Abstract

The Men Androgen Inflammation Lifestyle Environment and Stress (MAILES) Study was established in 2009 to investigate the associations of sex steroids, inflammation, environmental and psychosocial factors with cardio-metabolic disease risk in men. The study population consists of 2569 men from the harmonisation of two studies: all participants of the Florey Adelaide Male Ageing Study (FAMAS) and eligible male participants of the North West Adelaide Health Study (NWAHS). The cohort has so far participated in three stages of the MAILES Study: MAILES1 (FAMAS Wave 1, from 2002–2005, and NWAHS Wave 2, from 2004–2006); MAILES2 (FAMAS Wave 2, from 2007–2010, and NWAHS Wave 3, from 2008–2010); and MAILES3 (a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) survey of all participants in the study, conducted in 2010). Data have been collected on a comprehensive range of physical, psychosocial and demographic issues relating to a number of chronic conditions (including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, arthritis and mental health) and health-related risk factors (including obesity, blood pressure, smoking, diet, alcohol intake and inflammatory markers), as well as on current and past health status and medication. Initial approaches or enquiries regarding the study can be made to either the principal investigator (gary.wittert@adelaide.edu.au) or the project coordinator (sean.martin@adelaide.edu.au).

Keywords: Men, cohort studies, longitudinal studies, chronic disease, risk factors

Why was the cohort set up?

In Australia, much information about population health comes from health surveys (population-based cross-sectional studies), and medical and hospital records. A major condition related to population health and which has reached pandemic proportions is obesity, and much remains to be learned regarding how it interacts with other key health variables. Obesity has been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD; ischaemic heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which are among the leading causes of disease globally, including Australia.1 The global burden of CVD is disproportionately higher in men than in women across low-, middle-, and high-income countries, which may be explained by gender-specific behavioural and biological risk factors. For instance, global prevalence estimates of smoking, physical inactivity and obesity are higher for men than for women across most regions.2 In men, low endogenous testosterone levels are associated with increased risk of T2DM3 and death from CVD.4

To date, there has not been a high-quality, prospective cohort study that adequately describes the aetiological roles of psychological, sex-steroid hormonal, inflammatory and behavioural risk factors simultaneously in the pathology of T2DM and CVD with control for confounding effects of demographic factors. The Men Androgen Inflammation Lifestyle Environment and Stress (MAILES) Study was established in 2009 to investigate the associations of sex steroids, inflammation, environmental and psychosocial factors with cardio-metabolic disease risk in men. The MAILES Study combined the populations of the Florey Adelaide Male Ageing Study (FAMAS) and the male population of the North West Adelaide Health Study (NWAHS), both of which are current, high-quality prospective cohort studies. Both the FAMAS and NWAHS are longitudinal cohort studies of randomly selected, community-dwelling adults in metropolitan Adelaide, Australia, between 2000 and 2010. Adelaide, the capital city of South Australia, has a population of 1.18 million people, representing approximately 73% of the total population of South Australia.5

The MAILES study is a partnership between investigators from The University of Adelaide, University of South Australia, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital (Woodville, South Australia), the Lyell McEwin Hospital (Elizabeth Vale), and the South Australian Health Department (SA Health). The study investigators constitute a research team from a range of disciplines including academic and clinical medicine, public health, epidemiology, social science and nursing, using both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies. The study was supported by a project grant received from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

The MAILES Study (N = 2569) harmonises two ongoing, prospectively followed cohorts of metropolitan Adelaide community-dwelling men aged 35–80 years at enrolment, with a known probability of selection and an extant data set with concomitant cost efficiency. The cohort size is sufficient to address the principal research questions of interest. For example, for a chronic non-communicable disease with a prevalence of 15% in the reference group, the sample size of the study would allow a minimum detectable relative risk of disease exceeding 1 in 1.22 and less than 1 in 0.81 between groups of participants with and without risk-factor exposure in multivariate analyses, with the assumed criteria of a: (i) sample power of 80%; (ii) use of a two-tailed test; (iii) a 5% chance of type 1 error; and (iv) an estimated risk-factor prevalence of 30% (conservative estimate for behavioural risk factors (e.g. physical inactivity).

The broad aim of MAILES is to determine the best set of explanatory variables for the development of T2DM and CVD, which could help inform national health-care policymakers and researchers in terms of the planning of treatment and preventive measures for these diseases. The comprehensive behavioural, biological, psychosocial and environmental data collected for this purpose will enable examination of the interacting effects of multiple factors in the development of T2DM and CVD, and the longitudinal design of the MAILES Study will establish their temporal sequence.

Who is in the cohort?

