Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily is evolutionarily conserved and plays fundamental roles in cell growth and differentiation. Mounting evidence supports its important role in female reproduction and development. TGFBs1-3 are founding members of this growth factor family, however, the in vivo function of TGFβ signaling in the uterus remains poorly defined. By drawing on mouse and human studies as a main source, this review focuses on the recent progress on understanding TGFβ signaling in the uterus. The review also considers the involvement of dysregulated TGFβ signaling in pathological conditions that cause pregnancy loss and fertility problems in women.

Keywords: Decidualization, Development, Embryonic development, Implantation, Myometrium, Pregnancy, Transforming growth factor β, Uterus

Introduction

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily proteins are versatile and fundamental regulators in metazoans. The TGFβ signal transduction pathway has been extensively studied. The application of mouse genetic approaches has catalyzed the identification of the roles of core signaling components of TGFβ superfamily members in reproductive processes. Recent studies using tissue/cell-specific knockout approaches represent a milestone towards understanding the in vivo function of TGFβ superfamily signaling in reproduction and development. These studies have yielded new insights into this growth factor superfamily in uterine development, function, and diseases. This review will focus on TGFβ signaling in the uterus, primarily using results from studies with mice and humans.

TGFβ superfamily

Core components of the TGFβ signaling pathway

Core components of the TGFβ signaling pathway consist of ligands, receptors, and SMA and MAD (mother against decapentaplegic)-related proteins (SMAD). TGFβ ligands bind to their receptors and impinge on SMADs to activate gene transcription. TGFβ superfamily ligands include TGFβs, activins, inhibins, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), growth differentiation factors (GDFs), anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), and nodal growth differentiation factor (NODAL). Seven type I (i.e., ACVRL1, ACVR1, BMPR1A, ACVR1B, TGFBR1, BMPR1B, and ACVR1C) and five type II receptors (i.e., TGFBR2, ACVR2, ACVR2B, BMPR2, and AMHR2) have been identified [1–4]. SMADs are intracellular transducers. In mammalian species, eight SMAD proteins have been identified and are classified into receptor-regulated SMADs (R-SMADs; SMAD1, 2, 3, 5, and 8), common SMAD (Co-SMAD), and inhibitory SMADs (I-SMADs; SMAD6 and SMAD7). R-SMADs are tethered by SMAD anchor for receptor activation (SARA) [5]. In general, SMAD1/5/8 mediate BMP signaling, whereas SMAD2/3 mediate TGFβ and activin signaling. SMAD6 and SMAD7 can bind type I receptors and inhibit TGFβ and/or BMP signaling [6, 7]. A plethora of ligands versus a fixed number of receptors and SMADs suggests the usage of shared receptor(s) and SMAD cell signaling molecules in this system.

TGFβ signaling paradigm: canonical versus non-canonical pathway

To initiate signal transduction, a ligand forms a heteromeric type II and type I receptor complex, where the constitutively active type II receptor phosphorylates type I receptor at the glycine and serine (GS) domain. Subsequent phosphorylation of R-SMADs by the type I receptor and formation and translocation of R-SMAD-SMAD4 complex to the nucleus are critical steps for gene regulation [2, 8–10]. Activation of transcription is achieved by SMAD binding to the consensus DNA binding sequence (AGAC) termed SMAD binding element (SBE) [11, 12], in concert with co-activators and co-repressors. Of note, SMADs can promote chromatin remodeling and histone modification, which facilitates gene transcription by recruiting co-regulators to the promoters of genes of preference [13].

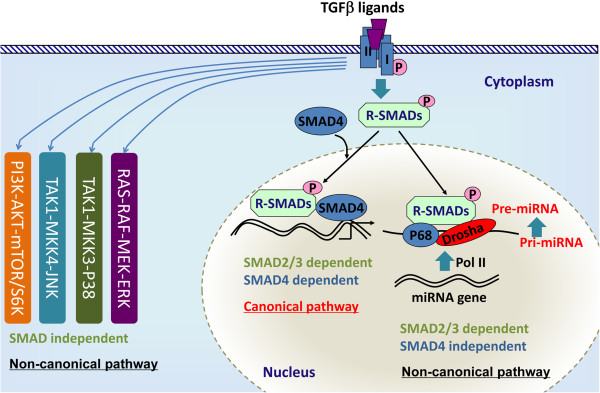

TGFβ signals through both SMAD-dependent (i.e., canonical) and SMAD-independent (i.e., non-canonical) pathways in a contextually dependent manner [2, 8, 14–16] (Figure 1). The non-canonical pathways serve to integrate signaling from other signaling cascades, resulting in a quantitative output in a given context. Davis and colleagues [17] have recently suggested the presence of microRNA (miRNA)-mediated non-canonical pathway, where TGFβ signaling promotes the biosynthesis of a subset of miRNAs via interactions between R-SMADs and a consensus RNA sequence of miRNAs within the DROSHA (drosha, ribonuclease type III) complex [17–19]. Thus, this type of non-canonical signaling requires R-SMADs but not SMAD4. Multiple regulatory layers including ligand traps (e.g., follistatin), inhibitory SMADs, and interactive pathways exist to determine the signaling output and precisely control TGFβ signaling activity [4, 8, 20–23]. For instance, the linker region of R-SMADs is subject to the phosphorylation modification by mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [24]. Therefore, the variable responses triggered by this growth factor superfamily and the complex signaling circuitries within a given cell population underscore the importance of a fine-tuned TGFβ signaling system at both the cellular and systemic levels.

Figure 1.

Canonical and non-canonical TGFβ signaling. In the canonical pathway, TGFβ ligands bind to serine/threonine kinase type II and type I receptors and phosphorylate R-SMADs, which form heteromeric complexes with SMAD4 and translocate into the nucleus to regulate gene transcription. The non-canonical pathway generally refers to the SMAD-independent pathway such as PI3K-AKT, ERK1/2, p38, and JNK pathways. Recent studies have identified an “R-SMAD-dependent but SMAD4-independent” non-canonical pathway that regulates miRNA maturation.

