Abstract

The high chloride content of 0.9% saline leads to adverse pathophysiological effects in both animals and healthy human volunteers, changes not seen after balanced crystalloids. Small randomized trials confirm that the hyperchloremic acidosis induced by saline also occurs in patients, but no clinical outcome benefit was demonstrable when compared with balanced crystalloids, perhaps due to a type II error. A strong signal is emerging from recent large propensity-matched and cohort studies for the adverse effects that 0.9% saline has on the clinical outcome in surgical and critically ill patients when compared with balanced crystalloids. Major complications are the increased incidence of acute kidney injury and the need for renal replacement therapy, and that pathological hyperchloremia may increase postoperative mortality. However, there are no large-scale randomized trials comparing 0.9% saline with balanced crystalloids. Some balanced crystalloids are hypo-osmolar and may not be suitable for neurosurgical patients because of their propensity to cause brain edema. Saline may be the solution of choice used for the resuscitation of patients with alkalosis and hypochloremia. Nevertheless, there is evidence to suggest that balanced crystalloids cause less detriment to renal function than 0.9% saline, with perhaps better clinical outcome. Hence, we argue that chloride-rich crystalloids such as 0.9% saline should be replaced with balanced crystalloids as the mainstay of fluid resuscitation to prevent ‘pre-renal' acute kidney injury.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, balanced crystalloids, hyperchloremic acidosis, intravenous fluids, morbidity, 0.9% saline

Any rational approach to fluid and electrolyte therapy and volume resuscitation must take into account the evolved mammalian responses to stress, starvation, injury, or infection. These responses preserve the blood supply to essential organs, allowing time for the individual to recover, and activate the host defense and repair pathways. In simple terms, the major evolved responses relevant to fluid management are as follows:

Maintenance of perfusion of the heart, brain, and lungs at the expense of the cutaneous, splanchnic, and renal circulations.

Fluid shifts from the intracellular and interstitial compartments to replenish the depleted vascular compartment.

An increase in systemic vascular permeability allowing proteins such as immunoglobulins and albumin, with their attendant fluid, to move from the vascular space into the interstitial compartment.

Intense sodium and water retention by the kidneys to augment the reduced circulating blood volume.

In addition to the evolutionary response to conserve salt and water, the patient's ability to excrete administered salt and water is also limited by renal compromise and reduced ability to concentrate urine. As a consequence, it requires 2–4 times the normal volume of urine to excrete the sodium and chloride load administered, which competes with excretion of nitrogen resultant from catabolic stress during critical illness, resulting in interstitial edema.

Although Evans1 commented on the dangers of the reckless way in which salt solutions were prescribed as early as 1911, the clinical effects of salt and water excess have largely been ignored till relatively recently, with continued inappropriate and excessive use of chloride-rich crystalloid infusions, such as 0.9% saline, both within the settings of resuscitation and maintenance. The development of balanced crystalloids highlights the need to reappraise the continued use of 0.9% saline, especially considering the detrimental effects the latter has on renal function. In this debate we argue against the use of this unphysiological crystalloid, more appropriately termed ‘abnormal saline',2, 3 and appraise both historical and recent data that support the argument.

RATIONALE FOR FLUID RESUSCITATION—THE KIDNEY

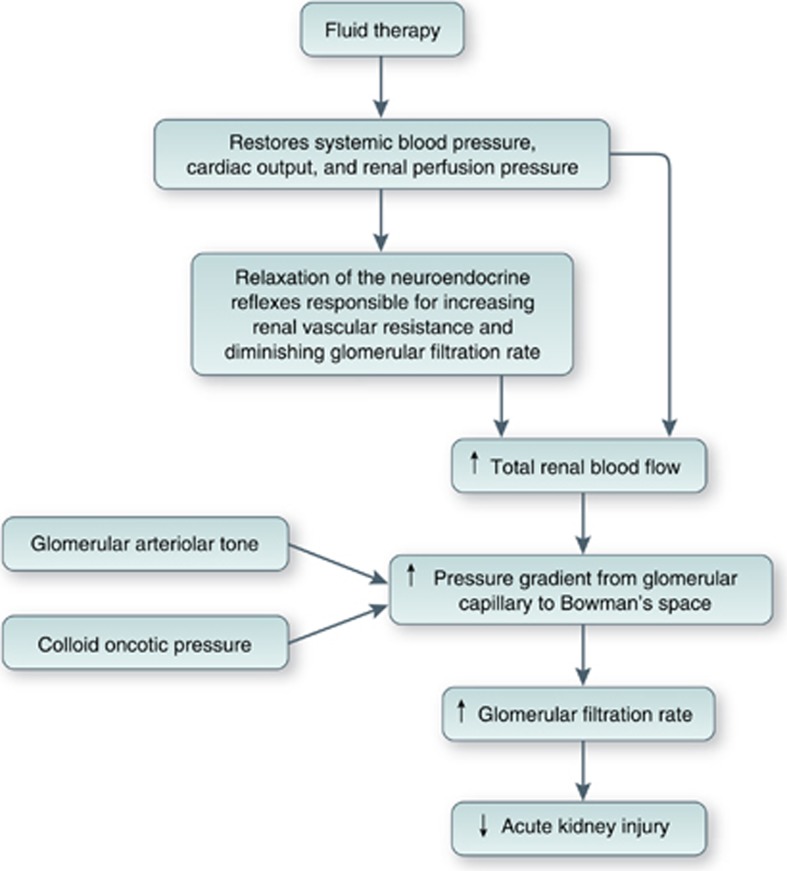

From the renal perspective, the aim of fluid resuscitation of the hypovolemic patient is to improve renal blood flow, increase glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and reduce the incidence of acute kidney injury (Figure 1). However, the ability of fluid therapy to achieve this aim is dependent on a number of other factors including the type of fluid used and the effects of acute illness, chronic disease, and drugs that may alter determinants of fluid responsiveness. The latter include systemic vascular resistance, myocardial compliance and contractility, regional blood flow distribution, venous capacitance, and capillary permeability.4 Teleologically, the kidney is better adapted to conservation of salt and water than to excreting an excess of either.5 In addition, factors such as hypotension, pain, and injury activate the sympathetic nervous system and the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. Subsequent release of the antidiuretic hormone overrides normal homeostatic mechanisms and leads to further sodium and water retention. Even in the absence of renal impairment, the relationship between fluid input and natriuresis is weak, and the administration of intravenous fluid may lead to salt and water accumulation rather than a diuresis,3, 6, 7 effects that are exaggerated with 0.9% saline when compared with balanced crystalloids, which bear a closer resemblance to the constituents of plasma (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Rationale for fluid resuscitation to prevent acute kidney injury. .

