Abstract

3-dimensional chromosomal conformations regulate transcription by moving enhancers and regulatory elements into spatial proximity with target genes. Here, we describe activity-regulated long-range loopings bypassing up to 0.5 megabase of linear genome to modulate NMDA glutamate receptor GRIN2B expression in human and mouse prefrontal cortex. Distal intronic and 3’ intergenic loop formations competed with repressor elements to access promoter-proximal sequences, and facilitated expression via a ‘cargo’ of AP-1 and NRF-1 transcription factors and TALE-based transcriptional activators. Neuronal deletion or overexpression of Kmt2a/Mll1 H3K4- and Kmt1e/Setdb1 H3K9-methyltransferase was associated with higher order chromatin changes at distal regulatory Grin2b sequences and impairments in working memory. Genetic polymorphisms and isogenic deletions of loop-bound sequences conferred liability for cognitive performance and decreased GRIN2B expression. Dynamic regulation of chromosomal conformations emerges as a novel layer for transcriptional mechanisms impacting neuronal signaling and cognition.

INTRODUCTION

Gene expression is governed by distal regulatory elements, including enhancers and locus control regions which have been intensely studied in extraneural tissues such as blood for more than 30 years(Banerji et al., 1981; Li et al., 1999). These mechanisms, however, essentially remain unexplored in the context of neuronal gene expression affecting cognition and behavior. Based on genome-scale mappings of promoter-distal regulatory regions for a large variety of cell lines and tissues, including brain (2014; Andersson et al., 2014; Bernstein et al., 2012; Gerstein et al., 2012; Maher, 2012; Thurman et al., 2012), it is estimated that each transcription start site (TSS) is targeted on average by five different enhancers (Andersson et al., 2014). Importantly, chromosomal loop formations are critical for this layer of transcriptional regulation, because many distal regulatory elements typically only become effective when placed in close spatial proximity to the transcription start sites of their target gene(Levine et al., 2014). Loop formations—which often require CTCF-binding factor, cohesins and various other proteins assembled into scaffolds and anchors(Razin et al., 2013)—potentially bypass many kilo- (Kb) or even megabases (Mb) of linear genome, thereby repositioning promoter-distal regulatory elements next to their target promoters and TSSs (Gaszner and Felsenfeld, 2006; Wood et al., 2010).

Here, we provide a deep and integrative analysis for the spatial architectures of ~800 kb non-coding sequence on human (mouse) chromosome 12p31.1 (6, 66.38cM), encompassing N-Methyl-D-Asparate (NMDA) glutamate receptor subunit GRIN2B, broadly implicated in the neurobiology of psychiatric disease, including schizophrenia and depression (Ayalew et al., 2012; Fallin et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2010; Martucci et al., 2006; O'Roak et al., 2012; Talkowski et al., 2012; Weickert et al., 2012). We provide evidence for a complex and multilayered regulatory network, involving multiple chromosomal loopings that target the GRIN2B/Grin2b TSS and, depending on their specific protein ‘cargo’, either repress or facilitate transcription. Long-range promoter enhancer interactions governing GRIN2B expression are conserved between human and mouse brain, impact cognition and working memory, and confer liability for psychiatric disease. The multidimensional approaches presented here provide a roadmap to uncover neurological function for the vast but largely unexplored non-coding sequences in the human genome.

RESULTS

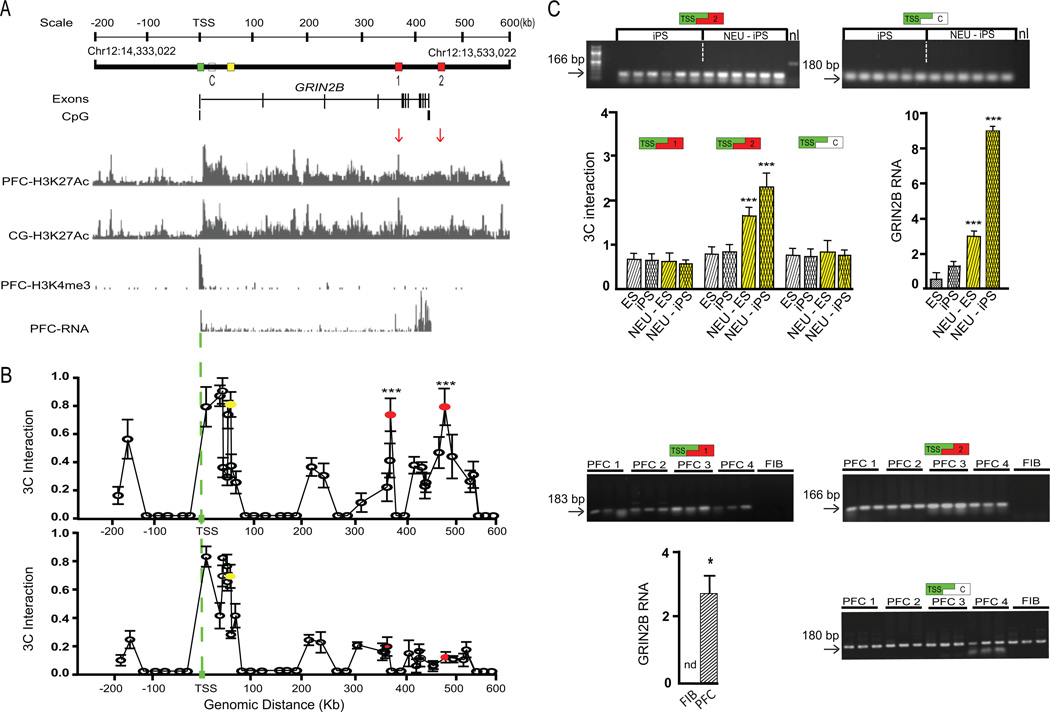

To explore spatial genome architectures at the NMDA receptor GRIN2B locus, we employed chromosome conformation capture (3C) on prefrontal cortex (PFC) of adult subjects, and cultured fibroblasts for comparison. Given that both the GRIN2B gene body and the surrounding 5’ and 3’ sequences were epigenetically decorated with sharp peaks for histone H3 acetylated at lysine 27, an open chromatin mark broadly enriched at active promoters and enhancers(Zhou et al., 2011), we screened approximately 800kb on chromosome 12 encompassing GRIN2B (Fig. 1A). Both PFC and FIB showed 3C PCR products for restriction fragments positioned less than 50kb from the TSS. However, PFC but not FIB showed additional long-range interactions with intronic and intergenic sequences 348 and 449 kb downstream from the TSS (Figure 1B). These loops, which we named hereafter GRIN2BTSS+348kb and GRIN2BTSS+449kb, were in the PFC and neighboring cingulate cortex defined by sharp peaks of histone H3 acetylated at lysine 27 (H3K27ac), an open chromatin mark enriched at active promoters and enhancers (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A,B). Of note, GRIN2B is expressed in PFC but not fibroblasts (Fig. 1B). Therefore the absence of GRIN2BTSS+348kb and GRIN2BTSS+449kb loopings in fibroblasts would suggest a potential association with gene expression. To further test this hypothesis, we monitored GRIN2B RNA and the GRIN2BTSS+348kb and GRIN2BTSS+449kb loopings during the course of neuronal differentiation, using previously described protocols and induced pluripotent cell (iPS) and H9 embryonic stem cell lines (Bharadwaj et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2014). In both cell lines, neuronal differentiation was associated with robust increases both in GRIN2B RNA and the long-range loop, GRIN2BTSS+449kb (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Brain-specific Higher Order Chromatin at GRIN2B (chr. 12p31.1).

