Abstract

Hip fractures are common, morbid, costly, and associated with subsequent fractures. Historically, postfracture osteoporosis medication use rates have been poor, but have not been recently examined in a large-scale study. We conducted a retrospective, observational cohort study based on U.S. administrative insurance claims data for beneficiaries with commercial or Medicare supplemental health insurance. Eligible participants were hospitalized for hip fracture between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011, and aged 50 years or older at admission. The outcome of interest was osteoporosis medication use within 12 months after discharge. Patients were censored after 12 months, loss to follow-up, or a medical claim for cancer or Paget's disease, whichever event occurred first. During the study period, 96,887 beneficiaries met the inclusion criteria; they had a mean age of 80 years and 70% were female. A total of 34,389 (35.5%) patients were censored before reaching 12 months of follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier estimated probability of osteoporosis medication use within 12 months after discharge was 28.5%. The rates declined significantly from 40.2% in 2002, to 20.5% in 2011 (p for trend <0.001). In multivariable Cox proportional hazards models, a number of patient characteristics were associated with reduced likelihood of osteoporosis medication use, including older age and male gender. However, the predictor most strongly and most positively associated with osteoporosis medication use after fracture was osteoporosis medication use before the fracture (hazard ratio = 7.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 7.23–7.69). Most patients suffering a hip fracture do not use osteoporosis medication in the subsequent year and treatment rates have worsened. © 2014 Eli Lilly and Company. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Keywords: OSTEOPOROSIS, TREATMENT PATTERNS, HIP FRACTURE

Introduction

Older adults fear hip fractures, and for good reason.1 Rates of hip fracture increase with age and are associated with substantial morbidity, loss of independence, and an approximate 25% mortality rate 1 year after the fracture and extending up to 10 years postfracture.2–5 Most patients who suffer a hip fracture and subsequently undergo bone mineral density assessment have low bone mass, and approximately 10% of those who sustain a hip fracture experience a repeat hip fracture within 1 to 5 years.6–8

The 2013 National Osteoporosis Foundation Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis stipulates that individuals with a hip fracture should be considered for treatment with U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved osteoporosis medication.9 Over the last decade, several U.S.-based reports have noted a gap in osteoporosis treatment rates after hip fracture, with less than one-third receiving treatment.10,11 During this same period, several studies showed an encouraging reduction in hip fracture rates.12,13 These trends have occurred during a time when several new treatments for osteoporosis have become available, broadening the therapeutic armamentarium to include medications with different mechanisms of action, routes of administration, and dosing frequencies; this enables clinicians to select a treatment individualized to the osteoporosis patient's preferences and needs. In addition, during the last decade, The American Orthopaedic Association has focused attention on postfracture care with the Own the Bone program, whereas the National Bone Health Alliance and the Fragility Fracture Network formed to help reduce the treatment gap that exists in patients who have sustained a hip fracture and other fragility fractures.

The objective of this study was to examine the trends in and correlates of osteoporosis medication use in a large cohort of U.S. patients hospitalized for hip fracture over the period 2002 to 2011. Analyses examined treatment rates by year and across different U.S. Census Bureau regions.

Materials and Methods

Overview of study design

This study was a retrospective, observational cohort study based on U.S. administrative insurance claims data for a non-probability sample of beneficiaries with commercial or Medicare supplemental health insurance. Patients hospitalized for hip fracture between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011, were followed for up to 12 months after hospital discharge to identify whether or not they had been prescribed a medication indicated for osteoporosis.

Data and setting

The setting of this study was routine U.S. clinical practice, as reflected by the administrative insurance claims data contained in the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (Commercial) and Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits (Medicare Supplemental) databases (Truven Health, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). These databases represent a non-probability (convenience) sample and comprise enrollment information, inpatient and outpatient medical, and outpatient pharmacy claims data for individuals with employer-sponsored primary or Medicare supplemental health insurance. These databases have been used in published epidemiologic evaluations related to osteoporosis.14

The study databases satisfy the conditions set forth in Sections 164.514 (a)-(b)1ii of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 privacy rule regarding the determination and documentation of statistically deidentified data. Because this study used only deidentified patient records and does not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, Institutional Review Board approval to conduct this study was not necessary.

As described in greater detail in the following three sections, study variables were measured from the database using enrollment records, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, Current Procedural Technology 4th edition (CPT-4) codes, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes, and National Drug Codes (NDCs), as appropriate.15

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were included in the study cohort if they were hospitalized for hip fracture between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011, as evidenced by at least one acute care hospital inpatient medical claim with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for a closed hip fracture and at least one medical claim for a hip fracture repair procedure within 14 days of the inpatient medical claim. The date of admission for the first observed hip fracture hospitalization during this time period was designated as the index date. Patients were further required to have 6 months of continuous insurance plan enrollment prior to the index date. This 6-month period was designated the baseline period. Patients were excluded from the study if they had administrative claims-based evidence of cancer (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancers) or Paget 's disease during the baseline period, if they were <50 years old at the index date, or if they had missing geographic information. The lists of codes and additional information on criteria used in patient selection are available in Supporting Table 1.

