Abstract

Background

The initiation and regulation of pulmonary fibrosis are not well understood. IL-33, an important cytokine for respiratory diseases, is overexpressed in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Objectives

We aimed to determine the effects and mechanism of IL-33 on the development and severity of pulmonary fibrosis in murine bleomycin-induced fibrosis.

Methods

Lung fibrosis was induced by bleomycin in wild-type or Il33r (St2)−/− C57BL/6 mice treated with the recombinant mature form of IL-33 or anti–IL-33 antibody or transferred with type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s). The development and severity of fibrosis was evaluated based on lung histology, collagen levels, and lavage cytology. Cytokine and chemokine levels were quantified by using quantitative PCR, ELISA, and cytometry.

Results

IL-33 is constitutively expressed in lung epithelial cells but is induced in macrophages by bleomycin. Bleomycin enhanced the production of the mature but reduced full-length form of IL-33 in lung tissue. ST2 deficiency, anti–IL-33 antibody treatment, or alveolar macrophage depletion attenuated and exogenous IL-33 or adoptive transfer of ILC2s enhanced bleomycin-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis. These pathologic changes were accompanied, respectively, by reduced or increased IL-33, IL-13, TGF-β1, and inflammatory chemokine production in the lung. Furthermore, IL-33 polarized M2 macrophages to produce IL-13 and TGF-β1 and induced the expansion of ILC2s to produce IL-13 in vitro and in vivo.

Conclusions

IL-33 is a novel profibrogenic cytokine that signals through ST2 to promote the initiation and progression of pulmonary fibrosis by recruiting and directing inflammatory cell function and enhancing profibrogenic cytokine production in an ST2- and macrophage-dependent manner.

Key words: IL-33, lung fibrosis, alternatively activated macrophages, type 2 innate lymphoid cells

Abbreviations used: APC, Allophycocyanin; Arg1, Arginase 1; BAL, Bronchoalveolar lavage; BMDM, Bone marrow–derived macrophage; CT, Computed tomography; FITC, Fluorescein isothiocyanate; flIL-33, Full-length IL-33; ICOS, Inducible costimulator; ILC2, Type 2 innate lymphoid cell; IPF, Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; M1 macrophage, Classically activated macrophage; M2 macrophage, Alternatively activated macrophage; mIL-33, Mature IL-33; Nos2, Inducible nitric oxide synthase 2 gene; PE, Phycoerythrin; qPCR, Quantitative PCR; WT, Wild-type

Bleomycin is an important cancer chemotherapeutic agent. However, its cytotoxic activity associated with DNA strand cissation and reactive oxygen species induction can cause severe side effects, including pulmonary fibrosis. This can be recapitulated in experimental models designed to investigate the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis and some aspects of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF),1, 2, 3 a devastating treatment-refractory interstitial lung disease of unknown origin.4, 5 A better understanding of the fibrotic process might lead to novel therapeutic approaches for this unmet clinical need. Bleomycin-induced fibrosis in susceptible C57BL/6 mice provides a reliable model to study the underlying mechanisms of fibrosis.1

Although the pathogenic mechanisms of bleomycin-induced fibrosis and IPF are not fully understood, both conditions are characterized by alveolar epithelial injury, accumulation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, and deposition of collagenous extracellular matrix in the lung, which together compromise functional gas exchange.1, 2, 4, 5 Lung histology and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) show inflammatory cytology, including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages, which are thought to contribute to fibrogenesis.1, 2, 4, 5 Macrophages can be polarized into 2 phenotypes: classically activated macrophages (M1 macrophages), which are activated by IFN-γ and LPS, or alternatively activated macrophages (M2 macrophages), which are activated by IL-4 and IL-13.6, 7 M1 macrophages express inducible nitric oxide synthase and proinflammatory cytokines and protect against infection, whereas M2 macrophages express arginase 1 and TGF-β1 and are critically involved in tissue repair and fibrosis.6, 7

The profibrogenic cytokines TGF-β1 and IL-13 are essential for the development of lung fibrosis by promoting myofibroblast differentiation and stimulating production of extracellular matrix proteins, primarily collagen,4, 5 and thus are important potential therapeutic targets in fibrosis. Similar strategies can be applied to other mediators, including cytokines of the IL-1 family, among which IL-1 and IL-18 have a role in clinical and experimental lung fibrosis.8 IL-33 is a new member of the IL-1 family and is overexpressed in the lungs of patients with IPF.9

IL-33 is a dual-function cytokine: the full-length IL-33 (flIL-33) form serves as an intracellular gene regulator in the nucleus, and the mature IL-33 (mIL-33) form serves as an extracellular cytokine after release when cells sense inflammatory signals or undergo necrosis.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Once released, flIL-33 can be processed by neutrophil-derived proteases into mIL-33.13 Although both flIL-33 and mIL-33 are able to bind to and signal through their receptor, ST2, mIL-33 has a 10-fold higher affinity and bioactivity than flIL-33.13 ST2 is expressed on most innate cells, including macrophages and the newly identified type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), and IL-33 plays a direct role in the function of these cells.16, 17, 18, 19 mIL-33 mainly elicits a type 2 immune response and is closely associated with allergic and parasitic diseases.11, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 It has recently been reported that nuclear flIL-33 potentiates bleomycin-induced lung injury in an undefined but ST2-independent manner.9 The expression of IL-33 mRNA is increased in IPF lung tissue9; however, the role of mIL-33 as a cytokine in the fibrotic process is unknown.

We have investigated the effect and mechanism of mIL-33 in the initiation and exacerbation of bleomycin-induced fibrosis in mice. We report here that mIL-33, through ST2, strongly enhances bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, mainly by promoting inflammatory cell infiltration and function, including polarization of M2 macrophages and ILC2s, and enhancing their IL-13 and TGF-β1 production.

Methods

Experimental details are provided in the Methods section in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

Results

Bleomycin-induced fibrosis is impaired in St2−/− mice

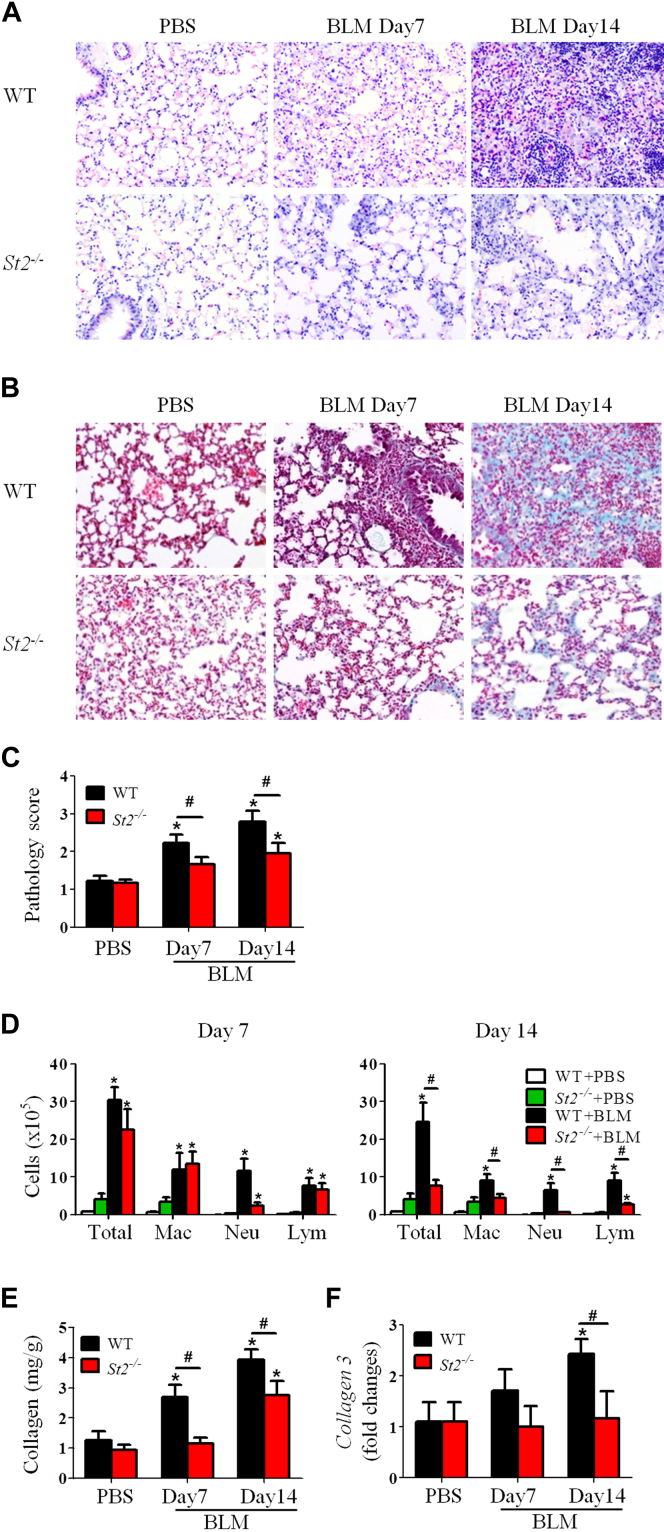

Groups of wild-type (WT) and St2−/− C57BL/6 mice were given bleomycin or PBS intranasally on day 0. The mice were killed on day 7 or 14 to investigate the role of the cytokine IL-33 in the development of bleomycin-induced fibrosis. WT mice that received bleomycin had progressive lung inflammation (Fig 1, A) and fibrosis (Fig 1, B) from day 7 compared with PBS control mice. This bleomycin-induced inflammatory and fibrotic response was demonstrated by enhanced inflammatory cell infiltration and collagen deposition in the lung and quantified by using histologic inflammatory and fibrosis scores (Fig 1, C). The pathologic changes observed in WT mice given bleomycin were significantly reduced in St2−/− mice given bleomycin (Fig 1, A-C).

Fig 1.

St2−/− mice have attenuated bleomycin (BLM)–induced fibrosis. Lung hematoxylin and eosin staining (A), collagen staining (B), lung pathology score (C), total and differential lung lavage cytology (D), lung tissue collagen content (E), and lung tissue collagen 3 mRNA expression (F) are shown. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 5-7 mice per group per experiment). *P < .05 compared with PBS control and #P < .05 compared with WT values. Data are representative of 3 experiments. Lym, Lymphocytes; Mac, macrophages; Neu, neutrophils.

