Abstract

Objective

Research examining changes in eating disorder symptoms across adolescence suggests an increase in disordered eating from early to late adolescence. However, relevant studies have largely been cross-sectional in nature and most have not examined the changes in the attitudinal symptoms of eating disorders (e.g., weight concerns). This longitudinal study aimed to address gaps in the available data by examining the developmental trajectories of disordered eating in females from preadolescence into young adulthood.

Method

Participants were 745 same-sex female twins from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Disordered eating was assessed using the Total Score, Body Dissatisfaction subscale, Weight Preoccupation subscale, and a combined Binge Eating and Compensatory Behavior subscale from the Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey assessed at the ages of 11, 14, 18, 21, and 25. Several latent growth models were fit to the data to identify the trajectory that most accurately captures the changes in disordered eating symptoms from 11 to 25 years.

Results

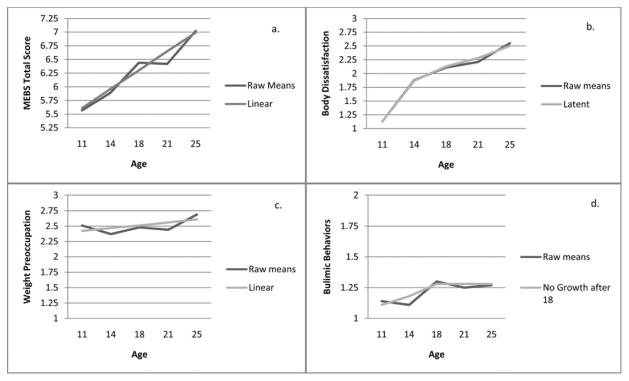

The best-fitting models for overall levels of disordered eating, body dissatisfaction, and weight preoccupation showed an increase in from 11 through 25 years. In contrast, bulimic behaviors increased to age of 18 and then stabilized to age of 25.

Discussion

The findings expanded upon extant research by investigating longitudinal, symptom specific, within-person changes and showing an increase in cognitive symptoms into young adulthood and the stability of disordered eating behaviors past late adolescence.

Keywords: disordered eating, longitudinal, developmental, growth curve

Introduction

The age of onset for anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) is typically during adolescence, with increased risk occurring from middle adolescence into young adulthood.1,2 Disordered eating symptoms (e.g., weight preoccupation, body dissatisfaction, and binge eating) also typically follow an increasing trajectory with peak periods of risk occurring around mid-to-late adolescence.3 As disordered eating frequently precedes the development of a clinical eating disorder,4 it is helpful to understand the developmental trajectory of these symptoms and behaviors.

Cross-sectional studies have shown increases in disordered eating from early to late adolescence (e.g., Refs. 3,5,6). There have been fewer longitudinal studies during this time period, but the results have generally confirmed the presence of increases in bulimic behaviors, restraint, and weight concerns from early-mid adolescence into late adolescence. For example, Calam and Waller7 found increases in bulimic symptoms (i.e., bingeing and purging) and dietary restriction in girls from 12 to 19 years, Field et al.8 reported a rise in binge eating from 12 to 14 years, and Attie and Brooks-Gunn9 found increases in mean levels of disordered eating (i.e., dietary restraint, bulimic behaviors, and preoccupation with thinness) in girls from 14 to 16 years.

The findings from longitudinal studies examining the transition from late adolescence into young adulthood have been much less consistent. Lewinsohn et al.10 found increases in the lifetime prevalence of partial and full-threshold DSM-IV AN and BN from 18 to 19 and again to 23 years, but slight decreases in the point prevalence of these disorders from 19 to 23 years. Furthermore, the authors reported that the first incidence of AN and BN was greater before the age of 18 than it was between 19 and 23. Similarly, Graber et al.11 showed an increase in mean-disordered eating levels (measured using the EAT-26 total score) from age of 16 into young adulthood at age of 22, although changes were modest. In contrast, Steinhausen et al.12 found an increase in the percentage of females reporting one or more abnormal eating behaviors (e.g., binge eating and vomiting) across adolescence from 15 to 16 years, but no change in this percentage from age of 16 to young adulthood at age of 19. A recent study also observed significant increases in the prevalence of binge eating from 15 to 17 years (2.4–5.4%), but relative stability from 17 to 19 years (5.4–5.7%).13

It is worth noting that the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS14) is the only study that has followed girls from preadolescence (age, 9 years) into young adulthood (age, 26 years). Data from the GUTS showed increases in body dissatisfaction and weight and shape concerns from 9 to 18 years,15 and increases in binge eating from 9 to 24 years although increases in binge eating were somewhat more variable (decreases from 16 to 17 years, stability from 17 to 18 years, and decreases again from 22 to 23 years) than those observed for other symptoms.16 In contrast, and similar to the findings of Lewinsohn et al.,10 Field et al.17 reported an increase in eating disorder diagnoses (i.e., BN, binge eating disorder, purging disorder, and eating disorder not otherwise specified) in the GUTS cohorts from 9 to 22 years, but a decrease in prevalence from 23 to 26 years.

