Abstract

Background

Body weight–supported treadmill training (BWSTT) has produced mixed results compared with other therapeutic techniques.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine whether an intensive intervention (intensive mobility training) including BWSTT provides superior gait, balance, and mobility outcomes compared with a similar intervention with overground gait training in place of BWSTT.

Methods

Forty-three individuals with chronic stroke (mean [SD] age, 61.5 [13.5] years; mean [SD] time since stroke, 3.3 [3.8] years), were randomized to a treatment (BWSTT, n = 23) or control (overground gait training, n = 20) group. Treatment consisted of 1 hour of gait training; 1 hour of balance activities; and 1 hour of strength, range of motion, and coordination for 10 consecutive weekdays (30 hours). Assessments (step length differential, self-selected and fast walking speed, 6-minute walk test, Berg Balance Scale [BBS], Dynamic Gait Index [DGI], Activities-specific Balance Confidence [ABC] scale, single limb stance, Timed Up and Go [TUG], Fugl-Meyer [FM], and perceived recovery [PR]) were conducted before, immediately after, and 3 months after intervention.

Results

No significant differences (α = 0.05) were found between groups after training or at follow-up; therefore, groups were combined for remaining analyses. Significant differences (α = 0.05) were found pretest to posttest for fast walking speed, BBS, DGI, ABC, TUG, FM, and PR. DGI, ABC, TUG, and PR results remained significant at follow-up. Effect sizes were small to moderate in the direction of improvement.

Conclusions

Future studies should investigate the effectiveness of intensive interventions of durations greater than 10 days for improving gait, balance, and mobility in individuals with chronic stroke.

Keywords: balance, gait, mobility, rehabilitation, stroke, treadmill training

Determining the most appropriate method to address mobility limitations in individuals with chronic stroke can be a challenging task for clinicians. As the rehabilitation field continues to move in an evidence-based practice direction, the importance of identifying effective, feasible intervention strategies increases. The literature must provide clinicians with replicated results to support the adoption or rejection of a specific treatment option. In the case of inconsistent findings, additional information is required so that the preponderance of evidence to support an approach can be used to determine its clinical worth. Body weight–supported treadmill training (BWSTT) for individuals with chronic stroke falls into this category.

Previous studies investigating BWSTT as a component of intervention options for individuals with stroke have produced mixed results.1–7 Studies have also varied widely in treadmill training dosage.1–7 A Cochrane review that included treadmill training with and without body weight support concluded that more research was needed.8 Since publication of the meta-analysis, 2 large randomized controlled trials have been conducted to examine the effectiveness of BWSTT for individuals with stroke: the Strength Training Effectiveness Post-Stroke (STEPS) (n = 80)9 and the Locomotor Experience Applied Post Stroke (LEAPS) (n = 408)10 trials. Participants in the STEPS trial received 1 hour of therapy, 4 days a week, for 6 weeks. BWSTT was provided every other session (2 times a week) for 20 minutes per session. Results from the STEPS trial demonstrated that BWSTT improves walking speed more effectively than resisted cycling in ambulatory individuals with stroke.9 The LEAPS trial provided a longer total intervention time, up to 90 minutes per session, and a longer intervention period, 12 to 16 weeks, but sessions were less frequent (3 times a week). For those randomized to the locomotor training group, BWSTT accounted for 20 to 30 minutes of each treatment session. This large randomized controlled trial did not provide evidence that BWSTT is more effective than a home-based physical therapy program focused on strength and balance at improving walking speed, balance, or functional status.10

In addition to the STEPS and LEAPS trials, several smaller studies investigating BWSTT as an adjunct to therapy have been conducted. In studies with chronic stroke samples, average (SD) treadmill training time was 25 (5) minutes (range, 20–30 minutes).3,7,11–13 The fact that BWSTT has shown some success—such as improvements in motor control,7 gait symmetry,7,11 functional ambulation including stair climbing,11 walking speed,1,14 lower extremity (LE) strength,14 gait coordination,14 and gait endurance14—in a population that has often plateaued5 has led to continued investigation of intervention strategies incorporating BWSTT to improve mobility in individuals with chronic stroke. For example, studies have been conducted in which BWSTT was examined in conjunction with overground training,10 LE strength training,9 resisted cycling,9 usual care consisting of a multidisciplinary approach,2,15 Bobath therapy,16 functionally oriented physical therapy,4 conventional physical therapy,6 a speed-dependent component to the BWSTT,17 and addition of functional electrical stimulation.14 However, research on the effects of interventions that include bouts of BWSTT of duration greater than 30 minutes and frequency greater than 3 sessions per week is limited. Further research is needed to determine whether the lack of consistent positive results is due to a dosage deficit.

Although the LEAPS randomized controlled trial is fairly definitive for that particular dosage (20–30 minutes of BWSTT and 15 minutes of overground training, 3 times per week),10 the question of whether an intervention with increased treadmill training duration and frequency improves outcomes in individuals with chronic stroke remains. The purpose of this study was to determine whether an intensive intervention including BWSTT demonstrates improved gait, balance, and mobility outcomes when compared with an intervention of equal duration and frequency, but with overground gait training in place of BWSTT, in a sample of individuals with chronic stroke. For the purposes of this study, the descriptor “intensive” refers to an increased duration (3 hours) and frequency (10 consecutive weekdays) of treatment sessions rather than to exertion during treatment activities.

Methods

Study procedures were approved by the University of South Carolina’s institutional review board. Before participation, all subjects reviewed and signed an informed consent document.

Participants

Individuals with chronic stroke (>6 months since stroke onset) who met all inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

| Age ≥ 18 years |

| Presence of unilateral hemiplegia |

Ability to:

|

| Exclusion criteria |

| Unable to ambulate 150 ft before stroke |

| Currently receiving therapy for balance, mobility, and/or gait |

Presence of any of the following:

|

Note: AD = assistive device; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT = deep venous thrombosis; LE = lower extremity; Min A = minimal assistance; Mod A = moderate assistance; PE = pulmonary embolism; ROM, range of motion.

Study design

A single-blind, randomized and matched control group design was used to compare an intensive intervention including BWSTT with a control intervention of equal duration and frequency, replacing BWSTT with overground gait training. A rolling approach to recruitment and enrollment was employed. An attempt was made to first match new participants (age ± 5 years and Berg Balance Scale [BBS] score ± 6 points) with an individual already participating. If there was a match, the new participant was assigned to the opposite group. If there was no match, the new participant was randomized to a group by a concealed drawing.

