Abstract

Purpose

As the premiere modality for brain imaging, MRI could find wider applicability if lightweight, portable systems were available for siting in unconventional locations such as Intensive Care Units, physician offices, surgical suites, ambulances, emergency rooms, sports facilities, or rural healthcare sites.

Methods

We construct and validate a truly portable (<100kg) and silent proof-of-concept MRI scanner which replaces conventional gradient encoding with a rotating lightweight cryogen-free, low-field magnet. When rotated about the object, the inhomogeneous field pattern is used as a rotating Spatial Encoding Magnetic field (rSEM) to create generalized projections which encode the iteratively reconstructed 2D image. Multiple receive channels are used to disambiguate the non-bijective encoding field.

Results

The system is validated with experimental images of 2D test phantoms. Similar to other non-linear field encoding schemes, the spatial resolution is position dependent with blurring in the center, but is shown to be likely sufficient for many medical applications.

Conclusion

The presented MRI scanner demonstrates the potential for portability by simultaneously relaxing the magnet homogeneity criteria and eliminating the gradient coil. This new architecture and encoding scheme shows convincing proof of concept images that are expected to be further improved with refinement of the calibration and methodology.

Keywords: portable MRI, low-field MRI, nonlinear SEMs, Halbach magnet, parallel imaging

Introduction

Specialized, portable MRI systems have the potential to make MR neuroimaging possible at sites where it is currently unavailable and enable immediate, “point-of-care” detection and diagnosis of acute intracranial pathology which can be critical in patient management. For example, the characterization of acute post-traumatic space occupying brain hemorrhage is a time-sensitive emergency for which simple clinical assessment and even urgent CT scanning may be insufficient. While conventional MR scanners are capable of making this diagnosis, they are not available in remote locations. In Intensive Care Units scanners are generally nearby, but are difficult to utilize because of the dangers associated with transporting critical care patients. A portable bed-side scanner could offer major benefits in such situations. Portable, low-cost scanners are compelling for applications where power, siting and cost constraints prohibit conventional scanners. Examples include clinics in rural or underdeveloped areas, military field hospitals, sports arenas, and ambulances. Finally, analogous to the current use of ultra-sound, a low-cost and easy-to-implement scanner could find uses in neurology, neurosurgery or neuro-oncology examination rooms for routine disease monitoring (e.g. monitoring ventricle size after stent placement). The development of a portable scanner relies on the co-design of a new image encoding methods and simplified hardware. This approach is detailed in the present work.

Traditional Fourier MR imaging methods rely on homogeneous static polarizing fields (B0) and high strength linear Spatial Encoding Magnetic Fields (SEMs) produced by magnetic gradient coils. Conventional scanners utilize high cost superconducting wire, liquid cryogen cooling systems, and high power supplies and electronics. These aspects make it difficult to simply scale-down conventional MRI scanners to portable, low cost devices. Recently in (1) and (2), high resolution imaging has been achieved with table-top and small bore permanent magnet systems with long acquisition times (1), including a mobile MRI system developed for outdoor imaging of small tree branches (2), but these scanners lack a bore size suitable for brain imaging and the long acquisition times are not conducive to imaging in triage settings. Other approaches that scale-down the size of conventional systems for intra-operative MRI show promise (3). However, while these systems are relatively easy to retrofit in operating room, they are not truly portable.

In the present work, we use a novel image encoding method based on rotating spatial encoding magnetic fields (rSEM) to create a portable scanner. We replace the B0 magnet and linear gradient coils with a rotating permanent magnet featuring an inhomogeneous field pattern used for spatial encoding. In this scheme, the inhomogeneity in the B0 field serves as a spatial encoding magnetic field (SEM), and is requirement for image encoding not a nuisance. Loosening the homogeneity constraint of some conventional magnet designs leads to a reduction in the minimum required magnet material, and allows for more sparse/lightweight designs (45kg in our prototype). Additionally, the rotation of the magnet's inhomogeneous field pattern replaces the function of heavy switchable gradient coils with significant power requirements.

Several NMR devices for niche applications have explored relaxing the magnet homogeneity constraint, as well as reducing the reliance on traditional Fourier image encoding. The oil well-logging industry was the first to explore the idea of mobile NMR using “external sample” or “inside-out” NMR tools for measuring fluid in rock formations down-hole (4). This work was initially done with electromagnets or in the earth's field, but the advent of rare-earth magnets with high energy products such as SmCo and NdFeB (5), has allowed more effective borehole NMR tools to be developed (6). Some portable single-sided NMR devices (7,8) exploit inhomogeneous magnetic fields from permanent magnets for 1D spatial encoding. In these systems a rare-earth magnet array is placed against the object such that the field falls off roughly linearly with depth. Broadband excitation and spin-echo refocusing are used to obtain a 1D depth profile of the water content in the object (9–11). Thus, these systems use the inhomogeneity of the small magnet to spatially encode the depth of the water; a principle that we will exploit in a more complete way.

Previously, Cho et al. implemented a mechanically rotating DC gradient field in conjunction with a conventional MRI scanner with the motivation of silent imaging (12). In that case, the rotating electromagnet produced a linear gradient field so traditional projection reconstruction methods could be used. In the presently described portable scanner, the dominant SEM field term is quadrupolar, which requires specialized acquisition and reconstruction techniques. Spatial encoding with similar nonlinear fields created with electromagnets has recently drawn attention as a way to achieve focused high imaging resolutions, reduced peripheral nerve stimulation (13), and improved parallel imaging performance (14). In our scanner, the approximately quadrupolar SEM fields are physically rotated around the object along with the B0 field, and stationary RF coils are used to acquire generalized projections of the object in spin-echo train form.

In this manuscript, we describe the design, construction, and testing of a portable 2D MRI scanner. We show that the encoding scheme we introduce can achieve a resolution of a few millimeters in phantom images. While full 3D encoding is not demonstrated, the system is compatible with RF encoding schemes, such as the TRASE method (15,16), capable of adequately encoding the third dimension (along the axis of the cylindrical magnet). The magnet design and initial encoding attempts were previously reported in abstract form (17–19).

