Abstract

Background

Epidemiologic studies examining circulating levels of inflammatory markers in relation to obesity and physical inactivity may aid in our understanding of the role of inflammation in obesity-related cancers. However, previous studies on this topic have focused on a limited set of markers.

Methods

We evaluated associations between body mass index (BMI) and vigorous physical activity level, based on self-report, and serum levels of 78 inflammation-related markers. Markers were measured using a bead-based multiplex method among 1,703 men and women, ages 55–74 years and with no prior history of cancer at blood draw, selected for case-control studies nested within the Prostate, Lung, Ovarian, and Colorectal Cancer Screening Trial. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, smoking, case-control study, physical activity, and BMI.

Results

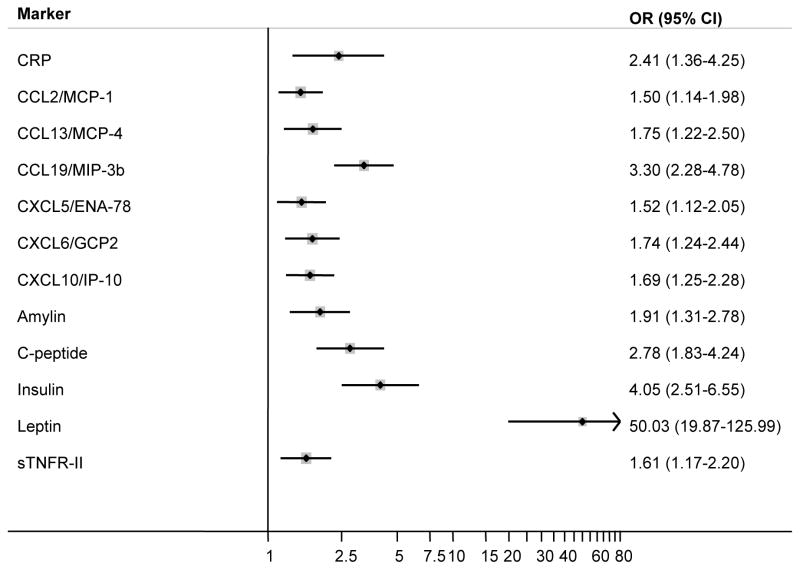

Twelve markers were positively associated with BMI after False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CIs) for highest versus lowest levels of CCL2/MCP-1, CXCL5/ENA-78, sTNFR-II, CXCL10/IP-10, CXCL6/GCP2, CCL13/MCP-4, amylin, CRP, C-peptide, CCL19/MIP-3b, insulin, and leptin were 1.50 (1.14–1.98), 1.52 (1.12–2.05), 1.61 (1.17–2.20), 1.69 (1.25–2.28), 1.74 (1.24–2.44), 1.75 (1.22–2.50), 1.91 (1.31–2.78), 2.41 (1.36–4.25), 2.78 (1.83–4.24), 3.30 (2.28–4.78), 4.05 (2.51–6.55), 50.03 (19.87–125.99) per 5-kg/m2, respectively. Only CXCL12/SDF-1a was associated with physical activity (≥3 versus <1 hours/week; OR=3.28, 95% CI: 1.55–6.94) after FDR correction.

Conclusions

BMI was associated with a wide range of circulating markers involved in the inflammatory response.

Impact

This cross-sectional analysis identified serum markers could be considered in future studies aimed at understanding the underlying mechanisms linking inflammation with obesity and obesity-related cancers.

INTRODUCTION

Low-grade inflammation plays an important role in the development and progression of numerous obesity-related chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and is a hypothesized mechanism in the development of some types of cancer (1–4). In obesity, proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6, are secreted by adipocytes and macrophages in the adipose tissue and aid in the progression of insulin resistance (1). In recent epidemiologic studies, higher circulating levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 were associated with obesity and physical inactivity (5–10), as well as elevated risks of certain obesity-related cancers (11–13), suggesting that these and/or related inflammatory markers may play a mediating role in the associations between obesity, physical inactivity, and these cancers. However, due largely to sample requirements and cost restraints, most studies have focused on a limited number of inflammatory markers, which may not fully characterize the specific aspects of the inflammatory response that underlie the associations between obesity, physical inactivity, and obesity-related cancers (14).

In the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial, multiplex panels were used to measure a large number of inflammatory, immune, and metabolic markers. In a cross-sectional analysis, we evaluated body mass index (BMI) and vigorous physical activity level in relation to a broad range of markers (n=78) involved in the inflammatory response, including acute phase proteins, chemokines, cytokines, peptide hormones, and soluble receptors, measured among over 1,700 participants who were cancer-free at the time of blood draw.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The PLCO Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) recruited approximately 155,000 55–74 year-old men and women from the general population between 1992 and 2001 (15). In addition to demographic, behavioral, and dietary information, including self-reported measures of current and past height and weight and current frequency of vigorous physical activity, non-fasting blood samples were obtained at baseline and at five subsequent annual visits from participants in the screening arm. Cancer diagnoses were ascertained through annual questionnaires and confirmed by medical chart abstraction and death certificate review; in the screening arm, additional prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancers were identified as a result of clinical follow-up after a positive screening test. PLCO was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each screening center and at the National Cancer Institute, and all participants gave informed consent.

We combined data from three nested case-control studies (i.e., studies of lung cancer, ovarian cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma [NHL]) that were previously conducted in the screening arm of the PLCO (16, 17). Detailed information on the inclusion criteria, matching factors and inflammatory markers measured in these nested case-control studies is presented in Table 1. The lung cancer study included 526 cases matched to 592 controls, the NHL study included 301 cases matched to 301 controls, and the ovarian cancer study was limited to females and included 150 cases matched to 149 controls. For all three studies, inflammatory markers were measured from single blood samples collected at either baseline (lung cancer and NHL studies) or two or more years before diagnosis date in cases or referent diagnosis date in controls (ovarian cancer study). From 2,013 participants included in one or more of the three nested case-control studies, we excluded participants who did not report being non-Hispanic white (n=152), individuals with a personal history of cancer prior to randomization (n=31) and incomplete data on cigarette smoking (n=11), height and weight (n=21), and physical activity level (n=95), for a total of 1,703 unique individuals, all of whom were cancer-free at the time of blood draw. These individuals included 431 cases and 501 controls in the lung cancer study, 275 cases and 266 controls in the NHL study, and 120 cases and 110 controls in the ovarian cancer study.

