Abstract

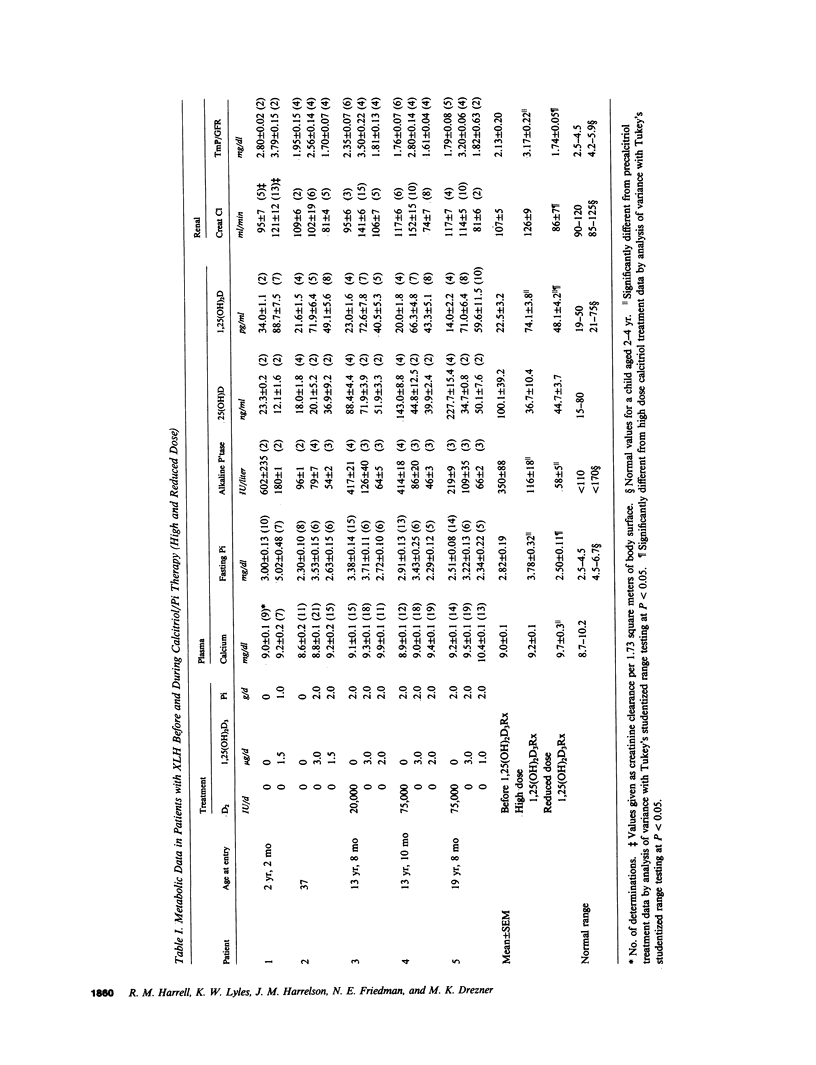

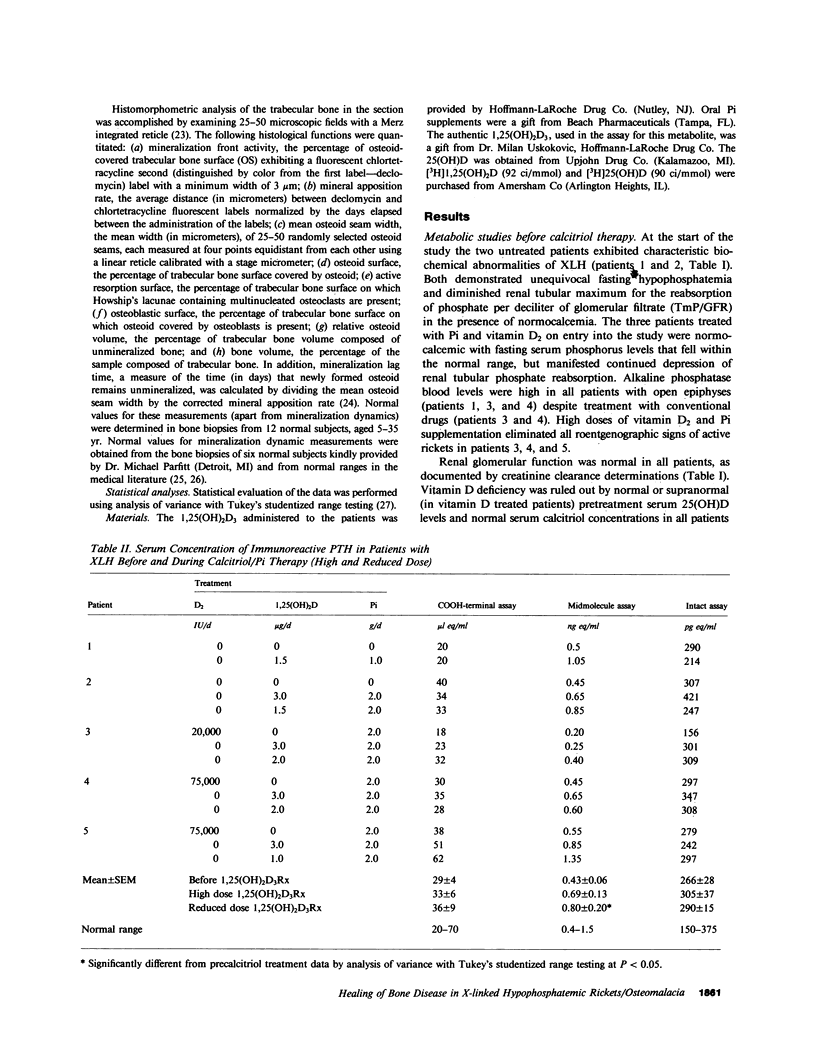

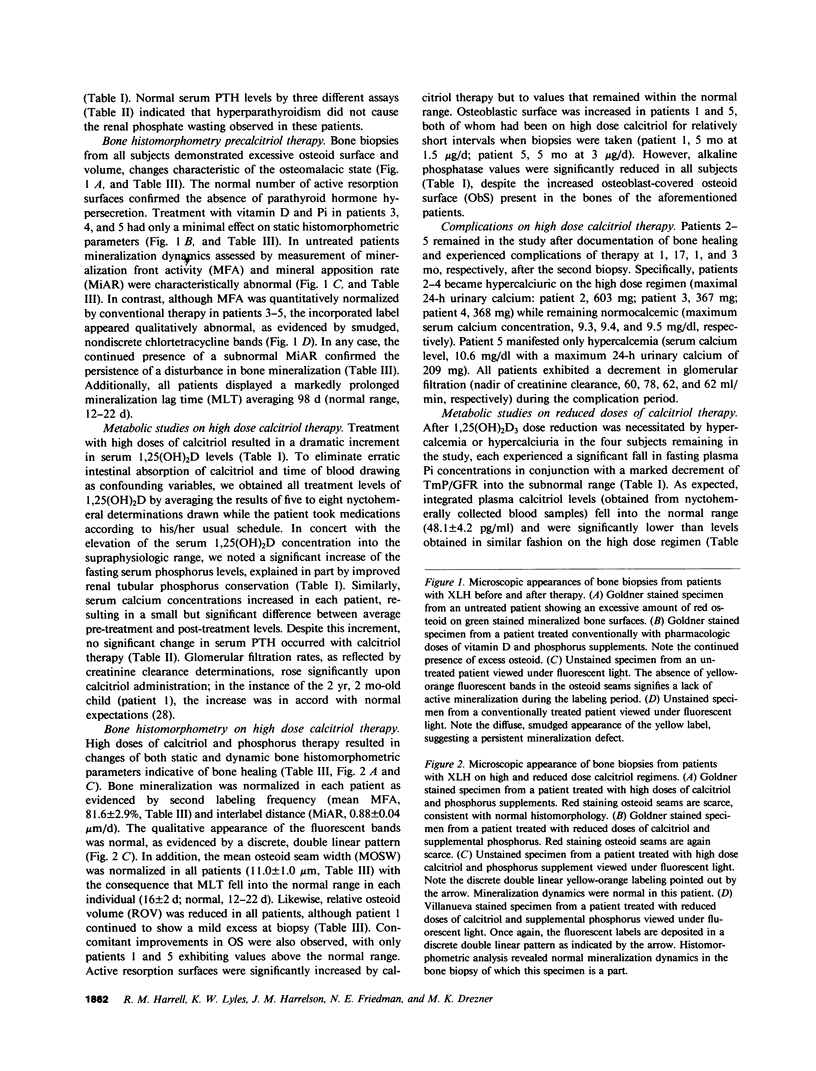

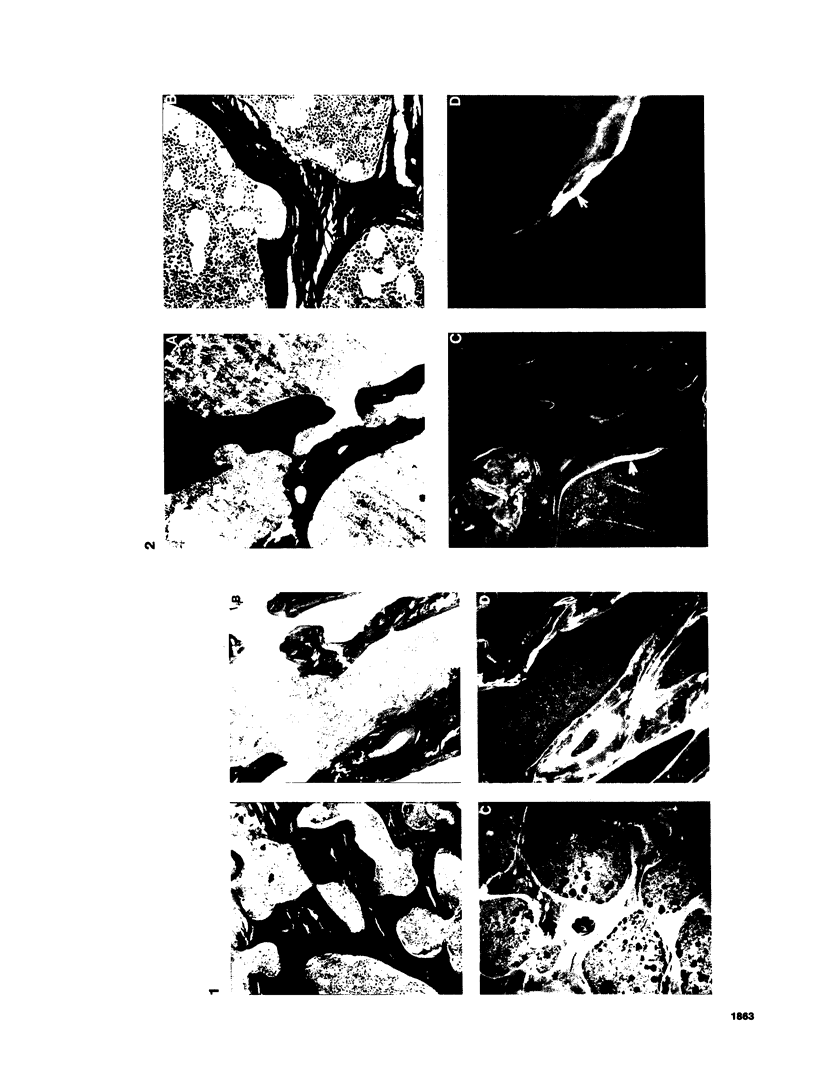

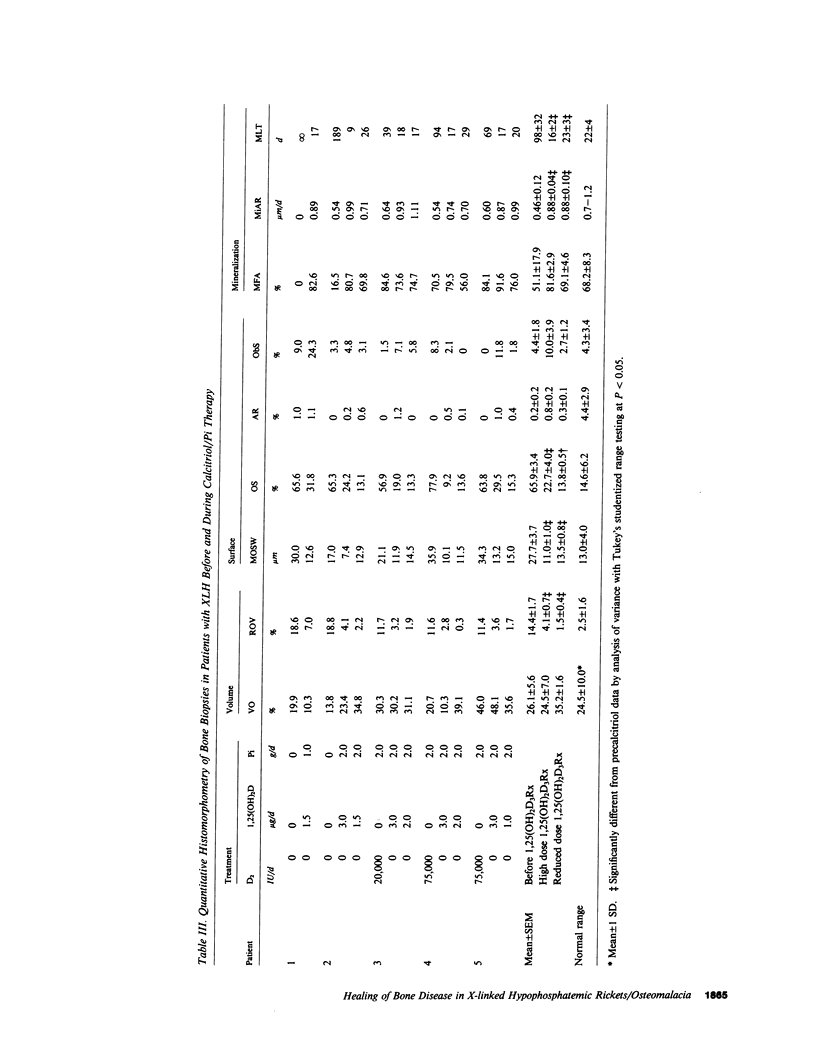

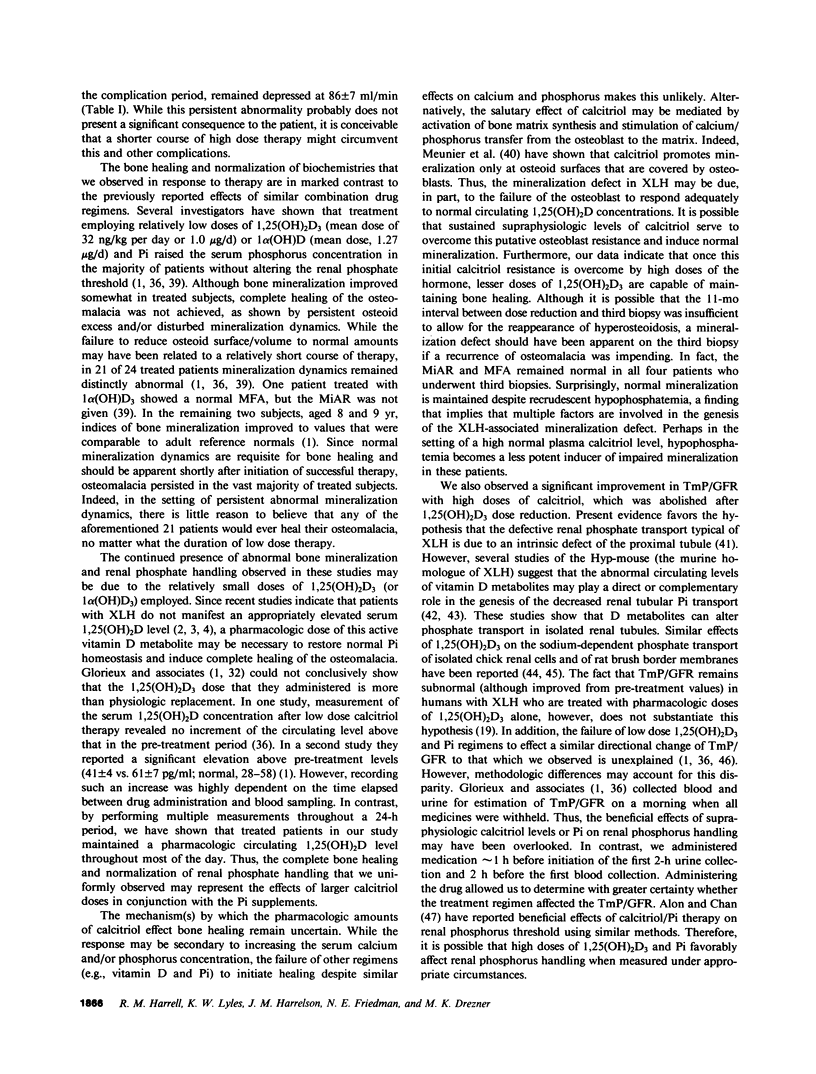

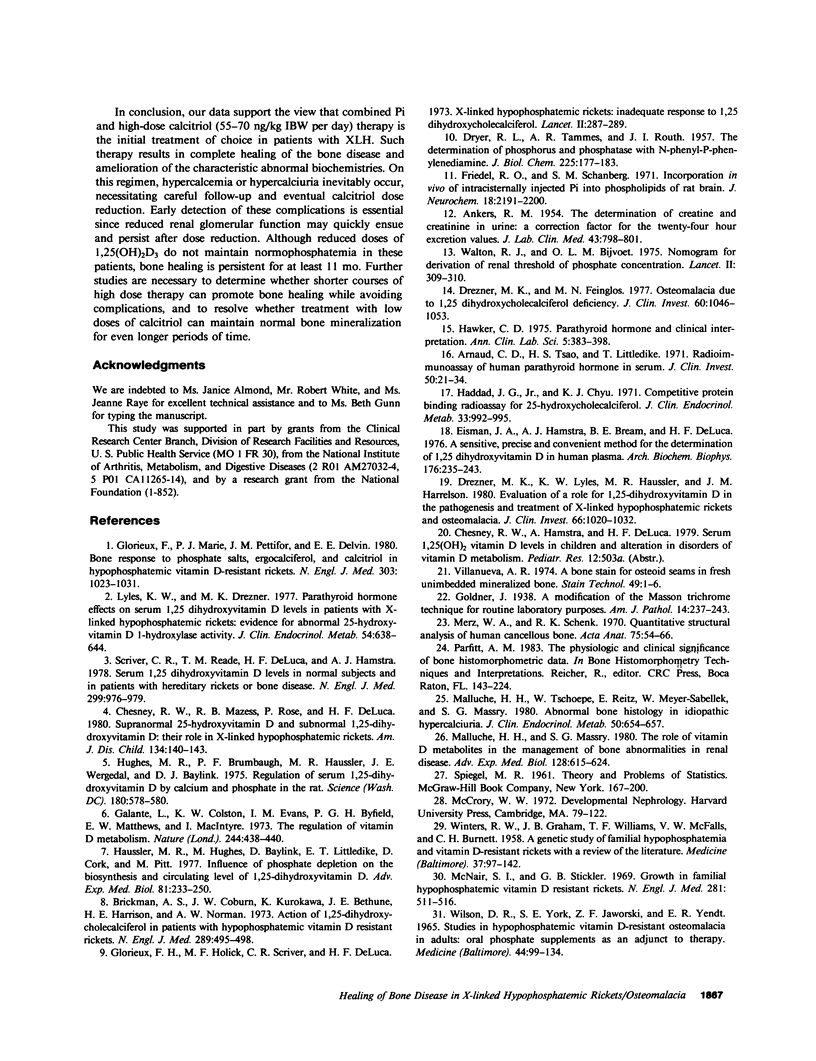

Although conventional therapy (pharmacologic doses of vitamin D and phosphorus supplementation) is usually successful in healing the rachitic bone lesion in patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets, it does not heal the coexistent osteomalacia. Because serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels are inappropriately low in these patients and high calcitriol concentrations may be required to heal the osteomalacia, we chose to treat five affected subjects with high doses of calcitriol (68.2 +/- 10.0 ng/kg total body weight/d) and supplemental phosphorus (1-2 g/d) performing metabolic studies and bone biopsies before and after 5-8 mo of this therapy in each individual. Of these five patients, three (aged 13, 13, and 19 yr) were receiving conventional treatment at the inception of the study and therefore showed base-line serum phosphorus concentrations within the normal range. The remaining two untreated patients (aged 2 and 37 yr) displayed characteristic hypophosphatemia before calcitriol therapy. All five patients demonstrated serum calcitriol levels in the low normal range (22.5 +/- 3.2 pg/ml), impaired renal phosphorus conservation (tubular maximum for the reabsorption of phosphate per deciliter of glomerular filtrate, 2.13 +/- 0.20 mg/dl), and osteomalacia on bone biopsy (relative osteoid volume, 14.4 +/- 1.7%; mean osteoid seam width, 27.7 +/- 3.7 micron; mineral apposition rate, 0.46 +/- 0.12 micron/d). On high doses of calcitriol, serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels rose into the supraphysiologic range (74.1 +/- 3.8 pg/ml) with an associated increment in the serum phosphorus concentration (2.82 +/- 0.19 to 3.78 +/- 0.32 mg/dl) and improvement of the renal tubular maximum for phosphate reabsorption (3.17 +/- 0.22 mg/dl). The serum calcium rose in each patient while the immunoactive parathyroid hormone concentration measured by three different assays remained within the normal range. Most importantly, repeat bone biopsies showed that high doses of calcitriol and phosphorus supplements had reversed the mineralization defect in all patients (mineral apposition rate, 0.88 +/- 0.04 micron/d) and consequently reduced parameters of bone osteoid content to normal (relative osteoid volume, 4.1 +/- 0.7%; mean osteoid seam width, 11.0 +/- 1.0 micron). Complications (hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria) ensued in four of these five patients within 1-17 mo of documented bone healing, necessitating reduction of calcitriol doses to a mean of 1.6 +/- 0.2 micrograms/d (28 +/- 4 ng/kg ideal body weight per day). At follow-up bone biopsy, these four subjects continued to manifest normal bone mineralization dynamics (mineral apposition rate, 0.88 +/-0.10 micrometer/d) on reduced doses of 1.25-dihydroxyvitamin D with phosphorus supplements (2 g/d) for a mean of 21.3 +/- 1.3 mo after bone healing was first documented. Static histomorphometric parameters also remained normal (relative osteoid volume, 1.5 +/- 0.4%; mean osteoid seam width, 13.5 +/- 0.8 micrometer). These data indicate that administration of supraphysiologic amounts of calcitriol, in conjunction with oral phosphorus, results in complete healing of vitamin D resistant osteomalacia in patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. Although complications predictably require calcitriol dose reductions once healing is achieved, continued bone healing can be maintained for up to 1 yr with lower doses of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and continued phosphorus supplementation.