Abstract

Biofilms are surface-associated conglomerates of bacteria that are highly resistant to antibiotics. These bacterial communities can cause chronic infections in humans by colonizing, for example, medical implants, heart valves, or lungs. Staphylococcus aureus, a notorious human pathogen, causes some of the most common biofilm-related infections. Despite the clinical importance of S. aureus biofilms, it remains mostly unknown how physical effects, in particular flow, and surface structure influence biofilm dynamics. Here we use model microfluidic systems to investigate how environmental factors, such as surface geometry, surface chemistry, and fluid flow affect biofilm development in S. aureus. We discovered that S. aureus rapidly forms flow-induced, filamentous biofilm streamers, and furthermore if surfaces are coated with human blood plasma, streamers appear within minutes and clog the channels more rapidly than if the channels are uncoated. To understand how biofilm streamer filaments reorient in flows with curved streamlines to bridge the distances between corners, we developed a mathematical model based on resistive force theory of slender filaments. Understanding physical aspects of biofilm formation in S. aureus may lead to new approaches for interrupting biofilm formation of this pathogen.

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a human pathogen notorious for causing hospital-acquired infections as well as fatal infections that occur outside of health care settings (1-3). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), in particular, is a major concern due to its potent virulence coupled with resistance to many antibiotics (4-6). MRSA is the most widespread cause of hospital-associated infections in the United States and Europe with a high mortality rate (7-10). S. aureus and MRSA cause a variety of infections ranging from minor skin and soft tissue infections to serious illnesses such as infections of indwelling medical devices, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, sepsis, and toxic shock syndrome (11).

S. aureus infections that are associated with abiotic materials, such as intravenous catheters and implants, are of primary concern because S. aureus colonizes such medical devices and forms biofilms (12-17). Biofilms are surface-associated three-dimensional conglomerates of bacteria that are enclosed by self-produced extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) (18-20). Once biofilms have developed, their removal is challenging because, compared to planktonic organisms, cells in biofilms display enhanced resistance to antimicrobial treatments and host immune defenses (21-28). Consequently, biofilms are often responsible for chronic infections (29), leading to high morbidity and significant healthcare costs (30, 31). Although biofilm-associated infections have spurred intense research efforts to understand biofilm formation by S. aureus (32-34), how physical aspects of the microenvironments of medical devices impinge on biofilm dynamics remain poorly understood.

The microenvironment affecting biofilm formation on indwelling medical devices can be characterized by complex local geometries, mechanical shear forces due to flows, the local chemical milieu and surface chemistry. Typically, inserted medical devices that come into contact with human blood are coated immediately with blood plasma proteins. Plasma proteins are readily adsorbed on abiotic surfaces (35, 36), and thus, they generate a unique local surface chemistry. Previous studies show that S. aureus attachment to surfaces is enhanced by adsorbed blood plasma proteins, such as the matrix proteins fibrinogen and fibronectin (37, 38). S. aureus cell surfaces are decorated with components that recognize adhesive matrix proteins and mediate binding to the molecules. These components include fibronectin-binding proteins A and B (FnBpA and FnBpB) and clumping factors A and B (ClfA and ClfB) (39). However, it is unclear how these components function under realistic physical conditions that include fluid motion, the associated flow regimes and surface geometries. For example, previous studies of the role of these components in S. aureus biofilms primarily considered biofilm development on smooth surfaces with no flow or constant flow of nutrient-containing medium across the biofilm (40-42). Recent reports have demonstrated that, in the presence of flow and complex surface geometries, biofilms of a bacterial pathogen, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, deform into flexible three-dimensional filaments, known as “streamers” (43-45), which connect the gaps between corners (46, 47), causing clogging in flow systems (48). Whether and how rapidly S. aureus can form biofilm streamers and how factors related to surface chemistry affect S. aureus biofilms are unknown.

To study S. aureus biofilm formation in physical environments that mimic in vivo conditions, we used model microfluidic systems that include curvy channels, as well as networks of multiple channels. The wall shear stresses that we used range from ∼0.02 Pa to ∼1 Pa, which are comparable to physiological wall shear stresses present in capillaries, venules, or catheters (between 0.02 Pa to 4 Pa) (49, 50). We examined several types of S. aureus strains, which differed in their quorum sensing system. For S. aureus, the quorum sensing system is also known as the accessory gene regulator (agr) system that regulates biofilm development and the expression of virulence factors (51-53). Natural isolates of S. aureus can be grouped into four different agr classes, which correlate with different types of infection (54, 55). We generated a realistic surface chemistry in our model microfluidic channels by coating the channels with human blood plasma. We discovered that the blood plasma triggered especially rapid cell attachment to the channels, resulting in the formation of biofilm streamers within minutes. The streamers led to clogging dynamics that are considerably more rapid than for other bacteria, such as P. aeruginosa (48). To understand how streamers initiate and bridge the gaps between corners, we modeled elastic filaments in flows with curved streamlines, and qualitatively compare this model with our experiments.

2. Results and Discussions

2.1. Rapid biofilm streamer formation of S. aureus

In microfluidic channels containing corners and flow (figure 1a), all four agr groups of S. aureus strains that we examined rapidly form biofilm streamers (figure 1b and Supplement figure 1), with slight differences in morphology. However, for the detailed experiments on biofilm streamer initiation and clogging that are described below, we restrict ourselves to study only one representative strain, S. aureus RN6734, which possesses the agr I system.

Figure 1.

The human pathogen S. aureus forms biofilm streamers. (a) Schematic drawing of the experimental apparatus, where the flow through the channel (cross section of 200 μm × 200 μm) was driven by a syringe pump, which was set to a flow rate of 1.5 ± 0.05 μL/min. (b) S. aureus biofilms were visualized with a green fluorescent nucleic acid stain (SYTO 9, Invitrogen), and a confocal microscope was used to obtain three-dimensional images of S. aureus agr group I (strain RN6734). The suspension we flowed through the channel was at a cell density that corresponds to OD600=1.2. The edges of the microfluidic channel are indicated with purple lines. The inset illustrates that the biofilm streamer is a porous filamentous structure. The diameter of the streamer network is ∼100 μm in this image. The image in the inset was taken with the focal plane perpendicular to the vertical z-axis, and in the middle of the channel, which is 100 μm from the bottom of the channel. The scale bar represents 200 μm.

To visualize the morphology of the biofilm streamers, we stained the S. aureus cells with a fluorescent dye. This method revealed a three-dimensional structure suspended between the corners of the channel (figure 1b). High-resolution confocal images of these streamers show that they initially consist of porous networks that, over time, become more rigid and less porous.

