Abstract

Background: the oldest old (85+) pose complex medical challenges. Both underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis are claimed in this group.

Objective: to estimate diagnosis, prescribing and hospital admission prevalence from 2003/4 to 2011/12, to monitor trends in medicalisation.

Design and setting: observational study of Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) electronic medical records from general practice populations (eligible; n = 27,109) with oversampling of the oldest old.

Methods: we identified 18 common diseases and five geriatric syndromes (dizziness, incontinence, skin ulcers, falls and fractures) from Read codes. We counted medications prescribed ≥1 time in all quarters of studied years.

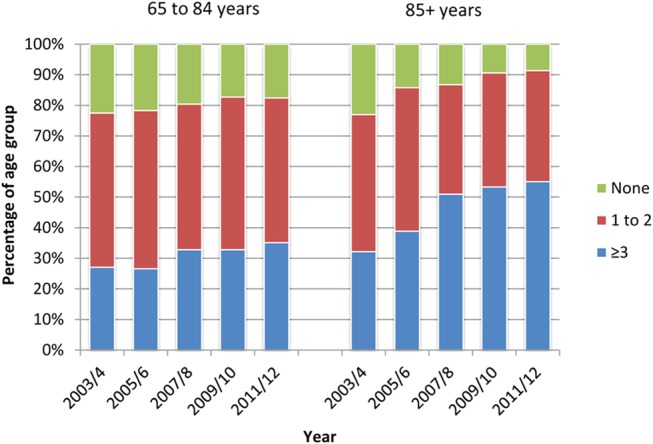

Results: there were major increases in recorded prevalence of most conditions in the 85+ group, especially chronic kidney disease (stages 3–5: prevalence <1% rising to 36.4%). The proportions of the 85+ group with ≥3 conditions rose from 32.2 to 55.1% (27.1 to 35.1% in the 65–84 year group). Geriatric syndrome trends were less marked. In the 85+ age group the proportion receiving no chronically prescribed medications fell from 29.6 to 13.6%, while the proportion on ≥3 rose from 44.6 to 66.2%. The proportion of 85+ year olds with ≥1 hospital admissions per year rose from 27.6 to 35.4%.

Conclusions: there has been a dramatic increase in the medicalisation of the oldest old, evident in increased diagnosis (likely partly due to better record keeping) but also increased prescribing and hospitalisation. Diagnostic trends especially for chronic kidney disease may raise concerns about overdiagnosis. These findings provide new urgency to questions about the appropriateness of multiple diagnostic labelling.

Keywords: oldest, prevalence, admission, prescribing, kidney, older people

Introduction

The numbers of ‘oldest old’ people (≥85 years) in the UK will increase from 1.4 million in 2010 to 3.5 million by 2035 [1], with similar trends globally [2]. The oldest old people are intensive users of acute hospitals, with rates of emergency admission nearly 10 times higher than those aged 20–49 years [3]. However, there are few data on prevalence or trends in diagnosed morbidity or treatment rates in the UK's oldest old.

Diagnosing and treating the oldest patients is challenging. Distinguishing between incidental age-related changes, treatable disease and the process of dying can be a vexed issue [4]. Comorbidity and frailty are common and the oldest old people are often excluded from clinical trials [5] so the benefits and risks of diagnosis and intervention are often unknown. Evidence-based guidelines frequently prove contradictory and unworkable in the oldest old [6]. Perhaps because of these complexities, there have been claims of both underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis in this group. Underdiagnosis in general practice has been reported for conditions including dementia [7], diabetes [8] and hypertension [9]. At the same time, overdiagnosis is causing major concern especially for chronic kidney disease (CKD) [10], chronic obstructive airways disease [11], certain cancers [12], hypertension, osteoporosis, and early dementia [13, 14]. Overdiagnosis can lead to overintervention and questionable benefits for some patients [14], especially older patients. Overdiagnosis often arises from imaging or laboratory findings of deviations from ‘normal’ levels [15], yet normal is poorly defined in the oldest old.

