Abstract

Background

Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) is the most abundant circulating antiprotease and is a member of the serine protease inhibitor (SERPIN) superfamily. The gene encoding AAT is the highly polymorphic SERPINA1 gene, found at 14q32.1. Mutations in the SERPINA1 gene can lead to AAT deficiency (AATD) which is associated with a substantially increased risk of lung and liver disease. The most common pathogenic AAT variant is Z (Glu342Lys) which causes AAT to misfold and polymerise within hepatocytes and other AAT-producing cells. A group of rare mutations causing AATD, termed Null or Q0, are characterised by a complete absence of AAT in the plasma. While ultra rare, these mutations confer a particularly high risk of emphysema.

Methods

We performed the determination of AAT serum levels by a rate immune nephelometric method or by immune turbidimetry. The phenotype was determined by isoelectric focusing analysis on agarose gel with specific immunological detection. DNA was isolated from whole peripheral blood or dried blood spot (DBS) samples using a commercial extraction kit. The new mutations were identified by sequencing all coding exons (II-V) of the SERPINA1 gene.

Results

We have found eight previously unidentified SERPINA1 Null mutations, named: Q0cork, Q0perugia, Q0brescia, Q0torino, Q0cosenza, Q0pordenone, Q0lampedusa, and Q0dublin . Analysis of clinical characteristics revealed evidence of the recurrence of lung symptoms (dyspnoea, cough) and lung diseases (emphysema, asthma, chronic bronchitis) in M/Null subjects, over 45 years-old, irrespective of smoking.

Conclusions

We have added eight more mutations to the list of SERPINA1 Null alleles. This study underlines that the laboratory diagnosis of AATD is not just a matter of degree, because the precise determination of the deficiency and Null alleles carried by an AATD individual may help to evaluate the risk for the lung disease.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13023-014-0172-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Q0 mutation, Lung diseases, Serpins

Background

Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) is a serine protease inhibitor, encoded by the SERPINA1 gene on the long arm of chromosome 14 at 14q32.1. The gene is comprised of four coding exons (II, III, IV, and V), three untranslated exons (Ia, Ib, and Ic) in the 5′ region and six introns. Following translation, the 24 amino acid signal peptide is removed and the mature polypeptide is a 394 amino acid, 52 kDa glycoprotein with three asparagine-linked carbohydrate side chains [1]. AAT is an acute phase protein produced predominantly by hepatocytes, but AAT synthesis also occurs in mononuclear phagocytes, neutrophils, and airway and intestinal epithelial cells [2]. Consistent with a role as an important acute phase reactant, hepatocytes express approximately 200 times more AAT mRNA than other cells [3] and serum levels rapidly increase several-fold during the acute phase response [4]. The primary function of AAT is the regulation of serine proteases, and the chief site of action is the lungs where it protects the fragile alveolar tissues from proteolytic degradation during inflammatory responses. In addition to its undoubted anti-protease properties, there is accumulating evidence that AAT plays a key anti-inflammatory role [5].

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) (MIM # 613490) is an inherited condition caused by mutations within the polymorphic SERPINA1 gene and is characterised by decreased serum AAT concentrations. AATD is an under-diagnosed condition and the majority of cases remain undiagnosed. The World Health Organisation (WHO), the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) advocate a targeted screening approach for the detection of AATD in at risk populations, specifically chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), non-responsive asthma, cryptogenic liver disease and in first degree relatives of known AATD patients. Over 100 mutations leading to AAT deficiency have been identified to date and are associated with varying degrees of risk for lung and liver disease. AATD is associated with increased risk of cutaneous panniculitis [6] and case reports have linked AATD to vasculitis [7], and Wegener’s granulomatosis [8] with the Z allele over-represented in subsets of ANCA-associated vasculitis [9]. The most common mutations known to cause AATD are the dysfunctional Z (Glu342Lys) and S (Glu264Val) mutations. The Z mutation leads to a severe plasma deficiency and is the most common clinically significant allele. The majority of individuals diagnosed with severe AATD are homozygous for the Z mutation, and have circulating AAT levels reduced to 10-15% of normal. This is because the Z mutation prompts the AAT protein to polymerise and accumulate within the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes, thus causing impaired secretion [10]. The rate of polymer formation for S is much slower than Z AAT, leading to reduced retention of protein within hepatocytes, milder plasma deficiency, and a negligible risk of disease in MS heterozygotes [11,12]. However, there is a risk of lung disease in compound heterozygotes. For example, if the slowly polymerising S variant of AAT is inherited with a rapidly polymerising variant such as Z, the two variants when co-expressed can interact to form heteropolymers, leading to cirrhosis and plasma deficiency [13].

The ultra rare family of SERPINA1 mutations termed silent or Null are characterised by a complete absence of AAT in the plasma. Null (also called Q0) mutations are caused by a variety of different mechanisms including large gene deletions [14], intron mutations [15], nonsense mutations [16], and frameshift mutations [17]. In some cases, Null variants are synthesised in the hepatocytes, but they are rapidly cleared by intracellular degradation pathways [18]. As Null mutations do not induce AAT polymerisation, they confer no risk of liver disease but do confer a particularly high risk of lung disease [19]. The exact prevalence of Null mutations is unclear, and is hampered by a lack of general awareness of AATD and inherent flaws in diagnostic strategies.

We report here eight cases of previously unidentified Null SERPINA1 mutations in the Italian and Irish populations.

