Abstract

Aim

The aim of this systematic literature review is to investigate which types of patient participation in medication reviews have been practiced and what is known about the effects of patient participation within the medication review process.

Methods

A systematic literature review was performed in multiple databases using an extensive selection and quality assessment procedure.

Results

In total, 37 articles were included and most were assessed with a weak or moderate quality. In all studies patient participation in medication reviews was limited to the level of information giving by the patient to the professional, mainly on actual drug use. Nine studies showed limited results of effects of patient participation on the identification of drug related problems.

Conclusions

The effects of patient participation are not frequently studied and poorly described in current literature. Nevertheless, involving patients can improve patients' knowledge, satisfaction and the identification of drug related problems. Patient involvement is now limited to information sharing. The profit of higher levels of patient communication and shared decision making is until now, not supported by evidence of its effectiveness.

Keywords: drug related problems, medication reviews, patient participation, systematic literature review

Introduction

Patient participation is seen as the key to modern health care and has been widely implemented in medical decision making and the management of chronic diseases 1. The World Health Organization (WHO) programme Patients for Patient Safety also emphasizes the central role patients should play in efforts to improve the quality and safety of health care 2. Positive effects of a structured two way communication between patients and health care professionals can be increased patient knowledge, adherence, and satisfaction 3. With respect to pharmaceutical care, patient participation is thought to improve concordance between the patient and the health care provider on the pharmacotherapy 3. It is also suggested that involvement of patients in pharmaceutical interventions, such as medication reviews, is important for motivation to change and long term effectiveness of pharmacotherapy 4.

The UK National Prescribing Centre defines a medication review as ‘a structured, critical examination of a patient's medicines with the objective of reaching an agreement with the patient about treatment, optimizing the impact of medicines, and minimizing the number of drug related problems’ 5. Drug related problems (DRPs) frequently occur in the elderly and can be drug interactions, inefficacy of treatment, adverse drug reactions, prescription errors but also non-compliance with treatment and user problems. The medication review definition includes patient participation in the medication review process and agreement between patient, physician and about the treatment.

The definition of patient participation is not self-evident. Patient participation, patient collaboration, patient involvement, partnership, patient empowerment or patient-centred care, are used interchangeably 1. Street & Millay defined patient participation in medical consultations as ‘the extent to which patients influence the content and the structure of the interaction as well as the health care provider's beliefs and behaviour by, for example, asking questions, descriptions of health experiences, expressing concerns, giving opinions, making suggestions and stating preferences’ 6.

Thompson defined levels of patient involvement from the patient perspective 7. Parallel to a literature-based ranking of professional-determined levels of involvement, Thompson, on the basis of comprehensive qualitative data, defined several levels of patient-desired involvement (Table 1). This follows the three decision making models, paternalistic, informed and professional-as-agent of Charles et al. 8 Participation is seen as being co-determined by patients and professionals and occurring only through the reciprocal relationships of dialogue and shared decision making. In a dialogue the patient gives information and there is consultation by the professional, in shared decision making the professional acts as agent. The model and definition of Thompson is used in this research 7.

Table 1.

Levels of patient involvement in health care consultations

| Patient desired level | Patient determined | Co-determined (participation) | Professional determined |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Autonomous decision-making | Informed decision making | |

| 3 | Shared decision making | Professional-as-agent | |

| 2 | Information giving | Dialogue | Consultation |

| 1 | Information seeking/receptive | Information giving | |

| 0 | Non-involved | Exclusion |

Adapted from 7. Reprinted from Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 64, AGH Thompson, ‘The meaning of patient involvement and participation in health care consultations: A taxonomy’, Pages 1297–1310, Copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier.

Furthermore, giving information during a dialogue between patient and caregiver has a different purpose than shared or informed decision making. In the context of medication reviews, patient input is needed as preparation for the medication review, to incorporate the patient's perspective. The purpose of information giving by the caregiver is mainly educational. On the other hand there is the decision making process, where the purpose is to make a joint decision.

Active patient participation in medication reviews is increasingly recognized as a prerequisite for a successful medication review and consequently in optimal pharmacotherapy and acknowledged in international and recent Dutch guidelines 5,9–11.

In the field of treatment counselling, especially for oncology, there is indeed evidence that the involvement of patients and shared-decision making led to more satisfied patients, better adherence to therapy and better health outcomes 12–14. However, little is known about the effects of patient participation in medication reviews on patient outcomes. Before studying possible effects of patient participation, the different types of patient participation researched must be identified.

The aim of this systematic literature review is to investigate which types of patient participation in medication reviews have been practiced and what is known about the effects of patient participation within the medication review process. The following research questions were formulated:

Which types of patient participation in medication reviews have been researched?

What are the effects of patient participation in medication reviews on drug related problems (DRPs) and other patient outcomes?

Methods

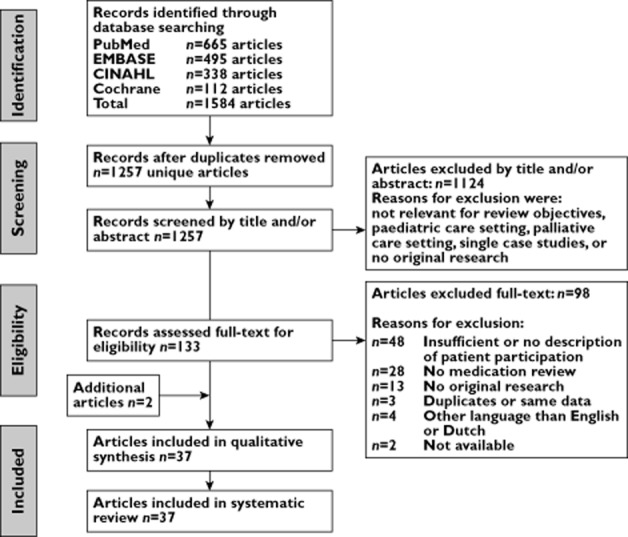

A systematic literature review was conducted following the PRISMA statement 15. A literature search was performed in the databases PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL and Cochrane Library in July 2013. A search strategy was developed by the first author (FW) and an experienced information specialist (Appendix S1). The search strategy combined different synonyms and related terms of patient participation with synonyms of medication reviews. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for articles are displayed in Box 1. In addition, the references from all included articles were also examined for relevant articles.

