Abstract

At present, it is not clear whether the current definition of separation anxiety disorder (SAD) is the optimal classification of developmentally inappropriate, severe, and interfering separation anxiety in youth. Much remains to be learned about the relative contributions of individual SAD symptoms for informing diagnosis. Two-parameter logistic Item Response Theory analyses were conducted on the eight core SAD symptoms in an outpatient anxiety sample of treatment-seeking children (N=359, 59.3% female, MAge=11.2) and their parents to determine the diagnostic utility of each of these symptoms. Analyses considered values of item threshold, which characterize the SAD severity level at which each symptom has a 50% chance of being endorsed, and item discrimination, which characterize how well each symptom distinguishes individuals with higher and lower levels of SAD. Distress related to separation and fear of being alone without major attachment figures showed the strongest discrimination properties and the lowest thresholds for being endorsed. In contrast, worry about harm befalling attachment figures showed the poorest discrimination properties, and nightmares about separation showed the highest threshold for being endorsed. Distress related to separation demonstrated crossing differential item functioning associated with age—at lower separation anxiety levels excessive fear at separation was more likely to be endorsed for children ≥9 years, whereas at higher levels this symptom was more likely to be endorsed by children <9 years. Implications are discussed for optimizing the taxonomy of SAD in youth.

Keywords: Separation Anxiety Disorder, Item Response Theory, symptom, taxonomy, child anxiety, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent class of mental disorders in childhood, affecting roughly 32% of youth by adolescence (Merikangas et al., 2010). Separation anxiety disorder (SAD) is one of the most commonly diagnosed anxiety disorders in preadolescent children, with prevalence rates of 4-5% (Cartwright-Hatton, McNicol, & Doubleday, 2006; Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003). By adolescence, roughly 8% of youth have met diagnostic criteria for SAD at some point in their lives (Merikangas et al., 2010). As with other anxiety disorders, rates of SAD diagnosis vary based on patient age (Costello et al., 2003; Merikangas et al., 2010). Among youth, higher rates of SAD have been found in children under the age of 8, relative to older children. Higher rates of DSM-IV SAD and SAD symptoms have been observed in girls than boys in some samples (Fan, Su, & Su, 2008; Masi, Mucci, & Millepiedi, 2001; Shear, Jin, Ruscio, Walters, & Kessler, 2006), while in others, no sex differences in diagnostic or symptom prevalence have been observed (Kendall et al., 2010; Zhao & Wang, 2009). A diagnosis of SAD in childhood confers significant mental health risk across the lifespan. In childhood, a diagnosis of SAD is associated with increased child internalizing problems, physiological hyperarousal in separation situations, somatic complaints, academic difficulties, and school refusal, as well as disruptions in family functioning to accommodate child anxiety (Egger, Costello, & Angold, 2003; Grills-Taquechel, Fletcher, Vaughn, & Stuebing, 2012; Kearney, Sims, Pursell, & Tillotson, 2003; Kossowsky, Wilhelm, Roth, & Schneider, 2012; Lebowitz et al., 2012; Zolog et al., 2011). Further, if left untreated, childhood SAD is linked to increased risk of multiple anxiety disorders, as well as panic disorder and depression in adulthood (Lewinsohn, Holm-Denoma, Small, Seeley, & Joiner, 2008; Lipsitz, Martin, Mannuzza, & Chapman, 1994).

In the current iteration of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), SAD is defined as “developmentally inappropriate and excessive anxiety concerning separation from home or from those to whom the individual is attached” (APA, 2000, p. 125). Diagnostic criteria define excessive anxiety related to separation as manifested by the presence of any three of eight specified SAD symptoms: (1) recurrent excessive distress when separation from home or major attachment figures occurs or is anticipated; (2) persistent and excessive worry about losing, or about possible harm befalling, major attachment figure; (3) persistent and excessive worry that an untoward event will lead to separation from a major attachment figure (e.g., getting lost or being kidnapped); (4) persistent reluctance or refusal to go to school or elsewhere because of fear of separation; (5) persistently and excessively fearful or reluctant to be alone or without major attachment figures at home or without significant adults in other settings; (6) persistent reluctance or refusal to go to sleep without being near a major attachment figure or to sleep away from home; (7) repeated nightmares involving the theme of separation; (8) repeated complaints of physical symptoms (such as headaches, stomachaches, nausea, or vomiting) when separation from major attachment figures occurs or is anticipated (APA, 2000, p. 125). The proposed SAD definition for DSM-5 remains largely unadjusted, except for wording changes to support SAD diagnosis in adults. As defined by the DSM, these eight core symptoms are interchangeable and contribute equally to SAD diagnosis, but quantitative questions remain regarding the manner in which these symptoms may differentially inform a diagnosis of SAD.

Recent work has begun to explore differential rates of symptom endorsement, both within and between informants (Allen, Lavallee, Herren, Ruhe, & Schneider, 2010). In a clinical sample of children ages 4-15 with a primary diagnosis of SAD, the most frequent child-endorsed symptoms were a reluctance/refusal to go to sleep without major attachment figures nearby, and a fear/reluctance to be alone without major attachment figures. Similarly, the most frequent parent-reported symptoms were a reluctance/refusal to go to sleep without major attachment figures nearby, a fear/reluctance to be alone without major attachment figures, and recurrent and excessive distress related to separation from home or major attachment figure (Allen et al., 2010). The symptom endorsed least frequently by parents or children was the presence of nightmares related to the theme of separation.

A small body of work has recently begun to evaluate SAD symptom presence as a function of child age and sex. Among SAD youth aged 4-15 years, girls and younger children were more likely to display reluctance/refusal to go to school or other places due to fear or separation, whereas the likelihood of the other symptoms of SAD being present did not vary as a function of age or sex (Allen et al., 2010). Recent factor analytic work in very young children (2-3 years of age) yielded consistent factor loadings for symptoms of SAD across early development, suggesting that these symptoms are equally informative of separation anxiety throughout early development (Mian, Godoy, Briggs-Gowan, & Carter, 2012). Such work adds to our understanding of symptom frequencies and patterns among SAD youth, but empirical work is needed to elucidate potential differential symptom functioning across the SAD diagnostic criteria. Indeed, it is possible that some SAD symptoms are more “diagnostic” than others. Although the current taxonomy is supported by factor analytic work classifying separation anxiety as a unidimensional construct across childhood (Essau, Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, & Muñoz, 2013; Spence, 1998; Sterba et al., 2010; Strickland et al., 2011), it does not account for potential differential symptom functioning across SAD diagnostic criteria. Research examining the varied discriminating properties and thresholds for endorsement of SAD symptoms is needed to optimally inform future iterations of the SAD definition.