In sum, the existing literature examining the changes in disordered eating across adolescence suggests that there are increases in these behaviors from early adolescence into late adolescence.7–9 However, the findings are mixed as to whether disordered eating increases or remains stable from adolescence into young adulthood.10–13 Given the small number of longitudinal studies conducted in the older age groups, more research is needed to clarify the degree of stability or change during the late-adolescent–young adulthood transition. In addition, because GUTS is the only project to follow patients across the entire period of risk (i.e., preadolescence through young adulthood), we have very limited data on the changes in disordered eating symptoms in the same cohort of patients across the most vulnerable periods. Consequently, somewhat inconsistent findings (particularly regarding transitions from adolescence into young adulthood) could be owing to study the differences in the age groups assessed, cohort differences, study differences in assessments, and/or a combination of these factors. Additionally, most studies examined only the overall levels of disordered eating or disordered eating behaviors although the cognitive symptoms of eating disorders (e.g., body dissatisfaction and weight concerns) are some of the strongest prospective predictors of the eventual development of an eating disorder.4,18–20 A longitudinal study that follows a single sample of participants through peak periods of risk using assessments of overall pathology as well as bulimic behaviors and cognitive symptoms is needed to provide corroborative data regarding changes versus stability in key types of disordered eating across development and time. Understanding when various eating disorder symptoms come online and increase (or decrease) is critical for identifying developmentally specific process (e.g., transition to college) that may contribute to different types of symptoms and different eating disorders.

Given the above data, this longitudinal study aimed to examine the developmental trajectories of a range of disordered eating symptoms in single sample of females assessed at the ages of 11, 14, 18, 21, and 25. We used a global measure of disordered eating to tap the overall levels of risk for a range of eating pathology across these critical risk periods. However, we also examined cognitive concerns, such as weight preoccupation and body dissatisfaction as well as bulimic behaviors, so that we could examine growth in these key symptoms as well. We modeled the developmental changes in disordered eating symptoms using latent growth curve models that allowed us to test the full range of developmental trajectories in our sample.

Method

Participants

Participants included 745 same-sex female twins from the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS). The MTFS is a population-based, longitudinal study of reared-together female and male twins and their parents. Public databases were used to obtain the birth records used to identify twins born in the state of Minnesota. Notably, more than 90% of twins born between 1971 and 1985 were located. A detailed description of study recruitment and assessments can be found elsewhere.21 This study included data from a female cohort that began assessments at approximately 11 years old (M = 11.7, SD = 0.46). Participants completed follow-up assessments at ages of 14 (M = 14.8, SD = 0.56), 18 (M = 18.3, SD = 0.71), 21 (M = 21.0, SD = 0.62), and 25 (M = 25.1, SD = 0.66).

Disordered Eating

Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey

The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey (MEBS)22a is a 30-item true/false self-report questionnaire that assesses disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. The Total Score on the MEBS is an overall measure of disordered eating composed of the following four subscales: Body Dissatisfaction (i.e., dissatisfaction with one’s size or shape), Weight Preoccupation (i.e., preoccupation with dieting, thinness, and weight), Binge Eating (i.e., thoughts about overeating or the tendency to binge eat), and Compensatory Behavior (i.e., the use of compensatory behaviors such as self-induced vomiting or diuretics for weight loss).

Importantly, the MEBS was adapted from the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI) and modifications were made to the original EDI to tailor it for use with preadolescent children: (a) selecting a subset of EDI items to create a shorter measure, with an emphasis placed on items assessing eating attitudes and behaviors rather than personality traits; (b) simplifying the language of items to increase comprehensibility to girls as young as 9 years old; and (c) altering the scoring convention to true–false to simplify administration and interpretation. In the current samples, the internal consistency of the MEBS Total Score for the 11-, 14-, 18-, and 21-year-old girls ranges from .86 to .89.22 The internal consistency was also high for six-item Body Dissatisfaction (.83–.87) and eight-item Weight Preoccupation (.78–.85); however, similar to some previous research,23 internal consistency was much lower for seven-item Binge Eating and six-item Compensatory Behavior (.40–.72), particularly in the younger patients (.40–.66). Thus, the Binge Eating and Compensatory Behavior subscales were combined to form a “bulimic behavior” that showed more acceptable alphas ranging from .64 to .73 in the present sample. The MEBS Total Score and subscales, particularly Weight Preoccupation, Binge Eating, and Compensatory Behavior, demonstrated sufficient discriminant validity through its ability to differentiate between normal control participants and individuals with eating disorders.22 Concurrent validity has also been established through significant correlations (r >.78) between the MEBS Total Score and the Total Score from the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDEQ), as well as correlations between the Body Dissatisfaction and the Weight Preoccupation subscales and corresponding subscales from the EDEQ (i.e., the Shape and Weight Concerns scales [rs >.68]22).

