Abstract

Successful ecdysis in insects depends on proper timing and sequential activation of an elaborate series of motor programs driven by a relatively conserved network of neuropeptides. The behaviors must be activated at the appropriate times to ensure successful loosening and shedding of the old cuticle, and can be influenced by environmental cues in the form of immediate sensory feedback and by circadian rhythms. We assessed the behaviors, components of the neural network and the circadian basis of ecdysis in the stick insect, Carausius morosus. C. morosus showed many of the characteristic pre-ecdysis and ecdysis behaviors previously described in crickets and locusts. Ecdysis was described in three phases, namely the (i) preparatory or pre-ecdysis phase, (ii) the ecdysial phase, and (iii) the post-ecdysis or exuvial phase. The frequencies of pushups and sways during the preparatory phase were quantified as well as durations of all the phases. The regulation of ecdysis appeared to act via elevation of cGMP, as described in many other insects, although eclosion hormone-like immunoreactivity was not noted using a lepidopteran antiserum. Finally, C. morosus showed a circadian rhythm to the onset of ecdysis, with ecdysis occurring just prior or at lights on. Ecdysis could be induced precociously with mechanical stimulation.

Keywords: ecdysis, eclosion hormone, cGMP, circadian rhythm, mechanical stimulation

1. Introduction

Successful removal of the exoskeleton, or ecdysis, in insects depends on the coordination of a series of elaborate and often stereotyped behaviors that must be activated at the appropriate times to ensure successful loosening and shedding of the old cuticle. Proper timing and sequential activation of the appropriate motor programs is initiated and modulated by neural networks, and can be influenced by circadian rhythms or more proximately, by environmental cues in the form of immediate sensory feedback to the various central pattern generators driving the ecdysis sequence. Thus, onset of ecdysis can be timed to the appropriate time of day or to times that allow the insect to avoid immediate threats from potential predators. The ecdysis sequence has been described in detail in locusts and crickets (Bernays, 1972; Carlson, 1977a & b; Carlson and Bentley, 1977; Truman et al., 1996) and in some additional holometabolous insects (e.g. mosquitos (Dai and Adams, 2009); honeybees and beetles (Roller et al., 2010); moths (Truman, 1971b; Truman, 1972; Park et al., 2002; Zitnan et al., 2007); flies (Park et al., 1999). Descriptions of the ecdysis sequence in these insects are included in the recent review (Zitnan and Adams, 2012).

The quantification of many of the behaviors (eg. Weeks and Truman, 1984a, b; Novicki and Weeks, 1993; Shimoide et al., 2013) along with the identification of key regulators (e.g. Horodyski et al., 1989; Zitnan et al., 1996; Ewer et al., 1994) has led to the generation of a model of the neural network regulating ecdysis.

The elaborate behaviors that contribute to pre-ecdysis (loosening of the old cuticle) and ecdysis (shedding of the cuticle) are regulated by a network of neuropeptides interacting to activate, modulate or inhibit muscle contractions and stereospecific abdominal waves required for successful shedding of the cuticle. Many of the hormones and neuropeptides involved in this regulation, such as eclosion hormone (EH), ecdysis triggering hormone (ETH), and crustacean cardioactive peptide (CCAP), as well as their second messengers, cGMP, cAMP and Ca+2, are suggested to be conserved across insect species (Truman, 1981; Truman and Copenhaver, 1989; Horodyski et al., 1989; Zitnan et al., 1996; Ewer and Truman, 1996; Gammie & Truman, 1999; Park et al., 1999; Fuse and Truman, 2002; Clark et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2006a, b; Asuncion-Uchi et al., 2010).

The circadian regulation of ecdysis and eclosion behaviors has been described for many holometabolous insects including a number of Drosophila species (eg. Honegger, 1967; Clayton and Paietta, 1972), other dipterans (Disney, 1969), and a number of leptidopterans such as Antheraea pernyi (Truman, 1971a) and Manduca sexta (Truman, 1972) (Reviewed by Lazzari and Insausti, 2008). Far fewer hemimetabolous or ametabolous insects than holometabolous insects have been shown to have a circadian rhythm associated with the onset of ecdysis. To our knowledge, such a rhythm has only been demonstrated in the kissing bug, Rhodnius prolixus (Ampleford and Steel, 1982), the springtail, Folsomia candida (Cutkompe et al., 1987) and some grasshopper species (Chen et al., 2009). Due to the conservation of much of the neural network that activates these behaviors, we suggest that the circadian regulation of ecdysis should also be conserved across many hemimetabolous species. The aim of this paper, therefore, was to describe ecdysis behaviors in detail, in a hemimetabolous insect, namely the stick insect, Carausius morosus. This was approached through (i) a detailed description of the ecdysis behaviors, (ii) determination of conserved features of the ecdysis neural network, and (iii) identification of a circadian influence to the onset of ecdysis.

2. Methods

2.1. Maintenance and isolation of Carausius morosus

A population of Carausius morosus was fed 2-3 times per week as needed, on pesticide-free cleaned green leaf lettuce. Insects were grouped in large colony cages, which were maintained next to a window to provide ambient light conditions for a natural photoperiod. The cages had wire perches spread throughout. The perches were layered with lettuce to cover the majority of light from above, while leaving room for insects to wander below, and to perch.

Freshly hatched C. morosus were pulled randomly from 4 different colony cages and maintained in a separate cage to monitor their growth. Their lengths were measured at each molt and plotted (Fig. 1), revealing the increase in body length at each stage. Thus, the stage of insects for subsequent experiments was determined by the body length upon removal from the colony.

Figure 1.

The average body length of C. morosus at each nymphal stage, immediately after ecdysis. Lengths of stick insects were measured after each ecdysis event since hatching. An exponential increase was noted with a linear regression of 0.98. The majority of insects experienced 6 ecdysis events before reaching reproductive maturity, with only four insects reaching a 7th stage (data omited).

A population of stick insects was maintained under real day/night condition on a window sill. Once hatched, they were transferred to separate incubators used for recording ecdysis events. Each insect was marked with white-out on the last dorsal abdominal segment, and housed individually in a glass jar within the incubator. The jar contained a mesh perch site and a 3-inch size piece of cleaned lettuce, provided for ad libitum feeding. The insects were fed 2-3 times per week at random times during the day as needed. Random feeding occurred at distant times relative to the onset of ecdysis, with minimal physical handling of the insects, in order to prevent mechanical stimulation during critical ecdysis periods. The temperature was maintained at 26°C in a light-controlled environment, unless described otherwise. Insects in jars were sprayed with room temperature water to humidify their environment as needed.

