Abstract

Background

Psychotherapy for youth with mood dysregulation can help to stabilize mood and improve functioning, but the neural mechanisms of this improvement are not known. In this study we investigated changes in brain activation underlying improvement in mood symptoms.

Methods

Twenty-four subjects (ages 13–17) participated: 12 patients with clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or mania, and 12 healthy comparison subjects (HC) matched for age and sex. All subjects completed functional magnetic resonance imaging while viewing facial expressions. The patients then received up to 4 months of psychotherapy and were rescanned at end of treatment. Whole brain differences between patient and control groups were assessed with a voxel wise analysis. Changes in activation from pre to post treatment within the patient group were tested for correlation with changes in mood symptoms

Results

At baseline the patient group had hypoactivation in the DLPFC and hyperactivation in the posterior cingulate cortex compared to the HC group. Between pre- and post-treatment activation increased in the DLPFC and decreased in the amygdala. Increases in DLPFC activation were significantly correlated with improvement in mania symptoms.

Discussion

Enhancement of frontal executive control brain regions may underlie improvement in mood dysregulation in pediatric patients at familial risk for bipolar disorder.

Keywords: fMRI, bipolar, psychotherapy, prefrontal, pediatric

Introduction

Retrospective studies in adults suggest that bipolar disorder (BD) begins in childhood in 15% to 28% of cases and adolescence in 50% to 66% of cases (Perlis et al. 2004). Especially vulnerable to developing BD are those youth who are experiencing symptoms of mood dysregulation and also have a parent with BD. Nearly half of these patients will develop a diagnosis of BD I or II during the 4–5 years following assessment (Axelson et al. 2011) therefore they are considered to be at high risk for BD (HRforBD). Regardless of whether they develop BD, youth in the HRforBD group have mood dysregulation symptoms that cause significant problems with functioning and a lower quality of life (Birmaher et al. 2009; Carlson et al. 2009; Luby and Navsaria 2010). Therefore it is important that we implement treatments that stabilize mood and improve functioning for HRforBD youth. Furthermore by seeking to understand the mechanisms of successful mood stabilizing therapies we may be able to identify biomarkers that could lead to individualized therapies. Recently we reported that psychotherapeutic intervention helps to stabilize symptoms of mood dysregulation in HRforBD (Miklowitz et al. 2011). For the current study we aim to identify the mechanisms of clinical improvement by examining pre- versus post-treatment changes in brain activation.

Treatments for BD or HRforBD may target the brain regions that have been reported to be abnormal in these populations. A substantial literature shows that functional brain abnormalities in pediatric BD include hypoactivation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) and hyperactivation of amygdala (Brotman et al. 2013; K. D. Chang et al. 2008; K. Chang et al. 2009; Frazier et al. 2005; Garrett et al. 2012; Rich et al. 2008; L. A. Thomas et al. 2013). These brain regions also may be functioning abnormally in youth at risk for BD (Olsavsky et al. 2012).

Investigations of the neural mediators of pharmacological treatments do, in fact, implicate the same regions. For example, divalproex treatment of youth with mood dysregulation is associated with decreased dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) activation, which is correlated with decreased symptoms of depression (K. Chang et al. 2009). For youth with a diagnosis of BD, lamotrigine treatment is associated with increased activation in the VLPFC and reduced activation in the amygdala, both of which were correlated with improvement in YMRS scores (Passarotti et al. 2011). Similarly, our lab reported decreased amygdala activation in youth with BD who were treated with lamotrigine, although activation was correlated with decreased severity of depression rather than mania symptoms (K. D. Chang et al. 2008). In another report, amygdala activation did not change following treatment with risperidone or divalproex, but higher amygdala activation at pre-treatment predicted less improvement in symptoms of mania (Pavuluri et al. 2011).

Psychotherapy may utilize some of the same mechanisms as pharmacological treatments. Very few studies have examined the effects of psychotherapy on brain activation in youth with BD or at HRforBD. One such study examined depressed youth with BD undergoing treatment with a variety of medications and psychotherapies and found that activation decreased in the occipital cortex and increased in the insula, cerebellum, and VLPFC, but these changes were not correlated with changes in depression (Diler et al. 2013). No studies so far have looked at the effects of psychotherapy on brain activation among youth with HRforBD. Based on the literature reviewed above, we hypothesized that changes in mood symptom severity following psychotherapy would be associated with changes in the DLPFC, VLPFC, and amygdala, suggesting that these regions may mediate improvement in mood symptoms.

