Abstract

Background and objectives

Survey research is an important research method used to determine individuals’ attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors; however, as with other research methods, inadequate reporting threatens the validity of results. This study aimed to describe the quality of reporting of surveys published between 2001 and 2011 in the field of nephrology.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

The top nephrology journals were systematically reviewed (2001–2011: American Journal of Kidney Diseases, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, and Kidney International; 2006–2011: Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology) for studies whose primary objective was to collect and report survey results. Included were nephrology journals with a heavy focus on clinical research and high impact factors. All titles and abstracts were screened in duplicate. Surveys were excluded if they were part of a multimethod study, evaluated only psychometric characteristics, or used semi-structured interviews. Information was collected on survey and respondent characteristics, questionnaire development (e.g., pilot testing), psychometric characteristics (e.g., validity and reliability), survey methods used to optimize response rate (e.g., system of multiple contacts), and response rate.

Results

After a screening of 19,970 citations, 216 full-text articles were reviewed and 102 surveys were included. Approximately 85% of studies reported a response rate. Almost half of studies (46%) discussed how they developed their questionnaire and only a quarter of studies (28%) mentioned the validity or reliability of the questionnaire. The only characteristic that improved over the years was the proportion of articles reporting missing data (2001–2004: 46.4%; 2005–2008: 61.9%; and 2009–2011: 84.8%; respectively) (P<0.01).

Conclusions

The quality of survey reporting in nephrology journals remains suboptimal. In particular, reporting of the validity and reliability of the questionnaire must be improved. Guidelines to improve survey reporting and increase transparency are clearly needed.

Keywords: nephrology, transplantation, kidney

Introduction

Surveys are studies that use questionnaires or similar instruments to gather information from a subset of a population regarding a specific topic, which can then be used to draw conclusions on the entire population. They are used in many fields, including public opinion, politics, and health research. In medicine, surveys are especially important in studies that require patients or clinicians to self-report their beliefs, knowledge, satisfaction, and attitudes toward constructs that are difficult to measure using alternative approaches (e.g., patient charts or administrative data). In survey research, complete and transparent reporting is necessary for readers to adequately assess bias, strengths and weaknesses of the study, and the generalizability of the results. Unique to survey research, readers also require information on the validity and reliability of the questionnaire and response rates.

Previous research in other clinical areas suggests that the number of surveys published in medical journals is increasing (1). The reporting of factors key to assessing the methodologic quality and applicability of the results in critical care (2) and anesthesia (3) is poor and inconsistent. In addition, most survey studies do not report response rates (4), and many fail to provide access to their questionnaire (5,6). We conducted this study to describe the quality of reporting of survey studies published between 2001 and 2011 from four high-impact nephrology journals. These results can be used to guide the development of future reporting checklists that will aid researchers in the reporting and critical appraisal of survey results.

Materials and Methods

Study Selection

We included studies that used survey methods to answer their primary objective. We included both cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys that used self-administered or interviewer-administered questionnaires. We excluded studies that used the questionnaire to evaluate the effect of an intervention or were part of a larger study (e.g., Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study [DOPPS]); large studies such as DOPPS were excluded because they have been published multiple times using the same questionnaire; therefore, their inclusion may bias results. We also excluded studies that examined only the psychometric characteristics (e.g., validity) of survey instruments or used semi-structured interviews instead of questionnaires.

Identifying Relevant Studies

To include surveys likely to be influential, we searched nephrology journals with a heavy focus on clinical research and included four nephrology journals with high impact factors in the previous 11 years. We focused on nephrology journals because we anticipated that readers of these journals would be most interested in the quality of reporting in their own field, to allow us to compare the state of the literature in nephrology (2,3) with that in other clinical areas and to capitalize on the expertise and research interests of our team. We identified relevant studies by searching electronic versions of Kidney International, American Journal of Kidney Disease, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, and Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (CJASN) (CJASN started publication in 2006). We chose CJASN instead of the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology because with its clinical focus it was more likely to publish survey research. We also searched MEDLINE from 2001 to 2011 using the text words "survey" or "questionnaire" and limited our search to these four journals.

