Abstract

Background

To evaluate the role of plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) and homozygosity for the thermolabile variant of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T genotype in the risk of retinal vein occlusion (RVO).

Methods

Relevant studies were selected through an extensive search of PubMed, EMBASE, and the Web of Science databases. Summary weighted mean differences (WMDs) or odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated with a random-effects model.

Results

Forty-two studies with 6445 participants were included in this updated systematic review and meta-analysis. The mean plasma tHcy level in the RVO patients was significantly higher than in the controls (WMD =2.13 μmol/L; 95% CI: 1.29 to 2.98, P < 0.001), but there was evidence of between-study heterogeneity (P < 0.001). No significant association between MTHFR C677T genotype and RVO was found under all genetic models.

Conclusion

There was some evidence that plasma tHcy is associated with an increased risk of RVO. There was no evidence to suggest an association between homozygosity for the MTHFR C677T genotype and RVO.

Keywords: Homocysteine, Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, Retinal vein occlusion

Background

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is one of the most common vision-threatening retinal vascular diseases, affecting males and females almost equally and occurring most frequently in elderly subjects [1, 2]. It is a multifactorial disease, which may affect small, medium, and large ocular vessels, with central occlusion representing the most dangerous clinical entity. Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) and branch retinal vein occlusion are the most common and clinically relevant types of venous occlusions. Arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, atherosclerosis, and increased plasma lipoprotein (a) have been reported as systemic risk factors for RVO [3–7].

Homocysteine (Hcy), a sulfur-containing amino acid formed during the metabolism of methionine, can be remethylated to methionine throughmethyltetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) [8]. Several studies have shown that the level of plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) is elevated in RVO patients and it is a risk factor for RVO [9, 10]. The MTHFR C677T gene mutation is an important cause of elevated plasma tHcy. The mutation results in Hcy not being remethylated to methionine, leading to hyperhomocysteinemia [11, 12]. Although a number of studies have reported a correlation between the MTHFR C677T mutation and RVO, the role of the mutation in the pathogenesis of RVO remains unclear [13, 14].

A previous meta-analysis of 25 case–control studies conducted in 2009 showed that elevated tHcy was associated with RVO but not for the MTHFR C677T genotype [15]. However, this meta-analysis had some limitations, including a lack of information on the dose-effect relationship between tHcy and RVO. Another meta-analysis on the association of tHcy with RVO published in 2003 included only 19 case–control studies [16]. Since the meta-analysis was published, a variety of studies aimed at elucidating this relationship has yielded inconsistent results [10, 14, 17–20].

In the present study, we analyzed the relation among tHcy, the MTHFR C677T genotype, and RVO in an updated meta-analysis of case–control studies. The aim of this updated analysis of 42 studies was to derive a more precise estimation of the relationship among tHcy, the MTHFR C677T genotype, and the risk of RVO.

Methods

Literature search

A systematic literature search of PubMed, ISI Web of Science, and EMBASE was performed to identify relevant studies from inception until March 10, 2014. The following terms were used in the searches: “retinal vein occlusion” AND (“homocysteine” OR “methyltetrahydrofolate reductase”). The websites of professional associations and Google Scholar were also searched for additional information. When relevant articles were identified, their reference lists were searched for additional articles. The final search was carried out on March 10, 2014, without restrictions regarding publication year, language, or methodological filter.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies included in this meta-analysis met the following criteria. The studies (a) contained a laboratory assessment of plasma tHcy concentrations or reported odds ratio (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the association between tHcy and RVO, or they assessed the MTHFR C677T polymorphism. Alternatively, (b) articles were retrieved if they were retrospective, prospective, or case–control studies. If multiple publications from the same study population were available, the most recent study would be eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Editorials, letters to the editor, review articles, case reports, meeting abstracts, and animal experimental studies were excluded.

Data extraction

Two authors (Z.M.W. and X.Y.P.) independently extracted the following data from the included studies: publication data (author, year of publication, and country of the population studied); patient condition (fasting status); participant’s age and sex; number of cases and controls; the Hcy levels in the cases and the control subjects; the adjusted ORs of the association between tHcy and RVO; and the genotype counts.

Assessment of the quality of the methodology

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of each study using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [21]. The NOS uses a “star” rating system to judge quality based on three aspects of the study: selection, comparability, and exposure. The scores ranged from 0 stars (worst) to 9 stars (best). Studies with a score of ≥7 were considered of high quality [22, 23]. Any discrepancies were addressed by a joint re-evaluation of the original article with a third reviewer (D. L).

Statistical analysis

The weighted mean differences (WMDs) were used to compare the plasma tHcy concentrations between the case and control subjects. The pooled adjusted ORs with their corresponding 95% CIs were used as a common measure of the association between tHcy and the risk of RVO. ORs and 95% CIs were calculated for the MTHFR C677T TT genotype exposure and RVO. The association between MTHFR C677T genotype exposure and RVO was examined using the following genetic models: the homozygote co-dominant (TT vs. CC), heterozygote co-dominant (TC vs. CC), dominant genetic (TT/TC vs. CC), and recessive genetic (TT vs. TC/CC) models.

We combined the data using a random effects model to achieve more conservative estimates [24]. Statistical heterogeneity between the studies was evaluated using Cochran’s Q test and the I2 statistic. For the Q statistic, P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant heterogeneity. A meta-regression analysis was used to investigate the influence of the variables on the study heterogeneity across strata. To detect publication biases, we calculated Begg’s and Egger’s measures [25, 26]. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in the test for the overall effect. The analysis was conducted using the Stata software package (Version 12.0; Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Sensitivity analysis

A subgroup analysis was used to investigate which factors (diagnosis, sources of controls, adjusting factors, and overnight fasting status) might contribute to heterogeneity. Furthermore, we performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding the low-quality studies and reanalyzing the pooled estimate for the remaining studies.