Body Mass Index

Body mass index (BMI: weight [kg]/height2 [m]) was calculated using height and weight. Height was measured with an anthropometer, and weight was measured on a level platform scale with a beam and moveable weights.

Statistical Analyses

Growth curve models were fit to the data using raw data maximum-likelihood estimation with Mplus computer software.24 Several hypothetical growth functions, based on suggested trajectories from extant research (Introduction) were estimated: no growth (i.e., a model assuming that the trajectory of change across all ages is a straight line), latent basis growth (i.e., an unrestricted model that allows for any form of change), linear growth (i.e., a model for which growth is characterized as a straight line with a constant rate of change across all ages), quadratic (i.e., a model that allows for a curved trajectory with one bend), no growth after age of 14 (i.e., a model that allows for increases or decreases up to age of 14 and then no significant changes), no growth after age of 18 (i.e., a model that allows for increases or decreases up to age of 17 and then no significant changes), and no growth after age of 21 (i.e., a model that allows for increases or decreases up to age 21 and then no significant changes). The overall fit of these models was then compared using several indices, including the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC),25 the Comparative Fit Index (CFI),26 and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).27 Lower BIC and higher CFI (i.e., values>.95) indicate better fitting models. The RMSEA is the preferred fit index in large samples,28 where RMSEA values of .06 or smaller are indicative of good model fit, and RMSEA values >.10 are indicative of poorer model fit.27

Missing data were imputed using full information maximum likelihood (FIML).24 FIML is the default method for estimating missing data in Mplus, and it works by estimating a likelihood function for each participant based on all available data at other time points.24 The sample include 745 twins with data from at least two time points between ages of 11 and 25. Valid data at each time point were as follows: 503 (68%) participants at all five time points, 154 (21%) at four time points, 54 (7%) at three time points, and 34 (5%) at two time points. As is typical of longitudinal research,29 the highest percentage of missing data was found at the older follow-up ages (i.e., 14% [108/745] at age of 18 and 11% [83/745] at age of 25) as compared to the younger ages (i.e., 7% [54/745] at age of 11, 8% [59/745] at age of 14).

Owing to the nonindependence of twin data, analyses were also run after randomly selecting one twin from each pair (n = 372). Importantly, the results for the MEBS Total Scale as well as each subscale were identical to the results reported herein (data not shown), and therefore, only the results from the full twin sample are reported.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Raw means and standard deviations of the MEBS Total Score and subscales at each time point (i.e., 11, 14, 18, 21, and 25 years) are listed in Table 1. Total Score raw mean levels increased from 11 to 18 years, then stabilized somewhat from 18 and 21 years before increasing again at age of 25. Body Dissatisfaction exhibited a similar trajectory although it showed more steady increases across each time point. Weight Preoccupation showed an increase in scores when comparing the 11- and 25-year assessments although the trajectory of change varied in the intermediate ages with some increases and some decreases across time (despite an overall net increase across all ages). Finally, the combined Binge Eating and Compensatory Behavior (i.e., bulimic behavior) scale exhibited a different pattern of change, with increases in scores from age of 11 through 18, but then apparent stability from age of 18 to 25. Overall, the findings suggest that the latent growth curve models will likely find similar increases in symptoms for the total score and cognitive symptoms of eating disorders across ages, but an intermixed pattern of increases and then stability will likely be found for bulimic behaviors.

TABLE 1.

Mean (and standard deviation) of BMI and raw (and standard deviation), estimated means, and model fit statistics for MEBS Total Score and Subscales

| BMI | Raw Mean (SD) | Latent | No Growth | Linear | Quadratic | No Growth After Age of 14 | No Growth After Age of 18 | No Growth After Age of 21 | Growth Until 18 and After 21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEBS Total Score | ||||||||||

| 11 Years | 19.41 (3.76) | 5.57 (4.82) | 5.61 | 6.28 | 5.61 | 5.93 | 5.58 | 5.60 | 5.62 | 5.52 |

| 14 Years | 22.21 (4.21) | 5.89 (5.68) | 5.86 | 6.28 | 5.96 | 5.93 | 6.48 | 5.90 | 5.88 | 6.01 |