Box 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Original research AND;

Medication review with any type of patient participation AND;

Adult or elderly population.

Exclusion criteria

No original research, editorials, letter to the editors, comments, conference abstracts;

Single case studies;

Study design articles, without any results;

Medication review without any type of patient participation, care in which the patient does not give any information and is not involved at all;

Insufficient description of the patient participation, unable to define the level by Thompson 7

Child or adolescent population;

Studies in the palliative care setting.

Articles in other languages than English or Dutch

Three types of medication reviews can be distinguished based on the data used: (1) clinical medication reviews are based on medication records, medical records and patient data, (2) concordance and compliance medication reviews are based on medication records and patient data, and (3) prescription reviews are based on medication records only, so without patient data 16. In the present literature review only clinical medication reviews or concordance and compliance reviews 6 have been included. According to Thompson's model of patient participation (Table 1), patient participation starts at the level of information giving to the health care professional by the patient or his carer 7.

Selection procedure

The selection procedure of relevant articles included three steps: (1) screening of title and abstract, (2) full text based selection and (3) quality assessment (Figure 1). References of selected articles were also screened for relevant articles and extra articles could be added on the basis of expert opinion. Two authors (FW, PJME) screened all 1257 titles and abstracts independently. In case of doubt, an article was included for full text review. The first 50 titles and abstracts were screened and discussed to reach agreement on interpretations, definitions and inclusion and exclusion criteria. After screening all titles and abstracts, consensus was reached in a consensus meeting for all disagreements. In total, 133 articles were selected for full text review. The measure of agreement between the reviewers, Cohen's kappa (κ) was calculated.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selection process

The first author screened all 133 full text articles on inclusion and exclusion criteria according to Box 1. In case of any doubt, the full text article was discussed with at least one other author. In total, 37 articles were selected for quality assessment and included in this literature review, of which one was obtained from the references of the selected articles, and one article was added on the basis of expert opinion.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was carried out independently by three authors (FW, PJME, JGH) for all 37 articles. One reviewer (FW) assessed all relevant full text articles and two other reviewers (PJME, JGH) both assessed half of the articles, independently of each other.

The complexity and heterogeneity of the articles for the first research question required a specific qualitative assessment based on the description of information about patient participation and whether an evaluation was carried out. Mainly, the completeness of reporting was assessed, assuming a correlation with the quality of reporting and the quality of the study. For the second research question, again articles were very heterogenic and studies were mainly of an observational or qualitative nature. Existing tools were used, with minimal adaptions, to assess the quality of the article. Three checklists were used, dependent on the literature review objective and whether the results were quantitative or qualitative (Box 2).

Box 2 Checklists for quality assessment.

- Checklist for description and evaluation of patient participation: Qualitative assessment on adequacy of the description of patient participation and evaluation of patient participation. The following questions were included in the checklist, which consisted of two sub ratings; description and evaluation of patient participation.

- Description of patient participation

- Is there sufficient information to derive a level of participation?

- Is there information on type of communication?

- Is there information on which health care professional is involved?

- Evaluation of patient participation

- The study describes how often patient participation is carried out according to protocol

- The study evaluated the health care professional-patient communication

- The study evaluated the patient input in the medication review

- Information on time consumption of the patient participation

- Information on the costs of patient participation

- Information on other evaluation topics of patient participation Explanation and exact interpretation of all questions were discussed among the reviewers. Weak, moderate and strong ratings were assigned to the articles based on the sub ratings. In total, all 30 quantitative articles were assessed with this checklist.

- Checklist for quantitative studies: Methodological quality of studies on the effects of patient participation. This checklist is based on the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool 63. This tool has been judged suitable to be used in systematic literature reviews of effectiveness, had fair inter-rater agreement in individual domain scoring and excellent agreement in final grade assigned to among raters and has been reported to have content and construct validity 64. The questions on blinding were not applicable for this topic. Nine articles were assessed with this checklist.

- Checklist for qualitative studies: Methodological quality of studies on the evaluation of patient participation. This checklist is based on the detailed questions of the CASP qualitative checklist. The CASP checklists have been evaluated, pilot tested in workshops, including feedback and review of materials, using successively broader audiences. Weak, moderate and strong ratings were assigned based on the number of ‘yes answers’ 65. Seven qualitative articles were assessed with this checklist.

Strong, moderate or weak final ratings were given based on predefined criteria. Quality assessment tools were piloted with 10 articles by the reviewers and differences in assessment were discussed. Disagreements in final ratings were discussed with a fourth reviewer (FGS).

Data extraction and analyses

Data extraction was carried out for all included articles by the first author (FW) in evidence tables. For every article, general characteristics and the type of medication review were extracted. Secondly, the description of patient participation was extracted for four components, when available, as follows:

Level of participation according to Thompson 7 (see Table 1);

Type of information given by the patient for the medication review;

Kind of consultation by the professional to the patient on the medication;

Evaluation of the patient participation.

Qualitative studies are described separately in overview tables with the description and evaluation of the patient participation. When present, data on the effects of patient participation was collected, specifically on DRPs and possible other outcomes. All data were analyzed in a descriptive manner for the results section and summarized in overview tables.