Methods

Magnet and field mapping

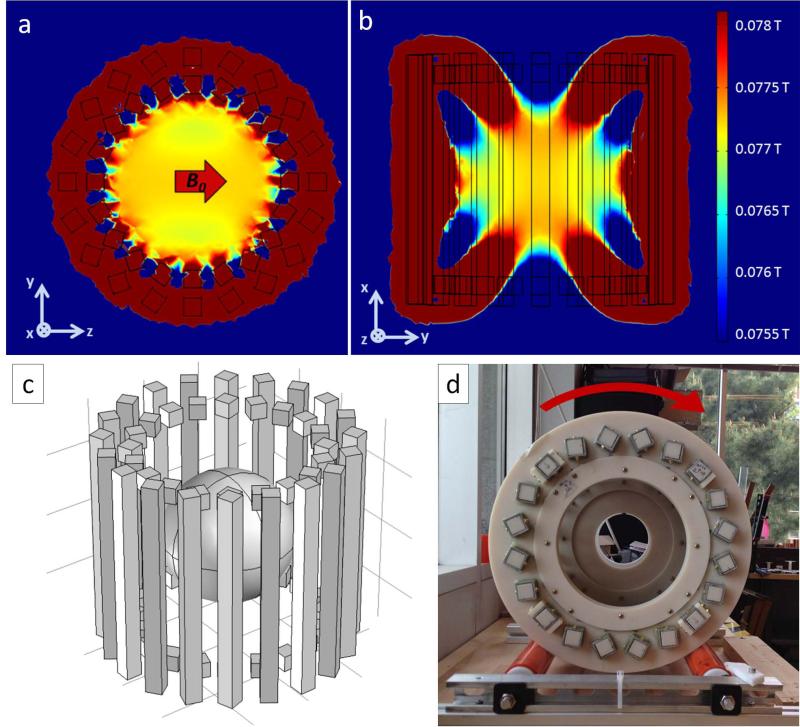

The described rSEM encoding method is valid for arbitrary encoding field shapes, although the shape will affect the spatially variable resolution of the images. A sparse dipolar Halbach cylinder design similar to the “NMR Mandhala” (20,21) was chosen to produce to the rotating B0 field presented here. This arrangement of permanent magnets produces an approximately uniform field directed transverse to the axis of the cylinder (22). The major design criteria for our Halbach magnet were: 1) maximum average field for highest SNR, 2) sufficient field variation for spatial encoding while maintaining reasonable measurement and excitation bandwidths, 3) minimum volume of permanent magnet material to keep cost and weight down, 4) use of stock rare-earth magnet material shapes, and 5) minimum size to fit the head (in order to maximize B0). Note, the design was not focused on the specific spatial encoding field shape, and the resulting pattern in the constructed magnet was accepted as the SEM for the presented scanner. The Halbach cylinder design consists of a 36 cm diameter array of 20 rungs comprising N42 grade NdFeB magnets that are each 1×1×14” (magnetized through the 1” thickness). Two additional Halbach rings made up of 20 1” NdFeB cubes are added to the ends of the cylinder to reduce field fall-off caused by the relatively short length of cylinder. Figure 1 shows a 3D drawing of the magnet, the simulated field, and constructed magnet.

Figure 1.

The magnet array consists of twenty 1”× 1”× 14” NdFeB magnets oriented in the k = 2 Halbach mode. Additional Halbach rings made of 1”× 1”× 1” magnets were added at the ends to reduce field fall off along the cylindrical axis. (A,B) Simulation of the magnetic field in two planes. The field is oriented transverse to the cylinder axis (z-direction). (C) Schematic of NdFeB magnets composing array. The targeted spherical imaging region (18 cm dia.) is depicted at isocenter. (D) End-view photo of the Halbach magnet mounted on high friction rollers. Magnet was constructed with ABS plastic and square fiberglass tubes containing the NdFeB magnets. Faraday cage not shown.

The predicted field pattern (Fig. 1a-b), as well as the forces between the magnet rungs were simulated using COMSOL Multiphysics (Stockholm, Sweden). This calculation estimated an internal force of 178 N, which is adequately handled by the fiberglass and ABS frame designed to hold the NdFeB magnet array. The magnet rungs consist of NdFeB magnets stacked inside square fiberglass tubes (McMaster-Carr, Elmhurst, Illinois USA), which are fixed by five water jet cut 3/8”ABS rings (Fig. 1d). Each 14” long magnet rung is comprised of four individual bar magnets (Applied Magnet, Plano, TX, USA) which were bonded together (three 4” bars and a 2” bar). The ABS/fiberglass frame was assembled prior to NdFeB magnet handling, and then the magnet rungs were populated one at a time. Since the 4 magnets comprising each rung repel each other as they are inserted, a magnet loading and pushing jig was necessary to force the magnets together while the magnet bonding adhesive cured (Loctite p/n 331 and 7387, Düsseldorf, Germany). The jig was a simple threaded rod mounted to the magnet assembly frame above the opening of the fiberglass tube.

The constructed magnet weighs 45 kg and has a 77.3 mT average field in the 16cm FOV center plane, corresponding to a 3.29 MHz proton Larmor frequency. The cylindrical magnet sits on aluminum rollers covered with a high friction urethane. The MRI console is used to drive a stepper motor (model 34Y106S-LW8, Anaheim Automation, Anaheim, CA, USA) that is attached to the aluminum axle of one of the rollers through a 5:1 gearbox (model GBPH-0901-NS-005, Anaheim Automation, Anaheim, CA, USA). Magnet rotation is incorporated into the pulse sequence so that it is controlled by the MRI console to a precision of one degree at a rate of 10 deg/s. Peripheral nerve stimulation is not a concern with this B0 rotation rate. Even at 10x the current rotation rate, the dB/dt from the rotating magnet is 2 orders of magnitude below the dB/dt generated by a modest clinical gradient system. The magnet assembly is enclosed in a copper mesh Faraday cage to reduce RF interference.

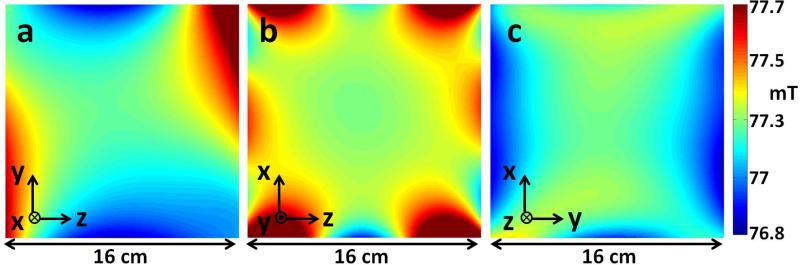

An initial 3D field map was obtained with a 3-axis gaussmeter probe attached to a motorized stage. The measured field shape is roughly quadrupolar, similar to the fields used in the initial realization of multipolar PatLoc (Parallel Imaging Technique using Localized Gradients) encoding (13), but with significant higher-order components as well. The measured field variation range in y-z (imaging plane), x-z, and x-y planes of a 16 cm sphere were Δfyz = 95 kHz, Δfxz = 60 kHz and Δfxy = 52 kHz. Large Larmor frequency bandwidths make it difficult to design RF excitation and refocusing pulses that achieve the same flip angle and phase across all the spins. In addition, it is difficult to make transmit and receive coils uniformly sensitive over the entire bandwidth. Therefore, shimming was done to decrease field variation (no attempt was made to reshape the SEM). The field variation was shimmed down to Δfyz = 32 kHz, Δfxz = 32.5 kHz and Δfxy = 19 kHz with the addition of small shim magnets (0.5” diameter, 0.25” length cylindrical NdFeB magnets) which were attached to the fiberglass rungs. The 3 planes of the shimmed field map are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Measured Larmor frequency maps of the spatial encoding magnetic field (SEM) in the z-y (imaging plane), z-x, and y-x planes of shimmed Halbach magnet. The B0 field is oriented in the z direction.

