Abstract

Nur77, encoded by Nr4a1 (alias Nur77), plays roles in cell death, survival, and inflammation. To study the role of Nur77 in liver regeneration, wild-type (WT) and Nur77 knockout (KO) mice were subjected to standard two-thirds partial hepatectomy (PH). Nur77 mRNA and protein levels were markedly induced at 1 hour after PH in WT livers, coinciding with ERK1/2 activation. Surprisingly, Nur77 KO mice exhibited a higher liver-to-body weight ratio than WT mice at 24, 48, and 72 hours after PH. Nur77 KO livers exhibited increase in Ki-67–positive hepatocytes at 24 hours, with early induction of cell-cycle genes. Despite accelerated regeneration, Nur77 KO livers paradoxically incurred necrosis, hepatocyte apoptosis, elevated serum alanine aminotransferase activity, and Kupffer cell accumulation. Microarray analysis revealed up-regulation of genes modulating inflammation, cell proliferation, and apoptosis but down-regulation (due to Nur77 deficiency) of glucose and lipid homeostasis genes. Levels of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, and CCL2 were increased and levels of anti-inflammatory IL-10 were decreased, compared with WT. Activated NF-κB and STAT3 and mRNA levels of target genes Myc and Bcl2l1 were elevated in Nur77 KO livers. Overall, Nur77 appears essential for regulating early signaling of liver regeneration by modulating cytokine-mediated inflammatory, apoptotic, and energy mobilization processes. The accelerated liver regeneration observed in Nur77 KO mice is likely due to a compensatory effect caused by injury.

Liver regeneration is a well-orchestrated and tightly regulated process that proceeds through distinct stages with priming of hepatocytes, cell-cycle progression, proliferation, and termination of regeneration.1,2 Liver regeneration induced by partial hepatectomy (PH) involves multiple cell types interacting in coordination. Activated Kupffer cells (KCs) and hepatic stellate cells release a series of growth factors, including transforming growth factor β and hepatocyte growth factor, as well as proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) to drive the cell-cycle entry of quiescent hepatocytes.3,4 In response to PH, KC-secreted TNF-α activates downstream target nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), which then up-regulates the transcription of Ccnd1.5,6 Meanwhile, IL-6–mediated activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) also promotes hepatocyte proliferation after PH.1,7 These findings suggest that the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α and their downstream transcriptional regulators NF-κB and STAT3 are necessary for the priming and progression of liver regeneration.1,8,9 Furthermore, PH-induced liver regeneration is typically an injury-free process, with regeneration resulting from interactions between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators to amplify the proliferative response elicited by growth factors.10–12

Orphan nuclear receptor Nur77, a member of the nuclear receptor subfamily 4 (NR4A) encoded by Nr4a1 (alias Nur77), is an early immediate-response gene whose expression can be induced by diverse stimuli.13,14 Together with Nurr1 (Nr4a2) and Nor1 (Nr4a3), Nur77 functions as a key transcriptional regulator of cell apoptosis, proliferation, inflammation, and energy metabolism.15–17 NR4A receptors are highly conserved, with 97% homology in their DNA-binding domains, 60% to 65% homology in the C-terminal ligand-binding domains, and 20% to 30% homology in their N-terminal transactivation domains.18 Despite several common activities and high sequence similarity, each NR4A member exhibits divergent functions. Nurr1 is involved in the initiation and maintenance of midbrain dopamine neurons, and Nor1 regulates embryonic, inner ear, and hippocampus development.19 Distinct from its two subfamily members, Nur77 can modulate cell proliferation and apoptosis in lymphocytes, neurons, and tumor cells.20,21 The opposing role of Nur77 in regulating cell survival and death is dependent on its intracellular location.14,22 Growth factors such as epidermal growth factor rapidly induce the expression of Nur77 in the nucleus, where it serves as an oncogene to enhance cell survival and growth.23 By contrast, apoptosis inducers increase cytosolic Nur77, which promotes cell death.24,25

The role of Nor1 in the modulation of hepatocyte proliferation has been investigated recently. Nor1 promotes hepatocyte proliferation in mice through up-regulation of its target gene, Ccnd1, independently of TNF-α and IL-6–mediated inflammatory pathway.26 Despite the well-known role in regulating cell proliferation, the effect of Nur77 in liver regeneration has not been studied previously. As an immediate and transient growth factor–induced gene, Nur77 is also a key mediator of the inflammatory response in macrophages.27 Moreover, Nur77 can also inhibit the expression of several proinflammatory genes by repressing the activity of NF-κB in vitro.28 In addition to the inflammatory response, Nur77 alters metabolism by modulating insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis via transcriptional regulation of genes involved in gluconeogenesis.17,29 Thus, Nur77 may be critical in modulating liver regeneration because of its regulatory effects on inflammatory signaling and energy metabolism.

In the present study, the PH-induced mouse liver regeneration model was used to study the role of Nur77 in regulating liver regeneration. Our findings indicate that regenerating Nur77 knockout (KO) mouse livers exhibit transient inflammatory response and liver injury after PH that is accompanied by accelerated compensatory liver regeneration. Gene profiling revealed differentially expressed genes involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis, innate immune response, and energy metabolism between regenerating wild-type (WT) and Nur77 KO mouse livers. Our findings indicate that Nur77 is essential for controlling the early events of liver regeneration by modulating inflammatory, apoptotic, and metabolic processes. The compensatory early induction of cell-cycle genes may result from increased NF-κB and STAT3 signaling, contributing to complete restoration of liver mass in Nur77 KO mice. Taken together, these findings suggest that Nur77 is crucial for suppressing hepatic inflammation and preventing necrotic injury in PH-induced liver regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Strains, Partial Hepatectomy, and Sample Preparation

C57BL/6 WT and Nur77 KO male mice30 from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), aged 3 to 5 months, were housed in steel microisolator cages at 22°C with a 12 hours/12 hours light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Standard two-thirds PH was performed as described previously,31 and sham surgery was performed for control mice. Surgery was performed between 9:00 and 11:00 AM, and mice were sacrificed at specified time points (3 to 8 mice per time point). Liver and body weight were recorded at the time of death for calculating liver-to-body weight ratios. Serum and liver tissues were collected and kept at −20°C and −80°C, respectively, until assayed. A section of each liver was fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained for histological analysis. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the current edition of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals32 under protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin for 12 to 16 hours and washed in 70% ethanol for 24 hours. Tissues were then embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm sections. Standard hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed. To identify Nur77 intracellular localization, immunostaining was performed with anti-Nur77 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). To monitor hepatocyte proliferation, immunostaining was performed with anti–Ki-67 antibody (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA). To assess KC activation, immunostaining with anti-F4/80 antibody (Abcam) was followed by labeling with biotinylated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). The number of proliferating hepatocytes or activated KCs was determined by counting positive-staining cells in at least five random microscopic fields (×20) for each specimen.

TUNEL Assay

To monitor hepatocyte apoptosis, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed with an in situ cell death detection kit with tetramethylrhodamine (TMR red) (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany; Indianapolis, IN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The number of red fluorescent-labeled nuclei was counted under fluorescence microscopy in at least five random microscopic fields (×40) for each specimen.

