Abstract

Background and objectives

Kidney stones are heterogeneous but often grouped together. The potential effects of patient demographics and calendar month (season) on stone composition are not widely appreciated.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

The first stone submitted by patients for analysis to the Mayo Clinic Metals Laboratory during 2010 was studied (n=43,545). Stones were classified in the following order: any struvite, any cystine, any uric acid, any brushite, majority (≥50%) calcium oxalate, or majority (≥50%) hydroxyapatite.

Results

Calcium oxalate (67%) was the most common followed by hydroxyapatite (16%), uric acid (8%), struvite (3%), brushite (0.9%), and cystine (0.35%). Men accounted for more stone submissions (58%) than women. However, women submitted more stones than men between the ages of 10–19 (63%) and 20–29 (62%) years. Women submitted the majority of hydroxyapatite (65%) and struvite (65%) stones, whereas men submitted the majority of calcium oxalate (64%) and uric acid (72%) stones (P<0.001). Although calcium oxalate stones were the most common type of stone overall, hydroxyapatite stones were the second most common before age 55 years, whereas uric acid stones were the second most common after age 55 years. More calcium oxalate and uric acid stones were submitted in the summer months (July and August; P<0.001), whereas the season did not influence other stone types.

Conclusions

It is well known that calcium oxalate stones are the most common stone type. However, age and sex have a marked influence on the type of stone formed. The higher number of stones submitted by women compared with men between the ages of 10 and 29 years old and the change in composition among the elderly favoring uric acid have not been widely appreciated. These data also suggest increases in stone risk during the summer, although this is restricted to calcium oxalate and uric acid stones.

Keywords: calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, infrared spectroscopy, struvite, uric acid

Introduction

The prevalence of kidney stone disease seems to be rising in the United States. The reasons for this trend are not entirely clear. Factors such as obesity, diabetes, and diet have all been implicated. On the basis of a previous series from referral stone laboratories, it is commonly stated that the vast majority (approximately 80%) of kidney stones that form in adults contain a majority of calcium oxalate (CaOx) and/or calcium phosphate in the form of hydroxyapatite (HA) (1–3). Other less common stone compositions include uric acid (UA), struvite (ST; magnesium ammonium phosphate), and cystine (Cy).

The Mayo Clinic Metals Laboratory performs compositional analysis of close to 50,000 kidney stones per year by infrared spectroscopy on samples submitted from across the United States. In this study, we examined the distribution of stone types to determine if previous reports regarding the distribution of stone composition applied to this relatively large cohort in 2010. Because this sample includes comparable numbers of men and women of diverse ages, we also examined the effects of demographics and calendar month (season) on stone composition. Results suggest that the aggregate percentages are similar to those previously reported. However, age and sex both influence the distribution of stone type in important ways. Finally, certain stone types are more commonly submitted in warm summer months (CaOx and UA), whereas the others did not show this seasonal trend.

Materials and Methods

Stone Analyses

Kidney stone samples were predominantly referred to the Mayo Clinic Metals Laboratory for analysis by community hospitals representing community practices ranging from urologists to general medicine. It is likely (but no data are available) that most of stones submitted were referred from specialty practice. The laboratory did not receive information describing medications or whether stones were passed or collected at time of intervention. All stones were analyzed in the Mayo Clinic Metals Laboratory using their standard operating procedure. Initially, each stone was weighed before a representative specimen (approximately 1 mg) was taken from all identifiable layers. The specimen was then crushed into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle, and an infrared spectrum was recorded using a Frontier FTIR Spectrometer with the Universal ATR Sampling Accessory and a diamond/ZnSe crystal (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The resulting spectrum was compared against a reference spectrum of all known kidney stone components, allowing for accurate analysis of complex crystal mixtures of each crystal type (4). The percentage of constituents was determined by comparing the ratio of peak heights of the constituents within a given sample to the ratio of peak heights in a library of known quantities of mixed constituents. This is currently considered the gold standard method for routine clinical analysis of stone composition (5).

