Abstract

Introduction

Melasma is one of the most common pigmentary disorders seen by dermatologists and often occurs among women with darker complexion (Fitzpatrick skin type IV–VI). Even though melasma is a widely recognized cause of significant cosmetic disfigurement worldwide and in India, there is a lack of systematic and clinically usable treatment algorithms and guidelines for melasma management. The present article outlines the epidemiology of melasma, reviews the various treatment options along with their mode of action, underscores the diagnostic dilemmas and quantification of illness, and weighs the evidence of currently available therapies.

Methods

A panel of eminent dermatologists was created and their expert opinion was sought to address lacunae in information to arrive at a working algorithm for optimizing outcome in Indian patients. A thorough literature search from recognized medical databases preceded the panel discussions. The discussions and consensus from the panel discussions were drafted and refined as evidence-based treatment for melasma. The deployment of this algorithm is expected to act as a basis for guiding and refining therapy in the future.

Results

It is recommended that photoprotection and modified Kligman’s formula can be used as a first-line therapy for up to 12 weeks. In most patients, maintenance therapy will be necessary with non-hydroquinone (HQ) products or fixed triple combination intermittently, twice a week or less often. Concomitant camouflage should be offered to the patient at any stage during therapy. Monthly follow-ups are recommended to assess the compliance, tolerance, and efficacy of therapy.

Conclusion

The key therapy recommended is fluorinated steroid containing 2–4% HQ-based triple combination for first line, with additional selective peels if required in second line. Lasers are a last resort.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13555-014-0064-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Dermatology, Efficacy, Hydroquinone, Laser, Melasma, Peels, Photoprotection, Prevalence, Retinoids, Safety, Topical steroids, Treatment

Introduction

Melasma (from the Greek word melas, meaning ‘black’) is a common, acquired, circumscribed hypermelanosis of the sun-exposed skin [1, 2]. It presents as symmetric, hyperpigmented macules having irregular, serrated, and geographic borders. The most common locations are the cheeks, upper lips, the chin, and the forehead, but other sun-exposed areas may also be occasionally involved. Studies indicate the possible role of several risk factors such as genetics, sunlight, age, gender, hormones, pregnancy, thyroid dysfunction, cosmetics, and medications [1]. The objective of the current study was to prepare a treatment consensus and algorithm based on clinical experience and review of the evidence from available literature.

Methods

A panel of eminent dermatologists with at least 10 years of clinical experience combined with academic contribution and interest in the subject of melasma was created and their expert opinion was sought to address lacunae in information to arrive at a working algorithm for optimizing outcome in Indian patients.

The process was initiated with a literature search with the keywords as dermatology, hydroquinone, laser, melasma, peels, photoprotection, prevalence, retinoids, safety, topical steroids, and treatment. The databases searched included MEDLINE, COCHRANE LIBRARY, and SCIENCE DIRECT DATABASE.

Literature was searched mainly over the period of the last 2 decades (1990 to August 2013) to include data and latest concepts in melasma epidemiology and therapy. However, a few publications from the 1980s and two from the 1970s have also been included so that valuable foundation concepts as well as evolution of current therapies and past issues with certain drugs are also included.

Articles pertaining to risk and predisposing factors for melasma as well as articles on melasma management, including clinical assessment, investigations, drug therapies, combinations, procedural therapies, and newer emerging therapies, from peer reviewed journals were included. Articles not adequately powered or not randomized with poorly defined methodology and articles with conflicting or non-committal results were excluded.

A total of 115 publications until August 2013 were obtained by electronic database searches of which 52 were randomized controlled trials (1 retrospective) and 42 were review articles (17 were reviews and discussions of specific drug/combination or procedural treatment). The remaining publications included eight articles on prevalence data, five articles of case series, five articles on investigations and histopathology, and three articles on validating scoring and grading systems. The literature search was completed and then followed by three panel discussion sessions, each in the form of a 1-day residential focused program where clinical experiences of each panelist were brought to the table along with the study of the associated literature and publications. All discussions, suggestions, and panel consensus were recorded by a medical writer who was present. In addition, experienced persons from the field of pharmaceuticals also contributed with respect to the pharmacological aspects of the various drug therapies. In between each of these sessions, the outcome and consensus of the previous session were drafted and shared with the panel members for further refining. After all panel discussion sessions were concluded, the final draft of the panel consensus and algorithm was prepared along with the summary of the reviewed literature. This draft was finally refined and accepted by the panelists to come up with a clinically practical, relevant, and acceptable treatment algorithm for melasma. The deployment of this algorithm is expected to act as a basis for guiding and refining therapy in the future.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and the expert opinion of the authors, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Risk and Predisposing Factors

Melasma commonly occurs in women during their reproductive years. Pregnancy and use of oral contraceptives through estrogen mediated melanocyte stimulation is apparent in the pathogenesis of melasma [2–4]. Dark-haired persons (Fitzpatrick skin types III–VI) are more susceptible to melasma [5]. Several studies have reported a high incidence of melasma in family members suggesting its genetic predisposition [3, 6–11].

The ultraviolet (UV) component of sunlight is the major triggering and aggravating factor in melasma causing focal melanocyte hyperplasia and increase in melanosomes [1, 12, 13].

The use of topical cosmetics and fragrances as well as phototoxic drugs can also trigger or aggravate melasma by sensitizing the skin and inducing postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH). Melasma is considered as photocontact dermatitis in a study conducted by Verallo-Rowell [14].

Melasma is classified according to the depth of melanin pigment into epidermal melasma with mixed melasma (a combination of the epidermal and dermal types) having a worse prognosis [1].

Principles of Therapy

The objectives of melasma therapy should be protection from sunlight and depigmentation. Pigment reduction is achieved by using chemicals that interfere with various steps of the melanogenesis pathways via: (i) the retardation of proliferations of melanocytes; (ii) the inhibition of melanosome formation and melanin synthesis; and (iii) the enhancement of melanosome degradation [15]. Table 1 shows the classification of the pigment-reducing agents based on their mechanism of action [16–18].

Table 1.

| Stage of melanin synthesis | Deposition | Active molecules |

|---|---|---|

| Before melanin synthesis | Tyrosinase transcription | Tretinoin, c-2 ceramide |

| Tyrosinase glycosylation | PaSSO3Ca | |

| Inhibition of plasmin | Tranexamic acid | |

| During melanin synthesis | Tyrosinase inhibition | Hydroquinone, mequinol, azelaic acid, kojic acid, arbutin, deoxyarbutin, licorice extract, rucinol, 2,5-dimethyl-4-hydroxy-3(2H)-furanone, N-acetyl glucosamine, resveratrol, oxyresveratrol, ellagic acid, methyl gentisate, 4-hydroxyanisole |

| Peroxidase inhibition | Phenolic compounds | |

| Reactive oxygen species scavengers | Ascorbic acid, ascorbic acid palmitate, thiotic acid, hydrocumarins | |

| After melanin synthesis | Tyrosinase degradation | Linoleic acid, α-linoleic acid |

| Inhibition of melanosome transfer | Niacinamide, serine protease inhibitors, retinoids, lecithins, neoglycoproteins, soybean trypsin inhibitor | |

| Skin turnover acceleration | Lactic acid, glycolic acid, linoleic acid, retinoic acid | |

| Regulation of melanocyte environment | Corticosteroids, glabiridin | |

| Interaction with copper | Kojic acid, ascorbic acid | |

| Inhibition of melanosome maturation | Arbutin and deoxyarbutin | |

| Inhibition of protease activated receptor 2 | Soybean trypsin inhibitor |

First-line therapy usually consists of topical compounds that affect the melanin synthesis pathway, broad-spectrum photoprotection, and camouflage. Chemical peels are often added in second-line therapy. Laser and light therapies represent potentially promising options for patients who are refractory to other modalities, but also carry a significant risk of worsening the disease. A thorough understanding of the risks and benefits of various therapeutic options is crucial in selecting the best treatment.