Table 1.

Description of three case-control studies nested within the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial.

| Lung cancer | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Ovarian cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| # Cases | 526 | 301 | 150 |

| # Controls | 592 | 301 | 149 |

| Sample volume (μL) | 370 | 425 | 290 |

| Inclusion criteria | Intervention arm | Intervention arm | Females in intervention arm |

| Baseline questionnaire | Baseline questionnaire | Baseline questionnaire | |

| Follow-up | Follow-up | Follow-up | |

| Biochemical consent | Biochemical consent | Biochemical consent | |

| Valid smoking history | No rare cancer | No rare cancer in controls | |

| Prior history of cancer | Prior history of cancer | No controls with oophorectomy | |

| Baseline serum specimens | Baseline serum specimens | 2+ years pre-diagnosis serum specimen | |

| Matching criteria | Age at randomization (5-year) | Age at randomization (5-year) | Age at randomization (5-year) |

| Sex | Race | Race | |

| Year of randomization | Sex | Study year of blood draw | |

| Smoking history | Study center | Year of blood draw | |

| Pack-years smoked | Entry season/year | Season of blood draw | |

| Years since quitting smoking | Time of blood draw (am/pm) | Time of blood draw (am/pm) | |

| Exit date | |||

| Panels tested* | Cytokine panel 1a (22-plex) | Cytokine panel 1a (22-plex) | Cytokine panel 1a (22-plex) |

| Cytokine panel 1b (15-plex) | Cytokine panel 1b (15-plex) | Cytokine panel 1b (15-plex) | |

| Cytokine panel II (17-plex) | Cytokine panel II (17-plex) | --- | |

| Cytokine panel III (7-plex) | Cytokine panel III (7-plex) | --- | |

| Cardiovascular disease panel (3-plex) | --- | CRP only | |

| Soluble receptor panel (13-plex) | Soluble receptor panel (13-plex) | Soluble receptor panel (13-plex) | |

| --- | Metabolic hormone panel (9-plex) | Metabolic hormone panel (9-plex) | |

| Total number of markers | 77 | 83 | 60 |

See Supplementary Table 2 for a list of markers included in each panel.

Laboratory Analysis

Serum specimens collected either at baseline or at a follow-up visit (processed at 1200 × g for 15 minutes, frozen within 2 hours of collection, stored at −70°C) were used to measure circulating levels of 86 markers, including 77 markers in the lung cancer study (using 370 μL), 60 in the ovarian cancer study (using 290 μL), and 83 in the NHL study (using 425 μL). For a list of markers by case-control study and by marker panel, see Tables 1 and 2. These markers were selected based on a recent methodologic study that evaluated the performance and reproducibility of multiplexed assays for measurement of inflammation markers in serum/plasma (18). Markers were measured using Luminex bead-based assays (EMD Millipore; Billerica, MA), as previously described (16–18). Concentrations were calculated using either a four- or five-parameter standard curve. Serum samples were assayed in duplicate and averaged to calculate concentrations. Blinded duplicates in the lung and NHL studies and duplicate measurements on study subjects in the ovary study were used to evaluate assay reproducibility through coefficients-of-variation (CVs) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) calculated on log-transformed values of the markers. ICCs were >0.8 in 91% of the markers in the lung and NHL studies and in 78% of the markers in the ovarian cancer study. Eight markers with >90% of values below the lowest limit of detection (LLOD) were excluded from all analyses, resulting in 78 evaluable markers.

Table 2.

Multiplex immune panel markers measured in the PLCO Cancer Screening Study

| Cytokine Panel 1a | Cytokine Panel 1b | Cytokine Panel 2 | Cytokine Panel 3 | Metabolic Disease Panel | Soluble Receptor Panel | CVD Panel 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bead type Sample volume (μL) |

Magnetic 80 |

Magnetic 80 |

Magnetic 80 |

Magnetic 80 |

Magnetic 80 |

Polystyrene 25 |

Polystyrene 25 |

| Analyte 1 | EGF | GM-CSF | BCA-1 | CCL19/MIP-3b | Insulin | sCD30a | CRP |

| Analyte 2 | Eotaxin | IL-10 | CKINE | CCL20/MIP-3a | Leptin | sEGFRb | SAA |

| Analyte 3 | FGF-basicb | IL-12 (p70) | CTACK | CXCL11/I-TAC | GIP (total) | sGP130b | SAP |

| Analyte 4 | FLT-3 ligand | IL-15 | CXCL5/ENA-78 | CXCL6/GCP2 | Polypeptide | sIL-1RIa | |

| Analyte 5 | Fractalkine | IL-17 | Eotaxin | CXCL9/MIG | PYY (total) | sIL-4R | |

| Analyte 6 | G-CSFb | IL-1b | IL-16a | IL-11 | GLP-1 (active) | sIL-6Rb | |

| Analyte 7 | GRO | IL-1Ra | IL-33 | IL-29/IFN-g1 | Amylin (total) | sIL-1RII | |

| Analyte 8 | IFN-a2 | IL-2b | LIFa | C-peptide | sRAGEa | ||

| Analyte 9 | IFN-gb | IL-3a | CCL8/MCP-2 | Glucagon | sTNFRI | ||

| Analyte 10 | IL-12 (p40) | IL-4 | CCL13/MCP-4 | sTNFRIIb | |||

| Analyte 11 | IL-1a | IL-5 | CCL15/MIP-1d | sVEGFR1a | |||

| Analyte 12 | IL-8 | IL-6 | SCF | sVEGFR2b | |||

| Analyte 13 | CXCL10/IP-10 | IL-7 | CXCL12/SDF-1a | sVEGFR3 | |||

| Analyte 14 | CCL2/MCP-1 | TGF-α | TARC | ||||

| Analyte 15 | CCL7/MCP-3 | TNF-β | TPO | ||||

| Analyte 16 | CCL22/MDC | TRAIL | |||||

| Analyte 17 | CCL3/MIP-1a | TSLP | |||||

| Analyte 18 | CCL4/MIP-1b | ||||||

| Analyte 19 | sCD40L | ||||||

| Analyte 20 | sIL-2raa | ||||||

| Analyte 21 | TNF-α | ||||||

| Analyte 22 | VEGF |

Excluded from the analysis due to poor performance (>90% below the lower limit of detection)

