Abstract

Background

Prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE) has been linked to child behavior problems and risky behavior during adolescence such as early substance use. Behavior problems and early substance use are associated with earlier initiation of sexual behavior. The goal of this study was to examine the direct and indirect effects of PCE on sexual initiation in a longitudinal birth cohort, about half of whom were exposed to cocaine in utero.

Methods

Women were interviewed twice prenatally, at delivery, and 1, 3, 7, 10, 15, and 21 years postpartum. Offspring (52% female, 54% African American) were assessed at delivery and at each follow-up phase with age-appropriate assessments. At age 21, 225 offspring reported on their substance use and sexual behavior.

Results

First trimester cocaine exposure was a significant predictor of earlier age of first intercourse in a survival analysis, after controlling for race, sociodemographic characteristics, caregiver pre- and postnatal substance use, parental supervision, and child’s pubertal timing. However, the association between PCE and age of first sexual intercourse was mediated by adolescent marijuana and alcohol use prior to age 15.

Conclusions

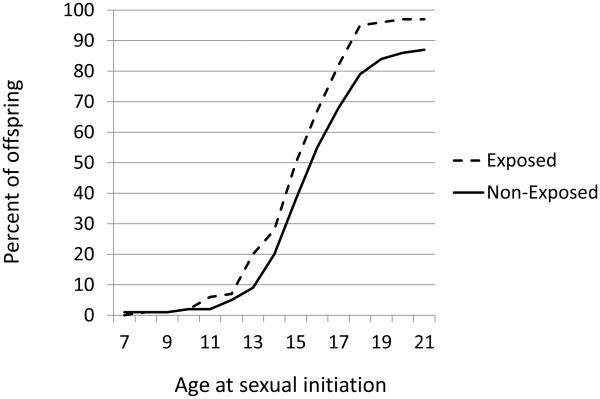

Most of the effect of PCE on age of sexual initiation occurred between the ages of 13 to 18, when rates of initiation were approximately 10% higher among exposed offspring. This effect was mediated by early adolescent substance use. These results have implications for identification of the exposed offspring at greatest risk of HIV risk behaviors and early, unplanned pregnancy.

Keywords: Prenatal Cocaine, Marijuana, Sexual Intercourse, Sexual Behavior, Adolescent Behavior

1. INTRODUCTION

In the medical literature on sexual behavior, a primary focus has been on the debut of sexual intercourse because earlier initiation of sex is a powerful predictor of HIV risk behaviors, sexually-transmitted infections (STIs), as well as early and unintended pregnancy (Bachanas et al., 2002; Melchert and Burnett, 1990; Smith, 1997). One of the strongest correlates of early sex is substance use (Madkour et al., 2010; Zimmer-Gembeck and Helfand, 2008). A review of 35 longitudinal studies confirmed that substance use is linked to earlier sexual intercourse (Zimmer-Gembeck and Helfand, 2008). In a comparative study, substance use was significantly and positively associated with early sexual behavior in each country, even though age of initiation and rates of substance use and sexual behavior varied by country (Madkour et al., 2010). And in a genetically informed design, Australian twins who experienced drunkenness earlier had sexual intercourse earlier than their co-twins who experienced drunkenness later (Deutsch et al., 2014).

In addition to substance use, there are other important correlates of early sexual intercourse. Boys report having sex earlier than girls (Nkansah-Amankra et al., 2011), and African American youth, on average, engage in intercourse earlier than White youth (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2009; De Rosa et al., 2010; Upchurch et al., 1998). Other child characteristics associated with early sexual initiation include behavior problems, earlier pubertal timing, and depressive symptoms (Epstein et al., 2013; Longmore et al., 2004; Oberlander et al., 2011; Zimmer-Gembeck and Helfand, 2008). The environment is also an important predictor of sexual behavior including exposure to child abuse and neglect (Putnam, 2003; Upchurch and Kusunoki, 2004), violence (Berenson et al., 2001), and lower levels of parental supervision (Huang et al., 2011; Zimmer-Gembeck and Helfand, 2008).

Many of these correlates of age of sexual initiation have also been documented in youth with prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE). For example, PCE is associated with increased child behavior problems (Ackerman et al., 2010; Bada et al., 2012; Bennett et al., 2013; Delaney-Black et al., 2004; McLaughlin et al., 2011; Minnes et al., 2010; Richardson et al., 2011; Whitaker et al., 2011). Children with PCE are often raised in less than optimal environments that are also linked to poor behavioral outcomes (Bradley and Corwyn, 2002; McLeod et al., 2007). Nonetheless, recent reviews evaluating studies that control for many factors in the postnatal environment have found a consistent relationship between PCE and child behavior problems (Ackerman et al., 2010; Buckingham-Howes et al., 2013).

Findings from longitudinal studies show that the effects of PCE continue into adolescence, involving new problem behaviors that emerge during this developmental period (Buckingham-Howes et al., 2013). For example, adolescents with PCE are more likely to initiate substance use at a younger age than non-exposed adolescents. Delaney-Black et al. (2011) reported that youth with PCE were more likely to initiate cocaine use by age 14 than non-exposed youth. PCE has also been associated with the early onset of alcohol and/or marijuana use (Frank et al., 2011; Minnes et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2013b), and with substance use related problems (Min et al., 2014). Further, some researchers have reported a gender by PCE interaction, with boys with PCE having poorer inhibitory control (Carmody et al., 2011), a greater propensity for risk-taking (Allen et al., 2014), more behavior problems (Bennett et al., 2007; Delaney-Black et al., 2004), earlier initiation of substance use (Bennett et al., 2007), and increased frequency of sex without a condom (Lambert et al., 2013) than girls with PCE. Thus, it is possible that gender may moderate the effect of PCE on age at sexual initiation and interaction effects should be considered in analyses.