Given the high prevalence, considerable impairment, and unfavorable course associated with child SAD, effective identification and treatment are critical. Accurate assessment and an understanding of how symptoms differentially contribute to diagnosis constitute the critical first step in informing optimal intervention efforts, by enhancing the identification of appropriate candidates for treatment and informing treatment dose recommendations. At present it is not clear whether the current definition of SAD is the optimal classification system with which to define SAD in youth. For example, following GAD, SAD is the second most frequent disorder closely resembled among cases of anxiety disorder not otherwise specified (NOS; Comer, Gallo, Korathu-Larson, Pincus, & Brown, 2012)—a presentation characterized by clinically significant anxiety symptoms that do not meet full diagnostic criteria for a specified anxiety disorder but are nonetheless highly impairing. Other work investigating SAD in community samples suggests that using the three symptom count criteria does not represent a meaningful cut-point in SAD impairment and fails to identify all children who are experiencing impairing separation anxiety (Foley et al., 2008). Further, substantial empirical evidence challenges the current dichotomous classification of mental disorders as either present or absent and instead points to the classification of mental disorders across the lifespan through hierarchically organized dimensions of psychopathology occurring across a range of severity (Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1998; Clark, 2005; Eaton, Keyes, et al., 2012; Eaton, Krueger, et al., 2012; Krueger, Markon, Patrick, & Iacono, 2005; Lahey et al., 2004; Prenoveau et al., 2010; Ruscio, 2010; Skapinakis et al., 2011; Walton, Ormel, & Krueger, 2011). Given the current proposal to retain the three of eight symptom dichotomous definition of SAD for DSM-5 (APA, 2012), it is critical to determine how the individual SAD symptoms relate to the latent unidimensional structure of separation anxiety severity. Additionally, as the elimination of the childhood onset criterion has been proposed for DSM-5 (APA, 2012), it is also necessary to evaluate whether all symptoms are comparably informative of SAD severity across age groups and sexes.

Item Response Theory (IRT) analyses can be used to examine differential functioning across the symptoms of a diagnosis (see Steinberg & Thissen, in press). Though rooted in educational research, IRT analyses have more recently been applied to the evaluation of the properties of psychopathology symptoms. IRT analyses afford a sophisticated analytic methodology with which to evaluate the potentially varied discriminating properties and thresholds for endorsement of symptoms of psychopathology. IRT analyses produce Item Information Curves (IIC) that depict item discrimination values which reflect how well each symptom discriminates between an individual with higher and lower levels of that form of psychopathology and item threshold values which reflect the level of the specific psychopathology that must be present for each symptom to have a 50% chance of being endorsed. The Test Information Curve (TIC) can be generated by summing IICs across symptoms. The TIC indicates the precision with which the diagnostic criteria assess the latent trait of that form of psychopathology across the range of severity and describes the psychometric properties of the group of symptoms (i.e., the diagnostic criteria). Though similar to the construct of reliability within Classical Test Theory, within IRT this measure of precision can vary across the range of severity, rather than being restricted to one value for the symptom group as a whole. A broader peaked TIC indicates that the symptoms have differing thresholds and the diagnostic criteria measure the latent trait of the mental disorder across a broader range, supporting a quasi-continuous classification of the mental disorder (Langenbucher et al., 2004). Conversely, a sharply peaked TIC indicates that the symptoms have fairly similar thresholds, meaning that the diagnostic criteria precisely assess the mental disorder within a narrow range of severity. In such a case, the TIC would support the dichotomous classification of the mental disorder under investigation.

IRT has been employed to evaluate the psychometric properties of panic attack symptoms (Sunderland, Hobbs, Andrews, & Craske, 2012), revealing that symptoms of choking, fear of dying, and tingling/numbness, have the highest threshold for being endorsed, qualifying them as the most severe symptoms of panic. With these analyses, Sunderland and colleagues (2012) were able to conclude that not all symptoms of a panic attack are equally informative of panic attack severity, and that the hierarchical ranking of some symptoms may vary by age or sex. IRT has also been used to evaluate the classification of alcohol use disorders, with resulting item threshold scores showing a lack of support for the classification of alcohol abuse and dependence as separate disorders of differential severity (Gilder, Gizer, & Ehlers, 2011). Additionally, differential functioning of depression symptoms between patients with bipolar and unipolar depression has been established through IRT investigation (Weinstock, Strong, Uebelacker, & Miller, 2009).

The current investigation employed two-parameter logistic IRT analyses to determine the item threshold and discrimination properties for SAD symptoms reported by children or their parents. For each symptom, item discrimination values (reflecting how well each SAD symptom discriminates between children with higher and lower levels of separation anxiety) and item threshold (reflecting the level of separation anxiety that must be present for each SAD symptom to have a 50% chance of being endorsed) were computed. We also examined differential item functioning (DIF) with regard to age, sex, and SAD diagnostic status to determine whether subgroups show different probabilities of endorsing various symptoms at a given severity of separation anxiety. Additionally, we evaluated crossing DIF with regard to age, sex, and SAD diagnostic status to determine whether patients show different probabilities of endorsing various symptoms as a function of age, sex, or SAD diagnostic status and latent SAD severity.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 359 outpatient children and adolescents ages 17 and below presenting for assessment at a university-affiliated outpatient center for the treatment of emotional disorders who completed the SAD module of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (ADIS-IV-C/P). Cases were drawn from a larger consecutive series of 671 families seeking services for child anxiety; cases in which ADIS-IV-C/P skip-outs prevented the assessment of all eight core separation anxiety symptoms (n=312) were not included. Of the 359 children, 34.3% met criteria for a diagnosis of SAD. Girls constituted the larger portion of the sample (59.3%). The mean age of the children was 11.17 years (SD =2.99). Within the sample, 3.6% of children were younger than 7 years, 23.4% of children were between the ages of 7 and 9 years, 26.8% were between the ages of 9 and 11 years, 18.6% were between the ages of 11 and 13 years, and 27.6% were 13 years or older. The sample was predominantly non-Hispanic Caucasian (81.1%) and lived in two-parent homes with married parents (82.2%; 9.5% separated/divorced, 3.9% never married). Among these children, the largest percentages were from families with poverty index score (i.e., household income divided by U.S. poverty threshold in the interview year; see Merikangas et al., 2010) ranging from 1.5 to <3 (24.5%) and from 3 to <6 (50.2%). Children in the sample met diagnostic criteria for an average of 2.06 clinical diagnoses. The most common diagnoses included generalized anxiety disorder (38.2%), SAD (34.3%), social anxiety disorder (27.0%), anxiety disorder not otherwise specified (18.9%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (15.3%), Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia (7.8%), Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (7.5%), and Specific Phobias (Animal Type, 6.4%; Environmental Type, 5.8%; Blood Injection Injury Type, 5.8%; Situational Type, 5.0%; Vomit, 8.4%; Other type, 3.9%). All other diagnoses assessed via the ADIS-IV-P/C were present in less than 4% of the sample (prevalence rates sum to > 100% due to comorbidity).