In England, the introduction of the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF) in 2004 financially incentivised general practitioners (GPs) to systematically electronically record the presence of certain chronic diseases and the achievement of associated quality indicators [16] that may have influenced diagnostic rates. Recently announced changes to the GP contract in England have highlighted the frail elderly, raising further questions about appropriate diagnosis and treatment in the oldest old.

We aimed to estimate trends in diagnosed disease and geriatric syndromes, polypharmacy and hospital admissions from 2003–04 to 2011–12, using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). A major advantage is that CPRD includes patients in residential and nursing homes, with essentially complete inclusion of the frail and dependent, who are often underrepresented in volunteer-based studies.

Methods

Cohort identification

The oldest old make up a small proportion of the overall CPRD patient population. To maximise statistical power, we selected a weighted sample with over-representation of the oldest old (but weighted all analyses back to the UK population structure 2011 to obtain representative estimates—see statistical analysis). We included CPRD patients reaching age 100 years or more from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2011, in the July 2012 CPRD data snapshot. Each centenarian was matched (one to one for females, one to two for males) to younger patients by practice, gender and calendar year in the following age-groups: 65–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89, 90–94, 95 to 99 years. Additional data included Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality data for practices in the CPRD linkage scheme.

Coding of disease

We studied 15 common conditions from studies of QOF diseases by Salisbury et al. [17] and others [18], excluding learning disability and obesity. Any patient with a QOF diagnosis (QOF business rules Version 18, October 2010) [19] and (where appropriate) a drug Read code and appearing in the records up to 15 years before the end of the analysis year (e.g. for fiscal year 2003–04, from April 1989) was selected. The Mental Health (major disorder) QOF group was the only diagnosis potentially identified solely on the presence of a drug code (lithium) or relevant diagnostic codes, and three other conditions (asthma, epilepsy and hypothyroidism) required accompanying drug codes as well as the relevant diagnosis code. Patients who received relevant diagnoses within our study periods (i.e. the previous 15 years for diseases and 5 years for geriatric syndromes) were included in estimates as having the condition, even if a subsequent resolved code was also present (resolved codes were rare: e.g. for hypertension only 1.2% of diagnosed cases also had a resolved code in the whole database).

Osteoarthritis, osteoporosis (at the time not included as QOF) and anaemia were added to this measure as common disabling conditions of ageing.

Multi-morbidity was defined as ≥3 conditions from our 15 QOF and three additional disorders (range 0–18). Five geriatric syndromes were identified from Read codes for dizziness (including vertigo and syncope), incontinence (urinary and faecal), skin ulcers (including bed sores), falls and fractures. Medical literature was examined to generate search terms by two clinicians blinded to each other's work, with a third clinical reviewer arbitrating disagreements. Syndromes were coded as present if relevant read or product coding appeared in records up to 5 years before the end of the analysis year (e.g. for fiscal year 2003–04, from April 1999), to exclude historical diagnoses with no recent mention.

Coding of polypharmacy

We included substances prescribed with predominantly systemic effects (oral, sublingual, transdermal, subcutaneous, intramuscular, intravenous, rectal), the vast majority of which were oral (97.7%). A count of long-term (chronic) prescribed drugs including drugs prescribed at least once per quarter for all four-quarters of each studied year, to exclude short-term prescriptions.

Statistics

We have estimated outcomes for fiscal years 2003–04 to 2011–12 for the 65–84 year olds and 85+ year olds separately, to capture a period before and after the introduction of QOF. For simplicity, we tabulate estimates in 2003–04, 2007–08 and 2011–12, with intermediate years presented in figures for selected measures.

Our weighted database was built up by adding patients who became centenarians in each year from 2002 to 2011, with younger controls then added for each centenarian (see Cohort Identification above). For the 2003–04 estimates, the subsample added by CPRD to our database in 2002 and 2003 only were used, to avoid including patients added in subsequent years, which would have introduced survivor biases. We used the same approach for later periods (i.e. patients added 2006 and 2007 only for 2007–08 estimates, patients added 2010 and 2011 for 2011–12 estimates). Only data for the periods during which patients were ‘actively’ registered with practices were included in analyses (i.e. we used data from current registration date up to the date of last data collection, transfer out of practice or death). Current registration was ascertained on the mid-point of the studied fiscal years (e.g. 30 September 2003 for 2003–04 estimates). A small number of apparently ‘non-active’ patients (i.e. those with no clinical or therapy records for the previous 3 years) were also excluded. This rule excluded 28 patients in 2003–04, 48 in 2007–08 and 71 patients in 2011–12, with 4,556, 5,574 and 6,223 eligible patients included, respectively. For hospital admission statistics, 58% (338/578) of practices were linked, covering England only. Data were analysed using Stata 13.