Stone Classification

All stones submitted for analysis to the Mayo Clinic Metals Laboratory during calendar year 2010 were studied (n=48,446). Only the first stone submitted per person was included in this analysis (n=43,545). Stones were classified in the following sequential order such that each stone was placed in one unique group: (1) stones containing any ST were placed in the ST group; (2) stones containing any Cy were placed in the Cy group; (3) stones containing any UA were placed in the UA group; (4) stones containing any brushite (BR) were placed in the BR group; (5) stones were classified as CaOx if they had a majority (>50%) of CaOx with or without any HA; or (6) stones were classified as HA if they contained a majority (>50%) of HA with or without any CaOx. Stones that were composed of medications, protein, or rare constituents (e.g., dihydroxyadenine) were classified as such, whereas materials unlikely to have an origin in the urinary tract (e.g., silica) were classified as artifact.

Statistical Analyses

Stone compositions of artifact, protein, or medications were shown in the graphs but excluded from the statistical analysis. For monthly trends, all values were normalized to a 30-day month. Each stone composition was compared with all other compositions (e.g., CaOx versus non-CaOx) across sex and age (10-year intervals) groups. The number of each stone composition received per normalized 30-day month was expressed as a percentage of the whole year’s quantity of that stone composition. Chi-squared tests were used to assess the effects of sex, month, and age group on stone type. For monthly trends, the one-sample chi-squared test was used with expected values adjusted for length of the month. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software, version 9.3 and version 9 JMP (SAS Institute, Cary, NC; www.sas.com).

Results

Stones were received from across the United States, including the northeast (6351; 14.6%), mid-Atlantic (4809; 11.0%), southeast (6782; 15.6%), midwest (9237; 21.2%), upper midwest (8237; 18.9%), south central (6111; 14.0%), and western (1968; 4.5%) states. The largest group (67%) contained stones composed mostly of CaOx followed by those composed mostly of HA (16%) (Table 1). Thus, 83.4% of the stones were composed of calcium in the form of CaOx or HA. UA stones comprised another 8%, whereas ST (3%), BR (0.9%), and Cy (0.35%) were less common (Table 1). Of UA stones, 62.7% were pure, whereas the remainder were admixed with CaOx. In total, only 61 stones (0.1%) contained drug metabolites, including triamterene (36 stones), atazanavir (one stone), sulfamethoxazole (six stones), guaifenesin and ephedrine (two stones), phenazopyridine (two stones), and sulfadiazine (one stone). Only one rare stone (dihydroxyadenine) was received during this calendar year. Samples containing only protein were classified as such (0.4%), and samples containing silica or no other clear stone material were classified as artifacts (3.2%). Men and women were both much more likely to submit stones between the ages of 20 and 79 years (Table 2). Overall, men were more likely to submit a stone (58% of the total). However, women accounted for the majority of submitted stones between the ages of 10–19 (63%) and 20–29 (62%) years of age.

Table 1.

Distribution of stone type analyzed during calendar year 2010 (n=43,545)

| Stone Type | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium oxalate | 29,319 | 67.3 |

| Apatite | 7000 | 16.1 |

| Uric acid | 3611 | 8.3 |

| Struvite | 1318 | 3.0 |

| Brushite | 374 | 0.9 |

| Cystine | 151 | 0.35 |

| Ammonium urate | 105 | 0.20 |

| Artifact | 1393 | 3.2 |

| Other | 171 | 0.4 |

| Drug | 60 | 0.1 |

| Sodium/potassium urate | 42 | 0.1 |

| Dihydroxyadenine | 1 | 0.002 |

Only the first stone submitted per individual was included.

Table 2.

