Abstract

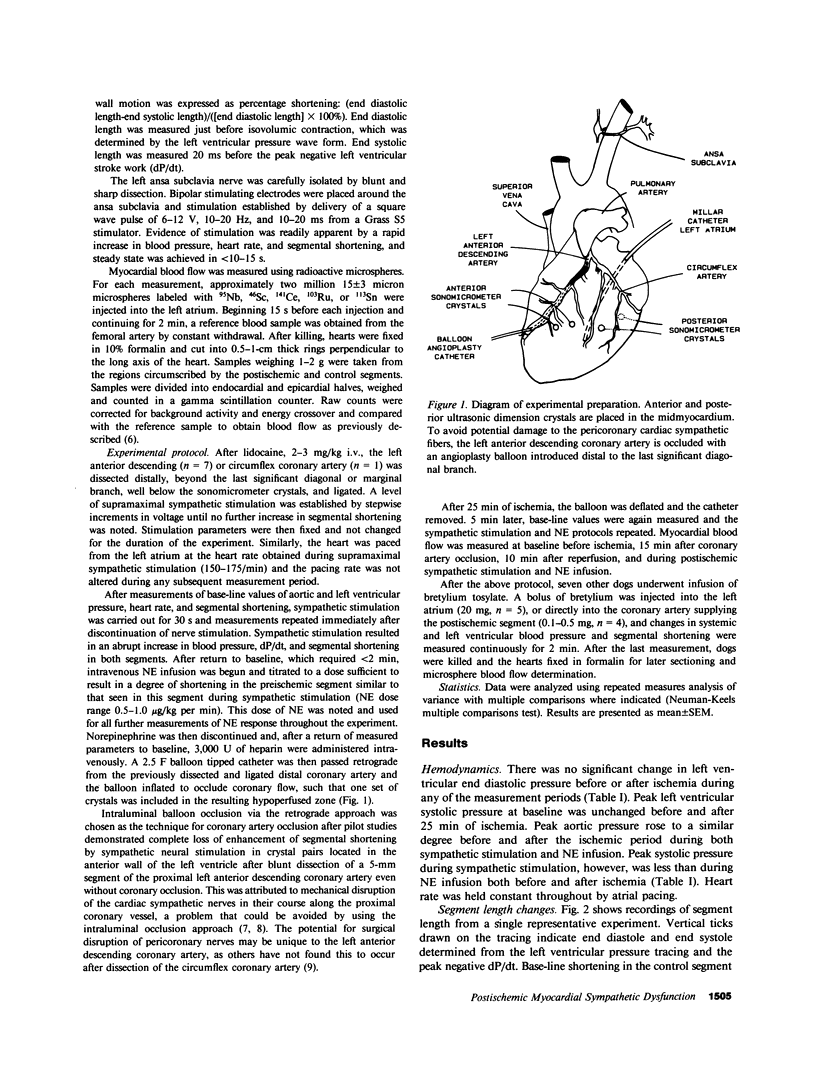

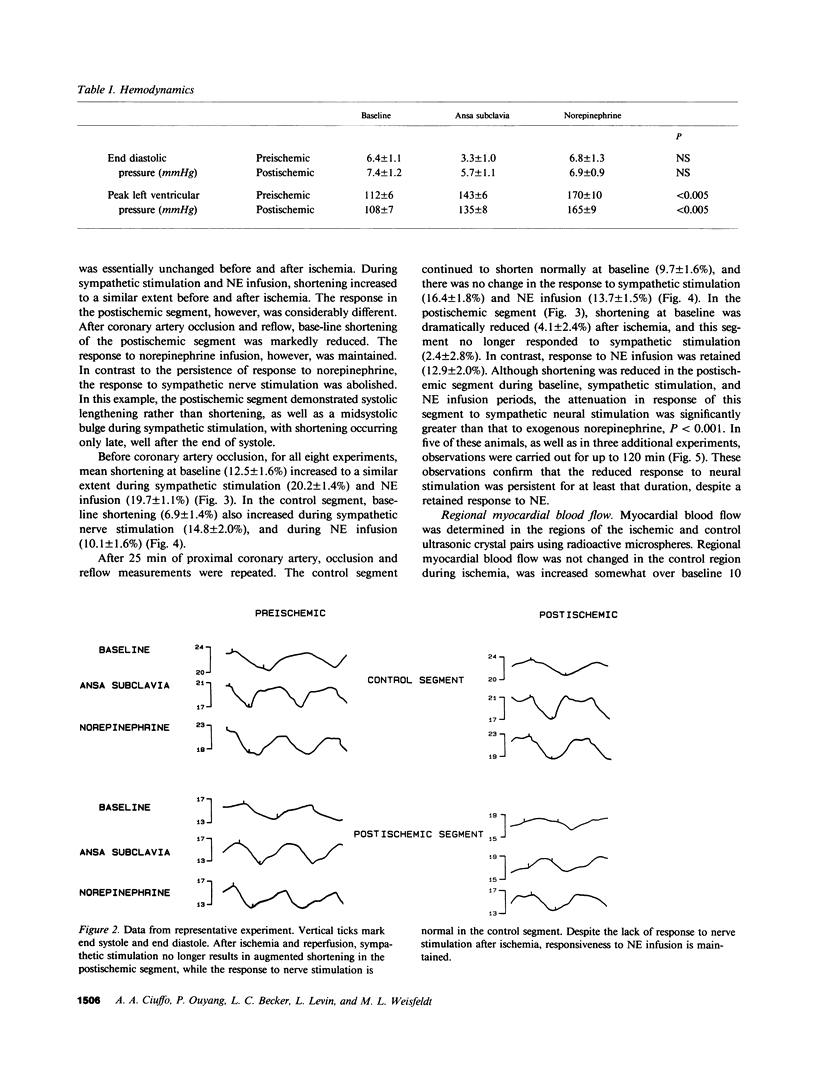

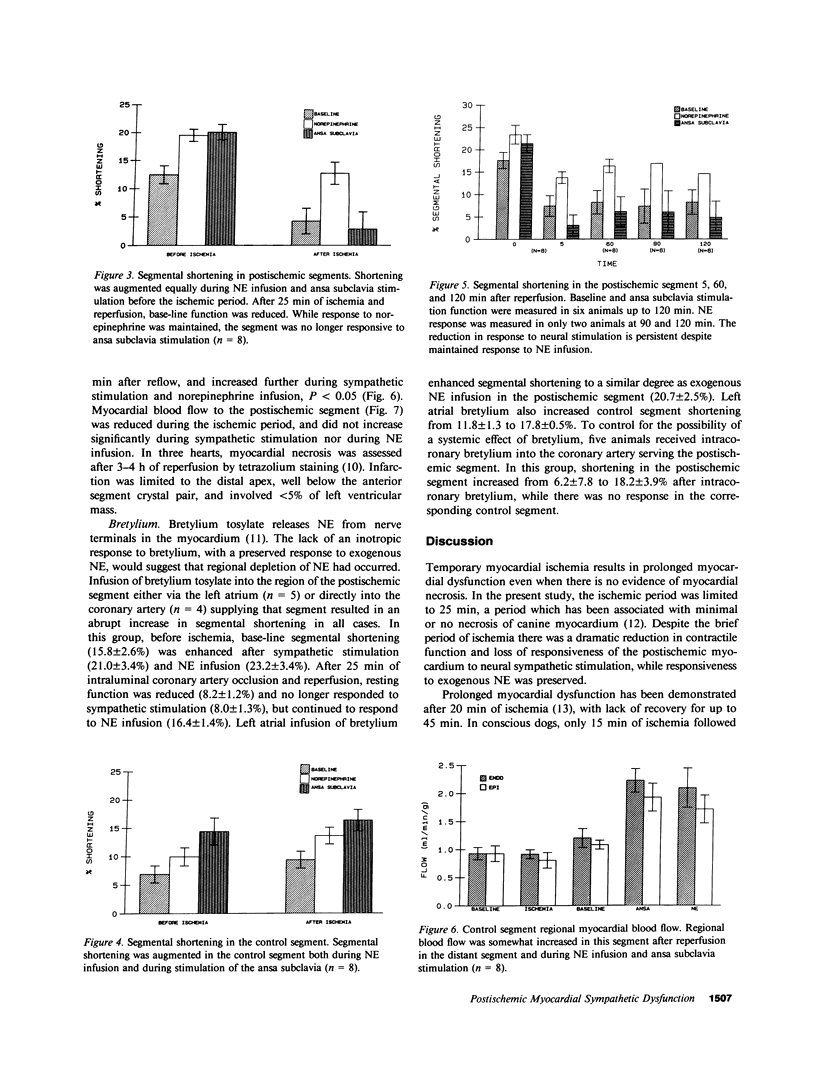

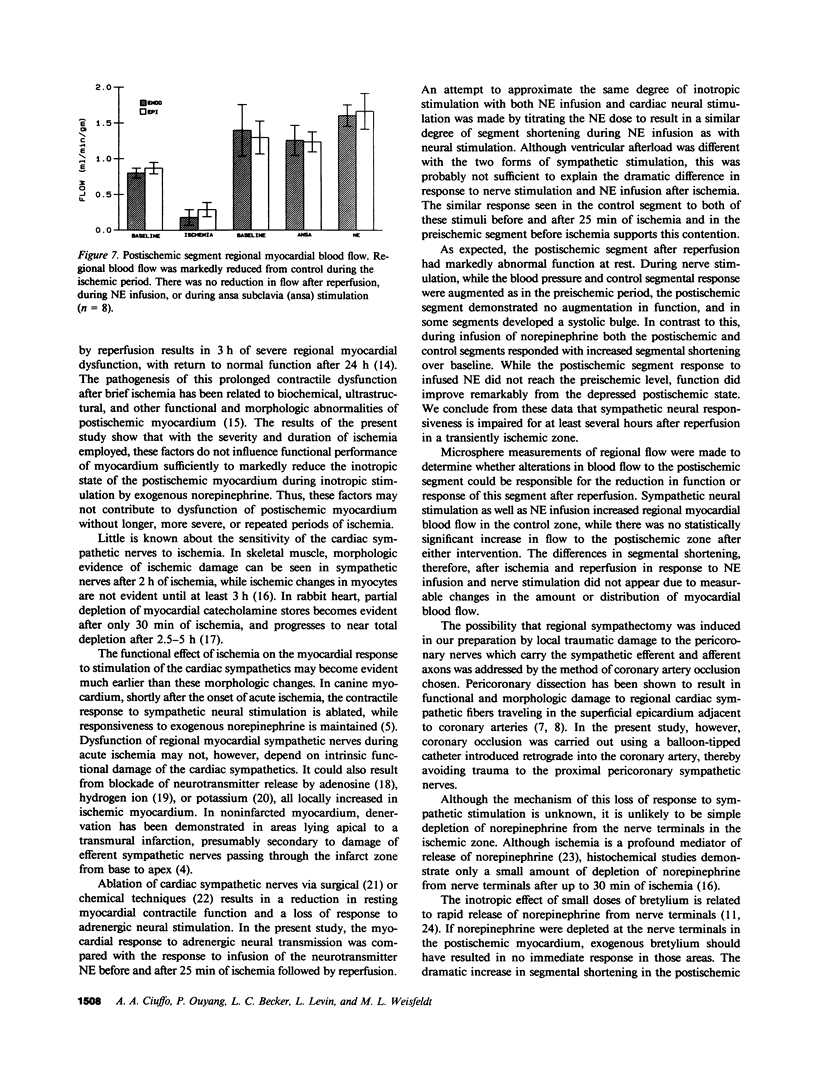

Eight open chest dogs underwent 25 min of coronary occlusion to determine whether brief myocardial ischemia disrupts the normal myocardial inotropic response to sympathetic nervous stimulation. If so, this could represent a mechanism contributing to postischemic myocardial dysfunction. Myocardial segment shortening was measured using ultrasonic dimension crystals before and after coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion. Left ansa subclavia stimulation and systemic norepinephrine (NE) infusion were used to test the myocardial inotropic response to neural stimulation and direct exposure to the sympathetic mediator, respectively. Before coronary artery occlusion, base-line preischemic segment shortening (12.5 +/- 1.6%) (SEM) increased during both sympathetic stimulation (20.2 +/- 1.4%) and NE infusion (19.7 +/- 1.1%). The control segment responded similarly. After ischemia and reperfusion there was no significant change in heart rate, aortic or left ventricular pressures, nor changes in control segment shortening. In contrast, shortening in the postischemic segment was markedly reduced compared to baseline (4.1 +/- 2.4%), and no longer responded to sympathetic stimulation (2.4 +/- 2.8%), while responsiveness to systemic NE was maintained (12.9 +/- 2.0%), P less than 0.001, which suggested injury to the sympathetic-neural axis during the period of ischemia. This reduced response to neural stimulation was persistent for up to 2 h after reperfusion. Left atrial or intracoronary infusion of bretylium tosylate, which releases norepinephrine from nerve terminals, resulted in an immediate inotropic response in the postischemic segment, which indicated that total depletion of NE from nerve terminals during the ischemic period had not occurred. Disruption of sympathetic neural responsiveness is likely a component of the mechanism of postischemic myocardial dysfunction whenever there is appreciable sympathetic drive to the heart.