Results

Literature search

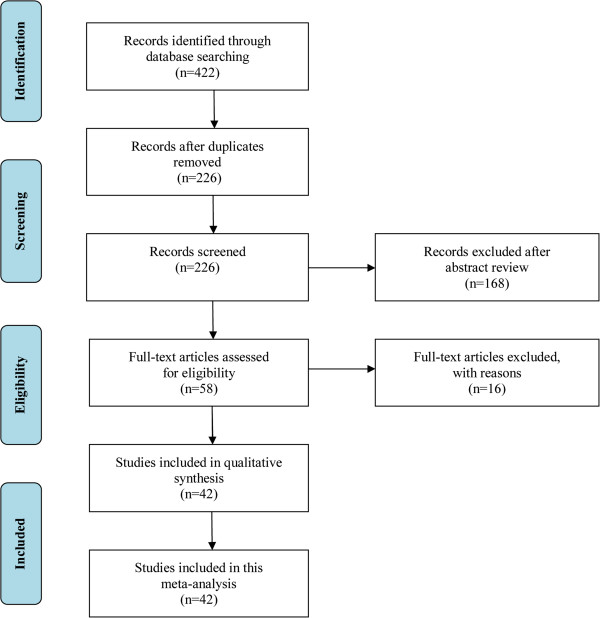

The literature search identified 422 papers. Of these, 196 were excluded because they were duplicate studies. Initially, the title, abstract, and medical subject heading words of the obtained publications were used for a rough judgment on the eligibility of an article. In total, 168 studies, including reviews and case series, were excluded for various reasons, such as being irrelevant to our analysis. The remaining 58 were retrieved for a full-text review. In total, 16 articles were excluded for various reasons. Of these, seven articles were excluded because they provided no data on plasma tHcy concentrations or the prevalence of the MTHFR C677T genotype. Four articles were excluded because they had insufficient data regarding plasma tHcy levels, only reporting on the proportion of hyperhomocysteinemia (hyperhomocysteinemia defined as plasma tHcy >15 μmol/L). Two articles were excluded because they were cross-section studies. Two articles contained duplicated data and one article compared the plasma tHcy concentrations between single-episode CRVO patients and recurrent CRVO patients. Finally, 42 case–control studies were included in this meta-analysis [9, 10, 14, 17–20, 27–61]. The study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram outlining the selection process for the inclusion of the studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

All studies were case–control in design. Table 1 shows the studies identified and their main characteristics. The studies were published between 1998 and 2014, and they originated from the United States, Israel, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Austria, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, France, Iran, Turkey, Thailand, China, India, and Brazil. In total, 2,794 cases and 3,651 controls were included in the meta-analysis. The controls were mainly healthy populations without retinal vascular disease. The NOS results showed that the average score was 7.11 (range 6–8), indicating that the methodological quality was generally good (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of enrolled case–control studies

| Author (year) | Country | Fasting | No. of RVO patients | No. of controls | Age (case/control, y) | Sex (case/control; M/F) | Source of cases | Source of controls | Matching | Reported Plasma tHcy concentrations or MTHFR C677T genotype | NOS score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | CRVO | BRVO | |||||||||||

| Salomon (1998) [59] | Israel | No | 102 | 45 | 48 | 105 | NA | 58/44; 65/40 | CP | Hospital patients with non-retinal vascular diagnosis | Age | MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Glueck (1999) [25] | United States | No | 17 | NA | NA | 234 | 52/37 | 8/9;NA | CP | “Healthy subjects” | NA | MTHFR C677T | 6 |

| Vine (2000 ) [26] | United States | No | 74 | 74 | 0 | 74 | 69.8/64.6 | 29/45; 33/41 | HR | Hospital patients with non-retinal vascular diagnosis | Age | tHcy | 8 |

| Larsson (2000) [27],a | Sweden | No | 37 | 37 | 0 | 65 | 40.9/40.9 | 67/49; 110/30 | HR | “Randomly selected” | Age | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 8 |

| 79 | 79 | 0 | 88 | 69.6/69.6 | |||||||||

| Pianka (2000) [28] | Israel | No | 21 | 21 | 0 | 81 | 58.6/66 | NA | CP | “Healthy adults” | Age, Sex | tHcy | 6 |

| Martin (2000) [9] | United Kingdom | Yes | 60 | 36 | 24 | 85 | 65.6/51.5 | NA | CP | Laboratory staff/hospital patients | NA | tHcy | 7 |

| Cahill (2000) [29] | Ireland | Yes | 61 | 40 | 21 | 87 | 69.2/70.2 | 29/32; 36/51 | HR | Hospital patients, primarily cataract extraction | Age | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 8 |

| Boyd (2001) [30] | United Kingdom | No | 63 | 63 | 0 | 63 | 60.3/60.8 | NA | CP | Hospital patients with non-retinal vascular diagnosis | Age | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 8 |

| Marcucci (2001) [31] | Italy | Yes | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | Median 59/ 56 | 54/46; 58/42 | CP | Friends/partners, no cardiovascular disease | Age, Sex | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Weger (2002) [32] | Austria | Yes | 84 | 0 | 84 | 84 | 68.1/68.2 | 37/47; 37/47 | CP | Hospital patients, | Age | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 8 |

| Adamczuk (2002) [33] | Argentina | Yes | 37 | 37 | 0 | 144 | NA | 17/20; 66/78 | CP | “Volunteers” | Age, Sex | MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Brown (2002) [34] | United States | Yes | 20b | 15 | 3 | 20 | 69.1/69.5 | 12/8; 10/10 | HR | “Normal subjects” | Age, Sex | tHcy | 8 |

| Weger (2002) [35] | Austria | Yes | 78 | 78 | 0 | 78 | 68.7/68.6 | 33/45; 33/45 | HR | Hospital patients | Age, Sex | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 8 |

