Abstract

The total synthesis of cytotoxic polyketides myceliothermophins E (1), C (2) and D (3) through a cascade-based cyclization to form the trans-fused decalin system is described. The convergent synthesis delivered all three natural products through late-stage divergence and facilitated unambiguous C21 structural assignments for 2 and 3 through X-ray crystallographic analysis which revealed an interesting dimeric structure between its enantiomeric forms.

Keywords: cascade reaction, decalin, natural products, polyketides, total synthesis

Natural products containing a tetramic acid structural motif are of interest because of their often unusual and challenging structures and wide range of biological activities.[1] Isolated from Myceliophthora thermophila, myceliothermophins E (1), C (2) and D (3) (Figure 1) exhibit potent cytotoxic properties against a number of human cancer cell lines, namely hepatoblastoma (HepG2, IC50 = 0.28 μg mL−1 for 1; 0.62 μg mL−1 for 2), hepatocellular carcinoma (Hep3B, IC50 = 0.41 μg mL−1 for 1; 0.51 μg mL−1 for 2), lung carcinoma (A-549, IC50 = 0.26 μg mL−1 for 1; 1.05 μg mL−1 for 2), and breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7, IC50 = 0.27 μg mL−1 for 1; 0.52 μg mL−1 for 2).[2] Total syntheses of these compounds and their siblings myceliothermophins A[2] and B[2] through a strategy involving an intramolecular Diels–Alder process of a polyunsaturated aldehyde for the casting of their trans-fused decalin system have been reported.[3a] Given the difficulties encountered with the preparation and Diels–Alder reactions of polyunsaturated aldehydes as substrates,[4] we sought an alternative strategy for the construction of the decalin system embedded in these natural products. In this communication, we report an efficient total synthesis of 1, 2 and 3 that features an unusual cascade sequence of reactions[5] for the stereoselective construction of their rare trans-fused decalin system, and confirm unambiguously their structures through X-ray crystallographic analysis of 2.

Figure 1.

Structures of myceliothermophins E (1), C (2), D (3) and retrosynthetic analysis.

The strategy for the total synthesis of myceliothermophins E (1), C (2) and D (3) was based on the retrosynthetic analysis depicted in Figure 1. Thus, the requisite decalin aldehyde system 4 was to serve as a precursor to 1, 2 and 3 through appropriate manipulation, attachment of the pyrrolidinone structural motif (5), and further functional group adjustments. Aldehyde 4 was traced back to the simpler trans-fused decalin system 6 featuring two methyl groups, one of which being angular. The uniquely challenging decalin system 6 was expected to arise from a sequential rearrangement of epoxide 9 to aldehyde 8, and enolization of the latter followed by Robinson-type annulation (via 7) as depicted in Figure 1. The implementation of this cascade strategy for the synthesis of key building block 6 required extensive experimentation to define appropriate conditions as discussed below.