(A) Linear map for 800kb surrounding GRIN2B TSS, including GRIN2B gene body with exons and CpG islands as indicated. Browser tracks for (top to bottom) H3K27ac in PFC and cingulate cortex (CG)(Zhu et al., 2013), H3K4me3 from PFC neurons(Cheung et al., 2010) and PFC-RNAseq(Bharadwaj et al., 2013)(B) (left) X–Y graphs (mean ± S.D.) present chromosome conformation capture (3C) profiles anchored on restriction fragment with TSS (green). (top) adult PFC (N=4) and (bottom) skin fibroblasts (N=3). Notice much stronger interaction of red-marked fragments, peak 1 (distal arm of GRIN2BTSS+348kb loop) and peak 2 (distal arm of GRIN2BTSS+449kb) with the TSS specifically in brain but not fibroblast (Two-way ANOVA cell type × 3C primer F(42,210)=157.7, P<0.001, Newman-Keuls posthoc P < 0.001) (right) Representative 3C PCR gels for four PFC specimens PFC 1–4 and cultured fibroblasts (FIB), showing 3C long-range interactions of TSS with +348 kb (peaks 1) and +449kb (peak 2) sequences specifically in PFC samples, and, as control, sequences within first intron. (right) Bar graph (mean ± S.D; N=3–4/group) comparing GRIN2B RNA in PFC and FIB. (C) 3C PCR gels from iPS and iPS-derived differentiated neuronal culture (NEU-iPS), nl = 3C assays without ligase. Bar graphs (mean ± S.D; N=3–4/group) quantify TSS-bound loopings with distal (+348kb and +449kb sequences) and proximal intron, as indicated. Significant changes after differentiation, GRIN2B RNA: F(1,8) = 714.85, P < 0,001 and GRIN2BTSS+449kb, F(1,8) = 507.35, P < 0,001; Newman-Keuls post hoc p < 0.001. See also Figure S1.

We noticed that the 5’end of GRIN2B is part of two long-range chromosomal loop formations, GRIN2BTSS+348kb and ‘GRIN2BTSS+449kb (Figure 1B). Interestingly, convergence of multiple loopings onto a common structure (‘chromatin hub’) had previously been associated with transcriptional regulation and repression at the Globin and Myb loci(de Laat and Grosveld, 2003; Harmston and Lenhard, 2013), and olfactory receptor genes(Clowney et al., 2012). Therefore, we speculated that GRIN2B expression could be governed by dynamic changes in repressive and facilitative chromosomal loopings converging at regulatory elements surrounding the GRIN2B transcription start site (TSS). To explore this, we choose Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK) 293 cells, which robustly express several hundred neuronal genes, including GRIN2B (Shaw et al., 2002). Interestingly, HEK 293 chromatin surrounding the GRIN2B gene showed multiple sharp peaks for the CCCTC-binding factor and chromosomal loop-organizer CTCF(Merkenschlager and Odom, 2013), with the strongest binding around the distal arm of GRIN2BTSS+449kb (Fig. 2A, Fig. S1A,B). CTCF and associated proteins function as insulators and anchors for promoter-enhancer interactions, and often bind to sequences in direct proximity and overlap with enhancer elements(Ghavi-Helm et al., 2014). Using 3C-ChIP-loop (chromatin immunoprecipitation with conformation capture) with an anti-CTCF antibody, we confirmed that the GRIN2B TSS and its partnering sequences positioned +449kb further downstream are tethered together into higher order chromatin enriched with CTCF (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the distal arm of GRIN2BTSS+449kb showed a strong enrichment for transcription factors previously attributed a key regulatory role for GRIN2B expression, including Nuclear Respiratory Factor 1 (NRF-1)(Dhar and Wong-Riley, 2009; Priya et al., 2013) and Activating Protein 1 (AP-1) (Qiang and Ticku, 2005) (Fig. 2A,B; Fig. S1A). Using a minimal promoter/luciferase reporter assay, we confirmed enhancer-like activity for two sequences in the distal arm of GRIN2BTSS+449kb, each extending over 100–125 base pairs and defined by sharp, up to 40-fold, enrichment for AP-1 motifs and NRF-1 and AP-1 proteins (Fig. 2B). From this, one would predict that weakening or disruption of the GRIN2BTSS+449kb loop would result in decreased GRIN2B expression. We generated stable HEK subclones with tet-on transactivator controlled induction of the histone methyltransferase SET-domain Bifurcated 1 (SETDB1/ESET/KMT1E), a previously described negative regulator of GRIN2B expression which confers, in human cell lines and mouse brain, repressive histone H3-lysine K9 methylation at proximal intronic sequences spreading up to 40kb downstream from the TSS(Jiang et al., 2010). Indeed, and as expected, doxycycline (DOX) but not vehicle treated SETDB1-inducible HEK cells showed a marked upregulation of SETDB1 RNA and protein levels in conjunction with decreased GRIN2B expression (Fig. 2C). This was associated with up to 5-fold increases in SETDB1 occupancy at the GRIN2B TSS and gene-proximal intronic sequences, in conjunction with localized histone H3K9 hypermethylation and a strong 5- to 10-fold increase in occupancy of heterochromatin-associated protein 1 HP-1α (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Coordinated regulation of multiple chromosomal loopings targeting GRIN2B TSS.

(A) Browser tracks from ENCODE data collection (Bernstein et al., 2012), showing highest enrichments for (top) CTCF and (bottom) NRF-1 proteins in sequences +449kb downstream from TSS (arrows). Bottom gels, PCR from 3C-ChIP-loop with anti-CTCF antibody (HEK293 cells), showing CTCF enrichment specific for GRIN2BTSS+449kb loop (B) (top) 4kb of GRIN2BTSS+449kb (chr12:13,680,308-13,684,308) showing (bars) elevated density of AP-1 motifs and increased AP-1 and NRF-1 occupancy in ENCODE ChIP-seq tracks (Bernstein et al., 2012). (bottom) Reporter assay for three 100–125 bp sequences (C (control) and 2a, 2b from red box no. 2 (=GRIN2BTSS+449kb) shown in panel A, showing up to 6-fold increase in minimal promoter- TATA box luciferase activity. (C) (top) Immunoblots (left) anti-SETDB1, (right) anti-FLAG antibody recognizing inducible FLAG-SETDB1 protein and (bottom) quantitative RT-PCR assays from stable HEK293 clone for inducible SETDB1 expression. Note robust induction of SETDB1, and parallel decline in GRIN2B RNA, 72 hours after addition of doxycycline (+ DOX), compared to untreated culture (−DOX). (D) ChIP-PCR, with (left) repressive SETDB1, HP1and H3K9me3 and (right) facilitative H3K27ac, AP-1 and NRF-1 in chromatin across GRIN2B locus, as indicated (gray box, −250kb (upstream from TSS) control sequence; green box, TSS; red box no. 1, GRIN2BTSS+348kb and no. 2, GRIN2BTSS+449kb; yellow box, intronic repressor and SETDB1 target site). Striped (white) bars, + (−) DOX. (E) 3C PCR expressed as fold change (+DOX/−DOX). Notice decrease in long-range loopings, GRIN2BTSS+348kb and GRIN2BTSS+449kb, in conjunction with (D) localized, SETDB1-mediated H3K9 hypertrimethylation and HP1 binding at proximal intronic sequences < 40kb from TSS. All bar graphs N=3-group, mean ± (B) S.E.M, (C, D, E) S.D. *, **, *** P < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, Two way ANOVA (ChIP) and unpaired t-tests after Bonferroni correction (3C, qRT-PCR, luciferase assays). (F) Dynamic model; long-range GRIN2BTSS+348kb and GRIN2BTSS+449kb loops are absent in cells not expressing GRIN2B. Upon GRIN2B expression, AP-1 and NRF-1 enriched enhancer elements, positioned in the distal arm of GRIN2BTSS+449kb, undergo relocation and are moved into close spatial proximity with the TSS. This is counterbalanced by shorter-range TSS-bound intronic loopings enriched with repressive chromatin. See also Figure S1.

This ‘heterochromatization’ around the TSS and first intron showed only limited spreading across the wider GRIN2B locus, because HP-1 and trimethyl-H3K9 remaining at very low levels at distal, loop-bound sequences, including GRIN2BTSS+449kb, after DOX treatment. Conversely, proteins and histone marks with a facilitatory role for gene expression and transcription, including histone H3K27 acetylation and NRF-1 transcription factor and AP-1 protein FOSL2, were maintained at high levels at the sequences 449kb dowstream from the TSS, regardless of DOX treatment. This would suggest that SETDB1 induction did not disrupt the molecular composition of the distal arm of the long-range loop, GRIN2BTSS+449kb (Fig. 2D,F). In sharp contrast, SETDB1 induction was associated with a significant 30–40% decrease in GRIN2BTSS+348kb and GRIN2BTSS+449kb loopings while the physical interactions between the TSS and the SETDB1 repressor-enriched proximal intronic sequences were significantly increased (Fig. 2E). These experiments, taken together, demonstrate that SETDB1-mediated downregulation of GRIN2B expression is associated with dynamic repositioning of multiple distal DNA sequences competing, via specific loop formations, for access to the GRIN2B TSS and proximal promoters. Specifically, a localized increase in repressive H3K9me3 and HP1 heterochromatin around the TSS and the first intron is associated with disruption of long-range promoter-enhancer loopings, including GRIN2BTSS+449kb. These mechanisms thereby effectively ‘shield’ the TSS and gene-proximal promoters from the access to GRIN2BTSS+449kb ‘cargo’, including AP-1 and NRF-1 transcription factors (Fig. 2F).