To our knowledge, sexual behavior as a function of PCE has only been examined in one other sample. Lambert et al. (2013) assessed adolescent sexual behavior at the 15-year follow-up of the Maternal Lifestyle Study of prenatal cocaine and/or opiate exposure. At delivery, the mothers reported on their cocaine use during pregnancy. Adolescents with any PCE were slightly more likely to report sexual intercourse by age 14 than non-exposed adolescents (37% vs. 30%, respectively), but this was not statistically significant in multivariate models controlling for child gender, prenatal marijuana exposure, parental involvement, and community violence. PCE did significantly predict oral sex by age 14 in multivariate models: 31% of adolescents with PCE reported oral sex by this age compared to 22% of adolescents without PCE. Lambert et al. (2013) found no moderating effect of gender on oral sex by age 14. In another study of the same cohort, Conradt et al. (2014) found that boys, but not girls, prenatally exposed to multiple substances displayed physiological signs of neurobehavioral dysregulation that predicted sexual intercourse by age 16. It is not known if these findings are replicable in other cohorts of PCE individuals, or if they will apply to the initiation of sexual behavior after age 16.

This report is from a longitudinal, prospective study of PCE in which African American and White women were enrolled early in pregnancy and seen with their offspring at several time points across childhood, adolescence, and at 21 years post-partum. Extensive data on the mothers, offspring, and the home environment were collected at these phases. The purpose of these analyses was to examine the direct and indirect effects of PCE on the initiation of sexual behavior in offspring. We investigated whether there was a direct effect of PCE on sexual behavior, while controlling for other correlates of sexual behavior (e.g., race, gender, early puberty, lower parental monitoring). We also investigated whether the earlier effects of PCE on child behavior problems and early substance use, as summarized above, would mediate any direct effects on sexual behavior. A Gender x PCE interaction term was also entered into the direct and indirect models to determine if gender moderated the effect of PCE on age at sexual initiation.

2. METHODS

2.1 Study design

Women attending the Magee-Womens Hospital (MWH) prenatal clinic who were at least 18 years of age were approached by research staff: Written informed consent was obtained prior to interviewing the women. Ninety percent of the women approached agreed to participate. Medical chart reviews were conducted on a random sample of the women who refused to participate and only 5% had a history of drug use during the current pregnancy. The University of Pittsburgh's Institutional Review Board and the Research Review and Human Experimentation Committee of MWH approved this research. A Confidentiality Certificate (DA-04-177) obtained from the Department of Health and Human Services assured participants that their responses could not be subpoenaed.

The first interview took place during the fourth or fifth prenatal month visit when women were asked about drug use in the year prior to pregnancy and the first trimester (including cocaine/crack, alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other illicit drugs). Any woman who reported any amount of cocaine/crack use during the first trimester was enrolled. The next woman interviewed who reported no cocaine/crack use during both the year prior to pregnancy and the first trimester was also enrolled. Those selected for the study (N = 320) were subsequently interviewed during the seventh prenatal month and at ~24 hours after delivery about their substance use during the second and third trimesters, respectively. Newborns were examined by research nurses unaware of exposure status. Follow-up assessments occurred at 1, 3, 7, 10, 15, and 21 years postpartum. At all phases, mothers were interviewed about substance use over the past year, sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics, and psychiatric symptoms.

2.2 Participants

Between enrollment and delivery, 20 participants were eliminated for the following reasons: home delivery (n = 1); miscarriage, abortion, or fetal death (n = 5); moved out of the Pittsburgh area (n = 11); lost to follow-up (n = 1); or refused further participation (n = 2). Four pairs of twins and one child with Down Syndrome were excluded from follow-up, resulting in a birth cohort of 295 mother/infant pairs. At 21 years of age, 70 offspring were not included in the current analyses for the following reasons: 6 died; 2 were placed for adoption; 5 were incarcerated or in a rehabilitation facility; 18 refused to participate; 20 moved out of the area, and 19 were lost to follow- up. Thus, 225 subjects were completed at the 21-year phase, representing 76% of the birth cohort. Offspring who were (n = 225) and were not (n = 70) included in these analyses did not differ on PCE. Among those who were assessed, 41%, 7.8%, and 10.8% were exposed to cocaine during the first, second, and third trimesters of pregnancy compared to 47%, 6.5%, and 8.6% among non-assessed subjects, respectively. There were also no differences between the two groups in sociodemographic characteristics. The two groups differed on offspring gender and maternal depression assessed at delivery. Seventy-three percent of those who were not assessed at 21 years were male compared to 48% who participated in the study at 21 years (p < 0.001). The mean maternal CES-D (Radloff, 1977) depression score at birth for those who were not assessed at 21 years was 44.2 compared to 41.4 among those who were assessed (p < 0.05).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Maternal drug use