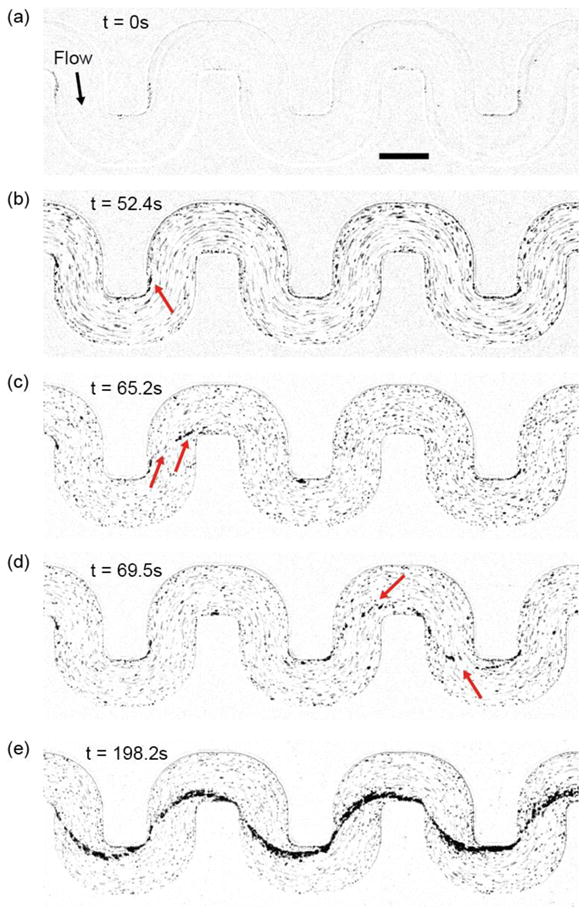

S. aureus initiates biofilm streamers in a similar manner to P. aeruginosa (48, 56) but, under equivalent conditions, does so more rapidly. S. aureus biofilms initially form on the walls of the channel (figure 2a), and are subsequently deformed by flow into thicker clusters on the corners of the channel (figure 2b). Finally, due to flow, small filaments are pulled out from these clusters. We visualized the entire time sequence as the filaments elongate and attach to the channel walls of the closest downstream corner to form a biofilm bridge between adjacent corners (figure 2c). At this stage, streamers are thin (< 10 μm), flexible, and they vibrate in the flow. While the streamers remain flexible, they occasionally detach and reattach elsewhere downstream (figure 2d) (57, 58). It is also apparent that the filamentous biofilms form independently at different corners. After biofilm-corner-to-corner-bridge formation occurs, the width of the streamer increases due to accumulation of EPS and/or trapping of cells that flow past. As the streamers thicken, they also appear to become more rigid as we observe that they cease to vibrate in the flow (figure 2e).

Figure 2.

Initiation of the S. aureus biofilm streamer and its rapid expansion. The displayed images are representative snapshots from a movie, acquired at 30 fps using bright field illumination. The images were taken at a focal plane that is perpendicular to gravity and in the middle of the channel, which is 100 μm from the bottom of the channel. (a) Initial image of the channel, which is coated with human blood plasma proteins. (b) A thin streamer originates from the corner on which surface-attached biomass has accumulated. (c) A streamer has bridged the gap between adjacent corners. At this stage, the streamer is flexible and vibrates in the flow. (d) Occasionally streamers become dislodged and they can reattach elsewhere downstream. (e) Stable streamers have formed on all corners and accumulated additional biomass, making them less flexible. The suspension we flowed through the channel was at a cell density that corresponds to OD600=1.2. The scale bar represents 200 μm.

In these models of physiological systems, flow is the major contributor to the shape of the biofilm structures, whereas bacterial motility is less significant since non-motile staphylococci exhibit a similar biofilm structure to that of their motile Gram-negative counterparts (48). This feature suggests that streamer formation may not depend on bacterial motility as flow itself can transport cells or biomass to the streamer site (48, 59). We conclude that, in this context, flow plays a major role in actively shaping the three-dimensional structure of the biofilms (46, 48, 50, 60-64), in addition to affecting nutrient gradients and social behaviors in biofilms (65-68). By contrast, in environments lacking flow, motility seems to be important for accumulation of cells near surfaces and subsequent biofilm formation (69-71).

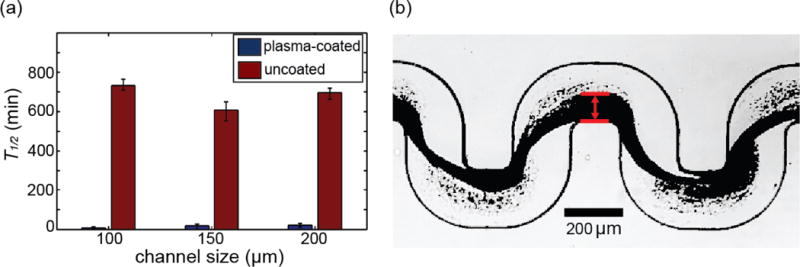

2.2. Blood plasma coating expedites biofilm streamer formation and clogging of the channel

To examine the effect of realistic surface chemistry on S. aureus biofilm formation in our microfluidic channels with complex geometries, we coated the channels with human blood plasma (72). In static conditions, S. aureus biofilm formation is absent, or strongly reduced, when the surfaces are not coated with human blood plasma (73, 74). However, in our microfluidic flow channels, S. aureus biofilms also form in the absence of blood plasma surface coating. Nonetheless, biofilm formation is strongly affected by the surface coating in our system. Indeed, after initiation of flow in microfluidic channels that were coated with human plasma proteins, streamers robustly bridge the distance between corners at all 36 bends of our microfluidic channel within a few minutes, following rapid attachment of cells to the surface. By contrast, in the absence of blood plasma surface coating, it takes several hours to form streamers between all the bends in our channel. After streamer formation between the bends of the channel, rapid biomass accumulation of streamers occurs in a way that is independent of the size of the channels (figure 3). Furthermore, detachment of streamers from the surface occurs less frequently in the blood-plasma-coated channel, indicating that the cells were more strongly attached to the blood-plasma-coated chambers than to the non-coated chambers. Enhanced surface-attachment is consistent with previous reports of binding of bacterial membrane-associated proteins to immobilized blood plasma proteins (38). In addition, the presence of blood plasma may also induce changes in S. aureus gene expression that promote attachment or EPS production to further accelerate biofilm streamer formation. In summary, S. aureus biofilm streamers initiate via a rapid mechanism that relies on binding of S. aureus cells to immobilized blood plasma proteins on the walls of the channels. For P. aeruginosa, not only the initial surface-attachment of a few cells is important, but also cell-growth and division is required for the cells to form confluent surface-attached biofilms over tens of hours. Thus, in the case of P. aeruginosa, the process takes tens of hours (48). By contrast, the time scale for S. aureus biofilm streamer initiation is not sufficient for substantial cell growth, particularly when the surfaces are coated with human blood plasma (figure 3a), which indicates that cell growth is not essential for S. aureus streamer formation.