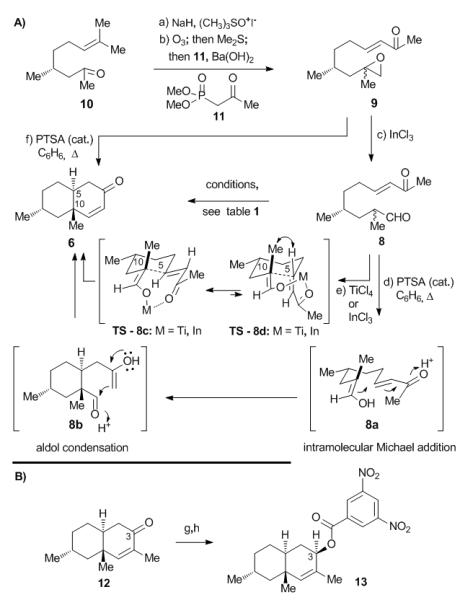

Decalin key building block 6 was prepared from (±)-citronellal derivative 10[6] as shown in Scheme 1A (for cost effectiveness, racemic material was employed, although both enantiomers are also commercially available). Thus, treatment of 10 under Corey–Chaykovsky conditions[7] furnished the corresponding epoxyolefin (96% yield, ca 1:1 dr) which was subjected to ozonolysis/Me2S reduction to afford the corresponding epoxyaldehyde (ca 1:1 dr). The latter was then condensed with ketophosphonate 11 under Ba(OH)2 conditions[8] to afford α,β-unsaturated ketoepoxide 9 as a mixture of diastereomers (ca 1:1 dr) in 81% yield for the two steps. Exposure of this intermediate to catalytic amounts of InCl3[9] resulted in the formation of ketoaldehyde 8 in 85% yield (ca 1:1 dr). At this point, an extensive survey of conditions was undertaken in order to develop the devised cascade to convert these substrates (9 or 8) to the desired decalin system 6 (see Table 1). Surprisingly, none of the usual basic conditions employed (e.g. NaOMe/MeOH, proline/DMSO, Zr(OiPr)4/CH4Cl2 [10] produced any of the desired product, leading instead to decomposition or no reaction (Table 1; entries 1, 2 and 3). Interestingly, however, the intended cascade bis-cyclization (8→8a→8b→6, Scheme 1A) was observed under certain protic (e.g. HCl) or Lewis acid conditions with good to excellent diastereoselectivities, albeit in low yields (Table 1; entries 4, 5 and 6). The better selectivities observed with TiCl4 and InCl3 (ca 10:1 and 4.5:1 dr, respectively) in favor of the shown diastereomer 6 versus its diastereomer (5-epi-6 or 10-epi-6, not shown)[11] can be attributed to the preferred metal-templated cyclic transition state TS-8c (in which the HOMO of the enolate and the LUMO of the enone are aligned for favorable overlap) as compared to the transition state TS-8d which suffers from unfavorable steric interaction between H5 and the C10 methyl group (see Scheme 1A). Finally, the cascade bis-cyclization of ketoaldehyde 8 to decalin 6 was found to proceed in excellent yield (92%) and good diastereoselectivity (6: 5-epi-6 or 10-epi-6 ca 3:1) in the presence of catalytic amounts of PTSA in refluxing benzene (Table 1; entry 7). The direct conversion of epoxide 9 to decalin 6 was also achieved under the same conditions, albeit in only 65% yield (ca 3:1 dr). The latter cascade reaction presumably proceeds via aldehyde 8, formed upon initial epoxide rearrangement, through the same pathway (8→8a→8b→6, Scheme 1A). The relative stereochemical configuration of the major decalin diastereomer 6 was established unambiguously through X-ray crystallographic analysis (see ORTEP, Figure 2A)[12] of its crystalline 3,5-dinitrobenzoate derivative 13 [Scheme 1B, m.p. 92–94 °C, EtOAc:hexanes (1:1)] and NMR spectroscopic comparison. Compound 13 was prepared from enone 12 [(ca 3:1 dr), obtained from the ethyl counterpart of 9 through the same cascade reaction] by NaBH4 reduction (≥ 20:1 dr at C3, 61%) and benzoylation of the resulting allylic alcohol with 3,5-C6H3(NO2)2COCl (95%) as shown in Scheme 1B.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of decalin system 6 and 3,5–dinitrobenzoate 13. A) Reagents and conditions: a) NaH (1.3 equiv), (CH3)3SO+ l− (1.3 equiv), DMSO, 0 °C, 3 h, 96% (ca 1:1 dr); b) O3; then Me2S (3.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 1 h; then Ba(OH)2 (1.1 equiv), 11 (1.1 equiv), THF:H2O (10:1), 0 °C, 2 h, 84% (ca 1:1 dr); c) InCl3 (0.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 0.5 h, 85% (ca 1:1 dr); d) PTSA (0.1 equiv), benzene, reflux, 3 h, 92% (ca 3:1 dr); e) see Table 1, entry 5: TiCl4, MS 4Å, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 72 h, 23% (ca 10:1 dr); entry 6: InCl2, C6H6, 45 °C, 5 h, 30% (ca 4.5:1); f) PTSA (0.1 equiv), benzene, reflux, 3 h, 65% (ca 3:1 dr); B) Reagents and conditions: g) NaBH4 (1.2 equiv), MeOH, 0 °C, 1 h, 61% (≥ 20:1 dr); h) 3,5- C6H3(NO2)2COCl (1.2 equiv), DMAP (2.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 2 h, 95% (≥ 20:1 dr); PTSA = p-toluenesulfonic acid.

Table 1.