Maternal cocaine, crack, alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other illicit drug use were assessed during confidential interviewing at each of the 9 interview phases described above. Cocaine and crack use were reported in lines, rocks, or grams. Reported use of lines of cocaine or rocks of crack was converted into grams based on information from toxicology laboratories and law enforcement officials. One line was estimated to be 1/30th (0.03) of a gram; one rock was estimated to be 0.2 grams. Usual, maximum, and minimum quantity and frequency of reported cocaine/crack use were converted into average number of grams/day. For descriptive purposes, cocaine/crack use was converted back to lines/day. First trimester cocaine use was initially analyzed as: 1) a continuous variable (grams/day); 2) any use versus no use; and 3) frequent use (≥ 1 line/day) versus non-frequent use (< 1 line/day). Cocaine use was dichotomized into use/no use (PCE/no PCE) for the second and third trimesters because of the small number of women who reported use during those time periods. The alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco variables were average number of reported drinks, joints, or cigarettes per day, respectively. A drink was defined as 12 ounces of beer, 4 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of liquor. Alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use for each trimester of pregnancy and at the 15-year follow-up phase were used as continuous variables in the analyses, with one exception. At the 15-year phase, too few mothers reported use of marijuana and cocaine for them to be analyzed as separate variables: Other illicit drug use at 15 years was defined as any reported use of marijuana, cocaine, or other illicit drugs. Further information about the maternal drug measures can be found in Day and Robles (1989) and Richardson et al. (2008).

2.3.2 Offspring sexual behavior

At the 21-year follow-up visit, offspring reported on sexual behavior using items from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS; Morris et al., 1993). Questions included “Have you ever had oral sex?”, “How old were you the first time you had oral sex?”, “Have you ever had sexual intercourse?”, and “How old were you the first time you had sexual intercourse?” The interviewer handed this portion of the interview to the respondent so that they could answer these items privately. The YRBSS has excellent test-retest reliability, with a Kappa of 90.5% for the “ever had sexual intercourse” item. Reliability does not differ as a function of child gender or race/ethnicity (Brener et al., 1995; 2002). The two “age of onset” questions were used as continuous variables in the Cox regression models. The two “have you ever” questions were not analyzed because over 90% of the sample responded yes to these questions.

2.3.3 Offspring substance use

At age 15, adolescents were asked about their lifetime use, use in the past year, and age of initiation of substances, including alcohol (beer, wine, liquor), marijuana, and tobacco, using questions from the Health Behavior Questionnaire (Jessor et al., 1989). Age of initiation as reported at the 15-year phase was used in the analyses unless initiation had not yet occurred. In that case, age of initiation as reported at the 21-year phase was used in the analyses. Early use of alcohol and marijuana was defined as any use prior to age 15.

2.3.4 Other offspring measures

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) was administered to mothers at the age 7 follow-up. The total, internalizing, and externalizing scales were used. At age 10, offspring completed the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992), a measure of depressive symptoms adapted from the Beck Depression Inventory. Good internal consistency and validity have been reported (Kovacs, 1992; Sitarenios and Stein, 2004). The CDI measures general psychopathology over the last two weeks, rather than clinically defined depression, and assesses symptoms such as negative mood and self-esteem, and anhedonia. The total raw score was used.

At age 15, the adolescents completed the “My Parents” questionnaire (Steinberg et al., 1992). For these analyses, the supervision subscale of the measure was used, which assesses the adolescent’s view of parental monitoring and limit setting. In addition, they completed the Pubertal Developmental Scale (Petersen et al., 1988), a self-report of their pubertal status. The item used for analysis asked them to compare their pubertal timing to same-age and same-sex peers (1 = much earlier to 5 = much later). This measure has been used in other longitudinal studies investigating the effects of pubertal development (Campa and Eckenrode, 2006; Carter et al., 2009). The Screen for Adolescent Violence Exposure (SAVE; Hastings and Kelly, 1997) was used at age 15 to assess direct exposure to personal violence such as being shot, beaten, or hurt by a knife, and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein and Fink, 1998) was used to measure physical and emotional abuse and neglect and sexual abuse. This was scored as the cumulative total of all subscales for which the score was above the cut- point for "moderate to severe abuse".

2.4 Statistical analyses

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was applied to: 1) test the bivariate relation between PCE and age of first intercourse and age of first oral sex; 2) test the relation between PCE and age of first intercourse and oral sex, while accounting for other significant predictors; and 3) examine the indirect effects of PCE on sexual behavior via potential mediators. The hazard function indicates the probability of initiating at a certain point, given that one has not initiated yet. A hazard ratio greater than one for PCE individuals compared to non-exposed individuals indicates events occurring at a faster rate for PCE individuals. The Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed in a stepwise manner to avoid model saturation.

The following variables were considered as covariates. One, we considered covariates from the first trimester to control for baseline characteristics associated with PCE (maternal education, marital status, first trimester alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use). Two, we examined potential covariates from the 15-year phase to control for offspring characteristics (gender, race, parental supervision, pubertal timing, exposure to violence, child abuse/neglect) and environmental factors (caregiver's education, family income, man in household, and caregiver alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use) prior to or at the onset of sexual activity. Covariates that were significant at an alpha level of 0.10 were included in the model to test the stability of the relation between PCE and the outcome variables.

Mediators were selected based on our previous findings and on their association to the outcome variables as reported in the literature. These included CBCL externalizing behavior at age 7 (Richardson et al., 2011), 10-year depressive symptoms (Richardson et al., 2013a), and onset of marijuana and alcohol use by age 15 (Richardson et al., 2013b). These variables have also been reported to be associated with earlier sexual activity (Epstein et al., 2013; Zimmer-Gembeck and Helfand, 2008). Therefore, we tested the associations of these variables with the sexual outcome variables. Each mediator was tested separately and, if they were found to be significant at alpha level of 0.05, they were included as potential mediators in a combined model.