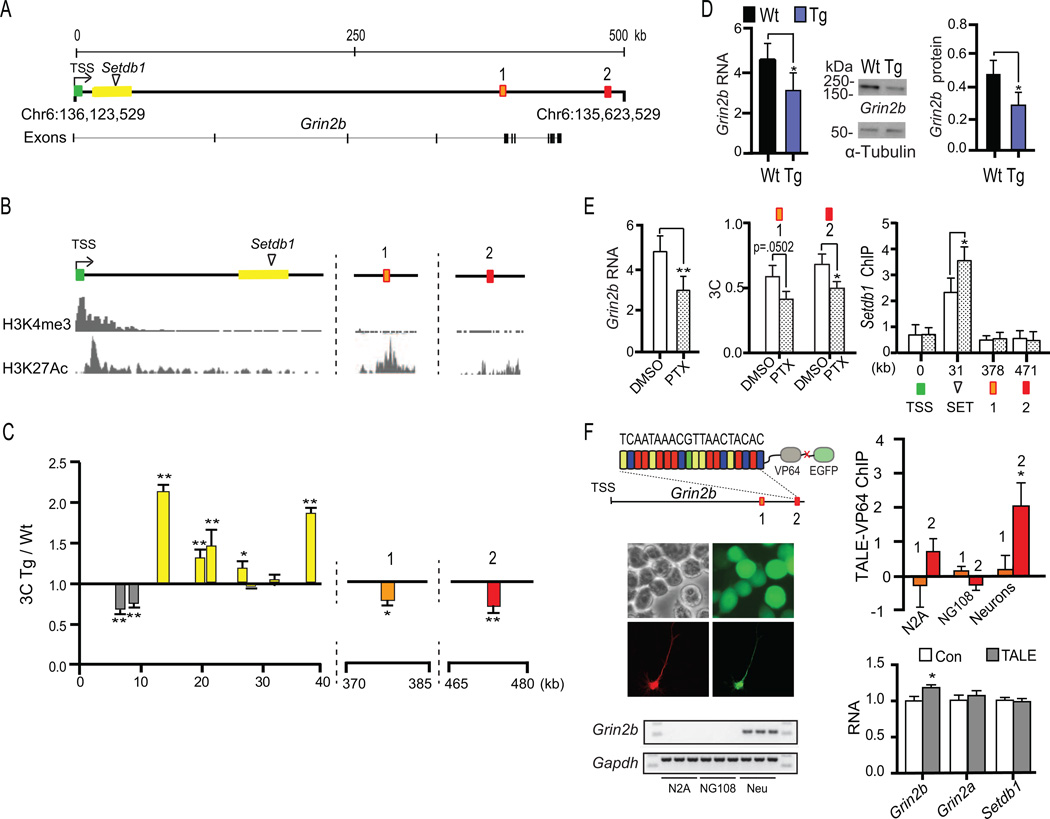

Having mapped GRIN2B higher order chromatin in human PFC, and explored the dynamics and competitive interactions of repressive and facilitative loopings in the HEK293 model, we next asked whether these mechanisms represent conserved regulatory mechanisms across different mammalian lineages. 3C assays on adult mouse cortex confirmed two long-range loopings, Grin2bTSS+378kb and Grin2bTSS+471kb, which harbored sequences with up to ~ 90% conservation to portions of the distal arms of the human loops, GRIN2BTSS+348kb and GRIN2BTSS+449kb (Fig. S1C–F, S2A). Similarities in histone modification profiles between human and mouse cortex included a single sharp peak for the transcriptional mark, trimethyl-histone H3K4 (H3K4me3) at the TSS and H3K27ac enrichment at loop-bound sequences (Figures 1A, 3A,B, S2B). Furthermore, intronic sequences positioned up to 40 kb from the Grin2b TSS are sensitive to SETDB1-mediated repressive chromatin remodeling in mouse cortical neurons (Jiang et al., 2010), similar to SETDB1’s action in (human) HEK293 cells (Fig. 2C,D). Therefore, we predicted that increased SETDB1 occupancy at TSS-bound intronic sequences in mouse cortex will result in significant weakening of the long-range loops, Grin2bTSS+378kb and Grin2bTSS+471kb. We conducted 3C on cortex of transgenic mice expressing full length Setdb1 under control of the neuron-specific 9kb calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II promoter (CK) in adult forebrain neurons(Jiang et al., 2010). Indeed, 3C PCR from adult CK-Setdb1 cortex showed, in comparison to littermate controls, significant decreases in Grin2bTSS+378kb and Grin2bTSS+471kb, while interactions between the TSS and proximal intronic sequences surrounding the SETDB1 target site were increased (Fig. 3C, Fig. S2A). In addition, as previously reported (Jiang et al., 2010), Grin2b RNA and protein levels were significantly decreased in CK-Setdb1 cortex (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. Higher order Grin2b chromatin in mouse cerebral cortex and hippocampal neurons.

(A) 500kb of linear genome (mm9, chromosome 6:135,623,529-136,123,529), encompassing Grin2b, including TSS (green), proximal intronic sequences targeted by SETDB1 (yellow), and two loop loopings (red) (1) Grin2bTSS+378kb and (2) Grin2bTSS+471kb, with sequences homologue to human GRIN2BTSS+348kb and GRIN2BTSS+449kb (Fig. S1) (B) (Top) Browser tracks for histone marks H3K4me3 and H3K27ac in adult mouse cerebral cortex(Dixon et al., 2012). (C) Fold-change (CK-Setdb1 transgenic (Tg) /wildtype littermate (Wt) of 3C PCR from adult Tg and Wt cortex (see also Fig. S2). Notice increased physical interactions of (yellow) TSS-bound +15 to +40kb intronic sequence, and significant decrease in (red box no. 1) Grin2bTSS+378kb and (red box no. 2) Grin2bTSS+471kb. Two-way ANOVA, 3C interaction × genotype F(7,32)=54.905(p<0.001). Newman-Keuls post-hoc *, **; P< 0.05, 0.01. (D) Quantification of Grin2b (left) RNA and (right) protein in adult (6–8 week) CK-Setdb1 Tg and wildtype (Wt) littermate control cortex. mean ± S.D, N=5 (RNA) and N=3 (immunoblot)/group. (E) Activity-dependent regulation of Grin2b higher order chromatin in hippocampal neurons. (top, left to right) Grin2b RNA, 3C quantification of Grin2bTSS+378kb and Grin2bTSS+471kb and SETDB1 occupancy across four regulatory sequences at Grin2b locus. Note significant increase at SETDB1 target site after 15 hours of picrotoxin (PTX) or vehicle control (DMSO). N=3–6 experiments/group, data shown as mean ± S.D..(F) (left) Grin2b-TALE-VP64-GFP specifically targets mouse Grin2b loop no. 2 (Grin2bTSS+471kb), 471 kb downstream of TSS. Images show Neuro2A cells and cultured hippocampal neurons expressing GFP-tagged TALE-VP64. RT-PCR for Grin2b and Gapdh control showing specific expression in cultured neurons. (right) anti-TALE-VP64 ChIP in N2A and NG108 cells and primary cortical neurons, expressed (y-axis) as fold change compared to non-transfected condition (N=3/group; (mean ± S.E.M., * Two-way ANOVA cell type × TALE-VP64 binding F(2,12)=4.04, P<0.05, Bonferroni posthoc P < 0.05).RT-PCR Grin2b, Grin2a and Setdb1 RNA levels in neurons transfected with TALE-VP64-EGFP (TALE), compared to mock-transfected neurons (Con). Notice specific TALE-VP64 mediated increase in Grin2b RNA (N = 6 per group, mean ± S.E.M, *P < 0.05, t-test). See also Figures S1 and S2.

