The authors assessed the association between aggressiveness of end-of-life (EOL) care and differences in socioeconomic status (SES) among working-age terminal cancer patients from Taiwan between 2009 and 2011. These patients received aggressive EOL care, and care was even more aggressive in those with low SES. Public health strategies should continue to focus on low-SES patients to provide them with better EOL cancer care.

Keywords: Cancer, End-of-life care, Socioeconomic status, Working age, Young adults

Abstract

Background.

The relationship between low socioeconomic status (SES) and aggressiveness of end-of-life (EOL) care in cancer patients of working age (older than 18 years and younger than 65 years) is not clear. We assessed the association between aggressiveness of EOL care and differences in SES among working-age terminal cancer patients from Taiwan between 2009 and 2011.

Methods.

A total of 32,800 cancer deaths were identified from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database. The indicators of aggressive EOL care (chemotherapy, more than one emergency room [ER] visit or hospital admission, more than 14 days of hospitalization, intensive care unit [ICU] admission, and death in an acute care hospital) in the last month of life were examined. The associations between SES and the indicators were explored.

Results.

Up to 81% of the cancer deaths presented at least one indicator of aggressive EOL care. Those who were aged 35–44 years and male, had low SES, had metastatic malignant disease, lived in urban areas, or were in hospitals with more abundant health care resources were more likely to receive aggressive EOL care. In multilevel logistic regression analyses, high-SES cancer deaths had less chemotherapy (p < .001), fewer ER visits (p < .001), fewer ICU admissions (p < .001), and lower rates of dying in acute hospitals (p < .001) compared with low-SES cancer deaths.

Conclusion.

Working-age terminal cancer patients in Taiwan received aggressive EOL care. EOL cancer care was even more aggressive in those with low SES. Public health strategies should continue to focus on low-SES patients to provide them with better EOL cancer care.

Abstract

摘要

背景. 低社会经济地位(SES)与工作年龄(18 ∼ 65 岁)癌症患者积极的临终(EOL)治疗之间的关系尚未明确。本研究在 2009 ∼ 2011 年间评估了台湾地区工作年龄罹患终末期癌症患者积极的 EOL 治疗与 SES 差异之间的相关性。

方法. 从台湾地区全民健康保险研究数据库共鉴别出 32 800 例癌症死亡患者。研究调查了患者死亡前一个月内积极 EOL 治疗的指标[化疗、急诊(ER)就诊或入院≥1 次、住院≥14 天、重症监护室(ICU)住院、在综合医院死亡],并探索了 SES 与这些指标之间的相关性。

结果. 81%的癌症死亡者至少有一项积极 EOL 治疗指标。年龄在 35 ∼ 44 岁之间、男性、低 SES、转移性恶性肿瘤、生活在城市地区或在有较多卫生健康资源的医院就诊的癌症患者接受积极 EOL 治疗的可能性更高。多层次 logistic 回归分析中,与低 SES 癌症死亡者相比,高 SES 癌症死亡者化疗(P < 0.001)、ER 就诊次数(P < 0.001)、ICU 住院次数均较少(P < 0.001),在综合医院死亡的比例也较低(P < 0.001)。

结论. 台湾地区工作年龄的终末期癌症患者接受了积极的EOL治疗。而低SES人群接受了更为积极的EOL癌症治疗。公共卫生策略应该继续关注低SES患者,为他们提供更好的EOL癌症治疗。The Oncologist 2014;19:1241–1248

Implications for Practice:

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a factor in health care disparities. This study assessed the association between aggressive end-of-life (EOL) care and SES in working-age cancer decedents from Taiwan between 2009 and 2011. The findings show that patients of low SES experienced more aggressive EOL care (chemotherapy, more than one emergency room visit, intensive care unit admission, and death in an acute care hospital) than high-SES patients. Public health strategies are needed to ensure low-SES patients receive high-quality EOL cancer care, and to better allocate health care resources for a sustainable health care system.

Introduction

Cancer accounts for nearly 30% of all deaths in Taiwan and ∼25%–30% of all deaths in some Western countries [1–3]. End-of-life (EOL) cancer care has become increasingly aggressive over the past decade [3–5]. Treatment for all patients in their last year of life accounted for more than one quarter of Medicare spending in the U.S. [6]. Notably, the payments for care during the last 2 months of life spiked and accounted for about half of the payments for the last year of life in the U.S. [7]. The cost trajectories for terminal cancer patients were similar in Canada [8]; however, aggressive EOL care is not positively associated with higher quality care, enhanced family satisfaction, or lower mortality rates [9, 10].

Taiwan was classified as a high-income country by the World Trade Institute [11] and has had a universal health insurance system since 1995. Studies from Taiwan and from some Western countries found that socioeconomic status (SES) caused inequalities in health [12–23]. The rates of death from cancer were higher in low-SES populations [12–18]. In the U.S., SES patterns in incidence varied for specific cancers, whereas such patterns for cancer stages were generally consistent across cancers, with late-stage diagnoses associated with lower SES [17–19]. Low-SES patients have less access to medical resources and high-volume service providers [20–22]. Patients with lower educational levels receive less information and are less involved in therapeutic decisions [23]. In terms of SES and the aggressiveness of EOL cancer care, previous studies from the U.S., Canada, and Taiwan demonstrated that elderly, female, nonwhite, and unmarried patients were less likely to receive aggressive EOL cancer care [3–5]. In addition, EOL care was not found to be significantly more aggressive in low-income terminal cancer patients in Canada [3]. A few studies from the U.S. found contradictory results [24, 25]; however, most studies explored the relationship between SES and EOL cancer care based on data from cancer patients aged 65 years and older.