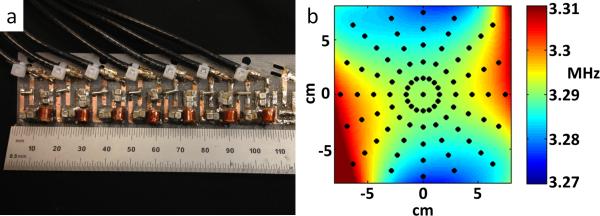

An accurate field map is critical for image reconstruction, particularly when nonlinear encoding fields force the use of iterative matrix solvers rather than the Fourier transform (14). The field is perturbed by external fields (including the earth's magnetic field), and must be remapped when the magnet is relocated. In order to quickly acquire center-plane field maps, a linear array of 7 field probes spaced 1.5cm apart was constructed (Fig. 3a). The field probes are tuned 5mm long, 4mm diameter, 18-turn solenoids measuring signal from 1mm capillaries of CuSO4-doped water (23). To acquire a field map the probes are held stationary while the magnet is rotated around them. Polynomial basis functions are then fit to the measured points and the field map (Fig. 3b) is synthesized. The polynomial coefficients up to 6th order of one magnet rotation angle are shown in table 1. The net magnetic field from the NdFeB magnets is sensitive to temperature (on the order of 4 kHz/deg C for the Halbach magnet) as well as interactions with external fields, so an additional field probe is used to monitor field drift during data acquistion. This navigator probe is mounted to the Halbach array and rotates with the magnet. The measured field changes, ΔB0, are then accounted for in the image reconstruction.

Figure 3.

(A) Linear array of 7 NMR field probes used for mapping the static magnetic field. The probes are held stationary, while the magnet is rotated around them and points on the 2D center plane are sampled. (B) Measured field map for the center transverse slice through the magnet after fitting 6th order polynomials to the probe data. The black dots mark the location of the probe measurements. The field is plotted in MHz (proton Larmor frequency). This field distribution serves as the SEM information used in image reconstruction.

Table 1.

Polynomial composition of Halbach magnet SEM in Hz/cm(m+n)

| znym | n=0 | n=1 | n=2 | n=3 | n=4 | n=5 | n=6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m=0 | z0y0 : 3.3e6 | z1y0 : −89 | z2y0 : −274 | z3y0 : 1.9 | z4y0 : 1.1e-2 | z5y0 : 2.4e-2 | z6y0 : 9.2e-3 |

| m=1 | z0y1 : −62 | z1y1 : 104 | z2y1 : −8.3 | z1y3 : −1.7 | z1y4 : −4.6e-2 | z1y5 : −1.8e-3 | |

| m=2 | z0y2 : 164 | z1y2 : −13.3 | z2y2 : −0.53 | z3y2 : −0.12 | z4y2 : 0.11 | ||

| m=3 | z0y3 : 3.9 | z1y3 : 6.5 | z2y3 : 4.4e-2 | z3y3 : −2.3e-2 | |||

| m=4 | z0y4 : 0.95 | z1y4 : 0.21 | z2y4 : −1.9e-2 | ||||

| m=5 | z0y5 : −3.9e-3 | z1y5 : −6.6e-2 | |||||

| m=6 | z0y6 : 9.2e-3 |

The calculated polynomial coefficients composing the z-y plane (2D imaging plane) of the Halbach spatial encoding field are shown. Measured points from the linear array of field probes (fig. 3) were used for this 6th order polynomial fit.

Acquisition Method

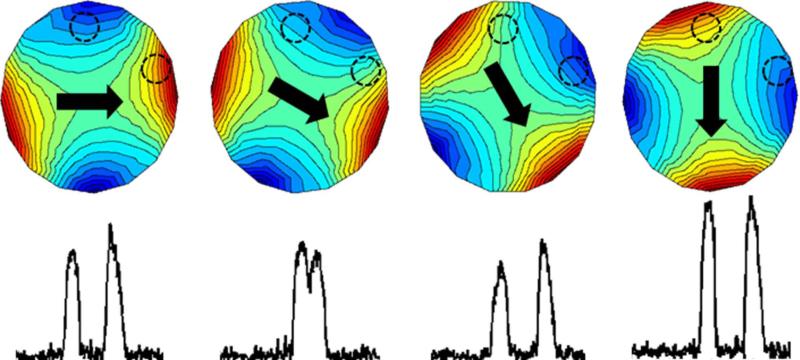

To acquire data, the magnet is physically rotated around the sample in discrete steps. At each rotation step, generalized projections onto the nonlinear field are acquired (similar to those described in (24)). Examples of these projections are shown in Fig. 4 for a simple two-sphere phantom. The field experienced by the spheres changes at each rotation due to the non-linear SEM, providing new information in each projection.

Figure 4.

Schematic depiction of the generalized projections (bottom row) of an object onto the rotating SEM field. The object consists of two water-filled spheres depicted as dashed black lines which are superimposed on the Halbach magnet's SEM field at a few rotations (black arrow depicts B0 orientation). The NMR spectrum was acquired with a single volume Rx coil.

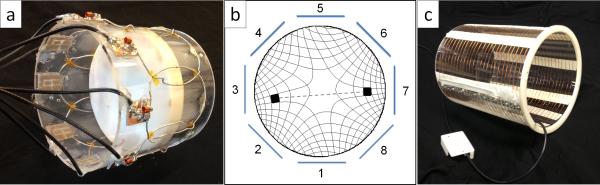

The constructed Rx coil array (Fig. 5a) consists of eight 8cm diameter loops of wire encircling the FOV on the surface of a 14cm diameter cylinder. The inductances of the coils are roughly 230 nH, requiring capacitors on the order of 10 nF (Voltronics, Salisbury, MD) for tuning. Geometric decoupling and PIN diode detuning were implemented (25, 26). The coils are tuned and matched to 50 Ohm impedance low noise preamplifiers (MITEQ P/N AU-1583, Hauppauge, NY).

Figure 5.

(A) Photo of the 8 channel receiver array coil with 3D printed disk-phantom at isocenter. The 14cm diameter array is made up of eight, 8 cm loops overlapped to reduce mutual inductance. (B) Relative voxel size is illustrated as a function of radius from the center using two rotations of the magnet's SEM (field isocontour lines illustrated in figure). Symmetry of the isocontours causes aliasing of each voxel through the origin. Using the local sensitivity profiles of an encircling array of coils, the correct location of each signal source in the FOV can be resolved. (adapted from (28)) (C) Photo of the 25 turn, 20cm diameter, 25cm length solenoid transmit coil.

A Tecmag Apollo console with TNMR software (Houston, TX) was used. The console has 1 transmit channel, 3 gradient channels, and 1 receive channel. Since the programmable gradient analog outputs are not needed for gradient coils, they are used for other purposes. For example, the Gz gradient output is used to control the stepper motor for magnet rotation. The fact that the console only has 1 receive channel means that true parallel imaging cannot be performed. Instead, the receive channel is switched between the coils in the array, acquiring data serially. The Gx gradient output along with a RelComm Technologies (Salisbury, MD) relay and Arduino UNO board are used to switch between the receive coils. Although pre-amp decoupling has not been implemented yet, data is being acquired from one coil at a time, permitting the other receive coils to be detuned to prevent coupling.