2.2. Videography and ecdysis behaviors

Stick insect pre-ecdysis and ecdysis behaviors were monitored and observed under both light and dark conditions at various developmental stages. This was done by eye and through videographic analysis. Samsung SMX-C10GN Digital CCD and JVC Everio Digital CCD camcorders were used to record data in the incubator in a hands-free setup. Specifically, common stereotypic behaviors, including patterns of contractions, locomotory and grooming activities, adoption of a characteristic posture, and peristaltic abdominal waves were monitored. Frequencies of specific motor programs and behaviors were assessed from video footage. Frequencies were determined by counting the number of behaviors for 30-60 sec clips from the video footage. Video footage was analyzed using a Windows Vista Dell computer with Windows Media Player 2011.

Since insects ate their cuticle after ecdysis, the loss of the white-out mark provided the preliminary cue for assessing ecdysis onset times. Footage around this time point was then monitored for the commencement of ecdysis, and this time was recorded.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

C. morosus was anesthetized on ice for 15 minutes prior to dissection of the central nervous system (CNS) in cold modified Weever’s saline solution (Weever, 1966). The nerve cords were then transferred and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hr at room temperature. Immunohistochemistry was performed using the method of Fuse and Truman (2002). In brief, tissues were washed in PBS-TX after fixation and after incubation in collagenase, then incubated in primary antibody for 48 hrs (Sheep-anti-cGMP diluted 1:10,000 in PBS-TX, a generous gift of Dr. Jan De Vente; rabbit-anti-EH diluted 1:250, a generous gift of Dr. Michael Adams). They were then washed again and incubated in appropriate secondary antisera conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (peroxidase goat-anti-sheep IgG for anti-cGMP and peroxidase goat-anti-rabbit IgG for anti-EH; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA; 1:1000 dilutions) for color reaction with diaminobenzedene. Tissues were washed again and mounted on poly-L lysine coated slides in DPX after tissue dehydration in an ethanol and xylenes series. Tissues were visualized on a Nikon Eclipse E600 Light microscope.

2.4. Light:Dark Regime

Within the incubator a number of light:dark (L:D) regimes were established at different times; 17L:7D (“long day”), 12L:12D, 7L:17D (“short day”), and 0L:24D (“all dark”). In the dark (subjective night), a 7.5 watt black light bulb was used to collect data videographically. In the light (subjective day), a 40 watt fluorescent bulb was used. Data were collected over several months with primary recordings occurring just before, during, and after the transition from dark to light.

In one experiment, the first 2-3 molts of nymphal insects were recorded under a long day (17L:7D). The next 2-3 molts of the same population of stick insects were recorded with the shortened day (7L:17D). A separate group of nymphs was raised in an all-dark environment after hatching, and monitored for the onset of the first three ecdyses.

2.5. Statistics

Analyses of variance and t-tests were performed using SigmaStat 3.1, with appropriate post-hoc tests noted within the results section.

3. Results

3.1. Organization of ecdysis behaviors

Stick insects generally went through 6 molts before becoming reproductively mature (Fig. 1). On occasion, a stick insect completed a 7th ecdysis event, but this was infrequent, and no subsequent molts were ever noted. The period of time between each molt varied from 6 to 26 days, with an average of 14.6 ± 2.8 days to molt. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA using ecdysis stage and day length as independent variables showed a main effect of day length and ecdysis stage on the number of days between successive ecdysis events (duration of intermolt). That is, the intermolt duration was significantly longer in the all-dark condition than in any other photoperiod (Fig. 2; P<0.05). Moreover, while there was no significant difference in intermolt duration between E4, E5 and E6, E3 was significantly shorter than both E4 and E6 (p<0.05). There was no interaction between photoperiod and stage of ecdysis on the intermolt duration.

Figure 2.

The average duration between molts (days) ± sem for each given sample size noted on the respective histogram bar. Timing started at E3 (molting from L2 to L3), and continued until E6. On occasion nymphs molted a 7th time, but this was rare and the sample size was very low.

Many classic ecdysis behaviors previously described in crickets (Carlson, 1977a) were observed in the stick insect, such as finding a perch, push-ups, and peristaltic abdominal waves. These were observed in all stages. The ecdysis behaviors in the stick insect that were required to shed the old cuticle were broken down into three distinct events: 1) A preparatory or pre-ecdysis phase (~2h) for loosening the old cuticle, 2) An ecdysial phase (~1h) when the cuticle was shed, and 3) a post-ecdysis or exuvial phase (~30 min) to allow for the hardening of the cuticle (Table 1).

Table 1.

Timing of ecdysis behaviors in the stick insect, C. morosus. Values represent average duration (min) of each motor program ± sem for each given sample size (n).

| Ecdysis Motor Program | Mean Total Duration (min) |

|---|---|

| Preparatory Phase | 156 ± 5.0 (47) |

| Ecdysis Phase | 52 ± 1.6 (47) |

| Exuvial Phase | 29 ± 2.0 (24) |

3.1.1. Preparatory pre-ecdysis phase

In preparation for ecdysis, stick insects stopped eating and displayed a series of stereotypic contractions and motor programs to help loosen the old cuticle so it could be successfully shed. These included “pushups” (Fig. 3a and Table 2), where the stick insect anchored itself firmly onto a solid surface and began a series of bilaterally symmetrical movements by first extending the coxa-trochanter, trochanter-femur and femur-tibia joints to raise the body, then flexing them, to lower the body. This resulted in an upward and downward bouncing movement of the body. The frequency of the behaviors was not significantly different from stage to stage (p>0.05). This was followed by a short period of immobility, before another bout of loosening behaviors occurred. The latter behaviors consisted of rocking back and forth or swaying movements (“sways”; Fig. 3b). Swaying consisted of asymmetrical extensions and flexions of the fore, abdominal, and hind legs, to push the insect to the left or right and these sways had a consistent frequency (Table 2). To sway to the left, as noted by the curved arrow (Fig. 3b), the left legs flexed while the right abdominal and hind legs fully extended and the foreleg remained in its fully extended position. A right sway was a mirror image of the left sway (diagram not shown). Swaying behaviors occurred more frequently than pushups and in a randomized and sporadic manner, and again had frequencies that were not significantly different from stage to stage (p>0.05). These behaviors were followed by some stretching and side-to-side motions. In between sways, a stationary median position allowed the insect to stay attached to the perch with slight flexions of the abdominal and hind legs, and full extension of the forelegs.

Figure 3.