The association between SES and EOL care has not been fully explored in terminal younger cancer patients. It is not well known whether SES affects EOL care differently in working-age cancer patients (those aged older than 18 years and younger than 65 years). The purpose of this population-based study was to assess the association between aggressiveness of EOL care and SES in working-age terminal cancer patients in Taiwan between 2009 and 2011.

Patients and Methods

Ethics Statements

This study was initiated after being approved by the institutional review board of the Buddhist Dalin Tzu Chi General Hospital in Taiwan. Because the identification numbers and personal information of the patients included in the study were not included in the secondary files, the review board stated that written consent from patients was not required.

Patients and Study Design

We identified all adult cancer patients between 2009 and 2011 from the Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) Research Database. Taiwan’s NHI has the characteristics of universal insurance coverage, comprehensive services, and a single-payer system with the government as the sole insurer. These databases were monitored for completeness and accuracy by Taiwan’s Department of Health. These cancer patients were then linked to the National Register of Deaths Database. A total of 78,613 adult cancer deaths between 2009 and 2011 were identified in the National Register of Deaths Database.

Measures

Aggressiveness of EOL Care

The indicators of aggressiveness of EOL care were adapted from Earle et al. [4, 26]. This variable was assessed by six indicators in the last month of life: use of chemotherapy, more than one emergency room [ER] visit, more than one hospital admission, more than 14 days of hospitalization, an intensive care unit (ICU) admission, or death in an acute-care hospital. Data on these indicators were collected from NHI databases of inpatient or outpatient claims for the last month of life. We scored 1 point per indicator per person. This composite score ranged from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating more aggressive EOL care.

Patient Demographics

Patient characteristics included age, sex, cancer diagnosis, postdiagnosis survival time, disease severity, primary physician’s specialty, urbanization level of residence, geographic location, and SES. For each patient, disease severity was based on the modified Charlson Comorbidity Index score. Comorbidities were identified from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes in NHI claims for inpatients within 6 months before death. Metastatic status was identified by ICD-9 codes 196.xx to 199.xx. Diagnosis and metastatic status were combined in seven subgroups of cancers that were homogeneous in terms of survival and disease course [27, 28]. Subgroups included four cancer types: germ cell tumors and prostate cancer; lung, liver, and pancreatic cancer; hematologic malignancies; and all other cancers. Except for hematologic malignancies, each cancer type was further categorized by its metastatic status. The primary physician’s specialty was identified from NHI claims and was dichotomized into oncologist and other specialties.

Individual Socioeconomic Status

This study used enrollee category as a proxy measure for SES, which is an important prognostic factor for cancer [29]. Cancer patients were classified into three subgroups: high SES (civil servants, full-time or regular paid personnel with a government affiliation, or employees of privately owned institutions), moderate SES (self-employed persons, other employees, and members of the farmers or fishermen associations), and low SES (veterans, low-income families, and substitute service draftees) [30].

Statistical Analysis

SPSS (version 15; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, http://www-01.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/) was used to analyze the data. Univariate associations were evaluated by Pearson’s chi-square test. The impact of each explanatory variable on the aggressiveness of EOL care was examined by hierarchical linear regression analysis using a random-intercept model, which accounts for patients clustering within hospitals and the continuous nature of the composite score for EOL care. Multilevel logistic regression was used to explore the association between SES and the indicators of aggressive EOL care.