| 18 Years | 23.78 (4.92) | 6.44 (5.60) | 6.51 | 6.28 | 6.30 | 6.06 | 6.48 | 6.68 | 6.53 | 6.50 |

| 21 Years | 24.53 (5.25) | 6.42 (5.68) | 6.68 | 6.28 | 6.65 | 6.44 | 6.48 | 6.68 | 6.75 | 6.50 |

| 25 Years | 25.68 (6.02) | 7.02 (5.58) | 6.87 | 6.28 | 6.99 | 7.08 | 6.48 | 6.68 | 6.75 | 7.00 |

| Fit statistics | ||||||||||

| BIC | — | — | 19,725.00 | 19,847.71 | 19,719.60 | 19,775.01 | 19,781.10 | 19,723.65 | 19,722.60 | 19,723.94 |

| CFI | — | — | .94 | .83 | .93 | .89 | .89 | .94 | .94 | .94 |

| RMSEA | — | — | .10 | .14 | .09 | .12 | .12 | .10 | .10 | .10 |

| RMSEA CI.90 | — | — | .08, .12 | .12, .15 | .08, .11 | .10, .14 | .10, .14 | .08, .11 | .08, .11 | .08, .11 |

| Body dissatisfaction | ||||||||||

| 11 Years | — | 1.13 (1.67) | 1.13 | 1.97 | 1.34 | 1.67 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.25 |

| 14 Years | — | 1.88 (2.09) | 1.87 | 1.97 | 1.66 | 1.67 | 2.19 | 1.90 | 1.88 | 1.71 |

| 18 Years | — | 2.11 (2.13) | 2.13 | 1.97 | 1.98 | 1.78 | 2.19 | 2.29 | 2.14 | 2.17 |

| 21 Years | — | 2.21 (2.17) | 2.28 | 1.97 | 2.30 | 2.10 | 2.19 | 2.29 | 2.38 | 2.17 |

| 25 Years | — | 2.55 (2.19) | 2.50 | 1.97 | 2.62 | 2.64 | 2.19 | 2.29 | 2.38 | 2.62 |

| Fit statistics | ||||||||||

| BIC | — | — | 13,276.27 | 13,661.83 | 13,303.49 | 13,448.96 | 13,319.64 | 13,288.85 | 13,280.13 | 13,284.61 |

| CFI | — | — | .93 | .58 | .89 | .77 | .88 | .91 | .92 | .91 |

| RMSEA | — | — | .11 | .20 | .11 | .16 | .12 | .11 | .11 | .11 |

| RMSEA CI.90 | — | — | .09, .12 | .19, .22 | .10, .13 | .15, .18 | .10, .14 | .09, .13 | .09, .12 | .09, .12 |

| Weight preoccupation | ||||||||||

| 11 Years | — | 2.51 (2.56) | 2.43 | 2.51 | 2.42 | 2.44 | 2.51 | 2.45 | 2.44 | 2.41 |

| 14 Years | — | 2.37 (2.46) | 2.46 | 2.51 | 2.47 | 2.44 | 2.51 | 2.48 | 2.46 | 2.48 |

| 18 Years | — | 2.48 (2.36) | 2.54 | 2.51 | 2.51 | 2.46 | 2.51 | 2.55 | 2.54 | 2.54 |

| 21 Years | — | 2.44 (2.33) | 2.56 | 2.51 | 2.56 | 2.54 | 2.51 | 2.55 | 2.56 | 2.54 |

| 25 Years | — | 2.69 (2.29) | 2.57 | 2.51 | 2.61 | 2.67 | 2.51 | 2.55 | 2.56 | 2.60 |

| Fit statistics | ||||||||||

| BIC | — | 14,297.61 | 14,320.46 | 14,288.75 | 14,311.10 | 14,313.94 | 14,288.93 | 14,291.55 | 14,291.84 | |

| CFI | — | .96 | .90 | .95 | .93 | .93 | .95 | .96 | .95 | |

| RMSEA | — | — | .08 | .09 | .07 | .09 | .09 | .07 | .07 | .07 |

| RMSEA CI.90 | — | — | .06, .09 | .08, .11 | .06, .09 | .07, .10 | .07, .10 | .05, .09 | .05, .09 | .06, .09 |

| Binge eating and compensatory behaviors (bulimic behaviors) | ||||||||||

| 11 Years | — | 1.14 (1.51) | 1.12 | 1.22 | 1.15 | 1.19 | 1.14 | 1.11 | 1.12 | 1.13 |

| 14 Years | — | 1.11 (1.66) | 1.18 | 1.22 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.25 | 1.18 | 1.18 | 1.19 |

