Abstract

Inorganic nanoparticles have been introduced into biological systems as useful probes for in vitro diagnosis and in vivo imaging, due to their relatively small size and exceptional physical and chemical properties. A new kind of color tunable Gd-Zn-Cu-In-S/ZnS (GZCIS/ZnS) quantum dots (QDs) with stable crystal structure was successfully synthesized and utilized for magnetic resonance (MR) and fluorescence dual modality imaging. This strategy allows successful fabrication of GZCIS/ZnS QDs by incorporating Gd into ZCIS/ZnS QDs to achieve great MR enhancement without compromising the fluorescence properties of the initial ZCIS/ZnS QDs. The as-prepared GZCIS/ZnS QDs show high T1 MR contrast as well as “color-tunable” photoluminescence (PL) in the range of 550–725 nm by adjusting the Zn/Cu feeding ratio with high PL quantum yield (QY). The GZCIS/ZnS QDs were transferred into water via a bovine serum albumin (BSA) coating strategy. The resulting Cd-free GZCIS/ZnS QDs reveal negligible cytotoxicity on both HeLa and A549 cells. Both fluorescence and MR imaging studies were successfully performed in vitro and in vivo. The results demonstrated that GZCIS/ZnS QDs could be a dual-modal contrast agent to simultaneously produce strong MR contrast enhancement as well as fluorescence emission for in vivo imaging.

Keywords: CuInS2 quantum dot, magnetic resonance imaging, photoluminescence, multimodality imaging, gadolinium doped

1. Introduction

Recently, the marriage of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and optical imaging techniques has gained intense attention due to the complementary imaging ability of these two modalities [1]. MRI offers anatomical details and high quality 3-D information of soft tissue in a non-invasive manner [2–6], while optical imaging, especially fluorescence imaging, has relatively good sensitivity but with low tissue penetration depths [3, 5, 7, 8]. Thus, the MRI/fluorescence dual-imaging agents should have exciting clinical potential as, for example, they can be used in surgery to guide the scalpel (via fluorescence imaging), to ensure that all cancerous tissue has been removed (via MR imaging) [9, 10]. Especially for cases in which near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence dyes are used, enhanced tissue penetration along with MR imaging makes precise in vivo tumor detection possible [11].

Compared with fluorescent dyes, semiconducting quantum dots (QDs) appear to be more attractive candidates for building MRI/fluorescence dual-modal contrast agents, as QDs have the unique optical properties such as size-dependent emission, high brightness, narrow emission and broad absorption spectra, and high resistance to photo bleaching [12, 13]. However, the toxicity of conventional cadmium-based QDs (including CdSe and CdTe) limits their potential for clinical translation. Fortunately, I-III-VI QDs, such as CuInS2-based QDs, have been developed as promising contrast agents for in vivo NIR fluorescence imaging, due to the advantages of non-toxicity and photoluminescence (PL) emission in the NIR region [14–17]. In previous works, CuInS2 QDs have been shown to have much reduced toxicity compared with CdTeSe/CdZnS QDs and have been successfully used for tumor targeted imaging as NIR fluorescence probes [15, 17–21]. Additionally, Zn-Cu-In-S (ZCIS) and ZCIS/ZnS quaternary QDs, a derivative formulation of CuInS2 QDs, seems to exhibit better fluorescence and color tunability than the original ternary CuInS2 QDs [22, 23].

Recently paramagnetic ions (Mn2+ and Gd3+) doped QDs [24–29] have been developed as dual-modal imaging probes. For example, Ai and Lu successfully developed ultrasmall Gd-doped ZnO QDs [26]. Wang et al. demonstrated a series of core/shell CdSe/Zn1-xMnxS nanoparticles with varied shell thickness and the Mn2+ content [30]. These doped QDs as dual-modal imaging probes with robust stable crystal structure, are considered to be essential players in the next-generation biomedical techniques, which not only enhance imaging sensitivity and resolution but also possess specificity for so-called “molecular imaging” capabilities [9, 26]. However, these doped QDs do not present NIR emission and suffer from decreased PL QY when paramagnetic ions are introduced. Consequently, it still remains a challenge to fabricate dual-modal doped QDs without compromising the properties of each component in isolation used for NIR fluorescence imaging and MRI.

Here we report a facile strategy to synthesize Gd-doped Zn-Cu-In-S/ZnS (GZCIS/ZnS) QDs using gadolinium oleate, zinc oleate, copper oleate and indium oleate and S as precursors, as shown in scheme 1. The distinguishing features of this strategy include: (1) the luminescence of GZCIS/ZnS QDs can be preciously tuned in the range of 550–725 nm by only adjusting the parameter of Zn/Cu feeding ratio; (2) the fluorescence QYs can be as high as 40%, close to that of Gd-free ZCIS/ZnS QDs; (3) the doped QDs show higher R1relaxivity (11.5–15.8 mM−1S−1) than Gd-DTPA (3.7 mM−1S−1); and (4) the GZCIS/ZnS QDs allows simultaneous NIR fluorescence imaging and MRI in vivo. Thus, this strategy allows successful fabrication of GZCIS/ZnS QDs by incorporating Gd into ZCIS/ZnS QDs to achieve great MR enhancement without sighificantly compromising the fluorescence properties of the initial ZCIS/ZnS QDs. The prepared GZCIS/ZnS QDs are verified to be a qualified dual-modal contrast agent to simultaneously produce strong MR contrast enhancement as well as fluorescence emission for in vivo imaging.