Serum Alanine Aminotransferase Assay

Serum was stored at −20°C and was used to assay alanine aminotransferase activities using a liquid alanine aminotransferase [ALT (SGPT)] reagent kit (Pointe Scientific, Brussels, Belgium).

RNA Isolation, Quantitative Real-Time PCR, and Microarray

RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies). cDNA was synthesized using a high-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Life Technologies). Real-time quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (RT-qPCR) was performed on an ABI 7900HT Fast real-time PCR system using Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Life Technologies). Primers were designed using Primer3 Input software version 0.4.0; sequences are available in Table 1. For quantification, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) mRNA level served as an internal control. Data generated from WT mice at time 0 were used to establish a baseline to calculate the relative expression levels between groups. The relative mRNA level at each time point was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCT method,33 where ΔΔCT = (CT,target − CT,Gapdh)Time t − (CT,target − CT,Gapdh)Time 0.

Table 1.

Primers used for RT-qPCR

| Target gene | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Nur77 | F: 5′-TGCCTTCCTGGAACTCTTCATC-3′ |

| R: 5′-AGTACCAGGCCTGAGCAGAAGAT-3′ | |

| Nurr1 | F: 5′-CCTCCAACTTGCAGAATATGAACA-3′ |

| R: 5′-CCGTGTCTCTCTGTGACCATAGC-3′ | |

| Nor1 | F: 5′-AAGTGTCTCAGTGTCGGGATGGTT-3′ |

| R: 5′-TCCTGTTGTAGTGGGCTCTTTGGT-3′ | |

| Ccnb1 | F: 5′-CCCCAAGTCTCACTATCA-3′ |

| R: 5′-CGAGGGAATGACTATGTT-3′ | |

| Cdk1 | F: 5′-TCCGGTTGACATCTGGAGTA-3′ |

| R: 5′-TCCACTTGGGAAAGGTGTTC-3′ | |

| Ccnd1 | F: 5′-CGTGGCCTCTAAGATGAAGGA-3′ |

| R: 5′-TCGGGCCGGATAGAGTTGT-3′ | |

| Cdk4 | F: 5′-GCCAGAGATGGAGGAAGTCTG-3′ |

| R: 5′-TTGTGCAGGTAGGAGTGCTG-3′ | |

| Ccne1 | F: 5′-GCAGCGAGCAGGAGACAGA-3′ |

| R: 5′-TGCTTCCACACCACTGTCTTTG-3′ | |

| Cdk2 | F: 5′-TCCCCTCATCAAGAGCTATCTGTT-3′ |

| R: 5′-TCTGCATTGATAAGCAGGTTCTG-3′ | |

| Casp8 | F: 5′-TGGAACCTGGTATATTCAGTCACTTT-3′ |

| R: 5′-CCAGTCAGGATGCTAAGAATGTCA-3′ | |

| Cd14 | F: 5′-GGTCGAACAAGCCCGTGGAACC-3′ |

| R: 5′-AGCACACGCTCCATGGTCGG-3′ | |

| Ccl2 | F: 5′-TGATCCCAATGAGTAGGCTGGAGA-3′ |

| R: 5′-ACCTCTCTCTTGAGCTTGGTGACA-3′ | |

| Il6 | F: 5′-GTTGCCTTCTTGGGACTGATG-3′ |

| R: 5′-GGGAGTGGTATCCTCTGTGAAGTCT-3′ | |

| Il12 | F: 5′-GGTGCAAAGAAACATGGACTTG-3′ |

| R: 5′-GGTGCAAAGAAACATGGACTTG-3′ | |

| Il23 | F: 5′-AGTGTGAAGATGGTTGTGACCCAC-3′ |

| R: 5′-GAAGATGTCAGAGTCAAGCAGGTG-3′ | |

| Il10 | F: 5′-GGAGCAGGTGAAGAGTGATTTTAATA-3′ |

| R: 5′-TGCAGTTGATGAAGATGTCAAATTC-3′ | |

| Mmp9 | F: 5′-CGACGTGGGCTACGTGACCTAC-3′ |

| R: 5′-AGCACCTTTCCCTCGGATGGG-3′ | |

| Mmp2 | F: 5′-ACACTGGGACCTGTCACTCC-3′ |

| R: 5′-TGTCACTGTCCGCCAAATAA-3′ | |

| Map3k14 | F: 5′-AGAAGACCGAGCCCTTTACTACCT-3′ |

| R: 5′-ACAGGAGCACGTTGTCAGCTTTGA-3′ | |

| Ikki | F: 5′-CCCAGGCCGTTTTGCAT-3′ |

| R: 5′-GTCACGTTGGTCTGCTCATATACAG-3′ | |

| Myc | F: 5′-AGTAATTCCAGCGAGAGGCA-3′ |

| R: 5′-AGCAGCTCGAATTTCTTCCA-3′ | |

| Bcl2l1 | F: 5′-TCATCCTCTTATGCTTCCGGGCAT-3′ |

| R: 5′-ACTCCCTCTCCTAGAACCAGTCTT-3′ |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Microarray and Pathway Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from WT and Nur77 KO mouse livers at 3 hours after PH. RNA quantity and quality were assessed with a Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Microarray and data analysis were performed as described previously.34 The GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) was used. All biological function and pathway analyses were generated by the Functional Annotation tool in the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID version 6.7) (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov). Functional pathways and processes with P < 0.05 and Bonferroni value <0.1 were accepted.

Western Blotting

Protein lysates obtained from liver homogenate (40 μg) were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions. Separated proteins from gels were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk and incubated with specific primary antibody against Nur77, cyclin E, CDK2, β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), ERK1/2, phosphorylated (p-) ERK1/2, STAT3, p-STAT3 (Tyr705), and p-NF-κB (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. The signals were detected using an ECL enhanced chemiluminescence system with Pierce SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Statistical Analysis

The differences between the two groups were analyzed with the Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are expressed as means ± SD.