Intervention

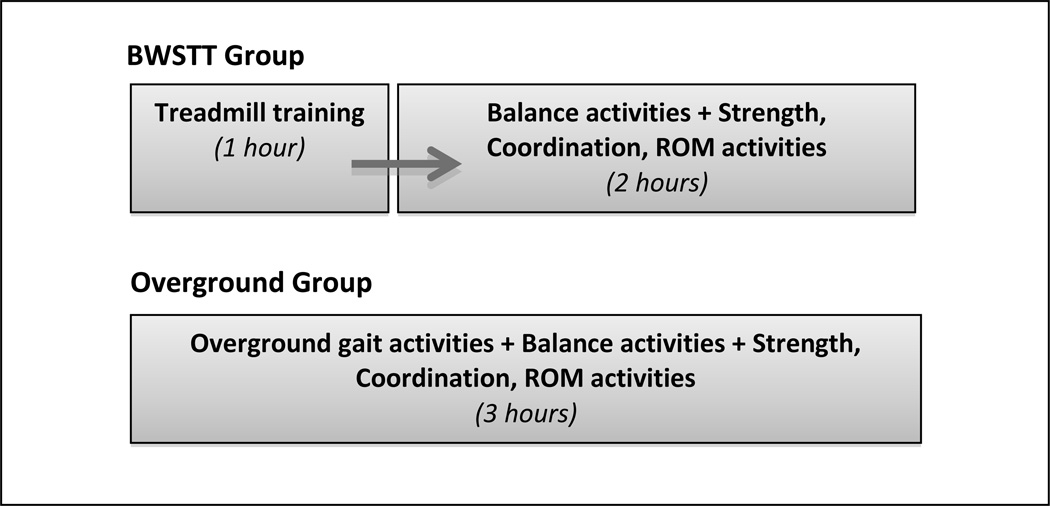

All participants were scheduled to receive 3 hours of intervention for 10 consecutive weekdays (total of 30 hours). The goal was to determine whether 10 days of intensive therapy could make a difference, similar to other intensive studies in individuals with chronic upper extremity deficits poststroke.18 This protocol is also based on intensive mobility training, which has been shown to be a feasible and effective approach for improving gait, balance, and mobility in individuals with chronic neurological conditions.19–21 In the experimental group, one-third of each treatment session was dedicated to gait training on a treadmill with body weight support (BWSTT); one-third to activities to improve balance, and one-third to activities to improve strength, range of motion (ROM), and coordination. Those in the control group received an intervention including the same components, except that the third of the session dedicated to gait training was performed overground rather than on a treadmill. For the experimental group, the BWSTT was delivered at the beginning of each treatment session; however, rather than delivering the non-treadmill treatment components (balance activities and strength, ROM, coordination activities plus overground gait for control group) in 1-hour blocks, these activities were intermixed. A log was kept during treatment sessions to ensure that time spent on each component totaled 50 to 60 minutes by the end of the session. Figure 1 shows the delivery of the treatment components for the 2 groups.

Figure 1.

Delivery of treatment components by group. BWSTT = body weight–supported treadmill training; ROM = range of motion.

For both groups, treatment activities were specific to each participant’s deficits and were progressed as appropriate to maintain a degree of difficulty that challenged the participant. Components were delivered in a massed practice schedule (repetitive practice, limited rest).22 Rest breaks were given as needed but were limited to less than 30 minutes per session. If 30 minutes of rest was exceeded, the session was extended the appropriate amount of time to ensure that a minimum of 150 minutes of intervention was completed. Description of each treatment component is provided in the following sections.

Gait training on treadmill (BWSTT, experimental group only)

Gait training was performed on a treadmill with the following objectives: (1) approach normal temporal parameters of gait,23,24 (2) maintain upright trunk, (3) approximate normal joint kinematics for LE joints, and (4) avoid excessive weight bearing on the upper extremities.25 Body weight support and manual, oral, and visual (mirror positioned in front of participants) cueing were provided as needed to meet these objectives. For participants requiring body weight support (ie, those unable to ambulate independently on the treadmill), the percentage supported by the overhead harness was set at a level that maximized bilateral limb loading without subsequent knee buckling (uncontrolled/premature knee flexion during stance phase). Body weight support ranged from 8% to 50% (mean [SD], 23.6% [12.8%]) on the first day of training and from 4% to 50% (mean [SD], 20.1% [13.7%]) on the final day of training. If the participant was unable to perform the stepping motion independently and/or demonstrated significant kinematic impairment, then manual cueing was used to assist. Both body weight support and manual cueing were constantly monitored and reduced as appropriate for each participant over the course of the intervention. This approach was not standardized, but was participant specific; reductions in body weight support and/or manual cueing occurred when the participant was able to ambulate independently and/or demonstrated kinematics approaching normal. Oral cueing was also provided as needed throughout treadmill training; as with manual cueing, trainers decreased oral cueing as the participant progressed. Concurrent with reductions in body weight support and cueing were increases in treadmill speed. The goal throughout treadmill training was to maximize walking speed while minimizing body weight support and cueing. Assistive devices were not used, nor were orthotics worn, during BWSTT. Standing rest breaks were given as needed.

Overground gait training (control group only)

Similar to BWSTT, the overground gait training component of the treatment session was designed to improve spatial and temporal parameters of gait as well as promote normal LE joint kinematics. However, all gait training performed by the control group was performed overground without the benefit of body weight support or every-step manual cueing (though manual cueing could be provided intermittently as needed). Unlike BWSTT, overground gait training activities were not performed in a continuous 1-hour block; rather, the activities were interspersed with the other 2 components of the intervention: balance activities and strength, ROM, and coordination activities (see Figure 1). Overground gait training also differed from BWSTT in that activities were performed in a variety of environments (eg, therapy gym, busy hallway, and outdoors) and included a wider array of activities (eg, side stepping, turns, and walking backwards). The activities selected and the progression of activities were individualized, with the objective of challenging gait abilities. Examples of task progression include increasing distance and/or speed of ambulation, eliminating or decreasing reliance on an assistive device, changing the environment to a more challenging surface, and adding a dual task.

Balance activities (both groups)

Treatment activities were designed to improve balance while encouraging the participant to use his or her more paretic LE. Examples include reaching outside base of support, performing activities on a compliant support surface, and performing activities with a reduced base of support (ie, tandem stance, single limb stance [SLS]).

Strength, ROM, coordination activities (both groups)

Treatment activities were designed to improve strength, ROM, and coordination of the paretic LE. Examples include positioning during activities to allow a long-duration stretch to muscle groups in the paretic LE, sit-to-stand transitions from variable height surfaces, and kicking or tapping targets with LEs.