Measures

SAD symptoms and diagnosis

Diagnoses were established with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child/Parent Version (ADIS-IV-C/P; Silverman & Albano, 1997), a semi-structured interview designed to ascertain reliable diagnosis of anxiety and mood disorders, as well as several externalizing disorders, and to screen for the presence of other conditions (e.g., psychotic, somatoform, and pervasive developmental disorders), in strict accordance with DSM-IV. The ADIS-IV-C/P has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in clinical samples, including test-retest and inter-rater reliability (Lyneham, Abbott, & Rapee, 2007; Silverman, Saavedra, & Pina, 2001), and concurrent validity (Wood, Piacentini, Bergman, McCracken, & Barrios, 2002). Within the clinic from which the present sample was drawn, 12.5% of a sample of 608 ADIS-IV-C/P interviews were rated by two diagnosticians and yielded good inter-rater agreement (κ = .866). Parent and child interviews were conducted separately, during which each of the eight core symptoms of SAD were assessed within the ADIS-IV-C/P SAD module using dichotomous ratings (yes/no) to assess symptom presence, in the absence of symptom severity. In accordance with ADIS-IV-C/P skip-out rules (see Silverman & Albano, 1997), only participants who were reporting some degree of separation anxiety (clinical or sub-clinical) were administered questions assessing all 8 SAD symptoms. To determine whether a symptom of SAD was present, the “or” rule was applied at the symptom level (see Comer & Kendall, 2004), such that a given SAD symptom was considered present if it was endorsed either during the child interview or the parent interview. After completion of both interviews, a composite diagnostic profile was generated. For each diagnosis, interviewers assign a 0–8 clinical severity rating (CSR) indicating the degree of distress and impairment associated with the disorder (0= none to 8= very severely disturbing/disabling). In accordance with ADIS-IV-C/P scoring procedures, CSRs of 4 or greater are used to denote disorders that meet or surpass the threshold for a formal DSM-IV diagnosis. All children who received a diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder had a CSR rating or 4 or greater.

Procedure

Participants were recruited at a university-affiliated outpatient center for the treatment of emotional disorders in New England. As part of clinic procedures, families completed an initial telephone screening. Children were excluded with current psychotic symptoms, suicidal or homicidal risk requiring crisis intervention, 2 or more hospitalizations for severe psychopathology (e.g., psychosis) within the previous 5 years, or moderate to severe intellectual impairments. Prior to participation, children on psychotropic medications were required to be stabilized for at least one month. As part of an evaluation battery for treatment, families were administered the ADIS-IV-C/P. After obtaining informed consent from parents, and assent from children ages 11 and older, a diagnostician conducted separate child and parent interviews, and then integrated diagnostic profiles to generate a composite diagnostic profile. For each case, interview material was presented and reviewed at a weekly diagnostician staff meeting, during which time symptoms were reviewed and a team consensus on the diagnostic profile was obtained. Diagnosticians included a panel of 22 clinical psychologists, postdoctoral associates, and doctoral candidates specializing in the assessment and treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders. All diagnosticians met internal certification and reliability procedures, developed in collaboration with one of the ADIS-IV-C/P authors: observing three complete interviews, collaboratively administering two interviews with a trained diagnostician, and conducting supervised interviews until achieving the reliability criterion (i.e., full diagnostic profile agreement on three of five consecutive supervised assessments). Demographic information was obtained from parent report. As in previous research (e.g., Merikangas et al., 2010), household income was used to compute a poverty index ratio (i.e., household income divided by U.S. poverty threshold in the interview year). All study procedure were approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Unidimensionality of SAD was first evaluated with confirmatory factor analysis. Then, a two parameter, logistic model was analyzed, estimating symptom thresholds and symptom discrimination. Xcalibre 4.1 (Guyer & Thompson, 2011) was used to estimate the models and examine DIF. DIF was assessed using the Mantel-Haenszel (MH) statistic, which produces an odds ratio contrasting the probability of symptom endorsement in a reference group (e.g., girls) to a focal group (e.g., boys). This odds ratio is then tested for a difference from 1 (i.e., equal odds of endorsement). DIF was assessed across sex (i.e., girls vs. boys), age (i.e., children younger than nine years versus children nine and older), and diagnostic status (i.e., children without an SAD diagnosis vs. children with a SAD diagnosis). Additionally, MH is often transformed using the formula delta(MH) = -2.35 * ln(MH) to yield a symmetric distribution centered on 0 (Holland & Thayer, 1988). Zwick and Ercikan (1989) proposed a measurement of the effect size of this transformation where an absolute value of delta(MH) less than 1 can be regarded as negligible, between 1 and 1.5 reflects moderate DIF, and over 1.5 reflects large DIF. Of note, the M-H coefficient cannot examine crossing DIF, where items are biased differentially at different levels of theta. Crossing DIF was examined using crossing SIBTEST (Li & Stout, 1996). This procedure is similar to the one used to examine DIF, with the exception that it assumes the DIF switches at some point in the severity range. For example, it would assume that at low levels of separation anxiety boys are more likely to endorse a symptom than girls, but that this switches at some point, such that at high levels of separation anxiety girls are more likely to endorse that symptom than boys.