Pairs of reviewers (K.N. and either A.L or S.T.) independently screened the title and/or abstract of each citation to determine eligibility. We retrieved full-text articles for citations that were identified by either reviewer as potentially relevant. The reviewers independently assessed the eligibility of full-text articles. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through re-evaluation and discussion.

Data Abstraction

To extract items that are probably important for interpreting and applying survey results, we modified a data abstraction form from a previous study assessing survey reporting quality (2). We piloted this data collection tool on 10 nephrology survey papers and modified it further on the basis of reviewer feedback. Data were abstracted independently by paired (K.N. and one of the following: A.L, S.T., or A.F.) reviewers and included survey and respondent characteristics, questionnaire development (e.g., pilot testing), psychometric characteristics (e.g., validity and reliability), survey methods used to optimize response rate (e.g., system of multiple contacts), and response rate. Differences in abstraction were resolved between two of the reviewers through discussion and consensus. We defined reliability as the degree to which the results of a survey can be replicated when it is administered multiple times under identical conditions (7,8). Validity was defined as the degree to which the survey measures what it was designed to measure. We defined response rates as the number of surveys included in the analysis divided by the total number of surveys sent to potential respondents.

Data Analysis

We described categorical data as proportions and continuous data as medians and interquartile ranges. We used the Cochran–Armitage test for trend to assess changes in the number of surveys published per year. We used the chi-squared test to examine differences in survey publication among the four journals. We analyzed trends in reporting by dividing surveys into three groups according to year of publication (2001–2004, 2005–2008, 2009–2011). To examine whether reporting improved over time, we used the Kruskal–Wallis test and examined the proportion of studies that reported (1) response rate, (2) any method of dealing with missing data, and (3) any clinimetric properties of the survey instrument, and included (4) the questionnaire (or a link to the questionnaire). For this test only, we compared studies that completely or partially described the amount of missing data to those that did not. We also compared studies that completely or partially provided access to the questionnaire (partially: provided link to questionnaire; completely: questionnaire attached to article) to those that did not. We conducted all analysis using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Study Selection

