Abstract

The gp41 protein of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) catalyzes fusion between HIV and host cell membranes. The ~180-residue ectodomain of gp41 is outside the virion and is the most important gp41 region for membrane fusion. The ectodomain consists of an apolar fusion peptide (FP) region followed by N-heptad repeat (NHR), loop, and C-heptad repeat (CHR) regions. The FP is critical for fusion and is hypothesized to bind to the host cell membrane. Large ectodomain constructs either with or without the FP are highly aggregated at physiologic pH but soluble in the pH 3–4 range with hyperthermostable hairpin structure with antiparallel NHR and CHR helices. The present study focuses on the large gp41 ectodomain constructs “Hairpin” (HP) containing NHR+loop+CHR and “FP-Hairpin” (FP-HP) containing FP+NHR+loop+CHR. Both proteins induce rapid and extensive fusion of anionic vesicles at pH 4 where the protein is positively-charged but do not induce fusion at pH 7 where the protein is negatively charged. This observation, along with lack of fusion of neutral vesicles at either pH supports the significance of attractive protein/membrane electrostatics in fusion. The functional role of the hydrophobic FP is supported by increases in the rate and extent of fusion for FP-HP relative to HP. There are two kinetically distinct fusion processes at pH 4: (1) a faster ~100 ms−1 process with rate strongly positively correlated with vesicle charge; and (2) a slower ~5 ms−1 process with extent strongly inversely correlated with this charge. The faster charge-dependent process is likely related to the electrostatic energy released upon initial monomer protein binding to the vesicle. After dissipation of this energy, the subsequent slower process is likely due to the equilibrium membrane-associated structure of the protein. The slower process may be more physiologically relevant because HIV/host cell fusion occurs at physiologic pH with gp41 restricted to the narrow region between the two membranes.

Previous solid-state NMR (SSNMR) of membrane-associated FP-HP has supported protein oligomers with FP’s in an intermolecular antiparallel β sheet. There was an additional population of molecules with α helical FPs and the samples likely contained a mixture of membrane-bound and -unbound protein. For the present study, samples were prepared with fully membrane-bound FP-HP and subsequent SSNMR showed dominant β FP conformation at both low and neutral pH. The fusogenic structure is likely β for the slow and perhaps the fast process. SSNMR also showed close contact of the FP with the lipid headgroups at both low and neutral pH whereas the NHR+CHR regions had contact at low pH and were more distant at neutral pH, consistent with the protein/membrane electrostatics.

Keywords: HIV, gp41, membrane fusion, solid-state NMR, fusion peptide, β sheet

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a class I enveloped virus surrounded by a membrane obtained from an infected host cell during viral budding [1]. Uninfected macrophage and T helper cells are targeted by HIV with subsequent joining (fusion) of the HIV and cell membranes and deposition of the viral capsid inside the cell. Infection is mediated by gp160 which contains non-covalently-associated gp41 and gp120 subunit proteins. Virion-associated gp160 is likely trimeric [2]. The gp41 is a monotopic protein of the viral membrane with ~180-residue extraviral and ~150-residue intraviral domains (Fig. 1). Gp120 is ~500 residues and associated with the gp41 ectodomain. The gp41 ectodomain plays a critical role in fusion and includes a ~20-residue fusion peptide (FP), N-heptad repeat (NHR), loop, C-heptad repeat (CHR), and membrane-proximal external region (MPER). Fusion models typically show partial insertion of the FP in the cell membrane and partial insertion of the MPER in the viral membrane. High-resolution structures of the gp41 ectodomain lacking the FP and MPER show a helical hairpin with antiparallel NHR and CHR helices [3–5]. In addition, the structures (at >2 mM protein concentration and pH 3) show a molecular trimer containing an interior bundle of three parallel helical NHRs and three antiparallel helical CHRs closely packed in the exterior groves of the NHR bundle. Because of its thermostability, the hairpin structure has been considered to be the final state of the gp41 ectodomain during fusion. At lower protein concentrations, the ectodomain remains highly helical but is monomeric [6,7]. The ectodomain can also be hexameric or more highly aggregated and the oligomerization states depend on pH, protein sequence, and solution additives [7,8]. Protein monomers are also predominant at low pH for gp41 constructs that include the TM domain although it is not known whether or not the TM domains of the trimer dissociate during HIV/cell fusion [9].

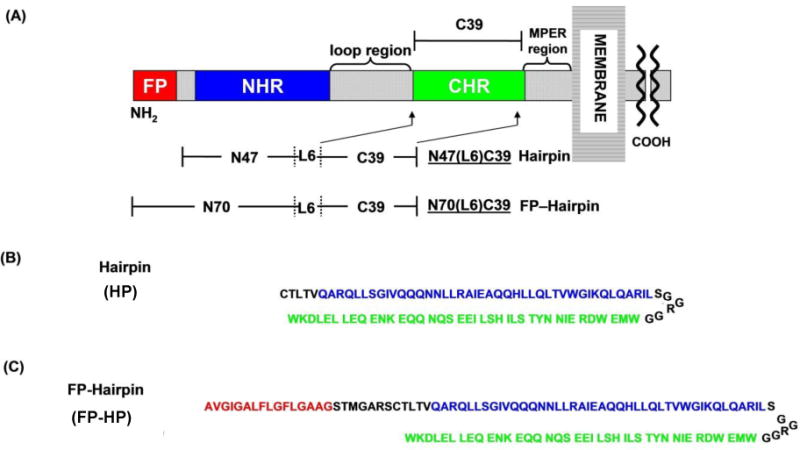

Figure 1.

(A) Ectodomain of the HIV gp41 protein showing domains including fusion peptide (FP), N-heptad repeat (NHR), loop, C-heptad repeat (CHR), and membrane-proximal external region (MPER). (B, C) Amino acid sequences of the Hairpin (HP) and FP-Hairpin (FP-HP) proteins with color-matching with panel A. The sequences of HP and FP-HP are from the HXB2 laboratory strain of HIV-1. Using gp160 numbering, HP includes [535–581(M535C)]-[SGGRGG]-[628–666] and FP-HP includes [512–581(M535C)]-[SGGRGG]-[628–666]. The first bracket for HP includes much of the NHR for HP and the first bracket for FP-HP includes the full FP and much of the NHR. For both constructs, the third bracket includes much of the CHR. The intervening SGGRGG is a non-native loop shorter than the ~20-residue native loop but still allows formation of a stable hairpin with antiparallel NHR and CHR helices.

Experiments and models support lipid mixing between the outer leaflets of the HIV and cell membranes as the first membrane topological change during fusion [1]. The resultant membrane state is “hemifusion”, i.e. a shared bilayer interface between HIV and the cell but no mixing of contents between the two bodies. The shared bilayer then breaks to form a “fusion pore” which then expands to create a single contiguous bilayer which envelopes the HIV capsid and cell. Although the relative timings of ectodomain and membrane topological changes are still under investigation, some experiments have been interpreted to support formation of a final gp41 state after lipid mixing and fusion pore creation and before pore expansion [10]. The effects of gp41 mutations on gp160-mediated fusion and HIV infection have also been investigated. One significant result was trans-dominant reduction in fusion and infection with the V2E mutation in the FP region of gp41 [11]. This result supports a requirement of multiple gp41 trimers for fusion [12].

The present paper focuses on the “Hairpin” (HP) and “FP-Hairpin” (FP-HP) large ectodomain constructs that respectively include much of the NHR+CHR and FP+NHR+CHR regions [13]. Fig. 1 displays their sequences which are derived from the HXB2 laboratory strain of HIV. Both proteins have a stable NHR/CHR helical fold and induce vesicle fusion under some conditions [14,15]. The final state is typically a multi-vesicle aggregate similar to the multicellular “syncytia” aggregates that form in cell culture with HIV infection [16]. Intervesicle contents mixing has not typically been observed in protein-induced vesicle fusion because of the rapid leakage from the vesicles.

Studies-to-date on large ectodomain constructs like HP and FP-HP have both provided ideas and raised questions relevant to fusion. Some results support requirements of low pH (3–4) and anionic lipids for rapid and extensive vesicle fusion [15,17,18]. To date, different studies used vesicles with either phosphatidylserine (PS) or phosphatiylglycerol (PG) anionic lipids but there has not been direct comparison between the two lipid types. For vesicles with PG, there was little fusion at pH 7. The ectodomain is positively charged at pH 4 and negatively charged at pH 7 so the combination of low pH and anionic lipids may reflect an underlying requirement for fusion of attractive protein/vesicle electrostatic energy. This energy could increase protein binding and/or contribute to the activation energy of fusion, and/or locally heat the membrane. At pH 4, the electrostatic energy will be different for PG and PS lipids because they carry full and partial negative charges, respectively. Protein binding to vesicles at pH 7 and consequent fusion may also be impacted by aggregation of ectodomain protein in the pH 7 solution [7,19]. By contrast, the protein is soluble at pH ≤ 4 and is predominantly monomeric for [protein] <100 μM. Because of gp41 ectodomain aggregation at neutral pH, many biophysical studies including high-resolution structures have used stock protein solutions with pH ≤ 4. Example studies and results for HP protein include circular dichroism which showed >95% helicity at ambient temperature and calorimetry which showed a melting temperature of 110 °C and melting enthalpy of 65 kcal/mole [13,14]. Similar results were obtained for FP-HP and other large ectodomain constructs [17].