Methods

The diagnostic algorithm for diagnosis of AATD was applied as previously reported [20]. The probands were referred to the Italian or Irish National Reference Centres for the Diagnosis of AATD, situated in Pavia and Brescia (Italy), and Dublin (Ireland), respectively. Where possible, relatives were analysed and family trees were created (online Additional file 1). Family members included in the study or their parents gave written informed consent. All procedures were in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committees. Clinical data were obtained from direct observation or medical charts.

AAT measurements were performed by a rate immune nephelometric method (Array 360 System; Beckman-Coulter) or by immune turbidimetry (Beckman Coulter AU5400). The phenotype was determined by isoelectric focusing analysis (IEF) on agarose gel with specific immunological detection [21]. DNA was isolated from whole peripheral blood or dried blood spot (DBS) samples using a commercial extraction kit (DNA IQ System, Promega or PAXgene Blood DNA kit, PreAnalytix or DNA Blood Mini kit, Qiagen). The new mutations were identified by sequencing all coding exons (II-V) of the AAT gene (SERPINA1, RefSeq: NG_008290), as previously described [20,22], using the CEQ 8800 genetic analysis System (Beckman Coulter) or the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit 3.1 (Applied Biosystem) with the 3130 Genetic Analyzer.

Results

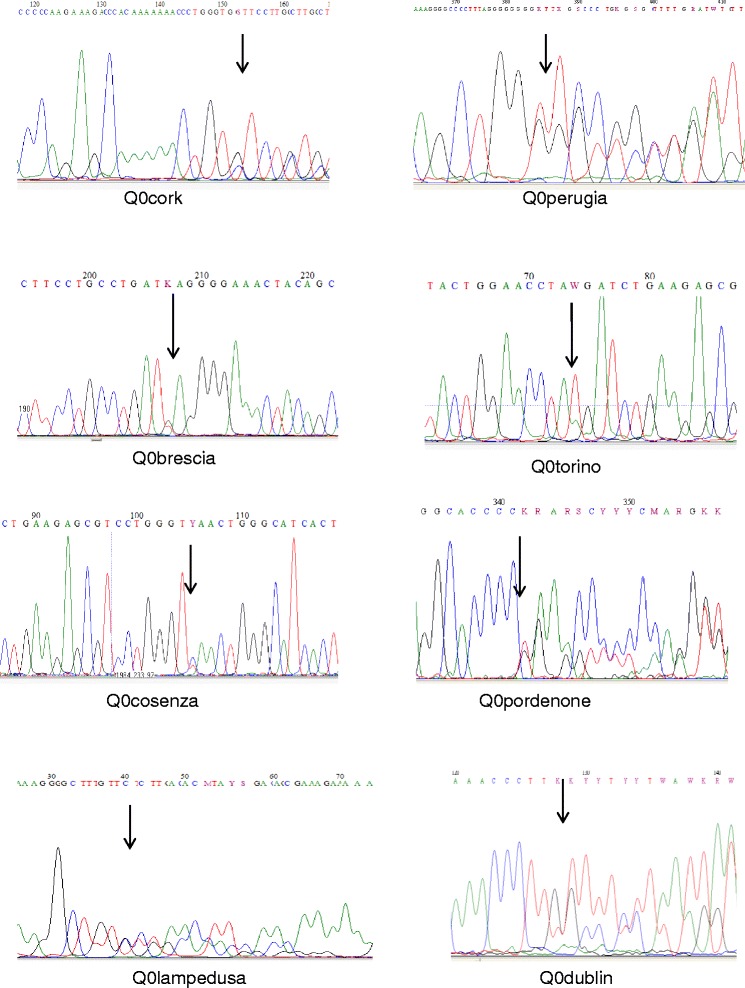

The specific mutations are summarized in Table 1. The eight new Null mutations have been conventionally named Q0cork, Q0perugia, Q0brescia, Q0torino, Q0cosenza, Q0pordenone, Q0lampedusa, and Q0dublin according to the birthplaces of the oldest subject carrying each mutation. Q0brescia, Q0torino and Q0cosenza consist of point mutations in the sequence of coding DNA that result in a premature stop codon (nonsense mutation). Q0cork, Q0perugia, Q0pordenone, Q0lampedusa and Q0dublin were caused by deletions, resulting in frameshift of the reading frame, and creating premature stop codons (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Description of the eight new SERPINA1 Null mutations identified

| Variant | Mutation |

|---|---|

| Q0cork | T180ACA,delCA > Ter190TAA |

| Q0perugia | V239GTG, delG > Ter241TGA |

| Q0brescia | E257GAG > TerTAG |

| Q0torino | Y297TAT > TerTAA |

| Q0cosenza | Q305CAA > TerTAA |

| Q0pordenone | L327CTG,delT > Ter338TGA |

| Q0lampedusa | V337GTG,delG > Ter338TGA |

| Q0dublin | F370TTT,delT > Ter373TAA |

Figure 1.

Genomic sequence chromatograms representing SERPINA1 Null mutations.