Two behaviors from the stick insect “Preparatory (pre-ecdysis) phase”, which included “pushups” (A) and “sways” (B). (A) Up and down motions, noted by arrows, are due to bilaterally symmetrical leg extensions (up) and flexions (down) of the coxae-trochanter (ct), the trochanter-femur (tf) and the femur-tibia joints (ft). Extensions and flexions resulted in up and down bouncing movements of the body. Dashed lines represent the original position of the leg. (B) The left diagram shows the stationary median position when the insect stayed attached to its perch in between sways. The right diagram denotes the swaying mechanism for a left sway, denoted by the arrow. The swaying motion was due to fore, abdominal, and hind leg flexions and/or extensions. The dashed lines denote original positions of the legs in the perch position (see left diagram) prior to a left sway: generally, the left legs flexed and the right legs extended. Swaying to the right was a mirror image of the left sway (not shown).

Table 2.

Frequency of two stereotyped “Preparatory Phase” motor programs (push-ups and sways) in the stick insect, C. morosus. Values represent average frequencies of movements (Hz) of each motor program ± sem for each given sample size (n).

| Preparatory Phase | Frequency (Hz) |

|---|---|

| Push-ups | 0.80 ± 0.07 (18) |

| Sways | 1.81 ± 0.06 |

Pre-ecdysis behaviors lasted for an average of 2.6 hrs, and were followed by a period of restlessness and wandering locomotory movements, presumably to search for an appropriate perch site before ecdysis was attempted. The insect generally hung from its hind legs in preparation for ecdysis (Fig. 4a). The cuticle became soft and very thin, and the organism appeared plump and distended, instead of its usual lean, rigid appearance. The intersegmental membranes and abdominal segments were less obvious. Following ecdysis, the insect appeared thinner, with lighter coloration compared to the usual brownish-green.

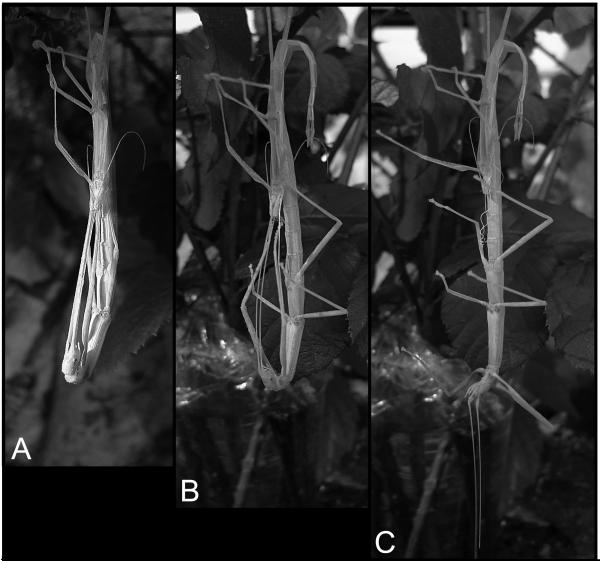

Figure 4.

Stick insect ecdysis. (A) During ecdysis, C. morosus began a series of stereotyped swaying motions while its head remained tucked forward with front legs caught in the old cuticle. (B) Immediately after the front legs and antennae were extricated from the old cuticle, the thorax remained bent. The middle and hind legs were not yet extracted from the old cuticle. (C) The remaining legs and posterior end were extricated from the old cuticle via peristaltic abdominal waves.

3.1.2. Ecdysial phase

When perched, C. morosus moved its entire body in a to-and-fro swaying motion, which appeared as uncontrollably short, jerky movements. This rocking, and back and forth swaying movement appeared to increase hemolymph concentration to the head region, since the head appeared much larger than normal after the swaying period. This was the point where the cuticle ruptured. The old exoskeleton split longitudinally, starting at the cervical ampullae (the soft membranous region between the head and the prothorax), and continued down the ecdysial line. The insect began to emerge from the cuticle headfirst, so that the prothorax and head remained tucked forward, entrapped in the cuticle (Fig. 4a).

There was a brief quiescent period (~5 min), then an ecdysial phase commenced for almost an hour (Table 1). With the antennae and front pair of legs still trapped in the old cuticle, the mesothorax remained curved (Fig. 4b). A second phase of abdominal peristaltic waves helped extricate the insect’s head and thorax from the old exoskeleton and helped move the old cuticle posteriorly until it was completely shed (Fig. 4c). These waves were more random, and no identifiable stereotyped behavior was noted by eye.

3.1.3. Post Ecdysis Phase (Exuvial Phase)

After fully extricating itself from its old cuticle, the stick insect entered a quiescent phase described as the post-ecdysis or exuvial phase. The insect remained immobile, hanging with its abdomen facing upwards, as its new cuticle hardened. During this time, the body appeared to enlarge, possibly due to hemolymph pumping to expand the new body and cuticle after successful ecdysis (Ziegler et al., 2000). As soon as the cuticle was hard enough, the stick insect flipped around to an upright position and began eating the old shed cuticle. The consumption of the cuticle was often discontinued if the stick insect was disturbed, and could be seen on the bottom of the housing. The post-ecdysis phase lasted almost 30 minutes, with the complete process of ecdysis taking almost 4 hrs (Table 1).

3.2. Immunohistochemical analysis during ecdysis

To determine whether increases in cGMP occurred during ecdysis, as has been described in M. sexta and D. melanogaster (Ewer and Truman, 1996; Baker et al., 1999), immunohistochemical staining was performed before and during ecdysis, using a cGMP-specific antibody (Fig. 5). It was assumed that cGMP immunoreactivity would be lacking during the intermolt stage, but would become apparent at ecdysis. As expected, clear cGMP immunoreactivity was noted in all thoracic and abdominal ganglia of C. morosus during ecdysis, in what appeared to be the homologous CCAP-containing neurons described previously in M. sexta (Fig. 5b and d). Staining was apparent in paired lateral neurosecretory cells and interneurons and their projecting axons within the thoracic (pro, meso and metathoracic) and abdominal ganglia. In abdominal ganglia, however, staining of interneurons was typically faint, and not noted consistently in all ganglia. Cyclic GMP immunoreactivity was not observed during the intermolt period, in either thoracic or abdominal ganglia (Fig. 5a and c).

Figure 5.

Cyclic GMP immunoreactivity in the ventral nerve cord of C. morosus. (A) Metathoracic ganglion during the intermolt period. Dashed lines denote areas of expected immunoreactive cells. (B) Cyclic GMP immunoreactivity in lateral neurosecretory cells (thick arrows), interneurons (thin arrows) and neurites (right arrowhead) and axon (left arrowhead) of the metathoracic ganglion during ecdysis. (C) Abdominal ganglion 3 during the intermolt period. Dashed lines denote areas of expected immunoreactive cells. (D) Cyclic GMP immunoreactivity in lateral neurosecretory cells and interneurons (asterisks) and axons (arrowheads) of abdominal ganglion 3 during ecdysis. Scale bar = 100 μm for all panels.