| El-Asrar (2002) [36] | Saudi Arabia | Yes | 48 | 36 | 12 | 59 | 45.3/46.1 | NA;44/15 | CP | “Healthy adults” | Age, Sex | tHcy | 6 |

| Blondel (2002) [58] | France | No | 101 | 85 | 14 | 29 | 54/51.0 | 45/56; 13/16 | CP | Source not given | Age | tHcy | 7 |

| Marcucci (2003) [37] | Italy | Yes | 55 | 26 | 29 | 61 | Median 57/ 56 | 24/31; 27/34 | CP | Friends/partners, | Age, Sex | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 8 |

| Parodi (2003) [38] | Italy | Yes | 31 | 31 | 0 | 31 | 44.5/44.2 | 19/12; 19/12 | CP | “Volunteers” | Age, Sex | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Dodson (2003) [39] | United Kingdom | NA | 40 | NA | NA | 40 | Median 66.1/ 66 | 21/19; 21/19 | CP | “healthy adults” | Age, Sex | MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Yaghoubi (2004) [40] | Iran | Yes | 24 | 10 | 14 | 24 | 61.1/61. 7 | 11/13; 12/12 | CP | Hospital patients | Age | tHcy | 6 |

| Yildirim (2004) [41] | Turkey | Yes | 33 | 9 | 20 | 25 | 61.0/58.0 | 15/18; 11/14 | CP | NA | Age, Sex | tHcy | 7 |

| Atchaneeyas-akul (2005) [42] | Thailand | Yes | 32 | 11 | 15 | 88 | 53.8/54.4 | 19/22; 41/49 | CP | Volunteers | Age, Sex | tHcy | 6 |

| Ferrazzi (2005) [43] | Italy | Yes | 69 | NA | NA | 50 | 64.1/58.4 | 40/29; 38/12 | CP | Volunteers | Age | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 8 |

| McGimpsey (2005) [44] | United Kingdom | No | 106 | 60 | 46 | 98 | 67.9/68.4 | 55/51; 45/53 | HR | Clinic patients /friends | Age, Sex | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 8 |

| Gao(2006) [45] | China | Yes | 64 | 64 | 0 | 64 | 59.5/59.5 | 33/31; 33/31 | CP | Volunteers | Age, Sex, | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Gumus (2006) [46] | Turkey | Yes | 82 | 26 | 56 | 78 | 57.7/57.4 | 36/46; 33/45 | CP | Patients with refractive errors, presbyopia, or cataract | Age, Sex | tHcy | 7 |

| Lattanzio (2006) [47] | Italy | Yes | 58 | 58 | 0 | 103 | 39.8/40.3 | 38/20; 59/44 | CP | Hospital staff | Age, Sex | tHcy | 7 |

| Pinna (2006) [48] | Italy | Yes | 75 | 33 | 42 | 72 | 63.9/63.5 | 40/35; 37/35 | CP | Friends/partners/hospital staff | Age, Sex | tHcy | 8 |

| Narayanasam-y (2007) [49] | India | Yes | 29 | 29 | 0 | 57 | 31.0/27.0 | 22/7; 41/16 | CP | Hospital staff/students | Age, Sex | tHcy | 8 |

| Biancardi (2007) [50] | Brazil | No | 55 | NA | NA | 55 | NA | 23/32; 23/32 | CP | Hospital patients | Age, Sex | MTHFR C677T | 6 |

| Moghimi (2008) [51] | Iran | Yes | 54 | 54 | 0 | 51 | 59.8/63.0 | 32/22; 29/22 | CP | Clinic patients | Age, Sex, | tHcy | 7 |

| Sofi(2010) [52] | Italy | Yes | 262 | NA | NA | 262 | Median 66.0/ 65.5 | 122/140; 123/139 | CP | Healthy subjects | Age, Sex | tHcy | 8 |

| Di Capua (2010) [53] | Italy | Yes | 117 | NA | NA | 202 | 54.0/52.0 | 61/56; 105/97 | CP | Volunteers | Age, Sex | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Pinna(2010) [54] | Italy | Yes | 40 | 0 | 40 | 80 | 64.3/63.2 | 19/21; 38/42 | CP | “Normal subjects” | Age, Sex | tHcy | 8 |

| Sottilotta (2010) [14] | Italy | No | 105 | 17 | 88 | 226 | 58.4/55.7 | 46/59; 44/182 | CP | Healthy participants | Age | MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Pinna (2010) [55] | Italy | Yes | 29 | 29 | 0 | 80 | 63.2/63.2 | 15/14; 38/42 | CP | Healthy participants | Age, Sex | tHcy | 6 |

| Tea (2013) [19] | France | No | 21 | 21 | 0 | 23 | 46/46 | 14/7;15/8 | CP | Volunteers | Age, Sex | MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Bharathi (2012) [56] | India | Yes | 23 | 23 | 0 | 57 | 30.0/28.0 | 17/6; 38/16 | CP | Volunteers | Age, Sex | tHcy | 6 |

| Dong (2013) [18] | China | Yes | 68 | 68 | 0 | 68 | 58.6/58.6 | 28/40; 28/40 | CP | Hospital patients | Age, Sex | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Lahiri (2013) [10] | India | Yes | 64 | 24 | 40 | 45 | NA | NA | CP | NA | Age, Sex | tHcy | 7 |

| Minniti (2014) [17] | Italy | Yes | 91 | 47 | 44 | 71 | 57/55 | 51/40; 30/41 | HR | Volunteers | Age, Sex | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Mrad(2014) [20] | Tunisia | Yes | 72 | NA | NA | 140 | 48.5/51.7 | 50/22; 95/45 | HR | Healthy participants | Age | tHcy, MTHFR C677T | 7 |

| Russo (2014) [57] | Italy | Yes | 113 | NA | NA | 104 | NA | 57/56; 75/29 | CP | Volunteer controls | Age, Sex | MTHFR C677T | 6 |

aData presented in 2 age groups: <50 years and >50 years.

bIncludes others (e.g., hemi-retinal, hemispheric, macular).