Results

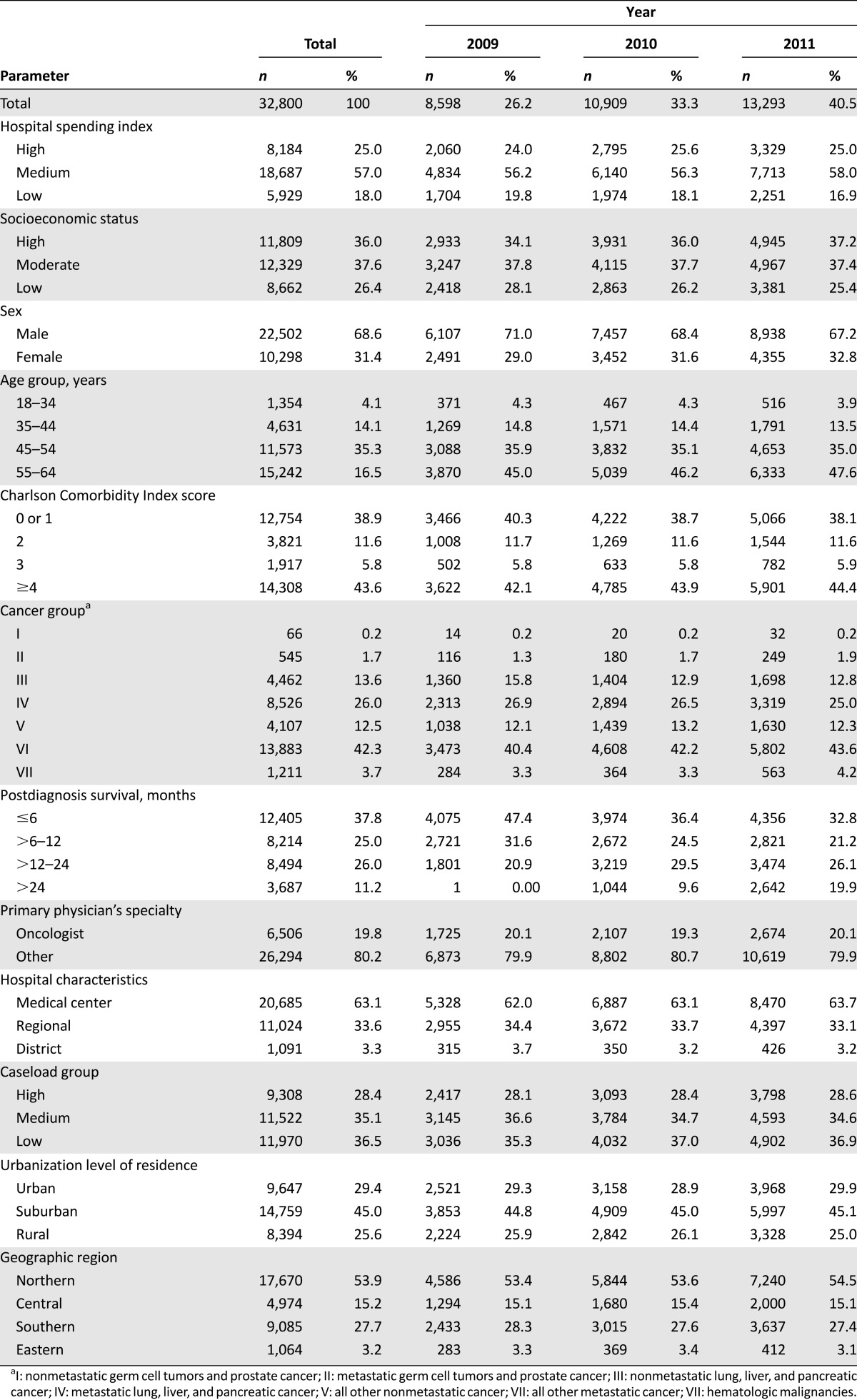

Among all adult cancer deaths in Taiwan, 32,800 (41.7%) were cancer deaths for the group aged 18–64 years. Baseline characteristics of the working-age patients who died from cancer are shown in Table 1. The mean age of death was 52 ± 8 years. The majority of cancer deaths (81.8%) occurred in people aged 45–64 years. Most of the working-age patients who died from cancer (70%) had metastatic disease, and 37.8% of those patients survived less than 6 months after diagnosis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