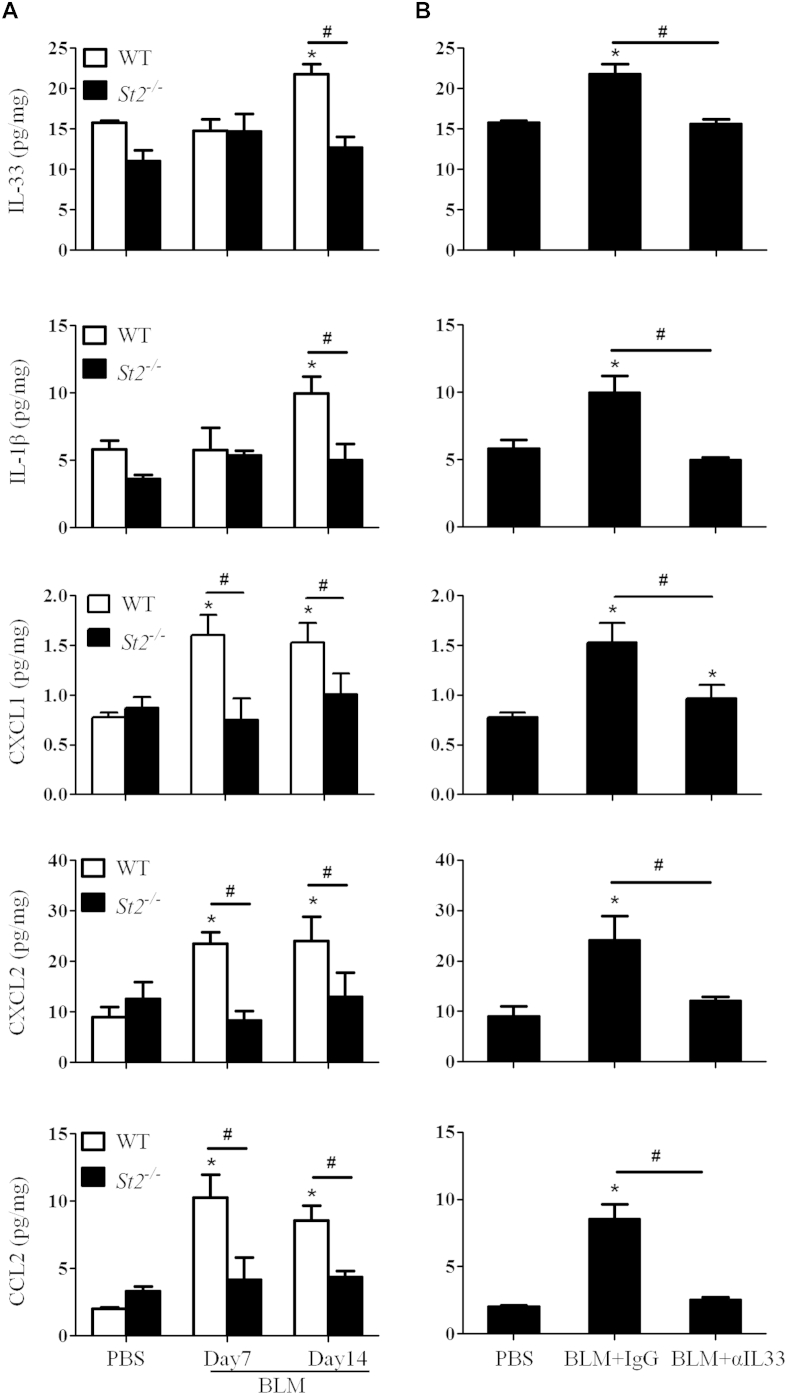

Compared with bleomycin-treated WT mice, bleomycin-treated St2−/− mice also had significantly reduced infiltration of neutrophils on day 7 and total leukocytes, including macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, on day 14 in BAL fluid (Fig 1, D). Furthermore, bleomycin-enhanced concentrations of soluble collagen and the expression of collagen 3, which is associated with early-repair fibrosis, were reduced in St2−/− compared with WT mice (Fig 1, E and F), whereas the expression of collagen 1 remained unchanged (data not shown). Moreover, bleomycin-treated St2−/− mice have reduced concentrations of IL-33, IL-1, and chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2 and CCL2) in lung tissue extracts compared with concentrations seen in bleomycin-treated WT mice (see Fig E1, A, in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

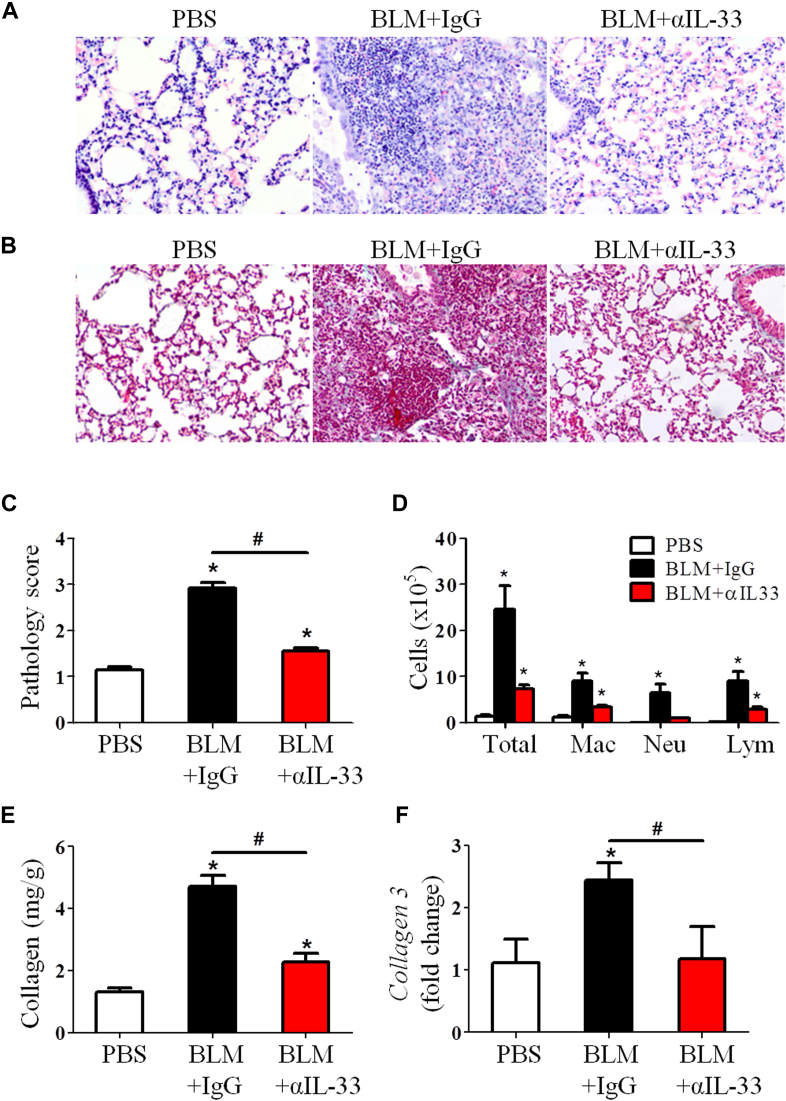

Neutralizing anti–IL-33 antibody attenuates bleomycin-induced fibrosis

We next assessed the role of endogenous IL-33 in the development of bleomycin-induced fibrosis by treating WT mice with anti–IL-33 antibody. C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti–IL-33 every fifth day from day 0 of bleomycin administration and killed on day 14. Anti–IL-33 antibody reduced IL-33 and IL-1 levels in the lung tissue of bleomycin-treated mice compared with that seen in control IgG-treated mice (see Fig E1, B). The antibody treatment also markedly reduced bleomycin-induced airway inflammation and lung fibrosis (Fig 2, A-C) and the number of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes in BAL fluid on day 14 compared with IgG control values (Fig 2, D). Furthermore, the antibody treatment significantly reduced lung tissue soluble collagen (Fig 2, E) and collagen 3 mRNA expression (Fig 2, F).

Fig 2.

Anti–IL-33 antibody treatment attenuates bleomycin (BLM)–induced fibrosis. Lung hematoxylin and eosin staining (A), collagen staining (B), lung pathology score (C), total and differential lung lavage cytology (D), lung tissue collagen content (E), and lung tissue collagen 3 mRNA expression (F) are shown. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 5 mice per group per experiment). *P < .05 compared with PBS and #P < .05 compared with IgG values. Data are representative of 3 experiments. Lym, Lymphocytes; Mac, macrophages; Neu, neutrophils.

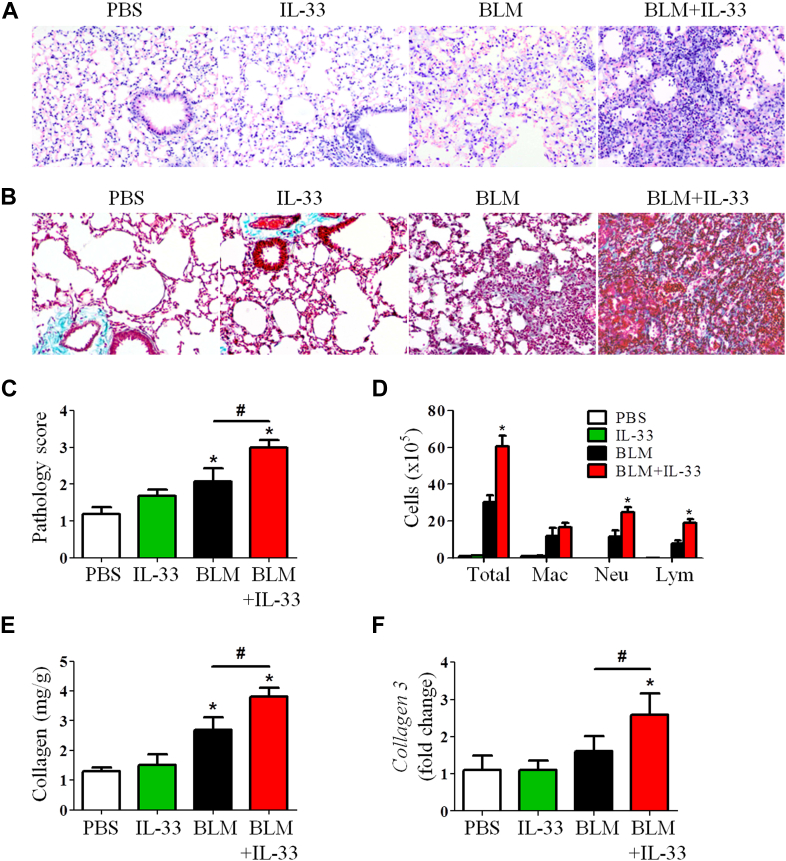

Recombinant mIL-33 exacerbates bleomycin-induced fibrosis in mice

Mice were administered intranasal mIL-33 together with bleomycin on day 0 and lung tissues were analyzed on day 7 to directly assess the role of the cytokine IL-33. Control mice were given either PBS, mIL-33, or bleomycin alone. One administration of exogenous mIL-33 significantly enhanced bleomycin-induced lung inflammation (Fig 3, A), collagen deposition (Fig 3, B), and pathology score (Fig 3, C), compared with controls. The IL-33–enhanced histologic changes were accompanied by significantly increased total numbers of cells in BAL fluid, mainly neutrophils and lymphocytes, compared with control values (Fig 3, D). The coadministration of IL-33 did not change the macrophage numbers in BAL fluid at this time point (7 days) compared with bleomycin alone. IL-33 further increased the levels of bleomycin-induced collagen production (Fig 3, E) and collagen 3 mRNA expression (Fig 3, F). No differences were observed in control groups given one dose of IL-33 compared with the PBS control.

Fig 3.

Recombinant IL-33 exacerbates bleomycin (BLM)–induced fibrosis in mice. Mice were treated with PBS, IL-33, and bleomycin with or without IL-33. Lung hematoxylin and eosin staining (A), collagen staining (B), lung pathology score (C), total and differential lung lavage cytology (D), lung tissue collagen content (E), and lung tissue collagen 3 mRNA expression (F) are shown. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 5 mice per group per experiment). *P < .05 compared with PBS and #P < .05 compared with bleomycin values. Data are representative of 3 experiments. Lym, Lymphocytes; Mac, macrophages; Neu, neutrophils.

