs 1785.0±23 mm3; p=0.37) did not differ significantly across diagnostic groups.

Table 2. Effects of ADHD on Conventional Volumes.

Group differences in conventional volumes of the BG were tested using a mixed-model analysis of covariance. The statistically significant effects of diagnosis (ADHD) and the interaction of diagnosis with nucleus (ADHD x Nucleus) indicated the presence of differences in volumes across diagnostic groups that vary by BG nuclei (caudate, putamen, or globus pallidus). Additional significant terms in the final model included nuclei, indicating that the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus differed significantly from one another in their volumes and WBV indicating the presence of scaling effects (the larger the brain, the larger the BG nuclei). The mean ± SD WBV did not differ appreciably across groups (patients with ADHD; 1343.5 ± 136 cm3; controls; 1354.8 ± 127 cm3; t102 = 0.44; P = 0.66). The variables age and sex remained in the final model because of the biological plausibility that these variables could conceivably influence the overall findings. The potential confounds of depression (F96 = 0.02; P=0.89), oppositional defiant disorder (F96 = 0.87; P=0.35), specific developmental disorder (F96= 0.07; P=0.80), and hemisphere (F515 = 0.06; P=0.81), were not statistically significant and therefore were not included in the final model.

| Variable | df | F Score | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effect | |||

| Diagnosis | 99 | 8.30 | 0.005 |

| Diagnosis x Nucleus | 204 | 10.53 | <0.0001 |

| Covariates | |||

| Sex | 99 | 0.15 | 0.70 |

| Age | 99 | 3.09 | 0.08 |

| Nucleus | 204 | 4861 | <0.0001 |

| WBV | 99 | 49.19 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; df, degrees of freedom; WBV, whole-brain volume.

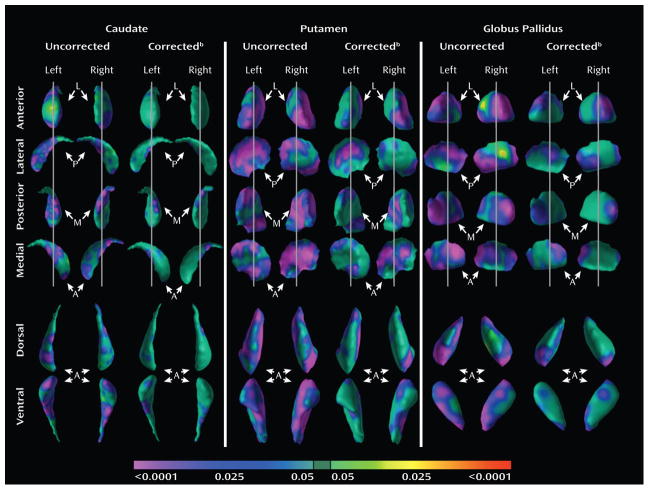

Surface analyses demonstrated that the decrease in overall conventional volumes of the putamen in the ADHD group derived from marked inward deformations across multiple portions of its surface (Fig. 1). In addition, inward deformations of several portions of the surface of the caudate and globus pallidus survived GRF correction, indicating the presence of regional volume reductions in the ADHD group that were not evident using measures of overall conventional volume (Fig. 1). These inward deformations corresponded approximately to the ventral, anterior, and posterior aspects of these nuclei.

Figure 1. Main Effects of Diagnosis on Surface Morphologic Features.

The right and left caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus are displayed in rotational views and in their dorsal and ventral perspectives. Anterior (A), posterior (P), lateral (L) and medial (M) views of each nucleus are shown. The curved arrow at the top of each column indicates the direction of rotation. The color bar at the bottom indicates the significance value for group comparisons at each point on the surface. Green values represent statistically non-significant differences (P ≥ 0.05) of the surface of the basal ganglia nuclei between groups. Yellow and red values (P<0.0001) represent outward deformations of the surfaces, or local volume increases, whereas blue and purple represent inward deformations of the surfaces, or local volume reductions (P<0.0001). Gaussian Random Field (GRF)-corrected maps are shown for each nucleus.