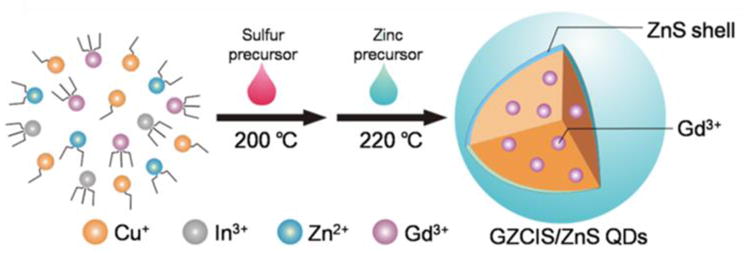

Scheme 1.

Illustration of the synthesis of GZCIS/ZnS QDs used for MR and fluorescence imaging.

2. Experiments

2.1 Materials

Copper(II) chloridedihydrate (CuCl2·2H2O, ACS, 99+%), Indium(III) chloride hydrate (InCl3, 99.99%), Zinc chloride (ZnCl2, ACS, 97%), Zinc acetate dehydrate (Zn(Ac)2·2H2O, ACS, 98%) and Gadolinium (III) chloride hexahydrate (GdCl3·6H2O, reacton®, 99.9%) were all purchased from Alfa Aesar China Co. Ltd. 1-Octadecene (ODE, 90%), oleic acid (OA, 90%), bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 1-dodecanethiol (DDT, 98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium oleate (C18H33NaO2) was purchased from Aladdin Reagent Company. All the chemicals were used without further purification. Deionized water (18.2 MΩ•cm resistivity at 25 °C) was used for all tests.

2.2 Synthesis of metal-oleate complexes

The metal-oleate complexes were prepared according to a similar procedure for the synthesis of the iron–oleate complex reported previously [31, 32]. In a typical process, GdCl3·6H2O (5 mmol) and sodium oleate (15 mmol) were dissolved in mixed solvents composed of ethanol (20 mL) and distilled water (60 mL) to generate gadolinium oleate complex. The mixture was heated to 70 °C and stirred at that temperature under reflux for 4 h. Subsequently, hexane (20 ml) was added into the system, leading to the dissolution of the upper organic layer, which was collected and washed three times with distilled water in a separating funnel and then concentrated with rotary evaporator. The waxy gadolinium oleate complex (Gd(OA)3) was harvested for further use. The other waxy metal oleate complexes were synthesized following the similar procedure.

2.3 Fabrication of GZCIS QDs

In a typical synthesis of GZCIS QDs, the mixed metal oleate complexes of Cu(OA)2 (0.1 mmol), In(OA)3 (0.2 mmol), Zn(OA)2 (0.1 mmol), Gd(OA)3 (0.4 mmol) and oleic acid (0.5 mL) were mixed with ODE (10 mL) in a four-necked flask. The reaction mixture was degassed under vacuum for 30 min and purged with argon. The reaction solution was heated to 120 °C. When the solution became clear, 1 mL of DDT was injected into the reaction system. At the moment of injection, the color of the solution changed into bright yellow. Then, sulfur precursor (9.7 mg, 0.3 mmol) dissolved in 0.5 mL of oleylamine and 1 mL of ODE solution was quickly injected into the reaction mixture at 205 °C. The reaction mixture was held at 200 °C for 120 min and aliquots of the sample were taken at different time intervals for recording the optical spectra. After completion of particle growth, the mixture was cooled to room temperature. The obtained GZCIS QDs were precipitated by adding ethanol/hexane (v/v, 1/1) into the reaction solution and purified by repeated centrifugations.

2.4 Fabrication of GZCIS/ZnS QDs

Without purification, 4 mL of raw GZCIS QDs solution, 5 mL of ODE and 1 mL of DDT were loaded into a four-necked flask. 0.1 mmol Zn(Ac)2 in ODE/oleylamine (v/v, 4/1, in 1 mL) was injected into the flask under vigorous stirring at room temperature. The mixture was then kept at 220 °C for 20 min to allow the growth of the ZnS shell. The same procedure was repeated for another four times to obtain highly fluorescent GZCIS/ZnS QDs.

2.5 Phase transfer of GZCIS/ZnS QDs to the aqueous phase

The phase transfer was achieved via a bovine serum albumin (BSA) coating strategy developed by Zhang et al [33, 34]. Typically, 15 ml of water containing 0.6 g of BSA was placed under the ultrasonic transducer with a converter. 3 ml of GZCIS/ZnS QDs (15 mg) solution in chloroform was slowly injected into the BSA aqueous solution with ultrasonication. Upon the injection, the mixed QDs/BSA aqueous solution was evaporated by a rotary evaporator to remove chloroform. Then obtained QDs@BSA aqueous solution was purified by centrifugal filter (30K) with ultrapure water for three times to remove the excess BSA.

2.6 MTT Assay

Cytotoxicity of the obtained GZCIS/ZnS QDs was evaluated with two tumor cell lines (HeLa and A549). HeLa or A549 cells growing in log phase were seeded into a 96-well cell-culture plate at 5 ×103/well and incubated in the culture medium at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5 % CO2 and 95 % air. After overnight incubation, the existing RPMI-1640 medium was replaced with fresh medium containing varying amounts of GZCIS/ZnS@BSA nanoclusters. The cells were incubated with nanoclusters for another 24 h and washed twice with medium. Then, 100 μL of the new culture medium containing 10% 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reagent was introduced followed by further incubation for 4 h to allow formation of formazan dye. After removing the medium, the purple formazan product was dissolved with RPMI-1640 for 15 min. Finally, the optical absorption of formazan at 570 nm was measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader.