Methods

Participants

The study was approved by the Stanford University and University of Colorado Institutional Review Boards and written consent or assent was obtained from all participants. Thirteen patients were recruited from among those participating in a larger treatment study that was described in a previous publication (Miklowitz et al. 2011). Criteria for inclusion were (1) age 9–17; (2) English-speaking; (3) at least one first-degree relative with BD I or BD II; (4) significant current mood symptoms, defined as a score >11 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Young et al. 1978), OR a score >29 on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale Revised (CDRS-R) (Mayes et al. 2010); (5) no previous manic episode according to DSM-IV criteria. Exclusion criteria (for both controls and patients) included developmental disorders, neurological conditions or major medical illness, substance use disorder, IQ less than 80, MRI contraindications (metal in the body), orthodontic braces, or current hospitalization. One patient was excluded for unusable MRI data due to excessive motion artifact, leaving 12 patients in the final sample.

Healthy control subjects were selected from a group of 29 participants enrolled in a concurrent study in our laboratory. These volunteers had been scanned on the same MRI scanner using identical protocols during the same time period. Baseline but not follow-up scans were available. We selected the control subjects to be individually matched by age, sex, and IQ to each subject in the treatment study. They were free from current or past DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses, were not taking psychotropic medications, had both parents without any psychiatric diagnosis (determined by the MINI), and did not have a first- or second-degree relative with BD.

Clinical Assessments

The YMRS and CDRS was administered by reliable trained raters, both before and after treatment, and used as the primary outcome measures for correlation with fMRI data. For both patients and healthy controls, diagnoses were assessed by reliable trained raters using the affective module of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) (B. G. Geller et al. 1996; B. Geller et al. 2001) as well as all modules of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children - Present and Lifetime (K-SADS-PL) (Kaufman et al. 1997). Parental diagnosis of BD I or II was confirmed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (Sheehan et al. 1998). DSM-IV diagnoses were ultimately determined by a board certified child psychiatrist or psychologist. For all participants, IQ was assessed with the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) (Psychological-Corporation 1999).

Psychotherapy

The psychotherapy treatment was either family focused therapy or a comparison treatment-as-usual administered for up to 16 weekly sessions as described in the previous publication (Miklowitz et al. 2011). Both of these treatments included psychoeducation and mood stabilization plus medication management as needed. The study recruited and treated patients from two sites: Stanford University (P.I. Kiki Chang) and the University of Colorado (P.I. David Miklowitz, currently at UCLA), but all patients were scanned at Stanford.

FMRI scan parameters

All scans were collected on a 3T GE Signa Excite (General Electric Co., Milwaukee, WI) scanner using a custom-built head coil and a spiral-in/out fMRI pulse sequence (Glover and Law 2001). The following parameters were used: TR = 2000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 80 degrees; 30 axial slices, 4mm thick, 0.5 mm skip, field of view = 22 cm, 64x64 matrix, in-plane spatial resolution = 3.44 mm. A high resolution structural image was also collected to help normalize the images to a standard template (fast spoiled gradient recalled (3DFSPGR) pulse sequence: TR / TE / TI = 5.9 / 1.5 / 300 ms, flip angle=15 degrees, field of view =22 cm, 256x256 matrix, inplane resolution =0.86 mm2, and slice thickness=1.5 mm).

Facial Expression Task

Emotional facial expressions were presented in a block design including fearful faces from the McArthur (‘NimStim’) stimulus set (macbrain.org/resources.htm) and a ‘scrambled’ picture baseline condition that controlled for viewing a complex visual stimuli and motor responses. Four (non-repeated) blocks of each condition were shown, and each block contained 8 pictures. Each picture was shown for 3 seconds with no inter-stimulus interval. Subjects pressed button 1 for female and button 2 for male models, therefore this was an implicit emotion processing task. Subjects alternately pushed buttons 1 and 2 for the scrambled stimuli. Participants viewed stimuli by looking directly up into a mirror attached to the head coil, which reflected the projection screen mounted at the foot of the scanner. Stimuli were presented using ePrime software (www.pstnet.com), which also collected responses.