Table 1. Composition of 0.9% saline and some commonly used balanced crystalloids.

| Human plasma | 0.9% Sodium chloride | Hartmann's | Ringer's lactate | Ringer's acetate | Plasma-Lyte 148 | Plasma-Lyte A pH 7.4 | Sterofundin/Ringerfundin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osmolarity (mOsm/l) | 275–295 | 308 | 278 | 273 | 276 | 295 | 295 | 309 |

| pH | 7.35–7.45 | 4.5–7.0 | 5.0–7.0 | 6.0–7.5 | 6.0–8.0 | 4.0–8.0 | 7.4 | 5.1–5.9 |

| Sodium (mmol/l) | 135–145 | 154 | 131 | 130 | 130 | 140 | 140 | 145 |

| Chloride (mmol/l) | 94–111 | 154 | 111 | 109 | 112 | 98 | 98 | 127 |

| Potassium (mmol/l) | 3.5–5.3 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Calcium (mmol/l) | 2.2–2.6 | 0 | 2 | 1.4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 |

| Magnesium (mmol/l) | 0.8–1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/l) | 24–32 | |||||||

| Acetate (mmol/l) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 24 |

| Lactate (mmol/l) | 1–2 | 0 | 29 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gluconate (mmol/l) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 23 | 0 |

| Maleate (mmol/l) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Na:Cl ratio | 1.21:1 to 1.54:1 | 1:1 | 1.18:1 | 1.19:1 | 1.16:1 | 1.43:1 | 1.43:1 | 1.14:1 |

HOW DID 0.9% SALINE COME INTO BEING?

Although traditionally believed to have originated during the European cholera pandemic in 1831, none of the intravenous saline solutions described between 1832 and 1895 bore any resemblance to 0.9% saline.8 The first reference to a solution bearing similarity to 0.9% saline appeared in an 1896 article by Lazarus-Barlow, where Hamburger, a Dutch physiological chemist, was cited as the main authority for suggesting that a concentration of 0.92% saline was ‘normal' for mammalian blood.9 Hamburger performed experiments on the effects of varying the concentration of salt solutions on erythrocyte fragility.10 He found that ‘for every salt a concentration could be obtained in which the least resistant blood corpuscles lost their coloring matter' and speculated that ‘the salt solutions used caused a swelling which a number of the blood corpuscles could not withstand without losing their coloring matter'. It was accepted that the freezing point of human serum was −0.52 °C. On the basis of his experiments on erythrocyte fragility and freezing points of mammalian serum, Hamburger concluded that ‘the blood of the majority of warm-blooded animals, including man, was isotonic with a NaCl solution of 0.9 per cent., and not of 0.6 per cent., as was generally thought...and which had always been called the physiological NaCl solution'.11 The scientific evidence supporting the use of 0.9% saline in clinical practice seems to have originated solely on these in vitro studies, and, given the evidence presented below, it is unlikely that 0.9% saline would had progressed beyond a phase I clinical trial had it been developed in recent times.

ANIMAL STUDIES

As early as 1948, a fall in arterial pH from 7.55 to 7.21 was demonstrated in dogs after an infusion of 1.5 liter of 0.9% saline (300 ml/h), but not after that of a ‘balanced salt solution' containing NaHCO3.12 In a canine model of Escherichia coli endotoxin–induced septic shock, mean saline requirement to maintain mean arterial pressure >80 mm Hg was 1833 ml over 3 h.13 The pH decreased from 7.32 to 7.11 (P<0.01) and serum chloride increased (from 128 to 137 mmol/l, P=0.016), without changes in pCO2, serum lactate, and sodium. In a study on anesthetized dogs that had one kidney auto-transplanted to the neck, thereby denervating it, infusion of chloride-containing solutions resulted in hyperchloremia that produced progressive concentration-dependent renal vasoconstriction and a decrease in GFR independent of renal innervation.14

Three swine studies have compared the effects of resuscitation using 0.9% saline and Ringer's lactate (RL) after 30 min of uncontrolled hemorrhage.15, 16, 17 Compared with RL, resuscitation with 0.9% saline required significantly greater volumes (256±145 ml/kg saline vs. 126±67 ml/kg RL, P=0.04) to attain pre-injury mean arterial pressure.17 Hyperchloremic acidosis and dilutional coagulopathy were noted with saline.17 Hypercoagulability and low blood loss were noted with RL.15 Extravascular lung water index increased with both fluids, but this occurred earlier and to a greater degree after saline.16 Another study examined the effects of resuscitation using four crystalloids (0.9% saline, RL, Plasmalyte-A (Pl-A), and Plasmalyte-R (Pl-R)) in a model of rapid hemorrhage in 116 unanesthetized pigs.18 Aortic blood (54 ml/kg) was removed over a period of 15 min, and the replaced volume was 14% in 5 min with saline, 100% in 20 min with saline, and 300% in 30 min with saline, RL, Pl-A, or Pl-R. In animals that had 300% replacement of shed blood in 30 min, RL provided the best survival rate of 67% (e.g., 50% for saline, 40% for Pl-R, and 30% for Pl-A). The investigators hypothesized that the lower survival rates in animals that were resuscitated with Pl-R and Pl-A may have resulted from the acetate constituent, which may have had differential regional vasodilatory and vasoconstrictive effects in these animals.18 After removal of 40% of total blood volume in three equal aliquots at 30-min intervals, pigs received saline (mean volume infused: 2865 ml), RL (2774 ml), or Plasma-Lyte (2681 ml), in a blinded manner over 15 min, at a volume that was three times that of the blood removed.19 All three solutions attenuated hemorrhage-induced low cardiac output and anuria equally, but saline induced negative base excess and a significant hyperchloremia.19

A rat study compared the effects of resuscitation with saline and RL following moderate (mean 36% estimated blood volume) and massive hemorrhage (mean 218% estimated blood volume).20 The animals with moderate hemorrhage were bled to a MAP of 60 mm Hg for 2 h, then resuscitated with the appropriate crystalloid for 1 h. In these animals, resuscitation with saline and RL was equivalent. The final hematocrit, pH, and base excess were not different, and all animals survived. In the massive hemorrhage group, animals resuscitated with saline+blood were significantly more acidotic than animals resuscitated with equal volumes of RL+blood (pH 7.14 vs. 7.39, P<0.01) and had significantly worse survival (50 vs. 100%, P<0.05).20 Furthermore, some saline+blood-resuscitated animals developed profound acidosis associated with cardiorespiratory arrest in some cases and early death in others. Hyperchloremic acidosis also resulted in increased concentrations of circulating inflammatory mediators in an experimental model of severe sepsis in rats, with a dose-dependent increase in circulating interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-10 concentrations with increasing acidosis.21

In a sheep model of septic shock (intravenous administration of live E. coli), resuscitation with saline (20 ml/kg over 15 min), versus observation, resulted in transient reversal of the hemodynamic effects of septic shock but had no effect on renal blood flow.22 Interestingly, infusion of 25 ml/kg saline over 20 min in normovolemic conscious and anesthetized sheep altered fluid kinetics in the anesthetized group by reducing urinary excretion and resulting in interstitial fluid accumulation.23 A porcine model24 of elevated intra-abdominal pressure demonstrated a progressive decrease in renal venous and arterial blood flow with increasing intra-abdominal pressure. Development of renal interstitial edema has been hypothesized to contribute, at least in part, to development of a ‘renal compartment-syndrome'–type effect due to kidney parenchymal swelling within the tough unyielding capsule, contributing to onset of anuria/oliguria in acute tubular necrosis. In a study on the effects of renal decapsulation in 12 rhesus monkeys subjected to cross-clamping of the supra-renal aorta for periods of 15–55 min followed by declamping, split ureteral function tests demonstrated that renal decapsulation resulted in better preservation (threefold higher) of creatinine, urea, and free water clearance.25 Pathological examination revealed that kidneys with an intact capsule were either smaller than their decapsulated partners or obviously atrophic.25 Edema-related subcapsular pressure elevation was examined in a murine model of renal ischemia reperfusion.26 After 24 h of elevated subcapsular pressures, significant reductions were noted in tubular excretion rates and renal perfusion, coupled with severe tissue damage on histological examination. Surgical capsulotomy effectively prevented these functional and structural alterations.26

