Abstract

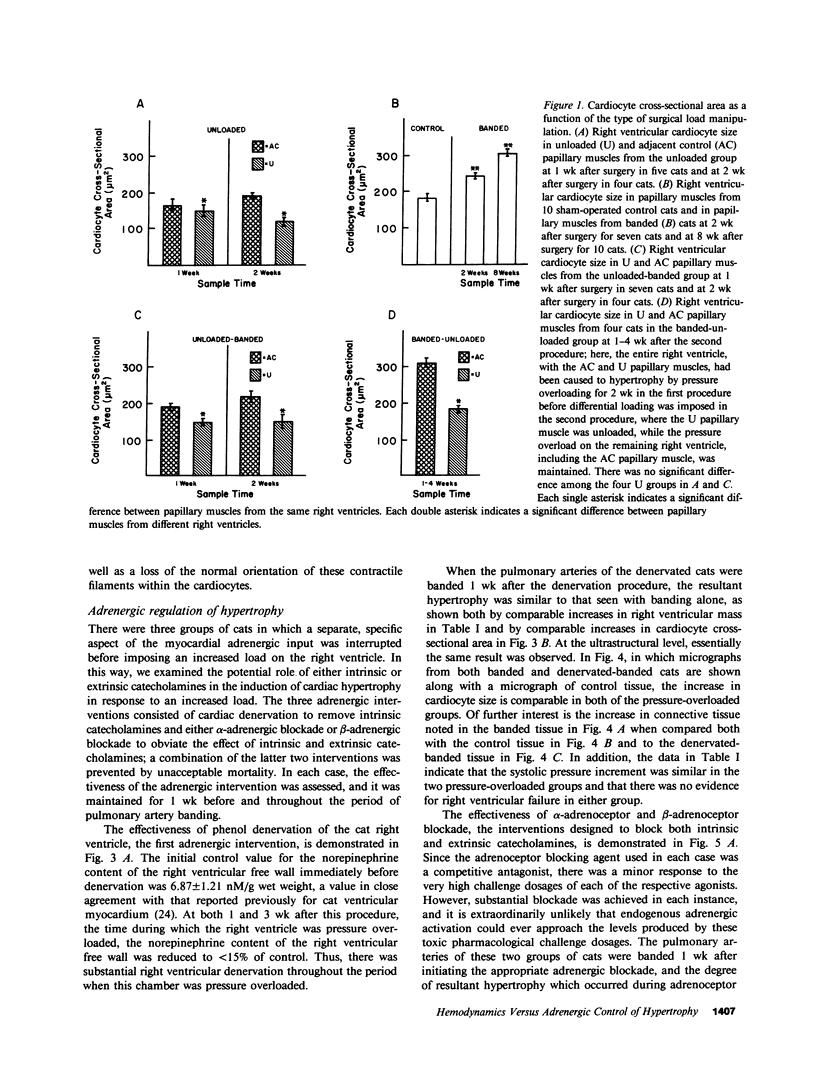

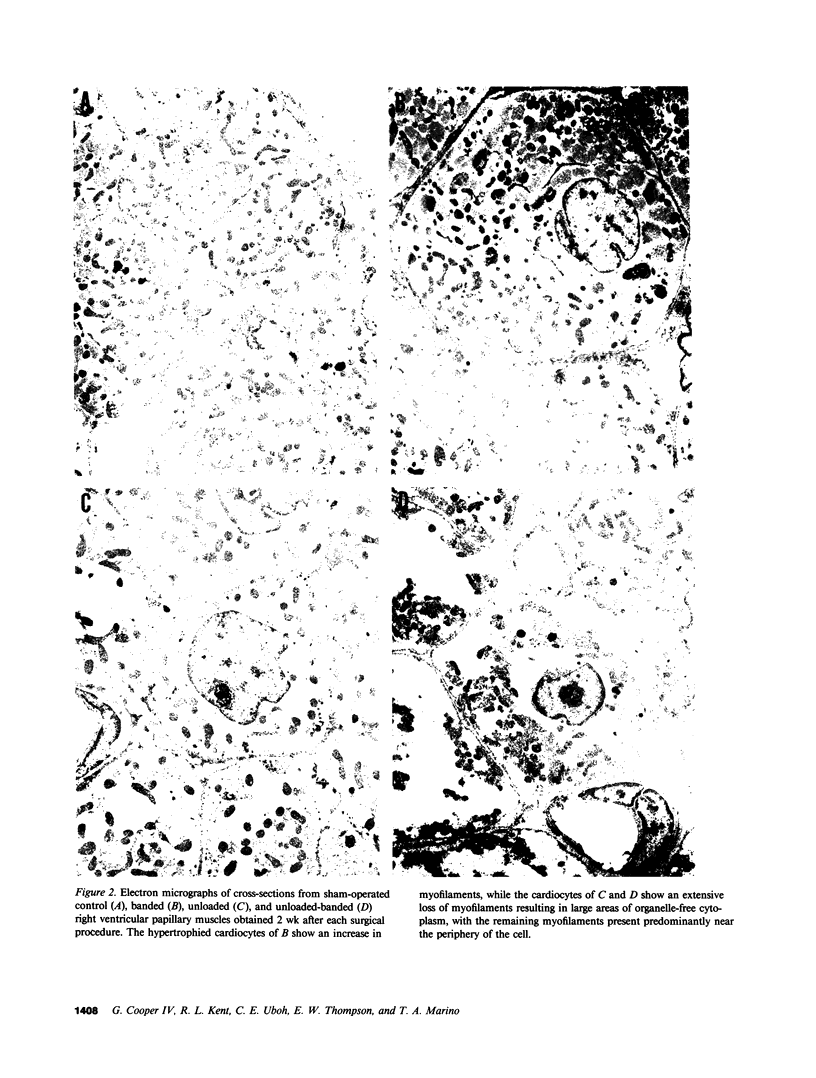

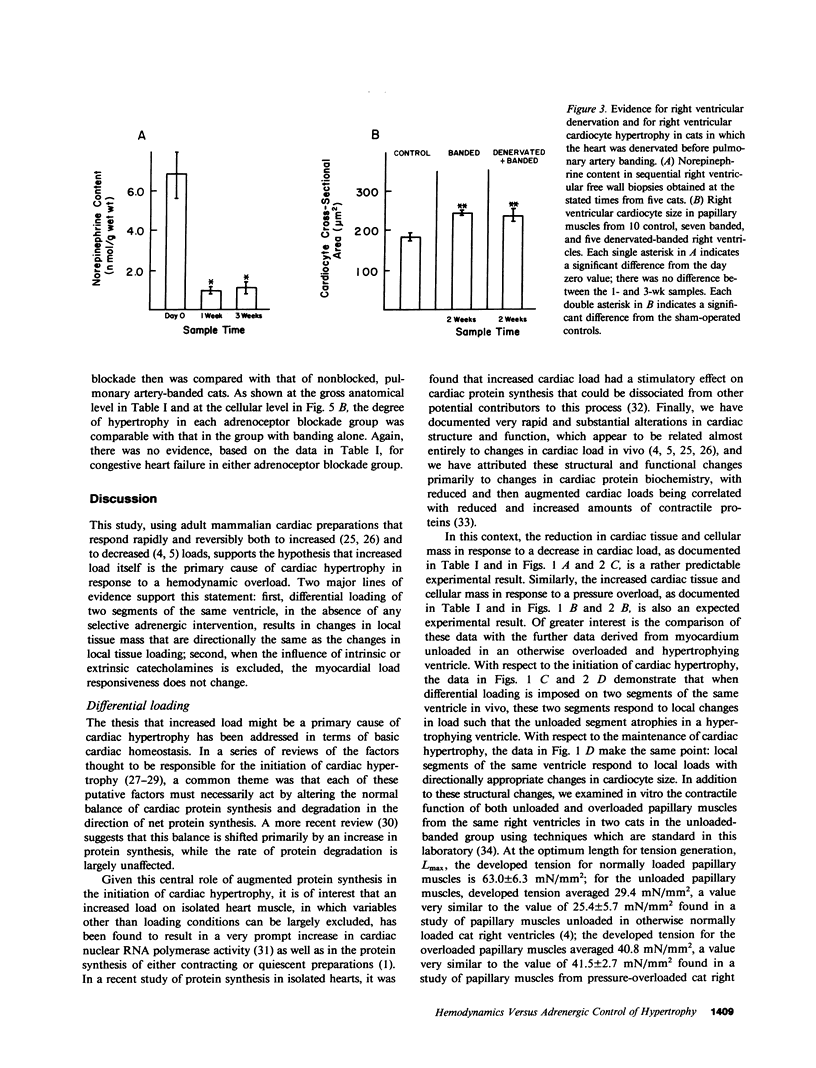

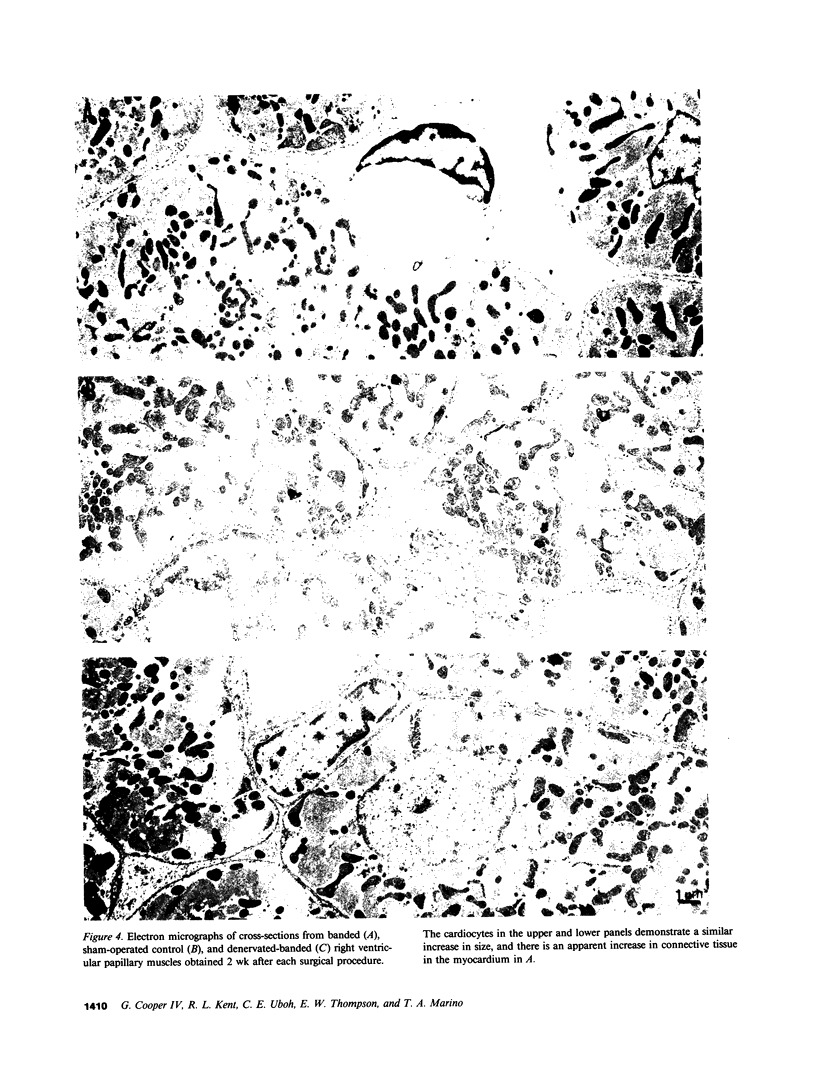

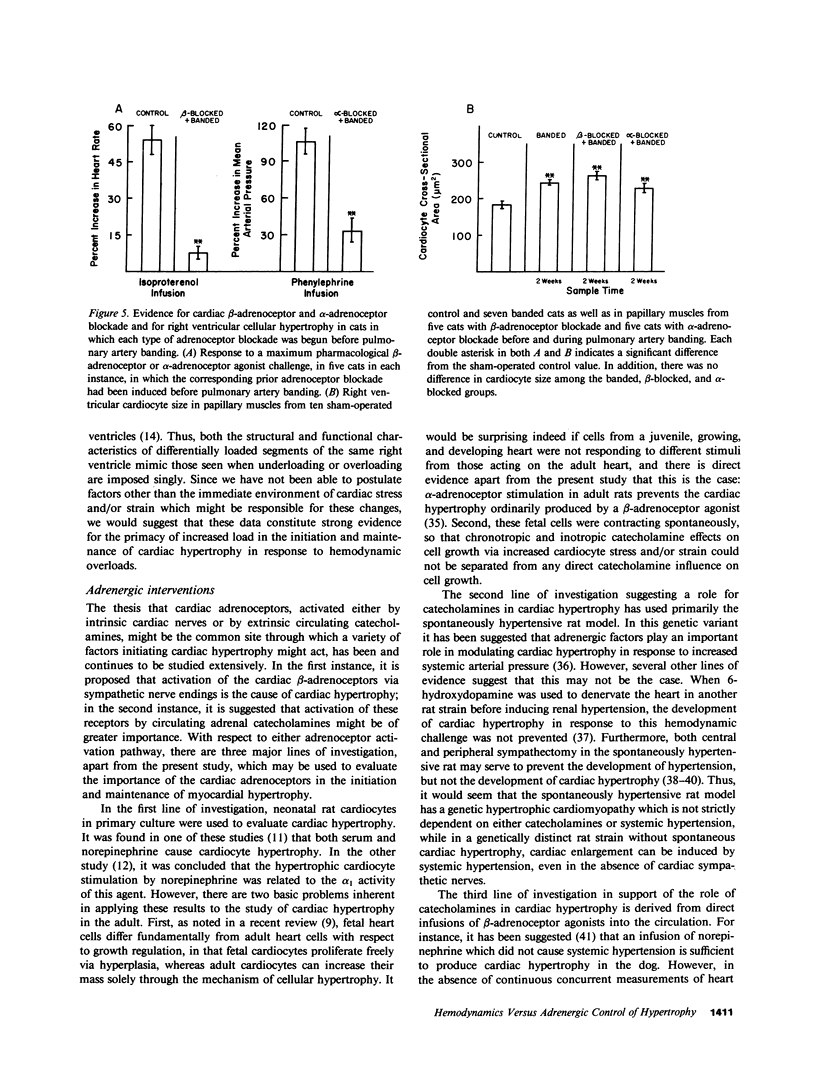

The purpose of this study was to determine whether cardiac hypertrophy in response to hemodynamic overloading is a primary result of the increased load or is instead a secondary result of such other factors as concurrent sympathetic activation. To make this distinction, four experiments were done; the major experimental result, cardiac hypertrophy, was assessed in terms of ventricular mass and cardiocyte cross-sectional area. In the first experiment, the cat right ventricle was loaded differentially by pressure overloading the ventricle, while unloading a constituent papillary muscle; this model was used to ask whether any endogenous or exogenous substance caused uniform hypertrophy, or whether locally appropriate load responses caused ventricular hypertrophy with papillary muscle atrophy. The latter result obtained, both when each aspect of differential loading was simultaneous and when a previously hypertrophied papillary muscle was unloaded in a pressure overloaded right ventricle. In the second experiment, epicardial denervation and then pressure overloading was used to assess the role of local neurogenic catecholamines in the genesis of hypertrophy. The degree of hypertrophy caused by these procedures was the same as that caused by pressure overloading alone. In the third and fourth experiments, beta-adrenoceptor or alpha-adrenoceptor blockade was produced before and maintained during pressure overloading. The hypertrophic response did not differ in either case from that caused by pressure overloading without adrenoceptor blockade. These experiments demonstrate the following: first, cardiac hypertrophy is a local response to increased load, so that any factor serving as a mediator of this response must be either locally generated or selectively active only in those cardiocytes in which stress and/or strain are increased; second, catecholamines are not that mediator, in that adrenergic activation is neither necessary for nor importantly modifies the cardiac hypertrophic response to an increased hemodynamic load.