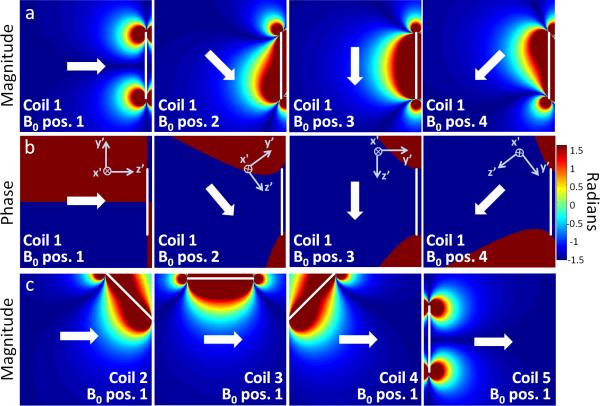

Two scanner coordinate systems are defined because the object and RF coils remain stationary while B0 is rotated. The rotating coordinate system of the magnet and the spins is defined as x’, y’, z’ (examples shown in Fig. 6b), and fixed coordinate system for the coils and objects is defined as x, y, z (shown in Fig. 1 and 2). Image reconstruction requires accurate knowledge of the coil sensitivity map, Cq,r (x). Here the index q refers to the coil channel and r to the rotation position of the magnet. The coil sensitivity map is different for each rotation position since B1− is formed from a projection of the coil's B1 field onto the x’-y’ plane (which rotates with the magnet). In conventional MRI, B1− is mapped by imaging a phantom with fully sampled encoding by the gradient waveforms. However, this approach is not possible with our encoding scheme because knowledge of Cq,r(x) is necessary to form an image wit hout aliasing.

Figure 6.

Biot-Savart calculation of the sensitivity map of the Rx coil array. The white arrows show representative orientations of B0, which define the spin coordinate system orientation (x’,y’,z’). Image reconstruction requires accurate coil sensitivity profiles for each B0 angle used in the experiment. (A-B) B1− magnitude and phase for a single representative surface coil located at the right side of the FOV (position marked with white line). Because of the symmetry of the coils’ at isocenter, the coils’ x’ component is approximately zero, and the process of taking the projection onto the x’-y’ plane (to solve for B1−) will produce a vector parallel or anti-parallel to y’. Therefore, the B1− phase is always +90° or −90° in the depicted transverse isocenter plane. (C) B1− magnitude of 4 different coils of the array (marked with white lines) for a single magnet rotation position.

Because of the difficulty of measuring B1− on our scanner, we use estimated B1− maps. Magnetostatic approximations are suitable at the 3.29 MHz Larmor frequency, so B1 of the individual coils was modeled with Biot-Savart calculations. By symmetry, the x component of the circular surface coils’ B1 is zero in the center plane FOV. The x’ component B0 is also nearly zero because of the geometry of the magnet. So the coil sensitivity calculation reduces to a two dimensional problem, since only the B1 component perpendicular to B0 contributes to the sensitivity map.

To calculate the coil sensitivity map for each rotation (r), the B1 component parallel to B0r (the B0 vector for rotation r) is subtracted and we are left with the perpendicular component.

| [1] |

The phase is equal to the angle, θr, between and B0r, which will either be +90° or –90° due to the symmetry properties discussed above. The variation in a single coil's B1− as a function of B0 angle is illustrated in Figure 6a-b, and the B1− magnitude for 4 coils and a single B0 angle is shown in Figure 6c. When B0 points along the normal to the coil, the sensitivity profile resembles a “donut” pattern with low sensitivity in the center of the FOV. Maximum signal sensitivity occurs when B0 is oriented orthogonal to the normal vector of the coil loop.

Similar to single-sided imaging methods (7), echo formation requires the use of spin echo sequences in the presence of the inhomogeneous field. The T2* of the signal is short due to the static Spatial Encoding Magnetic field (SEM) and it is impossible to do the equivalent of gradient echo refocusing because the sign of the SEMs cannot be quickly switched. However, the encoding can be repeated and averaged to improve SNR in a spin-echo train, which does refocus the SEM. Unlike in high-field systems, the specific absorption rate (SAR) from the consecutive 180° pulses is negligible because of the low excitation frequency (3.29 MHz).

Unlike conventional MRI scanners, the B0 field of the Halbach magnet is oriented radially instead of along the bore of the magnet. This means that in order for B1+ to be orthogonal to B0 at all rotations, it should be directed along the cylindrical axis of the Halbach magnet. This makes a solenoid more suitable than a birdcage coil for RF excitation. The constructed solenoid, shown in figure 5c, has a 20cm diameter and a 25cm length. N=25 turns of AWG 20 was chosen as a reasonable value in the tradeoff between B1+ homogeneity and parasitic capacitance from closely spaced windings. The 70 uH Tx coil is tuned to 3.29 MHz with eight 230pF series capacitors distributed along the length of the solenoid, which reduces the susceptibility to stray capacitance. Because the static SEM field is “always on”, the transmit coil must have a relatively low Q in order to excite a wide bandwidth of spins. The Q of the coil is about 60 corresponding to a 55 KHz bandwidth. A 1 KW power amplifier (Tomco, Stepney, SA, Australia) is used to produce short 600W pulses for broadband excitation (25μs for 90° pulses and 50μs for 180° pulses).

PIN diode detuning is used in the transmit and receiver coils to prevent coil interaction (25). The tuning/matching circuits are constructed so that the transmit coil is tuned and the receive coils are detuned when the pin diodes are forward biased with console controlled DC voltage. The converse is true when the diodes are reverse biased (Tx coil detuned and Rx coils tuned).

Reconstruction Method

The Halbach magnet's spatial encoding field is approximately quadrupolar and therefore produces a non-bijective mapping between object space and encoding space. This encoding ambiguity leads to aliasing in the image through the origin. As described by Hennig et al. (13), parallel imaging with encircling receive coils can be used to disambiguate the non-bijective mapping. This is possible because the coil sensitivity profiles provide additional spatial encoding that localizes signal within each source quadrant of the FOV, eliminating aliasing. This idea is illustrated in Figure 5b. This specific implementation of the portable scanner closely resembles the case of PatLoc imaging with quadrupolar fields and a radial frequency-domain trajectory (28). However, the measured Halbach SEM is not purely quadrupolar, and the presence of arbitrary field components prevents the decomposition of the rotating SEM into linear combinations of 2 orthogonal encoding fields. For this reason, the direct back-projection reconstruction method described in (28) is not valid, and iterative matrix methods such as those described in (29) are used.

The discretized signal acquired by a coil (q) at a given magnet rotation (r) at time n can be described as

| [2] |

where m(x) is the magnetization of the object at location vector x, Cq,r(x) is the complex sensitivity of the coil at location x, and k(r,x,n) is the evolved phase from the nonlinear gradient at rotation r, location x, and time n. The exponential term and coil sensitivity term can be grouped together to form the encoding function encq,r(x, n).

| [3] |

The matrix form of this signal equation for a single projection readout acquired with one RF coil is simply

| [4] |

The acquired signal, Sq,r, is a vector made up of the sampled readout points (Nsmp). The object that we are solving for, m, is a vector made up of all the image voxels (Nvox). The encoding matrix, Eq,r, contains the evolved phase of each voxel in the FOV for each time point in the acquisition as well as the coil sensitivity multiplier. With linear gradient fields, E is made up of the sinusoidal Fourier basis set, which allows the image to be reconstructed using radial back-projection, k-space re-gridding, and other approaches. In the nonlinear SEM case, E is more complicated, but can be calculated from the measured field maps. Before the appropriately rotated field map is used to calculate the phase evolution, the field change captured by the navigator probe during the acquisition is added as a global offset.