Outcome measures

Assessments were conducted at baseline (average of 2 days before pretest; SD, 0.71; range, 1–4 days), pretest (1 day before intervention), posttest (1 day after intervention), and follow-up (average of 101 days after completion of intervention; SD, 20.14; range, 52–153 days). All measures were administered in a standardized process by a trained physical therapist blinded to treatment group. A single assessor was used, which decreased the threat of interrater reliability errors but prevented blinding to testing session. Information regarding the primary outcome measures administered at each testing session is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected outcome measures

| Measure | Assessing | Reliability/validity | MDC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step length differential36–38 | Spatial parameters of gait (via GAITRite) | Valid and reliable measure of spatiotemporal parameters of gait in individuals with chronic stroke | No reported MDC for included parameter |

| 3-meter walk test 38–40 | Self-selected (SS) and fast (F) walking speed | Walking speed is valid and reliable measure for individuals with chronic stroke | 0.18 m/s (SS) and 0.13 m/s (F) for individuals with chronic stroke |

| 6-minute walk test 39 | Gait capacity | Reliable measure in individuals with chronic stroke | 13% for individuals with chronic stroke |

| Berg Balance Scale 38,41 | Balance | Reliable, valid, and sensitive measure for individuals with stroke | 5 points for individuals with chronic stroke |

| Dynamic Gait Index 42 | Ability to adapt to changing task demands during gait | Reliable, valid, and responsive measure for individuals with stroke | 4 points for individuals with stroke |

| Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale 34–36,43–45 | Self-reported balance confidence | Good test-retest reliability, excellent internal consistency, construct validity, and minimal floor and ceiling effects for individuals with stroke | 14 points for individuals with stroke |

| Single limb stance 46 | Balance | Reproducible and valid measure of postural control in the chronic stroke population | 74% (paretic LE) for individuals with chronic stroke |

| Timed Up and Go 36,38,39 | Speed during upright mobility | Reliable and valid for individuals with stroke | 7.84 seconds for individuals with chronic stroke |

| Fugl-Meyer Scale Lower Extremity subscale 38,47 | Balance and LE motor and sensory function, ROM, pain | Valid, reliable, and responsive measure for individuals with stroke | 4 points for individuals with chronic stroke |

| Stroke Impact Scale, percent perceived recovery 48 | Self-reported perceived recovery | Associated with activity participation in individuals with mild stroke | No reported MDC for the included subscale |

Note: LE = lower extremity; MDC = minimal detectable change; ROM = range of motion.

See the Appendix for information regarding administration of the following outcome measures: GAITRite (CIR Systems Inc., Sparta, NJ), 3-meter walk test (3MWT), 6-minute walk test (6MWT), SLS, Timed Up and Go (TUG), and Stroke Impact Scale (SIS).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to characterize sample demographics. Unpaired t tests and Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to examine potential group differences. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard error) were calculated for all outcome measures at each assessment period for the 2 groups individually and for the 2 groups combined. Repeated-measures analyses of variance determined changes over time and between groups. A post hoc Tukey-Kramer analysis was performed to locate any significant differences. Percentage of participants meeting or exceeding published minimal detectable change (MDC) scores for selected outcome measures (those for which an MDC relevant to our population was available in the literature) were calculated. The previously listed statistical analyses were completed using all available data. Effect sizes using the formula (meanA – meanB)/std devA were computed. For effect sizes, an intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed to provide a more conservative estimate. For the ITT analysis, pretest scores were used in place of missing posttest and/or follow-up scores. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) and IBM SPSS Statistics 21 software (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Participants

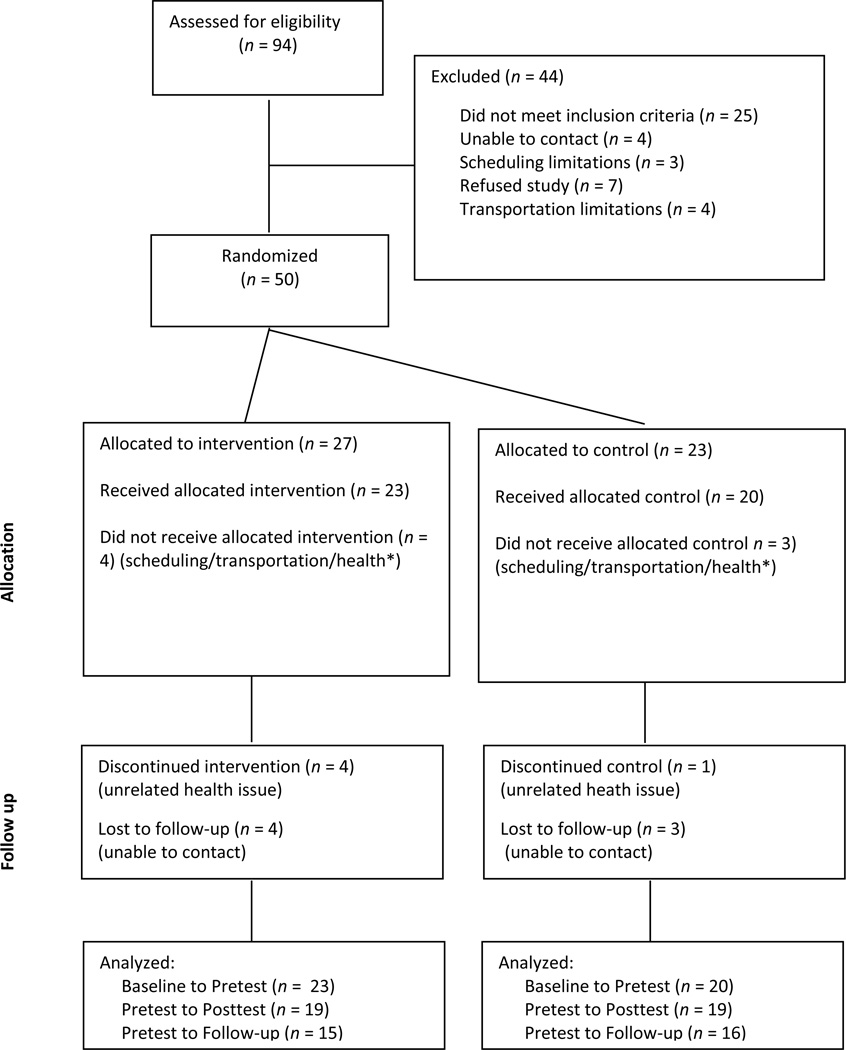

After screening, 43 participants who met all inclusion criteria were recruited into the study. See Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (Figure 2) for specifics on participant flow from screening through data analysis. Average age of the sample was 61.47 years with a mean time since stroke of 40.47 months. Twenty-three participants were randomized to the BWSTT group and 20 participants to the Overground group. Demographic information is detailed in Table 3. Nineteen (82.6%) of the participants in the BWSTT group completed training, and 15 (65.2%) returned for follow-up testing. Retention was better in the Overground group, with 19 participants (95%) completing training and 16 (80%) returning for follow-up testing. At baseline, the groups differed on the 3MWT at self-selected walking speed (BSWTT: 0.67 ± 0.29 m/s; Overground: 0.50 ± 0.20 m/s; P = .03) and the 6MWT (BSWTT: 320.98 ± 145.25 m; Overground: 235.16 ± 118.95 m; P = .04).