EFFECTS OF 0.9% SALINE ON ACID–BASE BALANCE

Large volume infusions (50 ml/kg over 1 h) of 0.9% saline in healthy volunteers have been shown to be associated with a persistent acidosis and delayed micturition, and to produce abdominal discomfort and pain, nausea, drowsiness, and decreased mental capacity to perform complex tasks, but these changes were not noted after infusion of identical volumes of Hartmann's solution.27 Slow excretion of saline after a 2-liter intravenous load, with only 29% having been excreted after 195 min, has also been reported.28 A further comparison of the effects of 2-liter infusions of 0.9% saline and Hartmann's solution over 1 h in healthy volunteers has confirmed the sluggish urinary response after saline infusion, which occurs at the expense of the production of a significant and sustained hyperchloremia.3 At 6 h, 56% of the infused saline was retained, in contrast to only 30% of the Hartmann's solution. Time to first micturition was quicker, and urine volumes and sodium excretion were greater after infusion with Hartmann's solution than after saline. Similar changes were also noted when 2-liter infusions of saline were compared with those of Plasma-Lyte 148.6 In addition, although calculated blood volume expansion was similar after the two infusions, interstitial fluid accumulation was significantly greater after saline than after Plasma-Lyte.6

The hyperchloremic acidosis caused by infusion of moderate-to-large quantities of 0.9% saline can last for several hours after the end of the infusion even in healthy volunteers3, 6, 7, 27, 29 and may reflect the lower [Na+]:[Cl−] ratio in saline (1:1) than in balanced crystalloids (1.18–1.43:1) or in plasma (1.38:1).30 Two theories have been proposed to explain this phenomenon: dilutional acidosis31, 32 and the Stewart hypothesis.33

It has been proposed that infusion of large volumes of saline causes a decrease in serum bicarbonate concentration due to a dilutional effect, resulting in acidosis.31, 32 The effects of randomly allocated 2-h infusions of almost 70 ml/kg (i.e., up to 5 liters) of 0.9% saline or Hartmann's solution were studied in patients undergoing elective gynecological operations.34 There was a significant decrease in pH (7.41–7.28), serum bicarbonate concentration (23.5–18.4 mmol/l), and anion gap (16.2–11.2 mmol/l), accompanied by an increase in serum chloride concentration (104–115 mmol/l) during the first 2 h of saline infusion. Although pH, bicarbonate, and chloride concentrations did not change significantly after Hartmann's solution, the anion gap decreased (15.2–12.1 mmol/l). The volume of fluid replacement in this study34 may be considered excessive, but it confirmed that hyperchloremic acidosis accompanied saline infusions in patients. In a study of 30 patients undergoing major surgery, randomly allocated to receive either 0.9% saline or Plasma-Lyte 148 at 15 ml/kg/h, those receiving saline had significantly increased chloride concentrations (Δ[Cl−] +6.9 vs. +0.6 mmol/l, P<0.01), decreased bicarbonate concentrations (Δ[HCO3−] −4.0 vs. −0.7 mmol/l, P<0.01), and increased base deficit (Δ base excess −5.0 vs. −1.2 mmol/l, P<0.01) compared with those receiving Plasma-Lyte 148.35 There were no significant changes in plasma sodium, potassium, or lactate concentrations in either group.35

However, in healthy volunteers, the fall in serum bicarbonate concentration after saline infusions is in the range of 1–2 mmol/l (refs. 3, 6, 7, 27, 29) and this, on its own, does not explain development of acidosis on the basis of the Henderson-Hesselbach equation. Crystalloid infusions are also associated with a decrease in serum albumin concentration, even in healthy subjects.3, 6, 7, 27, 29, 34 The negatively charged albumin molecule accounts for about 75% of the anion gap36 and acute dilutional hypoalbuminemia can effectively reduce the upper limit of the normal range for the anion gap.32 In critically ill patients, the anion gap has been shown to reduce by 2.5 mmol/l for every 10 g/l decrease in serum albumin concentration.37 However, once again, development of acidosis cannot be explained entirely as albumin concentrations fall even after the infusion of balanced crystalloids or 5% dextrose.3, 6, 7, 27, 29, 34

Hence, the mechanism of acidosis after infusions of 0.9% saline may be better explained by the Stewart hypothesis.33 This describes a mathematical approach to acid–base balance based on the apparent strong ion difference (SIDa, [Na+]+[K+]—[Cl−]) being the major determinant of H+ ion concentration. A decrease in SIDa is associated with metabolic acidosis and an increase with metabolic alkalosis. Hyperchloremia consequent on saline infusions decreases the SIDa, and is the process that results in a metabolic acidosis.32, 34, 38, 39 Canine experiments on resuscitation from septic shock have shown that 0.9% saline accounted for 42% of the acidosis observed, whereas lactate was responsible for only 10%.13

EFFECTS OF SALINE EXCESS AND HYPERCHLOREMIA ON THE KIDNEY

Healthy human volunteer studies have shown that retention of fluid in the interstitial space is greater after infusions of 0.9% saline, than after those of balanced crystalloids or 5% dextrose, and that this fluid retention is associated with reduced urine volume. Drummer et al.40 studied the urinary excretion of water and electrolytes and the changes in hormones controlling body fluid homeostasis during the 48 h following an infusion of 2 liters of 0.9% saline over 25 min and after a 48 h control experiment. Urine volume and electrolyte excretion rates were significantly increased in the 2 days following saline infusion, with the largest increase being observed between 3 and 22 h post infusion. The authors suggested that the antidiuretic hormone, natriuretic peptide, and catecholamines were unlikely to be of major importance for the renal response to this hypervolemic stimulus. The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system was suppressed during the 2 days post infusion, which correlated with the effects of saline load on sodium excretion. However, the closest relation with Na excretion was observed for the kidney-derived member of the atrial natriuretic peptide family, urodilatin, which was considerably increased during the long-term period up to 22 h post infusion.40 Thus, these data show that humans require approximately 2 days to restore normal sodium and water balance after an acute saline infusion and that urodilatin and the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system may participate in the long-term renal response to such infusions. A more recent study has also suggested that the excretion of salt and water after saline infusions is dependent on a slow and sustained suppression of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system rather than differential responses to the antidiuretic hormone or natriuretic peptides.7