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abbs E. T., Pycock C. J. The effects of bretylium on the subcellular distribution of noradrenaline and on adrenergic nerve function in rat heart. Br J Pharmacol. 1973 Sep;49(1):11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1973.tb08263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamsson T., Almgren O., Svensson L. Local noradrenaline release in acute myocardial ischemia: influence of catecholamine synthesis inhibition and beta-adrenoceptor blockade on ischemic injury. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1981 Jul-Aug;3(4):807–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal G., Silk P., Glotfelty E., Levowitz B. S. Effect of epicardiectomy on myocardial function. Surgery. 1967 Mar;61(3):399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber M. J., Mueller T. M., Henry D. P., Felten S. Y., Zipes D. P. Transmural myocardial infarction in the dog produces sympathectomy in noninfarcted myocardium. Circulation. 1983 Apr;67(4):787–796. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogen D. K., Rabinowitz S. A., Needleman A., McMahon T. A., Abelmann W. H. An analysis of the mechanical disadvantage of myocardial infarction in the canine left ventricle. Circ Res. 1980 Nov;47(5):728–741. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer L. W., Ingwall J. S., Kloner R. A., Braunwald E. Prolonged derangements of canine myocardial purine metabolism after a brief coronary artery occlusion not associated with anatomic evidence of necrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Sep;77(9):5471–5475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.9.5471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezel S., Gerová M., Hartmannová B., Dostál M., Janecková H., Vasku J. Cardiac adrenergic innervation after instrumentation of the coronary artery in dog. Am J Physiol. 1984 Mar;246(3 Pt 2):H459–H465. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.3.H459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis S. G., Henschke C. I., Sandor T., Wynne J., Braunwald E., Kloner R. A. Time course of functional and biochemical recovery of myocardium salvaged by reperfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983 Apr;1(4):1047–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyndrickx G. R., Baig H., Nellens P., Leusen I., Fishbein M. C., Vatner S. F. Depression of regional blood flow and wall thickening after brief coronary occlusions. Am J Physiol. 1978 Jun;234(6):H653–H659. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.234.6.H653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren S., Abrahamsson T., Almgren O., Eriksson B. M. Effect of ischaemic on the adrenergic neurons of the rat heart: a fluorescence histochemical and biochemical study. Cardiovasc Res. 1981 Dec;15(12):680–689. doi: 10.1093/cvr/15.12.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings R. B. Early phase of myocardial ischemic injury and infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1969 Dec;24(6):753–765. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(69)90464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen U. J., Mark A. L., Marcus M. L. Responsiveness to cardiac sympathetic nerve stimulation during maximal coronary dilation produced by adenosine. Circ Res. 1982 Apr;50(4):510–517. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.4.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz R. R., Vanhoutte P. M. Inhibition of adrenergic neurotransmission in isolated veins of the dog by potassium ions. J Physiol. 1975 Mar;246(2):479–500. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malliani A., Lombardi F., Pagani M. Functions of afferents in cardiovascular sympathetic nerves. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1981 Apr;3(2-4):231–236. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(81)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins J. B., Kerber R. E., Marcus M. L., Laughlin D. L., Levy D. M. Inhibition of adrenergic neurotransmission in ischaemic regions of the canine left ventricle. Cardiovasc Res. 1980 Feb;14(2):116–124. doi: 10.1093/cvr/14.