Outcomes

The study outcome was osteoporosis medication use within the 12-month period after discharge from hip fracture hospitalization. Osteoporosis medications use was defined as the occurrence of at least one medical or pharmacy claim for a bisphosphonate (oral and parenteral), calcitonin, denosumab, hormone replacement therapy (HRT), raloxifene, or teriparatide. Time to osteoporosis medication use was measured as the number of days from discharge until the first observed claim for osteoporosis medication, or censoring at 12 months after discharge, disenrollment from the health insurance plan, reaching the study end date of June 30, 2012, or the appearance of a claim for cancer or Paget's disease, whichever event occurred first.

Potential predictors

The study covariates included patient demographics and clinical characteristics thought to potentially predict the likelihood of osteoporosis medication use. Patient demographics were measured at the index and patient clinical characteristics were measured throughout the baseline period. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are and are listed in Table 1. The lists of codes and additional information on criteria used to measure the study covariates are available in Supporting Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| All patients (n = 96,887) | Used osteoporosis medication ≤12 months after discharge (n = 23,250) | Did not use osteoporosis medication ≤12 months after discharge (n = 73,637) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 80.1 ± 10.6 | 78.7 ± 10.3 | 80.6 ± 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Patients in age group, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 50–59 years | 5,883 (6.1) | 1,509 (6.5) | 4,374 (5.9) | |

| 60–69 years | 9,957 (10.3) | 2,837 (12.2) | 7,120 (9.7) | |

| 70–79 years | 21,065 (21.7) | 5,852 (25.2) | 15,213 (20.7) | |

| ≥80 years | 59,982 (61.9) | 13,052 (56.1) | 46,930 (63.7) | |

| Patients, female, n (%) | 68,090 (70.3) | 20,630 (88.7) | 47,460 (64.5) | <0.001 |

| Patients residing in urban area, n (%)b | 81,421 (84.0) | 19,588 (84.2) | 61,833 (84.0) | 0.31 |

| Patients in health plan by type, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Fee for service | 46,051 (47.5) | 11,689 (50.3) | 34,362 (46.7) | |

| HMO | 16,664 (17.2) | 3,624 (15.6) | 13,040 (17.7) | |

| POS | 2,246 (2.3) | 554 (2.4) | 1,692 (2.3) | |

| PPO | 28,824 (29.8) | 6,811 (29.3) | 22,013 (29.9) | |

| Otherc | 1,053 (1.1) | 257 (1.1) | 796 (1.1) | |

| Unknown | 2,049 (2.1) | 315 (1.4) | 1,734 (2.4) | |

| Patients with comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Alcoholism | 547 (0.6) | 90 (0.4) | 457 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 9,131 (9.4) | 1,887 (8.1) | 7,244 (9.8) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 11,650 (12.0) | 2,804 (12.1) | 8,846 (12.0) | 0.847 |

| Congestive heart failure | 8,137 (8.4) | 1,326 (5.7) | 6,811 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 3,184 (3.3) | 454 (2.0) | 2,730 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes with or without sequelae | 14,939 (15.4) | 2,854 (12.3) | 12,085 (16.4) | <0.001 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 536 (0.6) | 87 (0.4) | 449 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Mild liver disease | 413 (0.4) | 97 (0.4) | 316 (0.4) | 0.808 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 217 (0.2) | 38 (0.2) | 179 (0.2) | 0.025 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1,562 (1.6) | 256 (1.1) | 1,306 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Osteodystrophy | 14 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | 12 (0.0) | 0.395 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 626 (0.6) | 132 (0.6) | 494 (0.7) | 0.087 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 4,109 (4.2) | 792 (3.4) | 3,317 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 4,540 (4.7) | 615 (2.6) | 3,925 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 2,308 (2.4) | 1,048 (4.5) | 1,260 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 6,207 (6.4) | 2,762 (11.9) | 3,445 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Patients with medications, n (%) | ||||

| Glucocorticoids (≥5 mg for ≥90 days) | 914 (0.9) | 363 (1.6) | 551 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 7,253 (7.5) | 1,582 (6.8) | 5,671 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| Hormone deprivation therapy | 1,014 (1.0) | 180 (0.8) | 834 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Anticonvulsants | 9,854 (10.2) | 2,790 (12.0) | 7,064 (9.6) | <0.001 |