RVO = retinal vein occlusion; CRVO = central retinal vein occlusion; BRVO = branch retinal vein occlusion; M = male; F = female; CP = consecutive patients; HR = Hospital records; NA = not available.

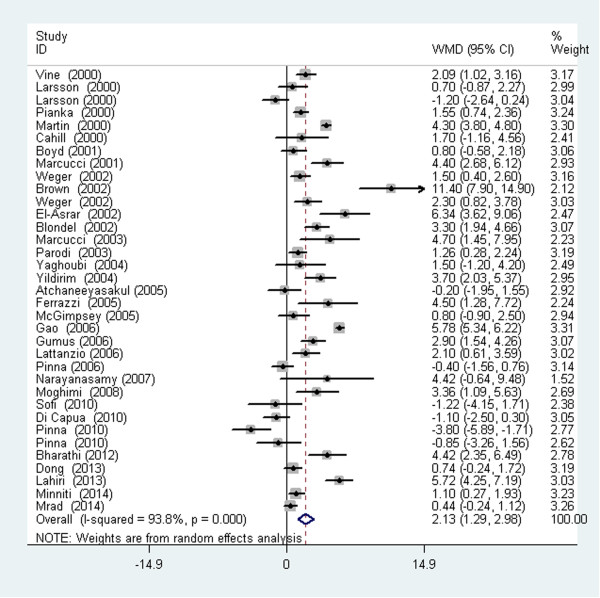

Plasma tHcy level outcomes

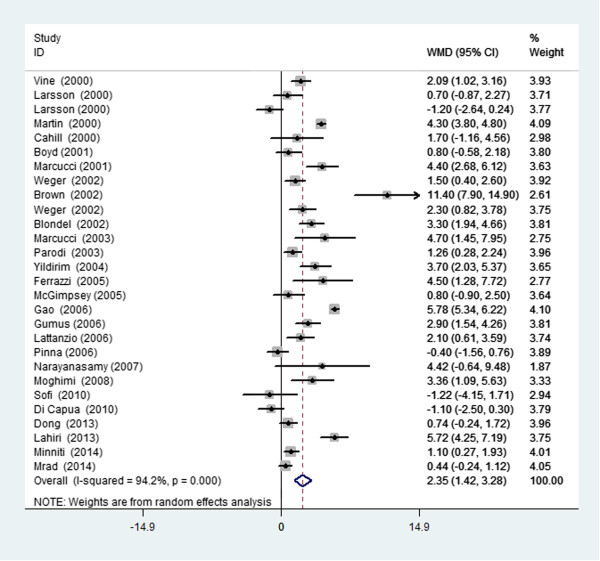

The analysis of the average plasma tHcy level of the RVO patients and controls in 34 studies revealed significant heterogeneity (I2 = 93.8%, P < 0.001) across the articles. Therefore, the data were pooled ina random-effects model. The meta-analysis of these data showed that the plasma tHcy level was significantly higher in the RVO patients than in the controls (WMD =2.13 μmol/L; 95% CI: 1.29–2.98, P < 0.001, Figure 2). Table 2 shows the detailed results stratified by the characteristics of the study. Overall, the plasma tHcy level was significantly higher in the RVO patients than in the control subjects, and this was consistently observed in each subgroup. Moreover, there was evidence of heterogeneity in all subgroups. Table 2 presents the results of the meta-regression analysis of the influence of the key characteristics of the studies (subgroup factors) on heterogeneity. After the exclusion of low-quality studies, the random-effects estimates were not changed substantially, suggesting a high stability of the meta-analysis results (WMD =2.35 μmol/L; 95% CI: 1.42–3.28, P < 0.001, Figure 3). With regard to the plasma tHcy level outcomes, Begg’s rank correlation test and Egger’s linear regression test provided little evidence of publication biases among the studies (Begg, P =0.091; Egger, P =0.051).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the average plasma tHcy level of the RVO patients and controls. WMD weighted mean difference, CI confidence interval. (Larsson et al. [29]): Data presented for two age groups: <50 years and >50 years.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of pooled estimates for the mean plasma tHcy in the cases compared with the controls

| Subgroup | Studies (n) | WMD (95%CI) | Test for overall effect | Study heterogeneity | Pfor meta-regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ 2 | P | I 2 | |||||

| Overnight fast | 0.269 | ||||||

| Yes | 28 | 2.41 (1.41, 3.41) | Z =4.71, P <0.001 | 481.24 | <0.001 | 94.4% | |

| No | 7 | 1.20 (0.25, 2.16) | Z =2.46, P =0.014 | 23.70 | 0.001 | 74.7% | |

| Diagnosis | 0.343 | ||||||

| RVOa | 18 | 2.56 (1.39, 3.72) | Z =4.31, P <0.001 | 222.86 | <0.001 | 92.4% | |

| CRVO | 17 | 1.67 (0.39, 3.00) | Z =2.55, P =0.011 | 314.88 | <0.001 | 94.9% | |

| Source of cases | 0.696 | ||||||

| Hospital records | 9 | 1.60 (0.47, 2.74) | Z =2.76, P =0.006 | 52.86 | <0.001 | 84.9% | |

| Consecutive patients | 26 | 2.24 (1.25, 3.23) | Z =4.44, P <0.001 | 401.13 | <0.001 | 93.8% | |

| Adjusting factors | 0.245 | ||||||

| NA | 1 | 4.30 (3.80, 4.80) | Z =17.00, P <0.001 | - | - | - | |

| Age | 10 | 1.33 (0.47, 2.18) | Z =3.05, P =0.002 | 32.23 | <0.001 | 72.1% | |

| Age, sex | 24 | 2.34 (1.19, 3.50) | Z =3.98, P <0.001 | 409.41 | <0.001 | 94.4% | |

aRVO subgroup includes CRVO, BRVO and others (e.g., hemi-retinal, hemispheric, macular).

tHcy = total homocysteine; WMD = weighted mean differences; CI = confidence interval; RVO = retinal vein occlusion; CRVO = central retinal vein occlusion.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the average plasma tHcy level of the RVO patients and controls after omitting the low-quality studies. WMD weighted mean difference, CI confidence interval.

