Abstract

Objective

The objective of the present analysis was to determine the publicly funded health care costs associated with the care of breast cancer (bca) patients by disease stage.

Methods

Incident cases of female invasive bca (2005–2009) were extracted from the Ontario Cancer Registry and linked to administrative datasets from the publicly funded system. The type and use of health care services were stratified by disease stage over the first 2 years after diagnosis. Mean costs and costs by type of clinical resource used in the care of bca patients were compared with costs for a matched control group. The attributable cost for the 2-year time horizon was determined in 2008 Canadian dollars.

Results

This cohort study involved 39,655 patients with bca and 190,520 control subjects. The average age in those groups was 61.1 and 60.9 years respectively. Most bca patients were classified as either stage i (34.4%) or stage ii (31.8%). Of the bca cohort, 8% died within the first 2 years after diagnosis. The overall mean cost per bca case from a public payer perspective in the first 2 years after diagnosis was $41,686. Over the 2-year time horizon, the mean cost increased by stage: i, $29,938; ii, $46,893; iii, $65,369; and iv, $66,627. The attributable cost of bca was $31,732. Cost drivers were cancer clinic visits, physician billings, and hospitalizations.

Conclusions

Costs of care increased by stage of bca. Cost drivers were cancer clinic visits, physician billings, and hospitalizations. These data will assist planning and decision-making for the use of limited health care resources.

Keywords: Breast cancer, costs, population-based analysis, disease stage

1. INTRODUCTION

All permanent residents of the province of Ontario (a population of 13.2 million) are covered by a publicly funded health care system. The system pays for hospitalizations, most physician services, and emergency department (ed) services, and for selected prescription medications for the subset of the population more than 65 years of age or receiving social assistance. The provincial government authority collects data about those services and the service providers. These population-level data provide researchers with a unique opportunity to analyze the types of health services delivered within the system.

Breast cancer (bca) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Canadian women1 and has a significant financial impact. In 2014, approximately 24,400 women will have been diagnosed with breast cancer, representing 26% of all new cancer cases in women2. Because health care management for bca occurs across acute care, institutional care, and community settings, significant care and cost is assumed by the public health care system. Identification of the costs and the key resource utilization drivers will assist health system administrators in making informed policy decisions. Unfortunately, very few publications have determined bca lifetime costs in Canada; the reported range is $309–$454 million3,4.

Several recent studies have determined overall costs for several cancers5,6 and have examined utilization and costs of specific modalities of health care, such as home care in colorectal cancer7,8 and home care costs in bca, which were determined and stratified by disease stage9.

The objective of the present analysis was to determine the costs incurred in a publicly funded health care system for the management of bca, by disease stage, in the first 2 years after diagnosis.

2. METHODS

Incident cases of female invasive bca (ICD-9 174.x) diagnosed between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2009, were extracted from the Ontario Cancer Registry. The bca cases in the registry were linked by their encrypted health card number to a spectrum of administrative datasets held at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, an independent notfor-profit organization whose core business is to conduct research that contributes to the effectiveness, quality, equity, and efficiency of health care and health services in Ontario. The Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences Registered Persons Database includes information on patient characteristics (age, sex, etc.). The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care holds data on reimbursements for hospitalizations (inpatient, day surgery), ed visits, physician visits, home care services, long-term care services, and prescription drug claims. Cancer Care Ontario holds data in its activity level reporting (alr) system on cancer services provided in the province (chemotherapy, radiation) through regional cancer centres and most, but not all, of the facilities that administer chemotherapy to patients.

In the present analysis, all health system services that were provided to individuals who met the eligibility criteria and that were reimbursed by the health system were included. All patients were followed from index date to death or to March 31, 2010, whichever came first. A control group selected from a population of women never diagnosed with cancer—that is, women without a record in the provincial cancer registry—were matched by age, income, prior health system use, and region to the women diagnosed with bca. Cases and potential controls had to match exactly on birth year, health region of residence, modified income variable, and resource utilization banda. Income quintile assignment was based on Statistics Canada’s Postal Code Conversion File, pccf+ (version 5E). The income variable was modified to account for potential misclassifications of neighbourhood income quintile derived from postal codes in rural areas. In addition, the Adjusted Clinical Group softwareb was used to assign a resource utilization band score to patients and control subjects alike. Control subjects who had an invalid health card number or who died before the patient’s breast cancer diagnosis date were excluded. The ratio of control subjects to bca patients was up to 5:1.

For patients, bca stage was based on a central staging algorithm that incorporates both pathologic and clinical staging information10. Women in the case group who had an invalid health card number were excluded.