Results

Early and Transient Induction of Nur77 during Liver Regeneration after PH

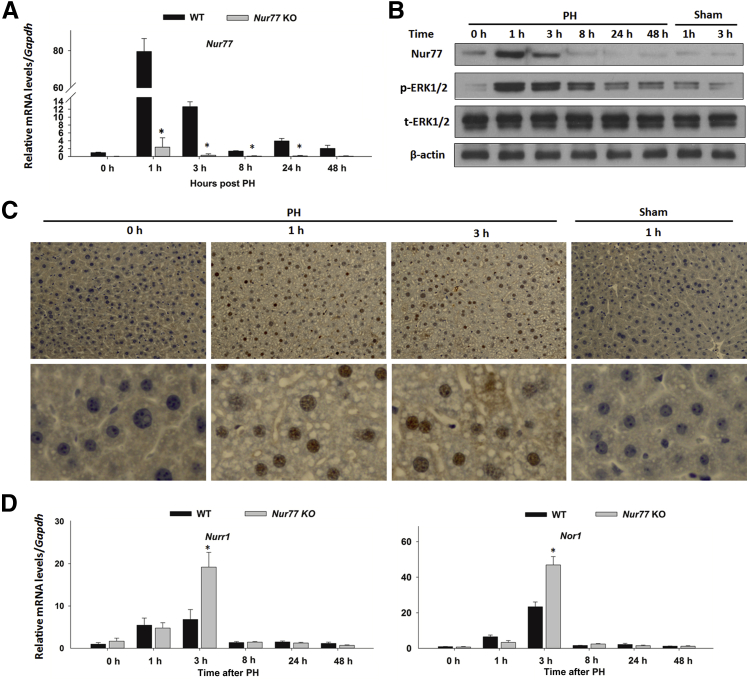

To study the role of Nur77 in hepatocyte proliferation, WT and Nur77 KO mice received two-thirds PH and were sacrificed at 1, 3, 8, 24, and 48 hours after surgery to determine Nur77 hepatic expression. In WT mice, Nur77 mRNA level was induced by 80-fold within 1 hour after PH and then dropped to basal level by 8 hours (Figure 1A). In accord, Nur77 protein level also showed a substantial induction at the same time point (Figure 1B). Additionally, Nur77 induction coincided with increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which peaked at 1 hour after PH. Because ERK1/2 activation is essential for the transcriptional effect of Nur77, PH-induced Nur77 could be a consequence of ERK1/2 activation.25,35 Immunohistochemistry staining revealed PH-induced Nur77 predominantly in the nuclei of hepatocytes, but not in KCs, stellate cells, or other nonparenchymal cells (Figure 1C). Localization of Nur77 in the hepatocyte nuclei suggests a role in gene regulation and cell proliferation. Nurr1 and Nor1 also showed marked induction at the mRNA level within 3 hours after PH in WT mouse livers. The induction of Nurr1 and Nor1 mRNA levels in Nur77 KO mouse livers was approximately twofold greater than that observed in WT controls at 3 hours after PH (Figure 1D). Overall, hepatic Nur77 exhibited a strong, transient induction during liver regeneration after PH, coupled with ERK1/2 activation to promote liver proliferation. These findings further support the notion that induced nuclear Nur77 in hepatocytes may be required to promote hepatocyte proliferation in response to PH.

Figure 1.

Early transient induction of Nur77, Nurr1, and Nor1 and activation of ERK1/2 in regenerating mouse livers. A: Hepatic mRNA levels of Nur77 in WT mice were determined by RT-qPCR at 0 to 48 hours after partial hepatectomy (PH). B: Protein levels of Nur77, phosphorylated (p-) ERK1/2, and total ERK1/2 in WT mice were determined at the same time points after PH or after sham surgery. C: Intracellular localization of Nur77 in WT mouse liver. Anti-Nur77 polyclonal antibody was used to determine the location of Nur77 (brown), and the nuclei were stained with hematoxylin (blue). D: Hepatic mRNA levels of Nurr1 and Nor1 were determined by RT-qPCR in WT and Nur77 KO mice at 0 to 48 hours after PH. Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 5. ∗P < 0.05. Original magnification: ×20 (C, top row); ×400 (C, bottom row).

Nur77 Deficiency Accelerates Liver Regeneration in Response to PH

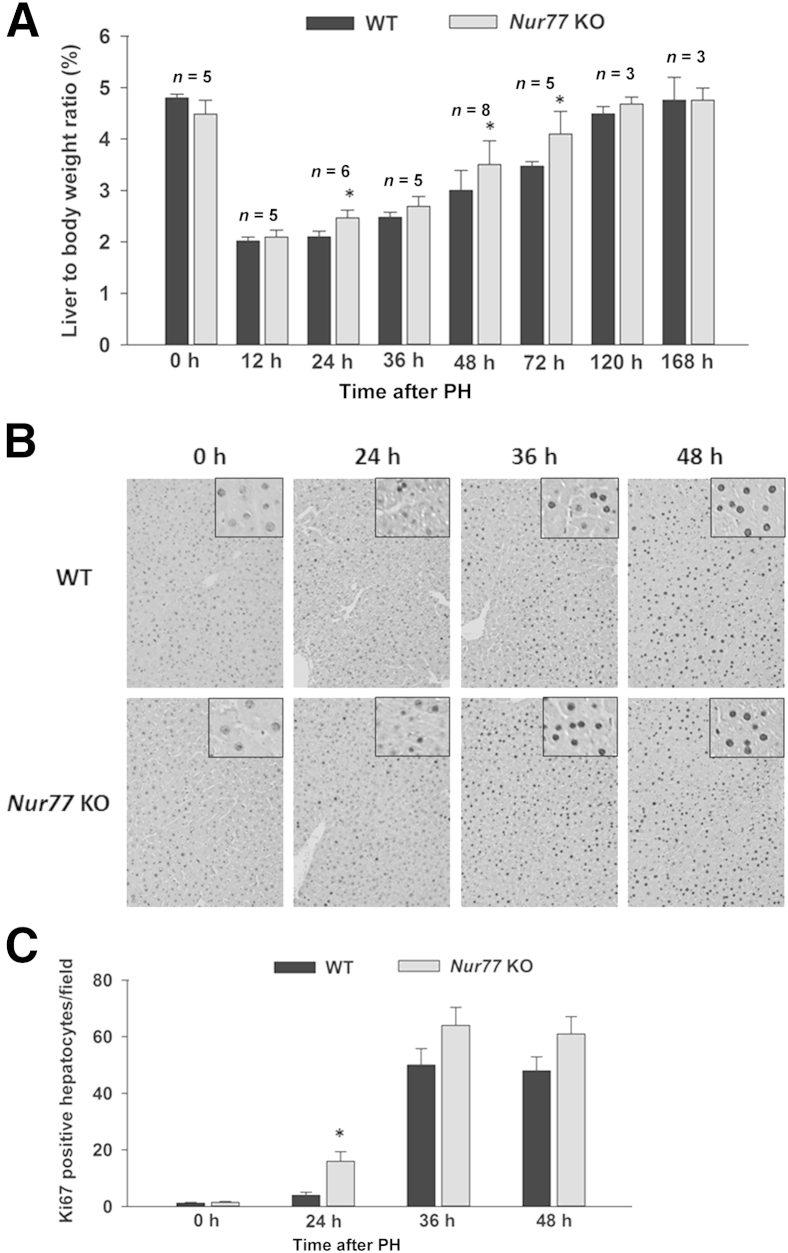

Liver-to-body weight ratios were significantly increased in regenerating Nur77 KO livers, compared with WT, at 24, 48, and 72 hours after PH (Figure 2A). Liver-to-body weight ratio did not statistically differ between WT and KO mice subjected to sham operation at the time points studied (data not shown). The increase in liver-to-body weight ratio in Nur77 KO livers correlated with increased cell proliferation, as demonstrated by significantly higher numbers of Ki-67–positive hepatocytes at 24 hours after PH (Figure 2, B and C). Although the number of Ki-67–positive hepatocytes did not statistically differ between WT and Nur77 KO livers at 48 and 72 hours, a higher trend toward increased Ki-67 expression was noted in KO mouse livers. Furthermore, examination under high magnification (×400) revealed that hepatocytes were the major population of proliferating cells within 48 hours after PH. Thus, loss of Nur77 accelerated PH-induced hepatocyte proliferation.

Figure 2.