Stones submitted for analysis by age and sex

| Age (yr) | Men | Percent | Women | Percent | Ratio of Men to Women Stone Formers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–9 | 73 | 0.3 | 60 | 0.3 | 1.22 (1.05)a |

| 10–19 | 396 | 1.6 | 675 | 3.7 | 0.59b (1.04)a |

| 20–29 | 1588 | 6.3 | 2548 | 13.9 | 0.62b (1.03)a |

| 30–39 | 3229 | 12.8 | 3331 | 18.1 | 0.97 (0.99)a |

| 40–49 | 4884 | 19.4 | 3369 | 18.4 | 1.45b (0.97)a |

| 50–59 | 6160 | 24.5 | 3724 | 20.3 | 1.65b (0.95)a |

| 60–69 | 5300 | 21.0 | 2765 | 15.1 | 1.92b (0.89)a |

| 70–79 | 2653 | 10.5 | 1267 | 6.9 | 2.09b (0.78)a |

| 80–89 | 846 | 3.4 | 552 | 3.0 | 1.53b (0.63)a |

| 90+ | 62 | 0.2 | 63 | 0.3 | 0.98b (0.63)a |

| Total | 25,191 | 100.0 | 18,354 | 100.0 | 1.37b (0.97)a |

Values represent the men-to-women ratio for each age group in the 2010 United States census (age 80 and above combined).

P<0.05 for comparison of the sex ratio of stones submitted versus the sex ratio in the 2010 United States census.