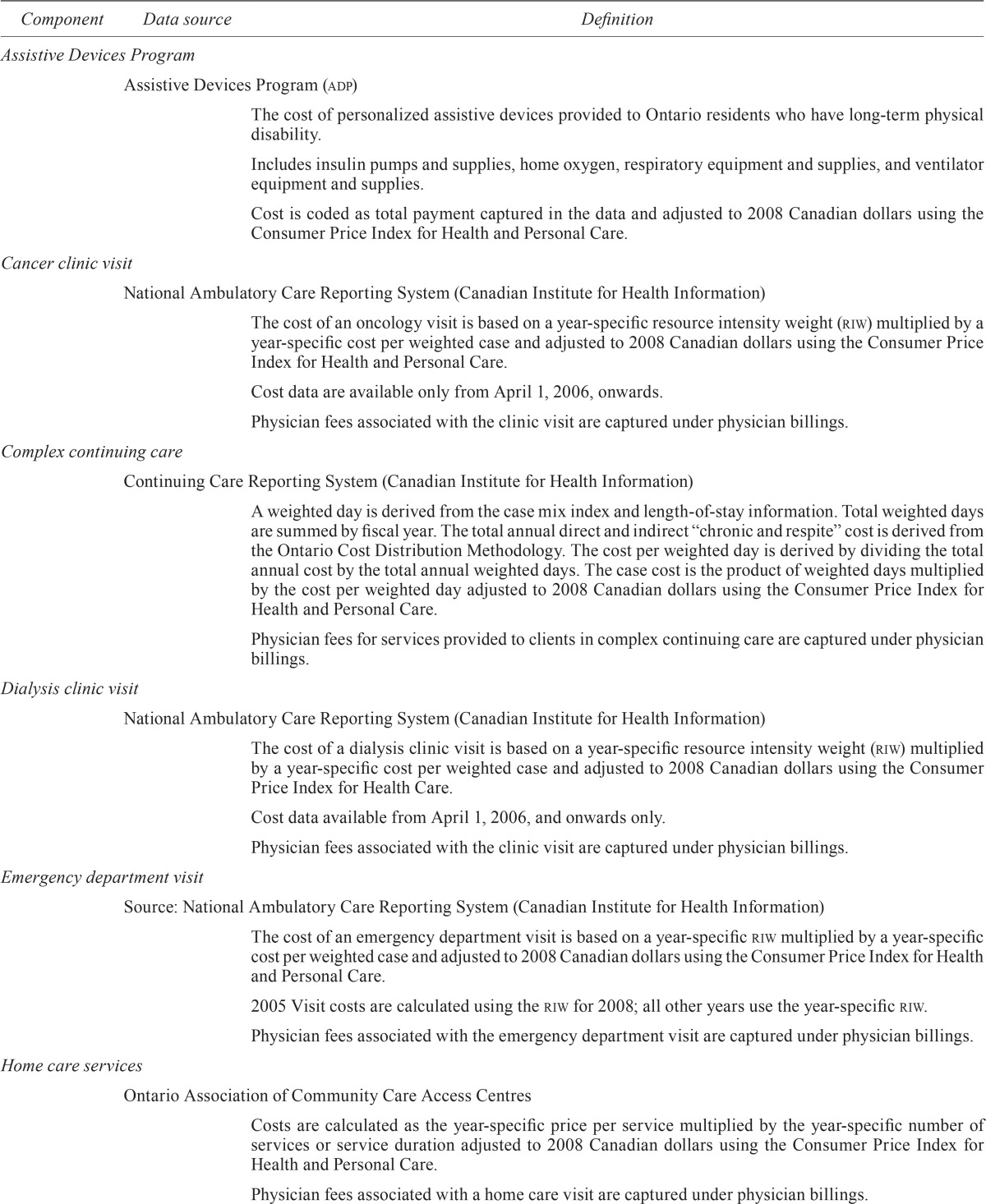

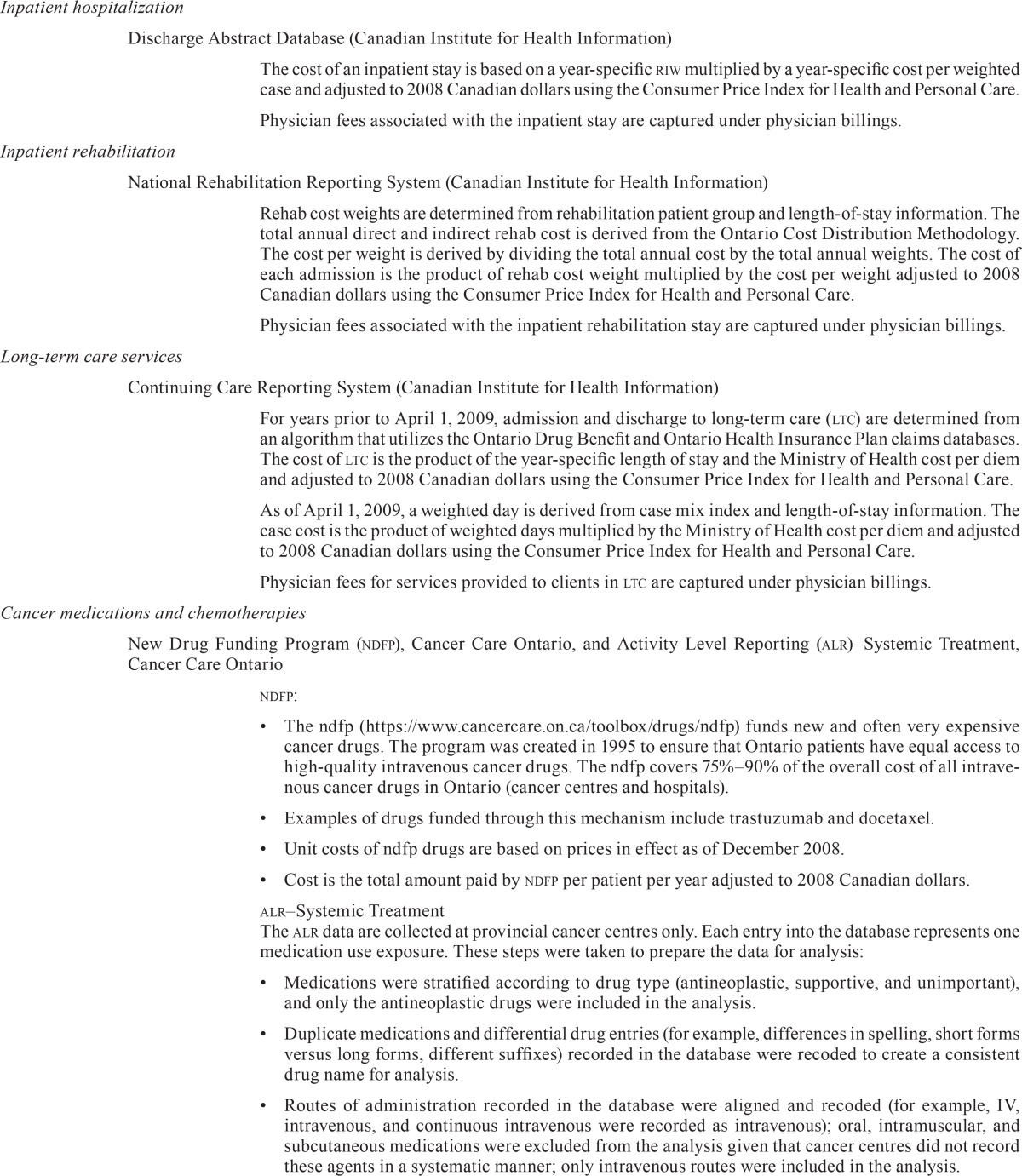

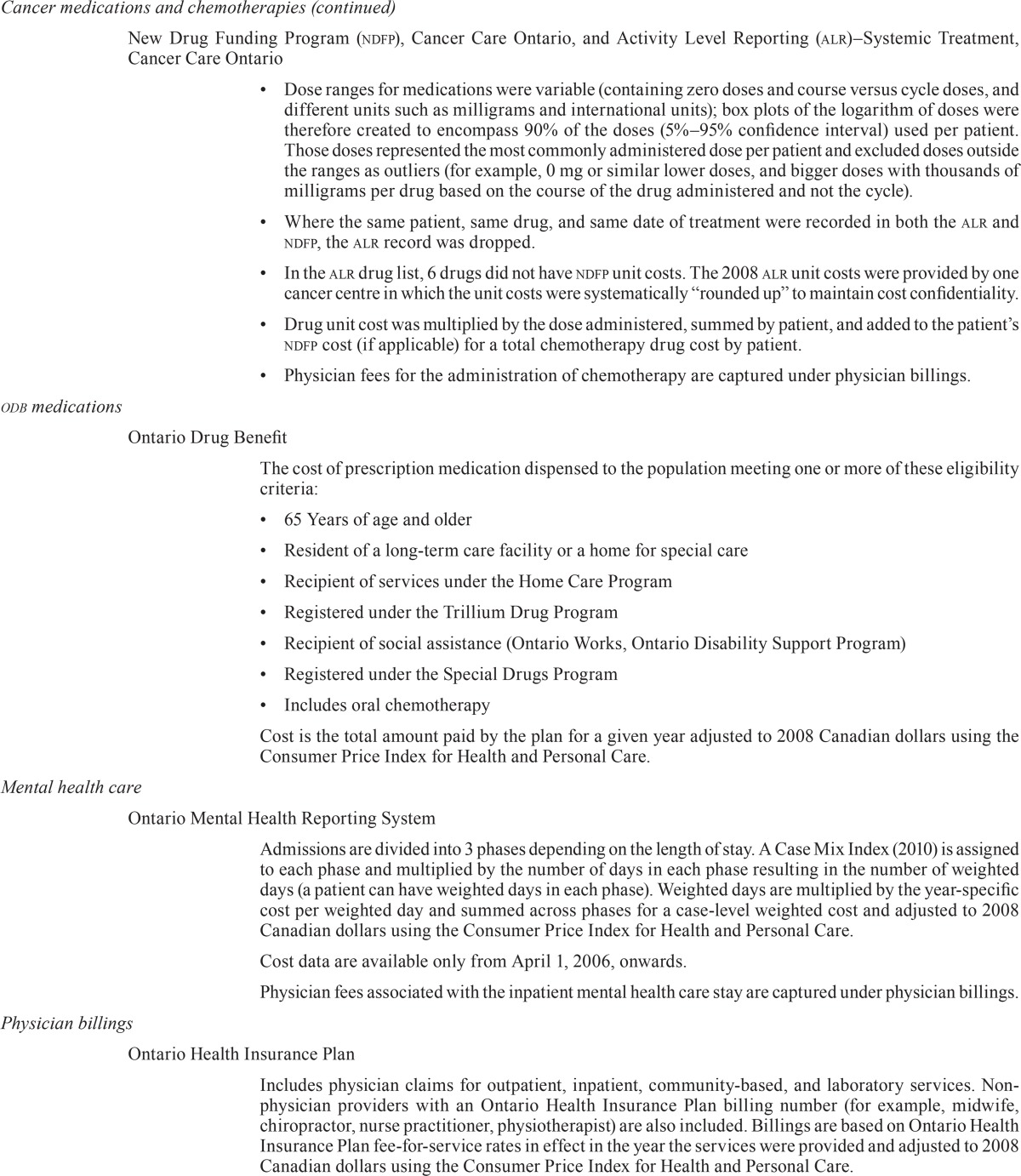

Follow-up periods in the study population were variable because of the varying index dates (2005– 2009). The analysis considered the period of the first 2 years after diagnosis because women newly diagnosed with bca would be likely to have experienced sequential treatment with some combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy during that time. Table i describes the public health system services evaluated in the analysis.