Clinical Assessment of Melasma

Traditionally, Wood’s lamp examination is done to identify the location of pigment, but is limited to epidermal melasma and cannot be used reliably in Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI as dark-skin melanin pigmentation obscures the detection of dermal melanin [19]. Melasma is reliably graded on the basis of area and severity parameters [i.e., melasma area and severity index (MASI) score] [20, 21].

Pharmacologic Therapy

Sunscreens

Sunscreen use is vital throughout treatment and post-treatment to prevent hyperpigmentation and relapse of melasma. Broad-spectrum anti-UV A and B sunscreens with physical blocking agents like ZnO and TiO2 (SPF >30) should be used regularly to cover the affected areas. Patients with Fitzpatrick IV to VI skin types [22] are at a heightened risk from sun exposure [23, 24]. Indian patients avoid sunscreens due to oily, sticky nature and heat from exothermic reaction of chemicals. However, physical sunscreens do not release heat.

Hydroquinone

Hydroquinone (HQ; dihydroxybenzene) is structurally similar to precursors of melanin. HQ inhibits the conversion of dopa to melanin by blocking tyrosinase action [25] and inhibits the formation, melanization, and degradation of melanosomes. HQ also affects the membranous structures of melanocytes and eventually causes necrosis of whole melanocytes [26].

HQ has been used to treat hyperpigmentation for more than 50 years. While controversy exists regarding the long-term safety of HQ, its efficacy in treating melasma, both alone and in combination with other agents is well established [5]. HQ 2–4% is prominently used as a mono-therapy or in a combination cream. HQ preparations >5% are not recommended due to irritation, except for refractory cases [27, 28]. Pigment lightening by HQ becomes evident after 5–7 weeks of the treatment. Treatment with HQ should be continued for at least 3 months and up to 1 year [29].

For patients on HQ therapy, regular medical follow-up is essential: every 3 months for high phototype skin (Fitzpatrick type V and VI) patients and every 6 months for lighter skin types. Common adverse events (AEs) are erythema and burning. Other rare AEs are ochronosis and confetti-like depigmentation. Speckling or reticulation indicates ochronosis. Histopathology shows short, stout, curvilinear, ochre-colored fibers in the papillary dermis [30].

Tretinoin

Tretinoin, a retinoid (RA), inhibits transcription of the key melanin synthesis enzyme tyrosinase [16–18]. Tretinoin plays an important role in the triple-combination cream (described later) and is used as a chemical peel.

Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are anti-inflammatory molecules that exert an anti-metabolic effect on melanocytes, resulting in a decreased epidermal turnover and thus, may produce a mild pigment-reducing effect [31]. Corticosteroids are an active component of the triple-combination creams. Triple formulations using different corticosteroids have shown efficacy, for example, dexamethasone [32], hydrocortisone 1% [33], mometasone [34, 35], and fluorinated steroids [22, 36–41]. Researchers found that fluorinated steroids were more effective and safer than non-fluorinated steroids, for example, 0.01% fluocinolone acetonide and fluticasone [22].

Kojic Acid

Kojic acid can substitute for HQ if a patient is intolerant to HQ. Kojic acid inhibits tyrosinase by chelating copper at the enzyme’s active site. It is available in 1–4% concentrations, and also in combination with HQ. Caution is required in its use as kojic acid is a known sensitizer [5].

Azelaic Acid

Azelaic acid (AA) is anti-proliferative and selectively cytotoxic towards hyperactive melanocytes, inhibiting tyrosinase and mitochondrial oxidoreductase enzymes with minimal effects on normally pigmented skin [42]. In different trials, AA treatment was found to be less or as equally efficacious as HQ [42, 43] and hence may be used in case of intolerance to HQ.

Triple Combination

Based on the current evidence: sun avoidance, sunscreen use, and triple combination regimen is the most effective first-line treatment for melasma. Combination creams are more efficient bleaching agents than mono-therapies. The combination of HQ, a RA, and a topical steroid (5% HQ, 0.1% RA, and 0.1% dexamethasone), or Kligman and Willis’ formula was developed to enhance the efficacy of each individual ingredient, shortening the duration of therapy and reducing the risk of AEs [44, 45]. Since then, some variation of this formula is the most commonly used therapy for melasma worldwide [32]. Tretinoin prevents the oxidation of HQ and improves epidermal penetration while the steroid reduces irritation from the other two ingredients and suppresses biosynthetic and secretory functions of melanocytes, leading to an early response in melasma. The synergistic action of the three topical agents achieves significantly higher depigmentation than either agent alone. Improvement is seen in 8 weeks without any significant AE [46].

In India, a cream-based combination of HQ, tretinoin and mometasone has been extensively used after its launch in 2004. Long-term use on the face (generally >12 weeks) of corticosteroids, particularly mid-potent ones like mometasone can cause skin atrophy, telangiectasias, and/or an acneiform eruption [37]. Moreover, a relapse is common when mometasone use is stopped [47]. The combination treatment is supposed to be used for a maximum of 4–8 weeks after which the treatment should be stopped or the dose gradually reduced, and finally replaced with safer treatment modalities [48]. We found mometasone-based combination with glycolic acid (GA) peels caused AEs like hyperpigmentation, irritation, and persistent erythema in 2 out of 10 patients (20%) [34]. Triple-combination creams with mometasone should be prescribed only after thorough patient counseling with explanation of long-term AEs.

Evidence-based studies have shown triple combination of 4% HQ with 0.05% tretinoin and 0.01% fluocinolone acetonide to be the most efficacious and safe available topical modality for the first-line treatment of melasma [40, 41]. It is the only ointment currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of melasma. The safety and efficacy of the combination was initially demonstrated in 641 melasma patients in a multicenter, investigator blinded, randomized prospective trial [36, 39–41]. Night use of the triple-combination cream as compared to dual-combination creams (HQ + tretinoin, HQ + fluocinolone, or tretinoin + fluocinolone) achieved complete or near-complete clearance in 77% of patients. Clinically significant improvement was noted within 4–8 weeks [39]. The most common AEs were mild local irritation, erythema, and skin peeling. For the Indian skin, which is mostly of Fitzpatrick type IV–VI, a reduced HQ combination of 2% HQ + 0.05% tretinoin + 0.01% fluocinolone acetonide (HQ + RA + FA) was launched in 2010 [47]. Safety studies in Indian population need to be established. A recent Cochrane review of 20 studies with a total of 2,125 participants with 23 different treatments concluded that triple-combination cream was significantly more effective than HQ alone (relative risk 1.58, 95% CI 1.26–1.97) or dual combination [38].

The fluocinolone-based triple cream is safe in the treatment of moderate to severe melasma for up to 24 weeks. The risk of skin atrophy after 6 months of treatment with fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%, HQ 4%, and tretinoin 0.05% cream is very low as shown by histological examination [4].

In the expert opinion of the authors, fluticasone seems more effective and safer than mometasone and fluocinolone in the triple combination due to less long-term (> 12 weeks) steroidal AEs. Once-daily application of fluticasone (0.05%) was as efficacious as twice-daily application of betamethasone (0.12%), with less skin atrophy and an absence of systemic AE of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression [37]. In another study, fluticasone did not cause cortisol suppression or major skin atophy, and was similar to mometasone furoate in efficacy [49].