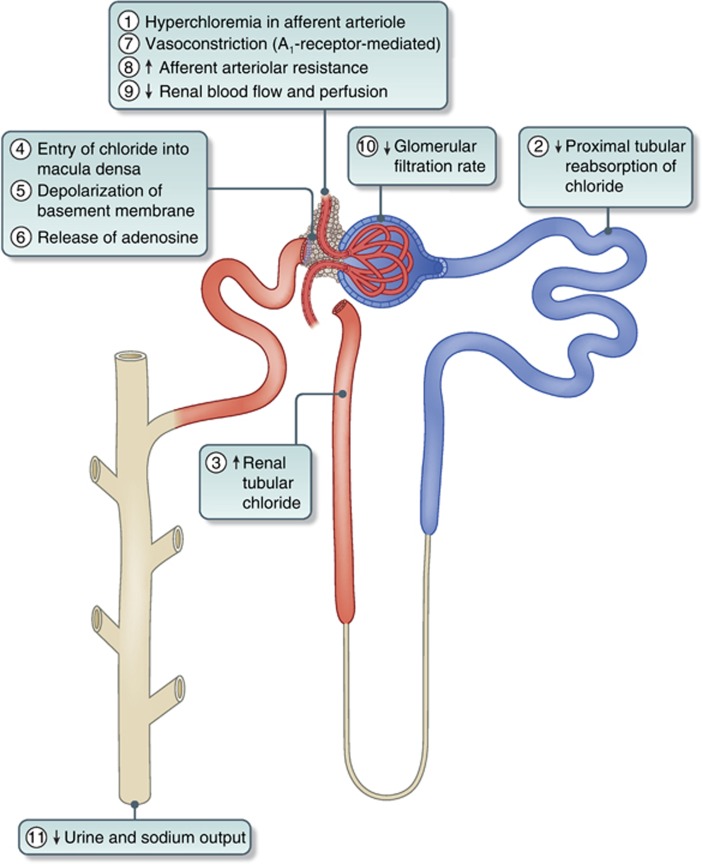

The greater diuresis of water after infusion with Hartmann's solution compared with 0.9% saline may be partly explained by its lower osmolality and the reduced antidiuretic hormone secretion that this may have engendered.3, 27 However, these differences between balanced crystalloids are maintained even when isotonic crystalloids such as Plasma-Lyte 148 are used.6 Veech30 had emphasized previously that, when large amounts of saline are infused, the kidney is slow to excrete the excess chloride load. He also suggested that, as the permeability of the chloride ion across cell membranes was voltage dependent, the intracellular chloride content was a direct function of membrane potential. In animal studies, sustained renal vasoconstriction was specifically related to hyperchloremia, which was potentiated by previous salt depletion and related to the tubular reabsorption of chloride,14 which appeared to be initiated by an intrarenal mechanism independent of the nervous system and was accompanied by a decrease in GFR. Although changes in renal blood flow and GFR were independent of changes in the fractional reabsorption of sodium, they correlated closely with changes in the fractional reabsorption of chloride, suggesting that renal vascular resistance was related to the delivery of chloride, but not sodium, to the loop of Henle.14 Chloride-induced vasoconstriction appeared to be specific for the renal vessels and the regulation of renal blood flow and GFR by chloride could override the effects of hyperosmolality on the renal circulation.14 Other animal experiments have shown that K+-induced reduction in renal vessel diameter was both dependent on and responsive to increasing extracellular chloride.41, 42 Moreover, at pathologically elevated concentrations, chloride led to severe renal vasoconstriction.41 It has also been shown in an experimental rat model of salt-sensitive hypertension that, although loading with sodium chloride produced hypertension, that with sodium bicarbonate did not.43 Studies on young adult men have shown that plasma renin activity was suppressed 30 and 60 min after infusion of sodium chloride, but not after infusion of sodium bicarbonate, suggesting that both the renin and blood pressure responses to sodium chloride are dependent on chloride.43 A recent healthy volunteer study using magnetic resonance imaging has shown, for the first time in humans, that acute infusions of 2 liters of 0.9% saline can cause a reduction in renal artery flow velocity and renal cortical tissue perfusion when compared with a balanced crystalloid, and that this may be associated with the hyperchloremia caused by saline.6 The role of the macula densa in providing tubulo-glomerular feedback to afferent vessels and the signaling pathway leading to changes in GFR has been elucidated recently.44, 45 Increased renal tubular chloride concentration can result in the entry of chloride into cells of the macula densa causing depolarization of the basolateral membrane via chloride channels.46 This can lead to adenosine release from the macula densa, which through its effects on the A1 receptor causes afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction47 and provides the signal for increased afferent arteriolar resistance and reduced GFR, leading to reduced urine volume and sodium excretion (Figure 2).44, 45

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the sequential effects of hyperchloremia on the kidney. Numbers indicate the sequence of events. A1-receptor, adenosine1-receptor.

Saline infusions have been shown to cause a greater increase in interstitial fluid volume (and, hence, edema) than balanced crystalloids and this may lead to a relatively greater increase in renal volume.6 Even small increases in the volume of an organ enclosed by a relatively non-expansible capsule may lead to intracapsular hypertension, which may further compromise tissue perfusion, reduce microvascular blood flow, and impair organ function.25 Increase in renal intracapsular pressure may decrease the pressure gradient across the renal arterioles and, in keeping with Poiseuille's law, may have an additional impact on decreasing flow velocity.6 Improvement in renal function and increased urine output have been demonstrated in kidneys subjected to capsulotomy following massive preoperative volume replacement with blood and crystalloids in hypovolemic monkeys.25

Furthermore, just as the increased interstitial fluid overload caused by large volumes of saline infusions can result in peripheral edema, it may also cause splanchnic edema, intestinal stretch increased abdominal pressure, ascites,48 and even the abdominal compartment syndrome,49 which can further compromise renal and gastrointestinal function.50, 51, 52, 53, 54

CLINICAL STUDIES IN SURGICAL OR CRITICALLY ILL PATIENTS

Although human studies3, 6, 7, 27, 29, 30, 34, 55, 56, 57, 58 have confirmed that 0.9% saline infusions lead to a hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, which causes detriment to renal function, until recently there was no firm evidence that the use of saline led to adverse patient outcomes. In a relatively recent review the authors commented, ‘…there appear to be some side-effects associated with saline use, but to date these have not translated into clinically important outcomes, though this may be through lack of data'.59

A review of the literature, however, fails to reveal a single clinical study showing 0.9% saline to be superior to balanced crystalloids. Nevertheless, the absence of studies demonstrating better clinical outcomes with balanced crystalloids until relatively recently has led to the continued use of 0.9% saline in most areas of practice. Studies in the perioperative34, 35 and resuscitation60 settings have shown that 0.9% saline causes a hyperchloremic acidosis when compared with balanced crystalloids. These studies were on relatively small numbers of patients and, although they did not demonstrate a difference in clinical outcome between the groups, they suggested that the temporary hyperchloremic acidosis produced by the use of 0.9% saline could be given a false pathological significance and that it could also exacerbate an acidosis resulting from a definite pathological state. Happily, over the past few years a few studies have suggested that 0.9% saline leads to more adverse events than balanced crystalloids, and, hence, worse patient outcomes.