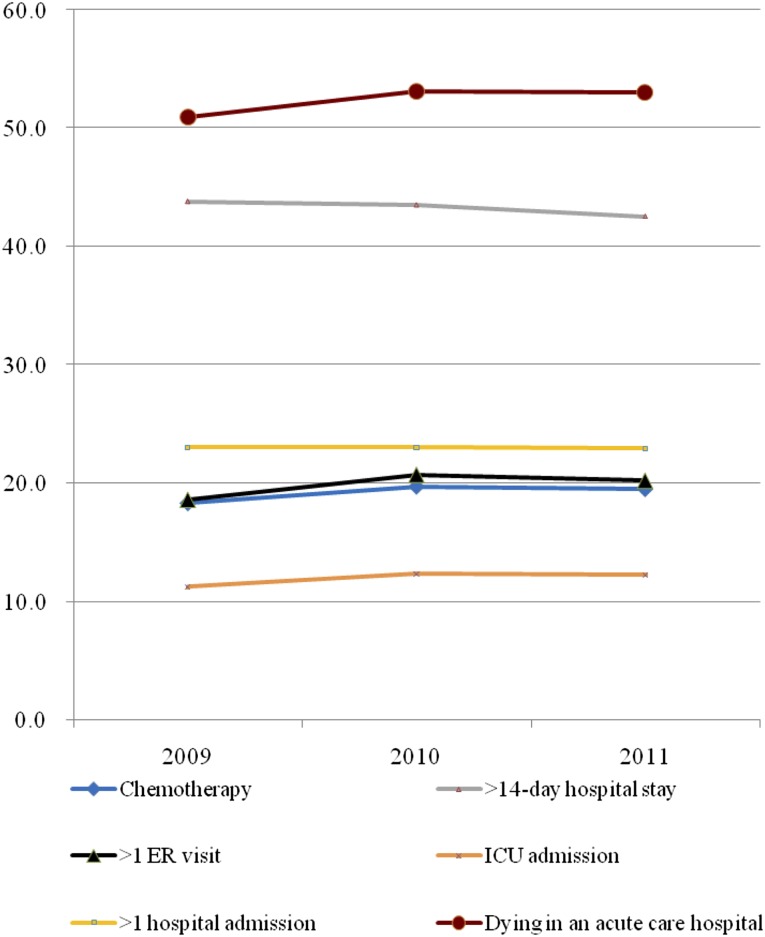

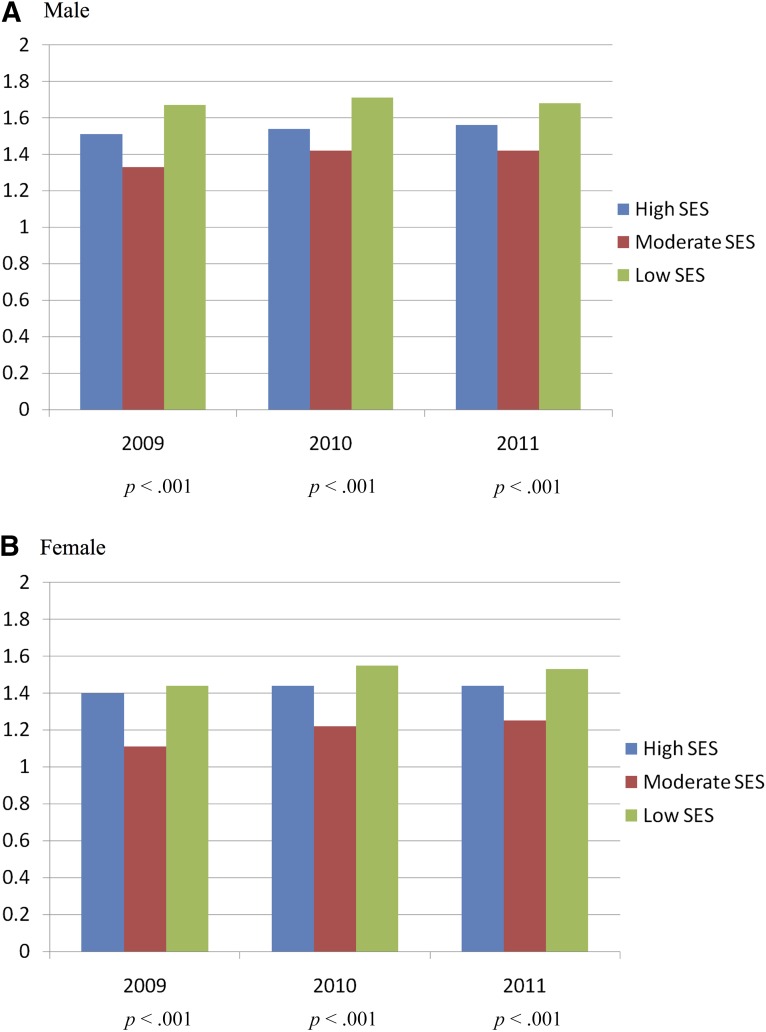

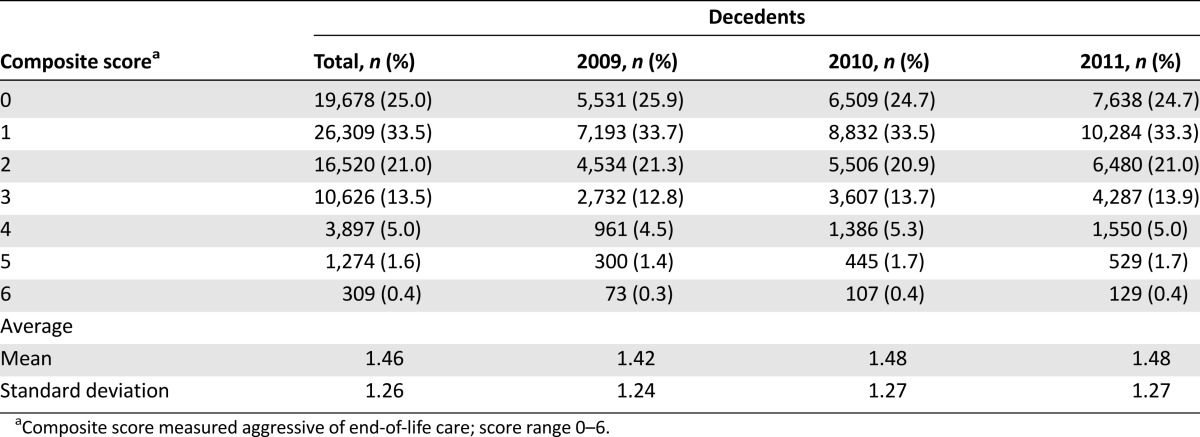

Figure 1 shows the distribution of each indicator for the aggressiveness of EOL care. The aggressiveness of EOL care for terminal cancer patients increased slightly over the 3 years studied. Overall, 81% of the patients had at least one indicator of aggressive care. The mean 3-year composite score for aggressiveness of EOL care was 1.46 ± 1.26 (Table 2). The unadjusted 3-year mean composite scores for high-, moderate-, and low-SES patients were 1.50, 1.33, and 1.64 (p < .001), respectively. For male patients of high, moderate, and low SES, the 3-year mean scores were 1.54, 1.40, and 1.68 (p < .001), respectively. For female patients of high, moderate, and low SES, the 3-year mean scores were 1.43, 1.20, and 1.51 (p < .001) respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Trends of the six indicators of aggressive end-of-life care for Taiwanese terminal cancer patients from 2009 to 2011.