Figure 3.

with human blood plasma affects S. aureus biofilm streamer formation. (a) We measured the time, T1/2, until biofilm streamers have grown in situ to occupy half of the channel width at a fixed flow rate of 1.5 ± 0.05 μL/min and at a fixed bacterial cell concentration (optical density at 600 nm = 0.46 ± 0.05). We used three different channels with square cross-sections of different side lengths: 100 μm, 150 μm and 200 μm. Coating the microfluidic channels with human plasma prior to bacterial inoculation leads to rapid accumulation of biomass compared with non-coated channels, independent of the size of the channels. The error bars indicate the range of values from three independent replicates. (b) A typical image used to measure the biofilm thickness.

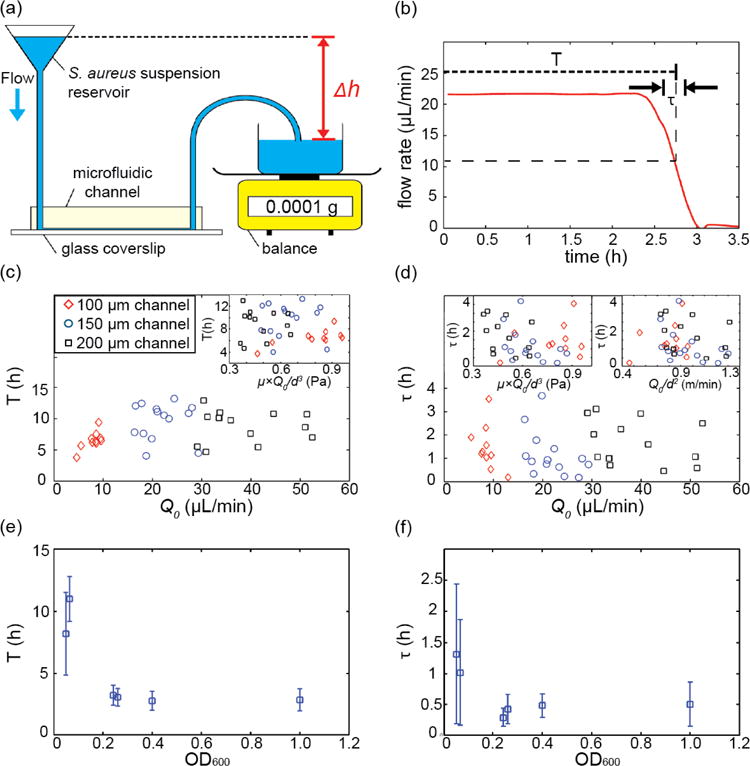

Expansion of biofilm streamers increases the hydrodynamic resistance of the channel, which ultimately leads to clogging of the microfluidic device, if the pressure difference that drives the flow remains constant. To investigate clogging dynamics caused by S. aureus biofilms, we applied a constant pressure difference across the microfluidic system containing channels coated with blood plasma (figure 4a), which drives a constant flow rate Q0 prior to the clogging transition. We measured the clogging time, T, at which the flow rate was reduced to Q0/2 (figure 4b; Materials and Methods). In addition, we measured the duration of the clogging transition, τ, which we defined as the time at which the flow rate decreases from 75% to 25% of Q0 (figure 4b; Materials and Methods). We found that T and τ are approximately independent of flow rates, flow speed, shear stress, and channel sizes, for the flow rates we investigated (figure 4c and 4d). However, increasing the bacterial cell density that flows through the channel from OD600∼0.05 to OD600∼0.2 (OD600 is the optical density at 600 nm, which is a common measure of cell density in suspensions) significantly reduced both the clogging time and the clogging transition duration (figure 4e and 4f), yet increasing the cell density further had no strong effects on T and τ. As the onset of the clogging transition is highly correlated with the formation of biofilm streamers, and the clogging duration is highly correlated with the streamer expansion, figure 4e and 4f reveal that streamer initiation and expansion have a strong dependence on cell density at low cell densities, and a weak dependence on cell density at high cell densities. The effect of cell density in initiation and clogging is consistent with the interpretation that biofilm streamers initiate by blood-plasma-protein-mediated attachment of cells to the wall. In addition, increased production of surface-attachment-mediating proteins by S. aureus during the exponential growth phase should also increase the probability of attachment to surfaces and consequently stimulate biofilm formation (75-77), ultimately leading to more rapid clogging.

Figure 4.

Dynamics of biofilm-induced clogging for S. aureus under constant pressure drop flow conditions. (a) Schematic drawing of the experimental apparatus: early or mid exponential phase S. aureus cells are loaded into a reservoir. Using wide-bore tubing, this reservoir is connected to the microfluidic channel. The effluent collection dish is placed on an analytical balance. The height difference, Δh, between the reservoir suspension and the effluent collection dish is proportional to the applied pressure difference. (b) The weight of the effluent suspension as a function of time is converted into the flow rate, Q0, as a function of time using Eq. (8). Using this flow rate measurement, the time to clogging, T, and the duration of the clogging transition, t, were measured for each channel. (c, d) T and τ for different flow rates, shear stress, flow speeds and different channel sizes. All channels had a square cross-section, with a width and height equal to d = 100 μm, 150 μm, or 200 μm. Shear stress and flow speed were calculated as μwater × Q0/d3 and Q0/d2 where μwater is the viscosity of water (∼0.001 Pa·s). T and τ appear to be independent of channel size, flow rate, shear stress, and flow speeds for the flow rates we investigated. The suspension we flowed through the channel in these experiments was at a cell density that corresponds to OD600= 0.06 ± 0.01. (e, f) T and τ depend strongly on the bacterial cell concentration of the suspension flowed through the channel.

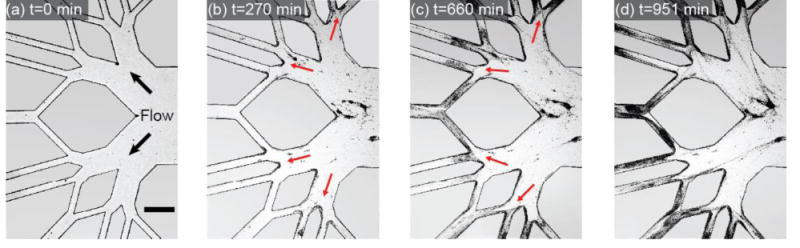

2.3. S. aureus streamers form in complex geometries

We demonstrate that S. aureus biofilm streamers are ubiquitous in complex geometries (figure 5). In particular, we found that biofilm streamers develop rapidly following inoculation and they span the gaps in a complex, branched channel. This example indicates that biofilm streamers might be universal in porous media in environmental and medical environments (48, 78-80), where they could cause rapid clogging.

Figure 5.

