Abstract

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in toll-like receptor (TLR) genes TLR2-4 and TLR7-9, but not in TLR1 and TLR6, have been previously evaluated regarding HIV acquisition and disease progression in various populations, most of which were European. In the present study, we examined associations between a total of 41 SNPs in 8 TLR genes (TLR1-4, TLR6-9) and HIV status in North American subjects (total n = 276 [Caucasian, n = 102; African American, n = 150; other, n = 24]). Stratification of the data by self-identified race revealed that a total of 9 SNPs in TLR1, TLR4, TLR6, and TLR8 in Caucasians, and 2 other SNPs, one each in TLR4 and TLR8, in African Americans were significantly associated with HIV status at P < 0.05. Concordant with the odds ratios of these SNPs, significant differences were observed in the SNP allele frequencies between HIV+ and HIV− subjects. Finally, in Caucasians, certain haplotypes of single (TLR1, TLR4) and heterodimer (TLR2_TLR6) genes may be inferred as “susceptible” or “protective”. Our study provides in-depth insight into the associations between TLR variants, particularly TLR1 and TLR6, and HIV status in North Americans, and suggests that these associations may be race-specific.

Keywords: African American, Caucasian, HIV, SNP, TLR1, TLR6

INTRODUCTION

Susceptibility to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and the rate of disease progression are variable among individuals and populations, and in part, genetically determined. Among a multitude of host genetic factors associated with susceptibility to HIV infection and/or disease progression, chemokine receptors, serving as HIV co-receptors, and their ligands have been well described.1 Outside the chemokine receptor-ligand nexus, host genetic factors that are associated with viral load control have been identified by recent genome-wide association studies.2 Among these, polymorphisms in innate immune response genes,3, 4 including those encoding β-defensins5, 6 and toll-like receptors (TLRs),7 have been found to affect the natural history of HIV infection and disease progression.

Toll-like receptors are the most important class of pattern recognition receptors, involved in the host defense against bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa.8–10 They are the primary molecular mechanism by which the host responds to invading microbes through the recognition of conserved motifs, which are termed pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The molecular interaction of TLRs with PAMPs and subsequent interactions with TLR adapters, kinases, and transcription factors trigger a cascade of signaling events that induce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.11, 12

There are 10 TLRs expressed in humans. TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6, and TLR10 are expressed largely on the cell surface, whereas TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 are intracellular (endosomal).13 Although the TLRs on the cell surface primarily recognize PAMPs of bacteria, fungi, and protozoa, TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR6 have also been shown to be involved in responses to viral infection.14 Similarly, the intracellular TLRs function primarily to detect viruses, although it has been shown that they detect other microbes as well.13 TLR2 heterodimerizes with TLR1 or TLR6.15 A recent report describes heterodimerization of TLR4 with TLR6.16

Studies evaluating TLR expression and response related to HIV have provided evidence that TLR1,17 TLR2,18–21 TLR3,20, 22, 23 TLR4,18–22, 24 TLR6,20 TLR7/8,20, 22, 25–27 and TLR922 play a functional role in HIV infection and disease. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in TLR2,28–32 TLR3,28–31 TLR4,28–32 TLR7,28–30, 33 TLR8,28–30, 34 and TLR928–32, 35 have been evaluated for their effects on HIV acquisition and disease progression in various populations under a variety of study designs. Although differences in populations, the number of markers (SNPs or combinations thereof), and outcome measures make the comparison of data difficult, 2 general conclusions may be drawn from these previous studies: (a) SNPs in TLR1 and TLR6 were not included in these studies and (b) only one of these studies was conducted in North America on predominantly white patients,31 whereas most were conducted in Europe,29, 32–35 and a few in Africa.28, 30

In the present study, we examined associations between a total of 41 SNPs in 8 TLR genes (TLR1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9) and HIV status in North American subjects belonging to 2 major races: Caucasian and African American. Many of the SNPs included in the study were from aforementioned HIV/AIDS studies.28–35 Other SNPs, including those in TLR1 and TLR6, have been evaluated in other infectious36–45 as well as inflammatory and immune-mediated non-infectious46–56 diseases. In addition to the SNP-based association analyses, we performed gene as well as heterodimer haplotype-based analyses. Our study provides in-depth insight into the role of TLR variants, particularly TLR1 and TLR6 variants, in susceptibility to or protection against HIV acquisition. Furthermore, our results suggest that the associations between TLR variants and HIV status may be race-specific.

RESULTS

Study populations

The demographic characteristics of HIV+ patient (n = 180) and HIV− random blood donor (n = 96) populations are summarized in Table 1. A majority of the HIV+ patients were African Americans and the sex distribution reflected the demographics of the clinic with a predominance of males. HIV− donor population had an equal representation of the Caucasian and African American races, and male and female sex.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study populations

| Characteristic | HIV+ (n = 180) | HIV− (n = 96) |

|---|---|---|

| Race† | ||

| Caucasian, n (%) | 54 (30) | 48 (50) |

| African American, n (%) | 102 (57) | 48 (50) |

| Other, n (%) | 24 (13) | 0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male, n (%) | 135 (75) | 47 (49) |

| Female, n (%) | 41 (23) | 47 (49) |

| Unknown, n (%) | 4 (2) | 2 (2) |

Self-identified.

HIV− subjects were random blood donors.

Minor allele frequency and potential batch effect

The minor allele frequency (MAF) of all 41 SNPs, according to the HIV status, as well as the HIV status stratified by race, are presented in Table 2. MAF ranged from 0.01 to 0.50. The MAF of all SNPs in HIV− Caucasians and African Americans were in agreement with those reported in the dbSNP database57 for comparable populations (Supplementary Table A). No difference in MAF of any of the SNPs was observed between the 2 plates containing samples from HIV+ patients (t-test, P > 0.05 for all comparisons).

Table 2.

Distribution of TLR minor alleles and their frequencies

| Gene (Chr #, ID) | rs number | SNP | MAF (allele) | MAF (allele) | MAF (allele) | MAF (allele) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| HIV+a | HIV− | HIV+ CA | HIV− CA | HIV+ AFA | HIV− AFA | |||

| TLR1 (#4, 7096) | rs5743551 | −7202G>A | 0.38 (A) | 0.44 (G) | 0.37 (G)1 | 0.16 (G)1 | 0.24 (A) | 0.27 (A) |

| rs5743595 | −2192T>C | 0.11 (C) | 0.09 (C) | 0.20 (C) | 0.14 (C) | 0.05 (C) | 0.05 (C) | |

| rs5743611 | 239G>C | 0.05 (C) | 0.05 (C) | 0.09 (C) | 0.09 (C) | 0.03 (C) | 0.01 (C) | |

| rs5743618 | 1805G>T | 0.31 (G) | 0.49 (T) | 0.44 (T)1 | 0.21 (T)1 | 0.16 (G) | 0.23 (G) | |

| TLR2 (#4, 7097) | rs4696480 | −16934T>A | 0.46 (A) | 0.39 (A) | 0.49 (T) | 0.40 (A) | 0.44 (A) | 0.39 (A) |

| rs1898830 | −15607A>G | 0.22 (G) | 0.26 (G) | 0.27 (G) | 0.36 (G) | 0.18 (G) | 0.14 (G) | |

| rs3804099 | 597T>C | 0.44 (T) | 0.48 (T) | 0.45 (T) | 0.46 (C) | 0.42 (T) | 0.42 (T) | |