Dual Combination

The dual combinations are recommended if triple combination is not available or if patients are intolerant to it. Those available in India include HQ and GA, HQ and Kojic acid, and mequinol and tretinoin. Table 2 gives an overview of studies that provide evidence on topical agents for treating melasma.

Table 2.

Evidences involving important topical treatment options

| References | Study type | Treatment mode | Patients, n | Severity | Treatment duration | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monteiro et al. [77] | R, DB | 4% HQ vs. placebo + SPF 30 | 48 | N/K | 20 weeks | 38% HQ/8.3% placebo, total improvement |

| Haddad [27] | R, DB, SF | 4% HQ vs. placebo + SPF 25 | 30 | N/K | 3 months | 79% HQ/67% SWC improvement |

| Farshi [78] | R, O | 4% HQ vs. azelaic acid 20% | 29 | N/K | 2 months | After 2 months treatment, the MASI score was 6.2 ± 3.6 with HQ and 3.8 ± 2.8 with azelaic acid |

| Espinal-Perez et al. [79] | R, O, SF | 4% HQ vs. 5% ascorbic acid | 16 | N/K | 16 weeks | HQ side with 93% good and excellent results, compared with 62.5% on the ascorbic acid side. Side effects were present in 68.7% with HQ vs. 6.2% with ascorbic acid |

| Nanda et al. [80] | R, O | Priming with 2% HQ vs. 0.025% RA once daily (night time) 2 weeks before starting trichloroacetic acid peels (every 2 weeks for 12 weeks) | 50 | N/K | 6 months | HQ is superior to RA as a priming agent in maintaining the results achieved with peels and in decreasing the incidence of post-peel reactive hyperpigmentation |

| Balina and Graupe [43] | R, DB, MC | 4% HQ vs. 20% azelaic acid | 329 | N/K | 24 weeks | 65%/73% good or excellent in azelaic/HQ patients |

| Piquero Martín et al. [81], Verallo-Rowell et al. [82] | R, DB O | 4% HQ vs. 20% azelaic acid | 60 | N/K | 24 weeks | Azelaic acid was not better than the HQ in the treatment of melasma |

| Verallo-Rowell et al. [82], Lim [83] | R, DB | 2% HQ vs. 20% azelaic acid | 155 | N/K | 24 weeks | 73% of the azelaic acid patients, compared with 19% of the HQ patients, had good to excellent overall results |

| Lim [83], Ferreira Cestari et al. [84] | R | 2% KA, 2% HQ, 10% GA vs. 2% HQ, 10% GA | 40 | N/K | 12 weeks | 2% KA, 2% HQ, 10% GA improvement in 60% vs. 47.5% with 2% HQ, 10% GA |

| Ferreira Cestari et al. [84], Grimes et al. [85] | R, O | 4% HQ, 0.05% RA, 0.01% FA (TC) vs. 4% HQ + SPF 30 | 120 | M/S | 8 weeks | >75% improvement, 73% TC/49% HQ (P = 0.007) |

| Taylor et al. [39] | R, SB | 4% HQ, 0.05% RA, 0.01% FA (TC) vs. 4% HQ, 0.05% RA or 0.05% RA, 0.01% FA or 4% HQ, 0.01% FA + SPF 3 | 641 | M/S | 8 weeks | 77% TC; 47% HQ/RA; 27% FA/RA; 42% HQ/FA, cleared/almost cleared |

| Torok [41] | R, O, MC | 4% HQ, 0.05% RA, 0.01% FA (TC) + SPF 30 | 585 | M/S | 12 months | By month 12: 80% cleared or nearly cleared by physician assessment (of patients who remained in the study) |

| Grimes et al. [85] | MC, O | 4% HQ, 0.05% RA, 0.01% FA (TC) + SPF 30 | 1,290 | M/S | 8 weeks | 75% cleared or almost cleared at 8 weeks by physician assessment |

| Wu et al. [50] | O | TA 250 mg bid | 74 | N/K | 6 months | Excellent (10.8%, 8/74), good (54%, 40/74), fair (31.1%, 23/74), and poor (4.1%, 3/74). Side effects of TA such as gastrointestinal discomfort (5.4%) and hypomenorrhea (8.1%) were observed. Recurrence of melasma was observed in seven cases (9.5%) |

| Kanechorn Na Ayuthaya et al. [51] | R, DB, O, SF | Topical TA 5% vs. placebo | 23 | N/K | 12 weeks | Results were not significant between the two regimens |

| Lee et al. [52] | O | 0.05 mL TA (4 mg/mL) was injected intradermally | 100 | N/K | 12 weeks | (9.4%) rated as good (51–75% lightening), 65 patients (76.5%) as fair (26–50% lightening), and 12 patients (14.1%) as poor (0–25% lightening) |

DB double blind, FA fluocinolone acetate, GA glycolic acid, HQ hydroquinone, KA kojic acid, MASI Melasma Area Severity Index, M/S moderate/severe, MC multicenter, N/K not known, O open, R randomized, RA tretinoin, SB single blind, SF split face, SPF sun protection factor, SWC skin whitening cream, TC triple combination, TA tranexamic acid

Adjunctive Therapies

These include a wide range of chemicals and natural extracts have been tested against melasma (Table 3). Tranexamic acid is the most common adjunctive therapy to be used and works by decreasing melanogenesis in epidermal melanocytes and provides a rapid and sustained lightening in melasma [50–53]. Other therapies include a substance called ‘antipollon’, a finely grained aluminum silicate that possesses the ability to adsorb melanin. Laboratory studies with different concentrations have shown up to 86% melanin adsorption with 0.8% antipollon. However, clinical studies establishing its efficacy are awaited (Antipollon-HT efficacy testing Nikkol Chemicals, data on file).

Table 3.

Adjunctive therapeutic agents for melasma [86]

| Therapeutic agent |

|---|

| Tranexamic acid |

| Vitamin C |

| Vitamin E |

| Soybean extract |

| Topical liquiritin |

| Licorice extract |

| Gigawhite |

| Bearberry extract |

| Pepper mulberry extract |

| Arbutin |

| Indomethacin |

| Niacinamide |

| Nicotinic acid |

| 4-N butylresorcinolmercury |

| Melawhite |

Interventions

Intervention procedures are used in combination with topical first-line therapy to treat recalcitrant melasma when patient shows poor or no response. Intervention techniques include chemical peels, lasers, intense pulsed light (IPL), cryosurgery, dermabrasion, and micro-dermabrasion. They are not considered as first-line therapy as they can cause PIH and are often ineffective [54–56]. Chemical peels, lasers, and IPL are described here as their use in melasma is better studied in the Indian setting to some extent.

Chemical Peels

Chemical peels used for treating melasma are described in Table 4. There is a medium-quality evidence to suggest that undergoing serial chemical peels with GA, salicylic acid, or trichloroacetic acid (TCA) is moderately effective in the treatment of melasma (Table 5) [22, 53, 57, 58]. GA peels are used as an adjunctive therapy in refractory cases of epidermal melasma as they enhance the efficacy of topical regimen [59]. There are many studies comparing GA and other peels for melasma in dark-skinned patients (Table 6) [53].

Table 4.