Abbreviations: ER, emergency room; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 2.

Trends in aggressiveness of end-of-life care for Taiwanese terminal cancer patients from 2009 to 2011

Figure 2.

Mean composite score for aggressiveness of end-of-life (EOL) cancer care. The figure shows the association among EOL cancer care, individual SES, and age in male patients (A) and in female patients (B).

Abbreviation: SES, socioeconomic status.

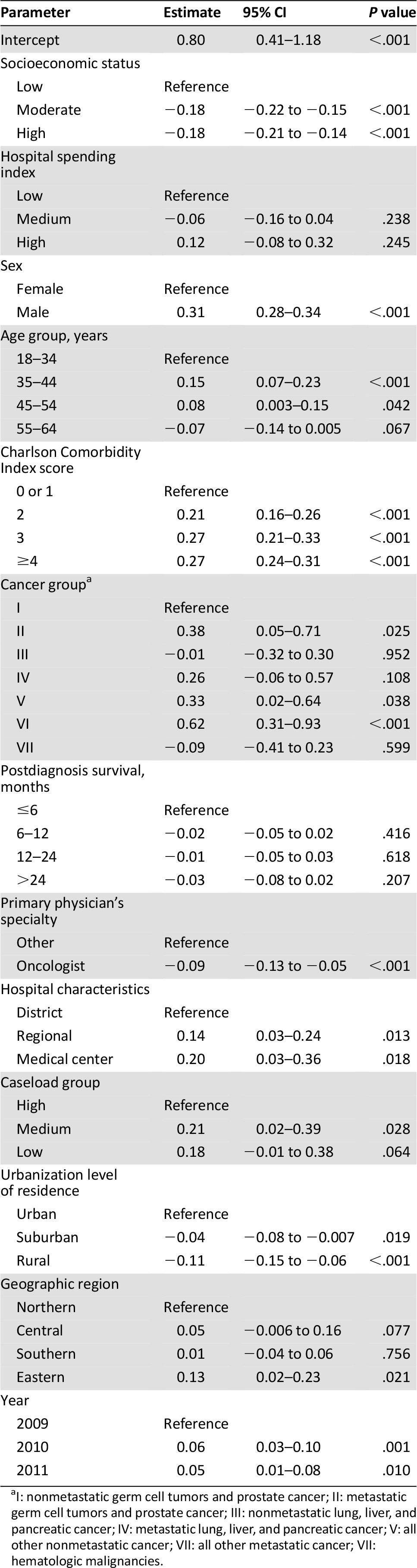

After adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics, hierarchical linear regression revealed that the composite scores for aggressiveness of EOL care in patients with high and moderate SES were 0.18 lower than in low-SES patients (p < .001) (Table 3). Controlling for the other variables, death in 2010 and 2011 significantly increased EOL care. EOL care was more aggressive for men than for women and more aggressive for those with metastatic disease than for those without metastatic disease and was most aggressive in patients aged 35–45 years compared with other age groups. Patients received more aggressive EOL care in medical centers and regional hospitals compared with district hospitals. More aggressive EOL care was performed in urban areas compared with rural areas. The level of comorbidity increased the aggressiveness of EOL care. EOL care was less aggressive in terminal cancer patients cared for by oncologists than by other specialists.

Table 3.

Determinants of aggressive end-of-life care for Taiwanese terminal cancer patients from 2009 to 2011 by multivariate analysis using a random-intercept model