Results

General characteristics of publications

The authors who reviewed all titles and abstracts, reached strong agreement (Cohen's κ = 0.73). General characteristics of all 37 included publications are presented in Table 2 17–53. All studies described medication reviews, but none of the studies was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) on the effectiveness of patient participation. In total, 30 studies were of a quantitative nature with different study designs, six publications had qualitative designs. Half of the studies were carried out in Europe, mainly the UK, the Netherlands and Norway, the other half were mainly from the USA and Australia. Almost all studies were carried out in the elderly with a variety of risk factors for medication problems, such as polypharmacy, multi-morbidity, recent hospital admission or specific diseases. More than a third of the quantitative studies were small scale or pilot studies with less than 100 participants. The majority of the medication reviews were carried out by pharmacists or pharmacists in cooperation with general practitioners (GPs).

Table 2.

General characteristics of the included publications

| Reference | Study design | Patient characteristics | Setting | MR carried out by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leendertse et al. [33] | Open controlled | 674 elderly, using ≥5 drugs, at risk for hospital admission | Home dwelling in primary care | Pharmacists and GPs |

| Kilcup et al. [28] | Retrospective | 494 elderly, at risk for hospital readmission | Home dwelling recently discharged from hospital | Pharmacists |

| Olsson et al. [39] | Randomized controlled | 150 elderly, using ≥5 drugs | Home dwelling recently discharged from hospital | GPs |

| Akazawa et al. [17] | Prospective intervention | 508 elderly | Home dwelling | Pharmacists |

| Kwint et al. [30] | Cross-sectional | 155 elderly, using ≥5 drugs | Home dwelling visiting community pharmacists | Pharmacists and GPs |

| Elliot et al. [19] | Prospective randomized | 80 elderly, using ≥2 drugs | Home dwelling referred to Aged Care Assessment Teams | Pharmacists or GPs |

| Willoch et al. [50] | Prospective randomized | 77 elderly rehabilitation patients, using ≥3 drugs | Patients admitted to a rehabilitation ward | Clinical pharmacist |

| Stewart et al. [47] | Observational case series | 219 adults | Ambulatory care patients | Pharmacists |

| Swain [48] | Prospective case series | 56 elderly neurological patients | Ambulatory neurologic patients | Pharmacists |

| Sheridan et al. [45] | Qualitative | 27 patients with ≥1 risk factors for drug problems | Independently living patients | Pharmacists |

| Lam [31] | Cross-sectional | 43 adults and elderly, with ≥1 chronic disease, using ≥4 drugs | Patients in an on-going RCT in pharmacies | Pharmacists |

| Niquille et al. [38] | Cross-sectional | 85 elderly cardiovascular patients, using ≥1 cardiovascular drugs | Home dwelling outpatients visiting community pharmacies | Pharmacists |

| Granas et al. [21] | Retrospective evaluation | 73 elderly, using ≥2 diabetic type II drugs | Diabetic type II patients visiting the pharmacy | Pharmacist |

| Hernandez et al. [24] | Observational | 35 middle-aged and elderly heart transplantation patients | Hospitalized heart transplantation patients | Pharmacist |

| Hugtenburg et al. [25] | Controlled intervention | 715 elderly, using ≥5 drugs | Patients discharged from hospital | Pharmacists |

| Karapinar-Carkit et al. [27] | Prospective observational | 262 pulmonology patients, using ≥1 drugs | Patients discharged from the pulmonology ward | Pharmacists |

| Pindolia et al. [41] | Retrospective analysis | 520 elderly, ≥2 chronic diseases, using ≥2 drugs | Primary care | Pharmacists |

| Latif et al. [32] | Qualitative | Purposeful sample of 54 adult and elderly | Patients counselled at community pharmacies | Pharmacists |

| Moultry et al. [34] | Cross-sectional | 30 elderly, 60% is using ≥7 drugs | Patients identified for medication management services | Pharmacists |

| Bissell et al. [52] | Qualitative | 49 coronary heart disease patients | General practice patients recruited within an RCT | Pharmacists |

| MEDMAN [53] | Randomized controlled | 1493 coronary heart disease patients | General practice patients | Pharmacists |

| Salter et al. [42] | Qualitative | 29 elderly | Hospitalized patients recruited within an RCT | Pharmacists |

| Nguyen et al. [37] | Prospective uncontrolled | 24 elderly, ≥1 risk factor for medication misadventure | Patients discharged from hospital | Pharmacists |

| Viktil et al. [49] | Prospective multicentre | 96 hospitalized elderly, using mean 4.7 drugs | Hospitalized patients; internal medicine and rheumatology | Pharmacists |

| Sorensen et al. [21] | Randomized controlled | 400 patients with ≥1 risk factor for inappropriate medication use | Community dwelling patients (rural and urban) | Pharmacists and GPs |

| Griffiths et al. [22] | Pre-post test + cross-sectional | 24 elderly; diminished knowledge/management of medication | Patients receiving regular community nursing care | Community nurses |

| Petty et al. [40] | Qualitative | 18 elderly, using mean 5.5 drugs | Ambulatory patients attending a medicine review clinic | Pharmacists |

| Naunton et al. [36] | Randomized controlled | 121 elderly, using ≥4 drugs | Discharged from hospital | Pharmacists |

| Gilbert et al. [20] | Implementation trial | 1000 patients at risk for DRPs | Community dwelling patients identified by GPs | Pharmacists and GPs |

| Zermansky et al. [51] | Randomized controlled | 1188 elderly using ≥1 drugs | Community dwelling patients visiting GPs | Pharmacists |

| Jameson et al. [26] | Randomized controlled | 168 patients, using ≥5 drugs | Ambulatory care patients | Pharmacists and GPs |

| Krska et al. [29] | Randomized controlled | 332 elderly, with ≥2 chronic diseases, using ≥4 drugs | Ambulatory care patients | Pharmacists |

| Sellors et al. [44] | Randomized controlled | 132 elderly, using ≥4 drugs | Patients visiting GPs | Pharmacists |

| Grymonpre et al. [23] | Prospective randomized controlled | 135 elderly, using ≥2 drugs | Community dwelling ambulatory care patients | Pharmacists |

| Chen et al. [18] | Qualitative | 25 patients referred for medication review | Patients from community pharmacies and GPs | Pharmacists |

| Nathan et al. [35] | Qualitative | 20 elderly or middle-aged, using long term medication | Patients who had 3–9 months ago a medication review | Pharmacists |

| Schneider et al. [43] | Prospective uncontrolled and qualitative | 39 elderly, using mean 6 drugs | Housebound patients, referred by GP | Pharmacists |