Solid-state NMR (SSNMR) spectroscopy has also been applied to probe the structure of FP-HP in its membrane-associated form [14]. Protein stock at low pH was added dropwise to vesicle suspensions maintained at neutral pH, followed by centrifugation and harvesting the pellet for SSNMR. The spectra were consistent with a highly helical Hairpin domain and a ~1:1 mixture of molecules with either α helical or β sheet FPs. The β sheet was formed by multiple proteins whose FPs were arranged in antiparallel rather than parallel geometry [20]. There was also a distribution of antiparallel β sheet registries. If the highly helical Hairpin region is a molecular trimer, the antiparallel FP β sheet could reflect interleaved FPs from two different trimers. This result correlates with predominant hexamers for gp41 ectodomain constructs under some conditions [7,8]. Because of protein aggregation in neutral pH aqueous solution, the SSNMR samples could also have contained a fraction of aggregated protein that was not membrane-associated. The relative fractions of membrane-associated and non-associated FP-HP with β or α FPs were not known.

The present work addresses some questions raised by these earlier studies. Significant results include negligible protein-induced fusion of neutral vesicles at either low or neutral pH and negligible fusion of anionic vesicles at neutral pH. Rapid and extensive fusion was observed for anionic vesicles at low pH. Fusion rates and extents were analyzed for vesicles with different fractions of PG and PS lipids and two kinetic processes were detected. The rate of the faster process was strongly positively correlated with vesicle anionic charge while the extent of the slow process was inversely correlated with this charge. The slow process may be more relevant for HIV/cell fusion at neutral pH.

Fully-membrane-associated FP-HP samples were prepared with anionic vesicles and low pH where the protein did not aggregate. The SSNMR spectra of these samples showed that the β FP structure was predominant. The β structure was also predominant when the sample pH was increased to 7. Protein-to-lipid headgroup contact in both low and neutral pH samples was probed by protein 13CO to lipid 31P SSNMR. There was greater contact for the NHR+CHR region at low pH relative to neutral pH which is consistent with protein/membrane electrostatics. There was close membrane contact of the FP at both pH’s which is consistent with FP insertion via the hydrophobic effect.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Most other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. HP contains N-heptad repeat (NHR) + short non-native loop + C-heptad repeat (CHR) and FP-HP contains FP + HP (Fig. 1). Protein with non-native loop has similar physical properties to protein with the ~20-residue native loop including very high fractional helicity and Tm ≈ 110 °C [13,14,17]. The gp160-numbered amino-acid sequences from the HXB2 laboratory strain of HIV-1 are: FP (512–534); NHR (535(M535C)–581); and CHR (628–666). FP-HP typically had a single backbone 13CO label and a single backbone 15N label in the FP region that were directly-bonded. FP-HP_A1CV2N had A1 13CO and V2 15N labels, FP-HP_L7CF8N had L7 13CO and F8 15N labels, and FP-HP_G10CF11N had G10 13CO and F11 15N labels.

HP and FP-HP proteins were produced and purified as previously described [13,15,20]. Briefly, FP was synthesized by t-boc chemical synthesis and the subsequent cleavage with hydrogen fluoride was done by Midwest Biotech. HP was synthesized by bacterial expression and FP-HP was produced using native chemical ligation of purified FP and HP. Purifications were done by reversed-phase HPLC and final purities were typically >95% as assessed by mass spectrometry. Typical purified yields were >100 mg FP per t-boc synthesis, ~50 mg HP per L bacterial culture, and ~5 mg FP-HP from a ligation reaction with ~10 mg FP and ~50 mg HP.

Protein-induced vesicle fusion

Vesicles were prepared with lipid and cholesterol (Chol) in 2:1 mole ratio which was intermediate between the ratios for the membrane of host cells and the membrane of HIV [21]. The membranes always contained electrically neutral phosphatidylcholine (PC) lipids because this is the most common headgroup of membranes of cells infected by HIV. The membranes typically contained an anionic lipid (AL) with either phosphatidylgycerol (PG) or phosphatidylserine (PS) headgroup and the AL:PC mole ratio varied between 0 and 1. Lipids typically contained 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl acyl chains.

A corollary “labeled” vesicle sample was prepared for each “unlabeled sample” described above and contained additional 0.02 mole fractions of fluorescent lipid {N-(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)(ammonium salt) dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine} and quenching lipid {N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl)(ammonium salt) dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine}. For each sample, lipid and Chol was dissolved in chloroform:methanol (9:1 v/v) and excess solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The film was suspended in 25 mM citrate buffer, homogenized by freeze-thaw cycles, and extruded through a filter with 100 nm diameter pores. Unlabeled and labeled vesicle solutions were mixed in a 9:1 ratio and the pH was adjusted using 1 M HCl or 1 M NaOH. Protein-induced vesicle fusion was detected via lipid mixing between labeled and unlabeled vesicles with consequent higher fluorescence because of longer average fluorophore-quencher distance. Fluorescence was detected: (1) for the initial labeled+unlabeled vesicle solution; (2) with time-resolution after addition of an aliquot of protein solution; and (3) after addition of an aliquot of Triton X-100 detergent that solubilized the vesicles and maximized fluorescence. The respective fluorescence values were F0, F(t), and Fmax and the percent vesicle fusion was calculated:

| (1) |

Typical experimental conditions included: (1) PTI QW4 fluorimeter with 467 nm excitation and 530 nm detection wavelengths; (2) vesicles in 1400 μL volume and [total lipid] = 150 μM and [Chol] = 75 μM; (3) constant stirring; (4) protein:lipid (PC+AL) = 1:700 achieved with a 7.5 μL aliquot of 40 μM protein in 10 mM formate buffer at pH 3.2 with 0.2 μM TCEP reducing agent; (5) syringe injection of protein solution to reduce assay dead time to ~ 1s; (6) 1 s time increments for F(t); and (7) 0.08% w/v Triton X-100 achieved with a 12 μL aliquot of 10% Triton X-100. The protein:lipid = 1:700 ratio was chosen in part because there was light scattering from the fused vesicles for higher ratios.

SSNMR sample preparation

Vesicles were prepared as described above with composition PC:PG:Chol (8:2:5) mole ratio. Ether-linked lipids were used because they lacked carbonyl (CO) carbons and there was consequently lower natural abundance 13CO SSNMR signal. Protein solution was added dropwise to the vesicle solution with constant stirring, the mixture was centrifuged, and the proteoliposome pellet was packed into a magic angle spinning (MAS) SSNMR rotor. Typical experimental conditions included: (1) 50 μmole lipid, 25 μmole Chol, and 1 μmole protein; 2 mL initial volume of vesicle solution; and 10 mL volume of protein solution in 10 mM formate buffer at pH 3.2; (3) centrifugation at 30000g; and (4) MAS rotor with 4 mm diameter and ~50 μL sample volume. For “method 1”, the vesicle solution was buffered with 5 mM HEPES at pH 7.2 and this pH was maintained during protein addition. For “method 2”, the vesicle solution was buffered with 10 mM formate at pH 3.2 and there appeared to be extensive protein-induced vesicle fusion as evidenced by opacity and precipitation of proteoliposomes. After SSNMR spectra were obtained for the sample at pH 3.2, the sample pH was sometimes increased by: (1) removal of the pH 3.2 pellet from the SSNMR rotor; and (2) suspension in 250 μL of 25 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.2; (3) centrifugation; and (4) repacking of the pH 7.2 pellet in the rotor. After SSNMR were obtained for the pH 7.2 “pH-swapped” sample, the sample pH was sometimes taken back to pH 3.2 by: (1) removal of the pH 7.0 pellet from the rotor; and (2) suspension in 500 μL of 50 mM formate buffer at pH 3.2; (3) centrifugation; and (4) repacking of the pH 3.2 pellet in the rotor. SSNMR spectra were then obtained for this “reverse-swapped” sample.