Figure 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram showing flow of participants through each stage of this randomized trial. *Participants screened and randomly assigned to groups because of initial interest but unable to participate because of scheduling, transportation, or personal or family health issues. Intervention not initiated.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of the study sample

| Characteristics | BWSTT (n= 23) |

Overground (n= 20) |

Combined (n= 43) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.39 | 60.70 | 61.47 | .871 |

| SD | 15.69 | 11.43 | 13.48 | |

| Range | 23–86 | 41–82 | 23–86 | |

| Time since stroke (mo) | 50.41 | 29.03 | 40.47 | .125 |

| SD | 56.80 | 23.90 | 45.44 | |

| Range | 7.2–224.0 | 8.7–113.2 | 7.2–224.0 | |

| Side of hemiparesis | .724 | |||

| Left (%) | 8 (35) | 8 (40) | 16 (37) | |

| Right (%) | 15 (65) | 12 (60) | 27 (63) | |

| Sex | .173 | |||

| Male (%) | 14 (61) | 16 (80) | 30 (70) | |

| Female (%) | 9 (39) | 4 (20) | 13 (30) | |

| Drop-outs (%)a | 4 (17) | 1 (5) | 5 (12) | .206 |

| Lost to follow-up (%) | 4 (21) | 3 (16) | 7 (18) | .832 |

| Assistive device | ||||

| SPC (%) | 4 (17) | 3 (15) | 7 (16) | .832 |

| QC (%) | 2 (9) | 2 (10) | 4 (9) | .883 |

| RW (%) | 1 (4) | 2 (10) | 3 (7) | .468 |

| Orthoticb | ||||

| AFO (%) | 5 (22) | 4 (20) | 9 (21) | .889 |

| KAFO (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | .278 |

Note: AFO = ankle-foot orthosis; KAFO = knee-ankle-foot orthosis; QC = quad cane; RW = rolling walker; SPC = single point cane.

Drop-outs = participants who started but did not complete the intervention phase.

Lost to follow-up = participants who completed the intervention phase but did not return for follow-up.

Between-group comparisons

No significant differences (α = 0.05) were found between groups on any of the outcome measures assessed either immediately after training (pretest to posttest) or over the long term (pretest to follow-up). For this reason, groups were combined for all remaining analyses. Table 4 shows outcome data for the BWSTT and Overground groups.

Table 4.

Change across testing sessions of BWSTT and Overground groups for all outcomes

| Δ Pretest to posttest (SD) |

Δ Pretest to follow-up (SD) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome measure | BWSTT (n= 19) |

Overground (n= 19) |

P value |

BWSTT (n= 15) |

Overground (n= 16) |

P value |

| Step length differential (cm) | −0.6 (1.71) |

−1.7 (3.30) |

.20 | −1.4 (2.08) |

2.6 (9.35) |

.12 |

| Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale | 5.4 (9.29) |

10.7 (16.18) |

.23 | 5.7 (11.39) |

6.6 (14.34) |

.85 |

| Berg Balance Scale | 1.5 (1.95) |

1.6 (2.06) |

.87 | 0.9 (2.33) |

0.6 (2.09) |

.76 |

| Single limb stancea (sec) | 1.8 (3.94) |

2.7 (6.56) |

.62 | 1.5 (6.30) |

−0.4 (9.28) |

.53 |

| 3-Meter walk test Self-selected (m/s) | 0.02 (0.10) |

0.02 (0.07) |

.91 | 0.06 (0.27) |

0.04 (0.09) |

.81 |

| 3-Meter walk test fast (m/s) | 0.1 (0.09) |

0.0 (0.09) |

.05 | 0.0 (0.11) |

0.0 (0.12) |

.32 |

| Dynamic Gait Index | 2.8 (2.42) |

1.9 (2.26) |

.28 | 1.4 (2.10) |

1.5 (2.29) |

.93 |

| Fugl-Meyer–LE subscale | 1.5 (1.84) |

1.2 (2.23) |

.60 | 1.5 (1.68) |

0.9 (2.25) |

.60 |

| Timed Up and Gob (sec) | −1.3 (1.83) |

−4.3 (8.22) |

.21 | −0.1 (2.21) |

−4.3 (10.19) |

.20 |

| 6-Minute walk test (m) | 17.0 (58.68) |

4.3 (46.82) |

.50 | 6.7 (45.32) |

−17.0 (85.52) |

.40 |

| Stroke Impact Scale, % perceived recovery | 7.9 (9.47) |

3.3 (10.57) |

.20 |

7.1 (15.31) |

6.8 (14.68) |

.96 |

Note: Δ = change; BWSTT = body weight–supported treadmill training; LE = lower extremity.

Average of 3 trials performed on participant’s preferred lower extremity.

Timed Up and Go data nonparametric, nonparametric significance testing was used for analysis.