Treatment mode and regimen for chemical peels

| Chemical peel | Treatment mode and regimen | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| GA | 30–70%. Superficial peel. After a test peel, serial GA peels are applied 3–5 min every 2–3 weeks. The peel is then neutralized using water or 1% bicarbonate solution [53, 56, 58–60, 73, 87, 88] | – |

| LA | 92%. Superficial peel. 2 coats of LA at pH 3.5 are applied for 10 min every 3 weeks [87–89] | Safe and effective, gentle action |

| SA | Superficial peel. 20–30% plus HQ at 2-week intervals | Tendency of darker skins to dyschromias, even superficial peels to be used with caution [62]. A new derivative of SA with an additional fatty chain, the lipohydroxy acid, has increased lipophilicity, a more targeted mechanism of action and greater keratolytic effect. It is yet to be demonstrated if the peel is equally effective and safer than the conventional SA peels in patients with melasma [54, 55, 59, 60, 89, 90] |

| TCA | 10–30%. Superficial peel. Or 35–50% medium-depth peel. Peels 1–2 months, >13 months. Peel washed off upon frosting | May cause scarring and PIH in dark skin, to be used with caution [53, 58–60, 90] |

| Tretinoin | 1–5%. Superficial peel. Tretinoin at 1% strength is applied for 4 h once a week, for 12 weeks [91, 92] | – |

| MA | Superficial peel. MA at 30–50% applied weekly or biweekly and used as a face wash at 2% | Available in algae extract gel or lotion base at 2–10% in isolation or in combination with vitamins C and E. Less erythema and synergistic effect with laser [53, 93] |

| Phytic acid | Applied once a week but can be repeated twice a week for accelerated effect. 5–6 peel sessions are required to achieve lightening | No neutralization required. Safe and effective for dark skin. No irritation, burning, or scarring [53, 58, 94] |

GA glycolic acid, HQ hydroquinone, MA mandelic acid, LA Lactic acid, PIH postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, SA salicylic acid, TCA trichloroacetic acid

Table 5.

Levels of evidence and strength of recommendations for various peeling agents in ethnic skin

| Classification | Peeling agent | Level of evidence | Strength of recommendation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial peel | Phytic acid | Expert opinion | C | [53] |

| Lactic acid | Uncontrolled trial | B | [87, 88] | |

| Glycolic acid | Non-randomized controlled study | A | [55, 58, 59, 72, 89, 90, 94–96] | |

| Salicylic acid | Uncontrolled trial | B | [54] | |

| Jessner’s solution | Uncontrolled trial | B | [97] | |

| Superficial-medium peel | Pyruvic acid | Expert opinion | C | [98] |

| Medium-depth peel | Trichloroacetic acid | Uncontrolled trial | B | [96, 97] |

A: There is good evidence to support the use of the procedure, B: There is fair evidence to support the use of the procedure, C: There is poor evidence to support the use of the procedure

Table 6.

Comparative studies with chemical peels for melasma in dark skin [53]

| References | Study type | Treatment mode | Patients, n | Treatment duration | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kalla et al. [89] | R, O | 55–75% GA vs. 10–15% TCA | 100 | Every 15 days | Response faster in TCA as compared to GA, but side effects more in TCA |

| Khunger et al. [90] | O, SF | 1% tretinoin peel vs. 70% GA | 10 | Biweekly for 12 weeks | Decreased MASI, no difference between the two sides |

| Sharquie et al. [87, 88], | O, SF | 92% pure lactic acid vs. Jessner’s solution | 30 | Every 3 weeks with maximum 5 sessions | Statistically significant improvement on both sides |

| Safoury et al. [97] | O, SF | Modified Jessner’s + 15% TCA vs. 15% TCA | 20 | Every 10 days with 8 sessions | Better improvement with combination peel |

| Kumari and Thappa [94] | R, O | 20–35% GA vs. 10–20% TCA | 40 | Every 15 days for 12 weeks | About 75% improvement on both sides |

| Sobhi and Sobhi [96] | O, SF | 70% GA vs. nanosome vitamin C | 14 | 6 sessions | Better results on vitamin C side |

GA glycolic acid peel, MASI melasma area severity index, O open, R randomized, SF split face, TCA trichloroacetic acid peel

Chemical peels cause controlled exfoliation, followed by regeneration of epidermis and dermis [60]. Superficial and medium-depth peels have been employed with variable success in the treatment of melasma. After a superficial peel, epidermal regeneration can be expected within 3–5 days and desquamation is usually well accepted [61]. Because of the risk of prolonged dyschromia, medium-depth and deep peels should be avoided in patients with dark skin. In the authors’ opinion, maintenance sessions or repeat sessions may be necessary. Patients should be well informed.

Lasers and Light Therapy

Lasers have a limited role in the treatment of melasma. Though successful use of Q-switched (QS) lasers [50], fractional lasers [57, 62–66], IPL [56], and combination lasers [67–69] has been reported, response to treatment is unpredictable and pigmentation frequently recurs. In addition, PIH is common in Indian patients. Hence, a maintenance schedule has to be initiated and continued. For these reasons, lasers are not routinely recommended as the treatment of choice for melasma in Indian patients. It may be used in selected resistant cases, at the discretion of the treating physician, after proper counseling. A test patch may be performed prior to treating the lesion. QS laser and low-fluence mode laser toning alone or in combination with either fractional CO2 laser or IPL have shown reasonable success in treating melasma of Asian patients (Table 7). A number of studies have shown successful treatment of melasma with fractional lasers [non-ablative Er (Erbium): Glass 1,540/1,550 nm lasers], and they are recommended in all skin types [57, 62–65].

Table 7.

Treatment mode and regimen for laser therapy

| Type of laser | Mechanism | Treatment mode | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| QS Nd:YAG Laser 1,064 nm (low-fluence mode laser toning) | Photothermolysis of melanin in melanosomes in the melanocytes and keratinocytes. Also photoacoustic effect. Sub-cellular selective photothermolysis occurs in the low-fluence mode. Destroys melanin without cell damage | 10 sessions, once weekly | End point is mild erythema, with no whitening. A large spot size (6 mm) should be exposed to 1–2 passes with minimal overlap. This treatment is recommended in all skin types. Priming with triple-combination cream prior to laser therapy is recommended [91, 96]. PIH and blotched depigmentation have been reported [91, 99] |

| Combination of QS Nd:YAG 1,064, with the fractional CO2 laser | Laser toning, using a large spot size with very low fluence giving multiple passes at frequent intervals | 10 sessions, every 2–3 weeks | Promising treatment modality. Concomitant and post-therapy topical treatment to maintain remission. Maintenance sessions may be needed in case of relapse |

| IPL | Same as laser | – | Effective in treating refractory melasma in Asian patients [56, 67] |

| Combination of IPL with QS Nd:YAG laser 1,064 nm (low-fluence mode laser toning) | Same as laser | 1st session IPL for clearing epidermal melasma followed by 4–5 sessions of QS Nd:YAG laser at 2-week intervals | Rapid resolution of mixed-type melasma with possible long-term benefits [67–69]. This treatment is recommended in all skin types |

IPL intense pulsed light, Nd:YAG neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet, PIH postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, QS Q switched