Intraclass correlations <80% (lung cancer and NHL studies)

Statistical Analysis

As shown in Table 1, the inclusion and matching criteria, as well as the number of markers measured, differed across the nested case-control studies. To combine data from these studies, we accounted for these differences and made our analysis as representative as possible of the entire non-Hispanic white PLCO screening arm from which the case and control participants were sampled (as demonstrated in Table 3) by developing sets of propensity-score adjusted sampling weights for each participant (19, 20). The sampling weights allowed us to include all participants with marker data (including cancer cases) (see Supplementary Methods for details). Because markers were either measured in all three studies, in combinations of two studies, or the lung cancer study only, multi-study weights were used in analyses of these markers. To calculate the multi-study weights, screening arm participants who met the eligibility criteria of the combined dataset (i.e., completed the baseline questionnaire, gave biochemical consent, non-Hispanic white, no personal history of any cancer prior to randomization, and complete smoking history) were included in logistic regression models to estimate the probability of being selected into one of the case-control studies, including terms for age group [<59, 60–64, 65–69, ≥70 years], smoking history (i.e., smoking status, years since quit [<15, ≥15], and pack-years [<30, ≥30]), and vital status on December 31, 2009. As such, cases were given much lower weights than controls (Table 3). Models were estimated separately by case/control status, study, and sex. Study-specific weights were then combined for each of the five combinations of case-control studies with a common subset of panels (all three studies, lung and NHL, lung and ovary, NHL and ovary, and lung alone). These sampling weights are used in logistic regression models for each marker regressed on BMI, physical activity, and other confounders (including age, sex, and study to provide extra control for study-specific selection factors). Simulations suggest that analyses using both weighting methods and additional regression adjustment for matching factors provide a good way to adjust for non-representative sampling in nested case-control studies (21).

Table 3.

Selected characteristics of participants with measured inflammation marker data, unweighted and weighted, compared to all eligible participants in the PLCO screening arm

| Sample population | Sample population, weighted to PLCO screening arm | PLCO screening arm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total n | 1,703 | 58,264 | 58,264 |

| Sex, % | |||

| Women | 45 | 49 | 49 |

| Men | 55 | 51 | 51 |

| Age group, % | |||

| ≤59 | 21 | 32 | 34 |

| 60–64 | 29 | 35 | 31 |

| 65–69 | 30 | 19 | 22 |

| ≥70 | 19 | 14 | 13 |

| BMI category, % | |||

| <25 | 36 | 32 | 32 |

| 25–30 | 44 | 47 | 43 |

| ≥30 | 20 | 21 | 24 |

| Vigorous physical activity, % | |||

| <1 hour/week | 34 | 30 | 33 |

| 1–2 hours/week | 27 | 28 | 28 |

| ≥3 hours/week | 39 | 43 | 39 |

| Smoking status, % | |||

| Never | 30 | 46 | 47 |

| Former | 47 | 44 | 43 |

| Current | 22 | 10 | 10 |

| Original nested case-control study, % | |||

| Lung cancer | 55 | 42 | --- |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 32 | 42 | --- |

| Ovarian cancer | 14 | 16 | --- |

| Case-control status, % | |||

| Case | 49 | 1 | --- |

| Control | 52 | 99 | --- |

Inflammatory markers were grouped into study-specific categories according to the proportion below the LLOD: <25% (quartiles), 25–49% (undetectable and tertiles), 50–74% (undetectable, below median and above median for detected), and >75–90% (undetectable and detectable). We defined body mass index (BMI) as body weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, based on self-reported height and weight at baseline. Baseline BMI was modeled continuously (per 5-kg/m2) and categorically, with categories corresponding to values within the range of normal-weight, overweight, and obese (<25.0 [reference], 25.0–29.9, and ≥30.0 kg/m2, respectively). Because only 10 participants had a BMI value in the range of underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), we combined data from the underweight and normal-weight categories for the analysis. Participants were ask to report at baseline how many hours they spent in vigorous activities, such as swimming, brisk walking, etc., and were given the following options: none, <1, 1, 2, 3, or ≥4 hours per week. From these responses, we defined low, medium, and high levels of vigorous physical activity as <1, 1–2, and ≥3 hours per week, respectively.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) comparing the highest to lowest category for each inflammatory marker (dependent variable) with BMI and physical activity were calculated using weighted logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, cigarette smoking, case-control study. Models for BMI were additionally adjusted for physical activity, and vice versa. P-values from logistic regression models were based on the Wald test corresponding to the OR for the highest versus lowest inflammatory marker level. P-trends across categories of physical activity were based on the Wald test, treating physical activity as an ordinal variable. Tests for multiplicative interaction of sex and smoking on associations between BMI, physical activity, and marker levels, as well as interactions between BMI and physical activity on marker levels, were conducted by including a cross-product term in the models. To account for multiple comparisons, we identified all markers where the False Discovery Rate (FDR) was less than 5%.

RESULTS

The distribution of select demographic and behavioral characteristics of the participants in the study sample, before and after weighting to the PLCO screening arm, and all eligible participants in the PLCO screening arm are shown in Table 3. Compared to the entire PLCO screening arm, the study sample was generally older and included higher proportions of men (55 vs. 51%) and current smokers (22 vs. 10%) and slightly fewer individuals with BMI in the obesity range (20 vs. 24%). The distributions of these factors were similar between the study sample weighted to the PLCO screening arm and the entire PLCO screening arm.