2.7 In Vivo MR Imaging

The animal experiments were conducted on 6-week-old BALB/c mice. Animal procedures were in agreement with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tongji University. In vivo MR imaging was performed on a 7.0 T MR imaging system (Pharmascan, Bruker, Germany) using anesthetized BALB/c mice (body weight ca. 30 g). Images were obtained at baseline (prior to injection) and at subsequent intervals following injection of 0.05 mmol Gd/kg body weight. T1-weighted images were acquired using a MSME sequence (TR=300ms, TE=8.5ms, Matrix=256×256, FOV=3×3) with respiratory gating technology. Image post-processing was performed using the TopSpin 5.1 software (Bruker, Germany).

2.8 In vivo/Ex vivo Fluorescence Imaging

The mice were kept without any food but water for 12 h to minimize food fluorescence before tail vein injection. Following the intravenous injection of 0.05 mmol Gd/kg body weight of the mice, in vivo fluorescence images of the mice were obtained with a Maestro In vivo Spectrum Imaging System (Cambridge Research & Instrumentation, Woburn, MA). The excitation filter was set as 610 nm; the emission filter was a 700 nm long-pass filter. CCD exposure time was set as a constant (1 s). At 6 h after injection, the mice were sacrificed and the organs were removed for ex vivo fluorescence imaging on the same spectrum imaging system.

3. Result and discussion

As shown in Scheme 1, the synthetic strategy of GZCIS/ZnS QDs was derived from the previous report [32] and was rather straightforward. In this two-step hot-injection procedure, GZCIS QDs were firstly prepared by injecting S precursor into hot metal-oleate complex precursor solution (containing Gd3+, Zn2+, In3+ and Cu2+) at 200 °C. GZCIS NCs were fabricated by rapid nucleation and following 120 min thermal ripening with oleic acid and DDT as surfactants. The resulted GZCIS QDs were subsequently overcoated with a ZnS shell by adding Zn precursor at 220 °C to fabricate GZCIS/ZnS QDs, which were further used for MR and fluorescence dual-modal bioimaging. In this synthetic strategy, it was found that the embedded Zn2+ and Gd3+ play critical roles in preparing doped QDs.

3.1 The Zn/Cu ratio dependent fluorescence of GZCIS QDs

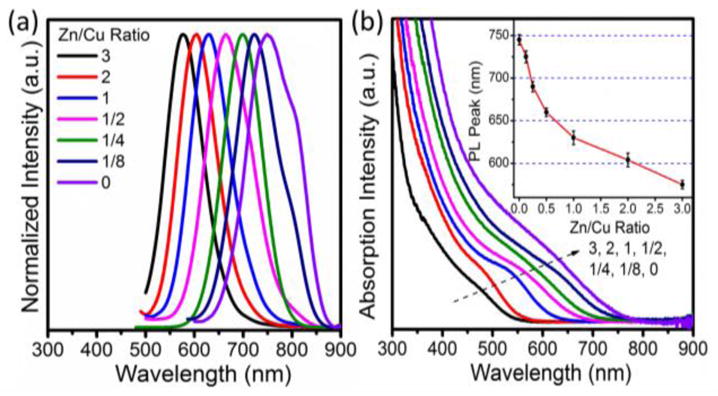

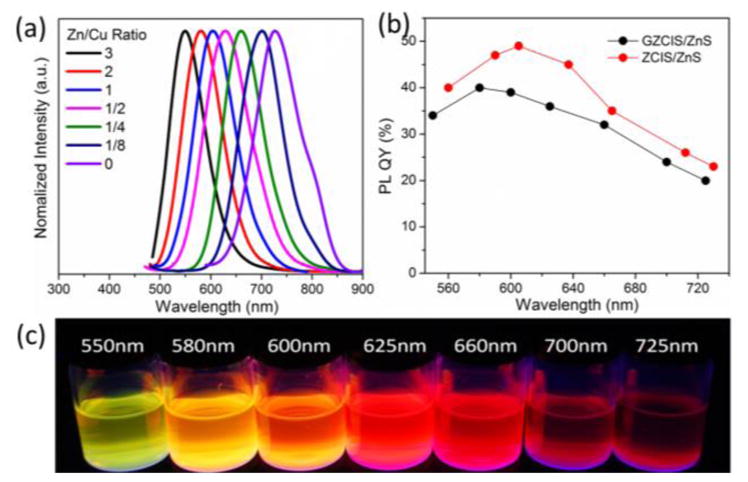

As shown in Figure 1, the optical properties of obtained GZCIS QDs are dependent on the molar ratios of the Zn and Cu precursors. Figure 1(a) and Figure 1(b) (inset) showed that the photoluminescence (PL) emissions of the GZCIS QDs can be precisely tuned in the range from 570 nm to 735 nm by only varying the Zn/Cu ratio. It is noticeable that prolonged reflux time does not result in significant red-shift in the PL emission but does lead to stronger fluorescence intensity at fixed Zn/Cu ratios (Figure S1, see Supporting Information). The constant PL emission with reaction time might be attributed to the inadequate S precursor and the relatively low reaction temperature of 200 °C. At such a low temperature, DDT is unlikely to be decomposed to offer excess sulfur source for the reaction [35, 36]. Consequently, the inadequate S precursor limits the increase of particle size, resulting in the almost constant PL emission throughout the reaction. In this way, the PL emission of GZCIS QDs can be precisely controlled by Zn/Cu ratio with good repeatability as shown in Figure 1(b) (inset). Accordingly, the absorption spectra of GZCIS QDs shifted gradually from UV-vis to NIR with decreasing Zn/Cu ratio from 3 to 0 (Figure 1b). Furthermore, it was also found that the Gd/Cu ratio has little effect on the PL properties of QDs, viz, the QDs fabricated at various Gd/Cu ratios with fixed Zn/Cu ratio had almost the same PL emission properties (see Supporting Information, Figure S1). Consequently, the little effect of reaction time and Gd/Cu ratio on the PL emission contributes to the controllable PL property, which therefore can be precisely tailored by the only parameter of Zn/Cu ratio with a good repeatability.

