Abstract

After Medicare’s implementation of the bundled payment for dialysis in 2011, there has been a predictable decrease in the use of intravenous drugs included in the bundle. The change in use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, which decreased by 37% between 2007, when its allowance in the bundle was calculated, and 2012, was because of both changes in the Food and Drug Administration labeling for erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in 2011 and cost-containment efforts at the facility level. Legislation in 2012 required Medicare to decrease (rebase) the bundled payment for dialysis in 2014 to reflect this decrease in intravenous drug use, which amounted to a cut of 12% or $30 per treatment. Medicare subsequently decided to phase in this decrease in payment over several years to offset the increase in dialysis payment that would otherwise have occurred with inflation. A 3% reduction from the rebasing would offset an approximately 3% increase in the market basket that determines a facility’s costs for 2014 and 2015. Legislation in March of 2014 provides that the rebasing will result in a 1.25% decrease in the market basket adjustment in 2016 and 2017 and a 1% decrease in the market basket adjustment in 2018 for an aggregate rebasing of 9.5% spread over 5 years. Adjusting to this payment decrease in inflation-adjusted dollars will be challenging for many dialysis providers in an industry that operates at an average 3%–4% margin. Closure of facilities, decreases in services, and increased consolidation of the industry are possible scenarios. Newer models of reimbursement, such as ESRD seamless care organizations, offer dialysis providers the opportunity to align incentives between themselves, nephrologists, hospitals, and other health care providers, potentially improving outcomes and saving money, which will be shared between Medicare and the participating providers.

Keywords: economic effect, ESRD, chronic dialysis

The Legislative and Regulatory Basis for Rebasing

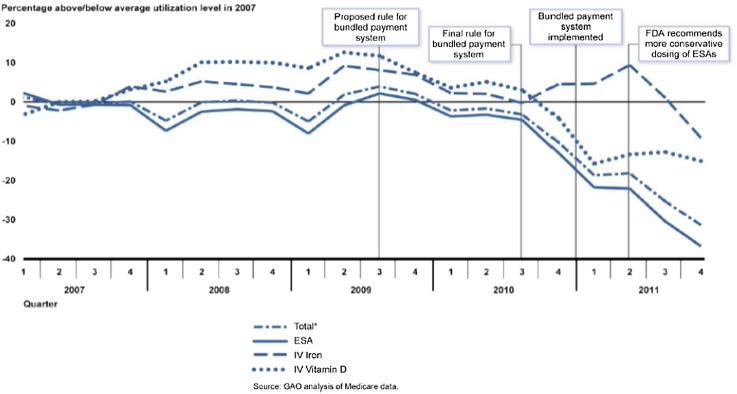

As of January 1, 2011, the dialysis treatment bundled payment was expanded to include all technical services in the composite rate, intravenous (IV) medications related to kidney disease and their oral equivalents, and laboratory testing. Congress predicted that there would be efficiencies achieved and reduced the overall bundled payment by 2%. It was assumed by many dialysis providers, nephrologists, and kidney patient groups that this 2% payment reduction was primarily on the basis of an expected decrease in erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) use under the bundled payment. In July of 2011, the Food and Drug Administration issued a Black Box Warning on ESAs stating that physicians should prescribe the lowest dose possible to prevent the need for blood transfusion. Between the label change and the effect of the bundle, the use of ESAs decreased. Although the intent of the bundle was to incentivize more efficient practices, the decrease in ESA use was highly publicized. The Government Accountability Office issued a report that highlighted the decrease in drug use in dialysis (1) (Figure 1). In addition, major newspapers, such as The Washington Post, ran front page stories criticizing the Federal Government for overpaying for these drugs (2). The Congressional Budget Office had estimated that a decrease in payments reflective of the decreased use of EPA and other drugs would reduce overall Medicare spending on ESRD by $4.9 billion over 10 years (3).

Figure 1.

Use of ESRD drugs per beneficiary per quarter through 2011 relative to average level in 2007. Use was expressed in dollars by multiplying the number of units per beneficiary of a drug administered in a given quarter by Medicare’s average sales price for this drug in the first quarter of 2011. FDA, Food and Drug Administration. aIncludes use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), intravenous (IV) iron, and IV vitamin D. Reprinted from ref. 1, Government Accountability Office (GAO).