Repeated measures with groups combined

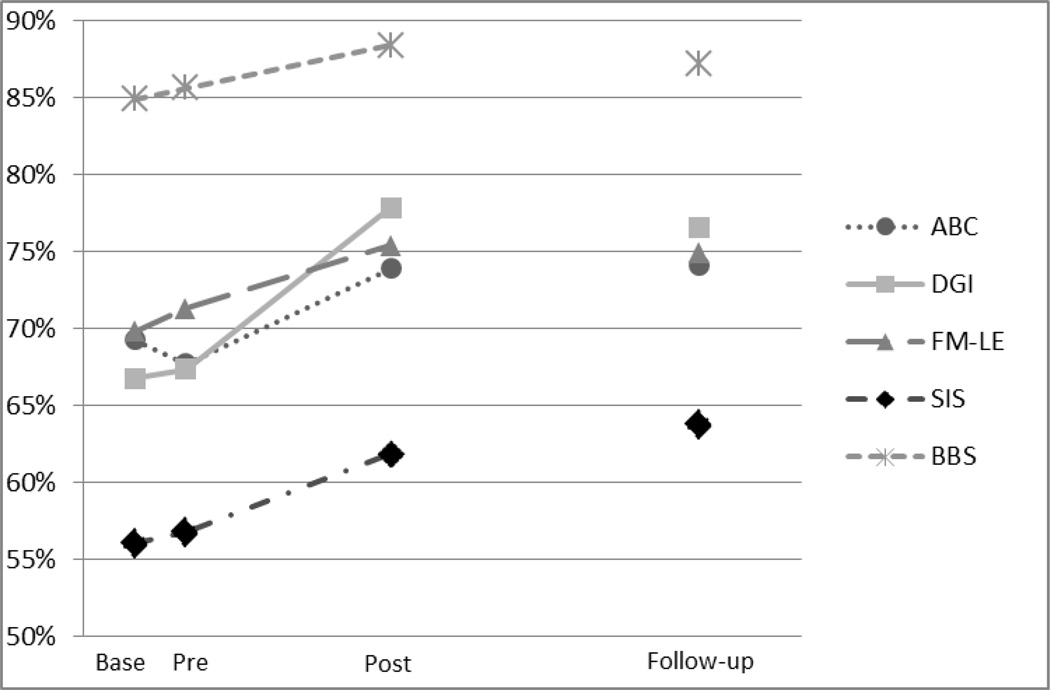

With the exception of the 3MWT at “fast” walking speed, baseline to pretest comparisons (no intervention) revealed no significant differences for any of the outcome measures assessed. Pretest to posttest analysis revealed significant differences (α = 0.05) on 7 of the 11 outcome measures after intervention. Four of these measures remained significant at follow-up testing (pretest to follow-up analysis). Outcome data are presented in Table 5. Figure 3 shows changes across testing sessions in selected outcome measures (ie, those that result in a score that falls on a scale with a total possible score) represented as percentages of total possible score.

Table 5.

Average response, significance, and effect size across testing sessions for all outcome measures

| Average response (SE) | P values | Effect size (ITT) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Outcome measure |

Baseline (n = 43) |

Pretest (n = 43) |

Posttest (n = 38) |

Follow-up (n = 31) |

Baseline to pretest (n = 43) |

Pretest to posttest (n= 38) |

Pretest to follow- up (n= 31) |

Pretest to posttesta |

Pretest to follow- upa |

| Step length differential (cm) |

7.4 (0.72) |

7.1 (0.73) |

6.0 (0.76) |

7.9 (0.84) |

.97 | .41 | .85 |

0.20 (0.13) |

−0.11 (−0.15) |

| Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale (0–100)b |

69.2 (1.45) |

67.9 (1.45) |

75.4 (1.58) |

74.1 (1.80) |

.90 | .001 | .04 |

0.41 (0.35) |

0.29 (0.22) |

| Single limb stance (sec) |

9.7 (1.22) |

10.7 (1.19) |

12.9 (1.20) |

10.9 (1.33) |

.73 | .10 | 1.00 |

0.17 (0.14) |

0.04 (0.03) |

| 3-meter walk test Self-selected (m/s) |

0.59 (0.03) |

0.62 (0.03) |

0.64 (0.04) |

0.67 (0.04) |

.56 | .80 | .31 |

0.07 (0.07) |

0.19 (0.15) |

| 3-meter walk test fast (m/s) |

0.83 (0.01) |

0.88 (0.01) |

0.94 (0.01) |

0.90 (0.02) |

.03 | .005 | .77 |

0.16 (0.15) |

0.05 (0.04) |

| Dynamic Gait Index (0–24)b |

16.1 (0.27) |

16.4 (0.27) |

18.8 (0.30) |

18.0 (0.34) |

.90 | <.0001 | .001 |

0.60 (0.54) |

0.40 (0.26) |

| Timed Up and Goc (sec) |

15.0 (10.6,25.5) |

14.8 (11.3,22.9) |

14.3 (10.2,24.3) |

14.4 (9.54,21.1) |

.13 | <.001 | .11 |

0.17 (0.15) |

0.13 (0.10) |

| Fugl-Meyer–LE subscale (0–34)b |

23.8 (0.23) |

24.4 (0.23) |

25.7 (0.25) |

25.6 (0.29) |

.30 | .001 | .01 |

0.28 (0.26) |

0.25 (0.19) |

| 6-minute walk test (m) |

281.1 (8.57) |

297.5 (8.57) |

304.9 (9.09) |

293.4 (10.18) |

.23 | .85 | .99 |

0.07 (0.04) |

−0.04 (−0.03) |

| Stroke Impact Scale, % perceived recovery (0–100)b |

56.8 (13.11) |

57.4 (13.11) |

63.1 (13.13) |

65.0 (13.16) |

.98 | .002 | .01 |

0.30 (0.27) |

0.36 (0.26) |

| Berg Balance Scale (0–54)b |

46.7 (0.31) |

47.5 (0.31) |

49.1 (0.33) |

48.2 (0.37) |

.09 | <.0001 | .38 |

0.23 (0.20) |

0.10 (0.08) |

Note: Values presented below each average are the associated SE. Values in parentheses are units of measure or range for each outcome measure. P values < .05 are significant. ITT = intention to treat; SE = standard error.

Effect sizes for completers are presented in bold; effect sizes from intent-to-treat analysis are presented in italics.

Outcomes represented in Figure 3.

Timed Up and Go data nonparametric. Median presented in place of mean and 25th, 50th quartiles in place of SE.

Figure 3.

Changes across testing sessions represented as percentages of total possible score. ABC = Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale; Base = baseline assessment period; BBS = Berg Balance Scale; DGI = Dynamic Gait Index; FM-LE = Fugl-Meyer Lower Extremity subscale; Post = posttest assessment period; Pre = pretest assessment period; SIS = Stroke Impact Scale. Standard errors for included outcome measures are presented in Table 3.

Effect size

Although for a majority of the outcome measures, the effect sizes were small to moderate (small = 0.20, medium = 0.50, and large = 0.80),26 and all effect sizes were in a direction indicating improvement. The largest effect size was seen for the Dynamic Gait Index (DGI). Effect sizes are included in Table 5.