DRP, drug related problem; GP, general practitioner; MR, medication review; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Of the 30 articles assessed with the checklist for quantitative studies on description and evaluation of patient participations, 20 articles had a final moderate rating, five a strong rating and five a weak rating. All but one of the qualitative studies were assessed with a strong rating. Of the nine articles that were assessed with the quality assessment for effects of patient participation, five articles had a moderate and four a weak rating.

Type of patient participation

The type of patient participation in medication reviews has been summarized in Table 3 for quantitative studies and in Table 4 for qualitative studies. Overall, the description of the involvement of patients in the medication review process in all publications was minimal. Only studies in which the patient gave information to the professional (level 2 in Table 1) were found.

Table 3.

Type of patient participation in medication reviews – quantitative studies

| Reference | Type of communication and by whom | Information given by patient to professional | Consultation by professional | Evaluation of patient participation | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leendertse et al. 33 | Interview by pharmacist, follow-up of plan by GP and follow-up in time by pharmacist |

|

Follow-up evaluation of the advised pharmacotherapy changes as agreed with the patient in the pharmaceutical care plan | – | Moderate |

| Kilcup et al. 28 | Telephone interview with pharmacist |

|

Opportunity to ask questions on:

|

– | Moderate |

| Olsson et al. 39 | Home visit by study nurse |

|

Written drug regimen was provided to enable patient participation | – | Weak |

| Akazawa et al. 17 | Visit at pharmacy (brown bag method) |

|

|

|

Moderate |

| Kwint et al. 30 | Home-visit by community pharmacist |

|

Not described | – | Strong |

| Elliot et al. 19 | Home-visit by clinical pharmacist or GP |

|

Not described |

|

Strong |

| Willoch et al. 50 | Interview with standardized form during hospital stay and follow-up home visit by clinical pharmacist |

|

Targeted counselling talk on medications and medication changes by pharmacist | – | Moderate |

| Stewart et al. 47 | Interview at care centre by (student-)pharmacist |

|

Not described | – | Weak |

| Swain 48 | Interview at clinic by pharmacist |

|

Education and counselling on medication while ensuring safety and effectiveness |

|

Moderate |

| Lam 31 | Web-cam enabled video-conferencing by pharmacist |

|

|

|

Moderate |

| Niquille et al. 38 | Interview at the pharmacy by community pharmacist |

|

Not described | – | Weak |

| Granas et al. 21 | Interview at the pharmacy by community pharmacist |

|

Medication advice on paper form |

|

Moderate |

| Hernandez et al. 24 | Interview in hospital with standardized service questionnaire by hospital pharmacist |

|

|

|

Moderate |

| Hugtenburg et al. 25 | Counsel at home, in pharmacy or by phone by pharmacist |

|

|

40% of the patients mentioned a medication problem or raised questions | Moderate |

| Karapinar-Carkit et al. 27 | Counselling at discharge by pharmaceutical consultants |

|

Education | – | Moderate |

| Pindolia et al. 41 | Telephone contact by pharmacist and/or GP |

|

|

|

Strong |

| Moultry et al. 34 | Home-visit by consultant pharmacist |

|

|

|

Moderate |

| MEDMAN 53 | Consultation according to pharmacist-determined patient need |

|

Not described | Not described | Weak |

| Nguyen et al. 37 | Home visit 2 days after discharge by pharmacist |

|

Education on medication knowledge | In 73/98 of identified DRPs the information given by the patient was new to the GP | Weak |

| Viktil et al. 49 | Interview at hospital by pharmacist |

|

Not described |

|

Moderate |

| Sorensen et al. 46 | Home visit by pharmacist and consult with GP |

|

Not described | – | Moderate |

| Griffiths et al. 22 | Interview at unknown location by community nurse |

|

|

– | Moderate |

| Naunton et al. 36 | Home visit 5 days after discharge by pharmacist |

|

|

|

Moderate |

| Gilbert et al. 20 | Home visit by community pharmacist and follow-up by GP |

|

|

|

Moderate |

| Zermansky et al. 51 | Home visit community pharmacist and follow-up by GP |

|

Not described, however negotiation with the patient is mentioned in the methods |

|

Strong |

| Jameson et al. 26 | 1. telephone questionnaire 2. Interview in GP office by GP 3. Counselling by GP |

|

|

70% of consult group patients said that they benefited from the consult

|

Strong |

| Krska et al. 29 | Home visit by pharmacist |

|

Not described | – | Moderate |

| Sellors et al. 44 | Interview at GP office by pharmacist |

|

Not described | – | Moderate |

| Grymonpre et al. 23 | Home visit by trained staff or volunteers Patient counselling by physician |

|

|

– | Moderate |

| Schneider et al. 43 | Home visit by community pharmacist |

|

When needed, advice on medication and follow-up visit |

|

Moderate |

ADE, adverse drug effects; DRPs, drug related problems; GP, general practitioner.

Table 4.