SSNMR spectroscopy

Spectra were collected on a 9.4 T instrument (Agilent Infinity Plus) with triple-resonance MAS probe tuned to either 1H, 13C, and 15N frequencies or 1H, 13C, and 31P frequencies. 13C S0 and S1 rotational-echo double-resonance (REDOR) spectra were acquired [22,23]. The reduction in 13CO intensity in the S1 spectrum relative to S0 was used to probe proximity of labeled (lab) and natural abundance (na) 13CO nuclei to either lab FP-HP 15N or membrane headgroup 31P nuclei. In particular, the 13CO-15N ΔS (= S0 – S1) REDOR difference spectrum was dominated by the signal of the lab 13CO site in the FP region with attenuation of signals from the other ~130 na 13CO sites in the protein [24]. Spectral contributions with either lower or higher 13CO shift could then be respectively assigned to molecules with either β or α conformation at the lab site and the relative β and α populations determined from the signal intensities [25,26]. 13CO-31P REDOR spectra were acquired for different dephasing times (τ’s) and the rate and extent of buildup of the 13CO ΔS/S0 intensity ratio with τ was used to assess the proximity of lab and na 13CO sites to the membrane lipid headgroups [27].

Calibration of the rf fields and validation of the experimental setups were done as described previously [28,29]. Typical experimental conditions included: (1) 8.0 or 10.0 kHz MAS frequency and sample cooling with nitrogen gas at −50 °C to reduce molecular motion that reduces signal intensity; (2) 2.0 ms dephasing time for 13CO-15N REDOR and an array of dephasing times between 2.0 and 48.0 ms for 13CO-31P REDOR; (3) 13C π pulse at the end of each rotor cycle during the dephasing period (except the last cycle) and 15N or 31P π pulse at the midpoint of each rotor cycle during the dephasing period of the S1 acquisition; (4) 1H π/2 and cross-polarization fields of ~50 kHz and decoupling field of ~90 kHz; (5) 13C ramped cross-polarization field from 40 to 45 kHz and π pulse field of ~45 kHz; (6) 15N and 31P π pulse fields of ~25 and ~50 kHz, respectively; (7) pulse delay of 1 s; (8) alternate acquisition of S0 and S1 scans with summing of 5000–50000 scans; (9) spectral processing with 100 Hz Gaussian line broadening and baseline correction; (10) external 13C shift referencing using the methylene peak of adamantane at 40.5 ppm which allows direct comparision of the SSNMR 13CO shifts to database distributions of liquid-state NMR 13COα and 13COβ shifts [30]; and (11) 13COα intensities determined from integration of the 180→176 ppm shift interval of 13C-31P REDOR spectra of the FP-HP_G10CF11N sample, G10β intensities from integration of the 172→169 ppm shift interval of this sample, and A1β intensities from integration of the 174.5→171.5 ppm shift interval of the FP-HP_A1CV2N sample.

Results

Vesicle fusion requires attractive electrostatic energy

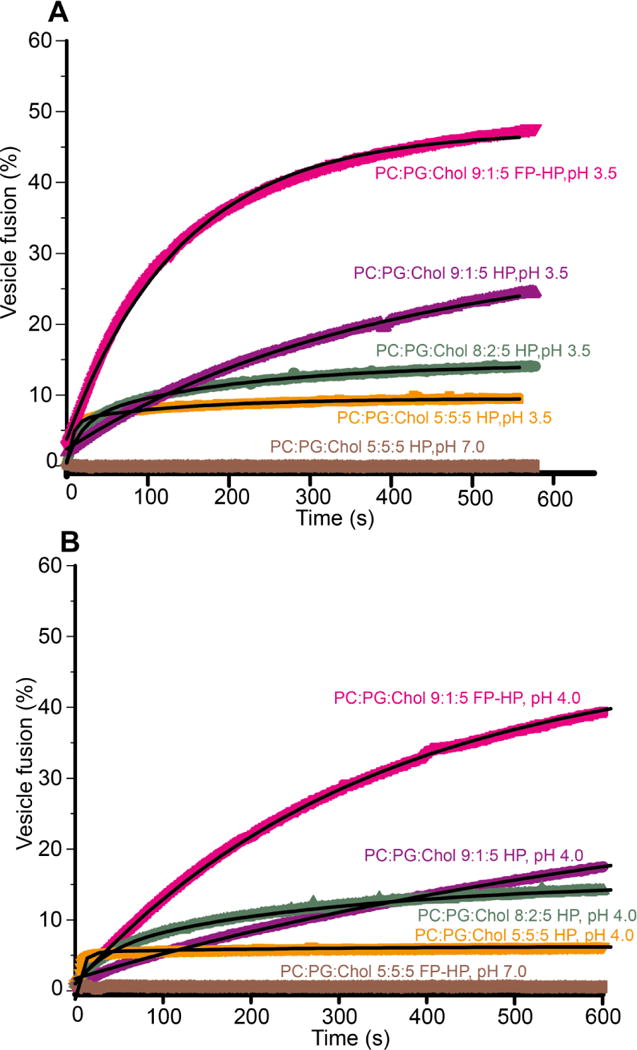

For either HP or FP-HP, the protein charge is ~ +9 at pH 3.5, ~ +7 at pH 4.0 and ~ −2 at pH 7.0. For protein:lipid mole ratio = 1:700, fusion was only observed at low pH with anionic vesicles (Fig. 2). There was negligible fusion of anionic vesicles at neutral pH and also little fusion with neutral vesicles at either low or neutral pH. These data support a fusion requirement of attractive protein/vesicle electrostatic energy which is likely needed for significant binding. For a given protein and vesicle composition, there was typically greater fusion at pH 3.5 relative to pH 4.0.

Figure 2.

Representative time-courses of protein-induced vesicle fusion for protein:total lipid mole ratio = 1:700 at pH (A) 3.5 and (B) 4.0. Chol is not considered in the total lipid quantity. Best-fits are displayed in black.

Fast and slow fusion

The time courses of fusion of anionic vesicles at low pH, M(t), were well-fitted with either the sum of a fast and slow exponential buildup:

| (2a) |

or a single slow exponential buildup:

| (2b) |

The dark lines in Fig. 2 are the best-fits of the experimental data. Use of one vs two buildups for fitting was determined by visual comparison of the best-fit and the experimental data. In practice, the fast buildup was used for |charge/lipid| ≥ 0.12. The kf and ks are the fusion rate constants with kf in the 30 – 200 ms−1 range and ks in the 1 – 9 ms−1 range. The Mf and Ms are the long-time fusion extents of the fast and slow processes, respectively. Table 1 lists the fitted rates and extents and Fig. 3 displays bar plots of the pH 3.5 values. For each set of assay conditions, data were acquired in triplicate and each data set was fitted independently. Each reported parameter uncertainty is the standard deviation among these replicate values. The uncertainty from a single replicate fitting is much smaller, typically <1% of the best-fit parameter value.

Table 1.

| Hairpin pH 3.5

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vesicle composition | Charge/lipidc | kf (ms)−1 | Mf (%) | ks (ms)−1 | Ms (%) |

| PC:PG:Chol (5:5:5) | −0.485 | 178(26) | 7.1(9) | 8(1) | 3.4(4) |

| PC:PG:Chol (8:2:5) | −0.194 | 42(5) | 6.8(5) | 4.2(5) | 7.8(1) |

| PC:PG:Chol (9:1:5) | −0.097 | – | – | 2.4(2) | 29.1(9) |

| PC:PS:Chol (5:5:5) | −0.120 | 34(4) | 3.6(7) | 4.5(4) | 12(4) |

| PC:PS:Chol (8:2:5) | −0.048 | – | – | 1.4(1) | 37(3) |

| PC:PS:Chol (9:1:5) | −0.024 | – | – | 1.4(2) | 35(4) |

| FP- Hairpin pH 3.5

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vesicle composition | Charge/lipid | kf (ms)−1 | Mf (%) | ks (ms)−1 | Ms (%) |

| PC:PG:Chol (5:5:5) | −0.485 | 216(61) | 9.6(5) | 9(3) | 4.2(8) |

| PC:PG:Chol (8:2:5) | −0.194 | 51(12) | 10(2) | 5.2(7) | 10(1) |

| PC:PG:Chol (9:1:5) | −0.097 | – | – | 8(1) | 46(5) |

| PC:PS:Chol (5:5:5) | −0.120 | 58(11) | 15(3) | 9(2) | 14(3) |

| PC:PS:Chol (8:2:5) | −0.048 | – | – | 3.7(1) | 50(1) |

| PC:PS:Chol (9:1:5) | −0.024 | – | – | 1.9(1) | 50(2) |

| Hairpin pH 4.0

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vesicle composition | Charge/lipid | kf (ms)−1 | Mf (%) | ks (ms)−1 | Ms (%) |

| PC:PG:Chol (5:5:5) | −0.495 | 135(17) | 5.3(2) | 4(2) | 1.3(4) |

| PC:PG:Chol (8:2:5) | −0.198 | 27(1) | 5(1) | 2.7(1) | 9(2) |

| PC:PG:Chol (9:1:5) | −0.099 | – | – | 1.3(3) | 20(2) |

| PC:PS:Chol (5:5:5) | −0.250 | 32(3) | 3.6(9) | 4.0(5) | 7.7(7) |

| PC:PS:Chol (8:2:5) | −0.100 | – | – | 1.4(1) | 23(6) |

| PC:PS:Chol (9:1:5) | −0.050 | – | – | 1.0(3) | 11(2) |

| FP-Hairpin pH 4.0

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vesicle composition | Charge/lipid | kf (ms)−1 | Mf (%) | ks (ms)−1 | Ms (%) |

| PC:PG:Chol (5:5:5) | −0.495 | 201(60) | 6.0(5) | 15(2) | 2.4(6) |

| PC:PG:Chol (8:2:5) | −0.198 | 27(3) | 12(1) | 4.3(8) | 10.8(5) |

| PC:PG:Chol (9:1:5) | −0.099 | – | – | 3.0(1) | 43(3) |

| PC:PS:Chol (5:5:5) | −0.250 | 25(4) | 6(1) | 3(1) | 3(1) |

| PC:PS:Chol (8:2:5) | −0.100 | – | – | 3.7(2) | 32(3) |

| PC:PS:Chol (9:1:5) | −0.050 | – | – | 1.4(3) | 29(3) |

The assay for each set of conditions was repeated in triplicate with separate fitting of each trial. Each reported parameter value and uncertainty is respectively the average and standard deviation of the three replicate fittings. For a single data set, the fitting uncertainty was typically <1% of the fitted parameter value.