FMRI whole brain voxel-wise analysis

Functional data were processed and statistically analyzed using SPM5 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK). Images were spatially realigned, motion-corrected, and spatially normalized into MNI stereotactic space, and smoothed with a Gaussian filter (7mm full width at half-maximum). The ArtRepair toolbox (http://cibsr.stanford.edu/tools/human-brain-project/artrepair-software.html) was used to repair motion artifacts, defined as rapid scan-to-scan motion greater than 0.5mm/TR, translation greater than 3 mm, or global signal intensity fluctuations greater than 1.5%. Image volumes containing artifacts were replaced with a volume interpolated from the surrounding (unrepaired) scans. A subject’s data were removed from further analysis if more than 25% of volumes in the fMRI series required repair.

Whole brain statistical analyses were performed in SPM5 using the General Linear Model and Random Field Theory. Fixed effects models were constructed for each subject, modeled as 24 second blocks convolved with the hemodynamic response function. A 120 sec FWHM high-pass temporal filter removed slow signal drift artifacts. This analysis identified activation associated with the contrast of fearful faces minus scrambled images. We used scrambled images rather than neutral faces as our comparison condition because previous studies have reported that neutral faces activate the amygdala in adolescent subjects (Rich et al. 2006; K. M. Thomas et al. 2001), possibly because they are ambiguous or can be construed as negative or threatening by young people who are less experienced than adults at identifying facial emotions.

Group Analyses: 3 steps

Comparing HRforBD to HC at Baseline: A whole brain voxel-wise independent groups t-test in SPM5 was used to compare the HRforBD group (baseline scans) to the HC group. Individual subject contrast images were combined into a group analysis using a random effects model. A cluster-level threshold FDR corrected for multiple comparisons at p<.05 (p<0.005 height, cluster extent=20) was used for voxel-wise whole brain analyses (Lieberman and Cunningham 2009). Coordinates were converted from MNI space into Talairach space (http://imaging.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/imaging/MniTalairach/) and Talairach daemon software (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/tal-daemon/) was used to identify neuroanatomical locations of the clusters.

Comparing Pre-treatment to Post-treatment scans in the HRforBD group: A whole brain voxel-wise repeated-measures t-test in SPM5 was used to test for changes in activation (pre versus post treatment) in the a priori regions of interest. Based on previous studies of brain abnormalities in youth with BD or at risk for BD, we hypothesized changes in the DLPFC, the VLPFC, and the amygdala. To avoid Type II error in these regions, we used a more inclusive threshold of p=.01 uncorrected at the voxel level, which corresponds to Z>2.3, as has been used in neuroimaging studies of cognitive treatment effects using similar sample sizes (Dichter et al. 2010). The location of clusters passing this threshold was confirmed to be in the DLPFC, VLPFC, or amygdala using xjview software (http://www.alivelearn.net/xjview8/).

Correlating changes in activation with changes in symptoms: To determine whether changes in activation in the DLPFC, VLPFC, or amygdala were associated with clinical improvement (rather than non-clinical factors such as habituation or familiarity with the stimuli) we performed a Spearman’s nonparametric correlation in SPSS v.20 software. Mean activation in each cluster in the DLPFC, VLPFC, and amygdala at pre-treatment and at post-treatment was extracted using the Response Exploration (REX) toolbox (www.neuroimaging.org.au/nig/rex). Change in activation was computed as pre-treatment activation minus post-treatment activation. Change in symptom severity for the YMRS and CDRS was computed as pretreatment score minus post-treatment score. Correlation analyses in SPSS software included, for each ROI: (1) change in activation correlated with change in symptom severity; and (2) pre-treatment activation correlated with change in symptom severity. The threshold for significance was adjusted for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction. This procedure of correlating activation with changes in symptoms is not ‘double dipping’ because symptom severity scores are independent of the fMRI analysis that identified activation clusters (Vul and Pashler 2012).