The genotype, AAT levels, and clinical details of each proband and their relatives bearing Null mutations are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of clinical details of Q0 individuals

| Case | Genotype | AAT (g/L) | Age at diagnosis (years) | Proband/kinship to proband | Clinical | Pack/year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 – IA | M1/Q0cork | 0.70 | 43 | proband | cough, dyspnoea | 15 |

| 2.1 - IA | M3/Q0perugia | 0.83 | 60 | proband | emphysema | 52 |

| 2.1 - IB | M3/Q0perugia | 0.80 | 54 | brother | healthy | 22 |

| 3.1 – IA | M1/Q0brescia | 0.70 | 73 | mother | chronic bronchitis | 0 |

| 3.1 – IB | M1/Q0brescia | 0.71 | 71 | father | healthy | 0 |

| 3.1 – IIA | Q0brescia/Q0brescia | Undetectable | 41 | proband | emphysema | 3 |

| 3.1 – IIB | Q0brescia/Q0brescia | Undetectable | 37 | proband | emphysema | 6 |

| 3.1 – IIIA | M1/Q0brescia | 0.70 | 7 | daughter | healthy | 0 |

| 3.1 – IIIB | M1/Q0brescia | 1.08 | 10 | daughter | healthy | 0 |

| 3.2 - IA | Z/Q0brescia | 0.20 | 41 | proband | emphysema | 20 |

| 4.1 - IA | S/Q0torino | 0.71 | 53 | proband | emphysema | 15 |

| 5.1 – IA | M2/Q0cosenza | 0.80 | 63 | aunt | dyspnoea | 0 |

| 5.1 – IB | M2/Q0cosenza | 0.85 | 67 | mother | asthma | 0 |

| 5.1 – IIA | S/Q0cosenza | 0.60 | 34 | proband | healthy | 4 |

| 5.1 – IIB | S/Q0cosenza | 0.71 | 43 | sister | healthy | 0 |

| 6.1 – IA | M2/Q0pordenone | 0.55 | 37 | father | healthy | 0 |

| 6.1 – IIA | M3/Q0pordenone | 0.81 | 6 | brother | healthy | 0 |

| 6.1 – IIB | M1/Q0pordenone | 0.77 | 0.5 | proband | cough | 0 |

| 6.2 – IA | M1/Q0pordenone | 0.91 | 54 | proband | emphysema | ex |

| 6.2 – IIA | M1/Q0pordenone | 0.78 | 34 | nephew | healthy | 0 |

| 6.2 – IIB | M1/Q0pordenone | 0.66 | 24 | nephew | healthy | 0 |

| 6.3 – IA | M1/Q0pordenone | 0.47 | 69 | proband | emphysema | unknown |

| 6.3 – IIA | M1/Q0pordenone | 0.81 | 37 | son | healthy | 0.1 |

| 6.4 – IA | M3/Q0pordenone | 1.30 | 38 | mother | healthy (pregnant) | 0 |

| 6.4 – IIA | M2/Q0pordenone | 0.78 | 6 | proband | healthy | 0 |

| 7.1 – IA | M1/Q0lampedusa | 0.62 | 87 | mother | emphysema | 0 |

| 7.1 – IIA | M1/Q0lampedusa | 0.76 | 57 | sister | healthy | 0 |

| 7.1 – IIB | M1/Q0lampedusa | 0.80 | 61 | sister | healthy | 0 |

| 7.1 – IIC | M1/Q0lampedusa | 0.73 | 55 | sister | healthy | 15 |

| 7.1 – IID | M1/Q0lampedusa | 0.74 | 51 | sister | chronic bronchitis | 60 |

| 7.1 – IIE | M1/Q0lampedusa | 0.71 | 48 | sister | chronic bronchitis | 0 |

| 7.1 – IIF | Q0lampedusa/Q0lampedusa | <0.1 | 46 | proband | emphysema, asthma | 0 |

| 7.1 – IIIA | M1/Q0lampedusa | 1.00 | 30 | niece | healthy | 0 |

| 7.1 – IIIB | M2/Q0lampedusa | 0.84 | 39 | nephew | healthy | 10 |

| 7.1 – IIIC | M1/Q0lampedusa | 0.64 | 33 | nephew | healthy | 24 |

| 7.1– IIID | M1/Q0lampedusa | 0.74 | 22 | nephew | healthy | 1.5 |

| 7.1 – IIIE | M1/Q0lampedusa | 0.67 | 15 | nephew | healthy | 0 |

| 8.1 – IA | M1/Q0dublin | 0.74 | 70 | proband | bronchiectasis | 1 |

| 8.1 – IIA | M1/Q0dublin | 0.64 | 40 | son | healthy | 0 |

| 8.1 – IIB | M1/Q0dublin | 0.70 | 34 | son | recurrent LRTIs | 1 |

| 8.1 – IIC | M1/Q0dublin | 1.11 | 39 | daughter | healthy | 0 |

Index cases are written in bold.

Q0cork

The proband was a 43 year old female who presented with cough, dyspnoea and wheeze, and was subsequently diagnosed with asthma by methacholine challenge test (Family 1.1 – subject IA, Table 2). A current smoker, spirometry showed no evidence of airways obstruction with pre-bronchodilator FEV1 of 2.55 L (95%), FVC 3.12 L (100%), and FEV1/FVC 82%. High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the lungs showed no evidence of emphysema or bronchiectasis. However, during routine assessment, the AAT concentration was found to be unusually low given the apparent MM phenotype observed on IEF, therefore DNA sequencing was performed. A deletion of CA in codon 180 ACA (exon II), present in heterozygosity, was detected. The deletion causes a frameshift in the reading frame and generates a premature stop codon (TAA) downstream at codon 190. The subject was homozygous Val213, therefore the novel Q0cork deletion arose on a M1(Val213) background.

Q0perugia

The proband (Family 2.1 – subject IA, Table 2) was a 60 year old male heavy smoker who developed emphysema before the age of 50. Since his AAT concentration in plasma was lower than normal, a complete genetic analysis of AAT was performed. The sequencing of SERPINA1 gene revealed the heterozygous deletion of the first G in the codon 239 GTG (exon III), which causes a frameshift in the reading frame and the generation of a premature stop codon (241TGA). The novel mutation was also detected in a brother. Phenotype analysis and family pedigree revealed that this Null mutation arose on M1(Val213) background.