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace J. B., Geis W. P., Kaye M. P., Priola D. V. Influence of ventricular epicardiectomy on cardiac responses to stellate ganglion stimulation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1969 Jul;58(1):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig M., Kirpekar S. M. Inhibitory effect of low pH on norepinephrine release. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1971 Jan;176(1):134–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen M. M., Reimer K. A., Kloner R. A., Jennings R. B. Infarct size reduction by propranolol before and after coronary ligation in dogs. Circulation. 1977 Nov;56(5):794–798. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.5.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas F., Cobb F. R., Bache R. J., Greenfield J. C., Jr Relationship between blood flow to ischemic regions and extent of myocardial infarction. Serial measurement of blood flow to ischemic regions in dogs. Circ Res. 1976 May;38(5):439–447. doi: 10.1161/01.res.38.5.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper J., Schaper W. Reperfusion of ischemic myocardium: ultrastructural and histochemical aspects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983 Apr;1(4):1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silinsky E. M. The effects of bretylium and guanethidine on catecholaminergic transmission in an invertebrate. Br J Pharmacol. 1974 Jul;51(3):367–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1974.tb10671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teräväinen H., Mäkitie J. The effect of temporary ischemia on the perivascular sympathetic nerves. Exp Neurol. 1976 Oct;53(1):178–188. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(76)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe R. H., Vanhoutte P. M., Shepherd J. T. Inhibition of sympathetic neurotransmission in canine blood vessels by adenosine and adenine nucleotides. Circ Res. 1977 Feb;40(2):208–215. doi: 10.1161/01.res.40.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J. M., Astein C. S., Arthur J. H., Pirzada F. A., Hood W. B., Jr Persistence of myocardial injury following brief periods of coronary occlusion. Cardiovasc Res. 1976 Nov;10(6):678–686. doi: 10.1093/cvr/10.6.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]