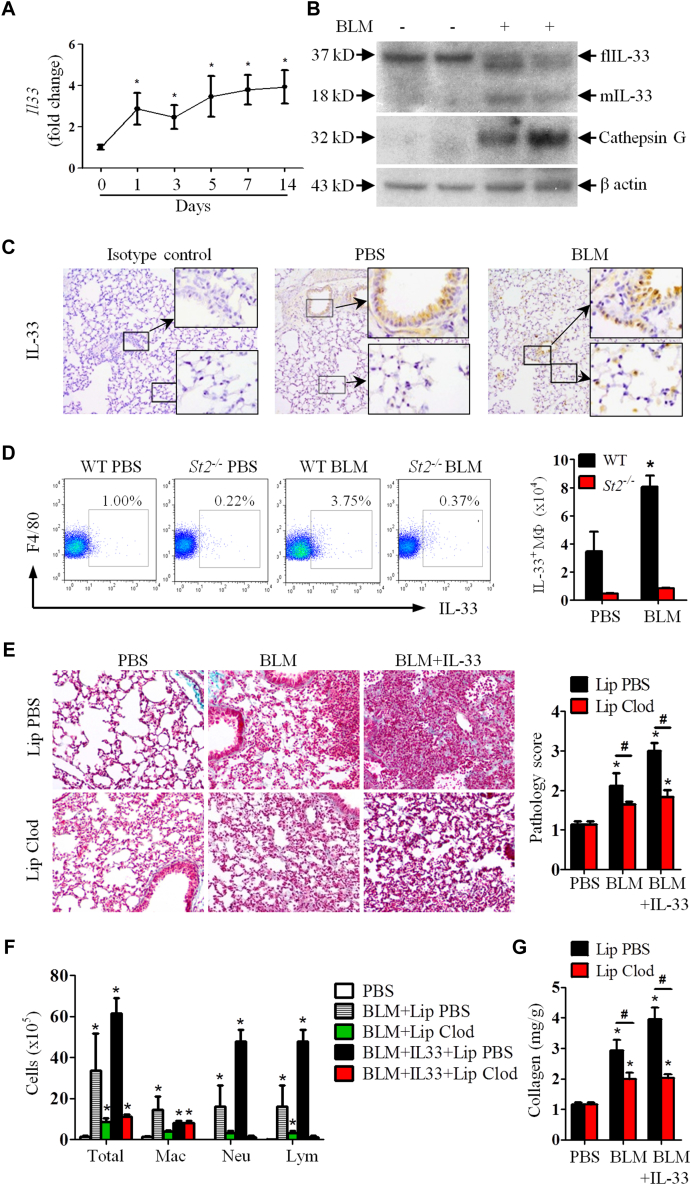

Bleomycin induces IL-33 production, which promotes lung fibrosis through alveolar macrophages

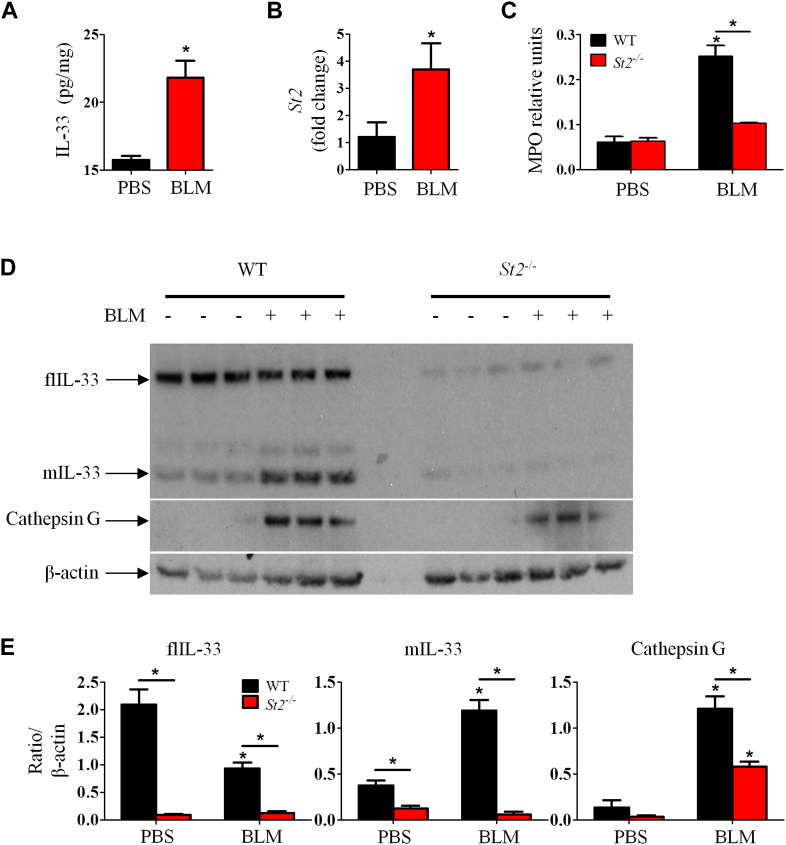

We next determined the kinetics of bleomycin-induced IL-33 expression in the lung. Mice were given bleomycin as above. Bleomycin administration rapidly enhanced Il33 expression in lung tissue from day 1 after bleomycin inoculation and lasted for at least 14 days (Fig 4, A). Compared with PBS, bleomycin treatment also enhanced lung tissue IL-33 protein production (see Fig E2, A, in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org) and St2 mRNA expression (see Fig E2, B). Furthermore, although PBS control WT mice expressed only flIL-33, bleomycin-treated WT mice markedly enhanced mIL-33 concomitant with reduced flIL-33 production (Fig 4, B). Bleomycin also increased production of neutrophil cathepsin G (Fig 4, B) and myeloperoxidase in lung tissue compared with that seen in PBS control in WT mice (see Fig E2, C). The induction of IL-33 isoforms, cathepsin G, and myeloperoxidase in St2−/− mice given bleomycin was markedly reduced compared with that seen in WT mice given bleomycin (see Fig E2, C-E).

Fig 4.

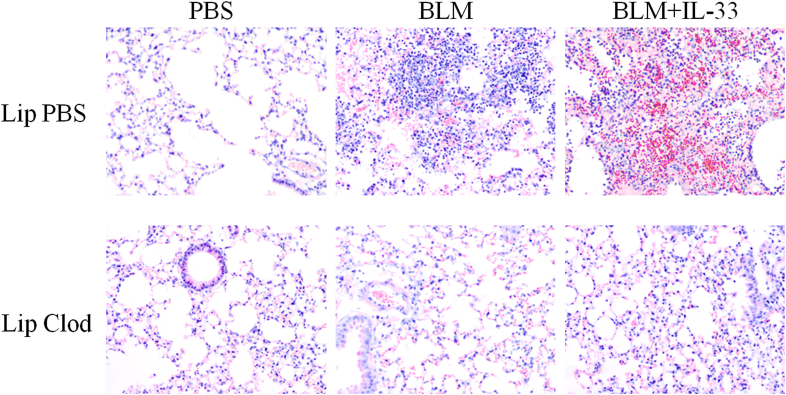

Bleomycin (BLM) induces IL-33 and IL-33 production and promotes lung fibrosis through alveolar macrophages. WT and St2−/− mice were given bleomycin, and lung tissues were analyzed on day 7. A-D,Il33 mRNA expression (Fig 4, A); IL-33 isoforms, cathepsin G, and β-actin detected by using western blotting (Fig 4, B); immunohistochemical staining of IL-33 (×400 magnification; Fig 4, C), and percentage and number of IL-33+ macrophages determined by using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Fig 4, D). E-G, Mice were given PBS, bleomycin, or bleomycin plus IL-33 and treated with clodronate or control liposomes. Lung collagen staining and pathology score (Fig 4, E), total and differential lung lavage cytology (Fig 4, F), and lung collagen content (Fig 4, G) are shown. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 6 mice per group per experiment) *P < .05 compared with PBS and #P < .05 compared with bleomycin values. Data are representative of 2 experiments. Lym, Lymphocytes; Mac, macrophages; Neu, neutrophils.

Immunohistochemical analysis of lung tissue sections of PBS- and bleomycin-treated WT mice demonstrated that alveolar epithelial cells constitutively expressed IL-33 (Fig 4, C). However, administration of bleomycin induced immunohistochemistry-detectable IL-33 protein in cells located within the alveoli compared that seen in with PBS control mice (Fig 4, C). The location and morphologic appearance of these cells suggest that they are alveolar macrophages. The likelihood that these cells were alveolar macrophages is supported by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis, showing that bleomycin treatment significantly increased the frequency and number of IL-33–expressing F4/80+ macrophages in the lung (approximately 2.5 times the number seen in PBS control mice). This increase was not seen in the St2−/− mice given PBS or bleomycin (Fig 4, D).

We next evaluated the importance of alveolar macrophages in bleomycin-induced and IL-33 plus bleomycin–exacerbated lung fibrosis based on their depletion.19, 23 Mice were treated with clodronate in liposomes or control liposomes alone administered intranasally on days 2 and 1 before administration of bleomycin or bleomycin plus IL-33. This route of liposome administration depletes alveolar but not lung parenchymal macrophages.24 Clodronate depleted approximately 80% of alveolar macrophages compared with the control group (Fig 4, F) and significantly reduced bleomycin-induced and bleomycin plus IL-33–exacerbated lung fibrosis (Fig 4, E) and inflammation (see Fig E3 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Consistent with these observations, macrophage depletion also reduced bleomycin-induced and bleomycin plus IL-33–enhanced neutrophil and lymphocyte numbers in BAL fluid (Fig 4, F) and collagen production in lung tissue (Fig 4, G) compared with values seen in the control group given PBS.