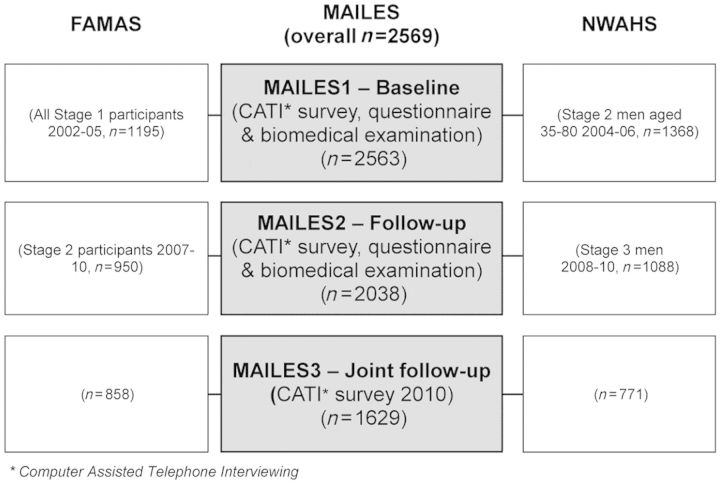

The MAILES Study comprises all FAMAS participants and a sub-set of men in the NWAHS (see Figure 1 for a composition of the population at each stage of the MAILES Study in terms of the proportions of FAMAS and NWAHS participants in the study population). The methods used in both FAMAS6,7 and NWAHS,8,9 including the validity of subject selection for achieving a representative population sample, have been described previously. Table 1 provides unweighted information about the demographic variables for the 2563 baseline participants in MAILES1, consisting of 1195 participants in FAMAS and 1368 in NWAHS.

Figure 1.

Composition of the study population at each stage of the MAILES Study, with the numbers of participants drawn from the respective stages of FAMAS and NWAHS

Table 1.

Profile of participants in the MAILES1 according to unweighted data

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||

| 35–44 | 573 | 22.4 |

| 45–54 | 652 | 25.4 |

| 55–64 | 645 | 25.2 |

| 65–74 | 487 | 19.0 |

| 75+ | 206 | 8.0 |

| Highest education level achieved | ||

| Secondary | 490 | 19.1 |

| Trade/apprenticeship/certificate/diploma | 1331 | 51.9 |

| Bachelor degree or higher | 295 | 11.5 |

| Not known/not stated | 447 | 17.4 |

| Annual gross household income | ||

| Up to $12 000 | 216 | 8.4 |

| $12 001–$20 000 | 318 | 12.4 |

| $20 001–$30 000 | 345 | 13.5 |

| $30 001–$40 000 | 283 | 11.0 |

| $40 001–$50 000 | 285 | 11.1 |

| $50 001–$60 000 | 270 | 10.5 |

| $60 001–$80 000 | 312 | 12.2 |

| >$80 000 | 382 | 14.9 |

| Not stated | 152 | 5.9 |

| Country of birth | ||

| Australia | 1679 | 65.5 |

| United Kingdom/Ireland | 484 | 18.9 |

| Europe | 290 | 11.3 |

| Asia/Other | 106 | 4.1 |

| Not stated | 4 | 0.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or living with partner | 1884 | 73.5 |

| Separated/divorced | 329 | 12.8 |

| Widowed | 97 | 3.8 |

| Never married | 167 | 6.5 |

| Not stated | 86 | 3.4 |

| Work status | ||

| Full-time employed | 1218 | 47.5 |

| Part time/casually employed | 234 | 9.1 |

| Unemployed | 68 | 2.7 |

| Home duties/retired | 818 | 31.9 |

| Student/other | 139 | 5.4 |

| Not stated | 86 | 3.4 |

| Receive pension from Social Security | ||

| Yes | 881 | 34.4 |

| No | 1592 | 62.1 |

| Don’t know/not stated | 90 | 3.5 |

| Total | 2563 | 100.0 |

Of the MAILES participants, 1564 (61.0%) provided information at all three stages of the study, with another 507 (19.8%) providing information at two stages. A number of weighted, selected socio-demographic, physical and general health/lifestyle variables in the MAILES1 population and the Men in Australia Telephone Survey (MATeS)10 are compared in Table 2. The data in MAILES1 were weighted to the 2008 Estimated Resident Population11 (the Australian Bureau of Statistics official measure of the Australian resident population) by age group, sex, region and probability of selection in the household, to ensure that the MAILES1 sample was representative of the population in the northern and western regions of Adelaide. The MATeS data were weighted according to age and the state of residence of each participant, using the 2001 Australian census age distribution for males.11 Of the two respective cohorts, men in the MAILES study were more likely not, among men of all ages, to have obtained any educational qualifications at the tertiary level or higher (12%; N = 308), as compared with men in the MATeS study (35%; N = 1769). This difference is most likely attributable to the over-representation of older men in the MAILES study,6,8 a common occurrence in studies requiring an in-person clinic visit.12 Also, MAILES participants were also more likely (42%; N = 1024) to have a greater waist circumference (WC), among men of all ages with a WC >102 cm as measured at clinic visits, than were participants in the MATeS (22%; N = 952). The smaller proportion of participants with a WC >102 cm observed in the MATeS study is most likely a result of the tendency of respondents to under-report body measures when these are requested in a telephone interview.13

Table 2.

Comparison of demographics and physical characteristics of MAILES1 (measured data) and MATeS (self-reported data) populations, according to weighted data

| MAILES1 (N = 2563) | MATeS (N = 5000) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Marital status | ||

| Married/defacto | 77% (1971) | 82% (1438) |

| Divorced/separated | 10% (265) | 9% (438) |

| Widowed | 3% (84) | 4% (198) |

| Never married | 6% (151) | 5% (249) |

| Refused/not stated | 4% (92) | 0% (3) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 59% (1520) | 63% (3141) |

| Looking for work/unemployed | 2% (64) | 2% (115) |

| Education level | ||

| Below upper-secondary education | 19% (486) | 28% (1378) |

| Upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education | 51% (1317) | 37% (1851) |