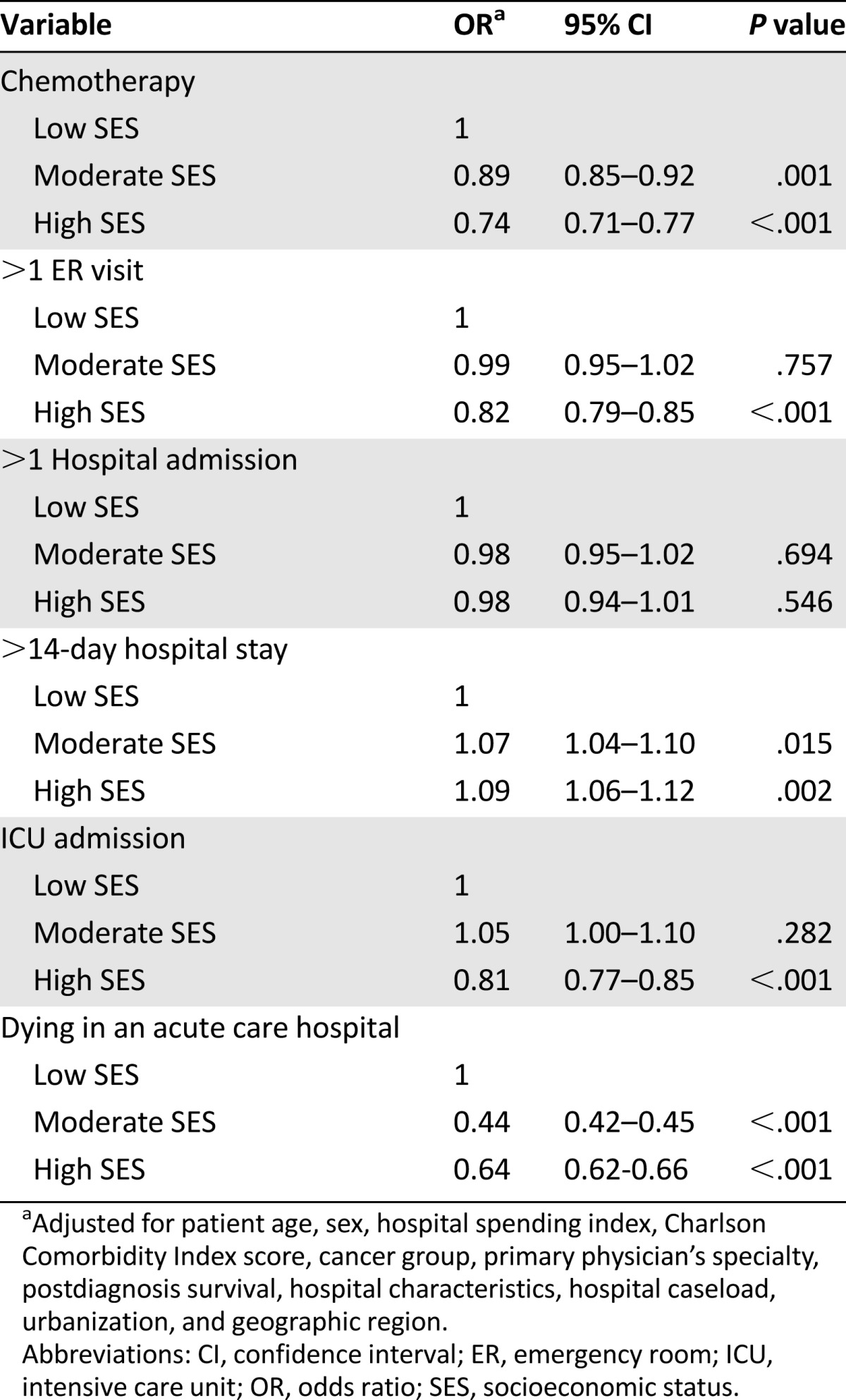

In Table 4, multilevel logistic regression analysis found that high-SES terminal cancer patients were associated with less chemotherapy (p < .001), fewer ER visits (p < .001), less ICU admission (p < .001), and lower rates of dying in acute-care hospitals (p < .001) when compared with low-SES terminal cancer patients. Terminal cancer patients with low SES were associated with more aggressive EOL care.

Table 4.

Multilevel adjusted odd ratios in terminal cancer patients according to socioeconomic status

Discussion

In this national database study of 32,800 working-age cancer deaths in Taiwan from 2009 to 2011, we found an increasing propensity toward using aggressive care near the end of life. Among working-age terminal cancer patients, the aggressiveness of end-of-life care differed according to individual SES. Low-SES terminal cancer patients were associated with more aggressive EOL care. They were more likely to receive chemotherapy, to have frequent ER visits and ICU admissions, and to die in an acute-care hospital.

The strengths of this study include a nationwide population-based cross-sectional design with nearly complete follow-up information about access to health care institutes among the whole study population (99%). In addition, the data set was routinely monitored for diagnostic accuracy by the National Health Insurance Bureau of Taiwan. Overall, 41.7% of adults who died from cancer in Taiwan were of working age. Examining this large group of cancer deaths might give us a clearer picture of the aggressiveness of EOL care in the working-age population. Most research explored determinants of aggressiveness of EOL care in older cancer deaths, and the results require validation in younger cohorts. For elderly patients, old age has an impact on treatment decision making for many diseases [12, 31]. Older cancer patients tend to receive less aggressive treatment [3–5, 31]. With regard to young age, our findings indicated that younger patients received significantly more aggressive EOL care. The group of terminal cancer patients aged 35–45 years received the most aggressive EOL care, and the aggressiveness decreased with age. Other determinants, such as male sex, metastatic disease, and additional comorbidities, agree with previous studies from cancer deaths in those aged 65 years and older.

A great body of literature has addressed the relationship between SES and mortality [12–19]. Low SES influences treatment of patients’ diseases in many ways. Some studies have revealed that minority, older, and low-SES patients were more likely to be treated in low-volume hospitals [20, 21]. A study from Taiwan explored the effects of SES on cancer survival and revealed that cancer patients younger than 65 years with low individual SES were less likely to undergo surgery compared with patients of high individual SES [12]. In the present study, this trend of disparity, in which low-SES cancer patients tend to receive less favorable medical service, seems to persist in end-of-life care for low-SES working-age cancer patients.