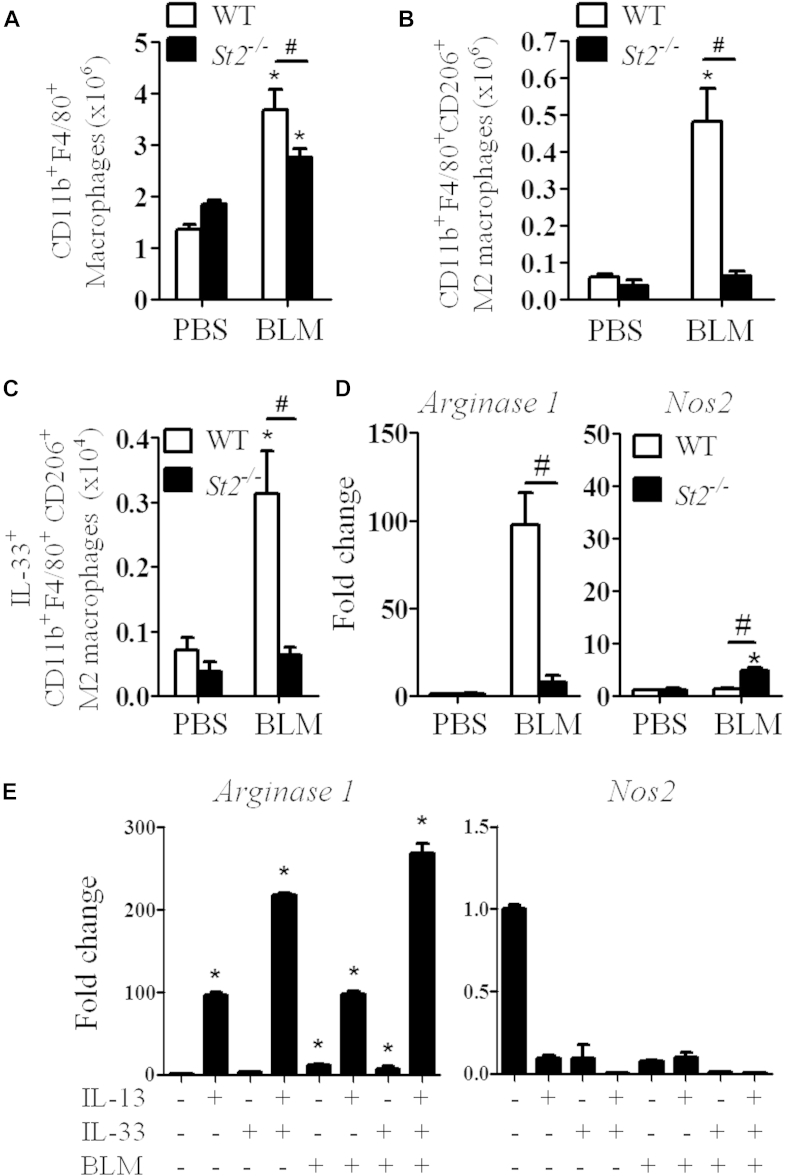

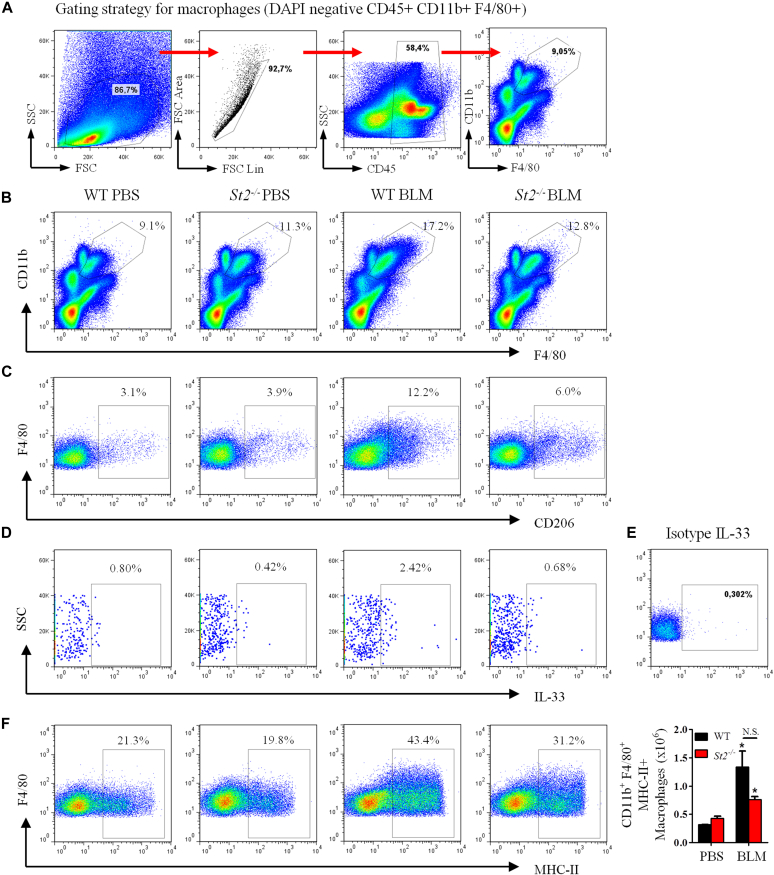

IL-33 polarizes M2 macrophages in lung fibrosis

M2 macrophages play a critical role in fibrogenesis.6 We have shown previously that IL-33, together with IL-13, can polarize alveolar M2 macrophages, but not M1 macrophages, in murine allergic lung remodeling.19 Therefore we further investigated the effect of bleomycin and IL-33/ST2 signaling on the generation of M2 macrophages in patients with lung fibrosis. The frequency and number of total macrophages (CD11b+F4/80high) in the lung tissue of bleomycin-treated St2−/− mice was slightly but significantly reduced compared with that of the bleomycin-treated WT mice (Fig 5, A, and see Fig E4, A and B, in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Bleomycin markedly enhanced the number and percentage of M2 macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+CD206+) in the lungs of WT, but not St2−/−, mice on day 7 after bleomycin treatment (Fig 5, B, and see Fig E4, C). Furthermore, bleomycin also increased IL-33+ M2 macrophage numbers (Fig 5, C, and see Fig E4, D and E) and expression of the gene encoding the M2 macrophage marker arginase 1 (Arg1), but not the M1 macrophage marker inducible nitric oxide synthase 2 (Nos2), in lung tissue in WT mice compared with that seen after control PBS treatment (Fig 5, D). The effects of bleomycin administration on macrophage polarization in St2−/− mice given bleomycin showed no increase in Arg1 expression and increased Nos2 expression compared with that seen in St2−/− mice given the PBS control (Fig 5, C and D). However, the expression levels of MHC class II, a common marker on all macrophages, in mice given bleomycin were not significantly affected by St2 deficiency compared with that seen in WT control mice (see Fig E4, F).

Fig 5.

IL-33 polarizes M2 macrophages. A-C, Numbers of macrophages (Fig 5, A), CD206+ M2 macrophages (Fig 5, B), and IL-33+ M2 macrophages (Fig 5, C). D, Lung tissue Arg1 and Nos2 mRNA expression. E, BMDMs were stimulated with IL-13, IL-33, and bleomycin (BLM; alone or together). Arg1 and Nos2 mRNA expression was quantified. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 5 mice per group per experiment). *P < .05 compared with PBS and #P < .05 compared with WT values. Data are pooled from 3 experiments.

We further assessed the ability of bleomycin, IL-13, and IL-33 to polarize M1 or M2 macrophages in vitro. Mouse bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) were cultured with medium or bleomycin, IL-13, or IL-33 (alone or together), and the induction of Arg1 and Nos2 was determined by using quantitative PCR (qPCR). IL-13, but not IL-33, alone significantly induced Arg1, but not Nos2, expression in macrophages compared with medium control (Fig 5, E). The IL-13–induced Arg1 expression was significantly increased by the presence of IL-33. However, bleomycin alone or in combination with IL-13 or IL-33 had no additional effect on the polarization of M1 or M2 macrophages (Fig 5, E).

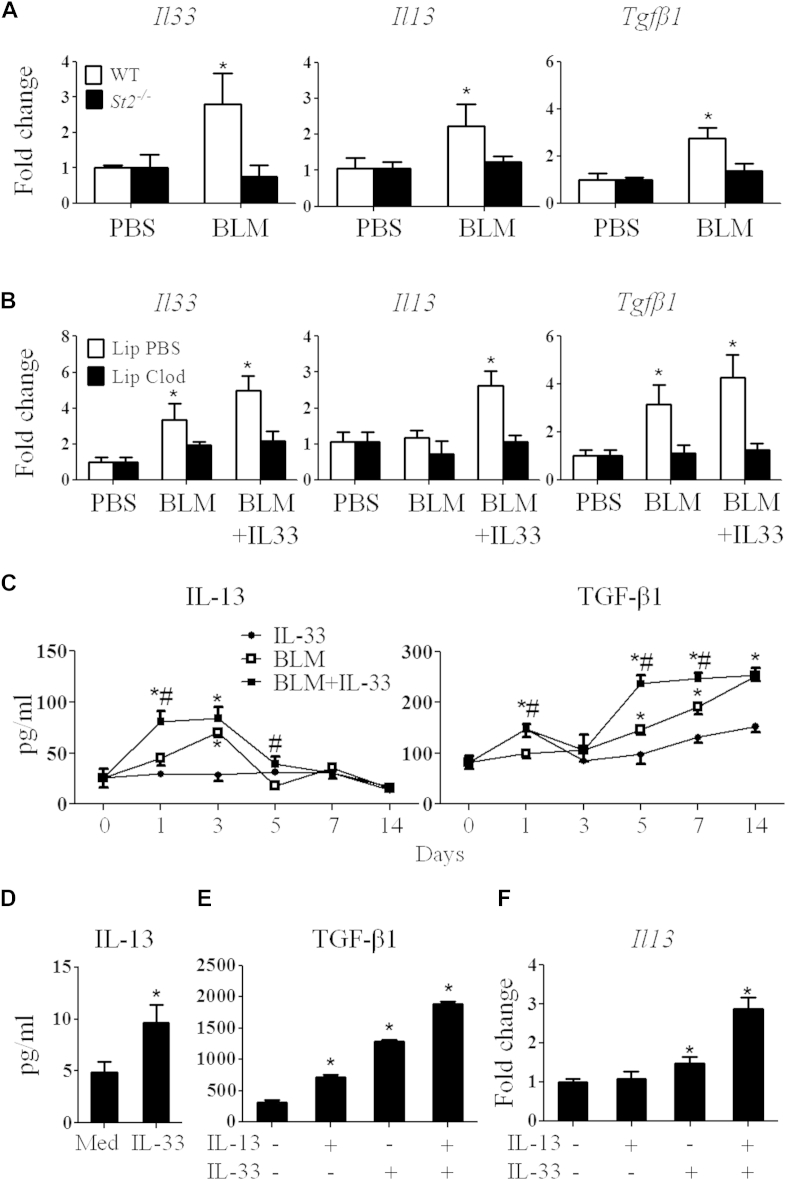

Bleomycin and IL-33 induce fibrogenic cytokine and chemokine production

IL-13 and TGF-β1 are key cytokines required for the development of fibrosis.4, 5, 25 We next determined how the IL-33/ST2 pathway contributes to bleomycin-induced fibrosis by assessing the cytokine and chemokine profiles induced by bleomycin and IL-33. We first analyzed Il33, Il13, and Tgfb1 mRNA expression in the lung tissue of WT or St2−/− mice given bleomycin with or without IL-33. Bleomycin significantly induced expression of these cytokines in WT mice (Fig 6, A). Consistent with the attenuated lung fibrosis seen in St2−/− mice given bleomycin compared with that seen in WT mice given bleomycin (Fig 1, A), bleomycin did not induce Il33, Il13, and Tgfb1 expression in the lungs of St2−/− mice beyond that seen in PBS-treated St2−/− mice (Fig 6, A). Furthermore, alveolar macrophage depletion, which abolished bleomycin-induced and IL-33–exacerbated lung fibrosis (Fig 4, E), also abrogated the bleomycin and bleomycin plus IL-33–induced expression of these cytokines (Fig 6, B).

Fig 6.

Bleomycin (BLM) and IL-33 induce fibrogenic cytokine production. A, Cytokine mRNA expression in the lungs. B, Cytokine mRNA expression in the lungs of clodronate- or liposome-treated mice. C, IL-13 and TGF-β1 production in lung lavage fluid. D and E, IL-13 and TGF-β1 in culture supernatants of BMDMs. F,Il13 mRNA expression in BMDMs. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 5 mice per group per experiment). *P < .05 and #P < .05 compared with control values. Data are representative of 3 experiments.

We then determined the levels of key inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the BAL fluid of bleomycin-treated mice by using Luminex (Luminex; Biosource, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif) or ELISA (BD Biosciences, San Jose, Calif). Only the fibrogenic cytokines IL-1, IL-33, IL-13, and TGF-β1 and 3 chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, and CCL2) were significantly induced by bleomycin and bleomycin plus IL-33 (Fig 6, C, and see Fig E1). No other type 2 and inflammatory cytokines were detected at significant levels (data not shown). We also determined the levels of key fibrogenic cytokines in BAL fluid. Bleomycin induced IL-13 production from day 2, and IL-33 plus bleomycin induced IL-13 synthesis from day 1; both returned to baseline by day 5 (Fig 6, C). Bleomycin-induced TGF-β1 production appeared from day 3 and increased progressively up to at least day 14 (Fig 6, C), and this was further increased by IL-33.

We further confirmed the ability of macrophages to produce IL-13 and TGF-β1 in response to IL-33. BMDMs were stimulated with IL-13, IL-33, or IL-13 plus IL-33. IL-33 stimulated BMDMs to produce a significant amount of IL-13 compared with medium alone (Fig 6, D). IL-13 or IL-33 alone stimulated significantly increased levels of TGF-β1 compared with medium alone. Furthermore, IL-13 and IL-33 synergized to stimulate even higher levels of TGF-β1 production (Fig 6, E) and Il13 expression in macrophages (Fig 6, F).

