Abstract

Introduction

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) is an antioxidant that has multiple biologic effects including antimicrobial properties. Acne vulgaris is a disease of the pilosebaceous unit, characterized by an inflammatory host immune response to the bacteria Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes). This study sought to determine whether resveratrol may be a potential treatment for acne vulgaris.

Methods

Colony-forming unit (CFU) assays together with transmission electron microscopy using P. acnes treated with resveratrol or benzoyl peroxide were used to assess antibacterial effects. Blood was drawn from healthy human volunteers, and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assays were used to assess cytotoxicity in monocytes and keratinocytes.

Results

Resveratrol demonstrated sustained antibacterial activity against P. acnes, whereas benzoyl peroxide, a commonly used antibacterial treatment for acne, demonstrated a short-term bactericidal response. A combination of resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide showed high initial antibacterial activity and sustained bacterial growth inhibition. Electron microscopy of P. acnes treated with resveratrol revealed altered bacterial morphology, with loss of membrane definition and loss of well-defined extracellular fimbrial structures. Resveratrol was less cytotoxic than benzoyl peroxide.

Conclusion

The sustained antibacterial activity and reduced cytotoxicity versus benzoyl peroxide demonstrated by resveratrol in this study highlight its potential as a novel therapeutic option or adjuvant therapy in the treatment of acne vulgaris.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13555-014-0063-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris, Antibacterial, Benzoyl peroxide, Dermatology, Propionibacteriumacnes, Resveratrol

Introduction

Acne is the most prevalent skin disease in the world, affecting 85% of adolescents and over 10% of adults [1]. In the USA, it represents a tremendous economic burden with total costs exceeding $3 billion per year [2]. Antibiotics are efficient against sensitive Propionibacterium acnes, but resistance has developed due to monotherapy and overuse [3]. Other treatments such as retinoids and benzoyl peroxide are limited by patient compliance due to undesirable side effects such as irritation [4]. Benzoyl peroxide is highly effective as an antimicrobial in vitro [5] and in vivo [6], and it is a first-line drug for the treatment of acne due to its direct bactericidal and comedolytic properties. Although no known bacterial resistance has been reported to benzoyl peroxide [7, 8], its side effects still limit its use. Thus, the need exists for new efficacious treatments with fewer side effects. Already, newer topical combination therapies have been developed to reduce the concentration of benzoyl peroxide through its combination with other anti-acne compounds [9].

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) may be a useful anti-acne treatment. It is a potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compound that has been shown to have antineoplastic and wound-healing activities [10]. It has been demonstrated to inhibit inflammatory markers activation protein-1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB), both of which have been implicated in the formation of inflammatory acne lesions [11]. Resveratrol is also antimicrobial, demonstrating antiviral, antifungal, antibacterial, and antiprotozoal activity [12–14], and has been shown to inhibit keratinocyte proliferation, which contributes to follicular obstruction in the formation of acne lesions [15]. Few studies have evaluated resveratrol’s application as a treatment for acne vulgaris, although one clinical study has previously demonstrated the potential efficacy of resveratrol in the treatment of acne vulgaris [16]. Additionally, an in vitro study showed that resveratrol has antimicrobial activity against P. acnes [17].

The present study further investigated the potential of resveratrol as a treatment for acne. It sought to determine the in vitro effects of resveratrol on P. acnes growth and survival, while further assessing the antimicrobial mechanism of action of resveratrol and its cytotoxic effects. It also determined the efficacy of utilizing resveratrol as part of a combination therapy with benzoyl peroxide.

Methods

Reagents

Resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted to 1% DMSO in experiments, to minimize the effect of DMSO.

Colony-Forming Unit assay

Antibacterial activity of resveratrol was determined by colony-forming unit (CFU) assays. P. acnes ATCC (American type cell culture) strain 6919 (a ribotype 1 [18] MLST4 1A1 strain [19]) was grown anaerobically at 37 °C in reinforced clostridial media (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) for 3 days and collected in the late exponential phase of growth by centrifugation. Bacteria were washed with pH 7 sodium phosphate buffer supplemented by 0.03% trypticase soy media and quantified by reading with a spectrophotometer at 600 nm and applying a conversion of 1 × 108 bacteria = 1 absorbance unit. Approximately, 1.33 × 106 CFUs of bacteria were then added to 1 mL reinforced clostridial media. Samples were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C, with aliquots periodically withdrawn and plated on brucella agar with 5% sheep blood supplemented with hemin and vitamin K (Remel, Lenexa, KS, USA). Plates were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 3 days, and individual P. acnes colonies were counted to determine the concentration.