There are two randomized controlled double-blind trials (n=66 (ref. 61) and n=51 (ref. 62)) comparing 0.9% saline with RL in the perioperative period, with both showing that the use of 0.9% saline resulted in more adverse events compared with RL. In patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, those receiving saline needed significantly greater volumes of packed red blood cells (780 vs. 560 ml), platelets (392 vs. 223 ml), and bicarbonate therapy (30 vs. 4 ml) than those receiving RL.61 Although median blood loss was 600 ml greater in the saline group, this difference was not significant. Hyperchloremic acidosis was demonstrable in the saline group, but this did not result in an apparent difference in outcome other than the need for larger amounts of bicarbonate to correct base deficit and the use of greater volumes of blood products.61 A study on patients undergoing renal transplantation had to be stopped prematurely because, compared with none in those receiving RL, 19% of patients in the saline group had to be treated for hyperkalemia and 31% for metabolic acidosis. Being a double-blind study, the data monitoring committee thought that the hyperkalemia occurred in the RL group.62 Although there was no statistically significant difference in postoperative renal function when the two groups were compared, patients who received saline tended to have a lower 4 h postoperative urine output (1.6 vs. 2.1 l) and 24 h creatinine clearance (84 vs. 94 ml/min) than those receiving RL.62 Another recent double-blind study randomized adult trauma patients requiring blood transfusion, intubation, or operation within 60 min of arrival to receive either 0.9% saline or Plasma-Lyte A for resuscitation during the first 24 h after injury.60 Of the 65 patients randomized, 46 were evaluable and the authors showed that the improvement in base excess from 0 to 24 h was significantly greater with Plasma-Lyte A than with 0.9% saline (mean difference (95% confidence interval (CI)): 3.1 (0.5 to to 5.6) mmol/l). At 24 h, arterial pH was greater (0.05 (0.01 to 0.09)) and serum chloride concentration was lower (−7 (−10 to −3) mmol/l) with Plasma-Lyte A than with 0.9% saline. However, there was no significant difference between groups when volumes of fluid administered, 24 h urine output, resource utilization, and clinical outcomes were compared. As these studies60, 61, 62 were performed on relatively small groups of patients, it is quite possible that the lack of difference in clinical outcome measures, such as postoperative complications or length of hospital stay, between the two groups may represent a type II error.

In a double-blind study aimed at quantifying changes in acid–base balance, potassium and lactate concentrations after administration of different crystalloids during kidney transplantation, 90 patients were randomized to three groups to receive 0.9% saline, RL, or Plasma-Lyte at 20–30 ml/kg/h.63 There was a significant decrease in pH and base excess, and a significant increase in serum chloride concentration in patients receiving saline but not the balanced crystalloids during surgery. Lactate concentrations increased significantly in patients who received RL, but not after Plasma-Lyte. Clinical outcomes were not reported, but there were no significant differences between groups in postoperative renal function tests or the need for hemodialysis.63 Other clinical studies have also shown similar changes in pH, acid-base status, and serum chloride concentrations without differences in clinical outcome when 0.9% saline was compared with balanced crystalloids in the perioperative setting.64, 65, 66, 67

Recent large observational studies68, 69, 70, 71 have suggested that the high chloride content of 0.9% saline may cause adverse events, especially when renal outcomes are considered. Evaluation of outcomes in a propensity-matched study of 2788 adults undergoing major open abdominal surgery who received only 0.9% saline and in 926 patients who received only a balanced crystalloid on the day of surgery, recorded in a validated and quality-assured database, showed that unadjusted in-hospital mortality (5.6 vs. 2.9%) and the percentage of patients developing complications (33.7 vs. 23%) were significantly greater (P<0.01) in those receiving 0.9% saline than in those receiving the balanced crystalloid.69 Although mortality in the saline group remained higher after correction for confounding variables, the difference ceased to be significant. Patients in the 0.9% saline group received an average of 316 ml more fluid (P<0.001), had a greater need for blood transfusion (odds ratio (95% CI): 11.5 (10.3 to 12.7) vs. 1.8 (1.2 to 2.9)%, P<0.001) and more infectious complications (P<0.001), and were 4.8 times more likely to require dialysis (P<0.001) than those in the balanced crystalloid group. Overall complications were fewer in the balanced crystalloid group (odds ratio (95% CI): 0.79 (0.66 to 0.97)).

Further support for chloride-restrictive fluid strategies in critically ill patients is provided by a recent open-label prospective sequential study, in which patients consecutively admitted to intensive care (30% after elective surgery) received either traditional chloride-rich (0.9% sodium chloride, 4% succinylated gelatin solution, or 4% albumin solution, n=760) or chloride-restricted regimens (Hartmann's solution, Plasma-Lyte 148, or chloride-poor 20% albumin, n=773).70 After adjusting for confounding variables, patients in the chloride-restricted group had a decreased incidence of acute kidney injury (odds ratio (95% CI): 0.52 (0.37 to 0.75), P<0.001) and the use of renal replacement therapy (odds ratio (95% CI) 0.52 (0.33 to 0.81), P=0.004). However, there were no differences in hospital mortality, or in the length of hospital or intensive care unit stay.70 In an earlier study using a similar design, the same group of authors71 showed that, after introduction of a low-chloride regimen (n=816), the incidence of severe metabolic acidosis decreased from 9.1 to 6.0% (P<0.001) and that of severe acidemia from 6.0 to 4.9% (P<0.001) when compared with a high-chloride regimen (n=828). However, the intervention also led to a significantly greater incidence of severe metabolic alkalosis and alkalemia with an increase from 25.4 to 32.8% and 10.5 to 14.7%, respectively (P<0.001). The time-weighted mean chloride concentration decreased from 104.9 to 102.5 mmol/l (P<0.001), whereas the standard base excess increased from 0.5 to 1.8 mmol/l (P<0.001), and mean pH from 7.40 to 7.42 (P<0.001). Clinical outcomes were, however, not reported in this study.

A study on 22,851 surgical patients with normal preoperative serum chloride concentration and renal function demonstrated a 22% incidence of acute postoperative hyperchloremia (serum chloride >110 mmol/l).68 Of the 4955 patients with hyperchloremia after surgery, 4266 (85%) patients were propensity matched with an equal number of patients who had normochloremia postoperatively. Patients with hyperchloremia were at increased risk of 30-day postoperative mortality (3.0 vs. 1.9% odds ratio (95% CI): 1.58 (1.25 to 1.98)) and had a longer median hospital stay (7.0 days (interquartile range 4.1–12.3) vs. 6.3 days (interquartile range 4.0–11.3), P<0.01) than those with normal postoperative serum chloride concentrations.68 Patients with postoperative hyperchloremia were also more likely to have postoperative renal dysfunction as defined by a >25% decrease in GFR (12.9 vs. 9.2%, P<0.01). Contrary to what was previously believed,32, 59 this study68 has shown that hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is not a benign, self-limiting, metabolic disturbance.