Figure 1.

The PL spectra (a), absorption spectra (b) and PL peaks (Insert) of GZCIS QDs obtained at various Zn/Cu precursor ratios at fixed Gd/Cu ratio of 4/1.

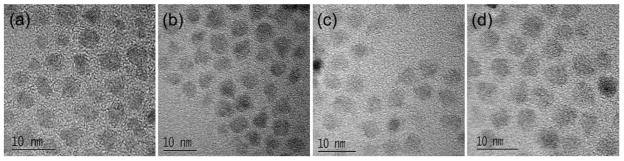

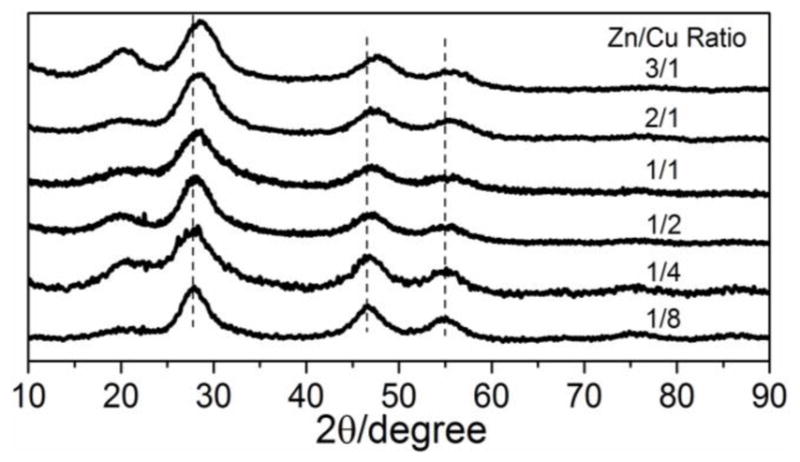

Structure and composition of the GZCIS QDs are investigated to explain the Zn/Cu ratio dependent fluorescence property. Figure 2 shows high revolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) images of the GZCIS NCs prepared with various Zn/Cu ratios. All the resulting NCs are nearly spherical in shape with similar size around 4.0 nm, which excludes the size effect on the shift of the PL emission [22]. When the synthesis was performed at a higher ratio of Zn/Cu, QDs were obtained with a higher fraction of zinc and shorter PL emission, as shown in Figure S1C. Therefore, we conclude that the tunable PL emissions of obtained fluorescence NCs are essentially dependent on the compositions instead of particle sizes [22]. Besides the TEM observation, the crystal structures and compositions of the as-prepared nanoparticles were also clarified by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Figure 3), where the diffraction peaks shifted towards higher angles with increasing Zn/Cu ratio from 1/8 to 3/1, well matching the standard crystal structure patterns for Cu0.412In0.412Zn0.175S (JCPDS 47-1371), Cu0.4In0.4Zn0.2S (JCPDS 47-1370) and Cu0.4In0.4Zn1.2S2 (JCPDS 32-0340), respectively. The small peak shift toward higher 2θ is the characteristic of the increase of introduced Zn2+ [17], and the continuous peak-shift of the NCs revealed no phase separation in this approach, suggesting the formation of Zn-Cu-In-S NCs [17,23]. Furthermore, the amount of Gd3+ incorporated in the NCs was measured in all samples by ICP-MS and summarized in Table 1. Gadolinium content was assessed after washing with chloroform/ethanol five times to remove Gd adsorbed on the surface of NCs [30]. The composition results confirm the successful incorporation of Gd3+ into the obtained nanoparticles and it thus can be concluded that GZCIS QDs are successfully synthesized via this synthetic strategy.

Figure 2.

High revolution TEM images of GZCIS QDs obtained with Zn/Cu feed ratio fixed at 2/1 (a), 1/1 (b), 0.5/1 (c) and 0.25/1 (d).

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of GZCIS QDs obtained with various Zn/Cu feeding ratios at fixed Gd/Cu ratio of 4/1.

Table 1.

Determination of Gd Content for QDs from ICP-MS and Corresponding Relaxivity Parameters from MRI Measurement

| Samples | ICP-MS Results

|

Relaxivity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-shell Gd/cations (atom %) | Post-shell Gd/cations (atom %) | R1 (mM−1·S−1) | R2 (mM−1·S−1) | R2/R1 | |