MDC

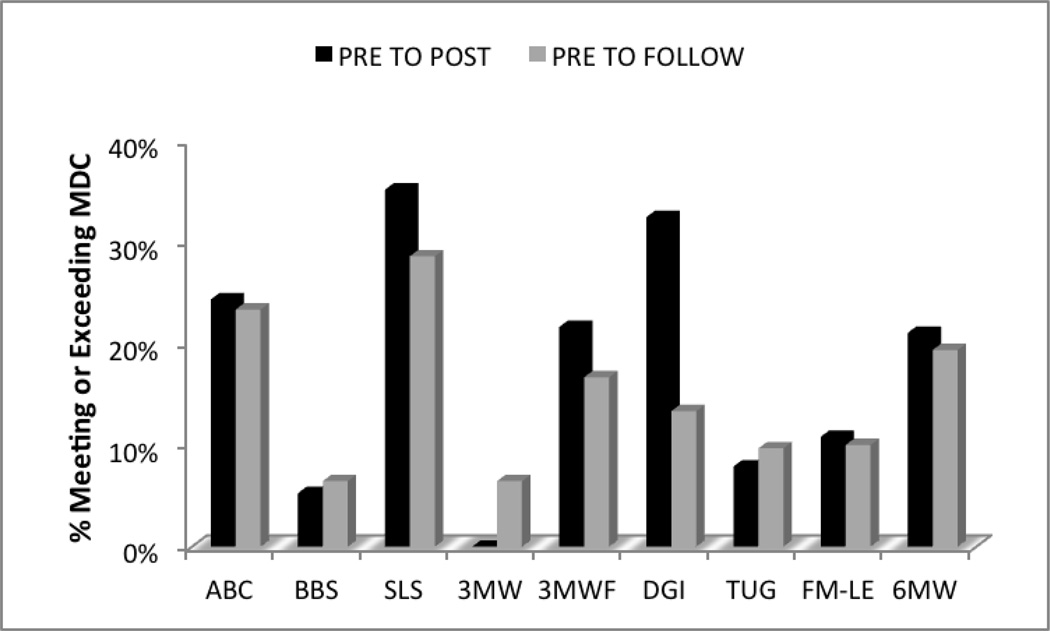

To examine how meaningful the improvements observed in the outcome measures were, we calculated the percentage of participants meeting or exceeding the MDC for all measures with a published MDC specific to our population. As seen in Figure 4, approximately one-third of the participants met or exceeded the MDC for SLS and DGI immediately after intervention.

Figure 4.

Percentage of participants meeting or exceeding minimal detectable change (MDC). MDCs for included outcome measures are presented in Table 2 (Methods). 3WMT = 3-meter walk test; 6MWT = 6-minute walk test; ABC = Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale; BBS = Berg Balance Scale; DGI = Dynamic Gait Index; FM-LE = Fugl-Meyer Lower Extremity subscale; SLS = single limb stance; TUG = Timed Up and Go.

Discussion

The literature suggests that BWSTT does not provide superior outcomes in walking ability in individuals with stroke compared with interventions including traditional overground gait training10,27 or structured home exercise programs.10 However, treadmill dosage has varied (4–54 therapy hours), and practice schedule has mainly been distributed.10,28 This study incorporated approximately 10 hours of gait training (over a 10-day period) using a massed practice schedule. In addition, the researchers combined gait training (BWSTT or overground) with balance and strength components for a more comprehensive approach to treat loss of mobility—an approach suggested to maximize walking recovery.29 The results of this study are in line with the current literature, indicating no significant difference in functional outcomes (gait, balance, and mobility) between participants completing treadmill training (BWSTT) and participants in a treatment control group (overground gait training). A possible explanation for the similar response seen between these 2 approaches may be that both provide intensive, task-specific interventions. Evidence supports the efficacy of intensive, task-specific approaches in stroke rehabilitation.5,30

Although the between-group analysis revealed no difference in outcomes between the 2 groups after intervention, the magnitude of the standard deviations (Table 4) indicates that response to intervention varied widely within each group. This suggests that some individuals with chronic stroke are responders to intensive interventions while others are not. Determining the characteristics unique to responders will allow interventions of this nature to be targeted to appropriate individuals.

Once it was determined that BWSTT did not produce significantly greater changes in outcomes, treatment groups were combined to assess the efficacy of an intensive approach: 30 hours of intervention over 10 days. The findings suggest that individuals with chronic stroke can demonstrate improvements in gait, balance, and mobility after intensive therapy. Although only limited improvements were maintained 3 months after participation, the fact that improvements were maintained at all is encouraging, considering the heterogeneous population with chronic stroke and the limited length of the intervention (10 days). No recommendations for continued activity were given to participants after completion of the intervention phase, providing some support for the belief that the improvements seen at follow-up resulted from the intervention rather than activities performed in the interim.

Independent ambulation is a top rehabilitation priority after stroke.31 Although self-selected walking speed did not significantly improve immediately after the intervention, our results show that participants did have improved ability to significantly increase their walking speed, as seen by increased “fast” walking speeds at posttest. We acknowledge that baseline to pretest fast walking speeds were also significant, possibly limiting the meaningfulness of the change found with intervention. However, more than 20% of participants met or exceeded the MDC for fast walking speed between pretest and posttest. The ability to increase speed during activities of daily living, such as crossing the street or avoiding environmental obstacles, is helpful for successful community ambulation. Our findings vary from those of the LEAPS and STEPS trials, which revealed significant improvements in self-selected walking speed and fast walking speeds.9,10 The discrepancy in findings between our study and these trials may be a result of differences in chronicity of the subjects’ conditions. The subjects in the LEAPS trial participated at either 2 months or 6 months poststroke, which would allow for some spontaneous recovery during the trial; the subjects in this study averaged 3.3 years poststroke. The findings of this study, with larger improvements observed in balance compared with gait, however, are consistent with results of previous pilot research on intensive therapy in individuals with chronic stroke.21

A critical component to successful ambulation is balance. The increase in fast walking speed observed after intervention could also be an indication of improved balance, as participants may have felt safer walking at faster speeds. In addition, subjects displayed improvements in both objective and subjective reports of balance. Subjects demonstrated improved stability during standing balance tasks (BBS), as well as dynamic balance during ambulation (DGI). Subjectively, participants reported being more confident in their ability to complete tasks that challenged their balance, as seen through improved scores for the sample as a whole on the Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale. The improvements in balance are further supported by the percentage of individuals meeting or exceeding the MDC values on balance measures. Both the SLS and DGI displayed the most convincing argument for true change, with more than one-third of participants exceeding the MDC (refer to Figure 3).

Participant views of recovery are an important aspect to consider in addition to objective outcomes. Despite the modest objective findings in this study, participants reported significant increases in perceived recovery, and these perceived increases were maintained over time (3 months). Although these findings are only a result of a single subjective questionnaire, they indicate that participants perceive a positive change in their recovery and continue to feel this way 3 months after participation. This information provides insight into the patient perspectives domain of evidence-based practice.

Study limitations

A possible limitation of this study was the length of the intervention. The intervention was 10 days in an effort to assess the efficacy of high dosage in a condensed schedule. Although outcomes did display improvement, the effect sizes were only moderate, demonstrating that the length of the intervention was perhaps too short. Another potential limitation is the lack of consistency in the timing of follow-up testing sessions. The goal was 3 months after completion of the intervention phase; however, because of scheduling issues, actual timing ranged from 52 to 153 days (average, 101; SD, 20.14). The discrepancy in length of follow-up among participants may have influenced the results.