A separate block of the encoding matrix, Eq,r is calculated for the data acquired by each coil at each rotation. There will be a total of R*C blocks (where R is total number of rotation and C is the total number of coils), which are vertically concatenated to form the full encoding matrix, E. S is also made up of vertically concatenated subparts, Sq,r, which are the signals acquired from each coil at each rotation.

To reconstruct the image from the acquired data, the object, m, can be found by inverting the matrix, E. However, the full encoding matrix size is Nsmp *R*C × Nvox. In the typical case of 256 readout points, 181 rotations, 8 coils and a 256×256 voxel reconstructed image, the full matrix size is 371K × 65K. Since it is not computationally feasible to invert this matrix, iterative methods such as the Conjugate Gradient method (30) and the Algebraic Reconstruction Technique (31,32) can be used to solve for the minimum norm least squares estimator of m. The generality of this approach allows arbitrary field shapes and coil profiles as well as systematic errors such as temperature-dependent field drifts to be incorporated into the encoding matrix.

The reconstructed images and simulations shown here were done using the Algebraic Reconstruction Technique. The encoding matrix was calculated line by line during the reconstruction using the appropriately rotated and temperature drift-corrected field map and the calculated coil sensitivity profiles for the given B0 direction. To demonstrate the importance of temperature drift compensation, a phantom image was also reconstructed with an uncorrected encoding matrix. The field of view of the images is 16 cm and the in-plane voxel size is 0.625 mm.

Phantom Imaging Methods

Images of a “MIT/MGH” phantom were acquired both with a single channel solenoid Rx coil and with 7 coils of the Rx array. The 3D printed polycarbonate phantom is 1.7cm thick with a 13cm diameter, and is filled with CuSO4-doped water. Thirty-two averages of a 6 spin-echo train (TR = 550 ms, echo-spacing = 8ms) were acquired for 91 rotation angles over 180 degrees. Navigator field probe data was also acquired at each rotation. The coil array's lengthy acquisition time of 66 minutes results from multiplexing a single console receiver and would be reduced to 7.3 minutes by acquiring data from all channels and the field probe in parallel.

A 1cm thick lemon slice was imaged using only the bottom 5 surface coils with 181 1° rotations. The total acquisition time was 93 minutes (15.5 minutes if surface coils and navigator probe were acquired in parallel). A single average of a 128 echo train at each rotation provided sufficient SNR. Each echo was recorded as 256 pts with a 40 KHz BW (TR = 4500ms, echo spacing = 8ms). For comparison, the lemon image was also reconstructed using only 91 rotations out of 181 acquired rotations in addition to the full reconstruction.

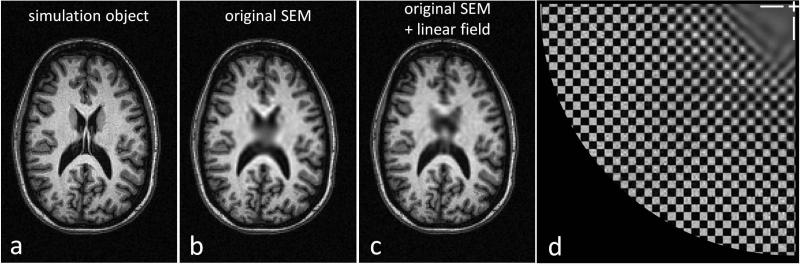

Image simulation methods

The described acquisition method was simulated using the measured field map from the central slice of the Halbach magnet. Images were simulated using a high resolution T1 brain image or a numerically generated checkerboard with 2.5mm grid size as the “object.” The measured field map and calculated coil profiles of the 8 coil array were used in the forward model to generate the simulated data. In one simulation, an artificial field map was used to simulate the addition of a linear field component to measured SEM. Complex noise was added to the simulations to match noise levels observed in comparable phantom projection. These simulations were done with the same sequence parameters of the lemon image: 181 1° magnet rotations, 256 pt readout, 40 KHz BW, echo spacing = 8ms.

Results

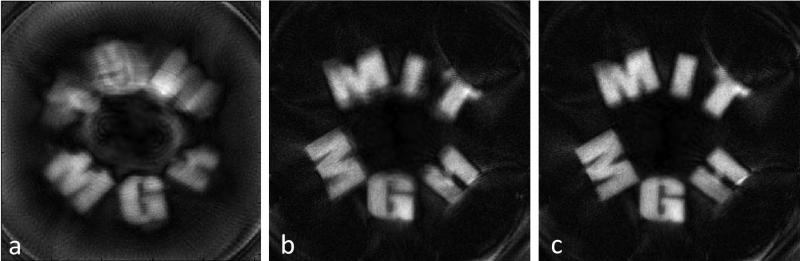

Experimental images of the 3D printed “MIT MGH” phantom are shown in Figure 7. The image acquired with the solenoid coil used in transmit/receive mode is shown in Figure 7a. Only the “MGH” part of the phantom was filled at the time, so the top half of the image should ideally be empty. Instead the expected aliasing pattern is seen through the center onto frequency matched quadrants of the FOV. The aliased image is markedly more blurry than one would expect for a purely quadrupolar field, which maps all signals symmetrically about the center during reconstruction. This discrepancy likely arises due to the presence of first-order and higher-order field terms which perturb the symmetry of the dominant quadrupolar field.

Figure 7.

Experimental 256×256 voxel, 16cm FOV images of a 3D printed phantom with CuSO4 doped water occupying the interior of the letters and polycarbonate plastic surrounding it. The phantom has a 13cm dia. and is 1.5cm thick. 91 magnet rotations spaced 2° apart were used, readout bandwidth/Npts = 40 KHz/256, TR = 550ms, spin-echo train length = 6 or 16, with 8ms echo-spacing. Echoes in the spin-echo train for a given rotation were averaged. (A) Image acquired with solenoid Rx coil (32 averages of a 6 spin-echo train). (B) Image acquired with 7 coils of the Rx coil array (8 averages of a 16 spin-echo train). Temperature drift was not corrected for. (C) Image from same data as (B), but with temperature drift correction implemented.

The importance of monitoring and correcting for field drift due to temperature is emphasized by comparing Fig. 7b and Fig. 7c which show images with and without temperature drift correction. The drift correction is achieved by monitoring the frequency seen by the navigator field probe which rotates with the magnet. This probe's frequency is ideally independent of the rotation angle during the acquisition, but varies due to two causes. Firstly, small changes in room temperature translate to a global scaling of the Halbach array's magnetization and thus the central B0. With no attempt to insulate or stabilize the magnet's temperature, changes up to 0.4 °C and 1.6 KHz were observed over an hour. The second cause for the fixed probe's change in field as a function of rotation is due to the changing vector sum of the earth's field and the Halbach field. This effect creates a peak-peak variation of 3.7 kHz for the magnet location and orientation. This effect must also be incorporated in the encoding matrix. Even though field drift correction is applied to Fig. 7c, some of the letters are sharper than others; this is likely attributable to field map inaccuracies.