This potential saving was picked up by Congress as a “pay for” (or offset) when it drafted the American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) in 2012. As a “pay for”, the anticipated savings were used to cover the cost of an extension of the sustainable growth rate, delaying the implementation of cuts to all physician payments by Medicare until April 1, 2014. Congress mandated that Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) adjust the ESRD Prospective Payment System (PPS) in 2014 to account for the change in use of IV drugs. This reimbursement cut was referred to as rebasing, because it set the payment for ESRD IV drugs at 2012 use rates rather than the 2007 level used to establish the original bundled payment in 2011. However, it did not rebase the bundled payment system, because it only affected one cost center instead of the entire set of costs associated with providing services to beneficiaries with ESRD. Before the time that the bundled payment was implemented in 2011, many providers, on average, lost money on composite rate treatments and made money on the separately billable IV medications. Reducing the bundle because of decreased drug use and totally ignoring the prior composite rate losses would result in inadequate reimbursement.

To implement ATRA, CMS issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (Proposed Rule) in July of 2013. The Proposed Rule would have cut the per-treatment payment rate by approximately $30 or 12%, which was significantly higher than estimates made by the industry on the basis of provider experiences. Although many dialysis providers, nephrologists, and kidney patient groups agreed that use of ESAs had decreased, they also raised concerns that CMS had not calculated the original bundled payment rate correctly. They also raised concerns that the Proposed Rule ignored the fact that Congress had already reduced the payment rate by 2% in 2011 to adjust for assumed efficiencies, including changes in the use of drugs such as ESAs. Compounding the situation was an across-the-board 2% cut in reimbursement to all Medicare providers, including dialysis facilities, that began in March of 2013 as part of the sequester to respond to the Federal budget crisis.

The threat of a $30 per treatment cut on top of the 2% sequester cut was overwhelming to most providers. The concerns were validated by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) (4), which estimated that the dialysis facility aggregate Medicare margin was between 2% and 3% in 2011 and projected that the aggregate Medicare margin would be between 3% and 4% in 2013 before the proposed cut. These data points were also consistent with the independent analysis prepared by The Moran Company (5) using CMS cost reports. Thus, a 12% cut would result in significantly negative Medicare margins and could lead to substantial changes in the way that patients receive dialysis treatments. Small, rural, and inner city facilities were at the highest risk for these negative Medicare margins, and their possible closure could threaten patient access to ESRD care.

In the Final Rule published in December of 2013 (6), CMS maintained the magnitude of the per-treatment cut but indicated that the cut would be spread over 3–4 years. During 2014, the portion of the cut implemented was slightly greater than the market basket increase in payment for 2014 for technical reasons. The market basket increase is the annual adjustment that dialysis providers receive in their payment from CMS because of the changes in the costs of labor, supplies, and overhead. CMS promised to set the rebasing cut at the market basket amount for 2015. Thus, the final payment adjustment for 2014 and 2015 amounts to a 2-year market basket freeze. CMS did not indicate how it planned to implement the remainder of the rebasing payment cut in 2016 and/or 2017.

At the end of March of 2014, Congress passed H.R. 4302: “Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014” (PAMA) (7), which includes a provision that would reduce the magnitude of the ATRA rebasing cut. The legislation requires CMS to set the market basket increase at zero for 2015 to accomplish the intent that CMS expressed in the Final Rule to set 2015 reimbursement rates at the 2014 level. The new law then replaces the remainder of the cut with a 1.25% reduction in the market basket for 2016 and 2017 and a 1.0% reduction in the market basket for 2018. Table 1 summarizes the magnitude of the cuts in percentages from 2014 to 2018. Analysis of this provision suggests that the overall cut has been reduced from 12% to approximately 9.5%.

Table 1.