| rs3804100 | 1350T>C | 0.05 (C) | 0.05 (C) | 0.04 (C) | 0.03 (C) | 0.04 (C) | 0.06 (C) | |

| rs5743708 | 2258G>A | 0.01 (A) | 0.02 (A) | 0.01 (A) | 0.03 (A) | 0.01 (A) | 0.01 (A) | |

| TLR3 (#4, 7098) | rs5743303 | −8921A>T | 0.16 (T) | 0.18 (T) | 0.20 (T) | 0.22 (T) | 0.15 (T) | 0.15 (T) |

| rs5743305 | −8441T>A | 0.38 (A) | 0.37 (A) | 0.43 (A) | 0.45 (A) | 0.37 (A) | 0.29 (A) | |

| rs3775296 | −299698G>T | 0.14 (T) | 0.19 (T) | 0.18 (T) | 0.22 (T) | 0.13 (T) | 0.16 (T) | |

| rs3775291 | 1234C>T | 0.16 (T) | 0.19 (T) | 0.29 (T) | 0.27 (T) | 0.07 (T) | 0.11 (T) | |

| TLR4 (#9, 7099) | rs2770150 | −3612A>G | 0.23 (G) | 0.22 (G) | 0.32 (G) | 0.31 (G) | 0.18 (G) | 0.14 (G) |

| rs2737190 | −2604G>A | 0.40 (A) | 0.50 (A) | 0.43 (G) | 0.26 (G) | 0.28 (A) | 0.26 (A) | |

| rs10759932 | −1607T>C | 0.23 (C) | 0.14 (C) | 0.21 (C)1 | 0.05 (C)1 | 0.24 (C) | 0.23 (C) | |

| rs4986790 | 896A>G | 0.06 (G) | 0.08 (G) | 0.06 (G) | 0.08 (G) | 0.06 (G) | 0.08 (G) | |

| rs4986791 | 1196C>T | 0.02 (T) | 0.05 (T) | 0.03 (T) | 0.08 (T) | 0.01 (T) | 0.01 (T) | |

| rs11536889 | +11381G>C | 0.06 (C) | 0.11 (C) | 0.08 (C) | 0.19 (C) | 0.03 (C) | 0.04 (C) | |

| rs7873784 | +12186C>G | 0.22 (C) | 0.14 (C) | 0.18 (C) | 0.15 (C) | 0.25 (C)2 | 0.13 (C)2 | |

| TLR6 (#4, 10333) | rs5743795 | −1401G>A | 0.11 (A) | 0.10 (A) | 0.19 (A) | 0.16 (A) | 0.05 (A) | 0.04 (A) |

| rs5743806 | −673C>T | 0.50 (C) | 0.42 (C) | 0.38 (C)3 | 0.24 (C)3 | 0.43 (T) | 0.40 (T) | |

| rs1039559 | −502T>C | 0.30 (C) | 0.41 (C) | 0.40 (C)4 | 0.41 (T)4 | 0.23 (C) | 0.23 (C) | |

| rs5743810 | 745T>C | 0.17 (T) | 0.33 (T) | 0.32 (T)4 | 0.49 (C)4 | 0.09 (T) | 0.15 (T) | |

| rs3821985 | 1083C>G | 0.48 (C) | 0.44 (G) | 0.39 (G) | 0.25 (G) | 0.39 (C) | 0.38 (C) | |

| rs3775073 | 1263A>G | 0.47 (A) | 0.45 (G) | 0.40 (G)3 | 0.25 (G)3 | 0.38 (A) | 0.35 (A) | |

| rs5743818 | 1932T>G | 0.17 (G) | 0.17 (G) | 0.28 (G) | 0.22 (G) | 0.10 (G) | 0.11 (G) | |

| rs2381289 | 4224C>T | 0.34 (T) | 0.33 (T) | 0.50 (T) | 0.40 (T) | 0.24 (T) | 0.26 (T) | |

| TLR7 (X, 51284) | rs2302267 | 1–120T>G | 0.03 (G) | 0.07 (G) | 0.05 (G) | 0.10 (G) | 0.02 (G) | 0.04 (G) |

| rs864058 | 2403G>A | 0.12 (A) | 0.17 (A) | 0.09 (A) | 0.14 (A) | 0.16 (A) | 0.19 (A) | |

| TLR8 (X, 51311) | rs3764880 | 1A>G | 0.28 (G) | 0.26 (G) | 0.39 (G)4 | 0.18 (G)4 | 0.24 (G) | 0.34 (G) |

| rs1548731 | +3121T>C | 0.50 (T) | 0.41 (T) | 0.30 (T) | 0.30 (T) | 0.39 (C) | 0.48 (C) | |

| rs5744077 | 28A>G | 0.06 (G) | 0.06 (G) | 0.00 (G) | 0.00 (G) | 0.10 (G) | 0.12 (G) | |

| rs2159377 | 354C>T | 0.11 (T) | 0.18 (T) | 0.16 (T) | 0.16 (T) | 0.09 (T)5 | 0.21 (T)5 | |

| rs5744080 | 645C>T | 0.38 (C) | 0.46 (C) | 0.45 (C) | 0.35 (T) | 0.30 (C) | 0.27 (C) | |

| rs2407992 | 1953G>C | 0.28 (G) | 0.41 (G) | 0.39 (G)4 | 0.35 (C)4 | 0.17 (G) | 0.16 (G) | |

| rs3747414 | 2253C>A | 0.33 (A) | 0.30 (A) | 0.44 (A) | 0.25 (A) | 0.30 (A) | 0.36 (A) | |

| TLR9 (#3, 54106) | rs187084 | −1486C>T | 0.38 (C) | 0.36 (C) | 0.37 (C) | 0.35 (C) | 0.39 (C) | 0.38 (C) |

| rs5743836 | −1237C>T | 0.26 (C) | 0.23 (C) | 0.17 (C) | 0.11 (C) | 0.33 (C) | 0.34 (C) | |

| rs352139 | +1174G>A | 0.44 (A) | 0.44 (A) | 0.49 (A) | 0.47 (G) | 0.39 (A) | 0.35 (A) | |

| rs352140 | 1635G>A | 0.43 (A) | 0.43 (A) | 0.47 (A) | 0.47 (A) | 0.43 (A) | 0.40 (A) | |

Linkage disequilibrium patterns

The pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns of TLR1, TLR4, TLR6, TLR8, and TLR1_TLR6, based on D′ ≥ 0.8 and r2 ≥ 0.5,58 for both HIV+ and HIV− Caucasians and African Americans are presented in Supplementary Table B. No strong LD was observed between SNPs in the TLR7_TLR8 gene pair.

Regression analysis of SNPs

Following logistic regression using all 276 samples, 3 of the 41 SNPs were significantly associated with modestly increased odds of HIV infection, after the correction for multiple testing (α = 0.001).59 These were: TLR1 rs5743551 (−7202G, odds ratio [OR] = 1.76; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.51, 2.18; P = 0.0005), TLR1 rs5743618 (1805T, OR = 1.71; 95% CI = 1.48, 2.09; P = 0.0001), and TLR6 rs5743810 (745T, OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.38, 2.00; P = 0.0002). However, after co-varying for self-identified race, no significant association was observed between these SNPs and HIV status at the α = 0.001 level (P = 0.017, 0.006, and 0.012, respectively).