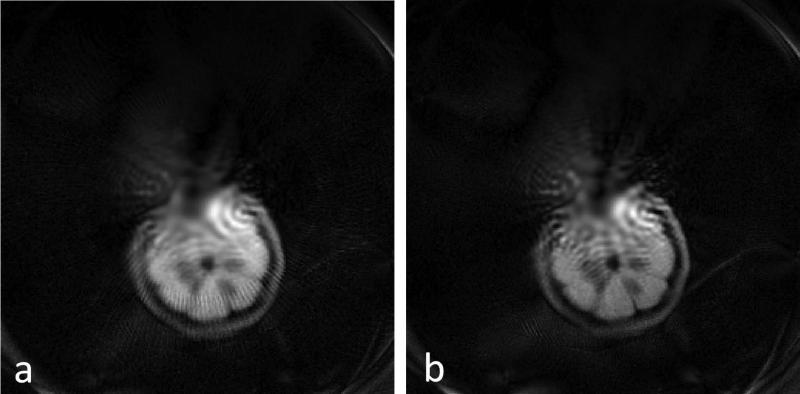

The 1cm lemon slice images are seen in Figure 8. The use of 5 out of 8 coils of the receive array prevents aliasing in the image, but center blurring is more pronounced in these images than in the simulations (Fig. 9). Figure 8a was reconstructed using half of the rotations angles of Figure 8b, resulting in poorer image quality and streaking artifacts.

Figure 8.

Experimental 256 × 256 voxel, 16cm FOV image of a 1 cm thick slice of lemon placed off axis in the magnet. 5 receiver coils of the array were used to acquire 1 average of a 128 spin-echo train, readout bandwidth/Npts = 40 KHz/256, TR = 4500ms, echo-spacing = 8ms. A) 91 magnet rotations spaced 2° apart were used (B) 181 magnet rotations spaced 1° apart were used.

Figure 9.

Simulated images using the calculated sensitivity profiles of the 8 coil Rx array to generate the forward model for 181 1° rotations of the encoding field, 6.4ms, 256 point readouts. The data seen by the Halbach scanner was simulated by processing this “object” through the forward model and adding noise to make it consistent with the SNR of the time-domain signals measured in a water phantom. The model data was then reconstructed using the Algebraic Reconstruction Technique in a 16cm FOV. (A) Reference high resolution 3T T1 weighted brain image used as the model object. Note: the SEMs were scaled to the brain FOV. (B) Simulated reconstruction using the measured SEM to generate the forward model. (C) Simulated reconstruction using the measured SEM with the additional artificial linear field component (500 Hz/cm). (D) Simulated reconstruction of a 2.5mm grid numerical phantom. Only one quadrant of the FOV is shown, the center of the FOV is marked with white cross-hairs in the upper right.

Figure 9 shows an encoding and reconstruction simulation using a typical high field T1-weighted brain MRI as the imaging object (Fig. 9a). Noise was added to the object model to simulate the lower SNR of the low field scanner. Figure 9b shows a simulated image using the measured encoding field of Halbach magnet. There is no aliasing in the image because the calculated coil sensitivity profiles of the 8 channel Rx array were used. However, there is blurring in the center which coincides with the shallow region of the nonlinear gradient field. The center blurring in Figure 9c is reduced because the image was simulated using an artificial field map that consists of our measured SEM plus an additional linear field of 500 Hz/cm. The simulation of the 2.5mm grid numerical phantom (Fig. 9d) shows the ultimate resolution possible with the existing experimental protocol in the absence of systematic errors. Outstanding resolution at the periphery gradually gives way to a blurry central region.

Discussion

As expected, the non-bijective mapping of the Halbach magnet's SEM results in aliasing. Fortunately, as described in (13) the aliasing is resolved by the addition of a multi-channel receive array with differing spatial profiles and an appropriate geometry. Since the Halbach encoding is dominated by the quadrupolar “PatLoc” SEM, the system's spatially-varying voxel size changes approximately as c/ρ within the FOV, where ρ is the radius and the constant c depends on the strength of the SEM and the length of the readout (27). This means that our Halbach magnet encoding field results in higher resolution at the periphery due to the uniform nature of the SEM near the center of the FOV. This center blurring is seen in both the experimental images in Fig. 8 and the simulations in Fig. 9.

While we did not attempt to control the precise spherical harmonic distribution in the magnet design, future work will likely benefit from shimming the magnet to obtain a more desirable SEM. For example, if a sufficient linear term were added, the uniform encoding field region would not lie on-axis with the rotation. In this case, which is simulated in Fig. 9c, the “blind-spot” would move around the object allowing some rotations to contribute to encoding of any given pixel, as previously explored in “O-Space imaging” (14). Pursuing this strategy even further would result in a SEM containing only a linear term. In this case, the encoding becomes very similar to a radial imaging scheme with conventional gradients, and to the strategy proposed by Cho et al. who used a rotating gradient coil in a conventional magnet (12). With accurate field mapping instrumentation and shimming software, we suspect that the magnet could be shimmed to a more desirable SEM. Although a linear SEM would eliminate the encoding hole and allow a more straightforward reconstruction method, there are advantages to second-order SEMs including the coincidence of the high spatial resolution area and high coil sensitivity area near the edge of the FOV.

The lemon images of Fig. 8 show that when 91 projection rotations are used instead of 181, a radial streaking artifact is visible. The streaking artifacts are consistent with those arising in conventional undersampled radial trajectories played by linear SEMs as well as undersampled radial trajectories played by PatLoc SEMs (27). It has been shown that the use of total variation and total generalized variation priors during reconstruction suppresses streaking artifacts in undersampled conventional radial (33) and PatLoc radial (34) acquisitions. Similar techniques may be pursued in future work to suppress streaking in images obtained with fewer projection rotations of our scanner.

The simulations in Figure 9 show the theoretical resolution of the scanner when systematic errors are eliminated. These errors are most likely a result of field map and coil sensitivity profile inaccuracies, which are critical to the iterative reconstruction (14). The current coil sensitivity profiles facilitate proof-of-concept reconstructions, but their fidelity is suspect because they were calculated rather than measured. In these calculations the magnetostatic Biot Savart approximation was used with no external structures present. While wavelength effects in the body are not expected at this frequency, the close proximity of the conducting magnets and other coils might perturb the experimental fields. Additionally, a 2D field map is currently used to reconstruct thin samples (1 to 1.5cm thick), but field variation does exist in the x direction (along the axis of the Halbach cylinder) within the sample thickness. This causes through-plane dephasing and must be incorporated into the encoding matrix based on a 3D field map.