Ventral nerve cords of both intermolt and ecdysing C. morosus were also processed for EH-like immunoreactivity using an EH antiserum generated against M. sexta EH. No EH-like immunoreactivity was noted in either nymphs or adults, while staining was always apparent in M. sexta controls. This was true for a variety of dilutions of the anti-EH antiserum (data not shown).

3.3. Circadian regulation of Ecdysis

To determine whether there was a circadian rhythm regulating the onset of ecdysis in C. morosus, insects were maintained in various light:dark photoperiods, and timing of onset of ecdysis was monitored. Two photoperiods mimicking “long” and “short” days (17L:7D and 7L:17D light:dark cycles, respectively) and an all-dark photoperiod (0L:24D) were used.

3.3.1. Photoperiodic regulation of Ecdysis

A hands-free video recording system was established, and animals were monitored in a “long day” (17L:7D; Fig. 6a) and “short day” (7L:17D; Fig. 6b) environment. Ecdysis occurred around the time of lights-on in both long and short LD cycles. On average, insects ecdysed approximately 1.2 ± 0.4 hrs prior to normal lights on during a “long day” cycle (Table 3). While the shift to a “short day” resulted in a broader range of ecdysis times, with an average of just under 1 hour (0.9 ± 0.5 hrs) prior to lights on.

Figure 6.

Ecdysis profiles of C. morosus in short and long day photoperiods. (A) The first 2-3 molts from 32 nymphs were monitored in a “long day” (17L:7D) light:dark photoperiod. (B) These insects were then transitioned to a “short day” (7L:17D) light:dark photoperiod and timing of the last two nymphal ecdyses were noted.

Table 3.

Time to initiate ecdysis behaviors, relative to lights on, in the stick insect, C. morosus. Values represent average time after lights on (hrs) ± sem for each given sample size (n).

| Photoperiod | Time to start ecdysis relative to lights on (hrs) |

|---|---|

| Short days (7L:17D) | 0.9 ± 0.7 (24) |

| Long days (17L:7D) | 1.2 ± 0.5 (32) |

| All dark (0L: 24L) | 24.0 ± 0.04 (15) |

A group of hatchlings was also placed in an all dark (0L:24D) environment immediately after hatching, and the times to begin each ecdysis were recorded (Fig. 7). The data indicated that most ecdyses occurred at approximately the same time of day as the previous ecdysis. Given this observation, the timing of each ecdysis was determined relative to a 24 hr period from the previous molt. That is, calculations were based on how much the timing strayed from the 24 hr cycle relative to the previous molt (Fig. 8). For instance, if an insect ecdysed to the first nymphal stage at 4 pm and underwent its second ecdysis (days later) at 5 pm, there was a +1 hr shift in ecdysis time. If the second ecdysis occurred at 3 pm instead, there was a −1 hr shift. We assessed the difference in time, relative to a 24 hr period, of two subsequent ecdyses, from the 1st to 2nd ecdysis (E2; Fig. 8a) and the 2nd to 3rd ecdysis (E3; Fig. 8b). This allowed us to observe how subsequent ecdysis events deviated from a 24 hr circadian rhythm in the dark. As can be seen in Fig. 8, the majority of insects showed an ecdysis rhythm just slightly over 24 hr. Given the molt length of ~ 17 days in an all dark environment (Fig. 1), the ecdysis rhythm at any given period was determined per day. Thus from E1 to E2 there was an ecdysis period of 24.0 ± 3.6 hrs. From E2 to E3 there was an ecdysis period of 24.0 ± 2.4 hrs. While these periods were not significantly different (p>0.5), it should be noted that the period of the ecdysis rhythm in the dark appeared slightly more variable between E2 to E3, which would have been after approximately 51 days in the dark.

Figure 7.

Time of ecdysis, in real time, in an all-dark photoperiod. Hatchlings were placed in an all-dark environment (0L:24D) with temperature and humidity maintained as described in the methods. Three ecdysis events were recorded for 15 stick insects during this photoperiod. The 1st (E1), 2nd (E2) and 3rd (E3) ecdysis events are plotted for each insect at the time of occurance, with symbols noted in the legend.

Figure 8.

Ecdysis profiles of C. morosus in an all dark (0L:24D) photoperiod. Data are plotted as the difference in time from a 24 hour period from the previous molt. Time to ecdyse to (A) the second stage nymph (E2) relative to the first, and (B) the third stage nymph (E3) relative to E2.

3.3.2. Mechanical stimulation of ecdysis

To assess the effects of handling on ecdysis onset, insects were removed from a natural photoperiod at the fifth stage nymph, and then reared in 12L:12D conditions in individual containers, for the extent of the experiment. Nymphs were handled briefly every hour for 9 hrs. Handling consisted of tilting each insect jar, such that each insect moved briefly in response. Onset of ecdysis to the nearest hour was determined at each handling, by noting the commencement of ecdysis behaviors in marked animals, or by the lack of white-out in otherwise quiescent animals (often accompanied by the shed cuticle) (Fig. 9). When such an ecdysis event occurred, the hour was recorded. On the day of ecdysis, the majority of nymphs ecdysed with the first handling, whether insects were handled in the light portion (Fig. 9a) or the dark portion (Fig. 9b) of the light:dark cycle. That is, the majority of insects were observed commencing ecdysis upon handling, even when the light:dark cycle was alternated. These data suggested that mechanical stimulation affected the onset of ecdysis. The results were similar when insects were only handled two or three times (3-4 hour intervals), with the first handling inducing the largest proportion of ecdysis events (data not shown). This was also true for a variety of light:dark cycles ranging from 5L:19D to 19L:5D (data not shown). That is, mechanical stimulation appeared to over-ride any effects on light on initiating ecdysis.

Figure 9.

Effects of mechanical stimulation on ecdysis behaviors. Stick insects were reared in a 12L:12D photoperiod (light and dark period indicated by black bars on the x-axis). Animals were handled every hour, at times between the arrows. (A) Animals were checked during the lights on period. (B) Animals were checked during the lights off period.

4. Discussion

4.1. Ecdysis behaviors

The ecdysis sequence is accomplished through a series of elaborate behaviors that are necessary to ensure the loosening, and rapid and successful removal of the old exoskeleton prior to hardening of the newly exposed cuticle. These behaviors appear similar to stereotypic motor programs that have been carefully described and quantified in a number of holometabolous insects (e.g. Truman, 1972; Bainbridge and Bownes, 1981; Novicki and Weeks, 1993; Gammie and Truman, 1999; Baker et al., 1999; Zitnan and Adams, 2000; Zitnan et al., 2002; Park et al., 2002; Clark et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2006a, b; Dai and Adams, 2009; Roller et al., 2010; reviewed by Zitnan and Adams, 2012) along with a number of hemimetabolous insects (eg. Bernays, 1972; Carlson, 1977a & b; Hughes, 1980a-d; Truman et al., 1996). In C. morosus we have described three phases that produce the required behaviors to ensure successful shedding of the old cuticle.