Electron Microscopy

Propionibacterium acnes at 107 CFU/mL were incubated with either 1 mg/mL of resveratrol or benzoyl peroxide for 24 h. Bacteria were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in PBS with 2% glutaraldehyde. Samples were fixed for 5 min with 0.05% OsO4, dehydrated in graded ethanol, and embedded in Eponate 12 (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA). A Reichert-Jung Ultracut E ultramicrotome™ (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) was used to cut 60–70 nm slices which were picked up on formvar-coated copper grids. Uranyl acetate and Reynolds lead citrate were used for staining, and stained samples were visualized at 80 kV on a JEOL 100CX electron microscope™ (Peabody, MI, USA).

MTS Assay

Blood was drawn from healthy human volunteers recruited by the laboratory with no skin conditions, including acne, and who had not suffered any illness within 2 weeks of the blood draw date. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by use of a Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia, New York, NY, USA) gradient and allowed to adhere for 2 h in RPMI media (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA, USA) in 96-well plates (Costar, Tewksbury, MA, USA). Cells were washed 3× with Roswell Park Memorial Park Institute (RPMI) media to obtain adherent monocytes. Monocytes were then incubated at 37 °C in 100 μL RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS. The HaCaT cell line of human keratinocytes was cultured in 100 μL HaCaT media and incubated at 37 °C in 96-well plates (Costar). To evaluate human monocyte and human keratinocyte viability after incubation with resveratrol or benzoyl peroxide, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) cytotoxicity assays were performed. After 16 h of incubation with resveratrol or benzoyl peroxide, 20 μL MTS assay reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added to each well, and the monocyte and keratinocyte cells were allowed to incubate for ~4 h at 37 °C. The 490 nm absorbance of each well was then determined using a microtiter plate reader, with absorbance proportional to the number of viable monocyte and keratinocyte cells in each treatment, as previously described [20]. Student’s T test was used for statistical analysis to determine if differences between resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide-treated cells were significant.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Study protocol for withdrawal of blood from healthy volunteers was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angles. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Results

Resveratrol has Antibacterial Activity Against P. acnes

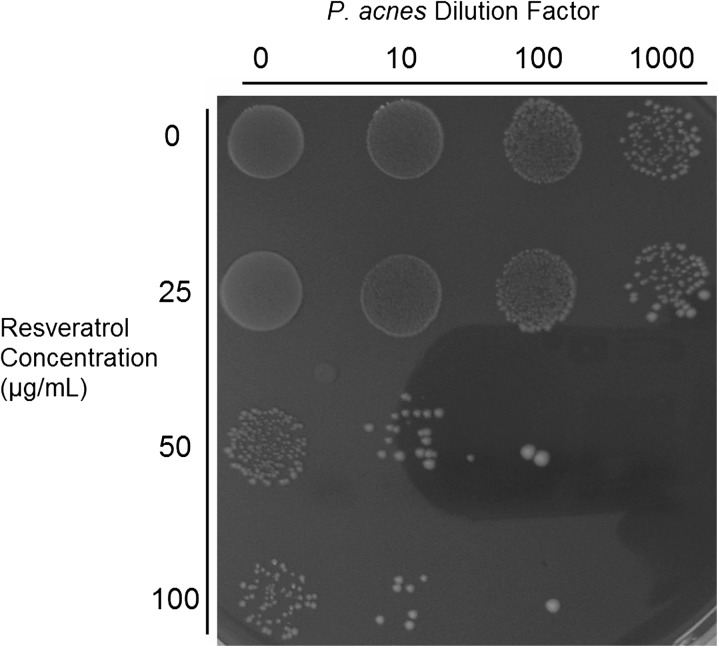

The effect of resveratrol on P. acnes growth was visually demonstrated by incubating P. acnes bacteria with various concentrations of resveratrol for 48 h in reinforced clostridial media before spot plating. At a concentration of at least 50 μg/mL, resveratrol demonstrated significant inhibition of P. acnes growth (Fig. 1). Resveratrol at 25 μg/mL had only a small inhibitory effect.