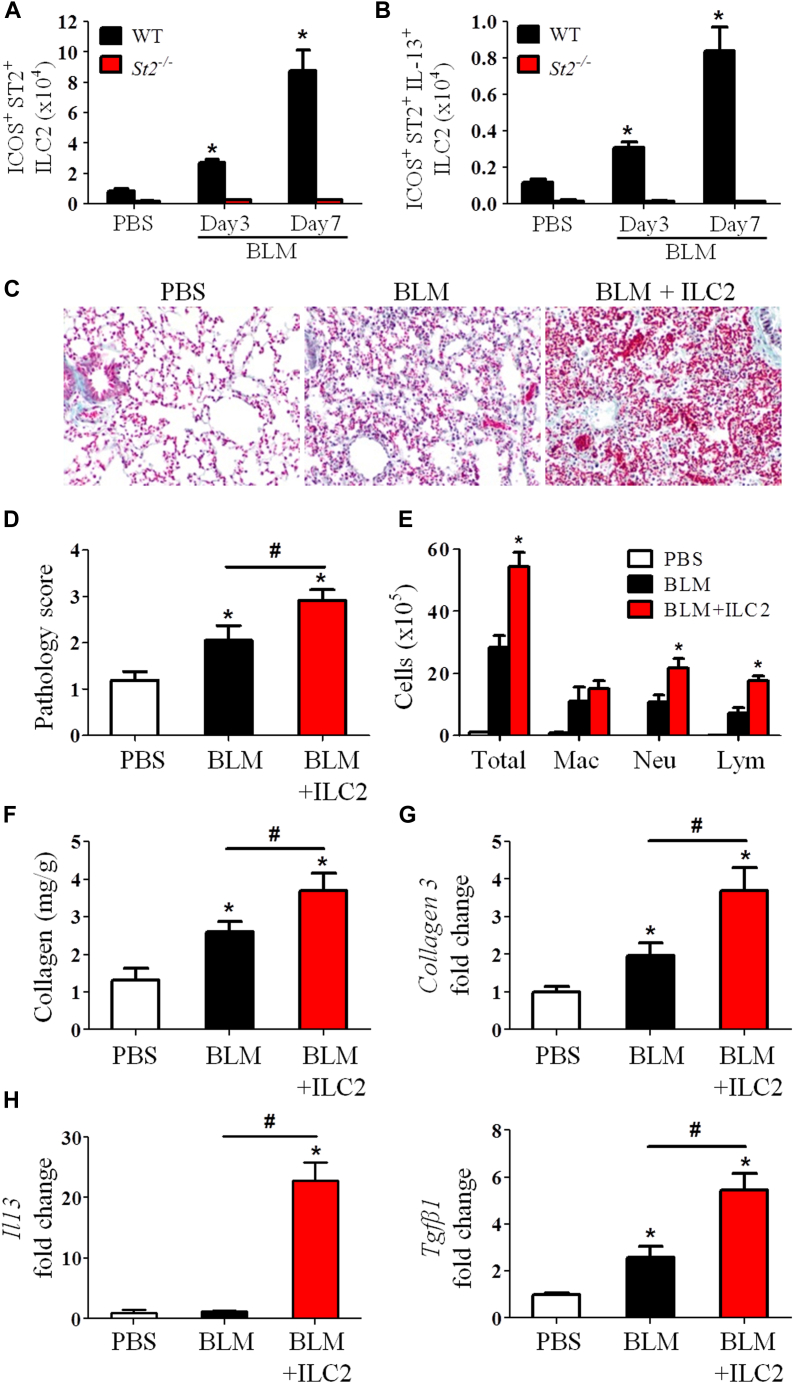

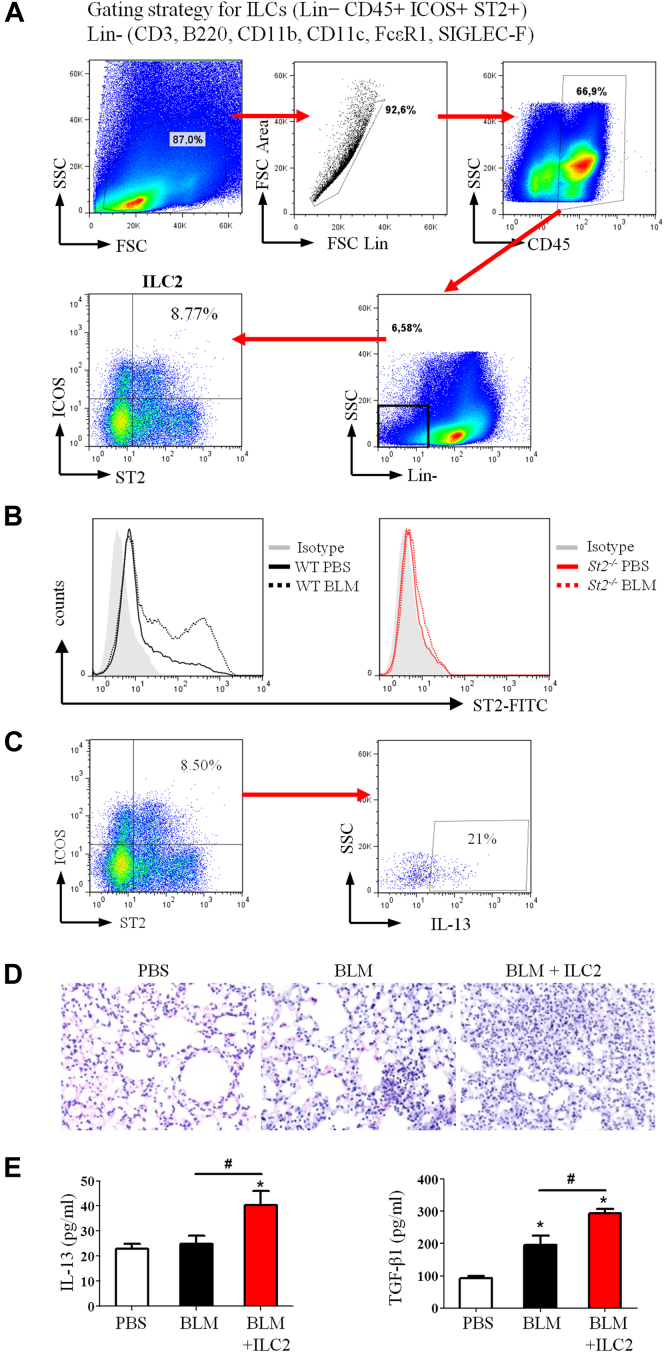

IL-33 enhances ILC2 expansion and function in fibrosis through ST2

Recent reports show that ILC2s are a major source of IL-13 in vivo and that IL-33 is a key inducer of ILC2s through ST2.17, 26, 27 We sought determine whether ILC2s also contribute to the bleomycin plus IL-33–induced IL-13 production and lung fibrosis. WT and St2−/− mice were given bleomycin or PBS control, and the lineage-negative, inducible costimulator, (ICOS)–positive ST2+ ILC2s in the lungs were analyzed 3 to 7 days after bleomycin treatment (see Fig E5, A and B, in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).28 Bleomycin treatment markedly enhanced ILC2 numbers in the lungs of WT mice compared with those seen in control PBS-treated mice (Fig 7, A). In contrast, ILC2s were almost completely absent in St2−/− mice, irrespective of whether they were treated with bleomycin. By day 7, the number of IL-13+ ILC2s was enhanced 8-fold in WT mice given bleomycin compared with that seen in PBS control mice (Fig 7, B, and see Fig E5, C). Again, IL-13+ ILC2s were almost completely absent in St2−/− mice (Fig 7, B). To understand the role of ILC2s in IL-33– and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, we adoptively transferred purified ILC2s into WT mice 1 day after bleomycin and compared this with conditions after bleomycin alone. The ILC2 transfer led to exacerbation of lung inflammation and fibrosis compared with bleomycin alone (Fig 7, C and D, and see Fig E5, D), and this was similar to that observed after bleomycin plus IL-33 instillation (Fig 3). The pathogenic changes were accompanied by increased inflammatory cell infiltration and collagen production and expression of collagen 3, Il13, and Tgfb1 in lung tissue compared with that seen in mice given bleomycin alone (Fig 7, E-H, and see Fig E5, E).

Fig 7.

Induction and function of ILC2s in the lungs. A and B, Total number of ILC2s (Fig 7, A) and IL-13+ ILC2s (Fig 7, B). C-F, ILC2s were adoptively transferred into mice after bleomycin (BLM) instillation. Collagen staining (Fig 7, C), pathology score (Fig 7, D), total/differential lung lavage cytology (Fig 7, E), and collagen content (Fig 7, F) are shown. G and H, Collagen 3 (Fig 7, G) and Il13 and Tgfb (Fig 7, H) mRNA expression. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 6 mice per group per experiment). *P < .05 compared with PBS and #P < .05 compared with bleomycin values. Data are representative of 2 experiments.

Discussion

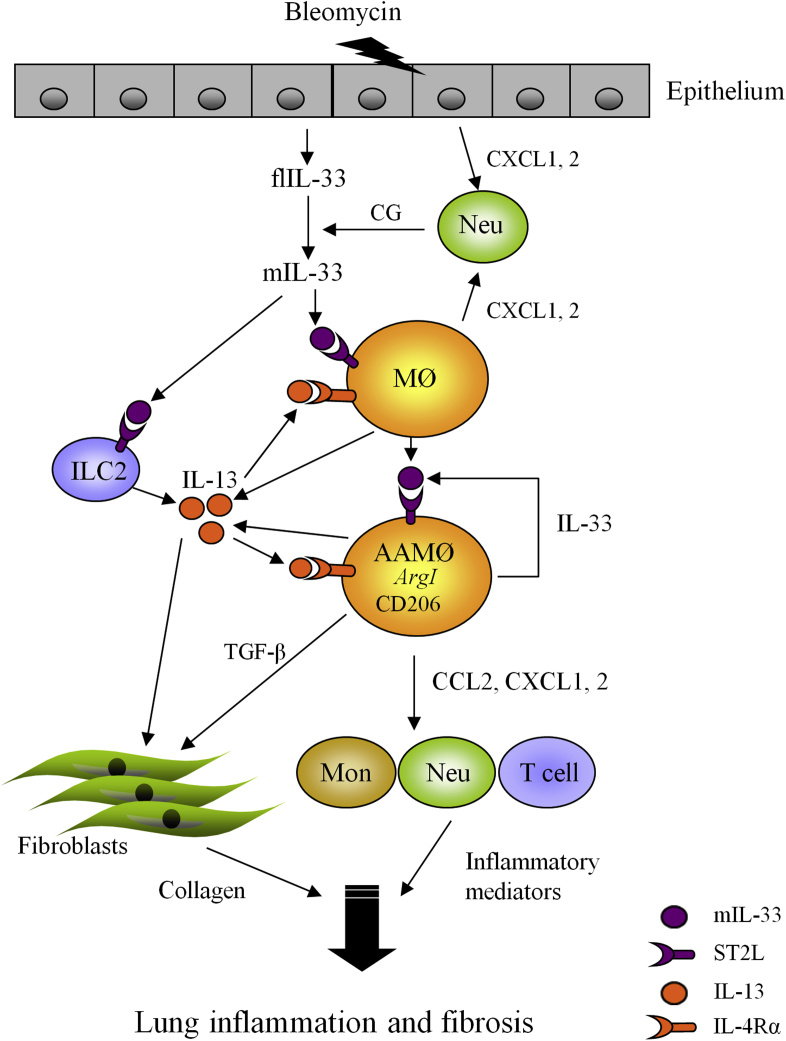

Data reported in this study reveal a hitherto unrecognized effect and mechanism by which IL-33 exacerbates bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice (see Fig E6 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Bleomycin can elicit early neutrophil infiltration and release of flIL-33 mainly by airway epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages (see Fig E7 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). flIL-33 can then be processed into mIL-33 by neutrophil proteases, which subsequently stimulates macrophages and ILC2s to produce IL-13. IL-13 and mIL-33 then synergistically induce the polarization of M2 macrophages and increase production of IL-13 and TGF-β1. These cytokines are powerful activators of fibroblasts, stimulating proliferation and increased collagen synthesis and thereby amplifying pulmonary fibrosis. Thus the IL-33/macrophage/M2 macrophage pathway is centrally involved in the bleomycin-mediated fibrotic process, whereas the IL-33/ILC2 pathway only contributes to the process by providing a proportion of the IL-13 pool in fibrotic tissue (see Fig E6).