| Immunosuppressants | 939 (1.0) | 443 (1.9) | 496 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Strong opioids | 8,292 (8.6) | 2,531 (10.9) | 5,761 (7.8) | <0.001 |

| Weak opioids | 25,082 (25.9) | 7,661 (33.0) | 17,421 (23.7) | <0.001 |

| Non-opioid analgesics | 14,490 (15.0) | 4,856 (20.9) | 9,634 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| Teriparatide | 337 (0.3) | 266 (1.1) | 71 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Bisphosphonates | 12,487 (12.9) | 9,101 (39.1) | 3,386 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| Denosumab | 8 (0.0) | 6 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Calcitonin | 2,045 (2.1) | 1,402 (6.0) | 643 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 2,528 (2.6) | 1,923 (8.3) | 605 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Raloxifene | 1,804 (1.9) | 1,405 (6.0) | 399 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Patients with fragility fracture, n (%) | 15,623 (16.1) | 4,144 (17.8) | 11,479 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| Deyo-CCI, mean ± SD | 0.85 ± 1.29 | 0.7 ± 1.11 | 0.9 ± 1.33 | <0.001 |

| Unique three-digit ICD-9-CM codes, mean ± SD | 5.8 ± 4.8 | 6.0 ± 4.6 | 5.7 ± 4.8 | <0.001 |

| Unique National Drug Codes, mean ± SD | 8.2 ± 6.7 | 9.8 ± 6.7 | 7.7 ± 6.6 | <0.001 |

| Patients with bone density test, n (%) | 3,690 (3.8) | 1,473 (6.3) | 2,217 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Patients with inpatient admission, n (%) | 13,034 (13.5) | 2,742 (11.8) | 10,292 (14.0) | <0.001 |

| Patients with office visit to any specialist, n (%) | 85,793 (88.5) | 21,231 (91.3) | 64,562 (87.7) | <0.001 |

Patient demographics measured at index; patient clinical characteristics measured throughout baseline period.

HMO = health maintenance organization; POS = point of service; PPO = preferred provider organization; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification.

Value of p corresponds to comparison between patients using versus not using osteoporosis medication within 12 months after discharge.

Residence in an urban area is defined as residence in a Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Other health plans types are as follows: exclusive provider organization, consumer-directed health plan, and high-deductible health plan.

Statistical analyses

Bivariate analyses were used to display summaries of variable distributions, stratified by patients who had used osteoporosis medication within 12 months after discharge versus patients who had not. The Kaplan-Meier product-limit method of survival analysis was used to visually depict the distribution of time to osteoporosis medication use.16 Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to characterize the association between time to osteoporosis medication use and all measured patient demographics and clinical characteristics listed in Table 1.17 The variance inflation factor was used to assess multicollinearity of the models' independent variables.18 The Schoenfeld test assessed whether the models' independent variables met the proportionality assumption of the Cox proportional hazards modeling approach.19 All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Values of p <0.05 were considered, a priori, to be statistically significant.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the impact of excluding patients who were censored before 12 months after discharge had elapsed. Thus, a subanalysis was conducted among the subset of patients with at least 12 months of continuous enrollment after discharge. A multivariable logistic regression model characterized the association between osteoporosis medication use within 12 months after discharge and all measured patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

A second sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine only incident osteoporosis medication use. Thus, among patients with no claims for osteoporosis medications during the baseline period, we examined the rates of treatment for both for the primary sample and for the subset of patients with at least 12 months of continuous enrollment after discharge. This analysis used the same Kaplan-Meier, multivariable Cox proportional hazards, and multivariable logistic regression modeling approaches as described in the first paragraph of this section.

Results

Study sample

The study databases contained 147,199 patients hospitalized for hip fracture between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011. Of these patients, 111,283 had 6 months of continuous insurance enrollment prior to the index hip fracture. Patients were excluded from the study for the following reasons: diagnosis of cancer during the baseline period (n = 8719), diagnosis of Paget's disease during the baseline period (n = 35), age <50 years at index (n = 4381), or missing geographic information (n = 1261). Ultimately, the study sample comprised 96,887 patients and the median follow-up was 240 days.

The demographics and clinical characteristics of the study population are contained in Table 1. Patients had an average age of 80 years, and 70.3% were female. Overall, 16.1% of patients had a documented previous fragility fracture during the baseline period, and most patients had no evidence of osteoporosis medications during the same period. All U.S. Census Bureau regions were represented in the sample, and each year in the study period had over 3000 patients. To enable examination of the proportion of patients with each measured characteristic that used osteoporosis medication within 12 months after discharge, Supporting Table 3 presents a variation of Table 1 with row percentages listed for categorical variables.