Nur77 KO mice exhibit accelerated liver regeneration after PH. A: Liver-to-body weight ratio was used as an index to monitor liver regeneration. B: Representative images of Ki-67 immunohistochemistry staining in WT and Nur77 KO mouse livers at 0 to 48 hours after PH (n = 5 mice per time point). The cellularity of the proliferating cells is seen at high magnification (insets). C: Numbers of Ki-67–positive hepatocytes were determined in five random ×20 microscopic fields for each liver section. Data are expressed as means ± SD. ∗P < 0.05. Original magnification: ×20 (main images); ×400 (insets).

Nur77 Deficiency Results in Early Induction of Cell-Cycle Gene Expression during Liver Regeneration

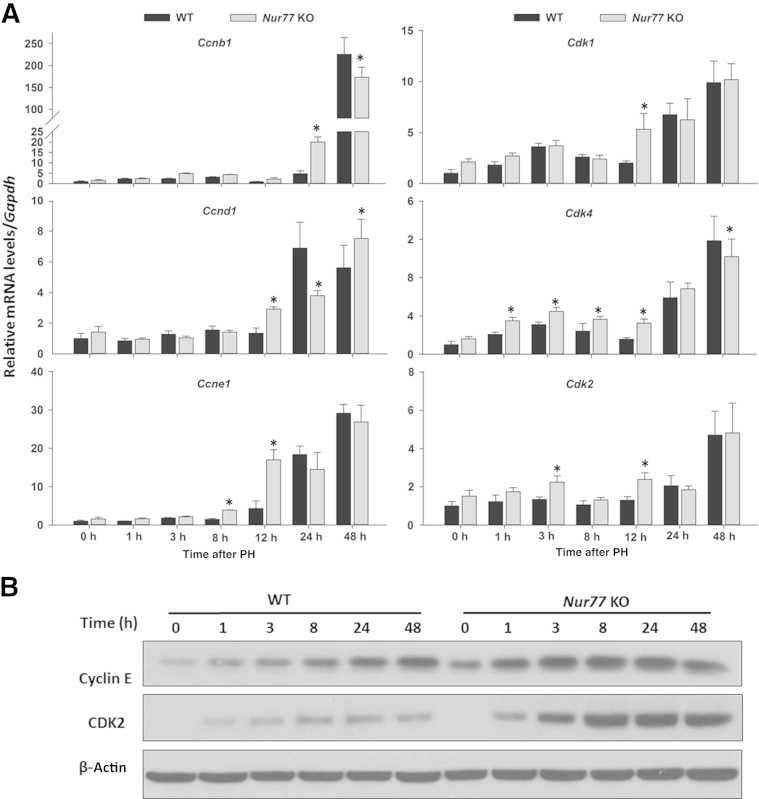

To gain further insight into the effect of Nur77 on hepatocyte cell-cycle progression, we studied the expression of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) (Figure 3). These cell-cycle genes were markedly up-regulated in Nur77 KO mouse livers within 12 hours after PH, compared with WT counterparts (Figure 3A). However, Ccne1, Cdk1, Cdk2, and Cdk4 mRNA levels in Nur77 KO livers had returned to WT levels by 24 hours, and only Cdk4 levels differed again at 48 hours. The cyclin E protein level was slightly higher in Nur77 KO than in WT mouse livers at baseline (0 hour). Moreover, the PH-induced cyclin E and CDK2 levels were much higher in Nur77 KO than in WT mice overall (Figure 3B). Thus, the lack of Nur77 resulted in early up-regulation of a panel of cell-cycle genes in regenerating livers, which may account for enhanced hepatocyte proliferation.

Figure 3.

Early induction of cell-cycle genes in Nur77 KO mouse liver after PH. A: Hepatic mRNA levels of cell-cycle genes were determined by RT-qPCR in WT and Nur77 KO mice at 0 to 48 hours after PH. B: Protein levels of cyclin E and CDK2 were determined by Western blot analysis in WT and Nur77 KO mice at 0 to 48 hours after PH. Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 5. ∗P < 0.05.

Nur77 KO Mice Exhibit Necrotic Injury and Hepatocyte Apoptosis in Response to PH

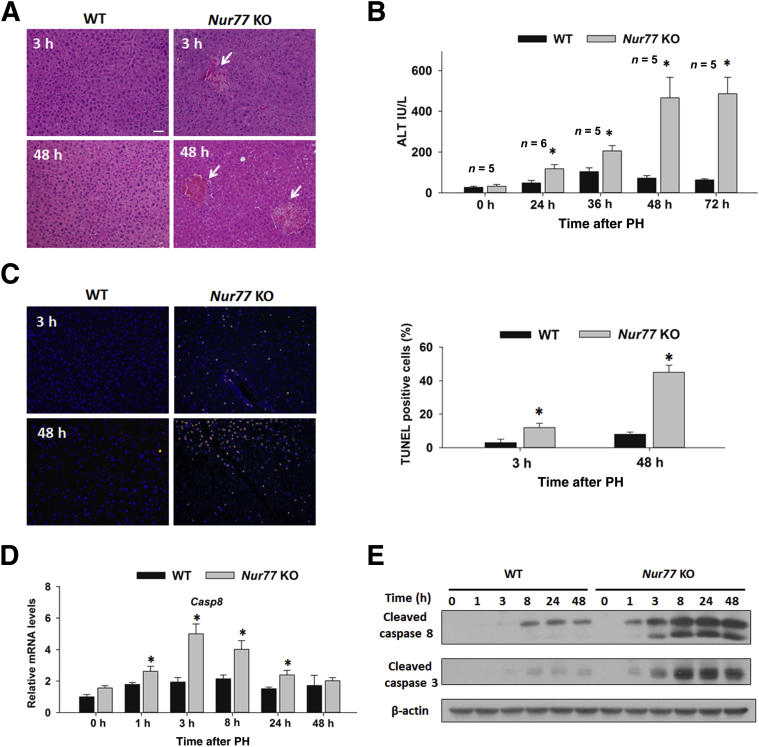

Despite accelerated liver regeneration, Nur77 KO mice paradoxically incurred liver damage after PH. An aberrant regenerative response accompanied by mononucleocyte infiltration and necrosis was observed in Nur77 KO mouse livers, compared with WT controls, as demonstrated by hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4A). Strikingly, 9/49 Nur77 KO mice (18%) exhibited hepatic necrosis within 21 days after PH, but no necrotic injury occurred in WT mice (Table 2). Concurrently, Nur77 KO mice also had elevated serum alanine aminotransferase activity, compared with WT mice (Figure 4B). TUNEL staining revealed that Nur77 KO mouse livers exhibited more TUNEL-positive cells, compared with WT livers, at 3 and 48 hours after PH (Figure 4C). Consistent with TUNEL assay findings, both mRNA levels of Casp8 and protein levels of cleaved caspase 8 and cleaved caspase 3 were induced in Nur77 KO livers at 1 to 24 hours after PH, compared with WT counterparts (Figure 4, D and E). Overall, accelerated liver regeneration in Nur77 KO mouse livers after PH coincided with focal necrosis and hepatocyte apoptosis.

Figure 4.