(i) The preparatory or pre-ecdysis phase ensures that the old cuticle is sufficiently loosened and that the animal is suitably situated for extraction of the cuticle. Thus, stereotyped behaviors, some of which we have now quantified, help loosen and split the cuticle at the anterior end. These behaviors include leg and abdominal contractions and possible air-swallowing, as noted by the plump appearance of the body, to induce the ecdysial split. Air-swallowing has been described in a number of insect ecdyses (eg. Reynolds, 1980; Zdarek et al., 1984; Miles and Booker, 1998; Zilberstein et al., 2006), and swallowing appears to be a conserved feature since other arthropods such as the crustaceans swallow water to aid in splitting the old exoskeleton (Travis, 1954; de Fur et al., 1985; Chung et al., 1999). The preparatory period is completed by a period of wandering until the insect finds its perch, which allows it to hang by its hind legs in preparation for removal of the exuvia.

(ii) The ecdysiala variety of contractions, stereotyped rhythms were difficult to detect visually in phase is required to removal the old exoskeleton and while it also consists of C. morosus. Nevertheless, the motor programs ensured that the insect moved anteriorly through the ecdysial split, with anterior legs initially tucked into the old cuticle, as has been noted in the other hemimetabolous insects (Carlson, 1977a; Hughes 1980a). The lack of obvious stereotyped behaviors may have been due to interspersed random movements in response to proprioceptive feedback, or may have just been difficult to identify visually. Current computer-based data mining options may be the key to quantifying further behaviors (eg. Vaughan et al., 2005; Shimoide et al., 2013)

(iii) The post-ecdysis or exuvial phase has often been separated into unique periods, but is described as one phase for C. morosus. It consisted of the quiescent or immobile stage where the new cuticle inflated as it sclerotized, prior to the insect eating its exuvia. During the majority of this period, the anterior portion of the body appeared to enlarge, possibly due to air-swallowing or hemolymph pumping to expand the new body and cuticle after successful ecdysis (Reynolds, 1980; Ziegler et al., 2000; Zilberstein et al., 2006). Once the quiescent phase was over, the stick insect flipped around to an upright position and began eating the exuvia, apparently ending the full ecdysis repertoire.

Given the periodic nature of some of the behaviors we have described, we suggest that these behaviors may be driven by central pattern generators. Central pattern generators have already been described in C. morosus in the regulation of walking (Borgmann et al., 2009). The switch to ecdysis behaviors could be regulated by the same or related central pattern generators, whose inputs are currently not known.

4.2. Ecdysis neural network

Given the apparently conserved role of eclosion hormone (EH) in regulating ecdysis in insects (Truman et al., 1981), via cGMP (Ewer and Truman, 1996), we looked for the presence of EH-like immunoreactivity, and upregulation of cGMP during ecdysis, in the ventral nerve cord of C. morosus.

Surprisingly, EH-like immunoreactivity was not detected in C. morosus using the M. sexta antiserum during any stage or developmental period tested. We assessed a number of immature stages, as well as the adult stage in both intermolt and ecdysis phases, looking at the VNC and brain (data not shown). Thus either EH is not expressed in the Carausius nervous system or the antibody used does not detect Carausius EH. We believe that the antibody does not recognize Carausius EH, and suggest that a more specific antibody will need to be developed, once an amino acid or gene sequence is determined. It is odd, however, that EH-like immunoreactivity was not noted, given that numerous Manduca neuropeptides including EH, ETH, and CCAP have been applied to locust foreguts and yielded physiological responses, suggesting that other insect receptors recognize the Manduca peptide sequences (Zilberstein et al., 2006). In fact, CCAP sequence is identical between M. sexta and locusts (Stangier et al., 1989) and stick insects (Predel et al., 1999), although the sequences for ETH and EH remain unknown. ETH-like immunoreactivity was likewise detected in most insect orders studied, in a large comparative study using a single antiserum generated against M. sexta PETH (Zitnan et al., 1996; 2003). It will thus be useful to check for the presence of other ecdysis peptides in C. morosus in the future.

Truman et al. (1981) suggested that EH is a conserved hormone in many if not all insects, although we cannot exclude the possibility that neuropeptides such as EH are not conserved in all insects. Nevertheless, genes putatively producing EH or EH-like variants have been noted in many insects (e.g. Horodyski et al., 1989, 1993; Kamito et al., 1992) as well as other arthropods (e.g. ticks, Bissinger et al., 2011; Daphnia, Christie et al., 2011; spider mites, Veenstra et al., 2012). More importantly, a partial EH sequence has been found in a closely related orthopteran Romalea guttata (Zitnan et al., 2007), suggesting that a similar peptide is also present in the stick insect.

More interesting was the fact that, as with many other insects (Ewer and Truman, 1996), we noted increases in cGMP at ecdysis, but not during the intermolt. This was true in the thoracic and abdominal ganglia, in paired lateral neurosecretory cells and interneurons as well as axonal processes. Given the location of our stained cells by morphology, we suggest that the cGMP we observed likely originated from the homologous CCAP neurons that Ewer and Truman (1996) noted in a wide variety of holo- and hemimetabolous insects, including orthoptera (Ewer and Truman, 1996; Zilberstein et al., 2006) and the stick insect Baculum extradentatum (Lange and Patel, 2005). The CCAP expressing cells (commonly called Cells 27) have a unique morphology first described by Dircksen (1991; 1998). These CCAP neurons have been suggested to be the targets of EH action via cGMP during ecdysis (Gammie and Truman, 1999), and CCAP has been shown to regulate ecdysis in the hemimetabolous insect R. prolixus (Lee et al., 2013). Furthermore, CCAP has been identified in C. morosus by HPLC (Predel et al., 1999), and the CCAP immunoreactive neurons show a homologous morphology in all insects investigated so far and have been designated as Cells27/IN704 (Zitnan and Adams, 2012).

The staining pattern of cGMP in C. morosus was reminiscent of the staining pattern in numerous insects noted by Ewer and Truman (1996), in morphology and its upregulation at ecdysis. Co-localization studies and a time course of cGMP upregulation will need to be conducted in the future to verify that only neurosecretory cells are active, and that CCAP is present. The presence of cGMP during ecdysis, and absence during the intermolt in C. morosus, nevertheless suggests a cGMP-dependent initiation of the ecdysis motor program. Thus the neural network that regulates ecdysis in holometabolous insects may be conserved in hemimetabolous insects as well.