Annual negative adjustment to the market basket increase in dialysis reimbursement

| Year | Rebasing Adjustment |

|---|---|

| 2014 | Complete offset of market basket increase (approximately −3%) |

| 2015 | Complete offset of market basket increase (approximately −3% anticipated) |

| 2016 | −1.25% |

| 2017 | −1.25% |

| 2018 | −1.0% |

| Total | Approximately −9.5% |

Although the Medicare rebasing cuts are less than the originally proposed $30 per treatment in inflation-adjusted dollars, many dialysis providers, nephrologists, and kidney patient groups remain focused on the dramatic reduction in Medicare payments to dialysis facilities because of its potential to negatively affect patient care. The Moran Company estimates that, even with a market basket freeze in 2014 and 2015, >55.6% of dialysis facilities will have negative Medicare margins in 2014 when taking into account the 2% sequestration cut that occurred in 2013 (5). That number increases to >65% in 2015. Even with the relief provided in recent legislation, it is possible that many dialysis facilities will have to make difficult decisions that could reduce their hours of operation, limit certain services or programs, reduce staff, not offer competitive salaries and benefits, or lead to facility closures.

How CMS Determines Reimbursement for Dialysis

A summary of legislation affecting payment for the ESRD Program is in Table 2. Congress determines the law that governs Medicare reimbursement, and CMS is responsible for interpreting the laws and writing the rules that provide the details through the rule-making process. The authority of CMS is not black and white; it permits some flexibility and is sometimes challenged, because it is interpreting congressional intent. For instance, under the authority that established the ESRD PPS, CMS calculates the market basket to establish the percentage increase to the payment rate on the basis of the change in costs and then applies the productivity adjustor. CMS does not evaluate the actual costs, and it uses price proxies in most cases for purposes of calculating changes in the market basket. Although many dialysis providers, nephrologists, and kidney patient groups believe that CMS has the authority to examine other components of the payment system, such as the case-mix adjustors, outlier pool, and standardization factor, it has not done so.

Table 2.

Key legislation affecting payment for the US ESRD Program

| Year | Public Law | Title | Major Provisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 92–603 | Social Security Act of 1972 | Medicare coverage of patients with ESRD <65 yr of age after a 3-mo waiting period |

| 1978 | 95–292 | ESRD Program Amendments of 1978 | Elimination of the 3-mo waiting period for home dialysis or transplantation |

| 1981 | 97–35 | Omnibus Reconciliation Act | Establishment of single prospective rate to cover all services and supplies for dialysis (composite rate); excluded certain laboratory tests and drugs that were separately billable; MSP for 12 mo after the patient qualifies for Medicare if that patient has employer group health insurance |

| 1986 | 99–509 | Omnibus Reconciliation Act | Mandatory $0.50 withhold per treatment to fund ESRD Networks |

| 1991 | MSP increased to 18 mo | ||

| 2003 | 108–173 | MMA | Statutorily mandated increases in composite rate to adjust for inflation; separately billable drugs reimbursed at average sales price plus 6% (rather than average wholesale cost); composite rate add on to replace drug margins; MSP increased to 30 mo; case-mix adjustment for age and body size |

| 2008 | 110–275 | MIPPA | Established bundled reimbursement to include composite rate items and services, injectable drugs and their oral equivalents, and laboratory tests to begin in 2011; oral-only ESRD drugs to be included in the bundle in 2014; new case-mix adjusters; elimination of higher payment for hospital-based providers; Quality Incentive Program to begin in 2012 |

| 2012 | 112–240 | ATRA | Mandated rebasing of dialysis reimbursement to reflect lower use of drugs; oral-only ESRD drugs to be included in the bundle in 2016 |

| 2014 | 113–93 | PAMA | Spreads out and reduces rebasing reimbursement cut; oral-only drugs to be included in the bundle in 2024 |

MMA, Medicare Modernization Act; MIPPA, Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act; American Taxpayer Relief Act; PAMA, Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014; MSP, Medicare to be secondary payer.