Nur77 KO regenerating liver exhibits injury markers. A: Hematoxylin and eosin staining of WT and Nur77 KO mouse livers at 3 and 48 hours after PH. Note focal necrosis (arrows). B: Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were determined in WT and Nur77 KO mice at 0 to 72 hours after PH. C: The same liver sections were labeled with an in situ cell death detection kit, with tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) red staining of apoptotic nuclei, and were viewed under a fluorescence microscope. DAPI served as control, with nuclear staining in blue. The number of apoptotic nuclei was calculated in five random microscopic fields. D: Hepatic mRNA levels of Casp8 were determined by RT-qPCR in WT mice at 0 to 48 hours after PH. E: Protein levels of cleaved-caspase 3 and cleaved-caspase 8 were determined by Western blotting in WT and Nur77 KO mouse livers. Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 5 (D). ∗P < 0.05. Scale bar = 50 μm (A and C); original magnification, ×40.

Table 2.

The Incidence of Liver Necrosis in Regenerating WT and Nur77 KO Mouse Livers

| Time since PH | Necrotic injury [n/N (%)] |

|

|---|---|---|

| WT | Nur77 KO | |

| <24 hours | 0/25 | 5/21 |

| 36 hours | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| 48 hours | 0/8 | 3/8 |

| 72 hours to 21 days | 0/13 | 1/15 |

| Total | 0/51 (0) | 9/49 (18) |

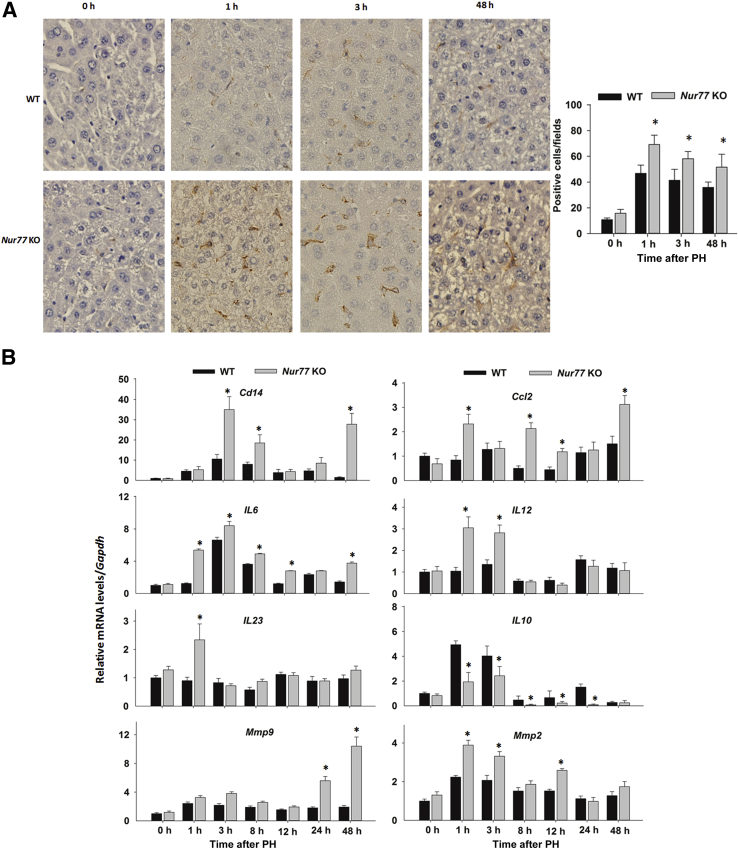

Infiltration of Activated Macrophages and Exacerbation of Inflammatory Response in Nur77 KO Mouse Livers after PH

To test the hypothesis that Nur77 deficiency results in dysregulation of KCs and subsequent liver injury, F4/80 immunostaining was performed to assess macrophage activation in regenerating WT and Nur77 KO mouse livers. There were more F4/80-positive cells in Nur77 KO livers than in WT counterparts at 1, 3, and 48 hours after PH (Figure 5A). In accord, the mRNA levels of Cd14, chemokine (C-C Motif) ligand 2 (Ccl2), and proinflammatory interleukin genes Il6, Il12, and Il23 were elevated in Nur77 KO regenerating livers, compared with WT livers, at several time points (Figure 5B). Moreover, regenerating Nur77 KO livers also exhibited higher mRNA levels of matrix metallopeptidase genes Mmp2 and Mmp9 at 48 hours after PH, compared with WT livers. By degrading the extracellular matrix, MMPs facilitate KC infiltration and plasminogen activator activity, events necessary for initiating liver regeneration.36 The elevated expression of these immune-response genes suggests greater KC activation in Nur77 KO regenerating livers, compared with WT. Moreover, the mRNA level of Il10 (encoding the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10) was suppressed in Nur77 KO regenerating livers, in contrast to WT. The reduced induction of IL-10 and increased expression of MMPs in Nur77 KO mice likely contributed to the liver injury and KC accumulation occurring in the early stages of PH-induced liver regeneration.

Figure 5.

Kupffer cell accumulation and increased proinflammatory signaling in Nur77 KO regenerating liver. A: Representative images of F4/80 immunohistochemical staining of WT and Nur77 KO mouse livers at 0 to 48 hours after PH. The numbers of F4/80-positive cells were calculated in five random microscopic fields. B: Hepatic mRNA levels of Cd14, Ccl2, Il6, Il12, Il23, Il10, and matrix metallopeptidases Mmp2 and Mmp9 were determined by RT-qPCR in WT and Nur77 KO mouse livers at 0 to 48 hours after PH. Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 5. ∗P < 0.05. Original magnification, ×20.

Differential Gene Expression Profiles in Regenerating WT and Nur77 KO Mouse Livers

To identify the potential Nur77-regulated pathways during liver regeneration, we performed a whole-genome microarray analysis to compare differential gene expression profiles between regenerating livers of WT and Nur77 KO mice at 3 hours after PH, the time point at which Nur77 levels peaked in WT livers. Microarray analysis identified 2088 genes (1335 up-regulated and 753 down-regulated) with a greater than 1.5-fold change at the mRNA level due to Nur77 deficiency during liver regeneration. The expression of 75 genes was validated by RT-qPCR (n = 3). Biological function analysis of those differentially expressed genes indicated that a majority of up-regulated genes regulate inflammatory response, cell apoptosis, cell cycle, and proliferation, as well as transcription regulation. By contrast, the down-regulated genes participate in oxidation reduction, glucose metabolism, and lipid homeostasis, as well as fatty acid and steroid biosynthesis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pathway Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in Regenerating Liver of WT and Nur77 KO Mice after PH

| Biological function∗ | Number of genes | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated (745 genes) | ||

| Regulation of transcription | 206 | 5.5 × 10−12 |

| Regulation of RNA metabolic process | 128 | 8.8 × 10−6 |

| Inflammatory response (immune response) | 68 | 3.5 × 10−4 |

| Regulation of apoptosis | 54 | 5.7 × 10−4 |

| Cell cycle | 57 | 6.7 × 10−4 |

| Response to wounding | 37 | 7.0 × 10−4 |

| Protein localization | 64 | 3.0 × 10−3 |

| Response to DNA damage stimulus | 30 | 3.3 × 10−3 |

| Protein amino acid phosphorylation | 55 | 5.0 × 10−3 |

| Regulation of cell proliferation | 46 | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| Down-regulated (200 genes) | ||

| Oxidation reduction | 55 | 1.0 × 10−8 |

| Organic acid biosynthetic process | 15 | 4.5 × 10−4 |

| Glucose metabolic process | 13 | 3.9 × 10−3 |

| Lipid homeostasis | 20 | 5.9 × 10−3 |

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | 9 | 7.5 × 10−3 |

| Nitrogen compound biosynthesis | 20 | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| Steroid biosynthesis | 13 | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| Protein complex assembly | 16 | 1.5 × 10−2 |

| Protein localization | 39 | 1.6 × 10−2 |

Global biological function annotation of 2088 differentially expressed genes (1335 up-regulated and 753 down-regulated genes, KO versus WT) from the DAVID bioinformatics database version 6.7 (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov). Functional pathways and processes with P < 0.05 and Bonferroni value <0.1 were accepted.