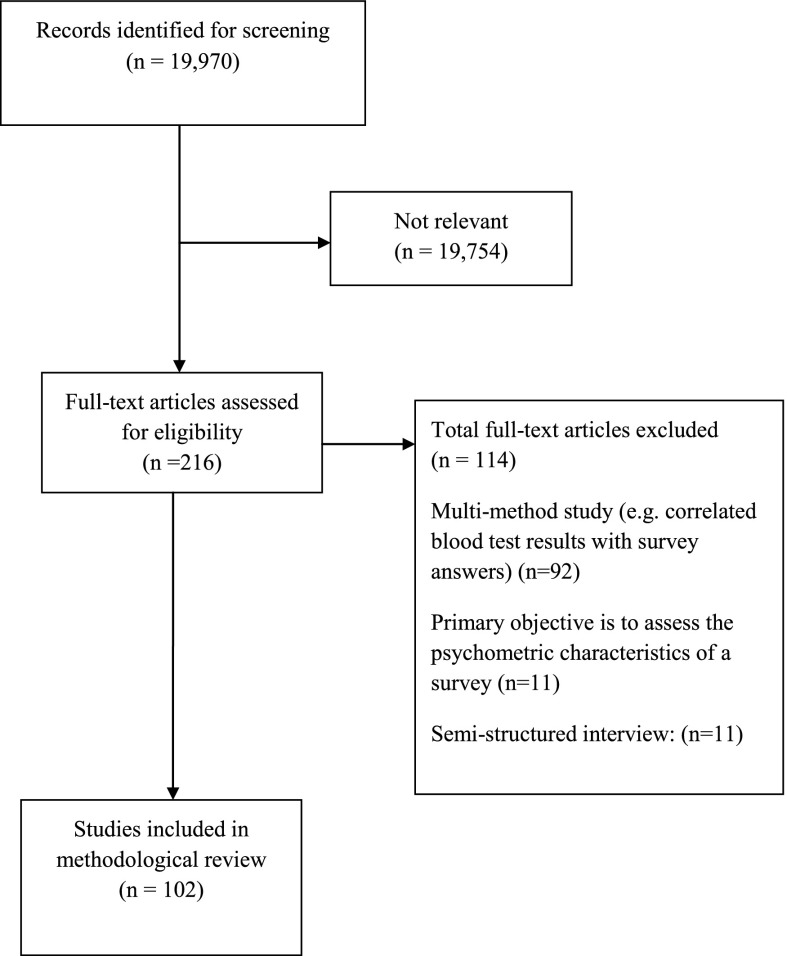

We screened 19,970 citations and retrieved 216 potentially relevant full-text articles to assess for eligibility (Figure 1). We included 102 surveys (see Supplemental Table 1 for full list of included studies and study characteristics). The main reasons for exclusion included multimethod study (n=92), semi-structured interview (n=11), part of a larger study (n=10), and validation study (n=11).

Figure 1.

Study diagram of included surveys.

Description of Included Studies and Survey Respondents

The number of surveys published varied among the four nephrology journals (Supplemental Figure 1) (ranging from 1.3 surveys published per 1000 citations in Kidney International to 10.4 surveys published per 1000 citations in CJASN; P<0.001). Included surveys were most frequently conducted in North America (United States [43.1%], Canada [10.8%], or both [5%]) (Table 1). Most surveys focused on describing the respondent’s attitudes, opinions, or perceptions (62.7%); behaviors or practices (39.2%); and knowledge (12.7%). Topics of the survey varied, but the two most popular topics were specific disease management (e.g., survey of how nephrologists manage end-of-life care) (19.6%) and organ donation (14.7%). Most surveys were self-administered (88%). More studies surveyed exclusively health care workers (45.1%) than other individuals (e.g., patients, family members) (44.1%) (Table 1). The remaining studies surveyed a combination of health care workers, patients, and their family members (10.8%). The majority of surveys that reported how they selected respondents sampled a readily and available group (convenience sampling) to obtain their respondents (84.2%). Of the 13 studies (12.7%) that reported using an incentive, 10 (76.9%) provided financial incentives (the amount ranged from $1 to $50 USD, with a median of $20) and three studies (23.1%) provided other forms of incentives, such as educational pamphlets. Two studies reported providing a “small compensation” but did not reveal the total amount.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Country(ies)/continent on which survey was conducteda | |