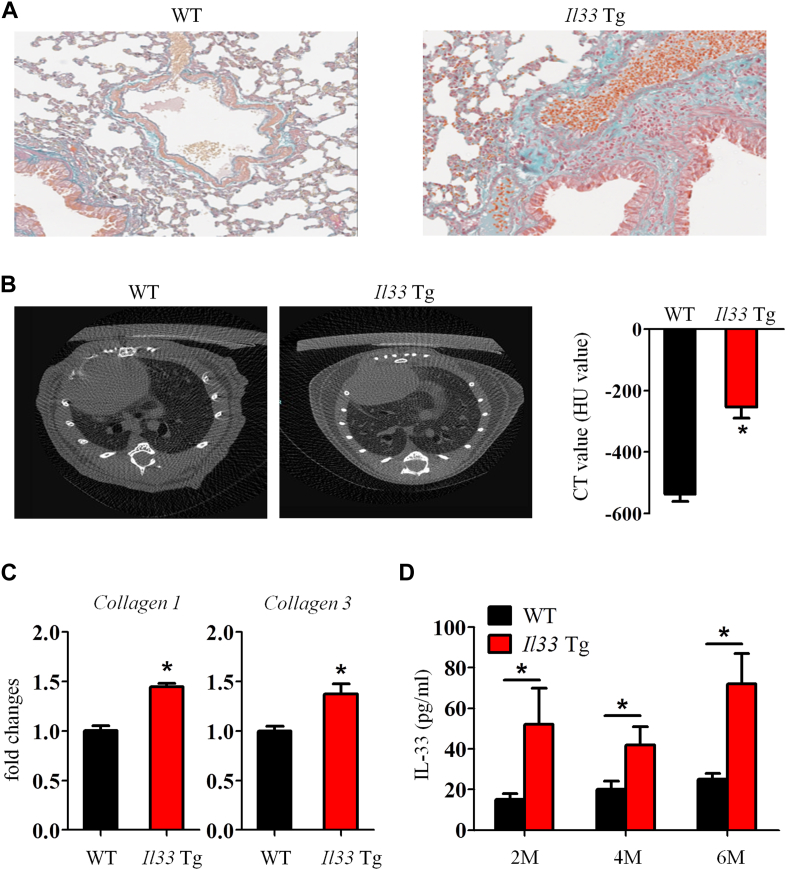

Although a single administration of exogenous mIL-33 on its own was not sufficient to induce pulmonary fibrosis by day 14 (Fig 3), we found that Il33 transgenic mice that constitutively express low mIL-33 levels (approximately 80 pg/mL in serum) spontaneously had lung interstitial fibrosis (see Fig E8 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Thus mIL-33 is likely a key profibrotic factor.

We also show that the profibrogenic effect of mIL-33 is mainly attributed to its role in M2 macrophage polarization. Macrophages are polarized toward an M2 phenotype in a TH2 cytokine–dominant milieu,6 and local mIL-33, together with IL-13, enhanced M2 macrophage polarization in our study. Furthermore, the specificity of the requirement for IL-33 in this process is demonstrated by the fact that bleomycin alone, which was not able to induce M2 macrophage polarization in St2−/− mice, also did not cause fibrosis in St2−/− mice. We found that macrophages are the predominant cells that express both IL-33 and ST2 in fibrotic lungs (see Fig E7, Fig E9 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Thus IL-33/ST2 signaling might promote M2 macrophage development and function in bleomycin-induced fibrogenesis in an autocrine and paracrine fashion.

The profibrogenic cytokines TGF-β1 and IL-13 are necessary for the development of tissue fibrosis.4, 5, 25 However, how these cytokines are induced in bleomycin-induced fibrosis is unresolved. Here we show that IL-33 signaling through ST2 is essential for optimal induction of both IL-13 and TGF-β1 expression in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, although in different cells. IL-33 primarily induces the production of IL-13 by both macrophages and ILC2s and production of TGF-β1 by macrophages. These findings also suggest that mIL-33 is a novel TGF-β1 inducer, which might explain its fibrogenic role in bleomycin-induced fibrosis.

We demonstrated that bleomycin instillation increased the infiltration of leukocytes, mainly neutrophils but also macrophages and lymphocytes, into the airways and lung interstitium. This might be a consequence of IL-33/ST2–dependent and independent production of the key chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2 in the context. As reported, CXCL1 and CXCL2 determine the migration of neutrophils, and CCL2 is used for the migration of lymphocyte and monocyte/macrophage into the inflamed lung tissue of mice.29, 30 Because these chemokines are mainly produced by macrophages,29, 30 this might explain why macrophage depletion also reduced lung lavage neutrophils and lymphocytes in the setting of bleomycin-induced fibrosis.

The precise role of neutrophils in IL-33–exacerbated pulmonary fibrosis is incompletely understood. We suggest an additional role through which neutrophil proteases contribute to fibrosis. We found that bleomycin simultaneously enhanced the production of mIL-33 but reduced the production of flIL-33 in lung tissue. mIL-33 production was associated with neutrophil cathepsin G production in the same lung tissue, suggesting that flIL-33 was processed to mIL-33, which has greater bioactivity.31 Because epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages can produce CXCL1 and CXCL2 independent of IL-33/ST2 signals,29, 30, 32 these cells might be responsible for the bleomycin-induced early neutrophil infiltration in lung tissue (see Fig E6).

A recent report showed that adenovirus-delivered flIL-33, the form of IL-33 located in the nucleus, promoted lung fibrosis through an undefined but ST2-independent mechanism.9 This study, together with data in the present report, suggests that both flIL-33 and mIL-33 are fibrogenic and that they might induce fibrosis through distinct mechanisms. These findings are thematically linked with the data presented here; however, there are several important differences between these 2 studies that might together provide deeper understanding of the role of IL-33 in fibrosis. We tested the role of mIL-33 as a secreted cytokine, which acts through the cell-surface IL-33 receptor (ST2), whereas Luzina et al9 tested the function of intranuclear flIL-33 delivered through a viral vector. We used St2−/− mice of the fibrosis-sensitive C57BL/6 strain, whereas Luzina et al9 used St2−/− mice of the fibrosis-resistant BALB/c strain.33 Thus the apparent discrepancies between the 2 studies might be partly due to the different mode of action of mIL-33 versus flIL-33 and the strain of mouse used.

IL-33 is clearly detected in patients with several chronic fibrotic diseases, including IPF, cystic fibrosis, and systemic sclerosis.9, 34, 35 Given that inflammation and fibrogenesis are the common pathogenic characteristic of these disorders and can be exacerbated by IL-33, IL-33 might have a general contribution to a range of fibrotic diseases. Therefore regulation of IL-33 could be a novel therapeutic strategy for these diseases.

Key messages.

-

•

Bleomycin enhanced the production of mIL-33 but reduced flIL-33 production in lung tissue in vivo.

-

•

ST2 deficiency, anti–IL-33 antibody, or alveolar macrophage depletion attenuated and exogenous mIL-33 or adoptive transfer of ILC2s enhanced bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice.

-

•

IL-33 polarized M2 macrophages to produce both IL-13 and TGF-β1 and induced the expansion of ILC2s to produce IL-13 in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr Jim Reilly for help with histology and Mrs Helen Arthur for proofreading.

Footnotes

Supported by Arthritis Research UK (AR UK 18912 to D.X.), the Medical Research Council UK, and the Wellcome Trust (to F.Y.L.).

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: G. J. Graham has received research support from and travel support from the Medical Research Council (MRC), has received participation fees from and is a board member for the Wellcome Trust, and is employed by the University of Glasgow. F. Y. Liew has received research support from MRC. C. McSharry is employed by the UK National Health Service. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Charles McSharry, Email: Charles.McSharry@glasgow.ac.uk.

Damo Xu, Email: Damo.Xu@glasgow.ac.uk.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Olac (Bicester, United Kingdom). St2−/− mice were on a C57BL/6 background.E1 Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at Glasgow University, and procedures were in accordance with the UK Home Office animal experimentation guidelines. Il33 transgenic mice were on a C57BL/6 backgroundE2 and housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care–accredited facility (Beijing, China). The procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chinese Institute of Laboratory Animal Science (GC-08-2018).

Bleomycin-induced fibrosis

C57BL/6 mice were lightly anaesthetized with isoflurane gas (4%), and bleomycin sulfate (0.1 U per 25-g mouse in 30 μL of PBS; Sigma, St Louis, Mo) or PBS was administered intranasally. BAL fluid, blood, and lungs were harvested 7 or 14 days later and processed and analyzed, as described previously.E3, E4 The time points selected in the experiments were determined by our pilot experiments and by a consensus of the various time points used in the literature describing mouse bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. After bleomycin instillation in mice, lung tissue displays typical acute inflammation from days 1 to 5, and early expression of fibrotic markers and collagen deposition can be seen from day 7 and is more pronounced by day 14. Thus days 7 and 14 were used to investigate whether ST2 signals are involved in early development and overall severity of lung fibrosis in St2−/− mice. Day 7 was also used to determine whether exogenous IL-33 instillation could exacerbate bleomycin-induced fibrosis. The mice were inoculated intranasally with a single dose (500 ng per mouse) of recombinant murine mIL-33 (BioLegend, San Diego, Calif, or prepared as described previouslyE5) on day 0 of bleomycin treatment and killed on day 7. Day 7 was also the end point used for the macrophage depletion experiment to test whether this procedure would abolish exogenous IL-33–exacerbated fibrotic effect seen at day 7. Alveolar macrophage depletion was performed by means of intranasal administration of clodronate (ClodLip BV) or control liposomes (40 μL per mouse) at 24 and 72 hours before bleomycin administration, and the mice were killed on day 7.E3, E6 Day 14 was selected to study the potential therapeutic effect of neutralizing anti–IL-33 on the more severe established fibrosis. The mice were treated intraperitoneally with neutralizing anti–IL-33 antibodyE7 or control normal rabbit IgG (Sigma, 150 μg per mouse) on the day of bleomycin administration and 5 and 10 days thereafter. The mice were killed on day 14. Perfused lung tissue (100 mg) was dispersed in 1 mL of ice-cold RIPA Lysis Buffer with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sigma) for 45 minutes. Cell suspensions were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm in an Eppendorf tube for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was collected for cytokine and collagen assay.

Cell culture

Primary BMDMs were generated with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (10 ng/mL; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), as described previously.E3 The subsequent cell preparations contained more than 95% F4/80+ macrophages, as determined by using fluorescence-activated cell sorting. The cells (0.5 × 106/mL) in culture medium were placed into 24-well plates (Invitrogen) and cultured for 24 or 48 hours. Culture supernatants were stored at −20°C for cytokine analysis, and cells were harvested for mRNA extraction for the qPCR assay.

Western blotting analysis

Tissue was lysed in RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden) containing protease inhibitors (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Protein concentrations were estimated by using the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill). Proteins were then incubated at 70°C for 10 minutes in reducing SDS sample buffer, and 30 μg of protein lysate per lane was run through NuPAGE Novex 4-12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif) and transferred to Hybond ECL membranes (GE Healthcare, Fairfield, Conn). Membranes were blocked for 1 hour in 5% nonfat dried milk in double-distilled PBS and incubated overnight with the appropriate primary antibody at 4°C. Membranes were then washed in double-distilled PBS/Tween 20 and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody. Detection was performed with ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare). Antibodies against flIL-33 and mIL-33 were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn; AF3626, goat anti-mouse IL-33 polyclonal antibody); cathepsin G, β-actin, and all secondary antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Tex). The intensity of Western blot bands was quantified by means of densitometry with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md).

Determination of myeloperoxidase activity

Lung homogenates were prepared in 1 mL of RIPA buffer by using a tissue homogenizer and myeloperoxidase assay performed as previously described.E8 Results are expressed as relative units (OD, 492 nm) and were corrected for the activity of other peroxidases, which were not inhibited by 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole.