Fig. 1.

Resveratrol has antimicrobial activity against P. acnes. Propionibacterium acnes was incubated with various concentrations of resveratrol for 48 h and plated at different dilutions demonstrating reduced bacterial colony count at higher concentrations of resveratrol

Resveratrol and Benzoyl Peroxide have Different Antibacterial Characteristics

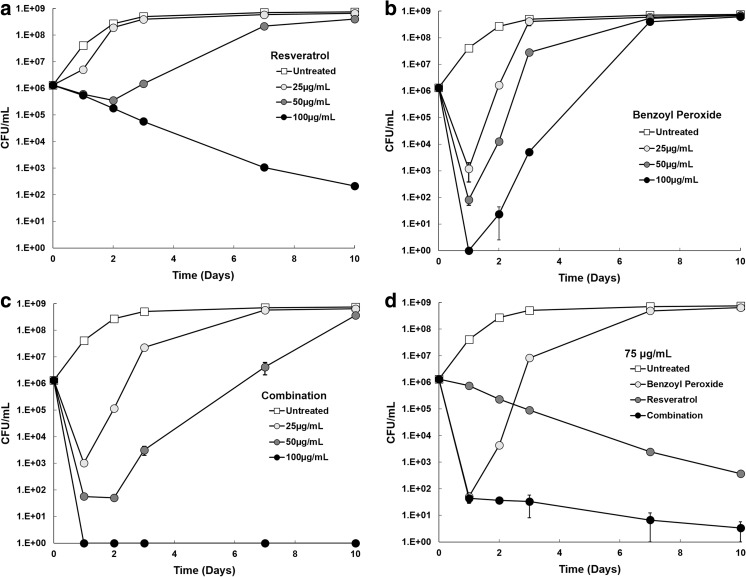

To determine the antibacterial kinetics of resveratrol, benzoyl peroxide, and a combination of both on P. acnes growth, P. acnes was incubated with these treatments in reinforced clostridial media, and the concentration of bacteria was determined after 1, 2, 3, 7, and 10 days. Resveratrol demonstrated low bactericidal activity, but significant and sustained growth inhibition at concentrations of 100 μg/mL and shorter term growth inhibition at 50 μg/mL (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Antimicrobial effects of resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide over time. P. acnes was incubated in reinforced clostridial media in the presence of resveratrol (a), benzoyl peroxide (b), or a combination of both treatments (c). Aliquots were removed at several time points and plated in triplicate to determine the number of CFUs. A comparison of each treatment group at 75 µg/mL is also displayed (d). CFU colony-forming unit

In contrast, benzoyl peroxide demonstrated significant differences in bactericidal kinetics when compared to resveratrol. High bactericidal activity was noted initially, but there was no antibacterial activity observed after the first 24 h (Fig. 2b). P. acnes recovered from benzoyl peroxide treatment and achieved maximum growth rate by the second day, irrespective of benzoyl peroxide concentration. Results from the combination therapy of resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide reflected the antibacterial kinetics of each individual treatment (Fig. 2c). As demonstrated with benzoyl peroxide alone, the combination treatment showed high initial antibacterial activity. Combination treatment also demonstrated the longer term inhibitory effects shown by resveratrol monotherapy. Combination therapy, therefore, resulted in a much lower concentration of P. acnes over the course of the study than with either treatment alone.

A comparison of each treatment group at a concentration of 75 μg/mL highlighted the short-term bactericidal activity of benzoyl peroxide, the sustained inhibitory activity of resveratrol, and the enhanced activity of resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide combination therapy (Fig. 2d).