Effects of Stimulant Use

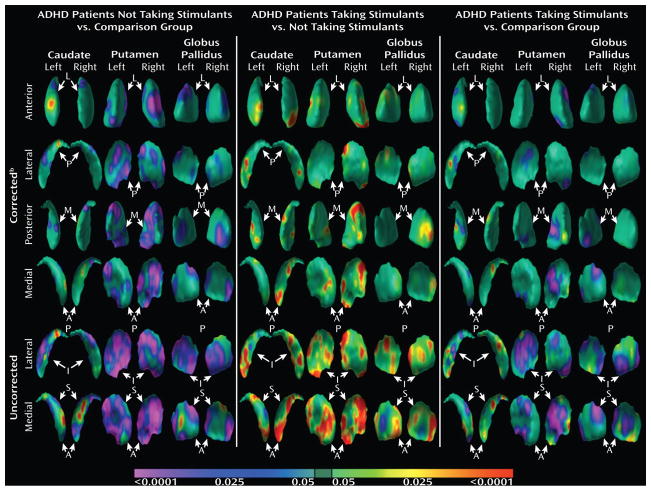

Within the ADHD group, analysis of conventional volumes in those treated with stimulant medication and those untreated did not discern significant effects of stimulant medication (main effects of stimulant use F41= 0.20; p=.67; stimulant use-by-nucleus interaction F90= 2.21; p=0.12). Volumes of the caudate (3681.0 ± 92 vs 3642.6 ± 129 mm3; p=0.63), putamen (4989.1 ± 101 vs 4838.1 ± 142 mm3; p=0.21), and globus pallidus (1728.3 ± 32 vs 1671 ± 45 mm3; p=0.51) did not differ significantly between those in the ADHD group on stimulants compared to those off stimulants. Surface analyses, however, revealed significant, localized outward deformations of the basal ganglia surface in the youth with ADHD treated with stimulants compared to those with untreated ADHD (Fig. 2). In addition, we detected a statistical attenuation of the main effect of diagnosis when comparing the control group to individuals in the ADHD group treated with stimulants (Fig. 2), whereas we detected a strengthening of the statistical significance of diagnosis when comparing to the control group those in the ADHD group who were untreated with stimulants (Fig. 2). These findings demonstrate the presence of exacerbated inward deformations of the basal ganglia surface in untreated compared with treated youth with ADHD. Our findings did not change when excluding the 5 youth with ADHD who were taking both stimulant and non-stimulant medications (not shown), or when excluding from the off-stimulant group the one youth who was not stimulant-naïve (not shown).

Figure 2. Main effects of Stimulants on Surface Morphologic Features.

For ease of comparison, GRF-corrected images are displayed in anterior, posterior, lateral, and medial views, whereas the GRF-uncorrected images are displayed in lateral and medial views only. The color bar at the bottom indicates the color coding for P values associated with either the diagnosis term (column A and C) or the stimulant term (column B). A. Main effect of diagnosis in youth with ADHD off stimulants compared to controls. B. Main effect of stimulant use in youth with ADHD taking stimulants compared to those with ADHD not taking stimulants. The outward deformations in the basal ganglia of youth treated with stimulants compared to those untreated approximately align with the inward deformations detected in the overall main effects of diagnosis (Fig. 1). C. Main effect of diagnosis in youth with ADHD on stimulants compared to controls. The statistical attenuation of the main effects of diagnosis, indicated by a less significant inward deformations on the surface of the basal ganglia in the youth on stimulants (C) versus those off stimulants (A) compared to controls, suggests that a major component of the overall main effects of diagnosis (Fig. 1) was attenuated by the effects of stimulant medications on the morphological features of the basal ganglia. Abbreviations are as described in Figure 1.

Correlations with Symptom Severity

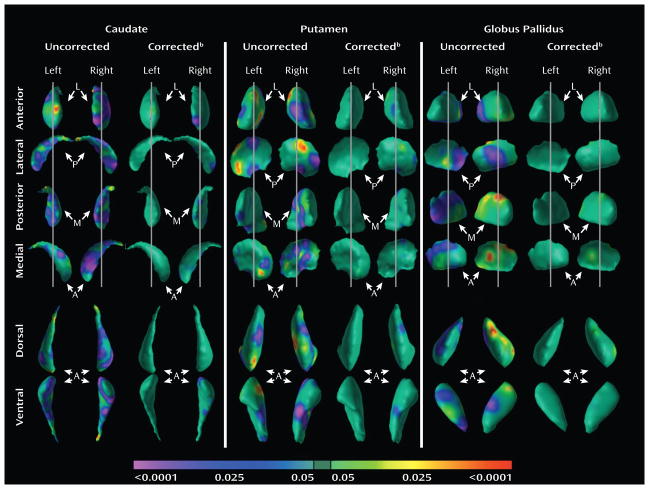

Conventional volumes did not correlate significantly with measures of symptom severity in the ADHD group for the caudate (r=−.04, p=0.83), putamen (r=.08, p=0.83), or globus pallidus (r=.05, p=0.76). Nevertheless, surface analyses revealed that ADHD symptom severity positively correlated with the magnitude of inward deformations (greater symptoms severity correlated with larger inward deformations of the surface of the basal ganglia; Fig. 3) within several portions of the basal ganglia surfaces where those deformations were detected in the ADHD group (Fig. 1).