In the final step of each model, a Gender x PCE interaction term was entered into the model to determine if gender moderated the effect of PCE on age at sexual initiation because of prior work indicating that boys with PCE may be at greater risk (Bennett et al., 2007; Carmody et al., 2011; Delaney-Black et al., 2004; Lambert et al., 2013).

3. RESULTS

Maternal prenatal cocaine use was moderate, with most users decreasing or discontinuing use after the first trimester. This represents the most common pattern of drug use in non-treatment samples (Cornelius et al., 2002; Day et al., 1989, 1991; SAMHSA, 1998). In the first trimester of pregnancy, 41% of the women reported using cocaine. This proportion decreased over pregnancy: 8% and 11% of the women reported use of cocaine during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, respectively. Among cocaine users, 18.2%, 4.4%, and 6.3% used ≥ 1 line/day during the first, second, and third trimesters, respectively. During the first trimester, 50% reported snorting powder cocaine only; the rest smoked crack. During the third trimester, 20% reported snorting powder cocaine only; the rest smoked crack. All of the women who used cocaine later in their pregnancy also reported use during their first trimester.

The median age of the offspring at the 21-year assessment was 21.2 years (range = 20 – 24). Forty-eight percent of the offspring were males, 46% were White, and 54% were African American. The mean level of offspring education was 12.7 years (range = 8 – 16): 42% were attending school, 58% were working, and 3% served in the military. Median personal income was $500/month (range= 0-8000) and 14% reported receiving public assistance. Three percent of the offspring were married at the 21-year phase and 25% had at least one child. Forty-one percent, 36%, and 28% of the offspring reported using tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana prior to age 15, respectively.

Women who used cocaine during the first trimester were more likely to be African-American, older, had lower family incomes, and were more likely to be single than were non-users during the first trimester (Table 1). First trimester cocaine users used more tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs during the first trimester than did the first trimester non-cocaine users. At the 21-year phase, caregiver income was lower and current use of alcohol and illicit drugs was greater in first trimester cocaine users compared to non-users (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics as a function of first trimester cocaine exposure

| No cocaine use 1st trimester |

Cocaine use 1st

trimester |

p valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 133 | N = 92 | ||

| First trimester maternal characteristics | |||

| African American (%) | 42.1 | 55.4 | <.05 |

| Age (yrs) (mean, SD) | 24.1 (5.0) | 26.5 (5.0) | < .001 |

| Education (yrs) (mean, SD) |

12.1 (1.4) | 11.9 (1.2) | ns |

| Family income ($/mo) (mean, SD) |

782 (614) | 568 (683) | < .05 |

| Single (%) | 70 | 89 | < .001 |

| Cigarettes/day (mean, SD) |

5.7 (8.9) | 10.7 (9.0) | <.001 |

| Drinks/day (mean, SD) |

0.3 (0.6) | 2.3 (3.0) | <.001 |

| Joints/day (mean, SD) | 0.06 (0.2) | 0.5 (1.3) | <.001 |

| Other illicit drugs (except cocaine) (%) |

2.3 | 9.8 | <.05 |

| 21-year caregiver characteristics | |||

| Education (yrs) (mean, SD) |

13.0 (1.7) | 13.2 (1.9) | ns |

| Family income ($/mo) (mean, SD) |

2927 (2155) | 2138 (2176) | < .05 |

| Single (%) | 59 | 70 | ns |

| Cigarettes/day (mean, SD) |

5.5 (9.1) | 6.4 (7.4) | ns |

| Drinks/day (mean, SD) |

0.7 (2.4) | 1.8 (3.5) | < .05 |

| Illicit drugs (cocaine, marijuana) (%) |

10.2 | 24.4 | < .01 |

| 21-year offspring characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) (mean, SD) | 21.3 (0.7) | 21.3 (0.6) | ns |

| Male (%) | 48.1 | 46.7 | ns |

| African American (%) | 47.4 | 63.0 | < .05 |

| Education (yrs) (mean, SD) |

12.8 (1.5) | 12.6 (1.4) | ns |

| Working (% yes) | 56.4 | 59.8 | ns |

| Attend school (% yes) | 40.6 | 43.5 | ns |

| Personal income ($/mo) (mean, SD) |

661 (739) | 914 (1213) | ns |

| Receive public assistance (% yes) |

15.8 | 12.0 | ns |

| Live with partner (%) | 19.6 | 19.6 | ns |

| ≥ 1 child (%) | 22.6 | 28.3 | ns |

Based on t-test or Mann-Whitney for continuous variables and on Chi-square test for dichotomous variables.

At 21 years, there were no significant differences in offspring demographic characteristics between first trimester users and non-users, except for race (Table 1). There were no statistically significant gender differences in 21-year sexual activity. The rates of ever having intercourse among females and males were 95% and 89%, respectively (χ2= 2.8, p = 0.1) and the rates of ever having oral sex among females and males were 86% and 87%, respectively (χ2= 0.02, p = 0.9). Gender was also not significantly related to age of intercourse initiation (χ2=0.02, p = 0.9) or to age of initiation of oral sex (χ2=1.6, p = 0.2) in this sample. There were no significant Gender x PCE effects on age at first oral sex or intercourse. The average ages of intercourse and oral sex initiation among boys were 15.4 and 15.8 years, respectively. The average ages of intercourse and oral sex initiation among girls were 15.8 and 16.3 years, respectively.