Optimization of cyclization of ketoaldehyde 8 to decalin system 6[a]

| Entry | Conditions | Time (h) | Temp (°C) | Yield (%)[b] | dr[c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NaOMe, MeOH | 2 | 25 | decomp | -- |

| 2 | proline, DMSO | 24 | 25 | n.r. | -- |

| 3 | Zr(Oi/Pr)4, CH2Cl2 | 24 | 25 | n.r. | -- |

| 4 | 1.0 M HCl/Et2O, THF | 72 | 25 | 35 | 3:1 |

| 5 | TiCl4, MS 4Å, CH2Cl2 | 72 | 25 | 23 | 10:1 |

| 6 | InCl3, C6H6 | 5 | 45 | 30 | 4.5:1 |

| 7 | PTSA1, C6H6 | 5 | reflux | 92 | 3:1 |

Reactions were performed on 1.0 mmol scale of ketoaldehyde 8;

combined isolated yield;

diastereomeric ratio (C5 or C10 epimer; 6: major isomer) was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of crude product 6; n.r. = no reaction, PTSA = p-toluenesulfonic acid.

Figure 2.

X-Ray derived ORTEP representation of A) 3,5-dinitrobenzoate (±)-13 and B) synthetic myceliothermophin C [(±)-2]. Thermal ellipsoids at 30% probability. gray = C, red = O, blue = N, green = H for both ORTEPS.

Having secured the coveted enone decalin system 6 in decagram quantities from the readily available citronellal derivative 10, we proceeded to functionalize it (initially as a mixture until chromatographic separation became convenient, see below) to the next required key intermediate, aldehyde 4, as shown in Scheme 2. Thus, deprotonation of 6 (ca 3:1 dr) with LDA at −78 °C, followed by quenching the resulting enolate with 1H-benzothiazole-1-methanol[13] (14) furnished the expected hydroxymethyl product (15, ca 3:1 dr) which was immediately (due to its relative instability) protected as a TBS ether (TBSCl, DMAP cat, imid.) to afford compound 16 (ca 3:1 dr) in 81% overall yield for the two steps. The next task, that of installing the required side chain at C3 of our growing intermediate, proved rather intransigent with several direct tactics such as vinyl or acetylene attachments failing to produce the desired products. Other methods involving palladium π-allyl complexes[14] as intermediates derived from the corresponding allylic alcohol (obtained from enone 16) also failed to functionalize the C3 position as desired. This challenge was finally overcome through an indirect pathway involving 1,3-transposition of the enone moiety, followed by 1,4–addition to the newly generated enone as shown in Scheme 2. Thus, NaBH4 reduction of 16 afforded allylic alcohol 17 stereoselectively (ca 3:1 dr at C5 or C10; ≥10:1 dr at C3). At this stage, column chromatography allowed separation of the major diastereomer leading to pure allylic alcohol 17 (65% yield). mCPBA epoxidation of this compound led to a mixture of diastereomeric hydroxyepoxide 18 (ca 2:1 dr, inconsequential), which was mesylated to give 19 in 97% yield (ca 2:1 dr, inconsequential). Exposure of this mixture to Li-naphthalide[15] at −30 °C induced the expected radical-based rearrangement, generating, upon DMP[16] oxidation of the resulting mixture of allylic alcohols, enone 20 in 79% overall yield for the two steps. Upon extensive experimentation, it was found that slow addition of allyltrimethylsilane to enone 20 in CH2Cl2 in the presence of TiCl4 (Hosomi–Sakurai reaction)[17] led, exclusively, to the expected ketoolefin 21 possessing the desired α-configuration at C3 in 98% yield as confirmed by NOESY correlation between H3 and H4 of subsequent intermediate 25a. It should be noted that both the slow addition and low temperature are crucial in securing the high stereoselectivity and yield in this reaction. Another notable observation at this step was the fact that the corresponding vinyl cuprate reagent (derived from 2-cis-2-butenyllithium and CuCN) reacted with enone 20 to afford the opposite C3 epimer (C3-epi-21, not shown). These contrasting results may be due to the bulkiness of the TBS group within the substrate (i.e. 20). The precise mechanistic rationale for this interesting observation is still under investigation. Generation of the enolate from 21 (KHMDS, THF, −78 °C) followed by quenching with MeI furnished the corresponding methylated product (22) in 87% yield (≥ 20:1 dr; C2 configuration: inconsequential; not assigned). Ozonolysis/reduction of the olefinic moiety in 22 (O3; Me2S) followed by treatment of the resulting aldehyde with nonafluorobutanesulfonyl fluoride (NfF) and phosphazene base P1-tbutyl-tris(tetramethylene) (P1-base) furnished smoothly terminal acetylene 23 in 82% yield.[18] Reduction of the carbonyl group within the latter compound with DIBAL followed by dehydration (POCl3, py) then led to the corresponding acetylenic olefin, which was subjected to sequential zirconium-promoted carboalumination/iodination[19] (81% yield) and Pd-catalyzed Negishi coupling[20] with Me2Zn (94% yield) to give intermediate 25 via vinyl iodide 24. Desilylation of the latter (TBAF, 91% yield) followed by DMP oxidation of the resulting alcohol (25a) led to the coveted aldehyde 4 (95% yield).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the aldehyde 4. Reagents and conditions: a) 6 (ca 3:1 dr), LDA (3.0 equiv); then 14 (2.0 equiv), THF, −78 °C, 0.5 h; b) TBSCl (1.2 equiv), DMAP (0.1 equiv), imidazole (2.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 2 h, 81% for the two steps (ca 3:1 dr); c) NaBH4 (1.0 equiv), MeOH, −10 °C, 1 h; then flash column chromatography, 65% for pure alcohol 17; d) mCPBA (1.5 equiv), NaHCO3 (2.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 10 h, 92% (ca 2:1 dr); e) MsCl (1.5 equiv), Et3N (2.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C,1 h, 97% (ca 2:1 dr); f) Lithium naphthalide (2.0 equiv), THF, −30 °C, 3 h, 83% (ca 2:1 dr); g) DMP (1.1 equiv), NaHCO3 (2.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 1 h, 95%; h) allyltrimethylsilane (1.1 equiv), TiCl4 (1.2 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 2 h, 98%; i) KHMDS (2.0 equiv), MeI (2.0 equiv), THF, −78 °C, 4 h, 87% (≥ 20:1 dr); j) O3; then Me2S, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 1 h; then NfF (1.2 equiv), P1-base (3.0 equiv), DMF, 0 °C, 3 h, 82%; k) DIBAL (1.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 0.5 h, 98%; then POCl3 (5.0 equiv), pyridine, MeCN, 70 °C, 12 h, 81%; l) ZrCp2Cl2 (2.0 equiv), Me3Al (5.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, −20→25 °C, 24 h; then l2 (1.1 equiv), 25 °C, 24 h, 81%; m) Me2Zn (2.0 equiv), (Ph3P)2PdCl2 (5 mol%), THF, 0 °C, 3 h, 94%; n) TBAF (1.1 equiv), THF, 70 °C, 5 h, 91%; o) DMP (1.0 equiv), NaHCO3 (2.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 0.5 h, 95%. NfF = nonafluorobutanesulfonyl fluoride, P1-base = phosphazene base P1-tBu-tris(tetramethylene), LDA = lithium diisopropylamide, DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine, DMP = Dess–Martin periodinane.