Having shown SETDB1-mediated regulation of GRIN2B/Grin2b expression and long-range loopings in HEK cells (Fig. 2C,D) and transgenic CK-Setdb1 cerebral cortex (Fig. S2A), we then asked whether these mechanisms represent a physiological mechanism that operates in wildtype neurons to fine-tune Grin2b expression in a functional context, such as dynamic changes in synaptic activity. To this end, primary neuronal cultures from C57Bl6 hippocampi were exposed for 4 to 48 hours to GABAA receptor antagonist (picrotoxin/PTX, 100µM) to increase activity. In comparison to vehicle (DMSO), PTX treated cultures showed increased SETDB1 occupancy at TSS-bound intronic sequences, which was associated with a decline in Grin2b RNA most pronounced after 15 hours of treatment, resulting in decreased expression of protein. These alterations were associated with a significant downregulation of Grin2bTSS+378kb and Grin2bTSS+471kb (Fig. 3E, Fig. S2C,D). Therefore, spatial genome architectures are dynamically regulated by synaptic activity, by a mechanism that involves increased occupancy of H3K9 methyltransferase at proximal Grin2b repressor elements, and decreased access of facilitative chromatin from distal long-range loops (Grin2bTSS+378kb and Grin2bTSS+471kb) to the TSS and surrounding 5’regulatory sequences.

The long-range loop, GRIN2BTSS+449kb (Grin2bTSS+471kb in the mouse), is dynamically regulated in the context of differentiation (Fig. 1C) and synaptic activity (Fig. 3E), and facilitates expression by ‘carrying’ AP-1 and NRF-1 transcription factors bound to intergenic DNA 3’ to the gene, into physical proximity with the TSS promoter-proximal sequences positioned at the 5’end of GRIN2B/Grin2b (Fig. 2F). To further test whether the long-range loop, Grin2bTSS+471kb is involved in the regulation of gene expression, we engineered two Transcription Activator-Like Element (TALE) DNA-binding proteins (Boch et al., 2009; Moscou and Bogdanove, 2009), fused to the VP64 transcriptional activator domain which is comprised of four tandem copies of the Herpes Simplex virus protein VP16 (Beerli et al., 1998). Each TALE was designed against 20 bp of intergenic sequence positioned 3’ to Grin2b, in the distal arm of the loop Grin2bTSS+471kb and within a 500bp segment showing up to 90% conservation to the human homologue, GRIN2BTSS+449kb (Fig. S1F). The TALE no. 1, for target sequence TCAATAAACGTTAACTACAC, did not affect neuronal viability (in contrast to TALE no. 2 which was designed for TAAGACAAACGTCACAGATG). For TALE no. 1, with the exception of a 19 bp run on chromosome 15, no match was found in the mm9 reference genome. Importantly, there were no additional binding sites within 800kb of sequence surrounding the Grin2b TSS, even with a very low filter threshold of up to 3 mismatches. The TALE-transfected cortical neurons showed three days after transfection a significant, ~ 20% increase in Grin2b RNA. These changes were highly specific, because a related NR2 subunit, Grin2a, and the repressive regulator Setdb1, did not show significant changes in expression in transfected neurons. Furthermore, mouse neural crest-derived Neuro2a (N2a) and neuroblastoma × glioma hybrid NG108 cells did not show detectable Grin2b expression in untransfected or TALE-transfected cultures (Fig. 3F). ChIP-PCR with a VP16 antibody to measure TALE-VP64 occupancy confirmed sequence-specific binding at the target in the distal arm of Grin2bTSS+471kb in transfected neurons but not in NG108 or N2a cells (Fig. 3F). This lack of TALE-binding at the target sequence in the two cell lines cannot be explained by incomplete transfection because expression of the GFP tag was readily detectable in all three cell types (Fig. 3F). However, chromatin surrounding the TALE target site showed high levels of the ‘open’ chromatin mark H3K27ac in neurons while levels were much lower for the corresponding sequences in NG108 and N2a cells (Fig. S2E), suggesting that Grin2b chromatin was less accessible in the cell lines. We conclude that active Grin2b expression is sensitive to designer transcription factors binding 471kb downstream from the TSS.

Having shown that higher order chromatin is a key control point for transcriptional regulation of GRIN2B/Grin2b in brain, we next asked whether these mechanisms could play a potential role in cognition and disease. We interrogated the Psychiatric Genome Consortium 2 (PGC2) dataset, with 35,476 schizophrenia (SCZ) and 46,839 control subjects the largest available genome-wide association study to date(Consortium, 2014). Within a 10Mb portion of chromosome 12p encompassing GRIN2B, a single SNP, rs117578877, passed the threshold of P < 10−6, with P = 6.6 × 10−7 and estimated Odds ratio (OR) of 1.15 for the minor (T) allele (Fig. 4A). While rs 117578877 did not reach nominal genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8), we note the stepwise decrease of its P value with successively larger samples as part of earlier versions of the PGC2 analysis(2011; Ripke et al., 2013). Given the low minor allele frequency (cases, 5.18%; controls, 4.62%), future studies in larger cohorts are expected to reach a more definite conclusion on rs117578877 as risk polymorphism. Of note, rs117578877 is positioned in the center of the distal arm of GRIN2BTSS+449kb (Fig. 4A). Therefore, non-contiguous DNA elements bypassing 0.5Mb on the linear genome could contribute to genetic risk for SCZ by interacting with the GRIN2B TSS. We hypothesized that rs117578877 risk allele carriers could show alterations in GRIN2B RNA levels in the context of psychosis and disease. To this end, we screened 227 postmortem brains by PCR-based genotyping and identified 5 SCZ cases and 5 controls carrying the minor allele which confers risk. We measured GRIN2B RNA in the PFC of risk (T) allele carriers, and in 12 SCZ and 12 controls, all C/C homozygotes, for comparison. T-allele carriers with SCZ showed significantly lower GRIN2B RNA levels in comparison to controls matched by genotype. In contrast, cases biallelic for the protective (C) allele showed GRIN2B levels similar to controls and furthermore, rs117578877 did not affect GRIN2B RNA levels within controls (Fig. 4B). These findings, while very preliminary due to the small sample size of the minor allele cohort, suggest that a risk polymorphism in the distal loop arm of GRIN2BTSS+449kb confers decreased GRIN2B expression in the context of SCZ. Because the majority of our disease cases were exposed to antipsychotic medication, we assessed medication effects in a cohort of mice treated for three weeks with daily i.p. injections with the conventional antipsychotic and dopamine D2-like receptor antagonist haloperidol (0.5 mg/kg) or the atypical antipsychotic clozapine (5mg/kg). Consistent with an earlier report(Fatemi et al., 2012), our antipsychotic-exposed mice showed a significant prefrontal up-regulation of catechol-O-methyltransferase (Comt) transcript. In contrast, differences in Grin2b expression and long-range chromosomal loopings between treatment and control groups were minimal (Fig. S3A,B). We conclude that antipsychotic medication likely does not affect Grin2b/GRIN2B expression in cortex.

Figure 4. Intergenic sequences affect cognition and GRIN2B expression.

(A) Regional association plot for 100kb surrounding GRIN2B 3’end, from PGC2 dataset(Consortium, 2014). SNP rs117578877 is within (red box no. 2) distal arm of GRIN2BTSS+449kb. (B) GRIN2B RNA in PFC from N = 12 SCZ and N = 12 control subjects biallelic for major (C) allele and N=5 SCZ and N=5 control minor (T)-allele carriers. *, P < 0.05 (two-tailed t-test) (C) (Left) Spatial working memory strategy and (Right) N-back continuous performance task scores in N=31 C/T heterozygotes compared to N = 794 C/C subjects. Sole T/T subject marked by arrow (mean ± S.E.M., *, **, **** = P < 0.05, 0.005, 00005 (Mann-Whitney). (D) (top) 248 bp from distal arm of GRIN2BTSS+449kb with a total of 15 (N)GG PAM leader sequences for CRISPR/CAS editing. (middle from left to right) Transfected HEK293(FT) cells, showing high transfection efficiency (>95%) by GFP reporter and ~180kDa Cas9 protein immunoblot. Size bar = 100 micron. Representative 5% acrylamide gels showing predicted (Table S3) banding patterns of SURVEYOR nuclease cleavage products in Cas9 nuclease-treated cultures exposed to 13/15 sgRNAs (one sgRNA/transfection) and Cas9 nickase treated cultures exposed to combined sgRNAs 2+7 and sgRNA 2/nuclease-treated cells. (Bottom) DNA sequence and PAM positions (sgRNA 2 and 7, black triangles mark bp position predicted to be the primary target in nickase assays), and electropherograms from (top to bottom) DNA clones of wildtype, sgRNA2/nuclease-exposed and sgRNA2+7/nickase-exposed cells, confirming small 2bp (GT) deletion 5’ to PAM in sgRNA2/nuclease-exposed and much larger deletions and mutations in sgRNA2+7/nickaseexposed cells. Red triangles mark site of mutations. Bar graph (N=3/group, mean ± S.E.M.) showing lower GRIN2B RNA expression after sgRNA2+7/nickase, compared to mock transfected (CRISPR/Cas9 transfected without sgRNA) as control. See also Tables S1–S4 and Figure S3.