Quality palliative and end-of-life care is an international human right [32–34]. Studies have shown that more than 100 million people would annually benefit from palliative care (including family and caregivers who need help and assistance in caring; however, less than 8% of those who would benefit from palliative care are able to access it [35]. Although reducing untimely and preventable deaths is a well-established global health priority, improving the quality of life of those who are dying has been ignored [36]. Dying is expensive, but high costs do not necessarily produce a good death [36]. The burden of cost in providing EOL care in high-income countries is incurred in the last 2 months of life, as doctors, patients, and families use exhaustive measures to extend life by a few days [6, 7, 37]. In Taiwan, the costs of health care are rising yearly [38]. Caring for the dying is fundamental and important to reduce unnecessary suffering [36]. It also requires good stewardship of national health care resources for the sustainability of the ever-increasing demands of health care expenditures.

With regard to end-of-life care, persistent use of chemotherapy at the end of life emerges as the most important indicator of poor-quality care [26]. There are many rationales for physicians to recommend chemotherapy with very limited potential benefits, and this approach might be seen as providing hope and treating cancers [39]. It has been observed that patients may request an aggressive therapeutic approach near the end of life. They may not understand their true prognosis or may have unrealistic expectations about the benefits of chemotherapy [40].

In a survey of Medicare beneficiaries from the U.S., the observed geographic variation in end-of-life treatment could not be completely explained by patient preferences [41], suggesting that physician practice style is also a major driver [42]. Nevertheless, many factors may differentially influence physician practice styles, such as the individual hospital microclimate [42] or the patient’s communicative behavior [23]. Our finding indicates that socioeconomic status could be one of the factors. Patients with lower SES are often disadvantaged due to the doctor’s misperception of their desire and need for information and their ability to take part in the care process [23]. They receive significantly less positive socioemotional support, have less involvement in treatment decisions, receive less treatment information, and have less control over communication [23].

Social isolation, depression, and occupational stress are more prevalent among patients with low SES [43, 44], and the greater isolation of low-SES patients may make it difficult for them to obtain useful opinions or advice from relatives, friends, or acquaintances [44]. The insurance payer and health care provider may actively provide low-SES terminal cancer patients with more discussions about changing treatment approaches from fighting cancer to providing symptomatic and supportive care and cooperate with social welfare workers to help them understand the prognostic information and increase family satisfaction and support.

This study has limitations. First, diagnosis of cancer, and any comorbidity, was completely dependent on ICD-9 codes. Nonetheless, the National Health Insurance Bureau of Taiwan randomly reviews the charts and interviews patients to verify diagnostic accuracy. Second, cancer patients cannot always be considered terminally ill. The appropriateness of aggressive EOL care depends on an accurately defined population of patients dying from cancer or complications from curative cancer treatment. This distinction could not be ascertained from the NHI claims database.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the results of this study are informative. The aggressiveness of EOL care increased over the 3 years studied, as did the health care costs in Taiwan [38]. The present study shows that 81% of Taiwanese working-age terminal cancer patients between 2009 and 2011 experienced some form of aggressive EOL care. The rates of more than 14 days of hospitalization and dying in an acute-care hospital were high. It has been reported that less than one-third of adult Taiwanese terminal cancer patients and approximately half of their families reported that the health care professionals had informed them about the prognosis and discussed the goals of future care with them [45]. In addition, only one in six Taiwanese cancer patients use hospice care in their last year of life [46]. There is a need to develop a quality palliative care system and to provide terminal cancer patients with access to care information that best meets their needs. The present study further indicates that Taiwanese working-age terminal cancer patients with low SES received more aggressive EOL care including chemotherapy, more ER visits, ICU admission, and death in an acute-care hospital. This information may help authorities develop policies to ensure better use of health care resources for a sustainable health care system and quality EOL care for working-age terminal cancer patients. Public health strategies should continue to focus on low-SES patients to provide them with better EOL cancer care.

Acknowledgments

This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health and managed by the National Health Research Institutes (registered number 101115). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent the opinions of the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, or National Health Research Institutes.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Chun-Ming Chang, Chin-Chia Wu, Wen-Yao Yin, Ching-Chih Lee

Provision of study material or patients: Shiun-Yang Juang, Chia-Hui Yu, Ching-Chih Lee

Collection and/or assembly of data: Shiun-Yang Juang, Chia-Hui Yu, Ching-Chih Lee

Data analysis and interpretation: Chun-Ming Chang, Chin-Chia Wu, Wen-Yao Yin, Shiun-Yang Juang, Chia-Hui Yu, Ching-Chih Lee

Manuscript writing: Chun-Ming Chang, Ching-Chih Lee

Final approval of manuscript: Chun-Ming Chang, Chin-Chia Wu, Wen-Yao Yin, Shiun-Yang Juang, Chia-Hui Yu, Ching-Chih Lee

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. Five years outcome of national program for cancer prevention. Available at http://www.hpa.gov.tw/BHPNet/Web/HealthTopic/TopicBulletin.aspx?No=201009170001&parentid=200712250030. Accessed July 4, 2014.