Unadjusted patterns of osteoporosis medication use

After hospital discharge, 24.0% of patients (n = 23,250) used an osteoporosis medication within 12 months, 40.5% of patients (n = 39,248) were followed for 12 months and used no osteoporosis medications, and 35.5% of patients (n = 34,389) were censored before 12 months. Among the users of osteoporosis medications, the types of osteoporosis medications initiated were as follows: bisphosphonates (70.9%), HRT (10.7%), calcitonin (9.6%), raloxifene (6.0%), teriparatide (2.6%), and denosumab (0.3%). Compared with patients that used osteoporosis medication within 12 months after discharge, those who did not had a lower proportion of females (64.5% versus 88.7%, p < 0.001), had more baseline comorbidities, but used fewer medications of interest.

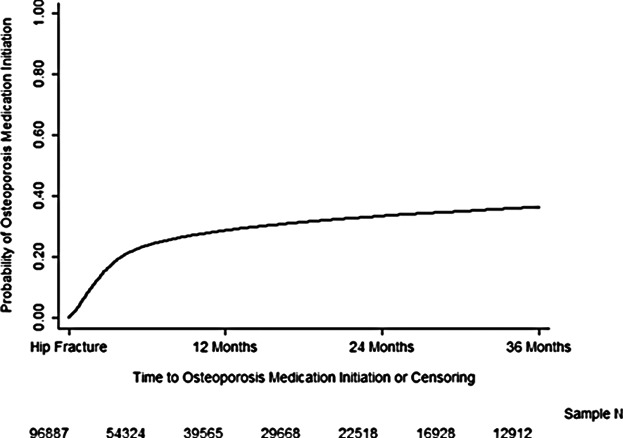

Figure 1 demonstrates the distribution of time to osteoporosis medication use within 12 months after discharge, as well as follow-up of up to 36 months. Among patients who used osteoporosis medication within 12 months after discharge, the mean ± SD and median number of days to osteoporosis medication use was 92 ± 79, and 69. The Kaplan-Meier estimated probability of osteoporosis medication use within 12 months after discharge was 28.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 28.2% to 28.8%). This is slightly higher than the total cohort percentage because of subject dropout during follow-up. In the subset of 79,178 patients with no claims for osteoporosis medications during the baseline period, the osteoporosis medication use rate within 12 months of discharge was 16.5% (95% CI, 16.2% to 16.8%). For the subset of 17,709 patients with osteoporosis medication use during the baseline period, this rate was 79.6% (95% CI, 78.9% to 80.2%). The medication use rates were very similar for the study population after restricting to subjects with at least 3, 6, and 9 months of follow-up (see legend for Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Distribution of time to osteoporosis medication use within 36 months after discharge (Kaplan-Meier method). Six months, all patients = 0.162; patients with 3+ months of enrollment (ie, excluding patients censored before 3 months) = 0.169. Six months: all patients = 0.236; patients with 6+ months of enrollment = 0.254. Nine months: all patients = 0.264; patients with 9+ months of enrollment = 0.290.

Some subjects who did not receive an osteoporosis medication were followed for <12 months. In the sensitivity analysis only including subjects with at least 12 months of continuous enrollment after discharge, the percentage of patients initiating osteoporosis medication within 12 months of discharge was 31.4% (18,902 of 60,275 patients) overall and 17.9% (8528 of 47,621 patients) among those with no claims for osteoporosis medications during the baseline period.

Correlates of osteoporosis medication initiation

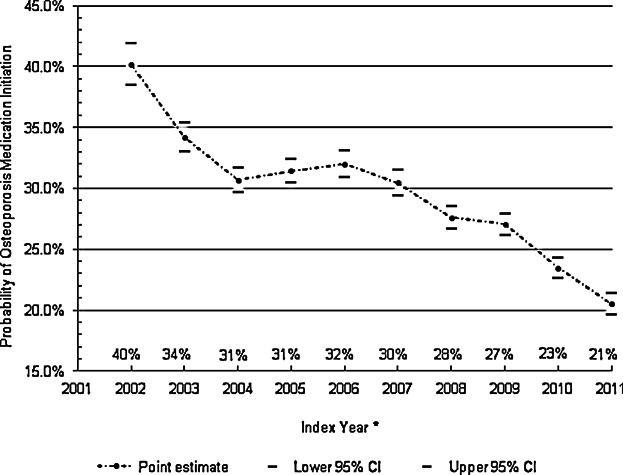

The annual Kaplan-Meier estimated probabilities of osteoporosis medication use within 12 months after discharge over the 10-year study period is shown in Fig. 2. Osteoporosis medication use rates decreased from 40.2% in 2002, to 20.5% in 2011. This trend was statistically significant (p < 0.001) using a bivariate Cox proportional hazards model treating index year as a linear variable.

Fig 2.

Annual unadjusted probability of osteoporosis medication use within 12 months after discharge (Kaplan-Meier method).

