Abstract

Detailed control over the structural organization of scaffolds and engineered tissue constructs is a critical need in the quest to engineer functional tissues using biomaterials. This work presents a new approach to the spatial direction of endothelial tubulogenesis. Micropatterned fibronectin substrates were used to control lung fibroblast adhesion and growth and the subsequent deposition of fibroblast-derived matrix during culture. The fibroblast-derived matrix produced on the micropatterned substrates was tightly oriented by these patterns, with an average variation of only 8.5°. Further, regions of this oriented extracellular matrix provided directional control of developing endothelial tubes to within 10° of the original micropatterned substrate design. Endothelial cells seeded directly onto the micropatterned substrate did not form tubes. A metric for matrix anisotropy showed a relationship between the fibroblast-derived matrix and the endothelial tubes that were subsequently developed on the same micropatterns with a resulting aspect ratio over 1.5 for endothelial tubulogenesis. Micropatterns in “L” and “Y” shapes were used to direct endothelial tubes to turn and branch with the same level of precision. These data demonstrate that anisotropic fibroblast-derived matrices instruct the alignment and shape of endothelial tube networks, thereby introducing an approach that could be adapted for future design of microvascular implants featuring organ-specific natural matrix that patterns microvascular growth.

Keywords: Extracellular Matrix, Anisotropy, Endothelial morphogenesis, micropattern substrate

1. INTRODUCTION

The structural organization of cells and their extracellular matrix (ECM) in native tissue is critical for proper tissue function [1]. Many biomimetic materials have an isotropic structure with identical properties in all directions. However, tissues such as arteries [2, 3], myocardium [2], musculoskeletal tissue [4], and the central nervous system [5] require anisotropic, or directional, organization for proper function or regeneration. In vascular tissue engineering, the development of functional arterial grafts has been challenged by the need to reproduce the unique, anisotropic mechanical properties of native vessels. Microvascular network organization is critical to the provision of sufficient nutrient and waste exchange within metabolically active tissues, and to the development of complex, three-dimensional tissue engineered organs in which these functions cannot be served by diffusion alone [6]. Additionally, the pursuit of microvascular engineering is valuable because mimicking native tissue architecture may provide approaches to both creating functional tissue replacements and to gaining insight into the ability of extracellular matrix organization to direct complex multicellular organization during tissue morphogenesis.

The physical and biochemical properties of biomaterials can modulate cell-matrix adhesions and therefore affect cell responses such as morphology, differentiation, morphogenesis, and proliferation [7-11]. However, many popular synthetic scaffolds used in tissue engineering do not contain specific organizational cues to guide tissue development [2]. Extracellular matrices secreted by cells are an alternative to synthetic materials. Both cell sheet engineering, which consists of sheets of cells and their associated ECM, and decellularized cell-derived matrices have arisen as attractive approaches in tissue engineering [2, 12, 13]. Dense fibrous networks of extracellular matrix proteins can be produced by cells and remain intact after cell extraction [12, 14, 15]. Unlike synthetic scaffolds whose organization can be controlled through fabrication techniques, the cell-derived matrices’ structural organization is controlled by the cells. Engineering the directionality of these three-dimensional cell-derived extracellular matrices is a highly desirable means for creating complex structures from natural, cell-derived materials.

Some previously used techniques for creating patterned substrates include controlling cell adhesive regions [16-18] and surface topography [2, 5, 19, 20]. Cells are able to read and interpret these spatial cues, which direct cell morphology and functions such as adhesion, migration, and apoptosis [16, 17, 21-26]. The anisotropy of the cells is an important metric that has been evaluated in response to these substrates. Manwaring et al. utilized topographical patterns to direct meningeal cell cytoskeleton elements and cellular fibronectin fibril orientation [5]. However, the effectiveness of micropatterned substrates for directing cellular fibronectin fibrillogenesis has not yet been examined. Fibroblasts can produce three-dimensional network of extracellular proteins and proteoglycans. Some of the components include fibronectin, tenascin-C, collagen I, IV, and VI, decorin, and veriscan [12]. The average thickness of the lung fibroblast-derived matrix cultured for 7 days has previously been reported to be 5± 0.4 μm [27]. The present study examined the ability of two dimensional micropatterned substrates to direct the formation of three-dimensional cell-derived ECM.

The ECM produced by human lung fibroblasts is an attractive system because it promotes endothelial tubulogenesis without the addition of specialized growth factors [12, 27]. Further, natural cell-derived matrices preserve the fibrillar topography found in natural tissues, and may directly address issues of immune incompatibility that are inherent in the use of synthetic biomaterials [28]. In the current study, fibronectin substrates were micropatterned and used to test the hypotheses that substrate design could control the orientation of the fibroblasts, fibroblast-derived matrix, and subsequent endothelial tube formation. The alignment of cultured fibroblasts was directed by the patterned fibronectin. A metric for anisotropy using autocorrelation analysis demonstrated that the fibroblast-derived matrix produced after 7 days of culture on the micropatterned substrates was oriented by the substrate pattern. Regions of anisotropic ECM provided directional control of developing endothelial tubes. Fibroblasts also assembled matrix that conformed to “L” and “Y” shaped micropatterns, and these matrices provided cues to endothelial cells that resulted in the formation of tubes with similar shapes. The micropatterns studied were successful at directing endothelial tube orientation and branching, and they have the potential for modifications toward the production of more complex tube structures.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Cell Culture and Reagents

WI-38 human fetal lung fibroblasts (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in Minimal Essential Medium Eagle (Cellgro/Mediatech, Manassas, VA) with 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologics, Lawrenceville, GA), antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California), 1mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and non-essential amino acids (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) from VEC Technologies (Rensselaer, NY) were cultured in MCDB-131 Complete Medium (VEC Technologies).

2.2 Micropatterned Substrates

Fibronectin micropatterned substrates were obtained from Intelligent Substrates, Inc (Baltimore, MD). Parallel lines of fibronectin (1 μg/cm3), which were 15 μm wide with a pitch (inter-line spacing) of 30 μm, were patterned on 25 mm round photo-etched (on the backside) glass coverslips (No. 1, Bellco, Vineland, NJ). The line thickness and pitch were determined optimal for WI38 attachment to the micropatterns in preliminary studies (data not shown). On each coverslip there were four distinct regions: vertical lines, a transition region, horizontal lines, and the non-patterned outside region (Figure 1 a, c, e). No differences in the transition region and the non-patterned region were observed in cell and matrix alignment, therefore the transition region was not investigated further here. Pattern coverslips containing “L” and “Y” shapes were composed of 12 lines of fibronectin with the same line width and pitch described above. The angle of the branch point in the “Y” shape was 40°. Custom glass-bottom p35 petri-dishes were created with these pattern coverslips, sealed with 20:1 Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer (Dow Corning, Midland, MI), and used for cell culture.