Protein:total lipid mole ratio = 1:700. Chol is not included in the total lipid quantity.

Charge/lipid was calculated using a model for which: (1) PC is uncharged; and (2) and PG and PS are each characterized by an equilibrium HA ↔ H+ + A− with pKa = 2 for PG and 4 for PS [49].

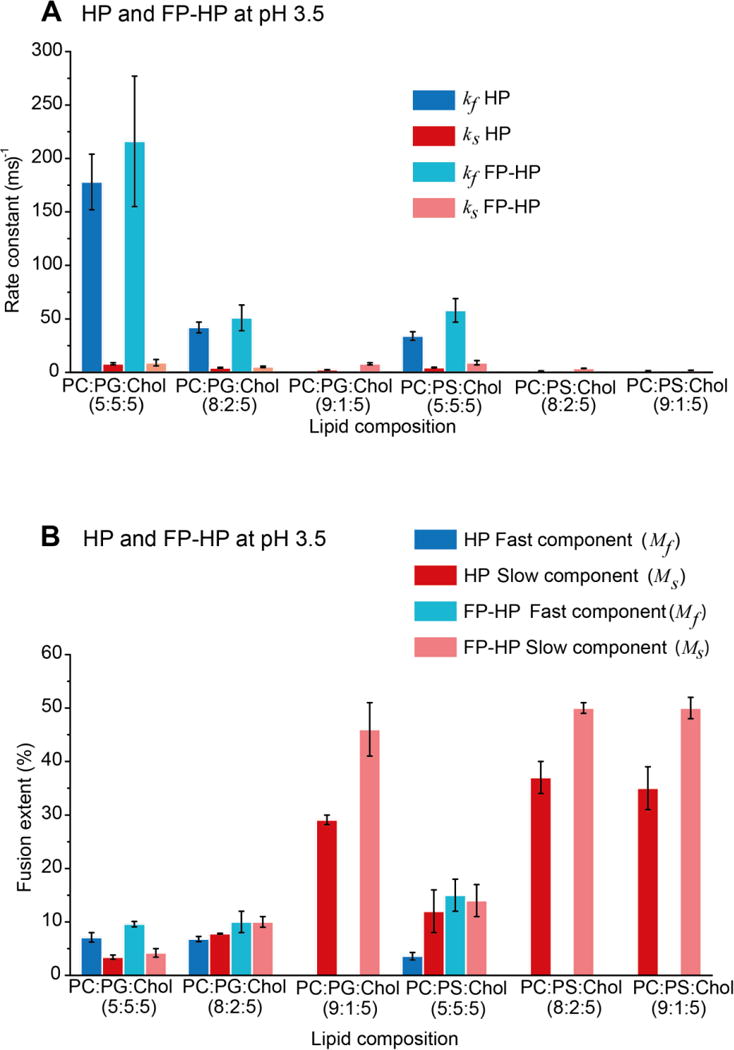

Figure 3.

(A) Buildup rate and (B) final extent best-fit parameters at pH 3.5. Each displayed parameter value and uncertainty is respectively the average and standard deviation among three replicates with separate fitting of each trial. The fitting uncertainty of a parameter for an individual trial is typically <1% of the best-fit value. For PC:PG:Chol = 5:5:5 and 8:2:5 and PC:PS:Chol = 5:5:5, the fitting model is a sum of a fast and a slow exponential-buildup while for other compositions, the model is a single slow buildup. Choice of fitting model was based on visual inspection of goodness-of-fit.

Fast rate is strongly positively correlated with lipid charge

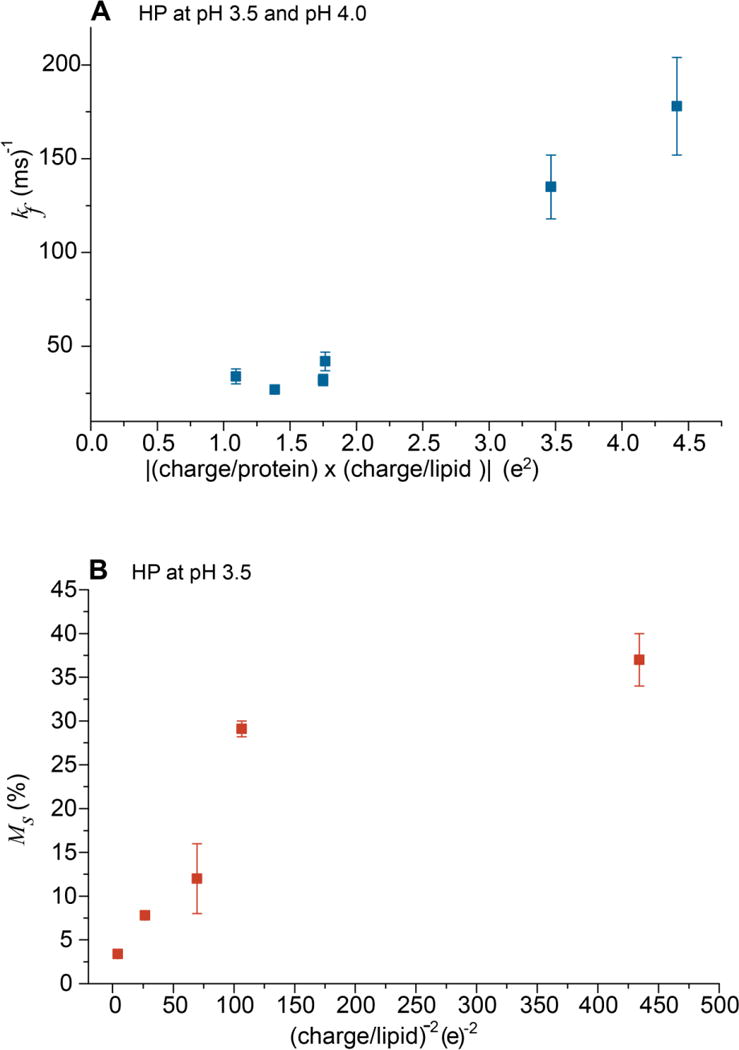

The rate of fast fusion (kf) is highly positively correlated with the average anionic lipid charge, e.g. kf ≈ 200 ms−1 for charge/lipid ≈ −0.5 and kf ≈ 30 ms−1 for charge/lipid ≈ −0.2. The fast buildup is not observed for |charge/lipid| ≤ 0.1 which suggests that the slow process becomes dominant under this condition. The correlation of kf with lipid charge is further supported by similar values of kf with vesicles with different fractions of PG or PS but similar charge/lipid, e.g. similar kf for PC:PG:Chol = 8:2:5 and PC:PS:Chol = 5:5:5. The kf value may be more specifically correlated to the magnitude of the attractive protein/vesicle electrostatic energy because for the same protein and vesicle composition, the kf at pH 3.5 (protein charge ≈ +9) is typically ~30% higher than the kf at pH 4.0 (protein charge ≈ +7). The Fig. 4A plot of kf vs |charge/protein × charge/lipid| for HP at pH 3.5 and 4.0 illustrates the positive correlation between kf and electrostatic energy. The typical long-time extent of fast buildup, Mf, is ~5% with little dependence on charge/lipid or pH, i.e. variation in protein/vesicle electrostatic energy.

Figure 4.

Plots of (A) kf vs |(charge/protein) × (charge/lipid)| and (B) Ms vs (charge/lipid)−2. The positive correlation of plot A supports the fast process resulting from release of electrostatic energy from protein/vesicle binding. Plot B supports an inverse correlation between the extent of slow fusion and inter-vesicle repulsion. Plot A displays data for HP at pH 3.5 and 4.0 and plot B displays data for HP at pH 3.5.