| Multinational (>1 region) | 6 (5.9) |

| North America | 60 (58.8) |

| United States | 44 (43.1) |

| Canada | 11 (10.8) |

| United States/Canada | 5 (4.9) |

| Europe | 27 (26.5) |

| Australia | 4 (3.9) |

| Asia | 3 (2.9) |

| Other | 2 (2) |

| Geographic scope | |

| Single center | 11 (10.8) |

| Single city | 14 (13.7) |

| Region within a country | 21 (20.6) |

| National | 37 (36.3) |

| Multinational | 18 (17.6) |

| Not reported | 1 (1) |

| Focus on survey | |

| Attitudes/opinions/perceptions | 64 (62.7) |

| Behaviors or practice | 40 (39.2) |

| Knowledge | 13 (12.7) |

| Topic of survey | |

| End-of-life care | 10 (9.8) |

| Quality of life | 14 (13.7) |

| Prescribing/referral practices | 12 (11.8) |

| Specific disease management | 20 (19.6) |

| Transplantation | 6 (5.9) |

| Organ donation | 15 (14.7) |

| Medication | 2 (2) |

| Education/training/career | 3 (2.9) |

| Patient satisfaction | 1 (1) |

| Administration | 4 (3.9) |

| Dialysis | 8 (7.8) |

| Otherb | 15 (14.7) |

| Study populationc | |

| Health care workers | 46 (45.1) |

| Other (e.g., patients, family members) | 45 (44.1) |

| Both | 11 (10.8) |

| Professional affiliation of health care workers | 60/102 |

| Nephrologist | 34 (56.7) |

| Surgeon | 4 (6.7) |

| Resident | 6 (10) |

| Nurse | 6 (10) |

| Physician assistant | 1 (1.7) |

| Administrator | 10 (16.7) |

| Physician | 12 (20) |

| Type of patient | 52/102 |

| Dialysis | 31 (59.6) |

| Renal transplant candidates | 2 (3.8) |

| Transplant recipients | 11 (21.2) |

| General public | 5 (9.6) |

| Caregiver | 1 (1.9) |

| Other | 5 (9.6) |

| Type of survey | |

| Cross-sectional | 100 (98) |

| Longitudinal | 2 (2) |

| Mode of administration | |

| Self-administered | |

| Paper | 67 (65.7) |

| Internet | 14 (13.7) |

| Combination of both | 9 (8.8) |

| Interviewer administered | |

| Face-to-face or telephone interview | 11 (10.8) |

| Unclear | 1 (1) |

| How respondents were selected | |

| Convenience | 85 (84.2) |

| Random | 16 (15.8) |

| Stratified | 6 (5.9) |

| Cluster | 0 (0) |

| Not reported | 1 (1) |

| Reimbursement | |

| Yes | 13 (12.7) |

| No | 89 (87.3) |

| Minimum ($) | 1 |

| Median amount (of those that used a cash reimbursement) (%) | 20 |

| Highest ($) | 50 |

Unless otherwise noted, values are the number (percentage) of studies. Totals may be >100% since more than one response per survey was possible.

Both Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology and American Journal of Kidney Disease are journals from the United States, which is a potential reason for the high proportion of surveys conducted in the United States.

Other survey topics included informed consent, smoking, burnout, cancer screening practices, religion, post-traumatic stress disorder, clinician opinion on clinical practice guidelines, near-death experiences, willingness to participate in a randomized control trial, pain patterns, kidney stones, HIV, assessment of nephrology training program, disaster preparedness, practitioner communication.

Numbers may not add up to 100% because some studies surveyed both health care workers and patients.

Survey Quality of Reporting

Characteristics of survey quality are reported in Table 2. Three quarters of surveys (75.5%) described the demographic characteristics of respondents extensively. Less than half of the included surveys reported any details of the development of their questionnaire (45.5%) (Table 2). Approximately one quarter of surveys reported any measure of the validity or reliability for the questionnaire being used (27.3%).

Table 2.

Quality of survey reporting in nephrology journals

| Quality Characteristics | Data, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Multiple reminders to participate/ fill out survey | |

| Yes | 44 (43.1) |

| No | 58 (56.9) |

| Questionnaire developmenta | |

| Yes | 47 (46.1) |

| No | 55 (53.9) |

| Instrument validity/reliability described | |

| Yes | 29 (28.4) |

| No | 73 (71.6) |

| Eligibility criteria for respondents | |

| Yes | 66 (64.7) |

| No | 36 (35.3) |

| Characteristics of respondents reported | |

| Extensively | 77 (75.5) |

| Minimally | 15 (14.7) |

| No | 10 (9.8) |

| Response rate reported | |

| Yes | 87 (85.3) |

| No | 15 (14.7) |

| Response rate | |

| Median | 65.0 |

| ≥%50 | 64 (62.7) |

| < %50 | 23 (22.5) |

| Flow diagram of survey responses | |

| Yes | 9 (8.8) |

| No | 93 (91.2) |

| Questionnaire was linked/appended to paper | |

| Yes | 38 (37.3) |

| No | 28 (27.5) |

| Partially | 36 (35.3) |

| Amount of missing data reported | |

| No | 35 (34.3) |

| Partially | 37 (36.3) |

| Completely | 30 (29.4) |

| Was the term “survey” explicitly explained in titleb | |

| Yes | 21 (20.6) |

| No | 81 (79.4) |

| Research ethics board approval reported | |

| Yes | 58 (56.9) |

| Yes, stated not required | 4 (3.9) |

| No | 40 (39.2) |

Questionnaire development defined as any pretesting done on the survey instrument (i.e., pilot testing).