To correct the oversampling of the oldest old, all estimates were weighted back to the UK 2011 population structure (or the population of England 2011 for HES-England analyses). Weights were computed from the ratio of the number of people in the population of the UK in 2011 (ONS estimates) in each 5-year age group for men and women separately divided by the numbers of CPRD patients in each similar age–gender group in our analysis, for each fiscal year separately. Weighted estimates were computed using the STATA Survey commands which in this case provide the estimates we would have got if our patient group had the same age structure as the UK in 2011, thus removing any bias from the over-representation of the very elderly or changes in population structure.

We measured absolute percentage point differences in prevalence between 2003–04 and 2011–12, as some trends appear non-linear and modelled per year changes sometimes produced misleading results.

Findings

From 2002–03 to 2011–12, 27,109 patients met eligibility criteria and are included in graphs, with 16,353 included in the three exemplar years for tables (2003–04, 2007–08 and 2011–12). Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Table S1 describes the study sample (see Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendices S1–S4). In the 85+ group, 67% of the samples were women compared with 54% in the 65–84 age group (all estimates weighted to the UK 2011 population structure—see methods). Median lengths of registration in the CPRD data for the 85+ group rose from 7.6 years in 2003–04 to 12.2 years in 2011–12, but were more stable in the 65–84 group (12.5 and 12.7 years, respectively).

The prevalence of 18 common chronic diseases was estimated for those aged 65–84 and 85+ years separately (Table 1). In the oldest old, there were large increases in prevalence for diabetes (8.3%; 95% CI: 7.1–9.5%), osteoporosis (9.8%; 95% CI: 8.3–11.3%), osteoarthritis (10.3%; 95% CI: 8.0–12.6%) and hypertension (14.6%; 95% CI: 12.2–17.0%). For CKD, the prevalence rose from <1–36.4%. There were more modest changes in most of these conditions in the 65–84 year olds. Only heart failure showed a fall in prevalence in the 85+ group (absolute change of −3.3%; 95% CI: −5.0 to −1.6%), but there were modest reductions for coronary heart disease and heart failure in the younger group. Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Figure S1 (a–d) show prevalence trends for heart failure, CKD (stages 3–5), diabetes and incontinence by age group. Trends appear approximately linear except for CKD, which shows a dramatic prevalence increase from 2005 to 2007.

Table 1.

Prevalence of recorded diagnoses by age-group and fiscal year (weighted to UK population structure 2011), with absolute change in prevalence from 2003–04 to 2011–12

| Disease | 65–84 years old |

85+ years old |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–04 % (95% CI) | 2007–08 % (95% CI) | 2011–12 % (95% CI) | Absolute difference % (95% CI) | 2003–04 % (95% CI) | 2007–08 % (95% CI) | 2011–12 % (95% CI) | Absolute difference % (95% CI) | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 39.4 (36.5, 42.4) | 43.6 (41.2, 46.1) | 44.2 (41.9, 46.5) | 4.8 (2.0, 7.6) | 34.7 (31.6, 37.8) | 45.7 (42.9, 48.5) | 49.3 (47.0, 51.6) | 14.6 (12.2, 17.0) |

| Arial fibrillation | 6.2 (5.1, 7.6) | 7.5 (6.4, 8.6) | 7.0 (6.0, 8.0) | 0.8 (−0.7, 2.3) | 11.7 (10.0, 13.6) | 15.2 (13.5, 17.1) | 15.7 (14.0, 17.5) | 4.0 (2.3, 5.7) |

| Coronary heart disease | 18.8 (16.8, 21.0) | 14.7 (13.2, 16.4) | 15.0 (13.3, 16.8) | −3.8 (−5.9, −1.7) | 17.6 (15.4, 20.0) | 21.9 (19.9, 24.1) | 20.8 (19.1, 22.6) | 3.2 (1.2, 5.2) |