TABLE I.

Source and definition of cost components

| Component | Data source | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Assistive Devices Program | ||

| Assistive Devices Program (adp) | ||

| The cost of personalized assistive devices provided to Ontario residents who have long-term physical disability. | ||

| Includes insulin pumps and supplies, home oxygen, respiratory equipment and supplies, and ventilator equipment and supplies. | ||

| Cost is coded as total payment captured in the data and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the | ||

| Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Cancer clinic visit | ||

| National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (Canadian Institute for Health Information) | ||

| The cost of an oncology visit is based on a year-specific resource intensity weight (riw) multiplied by a year-specific cost per weighted case and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Cost data are available only from April 1, 2006, onwards. | ||

| Physician fees associated with the clinic visit are captured under physician billings. | ||

| Complex continuing care | ||

| Continuing Care Reporting System (Canadian Institute for Health Information) | ||

| A weighted day is derived from the case mix index and length-of-stay information. Total weighted days are summed by fiscal year. The total annual direct and indirect “chronic and respite” cost is derived from the Ontario Cost Distribution Methodology. The cost per weighted day is derived by dividing the total annual cost by the total annual weighted days. The case cost is the product of weighted days multiplied by the cost per weighted day adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. Physician fees for services provided to clients in complex continuing care are captured under physician billings. |

||

| Dialysis clinic visit | ||

| National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (Canadian Institute for Health Information) | ||

| The cost of a dialysis clinic visit is based on a year-specific resource intensity weight (riw) multiplied by a year-specific cost per weighted case and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health Care. | ||

| Cost data available from April 1, 2006, and onwards only. | ||

| Physician fees associated with the clinic visit are captured under physician billings. | ||

| Emergency department visit | ||

| Source: National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (Canadian Institute for Health Information) | ||

| The cost of an emergency department visit is based on a year-specific riw multiplied by a year-specific cost per weighted case and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| 2005 Visit costs are calculated using the riw for 2008; all other years use the year-specific riw. | ||

| Physician fees associated with the emergency department visit are captured under physician billings. | ||

| Home care services | ||

| Ontario Association of Community Care Access Centres | ||

| Costs are calculated as the year-specific price per service multiplied by the year-specific number of services or service duration adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Physician fees associated with a home care visit are captured under physician billings. | ||

| Inpatient hospitalization | ||

| Discharge Abstract Database (Canadian Institute for Health Information) | ||

| The cost of an inpatient stay is based on a year-specific riw multiplied by a year-specific cost per weighted case and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Physician fees associated with the inpatient stay are captured under physician billings. | ||

| Inpatient rehabilitation | ||

| National Rehabilitation Reporting System (Canadian Institute for Health Information) | ||

| Rehab cost weights are determined from rehabilitation patient group and length-of-stay information. The total annual direct and indirect rehab cost is derived from the Ontario Cost Distribution Methodology. The cost per weight is derived by dividing the total annual cost by the total annual weights. The cost of each admission is the product of rehab cost weight multiplied by the cost per weight adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Physician fees associated with the inpatient rehabilitation stay are captured under physician billings. | ||

| Long-term care services | ||

| Continuing Care Reporting System (Canadian Institute for Health Information) | ||

| For years prior to April 1, 2009, admission and discharge to long-term care (ltc) are determined from an algorithm that utilizes the Ontario Drug Benefit and Ontario Health Insurance Plan claims databases. The cost of ltc is the product of the year-specific length of stay and the Ministry of Health cost per diem and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| As of April 1, 2009, a weighted day is derived from case mix index and length-of-stay information. The case cost is the product of weighted days multiplied by the Ministry of Health cost per diem and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Physician fees for services provided to clients in ltc are captured under physician billings. | ||

| Cancer medications and chemotherapies | ||

| New Drug Funding Program (ndfp), Cancer Care Ontario, and Activity Level Reporting (alr)–Systemic Treatment, Cancer Care Ontario | ||

| ndfp: | ||

|

||

| alr–Systemic Treatment | ||

| The alr data are collected at provincial cancer centres only. Each entry into the database represents one medication use exposure. These steps were taken to prepare the data for analysis: | ||

|

||

| odb medications | ||

| Ontario Drug Benefit | ||

| The cost of prescription medication dispensed to the population meeting one or more of these eligibility criteria: | ||

|

||

| Cost is the total amount paid by the plan for a given year adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Mental health care | ||

| Ontario Mental Health Reporting System | ||

| Admissions are divided into 3 phases depending on the length of stay. A Case Mix Index (2010) is assigned to each phase and multiplied by the number of days in each phase resulting in the number of weighted days (a patient can have weighted days in each phase). Weighted days are multiplied by the year-specific cost per weighted day and summed across phases for a case-level weighted cost and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Cost data are available only from April 1, 2006, onwards. | ||

| Physician fees associated with the inpatient mental health care stay are captured under physician billings. | ||

| Physician billings | ||

| Ontario Health Insurance Plan | ||

| Includes physician claims for outpatient, inpatient, community-based, and laboratory services. Non-physician providers with an Ontario Health Insurance Plan billing number (for example, midwife, chiropractor, nurse practitioner, physiotherapist) are also included. Billings are based on Ontario Health Insurance Plan fee-for-service rates in effect in the year the services were provided and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Includes the capitation cost, a monthly payment to physicians for individuals enrolled (rostered) in a family health network or family health organization at least 1 day in a month. The case cost is the product of a base rate and age–sex multiplier. For patients enrolled in a family health organization, a senior-care premium multiplier is added to the age–sex multiplier effective January 1, 2008. Costs are based on capitation rates in effect in the year the services were provided and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Radiation therapist services | ||

| alr–Radiation Planning/Treatment Activity, Cancer Care Ontario; Cancer Care Ontario Data Book 2010–2011, Appen dix E: National Hospital Productivity Improvement Project (published for Cancer Care Ontario’s partner organizations: https://www.cancercare.on.ca/ext/databook/db1011/Appendix/Appendix_E_-_NHPIP_Code_List_.htm); and Salary Scale Analysis for Medical Imaging and Radiation Technologists and Therapists (Canadian Association of Medical Radiation Technologists, 2009). | ||

| The alr–Radiation Planning/Treatment Activity database holds the records of breast cancer patients who received radiation therapy. | ||

| In the alr, each activity associated with planning, treatment, support, and follow-up care for radiation therapy is assigned a National Hospital Productivity Improvement Program code, and each activity code is assigned a workload value, in minutes, representing the average time required to complete the task. | ||

| The assumption was that the radiation therapist was responsible for providing the care listed in the alr patient record—that is, no other provider type was used in calculating the cost of radiation. | ||

| The only planning and treatment activities costed were those associated with breast cancer; planning and treatment activities associated with other cancer types the patient may have concurrently had were excluded. | ||

| The duration of each National Hospital Productivity Improvement Program activity listed for a patient was multiplied by the midrange of radiation therapist hourly rates ($31.61), divided by 60, and summed across a patient to arrive at the total radiation cost adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars. | ||

| The average total radiation therapist cost, by stage at diagnosis and overall, among patients who received any radiation therapy was calculated. | ||

| The cost of equipment, materials, physicist time, and institution overhead and administrative costs are not included. | ||

| Physician fees related to radiation therapy are captured under physician billings. | ||

| Same-day surgery | ||

| Discharge Abstract Database (Canadian Institute for Health Information) | ||

| The cost of day surgery is based on a year-specific riw multiplied by a year-specific cost per weighted case and adjusted to 2008 Canadian dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Health and Personal Care. | ||

| Physician fees associated with the day surgery are captured under physician billings. | ||

Demographic characteristics for the bca and control cohorts were summarized. The overall cost of care for the entire bca population and the cost of care for the matched cohort, the cost per bca patient (by stage) and per control subject, and the cost differences between the groups were calculated. The cost for the bca cohort alive at the end of 2 years was also determined. The cost of each health care resource by each bca patient who used a provincially funded health care resource was calculated, as was the percentage of the health care resource used by disease stage. Finally, the attributable cost for bca patients (after comparison with control subjects) was determined. All cost data are presented in descriptive form (means, medians, standard deviations, and quartiles 1 and 3) over the time horizon of 2 years post-diagnosis using 2008 Canadian dollars. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.).