| Tertiary education | 12% (308) | 35% (1769) |

| Don’t know/not stated/refused | 18% (452) | 0% (4) |

| Nationality/ancestry | ||

| Born in Australia | 66% (1694) | 73% (3627) |

| Physical health | ||

| Mean body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.4 | 26.7 |

| Waist circumference <94 cm | 30% (730) | 57% (2470) |

| Waist circumference >102 cm | 42% (1024) | 22% (952) |

| Underweight (<20 kg/m2) | 1% (36) | 2% (111) |

| Overweight or obese (>25 kg/m2) | 66% (1686) | 64% (3167) |

| General health and lifestyle | ||

| Health status | ||

| Fair or poor self-assessed health status | 17% (441) | 17% (846) |

| Deterioration of health over past 12 months | 12% (310) | 13% (670) |

| Medication | ||

| High blood pressure | 25% (621) | 24% (1218) |

| High cholesterol | 20% (484) | 17% (857) |

| Cigarette smoking | ||

| Current smoker | 21% (531) | 18% (912) |

| Former smoker | 43% (1057) | 46% (2321) |

| Never smoked | 36% (888) | 35% (1769) |

How often have they been followed up?

The data in MAILES1 represent data collected in FAMAS at its participants' baseline clinic visit (Phase A: 2002–2003, and Phase B: 2004–2005), and in NWAHS at the first follow-up clinic visit (Stage 2: 2004–2006). The data in MAILES2 represent data collected at clinics approximately 5 years after these respective visits in the two studies (FAMAS Phase A: 2007–2008, and Phase B: 2009–2010; NWAHS Stage 3: 2008–2010). As described earlier, MAILES3 was a Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) survey conducted in August 2010. For the main biomedical stages (MAILES1 and MAILES2; see Table 3 for details), participants were contacted in approximately the same order in each respective stage, with the purpose of maintaining a consistent timing of follow-up across the different stages. Each of the major stages of the MAILES Study and telephone/questionnaire follow-up surveys allowed the tracking of items collected as part of the core data for the study to be monitored over time, whilst allowing other researchers to collect information on related research topics in collaborative projects.

Table 3.

Summary of data collection items from the MAILES Studya

| Phase | Measurements |

|---|---|

| Core (all 3 stages) | Condition: Cardiovascular disease |

| Risk factors: Alcohol consumption | |

| Demographics: Age (at various time-points), number of adults and children (age <18 and 18+ years) in household, pension/benefit status, marital status, postcode | |

| Repeated measures (2 stages) | Conditions: Respiratory (asthma, bronchitis, emphysema), cardiovascular disease (angina and other heart problems), arthritis, diabetes and type of diabetes, bone fractures, mental health (including anxiety, stress-related problems, depression [via the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies in Depression (CES_D; NWAHS)] and the Beck Depression Inventory [(BDI) 1A (FAMAS)]; prostate symptoms [International Prostate Symptom Scale (IPSS)] |

| Risk factors: Family history (diabetes, heart disease, stroke, osteoporosis), physical activity (National Health Survey), quality of life (SF36), smoking (including number of cigarettes currently or previously consumed, ages when first started and last gave up smoking), use of hypertension or cholesterol medication, blood pressure, height and weight (for BMI), waist and hip circumference, hand grip strength, blood sample [triglycerides, cholesterol [total, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL)], glucose, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), total testosterone, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), oestrone (E1), oestradiol (E2), sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), leutenising hormone (LH), prostate-specific antigen (PSA), high-sensitivity c-reactive protein (hs-CRP), Interleukin-6 (IL6), myeloperoxidase (MPO), tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), e-selectin (e-Sel) | |

| Demographics: Highest educational qualification achieved, annual gross household income, pension/benefit status, work status | |

| Other: health service utilisation, national government medical and pharmaceutical benefit scheme information | |

| Single measures | Conditions: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), mental health (PHQ for Anxiety and Depression), thyroid problem (including treatment and type of treatment), bladder cancer, impotence (GIR), enlarged prostate, prostate cancer symptoms (IPSS) and surgery, psychological distress (K10), osteoporosis, gout, sleep apnoea/symptoms, DEXA |

| Risk factors: Family history (high blood pressure), quality of life (AQOL), sleep, mastery and control, major health events, stress (support from family and friends, help from neighbours and religious beliefs), major lifetime stress events, nutrition [food frequency questionnaire (DQES)], self-perception of weight, blood sample (complete blood examination and biochemistry), urine sample (BPA), health literacy (Newest vital sign), physical activity (Active Australia, strength training), exposure to hazardous substances, length of time in hazardous industry, currently working in hazardous industry | |

| Demographics: Country of birth, year of arrival in Australia, Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander status, parents' country of birth, age at leaving school, number of biological children, quality of marital relationship, money situation, housing tenure, occupation (current/for most of life), number of hours in paid employment, father's occupation at respondent age 14, paid employment or self-employed, average hours per week worked, level of satisfaction with job, days off sick in last year, work and life balance, time of day for work, ever a shift worker, length of time as a shift worker, Australian Defence Force (ADF) membership and involvement in ADF conflict | |

| Other single measures: Carer status, private health insurance status, ownership of private motor vehicle, volunteer status, dental - own teeth and number of times per day teeth cleaned, social peers and society, vasectomy (and reversal), other pelvic surgery or radiotherapy |

aPlain text indicates self-reported measures; italicised text indicates both self-reported and biomedical measures; bold text indicates biomedical measures.

What has been measured?