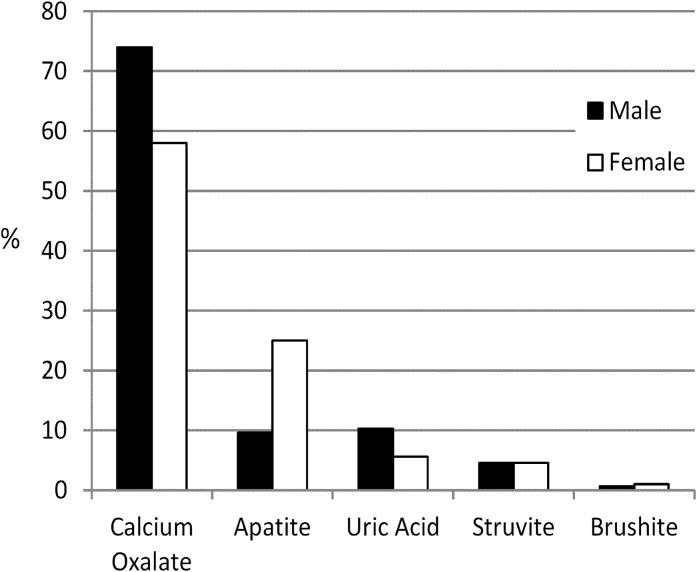

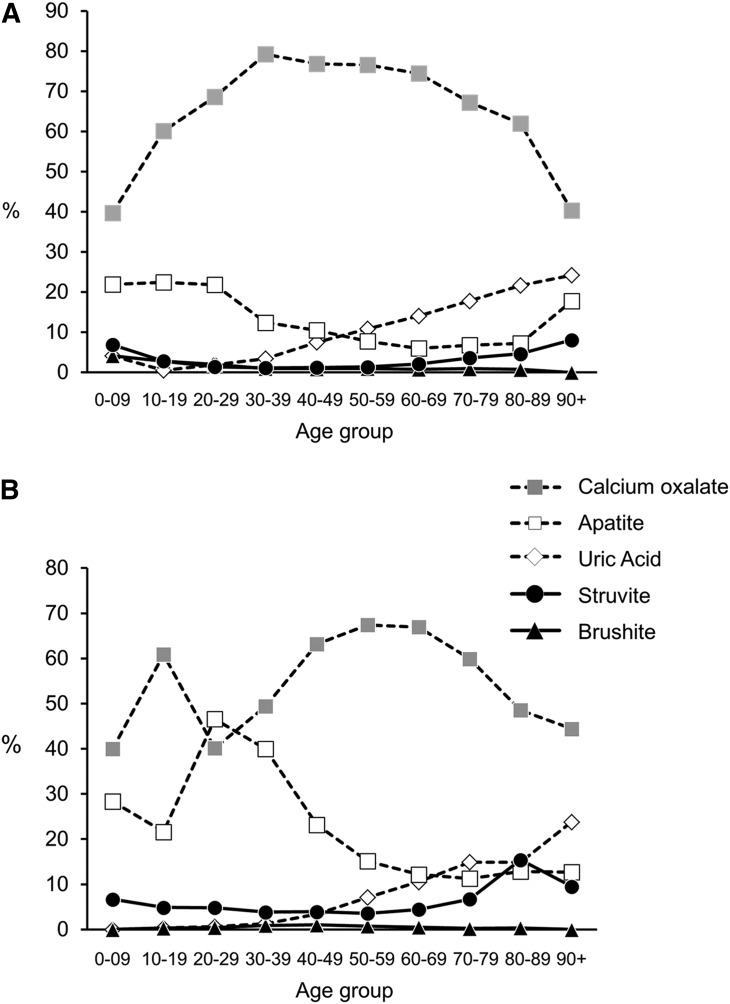

Stone type varied by sex (Figure 1). More women than men were likely to submit an HA (25.0% versus 9.6%) or ST (4.6% versus 1.8%) stone, whereas men were more likely to submit a CaOx (74.1% versus 58.1%) or UA (10.3% versus 5.5%) stone (P<0.001 for all). Although CaOx stones were most common in all age groups, there were striking age trends in relation to the proportional mix of stone type, with HA stones being relatively more common among those 20–29 years old, CaOx stones being relatively more common among those 40–70 years old, and UA stones being relatively more common among those 70+ years old (P<0.001) (Figure 2). General trends by age were similar between the two sexes, although there were some important differences (Figure 3). HA stones were most commonly observed in individuals <40 years old; however, this finding was more marked for women than men. Indeed, the percentage of HA stones was even greater than the percentage of CaOx stones for women between the ages of 20 and 29 years of age (the only instance where CaOx was not the most common stone type). The percentage of UA stones increased dramatically in both sexes after approximately age 50 years, comprising >20% of stones in those >90 years old. In general, the sex differences in stone composition were much less prominent over age 70 years and most marked under age 30 years.

Figure 1.

Association of sex with stone type.

Figure 2.

Association of age with stone type.

Figure 3.

Combined association of age and sex with stone type. (A) Men and (B) women are depicted separately.

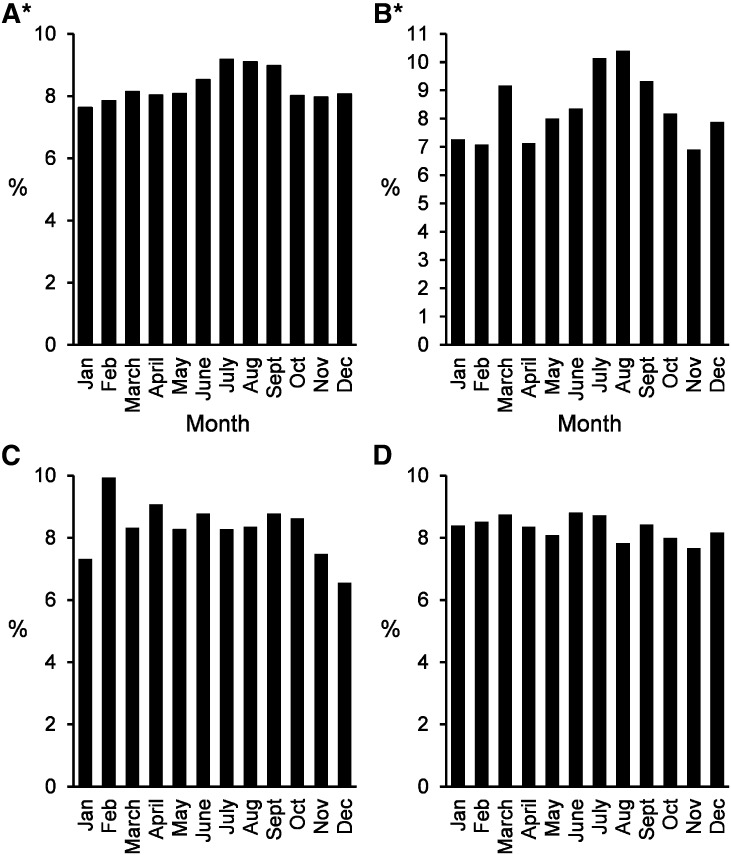

Finally, there were subtle increases in the percentage of CaOx and UA stones submitted in the summertime (July to September) compared with the rest of the year (Figure 4, A and B) (P<0.001 for trend). However, submission of other more common stone types, including HA and ST, did not vary by the calendar month (Figure 4, C and D). Monthly patterns within stone types did not vary significantly by sex. No significant regional differences in the seasonality patterns were seen for UA (P=0.96) or CaOx (P=0.34). Thus, the seasonal trends in these two stone types did not seem to vary significantly by area of the country.