Each year, MedPAC reports to Congress on the average Medicare margin for dialysis facilities. It uses the facility cost reports to make this estimate. Historically, Congress relied on the MedPAC reports to justify the modest increases in the payment rates by legislation. CMS has no obligation to incorporate the recommendations or analyses of MedPAC into its rulemaking. Even so, section 1881(b)(2)(B) of the Social Security Act, which also provides the authority for the cost reports, requires CMS to consider the cost of providing services in its calculation of the payment rate. However, in its most recent rule-making finalizing the ATRA reimbursement cut, CMS suggested that it did not have to take the cost of providing services into account. Interestingly, in that same rule-making, CMS references the recommendation by MedPAC for a market basket freeze in 2014 to support the final 2014 payment rate. However, at the same time, CMS does not acknowledge the suggestion by MedPAC to act cautiously and not modify the payment rate on the basis of the limited data available on drug use.

The disconnect between the cost of providing services and the payment rate was most visible when CMS proposed a 12% cut in the payment rate for 2014 in the Proposed Rule, whereas MedPAC had calculated the Medicare margin to be between only 2% and 3% in 2011 and projected that the aggregate Medicare margin would be between 3% and 4% in 2013. In its 2013 report (4), MedPAC identified a drop in the use of some drugs but also recommended that Congress not rebase the payment amount on the basis of these changes, because more time was needed to understand the effect of the change in terms of the overall system.

CMS maintained that it was bound by a strict interpretation of ATRA and could not take the margins into account or adjust the amount of the rebasing cut. CMS established the phase-in to soften the financial blow to facilities so that the full effect of the cut was not felt in a single year. It is also important to note that many dialysis providers, nephrologists, and kidney patient groups believe that the MedPAC methodology overstates the margin. This finding is because the dialysis facility cost reports do not reflect several actual facility costs and because MedPAC assumes that the facility is receiving the full Medicare bundled reimbursement rate for all patients on Medicare (Table 3), meaning that inadequate Medicaid reimbursement for patients with dual eligiblility, inadequate or absent Medi-Gap insurance for patients on Medicare <65 years old, and uncollectable patient deductibles and copays are excluded from the analysis. Only a small portion of actual medical director fees is allowed to be included in the cost report. In addition, Medicare reimbursement is automatically reduced by $0.50 per treatment to fund the ESRD Network Program. Since April 1, 2013, all Medicare providers, including dialysis facilities, have had their reimbursement reduced by 2% as the result of the sequestration cut to help fund the Federal Government.

Table 3.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission underestimates true dialysis facility margins

| Unallowable Cost Report Expenses | Inadequate Reimbursement |

|---|---|

| Network $0.50 per treatment tax | Reimbursement for patients with 100% Medicaid varies by state; some states pay far less than the cost of treatment |

| Actual Medical Director salaries exceed regulatory limit for cost report | Reimbursement for patients with 20% Medicaid varies by state; some states do not pay the full amount |

| Patients without 20% Medicare copay coverage; many states do not offer Medi-Gap insurance for patients<65 yr of age | |

| Many patients cannot afford high copays and deductibles; results in provider bad debts for up to 9 mo/yr | |

| Inability to collect all Medicare bad debts | |

| 2% pay cut from Medicare sequester not included in calculation |

Approximately 25% of patients with incident ESRD are on Medicaid (8). After 3 months (or sooner if they begin home dialysis training), these patients become dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid if they meet Medicare requirements. Some patients will remain 100% Medicaid, because they did not pay into the Social Security System for 20 quarters. The percentage of patients on Medicaid with dual eligiblility is considerably higher at inner city facilities. Many states pay the full 20% Medicare-allowable copay for patients with dual eligiblility, some states pay a percentage of it, and some states pay none at all. The variation in Medicaid payment places an additional financial strain on facilities in states with the lowest Medicaid payments. About 80% of patients with prevalent ESRD are covered by Medicare (8), and therefore, changes in Medicare reimbursement affect all dialysis providers. The effect of Medicare payment cuts is magnified in facilities that have a low percentage of patients with commercial insurance, have a high percentage of patients on Medicaid, or operate in one of the states that does not offer Medi-Gap insurance for patients on Medicare <65 years of age. Increasing bad debts not only adversely affect a dialysis provider’s bottom line, but it also is not an allowable expense on the cost reports. High-deductible health insurance plans have become increasingly popular with patients because of the lower premium costs, but many patients cannot afford the deductibles and copays. Federal legislation has decreased the ability of all Medicare providers (not just dialysis facilities) to claim bad debts on their cost reports as a means for the government to decrease health care expenditures.