The MAILES study is focused on a range of harmonised, self-reported and biomedically measured information from the baseline clinic visit for the study, regular self-reported telephone and questionnaire-based information, and clinical follow-up data. Data collected for the study include chronic medical conditions, risk factors, prior surgery, overall health status, quality of life, medication, anthropometric values, body composition, and demographic, psychosocial, and economic factors, as well as assay data derived from plasma and urine samples. Table 3 presents a summary of data items collected for the study.

Standardised, validated methods for measurement were used wherever possible. Clinic visits were made in the morning to maximise the efficiency of fasting blood-test results and for the comfort of the study participants. In addition to samples collected for immediate testing, an aliquot of whole blood was stored and DNA was extracted for later analysis. Participants were sent a letter detailing the results of their examinations in the study, with results that were outside the normal range being highlighted for their attention. With the consent of each participant, a copy of his results was also sent to his general practitioner for the practitioner’s information and possible follow-up. The interim telephone/questionnaire follow-up interviews help to maintain ongoing contact with the study participants and allow the updating of details relating to them.

All assays and scans in the MAILES Study were performed according to the highest standard available. Full examinations of body composition (including a specialised abdominal-region scan) and bone densitometry scans were done on a Prodigy Dual X-ray or DPX + Dual X-ray Absorptiometer (Lunar Radiation Corporation, Madison, Wisconsin, US) with Lunar software, with both densitometers having been shown to provide comparable measurements.14 Sex steroids [total testosterone (TT), dihydrotestosterone (DHT), estrone (E1), and estradiol (E2)] were measured in serum with an API-5000 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems/MDS SCIEX, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). The inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were as follows: 10.1% at 0.43 nmol/L, 11.1% at 1.66 nmol/L, and 4% at 8.17 nmol/L for TT; 13.2% at 0.43 nmol/L, 8.0% at 1.68 nmol/L, and 7.4% at 8.37 nmol/L for DHT; 14.1% at 23 pmol/L, 4.4% at 83 pmol/L, and 6.3% at 408 pmol/L for E1; and 9.2% at 22 pmol/L, 2.2% at 83 pmol/L, and 6.1% at 411 pmol/L for E2. Inflammatory markers [high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP); tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α); interleukin-6 (IL-6); myeloperoxidase (MPO); and e-selectin (e-Sel)] were quantitated with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Cobas auto-analyser Roche Diagnostics, Florham Park, New Jersey, US). The inter-assay CVs were 2.1% for hsCRP, 10.6% for TNF-α, 7.8% for IL-6, 7.8% for MPO, and 7.9% for e-Sel. Exposure to bisphenol-A (BPA) was determined in collected urine samples by isotope dilution liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). The inter-assay CVs for BPA were 5.5% at 2.87 ng/mL, 5.7% at 46 ng/mL, and 10.1% at 81 ng/mL.

Data linkage with the Australian National Death Index register provides cause-of-death information. Linked information about individual pharmaceutical and medical benefits is supplied by Medicare, Australia's universal system for financing health services provided by private physicians and public hospitals, as well as some additional health-related costs. It collects national data on medical provider service claims for payment purposes through the Medicare Benefit Schedule, and has been shown to be more accurate than self-reported service utilisation data.15,16 Medicare also collects national data on medications prescribed through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

Most Australians have either an individual or family Medicare number, which is used on each occasion of medical care or hospitalisation. Participants in the MAILES Study were asked to provide consent for release by Medicare of their retrospective and prospective medical and hospital-related information for analyses of their health economic-related and pharmaceutical data.

In addition to the MAILES Study itself, two sub-studies have been undertaken. The first sub-study investigated the prevalence of sleep disorders from 2010 to 2012 through home-based polysomnography (using the Embletta X100 (Embla Systems, Thornton, Colorado, US), a portable sleep recorder and Type III device as defined by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine) and the following three validated, sleep-related questionnaires based on self-reported data: (i) the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index17; (ii) the STOP Questionnaire18 (Snoring, Tiredness during daytime, Observed apnoea and high blood Pressure); and (iii) the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.19 The second sub-study is currently exploring members of the ‘Baby Boomer’ generation, defined as persons born from 1946–1965 inclusive, for specific generational and more generic patterns and influences regarding obesity-related behaviours and work-force participation.

What is the anticipated attrition?

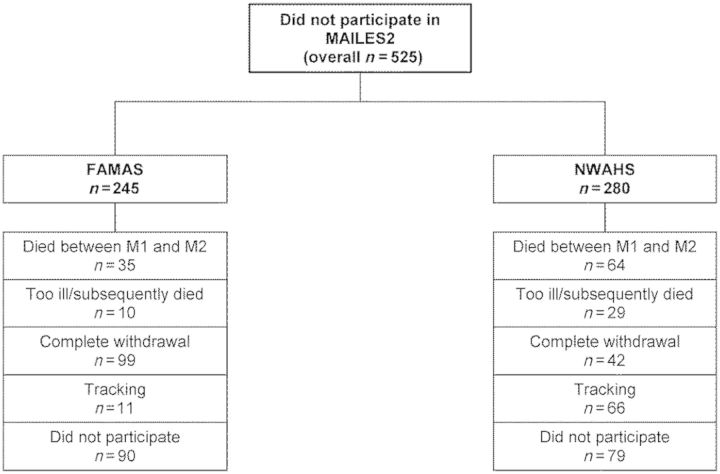

Tables 4–6 present the demographic characteristics, chronic conditions and risk-factor profile of participants who took part in both MAILES1 and MAILES2 (N = 2038), in comparison with the corresponding data for participants who took part only in MAILES1 (i.e. non participants in MAILES2; N = 525). Of these non-participants, 99 died, 39 were too ill to participate in MAILES2, 141 withdrew completely before the beginning of MAILES2, 77 were unable to be tracked due to changes in contact details, and 169 refused to take part in MAILES2 due to work-related and personal reasons.