Time series of S. aureus biofilm streamer development in a branched network channel coated with human plasma proteins. Images were acquired at 20 frames per hour using phase contrast microscopy. The scale bar represents 500 μm.

2.4. Modeling biofilm streamers as hinged or clamped flexible filaments in curved flow

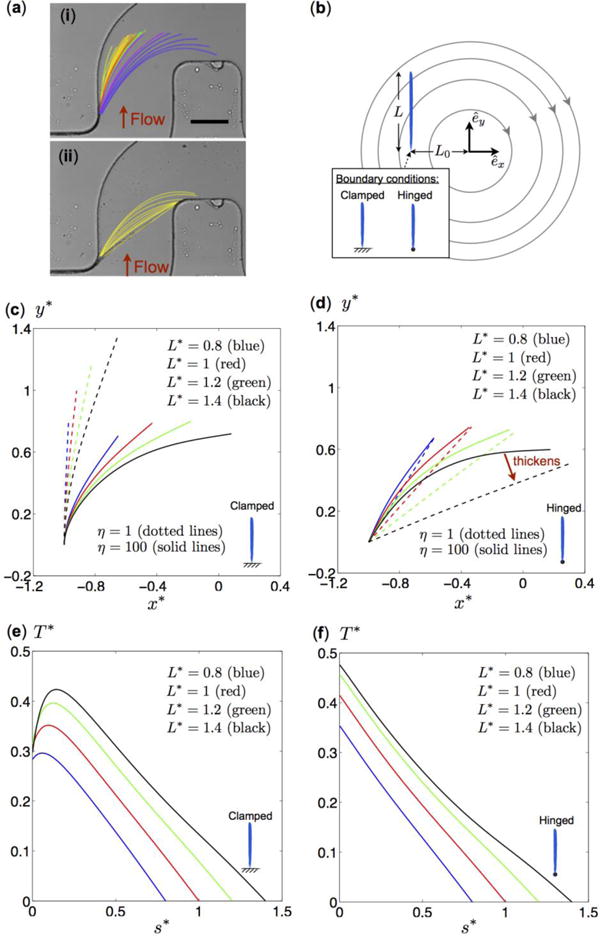

To understand how biofilm streamers that are bound on one corner can attach to the adjacent downstream corner, we examined the deformation of streamers in the flow as the streamers grow longer. The streamer stems from the left corner, growing in length with a reorientation in the clockwise direction towards the right corner (figure 6a-i). The curved shapes of the streamer filaments show that they are highly flexible. Once a biofilm bridge has formed between two corners, the biofilm bridge expands in radius and becomes straighter (figure 6a-ii) likely due to a reduction in flexibility of thicker biofilm bridges.

Figure 6.

(a) Image of a biofilm streamer during initial formation in a microfluidic channel where a bacterial cell concentration corresponding to OD600=0.5 was flowed through the channel by a syringe pump, which was set to a flow rate of 1.5 ± 0.05 μL/min. The red arrows indicate the flow direction: (i) The streamer grows in length and reorients in the clockwise direction towards the right corner of the channel. (ii) The streamer straightens as it becomes thicker. The scale bar represents 100 μm. (b) Schematic diagram of a model flow problem for a streamer of length L at a distance L0 from the origin in a flow with circular streamlines due to clockwise rigid body rotation. Two tethering conditions (vertically clamped and hinged filaments) are considered. (c, d) Steady-state shapes of vertically clamped filaments (c) and hinged filaments (d) of different lengths and flexibility (as indicated in the figure). The solid and dotted lines represent results for relatively rigid (η = 1) and flexible (η = 100) filaments, respectively. Colored lines correspond to filaments of dimensionless lengths L* = L/L0 0.8 (blue), L* = 1.0 (red), L* = 1.2 (green), and L* = 1.4 (black). The shapes are shown in terms of dimensionless coordinates x* = x/L0 and y* = y/L0. (e, f) Vertically clamped filaments and hinged filaments of dimensionless steady-state tension profiles (EQUATION), as a function of the dimensionless arc length s* = s/L along the flexible (η = 100) filaments. Colored lines correspond to different dimensionless lengths: L* = L/L0 = 0.8 (blue), L* = 1.0 (red), L* = 1.2 (green), and L* = 1.4 (black).

To characterize this system mathematically, we consider an idealized model flow problem capturing some essential features of the current scenario, based on a flexible filament that is anchored at one end and expands in length in the presence of curved streamlines. Arguably the simplest flow with curved streamlines is the steady rigid body rotation flow with velocity ν⃗ in the clockwise direction ν⃗ = γ˙(yêx − xêy), where γ˙ is the rotation rate. This flow results in circular streamlines, as shown in figure 6b. We model the biofilm streamer as a flexible slender filament of radius r, length L, and bending stiffness B. The position vector of the filament is denoted as x⃗(s, t) = x(s, t)êx + y(s, t)êy, where s ∈ [0, L] is the arc length. One end of the filament is tethered at the position x⃗0 = L0êx, a distance L0 from the origin, where this geometry is motivated by a streamer tethered at the surface of the experimental channel.

To model the dynamics of the filament, we exploit the slenderness of the streamer and use resistive force theory (81-83) to characterize the viscous force per unit length f⃗viscous on the streamer

| (1) |

where ζ‖ = 2πμ/log(L/r) and ζ⊥ = 2ζ‖ are the drag coefficients for a slender filament moving, respectively, parallel and perpendicular to its axis. We denote derivatives on x⃗ with respect to arclength s or time t with subscripts. The streamer flexibility is described by the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory (84), which gives rise to an elastic force per unit length

| (2) |

where B = EI is the constant bending stiffness of the filament, i.e. the product of the Young's modulus E and the area moment of inertia I, and T(s, t) can be interpreted as the tension along the streamer to enforce its inextensibility. The force balance f⃗viscous + f⃗elastic = 0⃗ results in an elastohydrodynamic equation governing the deformation of a flexible streamer with position vector x⃗(s, t) in the rotating flow (see Materials and Methods for details).

A dimensionless parameter for comparing viscous and elastic forces is given by ηL = ζ⊥ U0L3/B, where the background flow U0 scales with the distance from the origin as U0 ∼ γ˙L0. A larger value of ηL represents effectively a more flexible filament. The dimensionless parameter can be rewritten as ηL = (L/L0)3η, where is independent of the filament length L. Here we consider a fixed distance from the origin L0 (hence a fixed η), and we vary the effective flexibility ηL by changing the dimensionless filament length L/L0, so that the effective flexibility increases with filament length. To understand how the clockwise reorientation of the streamer occurs, we consider filaments that are hinged and those that are clamped at the tethering location. Hinged filaments are free to rotate at the tethering location, whereas clamped filaments have a fixed tangent at the tethering location.