3. RESULTS

The study included 39,655 bca patients and 190,520 control subjects. Table ii shows that the average age of bca patients was 61.1 years, with most of the cohort being 65 years of age or younger. The bca patients resided predominantly in urban settings. Among the bca patients for whom staging information was available, most were diagnosed with stage i (34.4%) or ii (31.8%) disease. Although not shown in the table, 8% of the bca group (n = 3253) died within 2 years of diagnosis; 2% of the control subjects died during the same period. By stage, the proportion of bca patients who died was 2% (stage i), 5% (stage ii), 8% (stage iii), and 49% (stage iv).

TABLE II.

Demographic information for the study group

| Variable | Value for | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Cases | Controls | |

| Women (n) | 39,655 | 190,520 |

| Age at index date (years) | ||

| Mean | 61.06±14.01 | 60.87±14.06 |

| Median | 60 | 60 |

| Interquartile range | 50–72 | 50–71 |

| Age group at index date [n (%)] | ||

| <45 Years | 4,822 (12.2) | 23,845 (12.5) |

| 45–54 Years | 9,087 (22.9) | 44,109 (23.2) |

| 55–64 Years | 9,890 (24.9) | 47,459 (24.9) |

| 65–74 Years | 8,099 (20.4) | 38,296 (20.1) |

| 75–84 Years | 5,765 (14.5) | 27,311 (14.3) |

| ≥85 Years | 1,992 (5.0) | 9,500 (5.0) |

| Disease stage [n (%)] | ||

| i | 13,628 (34.4) | 65,404 (34.3) |

| ii | 12,602 (31.8) | 60,555 (31.8) |

| iii | 4,765 (12.0) | 22,954 (12.0) |

| iv | 1,552 (3.9) | 7,464 (3.9) |

| Unknown | 7,108 (17.9) | 34,143 (17.9) |

| lhin [n (%)] | ||

| Erie St. Clair | 2,108 (5.3) | 10,145 (5.3) |

| South West | 3,024 (7.6) | 14,520 (7.6) |

| Waterloo Wellington | 2,047 (5.2) | 9,861 (5.2) |

| Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant | 4,730 (11.9) | 22,654 (11.9) |

| Central West | 1,890 (4.8) | 9,223 (4.8) |

| Mississauga Halton | 3,162 (8.0) | 15,157 (8.0) |

| Toronto Central | 3,458 (8.7) | 16,424 (8.6) |

| Central | 4,882 (12.3) | 23,520 (12.3) |

| Central East | 4,670 (11.8) | 22,427 (11.8) |

| South East | 1,706 (4.3) | 8,206 (4.3) |

| Champlain | 3,782 (9.5) | 18,238 (9.6) |

| North Simcoe Muskoka | 1,467 (3.7) | 7,058 (3.7) |

| North East | 1,956 (4.9) | 9,369 (4.9) |

| North West | 740 (1.9) | 3,527 (1.9) |

| Missing | 33 (0.1) | 191 (0.1) |

| Rural [n (%)] | ||

| No | 34,612 (87.3) | 166,252 (87.3) |

| Yes | 5,010 (12.6) | 24,077 (12.6) |

| Missing | 33 (0.1) | 191 (0.1) |

| Income quintile [n (%)] | ||

| Highest | 7,043 (17.8) | 34,359 (18.0) |

| Second highest | 7,673 (19.3) | 37,045 (19.4) |

| Middle | 7,895 (19.9) | 37,421 (19.6) |

| Second lowest | 8,289 (20.9) | 39,623 (20.8) |

| Lowest | 8,696 (21.9) | 41,415 (21.7) |

| Missing | 59 (0.1) | 657 (0.3) |

| Resource utilization band [n (%)] | ||

| None | 452 (1.1) | 2,235 (1.2) |

| Healthy user | 209 (0.5) | 1,022 (0.5) |

| Low | 2,109 (5.3) | 10,323 (5.4) |

| Moderate | 22,034 (55.6) | 106,481 (55.9) |

| High | 9,851 (24.8) | 46,996 (24.7) |

| Highest | 5,000 (12.6) | 23,463 (12.3) |

lhin = Local Health Integration Network.

Table iii shows that, from a public payer perspective, the overall mean cost per bca case in the first 2 years after diagnosis was $41,686 (based on 39,655 bca cases). Mean cost of care for stage iii and iv patients was at least twice that for stage i patients. The overall mean cost declined slightly to $40,426 for women who remained living (n = 36,402) during the entire 2-year time horizon.

TABLE III.

Costs for breast cancer cohort and living breast cancer cohort

| Variable | Disease stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Alla | i | ii | iii | iv | |

| Entire breast cancer cohort | |||||

| Cases (n) | 39,655 | 13,628 | 12,602 | 4,765 | 1,552 |

| Costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Mean | 41,686±37,403 | 29,938±26,750 | 46,893±35,488 | 65,369±42,674 | 66,627±56,715 |

| Median | 30,149 | 22,120 | 37,709 | 52,542 | 49,158 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 18,313–50,582 | 16,263–32,416 | 24,389–55,291 | 39,120–85,959 | 26,426–90,788 |

| Women still living during the 2-year time horizon | |||||

| Cases (n) | 36,402 | 13,386 | 12,024 | 4,210 | 791 |

| Costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Mean | 40,426±35,867 | 29,542±26,227 | 46,168±34,401 | 64,603±41,360 | 73,734±58,416 |

| Median | 29,233 | 22,003 | 37,229 | 51,439 | 55,138 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 18,126–48,490 | 16,205–31,890 | 24,172–54,117 | 39,052–85,378 | 30,004–106,554 |

The number of cases for all four stages does not add to the total number of cases for the cohort because the cases with an Unknown disease stage are not presented here.