The construction of the other requisite fragment, building block 5,[21] was achieved in two steps from succinimide (26) as shown in Scheme 3. Thus, treatment of 26 with isopropyl Grignard reagent 27 in THF at ambient temperature, followed by quenching with MeOH containing 10% conc. H2SO4 at 0°C, furnished lactam 28 in 62% yield.[22] It should be noted that H2SO4 was essential for the success of this reaction, for without it only open-chain product ketoamide 29 was obtained upon MeOH quenching. Furthermore, exposure of the latter compound to the same MeOH:H2SO4 solution failed to produce appreciable amounts of the desired cyclic product (i.e. 28), as did other acidic conditions (e.g. PTSA, PPTS, HCl aq).[3a] Free pyrrolidinone 28 was found to be rather labile, slowly hydrolyzing in air at ambient temperature to open-chain compound 29. It was, therefore, immediately protected as its Teoc derivative 5 (nBuLi, TeocONP, 82% yield) ready for coupling with aldehyde 4.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of pyrrolidinone building block 5. Reagents and conditions: a) 27 (3.0 equiv), THF, 25 °C, 24 h; then MeOH:H2SO4 (10:1), 62%; b) nBuLi (1.2 equiv), TeocONP (1.2 equiv), HMPA (1.0 equiv), THF, −78 °C, 10 h, 82%. TeocONP = 4-nitrophenyl 2-(trimethylsilyl)ethyl carbonate, HMPA = hexamethylphosphoramide.