4.3. Circadian rhythms of ecdysis

4.3.1. Daily rhythm in C. morosus

As with numerous holometabolous insects and even some hemimetabolous and ametabolous insects, ecdysis appears to have a predictable circadian rhythmicity in C. morosus. This occurs with an almost 24 hr period, under all-dark conditions. The interval between successive molts is approximately 17 days and does not seem to vary systematically with the length of the photoperiod in which the animals are housed. This period is generally shorter (by 5-10 days) than previously described (Roth, 1917). This might be caused by rearing the insects at temperatures different from those used in previous experiments, which would significantly alter rates of growth. More interestingly, however, is the fact that while there are no differences in the duration of molts under different light:dark regimens, or even in an all-light environment, the interval between successive molts is significantly longer when insects are reared in the all dark environment. This has been shown in other insects as well, where the intermolt duration increases with age in an all-dark environment (Cutkomp et al., 1987).

The ecdysis profile of C. morosus under both long and short day photoperiods occurs in general just prior to lights ON. This is similar to that noted in D. pseudoobscura (Pittendrigh, 1954) and D. melanogaster (Paranjpe et al., 2005; Kumar et al., 2006). This makes sense given that both are nocturnal herbivores, and the quiesent post-ecdysis period can occur during the day, when insects are immobile in general. This is also early enough to ensure high humidity and cool temperatures for cuticular expansion and hardening, factors thought to be important favorable wing expansion in adult moths (Tanaka and Watari, 2009).

4.3.2. Mechanical stimulation

The temporal patterning of ecdysis typically follows a very predictable pattern, which includes a lengthy quiescent or inhibitory phase prior to the onset of the ecdysis phase that has also been described in other insects (Ewer et al., 1997; Zitnan and Adams, 2000; Fuse and Truman, 2002). The CNS at this period has been shown to be sensitive to various external stimuli, to allow onset of premature ecdysis when necessary, presumably to accommodate stresses in the environment or to allow synchronization with external cues. Given the relatively quiescent nature of the animals prior to actual ecdysis, the fairly immediate onset of ecdysis after mechanical stimulation may act as a form of defense, where the rhythmic motions may act as deterrents to predation. This is not surprising since many walking central pattern generators show both rhythmic and reflexive (to mechanical stimulation; Tomina et al., 2013) responses. Mechanical stimulation has been shown to induce premature eclosion in moths, even with no apparent adaptive value (Kammer and Kinnamon, 1977).

The response of C. morosus to stimulation during the quiescent phase of ecdysis is not unusual. For instance, D. melanogaster eclosion is synchronized to light, and can be manipulated with short light pulses at the appropriate time (Pittendrigh, 1954; McNabb and Truman, 1998). Body wall damage induces premature onset of larval ecdysis in M. sexta, as noted after surgical incisions, but only within the last half hour prior to normal onset of ecdysis (data not shown). Removal of cuticle from pharate pupae similarly initiates early onset of pupation (Kammer and Kinnamon, 1977). Application of CO2 at this critical time is another external cue that induces early onset of ecdysis, although the basis of this remains unknown (Fuse and Truman, 2002). In contrast, cuticle removal during ecdysis induces sustained ecdysis behaviors (Zitnan and Adams, 2000), indicating that sensory feedback has numerous effects on the ecdysis motor patterns. Nymphal eclosion of the elegant grasshopper, Zonocerus elegans, even correlates seasonally with the onset of rain (Kaufmann, 1972). Since the stick insects were housed individually, no effect of interactions between nymphs could be noted, which would be an interesting extra mechanical stimulus to examine in the future.

5. Conclusion

C. morosus, like many other insects, appears to show a circadian rhythm to the onset of ecdysis, and has an elaborate repertoire of motor programs to ensure the successful removal of the old exoskeleton in a timely manner. The neural network regulating onset or modulation of these behaviors needs to be studied further and may provide a strong hemimetabolous model for the regulation of ecdysis behaviors. It will be interesting to determine if some of the neuropeptides suggested to regulate the circadian clock in other hemimetabolous insects also work in C. morosus (eg. Söhler et al., 2007; Sohler et al., 2008).

Carausius morosus showed three phases of the ecdysis sequence: preparatory or pre-ecdysis, ecdysial, and post-ecdysis or exuvial.

Elevation of cGMP occurred in thoracic and abdominal ganglia only during ecdysis.

C. morosus showed a circadian rhythm to the onset of ecdysis, occurring at early dawn.

The circadian rhythm in the dark was approximately 24 hr.

Ecdysis could be induced precociously by mechanical stimulation.