| Heart failure | 5.3 (4.3, 6.5) | 3.7 (3.0, 4.5) | 2.7 (2.1, 3.3) | −2.6 (−3.8, −1.4) | 12.2 (10.4, 14.2) | 11.2 (9.7, 13.0) | 8.9 (7.7, 10.3) | −3.3 (−5.0, −1.6) |

| Stroke | 8.9 (7.6, 10.5) | 7.5 (6.3, 8.8) | 7.5 (6.6, 8.6) | −1.4 (−3, 0.2) | 14.7 (12.8, 16.8) | 16.3 (14.4, 18.4) | 15.8 (14.3, 17.5) | 1.1 (−0.8, 3) |

| Cancer | 7.5 (6.2, 9.0) | 8.5 (7.4, 9.8) | 9.4 (8.1, 10.9) | 1.9 (0.4, 3.4) | 7.3 (6.0, 8.9) | 10.2 (8.7, 11.9) | 11.0 (9.6, 12.6) | 3.7 (2.3, 5.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||||||||

| Stages 3–5 | 0.2 (0.1, 0.6) | 14.5 (12.9, 16.2) | 16.0 (14.4, 17.9) | 15.8 (14.4, 17.2) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.3) | 27.4 (24.8, 30.1) | 36.4 (33.9, 39.1) | 36.4 (34.8, 38.0) |

| Respiratory | ||||||||

| Asthma | 8.3 (7.0, 9.9) | 9.6 (8.3, 11.1) | 10.5 (9.1, 12.2) | 2.2 (0.6, 3.8) | 6.0 (4.7, 7.6) | 7.3 (6.1, 8.8) | 7.8 (6.7, 9.2) | 1.8 (0.6, 3) |

| COPD | 5.9 (4.7, 7.4) | 6.2 (5.2, 7.4) | 7.8 (6.7, 9.1) | 1.9 (0.5, 3.3) | 4.7 (3.6, 6.2) | 6.2 (5.1, 7.5) | 6.7 (5.6, 7.9) | 2.0 (0.9, 3.1) |

| Neuropsychiatric | ||||||||

| Dementia | 1.6 (1.1, 2.4) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.4) | 2.7 (2.1, 3.5) | 1.1 (0.2, 2) | 7.3 (6.0, 8.7) | 10.3 (8.9, 12.0) | 12.0 (10.6, 13.6) | 4.7 (3.1, 6.3) |

| Depression | 11.6 (10.0, 13.4) | 11.8 (10.4, 13.2) | 13.6 (12.2, 15.2) | 2.0 (0.1, 3.9) | 10.4 (8.6, 12.5) | 12.0 (10.6, 13.7) | 13.7 (12.1, 15.4) | 3.3 (1.6, 5) |

| Mental health (psychoses, schizophrenia, bipolar affective disease) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.8) | 1.4 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) | 0.4 (−0.2, 1) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) | 1.4 (1.0, 2.1) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.4) | 0.7 (0, 1.4) |

| Epilepsy | 1.1 (0.6, 1.8) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.6) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) | 0.1 (−0.5, 0.7) | 1.1 (0.7, 2.0) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.4) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.5) | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.3) |

| Endocrine | ||||||||

| Diabetes | 6.9 (5.8, 8.2) | 12.1 (10.6, 13.8) | 14.2 (12.5, 16.0) | 7.3 (5.6, 9.0) | 3.4 (2.5, 4.6) | 8.9 (7.6, 10.4) | 11.7 (10.3, 13.3) | 8.3 (7.1, 9.5) |

| Hypothyroidism | 6.8 (5.6, 8.3) | 7.3 (6.3, 8.5) | 8.3 (7.2, 9.6) | 1.5 (−0.1, 3.1) | 6.3 (5.1, 7.9) | 9.1 (7.6, 10.8) | 11.0 (9.7, 12.6) | 4.7 (3.3, 6.1) |