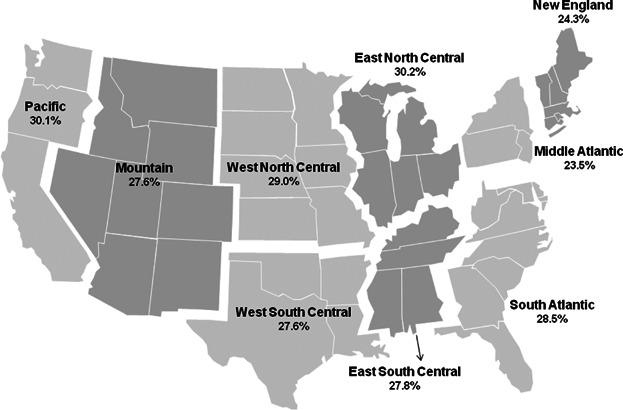

The Kaplan-Meier estimated probabilities of osteoporosis medication use by regional geography, using U.S. Census Bureau Division defined regions, is represented in Fig. 3. Osteoporosis medication use rates differed little by U.S. Census Bureau Division, ranging from 23.5% in the Middle Atlantic region, to 30.2% in the East North Central region.

Fig 3.

Unadjusted probability of osteoporosis medication use within 12 months after discharge, by U.S. Census Bureau Division.

The results of the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model focusing on all subjects is shown in Table 2. Osteoporosis medication initiation decreased with each subsequent calendar year (all p < 0.05), adjusting for patient demographics and clinical characteristics. The factor most strongly associated with an increased likelihood of osteoporosis medication initiation was baseline use of osteoporosis medications prior to the hip fracture (hazard ratio [HR] = 7.45; 95% CI, 7.23–7.69), whereas the factor most strongly associated with a decreased likelihood of osteoporosis medication initiation was male sex (HR = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.43–0.47).

Table 2.

Cox Regression of the Correlates of Osteoporosis Medication Use Within 12 Months After Discharge

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||

| 60–69 years versus 50–59 years | 0.965 | 0.902–1.032 | 0.298 |

| 70–79 years versus 50–59 years | 0.821 | 0.771–0.874 | <0.001 |

| ≥80 years versus 50–59 years | 0.660 | 0.621–0.700 | <0.001 |

| Male versus female | 0.451 | 0.432–0.471 | <0.001 |

| Census division | |||

| Mid Atlantic versus New England | 0.907 | 0.851–0.966 | 0.003 |

| East North Central versus New England | 0.950 | 0.884–1.021 | 0.162 |

| West North Central versus New England | 0.928 | 0.888–0.969 | 0.001 |

| South Atlantic versus New England | 0.824 | 0.776–0.874 | <0.001 |

| East South Central versus New England | 0.850 | 0.774–0.933 | 0.001 |

| West South Central versus New England | 0.836 | 0.796–0.878 | <0.001 |

| Mountain versus New England | 0.869 | 0.813–0.928 | <0.001 |

| Pacific versus New England | 0.874 | 0.826–0.925 | <0.001 |

| Urban versus rural residencea | 0.996 | 0.960–1.034 | 0.850 |

| Health plan type | |||

| HMO versus fee for service | 1.030 | 0.985–1.077 | 0.200 |

| POS versus fee for service | 0.944 | 0.862–1.034 | 0.216 |

| PPO versus fee for service | 0.996 | 0.963–1.029 | 0.792 |

| Other versus fee for serviceb | 0.950 | 0.836–1.079 | 0.429 |

| Unknown versus fee for service | 0.895 | 0.798–1.004 | 0.059 |

| Index year | |||

| 2003 versus 2002 | 0.869 | 0.804–0.939 | <0.001 |

| 2004 versus 2002 | 0.787 | 0.730–0.849 | <0.001 |

| 2005 versus 2002 | 0.815 | 0.757–0.877 | <0.001 |

| 2006 versus 2002 | 0.737 | 0.684–0.795 | <0.001 |

| 2007 versus 2002 | 0.730 | 0.678–0.787 | <0.001 |

| 2008 versus 2002 | 0.681 | 0.632–0.733 | <0.001 |

| 2009 versus 2002 | 0.666 | 0.618–0.717 | <0.001 |

| 2010 versus 2002 | 0.584 | 0.541–0.631 | <0.001 |

| 2011 versus 2002 | 0.530 | 0.490–0.573 | <0.001 |

| Alcoholism | 0.816 | 0.653–1.021 | 0.075 |

| Stroke | 0.905 | 0.855–0.957 | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.921 | 0.876–0.968 | 0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.739 | 0.692–0.788 | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 0.685 | 0.622–0.755 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 0.857 | 0.809–0.907 | <0.001 |