RESULTS

Participant Demographics and Task Performance Results

The HC group did not differ from the HRforBD group in terms of age, sex, or IQ (Table 1). As expected, task performance was highly accurate in both groups with no difference between groups. From pre-treatment to post-treatment there were no changes in task performance accuracy (F=2.19, p=.17) or response time (F=2.02, p=.19) in the HRforBD group. FMRI data from one participant was rejected for excessive motion, leaving 12 subjects in the HRforBD group.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| High Risk for Bipolar Disorder (N=12) | Archived Healthy Controls (N=12) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 13.55 (3.40) | 13.59 (3.01) | .98 |

| Full scale IQ, mean (SD) | 110.50 (10.5) | 112 (9.3) | .72 |

| Female/Male | 8 male and 4 female | 8 male and 4 female | same |

| Right handed / Left handed Or ambidextrous | 9 right, 2 left, 1 ambidextrous | 11 right and 1 left | .47 |

| Faces Task Accuracy (percent correct; mean (SD) | 95.9 (5.6) | 95.6 (5.8) | .89 |

| Faces Task Response Time (milliseconds, mean (SD) | 883.5 (137.9) | 828.14 (170.60) | .39 |

| Diagnoses (number out of 12) | |||

| BD NOS | 5 | - | - |

| MDD | 7 | - | - |

| ADHD | 6 | - | - |

| Anxiety disorder | 6 | - | - |

| CD or ODD | 3 | - | - |

| Cyclothymia | 1 | - | - |

| Medication* | 6 | - | - |

| CDRS pre-treatment mean (SD) | 39.08 (5.8) | - | - |

| CDRS post-treatment mean (SD) | 34.08 (8.6) | - | - |

| YMRS pre-treatment mean (SD) | 13.42 (5.5) | - | - |

| YMRS post-treatment mean (SD) | 9.67 (5.3) | - | - |

Medications at Baseline: 1 taking divalproex, aripiprazole and a stimulant, 2 taking lithium; 1 taking a stimulant, 1 taking aripiprazole, a stimulant and antidepressant, 1 taking antidepressant. Changes in medication during treatment: 1 added an anti-anxiety medication by end of treatment, 1 added lamotrigine and an antidepressant by visit 3; 1 added ziprasidone and an antidepressant by end of treatment; 1 added risperidone by visit 2; 1 stopped taking antidepressants by month 3 of treatment.

Changes in Symptom Severity from Pre-treatment to Post-treatment

The greatest clinical improvement was observed in symptoms of mania: Five patients improved 50% or more in YMRS scores, and 2 patients improved 25% or more. The mean YMRS score was 13.42 (standard deviation (SD) =5.5) at pre-treatment and 9.67 (SD=5.3) at post-treatment, corresponding to a medium effect size (d=.59).

The mean CDRS score at pre-treatment was 39.08 with SD of 5.76, while at post-treatment it was 34.08 with SD of 8.59. The mean percent change in CDRS was 11.5%, SD=24%, corresponding to a medium effect size: Cohen’s d=.56.

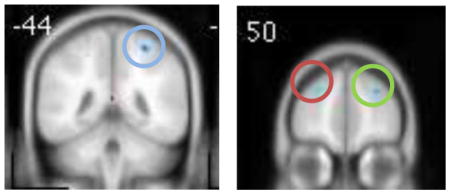

Whole brain comparison of HRforBD group and HC group at baseline

Clusters of activation that were significantly greater in the HRforBD group compared to the HC group at baseline are listed in Table 2. Consistent with previous studies in pediatric BD, the HRforBD group had less activation in the DLPFC compared to the HC group. They showed greater activation in the posterior cingulate/precuneus and middle occipital gyrus compared to the HC group.

Table 2.

Significant differences between High Risk for Bipolar Disorder (HRforBD) versus Healthy Control (HC) groups at baseline. All clusters passed a threshold of p=.005, k=20, corrected for multiple comparisons at the cluster level.