Slow extent is inversely dependent on lipid charge

The slow process rate constant ks is typically in the 1 – 9 ms−1 range. As with kf, for a given protein and pH, there is typically a positive correlation between ks and |charge/lipid| and an inverse correlation with pH. The dependences likely reflect a contribution from attractive protein/vesicle electrostatic energy although the ks dependence has much smaller magnitude than the corresponding kf dependence. There is also strong inverse correlation of the extent Ms with |charge/lipid|, e.g. for FP-HP induced fusion of PC:PG:Chol vesicles at pH 3.5, the decrease of charge/lipid from −0.5 to −0.1 correlates with an increase in Ms from ~5% to ~50%. The inverse dependence of Ms on |charge/lipid| is likely a consequence of the decrease in repulsive inter-vesicle electrostatic energy with decreasing charge. For example, the Fig. 4B plot of Ms vs (charge/lipid)−2 has positive slope for |charge/lipid| > 0.1. The Ms is approximately constant for |charge/lipid| < 0.1.

Higher fusion for FP-HP

For the same vesicle composition and pH, the kf or ks for FP-HP is typically 1.5 – 2 times larger than the corresponding kf or ks for HP. The Mf or Ms are similarly larger too.

β sheet FP of membrane-associated FP-Hairpin

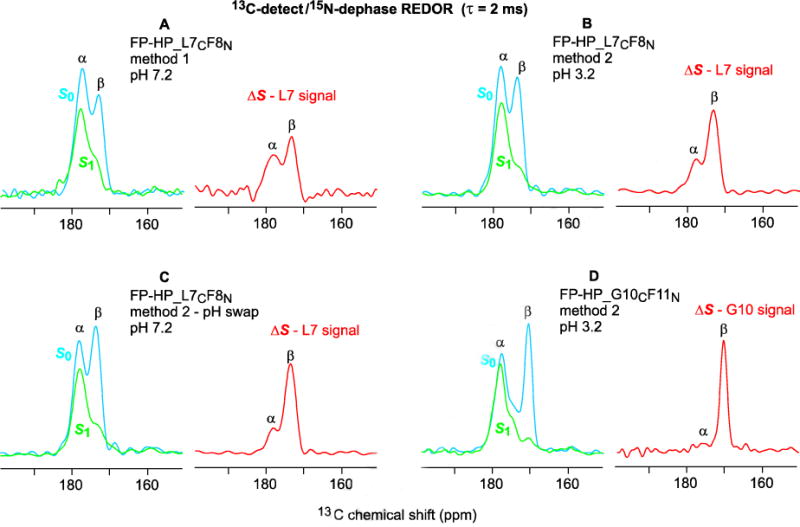

Fig. 5A displays the 13CO region of the REDOR SSNMR spectra of a sample containing PC:PG:Chol (8:2:5) and FP-HP_L7CF8N which was 13CO-labeled at L7 and 15N-labeled at F8 in the FP region. The sample was prepared by “method 1” with addition of a stock protein solution to a vesicle suspension maintained at pH 7.2. The stock protein solution was at pH 3.2 with predominant protein monomers. In the absence of vesicles, the protein aggregated at pH 7.2. The SSNMR sample was the pellet obtained after centrifugation of the protein/vesicle suspension and this pellet contained a fraction of membrane-associated protein and a fraction of non-membrane-associated protein that was aggregated.

Figure 5.

13C-detect/15N-dephase REDOR SSNMR spectra of (A–C) FP-HP_L7CF8N and (D) FP-HP_G10CF11N samples with 2 ms dephasing time. Both lab and na 13CO nuclei contribute to each S0 (blue) spectrum, the signals of lab nuclei are strongly attenuated in the S1 (green) spectrum, and the ΔS = S0 – S1 (red) spectrum is dominated by the lab 13CO signal. The α and β assignments are based on comparison with database distributions of 13CO shifts and with the corresponding lab 13CO shifts of membrane-associated FP without the NHR, loop, and CHR regions. The samples contained PC:PG:Chol in 8:2:5 mole ratio and protein:lipid mole ratio ≈ 0.02.

The S0 spectrum includes both the labeled (lab) L7 13CO signal as well as natural abundance (na) 13CO signal primarily from the helical NHR+CHR regions. Spin-counting supports a ~2:3 ratio of the lab:na integrated signal intensities. The experimental S0 spectrum shows a higher shift peak at ~178 ppm that is assigned to 13CO nuclei in α helical structure and a lower shift shoulder at ~174 ppm assigned to nuclei in antiparallel β sheet structure. Because the lab L7 13CO nucleus is directly-bonded to the lab F8 15N nucleus, the L713CO signal is highly attenuated in the S1 spectrum. The ΔS = S0 – S1 difference spectrum is consequently dominated by the lab L7 signal. The ΔS spectrum of the method 1 sample shows β and α peaks of approximately equal intensity with similar spectra obtained for replicate sample preparations. One of our goals was the qualitative assessment of the relative contributions of membrane-associated and non-membrane-associated protein to each of these peaks.

Fig. 5B displays the REDOR spectra of a FP-HP_L7CF8N sample prepared by method 2 in which protein initially solubilized at pH 3.2 was added to a vesicle suspension also at pH 3.2. Relative to the ΔS spectrum of the method 1 sample, the ΔS spectrum of the method 2 sample has a more dominant β peak. The centrifugation pellet was fully membrane-associated protein with minimal aggregated protein as evidenced by: (1) no pellet from the method 2 protocol in the absence of vesicles; and (2) immediate turbidity with addition of protein consistent with rapid protein binding and induction of vesicle fusion at pH 3.2 (Fig. 2A). The A280 of the centrifugation supernatant was used to calculate the quantities of soluble and membrane-bound protein. The maximum protein:lipid mole ratio of the pellet was ~0.02 and consistent among replicate samples. The lab β signal is dominant after the sample pH was swapped to 7.2 (Fig. 5C) and after reverse-swapping to pH 3.2 (not shown). These similar β spectra obtained for the same sample initially at pH 3.2, then at pH 7.2, and again at pH 3.2 are consistent with retention of membrane-binding for the protein at pH 7.2 even though there is electrostatic repulsion between the protein and membrane at this higher pH. Membrane binding could be retained through the attractive and pH-independent hydrophobic interaction between the FP region and the membrane. The major lab β signal is observed in replicate samples and for other lab sites of method 2 samples, e.g. G10 of a sample with FP-HP_G10CF11N (Fig. 5D). The ΔS spectrum of FP-HP_L7CF8N precipitated at pH 7.2 in the absence of vesicles shows lab L7 β and α peaks in ~1:1 ratio (not shown). This result and the major lab β peak of method 2 samples support a dominant contribution to the lab α peak of the method 1 samples from non-membrane-associated protein aggregates.

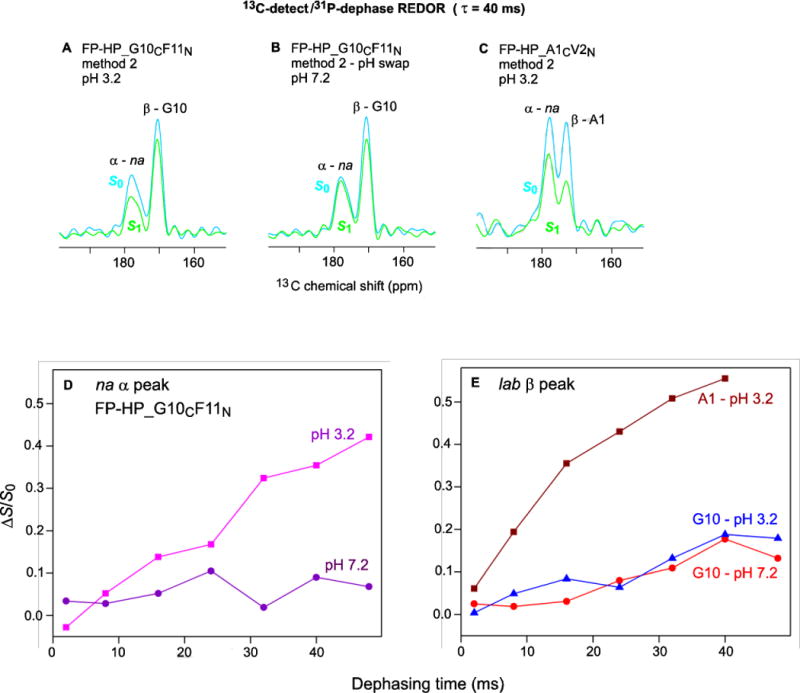

Membrane proximities of the FP and Hairpin regions

Fig. 6A–C display 13CO REDOR spectra for 40 ms dephasing time of fully-membrane-associated FP-HP with dephasing by the 31P nuclei of the lipid headgroups. The samples include FP-HP_G10CF11N at (A) pH 3.2 and (B) pH 7.2 and (C) FP-HP_A1CV2N at pH 3.2. Plots of (ΔS/S0) vs τ are displayed for the (D) na α 13CO signal of the G10CF11N samples at pH 3.2 and 7.2 and (E) lab G10 β signals at pH 3.2 and pH 7.2 as well as the lab β A1 signal at pH 3.2. Some of the (ΔS/S0) buildups are semi-quantitatively analyzed using a model of isolated 13CO-31P spin pairs which all have the same internuclear distance r. For this model, there is a general expression for (ΔS/S0) as a function of function r and τ which is the basis of the specific equation to calculate the 13CO-31P distance [31]:

| (3) |

The τ0.3 corresponds to (ΔS/S0) = 0.3 which is typically a high-slope region of the (ΔS/S0) vs τ buildup.