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ANTON A. H., SAYRE D. F. A study of the factors affecting the aluminum oxide-trihydroxyindole procedure for the analysis of catecholamines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1962 Dec;138:360–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G., 4th Influence of length changes on myocardial metabolism in the cat papillary muscle. Circ Res. 1981 Aug;49(2):423–433. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G., 4th, Marino T. A. Complete reversibility of cat right ventricular chronic progressive pressure overload. Circ Res. 1984 Mar;54(3):323–331. doi: 10.1161/01.res.54.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G., 4th, Satava R. M., Jr, Harrison C. E., Coleman H. N., 3rd Mechanisms for the abnormal energetics of pressure-induced hypertrophy of cat myocardium. Circ Res. 1973 Aug;33(2):213–223. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G., 4th, Tomanek R. J., Ehrhardt J. C., Marcus M. L. Chronic progressive pressure overload of the cat right ventricle. Circ Res. 1981 Apr;48(4):488–497. doi: 10.1161/01.res.48.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G., 4th, Tomanek R. J. Load regulation of the structure, composition, and function of mammalian myocardium. Circ Res. 1982 Jun;50(6):788–798. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.6.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutilletta A. F., Erinoff L., Heller A., Low J., Oparil S. Development of left ventricular hypertrophy in young spontaneously hypertensive rats after peripheral sympathectomy. Circ Res. 1977 Apr;40(4):428–434. doi: 10.1161/01.res.40.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis P., Vaughan Williams E. M. Hypoxic cardiac hypertrophy is not inhibited by cardioselective or non-selective beta-adrenoceptor antagonists. J Physiol. 1982 Mar;324:365–374. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felice L. J., Felice J. D., Kissinger P. T. Determination of catecholamines in rat brain parts by reverse-phase ion-pair liquid chromatography. J Neurochem. 1978 Dec;31(6):1461–1465. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1978.tb06573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond G. L., Lai Y. K., Markert C. L. The molecules that initiate cardiac hypertrophy are not species-specific. Science. 1982 Apr 30;216(4545):529–531. doi: 10.1126/science.6461921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickson R. C., Galassi T. M., Kurowski T. T., Daniels D. G., Chatterton R. T., Jr Androgen and glucocorticoid mechanisms in exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol. 1984 Jun;246(6 Pt 2):H761–H767. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.6.H761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobowitz D., Cooper T., Barner H. B. Histochemical and chemical studies of the localization of adrenergic and cholinergic nerves in normal and denervated cat hearts. Circ Res. 1967 Mar;20(3):289–298. doi: 10.1161/01.res.20.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye M. P., Brynjolfsson G. G., Geis W. P. Chemical epicardiectomy. A method of myocardial denervaion. Cardiologia. 1968;53(3):139–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye M. P., Randall W. C., Hageman G. R., Geis W. P., Priola D. V. Chronology and mode of reinnervation of the surgically denervated canine heart: functional and chemical correlates. Am J Physiol. 1977 Oct;233(4):H431–H437. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1977.233.4.H431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller R., Oke A., Mefford I., Adams R. N. Liquid chromatographic analysis of catecholamines routine assay for regional brain mapping. Life Sci. 1976 Oct 1;19(7):995–1003. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(76)90290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kira Y., Kochel P. J., Gordon E. E., Morgan H. E. Aortic perfusion pressure as a determinant of cardiac protein synthesis. Am J Physiol. 1984 Mar;246(3 Pt 1):C247–C258. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1984.246.3.C247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kölbel F., Schreiber V. Biochemical regulators in cardiac hypertrophy. Basic Res Cardiol. 1983 Jul-Aug;78(4):351–363. doi: 10.1007/BF02070160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laks M. M., Morady F., Swan H. J. Myocardial hypertrophy produced by chronic infusion of subhypertensive doses of norepinephrine in the dog. Chest. 1973 Jul;64(1):75–78. doi: 10.1378/chest.64.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. C., Lew J. M., Yoo C. S. Studies on myocardial catecholamines related to species ages and sex. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1970 Jun;185(2):259–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino T. A., Houser S. R., Cooper G., 4th Early morphological alterations of pressure-overloaded cat right ventricular myocardium. Anat Rec. 1983 Nov;207(3):417–426. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092070304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino T. A., Houser S. R., Martin F. G., Freeman A. R. An ultrastructural morphometric study of the papillary muscle of the right ventricle of the cat. Cell Tissue Res. 1983;230(3):543–552. doi: 10.1007/BF00216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins J. B., Zipes D. P. Epicardial phenol interrupts refractory period responses to sympathetic but not vagal stimulation in canine left ventricular epicardium and endocardium. Circ Res. 1980 Jul;47(1):33–40. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matoba T., Adachi K., Ito T., Yamashita Y., Chiba M., Odawara K., Inuzuka S., Toshima H. Cardiac hypertrophy in surgically denervated dogs with aortic stenosis. Experientia. 1984 Jan 15;40(1):73–75. doi: 10.1007/BF01959108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J. R., Clancy R. L., Gonzalez N. C. Role of adrenals on development of pressure-induced myocardial hypertrophy. Am J Physiol. 1983 Feb;244(2):H234–H238. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.2.H234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oparil S., Cutilletta A. F. Hypertrophy in the denervated heart: a comparison of central sympatholytic treatment with 6-hydroxydopamine and peripheral sympathectomy with nerve growth factor antiserum. Am J Cardiol. 