Stratification of the data by self-identified race, and adjustment for sex, revealed that none of the 41 SNPs was significantly associated with HIV status at the α = 0.001 level in either racial group. However, considering significance at P < 0.05, a total of 9 SNPs in TLR1 (n = 2), TLR4 (n = 1), TLR6 (n = 4), and TLR8 (n = 2) were significantly associated with HIV status under an additive genetic model in Caucasians (Table 3). Of these, a total of 5 SNPs in TLR1 (n = 2), TLR4 (n = 1), and TLR6 (n = 2) were also significantly associated with HIV status under a dominant genetic model (Table 3). The 5 SNPs, showing significance in both genetic models, included 3 SNPs (rs5743551, rs5743618, and rs5743810) that were significantly associated with HIV status in the regression analysis performed on all samples combined. In contrast to Caucasians, only one SNP in TLR4 under both genetic models, and one SNP in TLR8 under the additive genetic model were significantly associated with HIV status at P < 0.05 in African Americans (Table 3). These 2 SNPs were not among the 9 SNPs that were significantly associated with HIV status in Caucasians.

Table 3.

Regression analysis of TLR SNPs

| Racial group | Gene | rs number | SNP | Amino acid | Allele | Test | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | TLR1 | rs5743551 | −7202G>A | - | G | Add | 2.69 | 1.31, 5.53 | 0.007 |

| rs5743618 | 1805G>T | Ser602Ile | T | 2.51 | 1.29, 4.88 | 0.007 | |||

| TLR4 | rs10759932 | −1607T>C | - | C | 4.03 | 1.4, 11.59 | 0.010 | ||

| TLR6 | rs5743806 | −673C>T | - | C | 2.09 | 1.03, 4.23 | 0.040 | ||

| rs1039559 | −502T>C | - | C | 0.41 | 0.22, 0.79 | 0.007 | |||

| rs5743810 | 745T>C | Ser249Pro | T | 0.45 | 0.24, 0.83 | 0.010 | |||

| rs3775073 | 1263A>G | Lys421Lys | G | 2.05 | 1.02, 4.09 | 0.043 | |||

| TLR8 | rs3764880 | 1A>G | Met1Val | G | 3.01 | 1.16, 7.83 | 0.024 | ||

| rs2407992 | 1953G>C | Leu651Leu | C | 2.43 | 1.1, 5.36 | 0.028 | |||

| TLR1 | rs5743551 | −7202G>A | - | G | Dom | 2.75 | 1.11, 6.82 | 0.028 | |

| rs5743618 | 1805G>T | Ser602Ile | T | 2.52 | 1.05, 6.1 | 0.040 | |||

| TLR4 | rs10759932 | −1607T>C | - | C | 4.23 | 1.31, 13.68 | 0.016 | ||

| TLR6 | rs1039559 | −502T>C | - | C | 0.31 | 0.11, 0.88 | 0.028 | ||

| rs5743810 | 745T>C | Ser249Pro | T | 0.28 | 0.11, 0.73 | 0.010 | |||

| African American | TLR4 | rs7873784 | +12186C>G | - | C | Add | 2.37 | 1.16, 4.84 | 0.018 |

| TLR8 | rs2159377 | 354C>T | Asp118Asp | T | 0.39 | 0.16, 0.92 | 0.031 | ||

| TLR4 | rs7873784 | +12186C>G | - | C | Dom | 2.31 | 1.06, 5.01 | 0.035 |

Abbreviations: Add, additive genetic model; Dom, dominant genetic model; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

After adjusting for sex, we noticed that it was consistently a significant contributor to both genetic models, especially in Caucasians (P-values < 0.001, data not shown). However, the significance of sex as a covariate could be attributed to the uneven distribution of sex between HIV+ and HIV− subjects (Table 1).

Haplotype analysis for genes and heterodimers by HIV status

Significant global P-values were observed for the TLR1 and TLR4 genes, and for the TLR2_TLR6 heterodimer in Caucasians (P = 0.025, 0.032, and 0.017, respectively; Table 4). This indicates significant differences in the overall haplotype profiles of TLR1, TLR4, and TLR2_TLR6 between HIV+ and HIV− Caucasians. Two haplotypes in TLR1, one haplotype in TLR4, and one haplotype in TLR2_TLR6 were significantly associated with HIV status (Table 4). The TLR1 haplotype GTGT was significantly more frequent in HIV+ patients (hap-score 2.198, P = 0.028), whereas the haplotype ATGG was significantly more frequent in HIV− donors (hap-score −3.313, P = 0.001). The TLR4 haplotype AGCACGG was significantly more frequent in HIV+ patients than in HIV− donors (hap-score 2.529, P = 0.011). The TLR2_TLR6 heterodimer haplotype TGTTG_GTCTCATC was significantly more frequent in HIV− donors than in HIV+ patients (hap-score −2.839, P = 0.005). In contrast to Caucasians, no haplotype, either in genes or in heterodimers, was significantly associated with HIV status in African Americans.

Table 4.

Haplotype analysis of TLR SNPs by HIV status in Caucasians

| Haplotype†‡ | Hap-Freq (total) | Hap-Freq HIV+ | Hap-Freq HIV− | Hap-score | P-value Global | P-value Haplotype-specific |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1 | 0.025 | |||||

| GTGT | 0.093 | 0.157 | 0.021 | 2.198 | 0.028 | |

| ATGG | 0.575 | 0.467 | 0.698 | −3.313 | 0.001 | |

| TLR4 | 0.032 | |||||

| AGCACGG | 0.098 | 0.146 | 0.042 | 2.529 | 0.011 | |

| TLR2_TLR6 | 0.017 | |||||

| TGTTG_GTCTCATC | 0.139 | 0.080 | 0.206 | −2.839 | 0.005 |

Abbreviations: Hap-Freq, haplotype frequency; Hap-score, haplotype score.

Nucleotide positions are in the same order as described in Table 2.

All haplotypes of TLR1, TLR4, and TLR2_TLR6 are presented in Supplementary Table C.

The SNPs presented in Table 3 are shown in bold.

Summary

For further clarity, we provide summary of all results, arranged according to significant TLR SNPs and haplotypes, as Supplementary Results.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, utilizing samples from North American HIV+ and HIV− subjects, we provide evidence indicating that a total of 9 SNPs in TLR1, TLR4, TLR6, and TLR8 in Caucasians, and one SNP each in TLR4 and TLR8 in African Americans have potential roles in susceptibility to or protection against HIV infection. Although expressed on the cell surface, TLR1, TLR4, and TLR6 have been shown to be involved in responses to viral infection,14 including HIV (TLR4).18–22, 24

TLR1 SNPs and HIV

There is a paucity of information about the role of TLR1 in HIV/AIDS. In a Kenyan cohort of untreated women, the mRNA expression of TLR1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was equivalent between HIV-infected and uninfected subjects.20 In a North American, predominantly male cohort, where a majority of the patients were treated, the TLR1 surface expression level was diminished on monocytes and myeloid dendritic cells from HIV-infected persons compared with the expression on cells from control donors.17 To date, no genetic study, analyzing the role of TLR polymorphisms in influencing HIV infection and/or disease progression, has included TLR1 SNPs.28–35

The mechanisms by which the −7202G and 1805T alleles influence HIV status is currently unknown. These 2 alleles were functionally significant in sepsis,43, 44 tuberculosis,37 leprosy,39 and candidemia,40 where they were associated with higher NF-kB activation and signaling, and elevated inflammatory cytokine production, including that of IL-6.37, 40, 44 Elevated levels of IL-6 have been associated with HIV infection60 and could contribute to HIV disease progression.61 Using a human monocytic cell line, THP-1, it has been shown that glycoprotein (gp) 41 is the primary HIV-encoded protein involved in inducing IL-6 production.62 However, in the clinical studies, there was weak or no correlation between plasma levels of IL-6 and HIV-1 RNA, but IL-6 levels were correlated with plasma levels of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) co-receptor CD14.63 Furthermore, macrophages stimulated with LPS or flagellin showed robust production of IL-6, but there was no increase in IL-6 production after HIV-1 infection.63 Regardless of whether IL-6 production is driven by an HIV molecule (gp41) or HIV-associated bacterial products (LPS/flagellin), our finding that TLR1 SNPs and haplotypes are associated with HIV status in Caucasians is noteworthy, and may be considered as a starting point in identifying the contribution of TLR1 genetic variation to HIV infection and disease progression.