To further test whether rs117578877 could impact cognition, we genotyped 826 young healthy males from the Greek LOGOS (Learning on Genetics of Schizophrenia Spectrum) cohort who previously underwent neuropsychological testing across six cognitive domains and personality traits(Roussos et al., 2011a; Roussos et al., 2011b). No genotype-based difference in demographic characteristics was found, and allele distribution was consistent with Hardy-Weinberg expectations (P=0.21) (Table S1). However, the T-allele carriers exhibit worse strategy (P=0.003) on the spatial working memory task and made more errors on the N-back task (3-back: P=6.5×10−5), which remained significant after Bonferroni corrections (Fig. 4C). T-allele carriers had increased schizotypy and self-transcendence (P<0.05) (Table S2), two personality traits frequently associated with schizophrenia spectrum disorders(Ohi et al., 2012; Vollema et al., 2002). Furthermore, the sole biallelic T/T subject was worst among all 826 individuals tested in each of the above tests and questionnaires (Fig. 4C).

These findings suggest that rs117578877, positioned in the distal arm of the GRIN2BTSS+449Kb loop, is associated with liability for cognitive performance and psychosis. Next, we quantified the binding of nuclear proteins extracted from human PFC to sequences encompassing rs117578877. Gel shift assays with extracts from different PFC specimens consistently showed stronger binding for the major (C) allele compared to the risk (T) allele (Fig. S3C,D). Motif loss for CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein (CEBPB), a transcriptional regulator robustly expressed in adult PFC, could contribute to decreased nucleoprotein affinity for the T-allele (Fig. S3C,D). However, regulatory sites often are comprised of multiple enhancer and transcription factor occupancies sequentially arranged within short genomic distance (Dickel et al., 2013; Factor et al., 2014; Smith and Shilatifard, 2014). Therefore, targeted mutations in proximity to the rs117578877 polymorphism also could affect GRIN2B expression. To explore this, we harnessed CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)/RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease (Ran et al., 2013) and transfected (human) GRIN2B-expressing HEK293FT cells altogether with 15 short-guide (sg)-RNAs directed towards NGG motifs and Cas9-PAM recognition elements in 250 base pairs surrounding rs117578877 (Fig. 4D and Table S3). Genome editing activity at the GRIN2B locus was confirmed for 13/15 sgRNAs by DNA heteroduplex-sensitive SURVEYOR nuclease assays and sequencing, typically revealing single or two base pair insertions and deletions 5’ to the NGG motif (Fig. 4D). We then co-transfected sgRNAs 2 and 7 together with a Cas9 nickase mutant, which induces multi-base pair genome modifications by homology-directed repair, and minimizes or eliminates off-target effects compared to nuclease-based genome editing approaches(Ran et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2014). Indeed, sequencing of nickase-treated cultures revealed larger, up to 45bp deletions of sequence positioned between the PAMs of the two sgRNAs. This was associated with a significant, ~ 20–25% decrease in GRIN2B RNA levels (Fig. 4D). Therefore, GRIN2B expression is sensitive to DNA structural variants positioned 449kb distal to the TSS.

Our human studies support the idea that polymorphisms and mutations in loop-bound DNA affect working memory and GRIN2B expression. Therefore, in our final set of experiments, we explored, in mice, the link between Grin2b higher order chromatin and working memory. Alterations in Grin2b expression and activity impact cognition in mice (Tang et al., 1999). Unsurprisingly, we found in multiple cohorts of wildtype C57Bl6 animals exposed to the GRIN2B antagonist Ro25–6981 (10mg/kg i.p.) impairments in spatial working memory as measured by repeat entries (‘errors’) in the 8-arm radial maze (Fig. 5; Fig. S4A). A similar working memory defect was found in drug-naive CK-Setdb1 transgenic mice, compared to littermate controls (Figure 5). This was associated with weakening of long-range loops Grin2bTSS+378kb and Grin2bTSS+471kb and decreased Grin2b RNA and protein in PFC (Fig. 3C,D). These changes in higher order chromatin are due to SETDB1-mediated repression and heterochromatization around the TSS and proximal introns, thereby antagonizing facilitatory effects on neuronal gene expression mediated by long-range loops Grin2bTSS+378kb and Grin2bTSS+471kb (Fig. 2C,F, Fig. 3C; Fig. S2A). We next asked whether similar behavioral phenotypes could be elicited by epigenetic dysregulation other than SETDB1 overexpression. To this end, we discovered that Kmt2a/Mll1 conditional mutant mice subject to CK-Cre mediated deletion in postnatal forebrain neurons showed a significant decrease in prefrontal Grin2b RNA and protein expression (Fig. S4B), in conjunction with impaired working memory in the radial arm maze test (Fig. 5). Of note, Kmt2a/Mll1 (Lysine methyltransferase 2a/Mixed lineage leukemia 1) regulates histone H3K4 methylation which—in sharp contrast to Setdb1-regulated H3K9 methylation and repression—shows broad correlations with open chromatin and active gene expression on a genome-wide scale(Guenther et al., 2005; Gupta et al., 2010; Peter and Akbarian, 2011). Using ChIP-PCR, we measured in PFC of adult CK-Cre,Kmt2a2lox/2lox mice the levels of mono-, di- and tri-methylated H3K4 (H3K4me1/2/3) (Fig. S4C,D). Of note, neuronal loss of Kmt2a in PFC neurons was associated with a specific, approximately 40% decrease of H3K4me1 at Grin2bTSS+378kb. These H3K4me1 changes were significant, in contrast to the moderate decrease in TSS-bound H3K4me3 and H3K4me2. Using 3C ChIP-loop assays, we were able to confirm H3K4me1 enrichment in higher order chromatin associated with Grin2bTSS+378kb in the cerebral cortex (Fig. S4C). Finally, we examined mice deficient for the neuron-specific Baf53b chromatin remodeling subunit. Complete loss of Baf53b is associated with perinatal lethality. Heterozygous Baf53b+/− animals are viable but show severe neuronal dysfunction and defective learning and cognition (Vogel-Ciernia et al., 2013). Interestingly, adult Baf53b+/− cortex maintained normal levels of Grin2b expression and chromosomal loopings (Fig. S4E). These findings would suggest that the alterations in Grin2b expression and higher order chromatin, as observed in CK Setdb1 and CK-Cre/Kmt2a2lox/2lox mutant mice, are specific and not reflective of a generalized response to neuronal disease.

Figure 5.

Spatial working memory showing significant increase in repetitive errors, measured as repeat entries in 8-arm radial maze on 3rd (final) day of testing in (left to right) C57BL6/J mice treated with GRIN2B antagonist RO 25–6981 (10mg/kg) (N=14–18/treatment group), drug-naive CK-Setdb1 transgenic (Tg) mice compared to wildtype (Wt) littermate control (N=12–17/genotype) and CK-Cre, Mll12lox/2lox (M) mice (N=12–16/genotype). Data shown as mean ± S.E.M. *; P < 0.05. See also Figure S4.