1979 Oct 22;44(5):970–978. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(79)90231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostman-Smith I. Adaptive changes in the sympathetic nervous system and some effector organs of the rat following long term exercise or cold acclimation and the role of cardiac sympathetic nerves in the genesis of compensatory cardiac hypertrophy. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1979;477:1–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostman-Smith I. Cardiac sympathetic nerves as the final common pathway in the induction of adaptive cardiac hypertrophy. Clin Sci (Lond) 1981 Sep;61(3):265–272. doi: 10.1042/cs0610265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano V. T., Inchiosa M. A., Jr Cardiomegaly produced by chronic beta-adrenergic stimulation in the rat: comparison with alpha-adrenergic effects. Life Sci. 1977 Sep 1;21(5):619–624. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(77)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson M. B., Lesch M. Protein synthesis and amino acid transport in the isolated rabbit right ventricular papillary muscle. Effect of isometric tension development. Circ Res. 1972 Sep;31(3):317–327. doi: 10.1161/01.res.31.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REYNOLDS E. S. The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron-opaque stain in electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1963 Apr;17:208–212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S. S., Evans C. D., Oratz M., Rothschild M. A. Protein synthesis and degradation in cardiac stress. Circ Res. 1981 May;48(5):601–611. doi: 10.1161/01.res.48.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S. S., Oratz M., Rothschild M. A. Nuclear RNA polymerase activity in acute hemodynamic overload in the perfused heart. Am J Physiol. 1969 Nov;217(5):1305–1309. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.217.5.