Table 4.

Demographic profile of participants only in MAILES1 as compared to those of participants in MAILES1 and MAILES2

| Participated MAILES1 and MAILES2 |

Participated in MAILES1 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | % | 95% CI | N | % | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age group (years) | 0.000 | |||||||

| 35–44 | 446 | 21.9 | (20.1–23.7) | 127 | 24.2 | (20.7–28.0) | ||

| 45–54 | 554 | 27.2 | (25.3–29.2) | 98 | 18.7 | (15.6–22.2) | * | |

| 55–64 | 537 | 26.3 | (24.5–28.3) | 108 | 20.6 | (17.3–24.2) | * | |

| 65–74 | 382 | 18.7 | (17.1–20.5) | 105 | 20.0 | (16.8–23.6) | ||

| 75+ | 119 | 5.8 | (4.9–6.9) | 87 | 16.6 | (13.6–20.0) | * | |

| Highest education level obtained | 0.000 | |||||||

| Secondary | 383 | 18.8 | (17.2–20.5) | 107 | 20.4 | (17.2–24.0) | ||

| Trade/apprenticeship/certificate/diploma | 1081 | 53.0 | (50.9–55.2) | 250 | 47.6 | (43.4–51.9) | * | |

| Bachelor degree or higher | 262 | 12.9 | (11.5–14.4) | 33 | 6.3 | (4.5–8.7) | * | |

| Not known/not stated | 312 | 15.3 | (13.8–16.9) | 135 | 25.7 | (22.2–29.6) | * | |

| Annual gross household income | 0.000 | |||||||

| Up to $12 000 | 144 | 7.1 | (6–8.3) | 72 | 13.7 | (11.0–16.9) | * | |

| $12 001–$20 000 | 232 | 11.4 | (10.1–12.8) | 86 | 16.4 | (13.5 - 19.8) | * | |

| $20 001–$30 000 | 272 | 13.3 | (11.9–14.9) | 73 | 13.9 | (11.2–17.1) | ||

| $30 001–$40 000 | 237 | 11.6 | (10.3–13.1) | 46 | 8.8 | (6.6–11.5) | ||

| $40 001–$50 000 | 239 | 11.7 | (10.4–13.2) | 46 | 8.8 | (6.6–11.5) | ||

| $50 001–$60 000 | 231 | 11.3 | (10.0–12.8) | 39 | 7.4 | (5.5–10.0) | * | |

| $60 001–$80 000 | 273 | 13.4 | (12.0–14.9) | 39 | 7.4 | (5.5–10.0) | * | |

| >$80 000 | 333 | 16.3 | (14.8–18.0) | 49 | 9.3 | (7.1–12.1) | * | |

| Not stated | 77 | 3.8 | (3–4.7) | 75 | 14.3 | (11.6–17.5) | * | |

| Country of birth | 0.001 | |||||||

| Australia | 1365 | 67.0 | (64.9–69.0) | 314 | 59.8 | (55.6–63.9) | * | |

| United Kingdom/Ireland | 385 | 18.9 | (17.3–20.6) | 99 | 18.9 | (15.7–22.4) | ||

| Europe | 205 | 10.1 | (8.8–11.4) | 85 | 16.2 | (13.3–19.6) | * | |

| Asia/Other | 81 | 4.0 | (3.2–4.9) | 25 | 4.8 | (3.2–6.9) | ||

| Not stated | 2 | 0.1 | (0–0.4) | 2 | 0.4 | (0.1–1.4) | ||

| Marital status | 0.000 | |||||||

| Married or living with partner | 1556 | 76.3 | (74.5–78.1) | 328 | 62.5 | (58.3–66.5) | * | |

| Separated/Divorced | 250 | 12.3 | (10.9–13.8) | 79 | 15.0 | (12.2–18.4) | ||

| Widowed | 70 | 3.4 | (2.7–4.3) | 27 | 5.1 | (3.6–7.4) | ||

| Never married | 123 | 6.0 | (5.1–7.2) | 44 | 8.4 | (6.3–11.1) | ||

| Not stated | 39 | 1.9 | (1.4–2.6) | 47 | 9.0 | (6.8–11.7) | * | |

| Work status | 0.000 | |||||||

| Full time employed | 1053 | 51.7 | (49.5–53.8) | 165 | 31.4 | (27.6–35.5) | * | |

| Part time/Casual employed | 190 | 9.3 | (8.1–10.7) | 44 | 8.4 | (6.3–11.1) | ||

| Unemployed | 49 | 2.4 | (1.8–3.2) | 19 | 3.6 | (2.3–5.6) | ||

| Home duties/Retired | 607 | 29.8 | (27.8–31.8) | 211 | 40.2 | (36.1–44.4) | * | |

| Student/Other | 98 | 4.8 | (4–5.8) | 41 | 7.8 | (5.8–10.4) | * | |

| Not stated | 41 | 2.0 | (1.5–2.7) | 45 | 8.6 | (6.5–11.3) | * | |

| Receive pension from Social Security | 0.000 | |||||||

| Yes | 641 | 31.5 | (29.5–33.5) | 240 | 45.7 | (41.5–50.0) | * | |

| No | 1353 | 66.4 | (64.3–68.4) | 239 | 45.5 | (41.3–49.8) | * | |

| Don’t know/Not stated | 44 | 2.2 | (1.6–2.9) | 46 | 8.8 | (6.6–11.5) | * | |

| Total | 2038 | 100.0 | 525 | 100.0 | ||||

Asterisks indicate statistically significantly results within variables (P ≤ 0.05).