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ANKER R. M. The determination of creatine and creatinine in urine; a correction factor for the determination of twenty-four-hour urinary excretion values. J Lab Clin Med. 1954 May;43(5):798–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon U., Chan J. C. Effects of parathyroid hormone and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on tubular handling of phosphate in hypophosphatemic rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984 Apr;58(4):671–675. doi: 10.1210/jcem-58-4-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud C. D., Tsao H. S., Littledike T. Radioimmunoassay of human parathyroid hormone in serum. J Clin Invest. 1971 Jan;50(1):21–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI106476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman A. S., Coburn J. W., Kurokawa K., Bethune J. E., Harrison H. E., Norman A. W. Actions of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol in patients with hypophosphatemic, vitamin-D-resistant rickets. N Engl J Med. 1973 Sep 6;289(10):495–498. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197309062891002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney R. W., Mazess R. B., Rose P., Hamstra A. J., DeLuca H. F., Breed A. L. Long-term influence of calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D) and supplemental phosphate in X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. Pediatrics. 1983 Apr;71(4):559–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney R. W., Mazess R. B., Rose P., Hamstra A. J., DeLuca H. F. Supranormal 25-hydroxyvitamin D and subnormal 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D: their role in X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. Am J Dis Child. 1980 Feb;134(2):140–143. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1980.02130140014005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa T., Marie P. J., Scriver C. R., Cole D. E., Reade T. M., Nogrady B., Glorieux F. H., Delvin E. E. X-linked hypophosphatemia: effect of calcitriol on renal handling of phosphate, serum phosphate, and bone mineralization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981 Mar;52(3):463–472. doi: 10.1210/jcem-52-3-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRYER R. L., TAMMES A. R., ROUTH J. I. The determination of phosphorus and phosphatase with N-phenyl-p-phenylenediamine. J Biol Chem. 1957 Mar;225(1):177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drezner M. K., Feinglos M. N. Osteomalacia due to 1alpha,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol deficiency. Association with a giant cell tumor of bone. J Clin Invest. 1977 Nov;60(5):1046–1053. doi: 10.1172/JCI108855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drezner M. K., Lyles K. W., Haussler M. R., Harrelson J. M. Evaluation of a role for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in the pathogenesis and treatment of X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets and osteomalacia. J Clin Invest. 1980 Nov;66(5):1020–1032. doi: 10.1172/JCI109930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drezner M. K. The role of abnormal vitamin D metabolism in X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets and osteomalacia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1984;178:399–404. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4808-5_48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisman J. A., Hamstra A. J., Kream B. E., DeLuca H. F. A sensitive, precise, and convenient method for determination of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in human plasma. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1976 Sep;176(1):235–243. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedel R. O., Schanberg S. M. Incorporation in vivo of intracisternally injected 33 P i into phospholipids of rat brain. J Neurochem. 1971 Nov;18(11):2191–2200. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1971.tb05077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galante L., Colston K. W., Evans I. M., Byfield P. G., Matthews E. W., MacIntyre I. The regulation of vitamin D metabolism. Nature. 1973 Aug 17;244(5416):438–440. doi: 10.1038/244438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorieux F. H., Holick M. F., Scriver C. R., DeLuca H. F. X-linked hypophosphataemic rickets: Inadequate therapeutic response to 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. Lancet. 1973 Aug 11;2(7824):287–289. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)90793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorieux F. H., Marie P. J., Pettifor J. M., Delvin E. E. Bone response to phosphate salts, ergocalciferol, and calcitriol in hypophosphatemic vitamin D-resistant rickets. N Engl J Med. 1980 Oct 30;303(18):1023–1031. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010303031802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorieux F. H., Scriver C. R., Reade T. M., Goldman H., Roseborough A. Use of phosphate and vitamin D to prevent dwarfism and rickets in X-linked hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med. 1972 Sep 7;287(10):481–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197209072871003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldner J. A modification of the masson trichrome technique for routine laboratory purposes. Am J Pathol. 