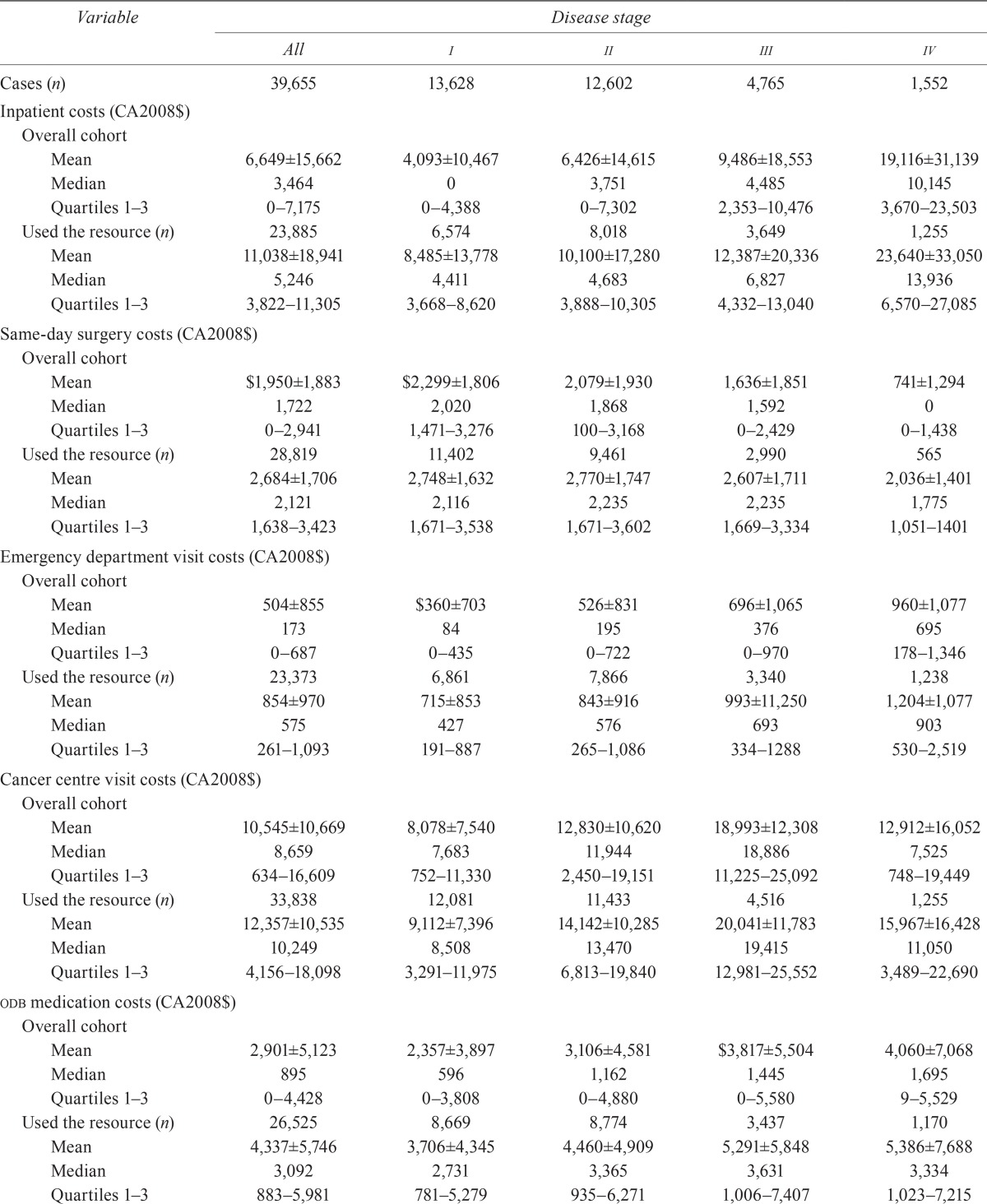

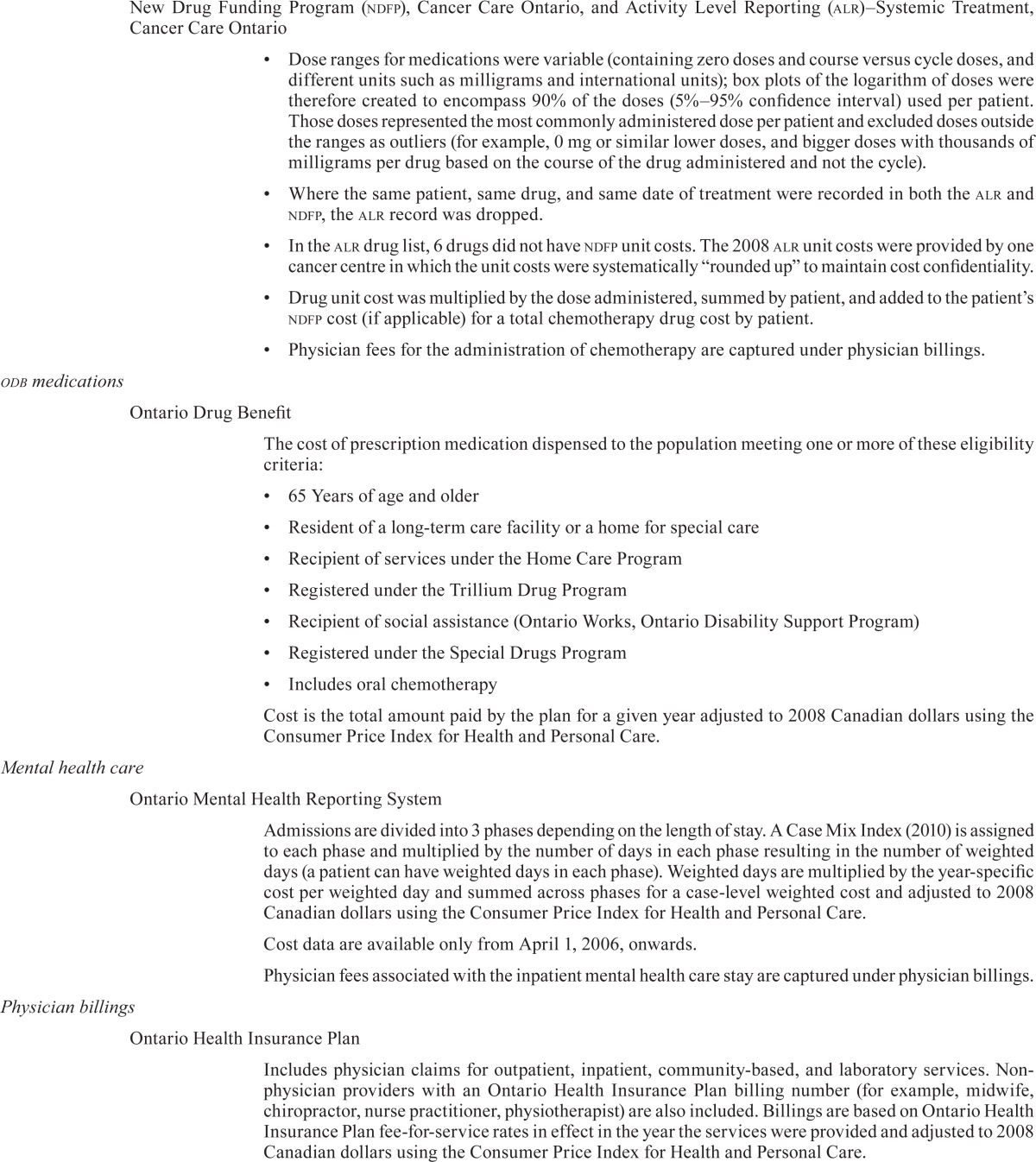

Table iv presents the mean and median costs for all bca patients and for those who used a given health care resource. Some notable cost trends included an increase in mean cost with advancing disease stage for resources such as hospitalization, ed visits, medications, homecare, and Ontario Health Insurance Plan (ohip) physician billings. The mean cost of same-day surgery declined with advancing stage. The mean costs of cancer clinic visits and radiation therapist time increased from stage i to stage iii, but decreased for stage iv disease.

TABLE IV.

Health care resource-specific costs (total cohort and those who used the resource)

| Variable | Disease stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| All | i | ii | iii | iv | |

| Cases (n) | 39,655 | 13,628 | 12,602 | 4,765 | 1,552 |

| Inpatient costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 6,649±15,662 | 4,093±10,467 | 6,426±14,615 | 9,486±18,553 | 19,116±31,139 |

| Median | 3,464 | 0 | 3,751 | 4,485 | 10,145 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 0–7,175 | 0–4,388 | 0–7,302 | 2,353–10,476 | 3,670–23,503 |

| Used the resource (n) | 23,885 | 6,574 | 8,018 | 3,649 | 1,255 |

| Mean | 11,038±18,941 | 8,485±13,778 | 10,100±17,280 | 12,387±20,336 | 23,640±33,050 |

| Median | 5,246 | 4,411 | 4,683 | 6,827 | 13,936 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 3,822–11,305 | 3,668–8,620 | 3,888–10,305 | 4,332–13,040 | 6,570–27,085 |

| Same-day surgery costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | $1,950±1,883 | $2,299±1,806 | 2,079±1,930 | 1,636±1,851 | 741±1,294 |

| Median | 1,722 | 2,020 | 1,868 | 1,592 | 0 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 0–2,941 | 1,471–3,276 | 100–3,168 | 0–2,429 | 0–1,438 |

| Used the resource (n) | 28,819 | 11,402 | 9,461 | 2,990 | 565 |

| Mean | 2,684±1,706 | 2,748±1,632 | 2,770±1,747 | 2,607±1,711 | 2,036±1,401 |

| Median | 2,121 | 2,116 | 2,235 | 2,235 | 1,775 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 1,638–3,423 | 1,671–3,538 | 1,671–3,602 | 1,669–3,334 | 1,051–1401 |