Algorithm for Indian Melasma Patients

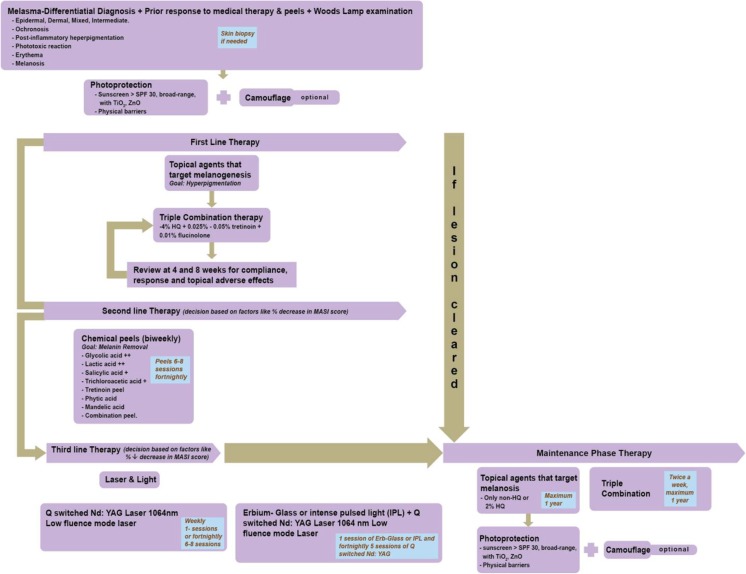

India is a country of multiple ethnicity and origin, covering a wide range of skin types. Melasma is found more frequently in Fitzpatrick type III–VI skin [48]. Based on Pigmentary Disorders Academy (PDA) recommendations for melasma treatment for dark-skin types and a thorough review and grading of the literature on evidence-based studies (listed in Table 8) [48, 61] an algorithm is proposed in Fig. 1 to treat Indian melasma patients. All treatments included and their hierarchy in the algorithm is based on the grading of the associated clinical studies according to the US preventive services task force levels of evidence for grading clinical trials [70].

Table 8.

Level and quality of evidence for melasma therapies

| Therapy | Level of evidence | Quality of evidence | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topical | |||

| 2% HQ | II–ii | C | [83] |

| 4% HQ | I | B | [27, 43, 78, 85] |

| 0.1% tretinoin (RA) | I | B | [20, 100] |

| 0.05% RA | I | C | [92] |

| 0.05% Isotretinoin | II–ii | C | [92, 101] |

| 4% N-acetyl-4-S-Cysteaminylphenol | III | C | [101, 102] |

| 5% HQ + 0.1–0.4% RA + 7% LA/10% AC | III | C | [102, 103] |

| 3% HQ + 0.1% RA | III | C | [102, 103] |

| 2% HQ + 0.05% RA + 0.01% fluocinolone acetonide | I | A | [38, 39, 41, 74, 85, 103, 104] |

| 2% HQ + 0.05% RA + 0.01% dexamethasone (modified KF) | III | C | [55, 86] |

| 2% HQ + 0.05% RA + 0.01% dexamethasone (modified KF + 30–40% GA peel) | III | B | [55, 86] |

| 5% HQ + 0.1% RA, and 1% hydrocortisone | III | C | [32, 33] |

| 4% HQ + 5% GA | II–ii | B | [104, 105] |

| 4% KA + 5% GA | II–ii | B | [98, 99] |

| 2% KA + 2% HQ + 10% GA | II–iii | C | [83, 84] |

| 2% HQ + 10% GA | II–iii | C | [83, 84] |

| 4% HQ + 10% GA | I | B | [105, 106] |

| 20% Azelaic acid | I | B | [42, 43] |

| 20% Azelaic acid + 0.05% RA | III | C | [106, 107] |

| Vitamin C iontophoresis | II–i | C | [107, 108] |

| Adapalene | II–ii | B | [99, 100] |

| Chemical peels | |||

| 10–50% GA | II–ii/III | C | [53, 59] |

| 10% + 2% HQ + 20–70% GA | II–ii | C | [56, 58] |

| 20–30% GA + 4% HQ | II–i | B | [108, 109] |

| 70% GA | II–i | B | [109, 110] |

| Jessner’s solution | II–i | C | [109, 110] |

| 20–30% Salicylic acid | III | C | [54, 55] |

| 1–5% RA | III | C | [108, 111] |

| 50% GA + 10% KA | III | C | [109, 112] |

| Laser therapy (+ chemical peels + topical therapies) | |||

| Q-switched ruby | IV | C | [110, 113] |

| Pulsed CO2 + Q-switched alexandrite | IV | C | [67, 68] |

| Q-switched alexandrite laser | IV | C | [69, 70] |

| Q-switched alexandrite laser + 15–25% TCA peel + Jessner’s solution | III | C | [111, 114] |

| Erbium: YAG | III | D | [112, 115] |

| Dermabrasion | II–iii | E | [76, 113] |

In accordance with the US preventive services task force levels of evidence for grading clinical trials. Reproduced with permission from [48]

A: There is good evidence to support the use of the procedure, B: There is fair evidence to support the use of the procedure, C: There is poor evidence to support the use of the procedure, D: There is fair evidence to support the rejection of the use of the procedure, E: There is good evidence to support the rejection of the use of the procedure

AC ascorbic acid, GA glycolic acid, HQ hydroquinone, KA kojic acid, KF kligman’s formula, LA lactic acid, RA retinoic acid, TCA trichloroacetic acid

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for melasma treatment in India. HQ hydroquinone, MASI melasma area and severity index, SPF sun protection factor

The key considerations in developing the algorithm are: the Fitzpatrick skin types susceptible to melasma in the Indian population, the severity of melasma, the sensitivity of patients to active ingredients of medication, the patient treatment history, any existing skin condition (besides melasma), possible therapy-related AEs such as PIH, exogenous ochronosis, blotchy depigmentation, irritation, erythema; and the probability of pigment recurrence after stopping treatment, i.e., prognosis indicators. The darker skin types tend to be highly sensitive to treatment agents, for example, ochronosis on HQ treatment, sensitization to KA, and skin irritation reactions to peeling agents like GA. In addition, darker skin types are more prone to PIH post-treatment and have a greater chance of relapse [71]. With these considerations in mind, darker skin types, which are commoner among Indian people, are recommended longer treatment periods, with lower concentrations of those treatment agents that can induce PIH or irritation, followed by longer maintenance periods to prevent recurrence of pigmentation and melasma. We have found that treatments like laser therapy, although described for all skin types in literature, are in fact not suitable for Indian skin as PIH and relapse occurs frequently once treatment is stopped in spite of maintenance therapy. However, light therapy does have some value in Indian patients.

In the opinion of the authors, broad-spectrum sunscreen use during and post-treatment is mandatory, along with protective clothing and hats. Experts recommend the fixed triple combination as the first-line therapy for all melasma types and degrees of severity, and dual combinations or single agents should be considered only when it is unavailable or patients have sensitivity to the ingredients [48]. In such cases, we suggest dual-combination therapy (e.g., HQ + GA) or monotherapy (e.g., 4% HQ, 0.1% retinoic acid, or 20% AA). For moderate or severe melasma which does not respond to first-line treatment, options for second-line therapy include peels either alone or in combination with topical therapy.

In the opinion of the authors, some patients will require therapy to maintain remission status and a combination of topical therapies should be considered. A minimum of four sessions of a given peel are suggested before changing to an alternative therapy. It is to be noted that for Indian skin types, especially Fitzpatrick types IV–VI, the concentration of certain agents should be reduced; 5% HQ should be avoided for Indian patients as PIH and irritation are more likely at higher concentrations. Because of the risk of prolonged hyperpigmentation, medium-depth peels like ≥35% TCA should be conducted with caution in patients with dark-skin types; deep peels should not be used in these patients. Furthermore, chemical peels are generally used to treat only the epidermal and mixed forms of melasma, as an attempt to treat with deep peels often leads to unwanted complications like hypertrophic scarring and permanent depigmentation. There are ample studies on the effect of GA peels on ethnic skin [55] (Table 9) and hence make for a recommended choice of treatment. In most of these studies, there was a moderate improvement achieved in almost one-half of the patients [58, 59, 72, 73].

Table 9.