The continuous and frequent use first trimester cocaine variables did not predict either sexual behavior outcome so only the use/no use results are reported here. Figure 1 depicts the cumulative onset of sexual intercourse for first trimester cocaine exposed and non-exposed offspring. By age 13, intercourse initiation was approximately 10% higher among exposed offspring than the non-exposed offspring (19.6% versus 9.0%, χ2 = 5.2, p < 0.05). This rate of difference between the two groups remained more or less constant and reached its peak at age 18, when 94.6% of the exposed offspring had initiated sexual relations compared to 78.9% of the non-exposed offspring (χ2 = 10.6, p < 0.01). There was no statistically significant association between PCE and age of initiation of oral sex. There were no significant associations between second and third trimester PCE and sexual activity.

Figure 1.

Cumulative onset of sexual initiation as a function of prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE).

Survival analysis was conducted on age of first intercourse and age at first oral sex. PCE remained a significant predictor of age of first intercourse in the survival analysis after controlling for significant covariates (Table 2). The risk of initiating intercourse among adolescents with PCE was 1.5 times greater compared to non- exposed offspring (hazard ratio=1.5, p < 0.01). Parental supervision was also a predictor of age of first intercourse: Offspring who reported greater parental supervision were older when they initiated sexual intercourse. PCE was not significantly associated with age of initiation of oral sex. Offspring race (White) was a predictor of earlier initiation of oral sex (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of Cox Proportional Hazards Model

| Coefficient | Hazard ratio | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of initiation of intercourse | |||

| a) model including PCEa only | |||

| First trimester exposure | 0.38 | 1.5 | < .01 |

| b) adding significant covariatesb | |||

| First trimester PCE | 0.37 | 1.5 | < .01 |

| Parental supervision | −0.04 | 0.96 | < .06 |

| c) adding potential mediators | |||

| First trimester PCE | 0.21 | 1.2 | ns |

| Parental supervision | −0.02 | 0.98 | ns |

| Offspring marijuana use by age 14 | 0.55 | 1.73 | < .01 |

| Offspring alcohol use by age 14 | 0.61 | 1.85 | < .001 |

| Age of initiation of oral sex | |||

| a) model including PCE only | |||

| First trimester exposure | 0.06 | 1.06 | ns |

| b) adding significant covariatesb | |||

| First trimester exposure | 0.14 | 1.15 | ns |

| Racec | 0.37 | 1.45 | < .05 |

| c) adding potential mediators | |||

| First trimester exposure | −0.07 | 0.9 | ns |

| Racec | 0.32 | 1.37 | < .05 |

| Offspring marijuana use by age 14 | 0.36 | 1.43 | < .05 |

| Offspring alcohol use by age 14 | 0.82 | 2.3 | < .001 |

PCE = prenatal cocaine exposure

Covariates that were included in the models are detailed in the statistical analysis section.

Whites had earlier onset

We subsequently evaluated potential mediators of the effects of PCE on sexual behavior, including child behavior problems, depressive symptoms, and alcohol and marijuana use prior to age 15. Child behavior problems and depressive symptoms were not related to sexual activity and hence were not mediators. However, early child substance use was related to sexual behavior and the association between first trimester cocaine exposure and age of initiation of sexual intercourse was mediated by adolescent marijuana and alcohol use prior to age 15. There was no significant relation between PCE and adolescent tobacco initiation so adolescent tobacco use could not serve as a mediator. The hazard ratio of PCE for sexual initiation was reduced from 1.5 to 1.2 with marijuana and alcohol use in the model; the effect of PCE was no longer statistically significant (Table 2).

In order to ensure that marijuana use before age 15 was a true mediator, i.e., that it occurred prior to the onset of sexual intercourse, we re-ran the above analyses excluding 4 subjects who had initiated sexual intercourse prior to initiating marijuana use. The results shown in Table 2 were unchanged. In addition, we also investigated whether those who initiated sexual intercourse very early (prior to age 12) had been sexually abused. We re-ran the analyses eliminating 3 subjects who met this criterion and the results in Table 2 were unchanged.

4. DISCUSSION

This study provided initial evidence for a direct effect of first trimester cocaine exposure on age at first intercourse, controlling for other prenatal drug exposure, race, gender, earlier pubertal timing, lower levels of parental supervision, exposure to child abuse/neglect, and greater exposure to violence. We were able to determine via survival analysis that most of the effect of PCE on age of sexual initiation occurred between the ages of 13 to 18, when rates of initiation were approximately 10% higher among exposed offspring than the non-exposed offspring. However, this direct relationship was mediated by early adolescent marijuana and alcohol use. Adolescents with PCE who began using marijuana prior to age 15 were significantly more likely to initiate sexual intercourse at a younger age than non-cocaine-exposed and non- marijuana-using adolescents. There were no gender differences in timing of intercourse, and gender did not moderate the direct or indirect effect of PCE on age of sexual initiation. Child behavior problems and depressive symptoms were not predictors of sexual behavior, and therefore did not mediate the effect of PCE on age of sexual debut. It is possible that our findings differ from previous studies because they did not examine the pathways linking PCE, child behavior problems, early depressive symptoms, adolescent substance use, and sexual initiation.