DISCUSSION

Spatial Genome Architectures at GRIN2B Play a Role in Transcriptional Regulation

We mapped physical interactions of noncontiguous DNA across 800kb at the GRIN2B (Grin2b) locus on chr. 12 (mouse: chr. 6). Two long range loopings, GRIN2BTSS+348kb ‘and GRIN2BTSS+449kb, or Grin2bTSS+378kb and Grin2bTSS+471kb as their murine homologues, were epigenetically decorated with sharp peaks for the open chromatin marks, H3K27ac, and H3K4me1, which in this combination often define active enhancers(Maston et al., 2012). The GRIN2BTSS+449kb loop carried a cargo of proteins previously reported to promote Grin2b expression, including the Ca2+/cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB)-regulated NRF-1(Herzig et al., 2000) and early-response AP-1(Dhar and Wong-Riley, 2009; Priya et al., 2013; Qiang and Ticku, 2005) transcription factors. Consistent with the definition of a classical promoter/enhancer loop—defined by the mobilization of conserved DNA elements into close proximity of a TSS to facilitate transcription(Ong and Corces, 2011)—the higher order chromatin structures described here were specific for cells expressing GRIN2B, with dynamic co-regulation of loopings and expression in the context of differentiation and increased synaptic activity. It remains to be determined whether these changes in chromosomal conformations occur independently, or in context with other activity-regulated changes in neuronal nuclei, including plasticity in nuclear geometry (Wittmann et al., 2009), mobilization of transcribed genes away from the nuclear lamina and other repressive environments (Walczak et al., 2013), and repositioning into subnuclear territories enriched with the transcriptional initiation complex(Crepaldi et al., 2013) and highly transcribed genes such as the (nuclear encoded) cytochrome c oxidase subunits(Dhar et al., 2009). Furthermore, according to genome-wide estimates, five independent enhancers could regulate the same TSS (Andersson et al., 2014), and therefore is it possible that GRIN2B expression is governed by the two long-range loops described here and additional regulatory sequences positioned 5’ or 3’ from the TSS.

Chromosomal Conformations Affect Cognition

Folding the genome into 3-dimensional chromatin structures is of pivotal importance for neuronal function, with mutations and structural variants in far more than 50 genes, each encoding a different chromatin regulator, now linked to neurodevelopmental syndromes(Ronan et al., 2013) and adult onset hereditary neurodegenerative disease(Jakovcevski and Akbarian, 2012; Klein et al., 2011; Winkelmann et al., 2012). Neurological disease associated with disordered chromatin includes mutations in CTCF, encoding a scaffolding protein implicated in the structural organization of promoter-enhancer loopings(Gregor et al., 2013; Merkenschlager and Odom, 2013). Brain development and cognition are also affected by deleterious mutations in histone methyltransferase encoding genes, including KMT2A/MLL1(Jones et al., 2012) and KMT1E/SETDB1(Cukier et al., 2012). According to our 3C ChIP-loop results, there is robust enrichment for CTCF protein in GRIN2BTSS+449kb loop chromatin. Furthermore, we observed that working memory in mice is dependent on normal levels of Grin2b expression and affected by changes in higher order chromatin caused by decreased H3K4 monomethylation at distal loop elements after neuronal ablation of Kmt2a methyltransferase, and by excessive, Kmt1e/Setdb1 transgene-mediated H3K9 trimethylation at repressor sequences ~ 30–40kb downstream from the TSS. These intronic sequences were enriched for heterochromatin-associated protein 1 (HP-1α) in the context of increased occupancy of KMT1E/SETDB1 histone H3K9 methyltransferase promoting local chromatin compaction(Mund et al., 2012; Verschure et al., 2005). Our findings point to highly complex regulation of the spatial genome architectures at the GRIN2B/Grin2b locus, defined by dynamic competition of multiple loopings competing for access to gene-proximal regulatory sequences, in order to facilitate or repress expression (Figure 2F). Therefore, disruption in 3-dimensional genome organization, including but not limited to the GRIN2B locus, could severely impact neuronal functions after mutations in CTCF, KMT2A/MLL1, KMT1E/SETDB1 and probably additional chromatin regulators associated with cognitive and psychiatric disease(Takata et al., 2014).

Changes in Grin2b expression and activity profoundly affect memory and cognition(Tang et al., 1999; von Engelhardt et al., 2008), while mutations and microdeletions encompassing the GRIN2B locus are associated with schizophrenia and autism(Endele et al., 2010; Jia et al., 2012; Talkowski et al., 2012). The present study extends these findings and describes how higher order chromatin encompassing the GRIN2B locus adds further liability to cognitive impairments. This includes an intergenic SNP, rs117578877, which in the 826 subjects of the LOGOS cohort was linked to working memory performance and psychosis-related personality traits. In addition, GRIN2B RNA levels were decreased in PFC of risk allele carriers diagnosed with SCZ, and multi-base pair deletion in close proximity to this polymorphism negatively affected GRIN2B expression in HEK cells. Interestingly, an earlier GWAS study measuring working memory in 750 subjects reported rs2160519, positioned within 3kb from the distal arm of GRIN2BTSS+348kb, as 3rd top scoring SNP genome-wide(Need et al., 2009). Additional SNPs, positioned at the TSS and around repressive SETDB1 target sequences, conferred significant effects on memory function in a third study with 330 subjects(de Quervain and Papassotiropoulos, 2006) (Fig. S3E). These studies, taken together with the findings presented here, strongly suggest that multiple loop-bound sequence variants affect GRIN2B expression and cognition.

It is remarkable that, according to our results, NMDA receptor gene expression could be modulated by a TALE-based designer transcription factor in mouse cortical neurons—and by CRISPR/Cas-induced multibase pair excisions in HEK cells—that both were targeted to intergenic DNA separated by approximately 0.5Mb from the GRIN2B/Grin2b TSS. While the resulting changes in expression, particularly in case of our TALE-VP64 transcription factor, were modest, our results mark a significant extension from the previously reported epigenomic editing of Drosophila enhancers located within 10kb from their target genes(Crocker and Stern, 2013). We predict that the molecular toolbox for future treatments of cognitive and psychiatric disease will include targeted editing of long-range enhancer elements regulating gene expression critical for neuronal plasticity and behavior.

Experimental Procedures

Chromosome conformation capture (3C)

Cerebral cortex (approximately 300 mg/human postmortem specimen or unilateral mouse cortical hemisphere) or cultured cells (up to 107 cells) were crosslinked for 15 min in PBS-buffered, 1.5% formaldehyde, then digested with Hind III restriction enzyme (NEB) at 37°C overnight, washed, and treated with T4 DNA ligase at 16°C for 4 h followed by by DNA extraction and purification using standard protocols. 3C primers were 30–32 bp in length and positioned within 200 bp of HindIII cut sites. Sequence-verified PCR products were measured semi-quantitatively with UVP Bioimaging system/Labworks 4.5 software.

TALE-based designer transcription factor

Two Transcription Activator-Like Element DNA-binding proteins (TALE), fused to four tandem copies of the Herpes simplex Viral protein 16, amino acids 437–447, DALDDFDLDML connected with glycine-serine linkers, were targeted to intergenic sequences in the mouse genome, 471 kb downstream of the Grin2b TSS using the TALE tool box kit (Addgene). Sequence confirmed clones were transfected into mouse primary cortical neurons (E17) at DIV 4 and RNA extracted 72 hours post-transfection.

Genome Editing

To induce mutations in DNA surrounding rs117578877, 15 sgRNAs were identified by searching for the G(N)20 GG motifs that conform with the nucleotide requirements for U6 Pol III transcription and the spCas9 PAM recognition element (PAM) (Ran et al., 2013), and corresponding oligonucleotides cloned into pX330 vector (Addgene), sequence confirmed, transfected into HEK293FT cells. 72 hours post-transfection, genomic DNA was extracted to verify CRISPR-Cas9 mediated editing by using the mismatch-sensitive SURVEYOR nuclease assay (Ran et al., 2013). A subset of sgRNAs with confirmed editing activity in the SURVEYOR assay were subsequently used in double nicking assays using Addgene’s pX335 vector.

A detailed description of all experimental procedures, the neuropsychological test cohort (LOGOS), postmortem brain samples, mutant mice and cell lines is provided in the Supplemental Material.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01 MH086509 and P50 MH096890 (S.A.), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant R01 NS073947-04 (R.M.), National Institute of Drug Abuse grant R01 DA036984 (M.W., S.A.), NIH Brain and Tissue Repository grant HHSN271201300031C & the VA, and Veterans Affairs Merit grant BX002395, BBRF, the APA-Merck & Co. Early Academic Career Research Award (P.R.), the Connecticut State Stem Cell Research Program (09-SCB-UCON-18) (T.P.R.), the Whitehall Foundation (K.F.) and the University of Crete Research Funds Account (E.L.K.E.1348).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors thank the participants and the personnel of the Military Training Camp of Candidate, Supply Army officers (SEAP) in Heraklion, Crete for their help with the LOGOS study. The authors report no conflicts.