Q0brescia

The probands were two sisters (Family 3.1, Table 2), both suffering from pulmonary emphysema and COPD. Their spirometry values showed obstructive defects with pre-bronchodilator FEV1 of 1.89 and 1.23 L (62% and 38%), FVC 3.38 and 2.11 L (97% and 63%), and FEV1/FVC 64% and 60%, respectively. Direct sequencing revealed both are homozygous for a point mutation at codon 257 (G > T transversion), changing a GAG (glutamic acid) codon into a TAG stop codon. Furthermore, both were homozygous for Alanine polymorphism at position 213 (rs6647), corresponding to the ancestral AAT gene variant M1(Ala). The familial study was performed on their two daughters (one from each sister) and their parents and confirmed the mendelian inheritance, showing heterozygosity both for the mutation at position 257 and for the M1 polymorphism at position 213 for all subjects. According to the reports of the probands their parents had no distant relationship, although they were born in two nearby villages in south-east Italy. Subsequently, this novel mutation was detected in a patient with severe AATD who was found to be composite heterozygous Z/Q0brescia (3.2-IA, Table 2). The proband, born in the same south-eastern Italian area, was a heavy smoker, who suffered from dyspnoea on exertion and productive cough, and he developed panlobular emphysema by the age of 40. His spirometry values showed obstructive defects with pre-bronchodilator FEV1 of 1.01 L (27%), FVC 3.36 L (73%), and FEV1/FVC 36%.

Q0torino

In index case 4.1 – IA (Table 2) DNA sequencing revealed heterozygosity for the S mutation (rs17580) and for a T > A transversion at codon 297 (TyrTAT > TerTAA) in exon IV. Analysis of the daughter confirmed that the Null mutation does not segregate with the S mutation and it arose on a M1(Val) background. The proband was a ex-smoker (15 pack/year) with emphysema and dyspnoea at rest.

Q0cosenza

The proband was a 34 year old healthy male with a reported low concentration of AAT in plasma during a routine medical assessment (Family 5.1 – subject IIA, Table 2). DNA sequencing of the proband revealed heterozygosity for the S mutation (rs17580) and for a C > T transition at codon 305 (CAA > TAA) in exon IV. This transversion results in a premature Stop codon instead of a glutamine codon. Family screening revealed that the Null mutation does not segregate with S mutation and that the novel Q0cosenza allele arose on an M2 background. The novel mutation was also detected in a sister (who carried the S mutation as well), the mother and an aunt.

Q0pordenone

In index case 6.1 – IIB (Table 2), a deletion of a single T in codon 327 (exon IV) was discovered by DNA sequencing. The deletion was heterozygous and no other mutation was present. It causes a frameshift in the reading frame and generates a premature stop codon (TGA) 11 codons downstream. The mutation was also detected in the father and a brother of the index case. Like in the index case 6.1-IIB, Q0pordenone was identified in heterozygosity with M alleles coding for normal AAT levels in 3 additional cases (6.2 - IA, 6.3 - IA and 6.4 - IIA), and in 4 relatives (2 nephews of 6.2 - IA, one son of 6.3 - IA and the mother of 6.4 - IIA). The four families carrying this novel Null allele were not related, but all subjects carrying Q0pordenone identified so far were born in the North-East region of Italy.

Q0lampedusa

DNA sequencing of the 4 exons of SERPINA1 in the index case (7.1 – IIF, Table 2) revealed a homozygous deletion of a single G in codon 337 (exon V), occurring in the background of a normal M2 allele (His101-Val213-Asp376). This deletion results in a frameshift that produces an altered reading frame and generates an immediately adjacent premature stop codon (TGA) at position 338. The proband was a woman, never smoker, who worked in a sawmill; she had the first episodes of dyspnoea on exertion at the age of 35, but suspicion of AATD did not arise untill ten years later, when HRCT diagnosed centrolobular emphysema and spirometry detected slight obstruction with pre-bronchodilator FEV1 of 1.5 (63%), FVC 2.39 L (85% ), and post-bronchodilator FEV1 of 1.63 (72%), FVC 2.65 L (96%). The consanguinity of the proband’s parents was excluded, according to the direct report of the patients; nevertheless, they was born in two small islands near to Sicily, therefore a founder effect is probable. The novel mutation Q0lampedusa was subsequently diagnosed in heterozygous fashion with M alleles coding for normal AAT levels in 11 out of 23 relatives who were subsequently investigated. Direct sequencing of SERPINA1 exons in the remaining family members has confirmed the segregation of the mutant allele.

Q0dublin

The proband was a 70 year old female who presented with bronchiectasis and a lower than expected AAT concentration given the apparent MM phenotype observed on IEF analysis (Family 8.1 – subject IC, Table 2). A past smoker, spirometry showed no evidence of airways obstruction with pre-bronchodilator FEV1 of 1.44 L (89%), FVC 1.97 L (98%), and FEV1/FVC 73%. HRCT of the lungs showed bronchiectasis but no evidence of emphysema. Sequencing identified a deletion of a single T resulting in a frameshift which alters the reading frame and generates an adjacent premature stop codon (TAA) at position 373. The subject was homozygous Val213, therefore the novel Q0dublin deletion arose on a M1(Val213) background. The same mutation was detected in heterozygosity in all three children.