Figure 3. Correlations of Symptom Severity with Surface Features of the Basal Ganglia in Youth with ADHD.

Correlation of surface measures with total ADHD symptom severity. The color bar depicts the P-value for the partial Pearson correlation coefficient, r, with the p-value ranging from P<0.0001 in red (highly significant positive correlation) to P<0.0001 in purple (highly significant inverse correlations).

Possible Confounds

In the analyses for conventional volumes and surface features, we did not discern appreciable effects of comorbid illness (Table 2, Supplemental Material) or medication duration (not shown) on our findings. The main effect of diagnosis was similar in an analysis of boys only (not shown). We did not detect significant interactions of diagnosis with age or diagnosis with sex (not shown), indicating that the effect of diagnosis was stable across age and sex.

DISCUSSION

Analyses of overall conventional volumes detected differences between ADHD youth and healthy controls only in the putamen. Surface analyses demonstrated that this reduced volume derived from local inward deformations in most portions of the surface of the putamen, and they further identified significant inward deformations in the caudate and globus pallidus. Many of the locations of these inward deformations in the ADHD group corresponded with locations where overall symptom severity correlated significantly with local inward deformations, with more pronounced inward deformations accompanying more severe symptoms. Surface analyses also demonstrated that outward deformations of these nuclei were associated with the ADHD youth treated with stimulants compared to those with ADHD who were untreated at the time of the scan, in locations similar to those where inward deformations were detected in the ADHD youth relative to controls.

The decreased conventional volume of the putamen in the ADHD group is consistent with findings from previous anatomical imaging studies of ADHD(6–8). In addition, the similarity in conventional volumes of the caudate across groups corroborates the findings from several other studies that also controlled for scaling effects by covarying in their analyses for whole-brain volume(3, 17–19). Our finding that globus pallidus volumes were similar between diagnostic groups conflicts with findings of reduced globus pallidus volumes reported in a study of a demographically similar cohort(18), although our improved signal-to-noise characteristics (accomplished with two signal averages during image acquisition compared with one in prior studies) and our better spatial resolution (1.2 mm slice thickness here compared with 2mm previously) likely improved the precision and accuracy of our anatomical measurements. Finally, the findings of our analyses comparing surface morphology across groups are consistent with those from a recent study of ADHD youth that employed similar analytic procedures(9). That study reported reductions in overall conventional volumes across all three basal ganglia nuclei, as well as inward deformations across the surfaces of all three nuclei, particularly in the anterior portions and midbodies of each structure. The similarity of results across studies corroborates the existence of structural disturbances within the basal ganglia of individuals with ADHD.

Our surface analyses provide a degree of spatial detail of the basal ganglia nuclei that overall conventional volume measures cannot provide, permitting us to identify highly localized anatomical disturbances in these nuclei and allowing us to infer the presence of corresponding disturbances in the anatomical pathways that contain those regional abnormalities in youth with ADHD. Neuroanatomical tracing studies in animals(20–25), as well as diffusion tensor imaging(26) and functional connectivity studies(27) in humans, suggest that ventral, anterior, and posterior portions of the putamen, caudate, and globus pallidus can be partitioned topographically into limbic, associative, and sensorimotor systems, respectively, based on the topographically organized input to these nuclei from cortical and subcortical areas and on the topographically organized projections that these nuclei send back to cortical areas via the thalamus.