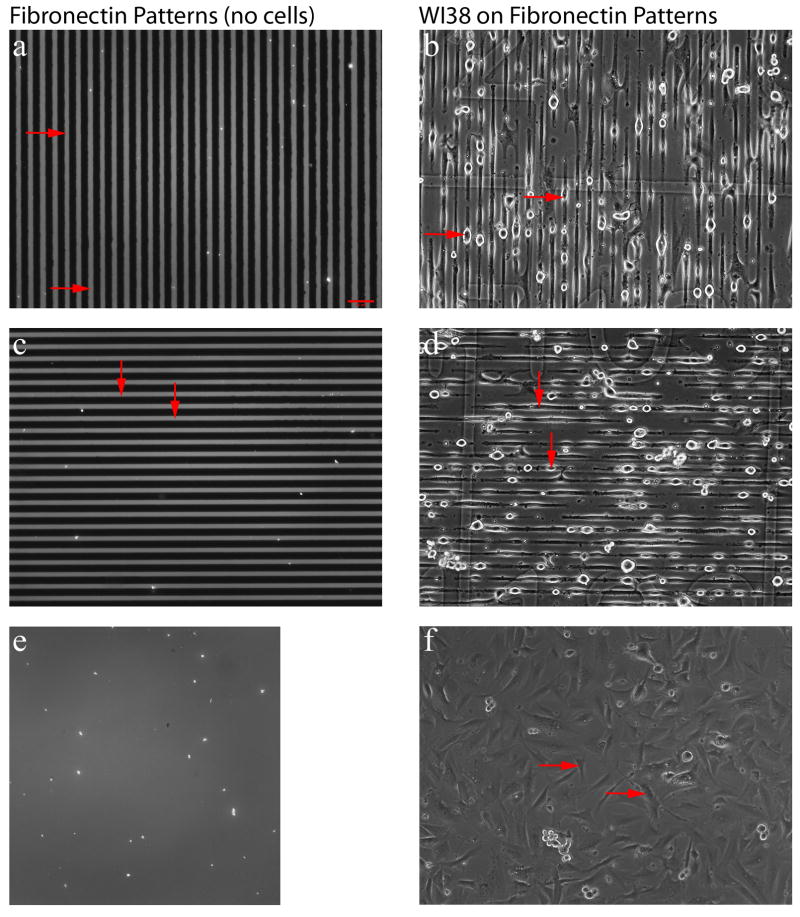

Figure 1. Patterned Fibronectin and WI38 Response.

A micropatterned coverslip (with no cells seeded) was labeled for epifluorescence imaging using an anti-fibronectin antibody (a, c, e). The images shown correspond to the three regions examined in this study: vertical parallel lines (a), horizontal parallel lines (c), and the nonpatterned region (e). The red arrows in a and c denote the regions containing fibronectin. WI38 cells were seeded onto patterned substrates in serum free conditions and phase contrast images were collected at 2.5 hours (b, d, f). Representative phase contrast images of the cell attachment to the vertical region (b), horizontal region (d), and outside region (f) are displayed. The red arrows in b and d highlight regions where cells are attached and conformed to the parallel line patterns. The arrows in f identify cells adhered to the non-patterned region. Scale bar = 65 μm (panel a).

2.3 Fibroblast-Derived Matrix Preparation

Prior to seeding the fibroblasts, the patterned areas of the coverslips were blocked with 1% casein from bovine milk (Sigma) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Quality Biological Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) for 1 hour to inhibit nonspecific binding of fibroblasts to regions that did not contain fibronectin. Surfaces were then washed three times with MEM media without additives. Confluent WI38 cells between passage 2-8 were trypsinized and suspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Sigma) with 1 mg/ml turkey egg white trypsin inhibitor (Sigma), and seeded onto patterned substrates at a density of approximately 1×105 cells per cm2 (35 mm petri dish). After 2.5 hours, the medium was changed to the standard WI38 culture media mentioned above. The fibroblasts were cultured in these conditions for 7 days, which allowed for production of extracellular matrix as previously described [12].

Fibroblast-derived matrices were decellularized as previously described [12]. Briefly, samples were incubated with 0.05% Triton X-100 (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and 50 mM NH4OH (Sigma). They were then washed with 50 mM NH4OH, incubated with 20 U/mL DNase I (Roche, Penzberg, Germany), gently washed with PBS and stored overnight at 4°C.

2.4 Endothelial Tube Formation Assay

Our group has previously shown that HUVEC seeded on the fibroblast-derived matrix, remodel the matrix and form networks of tubes within 24 hours without exogenous growth factors [12]. For tube formation experiments, HUVEC between passages 4-7 were seeded onto the fibroblast-derived matrix at a density of 2.1 × 105 cells/cm2 and were fixed with paraformaldehyde (see 2.6) for epifluorescence analysis after 24 hours.

2.5 Phase Contrast Images

Phase contrast images were captured using an epifluorescence Nikon TE200 microscope (Melville, NY) with a 10x objective, a Coolsnap HQ CCD camera (Roper, Duluth, GA), and Openlab software (Perkin Elmer/Improvision, Lexington, MA). In order to track the sample alignment when mounting it on the microscope, all images (including WI38 taken 2.5 hours after seeding, decellularized matrices, and HUVEC tubes) contained etched grid lines. The images of WI38 2.5 hour post-seeding were used to measure the alignment of the pattern relative to the grid lines. Using the initial measurements of relative grid-pattern location, the orientation of matrix fibrils and endothelial tubes was monitored. The boundaries of the pattern regions were also identified at the time that the 2.5 hour images were obtained.

2.6 Immunofluorescence

Decellularized fibroblast-derived matrices were labeled with 10 μg/ml of the amine-reactive probe, Alexa Fluor 488 carboxylic acid, succinimidyl ester (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), for 2 hours at room temperature. The matrices were then washed three times with PBS and imaged in PBS. Four locations within each pattern region of 2 different samples were examined.

HUVEC tube samples were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 20 minutes and then incubated with 0.5% Triton X-100 in paraformaldehyde for 2 minutes. Antibodies were diluted in 0.1% BSA and were incubated for 30 minutes. Fluorosave (CalBioChem, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to mount a large coverslip over the sample area. Rabbit polyclonal anti-fibronectin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used to label patterned coverslips without cells as well as coverslips with HUVEC tubes. Affinity cross-adsorbed Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was used as a secondary antibody for fibronectin labeling (Invitrogen). Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin and DAPI (Invitrogen) were used to label the HUVEC F-actin and nuclei, respectively. Five locations in each of four samples were analyzed for each pattern that was examined.

2.7 Image Analysis

Images of amine-labeled matrices and F-actin-labeled HUVEC tubes were analyzed in ImageJ (NIH, version 1.37) (Supplemental Figure 1). With the focus of investigating the endothelial response to anisotropic fibroblast-derived matrix, the HUVEC F-actin images were selected for analysis of endothelial cell anisotropy. All images were converted to 8 bit grey scale format and cropped in the center of the image to 1024 × 1024 pixels. Cropping to dimensions that are an integer power of 2 greatly improves the computational efficiency of fast Fourier transformations (by a factor of >104), and is therefore the state of the art approach to data preparation [29, 30]. To quantify anisotropy an autocorrelation function was computed for each image. Images with significant anisotropies produced a center peak that was ovoid, while isotropic images produced a circularly symmetrical center peak. A measure of the asymmetry in the autocorrelation peak was then computed, using a thresholded (at half maximum) image of the autocorrelation function, by dividing the long axis of the peak by the short axis. This produced a vector for which the magnitude was a dimensionless number that was 1 for an isotropic image and greater than 1 for anisotropic images, while the angle of the vector reflected the orientation of the major axis relative to the point of reference. Orientation angles were adjusted for alignment relative to the original pattern from phase images, such that the patterned fibronectin lines were at 0° and 90°. The anisotropy computation was automated using Matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). The deviation from the original fibronectin micropattern was calculated by subtracting the measured orientation angles from the from the original micropattern angle (0° or 90°). Angle measurements of the WI38 cells, ECM fibrils, and endothelial tubes formed in regions with “L” and “Y” micropatterns were captured in Image J. The angle of the each feature was measured independently at least 3 times.