| Additional common conditions | ||||||||

| Anaemia | 3.9 (3.1, 4.9) | 6.2 (5.2, 7.4) | 5.1 (4.1, 6.2) | 1.2 (−0.1, 2.5) | 8.7 (7.2, 10.5) | 11.4 (9.8, 13.2) | 11.9 (10.3, 13.5) | 3.2 (1.7, 4.7) |

| Osteoarthritis | 24.5 (22.2, 26.9) | 27.7 (25.6, 29.8) | 29.8 (27.6, 32.2) | 5.3 (2.8, 7.8) | 25.4 (22.8, 28.2) | 33.1 (30.5, 35.8) | 35.7 (33.4, 38.0) | 10.3 (8.0, 12.6) |

| Osteoporosis | 4.9 (3.9, 6.0) | 7.4 (6.4, 8.6) | 8.7 (7.5, 10.0) | 3.8 (2.3, 5.3) | 6.3 (5.1, 7.8) | 9.8 (8.3, 11.5) | 16.1 (14.3, 18.1) | 9.8 (8.3, 11.3) |

| Multi-morbidity | ||||||||

| ≥3 of above conditions | 27.1 (24.9, 29.4) | 32.8 (30.5, 35.1) | 35.1 (32.9, 37.4) | 8.0 (5.5, 10.6) | 32.2 (29.2, 35.3) | 50.9 (47.9, 53.9) | 55.1 (52.6, 57.5) | 22.9 (20.4, 25.3) |

The proportions of those aged 85+ years with three or more conditions increased from 32.2 to 55.1% compared with 27.1 to 35.1% in the younger group (Figure 1). Trends in geriatric syndrome prevalence were similar, but less marked (Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Table S2). Overall, the proportion of 85+ year olds with two or more geriatric syndromes increased from 17.8 to 24.5%, while there was no significant trend in the 65–84 age group.

Figure 1.

Prevalence (weighted to UK population structure 2011) of number of chronic diseases (of 18 in Table 1) by age group, from 2003–04 to 2011–12.

Trends in quantity of prescribing

The proportion of the oldest group chronically prescribed three or more items rose from 44.6 to 66.2% (21.6 percentage point increase 95% CI: 18.4–24.8%) compared with a change from 37.7 to 50.5% in the younger age group (12.8 percentage point increase, 95% CI: 9.5–16.1%)(Table 2). At the same time the proportions of patients on no medication fell, again more markedly in the oldest old.

Table 2.

Trends in number of chronic medications (weighted to UK population structure 2011) and hospital admissions (weighted to England population 2011) by age group and year, with absolute change in prevalence from 2003–04 to 2011–12

| 65–84 years |

85+ years |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–04 % (95% CI) | 2007–08 % (95% CI) | 2011–12 % (95% CI) | Absolute difference % (95% CI) | 2003–04 % (95% CI) | 2007–08 % (95% CI) | 2011–12 % (95% CI) | Absolute difference % (95% CI) | |

| Number of chronically prescribed medicines | ||||||||

| None | 34.3 (31.7, 37.1) | 27.6 (25.5, 29.8) | 24.2 (22.0, 26.6) | −10.1 (−13.0, −7.2) | 29.6 (26.7, 32.7) | 18.5 (16.0, 21.2) | 13.6 (11.9, 15.5) | −16 (−18.7, −13.3) |

| 1–2 | 28 (25.6, 30.4) | 26.2 (24.0, 28.6) | 25.3 (23.2, 27.5) | −2.7 (−5.7, 0.25) | 25.8 (23.1, 28.7) | 22.8 (20.5, 25.4) | 20.3 (18.3, 22.4) | −5.5 (−8.3, −2.7) |

| ≥3 | 37.7 (34.9, 40.5) | 46.2 (43.7, 48.7) | 50.5 (47.7, 53.3) | 12.8 (9.5, 16.1) | 44.6 (41.6, 47.6) | 58.7 (55.8, 61.6) | 66.2 (63.6, 68.6) | 21.6 (18.4, 24.8) |

| Any admission | 21.6 (18.9, 24.5) | 23.4 (21.1, 25.8) | 24.3 (22.0, 26.8) | 2.7 (−0.01, 5.4) | 27.6 (24.5, 31.0) | 34.9 (32.2, 37.7) | 35.4 (32.9, 37.9) | 7.8 (2.6, 10.4) |

| Emergency admission | 9.1 (7.5, 11.0) | 12.1 (10.5, 13.8) | 11.5 (10.0, 13.2) | 2.4 (0.3, 4.8) | 20.8 (18.1, 23.8) | 26.6 (24.3, 29.1) | 24.7 (22.6, 26.9) | 3.9 (1.5, 6.3) |

aNote: 2010 period calculated from November 2010 to October 2011 due to data availability. Estimates based on all patients in practices linked to HES (England only).