HC > HRforBD

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | BA | Cluster size | Peak Z | Tal x, y, z | |

| R fusiform | 37/20 | 75 | 3.48 | 54 −38 −25 | |

| L brainstem L parahippocampal gyrus |

N/A | 69 | 3.29 | −12 −14 −21 | |

| R superior frontal gyrus (DLPFC) |

|

9 | 33 | 3.42 | 28 48 35 |

| L superior frontal gyrus (DLPFC) |

|

9 | 41 | 3.16 | −22 54 37 |

| L postcentral | 3 | 28 | 3.19 | −22 −38 66 | |

| R precentral | 6 | 30 | 3.29 | 34 −18 65 | |

| R postcentral R superior parietal |

|

5 7 |

61 | 3.61 | 30 −44 68 |

| L postcentral | 3/4 | 23 | 3.04 | −14 −32 72 | |

HRforBD > HC

| |||||

| L middle occipital | 18 | 28 | 3.55 | −54 −74 20 | |

| L posterior cingulate/precuneus |

|

31/30 | 148 | 4.21 | −4 −50 26 |

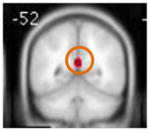

Changes in activation from pre- to post-treatment

Changes in activation from pre-treatment to post-treatment were hypothesized in 3 regions: the DLPFC, the VLPFC, and the amygdala. Results confirmed a significant change in the DLPFC, with activation greater at post-treatment compared to pre-treatment. The repeated measures t-test also identified a significant change in the amygdala, with activation greater at pre-treatment compared to post-treatment. Contrary to predictions, there were no significant changes in the VLPFC.

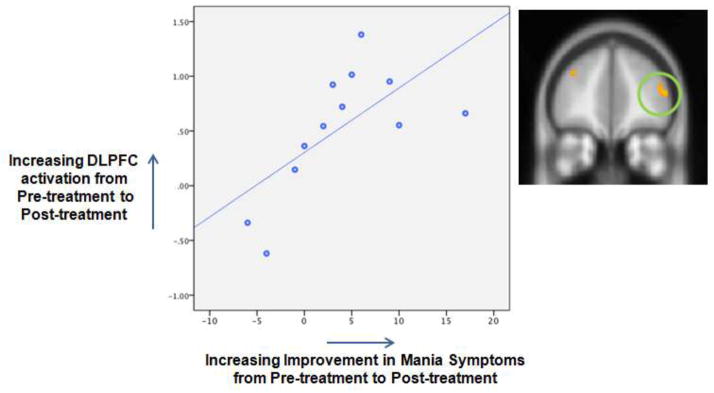

Correlations between change in activation and change in symptom severity

The change in DLPFC activation was significantly correlated with the change in YMRS scores (rho= − .72, p=.008; Figure 1) but not with change in CDRS score (rho= −.20, p=.53). Pre-treatment DLPFC activation did not predict change in YMRS after correction for multiple comparisons (rho= −.59, p=.04) nor did it predict change in CDRS (rho=-.11, p=.74). The threshold for significance, corrected for multiple comparisons, was p=.05/4 correlations = .0125.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot showing the significant correlation between increasing activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and improvement in symptoms of mania from pre to post treatment (Spearman’s rho= .72, p=.008).

Change in amygdala activation was not correlated with change in CDRS (rho=.11, p=.74) or change in YMRS (rho=.26, p=.42). Amygdala activation at pre-treatment did not predict change in CDRS (rho=.55, p=.06) or YMRS (rho=.04, p=.91).

Effects of Medication

In general, the effects of medications are controlled in repeated measures designs, as both the pre and post treatment scans are performed while medicated. For our study, six of the 12 subjects in the analysis were taking psychotropic medications at study entry (Table 1). For 5 subjects, medications were added during the treatment period. Therefore we re-computed correlations after removing data from these 5 subjects. The correlation between change in DLPFC and change in YMRS was reduced to a trend (rho= −.75, p=.052).

Discussion

In this study of the effects of psychotherapy on brain function among youth with symptoms of mood dysregulation and familial risk for BD, we found evidence that DLPFC activation increases while amygdala activation decreases from pre- to post treatment. Critically, the increase in DLPFC activation was correlated with a decrease in symptoms of mania, suggesting that this region might mediate clinical improvement.