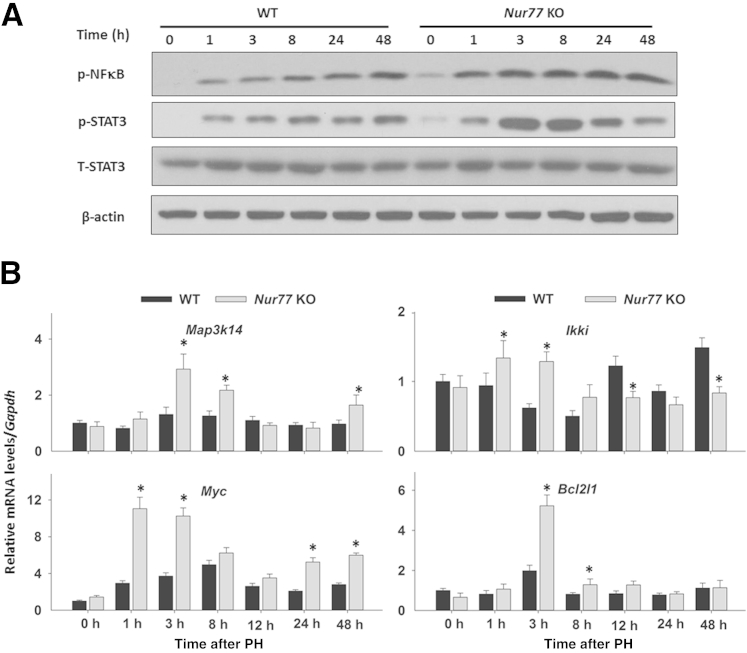

Early Activation of the NF-κB/STAT3 Signaling Pathway in Regenerating Nur77 KO Mouse Livers

Because Nur77 negatively regulates NF-κB activity and because NF-κB–mediated STAT3 activation is one of most studied proliferative mechanisms after PH,21,28 we hypothesized that NF-κB/STAT3 signaling might mediate the accelerated hepatocytes proliferation caused by Nur77 deficiency. Western blotting revealed higher levels of NF-κB and STAT3 in Nur77 KO than in WT livers, which is in agreement with elevated expression level of cyclin E in the Nur77 KO mouse livers. PH induced the expression of activated NF-κB as well as STAT3, but the inductions were higher in KO than WT (Figure 6A). In accord, Map3k14 and Ikki (two upstream genes that mediate NF-κB activation) were up-regulated at 1 and 3 hours after PH (Figure 6B). Il6, encoding a cytokine mediator of STAT3 phosphorylation, also showed greater induction in Nur77 KO regenerating livers, compared with WT livers, at 1 hour after PH (Figure 5B). Furthermore, expression of the STAT3- and NF-κB–regulated genes Myc and Bcl2l1 was significantly higher in Nur77 KO livers, compared with WT counterparts (Figure 6B). NF-κB also controls several key cell-cycle regulatory genes (Ccnd1, Ccnd2, Cdk2, Cdk4, and Cdk6) and inflammation genes (Il6, Ccl2, Mmp2, and Mmp9).37,38 Correspondingly, those genes exhibited greater induction in Nur77 KO than in WT regenerating livers. These findings suggest that increased activation of the NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway causes a compensatory induction of cell-cycle genes to facilitate liver regeneration in Nur77 KO mice.

Figure 6.

Activation of the hepatic NF-κB and STAT3 pathway occurs earlier in Nur77 KO than in WT mouse livers after PH. A: Protein levels of p-NF-κB (p65), p-STAT3, and total STAT3 were determined by Western blot analysis in WT and Nur77 KO mice at 0 to 48 hours after PH. B: Hepatic mRNA levels of Map3k14, Ikki, Myc, and Bcl2l1 were determined by RT-qPCR in WT and Nur77 KO mice at 0 to 48 hours after PH. Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 5. ∗P < 0.05.

Discussion

Nur77 is a unique transcription factor that exerts opposing effects on survival and death depending on its intracellular localization.14 Nur77 functions in the nucleus as an oncogenic survival factor, but it becomes a proapoptotic factor when certain death stimuli induce its nuclear export to the cytosol.23–25 Mitogenic and stress stimuli elevate Nur77 levels in the nucleus, where it transcriptionally up-regulates target genes (including those encoding TXNDC5, survivin, and CCND2) to suppress cellular stress and promote proliferation.39–41 In accord, our findings showed that Nur77 is rapidly induced (in 1 to 3 hours) in the nuclei of hepatocytes after PH in WT mice, which suggests that the increased hepatocyte proliferation can be relevant to the induction of nuclear Nur77 in hepatocytes. In addition, such induction was associated with ERK1/2 activation, a critical signaling pathway for cell growth and division.

In Nur77 KO mouse, there was also a 2.4-fold increase of Nur77 at 1 hour after PH, which might be ascribed to nonfunctional transcripts because the promoter of Nur77 remained intact in the KO mice. Furthermore, Nurr1 and Nor1 were also induced at 3 hours after PH in WT mouse livers, suggesting their importance in initiation of liver regeneration. In Nur77 KO mouse, the levels of Nurr1 and Nor1 were higher than in WT mice at 3 hours after PH. Thus, the induced Nurr1 and Nor1 might compensate for the lack of Nur77 and contribute in part to the completion of liver regeneration in Nur77 KO mouse. Additionally, because Nur77 acts in a ligand-independent manner and is unstable at both mRNA and protein levels in vivo, the regulation of its expression and post-translation modification are important to its function.42

Although the exact mechanism by which Nur77 is induced during liver regeneration remains to be established, in the present study Nur77 deficiency hastened early PH-induced liver regeneration by enhancing expression of cyclin–CDK complexes. Nur77 deficiency concurrently resulted in KC dysregulation and an exacerbated inflammatory response. Nur77 KO mice thus exhibited abnormal degrees of necrotic injury and hepatocyte apoptosis during PH-induced liver regeneration. The absence of cellular stress mitigation by Nur77 may contribute to the atypical hepatic damage incurred by Nur77 KO mice after PH. Such Nur77 deficiency–associated liver injury possibly triggered compensatory hepatocyte proliferation. Overall, our findings support the notion that Nur77 participates in early liver regeneration by modulating cytokine-mediated inflammatory and apoptosis processes.