| Hemiplegia | 0.782 | 0.628–0.973 | 0.028 |

| Mild liver disease | 1.040 | 0.837–1.293 | 0.721 |

| Severe liver disease | 0.961 | 0.676–1.365 | 0.823 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.873 | 0.765–0.996 | 0.044 |

| Osteodystrophy | 0.599 | 0.145–2.477 | 0.479 |

| Peptic ulcer | 0.890 | 0.734–1.079 | 0.236 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.916 | 0.848–0.990 | 0.026 |

| Renal disease | 0.689 | 0.626–0.759 | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.112 | 1.028–1.204 | 0.008 |

| Osteoporosis | 1.095 | 1.047–1.146 | <0.001 |

| Glucocorticoids | 1.097 | 0.973–1.238 | 0.132 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 0.922 | 0.868–0.980 | 0.009 |

| Hormone deprivation therapy | 1.516 | 1.300–1.769 | <0.001 |

| Anticonvulsants | 0.992 | 0.950–1.036 | 0.721 |

| Immunosuppressants | 1.144 | 1.020–1.282 | 0.021 |

| Strong opioids | 1.057 | 1.008–1.110 | 0.023 |

| Weak opioids | 1.049 | 1.016–1.083 | 0.003 |

| Non-opioid analgesics | 1.061 | 1.025–1.099 | 0.001 |

| Any osteoporosis medication | 7.453 | 7.228–7.685 | <0.001 |

| Fragility fracture | 1.000 | 0.963–1.038 | 0.994 |

| Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.033 | 1.008–1.059 | 0.010 |

| Number of unique three-digit ICD-9-CM diagnoses | 1.000 | 0.996–1.004 | 0.968 |

| Number of unique National Drug Codes | 1.009 | 1.006–1.012 | <0.001 |

| Bone density test | 1.092 | 1.029–1.157 | 0.003 |

| Inpatient admission | 0.862 | 0.821–0.905 | <0.001 |

| Visit to any specialist | 1.151 | 1.096–1.209 | <0.001 |

All variables measured at index or during the baseline period. In all models, no evidence of multicollinearity of the models' independent variables was detected. However, some variables used in the Cox proportional hazards models, including index year, violated the proportionality assumption. A post hoc sensitivity analysis in which variables that violated the proportionality assumption were interacted with time to allow for time-varying coefficients yielded results that were nearly identical to the main models (data not shown)

HMO = health maintenance organization; POS = point of service; PPO = preferred provider organization; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification.

Urban residence is defined as residence in a Metropolitan Statistical Area as designated by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Other health plan types are as follows: exclusive provider organization, consumer-directed health plan, and high-deductible health plan.

In the sensitivity analyses of patients with 12 months of follow-up as well as the sensitivity analyses of patients with no claims for osteoporosis medications during the baseline period, increasing index year remained associated with a decreasing rate of osteoporosis medication initiation within 12 months after discharge (all p < 0.05, data not shown).

Discussion

The rates of osteoporosis medication use post–hip fracture have been noted to be dropping over the past decade, during a time when the pharmacotherapeutic armamentarium for osteoporosis treatment has improved. We therefore retrospectively examined the post–hip fracture osteoporosis medication use rates in a cohort of almost 100,000 U.S. residents sustaining a hip fracture. We found very low osteoporosis treatment rates in this cohort of postfracture patients. Moreover, the treatment rates declined over the study period, from 2002 to 2011. The most striking correlate of postfracture osteoporosis treatment was prefracture osteoporosis medication use. There was some variation in medication use by geographic U.S. Census Division; however, all regions demonstrated low osteoporosis treatment rates.

Although this very low osteoporosis treatment rate suggests suboptimal care, perhaps it should not be surprising. Over the last decade there have been concerns associated with the most common osteoporosis treatment category, the bisphosphonates. High-profile articles in the lay press regarding osteonecrosis of the jaw, atypical femoral fractures, and atrial fibrillation have garnered much attention from patients and providers.20,21 Whereas it is understandable for patients to voice concerns regarding potential drug toxicities, these adverse events appear to be rare.22 The well-described benefits of osteoporosis treatment in postfracture patients should outweigh the potential risks, but the observed decrease in treatment rates appears to suggest otherwise, or to indicate that other potential factors are involved.

Narrowing the osteoporosis treatment gap for patients post–hip fracture, who are by definition at high risk for future fracture, requires identifying the root causes for the diminished rate of medication use. However, the causes are likely complicated. There seems to be an educational gap between what is known about the benefits and the perceived risks of these treatments, particularly in the lay press, but perhaps also among patients and practitioners.23–25 Therefore, a targeted educational effort for patients and providers would facilitate better understanding of the perceived risks and benefits of taking medications for osteoporosis.