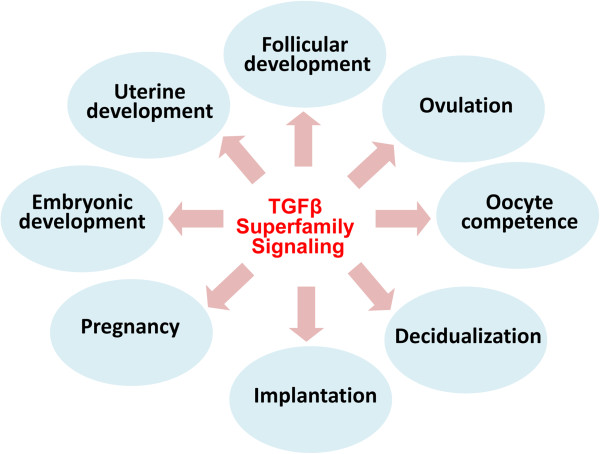

TGFβ superfamily signaling regulates female reproduction

TGFβ superfamily is evolutionarily conserved and plays fundamental roles in cell growth and differentiation. The signal transduction and biological functions of this signaling pathway have been extensively investigated [2, 4, 8, 9, 25]. TGFβ superfamily signaling is essential for female reproduction (Figure 2), and dysregulation of TGFβ signaling may cause catastrophic consequences, leading to reproductive diseases and cancers [26–33].

Figure 2.

Major functions of TGFβ superfamily signaling in the female reproduction. TGFβ superfamily signaling regulates a variety of reproductive processes including follicular development (e.g., TGFβs, GDF9, BMP15, activins, and AMH), ovulation (e.g., GDF9), oocyte competence (e.g., GDF9 and BMP15), decidualization (e.g., BMP2 and NODAL), implantation (e.g., ALK2-mediated signaling), pregnancy (e.g., BMPR2-mediated signaling), embryonic development (e.g., TGFβs, activins, follistatin, BMP2, and BMP4), and uterine development (TGFBR1-mediated signaling).

Recent studies have uncovered the roles of key receptors and intracellular SMADs of this pathway in female reproduction. Smad1 and Smad5 null mice are embryonically lethal, but Smad8 null mice are viable and fertile [34, 35]. SMAD1/5 and ALK3/6 act as tumor suppressors with functional redundancy in the ovary [27, 29]. Smad3Δex8 mice demonstrate impaired follicular growth and atresia, altered ovarian cell differentiation, and defective granulosa cell response to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) [36, 37]. We have shown that SMAD2 and SMAD3 are redundantly required to maintain normal fertility and ovarian function [38]. Disruption of Smad4 signaling in ovarian granulosa cells leads to premature luteinization [39]. However, oocyte-specific knockout of Smad4 causes minimal fertility defects in mice [40]. SMAD7 mediates TGFβ-induced apoptosis [41] and antagonizes key TGFβ signaling in ovarian granulosa cells [42], suggesting inhibitory SMADs are potentially novel regulators of ovarian function. Recent studies show that TGFBR1 is indispensable for female reproductive tract development [43, 44], while ALK2 and BMPR2 are required for uterine decidualization and/or pregnancy maintenance [45, 46].

TGFβ signaling in uterine development

The uterus develops from the Müllerian duct, which forms at embryonic day E11.75 in mice [47]. Uterine mesenchymal cells remain randomly oriented and undifferentiated until after birth. Between birth and postnatal day 3, circular and longitudinal myometrial layers are differentiated from the mesenchyme [48]. The uterus acquires basic layers and structures by postnatal day 15 [48, 49]. Maturation of the myometrium continues into adulthood. Mechanisms controlling myometrial development are poorly defined. Wingless-type MMTV integration site family (Wnt)7a null females demonstrate defects in reproductive tract formation, suggesting a critical role of Wnt/β catenin signaling in myometrial development [50–53].

Myometrial contractility is critical for successful pregnancy and labor. The myometrial cells transform from a quiescent to a contractile phenotype trigged by the decline of progesterone levels during late pregnancy. What has long puzzled scientists is how this transformation occurs during pregnancy, and how myometrial development and function are coordinately regulated. Uterine contraction is controlled by hormonal, cellular, and molecular signals [54–65]. Recent studies have discovered that miRNAs are key regulators of contraction-associated genes and suppressors including oxytocin receptor (Oxtr), cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox2), connexin 43 (Cx43), zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (Zeb1), and Zeb2 [65, 66]. However, signaling pathways that control the development of morphologically normal and functionally competent myometrium are poorly understood.

TGFβ signaling plays a pleiotropic role in fundamental cellular and developmental events [2, 3, 8]. Using a Tgfbr1 conditional knockout (cKO) mouse model created using anti-Müllerian hormone receptor type 2 (Amhr2)-Cre, we have shown that TGFβ signaling is essential for smooth muscle development in the female reproductive tract [43, 44]. The female mice develop a striking oviductal phenotype that includes a diverticulum. The Tgfbr1 cKO mice are infertile and embryos are unable to be transported to the uterus due to the presence of the physical barrier of oviductal diverticula [43]. Meanwhile, disrupted uterine smooth muscle formation is another prominent feature in these mice, which is associated with a developmental failure of the myometrium during early postnatal uterine development [44]. However, the expression of the majority of smooth muscle genes in the uterus of the conditional knockout mice does not significantly differ from that of controls, suggesting that the developmental abnormality might not be a direct result of intrinsic deficiency in smooth muscle cell differentiation. Our studies point to the contributions of reduced deposition of extracellular matrix proteins, derailed signaling of platelet-derived growth factors, and potentially altered migration of uterine cells during a critical time window of development [44]. The Tgfbr1 cKO mouse model can be further exploited to understand the pathogenesis of myometrium-associated diseases, such as adenomyosis that is present in these mice [44].

TGFβ signaling and uterine function

Pre-implantation embryonic development refers to a period from fertilization to blastocyst implantation, which requires coordinated expression of maternal and embryonic genes. The fertilized egg undergoes dynamic genetic programming and divisions to reach the blastocyst stage. The pluripotent inner cell mass of the blastocyst will develop into the embryonic proper, while the trophectoderm and the primitive endoderm form extra-embryonic tissues during development [67]. Preimplantation embryonic development largely depends on maternal proteins and transcripts before zygotic genome activation (ZGA), which initiates the expression of genes that are needed for continued development of the embryos. ZGA occurs at the two-cell stage in the mouse [68].