Trends in hospital admission

Across the studied years, for the oldest old, the proportion admitted at least once rose from 27.6 to 35.4% (difference 7.8%, 95% CI: 2.6–10.4%), but there was no significant change in the proportion of 65–84 year olds having one or more hospital admission (Table 2). However, for emergency admissions there were smaller trends for both age-groups.

Discussion

In this study of UK general practice, we found large-scale increases in many diagnoses from 2003–04 to 2011–12, especially in the oldest old. The proportion of the oldest old on chronically prescribed medication or admitted to hospital (in England) also rose markedly. Taken together the data indicate a major shift towards more intensive medicalisation of the oldest old.

Despite the many needs of the oldest old, there are few studies with which we can compare our results. Local studies using volunteer samples in Newcastle (aged exactly 85 at baseline) [20] and the MRC CFAS study [21] provide some overlaps. However, there are no comparable analyses of national trends in the oldest old, free of responder and loss to follow-up biases, which can severely distort data on the frail elderly [22, 23]. Studies of dementia and of diabetes in those aged 65+ also in CPRD showed similar trends to those reported here [24, 25]. The reported trend in heart failure is supported by a recent English study finding of reduced rates of hospital admissions and a fall in the practice-reported prevalence of QOF diagnosed heart failure of 7.9% between 2006 and 2010 [26].

Studies of emergency admission trends [3] provide broadly similar results at least for the earlier part of our studied period, confirming that rising emergency admission rates result partly from increasing proportions of the 85+ age group being admitted to hospitals and not just increasing re-admissions of the same patients.

Our largest reported diagnostic trend was for CKD, which has been argued to be an example of overdiagnosis [15]. While a small real increase in CKD may plausibly be due to the diabetes epidemic, most of the diagnostic trend appears to be due to the introduction of the QOF CKD register in April 2006 and change in diagnostic approach to one largely based on laboratory estimates of glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) evaluated against a standard that does not account for advanced age. NHS clinical guidelines for CKD were changed in 2008 to identify it earlier (by closer review of those at risk of developing CKD and by monitoring decline in eFGR) and to reduce numbers progressing to end-stage renal failure [27]. In the older population, this change aimed to detect CKD associated complications and functional decline [10], although the benefits of the resulting labelling of over a third of the oldest old as having CKD are unclear. One potential issue with our estimates is that the use of the term ‘CKD’ was encouraged by the QOF incentive scheme in 2006–07, which might have merely caused a substitution on diagnostic labels. We therefore undertook further analyses of the prevalence of ‘chronic renal disease’, ‘chronic renal failure’, ‘end-stage renal failure’ and related terms, which showed that the combined prevalence of diagnoses broadly equivalent to CKD before 2005 were very low (<1%). Further research has been advocated to measure the impact of age and gender on outcomes stratified by level of EGFR and the presence or absence of proteinuria [27].