Associations between BMI (per 5-kg/m2) and the highest versus lowest levels of all 78 markers are shown in Table 4. After accounting for multiple comparisons using FDR, BMI was significantly associated with 12 markers (CRP, CCL2/MCP-1, CCL13/MCP-4, CCL19/MIP-3b, CXCL5/ENA-78, CXCL6/GCP2, CXCL10/IP-10, amylin, C-peptide, insulin, leptin, and sTNFR-II) (Figure 1). Five of these markers (CCL19/MIP-3b, CXCL10/IP-10, C-peptide, insulin, and leptin) remained statistically significant after applying the more stringent Bonferroni correction. Higher levels of these markers were associated with greater BMI, with ORs ranging from 1.50 for CCL2/MCP-1 to 50.03 for leptin. To aid in evaluating the independence of these associations, the correlation structure of the markers among controls, by study, is shown in Supplementary Table 1a–c. Based on controls in the NHL study, restricting to marker levels above the lower level of detection, correlations were generally weak (ρ=<0.1) or moderate (ρ=0.1–0.39), with the strongest correlations observed for C-peptide and insulin (ρ=0.77), C-peptide and amylin (ρ=0.75), and insulin and amylin (ρ=0.73). In general, the results presented above were consistent with those from logistic regression models with BMI modeled categorically (Supplementary Table 2) and by case-control study (Supplementary Table 3), and were not significantly modified by sex or physical activity level (P-interactions >0.05). Furthermore, the magnitudes of the associations did not change importantly (e.g., <10% changes) after excluding lung cancer, NHL, or ovarian cancer cases from the models or after additional adjustment for self-reported history of diabetes (yes, no, missing). Similar findings were observed when using an ordered logistic model as opposed to a multinomial logistic regression model. We observed a significant interaction between BMI and smoking status on the association with insulin (P-interaction=0.03), with stronger association for current (OR=7.57, 95% CI: 1.22–47.04) and never (OR=5.30, 95% CI: 2.38–11.82) compared with former (OR=3.94, 95% CI: 1.88–8.28) smokers.

Table 4.

Odds ratios (ORs)a and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for 78 circulating inflammation markers and body mass index (per 5 kg/m2)

| Markerb | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| CKINE | 1.01 (0.73–1.39) | 0.95 |