Table 5.

Chronic-condition profile of participants only in MAILES1 as compared to that of participants in MAILES1 and MAILES2

| MAILES 1 and 2 |

MAILES1 only |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | % | 95% CI | N | % | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Diabetes | 0.000 | |||||||

| No | 1811 | 88.9 | (87.4–90.2) | 407 | 77.5 | (73.8–80.9) | * | |

| Yes | 193 | 9.5 | (8.3–10.8) | 74 | 14.1 | (11.4–17.3) | * | |

| Don't know/not stated | 34 | 1.7 | (1.2–2.3) | 44 | 8.4 | (6.3–11.1) | * | |

| Asthma | 0.000 | |||||||

| No | 1742 | 85.5 | (83.9–86.9) | 425 | 81.0 | (77.4–84.1) | * | |

| Yes | 262 | 12.9 | (11.5–14.4) | 56 | 10.7 | (8.3–13.6) | ||

| Don't know/not stated | 34 | 1.7 | (1.2–2.3) | 44 | 8.4 | (6.3–11.1) | * | |

| Cardiovascular disease: angina | 0.012 | |||||||

| No | 1924 | 94.4 | (93.3–95.3) | 481 | 91.6 | (88.9–93.7) | * | |

| Yes | 109 | 5.3 | (4.5–6.4) | 39 | 7.4 | (5.5–10.0) | ||

| Don't know/not stated | 5 | 0.2 | (0.1–0.6) | 5 | 1.0 | (0.4–2.2) | * | |

| Cardiovascular disease: all | 0.002 | |||||||

| No | 1835 | 90.0 | (88.7–91.3) | 449 | 85.5 | (82.3–88.3) | * | |

| Yes | 198 | 9.7 | (8.5–11.1) | 71 | 13.5 | (10.9–16.7) | * | |

| Don't know/not stated | 5 | 0.2 | (0.1–0.6) | 5 | 1.0 | (0.4–2.2) | * | |

| Osteoarthritis | 0.054 | |||||||

| No | 1868 | 91.7 | (90.4–92.8) | 473 | 90.1 | (87.2–92.4) | ||

| Yes | 165 | 8.1 | (7–9.4) | 47 | 9.0 | (6.8–11.7) | ||

| Don't know/not stated | 5 | 0.2 | (0.1–0.6) | 5 | 1.0 | (0.4–2.2) | * | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.055 | |||||||

| No | 1956 | 96.0 | (95.0–96.7) | 497 | 94.7 | (92.4–96.3) | ||

| Yes | 77 | 3.8 | (3–4.7) | 23 | 4.4 | (2.9–6.5) | ||

| Don't know/not stated | 5 | 0.2 | (0.1–0.6) | 5 | 1.0 | (0.4–2.2) | * | |

| Mental health: anxiety | 0.055 | |||||||

| No | 1890 | 92.7 | (91.8–94.0) | 479 | 91.2 | (88.5–93.4) | ||

| Yes | 143 | 7.0 | (6–8.2) | 41 | 7.8 | (5.8–10.4) | ||

| Don't know/not stated | 5 | 0.2 | (0–0.2) | 5 | 1.0 | (0.4–2.2) | * | |

| Mental health: depression | 0.001 | |||||||

| No | 1848 | 9.7 | (89.3–91.9) | 451 | 85.9 | (82.7 –88.6) | * | |

| Yes | 185 | 9.1 | (7.9–10.4) | 69 | 13.1 | (10.5–16.3) | * | |

| Don't know/not stated | 5 | 0.2 | (0.1–0.6) | 5 | 1.0 | (0.4–2.2) | * | |

| Total | 2038 | 100.0 | 525 | 100.0 | ||||

Asterisks indicate statistically significantly results within variables (P ≤ 0.05).

Table 6.

General health and risk-factor profile of participants only in MAILES1 as compared to those of participants in MAILES1 and MAILES2

| MAILES1 and MAILES2 |

MAILES1 only |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | % | 95% CI | N | % | 95% CI | P-value | |

| SF1 | 0.000 | |||||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 1689 | 82.9 | (81.2–84.4) | 346 | 65.9 | (61.7–69.8) | * | |

| Fair/poor | 311 | 15.3 | (13.8–16.9) | 135 | 25.7 | (22.2–29.6) | * | |

| Not stated | 38 | 1.9 | (1.4–2.5) | 44 | 8.4 | (6.3–11.1) | * | |

| Body mass index | 0.000 | |||||||

| Underweight <20 | 28 | 1.4 | (1.00–2.00) | 6 | 1.1 | (0.5–2.5) | ||

| Normal 20–25 | 377 | 18.5 | (16.9–20.2) | 107 | 20.4 | (17.2–24.0) | ||

| Overweight & obese 25+ | 1588 | 77.9 | (76.1–79.7) | 356 | 67.8 | (63.7–71.7) | * | |