Discussion

Null alleles result from different molecular mechanisms, including large gene deletions, intron mutations, nonsense mutations, frameshift mutations due to small insertions or deletions, and missense mutations associated with amino acid substitutions in potentially critical structural elements [23]. The common trait of Null mutations is the total absence of serum AAT. These mutations are extremely rare and can be difficult to diagnose, mainly because isoelectric focusing (IEF), a commonly used diagnostic method, although not preferred technique for screening of AATD [24], is not able to detect Null variants, as they do not produce protein. Therefore, the M/Null and MM phenotypes are identical when analysed by isoelectric focusing with only the normal M protein evident. Secondly, M/Null genotypes can be misclassified as M homozygotes in many common genotyping assays [25]. Sequence analysis of SERPINA1 gene is the optimal technique to detect Null mutations and only the application of an efficient and cost-effective diagnostic algorithm can ensure the diagnosis of a subject heterozygous or homozygous for Null mutations [20].

The existence of AAT Null alleles was first noted in the early 1970s by several investigators. The first published report of a Null SERPINA1 mutation described the case of a 24 year old man who had advanced pulmonary emphysema and no detectable serum AAT [26]. The first report of a probable Null SERPINA1 mutation in Ireland was a case report in 1974 describing a pedigree in which the proband was Z/Null, a son S/Null and the mother M/Null [27]. The precise Null mutation was not identified and the diagnosis was based on the discordant AAT concentrations in his son and mother when compared to phenotype identified by starch gel electrophoresis. The first report of a Null mutation of Italian origin was Q0trastevere, which was detected in an Italian individual with asthma and emphysema [16].

To date, a total of 26 different Null alleles have been detected and characterized (Table 3). Many are caused by premature stop codons, mainly due to nonsense mutations or insertion/deletion of one-two nucleotides that cause frameshift of the reading frame and lead to a premature stop codon. A second group of Null mutations lie in introns; some of these have been identified in mRNA splicing sites: Nullwest is characterized by a single G > T base substitution at position 1 of intron II, which generally is highly conserved; Nullbonny blue has been described as a deletion of the previously reported G. Other mutations are caused by large deletions; examples are Nullisola di procida, a deletion of a 17Kb fragment that includes exons II-V [14], and Nullriedenburg, caused by the complete deletion of the gene [28]. It is well known that an almost full length molecule is essential for the secretion of AAT, therefore a truncated protein prevents the secretion itself [18].

Table 3.

List of the 24 Null mutation SERPINA1 described to date

| Mechanism | Allele | Intron/exon | Mutation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large deletion | Q0isola di procida | Intron IC | g8801,del17.65 kb | [14] |

| Q0riedenburg | Exon IC | Complete deletion of the gene | [28] | |

| Intron mutations | Q0savannah | Intron IA | g.5307_5308ins8bp | [29] |

| Q0porto | Intron IC | +1G > A | [30] | |

| Q0madrid | Intron IC | +3, insT | [31] | |

| Q0west | Intron II | +1G > T | [15] | |

| Q0bonny blue | Intron II | +1delG | [23] | |

| Nonsense mutations | Q0kowloon | Exon II | Y 38TAC > Ter TAA | [23] |

| Q0chillichote | Exon II | Q 156CAG > Ter TAG | [29] | |

| Q0amersfoort or Q0predevoort rs199422210 | Exon II | Y 160TAC > Ter TAG | [19,32] | |

| Q0trastevere | Exon III | W194 TGG > Ter TGA | [16] | |

| Q0bellingham rs199422211 | Exon III | K 217AAG > Ter TAG | [33] | |

| Q0cairo rs1802963 | Exon III | K 259AAA > Ter TAA | [34] | |

| Frameshift mutations | Q0milano | Exon III | K59,del17bp > Ter AAA | [35] |

| Q0soest | Exon II | T102ACC,del A > Ter 112 TGA | [32] | |

| Q0granite falls rs267606950 | Exon II | YTAC, delC > Ter 160 TAG | [36] | |

| Q0hong kong | Exon IV | L318CTC, del TC > Ter 334 TAA | [17] | |

| Q0mattawa rs28929473 | Exon V | L353 TTA, ins T > Ter 376 TGA | [37] | |

| Q0ourem | Exon V | L 352TTA, ins T > Ter 376 TGA | [38] | |

| Q0bolton | Exon V | P362CCC, delC > Ter 373 TAA | [39] | |

| Q0clayton | Exon V | P 362CCC,ins C > Ter 376 TGA, and M1(Val) | [40] | |

| Q0saarbruecken | Exon V | P362CCC,ins C > Ter 376 TGA, and M1(Ala) | [41] | |

| Missense mutations | Q0lisbon | Exon II | T68ACC > I ATC | [41] |

| Q0ludwigshafen rs28931572 | Exon II | I92ATC > N AAC | [42] | |

| Q0newport | Exon II | G115GGC > S AGC | [43] | |

| Q0new hope | Exon IV | G320GGG > E GAG and E342GAG > L AAG | [23] |

For intronic mutations, reference sequence was NG_008290; dbSNP identification was reported where present.