Acknowledgements

Much of this work was submitted to SFSU in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters degree by Tracy Wadsworth and Andrew Carriman. We would like to thank Pablo Salinas for technical assistance on immunohistochemistry. Andrew Carriman and Alba Gutierrez were funded by the National Institute of Health-National Institute of General Medical Sciences Minority Access to Research Careers Fellowships [Grant number 5 T34-GM08574]. Megumi Fuse was funded by the National Institutes of Health-Minority Biomedical Research Support grant [grant number 2S06 GM52588-09], and by the SFSU center for Computing for Life Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ampleford S, Steel C. Circadian control of ecdysis. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1982;147:281–286. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asuncion-Uchi M, El Shawa H, Martin T, Fuse M. Different actions of ecdysis-triggering hormone on the brain and ventral nerve cord of the hornworm, Manduca sexta. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2010;166:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bainbridge SP, Bownes M. Staging the metamorphosis of Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology. 1981;66:57–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker JD, McNabb SL, Truman JW. The hormonal coordination of behavior and physiology at adult ecdysis in Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1999;202:3037–3048. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.21.3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernays EA. The intermediate moult (first ecdysis) of Schistocerca gregara (Forskal) (Insecta Orthoptera) Z. Morph. Tiere. 1972;71:160–179. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissinger BW, Donohue KV, Khalil SM, Grozinger CM, Sonenshine DE, Zhu J, Roe RM. Synganglion transcriptome and developmental global gene expression in adult females of the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae) Insect Molecular Biology. 2011;20(4):465–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2011.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borgmann A, Hooper A, Buschges A. Sensory feedback induced by front-leg stepping entrains the activity of central pattern generators in caudal segments of the stick insect walking system. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(9):2972–2983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3155-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson JR. The imaginal ecdysis of the cricket (Teleogryllus oceanicus). I Organization of motor programs and roles of central and sensory control. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1977a;115:299–317. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlson JR. The imaginal ecdysis of the cricket (Teleogryllus oceanicus). II The roles of identified motor units. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1977b;115:319–336. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson JR, Bentley D. Neural orchestration of a complex behavioral performance. Science. 1977;195(4282):1006–1008. doi: 10.1126/science.841322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen GP, Hao SG, Pang BP. Effect of photoperiod on the development, survival, eclosion and reproduction of 4th instar nymph of three grasshopper species in inner Mongolia. Chinese Bulletin of Entomology. 2009;46(1):51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christie AE, McCoole MD, Harmon SM, Baer KN, Lenz PH. Genomic analyses of the Daphnia pulex peptidome. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2011;171(2):131–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung JS, Dircksen H, Webster SG. A remarkable, precisely timed release of hyperglycemic hormone from endocrine cells in the gut is associated with ecdysis in the crab Carcinus maenas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1999;96(23):13103–13107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark A, Campo M, Ewer J. Neuroendocrine control of larval ecdysis behavior in Drosophila: Complex regulation by partially redundant neuropeptides. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(17):4283–4292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4938-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clayton DL, Paietta JV. Selection for circadian eclosion time in Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 1972;178(4064):994. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4064.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutkomp LK, Marques MD, Snider R, Cornélissen G, Wu JY, Halberg F. Chronobiologic view of molt and longevity of Folsomia candida (Collembola) at different ambient temperatures. Progress in Clinical Biological Research. 1987;227A:249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai L, Adams ME. Ecdysis triggering hormone signaling in the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2009;162(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Fur PL, Mangum CP, McMahon BR. Cardiovascular and ventilatory changes during ecdysis in the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathburn. Journal of Crustacean Biology. 1985;5(2):207–215. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dircksen H, Müller A, Keller K. Crustacean cardioactive peptide in the nervous system of the locust, Locusta migratoria: an immunocytochemical study on the ventral nerve cord and peripheral innervation. Cell Tissue Res. 1991;263(3):439–457. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dircksen H. Conserved crustacean cardioactive peptide (CCAP) neural networks and functions in arthropod evolution. In: Coast GM, Webster SG, editors. Recent Advances in Arthropod Endocrinology (Society for Experimental Biology Seminar Series. Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 302–333. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Disney RHL. Timing of adult eclosion in blackflies (dipt, simuliidae) in West Cameroon. Bulletin of Entomological Research. 1969;59:485. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewer J, Truman JW. Increases in cyclic 3′, 5′-guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) occur at ecdysis in an evolutionarily conserved crustacean cardioactive peptide-immunoreactive insect neuronal network. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1996;370:330–341. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960701)370:3<330::AID-CNE4>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ewer J, De Vente JD, Truman JW. Neuropeptide inductions of cyclic GMP increases in the insect CNS: Resolution at the level of single identifiable neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14(12):7704–7712. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07704.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewer J, Gammie SC, Truman JW. Control of insect ecdysis by a positive–feedback endocrine system: Roles of eclosion hormone and ecdysis triggering hormone. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1997;200:869–881. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuse M, Truman JW. Modulation of ecdysis in the moth Manduca sexta: the roles of the subesophageal and thoracic ganglia. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2002;205:1047–1058. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.8.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gammie SC, Truman JW. Eclosion hormone provides a link between ecdysis-triggering hormone and crustacean cardioactive peptide in the neuroendocrine cascade that controls ecdysis behavior. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1999;202(4):343–352. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honegger HW. Analysis of effect of light pulses on eclosion rhythm of Drosophila pseudoovscura. Zeitschrift Fur Vergleichende Physiologie. 1967;57(3):244. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horodyski FM, Riddiford LM, Truman JW. Isolation and expression of the eclosion hormone gene from the tobcacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1989;86:8123–8127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes TD. The imaginal ecdysis of the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria. I. A description of the behaviour. Physiological Entomology. 1980a;5:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes TD. The imaginal ecdysis of the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria. II. Motor activity underlying the pre-emergence and emergence behaviour. Physiological Entomology. 1980b;5:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes TD. The imaginal ecdysis of the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria. III. Motor activity underlying the expansional and post-expansional behaviour. Physiological Entomology. 1980c;5:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hughes TD. The imaginal ecdysis of the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria. IV. The role of the gut. Physiological Entomology. 1980d;5:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamito T, Tanaka H, Sato B, Nagasawa H, Suzuki A. Nucleotide sequence of cDNA for the eclosion hormone of the silkworm, Bombyx mori, and the expression in a brain. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1992;182(2):514–519. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91762-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kammer A, Kinnamon S. Patterned Muscle Activity during Eclosion in the Hawkmoth Manduca sexta. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1977;114:313–326. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaufmann T. Biology and feeding habits of Zonocerus elegans (Orthoptera: Acrididae) in Central Tanzania. American Midland Naturalist. 1972;87(1):165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim Y, Zitnan D, Cho K, Schooley DA, Mizoguchi A, Adams ME. Central peptidergic ensembles associated with organization of an innate behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2006a;103(38):14211–14216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603459103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim YJ, Zitnan D, Galizia CG, Cho KH, Adams ME. A command chemical triggers an innate behavior by sequential activation of multiple peptidergic ensembles. Current Biology. 2006b;16(14):1395–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar S, Vaze K, Kumar D, Sharma V. Selection for early and late adult emergence alters the rate of pre-adult development in Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Developmental Biology. 2006;6(57):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-6-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lange AB, Patel K. The presence and distribution of crustacean cardioactive peptide in the central and peripheral nervous system of the stick insect, Baculum extradentatum. Regulatory Peptides. 2005;129(1-3):191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lazzari C, Insausti T. Circadian rhythms in insects. Transworld Research Network-Comparative Aspects of Circadian Rhythms. 