| Amylin | 1.91 (1.31–2.78) | 0.001 |

| BCA-1 | 1.35 (0.96–1.89) | 0.09 |

| C-peptide | 2.78 (1.83–4.24) | 2.0e-06 |

| CCL19/MIP-3b | 3.30 (2.28–4.78) | 2.54e-10 |

| CCL20/MIP-3a | 1.20 (0.91–1.59) | 0.20 |

| CRP | 2.41 (1.36–4.25) | 0.003 |

| CTACK | 0.82 (0.57–1.18) | 0.29 |

| CXCL11/I-TAC | 1.39 (0.99–1.95) | 0.06 |

| CXCL6/GCP2 | 1.74 (1.24–2.44) | 0.001 |

| CXCL9/MIG | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) | 0.37 |

| EGF | 1.31 (0.97–1.76) | 0.07 |

| CXCL5/ENA-78 | 1.52 (1.12–2.05) | 0.007 |

| EOTAXIN | 0.79 (0.59–1.06) | 0.11 |

| EOTAXIN_2 | 1.10 (0.79–1.52) | 0.57 |

| FGF_2 | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) | 0.84 |

| FRACTALKINE | 1.19 (0.88–1.61) | 0.26 |

| G_CSF | 1.20 (0.92–1.56) | 0.18 |

| GIP | 1.26 (0.89–1.78) | 0.19 |

| GLP-1 | 1.07 (0.79–1.44) | 0.68 |

| GLUCAGON | 1.15 (0.79–1.66) | 0.47 |

| GM_CSF | 1.10 (0.86–1.41) | 0.44 |

| GRO | 0.75 (0.56–1.00) | 0.05 |

| IFN-a2 | 1.07 (0.78–1.46) | 0.69 |

| IFNG | 1.13 (0.85–1.49) | 0.40 |

| IL-10 | 0.70 (0.46–1.05) | 0.08 |

| IL-11 | 0.99 (0.76–1.29) | 0.93 |

| IL-12 (p40) | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) | 0.36 |

| IL-12 (p70) | 0.83 (0.56–1.23) | 0.35 |

| IL-15 | 0.84 (0.62–1.16) | 0.29 |

| IL-16 | 1.20 (0.83–1.74) | 0.34 |

| IL-17 | 1.05 (0.81–1.38) | 0.70 |

| IL-1a | 0.94 (0.71–1.24) | 0.65 |

| IL-1b | 0.90 (0.60–1.35) | 0.61 |

| IL-1Ra | 0.90 (0.69–1.18) | 0.45 |

| IL-2 | 0.91 (0.70–1.18) | 0.47 |

| IL-29/IFN-g1 | 1.03 (0.73–1.44) | 0.89 |

| IL-33 | 1.02 (0.77–1.36) | 0.90 |

| IL-4 | 1.08 (0.84–1.38) | 0.56 |

| IL-5 | 1.25 (0.93–1.69) | 0.14 |

| IL-6 | 0.96 (0.68–1.36) | 0.82 |

| IL-7 | 0.90 (0.69–1.18) | 0.44 |

| IL-8 | 1.01 (0.76–1.35) | 0.92 |

| Insulin | 4.05 (2.51–6.55) | 9.22e-09 |

| CXCL10/IP-10 | 1.69 (1.25–2.28) | 0.001 |

| Leptin | 50.03 (19.87–125.99) | 1.11e-16 |

| CCL2/MCP-1 | 1.50 (1.14–1.98) | 0.004 |

| CCL8/MCP-2 | 1.23 (0.89–1.70) | 0.20 |

| CCL7/MCP-3 | 1.03 (0.76–1.40) | 0.84 |

| CCL13/MCP-4 | 1.75 (1.22–2.50) | 0.002 |

| CCL22/MDC | 1.46 (1.09–1.95) | 0.01 |

| CCL3/MIP-1a | 1.02 (0.75–1.38) | 0.90 |

| CCL4/MIP-1b | 1.23 (0.93–1.63) | 0.15 |

| CCL15/MIP-1d | 1.10 (0.77–1.59) | 0.60 |

| PP | 1.22 (0.84–1.76) | 0.29 |

| PYY | 1.04 (0.70–1.54) | 0.87 |

| SAA | 1.38 (0.81–2.35) | 0.24 |

| SAP | 1.52 (0.93–2.48) | 0.09 |

| sCD40L | 1.32 (0.99–1.76) | 0.06 |

| SCF | 1.38 (1.01–1.88) | 0.04 |

| CXCL12/SDF-1a | 0.93 (0.66–1.31) | 0.66 |

| sEGFR | 1.00 (0.74–1.35) | 0.98 |

| sGP130 | 1.20 (0.90–1.59) | 0.22 |

| sIL-4R | 0.86 (0.64–1.16) | 0.32 |

| sIL-6R | 1.19 (0.90–1.58) | 0.22 |

| sIL-RII | 1.04 (0.79–1.37) | 0.78 |

| sTNFRI | 1.31 (0.98–1.76) | 0.07 |

| sTNFRII | 1.61 (1.17–2.20) | 0.003 |

| sVEGFR2 | 1.03 (0.76–1.40) | 0.84 |

| sVEGFR3 | 1.06 (0.79–1.43) | 0.69 |

| TARC | 1.05 (0.74–1.48) | 0.80 |

| TGF-α | 1.12 (0.82–1.52) | 0.48 |

| TNF-β | 0.93 (0.67–1.30) | 0.66 |

| TNF-α | 1.46 (1.09–1.96) | 0.01 |

| TPO | 0.71 (0.50–1.02) | 0.06 |

| TRAIL | 1.29 (0.91–1.81) | 0.15 |

| TSLP | 1.06 (0.79–1.42) | 0.72 |

| VEGF | 1.17 (0.88–1.56) | 0.29 |

ORs represent the association between highest vs. lowest inflammation marker level in relation to body mass index. All models adjusted for age (continuous), sex, cigarette smoking status (never, former, current), case-control study (lung, NHL, ovary), and physical activity level (<1, 1–2, ≥3 hours/week)

Bolded= statistically significant after FDR correction for multiple comparisons

Figure 1.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for select circulating inflammation markers and body mass index (BMI, per 5 kg/m2). ORs were estimated using logistic regression models and represent the association between highest vs. lowest level of a specific inflammation marker in relation to BMI. All models adjusted for age (continuous), sex, cigarette smoking status (never, former, current), case-control study of origin (lung, NHL, ovary), and physical activity level (<1, 1–2, ≥3 hours/week). Markers shown are the ones that remained statistically-significantly associated with body mass index after correction for multiple comparisons.

Associations between vigorous physical activity and levels of all 78 markers are shown in Table 5. Only CXCL12/SDF-1a remained significant after correcting for multiple comparisons using the FDR method (OR=3.28, 95% CI: 1.55–6.94) when those who reported vigorous physical activity of three or more hours per week were compared to those who reported no vigorous physical activity.

Table 5.

Odds ratios (ORs)a and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for 78 circulating inflammation markers and category of vigorous physical activity (1–2 and ≥3 hours/week vs. <1 hour/week)

| Markerb | 1–2 hr/wk | ≥3 hr/wk | P-trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | |||