| Emergency department visit costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 504±855 | $360±703 | 526±831 | 696±1,065 | 960±1,077 |

| Median | 173 | 84 | 195 | 376 | 695 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 0–687 | 0–435 | 0–722 | 0–970 | 178–1,346 |

| Used the resource (n) | 23,373 | 6,861 | 7,866 | 3,340 | 1,238 |

| Mean | 854±970 | 715±853 | 843±916 | 993±11,250 | 1,204±1,077 |

| Median | 575 | 427 | 576 | 693 | 903 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 261–1,093 | 191–887 | 265–1,086 | 334–1288 | 530–2,519 |

| Cancer centre visit costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 10,545±10,669 | 8,078±7,540 | 12,830±10,620 | 18,993±12,308 | 12,912±16,052 |

| Median | 8,659 | 7,683 | 11,944 | 18,886 | 7,525 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 634–16,609 | 752–11,330 | 2,450–19,151 | 11,225–25,092 | 748–19,449 |

| Used the resource (n) | 33,838 | 12,081 | 11,433 | 4,516 | 1,255 |

| Mean | 12,357±10,535 | 9,112±7,396 | 14,142±10,285 | 20,041±11,783 | 15,967±16,428 |

| Median | 10,249 | 8,508 | 13,470 | 19,415 | 11,050 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 4,156–18,098 | 3,291–11,975 | 6,813–19,840 | 12,981–25,552 | 3,489–22,690 |

| odb medication costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 2,901±5,123 | 2,357±3,897 | 3,106±4,581 | $3,817±5,504 | 4,060±7,068 |

| Median | 895 | 596 | 1,162 | 1,445 | 1,695 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 0–4,428 | 0–3,808 | 0–4,880 | 0–5,580 | 9–5,529 |

| Used the resource (n) | 26,525 | 8,669 | 8,774 | 3,437 | 1,170 |

| Mean | 4,337±5,746 | 3,706±4,345 | 4,460±4,909 | 5,291±5,848 | 5,386±7,688 |

| Median | 3,092 | 2,731 | 3,365 | 3,631 | 3,334 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 883–5,981 | 781–5,279 | 935–6,271 | 1,006–7,407 | 1,023–7,215 |

| Costs of cancer medications and chemotherapies (CA2008$) | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 278±650 | 147±3,694 | 360±687 | 577±850 | 451±965 |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 61 | 248 | 0 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 0–232 | 0–0 | 0–296 | 27–412 | 0–339 |

| Used the resource (n) | 16,964 | 2,874 | 7,720 | 3,712 | 741 |

| Mean | 15,342±20,686 | 15,622±20,894 | 14,204±19,409 | 17,484±21,718 | 19,036±27,466 |

| Median | 6,434 | 5,874 | 6,498 | 7,193 | 6,208 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 2,875–11,094 | 1,204–28,643 | 3,300–8,947 | 4,116–25,478 | 1,040–24,104 |

| Complex continuing care costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 542±7,592 | 174±3,694 | 462±6,942 | 784±9,991 | 2,131±12,032 |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 |

| Used the resource (n) | 759 | 76 | 182 | 133 | 153 |

| Mean | 28,314±47,201 | 26,333±42,192 | 32,010±48,369 | 28,071±53,204 | 21,817±32,454 |

| Median | 11,974 | 14,337 | 14,560 | 11,908 | 10,730 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 5,162–30,637 | 6230–24248 | 5,329–41,838 | 4611–32,344 | 5,072–22,834 |

| Long-term care costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 1,071±7,650 | 474±5,202 | 938±7,334 | 977±7,192 | 1,005±6,828 |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 |

| Used the resource (n) | 1,177 | 163 | 307 | 139 | 498 |

| Mean | 36,068±26,642 | 39,659±26,702 | 38,520±27,613 | 33,503±26,230 | 36,034±25,912 |

| Median | 34,397 | 37,001 | 36,951 | 24,865 | 36,461 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 9,375–63,385 | 17,562–64,606 | 11,430–65,185 | 9,808–58,187 | 9,466–65,005 |

| Radiation therapist costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 420±409 | 392±323 | 461±414 | 743±474 | 245±387 |

| Median | 400 | 398 | 446 | 738 | 68 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 0–683 | 0–602 | 0–732 | 485–1,043 | 0–342 |

| Used the resource (n) | 25,793 | 9,751 | 8,601 | 4,057 | 815 |

| Mean | 646±333 | 548±245 | 675±326 | 873±388 | 466±246 |

| Median | 593 | 495 | 621 | 1,019 | 328 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 413–817 | 374–704 | 436–852 | 625–1,117 | 160–661 |

| Total ohip costs (CA2008$)a | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 7,266±4,975 | 6,486±4,179 | 7,786±3,951 | 9,404±6,136 | 9,359±8,591 |

| Median | 6,382 | 5,713 | 7,005 | 8,542 | 8,012 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 4,693–8,842 | 4,466–7,579 | 5,351–9,320 | 6,462–11,233 | 4,621–12,098 |

| Used the resource (n) | 39,601 | 13,627 | 12,598 | 4,763 | 1,550 |

| Mean | 7,276±4,971 | 6,487±4,178 | 7,788±3,949 | 9,408±6,135 | 9,371±8,590 |

| Median | 6,386 | 5,713 | 7,006 | 8,434 | 7,924 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 4,701–8,846 | 4,466–7,580 | 5,352–9,320 | 6,546–11,233 | 4,480–12,078 |

| Home care costs (CA2008$) | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 2,538±4,824 | 1,436±3,264 | 2,782±4,358 | 4,287±5,793 | 5,726±9,306 |

| Median | 1,237 | 691 | 1,583 | 2,516 | 2,273 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 0–2,753 | 0–1,555 | 794–3,212 | 1,339–5,015 | 584–6,484 |

| Used the resource (n) | 29,559 | 8,415 | 10,759 | 4,520 | 1,232 |

| Mean | 3,405±5,316 | 2,325±3,897 | 3,259±4,549 | 4,519±5,859 | 7,213±9,918 |

| Median | 1,771 | 1,294 | 1,902 | 2,690 | 3,579 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 1,035–3,675 | 822–2,397 | 1,146–3,674 | 1,489–5,255 | 1,497–8,948 |

| Other costs (CA2008$)b | |||||

| Overall cohort | |||||

| Mean | 738±7,762 | 522±7,032 | 799±8,109 | 921±9,424 | 1,285±7,197 |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 |

| Used the resource (n) | 4,778 | 988 | 1,473 | 801 | 246 |

| Mean | 6,128±21,613 | 7,194±25,191 | 6,833±22,839 | 5,478±22,448 | 8,107±16,453 |

| Median | 332 | 380 | 369 | 313 | 1,145 |

| Quartiles 1–3 | 222–1,498 | 222–2,918 | 222–1,637 | 222–993 | 382–5,350 |

Includes physician billings, family health network or family health organization capitation, and non-physician and diagnostic or laboratory (physician component) costs.

Includes dialysis, rehabilitation, mental health hospitalization, and the Assistive Devices Program.

odb = Ontario Drug Benefit; ohip = Ontario Health Insurance Program.

In terms of resource utilization by bca patients who used health care resources, 54 women had no physician visitsc. In terms of resource utilization, other results showed that 85.3% of patients had at least 1 cancer clinic visit, 74.5% received at least 1 publicly funded homecare service, 72.7% underwent same-day surgery, 64.0% had at least 1 visit with a radiation therapist, 60.2% had at least 1 hospitalization, 58.2% made at least 1 ed visit, and 42.8% received at least 1 chemotherapy treatment.