TLR4 SNPs and HIV

TLR4 has an important role in HIV/AIDS. The expression of TLR4 in PBMC subpopulations19, 20, 24 and dendritic cells18 from untreated HIV-infected patients is upregulated, whereas in PBMCs from chronic patients failing therapy it is reduced.22 However, the information regarding the role of TLR4 SNPs in influencing HIV infection and/or disease progression is mixed. In a treatment-naïve, predominantly white North American cohort, SNPs Asp299Gly (rs4986790) and Thr399Ile (rs4986791) were associated with high peak plasma viral load.31 On the other hand, in Swiss,29 Spanish,32 and Kenyan cohorts,28, 30 these and other TLR4 SNPs were not associated with HIV infection and/or disease progression. In the present study, we did not find an association between Asp299Gly/Thr399Ile, considered singly or in haplotypes, and HIV status in either racial group. Most of the aforementioned studies28–30, 32 did not include −1607T>C and +12186C>G. The study31 that included these SNPs did not find an association with peak plasma viral load or disease progression.

The information regarding the functional significance of −1607T>C and +12186C>G is limited.50, 64–66 The −1607C allele may be a risk factor for prostate cancer47 and traffic-related air pollution-associated childhood asthma,51 and the +12186C allele may be a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis.56 However, none of these studies looked into the possible mechanisms of these allelic associations. In female genital epithelial cells, TLR4 binds to HIV-1 gp120 and triggers pro-inflammatory cytokine production via activation of NF-kB.21 Being located in the promoter and 3′-untranslated (UTR) regions, respectively, it is plausible that these SNPs affect TLR4 activity via affecting gene expression and mRNA stability. Therefore, further functional and clinical studies are needed to determine whether these SNPs influence HIV-associated TLR4-mediated activation of NF-kB and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Alternatively, it may be that these SNPs affect responsiveness to LPS, as has been shown with other TLR4 SNPs (Asp299Gly and Thr399Ile),67 and thus influence HIV-associated systemic immune activation and pathogenesis.

TLR6 SNPs and HIV

TLR6 seems to play an important role in HIV/AIDS.20 In a Kenyan cohort of untreated women, the mRNA expression of TLR6 was significantly increased in PBMCs from HIV-infected subjects compared with those from uninfected subjects, and the expression level of TLR6 was positively correlated with the plasma viral load.20 However, the role of TLR6 SNPs in influencing HIV infection and/or disease progression has not yet been identified,28–35 as is the case for TLR1 SNPs.

Despite the fact that the chromosomal regions containing TLR6 (TLR1_TLR6_TLR2 and TLR10_TLR1_TLR6) have been implicated in a variety of diseases, including infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis,8, 36 most of the information regarding the functional significance of TLR6 SNPs is limited to non-synonymous 745T>C, which is in strong LD with a promoter SNP −502T>C. In tuberculosis studies,41, 42 the 745T allele, compared with the 745C allele, was associated with lower NF-kB signaling, lower levels of IL-6, and higher levels of IFN-γ. Association of this allele with a decreased NF-kB activation and IL-6 production, but no effect on IL-10 production, may also play a role in protection against coronary artery disease.48 IFN-γ plays various roles in HIV/AIDS pathogenesis, including controlling HIV-1 replication.68, 69 Thus, it is plausible that the observed protective effect of the 745T allele in our study, 55–72% decrease in OR, is due to regulation of the IFN-γ IL-6 cytokine profile. Clinical studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis. On the other hand, the information regarding the functional significance of −673C>T70 and 1263A>G44 is scarce.

TLR8 SNPs and HIV

A number of studies have shown an important role of TLR8 (TLR7/8) in HIV/AIDS.20, 25–27 It may be summarized from these studies that the mRNA expression of TLR8 is significantly increased in HIV-infected subjects; HIV ssRNA upregulates TLR8 expression; and stimulation of TLR8 (TLR7/8) affects HIV pathogenesis, which depends on the stage of infection as well as the cell type examined. Given the significance of TLR8 in HIV/AIDS, the role of TLR8 SNPs, including 1A>G, in influencing HIV infection and/or disease progression has been explored.28–30, 34 The 1G allele displayed impaired NF-kB activation in vitro, and was associated with modulation of cytokine induction (higher TNF-α and lower IL-10) in monocytes.34 The allele was significantly associated with reduced disease progression in a Caucasian German34 and a Kenyan cohort.30 However, among Kenyan female infants, the 1G allele was significantly associated with higher peak plasma viral load.28 No significant association was observed between TLR8 SNPs, including 1A>G, 1953G>C, and 354C>T, and disease progression in a Swiss cohort.29 Thus, these studies, together with our finding that the 1G allele was significantly associated with HIV status in Caucasian Americans, suggest that the association between the allele and HIV infection/disease progression may be population- and/or outcome measure-specific.

Among the abovementioned studies, except one,29 most28, 30, 34 did not include 1953G>C and 354C>T. Both 1953G38, 54 and 1953C55 alleles may be associated with respiratory infections and diseases. No reference to the possible mechanisms of these allelic associations was made in these studies. To our knowledge, no report is available regarding the functional significance of 354C>T. Also, it does not appear that the SNP is in high LD with any other SNP in TLR8, or with any SNP in TLR7.54 Given that 354C>T had a protective effect in African Americans, and that HIV/AIDS continues to disproportionately affect this population,71 evaluating the functional and clinical effects of this SNP in further studies is important and highly relevant.

Limitations

We acknowledge that our study has some limitations. First, the SNPs in TLR1, TLR4, TLR6 and TLR8 were not significantly associated with HIV status at the multiple testing correction level of 0.001, but at P < 0.05 (Table 3). It is possible that the uneven distribution of HIV+ (n = 180) and HIV− (n = 96) subjects overall as well as within African Americans (HIV+, n = 102; HIV−, n = 48) partly contributed to the lower levels of significance. In our power analysis using CaTS,72 we had sufficient power to detect a minor allele with OR of 2.0 to 3.0, but we were underpowered to detect a minor allele with an OR of <2.0 (Supplementary Table D). Nevertheless, it is important to note that our findings pertaining to ORs were concordant with significant differences in the SNP allele frequencies between HIV+ and HIV− subjects (Table 2) and, in Caucasians, with our haplotype analyses, by which certain haplotypes may be inferred as “susceptible” or “protective” (Table 4).