Successful regeneration of the mouse liver after PH requires coordinated changes in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism to supply sufficient energy for proliferating hepatocytes.43,44 Hepatic Nur77 has been shown to promote gluconeogenesis by binding the Nur77 response element in the promoter regions of G6pc, Fbp1, Fbp2, and Eno3 to increase their expression.17 Furthermore, Nur77 has been implicated in regulating hepatic lipid metabolism through its inhibition of SREBP1c activity.45 Our gene profiling data revealed that genes involved in oxidation reduction, glucose metabolism, and lipid homeostasis pathways were down-regulated at 3 hours in regenerating livers of Nur77 KO mice, compared with WT. Insufficient energy mobilization and elevated oxidative stress might thus elicit the excessive hepatic inflammation and injury observed in Nur77 KO mice after PH. These findings support the notion that Nur77 exerts a profound effect on regulating energy metabolism in addition to cell growth and death during PH-induced liver regeneration.

Liver regeneration is intricately orchestrated by cytokines, growth factors, and metabolic stimuli from the hepatic environment.8 Thus, the innate immune system plays an integral part in the initiation of liver regeneration.8,10 It is widely accepted that KCs release IL-6 and TNF-α in response to PH to activate NF-κB in macrophages and hepatocytes, which subsequently initiate the regeneration process. In hepatocytes, activation of NF-κB by TNF-α leads to the transcription of prosurvival genes, and IL-6 activates STAT3 through the IL-6R/gp130 complex to enhance survival pathways.1,46 Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 negatively regulates liver regeneration through suppression of STAT3 activation in mouse hepatocytes.47 In the present study, regenerating Nur77 KO mouse livers exhibited a more proinflammatory environment, compared with WT, based on differential expression of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and IL-23 between the two genotypes. In accord, increased activation of NF-κB/STAT3 signaling was observed in regenerating Nur77 KO livers after PH.

Normally, quiescent WT mouse hepatocytes re-enter the cell cycle approximately 36 hours after PH. By contrast, Nur77 KO mouse livers exhibited early induction of cell-cycle genes (Ccnd1, Ccne1, Cdk1, Cdk2, and Cdk4) by 12 hours after PH. Taken together, the more robust activation of NF-κB/STAT3 signaling in Nur77 KO mice might be responsible for up-regulating cell-cycle genes and subsequently causing compensatory hepatocyte proliferation.

Substantial evidence shows that rodent livers generally achieve complete hepatic mass restoration without incurring injury after PH, and it is proposed that coordinated interaction between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines limits the inflammatory response to an extent appropriate to stimulating proliferation while minimizing injury. Nur77 is known to regulate multiple genes involved in inflammation, apoptosis, and cell-cycle progression in macrophages, and thus it may be critical in mediating liver regeneration.48 In the present study, gene profiling after PH in WT and Nur77 KO mice provided further insight into the molecular mechanisms pertaining to the role of Nur77 in liver regeneration. Our microarray data showed that, during liver regeneration, Nur77 is involved mainly in modulating inflammation, cell apoptosis, proliferation, and energy metabolism. In diseases caused by an excessive inflammatory response, Nur77 is a key regulator of cytokine and growth factor dysregulation.48 Emerging evidence has strongly linked excessive inflammation to tumor progression, with the presence of inflammatory cells and mediators promoting tumor growth, and the molecular mechanisms used by proliferating hepatocytes during PH-induced liver regeneration may in turn be applicable to cancer cells.

In summary, Nur77 is essential for regulating the early signaling of liver regeneration by controlling cytokine-mediated inflammatory and apoptosis processes. The compensatory early induction of cell-cycle genes due to increased NF-κB and STAT3 activation may contribute to the complete restoration of liver mass in Nur77 KO mice. Nur77 deficiency–associated liver injury can be compensated by other pathways controlling liver regeneration. In the Nur77 KO model, induction of other NR4A genes (including Nurr1 and Nor1) might have such a role in regeneration. Our present findings suggest that Nur77 is crucial for suppressing hepatic inflammation and preventing necrotic injury in the early stage of PH-induced liver regeneration.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Teixeira for assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

Y.H. and Q.Z. performed experiments, analyzed data, generated figures, and prepared the manuscript; H.L. performed experiments, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript; T.C. and Y.L. assisted in experiments and prepared the manuscript; Y.Y.W. generated the idea and supervised overall performance of the project.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants R01CA053596 and R01DK092100 (Y.-J.Y.W.).

Y.H. and Q.Z. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: None declared.