| Not measured | 45 | 2.2 | (1.7–2.9) | 56 | 10.7 | (8.3–13.6) | * | |

| Waist circumference <94 cm | 0.000 | |||||||

| Waist circum <94 cm | 580 | 28.5 | (26.5–30.5) | 129 | 24.6 | (21.1–28.4) | ||

| Waist circum 94+ cm | 1407 | 69.0 | (67.0–71.0) | 341 | 65.0 | (60.8–68.9) | ||

| Not measured | 51 | 2.5 | (1.9–3.3) | 55 | 10.5 | (8.1–13.4) | * | |

| Waist circumference >102 cm | 0.000 | |||||||

| Waist circum <102 cm | 1139 | 55.9 | (53.7–58.0) | 259 | 49.3 | (45.1–53.6) | * | |

| Waist circum 102+ cm | 848 | 41.6 | (39.5–43.8) | 211 | 40.2 | (36.1–44.4) | ||

| Not measured | 51 | 2.5 | (1.9–3.3) | 55 | 10.5 | (8.1–13.4) | * | |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.000 | |||||||

| Normal waist hip ratio (≤1.0 male) | 1536 | 75.4 | (73.5–77.2) | 350 | 66.7 | (62.5–70.6) | * | |

| High waist hip ratio (>1.0 male) | 451 | 22.1 | (20.4–24.0) | 119 | 22.7 | (19.3–26.4) | ||

| Not stated | 51 | 2.5 | (1.9–3.3) | 56 | 10.7 | (8.3–13.6) | * | |

| Smoking status | 0.000 | |||||||

| Non-smoker | 766 | 37.6 | (35.5–39.7) | 126 | 24.0 | (20.5–27.8) | * | |

| Ex-smoker | 845 | 41.5 | (39.3–43.6) | 212 | 40.4 | (36.3–44.6) | ||

| Current smoker | 378 | 18.5 | (16.9–20.3) | 137 | 26.1 | (22.5–30.0) | * | |

| Not stated | 49 | 2.4 | (1.8–3.2) | 50 | 9.5 | (7.3–12.3) | * | |

| Total | 525 | 100.0 | 2038 | 100.0 | ||||

Asterisks indicate statistically significantly results within variables (P ≤ 0.05).

An examination of demographic characteristics of these non-respondents (as compared with that of respondents) shows that they were more likely to be older; have not undertaken further training in skills or education; have a lower annual gross household income; have been born in Europe; be undertaking home duties or be retired; be a student or other; be in receipt of a government pension; or to have chosen not to disclose their level of education, income level, or marital, occupational or pension status.

With regard to chronic conditions, non-respondents in MAILES2 were more likely than respondents to report that they had been told by a physician that they had diabetes, CVD, or depression, or to either not know or to not disclose their chronic-disease status.

With regard to their self-reported general health and smoking status, non-respondents in MAILES2 were more likely than respondents to report that they had poorer health and were current smokers or to not to provide information about these factors. Regarding measured health-related risk factors, non-respondents were less likely than respondents to be overweight or obese, or to have central adiposity and a high waist-to-hip ratio, but more likely to have been unwilling or unable to have their height, weight, WC, and hip circumference measured.

What has been found? Key findings and publications

The results described below are based on analysis of the cohort at the baseline MAILES1 (2002–2006, N = 2563) and MAILES2 (2007–2010, N = 2039). These data have been age-standardised to the 2011 Australian Census (South Australian males).

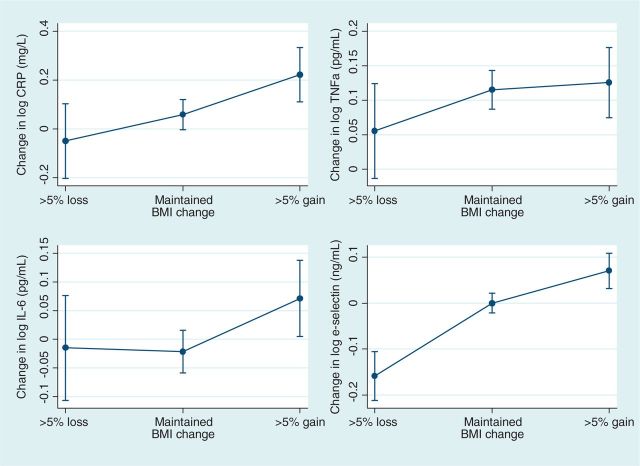

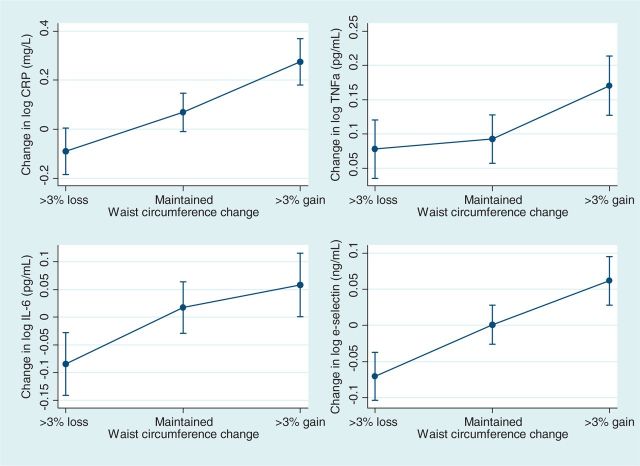

As already highlighted, a major strength of the MAILES Study is its ability to examine the relationship between inflammatory markers and other variables of interest over time. In his review article, Ridker emphasises that more than 20 large-scale prospective studies have shown that hs-CRP is a predictor of cardiovascular events as well as of incident hypertension and diabetes.20 Other studies highlight the link between elevated hs-CRP and obesity (both body mass index (BMI) and abdominal adiposity), as well as the association of these two risk factors with other elevated proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, which are involved in systemic inflammation.21,22 One such study23 posited that elevated levels of hs-CRP may be reversible with weight loss. Further evidence of this was provided in the MAILES study with an analysis of the change in the levels of these three inflammatory markers, together with that of e-Sel. Because the distribution of each of these inflammatory markers was skewed, the results were log-transformed to normalise the data.