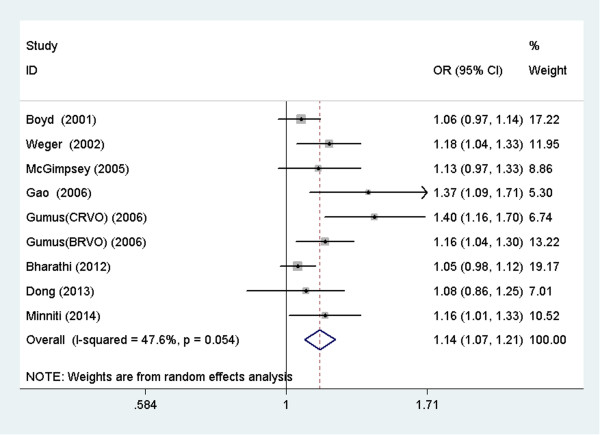

Association between plasma tHcy and RVO

We identified nine studies that reported an association between tHcy and RVO. As shown in Figure 4, a 1 μmol/L increase in the plasma tHcy level was associated with an OR of 1.14 (95% CI: 1.07–1.21) in the random-effects model, showing a statistically significant association between tHcy and the risk of RVO. The heterogeneity was statistically insignificant (I2 = 47.6%; P =0.054).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the risk estimates of the association between plasma tHcy and RVO. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval.

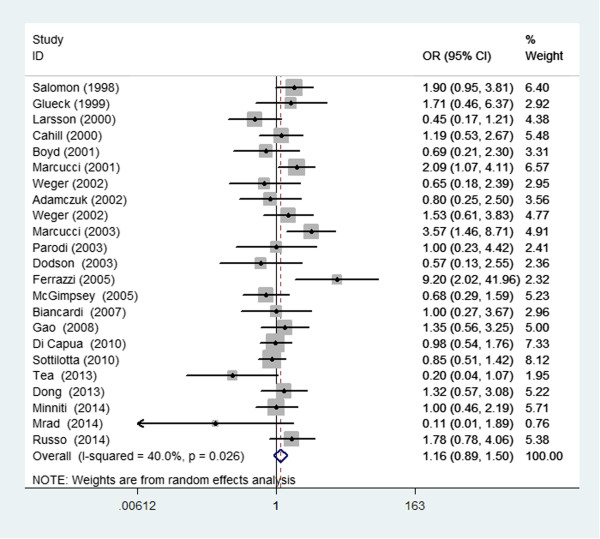

Association between the MTHFR C677T genotype and RVO

The pooled ORs with their respective 95% CIs and the result of the heterogeneity test are presented in Table 3 and Figure 5. Overall, there was no evidence of a significant association between the MTHFR C677T genotype and RVO in any genetic model tested (TT VS. CC/CT: OR = 1.16, 95% CI =0.89–1.50; CC VS. TT/CT: OR = 1.02, 95% CI =0.73–1.41; TT VS. CC: OR = 1.30, 95% CI =0.85–1.98; CT VS. CC: OR = 1.22, 95% CI = 0.90–1.66). The I2 statistic indicated substantial between-study heterogeneity in all genetic models tested. For MTHFR, the Begg’s test and Egger’s test also showed little evidence of publication biases among the studies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Analyses of the MTHFR C677T genotype and RVO

| Compared genotype | No. of studies | OR (95% CI) | P | Heterogeneity | PEgger’s test a | PBegg’s test b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x 2 | I 2 | P | ||||||

| TT VS. CC/CT | 23 | 1.16 (0.89–1.50) | 0.268 | 36.66 | 40.0% | 0.026 | 0.551 | 1.000 |

| CC VS. TT/CT | 14 | 0.77 (0.57,1.05) | 0.098 | 37.78 | 65.6% | <0.001 | 0.510 | 0.584 |

| TT VS. CC | 14 | 1.30 (0.85,1.98) | 0.223 | 28.78 | 54.8% | 0.007 | 0.056 | 0.063 |

| CT VS. CC | 14 | 1.22 (0.90,1.66) | 0.202 | 34.8 | 62.6% | 0.001 | 0.109 | 0.101 |

a P Egger’s test = the P value for Egger’s test.

b P Begg’s test = the P value for Begg’s test.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the risk estimates of the association between the MTHFR C677T genotype and RVO (recessive model, TT vs. TC/CC). OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis evaluated the relationship among plasma tHcy, the MTHFR C677Tgenotype, and RVO, and it included only case–control studies. The data provide a greater ability to assess the potential correlation between the aforementioned factors. We combined the effect sizes of 34 studies, which compared plasma tHcy levels between RVO patients and controls, in a random-effects model. The results demonstrated that the plasma tHcy level was significantly higher in the RVO patients than in the controls, with a pooled WMD of 2.13 μmol/L (95% CI: 1.29–2.98). A meta-analysis of data collected before September 2009revealed that the mean tHcy in the cases was 2.8 μmol/L (95% CI: 1.8–3.7) greater than in the controls [15]. Our findings are consistent with those of the earlier meta-analysis. Of note, when we analyzed the association between plasma tHcy and RVO, we found that a 1 μmol/L increase in the plasma tHcy level was associated with an OR of 1.14. Moreover, in the present meta-analysis, in an attempt to produce robust results, we performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses based on various characteristics of the study. The results of the subgroup and sensitivity analyses did not materially alter the pooled results, thereby supporting the robustness of our main finding. The possible mechanisms by which tHcy may contribute to RVO include the activation of factor V, the increased oxidation of low-density lipoprotein, the inhibition of plasminogen activator binding, and the activation of protein C [62].