Second, the race of our HIV+ and HIV− populations is self-identified. Studies investigating the association between genetic markers and HIV/AIDS outcomes have heavily relied upon self-identified race classification. Only recently have researchers begun to consider genetic ancestry into their analyses, showing that the self-identified race and genetic ancestry could be poorly73, 74 or highly75 concordant. In addition, our HIV+ and HIV− population samples were collected at locations in the Midwest (East North Central) and South (South-Atlantic) regions of the United States, respectively, with a distance of approximately 400 miles. We did notice a higher overall extent of LD in HIV− donors than in HIV+ patients, despite their racial status (Supplementary Table B), which may be due to differences in demographic factors. In the continental United States, the African ancestry contribution to Caucasian populations is 1–2%, whereas the European ancestry contribution to African-American populations varies substantially (3% to >30%).76 However, these 2 regions are similar regarding the European ancestry contribution to African-American populations (16–20% and 13–19%, respectively).76 These estimates were obtained using especially selected ancestry informative markers and are quite precise.76 We also quantified admixture in the HIV+ and HIV− African-American groups by using the Duffy blood group antigen (FY) as a population-specific marker. Among the 3 most common FY alleles, FY*A, FY*B, and FY*BES (erythroid silent), FY*BES is a key marker for African ancestry.77, 78 Furthermore, the unique utility of this marker is reflected in the fact that the allele frequencies of this marker match the African-American admixture proportions estimated using a number of autosomal markers.77 Frequency of the FY*BES allele was 0.72 (FY*A, 0.14; FY*B, 0.14) among the HIV+ African-American group, and 0.73 (FY*A, 0.12; FY*B, 0.15) among the HIV− African-American group, indicating that the admixture proportions at this genetic locus were highly similar between the 2 groups.

Third, we adjusted for self-identified race and sex in our regression analyses. We cannot exclude the fact that residual confounding may exist due to unmeasured ethnic factors (environmental, social, cultural, or behavioral). This information is not available for HIV− donors, and therefore the impact of any other potential confounder could not be considered in the study. In addition, no information is available regarding HIV exposure in HIV− donors. However, a number of studies have reported the prevalence, incidence, and residual risk of HIV in blood donor populations from the American Red Cross,79–82 which is the source of our HIV− donor samples. These data indicate that random blood donors cannot be considered to be HIV unexposed.

Finally, to our knowledge, among the studies that have evaluated the influence of genetic variation in TLRs on HIV/AIDS outcomes, ours is the only other study conducted in North America. A previous study was conducted in a different, predominantly white cohort.31 Most of the other studies were conducted in Europe,29, 32–35 and a few in Africa.28, 30 Because the data regarding TLR variants and HIV infection/disease in admixed populations are still scarce, caution is recommended in the interpretation and comparison of our study findings. Unique findings of our study are the potential roles of TLR1 and TLR6 SNPs in influencing HIV status. On the other hand, we did not find a role of TLR9 1635G>A (rs352140, Pro545Pro), which has been found significantly associated with HIV/AIDS outcomes in many studies.28–32, 35 A number of factors, including a different outcome measure, could account for this difference.

Conclusions

Our study provides in-depth insight into the influence of genetic variation in TLRs on HIV status in North American subjects. To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate the association between SNPs in TLR1 and TLR6 and an HIV-related outcome. We found that SNPs in TLR1, TLR4, TLR6 and TLR8 are associated with HIV status, and these associations appear to be race-specific. We also identified haplotypes of TLR1 and TLR4, which may be inferred as “susceptible” or “protective” haplotypes. Furthermore, by performing heterodimer haplotype-based analysis, we found that a TLR2_TLR6 haplotype may be “protective”. The mechanisms by which the aforementioned TLR SNPs, singly or in haplotypes, influence HIV status need to be further elucidated. Analysis of mRNA and protein levels of the TLR variants, and investigation of interactions of the variant TLRs with adaptor molecules and subsequent recruitment of downstream targets are needed to define the biological mechanisms that underlie the influence of genetic variation in TLRs on HIV status, infection dynamics, and disease progression.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study populations

A total of 280 subjects were analyzed in this study. Among these, 184 were adults with confirmed HIV infection (HIV+), receiving care at the Special Immunology Unit of Case Western Reserve University/University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, OH. De-identified packed blood pellets, collected from these patients, were obtained from the Case Western Reserve University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) specimen repository. All patients provided written informed consent for de-identified clinical data and specimen collection, storage, and usage in genetic and non-genetic studies. The data and specimen collection protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Hospitals Case Medical Center. Additionally, 96 de-identified samples, collected from healthy, adult North American random blood donors (HIV−), were obtained from American Red Cross National Histocompatibility Laboratory, University of Maryland Medical System, Baltimore, MD.78 Blood samples from these de-identified donors were collected under protocols, including the procedures for informed consent, approved by the respective institutional review boards.

TLR SNPs

A total of 45 SNPs in 8 TLR genes (TLR1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9), which have been evaluated in HIV/AIDS28–35 and other infectious36–45 as well as inflammatory and immune-mediated non-infectious46–56 diseases, were included in the present study. These SNPs were located in promoter regions, 5′-UTRs, exons, introns, and 3′-UTRs (Supplementary Table A). In HIV/AIDS studies, most of these SNPs were selected from the dbSNP, Innate Immunity Programs for Genomic Applications, and Genome Variation Server (University of Washington) databases,28, 29, 31 using haplotype tagging28, 29, 31 and candidate SNP28, 31 approaches. Similar strategies, together with prediction of functionality using in vitro transfection assays and/or bioinformatics tools,48, 50, 53, 54, 64, 65 were used in other studies.

Genotyping of SNPs

DNA was extracted from 200 μl of packed blood pellets from HIV+ patients and whole-blood samples from HIV− donors using the QIAamp 96 spin blood kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). DNA concentrations were measured using Qubit® Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). SNPs were genotyped using Illumina’s GoldenGate® genotyping assay system combined with VeraCode® Technology (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). Allelic discrimination was performed using a BeadXpress® Reader (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The genotype data were uploaded and filtered using the GenomeStudio data analysis software v2011.1 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). SNPs were filtered by genotype call frequency (<0.9, n = 1) and replicate errors (n = 2). Samples with genotype call frequency <0.9 were excluded (n = 4). Subsequently, SNPs were excluded from analysis if genotypic distribution among HIV− donors, stratified by race, deviated from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) with a significant cutoff value of P ≤ 0.001 (n = 1). Thus, in the final analysis, 41 SNPs, as listed in Supplementary Table A, were examined in a total of 276 subjects (HIV+, n = 180; HIV−, n = 96).