When image z-stacks were captured using an epifluorescence Nikon TE200 microscope with a 40x objective compared to the single plane images collected with a 10x objective. All z-stacks were taken with 0.2 μm step size. The individual plane images were deconvolved with Huygens deconvolution software using the classic maximum likelihood estimation algorithm. Three-dimensional reconstructions were deconvolved with Huygens classic maximum likelihood estimation algorithm at 100-150 iterations and with a signal to noise ratio of 35 for the ECM proteins, 50 for nuclei, and 60 for actin. They were visualized with Volocity software (Perkin Elmer/ Improvision, Lexington, MA).

2.8 Statistics

GraphPad Prism version 4.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego California) ANOVA and Bonferroni post tests were used to analyze the aspect ratio data sets. One sample t-tests were used to compare the deviations of the fibroblast-derived matrix and the endothelial tubes from the original micropattern. Unpaired Student t-tests were used to evaluate the difference in preferred orientation of the fibroblast-derived matrix to the endothelial tubes in the vertical and horizontal patterned regions. Normality of the data was tested and passed the D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test in Prism. All reported data represent the mean values and standard errors of the mean. Significance was considered to be present at p<0.05 for all data.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Fibroblast Response to Pattern Substrate

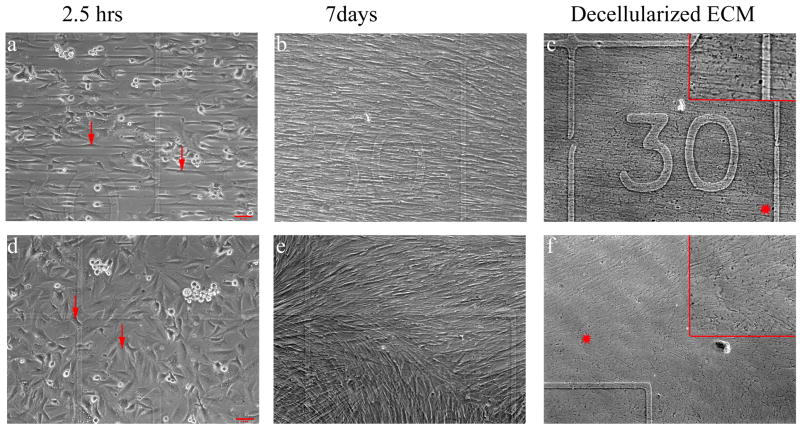

WI38 cells attached to the patterned coverslips in 2.5 hours in serum-free conditions. The original micropattern for the vertical, horizontal, and non-patterned outside region are shown in Figure 1 a, c, e, respectively. The orientation and spacing of the cells in pattern regions corresponded closely to the fibronectin patterned lines prior to seeding (Figure 1 b, d, f). The cells adhered in the patterned region spread along the patterned fibronectin lines, while those on the non-patterned region were polarized in many directions. After the cells adhered (Figure 2 a and d), the media was changed, and they were cultured in standard culture medium for 7 days. During this time cells remained aligned to the original patterns despite overgrowing the spacing of the lines patterned in the substrates, and they formed a dense monolayer (Figure 2 b and e). The cells were able to be extracted from the micropatterned coverslip, leaving the fibroblast-derived matrix to be investigated (Figure 2c and f). Additional phase contrast images collected at different time points over the 7 days of culture are included in Supplemental Figure 1. The alignment was uniform over the entire patterned area. This uniform alignment over a large area was not observed in the non-patterned regions. The ECM fibril alignment appeared to correspond with the WI38 alignment prior to extraction.

Figure 2. Fibroblasts on Patterned Substrate Over Time.

Phase contrast images of WI38 cells on a horizontal pattern region (a, b, c) and a non-patterned region (d, e, f) after different times of culture are shown. Approximately the same location on the coverslip is shown for all images of the same sample. The etched number 30 is seen in a-c, and the same etched corner is seen in d-f. The left images (a, d) display the initial cell attachment to the coverslip after 2.5 hours, while the middle images (b, e) show a confluent monolayer of cells observed after 7 days of culture. The red arrows denote cells in these images. The fibroblasts were then extracted and the fibroblast-derived matrix was examined (right images, c, f). Inserts contain 1.5x magnification of matrix fibrils in the region marked with an *. The cells and their extracellular matrix maintained the horizontal alignment provided by the micropatterned lines (b, c). The same was true for vertical lines (data not shown). In the non-pattern region, the cells and their matrix aligned to some extent (e, f). However, the alignment is not uniform over the entire area. Scale bar = 65 μm.

3.2 Alignment of the Fibroblast-Derived Matrix

The persistent alignment of the fibroblasts suggested that the extracellular matrix produced by WI38 cells might also be aligned with the original fibronectin micropattern. To address this question a cell-derived matrix was prepared, and the anisotropy in this matrix was examined quantitatively. After the fibroblasts were removed, amine probe-labeled fibroblast-derived matrices were used to visualize the infrastructure of the total matrix protein components using the etched regions of the coverslip as markers for the different patterned regions. Anisotropy analysis described in the methods section was applied to images collected (Figure 3 a, b, c).

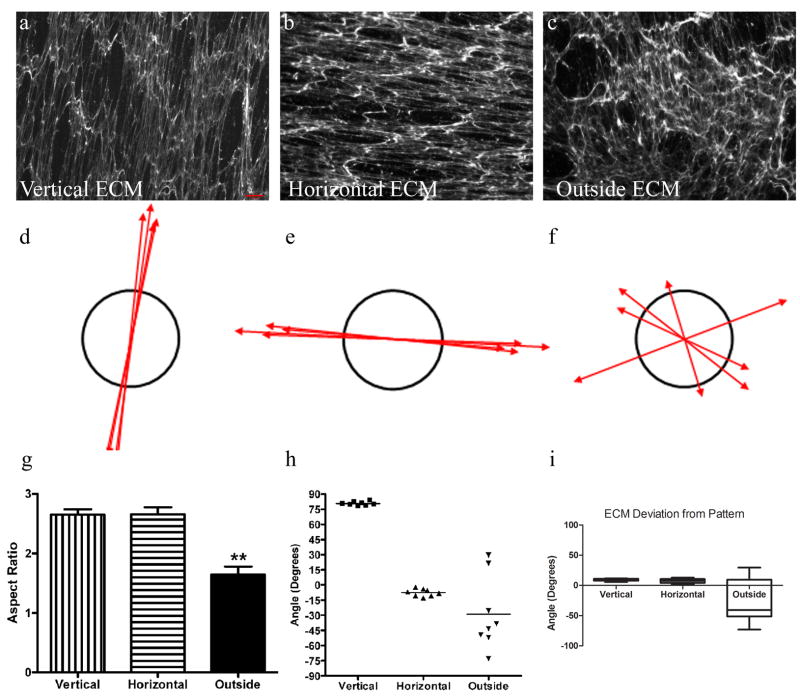

Figure 3. Fibroblast-Derived Matrix in Linear Patterned Regions.