We detected inward deformations located in the limbic (primarily ventral) portions of the basal ganglia nuclei in ADHD youth, consistent with prior studies of persons with ADHD that report abnormalities in limbic structures, such as the orbital frontal cortex (OFC) and amygdala(14, 28). The limbic portions of the putamen, caudate, and globus pallidus connect anatomically and interact functionally with the OFC, amygdala, and nucleus accumbens to form the distributed limbic neural circuit that guides reinforcement-based learning (the acquisition and selection of appropriate behavior)(29–32). Therefore, morphological aberrations in the limbic circuits that support reinforcement learning(33–35) may account for the difficulties that ADHD youth have with delayed gratification and with selecting inappropriate behaviors in a given environmental context. The inward deformations that were located generally in the associative (anterior) portions of the basal ganglia nuclei, combined with a prior report of thinning in the lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) in ADHD youth(5), may represent an altered associative neural circuit in persons with ADHD. Given that the associative portions of the basal ganglia nuclei and the LPFC together guide executive functioning(36–38), the behavioral consequence of an altered neural circuit for associative learning likely includes impaired executive functioning, which is arguably the hallmark of ADHD(39–41). The inward deformations located generally in the sensorimotor (primarily posterior) portions of the basal ganglia nuclei accord well with other reports of anatomical abnormalities in the sensorimotor cortices of ADHD youth(42, 43). The sensorimotor portions of the basal ganglia, together with the sensorimotor cortex, drive motor learning and control(44–48). Deficits in the sensorimotor neural circuit may underlie the dysfunction in fine and gross motor control, and the impairments in learning and execution of complex motor behaviors, that are characteristic of ADHD(39, 49–53).

Although the neurobiological mechanisms that cause inward deformations of the basal ganglia in the ADHD youth are unknown, one possibility is that dopamine dysfunction in ADHD may alter local cytoarchitecture within basal ganglia nuclei. Several candidate genes related to dopamine neurotransmission have been associated with ADHD(54). One of these, the dopamine-transporter gene, removes dopamine from the synaptic cleft through a reuptake mechanism(55). Abnormally high levels of dopamine-transporter gene reported in persons with ADHD(56–59) may diminish concentrations of synaptic dopamine. The basal ganglia may be particularly sensitive to diminished levels of dopamine, as these nuclei receive substantial projections from midbrain-dopamine afferents (60) and contain the largest relative concentration of dopamine-transporter gene in the brain(61, 62). Indeed, prior studies of the histological features of the basal ganglia in animals(63–66) and humans(64, 67, 68) suggest that deficits in dopamine concentrations produce anatomical alterations in basal ganglia neurons, including reductions in the number of synapses, decreases in the density of dendrite spines, and decreases in dendritic arborization and length. These cellular changes, when affecting large-scale populations of neurons in the basal ganglia, could produce the local volume reductions of the basal ganglia that we detected in the ADHD group. Moreover, this putative mechanism could also account for the location of the most prominent volume reductions in the putamen, which is the largest recipient of midbrain-dopamine afferents of all the basal ganglia nuclei(62, 69, 70). An exquisite modulation of the basal ganglia by dopamine supports the acquisition and execution of a broad range of behavioral actions that are orchestrated by limbic, associative, and sensorimotor basal ganglia circuits(71–73). Thus the local volume reductions that span the limbic, associative, and sensorimotor portions of the basal ganglia nuclei may be associated with the heterogeneous symptoms of ADHD, which include context-inappropriate behaviors, deficits in working memory, and impaired motor control(35, 74–76).

If local volume reductions of the basal ganglia in persons with ADHD reflect the morphological modifications that occur in response to a deficit in dopamine, then the local volume increases of the basal ganglia in the youth with ADHD who are treated with stimulants may represent the morphological changes that occur in response to the relative improvement in dopamine levels that the stimulants produce. Indeed, previous imaging studies in youth with ADHD demonstrate an association between stimulant treatment and normalized grey matter volume in various brain regions(77–79). Stimulants bind to and block dopamine-transporter gene, effectively increasing synaptic and extracellular dopamine levels(80, 81). Therefore, stimulants may alleviate the deleterious cellular effects that the deficit of dopamine has on target basal ganglia neurons in untreated persons with ADHD. Although the exact anatomical modifications produced by a stimulant-induced increase in dopamine in humans are unknown, animal studies suggest that stimulants induce changes in gene expression and dendritic architecture within the basal ganglia, in a direction opposite to that seen with deficient dopamine(82–86). Thus, the significant local volume reductions of the basal ganglia in the ADHD group not taking stimulants, and the attenuation of these reductions in those youth on stimulants, may reflect the architectural modifications that occur in response to deficient and relatively corrected dopamine concentrations, respectively.