Genotyping of Duffy (FY) blood group antigen

In order to quantitatively measure admixture in our African American groups, FY genotyping (−46T>C, 625G>A [Gly44Asp]) was performed as previously described.78

Statistical analysis

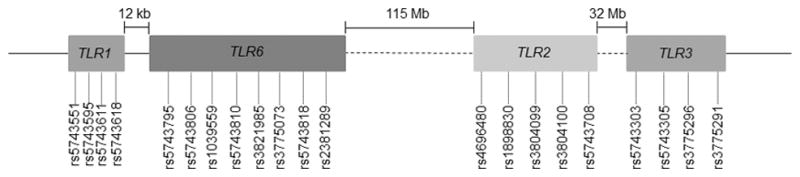

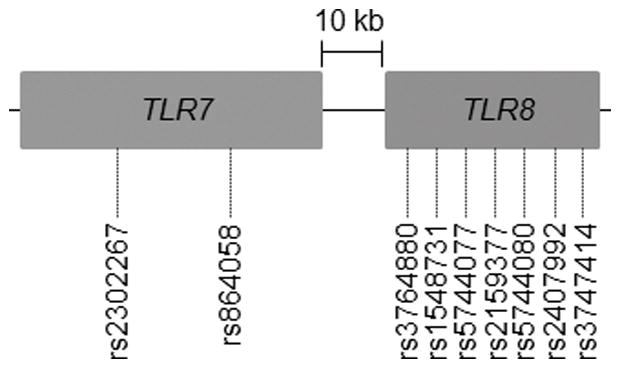

Minor allele frequency, potential batch effect, and HWE were calculated using PLINK v1.07.83 An online 2 × 2 contingency table for Fisher’s exact test [http://www.langsrud.com/fisher.htm] was used to calculate differences in allele frequencies between populations, and a 2-tailed P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Samples from HIV+ patients (n = 180) were analyzed on 2 plates. Potential batch effect was assessed by comparing allele frequencies from the 2 plates using a t-test.84 Pairwise LD between SNPs of a gene or 2 genes that are nearby (TLR1 and TLR6 [12 kb], and TLR7 and TLR8 [10 kb]) (Figure 1A and 1B) was determined for both HIV+ and HIV− Caucasians and African Americans using SHEsis.85 Strong LD was defined by high values for both D′ (≥0.8) and r2 (≥0.5) parameters.58

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of the location of the TLR genes and SNPs therein on (A) chromosome 4 and (B) chromosome X.

Logistic regression analysis was performed on all 41 SNPs using PLINK v1.07.83 Initially, all subjects were included in a single analysis, without adjusting for race or sex. A second regression analysis adjusted for race within the regression equation. Finally, the data were stratified by race, analyzing Caucasians and African Americans separately, and adjustment for sex was made in both analyses. SNPs were coded under an additive genetic model, and then under a dominant genetic model, except those in TLR7 and TLR8, located on chromosome X. Under the additive model, subjects having 2, 1, or 0 copy of the minor allele were coded as a 2, 1, and 0, respectively. Under the dominant model, subjects having 2 or 1 copy of the minor allele were coded as a 1, whereas those with 0 copy of the minor allele were coded as a 0.

Multiple testing correction for all regression analyses was determined by using SNPSpDlite.59 SNPSpDlite calculates a multiple testing correction for SNPs that are in LD with one another, by calculating the LD correlation matrix for given SNPs, then estimating the number of independent tests within the sample. This is an alternative to the more conservative Bonferroni correction, which assumes all tests are independent. Thus, the significance threshold, α, for all SNP association tests was 0.001 (effective number of independent tests = 35). The additive and dominant models were tested separately, with the same significance threshold (0.001) applied to both sets of results.