Results

Rate of Symptom Endorsement

Rates of symptom endorsement for all participants by reporter, and when combined using the or rule, are provided in Table 1. Among children who were assigned a diagnosis of SAD, the following composite symptom endorsement frequencies were found: 1) distress related to separation, 94.8%; 2) worry about harm befalling attachment figure, 68.6%; 3) worry that untoward event will lead to separation, 60.5%; 4) reluctance/refusal to go places (e.g. school), 61.0%; 5) fear of being alone or without attachment figure, 89.5%; 6) reluctance to sleep away from major attachment figure, 85.5%; 7) repeated nightmares about separation, 29.7%; 8) physical symptoms associated with separation, 63.4%.

Table 1. Percent endorsement for symptoms of separation anxiety disorder by children and parents.

| DSM-IV SADa Symptoms | Child | Parent | Combinedb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Distress related to separation | 61.8 | 58.8 | 77.7 |

| 2. Worry about harm befalling attachment figure | 46.0 | 29.8 | 56.8 |

| 3. Worry that untoward event will lead to separation | 33.4 | 24.0 | 45.1 |

| 4. Reluctance/refusal to go places (e.g. school) | 25.1 | 30.9 | 43.7 |

| 5. Fear of being alone or without attachment figure | 50.1 | 51.8 | 71.9 |

| 6. Reluctance to sleep away from major attachment figure | 44.8 | 42.6 | 64.1 |

| 7. Repeated nightmares about separation | 14.2 | 9.2 | 19.8 |

| 8. Physical symptoms associated with separation | 28.1 | 34.5 | 47.1 |

Separation Anxiety Disorder

Symptom reports combined using the or rule. For parent-child concordance indices across separation anxiety disorder symptoms in the present sample, the interested reader is referred to Langer, Cooper-Vince, Pincus, and Comer (2013).

CFA

The initial CFA model demonstrated good fit, χ2 (20) =53.14, p < .001, CFI = .96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = .07. Modification indices did not indicate any relevant areas of strain. Standardized factor loadings ranged from -.489 (fear of harm befalling self or attachment figure,) to .882 (distress related to separation), and were all significant (range of zs = 7.76 – 18.87). Based on these results, a unidimensional model was pursued in subsequent analyses.

IRT Model

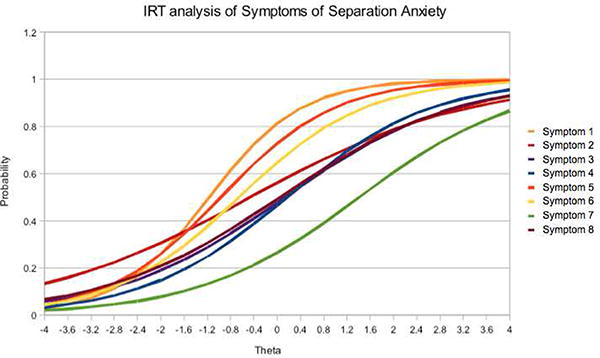

Across the eight core symptoms of SAD, distress related to separation from a major attachment figure and fear of being alone showed the highest discrimination properties (see Table 2). These symptoms also had the lowest thresholds, indicating that relative to the other SAD symptoms they are more likely to be endorsed at relatively low levels of the latent trait of separation anxiety. Repeated nightmares about separation had the highest threshold. Worry about harm befalling attachment figure showed the poorest discrimination between children at lower and higher levels of separation anxiety.

Table 2. Item discriminations and thresholds for symptoms of Separation Anxiety Disorder.

| DSM-IV SAD Symptoms | a(SE) | b(SE) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Distress related to separation | 1.26(.11) | -1.17(.09) |

| 2. Worry about harm befalling attachment figure | .53(.14) | -0.46(.14) |

| 3. Worry that untoward event will lead to separation | .68(.13) | .14(.11) |

| 4. Reluctance/refusal to go places (e.g. school) | .81(.12) | .18(.10) |

| 5. Fear of being alone or without attachment figure | 1.02(.11) | -0.97(.09) |

| 6. Reluctance to sleep away from major attachment figure | .93(.11) | -0.66(.09) |

| 7. Repeated nightmares about separation | .73(.11) | 1.41(.13) |

| 8. Physical symptoms associated with separation | .66(.13) | .05(.12) |

Note: Item discrimination (a), Item threshold (b)

Item discrimination and item threshold values were used to calculate ICCs, a visual depiction of symptom discrimination and threshold. As seen in Figure 1, the SAD symptoms varied across a range of severity (i.e., item threshold), from just over one standard deviation below the mean to almost one and one half standard deviations above the mean. While there was substantial overlap among some of the symptoms (e.g., worry that an untoward event will cause separation, refusal to go places, and somatic symptoms), the symptoms also show a very broad range of assessment within a clinical sample. Differences in the slopes of the curves reflect differences in the discrimination of each item, with steeper curves depicting stronger discrimination, and shallower curves depicting less precise discrimination. That is, a given change in SAD severity results in a large change in the probability of endorsement for a symptom with high discrimination (e.g., distress related to separation), whereas that same change in SAD severity results in less of an increase in the probability of endorsement for a symptom with lower discrimination (e.g., worry about harm befalling attachment figure; see Figure 1). These symptoms, while reflecting a range, have moderate to high discriminations across a range in thresholds (Dhamija, 2009).

Figure 1.

Item characteristic curves (ICCs) for symptoms of separation anxiety disorder. Symptom 1 (Distress related to separation), Symptom 2 (Worry about harm befalling attachment figure), Symptom 3 (Worry that untoward event will lead to separation), Symptom 4 (Reluctance/refusal to go places, e.g. school), Symptom 5 (Fear of being alone or without attachment figure), Symptom 6 (Reluctance to sleep away from major attachment figure), Symptom 7 (Repeated nightmares about separation), Symptom 8 (Physical symptoms associated with separation).