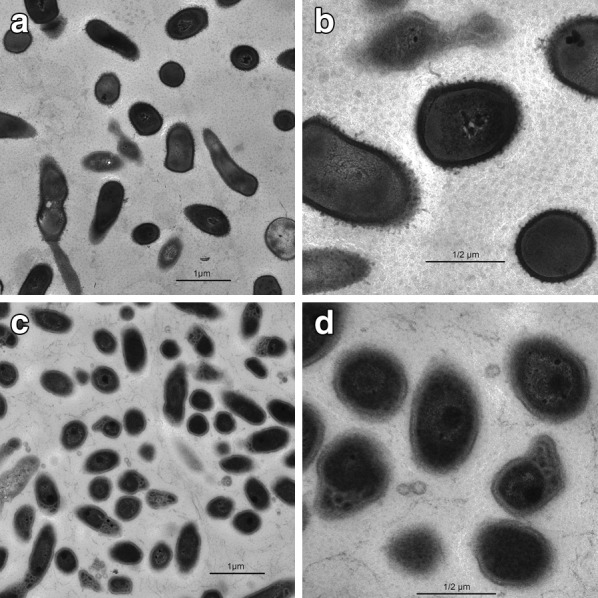

Resveratrol Alters the Membrane and Structure of P. acnes

To further investigate the mechanism by which resveratrol inhibits P. acnes growth, this study examined the bacterium using transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 3). Structural alterations were noted in the bacteria treated with resveratrol, with loss of membrane definition due to intramembranous edema and loss of well-defined extracellular fimbrial structures. Intracellular buildup of a dense substance was also found in some bacteria treated with resveratrol.

Fig. 3.

Electron microscopy demonstrating antimicrobial effect of resveratrol. Electron microscopy images of P. acnes left untreated (a, b) or incubated for 24 h (c, d) with resveratrol. Images were taken at ×10,000 magnification (a, c) or ×29,000 magnification (b, d). Scale bar is 1 µm (a, c) or 1/2 µm (b, d)

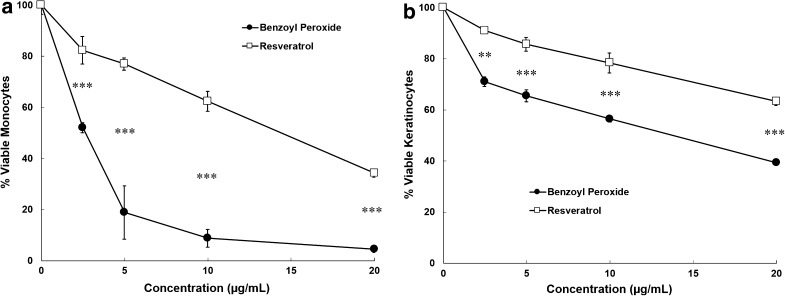

Resveratrol has Lower Cytotoxicity than Benzoyl Peroxide to Human Monocytes and Keratinocytes

This study evaluated the cytotoxic effects of benzoyl peroxide compared to resveratrol via the MTS assay for human monocytes (Fig. 4a) and keratinocytes (Fig. 4b). Benzoyl peroxide was significantly more toxic than resveratrol to monocytes (p < 0.001 for all concentrations tested, Student’s t test), resulting in over 90% cell death at 10 μg/mL, while resveratrol resulted in less than 40% cell death at the same concentration. These effects were less pronounced in keratinocytes (p < 0.01 for all concentrations tested, Student’s t test), where both compounds had lower cytotoxicity. Nonetheless, benzoyl peroxide treatment resulted in 20–30% more cell death at all concentrations tested in keratinocytes.

Fig. 4.

Cytotoxicity of benzoyl peroxide and resveratrol. Primary human monocytes (a) or keratinocytes (b) were incubated with resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide for 16 h. The percentages of viable cells were assessed in triplicate by MTS assay. Statistics show comparison between resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide group at each concentration by Student’s t test, **(p < 0.01), ***(p < 0.001)

Discussion

Acne vulgaris is the most common skin disease, affecting millions of people worldwide [21].

Unfortunately, bacterial antibiotic resistance and severe side effects limit the efficacy of current treatments [22].

Resveratrol has a favorable safety profile and is an anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial compound. Thus, this study investigated the potential of resveratrol as an antibacterial agent for the treatment for acne vulgaris.