Interestingly, Null mutations can also be induced by a simple amino acid substitution, like in Nullludwigshafen (Ile92 > Asn92). This substitution of a polar for a non-polar amino acid leads to folding impairment, with destruction of tertiary structure and therefore intracellular degradation [42]. In most Null mutations belonging to this group, it is not clear whether the altered glycoprotein is unstable and therefore recognized as defective by intracellular methabolic pathways and degraded, or if it is secreted but, due to a very short half-life with rapid turnover, it cannot be detected by routine diagnostic assays. In addition, some Null mutations may yet turn out to be “secreted” Null. For example, Nullnew hope and Nullnewport, were defined as Null on the basis of IEF and protein quantification in a period when molecular diagnosis was not widely available. A precedent for incorrect Null alleles does exist, and includes the well known Mheerlen, which was originally classified as PiQ0 on the basis of IEF and protein quantification [44], and Plowell, previously called Q0cardiff [45].

We describe here eight novel Null mutations in the coding regions of the SERPINA1 gene. Three (Q0brescia, Q0torino and Q0cosenza) are nonsense mutations, the others (Q0cork, Q0perugia, Q0pordenone, Q0lampedusa and Q0dublin) are frameshift mutations caused by deletion of one or two nucleotides.

It is worth noting most of the new mutations reported in this study occur close to other mutations, supporting the concept of mutational hot spots in the SERPINA1 gene [40]. In fact, Q0brescia occurs in a portion of 27 nucleotides (nine amino acids) in exon III of the gene, where it is possible to find a conspicuous number of other mutations: Plowell /Pduarte/Ybarcelona at codon 256, Q0cairo and Mpisa [46] at codon 259, T/S at codon 264, and the normal variant Lfrankfurt at codon 255. Q0pordenone lies in another region of 27 nucleotides together with other Null (Q0hongkong, Q0new hope) and normal (Plyon, Psaltlake,) mutations. Q0lampedusa occurs in the region of 21 nucleotides where, in addition to Z, other deficient (King, Wbethesda) and normal (Etokyo, Pst.albans) mutations lie. Lastly, Q0dublin is only one nucleotide from Mheerlen and Mwurzburg mutations and two nucleotides from Etaurisano [46] deficient alleles.

While Null mutations are extremely rare, the recurrence of Q0pordenone and Q0brescia in certain localized areas, without evidence of consanguinity, may indicate a relatively high prevalence of each Null allele in these geographic regions.

Although a discussion of the clinical characteristics of the Null-bearing subjects presented herein is not the main purpose of this study, we can draw some interesting conclusions. Subjects with Null mutations should be considered a subgroup at particularly high risk of emphysema within the spectrum of AATD [19]. In support of this, we report three probands homozygous for Null alleles, with early onset lung disease, despite absent or modest smoking history. Interestingly, the clinical importance of Null heterozygosity has never been investigated. Here we report evidence of the recurrence of lung symptoms (dyspnoea, cough) and lung diseases (emphysema, asthma, chronic bronchitis) in M/Null subjects, over 45 years of age, irrespective of their smoking habit (Table 2).

Conclusions

Our study has significantly expanded the list of Null alleles known to occur within the SERPINA1 gene and underlined the importance of the correct diagnosis of this group of mutations, because of the particularly high risk of lung disease.

Acknowledgments

The work was support by the Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo Ricerca Corrente (RC345). We wish to thank the Alpha One Foundation (Ireland), the Irish Government Department of Health and Children, Pat O’Brien, Eric Mahon, Emma Pentony, and Professor William Torney of the Department of Chemical Pathology at Beaumont Hospital, and Mario De Marchi of S. Luigi Hospital, Orbassano. We acknowledge the support of the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the National Society (AIMAR), joint ERS/AIMAR Fellowship STRTF 87–2010. We also thank Mrs. Nuccia Gatta, president of the Italian Alpha-1 association, for continuous support. A special thanks to all the patients and their families who participated in this study.

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of dear friend and colleague professor Maurizio Luisetti.

Abbreviations

- AAT

Alpha1-antitrypsin

- SERPIN

Serine protease inhibitor

- AATD

Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- IEF

Isoelectric focusing

- HRCT

High resolution computed tomography

Additional file

Family trees of probands analysed in the present study.

Footnotes

Ilaria Ferrarotti and Tomás P Carroll contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

Authors have no potential conflicts of interest with any companies/organisations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Authors’ contributions

IF and TPC conceived of the study and wrote the manuscript. IF, TPC, SO, GO’B, DM performed experiments. AMF, NGM, ML helped with discussion and interpretation of the results. KM, LC, DRC collected samples and clinical data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ilaria Ferrarotti, Email: i.ferrarotti@smatteo.pv.it.

Tomás P Carroll, Email: tcarroll@rcsi.ie.

Stefania Ottaviani, Email: stefania.ottaviani@yahoo.it.

Anna M Fra, Email: fra@med.unibs.it.

Geraldine O’Brien, Email: geraldineobrienster@gmail.com.

Kevin Molloy, Email: kmolloy@rcsi.ie.

Luciano Corda, Email: luciano.corda@spedalicivili.brescia.it.

Daniela Medicina, Email: daniela.medicina@spedalicivili.brescia.it.

David R Curran, Email: dcurran@muh.ie.

Noel G McElvaney, Email: gmcelvaney@rcsi.ie.

Maurizio Luisetti, Email: m.luisetti@smatteo.pv.it.