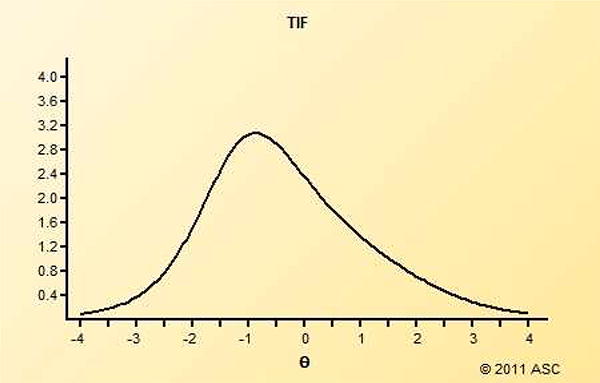

The TIC was broadly peaked (see Figure 2), with the maximum information falling .85 standard deviations below the mean. This yielded a standard error of estimation of .57, meaning that in this range we can estimate with a high level of precision (i.e., 68% of estimates at this severity level would fall within one standard deviation of this value, between .28 and 1.42, Baker, 2001). Additionally, this gradual peak shows that the eight symptoms of SAD assess the latent trait throughout a broad clinical severity range. SAD symptoms did not reflect a dichotomous cut-off, which would appear as a very sharply peaked curve. Rather SAD symptoms demonstrated an ability to measure precisely at many points in this range.

Figure 2. Test information Curve for separation anxiety disorder.

DIF

Statistically significant DIF was not found for any of the SAD symptoms, although several symptoms displayed large DIF effect sizes with respect to sex, age, and diagnostic status (see Table 3). When examining DIF with respect to sex, large effect sizes were displayed for reluctance to sleep away from an attachment figure (girls being more likely to experience this than boys), and nightmares about separation (boys being more likely to experience this than girls). When examining DIF with respect to age, large DIF effect sizes were displayed for distress related to separation and nightmares about separation (older children were more likely to experience both symptoms). With respect DIF as a function of diagnostic status, a large effect size was found for reluctance to sleep away from major attachment figures (this symptom was more likely to be present among children with a diagnosis of SAD, than without a diagnosis).

Table 3. DIF results by sex and age.

| Sex | Age | Diagnostic Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| DSM-IV SAD Symptoms |

M-H | Delta M-H |

M-H | Delta M-H |

M-H | Delta M-H |

| (SE) | (SE) | (SE) | ||||

| 1. Distress related to separation | 0.80 | 0.52 | 2.44 | -2.10 | 0.64 | 1.05 |

| (0.88) | (1.47) | (1.01) | ||||

| 2. Worry about harm befalling attachment figure | 0.93 | 0.17 | 0.59 | 1.24 | 1.18 | -0.38 |

| (0.60) | (0.61) | (0.69) | ||||

| 3. Worry that untoward event will lead to separation | 1.66 | -1.19 | 0.93 | 0.17 | 0.97 | 0.06 |

| (0.73) | (0.70) | (0.68) | ||||

| 4. Reluctance/refusal to go places (e.g. school) | 1.54 | -1.02 | 1.05 | -0.12 | 0.95 | 0.11 |

| (0.76) | (0.71) | (0.70) | ||||

| 5. Fear of being alone or without attachment figure | 0.76 | 0.65 | 1.28 | -0.58 | 0.85 | 0.39 |

| (0.75) | (1.02) | (0.84) | ||||

| 6. Reluctance to sleep away from major attachment figure | 2.33 | -1.99 | 0.67 | 0.94 | 0.52 | 1.52 |

| (0.93) | (0.78) | (0.70) | ||||

| 7. Repeated nightmares about separation | 0.30 | 2.83 | 2.00 | -1.63 | 0.94 | 0.15 |

| (0.67) | (0.96) | (0.84) | ||||

| 8. Physical symptoms associated with separation | 0.60 | 1.20 | 0.96 | 0.10 | 0.84 | 0.42 |

| (0.57) | (0.68) | (0.65) | ||||

Note:

=p>.05

M-H (Mantel-Haenszel)

Sex: reference group (boys), focal group (girls)

Age: reference group (< 9 years old), focal group (≥9 years old)

Diagnostic Status: reference group (children without an SAD diagnosis), focal group (children with an SAD diagnosis)

Crossing DIF

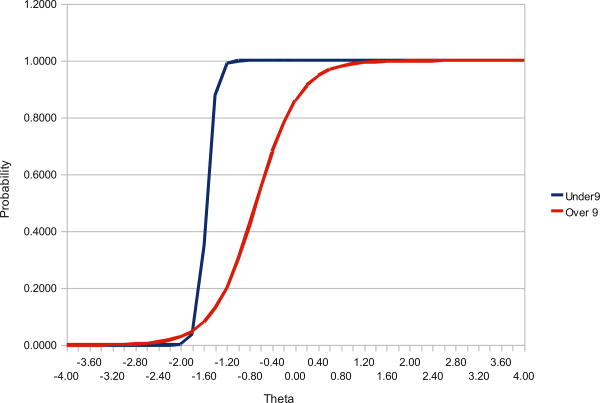

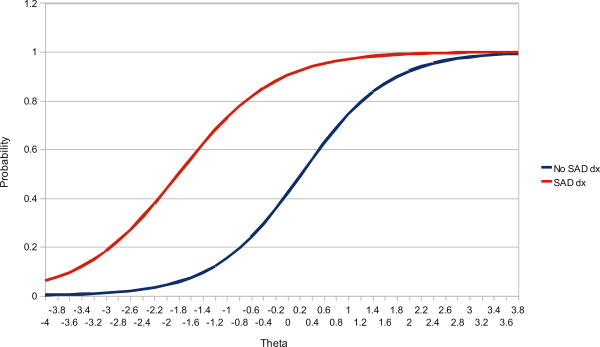

It is important to note that DIF measures likelihood of endorsing a symptom at a given severity of SAD. Therefore, we evaluated crossing DIF by age, sex, and SAD diagnostic status to determine whether the likelihood of endorsing a SAD symptom varied as a function of sex, age, or diagnostic status, and latent SAD severity. Among SAD symptoms, excessive fear at separation displayed crossing DIF due to age (see Figure 3). Specifically, at lower levels of separation anxiety an excessive fear at separation was more likely to be endorsed for children 9 and older; however, at higher levels of separation anxiety this symptom was more likely to be endorsed for children under 9 (Bcross = -0.119, p = .027). Significant crossing DIF due to diagnostic status was also observed for reluctance to go to sleep without attachment figure (see Figure 4; Bcross = -.211, p = .04). Across the majority of the range of latent separation anxiety, children with a diagnosis of SAD were more likely to experience reluctance to sleep without attachment figures. However, the point at which the DIF reverses and children experience the opposite pattern of symptom presence in relation to SAD diagnostic status, appears to fall in the upper range of latent SAD severity, but the precise level is not visible. Significant crossing DIF was not found with respect to sex for any other symptoms of SAD.