Figure 4.

Association of calendar month with stone numbers submitted. Submissions by month are depicted for four major stone types: (A) calcium oxalate, (B) uric acid, (C) struvite, and (D) apatite. *P<0.001 for evidence of seasonality for a given stone type using a chi-squared test with 11 degrees of freedom.

Discussion

Our study identified important demographic and seasonal features that are associated with the type of stone that a given patient is likely to form. Younger women are more susceptible to HA stones, whereas UA stone composition increases markedly in both sexes after the age of 50 years. CaOx stones are the most common stones across the age and sex spectra, but they are particularly common in middle-aged men. Finally, this study suggests that the warmer summer weather increases the risk to pass certain types of stones (CaOx and UA) but not others (HA and ST).

This study is consistent with a historical series from other large referral laboratories that reported that about 80% of stones are composed of CaOx and/or HA (1–3). The most recent large series of a central laboratory for Veterans Administration facilities across the United States (6) found several important trends, including an increasing likelihood of calcium phosphate stones in a given individual as the number of stone events increased (6). However, this study sampled mostly men (98%), and the data were not stratified by age. Importantly, our data do suggest an increasing proportion of apatite and decreasing proportion of CaOx stones in the elderly, which is consistent with these prior findings of a shift toward apatite stones with time. Men are at higher risk for kidney stones overall (7), possibly because of a greater tendency for urine that is oversaturated for CaOx (8) and diet tendencies that raise CaOx supersaturations (e.g., higher protein intake in men [9]). In one report, the urinary supersaturation for both CaOx and UA increased in men during warmer months, whereas these levels remained relatively flat across seasons for women (10). We found that women were particularly more likely than men to have HA stones. Perhaps related, women stone formers are at increased risk of urinary tract infection (11), which in turn, could raise urinary pH from infection with organisms that contain urease and favor HA supersaturations. Overall, this study highlights that the factors that drive stone formation in younger women likely differ the factors that drive stone formation in the older and more common stone formers (men).

Other published data also support the idea that HA stones are more common in women than men and that the average amount of calcium phosphate in mixed CaOx stones is increasing over recent decades (12). In this prior study from a large referral stone clinic, calcium phosphate stones began at a younger age (29.8 years) than CaOx stones (33.6 years), and they were associated with a relatively higher urinary pH and calcium excretion (12). In a separate report from the same referral stone clinic, urine pH was also noted to be higher in a group of both men and women who transformed from CaOx to calcium phosphate (13). Hormonal status might play some role in the observed sex differences in stone composition. Older women, likely to be postmenopausal (i.e., above age 50 years), have stone compositions quite similar to men of the same age. Analysis of two large cohorts of women suggests that kidney stone risk may increase after menopause (14,15). In general, younger women have been observed to have higher urinary pH and citrate, lower urinary calcium, and higher calcium phosphate supersaturation. However, postmenopause urinary calcium tends to rise (16,17). In two studies, urinary pH and citrate both tended to be higher in postmenopausal women on estrogen replacement than women not on estrogen replacement (16,17). These observations suggest that postmenopausal changes make older women more similar to men in their risk of stones, and this may explain the lack of sex differences in stone composition in the older age ranges.