Implications for Dialysis Providers

Although Medicare reimbursement is not being cut as rapidly or severely as first proposed, it may be insufficient to meet the increasing cost of care in the future. Providers must evaluate changes that they need to make to protect a facility from closure. Facilities that do not have a significant commercial payer mix, serve a high percentage of dually Medicare/Medicaid-eligible beneficiaries and/or a significant number of patients with 100% Medicaid, have a low wage index, and/or have a low volume of patients that is slightly higher than the threshold to receive the low-volume payment adjustor are at increased risk. These variables tend to disproportionately affect rural, small, and inner-city facilities. One can argue that dialysis is like any business: what is the harm if less economically healthy facilities fail and additional consolidation in the industry occurs? If a few providers can care for patients on dialysis more efficiently, is there a cause for concern?

The most obvious consequence is a limitation of choice for patients, nephrologists, and health-care staff. When fewer providers care for patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis have less choice for where they can receive their care. Currently, many communities are only served by one dialysis provider. In other communities, two providers care for patients, and with the continued limitations on reimbursement, in certain locations, both providers are providing this care at a financial loss. As financial pressures increase, it is likely that many of these communities will only be served by one dialysis provider. It is possible that the quality of care will also suffer if there is no longer competition in the same community. Deveraux et al. (9) and Garg et al. (10) compared mortality rates for different providers in the 1990s. Deveraux et al. (9) and Garg et al. (10) both found that the mortality rates for nonprofit clinics were lower than for-profit clinics. Garg et al. (10) also found a fascinating aspect of competition: in those counties in which both a for-profit and a nonprofit provider cared for patients on dialysis, the mortality rates and rates of placement on a transplant waiting list in for-profit facilities improved to the point that there was no longer a statistically significant difference from nonprofit facilities for these two clinical outcomes. This finding does not suggest that nonprofit care is inherently better than for-profit care but that competition likely improves outcomes.

There is an apparent disconnect between the concerns about decreasing Medicare reimbursement for dialysis and the fact that new dialysis facilities are being built to meet the demands for services while stock prices for the two large dialysis organizations (LDOs) are increasing. Every dialysis provider’s profitability and survival are on the basis of payments by commercial insurers. The LDOs have the leverage to negotiate contracts with commercial insurers for dialysis payments that are multiples of the Medicare rate. Most smaller providers cannot negotiate similar contracted rates. Dialysis companies try to subsidize their money-losing facilities with revenues from facilities with higher percentages of patients with commercial insurance. The larger the dialysis organization, the greater the ability to spread that extra revenue to open or absorb facilities with a less-favorable payer mix. Dialysis companies target growth in geographic areas where there is a higher percentage of commercial payers. However, the commercial insurance carriers are becoming much more aware of the lower Medicare reimbursement rates for ESRD and gradually decreasing their contracted rates as well.

Opportunities to Improve Cost-Effectiveness in the Current Reimbursement System

The recent decreases in Medicare reimbursement for dialysis are part of the larger Federal strategy for cost-effective health care guided by CMS’s “Triple Aim” of “better care for the individual through beneficiary and family centered care,” “better health for the population,” and “reduce[d] costs of care by improving care” (11). As of 2011, Medicare ESRD expenditures were $34.3 billion of a total Medicare budget of $549.1 billion or 6.2% (12). This is not an insignificant figure in the eyes of legislators and regulators who are responsible for preserving the Medicare Trust Fund. Medicare has always assumed continual increases in ESRD program productivity and efficiency, resulting in decreasing (in inflation-adjusted dollars) reimbursement from the 1970s to the mid-2000s. These advances in technology, labor substitution, and organizational innovation have been remarkably sustainable until recent years. The Affordable Care Act assumed a continuation in this productivity trend by mandating that all Medicare contractors have their payment adjusted to reflect the same productivity as the 10-year rolling average of the Non-Farm Labor Productivity measure in the general economy (about 1.0%–1.5% per year in recent years). This is the minimum reduction in all individually paid services by Medicare.