| 18 Years | — | 1.30 (1.71) | 1.26 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.20 | 1.25 | 1.28 | 1.26 | 1.25 |

| 21 Years | — | 1.25 (1.74) | 1.28 | 1.22 | 1.26 | 1.23 | 1.25 | 1.28 | 1.29 | 1.25 |

| 25 Years | — | 1.27 (1.76) | 1.29 | 1.22 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 1.25 | 1.28 | 1.29 | 1.31 |

| Fit statistics | ||||||||||

| BIC | — | — | 12,539.65 | 12,639.71 | 12,541.03 | 12,605.88 | 12,576.80 | 12,530.15 | 12,533.54 | 12,541.15 |

| CFI | — | — | .92 | .71 | .89 | .79 | .83 | .92 | .92 | .89 |

| RMSEA | — | — | .08 | .12 | .08 | .11 | .10 | .07 | .08 | .08 |

| RMSEA CI.90 | — | — | .06, .10 | .11, .14 | .07, .10 | .10, .13 | .08, .12 | .06, .09 | .06, .09 | .07, .10 |

Note: MEBS, Minnesota Eating Behavior Inventory; SD, standard deviation; BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CI90 = 90% confidence interval; latent growth, an unrestricted model that allows for any form of change; no growth, no changes across age; linear growth, constant rate of change across all ages; quadratic, a curved trajectory of change with one bend; no growth after age of 14, increases or decreases up to age of 14 and then no change; no growth after age of 18, increases or decreases up to age of 18 and then no change; no growth after age of 21, increases or decreases up to age of 21 and then no change; growth until age of 18 and after 21 years (i.e., a model that allows for increases or decreases until age of 18, stability through age of 21, and increases or decreases until age of 25). The best-fitting model is indicated by bold font.

Not surprisingly, mean BMI significantly increased at each time point (Table 1). The largest increase was from 11 to 14 years of nearly 3 kg/m2. Increases between the other time points were all close to 1 kg/m2.

Growth Curve Analysis

Latent growth curve models confirmed impressions. Estimated means for each growth curve model by MEBS scale are listed in Table 1. In terms of the Total Score, the estimated means from the latent, linear, and “no growth after age 21” models seemed to best approximate the raw data means for the MEBS Total Score. Specifically, fit statistics for the no growth, quadratic growth, and “no growth after age of 14” models indicated poor fits to the data, as shown by: (1) higher BIC values, (2) low CFI values, and (3) higher RMSEA values. In contrast, the latent, linear, “no growth after age of 18,” and “no growth after age 21” models provided improved fits to the data as indicated by the lower BIC values, higher CFIs, and lower RMSEAs for these models. When comparing these four models against each other, the linear model appeared to provide the best fit as this model had the lowest BIC and RMSEA value. The linear model also had a high CFI, although notably, the value of the CFI for the latent, “no growth after 18,” and “no growth after age of 21” models was almost equal to the CFI for the linear model. Nonetheless, the linear model was selected as the best-fitting model (Fig. 1) as the BIC is the preferred “standalone” measure of fit for models that are not nested.30

Figure 1.

Raw means and estimated means for the best-fitting models. (a) MEBS Total Score raw means and estimated means for the linear model allowing for a constant rate of change across all ages. (b) Body Dissatisfaction raw means and estimated means for the latent model, which is an unrestricted model allowing for any form of change across age. (c) Weight Preoccupation raw means and estimated means for the linear model allowing for a constant rate of change across all ages. (d) Bulimic Behaviors raw means and estimated means for the no growth after age of 18 model allowing for changes up to age of 18 and then no change from 18 to 25 years.

Nonetheless, there was some hint in the raw means for the MEBS Total Score that a model that allowed scores to increase to age of 18, and then level off at age of 21 before increasing to age of 25 might fit the data better. Thus, we fit an additional, post hoc model (the “growth until 18 and after 21” model, Table 1) that tested this model of change. Although the estimated means from the “growth until 18 and after 21” model more closely resembled the raw means, the fit statistics indicate that this model provided a poorer fit to the data, with a larger BIC as compared to the linear model (Table 1). Taken together then, the findings suggest that there is a linear increase in the levels of disordered eating from early adolescence to young adulthood for overall levels of disordered eating.

The findings for Body Dissatisfaction and Weight Preoccupation also showed increases in scores across time although the best fitting model varied somewhat by scale. The latent model provided the best fit to the data for Body Dissatisfaction as indicated by the lowest BIC, highest CFI, and a lower RMSEA. The latent model is the completely “unconstrained” model that allows the values to vary unrestricted across time. As shown in Figure 1, the estimated means from this model showed steady increases in Body Dissatisfaction scores from 11 to 25 years.