The results from this study demonstrated the strong antibacterial activity of resveratrol at concentrations of at least 50 μg/mL (Fig. 1). These findings are consistent with prior studies which have demonstrated inhibition of P. acnes biofilm formation at slightly higher concentrations of 200 μg/mL [23]. By further investigating the nature of this antibacterial activity, we found that resveratrol is bacteriostatic in nature, possessing strong inhibitory activity that limits the growth of P. acnes (Fig. 2a). Its bactericidal activity was relatively weak in terms of reduction of viable bacteria, but the antibacterial activity was sustained over time. This indicates that resveratrol creates a gradual disruption of normal bacterial cellular function, resulting in cell death over a period of several days. Our findings suggest that resveratrol reaches a critical concentration around 50–75 μg/mL, at which point a threshold for major growth inhibition is passed and resveratrol becomes bactericidal for a sustained period. In contrast, benzoyl peroxide’s bactericidal activity was strong initially, but was not sustained beyond the first 24 h (Fig. 2b). This is in accordance with benzoyl peroxide’s mechanism of action, whereby free radicals are formed via symmetrical fission, resulting in a short half-life [24].

When both resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide were combined, benzoyl peroxide’s strong bactericidal effect coupled with resveratrol’s high inhibitory activity resulted in low levels of bacteria throughout the experiment (Fig. 2c). Thus, this combination shows promise for clinical treatment of acne vulgaris.

Electron microscopy of P. acnes treated with resveratrol revealed altered bacterial morphology, with the bacteria displaying intramembranous edema and disrupted intracellular structural integrity (Fig. 3). As a membrane permeable compound, this innate characteristic of resveratrol may allow it to alter the bacterial membrane structure of P. acnes and disrupt intracellular machinery.

Benzoyl peroxide was found to be highly cytotoxic to monocytes and keratinocytes, potentially explaining the irritation found with topical benzoyl peroxide regimens (Fig. 4). Resveratrol was significantly less cytotoxic, which may translate to decreased irritation in vivo. A pilot study investigating topical resveratrol treatment in acne found no cutaneous side effects from resveratrol [16]. Additionally, one study demonstrated that macrophages treated with resveratrol maintained viability via a toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-dependant mechanism if also treated with lipopolysaccharide [25], indicating that resveratrol may be less cytotoxic to cells in the presence of P. acnes.

A combination therapy of resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide may allow for a significant reduction of the benzoyl peroxide concentration compared to current benzoyl peroxide-based treatments, minimizing side effects. However, this study was in vitro, which does not necessarily translate to success in the clinic. Concentrations used in vitro may not accurately reflect effective in vivo concentrations necessary for the treatment of acne vulgaris. In vivo studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide in combination for the treatment of acne vulgaris.

Conclusion

Resveratrol’s anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties demonstrated here in vitro may address some of the pathogenic mechanisms in the formation of acne. Already, clinical studies have shown the beneficial effects of resveratrol in the treatment of acne [16]. However, acne is a multifactorial disease, attributed also to sebum production [26], which is not currently known to be addressed by resveratrol, and which may therefore limit its use as a monotherapy in the treatment of acne. Since resveratrol and benzoyl peroxide operate with different antibacterial kinetics and mechanisms, they may complement each other in a combination treatment in vivo, leading to enhanced clinical outcomes. Overall, the data in this study indicates that resveratrol may be a novel therapeutic option or useful adjuvant therapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the Women’s Dermatologic Society Academic Research Grant for funding this study as well as to Ami Oren, Marianne Cilluffo, Nathalie Fernando, Julie Patel, and Elaheh Salehi for their invaluable contributions to data collection and analysis. This study and the article processing charges were supported in part by the Women’s Dermatologic Society Academic Research Grant and NIH R01 AR053542. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given final approval for the version to be published. This study was supported in part by the Women’s Dermatologic Society Academic Research Grant and NIH R01 AR053542.