References

- 1.Michalopoulos G.K. Liver regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:286–300. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su A.I., Guidotti L.G., Pezacki J.P., Chisari F.V., Schultz P.G. Gene expression during the priming phase of liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11181–11186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122359899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeishi T., Hirano K., Kobayashi T., Hasegawa G., Hatakeyama K., Naito M. The role of Kupffer cells in liver regeneration. Arch Histol Cytol. 1999;62:413–422. doi: 10.1679/aohc.62.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu C.S., Jiang Y., Zhang L.X., Chang C.F., Wang G.P., Shi R.J., Yang Y.J. The role of Kupffer cells in rat liver regeneration revealed by cell-specific microarray analysis. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:229–237. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taub R., Greenbaum L.E., Peng Y. Transcriptional regulatory signals define cytokine-dependent and -independent pathways in liver regeneration. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:117–127. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guttridge D.C., Albanese C., Reuther J.Y., Pestell R.G., Baldwin A.S. NF-kappa B controls cell growth and differentiation through transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5785–5799. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W., Liang X., Kellendonk C., Poli V., Taub R. STAT3 contributes to the mitogenic response of hepatocytes during liver regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28411–28417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202807200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fausto N., Campbell J.S., Riehle K.J. Liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2006;43(2 Suppl 1):S45–S53. doi: 10.1002/hep.20969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scearce L.M., Laz T.M., Hazel T.G., Lau L.F., Taub R. RNR-1, a nuclear receptor in the NGFI-B/Nur77 family that is rapidly induced in regenerating liver. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8855–8861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeAngelis R.A., Markiewski M.M., Lambris J.D. Liver regeneration: a link to inflammation through complement. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;586:17–34. doi: 10.1007/0-387-34134-X_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markiewski M.M., DeAngelis R.A., Lambris J.D. Liver inflammation and regeneration: two distinct biological phenomena or parallel pathophysiologic processes? Mol Immunol. 2006;43:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taub R. Liver regeneration: from myth to mechanism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:836–847. doi: 10.1038/nrm1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin L.J., Boucher N., El-Asmar B., Tremblay J.J. cAMP-induced expression of the orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 in MA-10 Leydig cells involves a CaMKI pathway. J Androl. 2009;30:134–145. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.006387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moll U.M., Marchenko N., Zhang X.K. p53 and Nur77/TR3—transcription factors that directly target mitochondria for cell death induction. Oncogene. 2006;25:4725–4743. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y., Bruemmer D. NR4A orphan nuclear receptors: transcriptional regulators of gene expression in metabolism and vascular biology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1535–1541. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.191163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohan H.M., Aherne C.M., Rogers A.C., Baird A.W., Winter D.C., Murphy E.P. Molecular pathways: the role of NR4A orphan nuclear receptors in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3223–3228. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pei L., Waki H., Vaitheesvaran B., Wilpitz D.C., Kurland I.J., Tontonoz P. NR4A orphan nuclear receptors are transcriptional regulators of hepatic glucose metabolism. Nat Med. 2006;12:1048–1055. doi: 10.1038/nm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maruyama K., Tsukada T., Ohkura N., Bandoh S., Hosono T., Yamaguchi K. The NGFI-B subfamily of the nuclear receptor superfamily (review) Int J Oncol. 1998;12:1237–1243. doi: 10.3892/ijo.12.6.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campos-Melo D., Galleguillos D., Sánchez N., Gysling K., Andrés M.E. Nur transcription factors in stress and addiction. Front Mol Neurosci. 2013;6:44. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2013.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y., Lin B., Agadir A., Liu R., Dawson M.I., Reed J.C., Fontana J.A., Bost F., Hobbs P.D., Zheng Y., Chen G.Q., Shroot B., Mercola D., Zhang X.K. Molecular determinants of AHPN (CD437)-induced growth arrest and apoptosis in human lung cancer cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4719–4731. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z.G., Smith S.W., Mclaughlin K.A., Schwartz L.M., Osborne B.A. Apoptotic signals delivered through the T-cell receptor of a T-cell hybrid require the immediate–early gene Nur77. Nature. 1994;367:281–284. doi: 10.1038/367281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin B., Kolluri S.K., Lin F., Liu W., Han Y.H., Cao X., Dawson M.I., Reed J.C., Zhang X.K. Conversion of Bcl-2 from protector to killer by interaction with nuclear orphan receptor Nur77/TR3. Cell. 2004;116:527–540. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolluri S.K., Bruey-Sedano N., Cao X., Lin B., Lin F., Han Y.H., Dawson M.I., Zhang X.K. Mitogenic effect of orphan receptor TR3 and its regulation by MEKK1 in lung cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8651–8667. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8651-8667.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang H., Zhan Q., Wan Y.J. Enrichment of Nur77 mediated by retinoic acid receptor β leads to apoptosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells induced by fenretinide and histone deacetylase inhibitors. Hepatology. 2011;53:865–874. doi: 10.1002/hep.24101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang H., Nie Y., Li Y., Wan Y.J. ERK1/2 deactivation enhances cytoplasmic Nur77 expression level and improves the apoptotic effect of fenretinide in human liver cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:910–916. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vacca M., Murzilli S., Salvatore L., Di Tullio G., D’Orazio A., Lo Sasso G., Graziano G., Pinzani M., Chieppa M., Mariani-Costantini R., Palasciano G., Moschetta A. Neuron-derived orphan receptor 1 promotes proliferation of quiescent hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1518–1529 e1513. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonta P.I., Matlung H.L., Vos M., Peters S.L.M., Pannekoek H., Bakker E.N.T.P., de Vries C.J.M. Nuclear receptor Nur77 inhibits vascular outward remodelling and reduces macrophage accumulation and matrix metalloproteinase levels. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:561–568. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harant H., Lindley I.J.D. Negative cross-talk between the human orphan nuclear receptor Nur77/NAK-1/TR3 and nuclear factor-kappaB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5280–5290. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chao C.Y., Cheing G.L. Microvascular dysfunction in diabetic foot disease and ulceration. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009;25:604–614. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S.L., Wesselschmidt R.L., Linette G.P., Kanagawa O., Russell J.H., Milbrandt J. Unimpaired thymic and peripheral T cell death in mice lacking the nuclear receptor NGFI-B (Nur77) Science. 1995;269:532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.7624775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H.X., Fang Y.P., Hu Y., Gonzalez F.J., Fang J.W., Wan Y.J.Y. PPAR beta regulates liver regeneration by modulating Akt and E2f signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Research Council . ed 8. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmittgen T.D., Livak K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo M., Gong L., He L., Lehman-McKeeman L., Wan Y.J. Hepatocyte RXRalpha deficiency in matured and aged mice: impact on the expression of cancer-related hepatic genes in a gender-specific manner. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:403. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovalovsky D., Refojo D., Liberman A.C., Hochbaum D., Pereda M.P., Coso O.A., Stalla G.K., Holsboer F., Arzt E. Activation and induction of NUR77/NURR1 in corticotrophs by CRH/cAMP: involvement of calcium, protein kinase A, and MAPK pathways. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1638–1651. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.7.0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohammed F.F., Pennington C.J., Kassiri Z., Rubin J.S., Soloway P.D., Ruther U., Edwards D.R., Khokha R. Metalloproteinase inhibitor TIMP-1 affects hepatocyte cell cycle via HGF activation in murine liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2005;41:857–867. doi: 10.1002/hep.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naugler W.E., Karin M. NF-kappaB and cancer—identifying targets and mechanisms. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt D., Textor B., Pein O.T., Licht A.H., Andrecht S., Sator-Schmitt M., Fusenig N.E., Angel P., Schorpp-Kistner M. Critical role for NF-kappaB-induced JunB in VEGF regulation and tumor angiogenesis. EMBO J. 2007;26:710–719. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S.O., Abdelrahim M., Yoon K., Chintharlapalli S., Papineni S., Kim K., Wang H., Safe S. Inactivation of the orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 inhibits pancreatic cancer cell and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6824–6836. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee S.O., Jin U.H., Kang J.H., Kim S.B., Guthrie A.S., Sreevalsan S., Lee J.S., Safe S. The orphan nuclear receptor NR4A1 (Nur77) regulates oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12:527–538. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen H.Z., Li L., Wang W.J., Du X.D., Wen Q., He J.P., Zhao B.X., Li G.D., Zhou W., Xia Y., Yang Q.Y., Hew C.L., Liou Y.C., Wu Q. Prolyl isomerase Pin1 stabilizes and activates orphan nuclear receptor TR3 to promote mitogenesis. Oncogene. 2012;31:2876–2887. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang S.A., Na H., Kang H.J., Kim S.H., Lee M.H., Lee M.O. Regulation of Nur77 protein turnover through acetylation and deacetylation induced by p300 and HDAC1. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:867–873. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dixit A., Baquer N.Z., Rao A.R. Inhibition of key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism in regenerating mouse liver by ascorbic acid. Biochem Int. 1992;26:143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernández M.A., Albor C., Ingelmo-Torres M., Nixon S.J., Ferguson C., Kurzchalia T., Tebar F., Enrich C., Parton R.G., Pol A. Caveolin-1 is essential for liver regeneration. Science. 2006;313:1628–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1130773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pols T.W.H., Ottenhoff R., Vos M., Levels J.H.M., Quax P.H.A., Meijers J.C.M., Pannekoek H., Groen A.K., de Vries C.J.M. Nur77 modulates hepatic lipid metabolism through suppression of SREBP1c activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:910–916. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang L.I., Mars W.M., Michalopoulos G.K. Signals and cells involved in regulating liver regeneration. Cells. 2012;1:1261–1292. doi: 10.3390/cells1041261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin S., Wang H., Park O., Wei W., Shen J., Gao B. Enhanced liver regeneration in IL-10-deficient mice after partial hepatectomy via stimulating inflammatory response and activating hepatocyte STAT3. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1614–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pei L.M., Castrillo A., Tontonoz P. Regulation of macrophage inflammatory gene expression by the orphan nuclear receptor Nur77. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:786–794. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]