2008:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee D, Orchard I, Lange AB. Evidence for a conserved CCAP-signaling pathway controlling ecdysis in a hemimetabolous insect, Rhodnius prolixus. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2013;7:207. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNabb S, Truman JW. Light and peptidergic eclosion hormone neurons stimulate a rapid eclosion response that masks circadian emergence in Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2008;211:2263–2274. doi: 10.1242/jeb.015818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miles CI, Booker R. The role of the frontal ganglion in the feeding and eclosion behavior of the moth Manduca sexta. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1998;201(11):1785–1798. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.11.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Novicki A, Weeks JC. Organization of the larval pre-ecdysis motor pattern in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 1993;173:151–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00192974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paranjpe DA, Anitha D, Chandrashekaran MK, Joshi A, Sharma VK. Possible role of eclosion rhythm in mediating the effects of light-dark environments on pre-adult development in Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Developmental Biology. 2005;5(5):1186–1471. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park Y, Zitnan D, Gill S, Adams ME. Molecular cloning and biological activity of ecdysis-triggering hormones in Drosophila melanogaster. FEBS letters. 1999;463:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01622-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park Y, Filippov V, Gill SS, Adams ME. Deletion of the ecdysis-triggering hormone gene leads to lethal ecdysis deficiency. Development. 2002;129(2):493–503. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pittendrigh CS. On temperature independence in the clock system controlling emergence time in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1954;40:1018–1029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.40.10.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Predel R, Kellner R, Gade G. Myotropic neuropeptides from the retrocerebral complex of the stick insect, Carausius morosus (Phasmatodea: Lonchodidae) European Journal of Entomology. 1999;96:275–278. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reynolds SE. Integration of behaviour and physiology in ecdysis. Advances in Insect Physiology. 1980;15:475–595. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roller L, Zitnanová I, Dai L, Simo L, Park Y, Satake H, Tanaka Y, Adams ME, Zitnan D. Ecdysis triggering hormone signaling in arthropods. Peptides. 2010;31(3):429–441. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roth HL. XIX. Observations on the growth and habits of the stick insect, Carausius morosus, Br.; intended as a contribution towards a knowledge of variation in an organism which reproduces itself by the parthenogenetic method. Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London. 1917;64(3-4):345–386. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shibanaka Y, Hayashi H, Okada N, Fujita N. The crucial role of cyclic GMP in the eclosion hormone mediated signal transduction in the silkworm metamorphoses. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1991;180(2):881–886. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimoide A, Kimball I, Gutierrez AA, Lim H, Yoon I, Birmingham JT, Singh R, Fuse M. Quantification and analysis of ecdysis in the hornworm, Manduca sexta, using machine vision-based tracking. Invertebrate Neuroscience. 2013;13(1):45–55. doi: 10.1007/s10158-012-0142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Söhler S, Neupert S, Predel R, Nichols R, Stengl M. Localization of leucomyosuppressin in the brain and circadian clock of the cockroach Leucophaea maderae. Cell and Tissue Research. 2007;328(2):443–452. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Söhler S, Neupert S, Predel R, Stengl M. Examination of the role of FMRFamide-related peptides in the circadian clock of the cockroach Leucophaea maderae. Cell and Tissue Research. 2008;332(2):257–269. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0585-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stangier J, Hilbich C, Keller R. Occurrence of crustacean cardioactive peptide (CCAP) in the nervous system of an insect, Locusta migratoria. Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 1989;159:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tanaka K, Watari Y. Is early morning adult eclosion in insects an adaptation to the increased moisture at dawn? Biological Rhythms Research. 2009;40(4):293–298. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomina Y, Kibayashi A, Yoshii T, Takahata M. Chronic electromyographic analysis of circadian locomotor activity in crayfish. Behavioural Brain Research. 2013;15(249):90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Travis DF. The molting cycle of the spiny lobster, Panulirus argus Latreille. I. Molting and growth in laboratory maintained individuals. Biological Bulletin. 1954;107:433–450. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Truman JW. Hour-glass behavior of the circadian clock controlling eclosion of the silkmoth Antheraea pernyi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1971a;68(3):595–599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.3.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Truman JW. Physiology of insect ecdysis I. The eclosion behaviour of saturniid moths and its hormonal release. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1971b;54:805–814. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Truman JW. Physiology of Insect Rhythms I. Circadian Organization of the Endocrine Events Underlying the Moulting cycle of Larval Tobacco Hornworms. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1972;57(3):805–821. doi: 10.1242/jeb.60.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Truman JW. Interaction between ecdysteriod, eclosion hormone, and bursicon titers in Manduca sexta. American Zoologist. 1981;21:655–661. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Truman JW, Copenhaver PF. Larval eclosion hormone neurons on Manduca sexta: Identification of the brain-proctodeal neurosecretory system. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1989;147:457–470. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Truman JW, Ewer J, Ball EE. Dynamics of cyclic GMP levels in identified neurons during ecdysis behaviors in the locust, Locusta migratoria. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1996;199:749–758. doi: 10.1242/jeb.199.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Truman JW, Taghert PH, Copenhaver PF, Tublitz NJ, Schwartz LM. Eclosion hormone may control all ecdyses in insects. Nature. 1981;291:70–71. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vaughan A, Singh R, Shimoide A, Yoon I, Fuse M. Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computational Systems Bioinformatics Conference. IEEE Computer Society Press; 2005. EigenPhenotypes: Towards an algorithmic framework for phenotype discovery; pp. 77–78. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Veenstra JA, Rombauts S, Grbić M. In silico cloning of genes encoding neuropeptides, neurohormones and their putative G-protein coupled receptors in a spider mite. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2012;42(4):277–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weeks JC, Truman JW. Neural organization of peptide-activated ecdysis behaviors during the metamorphosis of Manduca sexta. I. Conservation of the peristalsis motor pattern at the larval-pupal transformation. Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 1984a;155:407–422. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weeks JC, Truman JW. Neural organization of peptide-activated ecdysis behaviors during the metamorphosis of Manduca sexta. II. Retention of the proleg motor pattern despite loss of the prolegs at pupation. Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 1984a;155:423–433. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weever RD. A lepidopteran saline: effects of inorganic cation concentrations on sensory, reflex and motor responses in a herbivorous insect. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1966;44:163–175. doi: 10.1242/jeb.44.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zdarek J, Zavadilova J, Su J, Fraenkel G. Posteclosion behavior of flies after emergence from the puparium. Acta Entomologica Bohemoslovaca. 1984;81:161. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ziegler A, Grospietsch T, Carefoot T, Danko J, Zimmer M, Zerbst-Boroffka I, Pennings S. Hemolymph ion composition and volume changes in the supralittoral isopod Ligia pallasii Brandt, during molt. Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 2000;170:329–336. doi: 10.1007/s003600000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zilberstein Y, Ewer J, Ayali A. Neuromodulation of the locust frontal ganglion during the moult: a novel role for insect ecdysis peptides. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2006;209:2911–2919. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zitnan D, Adams ME. Excitatory and inhibitory roles of central ganglia in initiation of the insect ecdysis behavioural sequence. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2000;203(8):1329–1340. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.8.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zitnan D, Adams ME. In: Neuroendocrine Regulation of Ecdysis, in Insect Endocrinology. Gilbert LI, editor. Academic Press; 2012. pp. 253–309. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zitnan D, Kingan TG, Hermesman JL, Adams ME. Identification of ecdysis-triggering hormone from an epitracheal endocrine system. Science. 1996;271(5245):88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5245.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zitnan D, Hollar L, Spalovská I, Takác P, Zitnanová I, Gill SS, Adams ME. Molecular cloning and function of ecdysis-triggering hormones in the silkworm Bombyx mori. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2002;205(22):3459–3473. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.22.3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zitnan D, Zitnanova I, Spalovska I, Takac P, Park Y, Adams ME. Conservation of ecdysis-triggering hormone signalling in insects. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2003;206:1275–1289. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zitnan D, Kim YJ, Zitnanová I, Roller L, Adams ME. Complex steroid-peptide-receptor cascade controls insect ecdysis. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2007;153(1-3):88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]