Blastocyst implantation is a complex event that is controlled by both intrinsic embryonic programs and extrinsic cues including hormonal and uterine signals. Implantation in the mouse can be divided into three phases: apposition, attachment, and penetration. Following attachment, uterine stromal cells extensively proliferate and differentiate into decidual cells (i.e., decidualization) [69]. The roles of steroid hormones, cytokines, growth factors, integrins, and angiogenic factors have been explored, and more recently, a number of novel genes/pathways underlying implantation have been identified. Several elegant reviews are available on these topics [70–72]. The important roles of embryonic TGFβ superfamily signaling in embryo development have been reviewed [3]. This article will focus on the role of maternal TGFβ signaling in implantation and embryonic development.

TGFBs1-3 are founding members of the TGFβ superfamily. The majority of currently available studies are confined to the identification of tissue/cell-specific expression of TGFBs and in vitro analysis of the ligand function. In the uterus, the in vivo role of TGFβ signaling remains elusive, partially because of the redundancy of the ligands [73, 74] and the lack of appropriate animal models as a result of the embryonic lethality in mice lacking TGFβ ligands. TGFB1 is involved in preimplantation development and yolk sac vasculogenesis/hematopoiesis [75]. To allow the Tgfb1 null mice survive to reproductive age, they were bred onto the severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) background [76]. Although the uterus of Tgfb1 mutant mice appears to be morphologically normal [76], embryos are arrested in the morula stage.

An in vitro model has been used to determine the effect of growth factors on preimplantation development, and the results showed that TGFB1 or epidermal growth factor (EGF) dramatically improves the inferior development of singly cultured embryos between eight-cell/morula and blastocyst stages. This study suggests that embryo and/or reproductive tract-derived growth factors are involved in the development of preimplantation embryos [77]. In vitro treatment of preimplantation stage embryos with TGFB1 increases total numbers of cells in expanded and hatching blastocysts [78]. Furthermore, TGFB1-promoted in vitro blastocyst outgrowth is blocked by an antibody directed to parathyroid hormone-related protein [79], which suggests the involvement of parathyroid hormone-related protein in mediating the effect of TGFB1 on blastocyst outgrowth. In addition, TGFB1 increases the in vitro expression of oncofetal fibronectin, an anchoring trophoblast marker, indicating a potential role of TGFβ in trophoblast adhesion during implantation [80]. TGFB1 also inhibits human trophoblast cell invasion, at least partially, by promoting the production of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) [81]. An elegant study showed that maternal TGFB1 can cross the placenta and rescue the developmental defects of Tgfb1 null embryos, leading to perinatal survival of these mice [82]. As further evidence, both maternal and fetal TGFB1 may act to maintain pregnancy [83].

TGFβ signaling and uterine diseases

Uterine fibroids

Leiomyoma, generally known as uterine fibroid, is a benign tumor arising from the myometrium (i.e., smooth muscle layers). Although leiomyoma is commonly benign, it could be the cause of fertility disorders and morbidity and mortality in women [84].

Increasing lines of evidence point to the involvement of TGFβ signaling in the development of leiomyoma. It has been shown that the expression of TGFBs and receptors is elevated in leiomyomata versus unaffected myometrium [85]. Among all the three TGFβ isoforms, TGFB3 seems to play a major role in leiomyoma development by promoting cell growth and fibrogenic process [86]. Tgfb3 transcript and protein levels are elevated in human leiomyoma cells, compared with myometrial cells in two-dimensional (2D) and 3D cultures [87–90]. In a 3D culture system, a higher level of TGFB3 and SMAD2/3 activation is present in the leiomyoma cells versus myometrial cells [87, 89]. However, it does not support that connective tissue growth factor 2 (CCN2/CTGF) is a major mediator of TGFβ action in leiomyoma tissues [91].

Although a link between overexpression of TGFBs and leiomyoma has been recognized, the precise mechanisms of TGFβ signaling in leiomyoma are largely unknown. It has been demonstrated that TGFB1-stimulated expression of fibromodulin may contribute to the fibrotic properties of leiomyoma [92]. Moreover, treatment of myometrial cells with TGFB3 promotes the expression of ECM components such as collagen 1A1 (COL1A1), fibronectin 1 (FN1), and versican, but reduces the expression of those associated with ECM degradation [88, 93]. Thus, TGFβ signaling induces molecular changes that facilitate leiomyoma formation. Consistent with the enhanced TGFβ signaling in the etiology of leiomyoma, a number of substances or drugs, such as genistein [94], relaxin [95], halofuginone [96], asoprisnil [97], gonadotropin-releasing hormone-analogs (GnRH-a), and tibolone [98] may influence leiomyoma development via affecting TGFβ signaling. For the therapeutic purpose, an ideal drug is one that only targets TGFβ signaling in the leiomyoma cells but not normal myometrial cells. In this vein, asoprisnil, a steroidal 11β-benzaldoxime-substituted selective progesterone receptor modulator (SPRM), targets TGFB3 and TGFBR2 in leiomyoma cells but not normal myometrial cells [97], providing a potentially effective treatment option for leiomyoma. The high levels of leiomyoma-secreted TGFBs, in turn, may compromise uterine function of the patients. For example, by producing excessive amount of TGFB3, leiomyoma antagonizes decidualization mediated by BMP2 [99].

Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia often occurs in pregnant women after the 20th week of gestation, characterized by hypertension and proteinuria. The causes of preeclampsia are complex and beyond the scope of this review. It has been shown that plasma TGFB1 [100–104] and TGFB2 [105] levels are elevated in patients with preeclampsia. Experimental evidence also suggests that failure to downregulate the expression of TGFB3 during early gestation may cause trophoblast hypo-invasion and preeclampsia [106]. Interestingly, the levels of soluble endoglin, a transmembrane TGFβ co-receptor, are elevated in sera of women with preeclampsia, which may be associated with vascular complications and hypertension in these patients [107, 108]. Based on these findings, TGFB proteins may serve as potential biomarkers for preeclampsia [105]. It is thus plausible that optimal TGFβ signaling activity is required to keep preeclampsia in check by maintaining normal trophoblast invasion during implantation and placentation. However, another study showed that TGFBs1-3 are not expressed in villous trophoblasts, and TGFB1 and TGFB3 are not expressed in the extravillous trophoblast either. The expression of TGFBs1-3 in the placenta is not altered in patients with preeclampsia [109]. Moreover, there are also reports indicating that concentrations of TGFB1 in serum are indistinguishable between patients with preeclampsia and normal controls [110–112]. In addition, the levels of activin A and inhibin A, but not inhibin B, are increased in patients with preeclampsia [113–116]. Thus, the role of TGFβ signaling in the pathophysiological events of preeclampsia awaits further elucidation.