Representative ECM produced by fibroblasts from vertical patterned (a), horizontal patterned (b), and non-patterned (c) regions are shown. Scale bar = 65 μm (panel a). Vector plots of the anisotropy metric and angles were represented in d-f. The average anisotropy of the fibroblast-derived matrix for the three regions examined here is shown in g. Both the vertical and horizontal pattern regions had significantly larger anisotropies than the outside region. ** indicates p<0.001. The preferred orientations are shown in h. Each dot represents a data point and the lines represent the mean angle for each region. The box and whiskers graph in i represents the angle of deviation in preferred orientation of the fibroblast-derived matrix fibrils from the original micropattern.

The anisotropies and orientations of the ECM produced by fibroblasts in each of the differently patterned regions were displayed as vector plots that highlight the large variation in the angles of orientation seen in the matrix produced by fibroblasts that were adherent to non-patterned regions as compared with matrix produced by fibroblasts in patterned regions (Figure 3 d, e, f). The length of the vectors corresponds to the anisotropy magnitude, and the vector angle is the major axis orientation. A circle represents an anisotropy measurement of 1, and denotes an isotropic condition. Four microscopic fields were examined for each pattern. With an anisotropy of 2.7 ± 0.09 for vertical pattern and 2.7 ± 0.10 for the horizontal pattern, the patterned regions had significantly higher anisotropy than the non-patterned region (1.6 ± 0.14, p<0.001) (Figure 3 g). The higher anisotropies indicated persistence of the ECM fibrils. The major axis orientation was then examined in matrix produced in each of the three patterned regions (Figure 3 h). The average angle of extracellular matrix relative to the original micropattern for the vertical region was 81 ± 0.68°, the horizontal region was -7.5 ± 1.3°, and the outside region was -29° ± 13°. The finding that patterned regions had an average orientation close to the original micropattern (vertical 90° and horizontal 0°, respectively) indicated that substrate pattern was translated to the matrix alignment by the fibroblasts. The deviation from the original micropatterns was calculated (Figure 3 i). The average deviation of the ECM from a micropattern patterned region (horizontal and vertical) was 8.5±0.8°. One sample t-test indicated that the orientation of the fibroblast-derived matrix was statistically different than the micropattern (p<0.0001), however the deviation was less than 10°, which is commonly used as a threshold for alignment [31-34]. The consistent orientation of the ECM fibrils was indicated by the small standard errors of major axis orientation seen in the patterned regions (vertical = 0.68° and horizontal= 1.3°) as compared with the non-patterned region (13°). The relatively low standard deviation in preferred orientation is highlighted in the box and whiskers graph shown in Figure 3 i.

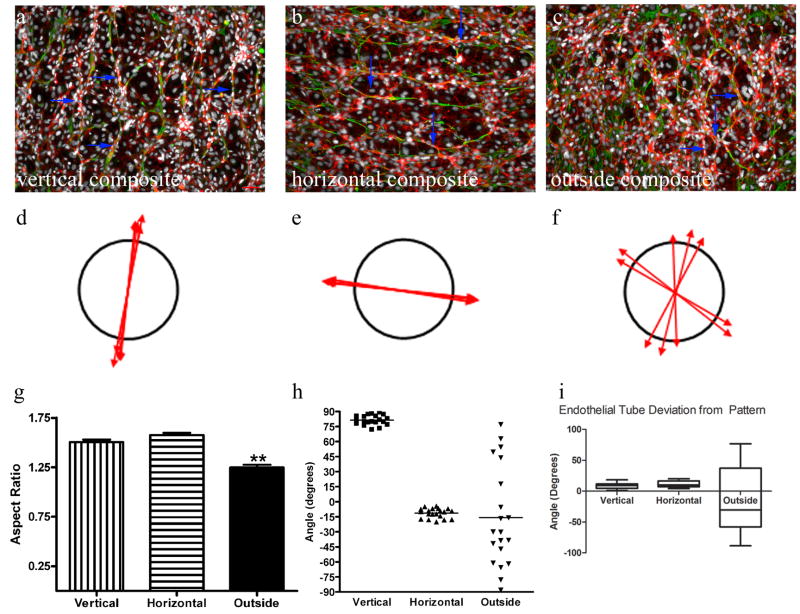

3.3 Endothelial Tube Alignment

To test the hypothesis that the patterned alignment conferred specific functional properties to the matrix, the formation of endothelial tubes was examined on the matrix produced from populations of aligned fibroblasts that were adhered to patterned substrates and on the matrix assembled by randomly adhered fibroblasts (on non-patterned substrates). As previous described, after 24 hours HUVEC remodeled the fibroblast-derived matrix and formed chords of matrix which some of the cells wrapped around to form endothelial tubes [12]. To visualize the endothelial tubes and the extracellular matrix, the samples were labeled for F-actin, nuclei, and fibronectin (Figure 4 a, b, c and Supplemental Figure 3 (individual channels)). Similar to the trend noted with the fibroblast-derived matrix, the anisotropies measured in the F-actin images from patterned regions were greater than they were in the non-patterned regions (Figure 4 j) (p<0.001). The average anisotropies in vertically and horizontally patterned areas were 1.5 ± 0.02 and 1.6 ± 0.02, respectively, while the average anisotropy in the region outside the pattern was 1.3 ± 0.03. In addition, the preferred orientation of endothelial tubes in the micropatterned regions was close to that of the original pattern alignment (Figure 4 k). The average vertical region angle was 81 ± 1.1° and the horizontal region was -11 ± 1.1°. The outside region had an average angle of -16 ± 11°. The average deviations of the endothelial tube orientations from the original micropattern was 10±0.8° (Figure 4 i). One sample t-test indicated that the orientation of the endothelial tubes was statistically different than the micropattern (p<0.0001); however, the deviation is at the threshold of 10° and is still considered aligned with the micropattern. Again, a small standard error of the mean was noted in the patterned regions (vertical=1.1°, horizontal= 1.1°, and outside = 11°) and the standard deviation is illustrated in the box and whiskers graph, Figure 4 i. The difference in average tube alignments from fibroblast-derived matrix orientation were less than 1° and 4° in the vertical and horizontal regions, respectively. Both the horizontal (p=0.05) and vertical (p<0.7) regions, showed no significant difference in orientation between the aligned ECM and the endothelial tubes that formed in their respective micropatterned region. Taken together with the larger anisotropies and tightly clustered angles of tube alignment noted in pattern areas, these data demonstrate that the orientation of the fibroblast-derived matrix directed the alignment of the endothelial tubes.

Figure 4. Endothelial Tube Formation in Regions of Linear Patterned Matrix.

HUVEC formed tubes (indicated by blue arrows) when seeded on the fibroblast-derived matrix. Samples were labeled for F-actin (red), fibronectin (green), and nuclei (grey) (a merge of all three is shown in panels a-c). Representative data from vertical (a), horizontal (b), and non-patterned (c) regions are shown. Scale = 65 μm (located in a). Representative vector plots of the anisotropy and orientation of the HUVEC actin in the different regions are shown in d-f. The average aspect ratios of tubes from the three regions (vertical, horizontal and outside) are shown in g. Both the vertical and horizontal pattern regions had significantly larger anisotropies than the outside region. ** indicates p<0.001. The angles of the preferred tube orientations are shown in h. Each dot represents a data point and the lines represent the mean angle for each region. The box and whiskers graph in i represents the angle of deviation in preferred orientation of the endothelial cells from the original micropattern.