We determined that the term “survey” was included in the title under the following conditions: term “survey” or term “questionnaire” was contained in the title or if any common survey that is administered (i.e., Short-Form 36) was contained in the title.

Approximately 85% of surveys reported a response rate or provided sufficient information to allow the reader to calculate a response rate. Of those that reported a response rate, the response rates ranged from 7.4% to 100.0%, with a median (Q1, Q3) of 65% (48%, 79%). Nearly all studies (99%) reported the total number of questionnaires included in the analysis, which ranged from 34 to 4013, with a median (Q1, Q3) of 216 questionnaires (131, 461). Approximately 43% of studies reported that they provided multiple reminders to complete the survey. Only 9% of studies provided a flow diagram of the passage of survey participants through the study.

Seventy-eight studies (76.5%) reported the year the study was conducted. The difference between the year it was published and conducted ranged from 0 (conducted and published in the same year) to 15 years, with a median of 2 years. Fourteen studies (13.7%) were published 5 or more years after the questionnaire was distributed.

The amount of missing data was described completely by 29.4% of included studies and partially by 36.3%; 34.3% did not mention missing data.

Trends in Reporting Quality and Survey Publication over Time

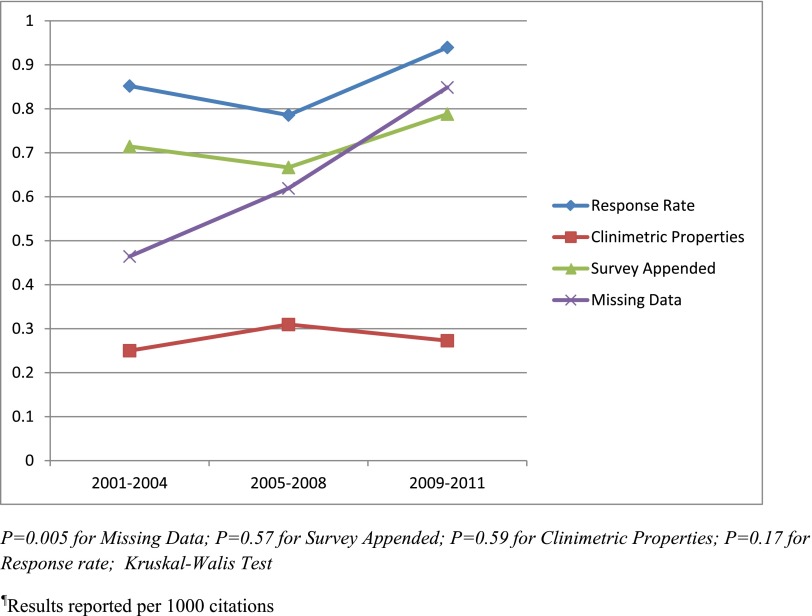

Survey publication did not significantly increase over time from 2001 to 2011 (Supplemental Figure 2) (ranging from five surveys published per 1000 citations in the year 2002 and a maximum of 14 surveys per 1000 citations in 2008; P=0.051). The number of surveys published increased over time but then decreased in 2010, with only 11 surveys per 1000 citations and only nine surveys per 1000 citations in 2011. During the three time periods we assessed (2001–2004, 2005–2008, 2009–2011), the proportion of surveys that reported response rates (85.2%, 78.6%, and 93.9%, respectively; P=0.17), clinimetric properties (25%, 31%, and 27.3%, respectively; P=0.59) and access to survey (71.4%, 66.7%, and 78.8%, respectively; P=0.57) did not significantly increase (Figure 2). Only the proportion of surveys that reported the amount of missing data significantly increased over time (46.4%, 61.9%, and 84.8%, respectively; P<0.01).