Figure 6.

13C-detect/31P-dephase REDOR SSNMR spectra of (A,B) FP-HP_G10CF11N and (C) FP-HP_A1CV2N samples with 40 ms dephasing time. Plots of (ΔS/S0) vs dephasing time for (D) na α signals and (E) lab β signals. Each (ΔS/S0) value was calculated from S0 and S1 13CO intensities integrated over a 3–4 ppm shift interval. The typical uncertainty in a (ΔS/S0) value was 0.01 as calculated from the standard deviation of spectral noise values integrated over comparable interval width.

The na α signal is dominated by 13CO nuclei of the Hairpin (NHR+CHR) region (Fig. 1) because this region is highly helical whereas for membrane-bound protein, the FP region has predominant β structure. This na α assignment is also evidenced by similar (ΔS/S0)α for FP-HP samples labeled at different FP residues, e.g. A1 or G10. At pH 3.2, there is clear buildup of (ΔS/S0)α with τ with τ0.3 ≈ 0.03 s and corresponding r ≈ 8–9 Å. At pH 7.2, in some contrast, the (ΔS/S0)α < 0.1 for all τ which evidences r >12 Å for most Hairpin 13CO nuclei. The nearer (pH 3.2) and farther (pH 7.2) proximities of Hairpin to the negatively-charged membrane respectively correlate with the positive and negative charges of Hairpin region and the consequent attractive and repulsive electrostatic energies between this region and the anionic membrane. “Reverse-swap” samples whose pH had been cycled from 3.2 to 7.2 and back to 3.2 had (ΔS/S0)α comparable to the large values of the original pH 3.2 samples and different than the smaller values of the swapped pH 7.2 samples. The reversibility of the pH-dependent variation in Hairpin/membrane proximity supports fully membrane-bound protein in method 2 samples at both pH 3.2 and 7.2 and contrasts with the mixture of membrane-bound protein and non-membrane-bound protein aggregates detected in the method 1 samples at pH 7.2.

The α signal is dominated by lab 13CO nuclei in the oligomeric antiparallel β sheet structure of the FP. There is rapid A1 (ΔS/S0)β buildup at pH 3.2 with τ0.3 ≈ 0.01 s and corresponding r ≈ 5–6 Å. This value of r is consistent with van der Waals contact between the A1 residue and the membrane for many of the FP-HP molecules. This contact is likely due to electrostatic attraction between the A1 –NH3+ and the negatively charged membrane as well as overall FP binding to the membrane through hydrophobic interaction. Relative to A1 at pH 3.2, there is smaller G10 (ΔS/S0)β buildup at both pH 3.2 and 7.2. These smaller buildups evidence larger r for G10 and may reflect insertion of the hydrophobic 7LFLGFL segment of the FP region into the membrane hydrocarbon core.

Discussion

Fast and slow fusion processes

One important result of the present study was detection of fast ~100 ms−1 and slow ~ 5 ms−1 components of vesicle fusion. The rate constant of the fast component kf is strongly positive correlated with |charge/lipid| and therefore the magnitude of attractive protein/vesicle electrostatic energy (Fig. 4A). The fusion extent Mf is approximately independent of this energy. The magnitude of this energy is 60 kJ/(mole protein) as calculated for: (1) vesicles with 20% negatively charged lipid; (2) monomer protein with +7 charge; (3) bound protein separated by 20 Å from 50 lipid phosphate groups; and (4) aqueous media with dielectric constant of 80. Fast fusion is attributed to deposition of this energy in the membrane and the consequent local membrane perturbation. After dissipation of this energy, fusion may arrested by intervesicle repulsion whose magnitude also increases with |charge/lipid|.

The kf’s are ~1% of the rates of protein/vesicle (kpv) and vesicle/vesicle (kvv) collisions [32]. Protein/vesicle electrostatics are attractive and orientation-independent, so a protein likely binds to the vesicle after a single collision. For protein:lipid = 1:700, each 100 nm diameter vesicle has ~80 bound proteins that cover ~10% of the vesicle surface. The ratio for kf /kvv of ~0.01 may reflect the (0.1)2 fraction of inter-vesicle collisions with contact between protein regions on both vesicles. Other collision geometries may not lead to fusion because of repulsion between the negatively-charged vesicle surfaces.

Relative to the kf’s, the ks’s show weaker dependence on protein and vesicle charges. The positive ks dependence likely reflects a contribution from attractive protein/vesicle electrostatic energy. The Ms’s have strong inverse correlation on |charge/lipid| in the 0.1 to 0.5 range, with no further increases for |charge/lipid| lower than 0.1. We assign the slow process to fusion after dissipation of the attractive protein/vesicle electrostatic energy with higher extents at smaller |charge/lipid| attributed to reduced intervesicle repulsion (Fig. 4B). The slow process occurs on the ~200 s timescale and reflects rare fusion events that occur after hundreds of vesicle/vesicle collisions. The probability of a fusogenic collision likely increases with decreased inter-vesicle repulsive energy. The approximately constant Ms for |charge/lipid| ≤ 0.1 may reflect competing effects of smaller intervesicle repulsion and smaller protein/vesicle attraction that results in fewer bound proteins. This latter effect is consistent with negligible fusion of electrically neutral PC:Chol vesicles at either low or neutral pH.

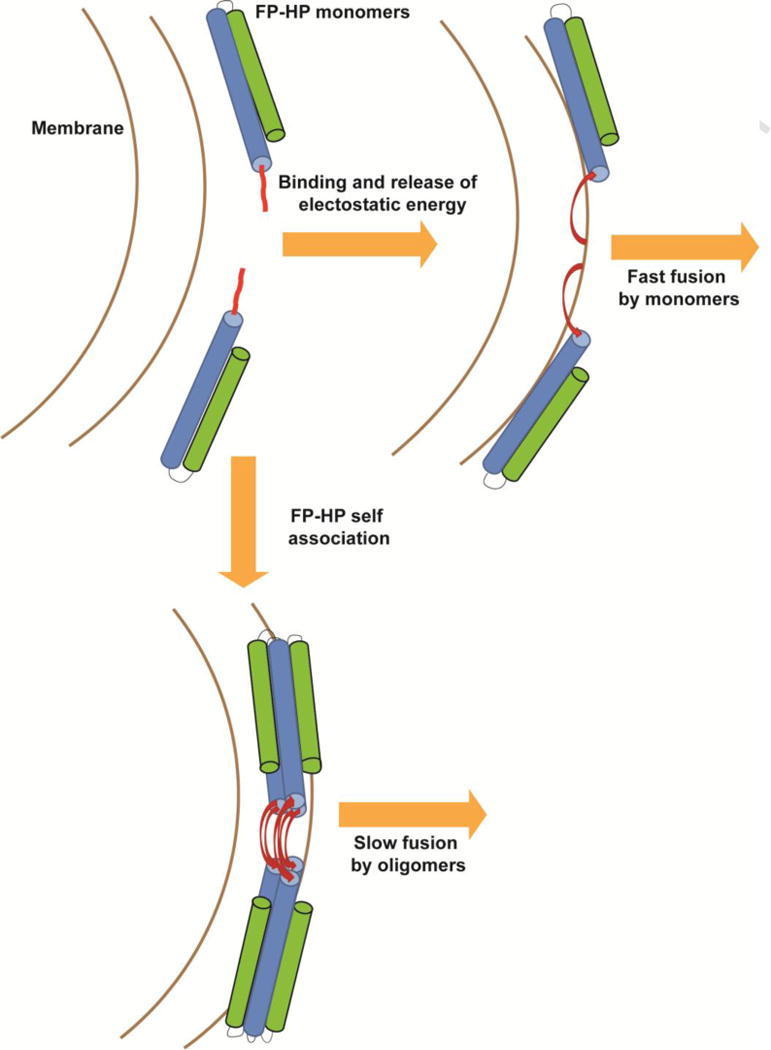

Fig. 7 presents a qualitative model of gp41 ectodomain-induced vesicle fusion at low pH. The fast process is attributed to bound protein monomers that reflect the predominant protein state in aqueous solution. The slow process is attributed to membrane-bound protein oligomers which are the likely equilibrium structural state and which may form through protein diffusion on the membrane surface on the ~200 s time scale of the slow process. For some conditions, the displayed hexamer ≡ two trimer state is the predominant oligomerization state for large ectodomain constructs such as HP [7,8].