Field map errors arise from temperature drifts which are significant on the time scale of the imaging and mapping acquisitions. We have shown that any uncorrected temperature drift causes substantial blurring in the image (Fig. 7b). Temperature drift is a pervasive problem in permanent magnet MRI and has been addressed in a number of ways. In the current experimental protocol the frequency at a fixed point is measured at every rotation and the drift is built into the encoding matrix as a global offset to the field maps. This method reduces blurring considerably (Fig. 7c), but other options have been proposed for permanent magnet NMR and MRI that may offer higher encoding matrix accuracy. For example, Kose et al. (1) describes the implementation of a NMR lock method plus thermal insulation. Additionally, a new Halbach design was recently reported which uses two types of magnet materials with different temperature coefficients to substantially reduce the effect of temperature changes on the B0 field (35). When compared to an uncompensated SmCo magnet, this reduced their temperature coefficient 100 fold, bringing the field drift down to 10ppm for a 3°C temperature change. However this method has the disadvantage of producing a lower field and requiring more magnet material than the traditional design.

For time-efficient acquisitions, true parallel imaging will be needed. To accomplish this goal, a multi-channel receiver console is required, as well as the implementation of pre-amp decoupling. This is advantageous for practical diagnostic reasons and will also alleviate the field drift problem by shortening acquisition times. In addition to multiple channels, future prototypes must be made larger to accommodate the human head. Although the head can be fit into the presented magnet, its 36cm diameter does not leave sufficient room for the transmit and receive arrays as well as the structural supports for the magnetic material. Construction of a larger diameter magnet with the same basic design will result in a reduced B0 field, although this could be mitigated by adding more magnet material and/or higher grade material. The current B0 field of 77.3 mT is estimated to decrease to 62 mT if the diameter is increased to 40cm. However if 24 N45 NdFeB magnet rungs are used instead of 20 N42 rungs, a field of 80 mT is theoretically achievable. The standard landmark for brain imaging (between the eyebrows) is 18cm above the shoulders. The presented Halbach magnet was designed using the maximum cylinder length that allows the brain to be centered in the magnet (2×18cm). Future magnet designs will likely adhere to this constraint because increasing the length of the magnet requires increasing the bore size to fit shoulders, which would result in a considerably weaker B0.

In the described experiments the B0 field rotates relative to the receiver coils (coils are stationary), which causes the shape of the coil profiles to change with each acquisition angle. However this arrangement is not a requirement for rotating SEM imaging, and in theory the receiver coils could rotate with the magnet. In this case, the coil sensitivity profiles are simply rotated for each acquisition angle, but the shapes of profiles do not change. Data acquisition with rotating coils and stationary coils was simulated. However, there was not a significant difference in performance in either the visual appearance of the reconstructed images or the RMSE (root mean squared error). For data simulated with 91 magnet rotations there was a 0.2% RMSE improvement when using the rotating coil profiles, and for data simulated with 23 magnet rotations (undersampled) there was a 3.6% RMSE improvement. This suggests that rotating the coil array may improve performance when data is undersampled. The 23 rotation simulated images are included in the supplemental material. The rotating receive coil case is similar to the RRFC (Rotating RF Coils) method described in (36, 37), where continuously rotating surface coils are used in a conventional magnet for parallel imaging.

The goal of the current work was to provide a proof-of-principle that the basic 2D encoding scheme can be performed, which was demonstrated with 2D imaging of thin samples. However, the addition of 3rd axis encoding is an obvious requirement for medical applications. A promising possibility for encoding the 3rd dimension (along the axis of rotation) is Transmit Array Spatial Encoding (TRASE) (15,16). TRASE uses custom-designed RF coils to generate uniform amplitude but linear B1+ phase variation along the encoding axis. Spatial encoding is achieved using at least two Tx coils with different phase gradients (typically differing by their sign). Spin-echo trains are used in which the linear phase variation is changed by 180 degrees in between successive refocusing pulses. As the sign of the refocusing pulse is flipped over the course of the echo train, k-space is traversed one echo at a time. The resolution depends on the number of echoes used and the slope of the transmitted B1 phase ramp across the FOV (16). The approach is synergistic with the echo trains used in the presented encoding scheme for purposes of signal averaging. Furthermore, at low field, TRASE spin-echo trains do not suffer from the SAR limits that may impact the method's performance at high field.