It is tempting to attribute the diagnostic trends solely to the QOF incentive payments to GPs, mostly introduced in 2004 and operationalised by 2006. While this may have contributed, with the exception of CKD, most of the disease-specific trends suggest that diagnostic rates have risen across the decade. There was a reported modest improvement in recorded quality of diabetes care in general practice for patients, but with no obvious change in the upward trend for the diagnosis of diabetes [25]. Conditions outside of the QOF during the study period (including osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and anaemia) also show upward trends in prevalence. Changes to disease definitions can affect prevalence rates by, for example, labelling of disease precursors, changing diagnostic thresholds or using different diagnostic methods [15]. Trends may be due to improved methods of valid diagnosis and treatment [28] for some conditions. Finally, it is likely that a proportion of the diagnostic trends documented are due to changes in GP coding of disease that was previously not recorded or only in the free-text material in their electronic records systems. Formal recording of previously unformalised diagnoses may still represent an important change in practice, especially for the disproportionally affected 85+-year-old groups, as formal diagnosis may lead to medico-legal, re-imbursement related and other responsibilities to treat. Increased coding of disease with no other changes in practice could not explain the increase in prescribing or hospital use, nor the reduction in the prevalence of heart failure, although the relative changes in prevalence for the former measures were higher: i.e. our results for the 85+ group suggest a 71% increase prevalence of multi-morbidity, a 48% increase in the prevalence of receiving ≥3 medications and a 28% increase in the proportion being admitted to hospital across the studied period, The increased prevalence of multiple (recorded) diagnoses also implies that risk and prognostic tools based on earlier multi-morbidity counts may no longer be valid and may need to be re-calibrated.

CPRD has many strengths in terms of population coverage and inclusion of patients in nursing and residential homes. However, analyses are dependent on the quality of the available coded material. Most chronic diagnoses have been found to be well recorded although some were under-recorded, such as musculoskeletal conditions and diabetes [29]. Also, we were unable to quantify functional assessments, including, for example, activity of daily living deficits or degrees of cognitive impairments, as these were very seldom recorded in the coded data. We did not access free-text material from the CPRD records as our analysis was focused on formal coded diagnoses. Free-text records can contain terms reflecting full diagnoses but also provisional or possible diagnoses or symptoms for investigation. GP free text is only accessible through CPRD searching of pre-specified terms (to preserve anonymity). We considered that such searches for all 18 conditions and 5 syndromes could not be accurately undertaken (certainly not at reasonable cost). Our estimates should therefore be seen as conservative and likely to represent some undercounting of the real levels of morbidity.

A major limitation for the oldest old is that much of clinical practice and prescribing has not been experimentally evaluated, and older (especially frail) patients are frequently excluded from trials [30]. Ultimately, it is therefore not easy to say whether the trend towards more medicalisation of the oldest old is likely to have net beneficial or detrimental effects. However, the trends presented will add impetus to questions about the appropriateness of multiple diagnostic labelling and the limited evidence of risks and benefits of multiple disease-specific interventions, especially for those of advanced age and with complex needs. The reported trends are likely to add to the debate about the balance between a medical diagnosis led approach and geriatric approaches aimed at maintaining or improving daily functioning and quality of life and incorporating patients' wishes [31].

Conclusion

Over the last decade, there has been a large-scale increase in medicalisation of the oldest old, in terms of upward trends in recorded diagnoses, chronic prescribing and hospital admission. Trends especially in recorded CKD may raise concerns about overdiagnosis. These findings provide new urgency to question the appropriateness of multiple diagnostic labelling and the limited evidence of risks and benefits of multiple disease-specific interventions, especially for those of advanced age and with complex needs.

Key points.

There were no national data on recent trends in diagnosis in the oldest old (85+ years) or 65–84 year olds.

Using CPRD and HES, we estimated diagnosis, prescribing and hospital admission prevalence trends.

Rises in disease prevalence, prescribing and hospital admission largest in oldest old.

There has been a dramatic increase in the medicalisation of the oldest old.

Trends for CKD raise concerns about overdiagnosis.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Conflicts of interest

A.B. is a former employee of Pfizer.

Funding

This study was supported by Age UK (registered charity number 1128267). The team hold a licence to analyse CPRD data. A.B. was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research. J.A.H.M. is funded by a NIHR Academic Clinical Fellowship Award. W.E.H. was supported by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) for the South West Peninsula. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, Age UK or the Department of Health. Financial sponsors played no role in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data or writing of the study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank our expert advisors especially Professors John Campbell and William Hamilton and Dr Iain Lang of the University of Exeter Medical School, and Dr Nick Steel from the University of East Anglia.

References

- 1.Office for National Statistics. 2012. Population Ageing in the United Kingdom, its Constituent Countries and the European Union.

