Abstract

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis that occurs both as a primary disorder as well as secondary to an underlying disease. Due to its low prevalence there are limited data on therapeutics, particularly in refractory cases. Here, we discuss a case successfully managed with intravenous immunoglobulin and review the supporting literature.

Key words: Intravenous immunoglobulin, Treatment, Pyoderma gangrenosum

Case Report

A 36-year-old woman presented with a 12 × 6 cm ulcer on her right leg (fig. 1). She stated that it had been present for 8 years and denied any history of malignancy, ulcerative colitis or rheumatic disease. Biopsy was diagnostic of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) and prednisone 40 mg daily was initiated. Due to incomplete response, she required several steroid-sparing agents, including dapsone, methotrexate, cyclosporine, mycophenolate, infliximab, adalimumab and azathioprine. Despite this, the ulcers persisted and the prednisone could not be tapered below 20 mg daily. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) at 2 g/kg monthly was initiated with nearly complete improvement (fig. 2). The prednisone was tapered to 5 mg daily and IVIG was tapered to 2 g/kg every 12 weeks. She has since done well on azathioprine and low-dose prednisone and has had no recurrent lesions.

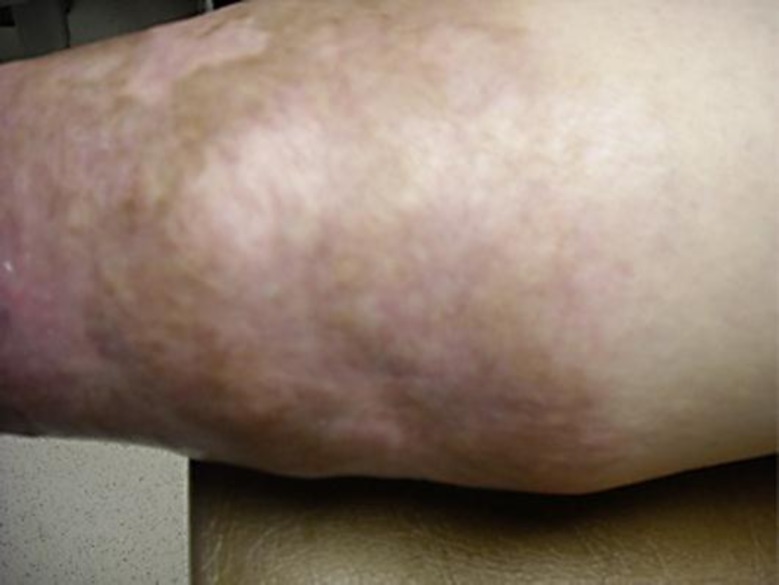

Fig. 1.

PG lesion prior to IVIG therapy.

Fig. 2.

PG lesion post IVIG therapy.

Discussion

PG has an annual incidence of 3–10 per million persons, most commonly presents between 20 and 50 years of age and is more common in women. It is characterized by a neutrophilic infiltrate that is believed to be due to dysregulation of neutrophil function and altered innate immune responses. It frequently presents as painful ulcers that often follow surgery or trauma and is commonly misdiagnosed as infectious or ischemic lesions [1].

Initial therapy consists of corticosteroids, although steroid-sparing agents have been used, including dapsone, minocycline, methotrexate, cyclosporine, mycophenolate and TNFα inhibitors. IVIG is typically used after other treatments have failed. Careful wound care and avoidance of debridement and surgery is key [1].

We reviewed 20 cases of IVIG therapy in PG that are described in table 1 and table 2. Table 1 describes 13 cases that were treated with IVIG 2 g/kg (except for two in whom the dose was 1.5 and 2.5 g/kg, respectively). 12 of these achieved complete or nearly complete remission; 2 had disease recurrence that required repeated courses of IVIG. Both instances of recurrent disease responded to repeat treatment with IVIG. Table 2 describes 7 patients treated with lower-dose IVIG (0.5 g/kg). All had major or complete response, though all required continued corticosteroids, with 4 requiring additional immunosuppressive therapy.

Table 1.

Thirteen cases of IVIG therapy in PG (all IVIG courses were 2 g/kg unless noted otherwise)

| Age, gender, ref. | Notable past medical history | Initial therapy | Initial IVIG courses | Initial response | Relapse | Therapy during IVIG treatment | Number of further IVIG courses | Subsequent response | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35, F [2] | insect bite | PRD, DAP, CBT, TAC, CSA, MPD | 2 (2 weeks apart) | nearly complete | no | PRD, CSA | none | N/A | clear at 8 months |

| 48, M [3] | adrenal carcinoma, pemphigus vulgaris | PRD, MMF, CSA, DEX, THL | 1 | complete | yes | PRD, MMF | yes, 1 course | complete | clear at 5 months |

| 17, F [3] | none noted | PRD, MPD, MMF, CSA | multiple (number and interval not given) | nearly complete | yes | CSA, MMF | yes | complete | clear at 15 months |

| 37, F [4] | none noted | PRD, CSA | 4 (monthly) | complete | no | PRD | none | N/A | clear at 4 months |

| 55, M [5] | Ph+ CML | PRD, MCN, DAP, AZA, MMF, SSKI, CSA | 3 (monthly) | complete | no | PRD | yes, indefinite | complete | clear at 8 months |