Conclusion

Using an inhomogeneous magnet for spatial encoding in lieu of gradient coils, we have constructed and demonstrated a lightweight scanner for 2D MR imaging with minimal power requirements. The 2D proof-of concept images from this nearly head-sized imager show the ability of this encoding scheme to produce sufficient spatial resolution and sensitivity for the detection and characterization of many common neurological disorders such as hydrocephalus and traumatic space-occupying hemorrhages. Future work in perfecting the calibration methods is likely to bring experimental image quality closer to the theoretical limit, but the resolution of the current system is sufficient for identifying gross pathologies. With the future implementation of true parallel imaging and 3D encoding, this scanner has the potential to enable a truly portable, low-cost brain imaging device.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure: Simulated images comparing the performance of rotating and stationary receiver coil arrays in the rotating Halbach magnet. Data was simulated using 23 8° rotations of the encoding field and 6.4ms, 256 point readouts. The model data was then reconstructed using the Algebraic Reconstruction Technique in a 16cm FOV. (A) Reference high resolution 3T T1 weighted brain image used as the model object. Note: the SEMs were scaled to the brain FOV. (B) Simulated reconstruction with added noise using stationary coil profiles (same as experimental setup). The root mean squared error (RMSE) of the simulated image compared with the reference image is 208.3. (C) Simulated reconstruction with added noise using coil profiles that rotate with the magnet, RMSE = 201.1. Compared to brain simulations in figure 9, these simulated images contain more artifacts because the data was undersampled (23 magnet rotations versus 181 rotations).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Matthew Christensen and Cris LaPierre for their 3D modeling and design work, Bastien Guerin for advice on calculating coil sensitivities, and Stephen Cauley for help with reconstruction methods. This research was supported by the Department of Defense, Defense Medical Research and Development Program, Applied Research and Advanced Technology Development Award W81XWH-11-2-0076 (DM09094). This research was carried out at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at the Massachusetts General Hospital, using resources provided by the Center for Functional Neuroimaging Technologies, P41EB015896, a P41 Biotechnology Resource Grant supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health. This project was supported by a training grant from the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research (T90DA022759/R90DA023427). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Kose K, Haishi T. High resolution NMR imaging using a high field yokeless permanent magnet. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2011;10:159–167. doi: 10.2463/mrms.10.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimura T, Geya Y, Terada Y, Kose K, Haishi T, Gemma H, Sekozawa Y. Development of a mobile magnetic resonance imaging system for outdoor tree measurements. Rev Sci Instrum. 2011;82:053704. doi: 10.1063/1.3589854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerlach R, du Mesnil de Rochemont R, Gasser T, Marquardt G, Reusch J, Imoehl L, Seifert V. Feasibility of Polestar N20, an ultra-low-field intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging system in resection control of pituitary macroadenomas: lessons learned from the first 40 cases. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:272–284. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000312362.63693.78. discussion 284–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson JA, Burnett LJ, Harmon JF. Remote (inside-out) NMR. III. Detection of nuclear magnetic resonance in a remotely produced region of homogeneous magnetic field. J Magn Reson. 1980;41:411–421. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sagawa M, Fujimura S, Togawa N, Yamamoto H, Matsuura Y. New material for permanent magnets on a base of Nd and Fe (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 1984;55:2083–2087. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinberg R, Sezginer A, Griffin D, Fukuhara M. Novel NMR apparatus for investigating an external sample. J Magn Reson. 1992;97(3):466–485. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casanova F, Perlo J, Blümich B. Single-Sided NMR. Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.G. Eidmann RS. The NMR MOUSE, a mobile universal surface explorer. J Magn Reson Se ries A. 1996;122:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Todica M, Fechete R, Blümich B. Selective NMR excitation in strongly inhomogeneous mag netic fields. J Magn Reson. 2003;164(2):220–227. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlo J, Casanova F, Blümich B. 3D imaging with a single-sided sensor: an open tomograph. J Magn Reson. 2004;166(2):228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landeghem MV, Danieli E, Perlo J, Blümich B, Casanova F. Low-gradient single-sided NMR sensor for one-shot profiling of human skin. J Magn Reson. 2012;215:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho ZH, Chung ST, Chung JY, Park SH, Kim JS, Moon CH, Hong IK. A new silent magnetic resonance imaging using a rotating DC gradient. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39(2):317–321. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hennig J, Welz AM, Schultz G, Korvink J, Liu Z, Speck O, Zaitsev M. Parallel imaging in non-bijective, curvilinear magnetic field gradients: a concept study. Magn Reson. Mater. Phy. 2008;21(1-2):5–14. doi: 10.1007/s10334-008-0105-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stockmann JP, Galiana G, Tam L, Juchem C, Nixon TW, Constable RT. In vivo O-Space imaging with a dedicated 12 cm Z2 insert coil on a human 3T scanner using phase map calibration. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(2):444–455. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharp JC, King SB. MRI using radiofrequency magnetic field phase gradients. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(1):151–161. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharp JC, King SB, Deng Q, Volotovskyy V, Tomanek B. High-resolution MRI encoding using radiofrequency phase gradients. NMR in Biomed. 2013 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmerman C, Blau J, Rosen MS, Wald LL. Design and construction of a Halbach array magnet for portable brain MRI.. Proceedings of the 20th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Melbourne, Australia. 2012. p. 2575. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooley CZ, Stockmann JP, Armstrong BD, Rosen MS, Wald LL. A lightweight, portable MRI brain scanner based on a rotating Halbach magnet.. Proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting; Salt Lake City, USA. 2013; ISMRM; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stockmann JP, Cooley CZ, Rosen MS, Wald LL. Flexible spatial encoding strategies using rotating multipolar fields for unconventional MRI applications.. Proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. 2013.p. 2664. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raich H, Blümler P. Design and construction of a dipolar Halbach array with a homogeneous field from identical bar magnets: NMR Mandhalas. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance Part B: Magnetic Resonance Engineering. 2004;23B(1):16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wroblewski P, Szyszko J, Smolik WT. Mandhala magnet for ultra low-field MRI.. 2011 IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques (IST); 2011.pp. 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halbach K. Design of permanent multipole magnets with oriented rare earth cobalt material. Nuclear Instruments and Methods. 1980;169(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Zanche N, Barmet C, Nordmeyer-Massner JA, Pruessmann KP. NMR probes for measuring magnetic fields and field dynamics in MR systems. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(1):176–186. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schultz G, Gallichan D, Reisert M, Hennig J, Zaitsev M. MR image reconstruction from generalized projections. Magn Reson Med. 2013 doi: 10.1002/mrm.24928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edelstein W, Hardy C, Mueller O. Electronic decoupling of surface-coil receivers for NMR imaging and spectroscopy. Journal of Magnetic Resonance (1969) 1986 Mar;67(1):156–161. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roemer PB, Edelstein WA, Hayes CE, Souza SP, Mueller OM. The NMR phased array. Magn Reson Med. 1990;16(2):192–225. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910160203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schultz G, Ullmann P, Lehr H, Welz AM, Hennig J, Zaitsev M. Reconstruction of MRI data encoded with arbitrarily shaped, curvilinear, nonbijective magnetic fields. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(5):1390–1403. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schultz G, Weber H, Gallichan D, Witschey WRT, Welz AM, Cocosco CA, Hennig J, Zaitsev M. Radial imaging with multipolar magnetic encoding fields. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2011;30(12):2134–2145. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2011.2164262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stockmann JP, Ciris PA, Galiana G, Tam L, Constable RT. O-space imaging: Highly efficient parallel imaging using second-order nonlinear fields as encoding gradients with no phase encoding. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(2):447–456. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hestenes M, Stiefel E. Methods of Conjugate Gradients for Solving Linear Systems. Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards. 1952;49(6):409–436. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaczmarz S. Angenäherte Auflösung von Systemen linearer Gleichungen. Bulletin International de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences et des Lettres. 1937;35:355–357. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon R, Bender R, Herman GT. Algebraic reconstruction techniques (ART) for three-dimensional electron microscopy and x-ray photography. J Theor Biol. 1970;29(3):471–481. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(70)90109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Block KT, Uecker M, Frahm J. Undersampled radial MRI with multiple coils. Iterative image reconstruction using a total variation constraint. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57(6):1086–1098. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knoll F, Schultz G, Bredies K, Gallichan D, Zaitsev M, Hennig J, Stollberger R. Reconstruction of undersampled radial PatLoc imaging using total generalized variation. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(1):40–52. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Danieli E, Perlo J, Blümich B, Casanova F. Highly stable and finely tuned magnetic fields generated by permanent magnet assemblies. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;110(18):180801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.180801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trakic A, Weber E, Li BK, Wang H, Liu F, Engstrom C, Crozier S. Electromechanical de sign and construction of a rotating radio-frequency coil system for applications in magnetic resonance. IEEE transactions on bio-medical engineering. 2012;59(4):1068–1075. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2012.2182993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li M, Jin J, Trakic A, Liu F, Weber E, Li Y, Crozier S. Hign acceleration with a rotating ra diofrequency coil array (RRFCA) in parallel magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).. 2012 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2012; pp. 1098–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure: Simulated images comparing the performance of rotating and stationary receiver coil arrays in the rotating Halbach magnet. Data was simulated using 23 8° rotations of the encoding field and 6.4ms, 256 point readouts. The model data was then reconstructed using the Algebraic Reconstruction Technique in a 16cm FOV. (A) Reference high resolution 3T T1 weighted brain image used as the model object. Note: the SEMs were scaled to the brain FOV. (B) Simulated reconstruction with added noise using stationary coil profiles (same as experimental setup). The root mean squared error (RMSE) of the simulated image compared with the reference image is 208.3. (C) Simulated reconstruction with added noise using coil profiles that rotate with the magnet, RMSE = 201.1. Compared to brain simulations in figure 9, these simulated images contain more artifacts because the data was undersampled (23 magnet rotations versus 181 rotations).