BALANCED CRYSTALLOIDS AND SERUM POTASSIUM CONCENTRATION

As balanced crystalloids contain potassium, they were traditionally considered to be contraindicated in the presence of hyperkalemia or situations with a potential for hyperkalemia, such as diabetic ketoacidosis or rhabdomyolysis. However, the maximum concentration of potassium in balanced crystalloids is 5 mmol/l, which gets rapidly diluted in extracellular fluid after infusion. This is unlikely to cause an appreciable increase in serum potassium concentrations and four recent small-scale studies have reinforced this view.72, 73, 74, 75

A single-blind study randomized patients with rhabdomyolysis (creatinine kinase >1000 IU/l) secondary to doxylamine intoxication to receive infusions of either 0.9% saline (n=15) or RL (n=13) at rates of 400 ml/h.72 Median urinary (4.25 vs. 5.5) and serum pH (7.44 vs. 7.36) were significantly higher in the RL group than in patients who received saline. There were no significant differences in serum potassium concentrations, but patients in the saline group had higher serum sodium and chloride concentrations. Median time to creatinine kinase normalization (<200 IU/l) was 96 h in the RL group compared with 120 h in the saline group, and it was found that patients in the RL group did not develop metabolic acidosis and needed little supplemental sodium bicarbonate.72

A small retrospective study on patients with diabetic ketoacidosis examined differences between those who received exclusively 0.9% saline (n=14) or Plasma-Lyte 148 (n=9) for the initial 12 h of resuscitation.73 Median serum bicarbonate concentrations were higher (P<0.05) in the Plasma-Lyte group at 4–6 h (8.4 vs. 1.7 mmol/l) and 6–12 h (12.8 vs. 6.2 mmol/l) and these were associated with a faster resolution of metabolic acidosis. Interestingly, at 6–12 h from baseline, serum potassium concentration was significantly lower in the Plasma-Lyte group (3.9 (3.4–4.0) mmol/l) than the saline group (4.3 (4.1–4.8) mmol/l, P<0.05). The Plasma-Lyte group also had higher mean arterial blood pressure at 2–4 h, higher cumulative urine output, and lower serum chloride concentrations at 24 h. There were no differences in glycemic control or duration of intensive care unit stay between the two groups.73 A double-blind study that randomized patients with diabetic ketoacidosis to receive either 0.9% saline (n=29) or RL (n=28) similarly failed to demonstrate differences in serum potassium concentration between the two groups at 10 h from baseline.75

Similar findings were noted in studies that examined the effects of different infusions in treating dehydration76, 77 and acute pancreatitis.78 A double-blind study randomized 90 consecutive moderate-to-severely dehydrated adults to receive 0.9% saline, RL, or Plasma-Lyte at 20 ml/kg/h for 2 h.77 At the end of the study infusions, serum bicarbonate concentrations decreased leading to a tendency to lower pH values in the saline group. No significant changes were noted in potassium, sodium, or chloride concentrations.77 An observational study of 40 dehydrated patients with choleriform diarrhea examined the effects of treatment with 50 ml/kg/h of either RL or 0.9% saline.76 RL led to quicker resolution of acidosis, whereas the hyperosmolar and hypernatremic states were corrected with both solutions. Although the saline group had lower serum potassium concentrations at baseline, there were no significant differences in potassium concentrations at 2 and 14 h following infusion of the study fluids.76 Finally, a randomized study examined goal-directed (n=19) versus standard (n=21) fluid resuscitation in 40 patients with acute pancreatitis.78 Patients, randomized to either 0.9% saline or RL, received an initial bolus of 20 ml/kg over 30 min for resuscitation followed by a 3 ml/kg/h infusion for maintenance. There were no differences in total fluid volumes used (∼4.5 liters in 24 h). Infusion of RL was associated with significant reductions in systemic inflammatory response after 24 h (84 vs. 0% reduction in saline group, P=0.035) and reduced CRP concentrations (51.5 vs. 104 mg/dl, P=0.02). Although the aforementioned study78 did not report peri-infusion serum potassium concentrations, there were no reported adverse events of hyperkalemia.

CONCLUSIONS

This comprehensive review of literature has shown that 0.9% saline is neither ‘normal' nor ‘physiological' and that its high chloride content leads to many pathophysiological changes, especially with regard to renal function, in both animals and healthy human volunteers. These changes are not seen after infusions with balanced crystalloids. Small randomized clinical trials have shown that the hyperchloremic acidosis induced by saline is also seen in patients, but this did not translate into being a detriment to clinical outcomes when compared with balanced crystalloids, perhaps because of a type II error. Other small studies have shown that it may be safe to use potassium-containing balanced crystalloids in situations where hyperkalemia may be expected. However, it must be remembered that in this situation the evidence is not strong enough and larger studies are required before general recommendations for the use of balanced crystalloids in the presence of hyperkalemia can be made.

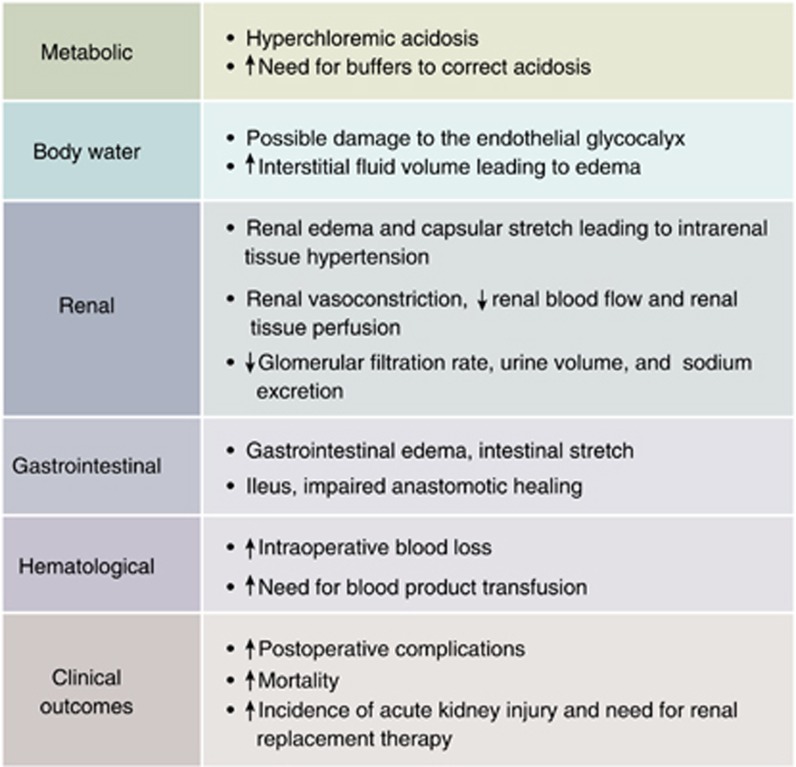

A strong signal is emerging from recent large propensity-matched and cohort studies for the adverse effects that large volumes of 0.9% saline have on clinical outcome in surgical and in critically ill patients when compared with balanced crystalloids. The major adverse events are the increased incidence of acute kidney injury and the need for renal replacement therapy caused by 0.9% saline and the resultant hyperchloremia. There is also an increase in other side effects and resource utilization (Figure 3), and pathological hyperchloremia has been associated with increased postoperative mortality. However, as there are no large-scale randomized trials yet comparing 0.9% saline with balanced crystalloids, the current evidence cannot be regarded as Grade A.

Figure 3.

Adverse events related to intravenous therapy with 0.9% saline when compared with balanced crystalloids. The evidence has been collected from animal studies, healthy volunteer studies, small randomized clinical trials, and large patient cohort studies, and cannot be presently regarded as Grade A.