A number of opportunities for responding to the payment decrease from rebasing has been proposed, which are summarized in Table 4. With much of the fat having been whittled away by inflation-adjusted decreases in reimbursement over the past 40 years, the identification of new opportunities for improving cost-effectiveness under the current reimbursement system is becoming increasingly challenging, especially for the magnitude of productivity gains that will be required by a 9.5% reimbursement cut over 5 years, which far exceeds the 1.0%–1.5% annual increases in productivity that are expected of other Medicare providers.

Table 4.

Potential strategies to increase dialysis facility reimbursement and/or decrease costs

| Strategy | Rationale | Barriers | Comparative Effect on Margin | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater use of home dialysis modalities | Lower costs than in-center HD or PD; costs for home HD variable; recent increase in home training fees | Lack of physician champions; payments for the extra HD txs on the basis of medical justification vary by the MACs; if payment for extra txs is denied, there is a loss; some home programs are freestanding, and the in-center HD facility does not get any benefit of the cost-savings, only a loss of new referrals and/or loss of current pts, resulting in empty in-center HD stations until pts switched to home modalities can be replaced; increases the overhead per tx; lack of pt incentive to go home; no family support; loss of support system from staff and other pts in center | Could be significant as the number of home pts grow and in-center census decreases | Need a national coverage decision that provides consistent reimbursement guidelines for extra HD txs; allow providers to educate pts with CKD about modalities; nephrology training programs need more emphasis on home dialysis options to develop more physician champions; provide more education for current nephrologists |

| Greater use of more frequent HD | Pts have trouble with 3-d interdialytic period; may decrease morbidity and mortality from fluid overload and/or hyperkalemia | Providing adequate medical justification to MAC; finding stations to accommodate extra txs | Small; it might increase costs if a Sunday shift was added and not fully used | Should be on the basis of medical need; need a national coverage decision to assure consistent criteria for medical justification |

| Use of SC ESA | Increased efficacy of SC versus IV epoetin | Pt discomfort and decreased satisfaction; applicable only to short-acting ESAs; effect on margin will be lost with next rebasing | Variable; anecdotal evidence does not show percentage dose decreases as large as once thought; doses have decreased because of the Black Box Warning | Not as much a potential cost-saver as when ESA doses were much higher; cost-savings will decrease further when biosimilar ESAs available |

| Decreasing hospital admissions and readmissions | Decreased system costs; fewer empty stations; better pt outcomes | Costs of infrastructure for CM and MTM needed to decrease lost hospital days not covered in payment to dialysis facilities; current staffing is insufficient to provide the oversight to offer better integrated care and manage all transitions | Fewer missed txs will reduce average per tx cost of staff and overhead; cost of additional resources will be greater than the savings | Worth pursuing with whatever funds are available, because it is the right thing to do; the best solution will come with a shared savings model so that resources can be used to provide additional services |

| Innovating operating procedures to increase efficiency | How dialysis providers have responded to reimbursement decreases over the past 40 yr | With less fat in the system, there may be less opportunity without jeopardizing quality and pt safety; staffing productivity is decreasing as the pt tx times increase | Will depend on the degree of process innovation, new technology, vendor competition, and productivity of personnel | QAPI is not just for pt outcomes; it also applies to system processes |

HD, hemodialysis; SC, subcutaneous; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; PD, peritoneal dialysis; pt, patient; IV, intravenous; tx, treatment; MAC, Medicare administrative contractor; CM, care manager; MTM, medication therapy management; QAPI, quality assessment and performance improvement.