Figure 2.

Trends of reporting of four properties from 2001 to 2011.

Discussion

We found that the reporting quality of survey research in top nephrology journals was suboptimal. Most studies reported a response rate (85.3%); however, many studies failed to report other key survey characteristics necessary to assess the validity of results, including clinimetric properties (71.6%), survey development (53.9%), amount of missing data (34.3%), and access to the questionnaire (27.5%).

Our findings are similar to those of other studies that have assessed the reporting quality of surveys in medical journals. In critical care, Duffet et al. emphasized the need for more comprehensive and uniform reporting standards, given the growth of survey research over time (2). Specifically, they found that only 28.5% of studies reported on survey psychometric characteristics, which is similar to the 27.4% found in our study. They also found few improvements in reporting quality over time; only improvements in the reporting of psychometric characteristics increased significantly. Story et al. assessed survey reporting quality in anesthesia journals, concluding that the reporting was inconsistent (3). Gaps in the quality or reporting are also evident in other research designs in nephrology. For example, Strippoli et al. found that the quality of reporting in nephrology randomized controlled trial was low, with no improvements seen over 30 years (9).

The median response rate was 65%, similar to those reported in surveys conducted in critical care journals (63%) (2). Low response rates may threaten the validity of the findings and conclusions of survey studies; some journals do not accept articles with response rates <60% (1). Recommended strategies from systematic reviews to increase response rates include using financial incentives not conditional on response, using personalized questionnaires, multiple reminders, colored ink, stamped return envelopes, and sending the questionnaire by first-class post (10–12). The response rate is not the only criterion for a rigorous survey; others have argued that there is no scientifically proven minimum response rate and recommend that evaluating nonresponse bias is more useful for understanding the survey’s usefulness (13).

On the basis of the reporting gaps identified in this methodologic review, we make several recommendations. First, we recommend that journals endorse minimum standards for reporting of surveys. These standards exist for other study designs, such as systematic reviews (14) and randomized controlled trials (15). Although no well developed reporting guidelines currently exist for survey research (1), recommendations for the reporting of survey studies have been published (16–18). Authors at a minimum should report response rates, whether the survey has been validated, provide access to the questionnaire, and information on missing data. Second, in addition to response rate, authors should provide the number of surveys distributed and returned. Third, the use of a flow diagram showing the number of questionnaires distributed, the number of participants who were ineligible, the number of individuals who did not respond, and the number of questionnaires completed and included in the analysis would help authors assess the external validity of results. Fourth, authors should describe how they developed the questionnaire and whether the questionnaire’s reliability or validity was tested. Fifth, the questionnaire should be readily available in the print journal, a journal online supplemental repository or other questionnaire databases (5). Schilling et al. found that 37 of 81 (46%) corresponding authors failed to provide the questionnaire used in their study despite repeated contact (5). Readers and reviewers may have increased confidence about the authors’ interpretation if they have access to the exact wording of the questionnaire. Authors should also describe any methods they may have used to account for missing data, such as any weighting or imputation methods. Finally, authors should use and report on methods to increase the quality of the questionnaire and quality of participants’ responses. For example, the Tailored Design Method is a widely used scientific framework for survey research in multiple fields and has been found to decrease total survey error, including coverage error, nonresponse error and sampling error (19). Specifically, this strategy recommends multiple respondent contacts and financial incentives (19).

To help increase the quality of survey reporting, future efforts should focus on the development of a survey reporting checklist using a structured approach (20). Guidelines would aid authors in study development, manuscript preparation, and the peer-review process by providing reviewers with a set of standardized criteria to assess survey manuscripts (21). Most important, a set of validated survey reporting guidelines may increase survey reporting quality and allow for readers to adequately assess the validity of findings. There are currently several resources that nephrologists can use as a guideline to assist with the critical appraisal and reporting of survey research (1,16–18).