Our data also show that UA stones become increasingly common with age >50 years old in both sexes. Indeed, by age 90 years, UA stones are almost as common as CaOx stones. Two large stone analysis laboratories in Germany (18) and France (19) have reported a similar trend toward formation of UA stones in the elderly, and population-based data from Olmsted County, Minnesota (20) reported similar findings. Possibly, this observation has to do with changes in kidney function associated with aging. CKD is often associated with type 4 renal tubular acidosis, which in turn, is characterized by decreased renal ammoniagenesis and more acidic urine (21) that favors UA supersaturation (22). Furthermore, urinary calcium excretion is reduced among those with declining GFR, perhaps making calcium stones less likely (23). Obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes, which are also more common with aging, are associated with lower urinary pH and UA stones (24,25).

It has been widely accepted that kidney stones are more common among adult men. Our data suggest that, not only is the composition of stones different in younger women, containing relatively more HA, but the number formed is also greater among adolescent girls (10–19 years old) and young adult women (20–29 years old) as opposed to men. In this current study, women accounted for about 60% of submitted stones between 10 and 29 years of age. Several larger cohorts of stone-forming adolescents also found a preponderance of women in this age group (26,27), and analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data between 1976 and 1994 suggested that 20- to 29-year-old women had an approximately 50% higher prevalence of stones than men of the same age (28). Thus, the weight of evidence suggests that more research is needed to understand the factor(s) that mediate kidney stone risk in younger women and that these factors likely differ from those in older men (and perhaps, older women).

Finally, our data suggest that the environment has effects on certain stone types, but perhaps not others. Patients were more likely to submit a CaOx or UA stone during the summer months. Increased urinary concentration because of insensible water loss in warm weather will increase urinary supersaturations for both UA and CaOx. Alternatively, other stone compositions did not vary with calendar month. ST stones are caused by infection with a urease-positive organism, and one might speculate that seasonal effects on urinary concentration would be less important. For apatite and BR stone compositions, increased urinary pH has the dominant effect to increase calcium phosphate supersaturations as opposed to urinary concentrations of calcium and phosphate (29). The effect of aggressive hydration in settings where patients are prone to concentrating their urine (e.g., warm summer) might be less beneficial for calcium phosphate or ST stones compared with CaOx or UA.

This study has potential weaknesses. No clinical data are available for these individuals other than age, sex, and the referral site submitting the stone. Thus, we are not able to separate first time versus recurrent stones or compare stone composition with the number of stone events. There is no clear denominator (catchment population) for these data to determine the prevalence of each stone composition. Nevertheless, the very large number of stones available for this study allowed us to detect clear trends in the case mix of stone composition, which suggest important age, sex, and seasonal effects.