In contrast, the linear model provided the best fit to the data for Weight Preoccupation scores as indicated by the lowest BIC, a higher CFI, and a lower RMSEA. The estimated means (Fig. 1) showed increases in scores on Weight Preoccupation from 11 to 25 years although increases were more modest than those observed for the Total Score and Body Dissatisfaction. It was somewhat surprising to find that the linear model provided the best to the Weight Preoccupation scores, given the somewhat inconsistent increases/decreases in scores across time (Table 1 and Fig. 1). In addition, in some ways, it was expected that the “no growth” model would provide the best fit to these data, given the more modest changes in scores across time. However, as noted above, there was an increase in Weight Preoccupation scores when comparing the 11- to the 25-year assessments, and the model likely picked up on these more substantial increases across the initial and final ages. The fact that the linear model provided a better fit to the data than the “no growth” model further suggests that increases across the full time period (age, 11–25 years) were statistically significant as the “no growth” model has the lowest degrees of freedom and would therefore be preferred if the changes were not statistically significant. Overall then, the results suggest that there are significant increases in Weight Preoccupation scores across time, even if the overall level of change is more modest than that observed for other disordered eating symptoms.

Finally, as expected from the raw means, the “no growth after age of 18” provided the best fit to the data for the combined Binge Eating and Compensatory Behavior Scale as indicated by the lowest BIC and RMSEA, and a higher CFI (Table 1). Estimated means closely followed the raw means and showed increases in bulimic behaviors from age of 11 through 18, and then stability in these scores from 18 to 25 years.

Discussion

This study explored the developmental trajectories of a range of disordered eating symptoms in a large sample of females followed longitudinally from ages of 11 through 25. The findings revealed differential patterns of change across the different types of eating disorders symptoms. Although significant increases were observed in overall levels of disordered eating and cognitive symptoms across ages of 11 to 25, increases in bulimic behaviors were limited to adolescence as scores on the combined Binge Eating and Compensatory Behavior subscale leveled off and became stable from 18 to 25 years. Overall, the results are significant in highlighting variability in within-person changes in the different types of disordered eating symptoms that might have implications for etiological models and prevention efforts.

Our results replicate those from GUTS and extend previous longitudinal studies in adolescence (e.g., see Refs. 7–9,11) showing significant increases in several types of disordered eating symptoms across the adolescent period. The findings highlight adolescence as the most significant risk period for the onset of eating pathology. The fact that all types of disordered eating increased from 11 to 18 years suggests that prevention and intervention efforts would do well to focus on the adolescent time period as a period of particularly high risk for the development of clinical eating disorders. Although clinical eating disorders often persist into adulthood, our data show that the symptoms themselves (including the cognitive and behavioral symptoms) often develop and have their first onset during adolescence. This pattern of increasing adolescent risk for all symptoms may at least partially explain the reason why the highest incidence and point prevalence of partial and full syndrome AN and BN is before age of 18 (see Ref. 10). Targeting symptoms of these disorders in early adolescence may therefore help stave off later increases in disordered eating and the development of full-blown eating disorders, particularly as some of the symptoms we examined (e.g., body dissatisfaction) have been shown to intensify the effects of other risk factors for eating disorders, including levels of negative affect (e.g., Ref. 18).

Notably, when examined separately, disordered eating symptoms showed differential trajectories of change beyond the adolescent time period. Although overall disordered eating levels, body dissatisfaction, and weight preoccupation continued to increase from 18 to 25 years, bulimic behaviors showed stability across this adolescent to young adulthood transition. These findings suggest that the continued increase in overall disordered eating scores from late adolescence to young adulthood may be primarily driven by the changes in cognitive concerns about weight and body image, rather than disordered eating behaviors, such as binge eating.

Interestingly, steady increases in the cognitive symptoms corresponded with an increasing BMI of approximately 1 kg/m2 every 3 years from age of 11 (BMI mean = 19.41 [SD = 3.76]) to age of 25 (BMI mean = 25.68 [SD = 6.02]). Importantly, this increase corroborates the previous findings from the GUTS cohorts13,31 and data showing that women in young adulthood gain weight at higher rates than females in other age groups.32 This rise in BMI might be one reason why concerns about body weight/shape continue to increase into young adulthood, whereas other symptoms (e.g., binge eating and purging) that may be less directly predicted by increases in BMI remain stable. Interestingly, the cognitive body weight/shape symptoms also tend to persist after partial and full recovery from eating disorders,33 suggesting that their expression, once established, is rather intractable. Taken together then, our data and those of others15 clearly highlight the need for a sustained prevention and treatment focus on the cognitive symptoms of eating disorders across the development to decrease symptom expression and maintenance across time. Importantly, eating disorder prevention programs have been developed with a focus on decreasing symptoms such as body dissatisfaction and weight preoccupation. These programs have helped to decrease eating disorder symptoms in adolescents and college-aged women34,35; however, they have not focused on preadolescence or young adulthood beyond the college years (see review by Stice et al.34). Our findings support the importance of these prevention programs and also highlight the need to establish programs in preadolescence when eating disorder behaviors are first emerging. Additionally, our results suggest that prevention efforts should be applied across development, into the postcollege age, to address the increasing body image concerns.