Type of patient participation and evaluation in medication reviews – qualitative studies

| Reference | Type of communication and by whom | Information given by patient to professional | Consultation by professional | Process or evaluation outcomes | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheridan et al. 45 | Interview in pharmacy by pharmacist |

|

Education |

|

Strong |

| Latif et al. 32 | Home visits by pharmacist |

|

Education |

|

Strong |

| Bissel et al. 52 | Consultation with pharmacist |

|

Not described |

|

Strong |

| Salter et al. 42 | Home visits by pharmacist |

|

Advice, information, and instruction on medicines |

|

Strong |

| Petty et al. 40 | Interview in clinic by clinical pharmacist |

|

Explanation, not further defined |

|

Strong |

| Chen et al. 18 | Interview in pharmacy by clinical pharmacist |

|

Not described |

|

Moderate |

| Nathan et al. 35 | Interview in pharmacy by pharmacist |

|

Not described |

|

Strong |

OTC, over the counter medicines; MUR, medication use review.

Of the 37 publications, 14 studies included home visits, 14 included patient interviews at the pharmacy or in the GP office, four studies involved patients during or at discharge of their hospital stay and five studies used mixed or other methods to involve the patient. Communication with the patient, especially as preparation before the medication review, was most often carried out by the pharmacist or jointly by the pharmacist and GP. Furthermore, one third of the studies mentioned the duration of the patient contact with the health care professional. The time investment ranged between 15–90 min per patient.

Information exchange between patient and health care professional

In all studies patients provided information about their actual drug use. Additional information included knowledge about the medicines they used, adverse drug events, allergies, adherence and compliance, perceived effectiveness, practical or management problems, lifestyle and social support related, hoarding problems and attitude towards certain medicines.

Health care professionals counselled patients often about proposed changes in medication, education on their medication, lifestyle or health problems and gave follow-up instructions for medication monitoring, laboratory tests or new visits.

Evaluation of patient participation

In some studies the involvement of patients during medication reviews was evaluated. Information on actual drug use often added new information to the records, e.g. on prescribed drugs, over the counter (OTC) drugs, compliance, adherence or other drug user problems 23,24,27,30,37,48. Several studies carried out a satisfaction survey among patients who participated in medication review programmes. The majority of the patients were satisfied with the review services and indicated to have increased knowledge and were able to ask questions about their medications. Two British qualitative studies 38,48 observed that patients were not actively involved in the consultations with pharmacists for their medication review and asked very few questions. Furthermore, in three qualitative studies 40,42,52, patients called on the higher authority of the GP or specialist above the pharmacists to discuss their medicines (Table 4).

Effects of patient participation

The effects of patient participation in medication reviews on DRPs or other patient outcomes have been described in nine studies (Table 5) 20,26,27,29–31,39,49,50. Of all DRPs identified, 27% to 73% were found as a result of a patient interview. Many of these problems would not have been identified if only medication or medical records were used. In two Dutch studies 27,30, the DRPs identified in the interviews were also assigned a higher priority or the recommendations based on patient information were more often implemented than problems identified through medication records or in the medical history. Some other studies mentioned the type of DRPs, which was interpreted as originating from the patient interview 21,23,24,37. However, these results are not included in this literature review to answer the effects of research questions, because it was not described how and if patients' involvement led to these effects. The studies that showed effects on DRPs were assessed with higher quality on description and evaluation of patient participation than studies that reported no effect data.

Table 5.

Effectiveness of patient participation in medication reviews – quantitative studies

| Reference | Type of patient participation | Outcomes | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olsson et al. 39 | Information giving on actual drug use and compliance, during a home visit from a study nurse. Patients were enabled to participate, they received a current and comprehensive medication record | No difference in QoL between the group that received a medication record to enable participation and the group that did not Only 8 of 21 returned medication records were used, with accompanying messages listing forgetfulness, feeling unaccustomed to participating and fear of causing trouble |

Weak |

| Kwint et al. 30 | Information giving on actual drug use, during a home visit from a community pharmacist | 27% of all identified DRPs were identified through patient interview and were assigned a higher priority DRPs identified during patient interviews were more frequently assigned a high priority, associated with recommendations for drug change and were implemented recommendations for drug change |

Moderate |

| Willoch et al. 50 | Information giving on actual drug use, knowledge, adverse events, and efficacy during hospital stay and follow-up home visit by clinical pharmacist on post-discharge effects | 30% of all DRPs at admission were identified through patient interviews, mainly medication chart errors, compliance problems and adverse drug reactions Many DRPs identified during the home visits were compliance problems. 20% of DRPs were related to patient knowledge and skills (derived from home visit) |

Weak |

| Lam 31 | Information giving through web-cam enabled video-conferencing on actual drug use, awareness of treatment goals and adherence | The most prevalent patient-centred DRP was lifestyle-related non-adherence (40/43–93%). Non-adherence to medications was present in 32/43 (74.4%), with forgetfulness as most frequently cited | Weak |

| Karapinar-Carkit et al. 27 | Information giving on actual drug use and DRPs, at a counselling at discharge by pharmacist consultants | With patient counselling, 8.8% more patients benefited in correction of discrepancies (interventions in 72.5% vs. 63.7%). 9.1% more patients benefited in optimizing the pharmacotherapy (interventions in 76.3% vs. 67.2%) | Moderate |

| Viktil et al. 49 | Information giving on actual drug use and drug(problem) handling during an interview with the pharmacist in the hospital | 39.9% of total DRPs were found during the interview, significantly more DRPs were found in the interviewed group vs. the non-interviewed group | Moderate |

| Gilbert et al. 20 | Information giving on actual drug use and knowledge with the purpose of an informed choice during a home-visit by community pharmacist and follow-up by GP. | On average 2.5 DRPs were identified, of which 20% related to patient knowledge and skills | Weak |

| Jameson et al. 26 | Information giving on adverse events and the understanding of medications during a telephone interview, face-to-face interview with GP and follow-up counselling by the GP. | 73% of the interventions were recognized only through patient interview (unplanned outcome of the study). | Moderate |

| Krska et al. 29 | Information giving on actual drug use and effectiveness during home-visit by pharmacists. | PCIs were identified in 29.4% of the cases during the patient interview. Of all the PCIs, 21% were resolved by information found in notes and 8.5% in patient interviews | Moderate |

DRP, drug related problem; GP, general practitioner; PCI, pharmaceutical care issue; QoL, quality of life.