For a vertically clamped filament (figure 6c), flexibility is essential for reorientation, since the filament would be vertical if it were completely rigid (η = 0). For flexible filaments (η > 0), increasing the dimensionless filament length L/L0 leads to higher effective flexibility ηL, which allows the filament to bend more in the clockwise direction. Filaments that are more flexible (η = 100, solid lines in figure 6c) can deform more strongly in flow than less flexible filaments (η = 1, dotted lines).

For a hinged filament, the physical picture is quite different from the clamped filaments (figure 6d), in spite of the apparent similarity of the filament shape in the two cases. We again consider flexible filaments (η = 100) with increasing length L/L0 (solid lines). However, for hinged filaments, flexibility does not play an essential role in the clockwise reorientation. Relatively rigid filaments (η = 1, dotted lines) turn more towards the clockwise direction than very flexible filaments (η = 100, solid lines). It is also found that the filament adopts similar shapes for large values of η. Unlike a clamped tether, a hinge cannot support any torques, and the filament is therefore free to rotate at the tethered end. The reorientation mechanism in the hinged case is primarily due to the change of filament length, which alters the torque balance at the hinge. In the case of completely rigid hinged rods (η = 0) in the simple rotating flow considered here, we can derive an analytical formula for the steady-state tangent vector of the straight filament

| (3) |

which was obtained by a torque balance about the hinge. Eq. 3 illustrates that increasing the filament length L/L0 reorients the filaments in the clockwise direction, as a consequence of the altered torque balance. The limit L/L0 = 3/2 corresponds to a rigid rod oriented horizontally in the rotating flow, and any further increase in L/L0 does not support a steady-state configuration so that the rod rotates about the hinge.

Biofilm streamers are likely to behave more like hinged filaments than clamped filaments, because there are no geometric constraints that prevent the streamers from freely rotating at the tether. This model predicts that, as biofilm streamers become longer, their orientation changes towards the clockwise direction (figure 6a-i and figure 6d). We also note that the model also predicts that as hinged filaments become less flexible, the stiffening induces further clockwise reorientation (figure 6a-ii and compare black solid and dotted lines in figure 6d for a streamer with the same length L/L0 but different flexibility η). By contrast, if the streamer is clamped at one end, the stiffening streamer should reorient in the counter-clockwise direction.

Our mathematical model can also be used to estimate the tension in the biofilm streamer, which is important for determining under which conditions streamers become dislodged. For vertically clamped filaments, the tension varies non-monotonically along the filament with maxima present near the tethered end (figure 6e). The location of the maximum tension is at the point at which the filament will break if it cannot withstand the tension. By contrast, tension decreases monotonically along hinged filaments, and the maxima always occur at the hinged end (figure 6f). Experimentally, we also observe that biofilm streamers become dislodged close to the tethering location.

In this section we illustrated how flexibility and tethering conditions of biofilm filaments affect their orientation in the curved flow fields with a simple rotating flow. Although the model captures the fundamental feature of curved streamlines, quantitative comparisons with the experiments are, however, beyond the reach of the current work because the background flow employed in the model is a highly idealized rotating flow, compared with the actual flow in the microfluidic channel. The idealized flow model here is intended to uncover qualitatively interesting physical features associated with curved streamlines. In future work, we will consider more realistic flow models and explore the idea of estimating the elasticity of biofilm streamers based on their deformed shape in more realistic flows.

3. Conclusion

We used model microfluidic systems to investigate how environmental factors, such as surface geometry, surface chemistry, and fluid flow affect biofilm formation of S. aureus. We discovered that S. aureus forms flow-induced, filamentous biofilm streamers in curvy channels of different sizes more rapidly than P. aeruginosa. When surfaces were coated with human blood plasma, streamers appeared within minutes and grew to clog the channels on a rapid timescale. We found that S. aureus biofilm streamers also formed in different flow geometries, which led us to hypothesize that S. aureus biofilm streamers are ubiquitous in natural, and possibly infectious, environments. Using mathematical modeling, we showed how flexibility and tethering conditions of biofilm filaments affect their orientation in the flow fields with curved streamlines. Whether species other than P. aeruginosa and S. aureus form biofilm streamers, and which rheological features of the biofilm matrix are required for streamer formation are open questions that we are currently pursuing. Studying biofilm dynamics in environments that mimic physical and chemical conditions of natural habitats, such as inserted medical devices, holds the potential for identifying new biofilm structures, and perhaps such studies will reveal novel methods to prevent biofilm-related diseases.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Different S. aureus strains form biofilm streamers. Cultures of each strain (at cell densities corresponding to OD600=1.2) flowed through blood-plasma-coated channels at a constant flow rate of 1.5 μL/min. (a) S. aureus agr group II (strain RN6607). (b) agr group III (strain RN8465). (c) agr group IV (strain RN4850). The biofilm streamer morphology appears to be different for the strains with different agr systems. Images were acquired using bright field illumination. The scale bar represents 200 μm.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Tom Muir (Princeton University) for providing S. aureus strains, and members of the Stone lab for discussions. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM065859 (to B.L.B.), the National Science Foundation Grant MCB-1119232 (to H.A.S. and B.L.B.), an STX fellowship (M.K.K.), a Human Frontier Science Program fellowship (K.D.), and a Croucher Fellowship (O.S.P.).

Appendix: Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

All Staphylococcus aureus strains used in this study were generous gifts from Dr. Tom W. Muir's group (Princeton University), and were originally obtained from Dr. Richard Novick's group (New York University). S. aureus RN6734 is the standard agr group I laboratory strain (55). S. aureus RN6607 was isolated from a healthy human, and it represents agr group II (55, 85). S. aureus RN8465 is the agr group III prototype, also known as menstrual toxic shock syndrome strain (86, 87). S. aureus RN4850 is the agr IV prototype, and it was isolated from a patient with scalded skin syndrome (55, 88). All S. aureus strains were grown overnight in tryptic soy broth (TSB) supplemented with 0.5% glucose and 3% NaCl at 32 °C. Overnight cultures of S. aureus were back-diluted 1:100 in TSB, and grown to early or mid-exponential phase at 37 °C with shaking.

Microfluidic experiments and microscopy

Microfluidic channels were prepared from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184, Dow Corning) using conventional soft lithography techniques. Each channel was sealed to a glass microscope slide (75 × 50 × 1.0 mm, Corning) after air plasma treatment (Harrick Scientific, NY). The microfluidic devices consist of a single channel containing many corners and have a square cross-section. We used three different channels with different cross-sections, which had side lengths of 100 μm, 150 μm or 200 μm (figures 1, 2,3 4, and 6). Microfluidic devices consisting of a network of channels were 1600 μm wide and 30 μm high (figure 5). Some channels were coated with human blood plasma, according to the following procedure: Human blood plasma was purchased from Biological Specialty Corporation, PA, and was diluted with H2O to a 20% human blood plasma solution, which was flown into the microfluidic channels. These channels were then stored in a humid environment at 4 °C for 24 hours prior to bacterial inoculation (72) to ensure that the channels stay wetted. Bacterial cultures were introduced to the channels using either a constant flow driven by a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, MA) (figure 1a), or a constant pressure (details are provided below). Images of the biofilms were acquired using a Nikon Ti-Eclipse microscope under epifluorescence illumination and a CCD camera (iXon, Andor), or using phase contrast illumination on a Leica DM IRB microscope. Images were analyzed and processed using Matlab (Mathworks).