New Models of Reimbursement

With the passage of PAMA in 2014, dialysis providers have predictable reimbursement through 2018. The integrity of the bundle must be maintained so that new services and costs are not added without appropriate fiscal allowance (unfunded mandates). The major barriers to success in improving care to patients, improving health to populations, and decreasing costs are the misaligned incentives and siloed payment pools that exist in the current health care delivery model. It is sickness rather than health that is financially rewarded. One approach to these barriers is ESRD seamless care organizations (ESCOs), which are partnerships formed by dialysis facilities, nephrologists, and other Medicare providers (such as vascular access surgeons, hospitalists, home health agencies, palliative care providers, and hospice providers) to promote the alignment of incentives and coordination of patient care that may improve outcomes and decrease overall costs. Cost-savings, whether they come from Medicare Part A or Part B, are shared between Medicare and the participants of ESCO. The Medicare Part A savings that accrue to a dialysis provider in a successful ESCO can be used to fund innovation and offset the thin or negative margins from patients on Medicaid or traditional Medicare. Nonetheless, the innovation benefits all patients. The ESCO incentivizes nephrologists, dialysis providers, and other providers to work collaboratively to improve quality and decrease costs primarily by minimizing hospitalizations. It encourages expansion of the health care team to include vascular surgeons, pharmacists, home health care providers, skilled nursing facilities, palliative care, and hospice care. It also challenges nephrologists and dialysis providers to seek innovative ways to increase patient and caregiver engagement. It requires more effective ways to communicate meaningful health care information in a Health Insurance Accountability and Portability Act-compliant system so that all stakeholders have access to the most current records. The infrastructure required to achieve these goals is expensive, and the shared savings from the ESCO must be substantial enough to justify the investment. Although nephrology fee-for-service income may decrease because of decreased hospitalizations, overall nephrologist income may rise because of the shared savings distribution. The aligned incentives for cost-savings in an ESCO should extend to improve the care for patients with advanced CKD. For example, timely placement of permanent vascular access before hemodialysis initiation will decrease the cost of care after hemodialysis initiation and thereby incentivize the participating nephrologists to improve their education and vascular access referral of patients before dialysis.

ESCOs are not a solution to reimbursement challenges for all dialysis providers. They require significant upfront investment in care coordination personnel and data infrastructure that may not available to small providers. However, ESCOs are accessible to more providers than the ESRD managed care and disease management (MCDM) demonstration projects that were implemented in the late 1990s (13) and late 2000s (14), which also attempted to promote coordination of care and decrease hospitalizations through the removal of traditional Medicare Part A and Part B payment silos. The contractors that participated in the MCDM demonstration projects assumed all of the financial risk and received all of the financial reward. Such risks could be assumed only by large health plans and LDOs. Because ESCOs are shared savings programs, the risk (and reward) are significantly less and within reach of many non-LDO dialysis companies. It is notable the late 1990s MCDM project was unable to show any significant improvements in quality or cost-savings over the comparator Medicare fee-for-service population, except for a decrease in hospitalizations among a subset of high-risk patients (13). This MCDM demonstration project was run top-down by health plans and may not be comparable with ESCOs, which will be run bottom up by dialysis providers, nephrologists, and other providers who all have skin in the game. The MCDM project in the late 2000s showed higher survival but also higher costs over the comparator Medicare fee-for-service population during the first 3 years of the 5-year project (14). Contractors for this project were disease management organizations affiliated with LDOs. Whether the dialysis provider–based shared savings ESCO model will have greater success with cost-savings and improved outcomes remains to be seen. However, ESCOs are a continuation of the expanding bundle model that has promoted efficiency in the dialysis industry since it was first funded by Medicare in 1972. ESRD payment was, in essence, the first diagnostic-related group-like payment (i.e., flat payment no matter what the underlying cost), which provided huge incentives for efficiency. ESCOs further expand this payment bundle to all related services that can contribute to higher quality (e.g., vascular access, quality of life, and experience of care) and lower costs (e.g., hospital admissions, emergency room visits, physician services, drugs, and other Medicare services) both directly ESRD-related and unrelated but falling in the covered time period.