Figure 7.

Qualitative model of FP-HP-induced fusion of anionic vesicles with FP-HP color coding matched to Fig. 1. Monomers from solution bind to the vesicles with release of electrostatic energy that results in fast fusion. The bound monomers also diffuse on the vesicle surface and self-associate as small oligomers with formation of an intermolecular antiparallel FP β sheet which is associated with slow fusion [50].

Membrane-associated β FP

Fully-membrane-associated FP-HP was prepared at low pH because the protein was predominantly monomeric in the solution and also bound tightly to anionic membranes. Membrane-binding was retained during a swap to neutral pH and a reverse-swap back to low pH. Protein 13CO-to-lipid 31P REDOR SSNMR spectra showed that the helical NHR and CHR regions of FP-HP are closer to the membrane surface at low pH than at neutral pH which correlates with the respective attractive and repulsive protein/membrane electrostatic energy. Retention of membrane binding at neutral pH is likely through the hydrophobic FP region. Inclusion of this region in FP-HP also contributes to more rapid and extensive fusion relative to HP. At either low or neutral pH, the major population of membrane-associated FP-HP molecules have β FP structure. Previous SSNMR showed this was an intermolecular antiparallel β sheet, likely an equilibrium structure as the SSNMR is done after ~1 day of sample preparation [20,33]. The oligomer with β FP’s is proposed as the catalytic structure of the slow fusion process. The FP may locally perturb the surrounding bilayer structure of the lipids (at equilibrium) so that there is smaller activation energy to the fusion transition state in which lipid structures are also disordered relative to an unperturbed bilayer [34–37].

The β FP structure of FP-HP in membranes correlates with previous observations of β structure of FP in membranes (without the C-terminal Hairpin) [16,26,33,38]. The β FP may therefore be an autonomous structure in membranes so that FP alone and the FP region of large segments of gp41 like FP-HP may have similar structures and locations in the membrane [39,40]. For membranes lacking Chol, there is also a population of FP molecules with predominant α helical structure and a positive correlation between membrane Chol content and β FP population [41,42]. We do not yet know whether this correlation also holds for FP-HP as FP-HP samples have only been prepared with lipid:Chol mole ratio = 2:1. We don’t yet have structural data for the FP in the membrane-associated monomer which is probably a non-equilibrium state (Fig. 7).

The FP β oligomer in the membrane contrasts with the α monomer commonly observed in detergent [43,44]. The α monomer in detergent is probably due to: (1) entropically-driven partitioning of single proteins into separated micelles with ~100 detergent molecules; and (2) formation of α structure in the micelle interior because this structure maximizes intra-protein backbone hydrogen bonding in this low dielectric environment with low water content. The β oligomer in membranes is probably due to: (1) ~100,000 lipid molecules per vesicle with even larger numbers after fusion; (2) tens to thousands of protein molecules per vesicle; and (3) formation of intermolecular β structure that maximizes inter-protein hydrogen bonding and increases entropy because of the distribution of intermolecular antiparallel registries and the distribution of FP locations within the membrane hydrocarbon core.

α FP of aggregated FP-HP

Non-membrane-associated FP-HP aggregates at neutral pH have ~50% population of FP-HP molecules with α FP structure. Having α rather than β FP structure suggests intermolecular contacts via protein regions other than the hydrophobic FP. These types of contacts are also consistent with the observed aggregation at neutral pH of HP which lacks the FP.

Slow vesicle fusion as a model for HIV hemifusion

The lipid mixing assay of ectodomain-induced vesicle fusion correlates with the initial hemifusion (joining) of viral and cell membranes. At low pH, the protein is monomeric in solution and binding to anionic membranes is favored by attractive electrostatics. At neutral pH, the protein aggregates in solution and binding is inhibited by repulsive electrostatics. HIV/cell fusion probably occurs at neutral pH with anionic membranes but is different from vesicle fusion at neutral pH because viral protein aggregation is disfavored and viral protein binding to the cell membrane is favored. These properties are the result of: (1) viral gp41 being an integral membrane protein; and (2) spatial confinement of the viral gp41 ectodomain to the region between viral and host cell membranes because of initial binding between the extraviral gp120 protein and cell membrane proteins. Viral fusion is therefore better modeled by ectodomain-induced vesicle fusion at low pH because there is minimal protein aggregation in solution and high membrane-binding.

In addition, virus/cell hemifusion is probably better modeled by the slow than the fast component of vesicle fusion. The fast process is highly positively correlated with the attractive protein/membrane electrostatic energy and this energy is likely small or even repulsive for viral fusion at neutral pH. In addition, the |charge/lipid| is ~0.15 for HIV and ~0.07 for the host cell membrane [21]. For this regime, there is maximal slow and minimal fast vesicle fusion. To our knowledge, the viral hemifusion rate has not been measured but the typical overall timescale for viral fusion is ~30 min [45]. Relative to the fast timescale of ~0.1 min, the slow timescale of ~3 min also seems more reasonable for viral fusion. Correlation of slow vesicle fusion with viral fusion suggests that the active state of the viral gp41 ectodomain may be oligomeric with membrane-inserted FP’s in an intermolecular antiparallel β sheet (Fig. 7). This is consistent with earlier data supporting the significance of FP oligomers in viral fusion and infection [11,12,32].

Although the fusion of anionic vesicles requires low pH for attractive protein/vesicle electrostatic energy and quantitative binding, viral fusion likely occurs near neutral pH. This holds for either direct fusion between the viral and plasma membranes or for endocytosis with subsequent fusion between the viral and endosomal membranes [46,47]. There is no evidence yet for acidification of HIV-containing endosomes.

The whole gp41 protein including TM and endodomain is likely minimally trimeric during all steps of viral fusion. The initial gp160 complex contains three gp41 and three gp120 subunits with the three NHR helices forming a bundle at the center of the complex [48]. After binding of the three gp120’s to host cell receptors, the gp120’s move away from the gp41’s. The NHR bundle may dissociate with subsequent formation of three NHR/CHR monomer ectodomain hairpins. These monomer hairpins are hyperthermostable with Tm ≈ 110 °C [14,17]. Evidence for the ectodomain monomer as an intermediate in viral fusion includes fusion inhibitors that could bind to the ectodomain hairpin monomer but not to the final trimer of hairpins (six-helix bundle) state. The inhibitors would reduce the oligomer populations of trimer and hexamer and consequently the intermolecular antiparallel FP β sheet [10,45]. This interpretation of the peptide inhibition supports the role of this sheet for hemifusion and viral infection.

Highlights.

Fusion peptide of membrane-associated HIV gp41 ectodomain has β sheet conformation

Positively-charged gp41 ectodomain induces fusion of negatively-charged vesicles

Fusion includes fast (~100 ms−1) and slow (~5 ms−1) processes

Rate of fast-process positively correlates with magnitude of lipid charge

Extent of slow-process inversely correlates with magnitude of lipid charge

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by NIH awards R01AI047153 to D.P.W. and F32AI080136 to K.S.