Conclusions

Research has demonstrated that clinicians do not need expensive, state-of-the-art equipment such as a body weight–supported treadmill system to achieve functional gains in individuals with chronic stroke.9,10,27 What remains unclear, however, is the intervention dosage required for maximal benefit. The results of this study indicate that individuals with chronic stroke can make significant changes in gait, balance, and mobility after only 10 days of therapy. Although effect sizes were moderate, they indicated a tendency for improvement. It is not known what functional gains might be seen after 20 or 30 days of therapy at a similar intensity (eg,15 h/wk). Can individuals with chronic stroke continue to make functional improvements over time?

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted in the University of South Carolina’s Rehabilitation Laboratory, which is part of the Department of Exercise Science, Physical Therapy Program, Columbia, South Carolina.

Financial support/disclosures: This work was funded by a grant from the American Heart Association (Scientist Development Grant, 0835160N). One subject from this study was included in a previously published work. The subject’s data are included in an article published in the Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy (September 2011) titled “Feasibility of Intensive Mobility Training to Improve Gait, Balance, and Mobility in Persons with Chronic Neurological Conditions: A Case Series.” Separately, collected data from the same sample were used for a qualitative assessment of this intervention and accepted in Physical Therapy Journal for September 2013 publication. In addition, the information from this study has been presented at the American Physical Therapy Association’s combined sections meeting in poster format February 9–12, 2009; February 17–10, 2010; February 9–12, 2011; and February 8–11, 2012; and as poster and platform February 3–6, 2014. Components of the data and methods were presented at the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine meeting; November 13–16, 2013.

Appendix

GAITRite

The GAITRite is a portable instrumented walkway system, approximately 5.3 m long, embedded with pressure-activated sensors that detect a series of footfalls as an individual walks across the length of the mat. The active area of the mat is 4.42 m long and 66 cm wide, with sensors placed 1.27 cm apart. Data are sampled from the walkway at a frequency of 80 Hz. Step length differential data were collected using the GAITRite and are included in our analysis to determine changes in a spatial parameter of gait after intervention. The participants in this study were allowed 2 m for acceleration/deceleration outside the data collection area to help reduce gait variability introduced during these phases.32,33 Three trials were performed using any assistive device (AD) and/or orthoses typically worn by the participant during community ambulation, which reflects the protocol used in the study by Lewek and Randall34 examining reliability and minimal detectable changes (MDCs) of spatiotemporal assymetry as assessed by the GAITRite in individuals with chronic stroke.

3-meter walk test (3MWT)

The 3MWT was administered to assess walking speed. Three trials were performed at comfortable and fast walking speeds. As with the GAITRite, participants were permitted to use any AD and/or orthoses typically worn during community ambulation. Instructions for comfortable pace: “Please walk as you would if you were taking a stroll through the park, so at a comfortable pace.” Instructions for fast pace: “Please walk as if you are crossing the street and the light is about to change, so at a fast but safe speed.” For both protocols, lines were placed on the floor marking the starting and stopping points for participants, as well as outlining the 3-m timed walking area. Two meters were provided on either side of the timed portion to allow for acceleration and deceleration.32,33 The examiner started timing as soon as the participant’s leg crossed the first 3-m marker and stopped when the participant’s first leg crossed the second marker.

6-minute walk test (6MWT)

The 6MWT was administered to assess gait endurance. The measure provides information on lower extremity (LE) strength and gait capacity in individuals with stroke.35 As with the other gait measures, participants were permitted to use any AD and/or orthoses typically worn during community ambulation. Participants ambulated in a hallway for 6 minutes with standing rest breaks as needed. The evaluator did not walk alongside the participant, and talking was discouraged. Distance ambulated was measured in meters.

Single limb stance (SLS)

Participants were timed during performance of item 14 of the Berg Balance Scale (“Stand on one leg as long as you can without holding”).

Timed Up and Go (TUG)

The TUG was administered to evaluate participants’ speed during upright mobility. The test required the participant to stand up from a chair, walk 3 m, turn around, walk 3 m back, and return to a seated position. Instructions were given to walk at a “safe, swift, but comfortable” pace.

Stroke Impact Scale (SIS), percent perceived recovery (PR)