- 2.Brustugun OT, Møller B, Helland A. Years of life lost as a measure of cancer burden on a national level. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1014–1020. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho TH, Barbera L, Saskin R, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1587–1591. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.9897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang ST, Wu SC, Hung YN, et al. Determinants of aggressive end-of-life care for Taiwanese cancer decedents, 2001 to 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4613–4618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riley GF, Lubitz JD. Long-term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:565–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lubitz JD, Riley GF. Trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1092–1096. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304153281506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fassbender K, Fainsinger RL, Carson M, et al. Cost trajectories at the end of life: the Canadian experience. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teno JM, Mor V, Ward N, et al. Bereaved family member perceptions of quality of end-of-life care in U.S. regions with high and low usage of intensive care unit care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1905–1911. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, et al. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:288–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WTI country classification by region and income. Available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTRANETTRADE/Resources/239054-1261083100072/Country_Classification_by_Region_Income_Dec17.pdf. Accessed July 4, 2014.

- 12.Chang CM, Su YC, Lai NS, et al. The combined effect of individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on cancer survival rates. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang TS, Chang CM, Hsu TW, et al. The combined effect of individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on nasopharyngeal cancer survival. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu CC, Hsu TW, Chang CM, et al. The effect of individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on gastric cancer survival. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunst AE, del Rios M, Groenhof F, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in stroke mortality among middle-aged men: An international overview. Stroke. 1998;29:2285–2291. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.11.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2468–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manser CN, Bauerfeind P. Impact of socioeconomic status on incidence, mortality, and survival of colorectal cancer patients: A systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:42.e9–60.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: Selected findings from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:417–435. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9256-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Refaie WB, Muluneh B, Zhong W, et al. Who receives their complex cancer surgery at low-volume hospitals? J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu JH, Zingmond DS, McGory ML, et al. Disparities in the utilization of high-volume hospitals for complex surgery. JAMA. 2006;296:1973–1980. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang CM, Yin WY, Wei CK, et al. The association of socioeconomic status and access to low-volume service providers in breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e81801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willems S, De Maesschalck S, Deveugele M, et al. Socio-economic status of the patient and doctor-patient communication: Does it make a difference? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nayar P, Qiu F, Watanabe-Galloway S, et al. Disparities in end of life care for elderly lung cancer patients. J Community Health. 2014;39:1012–1019. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9850-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe-Galloway S, Zhang W, Watkins K, et al. Quality of end-of-life care among rural Medicare beneficiaries with colorectal cancer. J Rural Health. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jrh.12074. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, et al. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1133–1138. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell DE, Lynn J, Louis TA, et al. Medicare program expenditures associated with hospice use. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:269–277. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-4-200402170-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanvetyanon T, Leighton JC. Life-sustaining treatments in patients who died of chronic congestive heart failure compared with metastatic cancer. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:60–64. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braaten T, Weiderpass E, Lund E. Socioeconomic differences in cancer survival: The Norwegian Women and Cancer Study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:178. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CY, Liu CY, Su WC, et al. Factors associated with the diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders: A population-based longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e435–e443. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rietjens JA, Deschepper R, Pasman R, et al. Medical end-of-life decisions: Does its use differ in vulnerable patient groups? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1282–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gwyther L, Brennan F, Harding R. Advancing palliative care as a human right. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:767–774. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brennan F. Palliative care as an international human right. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radbruch L, Payne S, de Lima L, et al. The Lisbon Challenge: Acknowledging palliative care as a human right. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:301–304. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. http://www.thewpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on-end-of-life-care. Accessed July 5, 2014.

- 36.Darzi L, Hughes-Hallett T, Cleary J et al. Dying healed: Transforming end-of-life care through innovation. Available at http://www.wish-qatar.org/app/media/386. Accessed July 5, 2014.

- 37.Neuberg GW. The cost of end-of-life care: A new efficiency measure falls short of AHA/ACC standards. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:127–133. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.829960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan. Available at http://www.Mohw.Gov.Tw/cht/dos/statistic.Aspx? F_list_no=312&fod_list_no=4534. Accessed July 5, 2014.

- 39.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, et al. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: Is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3860–3866. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee SJ, Fairclough D, Antin JH, et al. Discrepancies between patient and physician estimates for the success of stem cell transplantation. JAMA. 2001;285:1034–1038. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voogt E, van der Heide A, Rietjens JA, et al. Attitudes of patients with incurable cancer toward medical treatment in the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2012–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences?: A Study of the US Medicare Population. Med Care. 2007;45:386–393. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255248.79308.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marmot MG. Stress, social and cultural variations in heart disease. J Psychosom Res. 1983;27:377–384. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(83)90069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang JJ, Snyder M, Kaas M. Stress, loneliness, and depression in Taiwanese rural community-dwelling elders. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38:339–347. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang ST, Liu TW, Lai MS, et al. Congruence of knowledge, experiences, and preferences for disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis between terminally-ill cancer patients and their family caregivers in Taiwan. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:360–366. doi: 10.1080/07357900600705284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang ST, Huang EW, Liu TW, et al. A population-based study on the determinants of hospice utilization in the last year of life for Taiwanese cancer decedents, 2001-2006. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1213–1220. doi: 10.1002/pon.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]