| CKINE | 0.59 (0.29–1.23) | 1.00 (0.48–2.08) | 0.91 |

| Amylin | 1.48 (0.58–3.77) | 1.28 (0.56–2.91) | 0.61 |

| BCA-1 | 1.35 (0.62–2.93) | 1.51 (0.72–3.16) | 0.28 |

| C-peptide | 0.94 (0.37–2.34) | 0.60 (0.27–1.37) | 0.18 |

| CCL19/MIP-3b | 1.35 (0.64–2.68) | 1.34 (0.67–2.68) | 0.44 |

| CCL20/MIP-3a | 1.07 (0.55–2.09) | 0.69 (0.35–1.37) | 0.25 |

| CRP | 0.89 (0.34–2.36) | 0.48 (0.20–1.14) | 0.09 |

| CTACK | 0.98 (0.46–2.08) | 1.67 (0.81–3.45) | 0.15 |

| CXCL11/I-TAC | 0.63 (0.29–1.41) | 0.62 (0.28–1.35) | 0.25 |

| CXCL6/GCP2 | 0.76 (0.35–1.62) | 1.25 (0.61–2.53) | 0.49 |

| CXCL9/MIG | 1.08 (0.52–2.22) | 1.07 (0.53–2.19) | 0.88 |

| EGF | 0.96 (0.50–1.83) | 1.14 (0.62–2.10) | 0.67 |

| CXCL5/ENA-78 | 1.17 (0.56–2.44) | 1.59 (0.74–3.38) | 0.22 |

| EOTAXIN | 0.89 (0.47–1.70) | 1.03 (0.54–1.96) | 0.90 |

| EOTAXIN_2 | 1.29 (0.62–2.66) | 0.52 (0.25–1.07) | 0.05 |

| FGF_2 | 0.77 (0.39–1.53) | 0.82 (0.43–1.59) | 0.59 |

| FRACTALKINE | 0.76 (0.39–1.47) | 1.07 (0.56–2.03) | 0.81 |

| G_CSF | 0.90 (0.49–1.64) | 0.90 (0.51–1.57) | 0.72 |

| GIP | 1.41 (0.56–3.56) | 1.82 (0.81–4.12) | 0.15 |

| GLP-1 | 0.71 (0.33–1.51) | 1.13 (0.57–2.26) | 0.72 |

| GLUCAGON | 1.17 (0.48–2.81) | 2.13 (0.95–4.80) | 0.48 |

| GM_CSF | 1.30 (0.68–2.48) | 0.89 (0.47–1.68) | 0.65 |

| GRO | 0.57 (0.30–1.09) | 0.49 (0.26–0.91) | 0.03 |

| IFN-a2 | 0.42 (0.21–0.84) | 0.69 (0.37–1.28) | 0.31 |

| IFNG | 0.81 (0.45–1.46) | 0.91 (0.52–1.57) | 0.77 |

| IL-10 | 0.70 (0.34–1.43) | 0.79 (0.40–1.56) | 0.56 |

| IL-11 | 0.67 (0.37–1.22) | 0.82 (0.47–1.44) | 0.55 |

| IL-12 (p40) | 0.90 (0.49–1.66) | 0.94 (0.54–1.62) | 0.83 |

| IL-12 (p70) | 0.74 (0.38–1.45) | 0.87 (0.46–1.65) | 0.34 |

| IL-15 | 1.36 (0.74–2.50) | 1.13 (0.63–2.02) | 0.76 |

| IL-16 | 0.48 (0.22–1.03) | 0.52 (0.25–1.08) | 0.10 |

| IL-17 | 0.75 (0.40–1.42) | 0.72 (0.39–1.30) | 0.28 |

| IL-1a | 0.72 (0.40–1.30) | 0.97 (0.56–1.68) | 0.98 |

| IL-1b | 0.86 (0.42–1.75) | 0.88 (0.44–1.76) | 0.73 |

| IL-1Ra | 1.11 (0.64–1.91) | 1.04 (0.61–1.77) | 0.92 |

| IL-2 | 0.95 (0.55–1.65) | 0.95 (0.57–1.59) | 0.86 |

| IL-29/IFN-g1 | 0.49 (0.23–1.06) | 0.58 (0.28–1.21) | 0.17 |

| IL-33 | 0.94 (0.50–1.77) | 0.85 (0.46–1.56) | 0.58 |

| IL-4 | 0.58 (0.34–1.01) | 0.67 (0.40–1.12) | 0.16 |

| IL-5 | 0.70 (0.35–1.39) | 1.24 (0.67–2.31) | 0.44 |

| IL-6 | 0.49 (0.23–1.04) | 0.95 (0.51–1.77) | 0.97 |

| IL-7 | 0.73 (0.42–1.27) | 0.91 (0.51–1.64) | 0.84 |

| IL-8 | 0.59 (0.30–1.16) | 0.65 (0.34–1.22) | 0.20 |

| Insulin | 1.10 (0.42–2.83) | 0.98 (0.41–2.37) | 0.99 |

| CXCL10/IP-10 | 1.04 (0.52–2.09) | 0.88 (0.46–1.69) | 0.66 |

| Leptin | 0.60 (0.16–2.27) | 0.30 (0.10–0.89) | 0.02 |

| CCL2/MCP-1 | 0.86 (0.44–1.68) | 0.85 (0.46–1.58) | 0.62 |

| CCL8/MCP-2 | 0.96 (0.45–2.04) | 1.32 (0.65–2.68) | 0.43 |

| CCL7/MCP-3 | 0.67 (0.34–1.29) | 0.75 (0.40–1.39) | 0.39 |

| CCL13/MCP-4 | 0.79 (0.36–1.74) | 0.96 (0.43–2.10) | >0.99 |

| CCL22/MDC | 0.64 (0.32–1.28) | 0.63 (0.32–1.24) | 0.20 |

| CCL3/MIP-1a | 0.66 (0.33–1.28) | 1.56 (0.83–2.94) | 0.12 |

| CCL4/MIP-1b | 0.84 (0.45–1.56) | 0.98 (0.52–1.82) | 0.98 |

| CCL15/MIP-1d | 1.00 (0.46–2.18) | 0.80 (0.39–1.65) | 0.53 |

| PP | 0.77 (0.33–1.80) | 1.43 (0.64–3.19) | 0.28 |

| PYY | 0.66 (0.23–1.93) | 1.08 (0.40–2.93) | 0.81 |

| SAA | 1.06 (0.32–3.48) | 0.74 (0.25–2.16) | 0.57 |

| SAP | 1.72 (0.58–5.08) | 1.07 (0.41–2.82) | 0.95 |

| sCD40L | 0.79 (0.43–1.48) | 0.84 (0.44–1.59) | 0.62 |

| SCF | 0.93 (0.45–1.91) | 1.37 (0.69–2.72) | 0.35 |

| CXCL12/SDF-1a | 1.83 (0.82–4.06) | 3.28 (1.55–6.94) | 0.002 |

| sEGFR | 1.07 (0.53–2.16) | 2.07 (1.04–4.11) | 0.03 |

| sGP130 | 1.29 (0.65–2.55) | 1.67 (0.88–3.16) | 0.12 |

| sIL-4R | 1.45 (0.75–2.82) | 1.18 (0.64–2.18) | 0.64 |

| sIL-6R | 0.85 (0.43–1.68) | 0.94 (0.50–1.76) | 0.87 |

| sIL-RII | 1.35 (0.69–2.63) | 1.36 (0.69–2.65) | 0.39 |

| sTNFRI | 0.54 (0.26–1.09) | 0.76 (0.42–1.37) | 0.41 |

| sTNFRII | 1.25 (0.60–2.62) | 1.20 (0.65–2.22) | 0.58 |

| sVEGFR2 | 1.08 (0.53–2.23) | 1.01 (0.51–2.01) | 0.99 |

| sVEGFR3 | 0.87 (0.43–1.77) | 0.92 (0.47–1.81) | 0.83 |

| TARC | 1.27 (0.55–2.89) | 1.69 (0.78–3.67) | 0.17 |

| TGF-α | 0.50 (0.25–0.99) | 0.67 (0.36–1.28) | 0.30 |

| TNF-β | 0.57 (0.29–1.14) | 0.76 (0.40–1.44) | 0.45 |

| TNF-α | 0.49 (0.25–0.97) | 0.80 (0.41–1.55) | 0.70 |

| TPO | 0.91 (0.43–1.90) | 0.60 (0.30–1.20) | 0.13 |

| TRAIL | 1.25 (0.59–2.65) | 1.62 (0.80–3.29) | 0.18 |

| TSLP | 0.93 (0.49–1.80) | 0.82 (0.44–1.56) | 0.55 |

| VEGF | 1.34 (0.70–2.58) | 1.11 (0.60–2.07) | 0.79 |

P-trend calculated by modeling physical activity categories as continuous and evaluating the statistical significance of the corresponding Wald test

ORs represent the association between highest vs. lowest inflammation marker level in relation to physical activity. All models adjusted for age (continuous), sex, cigarette smoking status (never, former, current), case-control study (lung, NHL, ovary), and body mass index (per 5 kg/m2)

Bolded= statistically significant after FDR correction for multiple comparisons

DISCUSSION

We found that, after FDR correction for multiple comparisons, BMI was independently associated with 12 markers involved in the inflammatory response, including acute phase proteins, peptide hormones, chemokines, cytokines, and soluble receptors. Only SDF-1a was independently associated with vigorous physical activity in this analysis. Our findings support broad effects of adiposity on inflammation and immunity, and identify specific markers for future studies of obesity-related cancers.