Flow driven by a constant pressure

When bacterial cultures were introduced into microfluidic channels at constant pressure, 100 mL of S. aureus culture was used to fill a reservoir connected via Tygon tubing (inner diameter 2.4 mm) and Luer connectors (Cole-Parmer) into an inlet of a microfluidic channel (figure 4a). The outlet was also connected to Tygon tubing, and the effluent culture was collected in a dish placed on an analytical balance capable of weighing to 0.1 mg precision. The height of the culture reservoir above the effluent culture dish determined the applied pressure difference Δp, and therefore the flow rate through the channel.

Analysis of flow rate time series

The weight of the effluent culture was measured every 4 s on an analytical balance (GD503, Sartorius), controlled via Labview (National Instruments). To obtain the flow rate time series Q(t) from the effluent weight time series w(t), we computed

| (4) |

where the density was assumed to be the density of water, 1 g/mL. The time to clogging, T, and the duration of the clogging transition, τ, were calculated by fitting the function to the measured flow rate Q(t), where Q0 is the flow rate prior to the clogging transition. The time τ is therefore defined as the time period in which the fitted flow rate decreases from 75% to 25% of Q0, while T is the time at which the fitted flow rate is 0.5Q0 (48).

Staining of biofilms in situ

To visualize the three-dimensional structures of streamers, we fluorescently stained the biofilms produced by S. aureus (figure 1b). For this assay, we very carefully and slowly removed the tubing carrying the bacterial culture from the inlet of the microfluidic channel after a streamer had formed. We then connected a syringe containing 5 μM SYTO 9 stain (Invitrogen) in phosphate buffered saline to the channel inlet, and flowed this solution through the channel to stain nucleic acids. To avoid the formation of bubbles in the channels, the liquid in the tubing that contains the staining solution has to make contact with the liquid in the channel before slowly pushing the tubing all the way into the channel inlet. The staining solution was flowed through the channel slowly to avoid disrupting the structure of the streamer.

Elastohydrodynamic model for the biofilm streamer

Using the resistive force theory described in the main text (81-83), the viscous force per unit length is given by

| (5) |

where ζ⊥ = 2ζ‖, x⃗ is the position vector, x⃗s is the unit tangent vector, x⃗t is the local filament velocity, and ν⃗ is the background flow velocity. The elastic force per unit length is modeled by the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory as

| (6) |

where T(s) is a Lagrange multiplier enforcing inextensibility of the filament; it may be interpreted as the tension along the filament. A force balance f⃗viscous + f⃗elastic = 0⃗ leads to the elastohydrodynamic equation

| (7) |

which can be inverted to obtain the equation governing the evolution of the filament shape x⃗(s, t)

| (8) |

We normalize lengths by L0, velocities by γ˙L0, time by 1/γ˙, and tension by , resulting in the following dimensionless equation

| (9) |

where the stars represent dimensionless variables, , s* ∈ [0, L*], and L* = L/L0. We omit the stars hereafter for simplicity and refer only to dimensionless variables unless otherwise stated.

The inextensibility condition prevents any local stretching, requiring x⃗s · x⃗s = 1 for all time, which implies ∂(x⃗s·x⃗s)/∂t = 0 ⇒ x⃗ st · x⃗s = 0. An equation for tension T(s) can be obtained from the elastohydrodynamic equation [Eq. (9)] with the aid of this inextensibility condition as follows:

| (10) |

where the following identities (obtained by repeated differentiation of the identity x⃗s · x⃗s = 1) have been used for simplification: x⃗s · x⃗ss = 0, x⃗s · x⃗sss = −x⃗ss · x⃗ss, x⃗s · x⃗ssss = −3x⃗ssx⃗sss, and x⃗sx⃗ssss = −4x⃗ss · x⃗ssss − 3x⃗sss · x⃗sss. The coupled equations [Equations (9) and (10)] can be solved numerically using the method outlined in Tornberg and Shelley (89), when appropriate boundary conditions are supplied.

For a vertically clamped filament, the dimensionless boundary conditions at the tethered end are given by x⃗(s = 0, t) = −êx, x⃗s(s = 0, t) = êy. At the free end, we have the force-free and torque-free conditions x⃗sss(s = L, t) = 0⃗ and x⃗ss(s = L, t) = 0⃗, respectively. For a hinged filament, in place of the geometrical constraint on the slope x⃗s(s = 0, t) = êy in the clamped case, we have the torque free condition x⃗ss(s = 0, t) = 0⃗ at the tethered end, and all other boundary conditions remain identical. Note that the steady-state filament shape is independent of the initial condition.

The boundary conditions of the tension equation are identical for both the clamped and hinged cases. At the free end, we simply require the tension to vanish T(s = L) = 0. The boundary condition for tension at the tethered end is less discussed in the literature and requires more consideration. We obtain the boundary condition by taking the inner product of the local tangent vector at the tethered end x⃗s(s = 0, t) with the elastohydrodynamic equation (Equation (9)) evaluated at the tethered end, where x⃗t(s = 0, t) = 0. This treatment leads to the following boundary condition for the tension equation at the tethered end:

| (11) |

References

- 1.Naimi TS, LeDell KH, Como-Sabetti K, Borchardt SM, Boxrud DJ, Etienne J, et al. Comparison of community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:2976–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herman RA, Kee VR, Moores KG, Ross MB. Etiology and treatment of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Health-Syst Ph. 2008;65:219–25. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy AD, Otto M, Braughton KR, Whitney AR, Chen L, Mathema B, et al. Epidemic community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Recent clonal expansion and diversification. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1327–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710217105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deleo FR, Chambers HF. Reemergence of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the genomics era. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2464–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI38226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowy FD. Antimicrobial resistance: the example of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1265–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI18535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otto M. MRSA virulence and spread. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:1513–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein E, Smith DL, Laxminarayan R. Hospitalizations and deaths caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, United States, 1999-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1840–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1312.070629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kock R, Becker K, Cookson B, van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Harbarth S, Kluytmans J, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): burden of disease and control challenges in Europe. Eurosurveillance. 2010;15:12–20. doi: 10.2807/ese.15.41.19688-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvis WR, Jarvis AA, Chinn RY. National prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in inpatients at United States health care facilities,2010. Am J Infect Control. 2010;40:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298:1763–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowy FD. Medical progress - Staphylococcus aureus infections. New Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parsek MR, Singh PK. Bacterial biofilms: an emerging link to disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:677–701. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Current concepts: prosthetic-joint infections. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:1645–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costerton JW. Biofilm theory can guide the treatment of device-related orthopaedic infections. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2005;437:7–11. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200508000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomsen TR, Hall-Stoodley L, Moser C, Stoodley P. The role of bacterial biofilms in infections of catheters and shunts. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braxton EE, Ehrlich GD, Hall-Stoodley L, Stoodley P, Veeh R, Fux C, et al. Role of biofilms in neurosurgical device-related infections. Neurosurgical Review. 2005;28:249–55. doi: 10.1007/s10143-005-0403-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cramton SE, Gerke C, Schnell NF, Nichols WW, Gotz F. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5427–33. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5427-5433.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branda SS, Vik A, Friedman L, Kolter R. Biofilms: the matrix revisited. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flemming HC, Wingender J. The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:623–33. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davey ME, O'Toole GA. Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol Mol Biol R. 2000;64:847–67. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.4.847-867.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kizhner V, Krespi YP, Hall-Stoodley L, Stoodley P. Laser-generated shockwave for clearing medical device biofilms. Photomed Laser Surg. 2011;29:277–82. doi: 10.1089/pho.2010.2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.del Pozo JL, Patel R. The challenge of treating biofilm-associated bacterial infection. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82:204–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Molin S, Ciofu O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Ag. 2010;35:322–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krespi YP, Kizhner V, Nistico L, Hall-Stoodley L, Stoodley P. Laser disruption and killing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Am J Otolaryngol. 2011;32:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall-Stoodley L, Stoodley P. Evolving concepts in biofilm infections. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1034–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mah TF, Pitts B, Pellock B, Walker GC, Stewart PS, O'Toole GA. A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature. 2003;426:306–10. doi: 10.1038/nature02122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen D, Joshi-Datar A, Lepine F, Bauerle E, Olakanmi O, Beer K, et al. Active Starvation Responses Mediate Antibiotic Tolerance in Biofilms and Nutrient-Limited Bacteria. Science. 2011;334:982–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1211037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Billings N, Ramirez Millan M, Caldara M, Rusconi R, Tarasova Y, Stocker R, et al. The extracellular matrix component Psl provides fast-acting antibiotic defense in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. PLoS Pathogens. 2013;9:e1003526. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ehrlich GD, Ahmed A, Earl J, Hiller NL, Costerton JW, Stoodley P, et al. 2010The distributed genome hypothesis as a rubric for understanding evolution in situ during chronic bacterial biofilm infectious processes FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol59269–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimick JB, Pelz RK, Consunji R, Swoboda SM, Hendrix CW, Lipsett PA. Increased resource use associated with catheter-related bloodstream infection in the surgical intensive care unit. Arch Surg Chicago. 2001;136:229–34. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darouiche RO. Current concepts - Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. New Engl J Med. 2004;350:1422–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Periasamy S, Joo HS, Duong AC, Bach THL, Tan VY, Chatterjee SS, et al. How Staphylococcus aureus biofilms develop their characteristic structure. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:1281–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115006109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiedrowski MR, Horswill AR. New approaches for treating staphylococcal biofilm infections. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 2011;1241:104–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rupp CJ, Fux CA, Stoodley P. Viscoelasticity of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in response to fluid shear allows resistance to detachment and facilitates rolling migration. Appl Environ Microb. 2005;71:2175–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.4.2175-2178.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Francois P, Vaudaux P, Lew PD. Role of plasma and extracellular matrix proteins in the physiopathology of foreign body infections. Ann Vasc Surg. 1998;12:34–40. doi: 10.1007/s100169900112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Francois P, Schrenzel J, Stoerman-Chopard C, Favre H, Herrmann M, Foster TJ, et al. 2000Identification of plasma proteins adsorbed on hemodialysis tubing that promote Staphylococcus aureus adhesion J Lab Clin Med13532–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuusela P, Vartio T, Vuento M, Myhre EB. Attachment of Staphylococci and Streptococci on fibronectin, fibronectin fragments, and fibrinogen bound to a solid-phase. Infect Immun. 1985;50:77–81. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.1.77-81.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaudaux PE, Francois P, Proctor RA, Mcdevitt D, Foster TJ, Albrecht RM, et al. Use of adhesion-defective mutants of Staphylococcus aureus to define the role of specific plasma proteins in promoting bacterial sdhesion to canine arteriovenous shunts. Infect Immun. 1995;63:585–90. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.585-590.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foster TJ, Hook M. Surface protein adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:484–8. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gotz F. Staphylococcus and biofilms. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:1367–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yarwood JM, Bartels DJ, Volper EM, Greenberg EP. Quorum sensing in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:1838–50. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.6.1838-1850.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lauderdale KJ, Boles BR, Cheung AL, Horswill AR. Interconnections between sigma B, agr, and proteolytic activity in Staphylococcus aureus biofilm maturation. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1623–35. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewandowski Z, Stoodley P. Flow induced vibrations, drag force, and pressure drop in conduits covered with biofilm. Water Sci Technol. 1995;32:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoodley P, Lewandowski Z, Boyle JD, Lappin-Scott HM. Oscillation characteristics of biofilm streamers in turbulent flowing water as related to drag and pressure drop. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;57:536–44. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19980305)57:5<536::aid-bit5>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valiei A, Kumar A, Mukherjee PP, Liu Y, Thundat T. A web of streamers: biofilm formation in a porous microfluidic device. Lab Chip. 2012;12:5133–7. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40815e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rusconi R, Lecuyer S, Guglielmini L, Stone HA. Laminar flow around corners triggers the formation of biofilm streamers. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7:1293–9. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rusconi R, Lecuyer S, Autrusson N, Guglielmini L, Stone HA. Secondary flow as a mechanism for the formation of biofilm streamers. Biophys J. 2011;100:1392–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drescher K, Shen Y, Bassler BL, Stone HA. Biofilm streamers cause catastrophic disruption of flow with consequences for environmental and medical systems. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4345–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300321110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lipowsky HH, Kovalcheck S, Zweifach BW. Distribution of blood rheological parameters in microvascularature of cat mesentery. Circ Res. 1978;43:738–49. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weaver WM, Milisavljevic V, Miller JF, Di Carlo D. Fluid flow induces biofilm formation in Staphylococcus epidermidis polysaccharide intracellular adhesin-positive clinical isolates. Appl Environ Microb. 2012;78:5890–6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01139-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Novick RP. Autoinduction and signal transduction in the regulation of staphylococcal virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1429–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Novick RP, Geisinger E. Quorum sensing in staphylococci. Annual Review of Genetics. 2008;42:541–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2001;55:165–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thoendel M, Kavanaugh JS, Flack CE, Horswill AR. Peptide signaling in the Staphylococci. Chem Rev. 2011;111:117–51. doi: 10.1021/cr100370n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Geisinger E, Chen J, Novick RP. Allele-dependent differences in quorum-sensing dynamics result in variant expression of virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:2854–64. doi: 10.1128/JB.06685-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guglielmini L, Rusconi R, Lecuyer S, Stone HA. Three-dimensional features in low-Reynolds-number confined corner flows. J Fluid Mech. 2011;668:33–57. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stoodley P, Lewandowski Z, Boyle JD, Lappin-Scott HM. Structural deformation of bacterial biofilms caused by short-term fluctuations in fluid shear: an in situ investigation of biofilm rheology. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;65:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stoodley P, Cargo R, Rupp CJ, Wilson S, Klapper I. Biofilm material properties as related to shear-induced deformation and detachment phenomena. J Ind Microbiol Biot. 2002;29:361–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rusconi R, Guasto J, Stocker R. Bacterial transport suppressed by fluid shear. Nat Phys. 2014;10:212–7. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stoodley P, Lewandowski Z, Boyle JD, Lappin-Scott HM. The formation of migratory ripples in a mixed species bacterial biofilm growing in turbulent flow. Environ Microbiol. 1999;1:447–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stoodley P, Dodds I, Boyle JD, Lappin-Scott HM. Influence of hydrodynamics and nutrients on biofilm structure. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;85:19S–28S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1998.tb05279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stewart PS. Mini-review: convection around biofilms. Biofouling. 2012;28:187–98. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2012.662641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kostenko V, Salek MM, Sattari P, Martinuzzi RJ. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and tolerance to antibiotics in response to oscillatory shear stresses of physiological levels. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;59:421–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salek MM, Jones SM, Martinuzzi RJ. The influence of flow cell geometry related shear stresses on the distribution, structure and susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa 01 biofilms. Biofouling. 2009;25:711–25. doi: 10.1080/08927010903114603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Picioreanu C, van Loosdrecht MCM, Heijnen JJ. Mathematical modeling of biofilm structure with a hybrid differential-discrete cellular automaton approach. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;58:101–16. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19980405)58:1<101::aid-bit11>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bottero S, Storck T, Heimovaara TJ, van Loosdrecht MC, Enzien MV, Picioreanu C. Biofilm development and the dynamics of preferential flow paths in porous media. Biofouling. 2013;29:1069–86. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2013.828284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nadell CD, Bucci V, Drescher K, Levin SA, Bassler BL, Xavier JB. Cutting through the complexity of cell collectives. P Roy Soc B. 2013;280:20122770. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Drescher K, Nadell CD, Stone HA, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. Solutions to the public goods dilemma in bacterial biofilms. Curr Biol. 2014;24:50–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Drescher K, Dunkel J, Cisneros LH, Ganguly S, Goldstein RE. Fluid dynamics and noise in bacterial cell-cell and cell-surface scattering. P Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:10940–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019079108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O'Toole GA, Kolter R. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lemon KP, Higgins DE, Kolter R. Flagellar motility is critical for Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4418–24. doi: 10.1128/JB.01967-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen P, Abercrombie JJ, Jeffrey NR, Leung KP. An improved medium for growing Staphylococcus aureus biofilm. J Microbiol Meth. 2012;90:115–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beenken KE, Blevins JS, Smeltzer MS. Mutation of sar A in Staphylococcus aureus limits biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4206–11. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.4206-4211.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Walker JN, Horswill AR. A coverslip-based technique for evaluating Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation on human plasma. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:39. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Harris LG, Foster SJ, Richards RG. An introduction to Staphylococcus aureus, and techniques for identifying and quantifying S. aureus adhesins in relation to adhesion to biomaterials: review. European Cells & Materials. 2002;4:39–60. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v004a04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Ganesh VK, Hook M. Adhesion, invasion and evasion: the many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geoghegan JA, Monk IR, O'Gara JP, Fostera TJ. Subdomains N2N3 of fibronectin binding protein A mediate Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and adherence to fibrinogen using distinct mechanisms. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:2675–83. doi: 10.1128/JB.02128-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stoodley P, Dodds I, De Beer D, Scott HL, Boyle JD. Flowing biofilms as a transport mechanism for biomass through porous media under laminar and turbulent conditions in a laboratory reactor system. Biofouling. 2005;21:161–8. doi: 10.1080/08927010500375524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Picioreanu C, Vrouwenvelder JS, van Loosdrecht MCM. Three-dimensional modeling of biofouling and fluid dynamics in feed spacer channels of membrane devices. J Membr Sci. 2009;345:340–54. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Marty A, Roques C, Causserand C, Bacchin P. Formation of bacterial streamers during filtration in microfluidic systems. Biofouling. 2012;28:551–62. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2012.695351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gray J, Hancock GJ. The propulsion of sea-urchin spermatozoa. J Exp Biol. 1955;32:802–14. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wiggins CH, Riveline D, Ott A, Goldstein RE. Trapping and wiggling: Elastohydrodynamics of driven microfilaments. Biophys J. 1998;74:1043–60. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74029-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Autrusson N, Guglielmini L, Lecuyer S, Rusconi R, Stone HA. The shape of an elastic filament in a two-dimensional corner flow. Phys Fluids. 2011;23:063602. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Landau LD, Lifshitz EM, Kosevich AM, Pitaevskiæi LP. Theory of Elasticity. 3rd. Oxford; New York: Pergamon Press; 1986. p. viii, 187. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shinefield HR, Eichenwald HF, Ribble JC, Boris M. Bacterial interference-its effect on nursery-acquired infection with Staphylococcal aureus. 1. Preliminary observations on artificial colonization of newborns. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1963;105:646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ji GY, Beavis R, Novick RP. Bacterial interference caused by autoinducing peptide variants. Science. 1997;276:2027–30. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kreiswirth BN, Novick RP, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll M. Genetic studies on Staphylococcal strains from patients with toxic shock syndrome. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1982;96:974–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-6-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jarraud S, Lyon GJ, Figueiredo AMS, Lina G, Vandenesch F, Etienne J, et al. Exfoliatinproducing strains define a fourth agr specificity group in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:7027. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.22.6517-6522.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tornberg AK, Shelley MJ. Simulating the dynamics and interactions of flexible fibers in Stokes flows. J Comput Phys. 2004;196:8–40. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Different S. aureus strains form biofilm streamers. Cultures of each strain (at cell densities corresponding to OD600=1.2) flowed through blood-plasma-coated channels at a constant flow rate of 1.5 μL/min. (a) S. aureus agr group II (strain RN6607). (b) agr group III (strain RN8465). (c) agr group IV (strain RN4850). The biofilm streamer morphology appears to be different for the strains with different agr systems. Images were acquired using bright field illumination. The scale bar represents 200 μm.