It must also be remembered that some balanced crystalloids such as Hartmann's solution and RL are hypo-osmolar and may not be suitable for neurosurgical patients and those with head injuries because of their propensity to cause brain edema. This effect may not be seen with isotonic balanced crystalloids such as Plasma-Lyte 148 and Sterofundin, but as yet there is no evidence to support this. Balanced crystalloids are not suitable for the resuscitation of patients with alkalosis and hypochloremia (e.g., profound vomiting) and in this situation 0.9% saline may be the solution of choice. The newer balanced crystalloids contain anions, such as gluconate, acetate, and malate, and the physiological effects and potential adverse effects of these substances have not yet been fully elucidated, and it must be remembered that the ‘perfect' crystalloid does not exist.

Nevertheless, on the basis of current literature there is adequate evidence to suggest that balanced crystalloids are more physiological than 0.9% saline and cause less detriment to renal function, with perhaps better clinical outcome. Hence, we submit that we have presented a coherent argument to recommend that chloride-rich crystalloids such as 0.9% saline should be replaced with balanced crystalloids as the mainstays of fluid resuscitation to prevent ‘pre-renal' acute kidney injury.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emmanouil Psaltis, MBBS, for drawing Figure 2.

DNL has received unrestricted research funding, travel grants, and speaker's honoraria from Baxter Healthcare, Fresenius Kabi, and BBraun. SA has received unrestricted research funding and travel grants from Fresenius Kabi.

References

- Evans GH. The abuse of normal salt solution. JAMA. 1911;57:2126–2127. [Google Scholar]

- Wakim KG. ‘‘Normal'' 0.9 per cent salt solution is neither ‘‘normal'' nor physiological. JAMA. 1970;214:1710. doi: 10.1001/jama.214.9.1710b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid F, Lobo DN, Williams RN, et al. (Ab)normal saline and physiological Hartmann's solution: a randomized double-blind crossover study. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:17–24. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prowle JR, Bellomo R. Fluid administration and the kidney. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16:332–336. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32833be90b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo DN. Sir David Cuthbertson medal lecture. Fluid, electrolytes and nutrition: physiological and clinical aspects. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63:453–466. doi: 10.1079/pns2004376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury AH, Cox EF, Francis ST, et al. A randomized, controlled, double-blind crossover study on the effects of 2-L infusions of 0.9% saline and plasma-lyte(R) 148 on renal blood flow velocity and renal cortical tissue perfusion in healthy volunteers. Ann Surg. 2012;256:18–24. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318256be72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo DN, Stanga Z, Aloysius MM, et al. Effect of volume loading with 1 liter intravenous infusions of 0.9% saline, 4% succinylated gelatine (Gelofusine) and 6% hydroxyethyl starch (Voluven) on blood volume and endocrine responses: a randomized, three-way crossover study in healthy volunteers. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:464–470. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181bc80f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad S, Allison SP, Lobo DN. The history of 0.9% saline. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus-Barlow WS. On the initial rate of osmosis of blood-serum with reference to the composition of ‘‘physiological saline solution'' in mammals. J Physiol. 1896;20:145–157. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1896.sp000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger HJ.Koninkl. Akad. v. Wetensch. te Amsterdam 29/12/1883. Amsterdam, 1883..