To further support the conclusion that the fibroblast-derived matrix directed the endothelial cell tubes, the original patterned fibronectin substrate was no longer detected by immunofluorescence on the coverslip at the time that the tube formation assay was done. The immunofluorescence staining of fibronectin has a fibrillar morphology in fibroblast-derived matrix that is not seen in the absorbed fibronectin for the micropattern (shown in Figure 1). Images of the amine-labeled fibroblast-derived matrix showed no signs of micropatterned fibronectin remaining after the fibroblasts were cultured for 7 days. Since the micropattern was no longer present at the time of HUVEC seeding on the fibroblast-derived matrix, the original micropattern could not be directing the of the endothelial cell tubes alignment. In addition, the endothelial tubes formed were three dimensional and were located on top of a monolayer of endothelial cells (Supplemental Figure 5 a and b). This monolayer prevented the HUVEC forming the tubes from interacting with the coverslip where the micropattern was originally.

To further test whether tube formation and alignment was due to the micropattern, HUVEC were seeded directly onto a micropatterned coverslip in the same conditions as the seeding on the fibroblast-derived matrix for tube formation. In this condition, no HUVEC tubes formed and a monolayer of cells was observed (Supplemental Figure 5 c). The F-actin of the endothelial cells in regions with micropatterned lines resembled the F-actin of cells in the non-patterned regions, and did not follow the pattern despite the persistent presence of the micropatterned fibronectin at 24 hours - the latest time point at which the original micropattern was observed following cell seeding with either HUVEC or WI38.

3.4 Controlling Endothelial Tube Branching

Branching of endothelial tubes is necessary to build complex microvascular networks. We examined whether endothelial tubes could be directed to form branches at 90° and 40°. Fibroblast-derived matrix produced on micropatterned coverslips with “L” and “Y” shapes (Supplemental Figure 4 a and b) were created to ultimately direct the shape of the endothelial tubes. WI38 adhered and produced extracellular matrix after 7 days in culture in accordance with the “Y” pattern (Figure 5 a). Endothelial cells seeded on the shaped matrix and formed a “V”-shaped tube at the branching point of the “Y” micropattern (merged image in Figure 5 b and individual images in Supplemental Figure 4 c). Angle measurements of fibroblasts 2.5 hours after seeding were within 5° of the original “Y” pattern (Supplemental Figure 4 d). The average angle of the resulting fibroblast-derived matrix was also 5° of the original pattern (35± 1.7°), but over the 7 days of culture the alignment had changed 10° from the initial seeding measurements (Supplemental Figure 4 d). However, a deviation of 10° is consistent with the deviation in fibroblast-derived matrix orientation noted in the horizontal and vertical pattern regions. The endothelial tubes formed a branch with an angle of 49± 1.0° in the region originally containing a “Y” micropattern. The branch was also within the 10° of the original pattern (Supplemental Figure 4 d). Similarly, the fibroblast-derived matrix produced on a “L” pattern directed the endothelial tubes to turn similar to the pattern (merged image in Figure 5 c and individual channels in Supplemental Figure 4 c). Angle measurements showed good alignment of WI38 at 2.5 hours to the “L” shaped micropattern (93±2.7°), but the angle of the endothelial tubes formed in this region was 31° larger than the original pattern (Supplemental Figure 4 d). The fibroblast-derived matrix formed on a “L” micropattern did not induce a single 90° turn in the endothelial tubes. Instead, the endothelial tubes formed contain a series of turns that lead to a shape resembling an “L” with an angle of 107±1 .9°. These data indicated that this approach may be useful in finely tuning engineered endothelial tubes to supply regional needs based upon microtopography and metabolic demands in engineered tissues.

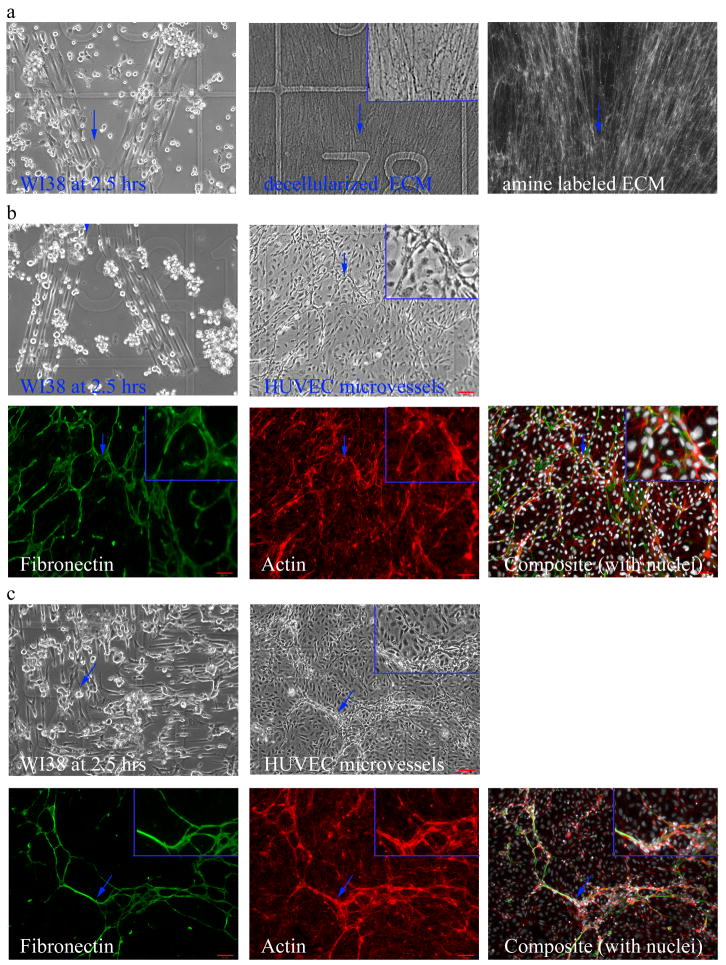

Figure 5. Variations in Micropattern Geometry.

Coverslips containing micropatterns of “Y” shapes were studied (a and b). WI38 cells adhered to the pattern in serum free conditions at 2.5 hours and after 7 days produced matrix in accordance with the pattern (a, left image and b top left image) The WI38 adhesion and matrix production on a “Y” micropattern can be seen right above the number 78 (denoted with a blue arrow in each image). The corresponding amine labeled fibroblast-derived matrix image for that region is shown on the right. The insert in a is a 1.5x magnification of the region highlighted with the arrow. When HUVEC were seeded on matrices produced on these micropatterns, they formed tubes with a similar shape (b). The “Y” shape was documented at 2.5 hours at location 132 (denoted with a blue arrow). A branching tube was observed with phase at the same location above the 3 in grid 132 (blue arrow pointing at vessel). The corresponding epifluorescence images of fibronectin, actin, and an overlay with nuclei for this location are shown (blue arrows are a reference that marks the same location in all images in b). The inserts in b are a 2x magnification of the region highlighted with the arrow. Similar control of tube geometry was noted with fibroblast-derived matrix produced on micropatterns of fibronectin in the shape of “L” (c). The turn in the “L” micropattern was observed in grid 178 at 2.5 hrs. Endothelial tubes formed in a similar shape as at the same location (178). The corresponding epiflourescence images of fibronectin, f-actin, and composite with nuclei for this region are shown in. The blue arrows are a reference that marks the same location in all images in c. The inserts in c are a 1.5x magnification. The scale bars are 65 μm and the grid line width is 20 μm.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1 Spatial control of fibroblast growth patterns matrix orientation and functionality