The DLPFC is an executive control region that has a role in both cognitive control and emotion regulation (Frank et al. 2014; Kohn et al. 2014) so it makes sense that greater utilization of this resource would coincide with clinical improvement, as our data showed. Abnormalities in DLPFC function often have been reported in studies of pediatric patients with BD (K. Chang et al. 2004 ; Garrett et al. 2012; Ladouceur et al. 2011; Passarotti et al. 2010; Terry et al. 2009), and this abnormality was replicated in the current sample of youth at high risk for BD. Previous treatment studies of pediatric BD have reported that DLPFC activation decreases with pharmacological treatment, while our study found that DLPFC activation increases with psychotherapeutic treatment. Differences in the direction of fMRI findings could be attributed to differences in the task or contrast used in the analyses. Other differences are notable as well. In two of these studies, the decrease in DLPFC activation was not associated with symptom change (Pavuluri et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2013) and in the third, it was correlated with decreased symptoms of depression rather than mania (K. Chang et al. 2009).

In addition to changes in the DLPFC, the current study found that amygdala activation decreased from pre to post treatment. However this change was not correlated with symptom change so it is possible that it can be attributed to test-retest variability (Sauder et al. 2013). It is also possible that larger samples, or more severe mania symptoms, are needed to detect associations between amygdala activation and treatment outcome. Previous pharmacological treatment studies that reported amygdala activation as a predictor or a correlate of symptom improvement were based on samples of youth with BD rather than HRforBD (K. D. Chang et al. 2008; Passarotti et al. 2011; Pavuluri et al. 2011). The HRforBD group in our study did not appear to have amygdala hyperactivation compared to the HC group at baseline, unlike previous reports of youth with BD (Brotman et al. 2013; K. D. Chang et al. 2008; K. Chang et al. 2009; Frazier et al. 2005; Garrett et al. 2012; Rich et al. 2008; L. A. Thomas et al. 2013). It is possible that amygdala activation predicts outcomes from specific treatments but not all treatments. An exploratory test of this hypothesis showed that increasing amygdala activation at baseline significantly predicts increasing improvement in symptoms of depression, but only for the subset of patients who received FFT (p=.001). Our sample did not have abnormal VLPFC function or significant changes in the VLPFC following treatment, suggesting that VLPFC function remains stable for patients who do not have deficits at baseline.

Our sample includes youth with either depressive OR manic symptoms. The purpose of those criteria is to include all the symptoms that portend the eventual development of BD in youth at familial risk. In addition, previous studies have reported that pediatric samples are more likely to present with mixed symptoms than adult samples {Birmaher, 2009 #834}. However, it is possible that the mechanisms of symptom change could be different for participants in the manic versus depressive phase.

Limitations of our study include the small sample size, which significantly constrains the generalizability of our findings. Inconsistencies between our results and those from previous treatment studies might be due to small sample sizes. Larger studies will be important for confirming our findings. Our study is limited by the effects of medications, although medication tends to ‘normalize’ brain function rather than create spurious findings (Hafeman et al. 2012). Future studies should include a longitudinal healthy control group to investigate changes in brain activation associated with normal development and to assess test-retest reliability. To measure changes in symptoms not associated with therapy, a waitlist patient control group would be informative, but would present significant ethical and practical challenges. Without these control groups, we cannot definitively conclude that changes in brain function from pre to post treatment are attributed entirely to the therapies used in this study. However, we know that these brain changes are significantly correlated with concurrent symptom changes, which suggests that the DLPFC mediates symptom change. Again, more data is needed before we can say whether this is a mechanism specific to a particular treatment. Future studies with larger samples could investigate the possibility of using brain activation data as a biomarker of treatment response and for developing individualized interventions to stabilize mood symptoms.

Highlights.

Youth with mood dysregulation had fMRI scans before and after psychotherapy

At baseline, patients had hypoactivation in the DLPFC compared to healthy controls

After therapy, DLPFC activation increased while amygdala activation decreased.

Improvement in mania was correlated with increasing DLPFC activation.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support:

Supported by grants from NARSAD and NIMH R34 MH077856 (Miklowitz, Chang), and NIH P41-EB015891 (Glover)