One study found no difference in quality of life after the medication review between patients who were enabled to participate and control patients. However, in this study very few patients actively participated in the medication review process and the sample size was too small to assess quality of life differences 39.

There was no difference in effects or level of patient involvement between different care settings, e.g. hospital or community, or for specific patient groups vs. less specific, general polypharmacy or multi-morbidity patients.

Discussion

The type of patient participation commonly practiced in the studies reviewed was information giving and was often the starting point in a medication review. Other types of patient participation were not found. The information given by the patient was mainly on actual drug use and adherence problems. In most studies the professional was a pharmacist who interviewed or counselled patients at home, in the pharmacy or in the hospital. The involvement of patients led to identification of more drug related problems. These DRPs were considered more relevant, had a higher priority and treatment recommendations based on these problems had a better implementation rate. Both patients and professionals indicated that they were satisfied with the patient participation. Some studies suggested increased medication knowledge and patients' understanding.

The effects of patient participation are hardly studied and poorly described in the current literature. We found no evidence that patient involvement in medication reviews went further than information exchange during dialogues or interviews between patients and caregiver. It remains unclear how patients participate in subsequent stages of the medication review with regard to the sharing of information, decision making, counselling and implementation of possible medication changes.

The exact contribution of patient participation to the effects of the study was mostly unclear. Studies with higher quality often reported effects of patient participation on the identification of DRPs. Weaker quality studies reported good patient satisfaction, increased medication knowledge and patient understanding. These outcomes, however, were measured in surveys with low response rates, which could have led to response bias.

In national and international guidelines, patient participation in a medication review process is a prerequisite for a successful medication review 5,10,11. However, guideline recommendations to involve patients are not based on evidence but on prevailing societal considerations and expert opinions 11. Apparently, there is a discrepancy between patient centredness and evidence-based care. Patient participation is a concept that already arises from the 1960s, when the consumer protection rights were introduced in the US Congress; ‘the right to safety, the right to be informed, the right to choose and the right to be heard’ 54. This also implicates that patient participation is more a right and largely justified on humane reasons than an evidence-based means to improve treatment outcomes, as has been questioned before 55,56.

The use of medication reviews, particularly with active patient involvement, as an intervention to improve treatment results is a fairly recent development in pharmaceutical care. This may partly explain the absence of good quality literature clearly describing involvement of patients in medication reviews and its effects. Furthermore, implementing patient participation is strongly dependent on overcoming health care professionals' obstacles such as time constraints and finances, societal norms and the tendency of caregiver to maintain control 1. Particularly, the time investment to involve patients in the medications reviews process is considerable and, hence, costly. In this literature review, it varied between 15–90 min for patient interviews aimed only to inform caregivers on actual drug use and experiences.

As compared with younger patients, the elderly are known to participate less in care and self-management and have different preferences for involvement and decision making 57. This literature review consisted of studies almost solely in elderly subjects, which are the main target group for medication reviews. This means that the patient group described in this literature study is already less prone to participate and to a lesser extent wants to be involved in medical decisions. Not all patients want to or can be involved and the extent to which involvement is useful may depend on age, disease severity, acuteness of the disease, cognitive state, comorbidity, health literacy, socio-economic status, type and impact of decision, attitudes towards medication and prevention, patient–professional relationships and other personal preferences 1,7. Previous research also indicated that patients have a desire to participate in the consultation, but do not always feel a need to be involved in medical decision and patient involvement was limited to information sharing 56,58–60. This means that we may have to reconsider how and which patients should be involved in a medication review.

Data on the gain of patient participation in terms of effects is scarce and existing literature has a weak quality. The evidence for the effects on clinical patient outcomes such as quality of life, hospitalization and mortality of medication reviews themselves is limited 61. Patient participation in consultations has been suggested to improve, for example, adherence, long-term effects of pharmacotherapy and thereby indirect patient outcomes 3,4. However no evidence was found for this in the context of medication reviews.

There are some limitations to discuss. The taxonomy by Thompson 7 used in this study is not very discriminative. Other in-between combinations may be applicable. However others also recognize that labelling these would not be very useful since one always deals with specific situational contexts 62. This emphasizes the complexity of studying patient participation.

Although an extensive search strategy in four literature databases was used and an additional hand search in reference lists was performed, relevant articles may have been missed.

The complexity of patient participation in medication reviews makes it difficult to design comparative studies. Moreover, it is difficult to measure the specific contribution of patient participation on treatment outcomes. To study whether, for example, shared decision making is carried out in practice, a qualitative study design may be needed. With qualitative observational research one could study whether patients really influence the content and structure of the interaction of a consultation or decision, like Street & Millays' definition of patient participation 6.

To study whether patient participations also results in effects, future research should focus on designs, possibly comparative, with a mixed character with relevant, quantitative patient outcomes such as adherence, quality of life, adverse drug events and patient satisfaction and qualitatively on the level of involvement of patients by observing consultations.

Conclusion

To conclude, patient participation in medication reviews is important to gain information about patient preferences and relevant drug related problems. Patient participation is not common and not always desirable in decision making in the last phase of a medication review. As there is often no clear decision as with treatment counselling and the target group for medication reviews, the vulnerable elderly, do not always have the wish to be involved in the actual decision. Patient satisfaction and knowledge seem to improve when patients are more involved, however no effects in health outcomes have been observed.