Although there is a well-known association between child’s substance use and timing of first sexual intercourse, no studies to date have examined the direct and indirect effects of PCE on the full range of age at initiation of sexual behavior. Children with PCE are vulnerable to early sexual intercourse and associated reproductive health outcomes (such as STIs/HIV and unintended pregnancy) because of the strong association of PCE with early substance use (Delaney-Black et al., 2011; Frank et al., 2011; Minnes et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2013b) and other risk factors (Ackerman et al., 2010; Buckingham-Howes et al., 2013; Richardson et al., 2011). Thus, exposed individuals may enter the period of adolescence “primed” for earlier substance use and sexual intercourse, and are more likely to engage in these behaviors at a less optimal time than unexposed individuals. Overall, the offspring in this sample reported a lower age of initiation of sexual intercourse (15 years old) than is reported in the general population, consistent with other markers of disadvantage in this sample. For example, only 32% of girls and 35% of boys in the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) had sex by age 16 (Finer and Philbin, 2013). In our study, youth with PCE were at even greater risk: nearly 20% had sex by age 13 and 95% had sex by age 18. In contrast, only 74% of boys and girls in the NSFG had sex by age 20 (Finer and Philbin, 2013). Therefore, youth with PCE are at greater than average risk of HIV risk behaviors, STIs, and early pregnancies.

In the only other study to date examining the effect of PCE on sexual behavior, Lambert et al. (2013) found a modest unadjusted association between PCE and sexual intercourse by age 14 that was not significant in the multivariate model. PCE did not predict early substance use in their sample. In contrast to Lambert et al.’s findings, the substance use and sexual initiation data from the current study cover the entire adolescent period. Our results indicate that individuals with PCE initiate sexual intercourse significantly earlier than unexposed individuals. This relationship was mediated by early marijuana and alcohol use and once early substance use was introduced into the model, no other covariates remained significant. These findings suggest that interventions to prevent and/or delay substance use in these youths may also delay initiation of sexual intercourse, a well-known risk factor for HIV risk behaviors and unintended adolescent pregnancy (Bachanas et al., 2002; Melchert and Burnett, 1990; Smith, 1997). These results provide converging evidence that substance use prevention efforts may help decrease HIV risk behaviors in vulnerable youth.

The mothers in this study represent a general population of pregnant women who predominantly used cocaine early in pregnancy, rather than women who were heavy users throughout pregnancy. Prenatal cocaine use was moderate and representative of PCE in non-treatment samples (SAMHSA, 1998). African American and White women were approximately equally represented in this study, which had an excellent follow-up rate through 21 years postpartum. Other strengths included the detailed assessment of prenatal drug exposure and the breadth of measures used in multiple postnatal assessments, permitting control of many variables in the prenatal and postnatal environment and of well-known risk factors for early initiation of sex. Nonetheless, it is possible that unmeasured variables may have contributed to both early substance use and sex in exposed individuals. For example, there is evidence for structural differences in the brain regions of adolescents with PCE. These brain regions are associated with difficulties in response inhibition (Lebel et al., 2013) and risk for substance use (Rando et al., 2013).

A potential limitation of the study is that we did not conduct biological assessments of prenatal substance use, leading to the possibility that women who denied use would be misclassified. This would, however, attenuate differences between groups and would not affect the significant findings. Further, we have previously shown that our self-report substance use measures, with careful interviewer selection and training and attention to question format, identified a higher percentage of users than did urine screening (Richardson et al., 1999, 2006). Other researchers have shown this as well (Ashling et al., 1994; Fendrich et al., 2004; Lester et al., 2001; Rutherford et al., 2000; Zuckerman et al., 1989). We did collect biological samples from the 21-year offspring and those data also support this point: 95% of those offspring with positive urine screens for marijuana reported current use. The remaining 5% with positive urine screens reported that they had previously used marijuana. However, 40% of the offspring who reported marijuana use had negative urine screens, and thus would not have been detected if we had used only biological measures of marijuana use. This study also utilized offspring self-report of sexual behavior. A recent analysis of data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health found that young adults are reliable and consistent reporters of age at first sex (Goldberg et al., 2014).

In conclusion, these findings provide a more complete picture of risk for offspring with PCE, who engage in “adult” behaviors such as substance use and sexual intercourse much earlier than their non-exposed peers during early adolescence. PCE was indirectly associated with timing of first sexual intercourse via earlier marijuana use. These results have implications for identification of the exposed offspring at greatest risk of HIV risk behaviors between the ages of 13 and 18. Future research should focus on both the etiology and reproductive health outcomes of early sex in exposed individuals. For example, the pathways between PCE and structural differences in the brains of exposed children and between structural differences and timing of initiation of substance use and sex should be investigated. Early, unintended pregnancies and history of STIs in exposed and unexposed offspring should also be assessed because of the well-known association between earlier initiation of sex and these reproductive health problems. This is the first study to highlight the importance of both PCE and early marijuana use for early initiation of sexual intercourse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCE

- Achenbach T. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman JP, Riggins T, Black MM. A review of the effects of prenatal cocaine exposure among school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:554–565. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JW, Bennett DS, Carmody DP, Wang Y, Lewis M. Adolescent risk-taking as a function of prenatal cocaine exposure and biological sex. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2014;41:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashling K, Gross AH, Coghlin DT, Sweeney PJ. Prevalence of positive urine drug screens in a prenatal clinic: correlation with patients' self-report of drug use. R. I. Med. 1994;77:371–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachanas PJ, Morris MK, Lewis-Gess JK, Sarett-Cuasay EJ, Flores AL, Sirl KS, Sawyer MK. Psychological adjustment, substance use, HIV knowledge, and risky sexual behavior in at-risk minority females: developmental differences during adolescence. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2002;27:373–384. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bada HS, Bann CM, Whitaker TM, Bauer CR, Shankaran S, LaGasse L, Lester BM, Hammond J, Higgins R. Protective factors can mitigate behavior problems after prenatal cocaine and other drug exposures. Pediatrics. 2012;130:1479–1488. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D, Bendersky M, Lewis M. Preadolescent health risk behavior as a function of prenatal cocaine exposure and gender. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2007;28:467–472. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31811320d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D, Marini V, Berzenski S, Carmody D, Lewis M. Externalizing problems in late childhood as a function of prenatal cocaine exposure and environmental risk. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013;38:296–308. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenson AB, Wiemann CM, McCombs S. Exposure to violence and associated health-risk behaviors among adolescent girls. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2001;155:1238–1242. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.11.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A Retrospective Self-Report. Harcourt Brace and Company; San Antonio, TX: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Collins JL, Kann L, Warren CW, Williams BI. Reliability of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1995;141:575–580. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann JL, McManus T, Kinchen SA, Sundberg EC, Ross JG. Reliability of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. J. Adolesc. Health. 2002;31:336–342. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham-Howes S, Berger SS, Scaletti LA, Black MM. Systematic review of prenatal cocaine exposure and adolescent development. Pediatrics. 2013;131:1917–1936. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campa MI, Eckenrode JJ. Pathways to intergenerational adolescent childbearing in a high-risk sample. J. Marriage Fam. 2006;68:558–572. [Google Scholar]