In the present work, micropatterned substrates were used to guide lung fibroblast growth, the subsequent deposition of fibroblast-derived matrix, and the formation of endothelial tubes on these aligned fibroblast-derived matrices. Control of matrix orientation and structure is a desirable feature for tissue engineering scaffolds. Fibroblast-derived matrices provide unique multi-component three-dimensional scaffolds and are capable of promoting endothelial tubulogenesis [12, 27]. Here, micropatterning was used to manipulate the fibroblast-derived matrix anisotropy and shape, which makes these matrices advantageous compared to single component isotropic scaffold materials whose structure cannot be controlled. The impact of the aligned three-dimensional extracellular matrix on endothelial morphogenesis was examined. The orientation of tubes formed on the fibroblast-derived matrix correlated with the direction of the engineered fibroblast-derived matrix. In addition, fibroblast-derived matrix in “L” or “Y” shapes directed endothelial cells to form tubes that mimicked these shapes. These data demonstrate the utility of natural, cell-derived extracellular matrix organization for instructing the alignment and shape of endothelial tubes.

Micropatterns of proteins, such as fibronectin, or peptide sequences have previously been implemented on various substrates to align endothelial cells, direct their migration, and direct their tube formation [35, 36]. In these studies, the micropatterned protein or peptide was responsible for directing the endothelial cells, as the cells were directly seeded onto the micropatterned substrate. In contrast, in the work presented here the endothelial cells did not interact with the original micropattern, but with the aligned 3D fibroblast-derived matrix. The fibronectin from the micropattern was most likely enzymatically removed by fibroblasts over the 7 day culture period, as it was not observed by immunofluorescence. As a control, HUVEC were directly onto a micropatterned substrate, but they did not align with it as others have previously reported. This is likely due to the HUVEC seeding conditions with serum containing medium, which was selected to mimic the seeding conditions on the fibroblast-derived matrix. In addition, parameters such as optimal line width and pitch would need to be explored for HUVEC to encourage a response to the micropattern. In addition to microcontact printing techniques, nanofibrous scaffolds have been aligned by electrospinning, phase separation, and other techniques to direct endothelial cells and endothelial tubes [37-40]. The work presented here is unique in using micropatterns to align the three dimensional scaffold, fibroblast-derived matrix, which has instructive properties to encourage endothelial tube formation[12]. By demonstrating control of fibroblast-derived matrix anisotropy, the versatility of this scaffold has been expanded. Future investigations of the relationship between cell functions other than alignment of endothelial tubes with the structural properties of the matrix can be explored with this approach.

4.2 Challenges to engineering anisotropy

The metric for anisotropy used here is a vector with a magnitude that indicates the magnitude of asymmetric features in an image and an angle along which that asymmetry lies. As mentioned earlier, the original patterned fibronectin was not visualized by immunofluorescence after 7 days of fibroblast culture and therefore did not influence the anisotropy measurements. The measurements for fibroblast-derived matrix and endothelial tubes in patterned regions both had anisotropies greater than 1; however the non-patterned areas also had anisotropies greater than 1. These data imply that there was some persistence in the matrix organization within the non-patterned regions. Two considerations must be kept in mind when interpreting these data. First, the degrees of anisotropy in the patterned regions for both the fibroblast-derived matrix and endothelial tubes were significantly larger than those observed in the non-patterned region. Second, differences in the variability of the orientation angle for each of the different regions were noted. For example, the small standard error of the mean for the matrix angles in patterned regions indicated that the matrix in these pattern regions was aligned in a highly reproducible fashion. However, matrix orientation in the nonpatterned region had a much larger standard error of the mean. Taken together with the relatively lower anisotropy in the non-patterned region, these data apparently describe small degrees of anisotropy in many different directions. This description of the fibroblast-derived matrix that was formed in the nonpatterned regions closely correlates with the morphology of confluent WI38 in nonpatterned tissue culture dishes, which naturally form aligned sheets of cells (as in Figure 2e), but do not have uniform orientation when the cells are plated on non-patterned surfaces.

Engineering a three-dimensional scaffold that mimics the instructive nature of native extracellular matrix structure and architecture in vitro is a nontrivial task. The current study was prompted by the fact that single-component polymer scaffolds lack the instructive attribute that we have described in fibroblast-derived matrices [12]. Our work builds on previous data in order to directly study the functional impact of matrix organization on tissue morphogenesis. Manwaring et al demonstrated that substrate topography directed meningeal cell alignment and one-dimensional arrays of extracellular matrix [5]. Such studies indicated that it might be feasible to direct the dense three-dimensional matrix produced by lung fibroblasts using micropatterned substrates. An alternative approach for the execution of anisotropic scaffolds is electrospinning to align natural and synthetic polymer nanofibers [41, 42]. Anisotropic scaffolds have shown promising results in engineering musculoskeletal tissue, meniscus tissue, and progenitor and stem cell growth and differentiation [4, 42-44]. In other work, Raghavan et al used three-dimensional micropatterned collagen gels to control the geometry of vasculature networks [45]. In contrast to these previous efforts, our work with natural cell-derived scaffolds opens the possibility that an autologous cell-based strategy could be harnessed to stimulate organ-specific tissue morphogenesis in a manner that exploits the precise spatially directive features of our technique. Anisotropic directional guidance of microvascular development is a long term goal with broad applicability in tissue engineering including facilitation of wound healing and enhancement of regenerative strategies for the heart and the kidney[46-48]. The approach described in the current study offers potential for this application.

4.3 Conclusions and near term goals in tissue engineering microvascular networks

By controlling the direction of endothelial tubes, blood supply may ultimately be provided to precisely targeted regions of metabolic vulnerability. In this work, an approach to control fibroblast-derived matrix anisotropy was developed. The aligned regions of matrix were able to direct endothelial tube orientation. In addition, this approach can be applied to create fibroblast-derived matrix and endothelial tubes with more complex geometries with branches and turns. These findings clearly demonstrate the importance of extracellular matrix organization in cell morphogenesis. Engineering the structural organization of a scaffold is important to mimic the in vivo tissue architecture and to ultimately create functional tissues. This work describes an approach to control the geometry of vascular networks and to further study the formation of endothelial tubes.

Supplementary Material

Phase images of WI38 cells seeded on a horizontal patterned region tracked over 7 days. The number 105 can be seen in all images at different time points. The fibroblasts adhered to the micropatterned lines in 2.5 hours in serum free conditions. After the media was changed, the fibroblasts maintained their alignment with the pattern at 5 hrs and proliferated at the 1 day time point. The cells maintained this alignment over 7 days of culture.

A pre-analysis image of amine-labeled fibroblast-derived matrix is shown in a. Scale bar = 65 μm. The first step of the anisotropy analysis was to convert the image to an 8 bit image and crop it to 1024 × 1024 pixels (b). Using ImageJ Fast Fourier Transform, the image was correlated with itself (c). A threshold between 0 and 127 was then applied to the autocorrelation result image (d). Finally, the long and short axis and long axis angle of the thresholded image were measured (insert of d). These data were used to calculate the image anisotropy and the major axis orientation.