Figure 3.

Crossing differential item functioning for child's distress related to separation with respect to child age.

Figure 4.

Crossing differential item functioning for fear of sleeping away from major attachment figure with respect to SAD diagnostic status.

Discussion

The present findings advance our understanding of SAD and symptom functioning in several ways. First, within a clinical sample, the eight SAD symptoms together were shown to assess a broad range of sub-clinical and clinical separation anxiety severity, indicating that these eight symptoms are collectively well suited to accurately assess SAD along a broad severity continuum within clinic-referred samples. Seven of the eight symptoms of SAD were found to discriminate “moderately” well between children with higher and lower levels of separation anxiety, with worry about harm befalling attachment figures demonstrating low discrimination (Baker, 2001). Among these eight symptoms, distress related to separation and fear of being alone without major attachment figures were found to discriminate best between children with higher and lower levels of separation anxiety. Interestingly, these same two symptoms were found to have the lowest threshold for being endorsed, meaning that these symptoms have a 50% chance of being endorsed at the lowest severity of separation anxiety, relative to other SAD symptoms. This finding is consistent with previous work identifying these two symptoms as among the most frequently endorsed symptoms of SAD (e.g., Allen et al., 2010). The symptom with the poorest ability to discriminate between children with lower and higher levels of separation anxiety was the child's worry about harm befalling major attachment figure. Although this symptom may be somewhat common among SAD youth, it appears to offer relatively less diagnostic utility relative to the many of the other SAD symptoms. Additionally, the symptom with the highest threshold for being endorsed was nightmares about separation, which is also consistent with previous work identifying this symptom as the least commonly endorsed SAD symptom (e.g., Allen et al.).

Findings indicated that symptom threshold and discrimination values were largely robust across sex, age, and diagnostic status, supporting the broad application of the eight core symptoms to assess SAD across ages and sexes. However, the likelihood of endorsing distress related to separation did vary as a function of age and severity of latent separation anxiety. At lower levels of separation anxiety children 9 and older are more likely to reportedly experience this symptom, whereas at higher levels of separation anxiety children under 9 are more likely to reportedly experience this symptom. This finding may be explained by the fact that separation anxiety typically declines with age among community youth without anxiety disorders (Essau, Sakano, Ishikawa & Sasagawa, 2004), resulting in anxiety associated with separation in older youth being more developmentally atypical. Therefore, at lower levels of separation anxiety separation distress among younger children may not be viewed by parents and children as atypical, and therefore not reported as excessive during the assessment, whereas similar levels of separation anxiety would be reported as excessive anxiety symptoms for an older child. However, at higher levels of separation anxiety, parents and children may be more likely to identify the separation distress among young children as developmentally atypical and consequently endorse this as a symptom of separation anxiety. Further, as children's emotion regulation abilities improve with age (Murphy, Eisenberg, Fabes, Shepard, & Guthrie, 1999; Silvers et al., 2012), older children may be better able to cope with higher level separation anxiety and display less distress at separation, relative to younger children experiencing similarly high levels of separation anxiety, accounting for the lower likelihood of older children experiencing this symptom at higher levels of separation anxiety, relative to younger children.

In addition to distress related to separation, the likelihood of experiencing fear of sleeping away from attachment figures was also found to have significant crossing DIF by diagnostic status. However, graphical depictions of item threshold and discriminations based on diagnostic status revealed that over the majority of the range of separation anxiety severity, children with a SAD diagnosis were more likely to experience this symptom than children without a diagnosis. As the presence of a SAD diagnosis within this sample takes into account symptom presence and interference caused by these symptoms, it is not surprising that children with an SAD diagnosis are more likely to experience fear of sleeping away from attachment figures, as this symptom is likely to cause daily distress and interference in family routines at bed-time. However, further evaluation of this symptom is needed to determine at what point on the spectrum of latent separation anxiety severity children without a diagnosis of SAD are more likely to endorse this symptom.

Given the diagnostic properties of distress related to separation and fear of being alone without major attachment figures, these symptoms may be particularly well-suited for screening purposes when assessing SAD, due to their low threshold for endorsement but strong ability to discriminate between children with lower and higher severity SAD. Branching SAD assessment tools that assess these symptoms first, or use these symptoms as gate questions to the more extensive assessment of SAD, may be well positioned to maximize sensitivity and specificity without increasing patient burden with a more lengthy assessment. Future iterations of the diagnostic system may also do well to consider item threshold when devising symptom-count criteria. For example, rather than requiring any three of the eight core symptoms for diagnosis, the present findings suggest SAD symptoms might be grouped into high (i.e., nightmares about separation) and low threshold symptoms. A more empirical approach to SAD classification would require a fewer number of high threshold symptoms, relative to low threshold symptoms, for SAD diagnosis. For example, perhaps only requiring two high threshold symptoms for SAD diagnosis would reduce the high prevalence of anxiety disorder NOS diagnosis (Comer et al., 2012), which currently characterizes clinically significant anxiety presentations that do not meet full diagnostic criteria for a specified anxiety disorder but are nonetheless highly impairing. Lumping such interfering cases into the broad and heterogeneous category anxiety disorder NOS has serious implications for research and practice (Comer et al., 2012). Future work is needed to examine the clinical correlates associated with SAD presentations characterized by a small number (i.e., < 3) of high threshold symptoms. The manner in which such presentations of SAD may impact treatment course should also be evaluated to determine if SAD presentations characterized by lower threshold symptoms can be effectively treated in a shorter dose of treatment than presentations characterized by high threshold symptoms. Additionally, as child and parents reports were combined in the present study, future work in large epidemiologic samples would do well to evaluate item threshold and discrimination values as a function of informant (i.e., parent or child).

The present findings also lend preliminary support to the classification of SAD along a continuum of severity. However, future work is needed to directly compare continuous and dichotomous classifications of SAD, to determine whether SAD may be better classified along a continuum of severity, as other disorders (Asmundson, Weeks, Carleton, Thibodeau, & Fetzner, 2011; Carragher, Mewton, Slade, & Teesson, 2011; Ruscio, 2010).