Conflict of interest

J Kim has consulted for Allergan, LeoPharma, Anacor, and TPG. E.J.M. Taylor, Y. Yu, J. Champer declare no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Study protocol for withdrawal of blood from healthy volunteers was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angles. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.James WD. Clinical practice. Acne. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1463–1472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp033487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bickers DR, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leyden JJ, et al. Propionibacterium acnes resistance to antibiotics in acne patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:41–45. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(83)70005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman SR, Chen DM. How patients experience and manage dryness and irritation from acne treatment. JDD. 2011;10:605–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cove JH, Holland KT. The effect of benzoyl peroxide on cutaneous micro-organisms in vitro. J Appl Bacteriol. 1983;54:379–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1983.tb02631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bojar RA, Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT. The short-term treatment of acne vulgaris with benzoyl peroxide: effects on the surface and follicular cutaneous microflora. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:204–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb05014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fulton JE, Jr, Farzad-Bakshandeh A, Bradley S. Studies on the mechanism of action to topical benzoyl peroxide and vitamin A acid in acne vulgaris. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:191–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1974.tb00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh N, Aggarwal S. Benzoyl peroxide modulates gene expression by epigenetic mechanism in mouse epidermal JB6 cells. Ind J Exp Biol. 1996;34:647–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grove G, Zerweck C, Gwazdauskas J. Tolerability and irritation potential of four topical acne regimens in healthy subjects. JDD. 2013;12:644–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baur JA, Sinclair DA. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:493–506. doi: 10.1038/nrd2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A, Negi G, Sharma SS. Neuroprotection by resveratrol in diabetic neuropathy: concepts & mechanisms. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:4640–4645. doi: 10.2174/09298673113209990151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Docherty JJ, Smith JS, Fu MM, Stoner T, Booth T. Effect of topically applied resveratrol on cutaneous herpes simplex virus infections in hairless mice. Antiviral Res. 2004;61:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan MM. Antimicrobial effect of resveratrol on dermatophytes and bacterial pathogens of the skin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:99–104. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(01)00886-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kedzierski L, Curtis JM, Kaminska M, Jodynis-Liebert J, Murias M. In vitro antileishmanial activity of resveratrol and its hydroxylated analogues against Leishmania major promastigotes and amastigotes. Parasitol Res. 2007;102:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0729-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holian O, Walter RJ. Resveratrol inhibits the proliferation of normal human keratinocytes in vitro. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2001;36:55–62. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fabbrocini G, et al. Resveratrol-containing gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a single-blind, vehicle-controlled, pilot study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:133–141. doi: 10.2165/11530630-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Docherty JJ, McEwen HA, Sweet TJ, Bailey E, Booth TD. Resveratrol inhibition of Propionibacterium acnes. J Antimicrob Chemotherapy. 2007;59:1182–1184. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitz-Gibbon S, et al. Propionibacterium acnes strain populations in the human skin microbiome associated with acne. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2152–2160. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDowell A, Nagy I, Magyari M, Barnard E, Patrick S. The opportunistic pathogen Propionibacterium acnes: insights into typing, human disease, clonal diversification and CAMP factor evolution. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e70897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capasso JM, Cossio BR, Berl T, Rivard CJ, Jimenez C. A colorimetric assay for determination of cell viability in algal cultures. Biomol Eng. 2003;20:133–138. doi: 10.1016/S1389-0344(03)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeichner JA. Evaluating and treating the adult female patient with acne. JDD. 2013;12:1416–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowe WP. Antibiotic resistance and acne: where we stand and what the future holds. JDD. 2014;13:s66–s70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coenye T, et al. Eradication of Propionibacterium acnes biofilms by plant extracts and putative identification of icariin, resveratrol and salidroside as active compounds. Phytomed: Int J Phytotherapy Phytopharmacol. 2012;19:409–412. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chellquist EM, Gorman WG. Benzoyl peroxide solubility and stability in hydric solvents. Pharm Res. 1992;9:1341–1346. doi: 10.1023/A:1015873805080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radkar V, Lau-Cam C, Hardej D, Billack B. The role of surface receptor stimulation on the cytotoxicity of resveratrol to macrophages. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:3664–3670. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McInturff JE, Kim J. The role of toll-like receptors in the pathophysiology of acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2005;24:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.