- 2.Economist Intelligence Unit. London: 2012. A new vision for old age: rethinking health policy for Europe's Ageing Society: a report from the economist intelligence unit. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blunt I, Bardsley BM, Dixon J. Trends in Emergency Admissions in England 2004–2009. The Nuffield Trust; 2010. http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/publications. (31 July 2014, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan RM, Ong M. Rationale and public health implications of changing CHD risk factor definitions. Ann Rev Public Health. 2007;28:321–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mody L, Miller DK, McGloin JM, et al. Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2340–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases. JAMA. 2005;294:716–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connolly A, Gaehl E, Martin H, Morris J, Purandare N. Underdiagnosis of dementia in primary care: variations in the observed prevalence and comparisons to the expected prevalence. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15:978–84. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.596805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holman N, Forouhi N, Goyder E, Wild S. The Association of Public Health Observatories - diabetes prevalence model: estimates of total diabetes prevalence for England, 2010–2030. Diabet Med. 2011;28:575–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banerjee D, Chung S, Wong EC, Wang EJ, Stafford RS, Palaniappan LP. Underdiagnosis of hypertension using electronic health records. Am J Hypertens. 2011;25:97–102. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowling CB, Muntner P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease among older adults: a focus on the oldest old. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:1379–86. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schermer T, Smeele I, Thoonen B, et al. Current clinical guideline definitions of airflow obstruction and COPD overdiagnosis in primary care. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:945–52. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00170307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Draisma G, Etzioni R, Tsodikov A, et al. Lead time and overdiagnosis in prostate-specific antigen screening: Importance of methods and context. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:374–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Couteur DG, Doust J, Creasey H, Brayne C. Political drive to screen for pre-dementia: not evidence based and ignores the harms of diagnosis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5125. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moynihan R, Glassock R, Doust J. Chronic kidney disease controversy: how expanding definitions are unnecessarily labelling many people as diseased. BMJ. 2013;347:f4298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin Roland D. Linking physicians’ pay to the quality of care—a major experiment in the United Kingdom. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1448–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr041294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salisbury C, Johnson L, Purdy S, Valderas JM, Montgomery AA. Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e12. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X548929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380:37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Primary Care Commissioning. The NHS Quality and Outcomes Framework for Primary Care: For earlier QOF Business rules contact http://www.pcc-cic.org.uk/ (Accessed April 2012)

- 20.Collerton J, Davies K, Jagger C, et al. Health and disease in 85 year olds: baseline findings from the Newcastle 85+ cohort study. BMJ. 2009;399:b4904. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews FE, Arthur A, Barnes LE, et al. A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: results of the cognitive function and ageing study I and II. Lancet. 2013;382:1384–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61570-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelfve S, Thorslund M, Lennartsson C. Sampling and non-response bias on health-outcomes in surveys of the oldest old. Eur J Ageing. 2013;10:237–45. doi: 10.1007/s10433-013-0275-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersson M, Guo X, Börjesson-Hanson A, Liebetrau M, Östling S, Skoog I. A population-based study on dementia and stroke in 97 year olds. Age Ageing. 2012;41:529–33. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez C, Jones RW, Rietbrock S. Trends in the prevalence of antipsychotic drug use among patients with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias including those treated with antidementia drugs in the community in the UK: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002080. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kontopantelis E, Reeves D, Valderas JM, Campbell S, Doran T. Recorded quality of primary care for patients with diabetes in England before and after the introduction of a financial incentive scheme: a longitudinal observational study. BMJ Qual Safe. 2013;22:53–64. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brettell R, Soljak M, Cecil E, Cowie MR, Tuppin P, Majeed A. Reducing heart failure admission rates in England 2004–2011 are not related to changes in primary care quality: national observational study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1335–42. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. London: 2008. Chronic Kidney Disease: National Clinical Guideline for Early Identification and Management in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. September. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crimmins EM, Beltrán-Sánchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: Is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66:75–86. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:e128. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheppard J, Singh S, Fletcher K, McManus R, Mant J. Impact of age and sex on primary preventive treatment for cardiovascular disease in the West Midlands, UK: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heath I. Overdiagnosis: when good intentions meet vested interests—an essay by Iona Heath. BMJ. 2013;347:f6361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.