1938 Mar;14(2):237–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad J. G., Chyu K. J. Competitive protein-binding radioassay for 25-hydroxycholecalciferol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1971 Dec;33(6):992–995. doi: 10.1210/jcem-33-6-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haussler M., Hughes M., Baylink D., Littledike E. T., Cork D., Pitt M. Influence of phosphate depletion on the biosynthesis and circulating level of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1977;81:233–250. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-4217-5_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker C. D. Parathyroid hormone: radioimmunoassay and clinical interpretation. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1975 Sep-Oct;5(5):383–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. R., Brumbaugh P. F., Hussler M. R., Wergedal J. E., Baylink D. J. Regulation of serum 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 by calcium and phosphate in the rat. Science. 1975 Nov 7;190(4214):578–580. doi: 10.1126/science.1188357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C. T., Barnes J., Balakir R., Cheng L., Sacktor B. In vitro stimulation of phosphate uptake in isolated chick renal cells by 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Jun;79(11):3532–3536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.11.3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles K. W., Drezner M. K. Parathyroid hormone effects on serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels in patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets: evidence for abnormal 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-hydroxylase activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982 Mar;54(3):638–644. doi: 10.1210/jcem-54-3-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles K. W., Harrelson J. M., Drezner M. K. The efficacy of vitamin D2 and oral phosphorus therapy in X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets and osteomalacia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982 Feb;54(2):307–315. doi: 10.1210/jcem-54-2-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malluche H. H., Massry S. G. The role of vitamin D metabolites in the management of bone abnormalities in renal disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1980;128:615–624. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9167-2_63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malluche H. H., Tschoepe W., Ritz E., Meyer-Sabellek W., Massry S. G. Abnormal bone histology in idiopathic hypercalciuria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980 Apr;50(4):654–658. doi: 10.1210/jcem-50-4-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massry S. G., Goldstein D. A. Is calcitriol [1,25(OH)2D3] harmful to renal function? JAMA. 1979 Oct 26;242(17):1875–1876. doi: 10.1001/jama.242.17.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair S. L., Stickler G. B. Growth in familial hypophosphatemic vitamin-D-resistant rickets. N Engl J Med. 1969 Sep 4;281(10):512–516. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196909042811001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz W. A., Schenk R. K. Quantitative structural analysis of human cancellous bone. Acta Anat (Basel) 1970;75(1):54–66. doi: 10.1159/000143440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen H., Pechet M., Anast C., Mazur A., Gertner J., Broadus A. E. Long-term treatment of familial hypophosphatemic rickets with oral phosphate and 1 alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3. J Pediatr. 