Scheme 4 depicts the coupling of fragments 4 and 5 and the divergent elaboration of the coupling product to the targeted myceliothermophins C (2) and D (3) and thence 1. Thus, treatment of 5 with LDA (THF, −78°C) followed by addition of 4 to the resulting anion at −78°C furnished alcohol 30 in 85% yield (mixture of four diastereomers). Oxidation[23] of this mixture with DMP afforded diastereomeric ketones 31a and 31b (90% combined yield, ca 1:1 dr), which were chromatographically separated and subjected to the same three-step sequence required for their elaboration to the targeted natural products 2 and 3 [(i) phenyl selenylation (NaH, PhSeCl); (ii) oxidation/syn elimination (NaIO4, 78% yield for the two steps);[24] and (iii) removal of the Teoc group (TBAF:AcOH, 92% yield)]. Synthetic myceliothermophin C (2) (racemic) crystallized from an EtOAc solution upon slow evaporation to provide colorless crystals [m.p. 167 °C (decomp) (EtOAc)] suitable for X-ray crystallographic analysis,[12] a fortunate occurance for it gave us the opportunity to confirm unambiguously its original NMR-based structural assignment and that of its sibling, myceliothermophin D (3). As shown in Figure 2, X-ray crystallographic analysis of (±)-2 not only proved the original assignments for 2 and 3 by Wu et. al.,[2] but interestingly also revealed a dimeric form for 2 in the solid state involving the two enantiomers of the molecule within the crystal lattice (see ORTEP representation, Figure 2). Apparently the two enantiomeric molecules of myceliothermophin C (2) are held together by hydrogen bonding involving their pyrrolidinone moieties. Myceliothermophin E (1) could be generated from either 2 or 3 by treatment with aq HF in 81% yield as shown in Scheme 4.

Scheme 4.

Completion of the total synthesis of myceliothermophins E (1), C (2) and D (3). Reagents and conditions: a) LDA (1.0 equiv); then 4, THF, −78 °C, 0.5 h, 85%; b) DMP (5.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 6 h, 90% combined for 31a and 31b (ca 1:1 dr); c) NaH (1.1 equiv), THF, 25 °C, 0.5 h; then PhSeCl (1.0 equiv), −78 °C, 0.5 h; d) NaIO4 (2.0 equiv), MeCN, 25 °C, 2 h, 78% for the two steps; e) TBAF:AcOH (1:1) (2.0 equiv), THF, 0 → 25 °C, 5 h, 92%; (f) 47% aq. HF, MeCN, 0 → 25 °C, 2 h, 81%; DMP = Dess–Martin periodinane.

Involving a rare cascade sequence[5] to construct the trans-fused decalin system of the myceliothermophins, the described chemistry (which can also be applied to an enantioselective process) renders myceliothermophins E (1), C (2) and D (3) readily available for biological investigations. The developed cascade bis-cyclization for the construction of the trans-fused decalin system provides a practical alternative to the cumbersome Diels–Alder approach requiring difficult to access polyunsaturated aldehydes as substrates. The developed synthetic technologies may be applied to the construction of related natural products and designed analogs in racemic or enantiomeric forms for further structure activity relationship studies[25].

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201xxxxxx.

[**]Financial support was provided by The Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), the National Institutes of Health, USA (grant AI0055475), the National Science Foundation, and Rice University. Fellowships to M. Lu (Bristol-Myers Squibb) and H. A. I. (Marie-Curie International Outgoing Fellowship, European Commission) are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- [1].a) Royles BJL. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:1981–2001. [Google Scholar]; b) Nay B, Riache N, Evanno L. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:1044–1062. doi: 10.1039/b903905h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li XW, Ear A, Nay B. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013;30:765–782. doi: 10.1039/c3np70016j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Hoye TR, Dvornikovs V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2550–2551. doi: 10.1021/ja0581999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Nicolaou KC, Sarlah D, Wu TR, Zhan WQ. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:7002–7006. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:6870–6874. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Nicolaou KC, Sun Y-P, Sarlah D, Zhan WQ, Wu TR. Org. Lett. 2011;13:5708–5710. doi: 10.1021/ol202239u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Deng J, Zhu B, Lu Z, Yu H, Li A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:920–923. doi: 10.1021/ja211444m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Uchida K, Ogawa T, Yasuda Y, Mimura H, Fujimoto T, Fukuyama T, Wakimoto T, Asakawa T, Hamashima Y, Kan T. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:13022–13025. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:12850–12853. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Yin J, Kong L, Wang C, Shi Y, Cai S, Gao S. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:13040–13046. doi: 10.1002/chem.201302163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yang YL, Lu CP, Chen MY, Chen KY, Wu YC, Wu SH. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:6985–6991. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shionozaki N, Yamaguchi T, Kitano H, Tomizawa M, Makino K, Uchiro H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:5167–5170. (Note: No detailed experimental procedures or physical data of intermediates were provided in this publication). For natural products containing similar trans-fused decalin systems, see: Singh SB, Goetz MA, Jones ET, Bills GF, Giacobbe RA, Herranz L, Miles SS, Williams DL. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:7040–7042. West RR, Van Ness J, Varming A-M, Rassing B, Biggs S, Gasper S, Mckernan PA, Piggot J. J. Antibiot. 1996;49:967–973. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.967. Suzuki S, Hosoe T, Nozawa K, Kawai K, Yaguchi T, Udagawa S. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:768–772. doi: 10.1021/np990371x. Pornpakakul S, Roengsumran S, Deechangvipart S, Petsom A, Muangsin N, Ngamrojnavanich N, Sriubolmas N, Chaichit N, Ohta T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:651–655. Kontnik R, Clardy J. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4149–4151. doi: 10.1021/ol801726k.