Summary and Conclusions

The cumulative 9.5% reduction in payment between 2014 and 2018 will be very challenging to most dialysis providers, which operate at margins that average 3%–4%. The required increase in productivity to offset this reduction is much greater than what is achieved in the rest of the economy. One can argue that the closure of the least economically viable facilities and increased consolidation of the industry are forms of economic Darwinism that should be allowed to run its course. However, rural and inner-city dialysis providers may have greater financial challenges on the basis of payer mix, but they are important to preserve patient access to care. Competition benefits patients by stimulating innovative approaches to care that improve outcomes and decrease costs. Innovation requires risk-taking and resources, which are increasingly scarce in this model of dialysis reimbursement. The major barrier to achieving CMS’s Triple Aim is that the health care system is fundamentally broken by rewarding sickness rather than health. Integrated health care delivery systems, such as ESCOs, offer the potential to fix the system by aligning incentives, rewarding good outcomes through shared savings, and encouraging dialysis providers and nephrologists to allocate resources appropriately not because it pays now but because it saves later. Moving away from the dialysis treatment bundled payment model to a shared savings model removes the vulnerability of the industry to percentage point adjustments in the Medicare fee schedule, such as with rebasing, and encourages every provider to determine its own fate through innovation.

Disclosures

D.W. is President and Chief Executive Officer of Centers for Dialysis Care, Inc., a regional nonprofit dialysis provider in northeast Ohio; past president of the National Renal Administrators Association; and on the boards of Kidney Care Partners, Kidney Care Council, Nonprofit Kidney Care Alliance, and Renal Services Exchange. D.J. is Vice Chair of the Board for Dialysis Clinic, Inc., a national nonprofit dialysis provider based in Nashville, TN; a member of Kidney Care Partners and Nonprofit Kidney Care Alliance; treasurer of Kidney Care Council; and on the board of Renal Services Exchange. J.W. is medical director of the nonprofit outpatient dialysis unit at Indiana University Hospital and a consultant to DaVita on quality of care.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.US Government Accountability Office: End-Stage Renal Disease: Reduction in Drug Utilization Suggests Bundled Payment Is Too High. Report GAO-13-190R, 2012. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/assets/660/650667.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2014

- 2.Whoriskey P: Anemia Drug Made Millions, but at What Cost? Washington Post, July 19, 2012. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/anemia-drug-made-billions-but-at-what-cost/2012/07/19/gJQAX5yqwW_story.html. Accessed April 14, 2014

- 3.Hahn J: Medicare, Medicaid and Other Health Provisions in the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012. Congressional Research Service, January 31, 2013. Available at: http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42944.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2014

- 4.MedPAC: A Data Book: Healthcare Spending and the Medicare Program (June 2013), Chapter 11, Other Services: Dialysis, Hospice, Clinical Laboratory. Available at: http://medpac.gov/chapters/Jun13DataBookSec11.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2014

- 5. Kidney Care Partners: Comment on the ESRD PPS for CY 2014, August 29, 2013. Available at: http://kidneycarepartners.com/media-center/attach/98-1.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2014.

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS: Medicare Program: End-stage renal disease prospective payment system, quality incentive program, and durable medical equipment, prosthetics, orthotics, and supplies; final rule. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 42 CFR Parts 413 and 414. Fed Regist 78: 72155–72253, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.H.R. 4302. Available at: http://beta.congress.gov/113/bills/hr4302/BILLS-113hr4302enr.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2014

- 8.US Renal Data System: USRDS 2013 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2013, p 372 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devereaux PJ, Schünemann HJ, Ravindran N, Bhandari M, Garg AX, Choi PT, Grant BJ, Haines T, Lacchetti C, Weaver B, Lavis JN, Cook DJ, Haslam DR, Sullivan T, Guyatt GH: Comparison of mortality between private for-profit and private not-for-profit hemodialysis centers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 288: 2449–2457, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garg PP, Frick KD, Diener-West M, Powe NR: Effect of the ownership of dialysis facilities on patients’ survival and referral for transplantation. N Engl J Med 341: 1653–1660, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berwick DM, Nolan DW, Whittington J: Triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Aff 27: 759–769, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Renal Data System: USRDS 2013 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2013, p 326 [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Lewin Group: Final Report on the Evaluation of CMS’s ESRD Managed Care Demonstration, June 2002. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Demonstration-Projects/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/downloads/ESRD_Managed_Care_Evaluation_Results.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2014

- 14.Arbor Research Collaborative for Health: End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Disease Management Demonstration Evaluation Report: Findings from 2006-2008, the First Three Years of a Five-Year Demonstration, December 2010. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Reports/downloads/Arbor_ESRD_EvalReport_2010.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2014