Another possible cause of the low treatment rates may stem from the fragmented nature of the U.S. health care system. Patients with hip or other fractures often present to emergency departments and are seen by orthopedic surgeons who attend to the acute fracture needs. Upon discharge from the orthopedic surgeon's care, there may be difficulties in communicating the long-term needs of patients who likely have osteoporosis. This information gap is a systemic problem beyond any one provider's ability to fix and is demonstrated by the fact that some subjects in our study who were using osteoporosis medications before their index hip fracture appeared to have not resumed postfracture. Health care systems with integration have demonstrated improved postfracture osteoporosis treatment rates.26,27 It has been documented that a simple letter from the orthopedic team to the primary care physician has not had a significant impact on the rates of osteoporosis treatment.28 However, active involvement of the orthopedic team in osteoporosis care has been demonstrated to significantly improve the rates of medication use following a hip fracture.29

Potential solutions to improve postfracture osteoporosis medication use rates include improved collaborative care models, involving orthopedic surgeons, primary care physicians, as well as the osteoporosis specialist. The collaborative care model has been advocated by a joint international task force looking at secondary fracture prevention.30 One such collaborative care model is the fracture liaison service, which has become widespread in the United Kingdom and some U.S. healthcare systems.31–33 For collaborative care models to improve the care of patients with fragility fractures likely requires the engagement and leadership of the orthopedic community.34 Outpatient follow-up of patients with recent hip fracture has many challenges, including transportation, comorbid medical problems, and often the requirement of a family member to accompany the patient. Effective collaborative care could minimize the need for multiple physician visits, which should improve the convenience of care for the patient and their families.

Another potential lever for improving postfracture osteoporosis medication use rates is changing payment methods. If payers required demonstration of adequate postfracture osteoporosis care, such as bone mineral density testing and appropriate medication prescribing, local health care systems would likely improve their internal communication among providers, and potentially adopt collaborative care models. In the U.S., the Center for Medicare and Medicaid services, which pays for the majority of hip fracture care, could institute such payment reform. We believe that this would produce significant improvements in care, and potentially minimize the post–hip fracture treatment gap among osteoporosis patients.

These study findings should be viewed in the context of several potential limitations. The population we studied participated in employer-run health care and pharmacy benefits programs. This type of insurance arrangement is common, but not universal. Thus, the osteoporosis treatment rates might be biased in the employer-based population we studied. Because of the “richer” insurance coverage of subjects in the Truven database, it is possible that the general population treatment rates might be lower than what we observed because of less insurance coverage. Another potential limitation of our database is the lack of information on several potential root causes of low treatment rates. We have no information about specific health care systems involved in providing care to the patients in the study population and are unable to determine if their care was provided in an integrated or a non-integrated health care system. Nor, do we know when patients were admitted or discharged to a nursing home. Racial and ethnic data are not available in the Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases. Finally, 35.5% of patients were censored prior to the end of the 12-month follow-up period, 80.0% of whom were censored owing to disenrollment from health insurance. Other causes for censoring included death, which is common in older postfracture patients. Further study may better delineate factors impacting osteoporosis medication use rates.

The major strength of our analysis was the longitudinal nature of the database, covering a recent decade for a very large population. In addition, the complete information on health care and pharmacy utilization as well as the national scope makes the study database robust.

In conclusion, we studied post–hip fracture osteoporosis medication use rates over the last decade in the United States. We found the majority of post–hip fracture patients do not receive osteoporosis treatment, and the rates of treatment have been declining. This finding is not consistent with osteoporosis treatment guidelines endorsed by the National Osteoporosis Foundation.9 Determining the causes for this less-than-optimal care is essential to reversing this observed trend. There are several healthcare systems in the United States that have developed methods for improving postfracture care, including coordinated care systems enhancing collaboration between providers, and these models have demonstrated substantial improvement in patient outcomes.26,27 These fracture liaison services may be transferrable across settings and may not only help improve postfracture treatment rates, but also the timing of treatment initiation, which was delayed 2 to 3 months postfracture in our study population. Payers, hospital administrators, and providers should look to methods for stimulating such improvement.

Disclosures

DHS has received salary support from research grants to Brigham and Women's Hospital from Amgen and Lilly (neither grant was related to this project); he has also received an honorarium from the American Orthopaedic Association's Own the Bone Program (<$5,000 per year) and serves in an unpaid role on the National Bone Health Alliance. SSJ and DM are full-time employees of Truven Health Analytics. NNB and KDK are full-time employees of Eli Lilly & Company. JML has served on a Speakers' Bureau for Eli Lilly and Scientific Advisory Boards for Bone Therapeutics, SA, CollPlant, Inc., DFine, Graftys, and Zimmer.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Eli Lilly & Company.