The connection between obesity and chronic, low grade inflammation, characterized by elevated levels of adipokines (e.g., leptin), pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IL-6), acute phase reactant proteins (e.g., CRP), markers of insulin resistance (e.g., insulin and C-peptide), and chemoattractant proteins (e.g., MCP-1) in adipose tissue is well-established based on results of mechanistic studies (3). Similarly, previous epidemiologic studies have observed elevated circulating levels of the inflammatory markers leptin, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 associated with greater BMI and waist circumference (5, 6, 8, 22), as well as visceral adipose tissue (6). Our results, particularly those for leptin, insulin, C-peptide, CRP, and MCP-1, were consistent with these observations. Although less well-studied, other associations that we observed in relation to BMI, including sTNFR-II (5, 23) and amylin (24), were in the expected direction, as was the non-significant inverse association we observed between physical activity level and CRP (8, 10). Our results confirmed those observed in the Women’s Health Study cohort, in which CRP was more strongly positively associated with BMI compared with physical activity level (8). BMI was associated with several additional markers that were not independently associated with physical activity level (e.g., C-peptide, insulin, leptin, CCL15/MIP-1d, CCL19/MIP-3b, CXCL11/I-TAC, and sTNFR-I). Although the differences in associations we observed for BMI and physical activity may reflect differences in inflammatory mechanisms, less accurate reporting of physical activity compared with height and weight may partially explain the weaker associations that we observed for physical activity (25). We also have incomplete information on total physical activity level, as the baseline questionnaire only elicited information on vigorous physical activity and did not inquire about light-to-moderate intensity physical activity, which may also contribute, independently or in combination with vigorous physical activity, to inflammatory marker levels.

Our results showing that established obesity and/or physical inactivity-related markers were in the expected direction and magnitude indicates that the multiplex immune marker panels performed well in comparison with singleplex assays used in other studies. This provides reassurance regarding the more novel findings of our study, particularly those for several chemokines. To our knowledge, no previous epidemiologic study has examined the associations for BMI or physical activity with the chemokines evaluated in the current study. However, recent mechanistic studies indicate that numerous chemokines, including CCL3/MIP-1a, CCL5/RANTES, CCL7/MCP-3, CCL19/MIP-3b, CXCL1/KC, CXCL5/ENA-78, CXCL8/IL-8, CXCL10/IP-10, and the well-studied CCL2/MCP-1 (3), are expressed in adipose tissue under obesity-associated chronic inflammation, and that these chemokines may work in concert to promote macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue and subsequent insulin resistance (26). Expression of these chemokines appears to be induced by TNF-α stimulation in adipose tissue and regulated by NF-κB (25). Similarly, we found that BMI was associated with a number of chemokines (e.g., CCL2/MCP-1, CCL13/MCP-4, CCL19/MIP-3b, CCL22/MDC, CXCL5/ENA-78, CXCL6/GCP2, and CXCL10/IP-10). These associations appeared to be independent due to the low correlations between these markers. CXCL12/SDF-1a, which was associated with vigorous physical activity in the current analysis, has also been inversely associated with blood glucose and peripheral insulin resistance (27). These potentially novel BMI- and physical activity-associated markers require confirmation in future epidemiologic studies, but, if confirmed, these markers could be considered along with those that have been established in future efforts to evaluate associations with obesity-related cancers, and to evaluate underlying mechanisms in laboratory-based studies.

In a few instances, we did not observe expected associations. This is exemplified by IL-6 and IL-1Ra, where the previous literature has consistently reported associations with greater adiposity and/or physical activity (6, 10, 28), but these associations were not observed in the current study. The fact that we did not observe associations for these two markers suggests that the sensitivity of the multiplex assays to detect IL-6 and IL-1Ra levels (with 29% and 22% above the LLOD, respectively) was low compared to individual ELISAs, as has been noted elsewhere (17). These findings may help investigators choose the best platform for measuring inflammatory markers for epidemiologic studies.

The results of this study could be used to help determine the pathways involved in obesity-related inflammation that are relevant to the development of obesity-related cancers. Few epidemiologic studies to date have evaluated pre-diagnostic, circulating levels of the inflammation-related markers examined in the current study with risk of obesity-related malignancies, including endometrial, postmenopausal breast, pancreatic, and colorectal cancers. Most focused on only a limited set of inflammatory, immune, or metabolic markers, such as CRP, insulin, C-peptide, leptin, IL-6, and TNF-α (or its receptors, sTNR-I and –II) (11–13, 29–34). In contrast to individual ELISAs, the multiplex panel methods used to measure the markers in the current study relied on relatively small volumes of serum (maximum 400 μL). However, as it may be cost-prohibitive to measure the wide range of markers examined in the current study, researchers planning to prospectively evaluate levels of inflammatory markers in relation to obesity-related cancers could select promising markers based on the results of the current study.

The main strengths of our study included the comprehensive investigation of the relationship between BMI and physical activity and circulating immune- and inflammation-related markers measured using a well-characterized technology and a novel two-stage design to re-weight analyses to the screening arm of the population-based PLCO cohort. In addition, we were able to control for confounding by other factors that may be associated with these markers, such as cigarette smoking. There were also some limitations. We relied on BMI as a measure of total adiposity, which does not distinguish lean from fat body mass, and we did not have complete information on total physical activity level, only vigorous-intensity activity. Also, because height, weight, and physical activity were self-reported at one point in time, measurement error in these values may have attenuated the associations we observed. Because PLCO recruited only individuals between 55–74 years of age, our results may not generalize to other age groups. We had no information on fasting status or time of day of blood draw, and thus could not evaluate the influence of these factors on circulating marker levels. Finally, participants were not randomly sampled but were selected due to their inclusion in one of three prospective nested cancer case-control studies. Nonetheless, the weighting methods applied in our study adjusted for potential biases due to non-representative sampling from the source population (i.e., the non-Hispanic screening arm of the PLCO study).