As noted briefly above, there was a lack of change in bulimic behaviors after age of 18. Two previous studies examined these behaviors across the adolescent/young adult transition, and both also found that the rates of bulimic behaviors remained stable from adolescence into young adulthood.12,13 Our study extended these findings by showing that stability of expression extends through the entire peak period of risk for eating disorders (i.e., through age of 25). Similar to the findings for cognitive symptoms, our results have implications for prevention and intervention efforts; most importantly, interventions should focus on the adolescent period as a sustained focus here could potentially stave off peak periods of symptom expression for the behaviors. Applying such strategies later in the trajectory, after bulimic behaviors have stabilized in young adulthood, might be much less beneficial for preventing the onset of these symptoms and BN. Indeed, in aggregate, our data suggest that adolescence (and possibly preadolescence) should continue to be a heavy focus of prevention programs for all eating disorders symptoms even if continued prevention efforts are needed into young adulthood for specific types of eating disorder symptoms (e.g., the cognitive symptoms).

Despite the many strengths of this study (e.g., longitudinal design and assessment across multiple periods of risk), there were some limitations that should be noted as well. First, the sample size may have prohibited the detection of subtle differences in some scores (e.g., MEBS Total Score possible stability from 18 to 21 years). Thus, the results need to be replicated in a larger sample. Nonetheless, the findings provided initial evidence for the trajectory of overall levels of disordered eating as well as changes in cognitive symptoms and bulimic behaviors across several key developmental periods.

Second, our assessments were completed every 3 years instead of annually. Although the ages assessed covered many of the major developmental transitions from preadolescence to adulthood, we still missed critical “events” (e.g., pubertal development; transition to college) that could impact developmental trajectories of risk. Future studies should attempt to conduct more frequent assessments across these critical time periods.

Third, we did not examine all types of disordered eating. Most notably, dietary restraint was not included in the present investigation. The previous research is limited, but findings thus far have shown increases in dietary restraint during adolescence7 and relative stability of restraint and dieting behaviors from late adolescence into young adulthood.35 This pattern of results follows that observed for bulimic behaviors, but additional research is needed to confirm these impressions.

Finally, our study only examined the trajectories of disordered eating from preadolescence into young adulthood and cannot speak to developmental changes before or after these age periods. The studies in childhood have suggested the stability of low levels of disordered eating prior to puberty (Ref. 36). The studies examining the transition from young-to-middle adulthood have been mixed, with some showing decreases in disordered eating levels,37,38 some showing stability,39,40 and another reporting increases in some symptoms (e.g., EDI hunger) and decreases in others (e.g., binge eating41). These studies collectively suggest that we have captured the main period of growth in disordered eating levels (i.e., adolescence) and that other developmental periods likely show either decreases or stability in risk. Additional research is needed to confirm these impressions and to develop a more comprehensive model of developmental changes in disordered eating across the lifespan.

Acknowledgments

Supported by R01 AA009367 from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

This material is the result of work supported, in part, with resources and the use of facilities at the VISN 4 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System.

Footnotes

The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey (MEBS; previously known as the Minnesota Eating Disorder Inventory [M-EDI]) was adapted and reproduced by special permission of Psychological Assessment Resources, 16204 North Florida Avenue, Lutz, Florida 33549, from the Eating Disorder Inventory (collectively, EDI and EDI-2) by Garner, Olmstead, Polivy, Copyright 1983 by Psychological Assessment Resources. Further reproduction of the MEBS is prohibited without prior permission from Psychological Assessment Resources.

Data for this project were collected at the University of Minnesota. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

No conflict of interest exists for any of the authors.