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S., Tarazi R. C. Regression of myocardial hypertrophy and influence of adrenergic system. Am J Physiol. 1983 Jan;244(1):H97–101. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.1.H97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P., McGrath A., Savion S. Myocyte hypertrophy in neonatal rat heart cultures and its regulation by serum and by catecholamines. Circ Res. 1982 Dec;51(6):787–801. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.6.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P. Norepinephrine-stimulated hypertrophy of cultured rat myocardial cells is an alpha 1 adrenergic response. J Clin Invest. 1983 Aug;72(2):732–738. doi: 10.1172/JCI111023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J. Stretch stimulates cyclic nucleotide metabolism in the isolated frog ventricle. Pflugers Arch. 1982 Nov 1;395(2):162–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00584732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E. W., Marino T. A., Uboh C. E., Kent R. L., Cooper G., 4th Atrophy reversal and cardiocyte redifferentiation in reloaded cat myocardium. Circ Res. 1984 Apr;54(4):367–377. doi: 10.1161/01.res.54.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATSON M. L. Staining of tissue sections for electron microscopy with heavy metals. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1958 Jul 25;4(4):475–478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.4.4.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P. F., Way W. L., Trevor A. J. Ketamine--its pharmacology and therapeutic uses. Anesthesiology. 1982 Feb;56(2):119–136. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. M., Dukes I. D. The absence of effect of chemical sympathectomy on ventricular hypertrophy induced by hypoxia in young rabbits. Cardiovasc Res. 1983 Jul;17(7):379–389. doi: 10.1093/cvr/17.7.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womble J. R., Haddox M. K., Russell D. H. Epinephrine elevation in plasma parallels canine cardiac hypertrophy. Life Sci. 1978 Nov 9;23(19):1951–1957. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]