Patient participation in medication reviews is desirable and may improve patient outcomes, but is presently based on expert opinions and ethical considerations for modern health care, rather than on evidence. Considering the time investment and limited evidence of patient participation in medication reviews efficient methods targeted at the right patients seem appropriate. The profit of higher levels of patient communication and shared decision making is, until now, not supported by evidence of its effectiveness. Since patient involvement limited to information sharing seems more appropriate, efficient methods to involve patients in medication reviews are topics for future research and practice innovations. In this way, clinical medication reviews will become more feasible for GPs and pharmacists.

Practice implications

Our results may have potential implications for pharmacists, GPs or other physicians who perform medication reviews. Patient participation at the level of information giving may improve information of the professionals and identification of DRPs and may contribute to improved patient knowledge, understanding and patient satisfaction. Physicians and pharmacists have to keep in mind that involvement of patients during decision making is not primarily evidence-based to improve the outcomes of both medication review outcomes as well as patient outcomes and is not always needed in this type of decision. Based on the literature, information giving participation during medication reviews improves the medication review process and identification of drug related problems. However evidence regarding the effectiveness of higher levels are lacking and might not be needed at all times and at all costs.

Author contributions

FW, JGH, FGS and PJME designed the study and research questions. FW and PJME performed the title and abstract screening and FW performed the full text selection. FW, JGH, FGS and PJME performed the quality assessment and FW carried out the data extraction. FW, JGH, FGS and PJME prepared the manuscript.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare FW had support from a research grant by the Dutch Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The authors thank the Dutch Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) for financial support and I. Jansma for assistance with the search strategy.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Appendix S1

PubMed search strategy

References

- Longtin Y, Sax H, Leape LL, Sheridan SE, Donaldson L, Pittet D. Patient participation: current knowledge and applicability to patient safety. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:53–62. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Patients for patients safety. Last update 2013. Available at http://www.who.int/patientsafety/patients_for_patient/en/ (last accessed 19 April 2013)

- Stevenson FA, Cox K, Britten N, Dundar Y. A systematic review of the research on communication between patients and health care professionals about medicines: the consequences for concordance. Health Expect. 2004;7:235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts MM, Talsma J, Brouwers JR, de Gier JJ. Medication review and reconciliation with cooperation between pharmacist and general practitioner and the benefit for the patient: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74:16–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on Medicines Partnership and The National Collaborative Medicines Management Services Programme. Room for Review: A Guide to Medication Review: the Agenda for Patients, Practitioners and Managers. London: Medicines Partnership; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Street RL, Jr, Millay B. Analyzing patient participation in medical encounters. Health Commun. 2001;13:61–73. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1301_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AG. The meaning of patient involvement and participation in health care consultations: a taxonomy. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1297–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezreh T, Laws MB, Taubin T, Rifkin DE, Wilson IB. Challenges to physician-patient communication about medication use: a window into the skeptical patient's world. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:11–18. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S25971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia Ltd. 2011. Guidelines for pharmacists providing Home Medicines Review (HMR) services.

- Nederlands Huisarts Genootschap (NHG) 2012. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen. Utrecht.

- Martinez LS, Schwartz JS, Freres D, Fraze T, Hornik RC. Patient-clinician information engagement increases treatment decision satisfaction among cancer patients through feeling of being informed. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:384–390. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, Knowles SB, Lavori PW, Lapidus J, Vollmer WM the BOAT Study Group. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:566–577. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0907OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE., Jr Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne W, Blenkinsopp A, Seal R The National Prescribing Center. 2008. A guide to Medication Review. Medicines Partnership Programme.