| Magnevist | -- | -- | 3.76 | 4.61 | 1.23 |

| GZCIS/ZnS(Gd/Cu=2) | 13.7% | 7.9% | 11.53 | 33.75 | 2.93 |

| GZCIS/ZnS(Gd/Cu=4) | 17.4% | 10.6% | 15.78 | 36.09 | 2.29 |

| GZCIS/ZnS(Gd/Cu=6) | 20.6% | 14.3% | 13.65 | 26.45 | 1.94 |

3.2 Optical and magnetic properties of GZCIS/ZnS QDs

Although the as-prepared GZCIS QDs do present fluorescence emission, the PL quantum yields (QYs) are inadequate less than 10%. In order to enhance the fluorescence, an attempt for the inorganic surface passivation was made by in situ growth of ZnS shell on the GZCIS NCs. After the ZnS shell growth, the GZCIS/ZnS QDs maintained spherical shapes with a larger size about 4.3 nm (Figure S2, see Supporting Information). And the PL QYs of GZCIS/ZnS QDs were dramatically enhanced as compared to the GZCIS QDs. Control experiments were also performed to fabricate ZCIS QDs under the identical conditions without adding Gd(OA)3 (details in supporting information). As showed in Figure 4(b), introduction of Gd species resulted slightly decrease on the PL QYs. It has been demonstrated that CIS-based QDs exhibit a defect-dependent PL emission related to copper deficiency [37, 38]. The existence of defect pairs of copper vacancies and In or other cations on Cu antisite contributes to the PL emission of CIS-based QDs following a donor acceptor pair (DAP) recombination mechanism [38]. The introduction of Gd species creates more defects thus can potentially increase photoluminescence. On the other hand, the paramagnetic Gd3+ ions could also compromise the fluorescence. The balance of these two competitive effects leads to slight decrease in QYs. The emission color of the GZCIS/ZnS QDs covers a broad range from about 550 to 725 nm, the most part of the visible window and a significant portion of the near-infrared window that is relevant to in vivo imaging [39, 40].

Figure 4.

PL emission spectra (a), quantum yields (b) and digital pictures (c) of the obtained GZCIS/ZnS NCs with different PL peaks. All the GZCIS/ZnS QDs were prepared with Gd/Cu ratio fixed at 4/1.

GZCIS/ZnS NCs were successfully suspended in water via BSA coating for the relaxivity test. R1 relaxivity, a concentration-independent measure of the effectiveness of a paramagnetic material, was derived from the slope of inverse relaxation time (1/T1) versus Gd concentration. The GZCIS/ZnS QDs prepared at the initial Gd/Cu ratio of 2/1, 4/1 and 6/1 showed R1 values of 11.53, 13.65 and 15.78 mM−1·S−1, respectively, while the commercial contrast agent Magnevist® (Gd-DTPA) revealed much lower R1 value of 3.76 mM−1·S−1 under the same measurement conditions (Figure 5a). It is noteworthy that the R2/R1 ratio is an important parameter to estimate the efficiency of T1 contrast agents and the contrast agent with lower R2/R1 ratio would show a stronger T1 effect [41]. All the obtained paramagnetic QDs possessed a remarkably low R2/R1 ratio of less than 2.5 (see Supporting Information, Figure S3), suggesting that these GZCIS/ZnS QDs are efficient T1 contrast agents.

Figure 5.

(a) Linear relationship between T1 relaxation rate (1/T1) and Gd concentration for GZCIS/ZnS with different Gd/Cu ratios and Magnevist. (b), Fluorescence (top) and T1-weighted MR images of GZCIS/ZnS QDs and Magnevist at various Gd contrations. Here GZCIS/ZnS QDs were prepared with Gd/Cu and Zn/Cu ratio fixed at 4 and 2, respectively. The QDs present fluorescence emission at 580 nm.

In order to confirm that Gd content was sufficient to produce contrast in an MR image at the concentration used for optical imaging, GZCIS/ZnS QDs prepared with Gd/Cu and Zn/Cu feeding ratios at 4 and 2 with fluorescence emission at 580 nm were tested by MRI and fluorescence imaging (Figure 5b). Due to the much higher R1 value, QDs produced better T1 contrast than Magnevist at the same Gd concentration. The same concentrations of QDs employed for the MR studies were also photographed using a handheld UV lamp as the excitation source (Figure 5b, top row). The above results reveal that GZCIS/ZnS QDs have both gratifying fluorescence and MR enhancement ability without compromising the properties of the each component in isolation.

3.3 Fluorescence and MR dual-modality Imaging

Prior to the biological applications, the colloidal stability profiles of the obtained GZCIS/ZnS@BSA were investigated in detail (Figure S4). Hydrodynamic diameters (HDs) of the obtained GZCIS/ZnS@BSA nanohybrids were recorded in water, PBS (1x) and human serum, respectively (Figure S4B). GZCIS/ZnS@BSA had negligible change in HD size when kept in water and PBS. Exposure to human serum led to an increase to 70 nm in 2 h, which is most likely due to protein corona formation around the nanoparticle surface. There was no further increase to HD size over time, excluding the possibility of particle aggregation. The temporal evolution HD profile depicts a very good colloidal stability of the GZCIS/ZnS@BSA in water, PBS as well as biological media (e.g. serum).

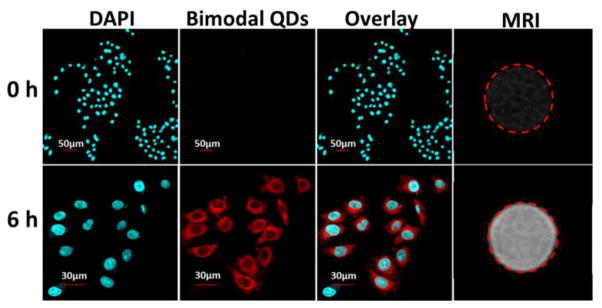

In vitro cellular dual-modal imaging was performed to confirm the utility of the GZCIS/ZnS QDs for biological applications. HeLa cells were incubated with the GZCIS/ZnS@BSA nanoclusters at the Gd concentration of 0.1 mM. As shown in Figure 6, the fluorescence images could well outline the whole cell except for the nucleus region and the MR signal was intensely enhanced after the cells were incubated with GZCIS/ZnS QDs for 6 h, indicating effective cell uptake of the doped QDs.

Figure 6.