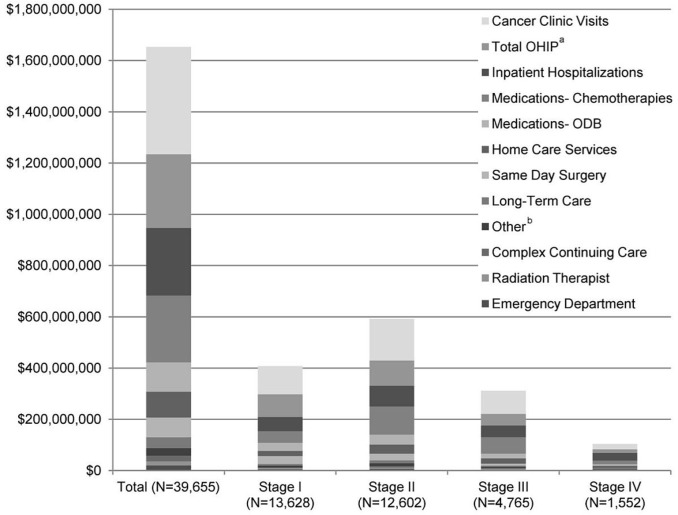

Figure 1 illustrates the dollar amounts of the individual health care resources used by the bca cancer cohort, overall and at each disease stage. Although the greatest number of patients were stage i at diagnosis, stage ii incurred the largest overall cost ($590,996,657) of all disease stages, chiefly as a result of cancer clinic visits (25.3%), followed by ohip physician billings (17.4%) and hospitalizations (15.9%).

FIGURE 1.

Cost of health care resources, total and by stage, for the breast cancer cohort (n = 39,655). a Includes physician billing, family health network or family health organization capitation, nonphysician, and diagnostic and laboratory (physician component) costs. b Includes dialysis, rehabilitation, mental health hospitalization, and the Assistive Devices Program. ohip = Ontario Health Insurance Plan; odb = Ontario Drug Benefit.

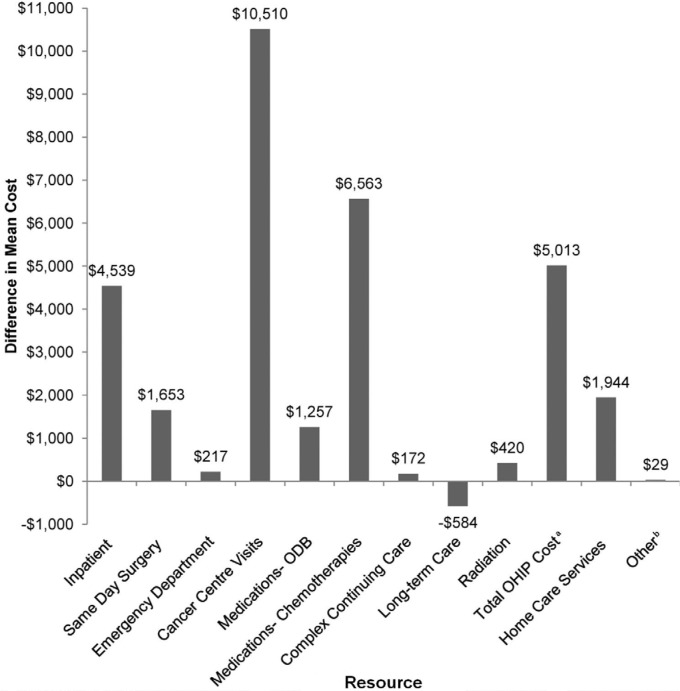

Figure 2 shows the differences in mean costs between the bca patient cohort and the control cohort, disaggregated by health care resource. The largest cost difference between patients and control subjects was that for cancer centre visits (+$10,510 for bca cases); chemotherapies (+$6,563) and physician billings (+$5,013) were second- and third-most costly. Concomitant drug costs (Ontario Drug Benefit Formulary) were $1,257 higher in the bca patients than in the control group. Long-term care was the sole health care resource whose costs were higher in the control group (−$584).

FIGURE 2.

Net mean cost of health care resources (breast cancer cases – controls). a Includes physician billing, family health network or family health organization capitation, nonphysician, and diagnostic and laboratory (physician component) costs. b Includes dialysis, rehabilitation, mental health hospitalization, and the Assistive Devices Program. odb = Ontario Drug Benefit; ohip = Ontario Health Insurance Plan.

4. DISCUSSION

This Canadian analysis is the first to examine stage-based costs for a population-based cohort of women with a diagnosis of bca in a publicly funded system. The results presented here represent one of the largest Canadian bca cohorts with disease staging, and almost half the women in our cohort were less than 65 years of age. Using a conservative but comprehensive costing approach, the overall mean cost of managing women for 2 years after a bca diagnosis was found to be $41,686. That cost translates into $1.7 billion for the first 2 years of care after diagnosis for the 39,655 bca patients in our study cohort. In terms of attributable costs, the bca patients used $31,732 more in public health system resources than did matched control subjects without any cancer.

The overall mean cost increased by disease stage because of higher resource utilization. Compared with women having stage i or ii bca, those with advanced bca had higher proportions of hospitalizations, cancer clinic visits, ed visits, and homecare. For example, the proportion of patients with at least 1 ed visit during our 2-year timeframe increased from 50% in stage i to almost 80% in stage iv. In contrast, almost 84% of stage i bca patients underwent same-day surgery, a proportion that declined to 36% for stage iv bca patients (likely because of the limited procedures available to patients with advanced disease). Different trends were observed for chemotherapies and radiation. In patients receiving chemotherapy, utilization increased with disease stage: It was highest for those diagnosed at stage iii (75%), declining to 48% at stage iv (again because of limited options for treating advanced disease). Because radiation therapist time was used as a surrogate for radiation therapy, 72%, 68%, and 85% utilization was found for stages i, ii, and iii respectively; utilization then dropped to 53% for stage iv, indicating that radiation is a key component of the treatment armamentarium for our bca patient cohort.

Recent Canadian work5,6 using population-based cohorts has provided overall costs for a number of cancers, including bca, but those analyses did not evaluate the costs of all health care resources by stage of disease or determine the attributable bca cost compared with matched control subjects.

Previous publications of bca costs3,4 used different methodologies for determining lifetime bca costs. Our work led to a substantially higher cost, based on fewer women, and representing only the first 2 years after diagnosis. We hypothesize that the discrepancies are a result of different data sources, inclusion or exclusion of certain health care resources, inflation, and the availability of more (and more expensive) medications to manage bca.

Lifetime costs for bca have previously been modelled in a Canadian setting4. Using the Statistics Canada Population Health Model (a microsimulation model), Will and colleagues4 estimated the average undiscounted lifetime cost per women by stage (1995 Canadian dollars), finding an estimated lifetime medical cost per woman that was substantially lower than our stage-based 2-year cost. The main differences are the result of approach (treatment utilization algorithms being modelled rather than patient-level data being obtained from the health care system), of information on resources and costs becoming outdated, and again, of more (and more expensive) medications becoming available to manage bca.

A review11 of bca treatment costs from other countries also reported lifetime costs that were lower than our 2-year costs, generally because only specific types of resources (treatment12,13, treatment-related adverse effects14, surgery15) were used. In one study from the United Kingdom, Remák and Brazil16 used regional administrative databases and physician questionnaires to reported a lifetime cost of £12,500 (in 2000 currency) for the management of stage iv breast cancer.

Our work is subject to a number of limitations. The data sources were Ontario databases collected for administrative purposes; they might therefore not contain all variables of interest with respect to the medical management of bca. Screening (for example, mammography, ultrasonography) was not considered in our analysis because only costs after diagnosis were examined. Stage information was missing or unknown for 17.9% of the bca cohort, and we therefore did not consider those patients in our stage-based costing. The collection of stage data is still improving at the provincial level. Information on hormone receptor and her2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) status was not available at a population level, and those data can influence the type of treatment offered and, consequently, the cost implications.

Costing using the alr database required several assumptions and probably resulted in an underestimation of the total systemic therapy costs ($260 million). For example, alr data largely represent the cancer centres in the province, and doses outside the 5%–95% range were excluded. Drugs in the alr that were administered non-intravenously were excluded from the analysis because of inconsistencies in how they were entered into the system (that is, some sites entered oral therapies into their computerized order entry systems; other sites did not). Drug wastage was not considered in our analysis because we applied costs only to the dose administered and not to the vials that would actually be used. Also, because not all facilities that administer systemic chemotherapy report through the alr database, we anticipate that the systemic chemotherapies administered in the province are underestimated.