Our review has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the quality of reporting in surveys published in nephrology journals. We screened almost 20,000 articles to identify studies relevant for this review. We screened articles independently and in duplicate. One reviewer (K.N.) extracted data for all articles to ensure consistency. We assessed the reporting of survey studies using a modified version of a previously used tool (2). However, our review has some limitations that deserve mention. We looked only at trends in reporting quality over an 11-year period (2001–2011), and it is possible that different results may have been found if a longer time period had been selected. Although we used measures similar to those of two previous studies assessing the reporting of survey studies, there is no consensus on a standard set of criteria (2,3).

In conclusion, the reporting quality of survey studies in nephrology journals is suboptimal, and no evidence suggests that the quality of reporting has improved substantially in the past decade. Improved survey reporting is therefore needed to increase transparency and increase the reader’s confidence in the study results.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Speechley for her support.

A.H.T.L. was supported by a Kidney Foundation Scholarship. K.L.N. was supported by Osteoporosis Canada’s Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study Fellowship.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.02130214/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bennett C, Khangura S, Brehaut JC, Graham ID, Moher D, Potter BK, Grimshaw JM: Reporting guidelines for survey research: An analysis of published guidance and reporting practices. PLoS Med 8: e1001069, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duffett M, Burns KE, Adhikari NK, Arnold DM, Lauzier F, Kho ME, Meade MO, Hayani O, Koo K, Choong K, Lamontagne F, Zhou Q, Cook DJ: Quality of reporting of surveys in critical care journals: A methodologic review. Crit Care Med 40: 441–449, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Story DA, Gin V, na Ranong V, Poustie S, Jones D, ANZCA Trials Group : Inconsistent survey reporting in anesthesia journals. Anesth Analg 113: 591–595, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badger F, Werrett J: Room for improvement? Reporting response rates and recruitment in nursing research in the past decade. J Adv Nurs 51: 502–510, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schilling LM, Kozak K, Lundahl K, Dellavalle RP: Inaccessible novel questionnaires in published medical research: Hidden methods, hidden costs. Am J Epidemiol 164: 1141–1144, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen T, Olsen J: Invited commentary: The art of making questionnaires better. Am J Epidemiol 164: 1145–1149, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porta M: A Dictionary of Epidemiology, 5th Ed. Oxford, New York, Oxford University Press, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher RW, Fletcher SW. Clinical Epidemiology: The Essentials, 4th Ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strippoli GFM, Craig JC, Schena FP: The number, quality, and coverage of randomized controlled trials in nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 411–419, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakash RA, Hutton JL, Jørstad-Stein EC, Gates S, Lamb SE: Maximising response to postal questionnaires—a systematic review of randomised trials in health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 6: 5, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.VanGeest JB, Johnson TP, Welch VL: Methodologies for improving response rates in surveys of physicians: A systematic review. Eval Health Prof 30: 303–321, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C, Pratap S, Wentz R, Kwan I: Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: Systematic review. BMJ 324: 1183, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson TP, Wislar JS: Response rates and nonresponse errors in surveys. JAMA 307: 1805–1806, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group : Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151: 264–269, W64, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gøtzsche PC, Lang T, CONSORT GROUP (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) : The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: eEplanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 134: 663–694, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burns KEA, Duffett M, Kho ME, Meade MO, Adhikari NKJ, Sinuff T, Cook DJ, ACCADEMY Group : A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ 179: 245–252, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, Sitzia J: Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Health Care Qual 15: 261–266, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Draugalis JR, Coons SJ, Plaza CM: Best practices for survey research reports: A synopsis for authors and reviewers. Am J Pharm Educ 72: 11, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dillman DA, Smyth, Christian LM, Dillman DA: Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Hoboken, NJ, Wiley & Sons, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG: Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med 7: e1000217, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, Poole C, Schlesselman JJ, Egger M, STROBE initiative : Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 147: W163–94, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.