- Hamburger HJ. A discourse on permeability in physiology and pathology. Lancet. 1921;198:1039–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Shires GT, Holman J. Dilution acidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1948;28:557–559. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-28-3-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Kramer DJ, et al. Etiology of metabolic acidosis during saline resuscitation in endotoxemia. Shock. 1998;9:364–368. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199805000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox CS. Regulation of renal blood flow by plasma chloride. J Clin Invest. 1983;71:726–735. doi: 10.1172/JCI110820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly LN, Differding JA, Enomoto TM, et al. Resuscitation with normal saline (NS) vs. lactated Ringers (LR) modulates hypercoagulability and leads to increased blood loss in an uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock swine model. J Trauma. 2006;61:57–64. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000220373.29743.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CR, Vinecore K, Hagg DS, et al. Resuscitation of haemorrhagic shock with normal saline vs. lactated Ringer's: effects on oxygenation, extravascular lung water and haemodynamics. Crit Care. 2009;13:R30. doi: 10.1186/cc7736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd SR, Malinoski D, Muller PJ, et al. Lactated Ringer's is superior to normal saline in the resuscitation of uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2007;62:636–639. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802ee521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traverso LW, Lee WP, Langford MJ. Fluid resuscitation after an otherwise fatal hemorrhage: I. Crystalloid solutions. J Trauma. 1986;26:168–175. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198602000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noritomi DT, Pereira AJ, Bugano DD, et al. Impact of Plasma-Lyte pH 7.4 on acid-base status and hemodynamics in a model of controlled hemorrhagic shock. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:1969–1974. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011001100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey MA, Davis RE, Liu FC, et al. Lactated Ringer's is superior to normal saline in a model of massive hemorrhage and resuscitation. J Trauma. 1998;45:894–899. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199811000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum JA, Song M, Almasri E. Hyperchloremic acidosis increases circulating inflammatory molecules in experimental sepsis. Chest. 2006;130:962–967. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L, Bellomo R, May CN. The effect of normal saline resuscitation on vital organ blood flow in septic sheep. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1238–1242. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer KI, Svensen C, Hahn RG, et al. Volume kinetic analysis of the distribution of 0.9% saline in conscious versus isoflurane-anesthetized sheep. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:442–449. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200202000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wauters J, Claus P, Brosens N, et al. Pathophysiology of renal hemodynamics and renal cortical microcirculation in a porcine model of elevated intra-abdominal pressure. J Trauma. 2009;66:713–719. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817c5594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone HH, Fulenwider JT. Renal decapsulation in the prevention of post-ischemic oliguria. Ann Surg. 1977;186:343–355. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197709000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrler T, Tischer A, Meyer A, et al. The intrinsic renal compartment syndrome: new perspectives in kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;89:40–46. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181c40aba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EL, Hildebrand KL, McCormick SA, et al. The effect of intravenous lactated Ringer's solution versus 0.9% sodium chloride solution on serum osmolality in human volunteers. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:999–1003. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199905000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer DRJ, Shore AC, Markandu ND, et al. Dissociation between plasma atrial-natriuretic-peptide levels and urinary sodium-excretion after intravenous saline infusion in normal man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1987;73:285–289. doi: 10.1042/cs0730285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo DN, Stanga Z, Simpson JAD, et al. Dilution and redistribution effects of rapid 2-litre infusions of 0.9% (w/v) saline and 5% (w/v) dextrose on haematological parameters and serum biochemistry in normal subjects: a double-blind crossover study. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;101:173–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veech RL. The toxic impact of parenteral solutions on the metabolism of cells: a hypothesis for physiological parenteral therapy. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;44:519–551. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/44.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkin DA, Raja RM, Saven A. Dilutional acidosis. South Med J. 1990;83:354–355. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199003000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prough DS, Bidani A. Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is a predictable consequence of intraoperative infusion of 0.9% saline. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1247–1249. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart PA. Modern quantitative acid-base chemistry. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1983;61:1444–1461. doi: 10.1139/y83-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheingraber S, Rehm M, Sehmisch C, et al. Rapid saline infusion produces hyperchloremic acidosis in patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1265–1270. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199905000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane C, Lee A. A comparison of Plasmalyte 148 and 0.9% saline for intra-operative fluid replacement. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:779–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1994.tb04450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh MS, Carroll HJ. The anion gap. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:814–817. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197710132971507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, et al. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1807–1810. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LR, Waters JH, Provost C. Mechanism of hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:482–483. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199602000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorje P, Adhikary G, McLaren ID, et al. Dilutional acidosis or altered strong ion difference. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1011–1012. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummer C, Gerzer R, Heer M, et al. Effects of an acute saline infusion on fluid and electrolyte metabolism in humans. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:F744–F754. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.5.F744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen PB, Jensen BL, Skott O. Chloride regulates afferent arteriolar contraction in response to depolarization. Hypertension. 1998;32:1066–1070. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.6.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen BL, Ellekvist P, Skott O. Chloride is essential for contraction of afferent arterioles after agonists and potassium. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F389–F396. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.3.F389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchen TA, Luke RG, Ott CE, et al. Effect of chloride on renin and blood pressure responses to sodium chloride. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:817–822. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-5-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell PD, Komlosi P, Zhang ZR. ATP as a mediator of macula densa cell signalling. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5:461–471. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9148-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Garvin JL, Liu R, et al. Role of macula densa adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in tubuloglomerular feedback. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1479–1485. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell PD, Lapointe JY, Cardinal J. Direct measurement of basolateral membrane potentials from cells of the macula densa. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:F463–F468. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.3.F463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch WJ. Adenosine A1 receptor antagonists in the kidney: effects in fluid-retaining disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:165–170. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry JC, Welker KJ, Goldman RK, et al. Mechanism of acute ascites formation after trauma resuscitation. Arch Surg. 2003;138:773–776. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.7.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balogh Z, McKinley BA, Cocanour CS, et al. Supranormal trauma resuscitation causes more cases of abdominal compartment syndrome. Arch Surg. 2003;138:637–642. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnuriger B, Inaba K, Wu T, et al. Crystalloids after primary colon resection and anastomosis at initial trauma laparotomy: excessive volumes are associated with anastomotic leakage. J Trauma. 2011;70:603–610. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182092abb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury AH, Lobo DN. Fluids and gastrointestinal function. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14:469–476. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328348c084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SK, Fogle LN, Aroom KR, et al. Hydrostatic intestinal edema induced signaling pathways: potential role of mechanical forces. Surgery. 2010;147:772–779. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SK, Uray KS, Stewart RH, et al. Resuscitation-induced intestinal edema and related dysfunction: state of the science. J Surg Res. 2011;166:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uray KS, Shah SK, Radhakrishnan RS, et al. Sodium hydrogen exchanger as a mediator of hydrostatic edema-induced intestinal contractile dysfunction. Surgery. 2011;149:114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AM, Karmakar MK, Contardi LH, et al. Excessive use of normal saline in managing traumatized patients in shock: a preventable contributor to acidosis. J Trauma. 2001;51:173–177. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200107000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes NJ, Woolf R, Mutch M, et al. The effects of balanced versus saline-based hetastarch and crystalloid solutions on acid-base and electrolyte status and gastric mucosal perfusion in elderly surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:811–816. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200110000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton BA, Guy JS, Morris JA, Jr., et al. The cellular, metabolic, and systemic consequences of aggressive fluid resuscitation strategies. Shock. 2006;26:115–121. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000209564.84822.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidet B, Soni N, Della Rocca G, et al. A balanced view of balanced solutions. Crit Care. 2010;14:325. doi: 10.1186/cc9230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handy JM, Soni N. Physiological effects of hyperchloraemia and acidosis. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:141–150. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JB, Utter GH, Schermer CR, et al. Saline versus Plasma-Lyte A in initial resuscitation of trauma patients: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2014;259:255–262. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318295feba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters JH, Gottlieb A, Schoenwald P, et al. Normal saline versus lactated Ringer's solution for intraoperative fluid management in patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: an outcome study. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:817–822. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley CM, Frumento RJ, Hardy MA, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of lactated Ringer's solution and 0.9% NaCl during renal transplantation. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:1518–1524. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000150939.28904.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadimioglu N, Saadawy I, Saglam T, et al. The effect of different crystalloid solutions on acid-base balance and early kidney function after kidney transplantation. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:264–269. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181732d64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takil A, Eti Z, Irmak P, et al. Early postoperative respiratory acidosis after large intravascular volume infusion of lactated Ringer's solution during major spine surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:294–298. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200208000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khajavi MR, Etezadi F, Moharari RS, et al. Effects of normal saline vs. lactated Ringer's during renal transplantation. Ren Fail. 2008;30:535–539. doi: 10.1080/08860220802064770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Huh KH, Lee JR, et al. Comparison of the effects of normal saline versus Plasmalyte on acid-base balance during living donor kidney transplantation using the Stewart and base excess methods. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2191–2196. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi MP, Vora KS, Parikh GP, et al. A comparative study of impact of infusion of Ringer's Lactate solution versus normal saline on acid-base balance and serum electrolytes during live related renal transplantation. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012;23:135–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCluskey SA, Karkouti K, Wijeysundera D, et al. Hyperchloremia after noncardiac surgery is independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality: a propensity-matched cohort study. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:412–421. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318293d81e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw AD, Bagshaw SM, Goldstein SL, et al. Major complications, mortality, and resource utilization after open abdominal surgery: 0.9% saline compared to Plasma-Lyte. Ann Surg. 2012;255:821–829. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825074f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunos NM, Bellomo R, Hegarty C, et al. Association between a chloride-liberal vs chloride-restrictive intravenous fluid administration strategy and kidney injury in critically ill adults. JAMA. 2012;308:1566–1572. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunos NM, Kim IB, Bellomo R, et al. The biochemical effects of restricting chloride-rich fluids in intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2419–2424. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822571e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YS, Lim H, Kim SH. Comparison of lactated Ringer's solution and 0.9% saline in the treatment of rhabdomyolysis induced by doxylamine intoxication. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:276–280. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.043265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua HR, Venkatesh B, Stachowski E, et al. Plasma-Lyte 148 vs 0.9% saline for fluid resuscitation in diabetic ketoacidosis. J Crit Care. 2012;27:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler SA, Conrad SA, Wang H, et al. Resuscitation with balanced electrolyte solution prevents hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:670–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zyl DG, Rheeder P, Delport E. Fluid management in diabetic-acidosis—Ringer's lactate versus normal saline: a randomized controlled trial. Q J Med. 2012;105:337–343. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieza JA, Hinostroza J, Huapaya JA, et al. Sodium chloride 0.9% versus lactated Ringer in the management of severely dehydrated patients with choleriform diarrhoea. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7:528–532. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasman H, Cinar O, Uzun A, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing the effect of rapidly infused crystalloids on acid-base status in dehydrated patients in the emergency department. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9:59–64. doi: 10.7150/ijms.9.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, et al. Lactated Ringer's solution reduces systemic inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 20119710–717.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]