Studies of melasma therapy on ethnic skin [53]

| References | Number and ethnicity of patients | Peel | Topical therapy | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lim and Tham [58] | 10 Asian (women) | 20–70% GA | – | Not statistically significant |

| Grimes [54] | 6 (darker racial ethnic groups in USA) | 20–30% SA | – | Moderate improvement in 66% patients |

| Jawahari et al. [59] | 25 Indian | 50% GA | Sunscreen SPF 15, 10% GA | 46.7% epidermal, 27.8% mixed, 0% dermal |

| Grover and Reddu [73] | 15 Indian | Serial GA peels | – | Good to fair improvement |

| Sharquie et al. [87] | 20 Iraqi | 92% LA | – | Significant improvement in all 12 patients who completed study |

| Godse and Sakhia [72] | 20 Indian | Serial GA peels | Triple combination and sunscreen | >50% improvement in half of patients |

GA glycolic acid, LA lactic acid, SA salicylic acid

Lasers should rarely be used in the treatment of melasma and, if applied, it is important to consider skin type. The mode-toning laser treatment is generally recommended in all skin types and its major advantage is that it destroys melanin without cell damage. Both QS low fluence and IPL are effective for recalcitrant melasma, when patients are non-responsive to other treatments, or when patients are intolerant of other treatment medications. The combination of IPL with QS laser gives a rapid resolution of mixed-type melasma with possible long-term benefits [67–69]. Fractional non-ablative lasers can be considered only if all other modalities fail. Ablative lasers should not be considered.

Patient consent and a photograph of the condition must be obtained prior to therapy. As important as actual therapy is proper patient counseling, and an understanding of the psychosocial impact on the patient and of his/her condition leading to low quality of life [74, 75]. This is likely to lead to a better patient compliance and an adherence to the regimen. It has been reported in Indian patients that overuse of certain treatment modalities such as mometasone-based therapies leads to undesirable fallouts [47, 49].

The recommendation is to use an alternative triple-combination cream, better suited for Indian patients, i.e., 2% HQ, 0.05% tretinoin, and 0.01% of the mild steroid fluocinolone acetonide cream. Another option is to replace the mometasone-based triple combination after 4–8 weeks, with a fluocinolone or a hydrocortisone-based one for a further 3- to 6-month period. As discussed earlier, this cream is safe and effective based on extensive clinical studies. The gradual withdrawal of the therapeutic agent is also a consideration and is achieved by decreasing doses of the active agent. The proposed algorithm for Indian patients is presented in Fig. 1.

Bad Prognosis Indicators

There are several conditions that determine the outcome of treatment in melasma since its etiology is multifactorial. Several factors predict potential failure of treatment (listed in Table 10). Moin et al. [3] found a statistically significant relationship between melasma and ethnicity, and phototype and grade of parity. Exogenous ochronosis has also been reported to be being misdiagnosed as a melisma treatment failure [76]. However, these prognostic factors lack sufficient scientific evidence.

Table 10.

Bad prognosis factors

| Factors that govern negative treatment outcome |

|---|

| Phenotype III–VI: dark hair and/or dark skin |

| Genetic and familial predisposition [3, 6, 8–10] |

| Long-term melasma in spite of ≥2 years of treatment |

| History of procedural interventions |

| Treated by ≥2 physicians |

| Long-term self-treatment with steroids [46, 47] |

| Ochronosis [76, 114] |

| Mixed-type melasma [115] |

Conclusion

Here, the Indian dermatologists panel has graded the results of safety and efficacy of various melasma therapies from clinical trials conducted worldwide (Table 7) applying the quality and level of evidence based on the US preventive services task force on health care (Table 8). Focus on the efficacy as well as AEs particular to the major skin types of Indian population, using evidence from clinical trials and physicians’ experience in the clinic, has directed the selection process for each recommended therapy. Using these guidelines, a much needed algorithm specific to melasma in India has been evolved and will assist physician’s decision on melasma treatment, disease management, and optimal outcome. We have also brought to attention some practices in treatment of melasma, for example, prolonged use of mometasone-based triple combination and prognosis indicators that have negative connotations. The key therapy recommended is fluorinated steroid containing 2–4% HQ-based triple combination for first-line therapy, with additional selective peels if required in second-line therapy. Lasers are a last resort.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. The authors acknowledge the help provided by Medical writer Ms Madhavi Muranjan for manuscript writing and Knowledge Isotopes Ltd. for editing and submission. Wockhardt Pvt. Ltd. funded the medical writing assistance and article processing charges for this article.

Conflict of interest

Krupa Shankar, Kiran Godse, Sanjeev Aurangabadkar, Koushik Lahiri, Venkat Mysore, Anil Ganjoo, Maya Vedamurty, Malavika Kohli, Jaishree Sharad, Ganesh Kadhe, Pashmina Ahirrao, Varsha Narayanan, and Salman Abdulrehman Motlekar declare no current conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and the expert opinion of the authors, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato S, Fitzpatrick TB, Sanchez JL, Mihm MC., Jr Melasma: a clinical, light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunofluorescence study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4(6):698–710. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hexsel D, Rodrigues TC, Dal’Forno T, Zechmeister-Prado D, Lima MM. Melasma and pregnancy in southern Brazil. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(3):367–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moin A, Jabery Z, Fallah N. Prevalence and awareness of melasma during pregnancy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(3):285–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim NH, Lee CH, Lee AY. H19 RNA downregulation stimulated melanogenesis in melasma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23(1):84–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Draelos ZD. Skin lightening preparations and the hydroquinone controversy. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20(5):308–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goh CL, Dlova CN. A retrospective study on the clinical presentation and treatment outcome of melasma in a tertiary dermatological referral centre in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 1999;40(7):455–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortonne JP, Arellano I, Berneburg M, et al. A global survey of the role of ultraviolet radiation and hormonal influences in the development of melasma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(11):1254–1262. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkar R, Puri P, Jain RK, Singh A, Desai A. Melasma in men: a clinical, aetiological and histological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(7):768–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vazquez M, Maldonado H, Benmaman C, Sanchez JL. Melasma in men. A clinical and histologic study. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27(1):25–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1988.tb02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivayathorn A. Melasma in orientals. Clin Drug Invest. 1995;10(Suppl. 2):34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarvjot V, Sharma S, Mishra S, Singh A. Melasma: a clinicopathological study of 43 cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52(3):357–359. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.54993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27(2):96–101. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000154419.18653.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang WH, Yoon KH, Lee ES, et al. Melasma: histopathological characteristics in 56 Korean patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(2):228–237. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-0963.2001.04556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verallo-Rowell VM. Skin in the tropics:Sunscreen and hyperpigmentation. Philippines: Anvil Publishing Inc; 2001. ISBN: 971-27-1136-6.