- Carmody DP, Bennett DS, Lewis M. The effects of prenatal cocaine exposure and gender on inhibitory control and attention. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2011;33:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R, Jaccard J, Silverman WK, Pina AA. Pubertal timing and its link to behavioral and emotional problems among 'at-risk' African American adolescent girls. J. Adolesc. 2009;32:467–481. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Schootman M, Bucholz KK, Peipert JF, Sanders-Thompson V, Cottler LB, Bierut LJ. Age of sexual debut among US adolescents. Contraception. 2009;80:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt E, LaGasse LL, Shankaran S, Bada H, Bauer CR, Whitaker TM, Hammond JA, Lester BM. Physiological correlates of neurobehavioral disinhibition that relate to drug use and risky sexual behavior in adolescents with prenatal substance exposure. Dev. Neurosci. 2014;36:306–315. doi: 10.1159/000365004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Larkby C. Alcohol, tobacco and marijuana use among pregnant teenagers: 6-year follow-up of offspring growth effects. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2002;24:703–710. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day NL, Jasperse D, Richardson G, Robles N, Sambamoorthi U, Taylor P, Scher M, Stoffer D, Cornelius M. Prenatal exposure to alcohol: effect on infant growth and morphologic characteristics. Pediatrics. 1989;84:536–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day N, Robles N. Methodological issues in the measurement of substance use. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1989;562:8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb21002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day N, Sambamoorthi U, Taylor P, Richardson G, Robles N, Jhon Y, Scher M, Stoffer D, Cornelius M, Jasperse D. Prenatal marijuana use and neonatal outcome. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 1991;13:329–334. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(91)90079-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney-Black V, Chiodo LM, Hannigan JH, Greenwald M, Janisse J, Patterson G, Huestis MA, Ager J, Sokol RJ. Prenatal and postnatal cocaine exposure predict teen cocaine use. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2011;33:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney-Black V, Covington C, Nordstrom B, Ager J, Janisse J, Hannigan JH, Chiodo L, Sokol RJ. Prenatal cocaine: quantity of exposure and gender moderation. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2004;25:254–263. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200408000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa CJ, Ethier KA, Kim DH, Cumberland WG, Afifi AA, Kotlerman J, Loya RV, Kerndt PR. Sexual Intercourse and oral sex among public middle school students: prevalence and correlates. Perspect. Sex. Repro. H. 2010;42:197–205. doi: 10.1363/4219710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch AR, Slutske WS, Heath AC, Madden PA, Martin NG. Substance use and sexual intercourse onsets in adolescence: a genetically informative discordant twin design. J. Adolesc. Health. 2014;54:114–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Bailey JA, Manhart LE, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF. Understanding the link between early sexual initiation and later sexually transmitted infection: test and replication in two longitudinal studies. J. Adolesc. Health. 2013;54:435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich M, Johnson TP, Wislar JS, Hubbell A, Spiehler V. The utility of drug testing in epidemiological research: results from a general population survey. Addiction. 2004;99:197–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB, Philbin JM. Sexual initiation, contraceptive use, and pregnancy among young adolescents. Pediatrics. 2013;131:1–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DA, Rose-Jacobs R, Crooks D, Cabral HJ, Gerteis J, Hacker KA, Martin B, Weinstein ZB, Heeren T. Adolescent initiation of licit and illicit substance use: impact of intrauterine exposures and post-natal exposure to violence. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2011;33:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SK, Haydon AA, Herring AH, Halpern CT. Longitudinal consistency in self-reported age of first vaginal intercourse among young adults. J. Sex Res. 2014;51:97–106. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.719169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings T, Kelly M. Development and validation of the Screen for Adolescent Violence Exposure (SAVE) J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1997;25:511–520. doi: 10.1023/a:1022641916705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DY, Murphy DA, Hser YI. Parental monitoring during early adolescence deters adolescent sexual initiation: discrete-Time survival mixture analysis. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2011;20:511–520. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9418-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Donovan J, Costa F. Health Behavior Questionnaire. University of Colorado; Boulder, CO: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory. Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; N. Tonawanda, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert BL, Bann CM, Bauer CR, Shankaran S, Bada HS, Lester BM, Whitaker TM, LaGasse LL, Hammond J, Higgins RD. Risk-taking behavior among adolescents with prenatal drug exposure and extrauterine environmental adversity. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2013;34:669–679. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000437726.16588.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, Warner T, Colby J, Soderberg L, Roussotte F, Behnke M, Eyler FD, Sowell ER. White matter microstructure abnormalities and executive function in adolescents with prenatal cocaine exposure. Psychiatry Res. 2013;213:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester B, ElSohly M, Wright L, Smeriglio V, Verter J, Bauer C, Shankaran S, Bada H, Walls H, Huestis M, Finnegan L, Maza P. The Maternal Lifestyle Study: drug use by meconium toxicology and maternal self-report. Pediatrics. 2001;107:309–317. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore MA, Manning WD, Giordano PC, Rudolph JL. Self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and adolescents’ sexual onset. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2004;67:279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Madkour AS, Farhat T, Halpern CT, Godeau E, Gabhainn SN. Early adolescent sexual initiation as a problem behavior: a comparative study of five nations. J. Adolesc. Health. 