The confocal fluorescence and MR images of HeLa cells before and 6 h after incubation with GZCIS/ZnS@BSA at the Gd concentration of 0.1 mM. The cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Here involved GZCIS/ZnS QDs showed PL emission at 625 nm and were prepared with Gd/Cu and Zn/Cu ratio fixed at 4/1 and 1/2, respectively.

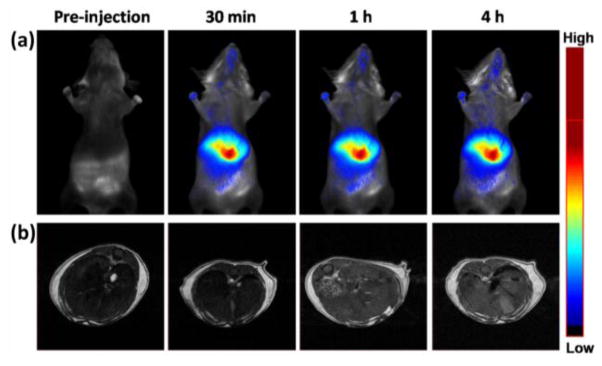

For in vivo imaging, the tested GZCIS/ZnS QDs emitting at 700 nm are transferred into water phase via a BSA coating strategy. The cytotoxicity of the obtained QDs was also tested on two cell lines (HeLa and A549), and no apparent cell viability loss was found after incubation with QDs even at a concentration of 500 μg/mL for 24 h (Figure S5). To assess the feasibility of GZCIS/ZnS QDs as a dual-modal contrast agent, the GZCIS/ZnS@BSA nanohybrids were injected intravenously into BALB/c mice at a dosage of 0.05 mmol Gd/kg for both fluorescence and MR imaging. As shown in Figure 7, QDs were rapidly accumulated in the liver as early as 0.5 h. At 6 h post injection (p.i.), the mice were sacrificed and major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidneys) were imaged ex vivo (Figure S6). Majority of the QDs were remained in the reticuloendothelial system (RES) organs such as liver and spleen. No detectable fluorescence in the kidneys suggests that QDs of this size do not have renal clearance.

Figure 7.

The fluorescence in vivo images (a) and T1-weighted transverse MR images (b) of the liver of BALB/c mice acquired before and at various time points post-injection of GZCIS/ZnS at a dose of 0.05 mmol Gd/kg mouse body weight.

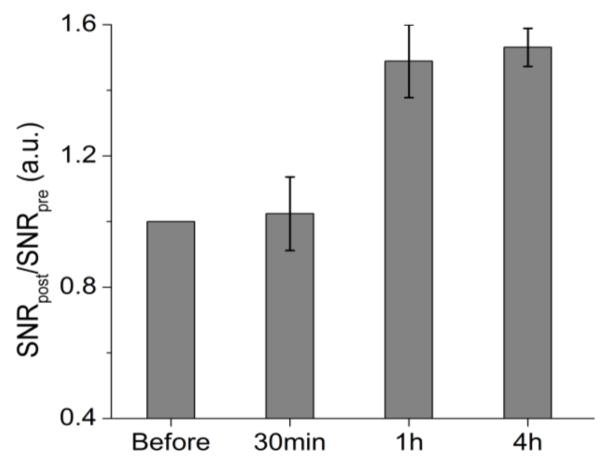

In parallel to the fluorescence imaging experiment, we also conducted in vivo MR imaging studies for the GZCIS/ZnS bimodal QDs on a 7.0 T MRI scanner. As showed in Figure 7b, we acquired the T1-weighted MR images before and various time points after intravenous injection of the bimodal QDs, with the same dose of 0.05 mmol Gd/kg of mouse body weight as that used for optical imaging. Because of the high RES accumulation of the nanoparticles, we focused on imaging the liver area by acquiring the transverse images. To quantify the contrast, we calculated the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) by analyzing regions of interests (ROIs) of the MR images and calculated the values of SNRpost/SNRpre to represent the signal changes. ROIs analysis in Figure 8 showed that signal changes in the liver region were 1.05±0.12, 1.49±0.11 and 1.55±0.06 at 0.5, 1 and 4 h p.i., respectively. T1-weighted MR images exhibited significantly enhanced liver signal at 1 h time point as compared with that before QD injection, which agrees well with the fluorescence imaging results. Based on the above animal experiments, it can be concluded that here fabricated GZCIS/ZnS QDs could be a qualified dual-modal contrast agent to simultaneously show strong MR contrast enhancement as well as fluorescence emission for in vivo imaging, which can provide more comprehensive imaging information and lead to higher diagnostic accuracy, particularly in the detection and diagnosis of lesions in the liver.

Figure 8.

Signal change (SNR ratio) in the liver at different time points after administration of GZCIS/ZnS (0.05 mmol Gd/kg, n = 3). The SNR values were calculated according to SNRROIs =SIROIs/SInoise (SI denotes signal intensity).

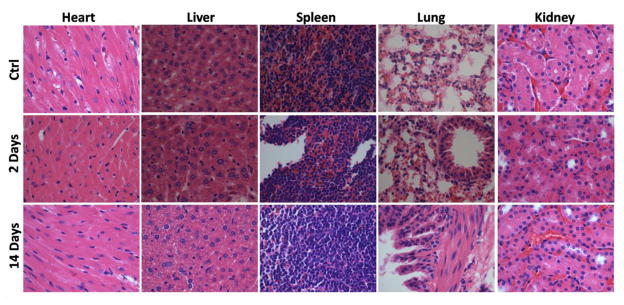

Since the toxicity of leaked gadolinium can be a major factor impacting the application of Gd-containing agents, H&E staining examination was carried out to evaluate the potential toxicity of GZCIS/ZnS QDs (Figure 9). Major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) were collected at 2 and 14 days post-injection. Gross evaluation and histopathology revealed no organ abnormality or lesion in QD administrated mice, indicating good biocompatibility of the obtained GZCIS/ZnS QDs as dual-modal contrast agent.