In summary, we found in this cross-sectional study that BMI was associated with a wide range of circulating inflammatory, immune, and metabolic markers. Many of the associations we observed were in line with previous epidemiologic and mechanistic studies, while others were novel. These markers represent candidates for use in future epidemiologic studies designed to evaluate the extent to which inflammatory markers or marker pathways contribute to obesity and the risk of obesity-related cancers. Such studies could provide information on the biological mechanisms underlying these associations and subsequently identify specific potential targets for prevention.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

Financial disclosures: This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:415–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aroor AR, McKarns S, Demarco VG, Jia G, Sowers JR. Maladaptive immune and inflammatory pathways lead to cardiovascular insulin resistance. Metabolism. 2013;62:1543–52. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Kruijsdijk RC, van der Wall E, Visseren FL. Obesity and cancer: the role of dysfunctional adipose tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2569–78. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khandekar MJ, Cohen P, Spiegelman BM. Molecular mechanisms of cancer development in obesity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:886–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontes JD, Yamamoto JF, Larson MG, Wang N, Dallmeier D, Rienstra M, et al. Clinical correlates of change in inflammatory biomarkers: The Framingham Heart Study. Atherosclerosis. 2013;228:217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park HS, Park JY, Yu R. Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esposito K, Pontillo A, Di Palo C, Giugliano G, Masella M, Marfella R, et al. Effect of weight loss and lifestyle changes on vascular inflammatory markers in obese women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1799–804. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mora S, Lee IM, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Association of physical activity and body mass index with novel and traditional cardiovascular biomarkers in women. JAMA. 2006;295:1412–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ertek S, Cicero A. Impact of physical activity on inflammation: effects on cardiovascular disease risk and other inflammatory conditions. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:794–804. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.31614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamer M, Sabia S, Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Tabák AG, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Physical activity and inflammatory markers over 10 years: follow-up in men and women from the Whitehall II cohort study. Circulation. 2012;126:928–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.103879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dossus L, Rinaldi S, Becker S, Lukanova A, Tjonneland A, Olsen A, et al. Obesity, inflammatory markers, and endometrial cancer risk: a prospective case-control study. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:1007–19. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang T, Rohan TE, Gunter MJ, Xue X, Wactawski-Wende J, Rajpathak SN, et al. A prospective study of inflammation markers and endometrial cancer risk in postmenopausal hormone nonusers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:971–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlinger TP, Platz EA, Rifai N, Helzlsouer KJ. C-reactive protein and the risk of incidence colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2004;291:585–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaturvedi AK, Moore SC, Hildesheim A. Invited commentary: circulating inflammation markers and cancer risk—implications for epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:14–19. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prorok PC, Andriole GL, Bresalier RS, Buys SS, Chia D, Crawford ED, et al. Design of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:273S–309S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purdue MP, Hofmann JN, Kemp TJ, Chaturvedi AK, Lan Q, Park JH, et al. A prospective study of 67 serum immune and inflammation markers and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2013;122:951–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-481077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Hildesheim A, Engels EA, Kemp TJ, Park JH, et al. Circulating inflammation markers and prospective risk of lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1871–80. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaturvedi AK, Kemp TJ, Pfeiffer RM, Biancotto A, Williams M, Munuo S, et al. Evaluation of multiplexed cytokine and inflammation marker measurements: a methodologic study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1902–11. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of Health Surveys. 1. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Støer NC, Samuelsen SO. Inverse probability weighting in nested case-control studies with additional matching—a simulation study. Stat Med. 2013;32:5328–39. doi: 10.1002/sim.6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruige JB, Dekker JM, Blum WF, Stehouwer CD, Nijpels G, Mooy J, et al. Leptin and variables of body adiposity, energy balance, and insulin resistance in a population-based study. The Hoorn Study Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1097–104. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamska A, Nikolajuk A, Karczewska-Kupczewska M, Kowalska I, Otziomek E, Grska M, et al. Relationships between serum adiponectin and soluble TNF-α receptors and glucose and lipid oxidation in lean and obese subjects. Acta Diabetol. 2012;49:17–24. doi: 10.1007/s00592-010-0252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hou X, Sun L, Li Z, Mou H, Yu Z, Li H, et al. Association of amylin with inflammatory markers and metabolic syndrome in apparently healthy Chinese. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neilson HK, Robson PJ, Friedenreich CM, Csizmadi I. Estimating activity energy expenditure: how valid are physical activity questionnaires? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:279–91. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tourniaire F, Romier-Crouzet B, Lee JH, Marcotorchino J, Gouranton E, Salles J, et al. Chemokine expression in inflamed adipose tissue is mainly mediated by NF-κB. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallagher KA, Liu ZJ, Xiao M, Chen H, Goldstein LJ, Buerk DG, et al. Diabetic impairments in NO-mediated endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and homing are reversed by hyperoxia and SDF-1 alpha. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1249–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI29710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juge-Aubry CE, Somm E, Giusti V, Pernin A, Chicheportiche R, Verdumo C, et al. Adipose tissue is a major source of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: upregulation in obesity and inflammation. Diabetes. 2003;52:1104–10. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heikkilä K, Harris R, Lowe G, Rumley A, Yarnell J, Gallacher J, et al. Associations of circulating C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 with cancer risk: findings from two prospective cohorts and a meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:15–26. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9212-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grote VA, Kaaks R, Nieters A, Tjønneland A, Halkjær J, Overvad K, et al. Inflammation marker and risk of pancreatic cancer: a nested case-control study within the EPIC cohort. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1866–74. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Il’yasova D, Colbert LH, Harris TB, Newman AB, Bauer DC, Satterfield S, et al. Circulating levels of inflammatory markers and cancer risk in the health aging and body composition cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2413–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan AT, Ogino S, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS. Inflammatory markers are associated with risk of colorectal cancer and chemopreventive response to anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:799–808. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gross AL, Newschaffer CJ, Hoffman-Bolton J, Rifai N, Visvanathan K. Adipocytokines, inflammation, and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women: a prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1319–24. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ollberding NJ, Kim Y, Shvetsov YB, Wilkens LR, Franke AA, Cooney RV, et al. Prediagnostic leptin, adiponectin, C-reactive protein, and the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6:188–95. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.