Single locus and multilocus, whose products jointly form heterodimers (TLR1_TLR2 and TLR2_TLR6), haplotype analyses were performed using the haplo.stats package v1.2.2. for R. Haplotype scores (hap-score)86 were calculated using haplo.score within the haplo.stats package and were used to test the association between haplotypes and HIV status. Haplotype scores cannot be used as a means of interpreting the measure of the haplotype effect, but simply as an indicator of the strength of the association between the haplotype and the outcome of interest.86 A positive hap-score indicates that the haplotype occurs more frequently in case subjects, whereas a negative hap-score indicates that the haplotype occurs more frequently in control subjects.86–88 The analysis output includes both gene-specific (global) and haplotype-specific P-values, which were considered significant if < 0.05. A global P-value < 0.05 was inferred as a significant difference in an overall haplotype profile of a gene/heterodimer between HIV+ and HIV− subjects. If the global P-value was significant, only then were the haplotype-specific P-values considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (1P01DE019759, A.W.; Project 4, R.J.J. and P.A.Z.), Fogarty International Center (D43TW007377, support for B.W.), and National Heart Lung and Blood Institutes (T32HL007567, support for N.B.H.) at the National Institutes of Health. We are indebted to Drs. Michael Lederman and Benigno Rodriguez for providing the HIV-infected patient samples from the CFAR specimen repository. We are thankful to Simone Edelheit and Milena Rajak (Genomics Core Facility) for performing the TLR SNP genotyping, and to Melinda Zikursh for performing the Duffy genotyping. We sincerely thank Dr. Daniel Tisch, Dave McNamara, Dr. Scott Sieg, and Ramalakshmi Janamanchi for helpful discussions and critical evaluation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Walker BD, Yu XG. Unravelling the mechanisms of durable control of HIV-1. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:487–498. doi: 10.1038/nri3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Manen D, van’t Wout AB, Schuitemaker H. Genome-wide association studies on HIV susceptibility, pathogenesis and pharmacogenomics. Retrovirology. 2012;9:70. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin MP, Carrington M. Immunogenetics of HIV disease. Immunol Rev. 2013;254:245–264. doi: 10.1111/imr.12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelak K, Need AC, Fellay J, Shianna KV, Feng S, Urban TJ, et al. Copy number variation of KIR genes influences HIV-1 control. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehlotra RK, Dazard JE, John B, Zimmerman PA, Weinberg A, Jurevic RJ. Copy number variation within human β-defensin gene cluster influences progression to AIDS in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J AIDS Clin Res. 2012;3:184. doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehlotra RK, Zimmerman PA, Weinberg A, Jurevic RJ. Variation in human β-defensin genes: new insights from a multi-population study. Int J Immunogenet. 2013;40:261–269. doi: 10.1111/iji.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sobieszczyk ME, Lingappa JR, McElrath MJ. Host genetic polymorphisms associated with innate immune factors and HIV-1. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:427–434. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283497155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barreiro LB, Ben-Ali M, Quach H, Laval G, Patin E, Pickrell JK, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of human Toll-like receptors and their different contributions to host defense. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferwerda B, McCall MB, Alonso S, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Mouktaroudi M, Izagirre N, et al. TLR4 polymorphisms, infectious diseases, and evolutionary pressure during migration of modern humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16645–16650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704828104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Misch EA, Hawn TR. Toll-like receptor polymorphisms and susceptibility to human disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;114:347–360. doi: 10.1042/CS20070214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter S, O’Neill LA. Recent insights into the structure of Toll-like receptors and post-translational modifications of their associated signalling proteins. Biochem J. 2009;422:1–10. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blasius AL, Beutler B. Intracellular toll-like receptors. Immunity. 2010;32:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carty M, Bowie AG. Recent insights into the role of Toll-like receptors in viral infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;161:397–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manavalan B, Basith S, Choi S. Similar structures but different roles - an updated perspective on TLR structures. Front Physiol. 2011;2:41. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart CR, Stuart LM, Wilkinson K, van Gils JM, Deng J, Halle A, et al. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:155–161. doi: 10.1038/ni.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funderburg NT, Sieg SF. Diminished responsiveness to human β-defensin-3 and decreased TLR1 expression on monocytes and mDCs from HIV-1-infected patients. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:1103–1109. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1111555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez JC, Arteaga J, Paul S, Kumar A, Latz E, Urcuqui-Inchima S. Up-regulation of TLR2 and TLR4 in dendritic cells in response to HIV type 1 and coinfection with opportunistic pathogens. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011;27:1099–1109. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernandez JC, Stevenson M, Latz E, Urcuqui-Inchima S. HIV type 1 infection up-regulates TLR2 and TLR4 expression and function in vivo and in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28:1313–1328. doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lester RT, Yao XD, Ball TB, McKinnon LR, Kaul R, Wachihi C, et al. Toll-like receptor expression and responsiveness are increased in viraemic HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2008;22:685–694. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4de35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nazli A, Kafka JK, Ferreira VH, Anipindi V, Mueller K, Osborne BJ, et al. HIV-1 gp120 induces TLR2- and TLR4-mediated innate immune activation in human female genital epithelium. J Immunol. 2013;191:4246–4258. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scagnolari C, Selvaggi C, Chiavuzzo L, Carbone T, Zaffiri L, d’Ettorre G, et al. Expression levels of TLRs involved in viral recognition in PBMCs from HIV-1-infected patients failing antiretroviral therapy. Intervirology. 2009;52:107–114. doi: 10.1159/000218082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Y, Wang X, Liu M, Hu Q, Song L, Ye L, et al. A critical function of toll-like receptor-3 in the induction of anti-human immunodeficiency virus activities in macrophages. Immunology. 2010;131:40–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller Sanders C, Cruse JM, Lewis RE. Toll-like receptor and chemokine receptor expression in HIV-infected T lymphocyte subsets. Exp Mol Pathol. 2010;88:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang JJ, Lacas A, Lindsay RJ, Doyle EH, Axten KL, Pereyra F, et al. Differential regulation of toll-like receptor pathways in acute and chronic HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2012;26:533–541. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834f3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlaepfer E, Audige A, Joller H, Speck RF. TLR7/8 triggering exerts opposing effects in acute versus latent HIV infection. J Immunol. 2006;176:2888–2895. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlaepfer E, Speck RF. TLR8 activates HIV from latently infected cells of myeloid-monocytic origin directly via the MAPK pathway and from latently infected CD4+ T cells indirectly via TNF-α. J Immunol. 2011;186:4314–4324. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beima-Sofie KM, Bigham AW, Lingappa JR, Wamalwa D, Mackelprang RD, Bamshad MJ, et al. Toll-like receptor variants are associated with infant HIV-1 acquisition and peak plasma HIV-1 RNA level. AIDS. 2013;27:2431–2439. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283629117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bochud PY, Hersberger M, Taffe P, Bochud M, Stein CM, Rodrigues SD, et al. Polymorphisms in Toll-like receptor 9 influence the clinical course of HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2007;21:441–446. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328012b8ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackelprang RD, Bigham AW, Celum C, de Bruyn G, Beima-Sofie K, John-Stewart G, et al. Toll-like receptor polymorphism associations with HIV-1 outcomes among sub-Saharan Africans. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1623–1627. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pine SO, McElrath MJ, Bochud PY. Polymorphisms in toll-like receptor 4 and toll-like receptor 9 influence viral load in a seroincident cohort of HIV-1-infected individuals. AIDS. 2009;23:2387–2395. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330b489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soriano-Sarabia N, Vallejo A, Ramirez-Lorca R, del Rodriguez MM, Salinas A, Pulido I, et al. Influence of the Toll-like receptor 9 1635A/G polymorphism on the CD4 count, HIV viral load, and clinical progression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:128–135. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318184fb41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh DY, Baumann K, Hamouda O, Eckert JK, Neumann K, Kucherer C, et al. A frequent functional toll-like receptor 7 polymorphism is associated with accelerated HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS. 2009;23:297–307. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831fb540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh DY, Taube S, Hamouda O, Kucherer C, Poggensee G, Jessen H, et al. A functional toll-like receptor 8 variant is associated with HIV disease restriction. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:701–709. doi: 10.1086/590431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ricci E, Malacrida S, Zanchetta M, Mosconi I, Montagna M, Giaquinto C, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 polymorphisms influence mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Transl Med. 2010;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ben-Ali M, Corre B, Manry J, Barreiro LB, Quach H, Boniotto M, et al. Functional characterization of naturally occurring genetic variants in the human TLR1–2–6 gene family. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:643–652. doi: 10.1002/humu.21486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hawn TR, Misch EA, Dunstan SJ, Thwaites GE, Lan NT, Quy HT, et al. A common human TLR1 polymorphism regulates the innate immune response to lipopeptides. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2280–2289. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janssen R, Bont L, Siezen CL, Hodemaekers HM, Ermers MJ, Doornbos G, et al. Genetic susceptibility to respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis is predominantly associated with innate immune genes. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:826–834. doi: 10.1086/520886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson CM, Lyle EA, Omueti KO, Stepensky VA, Yegin O, Alpsoy E, et al. Cutting edge: A common polymorphism impairs cell surface trafficking and functional responses of TLR1 but protects against leprosy. J Immunol. 2007;178:7520–7524. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plantinga TS, Johnson MD, Scott WK, van de Vosse E, Velez Edwards DR, Smith PB, et al. Toll-like receptor 1 polymorphisms increase susceptibility to candidemia. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:934–943. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Randhawa AK, Shey MS, Keyser A, Peixoto B, Wells RD, de Kock M, et al. Association of human TLR1 and TLR6 deficiency with altered immune responses to BCG vaccination in South African infants. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002174. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shey MS, Randhawa AK, Bowmaker M, Smith E, Scriba TJ, de Kock M, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in toll-like receptor 6 are associated with altered lipopeptide- and mycobacteria-induced interleukin-6 secretion. Genes Immun. 2010;11:561–572. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson CM, Holden TD, Rona G, Laxmanan B, Black RA, O’Keefe GE, et al. Toll-like receptor 1 polymorphisms and associated outcomes in sepsis after traumatic injury: a candidate gene association study. Ann Surg. 2014;259:179–185. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828538e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wurfel MM, Gordon AC, Holden TD, Radella F, Strout J, Kajikawa O, et al. Toll-like receptor 1 polymorphisms affect innate immune responses and outcomes in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:710–720. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-462OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor BD, Darville T, Ferrell RE, Ness RB, Haggerty CL. Racial variation in toll-like receptor variants among women with pelvic inflammatory disease. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:940–946. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen YC, Giovannucci E, Lazarus R, Kraft P, Ketkar S, Hunter DJ. Sequence variants of Toll-like receptor 4 and susceptibility to prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11771–11778. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng I, Plummer SJ, Casey G, Witte JS. Toll-like receptor 4 genetic variation and advanced prostate cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:352–355. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamann L, Koch A, Sur S, Hoefer N, Glaeser C, Schulz S, et al. Association of a common TLR-6 polymorphism with coronary artery disease - implications for healthy ageing? Immunity & Ageing. 2013;10:43. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-10-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang H, Wu J, Jin G, Zhang H, Ding Y, Hua Z, et al. A 5′-flanking region polymorphism in toll-like receptor 4 is associated with gastric cancer in a Chinese population. J Biomed Res. 2010;24:100–106. doi: 10.1016/S1674-8301(10)60017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hwang YH, Ro H, Choi I, Kim H, Oh KH, Hwang JI, et al. Impact of polymorphisms of TLR4/CD14 and TLR3 on acute rejection in kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:699–705. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b2f34a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kerkhof M, Postma DS, Brunekreef B, Reijmerink NE, Wijga AH, de Jongste JC, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 genes influence susceptibility to adverse effects of traffic-related air pollution on childhood asthma. Thorax. 2010;65:690–697. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.119636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kesh S, Mensah NY, Peterlongo P, Jaffe D, Hsu K, MVDB, et al. TLR1 and TLR6 polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1062:95–103. doi: 10.1196/annals.1358.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kormann MS, Depner M, Hartl D, Klopp N, Illig T, Adamski J, et al. Toll-like receptor heterodimer variants protect from childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moller-Larsen S, Nyegaard M, Haagerup A, Vestbo J, Kruse TA, Borglum AD. Association analysis identifies TLR7 and TLR8 as novel risk genes in asthma and related disorders. Thorax. 2008;63:1064–1069. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.094128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nilsson D, Andiappan AK, Hallden C, De Yun W, Sall T, Tim CF, et al. Toll-like receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with allergic rhinitis: a case control study. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang H, Wei C, Li Q, Shou T, Yang Y, Xiao C, et al. Association of TLR4 gene non-missense single nucleotide polymorphisms with rheumatoid arthritis in Chinese Han population. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:1283–1288. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2536-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferlin A, Ganz F, Pengo M, Selice R, Frigo AC, Foresta C. Association of testicular germ cell tumor with polymorphisms in estrogen receptor and steroid metabolism genes. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:17–25. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nyholt DR. A simple correction for multiple testing for single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:765–769. doi: 10.1086/383251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breen EC, Rezai AR, Nakajima K, Beall GN, Mitsuyasu RT, Hirano T, et al. Infection with HIV is associated with elevated IL-6 levels and production. J Immunol. 1990;144:480–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kalayjian RC, Machekano RN, Rizk N, Robbins GK, Gandhi RT, Rodriguez BA, et al. Pretreatment levels of soluble cellular receptors and interleukin-6 are associated with HIV disease progression in subjects treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1796–1805. doi: 10.1086/652750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takeshita S, Breen EC, Ivashchenko M, Nishanian PG, Kishimoto T, Vredevoe DL, et al. Induction of IL-6 and IL-10 production by recombinant HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein 41 (gp41) in the THP-1 human monocytic cell line. Cell Immunol. 1995;165:234–242. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shive CL, Biancotto A, Funderburg NT, Pilch-Cooper HA, Valdez H, Margolis L, et al. HIV-1 is not a major driver of increased plasma IL-6 levels in chronic HIV-1 disease. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:145–152. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825ddbbf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ragnarsdottir B, Jonsson K, Urbano A, Gronberg-Hernandez J, Lutay N, Tammi M, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 promoter polymorphisms: common TLR4 variants may protect against severe urinary tract infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Song C, Chen LZ, Zhang RH, Yu XJ, Zeng YX. Functional variant in the 3′-untranslated region of Toll-like receptor 4 is associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma risk. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1285–1291. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.10.3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zheng SL, Augustsson-Balter K, Chang B, Hedelin M, Li L, Adami HO, et al. Sequence variants of toll-like receptor 4 are associated with prostate cancer risk: results from the CAncer Prostate in Sweden Study. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2918–2922. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arbour NC, Lorenz E, Schutte BC, Zabner J, Kline JN, Jones M, et al. TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nat Genet. 2000;25:187–191. doi: 10.1038/76048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roff SR, Noon-Song EN, Yamamoto JK. The Significance of Interferon-gamma in HIV-1 Pathogenesis, Therapy, and Prophylaxis. Front Immunol. 2014;4:498. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vingert B, Benati D, Lambotte O, de Truchis P, Slama L, Jeannin P, et al. HIV controllers maintain a population of highly efficient Th1 effector cells in contrast to patients treated in the long term. J Virol. 2012;86:10661–10674. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00056-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun J, Wiklund F, Zheng SL, Chang B, Balter K, Li L, et al. Sequence variants in Toll-like receptor gene cluster (TLR6-TLR1-TLR10) and prostate cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:525–532. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Skol AD, Scott LJ, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M. Joint analysis is more efficient than replication-based analysis for two-stage genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:209–213. doi: 10.1038/ng1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frasco MA, Mack WJ, Van Den Berg D, Aouizerat BE, Anastos K, Cohen M, et al. Underlying genetic structure impacts the association between CYP2B6 polymorphisms and response to efavirenz and nevirapine. AIDS. 2012;26:2097–2106. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283593602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nicholaou MJ, Martinson JJ, Abraham AG, Brown TT, Hussain SK, Wolinsky SM, et al. HAART-associated dyslipidemia varies by biogeographical ancestry in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29:871–879. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheruvu VK, Igo RP, Jr, Jurevic RJ, Serre D, Zimmerman PA, Rodriguez B, et al. African ancestry influences CCR5 −2459G>A genotype-associated virologic success of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:102–107. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parra EJ. Admixture in North America. In: Suarez-Kurtz G, editor. Pharmacogenomics in Admixed Populations. Landes Bioscience; Austin: 2007. pp. 28–46. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Parra EJ, Marcini A, Akey J, Martinson J, Batzer MA, Cooper R, et al. Estimating African American admixture proportions by use of population-specific alleles. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1839–1851. doi: 10.1086/302148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zimmerman PA, Woolley I, Masinde GL, Miller SM, McNamara DT, Hazlett F, et al. Emergence of FY*A(null) in a Plasmodium vivax-endemic region of Papua New Guinea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13973–13977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Glynn SA, Kleinman SH, Schreiber GB, Busch MP, Wright DJ, Smith JW, et al. Trends in incidence and prevalence of major transfusion-transmissible viral infections in US blood donors, 1991 to 1996. Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study (REDS) JAMA. 2000;284:229–235. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zou S, Dorsey KA, Notari EP, Foster GA, Krysztof DE, Musavi F, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and residual risk of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infections among United States blood donors since the introduction of nucleic acid testing. Transfusion. 2010;50:1495–1504. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zou S, Notari EPt, Stramer SL, Wahab F, Musavi F, Dodd RY, et al. Patterns of age- and sex-specific prevalence of major blood-borne infections in United States blood donors, 1995 to 2002: American Red Cross blood donor study. Transfusion. 2004;44:1640–1647. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.04153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zou S, Stramer SL, Dodd RY. Donor testing and risk: current prevalence, incidence, and residual risk of transfusion-transmissible agents in US allogeneic donations. Transfus Med Rev. 2012;26:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pluzhnikov A, Below JE, Konkashbaev A, Tikhomirov A, Kistner-Griffin E, Roe CA, et al. Spoiling the whole bunch: quality control aimed at preserving the integrity of high-throughput genotyping. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shi YY, He L. SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci. Cell Res. 2005;15:97–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schaid DJ, Rowland CM, Tines DE, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Score tests for association between traits and haplotypes when linkage phase is ambiguous. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:425–434. doi: 10.1086/338688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bagwell AM, Bento JL, Mychaleckyj JC, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Bowden DW. Genetic analysis of HNF4A polymorphisms in Caucasian-American type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:1185–1190. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Goracy J, Goracy I, Kaczmarczyk M, Parczewski M, Brykczynski M, Clark J, et al. Low frequency haplotypes of E-selectin polymorphisms G2692A and C1901T give increased protection from coronary artery disease. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:CR334–340. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.