2010;47:389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin AA, Minnes S, Singer LT, Min M, Short EJ, Scott TL, Satayathum S. Caregiver and self-report of mental health symptoms in 9-year old children with prenatal cocaine exposure. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2011;33:582–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR, Wood JJ. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007;27:986–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchert T, Burnett KF. Attitudes, knowledge, and sexual behavior of high-risk adolescents: implications for counseling and sexuality education. J. Counseling Dev. 1990;68:293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Min MO, Minnes S, Lang A, Weishampel P, Short EJ, Yoon S, Singer LT. Externalizing behavior and substance use related problems at 15 years in prenatally cocaine exposed adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2014;37:269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnes S, Singer LT, Kirchner HL, Short E, Lewis B, Satayathum S, Queh D. The effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on problem behavior in children 4-10 years. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2010;32:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnes S, Singer LT, Min MO, Wu M, Lang A, Yoon S. Effects of prenatal cocaine/polydrug exposure on substance use by age 15. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris L, Warren C, Aral S. Measuring adolescent sexual behaviors and related health outcomes. Public Health Rep. 1993;108:31–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkansah-Amankra S, Diedhiou A, Agbanu HL, Harrod C, Dhawan A. Correlates of sexual risk behaviors among high school students in Colorado: analysis and implications for school-based HIV/AIDS programs. Matern. Child Health J. 2011;15:730–741. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander SE, Wang Y, Thompson R, Lewis T, Proctor LJ, Isbell P, English DJ, Dubowitz H, Litrownik AJ, Black MM. Childhood maltreatment, emotional distress, and early adolescent sexual intercourse: multi-informant perspectives on parental monitoring. J. Fam. Psychol. 2011;25:885–894. doi: 10.1037/a0025423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report of pubertal status: reliability, validity, and initial norms. J. Youth Adolesc. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam FW. Ten-year research update review: child sexual abuse. J. Am. Acad. Child Psychol. 2003;42:269–278. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psych. Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rando K, Chaplin TM, Potenza MN, Mayes L, Sinha R. Prenatal cocaine exposure and gray matter volume in adolescent boys and girls: relationship to substance use initiation. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;74:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Larkby C, Day NL. Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on child behavior and growth at 10 years of age. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2013a;40:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Leech S, Willford J. Prenatal cocaine exposure: effects on mother- and teacher-rated behavior problems and growth in school-age children. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2011;33:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Willford J. The effects of prenatal cocaine use on infant development. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2008;30:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Hamel S, Goldschmidt L, Day N. Growth of infants prenatally exposed to cocaine/crack: a comparison of a prenatal care and a no prenatal care sample. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e18. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.2.e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Huestis M, Day N. Assessing in utero exposure to cannabis and cocaine. In: Bellinger DC, editor. Human Developmental Neurotoxicology. Taylor & Francis Group; New York: 2006. pp. 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Larkby C, Goldschmidt L, Day NL. Adolescent initiation of drug use: effects of prenatal cocaine exposure. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2013b;52:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford MJ, Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McKay JR, Cook TG. Contrasts between admitters and deniers of drug use. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2000;18:343–348. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitarenios G, Stein S. Use of the Children’s Depression Inventory. In: Maruish ME, editor. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. 3rd L. Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; Mahwah, NJ: 2004. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA. Factors associated with early sexual activity among urban adolescents. Soc. Work. 1997;42:334–346. doi: 10.1093/sw/42.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn S, Dornbusch S, Darling N. Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: authoritative parenting, school-involvement, and encouragement to success. Child Dev. 1992;63:1266–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Preliminary Results from the 1997 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. SAMHSA; Rockville, MD: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Kusunoki Y. Associations between forced sex, sexual and protective practices, and sexually transmitted diseases among a national sample of adolescent girls. Womens Health Issues. 2004;14:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Levy-Storms L, Sucoff CA, Aneshensel CS. Gender and ethnic differences in the timing of first sexual intercourse. Fam. Plann. Perspect. 1998;30:121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker T, Bada H, Bann C, Shankaran S, LaGasse L, Lester B, Bauer CR, Hammond J, Higgins R. Serial pediatric symptom checklist screening in children with prenatal drug exposure. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2011;32:206–215. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318208ee3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Helfand M. Ten years of longitudinal research on U.S. adolescent sexual behavior: developmental correlates of sexual intercourse, and the importance of age, gender and ethnic background. Dev. Rev. 2008;28:153–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman B, Frank D, Hingson R, Amaro H, Levenson S, Kayne H, Parker S, Vinci R, Aboagye K, Fried L, Cabral H, Timperi R, Bauchner H. Effects of maternal marijuana and cocaine use on fetal growth. N. Engl. J. Med. 320:762–768. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903233201203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]