The final page of the SIS was administered to determine each participant’s percentage of PR. The question was presented as a visual scale ranging from 0 (no recovery) to 100 (full recovery), and the participant indicated the point on the scale that represented his or her PR.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Combs SA, Dugan EL, Ozimek EN, Curtis AB. Bilateral coordination and gait symmetry after body-weight supported treadmill training for persons with chronic stroke. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2013;28(4):448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Cunha IT, Jr, Lim PA, Qureshy H, Henson H, Monga T, Protas EJ. Gait outcomes after acute stroke rehabilitation with supported treadmill ambulation training: A randomized controlled pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(9):1258–1265. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.34267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornby TG, Campbell DD, Kahn JH, Demott T, Moore JL, Roth HR. Enhanced gait-related improvements after therapist-versus robotic-assisted locomotor training in subjects with chronic stroke: A randomized controlled study. Stroke. 2008;39(6):1786–1792. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.504779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosak MC, Reding MJ. Comparison of partial body weight-supported treadmill gait training versus aggressive bracing assisted walking post stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2000;14(1):13–19. doi: 10.1177/154596830001400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore JL, Roth EJ, Killian C, Hornby TG. Locomotor training improves daily stepping activity and gait efficiency in individuals poststroke who have reached a “plateau” in recovery. Stroke. 2010;41(1):129–135. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.563247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson L, Carlsson J, Danielsson A, et al. Walking training of patients with hemiparesis at an early stage after stroke: A comparison of walking training on a treadmill with body weight support and walking training on the ground. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15(5):515–527. doi: 10.1191/026921501680425234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribeiro T, Britto H, Oliveira D, Silva E, Galvao E, Lindquist A. Effects of treadmill training with partial body weight support and the proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation method on hemiparetic gait: A comparative study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2013;49(4):451–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moseley AM, Stark A, Cameron ID, Pollock A. Treadmill training and body weight support for walking after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD002840. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002840.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan KJ, Brown DA, Klassen T, et al. Effects of task-specific locomotor and strength training in adults who were ambulatory after stroke: Results of the STEPS randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2007;87(12):1580–1602. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan PW, Sullivan KJ, Behrman AL, et al. Body-weight-supported treadmill rehabilitation after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):2026–2036. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam T, Luttmann K, Houldin A, Chan C. Treadmill-based locomotor training with leg weights to enhance functional ambulation in people with chronic stroke: A pilot study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2009;33(3):129–135. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e3181b57de5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suputtitada A, Yooktanan P, Rarerng-Ying T. Effect of partial body weight support treadmill training in chronic stroke patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87(Suppl 2):S107–S111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Combs SA, Dugan EL, Ozimek EN, Curtis AB. Effects of body-weight supported treadmill training on kinetic symmetry in persons with chronic stroke. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2012;27(9):887–892. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daly JJ, Zimbelman J, Roenigk KL, et al. Recovery of coordinated gait: randomized controlled stroke trial of functional electrical stimulation (FES) versus no FES, with weight-supported treadmill and over-ground training. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25(7):588–596. doi: 10.1177/1545968311400092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ada L, Dean CM, Morris ME, Simpson JM, Katrak P. Randomized trial of treadmill walking with body weight support to establish walking in subacute stroke: The MOBILISE trial. Stroke. 2010;41(6):1237–1242. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.569483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eich HJ, Mach H, Werner C, Hesse S. Aerobic treadmill plus Bobath walking training improves walking in subacute stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18(6):640–651. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr779oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pohl M, Mehrholz J, Ritschel C, Ruckriem S. Speed-dependent treadmill training in ambulatory hemiparetic stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2002;33(2):553–558. doi: 10.1161/hs0202.102365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritz SL, Butts RJ, Wolf SL. Constraint-induced movement therapy: From history to plasticity. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(2):191–198. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritz S, Merlo-Rains A, Rivers E, et al. Feasibility of intensive mobility training to improve gait, balance, and mobility in persons with chronic neurological conditions: A case series. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2011;35(3):141–147. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e31822a2a09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fritz SL, Merlo-Rains AM, Rivers ED, et al. An intensive intervention for improving gait, balance, and mobility in individuals with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury: A pilot study of activity tolerance and benefits. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(11):1776–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fritz SL, Pittman AL, Robinson AC, Orton SC, Rivers ED. An intense intervention for improving gait, balance, and mobility for individuals with chronic stroke: A pilot study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(2):71–76. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e3180674a3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ. Improving Functional Outcomes in Physical Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbeau H, Rossignol S. Recovery of locomotion after chronic spinalization in the adult cat. Brain Res. 1987;412(1):84–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91442-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edgerton VR, Roy RR, Hodgson JA, Prober RJ, de Guzman CP, de Leon R. Potential of adult mammalian lumbosacral spinal cord to execute and acquire improved locomotion in the absence of supraspinal input. J Neurotrauma. 1992;9(Suppl 1):S119–S128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behrman AL, Harkema SJ. Locomotor training after human spinal cord injury: A series of case studies. Phys Ther. 2000;80(7):688–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobkin BH, Duncan PW. Should body weight-supported treadmill training and robotic-assistive steppers for locomotor training trot back to the starting gate? Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26(4):308–317. doi: 10.1177/1545968312439687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan PW, Sullivan KJ, Behrman AL, et al. Protocol for the Locomotor Experience Applied Post-stroke (LEAPS) trial: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol. 2007;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowden MG, Embry AE, Gregory CM. Physical therapy adjuvants to promote optimization of walking recovery after stroke. Stroke Res Treat. 2011;2011:601416. doi: 10.4061/2011/601416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macko RF, Ivey FM, Forrester LW, et al. Treadmill exercise rehabilitation improves ambulatory function and cardiovascular fitness in patients with chronic stroke: A randomized, controlled trial. Stroke. 2005;36(10):2206–2211. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000181076.91805.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowden MG, Behrman AL, Neptune RR, Gregory CM, Kautz SA. Locomotor rehabilitation of individuals with chronic stroke: Difference between responders and nonresponders. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(5):856–862. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graham JE, Ostir GV, Fisher SR, Ottenbacher KJ. Assessing walking speed in clinical research: A systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(4):552–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindemann U, Najafi B, Zijlstra W, et al. Distance to achieve steady state walking speed in frail elderly persons. Gait Posture. 2008;27(1):91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewek MD, Randall EP. Reliability of spatiotemporal asymmetry during overground walking for individuals following chronic stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2011;35(3):116–121. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e318227fe70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pradon D, Roche N, Enette L, Zory R. Relationship between lower limb muscle strength and 6-minute walk test performance in stroke patients. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45:105–108. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng SS, Hui-Chan CW. The timed up & go test: Its reliability and association with lower-limb impairments and locomotor capacities in people with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(8):1641–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stokic DS, Horn TS, Ramshur JM, Chow JW. Agreement between temporospatial gait parameters of an electronic walkway and a motion capture system in healthy and chronic stroke populations. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88(6):437–444. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181a5b1ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiengkaew V, Jitaree K, Chaiyawat P. Minimal detectable changes of the Berg Balance Scale, Fugl-Meyer Assessment Scale, Timed “Up & Go” Test, gait speeds, and 2-minute walk test in individuals with chronic stroke with different degrees of ankle plantarflexor tone. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(7):1201–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flansbjer UB, Holmback AM, Downham D, Patten C, Lexell J. Reliability of gait performance tests in men and women with hemiparesis after stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(2):75–82. doi: 10.1080/16501970410017215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green J, Forster A, Young J. Reliability of gait speed measured by a timed walking test in patients one year after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16(3):306–314. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr495oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blum L, Korner-Bitensky N. Usefulness of the Berg Balance Scale in stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review. Phys Ther. 2008;88(5):559–566. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin JH, Hsu MJ, Hsu HW, Wu HC, Hsieh CL. Psychometric comparisons of 3 functional ambulation measures for patients with stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(9):2021–2025. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.589739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powell LE, Myers AM. The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50A(1):M28–M34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.1.m28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salbach NM, Mayo NE, Hanley JA, Richards CL, Wood-Dauphinee S. Psychometric evaluation of the original and Canadian French version of the activities-specific balance confidence scale among people with stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(12):1597–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.08.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Botner EM, Miller WC, Eng JJ. Measurement properties of the Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale among individuals with stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(4):156–163. doi: 10.1080/09638280400008982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flansbjer UB, Blom J, Brogårdh C. The reproducibility of Berg Balance Scale and the Single-leg Stance in chronic stroke and the relationship between the two tests. PM R. 2012;4(3):165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsueh IP, Hsu MJ, Sheu CF, Lee S, Hsieh CL, Lin JH. Psychometric comparisons of 2 versions of the Fugl-Meyer Motor Scale and 2 versions of the Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22(6):737–744. doi: 10.1177/1545968308315999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolf T, Koster J. Perceived recovery as a predictor of physical activity participation after mild stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(14):1143–1148. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.720635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]