We cannot estimate the use and cost of all oral medications (women under 65, living in community, not on social assistance), because private and out-of-pocket payments are not covered in the public insurer database. However, we did include all systemic medications and expensive medications for all women in the population and oral medications for women meeting provincial eligibility requirements.

The ohip physician billing category included physician billing, family health network or family health organization capitation services, nonphysician billing, and the physician component for diagnostic and laboratory tests. The cost of the technical component for diagnostic tests (for example, technician time) was not included in our analysis because hospitals are responsible for that component as part of their global budget; the professional component of diagnostic tests (for example, physician) was captured in the total ohip costs. The foregoing exclusion also applies to laboratory tests conducted at hospital institutions.

Another limitation is that radiation costing consisted only of radiation therapist time; it did not consider equipment, physicist time, and administrative costs. Future studies will consider other radiation-related resources for costing. Our study evaluated only direct medical costs and not indirect, lost productivity, or out-of-pocket costs that are not available in the administrative data. Other work has shown that indirect costs are substantial, accounting for well over 50% of the total cost of cancer17–19. Lastly, it is evident that analyzing data within 2 years after the initial diagnosis might not accurately identify all costs and utilization of breast cancer management, because, for many patients, treatment and survival can extend beyond those 2 years.

Despite the described limitations, we have provided a comprehensive cost study, by stage of disease, based on administrative data for an entire population of women with a diagnosis of bca in the first 2 years after a diagnosis. Our work provides critical utilization and cost data to governments, industry, private payers, and academia. In particular, our data will be useful for decision-makers in the health care system examining the burden of illness at different stages; health economists generating health technology assessments for first-, second-, and third-line interventions; modellers building decision analytic models and microsimulations for health economics; and policymakers investing in publicly funded resources across various disease severities.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our study is the first to examine the impact of disease stage on the initial publically funded provincial health system resources and costs for a bca cohort in Canada. We found that, in the 2 years after a bca diagnosis, significant direct health care costs ($41,686 per patient) were spent by the publicly funded health system, of which $31,732 per patient are attributable to bca-related care (cost differential compared with matched controls). The attributable cost is based on significant resource utilization associated with cancer clinics, hospitalizations, same-day surgery, and ed visits for all women with a bca diagnosis. In our analysis, women with stage ii bca account for one third of the overall bca cost. Future analyses will examine various timeframes or phases throughout bca management and disaggregate the stage-based resources even further.

The methods used here will help with further costing work for bca and other disease sites. These data are critical to understanding stage-based resources and funding in bca. When designing public policies for the treatment of bca, it is important to consider the type and extent of publicly funded health care services utilized. Such data will inform the future planning of health care for women with bca.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The investigators thank Nelson Chong (programmer at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences) and Rene Robitaille (programmer at Cancer Care Ontario) for their help in untangling and linking datasets. Thanks also go to Angie Giotis for her assistance in costing medication regimens. We are grateful to Thi Ho and Katrina Chan (grant coordinators) for their administrative insight. We also acknowledge Shazia Hassan, Peggy Kee, and Grace Bannon for costing and administrative assistance.

Footnotes

We used the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups System (http://acg.jhsph.org/) to classify patients into health resource utilization bands. The system uses a multistep algorithm to assign International Classification of Diseases codes to 32 aggregated diagnosis groups, which are then combined with age, sex, duration and severity of disease, and number of diseases to categorize patients into 1 of 102 clinically similar disease groups (“adjusted clinical groups”) that describe patients in terms of the totality of their previous disease history. The system then groups patients who might not be clinically similar, but who are expected to place a similar burden on the health care system, into quintiles of predicted health resource utilization. The resource utilization bands are 0 (none), 1 (healthy users), 2 (low), 3 (moderate), 4 (high), and 5 (highest)8.

The Adjusted Clinical Groups software uses a methodology designed to measure the intensity of resource use over a defined period of time. For resource utilization band scoring, the service utilization look-back period was 2 years for patients and control subjects alike.

We suspect that this observation reflects a miscoding issue, because to reach a diagnosis of bca, a physician should have been involved, and at least 1 physician visit should therefore have been found.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

All authors declared no perceived conflict of interest regarding the development of the present document. In the interest of being completely transparent: NM declared educational programs, unrestricted funding, and consultancies through the Health Outcomes and PharmacoEconomics (hope) Research Centre, a group that consults to the pharmaceutical industry. SJS declared consultancies through the hope Research Centre, a group that consults to the pharmaceutical industry. WKE declared consultancy contracts with Roche and Boehringer–Ingelheim and work on advisory boards for Bristol–Myers Squibb and Astellas.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.The Conference Board of Canada (cboc) Home > How Canada Performs > International Rankings > Health > Mortality Due to Cancer [Web page] Ottawa, ON: CBOC; 2012. [Available at: http://www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/details/health/mortality-cancer.aspx; cited February 26, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Cancer Society. Home > Cancer information > Cancer type > Breast > Statistics. Breast Cancer Statistics [Web page] Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2014. [Available at: http://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/breast/statistics/?region=mb; cited June 18, 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patra J, Popova S, Rehm J, Bondy S, Flint R, Giesbrecht N. Economic Cost of Chronic Disease in Canada 1995–2003. Toronto, ON: Ontario Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance; 2007. [Available online at: http://ocdpa.ca/sites/default/files/publications/OCDPA_EconomicCosts.pdf; cited January 15, 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Will BP, Bertheolot JM, Le Petit C, Tomiak EM, Verma S, Evans WK. Estimates of the lifetime costs of breast cancer treatment in Canada. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:724–35. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Oliveria C, Bremner KE, Pataky R, et al. Understanding the costs of cancer before and after diagnosis for the 21 most common cancers in Ontario: a population-based descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2013;1:E1–8. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20120013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Oliveria C, Bremner KE, Pataky R, et al. Trends in use and cost of initial cancer treatment in Ontario: a population-based descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2013;1:E151–8. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20130041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittmann N, Liu N, Porter JM, et al. End-of-life home care utilization and costs in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. J Community Support Oncol. 2014;12:92–8. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittmann N, Liu N, Porter J, et al. Utilization and costs of home care for patients with colorectal cancer: a population-based study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2:E11–17. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20130026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mittmann N, Isogai PK, Saskin R, et al. Population-based home care services in breast cancer: utilization and costs. Curr Oncol. 2012;19:e383–91. doi: 10.3747/co.19.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancer Care Ontario (cco) Stage Data Resolution Interim Solution for User Access. Version 1.0. Toronto, ON: CCO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell JD, Ramsey SD. The costs of treating breast cancer in the US—a synthesis of published evidence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:199–209. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200927030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breast cancer stage cost analysis in a managed care population. Based on a presentation by Kenneth L. McDonough, md, ms. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5(suppl):S377–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legorreta AP, Brooks RG, Leibowitz AN, Solin LJ. Cost of breast cancer treatment: a 4-year longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2197–201. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440180055007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassett MJ, O’Malley AJ, Pakes JR, Newhouse JP, Earle CC. Frequency and cost of chemotherapy-related serious adverse effects in a population sample of women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1108–17. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamerato L, Havstad S, Gandhi S, Jones D, Nathanson D. Economic burden associated with breast cancer recurrence: findings from a retrospective analysis of health system data. Cancer. 2006;106:1875–82. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Remák E, Brazil L. Cost of managing women presenting with stage iv breast cancer in United Kingdom. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:77–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lidgren M, Wilking N, Jõnsson B, Rehnberg C. Resource use and costs associated with different states of breast cancer. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2007;23:223–31. doi: 10.1017/S0266462307070328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broekx S, Den Hond E, Torfs R, et al. The costs of breast cancer prior to and following diagnosis. Eur J Health Econ. 2011;12:311–17. doi: 10.1007/s10198-010-0237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon L, Scuffham P, Hayes S, Newman B. Exploring the economic impact of breast cancers during the 18 months following diagnosis. Pyschooncology. 2007;16:1130–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]