- [4].a) Yakelis NA, Roush WR. Org. Lett. 2001;3:957–960. doi: 10.1021/ol015667k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sizova EP. The University of Minnesota, MN. 2009. Ph.D. Thesis. [Google Scholar]; c) Ramanathan M, Tan C-J, Chang W-J, Tsai H-HG, Hou D-R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:3846–3854. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40480c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Hoather HA. University of Manchester, UK. 2013. PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Watanabe H, Onoda T, Kitahara T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:2545–2548. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Snider BB, Karass M, Price RT, Rodini DJ. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:4538–4545. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Corey EJ, Chaykovsky M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:1353–1364. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wadsworth WS, Emmons WD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961;83:1733–1738. For the use of Ba(OH)2 in HWE reaction: Paterson I, Yeung K-S, Smaill JB. Synlett. 1993:774–776. Nicolaou KC, Jiang XF, Scott PJL, Corbu A, Yamashiro S, Bacconi A, Fowler VM. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:1171–1176. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006780. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:1139–1144. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006780.

- [9].Ranu BC, Jana U. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:8212–8216. For a recent application in total synthesis, see: Williams DR, Shah AA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:8829–8836. doi: 10.1021/ja5043462.

- [10].For base-catalyzed annulation reactions, see: Stork G, Shiner CS, Winkler JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:310–312. For an example of a proline catalyzed intramolecular Robinson annulation, see: Li P, Payette JN, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9534–9535. doi: 10.1021/ja073547n.

- [11].NMR spectrometric analysis does not distinguish between 5-epi- or 10-epi-6 unambiguously.

- [12].CCDC 1010933 and 1010994 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for compounds 2 and 13, respectively for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- [13].For applications of 14 in alkylation reactions, see: Katritzky AR, Yannakopoulou K, Lue P, Rasala D, Urogdi L. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1989:225–233. Deguest G, Bischoff L, Fruit C, Marsais F. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1165–1167. doi: 10.1021/ol070145b.

- [14].Trost BM, Van Vranken VL. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:395–422. doi: 10.1021/cr9409804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wu Y-K, Liu H-J, Zhu J-L. Synlett. 2008;3:621–623. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dess DB, Martin JB. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:4155–4156. [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Blumenkopf TA, Heathcock CH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:2354–2358. [Google Scholar]; b) Hosomi A. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988;21:200–206. [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Lyapkalo IM, Vogel MAK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:4019–4023. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lyapkalo IM, Vogel MAK, Boltukhina EV. Synlett. 2009;4:558–561. [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Negishi E. Pure Appl. Chem. 1981;53:2333–2356. and references therein. [Google Scholar]; b) Wipf P, Lim S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1993;32:1068–1071. [Google Scholar]; c) Yamakoshi S, Hayashi N, Suzuki T, Nakada M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:5372–5375. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Negishi E, King AO, Okukado N. J. Org. Chem. 1977;42:1821–1823. For reviews, see: Roush WR. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 3. Pergamon; Oxford: 1991. pp. 435–480. and references therein; Knochel P, Singer RD. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:2117–2188.

- [21].For a 6-step synthesis of pyrrolidinone 4 from isovaleraldehyde, see ref [3a].

- [22].For an example of a preparation of a similar methoxy aminal, see: Kende AS, Martin Hernando JI, Milbank JBJ. Tetrahedron. 2012;58:61–74.

- [23].Gregg C, Perkins MV. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:6547–6553. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25501d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sharpless KB, Lauer RF, Teranishi AY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:6137–6139. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Some of the early stages of this work were carried out at The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037 (USA).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.