The corresponding monochromatic images of the merged endothelial tubes shown in Figure 4 are displayed. The first row corresponds to Figure 4a (endothelial tubes formed in vertical pattern). The second row contains the corresponding images found in a region with the horizontal pattern (Figure 4b). The third row contains images from the outside region with no pattern (Figure 4c). The nuclei are displayed in grey, fibronectin in green, and actin in red to correspond the merged images in Figure 4.

Fibronectin staining of the micropatterned coverslips show the “Y” shape (a) and the “L” shape (b) that was used to direct fibroblast-derived matrix and subsequent endothelial tube formation on the matrix. These are prototype images of the micropattern and the number of fibronectin lines in the “L” pattern (b) is different from the number used in pattern examined in Figure 5c. c) The corresponding monochromatic images of the merged endothelial tubes shown in Figure 5 are displayed. The first row corresponds to Figure 5 b (tubes formed in “Y” pattern). The second row contains the corresponding images found in a region with the “L” pattern (Figure 5 c). The nuclei are displayed in grey, fibronectin in green, and actin in red to correspond the merged images in Figure 5. d) The table summarizes the average angles (± SEM) of WI38 cells at 2.5 hours, fibroblast-derived matrix, and endothelial cell remodeled fibronectin in regions with a “Y” or “L” shaped micropatterns.

Z-stack of image of tubes formed in a horizontally aligned cell-derived matrix region was collected (a). The image of HUVEC F-actin at the bottom of the z-stack (cells touching the coverslip) is on the left. This image indicates that the cells were not aligned to any pattern, since the F-actin filaments are in all directions. The image at the top of the z-stack (image on the right) appeared to have anisotropic actin filaments (highlighted with blue arrows). Scale bar =16 μm (bottom slice image). The difference in actin through the z stack implies that there is depth to the endothelial tubes formed on the fibroblast-derived matrix. A three-dimensional reconstruction from a z-stack of HUVEC tube images supports the depth of the tubes and is shown in b. HUVEC F-actin is shown in green, fibronectin in red, and nuclei in grey. This image shows a tube sitting on top of a monolayer of HUVEC that are interacting with the coverslip. Scale bar = 13 μm. In a separate study to test the role of the original micropatterned substrate in directing the tube alignment, HUVEC were seeded directly onto coverslips patterned with lines of fibronectin in the same conditions as seeding for tube formation (c). After 24 hours, the endothelial cell actin (green) in the non-patterned region (left) and patterned region (middle) had similar configurations, even though the micropatterned fibronectin (red) was still present (right image; blue arrows mark residual fibronectin pattern). This suggests that HUVEC were not aligned to the micropattern under these conditions. Scale bar is 15 μm.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Shawna Lewis for her support with data organization. This work was supported by NRSA DE016544 (PAS); and MCB-0923661 from the NSF, GRNT7690056 from the AHA, and NIH HL088203 (to LHR).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The products and services described in this article are being developed by Intelligent Substrates. Dr. Hoh and Dr. Heinz are entitled to a share of equity as founders of Intelligent Substrates. Dr. Hoh also served as an advisor to the company, and Dr. Heinz served as the President of the company. Dr. Hoh and Dr. Heinz are also entitled to a share of royalty received by the university on sales of products related to this article. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fung Y-C. Biomechanics: mechanical properties of living tissues. New York: Spinger-Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isenberg BC, Tsuda Y, Williams C, Shimizu T, Yamato M, Okano T, et al. A thermoresponsive, microtextured substrate for cell sheet engineering with defined structural organization. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2565–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmedlen RH, Elbjeirami WM, Gobin AS, West JL. Tissue engineered small-diameter vascular grafts. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30:507–17. doi: 10.1016/s0094-1298(03)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li WJ, Mauck RL, Cooper JA, Yuan X, Tuan RS. Engineering controllable anisotropy in electrospun biodegradable nanofibrous scaffolds for musculoskeletal tissue engineering. J Biomech. 2007;40:1686–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manwaring ME, Walsh JF, Tresco PA. Contact guidance induced organization of extracellular matrix. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3631–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivron NC, Liu JJ, Rouwkema J, de Boer J, van Blitterswijk CA. Engineering vascularised tissues in vitro. Eur Cell Mater. 2008;15:27–40. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v015a03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005;310:1139–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engler A, Bacakova L, Newman C, Hategan A, Griffin M, Discher D. Substrate compliance versus ligand density in cell on gel responses. Biophys J. 2004;86:617–28. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georges PC, Janmey PA. Cell type-specific response to growth on soft materials. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1547–53. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01121.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelham RJ, Jr, Wang YL. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by the mechanical properties of the substrate. Biol Bull. 1998;194:348–9. doi: 10.2307/1543109. discussion 9-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soucy PA, Romer LH. Endothelial cell adhesion, signaling, and morphogenesis in fibroblast-derived matrix. Matrix Biol. 2009;28:273–83. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kutys ML, Doyle AD, Yamada KM. Regulation of cell adhesion and migration by cell-derived matrices. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:2434–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294:1708–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mao Y, Schwarzbauer JE. Stimulatory effects of a three-dimensional microenvironment on cell-mediated fibronectin fibrillogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4427–36. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Micropatterned surfaces for control of cell shape, position, and function. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14:356–63. doi: 10.1021/bp980031m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thery M, Pepin A, Dressaire E, Chen Y, Bornens M. Cell distribution of stress fibres in response to the geometry of the adhesive environment. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2006;63:341–55. doi: 10.1002/cm.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thery M, Racine V, Pepin A, Piel M, Chen Y, Sibarita JB, et al. The extracellular matrix guides the orientation of the cell division axis. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:947–53. doi: 10.1038/ncb1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng J, Chan-Park MB, Shen J, Chan V. Quick layer-by-layer assembly of aligned multilayers of vascular smooth muscle cells in deep microchannels. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1003–12. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarkar S, Dadhania M, Rourke P, Desai TA, Wong JY. Vascular tissue engineering: microtextured scaffold templates to control organization of vascular smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doyle AD, Wang FW, Matsumoto K, Yamada KM. One-dimensional topography underlies three-dimensional fibrillar cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:481–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200810041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingber DE, Folkman J. Mechanochemical switching between growth and differentiation during fibroblast growth factor-stimulated angiogenesis in vitro: role of extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:317–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolodziej CM, Kim SH, Broyer RM, Saxer SS, Decker CG, Maynard HD. Combination of integrin-binding peptide and growth factor promotes cell adhesion on electron-beam-fabricated patterns. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012;134:247–55. doi: 10.1021/ja205524x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyoshi H, Ju J, Lee SM, Cho DJ, Ko JS, Yamagata Y, et al. Control of highly migratory cells by microstructured surface based on transient change in cell behavior. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8539–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thery M, Racine V, Piel M, Pepin A, Dimitrov A, Chen Y, et al. Anisotropy of cell adhesive microenvironment governs cell internal organization and orientation of polarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19771–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609267103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiery JP. Cell adhesion in development: a complex signaling network. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:365–71. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soucy PA, Werbin J, Heinz W, Hoh JH, Romer LH. Microelastic properties of lung cell-derived extracellular matrix. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011;7:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babensee JE. Interaction of dendritic cells with biomaterials. Seminars in immunology. 2008;20:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Press WH, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP. Numerical Recipes in C: The Art of Scientific Computing Second Edition. 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Z, Penczek PA. Cryo-EM image alignment based on nonuniform fast Fourier transform. Ultramicroscopy. 2008;108:959–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aubin H, Nichol JW, Hutson CB, Bae H, Sieminski AL, Cropek DM, et al. Directed 3D cell alignment and elongation in microengineered hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6941–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charest JL, Eliason MT, Garcia AJ, King WP. Combined microscale mechanical topography and chemical patterns on polymer cell culture substrates. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2487–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hassanzadeh P, Kharaziha M, Nikkhah M, Shin SR, Jin J, He S, et al. Chitin Nanofiber Micropatterned Flexible Substrates for Tissue Engineering. Journal of materials chemistry B, Materials for biology and medicine. 2013;1 doi: 10.1039/C3TB20782J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosseini V, Ahadian S, Ostrovidov S, Camci-Unal G, Chen S, Kaji H, et al. Engineered contractile skeletal muscle tissue on a microgrooved methacrylated gelatin substrate. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:2453–65. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dike LE, Chen CS, Mrksich M, Tien J, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Geometric control of switching between growth, apoptosis, and differentiation during angiogenesis using micropatterned substrates. In vitro cellular & developmental biology Animal. 1999;35:441–8. doi: 10.1007/s11626-999-0050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lei Y, Zouani OF, Remy M, Ayela C, Durrieu MC. Geometrical microfeature cues for directing tubulogenesis of endothelial cells. PloS one. 2012;7:e41163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armentano I, Dottori M, Fortunati E, Mattioli S, Kenny JM. Biodegradable polymer matrix nanocomposites for tissue engineering: A review. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 2010;95:2126–46. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beachley V, Wen X. Polymer nanofibrous structures: Fabrication, biofunctionalization, and cell interactions. Progress in polymer science. 2010;35:868–92. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunne LW, Iyyanki T, Hubenak J, Mathur AB. Characterization of dielectrophoresis-aligned nanofibrous silk fibroin-chitosan scaffold and its interactions with endothelial cells for tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomater. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nogueira GM, Swiston AJ, Beppu MM, Rubner MF. Layer-by-layer deposited chitosan/silk fibroin thin films with anisotropic nanofiber alignment. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2010;26:8953–8. doi: 10.1021/la904741h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ayres C, Bowlin GL, Henderson SC, Taylor L, Shultz J, Alexander J, et al. Modulation of anisotropy in electrospun tissue-engineering scaffolds: Analysis of fiber alignment by the fast Fourier transform. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5524–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang F, Murugan R, Wang S, Ramakrishna S. Electrospinning of nano/micro scale poly(L-lactic acid) aligned fibers and their potential in neural tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2603–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker BM, Mauck RL. The effect of nanofiber alignment on the maturation of engineered meniscus constructs. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1967–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lanfer B, Seib FP, Freudenberg U, Stamov D, Bley T, Bornhauser M, et al. The growth and differentiation of mesenchymal stem and progenitor cells cultured on aligned collagen matrices. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5950–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raghavan S, Nelson CM, Baranski JD, Lim E, Chen CS. Geometrically controlled endothelial tubulogenesis in micropatterned gels. Tissue Eng Part A. 16:2255–63. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Z, Vong QP, Liu C, Zheng Y. Borg5 is required for angiogenesis by regulating persistent directional migration of the cardiac microvascular endothelial cells. Molecular biology of the cell. 2014;25:841–51. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-09-0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Outeda P, Huso DL, Fisher SA, Halushka MK, Kim H, Qian F, et al. Polycystin signaling is required for directed endothelial cell migration and lymphatic development. Cell reports. 2014;7:634–44. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paradise RK, Whitfield MJ, Lauffenburger DA, Van Vliet KJ. Directional cell migration in an extracellular pH gradient: a model study with an engineered cell line and primary microvascular endothelial cells. Experimental cell research. 2013;319:487–97. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phase images of WI38 cells seeded on a horizontal patterned region tracked over 7 days. The number 105 can be seen in all images at different time points. The fibroblasts adhered to the micropatterned lines in 2.5 hours in serum free conditions. After the media was changed, the fibroblasts maintained their alignment with the pattern at 5 hrs and proliferated at the 1 day time point. The cells maintained this alignment over 7 days of culture.