- 15.Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Katsambas A. Hyperpigmentation and melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6(3):195–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briganti S, Camera E, Picardo M. Chemical and instrumental approaches to treat hyperpigmentation. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16(2):101–110. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, Jung E, Huh S, et al. Mechanisms of melanogenesis inhibition by 2,5-dimethyl-4-hydroxy-3(2H)-furanone. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(2):242–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solano F, Briganti S, Picardo M, Ghanem G. Hypopigmenting agents: an updated review on biological, chemical and clinical aspects. Pigment Cell Res. 2006;19(6):550–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ortonne JP, Passeron T. Melanin pigmentary disorders: treatment update. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23(2):209–226. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimbrough-Green CK, Griffiths CE, Finkel LJ, et al. Topical retinoic acid (tretinoin) for melasma in black patients. A vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(6):727–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandya AG, Hynan LS, Bhore R, et al. Reliability assessment and validation of the melasma area and severity index (MASI) and a new modified MASI scoring method. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheth VM, Pandya AG. Melasma: a comprehensive update: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(4):699–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahmoud BH, Hexsel CL, Hamzavi IH, Lim HW. Effects of visible light on the skin. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84(2):450–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahmoud BH, Ruvolo E, Hexsel CL, et al. Impact of long-wavelength UVA and visible light on melanocompetent skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(8):2092–2097. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palumbo A, d’Ischia M, Misuraca G, Prota G. Mechanism of inhibition of melanogenesis by hydroquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1073(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(91)90186-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jimbow K, Obata H, Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB. Mechanism of depigmentation by hydroquinone. J Invest Dermatol. 1974;62(4):436–449. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12701679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haddad AL, Matos LF, Brunstein F, Ferreira LM, Silva A, Costa D., Jr A clinical, prospective, randomized, double-blind trial comparing skin whitening complex with hydroquinone vs. placebo in the treatment of melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(2):153–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katsambas AD, Stratigos AJ. Depigmenting and bleaching agents: coping with hyperpigmentation. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(4):483–488. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(01)00182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prignano F, Ortonne JP, Buggiani G, Lotti T. Therapeutical approaches in melasma. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25(3):337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandyopadhyay D. Topical treatment of melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54(4):303–309. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.57602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynde CB, Kraft JN, Lynde CW. Topical treatments for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Skin Ther Lett. 2006;11(9):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kligman AM, Willis I. A new formula for depigmenting human skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111(1):40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang WH, Chun SC, Lee S. Intermittent therapy for melasma in Asian patients with combined topical agents (retinoic acid, hydroquinone and hydrocortisone): clinical and histological studies. J Dermatol. 1998;25(9):587–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1998.tb02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Godse KV. Triple combination of hydroquinone, tretinoin and mometasone furoate with glycolic acid peels in melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54(1):92–93. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.49005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulhalli P, Chevli T, Karnik R, Sheth M, Mulgaonkar N. Comparative potency of formulations of mometasone furoate in terms of inhibition of ‘PIRHR’ in the forearm skin of normal human subjects measured with laser doppler velocimetry. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71(3):170–174. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.16231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan R, Park KC, Lee MH, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of a fixed triple combination (fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%, hydroquinone 4%, tretinoin 0.05%) compared with hydroquinone 4% cream in Asian patients with moderate to severe melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(3):697–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jamkhedkar P, Shenai C, Shroff HJ, et al. Fluticasone propionate (0.05%) cream compared to betamethasone valerate (0.12%) cream in the treatment of steroid-responsive dermatoses: a multicentric study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996;62(5):289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajaratnam R, Halpern J, Salim A, Emmett C. Interventions for melasma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(7):CD003583. (Epub 2010/07/09). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Taylor SC, Torok H, Jones T, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new triple-combination agent for the treatment of facial melasma. Cutis. 2003;72(1):67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torok H, Taylor S, Baumann L, et al. A large 12-month extension study of an 8-week trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of triple combination (TC) cream in melasma patients previously treated with TC cream or one of its dyads. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4(5):592–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torok HM. A comprehensive review of the long-term and short-term treatment of melasma with a triple combination cream. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(4):223–230. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nazzaro-Porro M. Azelaic acid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17(6):1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balina LM, Graupe K. The treatment of melasma. 20% azelaic acid versus 4% hydroquinone cream. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30(12):893–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb04362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Godse DK. Approach to melasma in India.Available from: http://www.academia.edu/3647500/approach_to_melasma_in_India. Accessed Sept 8, 2014.

- 45.Marta Rendon MB, Ivonne Arellano, Mauro Picardo, et.al. Treatment of melasma. Available from: http://leenyx.co.za/backend/media/54201093909AM/Treatment%20of%20melasma.pdf. Accessed Sept 8, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Sehgal VN, Verma P, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, Verma S. Melasma: treatment strategy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2011;13(6):265–279. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2011.630088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Majid I. Mometasone-based triple combination therapy in melasma: is it really safe? Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55(4):359–362. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.74545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rendon M, Berneburg M, Arellano I, Picardo M. Treatment of melasma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5 Suppl 2):S272–S281. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Godse KV, Zawar V. Mometasone menace in melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57(4):324–326. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.97686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu S, Shi H, Wu H, et al. Treatment of melasma with oral administration of tranexamic acid. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36(4):964–970. doi: 10.1007/s00266-012-9899-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kanechorn Na Ayuthaya P, Niumphradit N, Manosroi A, Nakakes A. Topical 5% tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma in Asians: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2012;14(3):150–154. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2012.685478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JH, Park JG, Lim SH, et al. Localized intradermal microinjection of tranexamic acid for treatment of melasma in Asian patients: a preliminary clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(5):626–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarkar R, Bansal S, Garg VK. Chemical peels for melasma in dark-skinned patients. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5(4):247–253. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.104912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grimes PE. The safety and efficacy of salicylic acid chemical peels in darker racial-ethnic groups. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(1):18–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarkar R, Kaur C, Bhalla M, Kanwar AJ. The combination of glycolic acid peels with a topical regimen in the treatment of melasma in dark-skinned patients: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(9):828–832. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang CC, Hui CY, Sue YM, Wong WR, Hong HS. Intense pulsed light for the treatment of refractory melasma in Asian persons. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(9):1196–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naito SK. Fractional photothermolysis treatment for resistant melasma in Chinese females. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2007;9(3):161–163. doi: 10.1080/14764170701418814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lim JT, Tham SN. Glycolic acid peels in the treatment of melasma among Asian women. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23(3):177–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1997.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Javaheri SM, Handa S, Kaur I, Kumar B. Safety and efficacy of glycolic acid facial peel in Indian women with melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40(5):354–357. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khunger N. Standard guidelines of care for chemical peels. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74(Suppl):S5–S12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rendon MI, Berson DS, Cohen JL, Roberts WE, Starker I, Wang B. Evidence and considerations in the application of chemical peels in skin disorders and aesthetic resurfacing. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3(7):32–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goel A, Krupashankar DS, Aurangabadkar S, Nischal KC, Omprakash HM, Mysore V. Fractional lasers in dermatology–current status and recommendations. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77(3):369–379. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.79732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goldberg DJ, Berlin AL, Phelps R. Histologic and ultrastructural analysis of melasma after fractional resurfacing. Lasers Surg Med. 2008;40(2):134–138. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rokhsar CK, Fitzpatrick RE. The treatment of melasma with fractional photothermolysis: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(12):1645–1650. doi: 10.2310/6350.2005.31302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tannous ZS, Astner S. Utilizing fractional resurfacing in the treatment of therapy-resistant melasma. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2005;7(1):39–43. doi: 10.1080/14764170510037752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trelles MA, Velez M, Gold MH. The treatment of melasma with topical creams alone, CO2 fractional ablative resurfacing alone, or a combination of the two: a comparative study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(4):315–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Na SY, Cho S, Lee JH. Intense pulsed light and low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment in melasma patients. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24(3):267–273. doi: 10.5021/ad.2012.24.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nouri K, Bowes L, Chartier T, Romagosa R, Spencer J. Combination treatment of melasma with pulsed CO2 laser followed by Q-switched alexandrite laser: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(6):494–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Angsuwarangsee S, Polnikorn N. Combined ultrapulse CO2 laser and Q-switched alexandrite laser compared with Q-switched alexandrite laser alone for refractory melasma: split-face design. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(1):59–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rockville. Appendix A How the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Grades Its Recommendations. The Guide to Clinical Preventive Services 2012: Recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2012. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK115122/. Accessed Sept, 9 2014.