In conclusion, most of stones formed in the United States are CaOx followed by HA. Together, CaOx and HA account for over 80% of stones submitted to a large referral laboratory. However, demographics have significant associations with the likelihood of forming a given stone type. Younger women are more susceptible to HA stones. Men of all ages are particularly susceptible to CaOx stones. Older individuals of both sexes make progressively more UA stones.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Mayo Clinic O’Brien Urology Research Center Grant U54-DK100227, Rare Kidney Stone Consortium Grant U54-KD083908, a member of the National Institutes of Health Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and the Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Mandel NS, Mandel GS: Urinary tract stone disease in the United States veteran population. II. Geographical analysis of variations in composition. J Urol 142: 1516–1521, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herring LC: Observations on the analysis of ten thousand urinary calculi. J Urol 88: 545–562, 1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prien EL: Studies in urolithiasis. III. Physicochemical principles in stone formation and prevention. J Urol 73: 627–652, 1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García Alvarez JL, Torrejón Martínez MJ, Arroyo Fernández M: Development of a method for the quantitative analysis of urinary stones, formed by a mixture of two components, using infrared spectroscopy. Clin Biochem 45: 582–587, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schubert G: Stone analysis. Urol Res 34: 146–150, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandel N, Mandel I, Fryjoff K, Rejniak T, Mandel G: Conversion of calcium oxalate to calcium phosphate with recurrent stone episodes. J Urol 169: 2026–2029, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieske JC, Peña de la Vega LS, Slezak JM, Bergstralh EJ, Leibson CL, Ho KL, Gettman MT: Renal stone epidemiology in Rochester, Minnesota: An update. Kidney Int 69: 760–764, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parks JH, Coward M, Coe FL: Correspondence between stone composition and urine supersaturation in nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int 51: 894–900, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borghi L, Schianchi T, Meschi T, Guerra A, Allegri F, Maggiore U, Novarini A: Comparison of two diets for the prevention of recurrent stones in idiopathic hypercalciuria. N Engl J Med 346: 77–84, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parks JH, Barsky R, Coe FL: Gender differences in seasonal variation of urine stone risk factors. J Urol 170: 384–388, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parks JH, Coe FL, Strauss AL: Calcium nephrolithiasis and medullary sponge kidney in women. N Engl J Med 306: 1088–1091, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parks JH, Worcester EM, Coe FL, Evan AP, Lingeman JE: Clinical implications of abundant calcium phosphate in routinely analyzed kidney stones. Kidney Int 66: 777–785, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parks JH, Coe FL, Evan AP, Worcester EM: Urine pH in renal calcium stone formers who do and do not increase stone phosphate content with time. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 130–136, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maalouf NM, Sato AH, Welch BJ, Howard BV, Cochrane BB, Sakhaee K, Robbins JA: Postmenopausal hormone use and the risk of nephrolithiasis: Results from the Women’s Health Initiative hormone therapy trials. Arch Intern Med 170: 1678–1685, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattix Kramer HJ, Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC: Menopause and postmenopausal hormone use and risk of incident kidney stones. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1272–1277, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dey J, Creighton A, Lindberg JS, Fuselier HA, Kok DJ, Cole FE, Hamm L: Estrogen replacement increased the citrate and calcium excretion rates in postmenopausal women with recurrent urolithiasis. J Urol 167: 169–171, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heller HJ, Sakhaee K, Moe OW, Pak CY: Etiological role of estrogen status in renal stone formation. J Urol 168: 1923–1927, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knoll T, Schubert AB, Fahlenkamp D, Leusmann DB, Wendt-Nordahl G, Schubert G: Urolithiasis through the ages: Data on more than 200,000 urinary stone analyses. J Urol 185: 1304–1311, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daudon M, Doré JC, Jungers P, Lacour B: Changes in stone composition according to age and gender of patients: A multivariate epidemiological approach. Urol Res 32: 241–247, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krambeck AE, Lieske JC, Li X, Bergstralh EJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rule AD: Effect of age on the clinical presentation of incident symptomatic urolithiasis in the general population. J Urol 189: 158–164, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lush DJ, King JA, Fray JC: Pathophysiology of low renin syndromes: Sites of renal renin secretory impairment and prorenin overexpression. Kidney Int 43: 983–999, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurtz I, Dass PD, Cramer S: The importance of renal ammonia metabolism to whole body acid-base balance: A reanalysis of the pathophysiology of renal tubular acidosis. Miner Electrolyte Metab 16: 331–340, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viaene L, Meijers BK, Vanrenterghem Y, Evenepoel P: Evidence in favor of a severely impaired net intestinal calcium absorption in patients with (early-stage) chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 35: 434–441, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maalouf NM, Sakhaee K, Parks JH, Coe FL, Adams-Huet B, Pak CY: Association of urinary pH with body weight in nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int 65: 1422–1425, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abate N, Chandalia M, Cabo-Chan AV, Jr., Moe OW, Sakhaee K: The metabolic syndrome and uric acid nephrolithiasis: Novel features of renal manifestation of insulin resistance. Kidney Int 65: 386–392, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novak TE, Lakshmanan Y, Trock BJ, Gearhart JP, Matlaga BR: Sex prevalence of pediatric kidney stone disease in the United States: An epidemiologic investigation. Urology 74: 104–107, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Routh JC, Graham DA, Nelson CP: Epidemiological trends in pediatric urolithiasis at United States freestanding pediatric hospitals. J Urol 184: 1100–1104, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, Nyberg LM, Curhan GC: Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976-1994. Kidney Int 63: 1817–1823, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiselius HG: A simplified estimate of the ion-activity product of calcium phosphate in urine. Eur Urol 10: 191–195, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]