References

- 1.Carrell RW, Jeppsson JO, Laurell CB, Brennan SO, Owen MC, Vaughan L, Boswell DR. Structure and variation of human alpha 1-antitrypsin. Nature. 1982;298:329–334. doi: 10.1038/298329a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly E, Greene CM, Carroll TP, McElvany NG, O’Neill SJ. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Respir Med. 2010;104:763–772. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers J, Kalsheker N, Wallis S, Speer A, Coutelle CH, Woods D, Humphries SE. The isolation of a clone for human alpha 1-antitrypsin and the detection of alpha 1-antitrypsin in mRNA from liver and leukocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;116:375–382. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(83)90532-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrarotti I, Thun GA, Zorzetto M, Ottaviani S, Imboden M, Schindler C, von Eckardstein A, Rohrer L, Rochat T, Russi EW, Probst-Hensh NM, Luisetti M. Serum levels and genotype distribution of alpha1-antitrypsin in the general population. Thorax. 2012;67:669–674. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergin DA, Hurley K, McElvaney NG, Reeves EP. Alpha-1 antitrypsin: a potent anti-inflammatory and potential novel therapeutic agent. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2012;60:81–97. doi: 10.1007/s00005-012-0162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edmonds BK, Hodge JA, Rietschel RL. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency-associated panniculitis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:296–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis M, Kallenbach J, Zaltzman M, Levy H, Lurie D, Baynes R, King P, Meyers A. Severe deficiency of alpha 1-antitrypsin associated with cutaneous vasculitis, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, and colitis. Am J Med. 1985;79:489–494. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett VT, Sekosan M, Khurshid A. Wegener’s granulomatosis and alpha1-antitrypsin-deficiency emphysema: proteinase-related diseases. Chest. 1999;116:253–255. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.1.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyons PA, Rayner TF, Trivedi S, Holle JU, Watts RA, Jayne DR, Baslund B, Brenchley P, Bruchfeld A, Chaudhry AN, Cohen Tervaert JW, Deloukas P, Feighery C, Gross WL, Guillevin L, Gunnarsson I, Harper L, Hrušková Z, Little MA, Martorana D, Neumann T, Ohlsson S, Padmanabhan S, Pusey CD, Salama AD, Sanders JS, Savage CO, Segelmark M, Stegeman CA, Tesař V, et al. Genetically distinct subsets within ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(3):214–223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lomas DA, Evans DL, Finch JT, Carrell RW. The mechanism of Z alpha 1-antitrypsin accumulation in the liver. Nature. 1992;357:605–607. doi: 10.1038/357605a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curiel DT, Chytil A, Courtney M, Crystal RG. Serum alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency associated with the common S-type (Glu264––Val) mutation results from intracellular degradation of alpha 1-antitrypsin prior to secretion. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(18):10477–10486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahl M, Hersh CP, Ly NP, Berkey CS, Silverman EK, Nordestgaard BG. The protease inhibitor PI*S allele and COPD: a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(1):67–76. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00135704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahadeva R, Chang WS, Dafforn TR, Oakley DJ, Foreman RC, Calvin J, Wight DG, Lomas DA. Heteropolymerization of S, I, and Z alpha1-antitrypsin and liver cirrhosis. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(7):999–1006. doi: 10.1172/JCI4874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi H, Crystal RG. Alpha 1-antitrypsin Null(isola di procida): an alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency allele caused by deletion of all alpha 1-antitrypsin coding exons. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;47:403–413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laubach VE, Ryan WJ, Brantly M. Characterization of a human alpha 1-antitrypsin null allele involving aberrant mRNA splicing. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:1001–1005. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.7.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Novoradovskaya N, Rundquist B, Redwine J, Saltini C, Brantly M. Alpha 1-antitrypsin nonsense mutation associated with a retained truncated protein and reduced mRNA. Mol Genet Metab. 1998;63:270–280. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1998.2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sifers RN, Brashears-Macatee S, Kidd VJ, Muensch H, Woo SL. A frameshift mutation results in a truncated alpha 1-antitrypsin that is retained within the rough endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7330–7335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brodbeck RM, Brown JL. Secretion of a-1-proteinase inhibitor requires an almost full length molecule. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:294–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fregonese L, Stolk J, Frants RR, Veldhuisen B. Alpha-1 antitrypsin Null mutations and severity of emphysema. Respir Med. 2008;102:876–884. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrarotti I, Scabini R, Campo I, Ottaviani S, Zorzetto M, Gorrini M, Luisetti M. Laboratory diagnosis of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Transl Res. 2007;150:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zerimech F, Hennache G, Bellon F, Barouh G, Jacques Lafitte J, Porchet N, Balduyck M. Evaluation of a new Sebia isoelectrofocusing kit for alpha 1-antitrypsin phenotyping with the Hydrasys System. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46:260–263. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medicina D, Montani N, Fra AM, Tiberio L, Corda L, Miranda E, Pezzini A, Bonetti F, Ingrassia R, Scabini R, Facchetti F, Schiaffonati L. Molecular characterization of the new defective P(brescia) alpha1-antitrypsin allele. Hum Mut. 2009;30:E771–E781. doi: 10.1002/humu.21043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HJ, Brantly M. Molecular mechanism of alpha1-antitrypsin null alleles. Respir Med. 2000;94:S7–S11. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miravitlles M, Herr C, Ferrarotti I, Jardi R, Rodriguez-Frias F, Luisetti M, Bals R. Laboratory testing of individuals with severe alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in three European centres. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:960–968. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00069709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez-Frias F, Vila-Auli B, Homs-Riba M, Vidal-Pla R, Calpe-Calpe JL, Jardi-Margalef R. Diagnosis of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: limitations of rapid diagnostic laboratory tests. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:415–417. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talamo RC, Langley CE, Reed CE, Makino S. Antitrypsin deficiency: a variant with no detectable α1 -antitrypsin. Science. 1973;181:70–71. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4094.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blundell G, Cole RB, Nevin NC, Bradley B. Alpha 1-antitrypsin null gene (pi) Lancet. 1974;2:404. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poller W, Faber JP, Weidenger S, Olek K. DNA polymorphism associated with a new α1-antitrypsin PIQ0 variant (PI Q0riedenburg) Hum Genet. 1991;86:522–524. doi: 10.1007/BF00194647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brantly M, Schreck P, Rouhani FN, Bridges LR, Leong A, Viranovskaya N, Charleston C, Min B, Strange C. Rare and novel alpha-1-antitrypsin alleles identified through the University of Florida-Alpha-1 Foundation DNA bank [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:A3506. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seixas S, Mendonça C, Costa F, Rocha J. alpha1-Antitrypsin null alleles: evidence for the recurrence of the L353fsX376 mutation and a novel G–>A transition in position +1 of intron IC affecting normal mRNA splicing. Clin Genet. 2002;62:175–180. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.620212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lara B, Martinez MT, Balnco I, Hernàndez-Moro C, Velasco EA, Ferrarotti I, Rodriguez-Frias F, Perez L, Vazquez I, Alonso J, Posada M, Martinez-Delgado B. Severe alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in composite heterozigotes inheriting a new splicing mutation Q0madrid. Resp Res. 2014;15:125. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0125-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prins J, van der Meijden BB, Kraaijenhagen RJ, Wielders JP. Inherited chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: new selective-sequencing workup for alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency identifies 2 previously unidentified null alleles. Clin Chem. 2008;54:101–107. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.095125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satoh K, Nukiwa T, Brantly M, Garver RI, Jr, Hofker M, Courtney M, Crystal RG. Emphysema associated with complete absence of alpha 1- antitrypsin in serum and the homozygous inheritance of a stop codon in an alpha 1-antitrypsin-coding exon. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;42:77–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zorzetto M, Ferrarotti I, Campo I, Balestrino A, Nava S, Gorrini M, Scabini R, Mazzola P, Luisetti M. Identification of a novel alpha1-antitrypsin null variant (Q0Cairo) Diagn Mol Pathol. 2005;14:121–124. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000155023.74859.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rametta R, Nebbia G, Dongiovanni P, Farallo M, Fargion S, Valenti L. A novel alpha1-antitrypsin gene variant (PiQ0Milano) World J Hepatol. 2013;5:458–461. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i8.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nukiwa T, Takahashi H, Brantly M, Courtney M, Crystal RG. alpha 1-Antitrypsin nullGranite Falls, a nonexpressing alpha 1-antitrypsin gene associated with a frameshift to stop mutation in a coding exon. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:11999–12004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curiel D, Brantly M, Curiel E, Stier L, Crystal RG. α1-antitrypsin deficiency caused by the α1-antitrypsin Nullmattawa gene. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1144–1152. doi: 10.1172/JCI113994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Rodrigues L, Costa F, Marques P, Mendonça C, Rocha J, Seixas S. Severe α-1 antitrypsin deficiency caused by Q0(Ourém) allele: clinical features, haplotype characterization and history. Clin Genet. 2011;81:462–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fraizer GC, Siewertsen MA, Harrold TR, Cox DW. Deletion/frameshift mutation in the α1-antitrypsin null allele, PI*Q0bolton. Hum Genet. 1989;83:377–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00291385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brantly M, Lee JH, Hildeshine J, Uhm C, Prakash UBS, Staats BA, Crystal RG. Alpha1-antitrypsin gene mutation hot spot associated with the formation of a retained and degraded null variant. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:225–231. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.3.9070606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faber JP, Poller W, Weidinger S, Kirchfesser M, Schwaab R, Bidlingmaier F, Olek K. Identification and DNA sequence analysis of 15 new alpha1-antitryspin variants, including two PI*Q0 alleles and one deficient PI*M allele. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:1113–1121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frazier GC, Siewertsen MA, Hofker MH, Brubacher MG, Cox DW. A Null deficient allele of alpha1-antitrypsin, Q0ludwingshafen, with altered tertiary structure. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1878–1884. doi: 10.1172/JCI114919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graham A, Kalsheker NA, Bamforth FJ, Newton CR, Markham AF. Molecular characterization of two alpha 1-antitrypsindeficiency variants: proteinase inhibitor (Pi)Null Newport (Gly115 → Ser) and (Pi)Z Wrexham (Ser−19 → Leu) Hum Genet. 1990;85:537–540. doi: 10.1007/BF00194233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalsheker N, Hayes K, Weidinger S, Graham A. What is Pi (proteinase inhibitor)Null or PiQ0?: a problem highlighted by the alpha 1 antitrypsin Mheerlen mutation. J Med Genet. 1992;29:27–29. doi: 10.1136/jmg.29.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graham A, Kalsheker NA, Newton CR, Bamforth FJ, Powell SJ, Markham AF. Molecular characterization of three alpha 1-antitrypsindeficiency variants: proteinase inhibitor (Pi)Null Cardiff (Asp256 → Val), Pi M Malton (Phe51 → deletion) and Pi I (Arg39 → Cys) Hum Genet. 1989;84:55–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00210671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fra AM, Gooptu B, Ferrarotti I, Miranda E, Scabini R, Ronzoni R, Benini F, Corda L, Medicina D, Luisetti M, Schiaffonati L. Three new alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency variants help to define a C-terminal region regulating conformational stability and polymerization. PlosOne. 2012;7:e38405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]