- 71.Lin JY, Chan HH. Pigmentary disorders in Asian skin: treatment with laser and intense pulsed light sources. Skin Ther Lett. 2006;11(8):8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Godse KV, Sakhia J. Triple combination and glycolic acid peels in melasma in Indian patients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10(1):68–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2010.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grover C, Reddu BS. The therapeutic value of glycolic acid peels in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69(2):148–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cestari TF, Hexsel D, Viegas ML, et al. Validation of a melasma quality of life questionnaire for Brazilian Portuguese language: the MelasQoL-BP study and improvement of QoL of melasma patients after triple combination therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156(Suppl 1):13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pichardo R, Vallejos Q, Feldman SR, et al. The prevalence of melasma and its association with quality of life in adult male Latino migrant workers. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48(1):22–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ribas J, Schettini AP, Cavalcante Mde S. Exogenous ochronosis hydroquinone induced: a report of four cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85(5):699–703. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000500017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Monteiro RC, Kishore BN, Bhat RM, Sukumar D, Martis J, Ganesh HK. A comparative study of the efficacy of 4% hydroquinone vs 0.75% Kojic acid cream in the treatment of facial melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58(2):157. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.108070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Farshi S. Comparative study of therapeutic effects of 20% azelaic acid and hydroquinone 4% cream in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10(4):282–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Espinal-Perez LE, Moncada B, Castanedo-Cazares JP. A double-blind randomized trial of 5% ascorbic acid vs. 4% hydroquinone in melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(8):604–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nanda S, Grover C, Reddy BS. Efficacy of hydroquinone (2%) versus tretinoin (0.025%) as adjunct topical agents for chemical peeling in patients of melasma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(3):385–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Piquero Martin J, de Rothe Arocha J, Beniamini Loker D. Double-blind clinical study of the treatment of melasma with azelaic acid versus hydroquinone. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1988;16(6):511–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Verallo-Rowell VM, Verallo V, Graupe K, Lopez-Villafuerte L, Garcia-Lopez M. Double-blind comparison of azelaic acid and hydroquinone in the treatment of melasma. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1989;143:58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lim JT. Treatment of melasma using kojic acid in a gel containing hydroquinone and glycolic acid. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(4):282–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ferreira Cestari T, Hassun K, Sittart A, de Lourdes Viegas M. A comparison of triple combination cream and hydroquinone 4% cream for the treatment of moderate to severe facial melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6(1):36–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Grimes P, Kelly AP, Torok H, Willis I. Community-based trial of a triple-combination agent for the treatment of facial melasma. Cutis. 2006;77(3):177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rothe de Arocha J. Nuevas opciones en al tratamiento del melasma. Dermatologia Venezolana. 2003;41:11–4. Available from http://revista.svderma.org/index.php/ojs/article/view/285/285. Accessed Sept 9, 2014.

- 87.Sharquie KE, Al-Tikreety MM, Al-Mashhadani SA. Lactic acid as a new therapeutic peeling agent in melasma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(2):149–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sharquie KE, Al-Tikreety MM, Al-Mashhadani SA. Lactic acid chemical peels as a new therapeutic modality in melasma in comparison to Jessner’s solution chemical peels. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(12):1429–1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kalla G, Garg A, Kachhawa D. Chemical peeling–glycolic acid versus trichloroacetic acid in melasma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2001;67(2):82–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Khunger N, Sarkar R, Jain RK. Tretinoin peels versus glycolic acid peels in the treatment of Melasma in dark-skinned patients. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(5):756–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Griffiths CE, Finkel LJ, Ditre CM, Hamilton TA, Ellis CN, Voorhees JJ. Topical tretinoin (retinoic acid) improves melasma. A vehicle-controlled, clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129(4):415–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jimbow K. N-acetyl-4-S-cysteaminylphenol as a new type of depigmenting agent for the melanoderma of patients with melasma. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127(10):1528–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Taylor MB. Summary of mandelic acid for the improvement of skin conditions. Cosmet Dermatol. 1999;12:26–8.

- 94.Kumari R, Thappa DM. Comparative study of trichloroacetic acid versus glycolic acid chemical peels in the treatment of melasma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76(4):447. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.66602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grimes PE. Melasma. Etiologic and therapeutic considerations. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131(12):1453–1457. doi: 10.1001/archderm.131.12.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sobhi RM, Sobhi AM. A single-blinded comparative study between the use of glycolic acid 70% peel and the use of topical nanosome vitamin C iontophoresis in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11(1):65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Safoury OS, Zaki NM, El Nabarawy EA, Farag EA. A study comparing chemical peeling using modified Jessner’s solution and 15% trichloroacetic Acid versus 15% trichloroacetic acid in the treatment of melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54(1):41–45. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.48985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Berardesca E, Cameli N, Primavera G, Carrera M. Clinical and instrumental evaluation of skin improvement after treatment with a new 50% pyruvic acid peel. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(4):526–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dogra S, Kanwar AJ, Parsad D. Adapalene in the treatment of melasma: a preliminary report. J Dermatol. 2002;29(8):539–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Leenutaphong V, Nettakul A, Rattanasuwon P. Topical isotretinoin for melasma in Thai patients: a vehicle-controlled clinical trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 1999;82(9):868–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yoshimura K, Harii K, Aoyama T, Iga T. Experience with a strong bleaching treatment for skin hyperpigmentation in Orientals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(3):1097–1108. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200003000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kauh YC, Zachian TF. Melasma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:491–499. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4857-7_72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Torok HM, Jones T, Rich P, Smith S, Tschen E. Hydroquinone 4%, tretinoin 0.05%, fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%: a safe and efficacious 12-month treatment for melasma. Cutis. 2005;75(1):57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Garcia A, Fulton JE., Jr The combination of glycolic acid and hydroquinone or kojic acid for the treatment of melasma and related conditions. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22(5):443–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Guevara IL, Pandya AG. Safety and efficacy of 4% hydroquinone combined with 10% glycolic acid, antioxidants, and sunscreen in the treatment of melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(12):966–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2003.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marta R, Mark B, Ivonne A, Mauro P. Treatment of melasma. 2006. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK115122/. Accessed Sept 9, 2014.

- 107.Huh CH, Seo KI, Park JY, Lim JG, Eun HC, Park KC. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of vitamin C iontophoresis in melasma. Dermatology. 2003;206(4):316–320. doi: 10.1159/000069943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cuce LC, Bertino MC, Scattone L, Birkenhauer MC. Tretinoin peeling. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27(1):12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cotellessa C, Peris K, Onorati MT, Fargnoli MC, Chimenti S. The use of chemical peelings in the treatment of different cutaneous hyperpigmentations. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(6):450–454. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kopera D, Hohenleutner U. Ruby laser treatment of melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21(11):994. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1995.tb00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee GY, Kim HJ, Whang KK. The effect of combination treatment of the recalcitrant pigmentary disorders with pigmented laser and chemical peeling. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(12):1120–1123. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Manaloto RM, Alster T. Erbium:YAG laser resurfacing for refractory melasma. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(2):121–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kunachak S, Leelaudomlipi P, Wongwaisayawan S. Dermabrasion: a curative treatment for melasma. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2001;25(2):114–117. doi: 10.1007/s002660010107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Montemarano AD. Melasma Treatment and Management.Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1068640-treatment. Accessed Sept, 9 2014.

- 115.Park KY, Kim DH, Kim HK, Li K, Seo SJ, Hong CK. A randomized, observer-blinded, comparison of combined 1,064-nm Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium-aluminium-garnet laser plus 30% glycolic acid peel vs. laser monotherapy to treat melasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36(8):864–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.