Limitations

Although we cannot exclude entirely the possibility that co-occurring illnesses, sex or age effects influenced our findings, including these effects as covariates in our statistical models and conducting separate analyses of ADHD subgroups indicated that these effects did not appreciably affected our findings. In addition, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes strong inferences that the morphological abnormalities of the BG represented either the causes or consequences of ADHD. The cross-sectional design similarly precludes strong inferences that the seeming morphological “normalizing” effects of stimulant medications represented the direct effects of stimulant medications on the BG or indirect influences from their effects on regions that are connected with the BG, and even whether the effects represented some sort of ascertainment bias related to unknown clinical features that determined which participants were or were not taking stimulant medications. Longitudinal imaging studies of ADHD youth that are combined with randomized studies of stimulant medications are needed to identify more conclusively the causal effects that ADHD and stimulant medications have on the morphology of BG nuclei.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIMH grants MH59139, MH068318, and K02-74677, a grant from the Tourette Syndrome Association, and by a grant from the Klingenstein Third Generation Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Sagvolden T, Russell VA, Aase H, Johansen EB, Farshbaf M. Rodent models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1239–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plessen K, Peterson BS. The Neurobiology of Impulsivity and Self-Regulatory Control in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. In: Charney D, Nestler E, editors. Neurobiology of Mental Illness. 3. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 1129–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castellanos FX, Lee PP, Sharp W, Jeffries NO, Greenstein DK, Clasen LS, Blumenthal JD, James RS, Ebens CL, Walter JM, Zijdenbos A, Evans AC, Giedd JN, Rapoport JL. Developmental trajectories of brain volume abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1740–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw P, Lerch J, Greenstein D, Sharp W, Clasen L, Evans A, Giedd J, Castellanos FX, Rapoport J. Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and clinical outcome in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):540–549. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, Toga AW, Peterson BS. Cortical abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2003;362(9397):1699–1707. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14842-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAlonan GM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Chua SE, Murphy DG, Suckling J, Tai KS, Yip LK, Leung P, Ho TP. Mapping brain structure in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder: a voxel-based MRI study of regional grey and white matter volume. Psychiatry Res. 2007;154(2):171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overmeyer S, Bullmore ET, Suckling J, Simmons A, Williams SC, Santosh PJ, Taylor E. Distributed grey and white matter deficits in hyperkinetic disorder: MRI evidence for anatomical abnormality in an attentional network. Psychol Med. 2001;31(8):1425–1435. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, Jiang T, Cao Q, Wang Y. Characterizing anatomic differences in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with the use of deformation-based morphometry. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(3):543–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu A, Crocetti D, Adler M, Mahone EM, Denckla MB, Miller MI, Mostofsky SH. Basal Ganglia Volume and Shape in Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barkley RA, DuPaul GJ, McMurray MB. Attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity: clinical response to three dose levels of methylphenidate. Pediatrics. 1991;87(4):519–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bansal R, Staib LH, Whiteman R, Wang YM, Peterson BS. ROC-based assessments of 3D cortical surface-matching algorithms. Neuroimage. 2005;24(1):150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bansal R, Staib LH, Xu D, Zhu H, Peterson BS. Statistical analyses of brain surfaces using Gaussian random fields on 2-D manifolds. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26(1):46–57. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.884187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plessen KJ, Bansal R, Zhu H, Whiteman R, Amat J, Quackenbush GA, Martin L, Durkin K, Blair C, Royal J, Hugdahl K, Peterson BS. Hippocampus and amygdala morphology in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):795–807. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson BS, Choi HA, Hao X, Amat JA, Zhu H, Whiteman R, Liu J, Xu D, Bansal R. Morphologic features of the amygdala and hippocampus in children and adults with Tourette syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(11):1281–1291. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.11.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor JAR. Euler characteristics for guassian fields on manifolds. The Annals of Probability. 2003;31(2):533–563. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aylward EH, Reiss AL, Reader MJ, Singer HS, Brown JE, Denckla MB. Basal ganglia volumes in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Neurol. 1996;11(2):112–115. doi: 10.1177/088307389601100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castellanos FX, Giedd JN, Marsh WL, Hamburger SD, Vaituzis AC, Dickstein DP, Sarfatti SE, Vauss YC, Snell JW, Lange N, Kaysen D, Krain AL, Ritchie GF, Rajapakse JC, Rapoport JL. Quantitative brain magnetic resonance imaging in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(7):607–616. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830070053009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castellanos FX, Giedd JN, Berquin PC, Walter JM, Sharp W, Tran T, Vaituzis AC, Blumenthal JD, Nelson J, Bastain TM, Zijdenbos A, Evans AC, Rapoport JL. Quantitative brain magnetic resonance imaging in girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(3):289–295. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parent A, Hazrati LN. Functional anatomy of the basal ganglia. I. The cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1995;20(1):91–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)00007-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selemon LD, Goldman-Rakic PS. Longitudinal topography and interdigitation of corticostriatal projections in the rhesus monkey. J Neurosci. 1985;5(3):776–794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-03-00776.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakano K, Kayahara T, Tsutsumi T, Ushiro H. Neural circuits and functional organization of the striatum. J Neurol. 2000;247 (Suppl 5):V1–15. doi: 10.1007/pl00007778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haber SN. The primate basal ganglia: parallel and integrative networks. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;26(4):317–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morel A, Loup F, Magnin M, Jeanmonod D. Neurochemical organization of the human basal ganglia: anatomofunctional territories defined by the distributions of calcium-binding proteins and SMI-32. J Comp Neurol. 2002;443(1):86–103. doi: 10.1002/cne.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehericy S, Ducros M, Van de Moortele PF, Francois C, Thivard L, Poupon C, Swindale N, Ugurbil K, Kim DS. Diffusion tensor fiber tracking shows distinct corticostriatal circuits in humans. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(4):522–529. doi: 10.1002/ana.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Postuma RB, Dagher A. Basal ganglia functional connectivity based on a meta-analysis of 126 positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging publications. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(10):1508–1521. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hesslinger B, Tebartz van Elst L, Thiel T, Haegele K, Hennig J, Ebert D. Frontoorbital volume reductions in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neurosci Lett. 2002;328(3):319–321. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollerman JR, Tremblay L, Schultz W. Involvement of basal ganglia and orbitofrontal cortex in goal-directed behavior. Prog Brain Res. 2000;126:193–215. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)26015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baxter MG, Murray EA. The amygdala and reward. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(7):563–573. doi: 10.1038/nrn875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Doherty JP, Deichmann R, Critchley HD, Dolan RJ. Neural responses during anticipation of a primary taste reward. Neuron. 2002;33(5):815–826. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pasupathy A, Miller EK. Different time courses of learning-related activity in the prefrontal cortex and striatum. Nature. 2005;433(7028):873–876. doi: 10.1038/nature03287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aase H, Sagvolden T. Infrequent, but not frequent, reinforcers produce more variable responding and deficient sustained attention in young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(5):457–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aase H, Meyer A, Sagvolden T. Moment-to-moment dynamics of ADHD behaviour in South African children. Behav Brain Funct. 2006;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank MJ, Santamaria A, O’Reilly RC, Willcutt E. Testing computational models of dopamine and noradrenaline dysfunction in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(7):1583–1599. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao SM, Mayer AR, Harrington DL. The evolution of brain activation during temporal processing. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(3):317–323. doi: 10.1038/85191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka SC, Doya K, Okada G, Ueda K, Okamoto Y, Yamawaki S. Prediction of immediate and future rewards differentially recruits cortico-basal ganglia loops. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(8):887–893. doi: 10.1038/nn1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNab F, Klingberg T. Prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia control access to working memory. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(1):103–107. doi: 10.1038/nn2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol Bull. 1997;121(1):65–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toplak ME, Dockstader C, Tannock R. Temporal information processing in ADHD: findings to date and new methods. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;151(1):15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swanson JM, Kinsbourne M, Nigg J, Lanphear B, Stefanatos GA, Volkow N, Taylor E, Casey BJ, Castellanos FX, Wadhwa PD. Etiologic subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: brain imaging, molecular genetic and environmental factors and the dopamine hypothesis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17(1):39–59. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carmona S, Vilarroya O, Bielsa A, Tremols V, Soliva JC, Rovira M, Tomas J, Raheb C, Gispert JD, Batlle S, Bulbena A. Global and regional gray matter reductions in ADHD: a voxel-based morphometric study. Neurosci Lett. 2005;389(2):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mostofsky SH, Cooper KL, Kates WR, Denckla MB, Kaufmann WE. Smaller prefrontal and premotor volumes in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(8):785–794. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Graybiel AM, Aosaki T, Flaherty AW, Kimura M. The basal ganglia and adaptive motor control. Science. 1994;265(5180):1826–1831. doi: 10.1126/science.8091209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jueptner M, Frith CD, Brooks DJ, Frackowiak RS, Passingham RE. Anatomy of motor learning. II. Subcortical structures and learning by trial and error. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77(3):1325–1337. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerardin E, Pochon JB, Poline JB, Tremblay L, Van de Moortele PF, Levy R, Dubois B, Le Bihan D, Lehericy S. Distinct striatal regions support movement selection, preparation and execution. Neuroreport. 2004;15(15):2327–2331. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200410250-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lehericy S, Benali H, Van de Moortele PF, Pelegrini-Issac M, Waechter T, Ugurbil K, Doyon J. Distinct basal ganglia territories are engaged in early and advanced motor sequence learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(35):12566–12571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502762102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poldrack RA, Sabb FW, Foerde K, Tom SM, Asarnow RF, Bookheimer SY, Knowlton BJ. The neural correlates of motor skill automaticity. J Neurosci. 2005;25(22):5356–5364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3880-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pitcher TM, Piek JP, Hay DA. Fine and gross motor ability in males with ADHD. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45(8):525–535. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203000975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piek JP, Pitcher TM, Hay DA. Motor coordination and kinaesthesis in boys with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41(3):159–165. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fliers E, Rommelse N, Vermeulen SH, Altink M, Buschgens CJ, Faraone SV, Sergeant JA, Franke B, Buitelaar JK. Motor coordination problems in children and adolescents with ADHD rated by parents and teachers: effects of age and gender. J Neural Transm. 2008;115(2):211–220. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0827-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mostofsky SH, Rimrodt SL, Schafer JG, Boyce A, Goldberg MC, Pekar JJ, Denckla MB. Atypical motor and sensory cortex activation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study of simple sequential finger tapping. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(1):48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dockstader C, Gaetz W, Cheyne D, Wang F, Castellanos FX, Tannock R. MEG event-related desynchronization and synchronization deficits during basic somatosensory processing in individuals with ADHD. Behav Brain Funct. 2008;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bobb AJ, Castellanos FX, Addington AM, Rapoport JL. Molecular genetic studies of ADHD: 1991 to 2004. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;132(1):109–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hitri A, Hurd YL, Wyatt RJ, Deutsch SI. Molecular, functional and biochemical characteristics of the dopamine transporter: regional differences and clinical relevance. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1994;17(1):1–22. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199402000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dougherty DD, Bonab AA, Spencer TJ, Rauch SL, Madras BK, Fischman AJ. Dopamine transporter density in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 1999;354(9196):2132–2133. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krause KH, Dresel SH, Krause J, Kung HF, Tatsch K. Increased striatal dopamine transporter in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of methylphenidate as measured by single photon emission computed tomography. Neurosci Lett. 2000;285(2):107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dresel S, Krause J, Krause KH, LaFougere C, Brinkbaumer K, Kung HF, Hahn K, Tatsch K. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: binding of [99mTc]TRODAT-1 to the dopamine transporter before and after methylphenidate treatment. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27(10):1518–1524. doi: 10.1007/s002590000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheon KA, Ryu YH, Kim YK, Namkoong K, Kim CH, Lee JD. Dopamine transporter density in the basal ganglia assessed with [123I]IPT SPET in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30(2):306–311. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith Y, Kieval JZ. Anatomy of the dopamine system in the basal ganglia. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23(10 Suppl):S28–33. doi: 10.1016/s1471-1931(00)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Donnan GA, Kaczmarczyk SJ, McKenzie JS, Kalnins RM, Chilco PJ, Mendelsohn FA. Catecholamine uptake sites in mouse brain: distribution determined by quantitative [3H]mazindol autoradiography. Brain Res. 1989;504(1):64–71. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91598-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Donnan GA, Kaczmarczyk SJ, Paxinos G, Chilco PJ, Kalnins RM, Woodhouse DG, Mendelsohn FA. Distribution of catecholamine uptake sites in human brain as determined by quantitative [3H] mazindol autoradiography. J Comp Neurol. 1991;304(3):419–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.903040307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Solis O, Limon DI, Flores-Hernandez J, Flores G. Alterations in dendritic morphology of the prefrontal cortical and striatum neurons in the unilateral 6-OHDA-rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Synapse. 2007;61(6):450–458. doi: 10.1002/syn.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jan C, Francois C, Tande D, Yelnik J, Tremblay L, Agid Y, Hirsch E. Dopaminergic innervation of the pallidum in the normal state, in MPTP-treated monkeys and in parkinsonian patients. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(12):4525–4535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mounayar S, Boulet S, Tande D, Jan C, Pessiglione M, Hirsch EC, Feger J, Savasta M, Francois C, Tremblay L. A new model to study compensatory mechanisms in MPTP-treated monkeys exhibiting recovery. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 11):2898–2914. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Day M, Wang Z, Ding J, An X, Ingham CA, Shering AF, Wokosin D, Ilijic E, Sun Z, Sampson AR, Mugnaini E, Deutch AY, Sesack SR, Arbuthnott GW, Surmeier DJ. Selective elimination of glutamatergic synapses on striatopallidal neurons in Parkinson disease models. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(2):251–259. doi: 10.1038/nn1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Neill J, Schuff N, Marks WJ, Jr, Feiwell R, Aminoff MJ, Weiner MW. Quantitative 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy and MRI of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17(5):917–927. doi: 10.1002/mds.10214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Geng DY, Li YX, Zee CS. Magnetic resonance imaging-based volumetric analysis of basal ganglia nuclei and substantia nigra in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(2):256–262. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000194845.19462.7B. discussion 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Madras BK, Gracz LM, Fahey MA, Elmaleh D, Meltzer PC, Liang AY, Stopa EG, Babich J, Fischman AJ. Altropane, a SPECT or PET imaging probe for dopamine neurons: III. Human dopamine transporter in postmortem normal and Parkinson’s diseased brain. Synapse. 1998;29(2):116–127. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199806)29:2<116::AID-SYN3>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller GW, Staley JK, Heilman CJ, Perez JT, Mash DC, Rye DB, Levey AI. Immunochemical analysis of dopamine transporter protein in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;41(4):530–539. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Graybiel AM. Basal ganglia--input, neural activity, and relation to the cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1991;1(4):644–651. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(05)80043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275(5306):1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wickens JR, Horvitz JC, Costa RM, Killcross S. Dopaminergic mechanisms in actions and habits. J Neurosci. 2007;27(31):8181–8183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1671-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tripp G, Wickens JR. Dopamine transfer deficit: A neurobiological theory of altered reinforcement mechanisms in ADHD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sagvolden T, Johansen EB, Aase H, Russell VA. A dynamic developmental theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) predominantly hyperactive/impulsive and combined subtypes. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28(3):397–419. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000075. discussion 419–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams ZM, Eskandar EN. Selective enhancement of associative learning by microstimulation of the anterior caudate. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(4):562–568. doi: 10.1038/nn1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Psychostimulant treatment and the developing cortex in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Volumetric MRI differences in treatment-naïve vs chronically treated children with ADHD. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.A magnetic resonance imaging study of the cerebellar vermis in chronically treated and treatment-naïve children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder combined type. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Ding YS. Imaging the effects of methylphenidate on brain dopamine: new model on its therapeutic actions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1410–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schiffer WK, Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Alexoff DL, Logan J, Dewey SL. Therapeutic doses of amphetamine or methylphenidate differentially increase synaptic and extracellular dopamine. Synapse. 2006;59(4):243–251. doi: 10.1002/syn.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Abrous DN, Desjardins S, Sorin B, Hancock D, Le Moal M, Herman JP. Changes in striatal immediate early gene expression following neonatal dopaminergic lesion and effects of intrastriatal dopaminergic transplants. Neuroscience. 1996;73(1):145–159. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yano M, Beverley JA, Steiner H. Inhibition of methylphenidate-induced gene expression in the striatum by local blockade of D1 dopamine receptors: interhemispheric effects. Neuroscience. 2006;140(2):699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mazei MS, Pluto CP, Kirkbride B, Pehek EA. Effects of catecholamine uptake blockers in the caudate-putamen and subregions of the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Brain Res. 2002;936(1–2):58–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li Y, Kolb B, Robinson TE. The location of persistent amphetamine-induced changes in the density of dendritic spines on medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens and caudate-putamen. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(6):1082–1085. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Robinson TE, Kolb B. Persistent structural modifications in nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex neurons produced by previous experience with amphetamine. J Neurosci. 1997;17(21):8491–8497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08491.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]