1981 Jul;99(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80951-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J. J., Holick M. F., De Luca H. F. The role of vitamin D metabolites in bone resorption. Calcif Tissue Res. 1973;12(4):295–301. doi: 10.1007/BF02013742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scriver C. R., Reade T. M., DeLuca H. F., Hamstra A. J. Serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels in normal subjects and in patients with hereditary rickets or bone disease. N Engl J Med. 1978 Nov 2;299(18):976–979. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197811022991803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scriver C. R. Rickets and the pathogenesis of impaired tubular transport of phosphate and other solutes. Am J Med. 1974 Jul;57(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva A. R. A bone stain for osteoid seams in fresh, unembedded, mineralized bone. Stain Technol. 1974 Jan;49(1):1–8. doi: 10.3109/10520297409116928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILSON D. R., YORK S. E., JAWORSKI Z. F., YENDT E. R. STUDIES IN HYPOPHOSPHATEMIC VITAMIN D-REFRACTORY OSTEOMALACIA IN ADULTS. Medicine (Baltimore) 1965 Mar;44:99–134. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINTERS R. W., GRAHAM J. B., WILLIAMS T. F., McFALLS V. W., BURNETT C. H. A genetic study of familial hypophosphatemia and vitamin D resistant rickets with a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1958 May;37(2):97–142. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195805000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton R. J., Bijvoet O. L. Nomogram for derivation of renal threshold phosphate concentration. Lancet. 1975 Aug 16;2(7929):309–310. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92736-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]