Flow cytometry

Lungs were harvested on day 3 or 7 after bleomycin administration and digested in 125 μg/mL Liberase TL and 100 μg/mL DNAse 1 (Roche Diagnostics) to characterize the infiltrating leukocytes. Dispersed cells (1 × 106 cells per tube) were stained with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride, UVE/DEAD fixable Aqua Dead cell stain (Life Technologies), and fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs against F4/80-Pacific blue (eBioscience, San Diego, Calif), cytokeratin 11–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; panepithelial cell marker; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), ER-TF7–allophycocyanin (APC; panfibroblast marker, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CD3-PercP, CD11b-FITC or PercP, CD11c-APC, CD49b–phycoerythrin (PE), CD206-APC, Ly6G-APC, Siglec-F–PE, MHC class II–PercP, CD45-AF700, and isotype controls (all from BD Biosciences, unless otherwise indicated). Leukocytes were stained with antibodies against ST2–FITC (MD Biosciences), lineage markers (B220, FcεRI, CD11b, CD3ε, and Siglec F) labeled with PE, CD45-AF700, and ICOS-PerCP/Cy5.5 (eBioscience) to characterize the infiltrating ILC2s. Intracellular IL-33 or IL-13 was detected by staining with anti–IL-33–PE (R&D Systems) or anti–IL-13–APC (eBioscience) after activation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (1 μg/mL) in the presence of BD GolgiStop and cell permeabilization (BD Cytofix/Cytoperm, BD Biosciences). Cells were analyzed with a Beckman Coulter CyAn ADP Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, Calif). Gating strategy (Fig E4, A, and E5, A) and analysis were performed with FlowJo software (TreeStar, Eugene, Ore).

ILC2 amplification and isolation and adoptive cell transfer

For ILC2 amplification in vivo, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and treated with IL-33 (1 μg administered intranasally) daily for 5 days, as described previously.E9 Lungs were harvested on day 6 and digested in 125 μg/mL Liberase TL and 100 μg/mL DNAse 1 (Roche Diagnostics). Nonadherent cells were stained for ST2, lineage markers, ICOS, CD45, and UVE/DEAD fixable Aqua Dead cell stain (Life Technologies) as above and sorted with a BD FACSAria. For cell transfer, 5 × 105 ILC2s in 40 μL of PBS were inoculated intranasally 1 day after bleomycin challenge. Mice were culled on day 7 after bleomycin instillation to assess lung inflammation and fibrosis.

Cytokine measurements

Concentrations of cytokines and chemokines in BAL fluid, cell cultures, and whole-lung homogenates were determined by using Luminex (Luminex, Biosource, Invitrogen) or ELISA (BD Biosciences), according to the manufacturers' instructions.

qPCR

RNA was purified from tissue samples by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Manchester, United Kingdom), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA was carried out with High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif). RT-PCR was performed with Fast SYBR Green master mix on a Prism 7900HT (Applied Biosystems). The primers used were as follows: Il13 forward 5′-GAA TCC AGG GCT ACA CAG AAC-3′, reverse 5′-AAC ATC ACA CAA GAC CAG ACT C-3′; Il33 forward 5′-ACT ATG AGT CTC CCT GTC CTG-3′, reverse 5′-ACG TCA CCC CTT TGA AGC-3′; St2 forward 5′-TCT GTG GAG TAC TTT GTT CAC C-3′, reverse 5′-TCT GCT ATT CTG GAT ACT GCT TTC-3′; Tgfb1 forward 5′-CCA TGA GGA GCA GGA AGG-3′, reverse 5′-ACA GCA AAG ATA ACA AAC TCC AC-3′; Arg1 forward 5′-AGT GTT GAT GTC AGT GTG AGC-3′, reverse 5′-GAA TGG AAG AGT CAG TGT GGT-3′; Nos2 forward 5′-GCC TCG CTC TGG AAA GA-3′, reverse 5′-TCC ATG CAG ACA ACC TT-3′; collagen 1 forward 5′-CAT TGT GTA TGC AGT GAC TTC-3′, reverse 5′-CGC AAA GAG TCT ACA TGT CTA GGC-3′; and collagen 3 forward 5′-TCT CTA GAC TCA TAG GAC TGA CC-3′, reverse 5′-TTC TTC TCA CCC TTC TTC ATC C-3′.

Collagen assay

The soluble collagen in lung tissues was quantified with the Sircol Collagen Assay (Biocolor, Carrickfergus, United Kingdom), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Histologic analysis

The larger left lung lobe was excised, fixed in 4% buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Cellpath, Newtown, United Kingdom) or Gomori Rapid One-Step Trichrome Stain (Sigma) for collagen. The pathology score (from 1-4) was determined by using a method modified from a previous reportE10: 1, no abnormal fibrosis; 2, occasional small interstitial fibrotic foci; 3, moderate interalveolar septal thickening and fibrotic foci; and 4, continuous interalveolar fibrosis.

Micro–computed tomographic scanning

Il33 transgenic mice, which overexpress the mature form of IL-33, were kept in pathogen-free conditions for up to 6 months, and the development of lung fibrosis was determined by using computed tomographic (CT) scans. Scans were performed with a cone-beam micro-CT scanner (Inveon; Siemens Healthcare, Munich, Germany), as previously described.E11 WT and Il33 transgenic mice were anesthetized and placed in the prone position on the micro-CT bed without respiratory gating. The tube voltage was 70 kVp, current was 400 mA, and exposure time was 800 ms. The scan field of view was 72.44 mm × 71.31 mm. Projection images were acquired with a single tube/detector over a circular orbit of 360° with a step angle of 1°. Reconstructions were performed by using a commercially available CT reconstruction program (COBRA Exxim, version 6.3), with a filtered back-projection technique. A resolution of approximately 70.74 μm per pixel was achieved.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by using 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey or Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis. One-way ANOVA was used to examine mean differences between 2 or more groups to compare every mean with every other mean. Kinetic experiments (ie, cytokine expression over time or in vitro data) were analyzed by using repeated-measures ANOVA. The analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 statistical software (GraphPad software, San Diego, Calif). All results were presented as means and SEMs from 5 to 7 mice per group per experiment. Data are representative of at least 2 separated experiments. A P value of less than .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Fig E1.

Cytokine and chemokine concentrations quantified by means of ELISA in dispersed lung tissue (in milligrams) supernatants of WT and St2−/− mice treated with PBS or bleomycin (BLM) at days 7 and 14 (A) and WT mice given bleomycin; treated with PBS, anti–IL-33, or control IgG; and killed on day 14 (B) are shown. Vertical bars = means ± SEMs (n = 5-6 mice per group per experiment) *P < .05 compared with PBS control and #P < .05 compared with ST2−/− mice or IgG control values. Data are representative of 3 experiments.

Fig E2.

Bleomycin (BLM) induces IL-33 and ST2 production in fibrotic lung tissue. WT and St2−/− mice were given bleomycin, and lung tissues were analyzed on day 7. IL-33 concentration determined by means of ELISA (A), St2 mRNA expression (B), myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (C), and IL-33 isoforms, cathepsin G, and β-actin detected by means of Western blotting (D) are shown. E, The intensity of Western blot bands in Fig E2, D, was quantified by means of densitometry. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 6 mice per group per experiment). *P < .05 compared with PBS values. Data are representative of 3 experiments.

Fig E3.

Depletion of alveolar macrophages reduces bleomycin (BLM)– and bleomycin plus IL-33–induced lung inflammation. Mice were treated with PBS, clodronate in liposome (Clod), or liposomes alone (Lip) 1 day before administration of bleomycin or bleomycin plus IL-33. Lungs were harvested on day 7, and lung tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (original magnification ×200). Data are representative of 3 experiments (n = 5-6 mice per group per experiment).

Fig E4.

A, Flow cytometric gating strategy for analysis of macrophages in dispersed lung cell suspensions. B-F, WT or St2−/− mice were administered intranasally with PBS or bleomycin, and lung tissue harvested on day 7 was dispersed. The percentage of macrophage subsets in the tissue was determined by using flow cytometry. The percentage of macrophages (Fig E4, B), percentage of CD206+ (M2) macrophages (Fig E4, C), percentage of IL-33+ M2 macrophages (Fig E4, D), isotype control for the anti–IL-33–PE staining (Fig E4, E), and percentage and total number of MHC class II–positive macrophages (Fig E4, F) are shown. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 5-6 mice per group per experiment). *P < .05 compared with control values. Data are representative of 2 experiments. N.S., Not significant.

Fig E5.

Induction and function of ILC2s in lung fibrosis of mice. A, Fluorescence-activated cell sorting gating strategy used for identification of ILC2s in murine lung tissue. B, ILC2s from WT but not St2−/− mice expressed ST2. C, Percentage of IL-13+ ILC2s in lung tissue of WT mice after bleomycin (BLM) instillation. D and E, Adoptive transfer of ILC2s contributes to lung inflammation in mice. WT mice were instilled with PBS or bleomycin. Sorted ILC2s (5 × 105) were adoptively transferred intranasally into mice 1 day after bleomycin instillation, and lung inflammation was assessed on day 7. Fig E5, D, Hematoxylin and eosin staining of lung tissues. Fig E5, E, Lung lavage fluid IL-13 and TGF-β1 concentrations quantified by means of ELISA. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 5-6 mice per group per experiment). *P < .05 compared with PBS control and #P < .05 compared with bleomycin control values. Data are representative of 2 experiments.

Fig E6.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism of bleomycin (BLM)–induced IL-33 synthesis and its contribution to lung fibrosis. Neomycin triggers release of flIL-33 from damaged airway epithelial cells and recruitment of neutrophils. Neutrophil cathepsin G (CG) then processes flIL-33 to mIL-33. mIL-33 stimulates alveolar macrophages and ILC2s to produce IL-13. mIL-33 and IL-13 then synergistically polarize macrophages into the M2 macrophage phenotype, which produces more IL-33, IL-13, and TGF-β1 and in turn activates fibroblasts to proliferate and overproduce collagen. IL-33 also enhances macrophage production of chemokines, which induce the infiltration of neutrophils and lymphocytes into the lung and together might exacerbate lung inflammation and development of fibrosis. Mon, Monocytes; Neu, neutrophils.

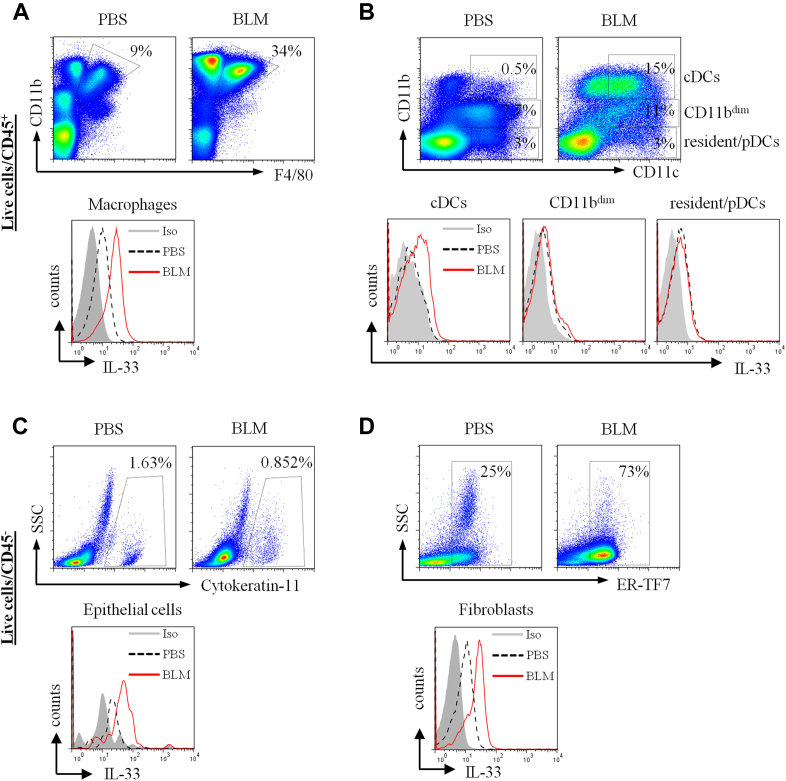

Fig E7.

Detection of IL-33–producing cell populations in bleomycin-induced fibrotic lung tissue. Mice were given intranasal PBS or bleomycin (BLM) on day 0, and lung tissues were harvested on day 7. Tissues were dispersed, and live single-cell preparations were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies to CD45 to categorize hematopoietic (A and B) and nonhematopoietic (C and D) cells. Staining for IL-33 and the different cell linage markers are as described in the Methods section. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting dot plots and histograms are presented. IL-33+ cells were detected in macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+; Fig E7, A); conventional DCs (cDCs; CD11c+), CD11bdim, and resident/plasmacytoid DCs (Fig E7, B); epithelial cells (cytokeratin 11+; Fig E7, C); and fibroblasts (ER-TF7+; Fig E7, D). Data are representative of 3 experiments (n = 5-6 mice per group per experiment).