The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones JM, Bennett S, Olmsted MP, Lawson ML, Rodin G. Disordered eating attitudes and behaviours in teenaged girls: A school-based study. Can Med Assoc J. 2001;165:547–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer H, Agras WS. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application for risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:19–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: Relationship to gender and ethnicity. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:166–175. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood A, Waller G, Miller J, Slade P. The development of Eating Attitude Test scores in adolescence. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;11:279–282. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calam R, Waller G. Are eating and psychosocial characteristics in early teenage years useful predictors of eating characteristics in early adulthood? A 7-year longitudinal study. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;24:351–362. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199812)24:4<351::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, Malspeis S, Rosner B, Rockett HR, et al. Relation between dieting and weight changes among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112:900–906. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attie I, Brooks-Gunn J. Development of eating problems in adolescent girls: A longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 1989;25:70–79. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewinsohn PM, Striegel-Moore RH, Seeley JR. Epidemiology and natural course of eating disorders in young women from adolescence to young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 2000;39:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Paikoff RL, Warren MP. Prediction of eating problems: An 8-year study of adolescent girls. Dev Psychol. 1994;30:823–834. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinhausen H, Gavez S, Metzke CW. Psychosocial correlates, outcome, and stability of abnormal adolescent eating behavior in community samples of young people. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:119–126. doi: 10.1002/eat.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skinner HH, Haines J, Austin SB, Field AE. A prospective study of overeating, binge eating, and depressive symptoms among adolescent and young adult women. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:478–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Field AE, Camargo CA, Taylor CB, Berkey CS, Roberts SB, Colditz GA. Peer, parent, and media influences on the development of weight concerns and frequent dieting among preadolescent and adolescent girls and boys. Pediatrics. 2001;107:54–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calzo JP, Sonneville KR, Haines J, Blood EA, Field AE, Austin SB. The development of associations among BMI, body dissatisfaction and weight and shape concern in adolescent boys and girls. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonneville KR, Horton NJ, Micali N, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Solmi F, et al. Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: Does loss of control matter? Pediatrics. 2013;167:149–155. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Field AE, Sonneville KR, Micali N, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Laird NM, et al. Prospective association of common eating disorders and adverse outcomes. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e289–e295. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2002;128:825–848. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Striegel-Moore RH, Bulik CM. Risk factors for eating disorders. Am Psychol. 2007;62:181–198. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The McKnight Investigators. Risk factors for the onset of eating disorders in adolescent girls: Results of the McKnight Longitudinal Risk Factor Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:248–254. doi: 10.1176/ajp.160.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: Findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Ranson KM, Klump KL, Iacono WG, McGue M. The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey: A brief measure of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Eat Behav. 2005;6:373–392. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Age differences in genetic and environmental influences on eating attitudes and behaviors in preadolescent and adolescent female twins. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:239–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1988;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen F, Curran PJ, Bollen KA, Kirby J, Paxton P. An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociol Method Res. 2008;36:462–494. doi: 10.1177/0049124108314720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Twisk J, de Vente W. Attrition in longitudinal studies: How to deal with missing data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:329–337. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curran PJ, Obeidat K, Losardo D. Twelve frequently asked questions about growth curve modeling. J Cogn Dev. 2010;11:121–136. doi: 10.1080/15248371003699969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Field AE, Haines J, Rosner B, Willett WC. Weight-control behaviors and subsequent weight change among adolescents and young adult females. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:147–153. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wane S, van Uffelen JG, Brown W. Determinants of weight gain in young women: A review of the literature. J Womens Health. 2010;19:1327–1340. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bardone-Cone AM, Harney MB, Maldonado CR, Lawson MA, Robinson DP, Smith R, et al. Defining recovery from an eating disorder: Conceptualization, validation, and examination of psychosocial functioning and psychiatric comorbidity. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stice E, Becker CB, Yokum S. Eating disorder prevention: Current Evidence base and future directions. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:478–485. doi: 10.1002/eat.22105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stice E, Rohde P, Shaw H, Marti CN. Efficacy trial of a selective prevention program targeting both eating disorders and obesity among female college students: 1- and 2-Year follow-up effects. J Consult Clin Psych. 2013;81:183–189. doi: 10.1037/a0031235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vohs KD, Heatherton TF, Herrin M. Disordered eating and the transition to college: A prospective study. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;29:280–288. doi: 10.1002/eat.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keel PK, Fulkerson JA, Leon GR. Disordered eating precursors in pre-and early adolescent girls and boys. J Youth Adolesc. 1997;26:203–216. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heatherton TF, Mahamedi F, Striepe M, Field AE, Keel PK. A 10-year longitudinal study of body weight, dieting, and eating disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keel PK, Baxter MG, Heatherton TF, Joiner TE., Jr A 20-year longitudinal study of body weight, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:422–432. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dolan B, Evans C, Lacey JH. The natural history of disordered eating behavior and attitudes in adult women. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;12:241–248. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joiner TE, Jr, Heatherton TF, Keel P. Ten-year stability and predictive validity of five bulimia-related indicators. Am J Psychiat. 1997;154:1133–1138. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rizvi SL, Stice E, Agras WS. Natural history of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors over a 6-year period. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;26:406–413. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199912)26:4<406::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]