The present findings must be considered in light of several study limitations. First, the current analyses were conducted with data collected with the ADIS-IV-C/P, a semi-structured interview with pre-established skip-out rules. As the present study only included participants who were assessed for all 8 symptoms, the range of separation anxiety included in the current sample was truncated, such that evaluations could compare high versus low separation anxiety, but not high versus no separation anxiety. The present findings, therefore, speak to the high-end specificity (Comer & Kendall, 2005) of separation anxiety symptoms by examining each symptom's discrimination properties among a relatively restricted range of severity. Consequently, the generalizability of the present findings to community children with no or few SAD symptoms may be limited. It is possible that future work examining SAD symptom utility in community samples reflecting a broader spectrum of separation anxiety (i.e., one also including cases with no separation anxiety at all) could yield alternative DIF values. The evaluation of data from community children may also yield higher item threshold values as well as increased discrimination parameters because of the broader continuum assessed. In such work, further information about SAD could also be gathered with the inclusion of questions about related features of SAD that are not current diagnostic criteria (e.g., aggressive behavior at separation). Second, although DIF values were largely nonsignificant in this clinical sample of 359 youth, it is nonetheless possible that findings might have differed given a larger sample, as several large effect sizes were found and large standard errors were observed for DIF analyses. Third, the study took place in a university-based metropolitan outpatient clinic specializing in the treatment of emotional disorders, and as such the findings may not be representative of youth presenting for treatment in other settings. Additionally, given the low proportion of anxious youth in the study below the age of seven, the present findings may not be representative of samples with larger proportions of very young children. To optimally inform an improved SAD taxonomy, future work is needed to evaluate the diagnostic utility of SAD symptoms in samples of youth representing the general population. Additionally, as different patterns of symptom expression have been found in other psychological disorders as a function of racial and cultural differences (Latzman et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011), differential SAD symptom functioning should also be explored with respect to different racial and ethnic groups. Given the racial and ethnic distribution of the present sample, the present analyses were not able to speak to such variations. Finally, as the current proposal for DSM-5 SAD is to eliminate the childhood-onset criterion (APA, 2012), future work is needed to evaluate differential item functioning across the entire lifespan. As preliminary work evaluating SAD in adulthood has identified two patterns of SAD onset—one persisting from childhood into adulthood and the second onsetting in adulthood (Pini et al., 2010; Pini et al., 2012; Shear et al., 2006)—future work is needed to evaluate how SAD symptoms may differentially function to inform these trajectories of SAD.

Despite these limitations, the current findings provide critical insight into the utility of SAD symptoms. Findings support the robustness of symptom utility across ages and sexes, with the exception of distress related to separation, for which symptom endorsement varied as a function of age and SAD severity. Although the findings also point to a dimensional classification of SAD in place of dichotomous classification, as proposals for DSM-5 retain the dichotomous present or absent classification of SAD, the current finding support a restructuring of SAD diagnostic criteria to reflect the range of item thresholds. Requiring a fewer number of high threshold symptoms, relative to low threshold symptoms for SAD diagnosis, may improve the identification of SAD treatment cases and enhance allocation of mental health services to children and families.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by K23 MH090247 (PI: Comer) and 3R01MH039096-24S1 (PI: Emmert-Aronson).

References

- Allen JL, Lavallee KL, Herren C, Ruhe K, Schneider S. DSM-IV criteria for childhood separation anxiety disorder: Informant, age, and sex differences. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24:946–952. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders text revision. 4th, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- APA. E 00 Separation Anxiety Disorder. DSM-V Development. 2012 from http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=118.

- Asmundson GJ, Weeks JW, Carleton RN, Thibodeau MA, Fetzner MG. Revisiting the latent structure of the anxiety sensitivity construct: more evidence of dimensionality. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25(1):138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker FB. The basics of Item Response Theory. 2nd. College Park, MD: ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(2):179–192. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carragher N, Mewton L, Slade T, Teesson M. An item response analysis of the DSM-IV criteria for major depression: Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;130(1-2):92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright-Hatton S, McNicol K, Doubleday E. Anxiety in a neglected population: prevalence of anxiety disorders in pre-adolescent children. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(7):817–833. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Temperament as a unifying basis for personality and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(4):505–521. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Gallo KP, Korathu-Larson P, Pincus DB, Brown TA. Specifying child anxiety disorders not otherwise specified in the DSM-IV. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29:1004–1013. doi: 10.1002/da.21981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Kendall PC. A symptom-level examination of parent-child agreement in the diagnosis of anxious youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(7):878–886. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000125092.35109.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Kendall PC. High-end specificity of the children's depression inventory in a sample of anxiety-disordered youth. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;22(1):11–19. doi: 10.1002/da.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhamija A. IRT – Item Response Theory. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/akdhamija/irt-dipr-1.

- Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Balsis S, Skodol AE, Markon KE, Hasin DS. An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: evidence from a national sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(1):282–288. doi: 10.1037/a0024780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Markon KE, Keyes KM, Skodol AE, Wall M, Grant BF. The structure and predictive validity of the internalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0029598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, Costello EJ, Angold A. School refusal and psychiatric disorders: A community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(7):797–807. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000046865.56865.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous X, Muñoz LC. Psychometric Properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) in Cypriot Children and Adolescents. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2013;29:19–28. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Sakano YY, Ishikawa SS, Sasagawa SS. Anxiety symptoms in Japanese and in German children. Behaviour Research And Therapy. 2004;42(5):601–612. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)001645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan F, Su L, Su Y. Anxiety structure by gender and age groups in a Chinese children sample of 12 cities. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2008;22:241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Foley DL, Rowe R, Maes H, Silberg J, Eaves L, Pickles A. The relationship between separation anxiety and impairment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(4):635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilder DA, Gizer IR, Ehlers CL. Item response theory analysis of binge drinking and its relationship to lifetime alcohol use disorder symptom severity in an American Indian community sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35(5):984–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grills-Taquechel AE, Fletcher JM, Vaughn SR, Stuebing KK. Anxiety and reading difficulties in early elementary school: evidence for unidirectional- or bi- directional relations? Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2012;43(1):35–47. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0246-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer R, Thompson NA. User's Manual for Xcalibre item response theory calibration software, version 4.1.3. St. Paul, MN: Assessent Systems Corporation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holland PW, Thayer DT. Differential item performance and the Mantel-Hanszel proedure. In: Wainer H, Braun HI, editors. Test validity. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney CA, Sims KE, Pursell CR, Tillotson CA. Separation Anxiety Disorder in Young Children: A Longitudinal and Family Analysis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(4):593–598. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3204_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Compton SN, Walkup JT, Birmaher B, Albano AM, Sherrill J, Piacentini J. Clinical characteristics of anxiety disordered youth. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24(3):360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossowsky J, Wilhelm FH, Roth WT, Schneider S. Separation anxiety disorder in children: Disorder specific responses to experimental separation from the mother. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(2):178–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02465.x. 10.1111/j.1469- 7610.2011 02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Externalizing psychopathology in adulthood: a dimensional-spectrum conceptualization and its implications for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(4):537–550. doi: 10.1037/0021-843.X.114.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Waldman ID, Loft JD, Hankin BL, Rick J. The structure of child and adolescent psychopathology: generating new hypotheses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(3):358–385. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenbucher JW, Labouvie E, Martin CS, Sanjuan PM, Bavly L, Kirisci L, Chung T. An application of item response theory analysis to alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine criteria in DSM-IV. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(1):72–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer L, Cooper-Vince C, Pincus DB, Comer JS. Using multiple reports in the diagnosis of childhood separation anxiety disorder: Evaluating the utility of alternative integration approaches. 2013 Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Latzman RD, Naifeh JA, Watson D, Vaidya JG, Heiden LJ, Damon JD, Young J. Racial differences in symptoms of anxiety and depression among three cohorts of students in the Southern United States. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2011;74(4):332–348. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2011.74.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz ER, Woolston J, Bar-Haim Y, Calvocoressi L, Dauser C, Warnick E, Leckman JF. Family Accommodation in Pediatric Anxiety Disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2012 doi: 10.1002/da.21998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Holm-Denoma JM, Small JW, Seeley JR, Joiner TE., Jr Separation anxiety disorder in childhood as a risk factor for future mental illness. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(5):548–555. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Stout W. A new procedure for detecting crossing DIF. Psychometrika. 1996;61:647–677. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz JD, Martin LY, Mannuzza S, Chapman TF. Childhood separation anxiety disorder in patients with adult anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151(6):927–929. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.6.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyneham HJ, Abbott MJ, Rapee RM. Interrater reliability of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent version. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(6):731–736. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180465a09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi G, Mucci M, Millepiedi S. Separation anxiety disorder in children and adolescents: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(2):93–104. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian ND, Godoy L, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS. Patterns of anxiety symptoms in toddlers and preschool-age children: evidence of early differentiation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26(1):102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BC, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Guthrie IK. Consistency and change in children's emotionality and regulation: A longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1999;45(3):413–444. [Google Scholar]

- Pini S, Abelli M, Shear KM, Cardini A, Lari L, Gesi C, Cassano GB. Frequency and clinical correlates of adult separation anxiety in a sample of 508 outpatients with mood and anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;122(1):40–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini S, Gesi C, Abelli M, Muti M, Lari L, Cardini A, Shear KM. The relationship between adult separation anxiety disorder and complicated grief in a cohort of 454 outpatients with mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenoveau JM, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Griffith JW, Epstein AM. Testing a hierarchical model of anxiety and depression in adolescents: a tri-level model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24(3):334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM. The latent structure of social anxiety disorder: consequences of shifting to a dimensional diagnosis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(4):662–671. doi: 10.1037/a0019341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear K, Jin R, Ruscio AM, Walters EE, Kessler RC. Prevalence and Correlates of Estimated DSM-IV Child and Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1074–1083. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. San Antonio, Texas: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pina AA. Test-Retest Reliability of Anxiety Symptoms and Diagnoses With the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvers JA, McRae K, Gabrieli JD, Gross JJ, Remy KA, Ochsner KN. Age-Related Differences in Emotional Reactivity, Regulation, and Rejection Sensitivity in Adolescence. Emotion. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0028297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skapinakis P, Anagnostopoulos F, Bellos S, Magklara K, Lewis G, Mavreas V. An empirical investigation of the structure of anxiety and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: cross-sectional study using the Greek version of the revised Clinical Interview Schedule. Psychiatry Research. 2011;186(2-3):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SH. A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1998;36:545–566. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Thissen D. Item response theory. In: Comer JS, Kendall PC, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Research Strategies for Clinical Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sterba SK, Copeland W, Egger HL, Jane Costello E, Erkanli A, Angold A. Longitudinal dimensionality of adolescent psychopathology: testing the differentiation hypothesis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:871–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland J, Keller J, Lavigne JV, Gouze K, Hopkins J, LeBailly S. The structure of psychopathology in a community sample of preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:601–610. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland M, Hobbs MJ, Andrews G, Craske MG. Assessing DSM-IV symptoms of panic attack in the general population: An item response analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton KE, Ormel J, Krueger RF. The dimensional nature of externalizing behaviors in adolescence: evidence from a direct comparison of categorical, dimensional, and hybrid models. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(4):553–561. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9478-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock LM, Strong D, Uebelacker LA, Miller IW. Differential item functioning of DSM-IV depressive symptoms in individuals with a history of mania versus those without: an item response theory analysis. Bipolar Disorder. 2009;11(3):289–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Versions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31(3):335–342. doi: 10.1207/153744202760082595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Wang M. Developmental characteristics of preschoolers' anxiety. Chinese Journal Of Clinical Psychology. 2009;17:723–725. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Dere J, Zhu X, Yao S, Chentsova-Dutton YE, Ryder AG. Anxiety symptom presentations in Han Chinese and Euro-Canadian outpatients: is distress always somatized in China? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;135(1-3):111–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolog TC, Ballabriga MCJ, Bonillo-martin A, Canals-sann J, Hernandezmartinez C, Romero-acosta K, Domenech-llaberia E. Somatic complaints and symptoms of anxiety and depression in a school-based sample of preadolescents and early adolescents Functional impairment and implications for treatment. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies. 2011;11(2):191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zwick R, Ercikan K. Analysis of differential item functioning in the NAEP history assessment. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1989;26(1):55–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3984.1989.tb00318.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]