A pre-analysis image of amine-labeled fibroblast-derived matrix is shown in a. Scale bar = 65 μm. The first step of the anisotropy analysis was to convert the image to an 8 bit image and crop it to 1024 × 1024 pixels (b). Using ImageJ Fast Fourier Transform, the image was correlated with itself (c). A threshold between 0 and 127 was then applied to the autocorrelation result image (d). Finally, the long and short axis and long axis angle of the thresholded image were measured (insert of d). These data were used to calculate the image anisotropy and the major axis orientation.

The corresponding monochromatic images of the merged endothelial tubes shown in Figure 4 are displayed. The first row corresponds to Figure 4a (endothelial tubes formed in vertical pattern). The second row contains the corresponding images found in a region with the horizontal pattern (Figure 4b). The third row contains images from the outside region with no pattern (Figure 4c). The nuclei are displayed in grey, fibronectin in green, and actin in red to correspond the merged images in Figure 4.

Fibronectin staining of the micropatterned coverslips show the “Y” shape (a) and the “L” shape (b) that was used to direct fibroblast-derived matrix and subsequent endothelial tube formation on the matrix. These are prototype images of the micropattern and the number of fibronectin lines in the “L” pattern (b) is different from the number used in pattern examined in Figure 5c. c) The corresponding monochromatic images of the merged endothelial tubes shown in Figure 5 are displayed. The first row corresponds to Figure 5 b (tubes formed in “Y” pattern). The second row contains the corresponding images found in a region with the “L” pattern (Figure 5 c). The nuclei are displayed in grey, fibronectin in green, and actin in red to correspond the merged images in Figure 5. d) The table summarizes the average angles (± SEM) of WI38 cells at 2.5 hours, fibroblast-derived matrix, and endothelial cell remodeled fibronectin in regions with a “Y” or “L” shaped micropatterns.

Z-stack of image of tubes formed in a horizontally aligned cell-derived matrix region was collected (a). The image of HUVEC F-actin at the bottom of the z-stack (cells touching the coverslip) is on the left. This image indicates that the cells were not aligned to any pattern, since the F-actin filaments are in all directions. The image at the top of the z-stack (image on the right) appeared to have anisotropic actin filaments (highlighted with blue arrows). Scale bar =16 μm (bottom slice image). The difference in actin through the z stack implies that there is depth to the endothelial tubes formed on the fibroblast-derived matrix. A three-dimensional reconstruction from a z-stack of HUVEC tube images supports the depth of the tubes and is shown in b. HUVEC F-actin is shown in green, fibronectin in red, and nuclei in grey. This image shows a tube sitting on top of a monolayer of HUVEC that are interacting with the coverslip. Scale bar = 13 μm. In a separate study to test the role of the original micropatterned substrate in directing the tube alignment, HUVEC were seeded directly onto coverslips patterned with lines of fibronectin in the same conditions as seeding for tube formation (c). After 24 hours, the endothelial cell actin (green) in the non-patterned region (left) and patterned region (middle) had similar configurations, even though the micropatterned fibronectin (red) was still present (right image; blue arrows mark residual fibronectin pattern). This suggests that HUVEC were not aligned to the micropattern under these conditions. Scale bar is 15 μm.