Abbreviations

- AL

anionic lipid

- Chol

cholesterol

- CHR

C-heptad repeat

- FP

fusion peptide

- FP-HP

FP-Hairpin protein

- Hairpin

NHR+CHR

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HP

Hairpin protein

- lab

labeled

- MAS

magic angle spinning

- na

natural abundance

- NHR

N-heptad repeat

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PG

phosphatidylglycerol

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- REDOR

rotational-echo double-resonance

- SSNMR

solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance

- TM

transmembrane

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.White JM, Delos SE, Brecher M, Schornberg K. Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: Multiple variations on a common theme. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:189–219. doi: 10.1080/10409230802058320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, Sapiro G, Subramaniam S. Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature. 2008;455:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature07159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caffrey M, Cai M, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Covell DG, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Three-dimensional solution structure of the 44 kDa ectodomain of SIV gp41. EMBO J. 1998;17:4572–4584. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang ZN, Mueser TC, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Hyde CC. The crystal structure of the SIV gp41 ectodomain at 1.47 A resolution. J Struct Biol. 1999;126:131–144. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buzon V, Natrajan G, Schibli D, Campelo F, Kozlov MM, Weissenhorn W. Crystal structure of HIV-1 gp41 including both fusion peptide and membrane proximal external regions. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000880. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caffrey M, Kaufman J, Stahl S, Wingfield P, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Monomer-trimer equilibrium of the ectodomain of SIV gp41: Insight into the mechanism of peptide inhibition of HIV infection. Prot Sci. 1999;8:1904–1907. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.9.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee K, Weliky DP. Submitted [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao GF, Wieczorek L, Peachman KK, Polonis VR, Alving CR, Rao M, Rao VB. Designing a soluble near full-length HIV-1 gp41 trimer. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:234–246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.424432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lakomek NA, Kaufman JD, Stahl SJ, Louis JM, Grishaev A, Wingfield PT, Bax A. Internal dynamics of the homotrimeric HIV-1 viral coat protein gp41 on multiple time scales. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:3911–3915. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markosyan RM, Cohen FS, Melikyan GB. HIV-1 envelope proteins complete their folding into six-helix bundles immediately after fusion pore formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:926–938. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freed EO, Delwart EL, Buchschacher GL, Jr, Panganiban AT. A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 dominantly interferes with fusion and infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1992;89:70–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magnus C, Rusert P, Bonhoeffer S, Trkola A, Regoes RR. Estimating the stoichiometry of Human Immunodeficiency Virus entry. J Virol. 2009;83:1523–1531. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01764-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sackett K, Nethercott MJ, Shai Y, Weliky DP. Hairpin folding of HIV gp41 abrogates lipid mixing function at physiologic pH and inhibits lipid mixing by exposed gp41 constructs. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2714–2722. doi: 10.1021/bi8019492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sackett K, Nethercott MJ, Epand RF, Epand RM, Kindra DR, Shai Y, Weliky DP. Comparative analysis of membrane-associated fusion peptide secondary structure and lipid mixing function of HIV gp41 constructs that model the early pre-hairpin intermediate and final hairpin conformations. J Mol Biol. 2010;397:301–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sackett K, TerBush A, Weliky DP. HIV gp41 six-helix bundle constructs induce rapid vesicle fusion at pH 3.5 and little fusion at pH 7.0: understanding pH dependence of protein aggregation, membrane binding, and electrostatics, and implications for HIV-host cell fusion. Eur Biophys J. 2011;40:489–502. doi: 10.1007/s00249-010-0662-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira FB, Goni FM, Muga A, Nieva JL. Permeabilization and fusion of uncharged lipid vesicles induced by the HIV-1 fusion peptide adopting an extended conformation: dose and sequence effects. Biophys J. 1997;73:1977–1986. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lev N, Fridmann-Sirkis Y, Blank L, Bitler A, Epand RF, Epand RM, Shai Y. Conformational stability and membrane interaction of the full-length ectodomain of HIV-1 gp41: Implication for mode of action. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3166–3175. doi: 10.1021/bi802243j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng SF, Chien MP, Lin CH, Chang CC, Lin CH, Liu YT, Chang DK. The fusion peptide domain is the primary membrane-inserted region and enhances membrane interaction of the ectodomain of HIV-1 gp41. Mol Membr Biol. 2010;27:31–44. doi: 10.3109/09687680903333847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caffrey M, Braddock DT, Louis JM, Abu-Asab MA, Kingma D, Liotta L, Tsokos M, Tresser N, Pannell LK, Watts N, Steven AC, Simon MN, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Clore GM. Biophysical characterization of gp41 aggregates suggests a model for the molecular mechanism of HIV-associated neurological damage and dementia. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19877–19882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sackett K, Nethercott MJ, Zheng ZX, Weliky DP. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy of the HIV gp41 membrane fusion protein supports intermolecular antiparallel beta sheet fusion peptide structure in the final six-helix bundle state. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:1077–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brugger B, Glass B, Haberkant P, Leibrecht I, Wieland FT, Krasslich HG. The HIV lipidome: A raft with an unusual composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2006;103:2641–2646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gullion T, Schaefer J. Rotational-echo double-resonance NMR. J Magn Reson. 1989;81:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fowler DJ, Weis RM, Thompson LK. Kinase-active signaling complexes of bacterial chemoreceptors do not contain proposed receptor-receptor contacts observed in crystal structures. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1425–1434. doi: 10.1021/bi901565k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Parkanzky PD, Bodner ML, Duskin CG, Weliky DP. Application of REDOR subtraction for filtered MAS observation of labeled backbone carbons of membrane-bound fusion peptides. J Magn Reson. 2002;159:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang HY, Neal S, Wishart DS. RefDB: A database of uniformly referenced protein chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR. 2003;25:173–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1022836027055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiang W, Bodner ML, Weliky DP. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy of human immunodeficiency virus fusion peptides associated with host-cell-like membranes: 2D correlation spectra and distance measurements support a fully extended conformation and models for specific antiparallel strand registries. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5459–5471. doi: 10.1021/ja077302m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toke O, Maloy WL, Kim SJ, Blazyk J, Schaefer J. Secondary structure and lipid contact of a peptide antibiotic in phospholipid bilayers by REDOR. Biophys J. 2004;87:662–674. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.032706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng Z, Yang R, Bodner ML, Weliky DP. Conformational flexibility and strand arrangements of the membrane-associated HIV fusion peptide trimer probed by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12960–12975. doi: 10.1021/bi0615902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gabrys CM, Qiang W, Sun Y, Xie L, Schmick SD, Weliky DP. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance measurements of HIV fusion peptide 13CO to lipid 31P proximities support similar partially inserted membrane locations of the α helical and β sheet peptide structures. J Phys Chem A. 2013;117:9848–9859. doi: 10.1021/jp312845w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morcombe CR, Zilm KW. Chemical shift referencing in MAS solid state NMR. J Magn Reson. 2003;162:479–486. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gullion T. Introduction to rotational-echo, double-resonance NMR. Concepts Magn Reson. 1998;10:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang R, Prorok M, Castellino FJ, Weliky DP. A trimeric HIV-1 fusion peptide construct which does not self-associate in aqueous solution and which has 15-fold higher membrane fusion rate. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14722–14723. doi: 10.1021/ja045612o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang J, Prorok M, Castellino FJ, Weliky DP. Oligomeric β-structure of the membrane-bound HIV-1 fusion peptide formed from soluble monomers. Biophys J. 2004;87:1951–1963. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.028530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabrys CM, Yang R, Wasniewski CM, Yang J, Canlas CG, Qiang W, Sun Y, Weliky DP. Nuclear magnetic resonance evidence for retention of a lamellar membrane phase with curvature in the presence of large quantities of the HIV fusion peptide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tristram-Nagle S, Chan R, Kooijman E, Uppamoochikkal P, Qiang W, Weliky DP, Nagle JF. HIV fusion peptide penetrates, disorders, and softens T-cell membrane mimics. J Mol Biol. 2010;402:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao HW, Hong M. Membrane-dependent conformation, dynamics, and lipid Interactions of the fusion peptide of the paramyxovirus PIV5 from solid-state NMR. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:563–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai AL, Freed JH. HIV gp41 fusion peptide increases membrane ordering in a cholesterol-dependent fashion. Biophys J. 2014;106:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pritsker M, Rucker J, Hoffman TL, Doms RW, Shai Y. Effect of nonpolar substitutions of the conserved Phe11 in the fusion peptide of HIV-1 gp41 on its function, structure, and organization in membranes. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11359–11371. doi: 10.1021/bi990232e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Epand RM. Fusion peptides and the mechanism of viral fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1614:116–121. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nieva JL, Agirre A. Are fusion peptides a good model to study viral cell fusion? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1614:104–115. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qiang W, Weliky DP. HIV fusion peptide and its cross-linked oligomers: efficient syntheses, significance of the trimer in fusion activity, correlation of β strand conformation with membrane cholesterol, and proximity to lipid headgroups. Biochemistry. 2009;48:289–301. doi: 10.1021/bi8015668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai AL, Moorthy AE, Li YL, Tamm LK. Fusion activity of HIV gp41 fusion domain is related to its secondary structure and depth of membrane insertion in a cholesterol-dependent fashion. J Mol Biol. 2012;418:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaroniec CP, Kaufman JD, Stahl SJ, Viard M, Blumenthal R, Wingfield PT, Bax A. Structure and dynamics of micelle-associated human immunodeficiency virus gp41 fusion domain. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16167–16180. doi: 10.1021/bi051672a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gabrys CM, Weliky DP. Chemical shift assignment and structural plasticity of a HIV fusion peptide derivative in dodecylphosphocholine micelles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:3225–3234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gallo SA, Finnegan CM, Viard M, Raviv Y, Dimitrov A, Rawat SS, Puri A, Durell S, Blumenthal R. The HIV Env-mediated fusion reaction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1614:36–50. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grewe C, Beck A, Gelderblom HR. HIV: early virus-cell interactions. J AIDS. 1990;3:965–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melikyan GB. HIV entry: a game of hide-and-fuse? Curr Opin Virol. 2014;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Julien JP, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumukis D, Deller MC, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Ward AB, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of a soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013;342:1477–1483. doi: 10.1126/science.1245625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsui FC, Ojcius DM, Hubbell WL. The intrinsic pKa values for phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine in phosphatidylcholine host bilayers. Biophys J. 1986;49:459–468. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(86)83655-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ott M, Shai Y, Haran G. Single-particle tracking reveals switching of the HIV fusion peptide between two diffusive modes in membranes. J Phys Chem B. 2014;117:13308–13321. doi: 10.1021/jp4039418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]