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health: NIMH R34 MH077856 (Miklowitz, Chang), and NIH P41-EB015891 (Glover), and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Axelson DA, et al. Course of subthreshold bipolar disorder in youth: diagnostic progression from bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(10):1001–16. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, et al. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):795–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08101569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, et al. Fronto-limbic-striatal dysfunction in pediatric and adult patients with bipolar disorder: impact of face emotion and attentional demands. Psychol Med. 2013:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S003329171300202X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, et al. AACAP 2006 Research Forum--Advancing research in early-onset bipolar disorder: barriers and suggestions. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):3–12. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K, et al. Anomalous prefrontal-subcortical activation in familial pediatric bipolar disorder: a functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):781–92. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K, et al. Effect of divalproex on brain morphometry, chemistry, and function in youth at high-risk for bipolar disorder: a pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):51–9. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KD, et al. A preliminary functional magnetic resonance imaging study of prefrontal-amygdalar activation changes in adolescents with bipolar depression treated with lamotrigine. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(3):426–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Felder JN, Smoski MJ. The effects of Brief Behavioral Activation Therapy for Depression on cognitive control in affective contexts: An fMRI investigation. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(1–2):236–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diler RS, et al. Neural correlates of treatment response in depressed bipolar adolescents during emotion processing. Brain Imaging Behav. 2013;7(2):227–35. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DW, et al. Emotion regulation: Quantitative meta-analysis of functional activation and deactivation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;45C:202–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier JA, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in early-onset bipolar disorder: a critical review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):125–40. doi: 10.1080/10673220591003597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett AS, et al. Abnormal amygdala and prefrontal cortex activation to facial expressions in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(8):821–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, et al. Reliability of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) mania and rapid cycling sections. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):450–5. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller BG, et al. WASH-U-KSADS (Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia) St. Louis (Missouri): Washington University; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover GH, Law CS. Spiral-in/out BOLD fMRI for increased SNR and reduced susceptibility artifacts. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46(3):515–22. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeman DM, et al. Effects of medication on neuroimaging findings in bipolar disorder: an updated review. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(4):375–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn N, et al. Neural network of cognitive emotion regulation--an ALE meta-analysis and MACM analysis. Neuroimage. 2014;87:345–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur CD, et al. Differential patterns of abnormal activity and connectivity in the amygdala-prefrontal circuitry in bipolar-I and bipolar-NOS youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(12):1275–89. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD, Cunningham WA. Type I and Type II error concerns in fMRI research: re-balancing the scale. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2009;4(4):423–8. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Navsaria N. Pediatric bipolar disorder: evidence for prodromal states and early markers. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):459–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes TL, et al. Psychometric properties of the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised in adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(6):513–6. doi: 10.1089/cap.2010.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, et al. Early psychosocial intervention for youth at risk for bipolar I or II disorder: a one-year treatment development trial. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13(1):67–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsavsky AK, et al. Amygdala hyperactivation during face emotion processing in unaffected youth at risk for bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(3):294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarotti AM, Sweeney JA, Pavuluri MN. Differential engagement of cognitive and affective neural systems in pediatric bipolar disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(1):106–17. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709991019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarotti AM, Sweeney JA, Pavuluri MN. Fronto-limbic dysfunction in mania pre-treatment and persistent amygdala over-activity post-treatment in pediatric bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216(4):485–99. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri MN, et al. A pharmacological functional magnetic resonance imaging study probing the interface of cognitive and emotional brain systems in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(5):395–406. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri MN, et al. Double-blind randomized trial of risperidone versus divalproex in pediatric bipolar disorder: fMRI outcomes. Psychiatry Res. 2011;193(1):28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, et al. Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(9):875–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological-Corporation. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) [online text] Harcourt Brace & Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rich BA, et al. Neural connectivity in children with bipolar disorder: impairment in the face emotion processing circuit. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich BA, et al. Limbic hyperactivation during processing of neutral facial expressions in children with bipolar disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(23):8900–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603246103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauder CL, et al. Test-retest reliability of amygdala response to emotional faces. Psychophysiology. 2013;50(11):1147–56. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry J, Lopez-Larson M, Frazier JA. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in early onset bipolar disorder: an updated review. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(2):421–39. ix–x. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KM, et al. Amygdala response to facial expressions in children and adults. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(4):309–16. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LA, et al. Elevated amygdala responses to emotional faces in youths with chronic irritability or bipolar disorder. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;2:637–45. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vul E, Pashler H. Voodoo and circularity errors. Neuroimage. 2012;62(2):945–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, et al. Time course of recovery showing initial prefrontal cortex changes at 16 weeks, extending to subcortical changes by 3 years in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(2):571–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, et al. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]