| 81, M [6] | trauma | CSA | 6 (monthly) | significant | no | MPD | none | N/A | clear at 7 months, then died of cardiac arrest |

| 58, M [7] | prostate carcinoma | PRD, MCN | 6 (monthly) | significant | no | PRD | none | N/A | stable at 12 months |

| 66, M [7] | CMML | BTM, TAC, PRD | 6 (monthly) | significant | no | PRD | none | none | stable at 6 months |

| 83, M [8] | none noted | CBT, MCN, PRL | 5 (monthly) | significant | no | none | yes, 5 courses (bi-monthly) | complete | stable at 15 months |

| 61, F [9] | RA, insect bite | PRD | 3 (monthly) | marked | no | PRD | no | N/A | stable (unknown) |

| 62, F [10] | none noted | CSA, GC | 4 (monthly)a | complete | no | PRD | no | N/A | stable at 12 months |

| 61, M [11] | MDS | PRL, MPD | 2 (monthly) | marked | no | PRL, PRD | no | N/A | stable at 3 months |

| 26, F [12] | twin pregnancy | DAP, MPD | 4 (monthly)b | significant | no | MPD | no | N/A | stable (unknown) |

The authors defined all clinical responses – there is no uniform standard for clinical response in PG.

AZA = Azathioprine; BTM = betamethasone (topical); CBT = clobetasol (topical); CMML = chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; CSA = cyclosporine A; DAP = dapsone; DEX = dexamethasone; GC = glucocorticoid (drug/route not specified); MCN = minocycline; MDS = myelodysplastic syndrome; MMF = mycophenolate mofetil; MPD = methylprednisolone; Ph+ CML = Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia; PRD = prednisone; PRL = prednisolone; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; SSKI = potassium iodide; TAC = tacrolimus (topical); THL = thalidomide.

IVIG course 2.5 g/kg.

IVIG course 1.5 g/kg.

Table 2.

Seven cases of IVIG therapy (0.5 g/kg) in PG (all data are from Kreuter et al. [13])

| Age, gender | Associated disease | Concurrent immunosuppression | Treatment response |

|---|---|---|---|

| 47, F | ankylosing spondylitis | SGC | complete |

| 63, F | monoclonal gammopathy (IgA) | SGC, MMF, CSA | complete |

| 31, M | ankylosing spondylitis | SGC, AZA, IFX | complete |

| 79, F | monoclonal gammopathy (IgA) | SGC | complete |

| 40, F | ulcerative colitis | SGC | major |

| 49, F | ulcerative colitis | SGC, AZA, CSA | major |

| 81, F | ulcerative colitis | SGC, CSA | complete |

The authors defined all clinical responses – there is no uniform standard for clinical response in PG.

AZA = Azathioprine; CSA = cyclosporine A; IFX = infliximab; MMF = mycophenolate mofetil; SGC = systemic glucocorticoids.

Based on this case and our review of the literature, we believe that IVIG is a useful therapeutic option in refractory PG and can be considered in cases of resistance to or intolerance of standard immunomodulatory therapy.

This work was conducted at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, USA.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no conflict on interest. There was no funding source.

References

- 1.Ruocco E, Sangiuliano S, Gravina AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1008–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta AK, Shear NH, Sauder DN. Efficacy of human intravenous immune globulin in pyoderma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:140–142. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummins DL, Anhalt GJ, Monahan T, Meyerle JH. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with intravenous immunoglobulin. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1235–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dirschka T, Kastner U, Behrens S, Altmeyer P. Successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with intravenous human immunoglobulin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:789–790. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Zwaan SE, Iland HJ, Damian DL. Treatment of refractory pyoderma gangrenosum with intravenous immunoglobulin. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:56–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2008.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagman JH, Carrozzo AM, Campione E, Romanelli P, Chimenti S. The use of high-dose immunoglobulin in the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2001;12:19–22. doi: 10.1080/095466301750163527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer N, Ferraro V, Mignard MH, Adamski H, Chevrant-Breton J. Pyoderma gangrenosum treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins: two cases and review of the literature. Clin Drug Investig. 2006;26:541–546. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200626090-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suchak R, Macedo C, Glover M, Lawlor F. Intravenous immunoglobulin is effective as a sole immunomodulatory agent in pyoderma gangrenosum unresponsive to systemic corticosteroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:205–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinnya S, Hamza S. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the breast treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;7:64–68. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2013.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang XB, He YQ, Zhou H, Luo Q, Li CX. A case of pyoderma gangrenosum responding to high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Chin Med J (Engl) 2006;119:1230–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamaki K, Nakazawa T, Mamehara A, Tsuji G, Saigo K, Kawano S, Morinobu A, Kumagai S. Successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum associated with myelodysplastic syndrome using high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Intern Med. 2008;47:2077–2081. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erfurt-Berge C, Herbst C, Schuler G, Bauerschmitz J. Successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with intravenous immunoglobulins during pregnancy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16:205–207. doi: 10.1177/120347541201600314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreuter A, Reich-Schupke S, Stucker M, Altmeyer P, Gambichler T. Intravenous immunoglobulin for pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:856–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]