The previous meta-analysis investigated the association between the MTHFR C677T genotype and RVO and found no association between the homozygosity of the TT genotype or RVO. The authors speculated that one possible cause of this lack of association was the modest number of studies included in the meta-analysis. However, with the added statistical power of 1,682 cases, the present meta-analysis also found no significant association between the MTHFR C677T genotype and RVO under all genetic models. Genetic factors are not the only factors capable of increasing the tHcy level; demographic and lifestyle factors, such as age, gender, folate intake, smoking status, vitamin B levels, systemic vascular diseases, and use of antihypertensive medications, can affect the plasma tHcy level [63].

The present meta-analysis identified substantial heterogeneity among the studies. This was not surprising, given the differences in the characteristics of the populations, data collection methods, ethnic populations, sample size, and sources of the cases. Whenever significant heterogeneity was present, a subgroup analysis was conducted, and a random-effects model was used to pool the results. However, our attempts to identify homogeneous subsets largely failed in the subgroup analysis, with heterogeneity remaining in all the subgroups in the studies. The meta-regression analysis also failed to identify the main sources of the heterogeneity. Several factors might account for the heterogeneity. First, environmental exposure and diet might play roles [63]. Second, some unpublished, eligible publications were unavailable for inclusion in the present meta-analysis, and this might have affected the results. Thus, the results should be considered with caution.

The previous meta-analysis analyzed data from 25 case–control studies and found that plasma tHcy level was relatively higher in RVO patients compared with controls [15]. The authors also found no association between the MTHFR C677T genotype and RVO. However, the meta-analysis contained a number of weaknesses. First, the authors reported the difference in the plasma tHcy level between the cases and controls, but not the dose-effect relationship between tHcy and RVO. In the present meta-analysis, we found that a 1 μmol/L increase in the plasma tHcy level was associated with an OR of 1.14. In addition, the previous meta-analysis did not have rigorous inclusion criteria [15]. For example, they included a case series study, and they only indirectly compared the cases and controls [64].

The results of the present meta-analysis must be interpreted cautiously in light of the strengths and limitations of the included studies. A major strength of this study is the enlarged sample size, as compared to the previous meta-analysis, and we added 17 newly published case–control studies, which provides enhanced statistical power and offers more precise and reliable effect estimates. Furthermore, we only included the case–control studies and no other studies. In addition, the methodological issues for the meta-analysis, such as publication bias and the stability of results, were well investigated. Our meta-analysis also has several limitations. One potential limitation is the substantial heterogeneity observed among the studies. Second, the case–control study design means that the assessment of tHcy in patients at varying time intervals after the occlusive vascular event is methodologically weak. The vascular occlusive event itself could increase the tHcy concentration. Third, to avoid publication bias, we performed not only an electronic search but also a manual search to identify all potentially relevant papers, including published and non-published sources. Unfortunately, we may have failed to include some papers, especially those published in other languages. Publication bias may have resulted in an overestimate of the relationship between tHcy and RVO. Fourth, in some studies, age was not entirely matched between the case and control groups. There is some evidence that tHcy increases with age, which might have affected the pooled results. Fifth, the controls were not uniformly defined. This was a meta-analysis of case–control studies, and no studies were population-based. Thus, some inevitable selection biases might exist in the results, and they may not be representative of the general population.

Conclusions

In conclusion, despite these limitations, the current meta-analysis of observational studies suggests that an elevated level of plasma tHcy increases the risk of RVO. There was no evidence to suggest an association between the MTHFR C677T genotype and RVO. Despite these encouraging findings, the inherent limitations of the included studies should be considered, and conclusions drawn from our pooled results should be interpreted with caution.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. There are no sources of financial support to declare in this paper.

Authors’ contributions

All authors conceived of and designed the experimental protocol. DL collected the data. All authors were involved in the analysis. DL and MZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. XP and HS reviewed and revised the manuscript and produced the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dan Li, Email: lliddnn@163.com.

Minwen Zhou, Email: zmw8008@163.com.

Xiaoyan Peng, Email: drpengxy@163.com.

Huiyu Sun, Email: 563591810@qq.com.

References

- 1.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Meuer SM. The epidemiology of retinal vein occlusion: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:133–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cugati S, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Mitchell P. Ten-year incidence of retinal vein occlusion in an older population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:726–732. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.5.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risk factors for branch retinal vein occlusion. The eye disease case–control study groupAm J Ophthalmol 1993, 116:286–296. [PubMed]