Author contributions: Conducted experiments: R.B., C.P., Y.J., E.S., A.M., W.M., A.S., V.P., C.W. (iPS work) and A.V.-C.(nBAF mice). Analyzed data: R.B, C.P., Y.J., A.D., M.J., W.M. LOGOS data analyses and genotyping: P.R., P.B., S.G. Provided resources: P.D.G., S.G., P.S., V.H., C.T., T.P.R., R.H.M., P.E., K.F., M.A.W., S.A. Conceived and designed experiments: R.B., C.P., Y.J., P.R., S.A.

References

- Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nature genetics. 2011;43:969–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A promoter-level mammalian expression atlas. Nature. 2014;507:462–470. doi: 10.1038/nature13182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson R, Gebhard C, Miguel-Escalada I, Hoof I, Bornholdt J, Boyd M, Chen Y, Zhao X, Schmidl C, Suzuki T, et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature. 2014;507:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalew M, Le-Niculescu H, Levey DF, Jain N, Changala B, Patel SD, Winiger E, Breier A, Shekhar A, Amdur R, et al. Convergent functional genomics of schizophrenia: from comprehensive understanding to genetic risk prediction. Molecular psychiatry. 2012;17:887–905. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji J, Rusconi S, Schaffner W. Expression of a beta-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell. 1981;27:299–308. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli RR, Segal DJ, Dreier B, Barbas CF., 3rd Toward controlling gene expression at will: specific regulation of the erbB-2/HER-2 promoter by using polydactyl zinc finger proteins constructed from modular building blocks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:14628–14633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Birney E, Dunham I, Green ED, Gunter C, Snyder M. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj R, Jiang Y, Mao W, Jakovcevski M, Dincer A, Krueger W, Garbett K, Whittle C, Tushir JS, Liu J, et al. Conserved chromosome 2q31 conformations are associated with transcriptional regulation of GAD1 GABA synthesis enzyme and altered in prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:11839–11851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1252-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch J, Scholze H, Schornack S, Landgraf A, Hahn S, Kay S, Lahaye T, Nickstadt A, Bonas U. Breaking the code of DNA binding specificity of TAL-type III effectors. Science. 2009;326:1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1178811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung I, Shulha HP, Jiang Y, Matevossian A, Wang J, Weng Z, Akbarian S. Developmental regulation and individual differences of neuronal H3K4me3 epigenomes in the prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:8824–8829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001702107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowney EJ, LeGros MA, Mosley CP, Clowney FG, Markenskoff-Papadimitriou EC, Myllys M, Barnea G, Larabell CA, Lomvardas S. Nuclear aggregation of olfactory receptor genes governs their monogenic expression. Cell. 2012;151:724–737. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological Insights from 108 Schizophrenia-Associated Genetic Loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaldi L, Policarpi C, Coatti A, Sherlock WT, Jongbloets BC, Down TA, Riccio A. Binding of TFIIIC to sine elements controls the relocation of activity-dependent neuronal genes to transcription factories. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Stern DL. TALE-mediated modulation of transcriptional enhancers in vivo. Nature methods. 2013;10:762–767. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukier HN, Lee JM, Ma D, Young JI, Mayo V, Butler BL, Ramsook SS, Rantus JA, Abrams AJ, Whitehead PL, et al. The expanding role of MBD genes in autism: identification of a MECP2 duplication and novel alterations in MBD5, MBD6, and SETDB1. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research. 2012;5:385–397. doi: 10.1002/aur.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Laat W, Grosveld F. Spatial organization of gene expression: the active chromatin hub. Chromosome research : an international journal on the molecular, supramolecular and evolutionary aspects of chromosome biology. 2003;11:447–459. doi: 10.1023/a:1024922626726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ, Papassotiropoulos A. Identification of a genetic cluster influencing memory performance and hippocampal activity in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:4270–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510212103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar SS, Ongwijitwat S, Wong-Riley MT. Chromosome conformation capture of all 13 genomic Loci in the transcriptional regulation of the multisubunit bigenomic cytochrome C oxidase in neurons. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:18644–18650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar SS, Wong-Riley MT. Coupling of energy metabolism and synaptic transmission at the transcriptional level: role of nuclear respiratory factor 1 in regulating both cytochrome c oxidase and NMDA glutamate receptor subunit genes. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:483–492. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3704-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickel DE, Visel A, Pennacchio LA. Functional anatomy of distant-acting mammalian enhancers. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological sciences. 2013;368:20120359. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JR, Selvaraj S, Yue F, Kim A, Li Y, Shen Y, Hu M, Liu JS, Ren B. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. 2012;485:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endele S, Rosenberger G, Geider K, Popp B, Tamer C, Stefanova I, Milh M, Kortum F, Fritsch A, Pientka FK, et al. Mutations in GRIN2A and GRIN2B encoding regulatory subunits of NMDA receptors cause variable neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nature genetics. 2010;42:1021–1026. doi: 10.1038/ng.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factor DC, Corradin O, Zentner GE, Saiakhova A, Song L, Chenoweth JG, McKay RD, Crawford GE, Scacheri PC, Tesar PJ. Epigenomic comparison reveals activation of "seed" enhancers during transition from naive to primed pluripotency. Cell stem cell. 2014;14:854–863. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallin MD, Lasseter VK, Avramopoulos D, Nicodemus KK, Wolyniec PS, McGrath JA, Steel G, Nestadt G, Liang KY, Huganir RL, et al. Bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia: a 440-single-nucleotide polymorphism screen of 64 candidate genes among Ashkenazi Jewish case-parent trios. American journal of human genetics. 2005;77:918–936. doi: 10.1086/497703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Folsom TD, Reutiman TJ, Novak J, Engel RH. Comparative gene expression study of the chronic exposure to clozapine and haloperidol in rat frontal cortex. Schizophrenia research. 2012;134:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaszner M, Felsenfeld G. Insulators: exploiting transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:703–713. doi: 10.1038/nrg1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein MB, Kundaje A, Hariharan M, Landt SG, Yan KK, Cheng C, Mu XJ, Khurana E, Rozowsky J, Alexander R, et al. Architecture of the human regulatory network derived from ENCODE data. Nature. 2012;489:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nature11245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavi-Helm Y, Klein FA, Pakozdi T, Ciglar L, Noordermeer D, Huber W, Furlong EE. Enhancer loops appear stable during development and are associated with paused polymerase. Nature. 2014;512:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature13417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor A, Oti M, Kouwenhoven EN, Hoyer J, Sticht H, Ekici AB, Kjaergaard S, Rauch A, Stunnenberg HG, Uebe S, et al. De novo mutations in the genome organizer CTCF cause intellectual disability. American journal of human genetics. 2013;93:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther MG, Jenner RG, Chevalier B, Nakamura T, Croce CM, Canaani E, Young RA. Global and Hox-specific roles for the MLL1 methyltransferase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:8603–8608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503072102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Kim SY, Artis S, Molfese DL, Schumacher A, Sweatt JD, Paylor RE, Lubin FD. Histone methylation regulates memory formation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:3589–3599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3732-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmston N, Lenhard B. Chromatin and epigenetic features of long-range gene regulation. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:7185–7199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig RP, Scacco S, Scarpulla RC. Sequential serum-dependent activation of CREB and NRF-1 leads to enhanced mitochondrial respiration through the induction of cytochrome c. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:13134–13141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.13134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakovcevski M, Akbarian S. Epigenetic mechanisms in neurological disease. Nature medicine. 2012;18:1194–1204. doi: 10.1038/nm.2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia P, Wang L, Fanous AH, Pato CN, Edwards TL, Zhao Z. Network-assisted investigation of combined causal signals from genome-wide association studies in schizophrenia. PLoS computational biology. 2012;8:e1002587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Jakovcevski M, Bharadwaj R, Connor C, Schroeder FA, Lin CL, Straubhaar J, Martin G, Akbarian S. Setdb1 histone methyltransferase regulates mood-related behaviors and expression of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:7152–7167. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1314-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones WD, Dafou D, McEntagart M, Woollard WJ, Elmslie FV, Holder-Espinasse M, Irving M, Saggar AK, Smithson S, Trembath RC, et al. De novo mutations in MLL cause Wiedemann-Steiner syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 2012;91:358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CJ, Botuyan MV, Wu Y, Ward CJ, Nicholson GA, Hammans S, Hojo K, Yamanishi H, Karpf AR, Wallace DC, et al. Mutations in DNMT1 cause hereditary sensory neuropathy with dementia and hearing loss. Nat Genet. 