Figure 9.

H&E stained images of major organs collected from control and GZCIS/ZnS@BSA administrated mice at 2 and 14 days post injection.

4. Conclusion

We put forward a facile strategy to fabricate a class of novel color-tunable Cd-free GZCIS/ZnS core/shell quantum dot nanocrystals, which allows incorporation of high levels of Gd into the quantum dots to achieve superior MR enhancement without sacrificing the fluorescence quantum yields. The obtained bimodal QDs are sufficient to offer contrast for the both fluorescence and magnetic resonance imaging. This type of new Gd containing QDs shows low toxicity as well as good colloidal stability without obvious Gd dissociation. The current formula with BSA capping is an effective liver imaging agent. With proper modification of the surface chemistry, the QDs developed here are expected to have the ability to have other target specificity as well.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National High Technology Program of China (2012AA022603), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51373117, 81171372 and 81371596), The Key Project of Tianjin Nature Science Foundation (13JCZDJC33200), Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (20120032110027), and the Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health. W. G. was funded in part by the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Appendix

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Material: Supplementary material (including PL emission peaks and compositions of GZCIS QDs, TEM images of GZCIS/ZnS bimodal QDs, XRD patterns, linear relationship between T2 relaxation rates (1/T2) and Gd cation concentrations, DLS data of GZCIS/ZnS@BSA, MTT assay, ROI analysis of ex vivo fluorescence images) is available in the online version of this article at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12274-***-****-*.

Contributor Information

Bingbo Zhang, Email: bingbozhang@tongji.edu.cn.

Jin Chang, Email: jinchang@tju.edu.cn.

Xiaoyuan Chen, Email: shawn.chen@nih.gov.