- Akazawa M, Nomura K, Kusama M, Igarashi A. Drug utilization reviews by community pharmacists in Japan: identification of potential safety concerns through the Brown Bag Program. Value Health Reg Issues. 2012;1:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Britten N. ‘Strong medicine’: an analysis of pharmacist consultations in primary care. Fam Pract. 2000;17:480–483. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.6.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott RA, Martinac G, Campbell S, Thorn J, Woodward MC. Pharmacist-led medication review to identify medication-related problems in older people referred to an Aged Care Assessment Team: a randomized comparative study. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:593–605. doi: 10.1007/BF03262276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert AL, Roughead EE, Beilby J, Mott K, Barratt JD. Collaborative medication management services: improving patient care. Med J Aust. 2002;177:189–192. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granas AG, Berg C, Hjellvik V, Haukereid C, Kronstad A, Blix HS, Kilhovd B, Viktil KK, Horn AM. Evaluating categorisation and clinical relevance of drug-related problems in medication reviews. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32:394–403. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths R, Johnson M, Piper M, Langdon R. A nursing intervention for the quality use of medicines by elderly community clients. Int J Nurs Pract. 2004;10:166–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2004.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grymonpre RE, Williamson DA, Montgomery PR. Impact of a pharmaceutical care model for non-instutionalised elderly: results of a randomised, controlled trial. Int J Pharm Pract. 2001;9:235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez MJ, Montero HM, Font NI, Domenech ML, Merino SV, Poveda Andres JL. Assessment of a reconciliation and information programme for heart transplant patients. Farm Hosp. 2010;34:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.farma.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugtenburg JG, Borgsteede SD, Beckeringh JJ. Medication review and patient counselling at discharge from the hospital by community pharmacists. Pharm World Sci. 2009;31:630–637. doi: 10.1007/s11096-009-9314-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson JP, VanNoord GR. Pharmacotherapy consultation on polypharmacy patients in ambulatory care. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:835–840. doi: 10.1345/aph.10259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede SD, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt PM. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1001–1010. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilcup M, Schultz D, Carlson J, Wilson B. Postdischarge pharmacist medication reconciliation: impact on readmission rates and financial savings. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2013;53:78–84. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2013.11250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, Jamieson D, Hansford D, Duffus PR, Downie G, Seymour DG. Pharmacist-led medication review in patients over 65: a randomized, controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing. 2001;30:205–211. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwint HF, Faber A, Gussekloo J, Bouvy ML. The contribution of patient interviews to the identification of drug-related problems in home medication review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37:674–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2012.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam A. Practice innovations: delivering medication therapy management services via videoconference interviews. Consult Pharm. 2011;26:764–773. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2011.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latif A, Pollock K, Boardman HF. The contribution of the Medicines Use Review (MUR) consultation to counseling practice in community pharmacies. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leendertse AJ, de Koning GH, Goudswaard AN, Belitser SV, Verhoef M, de Gier HJ, Egberts TCG, van den Bemt PMLA. Preventing hospital admissions by reviewing medication (PHARM) in primary care: an open controlled study in an elderly population. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2013;38:379–387. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moultry AM, Poon IO. Perceived value of a home-based medication therapy management program for the elderly. Consult Pharm. 2008;23:877–885. doi: 10.4140/tcp.n.2008.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan A, Goodyer L, Lovejoy A, Savage I. Patients' view of the value of ‘brown bag’ medication reviews. Int J Pharm Pract. 2000;8:298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Naunton M, Peterson GM. Evaluation of home-based follow-up of high-risk elderly patients discharged from hospital. J Pharm Pract Res. 2003;33:176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A, Yu K, Shakib S, Doecke CJ, Boyce M, March G, Anderson BA, Gilbert AL, Angley MT. Classification of findings in the home medicines reviews of post-discharge patients at risk of medication misadventure. J Pharm Pract Res. 2007;37:111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Niquille A, Bugnon O. Relationship between drug-related problems and health outcomes: a cross-sectional study among cardiovascular patients. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32:512–519. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson IN, Runnamo R, Engfeldt P. Drug treatment in the elderly: an intervention in primary care to enhance prescription quality and quality of life. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2012;30:3–9. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2011.629149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty DR, Knapp P, Raynor DK, House AO. Patients' views of a pharmacist-run medication review clinic in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:607–613. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pindolia VK, Stebelsky L, Romain TM, Luoma L, Nowak SN, Gillanders F. Mitigation of medication mishaps via medication therapy management. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:611–620. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter C, Holland R, Harvey I, Henwood K. ‘I haven't even phoned my doctor yet.’ The advice giving role of the pharmacist during consultations for medication review with patients aged 80 or more: qualitative discourse analysis. BMJ. 2007;334:1101–1106. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39171.577106.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J, Barber N. Provision of a domiciliary service by community pharmacists. Int J Pharm Pract. 1996;4:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sellors C, Dalby DM, Howard M, Kaczorowski J, Sellors J. A pharmacist consultation service in community-based family practices: a randomized, controlled trial in seniors. J Pharm Technol. 2001;17:264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan J, Butler R, Brandt T, Harrison J, Jensen M, Shaw J. Patients' and pharmacists' perceptions of a pilot Medicines Use Review service in Auckland, New Zealand. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2012;3:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen L, Stokes JA, Purdie DM, Woodward M, Elliott R, Roberts MS. Medication reviews in the community: results of a randomized, controlled effectiveness trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58:648–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Lynch KJ. Identifying discrepancies in electronic medical records through pharmacist medication reconciliation. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2012;52:59–66. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2012.10123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain LD. A pharmacist's contribution to an ambulatory neurology clinic. Consult Pharm. 2012;27:49–57. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2012.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Interview of patients by pharmacists contributes significantly to the identification of drug-related problems (DRPs) Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:667–674. doi: 10.1002/pds.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoch K, Blix HS, Pedersen-Bjergaard AM, Eek AK, Reikvam A. Handling drug-related problems in rehabilitation patients: a randomized study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34:382–388. doi: 10.1007/s11096-012-9623-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zermansky AG, Petty DR, Raynor DK, Freemantle N, Vail A, Lowe CJ. Randomised controlled trial of clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly patients receiving repeat prescriptions in general practice. BMJ. 2001;323:1340–1343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7325.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell P, Blenkinsopp A, Short D, Mason L. Patients' experiences of a community pharmacy-led medicines management service. Health Soc Care Community. 2008;16:363–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project Evaluation Team. The MEDMAN study: a randomized controlled trial of community pharmacy-led medicines management for patients with coronary heart disease. Fam Pract. 2007;24:189–200. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy JF. Special Message to the Congress on Protecting the Consumer Interest. 15-3-1962. Available at http://www.jfklink.com/speeches/jfk/publicpapers/1962/jfk93_62.html (last accessed 19 April 2013)

- Guadagnoli E, Ward P. Patient participation in decision-making. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroe AL, Salkovskis PM, Rees M, Jack T. Information giving and involvement in treatment decisions: is more really better? Psychological effects and relation with adherence. Psychol Health. 2013;28:954–971. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.777964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ, Smith T, Hack TF, Huschka MM, Rummans TA, Clark MM, Diekmann B, Degner LF. Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the Control Preferences Scale. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:688–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher VN, Fried TR, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older adults on patient participation in medication-related decision making. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson PG, Talbot PI, Toneguzzi RC. Self-management, autonomy, and quality of life in asthma. Population Medicine Group 91C. Chest. 1995;107:1003–1008. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.4.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard G, Kidd L, Donaghy E. Preferences for involvement in treatment decision making of patients with cancer: a review of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:299–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkansah N, Mostovetsky O, Yu C, Chheng T, Beney J, Bond CM, Bero L. Effect of outpatient pharmacists' non-dispensing roles on patient outcomes and prescribing patterns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000336.pub2. ): CD000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1:176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Critical appraisal checklists. Qualitative research checklist version 14-10-2010.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

PubMed search strategy