Intrauterine growth restriction

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), also called fetal growth restriction (FGR), refers to a complication of fetal growth during pregnancy. The estimated weight of the fetus with IUGR is often less than 90% of other fetuses at the same stage of pregnancy [117]. Circumstantial evidence indicates that TGFβ signaling is involved in the development of IUGR. Serum levels of TGFB1 in the IUGR fetus are lower [118]. TGFB2 is required for normal embryo growth, as supported by the fact that Tgfb2 mutant fetuses weigh less than littermate controls [119]. Soluble endoglin levels are elevated in IUGR pregnancies [108], although it is debatable [120]. It has been shown that the higher expression of endoglin in IUGR pregnancies may be caused by placental hypoxia involving TGFB3 [121]. Mouse models for IUGR are valuable to study the mechanism of this pathological condition, which may have devastating effects on the pregnancy and newborns. Notably, Nodal knockout mice show diminished decidua basalis due to reduced proliferation and enhanced apoptosis as well as defects in placental development, resulting in IUGR and preterm fetal loss [122]. Conditional ablation of Bmpr2 in the uterus causes defects in decidualization, trophoblast invasion, and vascularization, which are causes of IUGR in the pregnant females [46].

Endometrial hyperplasia

Endometrial hyperplasia is a pathological condition where endometrial cells undergo excessive proliferation [123]. Categories of endometrial hyperplasia include simple hyperplasia, simple atypical hyperplasia, complex hyperplasia, and complex atypical hyperplasia [124]. Endometrial hyperplasia is recognized as a premalignant lesion of endometrial carcinoma [125] and a potential cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and fertility disorders. The high prevalence of endometrial carcinoma is associated with atypical hyperplasia in women [126–128]. It has been reported that up to 29% of untreated complex atypical hyperplasia progresses to carcinoma [124]. Endometrial hyperplasia is generally caused by excessive or chronic estrogen stimulation that is unopposed by progesterone, as in patients with chronic anovulation and polycystic ovary syndrome. Although progestin treatment is commonly effective for this disease [129], approximately 30% of patients with complex hyperplasia are progestin resistant [130]. Genetic alterations including mutations of Pten tumor suppressor have been shown to be associated with endometrial hyperplasia [131, 132]. Elegant work has shown that inactivation of TGFβ signaling and loss of growth inhibition are associated with human endometrial carcinogenesis [133, 134]. The role of TGFβ signaling in endometrial cancer has been reviewed and will not be covered in this article [135]. Our recent study shows that loss of TGFBR1 in the mouse uterus using Amhr2-Cre enhances epithelial cell proliferation. The aberration culminates in endometrial hyperplasia. Further studies have uncovered potential TGFBR1-mediated paracrine signaling in the regulation of uterine epithelial cell proliferation, and provided genetic evidence supporting the role of uterine epithelial cell proliferation in the pathogenesis of endometrial hyperplasia [136]. Further elucidating the role and the underlying mechanisms of TGFβ signaling in the pathogenesis of endometrial hyperplasia and/or cancer will benefit the design of new therapies.

Conclusions and future directions

A precisely controlled endogenous TGFβ signaling system is of critical importance for the development and function of female reproductive tract. Mouse genetics has proven to be a powerful tool to address many of the fundamental questions posed in the field of TGFβ and reproduction. Conditional knockout approaches have been utilized over the last two decades to decipher the reproductive function of TGFβ superfamily in female reproduction. These studies are at an exciting stage and are advancing at a rapid pace. The functional role of TGFβ signaling in the uterus is beginning to be unveiled. We anticipate that the genetic approach will continue to have large impacts and lead to new breakthroughs in this field. However, understanding how the hormonal, cellular, and molecular signals induce a specific biological response and functional outcome in the context of the uterine microenvironment in vivo represents a challenging task. It remains unclear how specific or integrated signals act on the chromatin to shape the epigenetic landscape in physiological and/or pathological conditions of the uterus. Therefore, the interaction between TGFβ signaling and other regulatory pathways (e.g., small RNA pathways) and potential epigenetic mechanisms underlying specific reproductive processes and/or diseases in the uterus need to be clarified. This knowledge will help to design new treatment options for uterine diseases and fertility disorders.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the great support and collaboration from colleagues at Texas A&M University, especially Drs. Kayla Bayless, Gregory Johnson, Robert Burghardt, and Fuller Bazer. Several trainees (Yang Gao, Samantha Duran, Chao Wang, and Haixia Wen) in the author’s lab have contributed to the related work. Yang Gao is also acknowledged for the assistance with literature review. Research in this area is supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R21HD073756 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and the Ralph E. Powe Junior Faculty Enhancement Awards from Oak Ridge Associated Universities.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Author’s contributions

The author reviewed and analyzed the literature and wrote this paper.