References

- 1.Xie J, Chen K, Huang J, Lee S, Wang J, Gao J, Li X, Chen X. PET/NIRF/MRI triple functional iron oxide nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3016–3022. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauffer RB. Paramagnetic metal complexes as water proton relaxation agents for NMR imaging: theory and design. Chem Rev. 1987;87:901–927. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai CP, Hung Y, Chou YH, Huang DM, Hsiao JK, Chang C, Chen YC, Mou CY. High-Contrast Paramagnetic Fluorescent Mesoporous Silica Nanorods as a Multifunctional Cell Imaging Probe. Small. 2008;4:186–191. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulder WJ, Strijkers GJ, van Tilborg GA, Griffioen AW, Nicolay K. Lipid-based nanoparticles for contrast-enhanced MRI and molecular imaging. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:142–164. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridot JL, Faure AC, Laurent S, Riviere C, Billotey C, Hiba B, Janier M, Josserand V, Coll JL, Vander Elst L. Hybrid gadolinium oxide nanoparticles: multimodal contrast agents for in vivo imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5076–5084. doi: 10.1021/ja068356j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang B, Jin H, Li Y, Chen B, Liu S, Shi D. Bioinspired synthesis of gadolinium-based hybrid nanoparticles as MRI blood pool contrast agents with high relaxivity. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:14494–14501. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao J, Chen K, Xie R, Xie J, Yan Y, Cheng Z, Peng X, Chen X. In vivo tumor-targeted fluorescence imaging using near-infrared non-cadmium quantum dots. Bioconjugate chem. 2010;21:604–609. doi: 10.1021/bc900323v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao J, Chen K, Xie R, Xie J, Lee S, Cheng Z, Peng X, Chen X. Ultrasmall Near-Infrared Non-cadmium Quantum Dots for in vivo Tumor Imaging. Small. 2010;6:256–261. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheon J, Lee J-H. Synergistically integrated nanoparticles as multimodal probes for nanobiotechnology. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1630–1640. doi: 10.1021/ar800045c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jennings LE, Long NJ. ‘Two is better than one’-probes for dual-modality molecular imaging. Chem Commun. 2009:3511–3524. doi: 10.1039/b821903f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kircher MF, Mahmood U, King RS, Weissleder R, Josephson L. A multimodal nanoparticle for preoperative magnetic resonance imaging and intraoperative optical brain tumor delineation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8122–8125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruchez M, Moronne M, Gin P, Weiss S, Alivisatos AP. Semiconductor nanocrystals as fluorescent biological labels. Science. 1998;281:2013–2016. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan WC, Nie S. Quantum dot bioconjugates for ultrasensitive nonisotopic detection. Science. 1998;281:2016–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Daou TJ, Texier I, Kim Chi TT, Liem NQ, Reiss P. Highly luminescent CuInS2/ZnS core/shell nanocrystals: cadmium-free quantum dots for in vivo imaging. Chem Mater. 2009;21:2422–2429. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cassette E, Pons T, Bouet C, Helle M, Bezdetnaya L, Marchal F, Dubertret B. Synthesis and characterization of near-infrared Cu- In- Se/ZnS core/shell quantum dots for in vivo imaging. Chem Mater. 2010;22:6117–6124. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pons T, Pic E, Lequeux N, Cassette E, Bezdetnaya L, Guillemin F, Marchal F, Dubertret B. Cadmium-free CuInS2/ZnS quantum dots for sentinel lymph node imaging with reduced toxicity. ACS Nano. 2010;4:2531–2538. doi: 10.1021/nn901421v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo W. Synthesis of Zn-Cu-In-S/ZnS Core/Shell Quantum Dots with Inhibited Blue-Shift Photoluminescence and Applications for Tumor Targeted Bioimaging. Theranostics. 2013;3:99. doi: 10.7150/thno.5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yong KT, Roy I, Hu R, Ding H, Cai H, Zhu J, Zhang X, Bergey EJ, Prasad PN. Synthesis of ternary CuInS2/ZnS quantum dot bioconjugates and their applications for targeted cancer bioimaging. Integrative Biology. 2010;2:121–129. doi: 10.1039/b916663g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng D, Chen Y, Cao J, Tian J, Qian Z, Achilefu S, Gu Y. High-quality CuInS2/ZnS quantum dots for in vitro and in vivo bioimaging. Chem Mater. 2012;24:3029–3037. [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Trizio L, Prato M, Genovese A, Casu A, Povia M, Simonutti R, Alcocer MJ, D’Andrea C, Tassone F, Manna L. Strongly Fluorescent Quaternary Cu–In–Zn–S Nanocrystals Prepared from Cu1-x InS2 Nanocrystals by Partial Cation Exchange. Chem Mater. 2012;24:2400–2406. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo W, Chen N, Dong C, Tu Y, Chang J, Zhang B. One-pot synthesis of hydrophilic ZnCuInS/ZnS quantum dots for in vivo imaging. RSC Advances. 2013;3:9470–9475. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Xie R, Yang W. A simple route for highly luminescent quaternary Cu-Zn-In-S nanocrystal emitters. Chem Mater. 2011;23:3357–3361. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, Zhong X. Facile Synthesis of ZnS–CuInS2-Alloyed Nanocrystals for a Color-Tunable Fluorchrome and Photocatalyst. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:4065–4072. doi: 10.1021/ic102559e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding K, Jing L, Liu C, Hou Y, Gao M. Magnetically engineered Cd-free quantum dots as dual-modality probes for fluorescence/magnetic resonance imaging of tumors. Biomaterials. 2014;35:1608–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S, Jarrett BR, Kauzlarich SM, Louie AY. Core/shell quantum dots with high relaxivity and photoluminescence for multimodality imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3848–3856. doi: 10.1021/ja065996d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Ai K, Yuan Q, Lu L. Fluorescence-enhanced gadolinium-doped zinc oxide quantum dots for magnetic resonance and fluorescence imaging. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1185–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li IF, Yeh C-S. Synthesis of Gd doped CdSe nanoparticles for potential optical and MR imaging applications. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:2079–2081. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Q, Deng R, Ji X, Pan D. Alloyed Mn–Cu–In–S nanocrystals: a new type of diluted magnetic semiconductor quantum dots. Nanotechnology. 2012;23:255706. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/23/25/255706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu C, Ma X, Pantazis P, Kauzlarich SM, Louie AY. Paramagnetic, silicon quantum dots for magnetic resonance and two-photon imaging of macrophages. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2016–2023. doi: 10.1021/ja909303g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, Jarrett BR, Kauzlarich SM, Louie AY. Core/shell quantum dots with high relaxivity and photoluminescence for multimodality imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3848–3856. doi: 10.1021/ja065996d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park J, An K, Hwang Y, Park JG, Noh HJ, Kim JY, Park JH, Hwang NM, Hyeon T. Ultra-large-scale syntheses of monodisperse nanocrystals. Nat Mater. 2004;3:891–895. doi: 10.1038/nmat1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Z, Huang D, Bao J, Chen Q, Liu G, Chen Z, Chen X, Gao J. A Synergistically Enhanced T1–T2 Dual-Modal Contrast Agent. Adv Mater. 2012;24:6223–6228. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang B, Li Q, Yin P, Rui Y, Qiu Y, Wang Y, Shi D. Ultrasound-triggered BSA/SPION hybrid nanoclusters for liver-specific magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2012;4:6479–6486. doi: 10.1021/am301301f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang B, Wang X, Liu F, Cheng Y, Shi D. Effective reduction of nonspecific binding by surface engineering of quantum dots with bovine serum albumin for cell-targeted imaging. Langmuir. 2012;28:16605–16613. doi: 10.1021/la302758g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xie R, Rutherford M, Peng X. Formation of high-quality I– III– VI semiconductor nanocrystals by tuning relative reactivity of cationic precursors. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5691–5697. doi: 10.1021/ja9005767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong H, Zhou Y, Ye M, He Y, Ye J, He C, Yang C, Li Y. Controlled synthesis and optical properties of colloidal ternary chalcogenide CuInS2 nanocrystals. Chem Mater. 2008;20:6434–6443. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nam DE, Song WS, Yang H. Noninjection, one-pot synthesis of Cu-deficient CuInS2/ZnS core/shell quantum dots and their fluorescent properties. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;361:491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen B, Zhong H, Zhang W, Tan Za, Li Y, Yu C, Zhai T, Bando Y, Yang S, Zou B. Highly Emissive and Color-Tunable CuInS2-Based Colloidal Semiconductor Nanocrystals: Off Stoichiometry Effects Improved Electroluminescence Performance. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:2081–2088. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frangioni JV. In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He X, Gao J, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. Near-infrared fluorescent nanoprobes for cancer molecular imaging: status and challenges. Trends in molecular medicine. 2010;16:574–583. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim BH, Lee N, Kim H, An K, Park YI, Choi Y, Shin K, Lee Y, Kwon SG, Na HB. Large-scale synthesis of uniform and extremely small-sized iron oxide nanoparticles for high-resolution T 1 magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12624–12631. doi: 10.1021/ja203340u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.