Authors' roles: DHS, SSJ, NNB, DM, JML, and KDK all made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; participated in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; approved the final version of the submitted manuscript; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. SSJ had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Salkeld G, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, et al. Quality of life related to fear of falling and hip fracture in older women: a time trade off study. BMJ. 2000;320(7231):341–36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7231.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giversen IM. Time trends of mortality after first hip fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(6):721–32. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haleem S, Lutchman L, Mayahi R, Grice JE, Parker MJ. Mortality following hip fracture: trends and geographical variations over the last 40 years. Injury. 2008;39(10):1157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannus P, Parkkari J, Sievänen H, Heinonen A, Vuori I, Järvinen M. Epidemiology of hip fractures. Bone. 1996;18(1 Suppl):57S–63S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cauley JA. Public health impact of osteoporosis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(10):1243–51. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majumdar SR, Beaupre LA, Harley CH, et al. Use of a case manager to improve osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(19):2110–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lönnroos E, Kautiainen H, Karppi P, Hartikainen S, Kiviranta I, Sulkava R. Incidence of second hip fractures. A population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(9):1279–85. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0375-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry SD, Samelson EJ, Hannan MT, et al. Second hip fracture in older men and women: the Framingham Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(18):1971–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadarette SM, Katz JN, Brookhart MA, et al. Trends in drug prescribing for osteoporosis after hip fracture, 1995–2004. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(2):319–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jennings LA, Auerbach AD, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK, Lee SJ. Missed opportunities for osteoporosis treatment in patients hospitalized for hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):650–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright NC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, et al. Recent trends in hip fracture rates by race/ethnicity among older US adults. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(11):2325–32. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams AL, Shi J, Takayanagi M, Dell RM, Funahashi TT, Jacobsen SJ. Ten-year hip fracture incidence rate trends in a large California population, 1997–2006. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):373–6. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-1938-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Truven Health Analytics. MarketScan Bibliography. Available from: http://marketscan.truvenhealth.com/marketscanuniversity/publications/2012%20Truven%20Health%20MarketScan%20Bibliography.pdf.

- 15.CPT. Chicago: American Medical Association;; 2009. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene WH. Econometric analysis. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied survival analysis: regression modeling of time to event data. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolata G. Researchers puzzled by role of osteoporosis drug in rare thighbone fractures. New York Times [Internet]. 2010 Mar 25 [cited 2014 Apr 11];Sect. A:20. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/25/health/25bone.html.

- 21.Kolata G. Drug for bones is newly linked to jaw disease. New York Times [Internet]. 2006 Jun 2 [cited 2014 Apr 11]. Available from. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/02/health/02jaw.html.

- 22.Suresh E, Pazianas M, Abrahamsen B. Safety issues with bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53(1):19–31. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket236. Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaton DE, Dyer S, Jiang D, et al. Osteoporosis Fracture Clinic Screening Program Evaluation Team. Factors influencing the pharmacological management of osteoporosis after fragility fracture: results from the Ontario Osteoporosis Strategy's fracture clinic screening program. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(1):289–96. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2430-6. Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brask-Lindemann D, Cadarette SM, Eskildsen P, Abrahamsen B. Osteoporosis pharmacotherapy following bone densitometry: importance of patient beliefs and understanding of DXA results. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(5):1493–501. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1365-4. May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yood RA, Mazor KM, Andrade SE, Emani S, Chan W, Kahler KH. Patient decision to initiate therapy for osteoporosis: the influence of knowledge and beliefs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1815–21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0772-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greene D, Dell RM. Outcomes of an osteoporosis disease-management program managed by nurse practitioners. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2010;22(6):326–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman ED. A schema for effective osteoporosis management. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2003;11(10):611–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawker G, Ridout R, Ricupero M, Jaglal S, Bogoch E. The impact of a simple fracture clinic intervention in improving the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(2):171–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miki RA, Oetgen ME, Kirk J, Insogna KL, Lindskog DM. Orthopaedic management improves the rate of early osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture. A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(11):2346–53. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, et al. Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(10):2039–46. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fraser M, McLellan AR. A fracture liaison service for patients with osteoporotic fractures. Prof Nurse. 2004;19(5):286–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright SA, McNally C, Beringer T, Marsh D, Finch MB. Osteoporosis fracture liaison experience: the Belfast experience. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25(6):489–90. doi: 10.1007/s00296-004-0573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charalambous CP, Mosey C, Johnstone E, et al. Improving osteoporosis assessment in the fracture clinic. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91(7):596–8. doi: 10.1308/003588409X432400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell PJ. Fracture liaison services: a systematic approach to secondary fracture prevention. Osteoporosis Review. 2009;17(1):14–6. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information