References

- 1.Massague J. Receptors for the TGF-beta family. Cell. 1992;69:1067–1070. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90627-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massague J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang H, Brown CW, Matzuk MM. Genetic analysis of the mammalian transforming growth factor-β superfamily. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:787–823. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmierer B, Hill CS. TGFbeta-SMAD signal transduction: molecular specificity and functional flexibility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:970–982. doi: 10.1038/nrm2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukazaki T, Chiang TA, Davison AF, Attisano L, Wrana JL. SARA, a FYVE domain protein that recruits Smad2 to the TGF beta receptor. Cell. 1998;95:779–791. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imamura T, Takase M, Nishihara A, Oeda E, Hanai J, Kawabata M, Miyazono K. Smad6 inhibits signalling by the TGF-beta superfamily. Nature. 1997;389:622–626. doi: 10.1038/39355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakao A, Afrakhte M, Moren A, Nakayama T, Christian JL, Heuchel R, Itoh S, Kawabata M, Heldin NE, Heldin CH, ten Dijke P. Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 1997;389:631–635. doi: 10.1038/39369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massague J. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massague J. TGFbeta signalling in context. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:616–630. doi: 10.1038/nrm3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhurst RJ, Hata A. Targeting the TGFbeta signalling pathway in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:790–811. doi: 10.1038/nrd3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonk LJC, Itoh S, Heldin CH, ten Dijke P, Kruijer W. Identification and functional characterization of a Smad binding element (SBE) in the JunB promoter that acts as a transforming growth factor-beta, activin, and bone morphogenetic protein-inducible enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21145–21152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y, Wang YF, Jayaraman L, Yang H, Massague J, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of a Smad MH1 domain bound to DNA: insights on DNA binding in TGF-beta signaling. Cell. 1998;94:585–594. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross S, Cheung E, Petrakis TG, Howell M, Kraus WL, Hill CS. Smads orchestrate specific histone modifications and chromatin remodeling to activate transcription. Embo J. 2006;25:4490–4502. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moustakas A, Heldin CH. Non-Smad TGF-beta signals. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3573–3584. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang YE. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:128–139. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo X, Wang XF. Signaling cross-talk between TGF-beta/BMP and other pathways. Cell Res. 2009;19:71–88. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis BN, Hilyard AC, Lagna G, Hata A. SMAD proteins control DROSHA-mediated microRNA maturation. Nature. 2008;454:56–61. doi: 10.1038/nature07086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis BN, Hilyard AC, Nguyen PH, Lagna G, Hata A. Smad proteins bind a conserved RNA sequence to promote microRNA maturation by Drosha. Mol Cell. 2010;39:373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis-Dusenbery BN, Hata A. Smad-mediated miRNA processing: A critical role for a conserved RNA sequence. RNA Biol. 2011;8:71–76. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.1.14299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attisano L, Wrana JL. Signal transduction by the TGF-beta superfamily. Science. 2002;296:1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan X, Liu Z, Chen Y. Regulation of TGF-beta signaling by Smad7. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2009;41:263–272. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan XH, Chen YG. Smad7: not only a regulator, but also a cross-talk mediator of TGF-beta signalling. Biochem J. 2011;434:1–10. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pera EM, Ikeda A, Eivers E, De Robertis EM. Integration of IGF, FGF, and anti-BMP signals via Smad1 phosphorylation in neural induction. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3023–3028. doi: 10.1101/gad.1153603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakefield LM, Hill CS. Beyond TGFbeta: roles of other TGFbeta superfamily members in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:328–341. doi: 10.1038/nrc3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, Graff JM, O’Connor AE, Loveland KL, Matzuk MM. SMAD3 regulates gonadal tumorigenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2472–2486. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pangas SA, Li X, Umans L, Zwijsen A, Huylebroeck D, Gutierrez C, Wang D, Martin JF, Jamin SP, Behringer RR, Robertson EJ, Matzuk MM. Conditional deletion of Smad1 and Smad5 in somatic cells of male and female gonads leads to metastatic tumor development in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:248–257. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01404-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matzuk MM, Finegold MJ, Su JG, Hsueh AJ, Bradley A. Alpha-inhibin is a tumour-suppressor gene with gonadal specificity in mice. Nature. 1992;360:313–319. doi: 10.1038/360313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edson MA, Nalam RL, Clementi C, Franco HL, Demayo FJ, Lyons KM, Pangas SA, Matzuk MM. Granulosa cell-expressed BMPR1A and BMPR1B have unique functions in regulating fertility but act redundantly to suppress ovarian tumor development. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1251–1266. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Middlebrook BS, Eldin K, Li X, Shivasankaran S, Pangas SA. Smad1-Smad5 ovarian conditional knockout mice develop a disease profile similar to the juvenile form of human granulosa cell tumors. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5208–5217. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neptune ER, Frischmeyer PA, Arking DE, Myers L, Bunton TE, Gayraud B, Ramirez F, Sakai LY, Dietz HC. Dysregulation of TGF-beta activation contributes to pathogenesis in Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:407–411. doi: 10.1038/ng1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang XR, Chung AC, Wang XJ, Lai KN, Lan HY. Mice overexpressing latent TGF-beta1 are protected against renal fibrosis in obstructive kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F118–F127. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00021.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massague J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnold SJ, Maretto S, Islam A, Bikoff EK, Robertson EJ. Dose-dependent Smad1, Smad5 and Smad8 signaling in the early mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2006;296:104–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Z, Wang DG, Ihida-Stansbury K, Jones PL, Martin JF. Defective pulmonary vascular remodeling in Smad8 mutant mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2791–2801. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomic D, Miller KP, Kenny HA, Woodruff TK, Hoyer P, Flaws JA. Ovarian follicle development requires Smad3. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2224–2240. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong X, McGee EA. Smad3 is required for normal follicular follicle-stimulating hormone responsiveness in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:730–738. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.070086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Q, Pangas SA, Jorgez CJ, Graff JM, Weinstein M, Matzuk MM. Redundant roles of SMAD2 and SMAD3 in ovarian granulosa cells in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:7001–7011. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00732-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pangas SA, Li X, Robertson EJ, Matzuk MM. Premature luteinization and cumulus cell defects in ovarian-specific Smad4 knockout mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1406–1422. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X, Tripurani SK, James R, Pangas SA. Minimal fertility defects in mice deficient in oocyte-expressed Smad4. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:1–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.094375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quezada M, Wang J, Hoang V, McGee EA. Smad7 is a transforming growth factor-beta-inducible mediator of apoptosis in granulosa cells. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1452–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao Y, Wen H, Wang C, Li Q. SMAD7 antagonizes key TGFbeta superfamily signaling in mouse granulosa cells in vitro. Reproduction. 2013;146:1–11. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Q, Agno JE, Edson MA, Nagaraja AK, Nagashima T, Matzuk MM. Transforming growth factor beta receptor type 1 is essential for female reproductive tract integrity and function. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Y, Bayless KJ, Li Q. TGFBR1 is required for mouse myometrial development. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:380–394. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clementi C, Tripurani SK, Large MJ, Edson MA, Creighton CJ, Hawkins SM, Kovanci E, Kaartinen V, Lydon JP, Pangas SA, DeMayo FJ, Matzuk MM. Activin-like kinase 2 functions in peri-implantation uterine signaling in mice and humans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagashima T, Li Q, Clementi C, Lydon JP, Demayo FJ, Matzuk MM. BMPR2 is required for postimplantation uterine function and pregnancy maintenance. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2539–2550. doi: 10.1172/JCI65710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orvis GD, Behringer RR. Cellular mechanisms of Mullerian duct formation in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2007;306:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brody JR, Cunha GR. Histologic, morphometric, and immunocytochemical analysis of myometrial development in rats and mice: I. Normal development. Am J Anat. 1989;186:1–20. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001860102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brody JR, Cunha GR. Histologic, morphometric, and immunocytochemical analysis of myometrial development in rats and mice: II. Effects of DES on development. Am J Anat. 1989;186:21–42. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001860103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller C, Sassoon DA. Wnt-7a maintains appropriate uterine patterning during the development of the mouse female reproductive tract. Development. 1998;125:3201–3211. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.16.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Jia Y, Franken P, Smits R, Ewing PC, Lydon JP, Demayo FJ, Burger CW, Anton Grootegoed J, Fodde R, Blok LJ. Loss of APC function in mesenchymal cells surrounding the Mullerian duct leads to myometrial defects in adult mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;341:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arango NA, Szotek PP, Manganaro TF, Oliva E, Donahoe PK, Teixeira J. Conditional deletion of beta-catenin in the mesenchyme of the developing mouse uterus results in a switch to adipogenesis in the myometrium. Dev Biol. 2005;288:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parr BA, McMahon AP. Sexually dimorphic development of the mammalian reproductive tract requires Wnt-7a. Nature. 1998;395:707–710. doi: 10.1038/27221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mesiano S, Chan EC, Fitter JT, Kwek K, Yeo G, Smith R. Progesterone withdrawal and estrogen activation in human parturition are coordinated by progesterone receptor A expression in the myometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2924–2930. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Condon JC, Jeyasuria P, Faust JM, Wilson JW, Mendelson CR. A decline in the levels of progesterone receptor coactivators in the pregnant uterus at term may antagonize progesterone receptor function and contribute to the initiation of parturition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9518–9523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633616100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brainard AM, Miller AJ, Martens JR, England SK. Maxi-K channels localize to caveolae in human myometrium: a role for an actin-channel-caveolin complex in the regulation of myometrial smooth muscle K + current. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C49–C57. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00399.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brainard AM, Korovkina VP, England SK. Potassium channels and uterine function. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pierce SL, Kresowik JD, Lamping KG, England SK. Overexpression of SK3 channels dampens uterine contractility to prevent preterm labor in mice. Bio Reprod. 2008;78:1058–1063. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pierce SL, England SK. SK3 channel expression during pregnancy is regulated through estrogen and Sp factor-mediated transcriptional control of the KCNN3 gene. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E640–E646. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00063.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yallampalli C, Dong YL. Estradiol-17beta inhibits nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-II and stimulates NOS-III gene expression in the rat uterus. Bio Reprod. 2000;63:34–41. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yallampalli C, Garfield RE, Byam-Smith M. Nitric oxide inhibits uterine contractility during pregnancy but not during delivery. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1899–1902. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.4.8404632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yallampalli C, Izumi H, Byam-Smith M, Garfield RE. An L-arginine-nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate system exists in the uterus and inhibits contractility during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dong YL, Yallampalli C. Interaction between nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 pathways in pregnant rat uteri. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:E471–E476. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.270.3.E471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tong D, Lu X, Wang HX, Plante I, Lui E, Laird DW, Bai D, Kidder GM. A dominant loss-of-function GJA1 (Cx43) mutant impairs parturition in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:1099–1106. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.071969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Renthal NE, Chen CC, Williams KC, Gerard RD, Prange-Kiel J, Mendelson CR. miR-200 family and targets, ZEB1 and ZEB2, modulate uterine quiescence and contractility during pregnancy and labor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20828–20833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008301107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Williams KC, Renthal NE, Gerard RD, Mendelson CR. The microRNA (miR)-199a/214 cluster mediates opposing effects of progesterone and estrogen on uterine contractility during pregnancy and labor. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:1857–1867. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cockburn K, Rossant J. Making the blastocyst: lessons from the mouse. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:995–1003. doi: 10.1172/JCI41229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Flach G, Johnson MH, Braude PR, Taylor RA, Bolton VN. The transition from maternal to embryonic control in the 2-cell mouse embryo. Embo J. 1982;1:681–686. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salamonsen LA, Dimitriadis E, Jones RL, Nie G. Complex regulation of decidualization: a role for cytokines and proteases--a review. Placenta. 2003;24(Suppl A):S76–S85. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang H, Dey SK. Roadmap to embryo implantation: clues from mouse models. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:185–199. doi: 10.1038/nrg1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cha J, Sun X, Dey SK. Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat Med. 2012;18:1754–1767. doi: 10.1038/nm.3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guzelogiu-Kayisli Z, Kayisli UA, Taylor HS. The role of growth factors and cytokines during implantation: endocrine and paracrine interactions. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27:62–79. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1108011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Memon MA, Anway MD, Covert TR, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF beta 1, TGF beta 2 and TGF beta 3) null-mutant phenotypes in embryonic gonadal development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;294:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mu Z, Yang Z, Yu D, Zhao Z, Munger JS. TGFbeta1 and TGFbeta3 are partially redundant effectors in brain vascular morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2008;125:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kallapur S, Ormsby I, Doetschman T. Strain dependency of TGFbeta1 function during embryogenesis. Mol Reprod Dev. 1999;52:341–349. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199904)52:4<341::AID-MRD2>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ingman WV, Robker RL, Woittiez K, Robertson SA. Null mutation in transforming growth factor beta1 disrupts ovarian function and causes oocyte incompetence and early embryo arrest. Endocrinology. 2006;147:835–845. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Paria BC, Dey SK. Preimplantation embryo development in vitro - cooperative interactions among embryos and role of growth-factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4756–4760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lim J, Bongso A, Ratnam S. Mitogenic and cytogenetic evaluation of transforming growth-factor-beta on murine preimplantation embryonic-development in-vitro. Mol Reprod Dev. 1993;36:482–487. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080360412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nowak RA, Haimovici F, Biggers JD, Erbach GT. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates mouse blastocyst outgrowth through a mechanism involving parathyroid hormone-related protein. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:85–93. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Feinberg RF, Kliman HJ, Wang CL. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates trophoblast oncofetal fibronectin synthesis in vitro: implications for trophoblast implantation in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:1241–1248. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.5.8175984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Graham CH, Connelly I, Macdougall JR, Kerbel RS, Stetlerstevenson WG, Lala PK. Resistance of malignant trophoblast cells to both the antiproliferative and anti-invasive effects of transforming growth-factor-beta. Exp Cell Res. 1994;214:93–99. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Letterio JJ, Geiser AG, Kulkarni AB, Roche NS, Sporn MB, Roberts AB. Maternal rescue of transforming growth factor-beta 1 null mice. Science. 1994;264:1936–1938. doi: 10.1126/science.8009224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McLennan IS, Koishi K. Fetal and maternal transforming growth factor-beta 1 may combine to maintain pregnancy in mice. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1614–1618. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.026179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Akinyemi BO, Adewoye BR, Fakoya TA. Uterine fibroid: a review. Niger J Med. 2004;13:318–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dou Q, Zhao Y, Tarnuzzer RW, Rong H, Williams RS, Schultz GS, Chegini N. Suppression of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF beta) and TGF beta receptor messenger ribonucleic acid and protein expression in leiomyomata in women receiving gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3222–3230. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.9.8784073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arici A, Sozen I. Transforming growth factor-beta3 is expressed at high levels in leiomyoma where it stimulates fibronectin expression and cell proliferation. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:1006–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Levy G, Malik M, Britten J, Gilden M, Segars J, Catherino WH. Liarozole inhibits transforming growth factor-beta3-mediated extracellular matrix formation in human three-dimensional leiomyoma cultures. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Joseph DS, Malik M, Nurudeen S, Catherino WH. Myometrial cells undergo fibrotic transformation under the influence of transforming growth factor beta-3. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:1500–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Malik M, Catherino WH. Development and validation of a three-dimensional in vitro model for uterine leiomyoma and patient-matched myometrium. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1287–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Malik M, Catherino WH. Novel method to characterize primary cultures of leiomyoma and myometrium with the use of confirmatory biomarker gene arrays. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:1166–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.08.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Luo X, Ding L, Chegini N. CCNs, fibulin-1C and S100A4 expression in leiomyoma and myometrium: inverse association with TGF-beta and regulation by TGF-beta in leiomyoma and myometrial smooth muscle cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006;12:245–256. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Levens E, Luo X, Ding L, Williams RS, Chegini N. Fibromodulin is expressed in leiomyoma and myometrium and regulated by gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue therapy and TGF-beta through Smad and MAPK-mediated signalling. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11:489–494. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Norian JM, Malik M, Parker CY, Joseph D, Leppert PC, Segars JH, Catherino WH. Transforming growth factor beta3 regulates the versican variants in the extracellular matrix-rich uterine leiomyomas. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:1153–1164. doi: 10.1177/1933719109343310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Di X, Andrews DM, Tucker CJ, Yu L, Moore AB, Zheng X, Castro L, Hermon T, Xiao H, Dixon D. A high concentration of genistein down-regulates activin A, Smad3 and other TGF-beta pathway genes in human uterine leiomyoma cells. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:281–292. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.4.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li Z, Burzawa JK, Troung A, Feng S, Agoulnik IU, Tong X, Anderson ML, Kovanci E, Rajkovic A, Agoulnik AI. Relaxin signaling in uterine fibroids. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1160:374–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Grudzien MM, Low PS, Manning PC, Arredondo M, Belton RJ, Jr, Nowak RA. The antifibrotic drug halofuginone inhibits proliferation and collagen production by human leiomyoma and myometrial smooth muscle cells. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:1290–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ohara N, Morikawa A, Chen W, Wang J, DeManno DA, Chwalisz K, Maruo T. Comparative effects of SPRM asoprisnil (J867) on proliferation, apoptosis, and the expression of growth factors in cultured uterine leiomyoma cells and normal myometrial cells. Reprod Sci. 2007;14:20–27. doi: 10.1177/1933719107311464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.De Falco M, Staibano S, D’Armiento FP, Mascolo M, Salvatore G, Busiello A, Carbone IF, Pollio F, Di Lieto A. Preoperative treatment of uterine leiomyomas: Clinical findings and expression of transforming growth factor-beta 3 and connective tissue growth factor. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sinclair DC, Mastroyannis A, Taylor HS. Leiomyoma simultaneously impair endometrial BMP-2-mediated decidualization and anticoagulant expression through secretion of TGF-beta 3. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2011;96:412–421. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Peracoli MT, Menegon FT, Borges VT, de Araujo Costa RA, Thomazini-Santos IA, Peracoli JC. Platelet aggregation and TGF-beta(1) plasma levels in pregnant women with preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol. 2008;79:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Djurovic S, Schjetlein R, Wisloff F, Haugen G, Husby H, Berg K. Plasma concentrations of Lp(a) lipoprotein and TGF-beta1 are altered in preeclampsia. Clin Genet. 1997;52:371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1997.tb04356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Enquobahrie DA, Williams MA, Qiu C, Woelk GB, Mahomed K. Maternal plasma transforming growth factor-beta1 concentrations in preeclamptic and normotensive pregnant Zimbabwean women. J Matern Fetal Neona. 2005;17:343–348. doi: 10.1080/14767050500132450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang XJ, Zhou ZY, Xu YJ. Changes of plasma uPA and TGF-beta1 in patients with preeclampsia. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2010;41:118–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Feizollahzadeh S, Taheripanah R, Khani M, Farokhi B, Amani D. Promoter region polymorphisms in the transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGFbeta1) gene and serum TGFbeta1 concentration in preeclamptic and control Iranian women. J Reprod Immunol. 2012;94:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shaarawy M, El Meleigy M, Rasheed K. Maternal serum transforming growth factor beta-2 in preeclampsia and eclampsia, a potential biomarker for the assessment of disease severity and fetal outcome. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2001;8:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Caniggia I, Grisaru-Gravnosky S, Kuliszewsky M, Post M, Lye SJ. Inhibition of TGF-beta 3 restores the invasive capability of extravillous trophoblasts in preeclamptic pregnancies. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1641–1650. doi: 10.1172/JCI6380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, Bdolah Y, Lim KH, Yuan HT, Libermann TA, Stillman IE, Roberts D, D’Amore PA, Epstein FH, Sellke FW, Romero R, Sukhatme VP, Letarte M, Karumanchi SA. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat Med. 2006;12:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Stepan H, Kramer T, Faber R. Maternal plasma concentrations of soluble endoglin in pregnancies with intrauterine growth restriction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2831–2834. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lyall F, Simpson H, Bulmer JN, Barber A, Robson SC. Transforming growth factor-beta expression in human placenta and placental bed in third trimester normal pregnancy, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1827–1838. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63029-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Szarka A, Rigo J, Jr, Lazar L, Beko G, Molvarec A. Circulating cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia determined by multiplex suspension array. BMC Immunol. 2010;11:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Perucci LO, Gomes KB, Freitas LG, Godoi LC, Alpoim PN, Pinheiro MB, Miranda AS, Teixeira AL, Dusse LM, Sousa LP. Soluble endoglin, transforming growth factor-Beta 1 and soluble tumor necrosis factor alpha receptors in different clinical manifestations of preeclampsia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Huber A, Hefler L, Tempfer C, Zeisler H, Lebrecht A, Husslein P. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 serum levels in pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:168–171. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bersinger NA, Smarason AK, Muttukrishna S, Groome NP, Redman CW. Women with preeclampsia have increased serum levels of pregnancy-associated plasma protein a (PAPP-A), inhibin A, activin A, and soluble E-selectin. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2003;22:45–55. doi: 10.1081/PRG-120016794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Silver HM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, Reis FM, Diblasio AM, Petraglia F, Canick JA. Mechanism of increased maternal serum total activin A and inhibin A in preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2002;9:308–312. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(02)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yair D, Eshed-Englender T, Kupferminc MJ, Geva E, Frenkel J, Sherman D. Serum levels of inhibin B, unlike inhibin A and activin A, are not altered in women with preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2001;45:180–187. doi: 10.1111/j.8755-8920.2001.450310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Laivuori H, Kaaja R, Turpeinen U, Stenman UH, Ylikorkala O. Serum activin A and inhibin A elevated in pre-eclampsia: no relation to insulin sensitivity. BJOG. 1999;106:1298–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Figueras F, Gardosi J. Intrauterine growth restriction: new concepts in antenatal surveillance, diagnosis, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:288–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ostlund E, Tally M, Fried G. Transforming growth factor-beta1 in fetal serum correlates with insulin-like growth factor-I and fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:567–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sanford LP, Ormsby I, GittenbergerdeGroot AC, Sariola H, Friedman R, Boivin GP, Cardell EL, Doetschman T. TGF beta 2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects that are nonoverlapping with other TGF beta knockout phenotypes. Development. 1997;124:2659–2670. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jeyabalan A, McGonigal S, Gilmour C, Hubel CA, Rajakumar A. Circulating and placental endoglin concentrations in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth restriction and preeclampsia. Placenta. 2008;29:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yinon Y, Nevo O, Xu J, Many A, Rolfo A, Todros T, Post M, Caniggia I. Severe intrauterine growth restriction pregnancies have increased placental endoglin levels: hypoxic regulation via transforming growth factor-beta 3. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:77–85. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Park CB, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP, Dufort D. NODAL in the uterus is necessary for proper placental development and maintenance of pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:194. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.098277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mills AM, Longacre TA. Endometrial hyperplasia. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2010;27:199–214. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kurman RJ, Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403–412. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850715)56:2<403::aid-cncr2820560233>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Montgomery BE, Daum GS, Dunton CJ. Endometrial hyperplasia: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:368–378. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200405000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Shutter J, Wright TC. Prevalence of underlying adenocarcinoma in women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005;24:313–318. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000164598.26969.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lacey JV, Chia VM. Endometrial hyperplasia and the risk of progression to carcinoma. Maturitas. 2009;63:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hahn HS, Chun YK, Kwon YI, Kim TJ, Lee KH, Shim JU, Mok JE, Lim KT. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma following hysterectomy for atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;150:80–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gambrell RD. Progestogens in estrogen-replacement therapy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1995;38:890–901. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199538040-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Reed SD, Voigt LF, Newton KM, Garcia RH, Allison HK, Epplein M, Jordan D, Swisher E, Weiss NS. Progestin therapy of complex endometrial hyperplasia with and without atypia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:655–662. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318198a10a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Stambolic V, Tsao MS, Macpherson D, Suzuki A, Chapman WR, Mak TW. High incidence of breast and endometrial neoplasia resembling human Cowden syndrome in pten(+/−) mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3605–3611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Milam MR, Soliman PT, Chung LH, Schmeler KM, Bassett RL, Broaddus RR, Lu KH. Loss of phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 and phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin are associated with progesterone refractory endometrial hyperplasia. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:146–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Parekh TV, Gama P, Wen X, Demopoulos R, Munger JS, Carcangiu ML, Reiss M, Gold LI. Transforming growth factor beta signaling is disabled early in human endometrial carcinogenesis concomitant with loss of growth inhibition. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2778–2790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lecanda J, Parekh TV, Gama P, Lin K, Liarski V, Uretsky S, Mittal K, Gold LI. Transforming growth factor-beta, estrogen, and progesterone converge on the regulation of p27Kip1 in the normal and malignant endometrium. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1007–1018. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Piestrzeniewicz-Ulanska D, McGuinness D, Yeaman G. TGF-β Signaling in Endometrial Cancer. In: Jakowlew S, editor. Transforming Growth Factor-β in Cancer Therapy, Volume II. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2008. pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Gao Y, Li S, Li Q. Uterine epithelial cell proliferation and endometrial hyperplasia: evidence from a mouse model. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:776–786. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gau033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]