- 4.Lip PL, Blann AD, Jones AF, Lip GY. Abnormalities in haemorheological factors and lipoprotein (a) in retinal vascular occlusion: implications for increased vascular risk. Eye (Lond) 1998;12(Pt 2):245–251. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez F, Furio E, Fabia MJ, Perez AV, Gonzalez-Albert V, Rojo-Martinez G, Martinez-Larrad MT, Mena-Martin FJ, Soriguer F, Serrano-Rios M, Chaves FJ, Martín-Escudero JC, Redón J, García-Fuster MJ. Risk factors associated with retinal vein occlusion. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68:871–881. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stem MS, Talwar N, Comer GM, Stein JD. A longitudinal analysis of risk factors associated with central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sofi F, Marcucci R, Fedi S, Giambene B, Sodi A, Menchini U, Gensini GF, Abbate R, Prisco D. High lipoprotein (a) levels are associated with an increased risk of retinal vein occlusion. Atherosclerosis. 2010;210:278–281. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varga EA, Sturm AC, Misita CP, Moll S. Cardiology patient pages. Homocysteine and MTHFR mutations: relation to thrombosis and coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;111:e289–e293. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165142.37711.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin SC, Rauz S, Marr JE, Martin N, Jones AF, Dodson PM. Plasma total homocysteine and retinal vascular disease. Eye (Lond) 2000;14(Pt 4):590–593. doi: 10.1038/eye.2000.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahiri KD, Dutta J, Datta H, Das HN. Hyperhomocysteinemia, as an independent risk factor for retinal venous occlusion in an Indian population. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28:61–64. doi: 10.1007/s12291-012-0238-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmon DL, Woodside JV, Yarnell JW, McMaster D, Young IS, McCrum EE, Gey KF, Whitehead AS, Evans AE. The common ‘thermolabile’ variant of methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase is a major determinant of mild hyperhomocysteinaemia. QJM. 1996;89:571–577. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.8.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacques PF, Bostom AG, Williams RR, Ellison RC, Eckfeldt JH, Rosenberg IH, Selhub J, Rozen R. Relation between folate status, a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, and plasma homocysteine concentrations. Circulation. 1996;93:7–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bottiglieri T, Parnetti L, Arning E, Ortiz T, Amici S, Lanari A, Gallai V. Plasma total homocysteine levels and the C677T mutation in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene: a study in an Italian population with dementia. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:2013–2023. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(01)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sottilotta G, Siboni SM, Latella C, Oriana V, Romeo E, Santoro R, Consonni D, Trapani Lombardo V. Hyperhomocysteinemia and C677T MTHFR genotype in patients with retinal vein thrombosis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2010;16:549–553. doi: 10.1177/1076029609348644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGimpsey SJ, Woodside JV, Cardwell C, Cahill M, Chakravarthy U. Homocysteine, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism, and risk of retinal vein occlusion: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1778–1787. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cahill MT, Stinnett SS, Fekrat S. Meta-analysis of plasma homocysteine, serum folate, serum vitamin B(12), and thermolabile MTHFR genotype as risk factors for retinal vascular occlusive disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:1136–1150. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00571-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minniti G, Calevo MG, Giannattasio A, Camicione P, Armani U, Lorini R, Piana G. Plasma homocysteine in patients with retinal vein occlusion. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2014;24:735–743. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong N, Wang B, Chu L, Xiao L. Plasma homocysteine concentrations in the acute phase after central retinal vein occlusion in a Chinese population. Curr Eye Res. 2013;38:1153–1158. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2013.809124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tea S, Barrali M, Racadot E, Delbosc B. Evaluation of coagulopathies and fibrinolytic abnormalities in central retinal vein occlusion in patients under 60 years of age. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2013;36:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mrad M, Wathek C, Saleh MB, Baatour M, Rannen R, Lamine K, Gabsi S, Gritli N, Fekih-Mrissa N. Association of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (A1298C and C677T) polymorphisms with retinal vein occlusion in Tunisian patients. Transfus Apher Sci. 2014;50:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuhara H, Steinmaus C, Cohen SE, Corley DA, Tei Y, Buffler PA. Is diabetes mellitus an independent risk factor for colon cancer and rectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol. 1922;2011(106):1911–1921. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W, Zhou M, Huang W, Chen S, Zhang X. Lack of association of apolipoprotein E (Apo E) epsilon2/epsilon3/epsilon4 polymorphisms with primary open-angle glaucoma: a meta-analysis from 1916 cases and 1756 controls. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glueck CJ, Bell H, Vadlamani L, Gupta A, Fontaine RN, Wang P, Stroop D, Gruppo R. Heritable thrombophilia and hypofibrinolysis. Possible causes of retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:43–49. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vine AK. Hyperhomocysteinemia: a risk factor for central retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:640–644. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsson J, Hultberg B, Hillarp A. Hyperhomocysteinemia and the MTHFR C677T mutation in central retinal vein occlusion. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:340–343. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078003340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pianka P, Almog Y, Man O, Goldstein M, Sela BA, Loewenstein A. Hyperhomocystinemia in patients with nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, central retinal artery occlusion, and central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1588–1592. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cahill M, Karabatzaki M, Meleady R, Refsum H, Ueland P, Shields D, Mooney D, Graham I. Raised plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for retinal vascular occlusive disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:154–157. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyd S, Owens D, Gin T, Bunce K, Sherafat H, Perry D, Hykin PG. Plasma homocysteine, methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase C677T and factor II G20210A polymorphisms, factor VIII, and VWF in central retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1313–1315. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.11.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcucci R, Bertini L, Giusti B, Brunelli T, Fedi S, Cellai AP, Poli D, Pepe G, Abbate R, Prisco D. Thrombophilic risk factors in patients with central retinal vein occlusion. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:772–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weger M, Stanger O, Deutschmann H, Temmel W, Renner W, Schmut O, Semmelrock J, Haas A. Hyperhomocyst(e)inemia and MTHFR C677T genotypes in patients with central retinal vein occlusion. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240:286–290. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adamczuk YP, Iglesias VM, Martinuzzo ME, Cerrato GS, Forastiero RR. Central retinal vein occlusion and thrombophilia risk factors. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2002;13:623–626. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown BA, Marx JL, Ward TP, Hollifield RD, Dick JS, Brozetti JJ, Howard RS, Thach AB. Homocysteine: a risk factor for retinal venous occlusive disease. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:287–290. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00923-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weger M, Stanger O, Deutschmann H, Temmel W, Renner W, Schmut O, Quehenberger F, Semmelrock J, Haas A. Hyperhomocyst(e)inemia, but not methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T mutation, as a risk factor in branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1105–1109. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abu EA, Abdel GA, Al-Amro SA, Al-Attas OS. Hyperhomocysteinemia and retinal vascular occlusive disease. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2002;12:495–500. doi: 10.1177/112067210201200608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcucci R, Giusti B, Betti I, Evangelisti L, Fedi S, Sodi A, Cappelli S, Menchini U, Abbate R, Prisco D. Genetic determinants of fasting and post-methionine hyperhomocysteinemia in patients with retinal vein occlusion. Thromb Res. 2003;110:7–12. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(03)00293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parodi MB, Di Crecchio L. Hyperhomocysteinemia in central retinal vein occlusion in young adults. Semin Ophthalmol. 2003;18:154–159. doi: 10.1076/soph.18.3.154.29809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dodson PM, Haynes J, Starczynski J, Farmer J, Shigdar S, Fegan G, Johnson RJ, Fegan C. The platelet glycoprotein Ia/IIa gene polymorphism C807T/G873A: a novel risk factor for retinal vein occlusion. Eye (Lond) 2003;17:772–777. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yaghoubi GH, Madarshahian F, Mosavi M. Hyperhomocysteinaemia: risk of retinal vascular occlusion. East Mediterr Health J. 2004;10:633–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yildirim C, Yaylali V, Tatlipinar S, Kaptanoglu B, Akpinar S. Hyperhomocysteinemia: a risk factor for retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmologica. 2004;218:102–106. doi: 10.1159/000076144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atchaneeyasakul LO, Trinavarat A, Bumrungsuk P, Wongsawad W. Anticardiolipin IgG antibody and homocysteine as possible risk factors for retinal vascular occlusive disease in thai patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:211–215. doi: 10.1007/s10384-005-0190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrazzi P, Di Micco P, Quaglia I, Rossi LS, Bellatorre AG, Gaspari G, Rota LL, Lodigiani C. Homocysteine, MTHFR C677T gene polymorphism, folic acid and vitamin B 12 in patients with retinal vein occlusion. Thromb J. 2005;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-9560-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGimpsey SJ, Woodside JV, Bamford L, Gilchrist SE, Graydon R, McKeeman GC, Young IS, Hughes AE, Patterson CC, O’Reilly D, McGibbon D, Chakravarthy U. Retinal vein occlusion, homocysteine, and methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase genotype. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4712–4716. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao W, Wang YS, Zhang P, Wang HY. Hyperhomocysteinemia and low plasma folate as risk factors for central retinal vein occlusion: a case–control study in a Chinese population. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:1246–1249. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gumus K, Kadayifcilar S, Eldem B, Saracbasi O, Ozcebe O, Dundar S, Kirazli S. Is elevated level of soluble endothelial protein C receptor a new risk factor for retinal vein occlusion? Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006;34:305–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lattanzio R, Sampietro F, Ramoni A, Fattorini A, Brancato R, D’Angelo A. Moderate hyperhomocysteinemia and early-onset central retinal vein occlusion. Retina. 2006;26:65–70. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinna A, Carru C, Zinellu A, Dore S, Deiana L, Carta F. Plasma homocysteine and cysteine levels in retinal vein occlusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4067–4071. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Narayanasamy A, Subramaniam B, Karunakaran C, Ranganathan P, Sivaramakrishnan R, Sharma T, Badrinath VS, Roy J. Hyperhomocysteinemia and low methionine stress are risk factors for central retinal venous occlusion in an Indian population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1441–1446. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Biancardi AL, Gadelha T, Borges WI, Vieira DMHJ, Spector N. Thrombophilic mutations and risk of retinal vein occlusion. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2007;70:971–974. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27492007000600016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moghimi S, Najmi Z, Faghihi H, Karkhaneh R, Farahvash MS, Maghsoudipour M. Hyperhomocysteinemia and central retinal vein occlusion in Iranian population. Int Ophthalmol. 2008;28:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sofi F, Marcucci R, Bolli P, Giambene B, Sodi A, Fedi S, Menchini U, Gensini GF, Abbate R, Prisco D. Low vitamin B6 and folic acid levels are associated with retinal vein occlusion independently of homocysteine levels. Atherosclerosis. 2008;198:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Capua M, Coppola A, Albisinni R, Tufano A, Guida A, Di Minno MN, Cirillo F, Loffredo M, Cerbone AM. Cardiovascular risk factors and outcome in patients with retinal vein occlusion. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010;30:16–22. doi: 10.1007/s11239-009-0388-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pinna A, Zinellu A, Franconi F, Solinas G, Carru C. Decreased plasma cysteinylglycine and taurine levels in branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmic Res. 2010;43:26–32. doi: 10.1159/000246575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pinna A, Zinellu A, Franconi F, Carru C. Plasma thiols and taurine levels in central retinal vein occlusion. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35:644–650. doi: 10.3109/02713681003698863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bharathi DS, Suganeswari G, Sharma T, Thennarasu M, Angayarkanni N. Homocysteine induces oxidative stress in young adult central retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:1122–1126. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Russo PD, Damante G, Pasca S, Turello M, Barillari G. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014. Thrombophilic mutations as risk factor for retinal vein occlusion: a case–control study. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blondel J, Glacet-Bernard A, Bayani N, Blacher J, Lelong F, Nordmann JP, Coscas G, Soubrane G. Retinal vein occlusion and hyperhomocysteinemia. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2003;26:249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salomon O, Moisseiev J, Rosenberg N, Vidne O, Yassur I, Zivelin A, Treister G, Steinberg DM, Seligsohn U. Analysis of genetic polymorphisms related to thrombosis and other risk factors in patients with retinal vein occlusion. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1998;9:617–622. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199810000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hajjar KA. Homocysteine-induced modulation of tissue plasminogen activator binding to its endothelial cell membrane receptor. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2873–2879. doi: 10.1172/JCI116532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nurk E, Tell GS, Vollset SE, Nygard O, Refsum H, Nilsen RM, Ueland PM. Changes in lifestyle and plasma total homocysteine: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:812–819. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loewenstein A, Goldstein M, Winder A, Lazar M, Eldor A. Retinal vein occlusion associated with methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1817–1820. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pre-publication history

- The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2415/14/147/prepub