Fig E8.

Il33 transgenic mice have spontaneous lung fibrosis. WT and Il33 transgenic mice were kept in pathogen-free conditions for up to 6 months. A, Lung tissues were stained for collagen deposition at 6 months. B, CT scan of mouse thorax was performed, and lung radiodensity scale (Hounsfield units [HU]) was calculated. C, Lung tissue collagen 1 and 3 mRNA expression was quantified by using qPCR. D, IL-33 concentration in mouse serum was quantified by means of ELISA at 2, 4, and 6 months of age. Vertical bars = SEMs (n = 10 mice per group per experiment). *P < .05 compared with WT control values. Data are representative of 2 experiments.

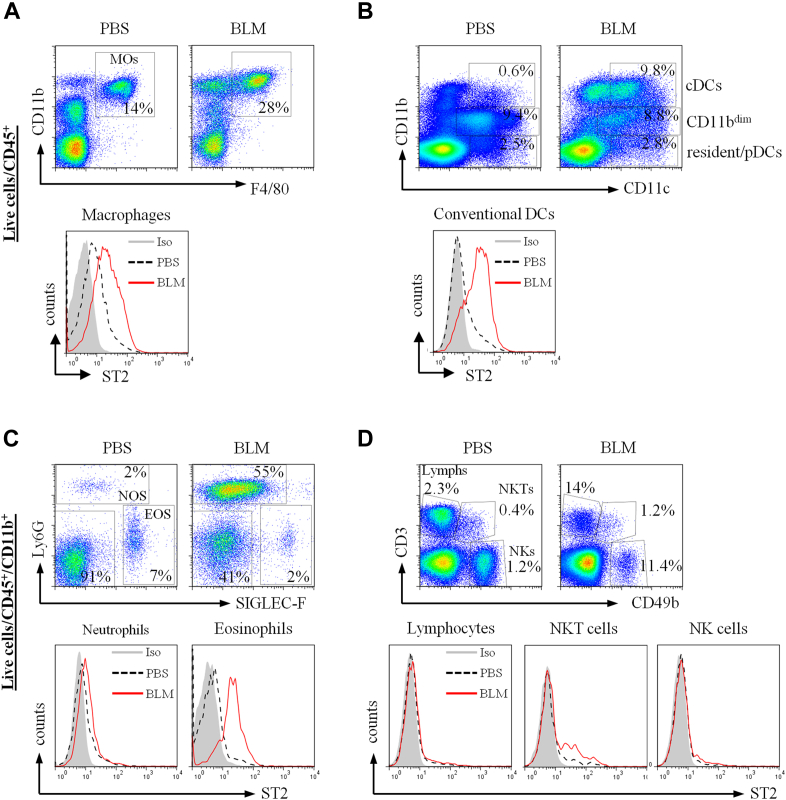

Fig E9.

Detection of ST2+ cell populations in bleomycin (BLM)–induced fibrotic lung tissue. Mice were given intranasal PBS or bleomycin on day 0, and lung tissues were harvested on day 7. Tissues were dispersed, and live single-cell preparations stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies to ST2 and different cell linage markers, as described in the Methods section. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting dot plots and histograms are presented. ST2 expression was detected on macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+; Fig E9, A), dendritic cells (CD11c+, conventional DCs [cDCs], CD11bdim and resident/plasmacytoid dendritic cells [pDCs]; Fig E9, B), granulocytes (neutrophils [NOS] and eosinophils [EOS]), and lymphocytes (Lymphs), natural killer (NK) cells, and natural killer T (NKT) cells (Fig E9, D). Data are representative of 2 experiments (n = 5-6 mice per group per experiment).

References

- 1.Mouratis M.A., Aidinis V. Modeling pulmonary fibrosis with bleomycin. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:355–361. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328349ac2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umezawa H., Ishizuka M., Maeda K., Takeuchi T. Studies on bleomycin. Cancer. 1967;20:891–895. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1967)20:5<891::aid-cncr2820200550>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mir L.M., Tounekti O., Orlowski S. Bleomycin: revival of an old drug. Gen Pharmacol. 1996;27:745–748. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)02101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wynn T.A., Ramalingam T.R. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:1028–1040. doi: 10.1038/nm.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scotton C.J., Chambers R.C. Molecular targets in pulmonary fibrosis: the myofibroblast in focus. Chest. 2007;132:1311–1321. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biswas S.K., Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoshino T., Okamoto M., Sakazaki Y., Kato S., Young H.A., Aizawa H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines IL-18 and IL-1beta in bleomycin-induced lung injury in humans and mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:661–670. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0182OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luzina I.G., Kopach P., Lockatell V., Kang P.H., Nagarsekar A., Burke A.P. Interleukin-33 potentiates bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:999–1008. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0093OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baekkevold E.S., Roussigne M., Yamanaka T., Johansen F.E., Jahnsen F.L., Amalric F. Molecular characterization of NF-HEV, a nuclear factor preferentially expressed in human high endothelial venules. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:69–79. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63631-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitz J., Owyang A., Oldham E., Song Y., Murphy E., McClanahan T.K. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pichery M., Mirey E., Mercier P., Lefrancais E., Dujardin A., Ortega N. Endogenous IL-33 is highly expressed in mouse epithelial barrier tissues, lymphoid organs, brain, embryos, and inflamed tissues: in situ analysis using a novel Il-33-LacZ gene trap reporter strain. J Immunol. 2012;188:3488–3495. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lefrancais E., Roga S., Gautier V., Gonzalez-de-Peredo A., Monsarrat B., Girard J.P. IL-33 is processed into mature bioactive forms by neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1673–1678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115884109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carriere V., Roussel L., Ortega N., Lacorre D.A., Americh L., Aguilar L. IL-33, the IL-1-like cytokine ligand for ST2 receptor, is a chromatin-associated nuclear factor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:282–287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606854104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moussion C., Ortega N., Girard J.P. The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of endothelial cells and epithelial cells in vivo: a novel “alarmin”? PLoS One. 2008;3:e3331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu D., Jiang H.R., Kewin P., Li Y., Mu R., Fraser A.R. IL-33 exacerbates antigen-induced arthritis by activating mast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10913–10918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801898105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spits H., Di Santo J.P. The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:21–27. doi: 10.1038/ni.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oboki K., Ohno T., Kajiwara N., Arae K., Morita H., Ishii A. IL-33 is a crucial amplifier of innate rather than acquired immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18581–18586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003059107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurowska-Stolarska M., Stolarski B., Kewin P., Murphy G., Corrigan C.J., Ying S. IL-33 amplifies the polarization of alternatively activated macrophages that contribute to airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;183:6469–6477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurowska-Stolarska M., Kewin P., Murphy G., Russo R.C., Stolarski B., Garcia C.C. IL-33 induces antigen-specific IL-5+ T cells and promotes allergic-induced airway inflammation independent of IL-4. J Immunol. 2008;181:4780–4790. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komai-Koma M., Brombacher F., Pushparaj P.N., Arendse B., McSharry C., Alexander J. Interleukin-33 amplifies IgE synthesis and triggers mast cell degranulation via interleukin-4 in naive mice. Allergy. 2012;67:1118–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphreys N.E., Xu D., Hepworth M.R., Liew F.Y., Grencis R.K. IL-33, a potent inducer of adaptive immunity to intestinal nematodes. J Immunol. 2008;180:2443–2449. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Rooijen N., Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thepen T., Van Rooijen N., Kraal G. Alveolar macrophage elimination in vivo is associated with an increase in pulmonary immune response in mice. J Exp Med. 1989;170:499–509. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daniels C.E., Wilkes M.C., Edens M., Kottom T.J., Murphy S.J., Limper A.H. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF-beta and prevents bleomycin-mediated lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1308–1316. doi: 10.1172/JCI19603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molofsky A.B., Nussbaum J.C., Liang H.E., Van Dyken S.J., Cheng L.E., Mohapatra A. Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2013;210:535–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neill D.R., Wong S.H., Bellosi A., Flynn R.J., Daly M., Langford T.K. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–1370. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salmond R.J., Mirchandani A.S., Besnard A.G., Bain C.C., Thomson N.C., Liew F.Y. IL-33 induces innate lymphoid cell-mediated airway inflammation by activating mammalian target of rapamycin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1159–1166.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rot A., von Andrian U.H. Chemokines in innate and adaptive host defense: basic chemokinese grammar for immune cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:891–928. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strieter R.M., Gomperts B.N., Keane M.P. The role of CXC chemokines in pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:549–556. doi: 10.1172/JCI30562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lefrancais E., Cayrol C. Mechanisms of IL-33 processing and secretion: differences and similarities between IL-1 family members. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2012;23:120–127. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2012.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohtsuka Y., Lee J., Stamm D.S., Sanderson I.R. MIP-2 secreted by epithelial cells increases neutrophil and lymphocyte recruitment in the mouse intestine. Gut. 2001;49:526–533. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gur I., Or R., Segel M.J., Shriki M., Izbicki G., Breuer R. Lymphokines in bleomycin-induced lung injury in bleomycin-sensitive C57BL/6 and -resistant BALB/c mice. Exp Lung Res. 2000;26:521–534. doi: 10.1080/019021400750048072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roussel L., Farias R., Rousseau S. IL-33 is expressed in epithelia from patients with cystic fibrosis and potentiates neutrophil recruitment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:913–916. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yanaba K., Yoshizaki A., Asano Y., Kadono T., Sato S. Serum IL-33 levels are raised in patients with systemic sclerosis: association with extent of skin sclerosis and severity of pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:825–830. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- Sedhom M.A., Pichery M., Murdoch J.R., Foligne B., Ortega N., Normand S. Neutralisation of the interleukin-33/ST2 pathway ameliorates experimental colitis through enhancement of mucosal healing in mice. Gut. 2013;62:1714–1723. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhiguang X., Wei C., Steven R., Wei D., Wei Z., Rong M. Over-expression of IL-33 leads to spontaneous pulmonary inflammation in mIL-33 transgenic mice. Immunol Lett. 2010;131:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Stolarska M., Stolarski B., Kewin P., Murphy G., Corrigan C.J., Ying S. IL-33 amplifies the polarization of alternatively activated macrophages that contribute to airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;183:6469–6477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Stolarska M., Kewin P., Murphy G., Russo R.C., Stolarski B., Garcia C.C. IL-33 induces antigen-specific IL-5+ T cells and promotes allergic-induced airway inflammation independent of IL-4. J Immunol. 2008;181:4780–4790. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komai-Koma M., Xu D., Li Y., McKenzie A.N., McInnes I.B., Liew F.Y. IL-33 is a chemoattractant for human Th2 cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2779–2786. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen N., Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu C., Li Y., Li M., Liu X., McSharry C., Xu D. Anti-interleukin-33 inhibits cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation in mice. Immunology. 2013;138:76–82. doi: 10.1111/imm.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo R.C., Guabiraba R., Garcia C.C., Barcelos L.S., Roffe E., Souza A.L. Role of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 in bleomycin-induced pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:410–421. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0364OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmond R.J., Mirchandani A.S., Besnard A.G., Bain C.C., Thomson N.C., Liew F.Y. IL-33 induces innate lymphoid cell-mediated airway inflammation by activating mammalian target of rapamycin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1159–1166.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels C.E., Wilkes M.C., Edens M., Kottom T.J., Murphy S.J., Limper A.H. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF-beta and prevents bleomycin-mediated lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1308–1316. doi: 10.1172/JCI19603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Bao L., Deng W., Zhu H., Chen T., Lv Q. The mouse and ferret models for studying the novel avian-origin human influenza A (H7N9) virus. Virol J. 2013;10:253. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]