2011;43:595–600. doi: 10.1038/ng.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M, Cattoglio C, Tjian R. Looping back to leap forward: transcription enters a new era. Cell. 2014;157:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Harju S, Peterson KR. Locus control regions: coming of age at a decade plus. Trends in genetics : TIG. 1999;15:403–408. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01780-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher B. ENCODE: The human encyclopaedia. Nature. 2012;489:46–48. doi: 10.1038/489046a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martucci L, Wong AH, De Luca V, Likhodi O, Wong GW, King N, Kennedy JL. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor NR2B subunit gene GRIN2B in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Polymorphisms and mRNA levels. Schizophrenia research. 2006;84:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maston GA, Landt SG, Snyder M, Green MR. Characterization of enhancer function from genome-wide analyses. Annual review of genomics and human genetics. 2012;13:29–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090711-163723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkenschlager M, Odom DT. CTCF and cohesin: linking gene regulatory elements with their targets. Cell. 2013;152:1285–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AC, Bharadwaj R, Whittle C, Krueger W, Mirnics K, Hurd Y, Rasmussen T, Akbarian S. The Genome in Three Dimensions: A New Frontier in Human Brain Research. Biological psychiatry. 2014;75:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscou MJ, Bogdanove AJ. A simple cipher governs DNA recognition by TAL effectors. Science. 2009;326:1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1178817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mund A, Schubert T, Staege H, Kinkley S, Reumann K, Kriegs M, Fritsch L, Battisti V, Ait-Si-Ali S, Hoffbeck AS, et al. SPOC1 modulates DNA repair by regulating key determinants of chromatin compaction and DNA damage response. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:11363–11379. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Need AC, Attix DK, McEvoy JM, Cirulli ET, Linney KL, Hunt P, Ge D, Heinzen EL, Maia JM, Shianna KV, et al. A genome-wide study of common SNPs and CNVs in cognitive performance in the CANTAB. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18:4650–4661. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Roak BJ, Vives L, Fu W, Egertson JD, Stanaway IB, Phelps IG, Carvill G, Kumar A, Lee C, Ankenman K, et al. Multiplex targeted sequencing identifies recurrently mutated genes in autism spectrum disorders. Science. 2012;338:1619–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1227764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohi K, Hashimoto R, Yasuda Y, Fukumoto M, Yamamori H, Iwase M, Kazui H, Takeda M. Personality traits and schizophrenia: evidence from a case-control study and meta-analysis. Psychiatry research. 2012;198:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong CT, Corces VG. Enhancer function: new insights into the regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Nature reviews Genetics. 2011;12:283–293. doi: 10.1038/nrg2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter CJ, Akbarian S. Balancing histone methylation activities in psychiatric disorders. Trends in molecular medicine. 2011;17:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya A, Johar K, Wong-Riley MT. Nuclear respiratory factor 2 regulates the expression of the same NMDA receptor subunit genes as NRF-1: both factors act by a concurrent and parallel mechanism to couple energy metabolism and synaptic transmission. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1833:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang M, Ticku MK. Role of AP-1 in ethanol-induced N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor 2B subunit gene up-regulation in mouse cortical neurons. Journal of neurochemistry. 2005;95:1332–1341. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nature protocols. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razin SV, Gavrilov AA, Ioudinkova ES, Iarovaia OV. Communication of genome regulatory elements in a folded chromosome. FEBS letters. 2013;587:1840–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripke S, O'Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran JL, Kahler AK, Akterin S, Bergen SE, Collins AL, Crowley JJ, Fromer M, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nature genetics. 2013;45:1150–1159. doi: 10.1038/ng.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronan JL, Wu W, Crabtree GR. From neural development to cognition: unexpected roles for chromatin. Nature reviews Genetics. 2013;14:347–359. doi: 10.1038/nrg3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos P, Giakoumaki SG, Adamaki E, Bitsios P. The influence of schizophrenia-related neuregulin-1 polymorphisms on sensorimotor gating in healthy males. Biological psychiatry. 2011a;69:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos P, Giakoumaki SG, Adamaki E, Georgakopoulos A, Robakis NK, Bitsios P. The association of schizophrenia risk D-amino acid oxidase polymorphisms with sensorimotor gating, working memory and personality in healthy males. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011b;36:1677–1688. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw G, Morse S, Ararat M, Graham FL. Preferential transformation of human neuronal cells by human adenoviruses and the origin of HEK 293 cells. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2002;16:869–871. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0995fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Zhang W, Zhang J, Zhou J, Wang J, Chen L, Wang L, Hodgkins A, Iyer V, Huang X, et al. Efficient genome modification by CRISPR-Cas9 nickase with minimal off-target effects. Nature methods. 2014;11:399–402. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Shilatifard A. Enhancer biology and enhanceropathies. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2014;21:210–219. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata A, Xu B, Ionita-Laza I, Roos JL, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. Loss-of-function variants in schizophrenia risk and SETD1A as a candidate susceptibility gene. Neuron. 2014;82:773–780. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talkowski ME, Rosenfeld JA, Blumenthal I, Pillalamarri V, Chiang C, Heilbut A, Ernst C, Hanscom C, Rossin E, Lindgren AM, et al. Sequencing chromosomal abnormalities reveals neurodevelopmental loci that confer risk across diagnostic boundaries. Cell. 2012;149:525–537. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YP, Shimizu E, Dube GR, Rampon C, Kerchner GA, Zhuo M, Liu G, Tsien JZ. Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature. 1999;401:63–69. doi: 10.1038/43432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman RE, Rynes E, Humbert R, Vierstra J, Maurano MT, Haugen E, Sheffield NC, Stergachis AB, Wang H, Vernot B, et al. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nature11232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschure PJ, van der Kraan I, de Leeuw W, van der Vlag J, Carpenter AE, Belmont AS, van Driel R. In vivo HP1 targeting causes large-scale chromatin condensation and enhanced histone lysine methylation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:4552–4564. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4552-4564.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel-Ciernia A, Matheos DP, Barrett RM, Kramar EA, Azzawi S, Chen Y, Magnan CN, Zeller M, Sylvain A, Haettig J, et al. The neuron-specific chromatin regulatory subunit BAF53b is necessary for synaptic plasticity and memory. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16:552–561. doi: 10.1038/nn.3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollema MG, Sitskoorn MM, Appels MC, Kahn RS. Does the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire reflect the biological-genetic vulnerability to schizophrenia? Schizophrenia research. 2002;54:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Engelhardt J, Doganci B, Jensen V, Hvalby O, Gongrich C, Taylor A, Barkus C, Sanderson DJ, Rawlins JN, Seeburg PH, et al. Contribution of hippocampal and extra-hippocampal NR2B-containing NMDA receptors to performance on spatial learning tasks. Neuron. 2008;60:846–860. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak A, Szczepankiewicz AA, Ruszczycki B, Magalska A, Zamlynska K, Dzwonek J, Wilczek E, Zybura-Broda K, Rylski M, Malinowska M, et al. Novel higher-order epigenetic regulation of the Bdnf gene upon seizures. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:2507–2511. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1085-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert CS, Fung SJ, Catts VS, Schofield PR, Allen KM, Moore LT, Newell KA, Pellen D, Huang XF, Catts SV, et al. Molecular evidence of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor hypofunction in schizophrenia. Molecular psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann J, Lin L, Schormair B, Kornum BR, Faraco J, Plazzi G, Melberg A, Cornelio F, Urban AE, Pizza F, et al. Mutations in DNMT1 cause autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness and narcolepsy. Hum Mol Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Queisser G, Eder A, Wiegert JS, Bengtson CP, Hellwig A, Wittum G, Bading H. Synaptic activity induces dramatic changes in the geometry of the cell nucleus: interplay between nuclear structure, histone H3 phosphorylation, and nuclear calcium signaling. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:14687–14700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1160-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AJ, Severson AF, Meyer BJ. Condensin and cohesin complexity: the expanding repertoire of functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:391–404. doi: 10.1038/nrg2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou VW, Goren A, Bernstein BE. Charting histone modifications and the functional organization of mammalian genomes. Nature reviews Genetics. 2011;12:7–18. doi: 10.1038/nrg2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Adli M, Zou JY, Verstappen G, Coyne M, Zhang X, Durham T, Miri M, Deshpande V, De Jager PL, et al. Genome-wide chromatin state transitions associated with developmental and environmental cues. Cell. 2013;152:642–654. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.