Figures 3 and 4 present the marginal mean changes in concentrations of hs-CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, and e-Sel from MAILES1 to MAILES2 according to the corresponding changes first in BMI (according to the three criteria of: lost >5%, maintained BMI, gained >5%) and in WC (lost >3%, maintained WC, gained >3%). Values were adjusted for age. There was a similar pattern observed for most of the markers, with a trend observed for decreases in body mass (of 5%) or WC (of 3%) to be associated with lower levels of each inflammatory marker. The exception was for IL-6, which showed minimal change with a decrease in BMI.

Figure 2.

Loss to follow-up of study participants from MAILES1 to MAILES2

Figure 3.

Marginal mean level of hs-CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, and e-Sel according to BMI status from MAILES1 (2002–2006) to MAILES2 (2007–2010). Data are presented as marginal mean estimates ± 95% CIs. All dependent variables were log transformed

Figure 4.

Changes in marginal mean levels of hs-CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, and e-Sel according to waist circumference from MAILES1 (2002–2006) to MAILES2 (2007–2010). Data are presented as marginal mean estimates ± 95% CIs. All dependent variables were log transformed

With regard to BMI, most participants maintained this at a constant level (N = 1242, 67.4%), with approximately one in five gaining more than 5% (N = 391, 21.2%) and 1 in 10 losing more than 5% (N = 209, 11.4%) of their BMI from MAILES1 to MAILES2. The change in distribution of BMI can be seen from the proportions of participants who lost (N = 527, 28.7%) or gained (N = 540, 29.4%) more than 3% of their WC from the first to the second of these two stages of the study, as well as from the proportion of participants who maintained their WC (N = 770, 41.9%). An examination of age-standardised levels showed an overall increase in the proportion of obesity (BMI 30+) from 31.1% in MAILES1 to 32.6% in MAILES2, which occurred mainly in the middle-aged group of participants (from 8.5% to 9.3% for those aged 45–54 years), but with a corresponding decline across all ages in the risk of developing metabolic complications associated with obesity as measured by WC in Caucasian men (from 28.1% to 26.9% for increased risk, WC ≥94 cm, and from 42.6% to 40.1% for substantially increased risk, WC ≥102 cm24).

The proportion of MAILES participants who self-reported a number of chronic conditions (e.g. diabetes, asthma, CVD and specifically angina, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis; and mental disorders, consisting specifically of anxiety and depression) in MAILES1 and MAILES2 is shown in Table 7. The prevalence of two primarily obesity-related conditions (diabetes and osteoarthritis) increased markedly from MAILES1 to MAILES2, particularly with regard to diabetes in the younger age groups (0.6%–1.2%), an increase disproportionate to these groups’ levels of obesity.

Table 7.

Age-standardised proportion of MAILES participants with self-reported chronic conditions in MAILES1 and MAILES2

| MAILES1 (N = 2553) |

MAILES2 (N = 1988) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | (95% CI) | N | % | (95% CI) | |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| 35–44 years | 13 | 0.6 | 20 | 1.2 | ||

| 45–54 years | 38 | 1.5 | 42 | 2.0 | ||

| 55–64 years | 77 | 2.8 | 92 | 4.0 | ||

| 65+ years | 139 | 5.5 | 108 | 6.0 | ||

| Overall | 267 | 10.4 | (9.3–11.6)a | 262 | 13.1 | (11.78–14.7)a |

| Asthma | ||||||

| 35–44 years | 76 | 3.5 | 55 | 3.3 | ||

| 45–54 years | 80 | 3.2 | 77 | 3.8 | ||

| 55–64 years | 84 | 3.0 | 66 | 2.9 | ||

| 65+ years | 78 | 3.1 | 58 | 3.2 | ||

| Overall | 318 | 12.8 | (11.2–13.8)a | 256 | 13.1 | (11.5–14.4)a |

| Cardiovascular disease: angina | ||||||

| 35–44 years | 2 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.1 | ||

| 45–54 years | 14 | 0.6 | 13 | 0.6 | ||

| 55–64 years | 44 | 1.5 | 27 | 1.2 | ||

| 65+ years | 88 | 3.4 | 78 | 4.3 | ||

| Overall | 148 | 5.6 | (4.8–6.6) | 120 | 6.2 | (5.1–7.2) |

| Cardiovascular disease: all | ||||||

| 35–44 years | 9 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.3 | ||

| 45–54 years | 29 | 1.2 | 27 | 1.3 | ||

| 55–64 years | 71 | 2.5 | 47 | 1.9 | ||

| 65+ years | 160 | 6.2 | 159 | 6.2 | ||

| Overall | 269 | 10.3 | (9.1–11.5) | 235 | 9.6 | (8.3–10.9) |

| Osteoarthritis | ||||||

| 35–44 years | 12 | 0.5 | 17 | 1.0 | ||

| 45–54 years | 38 | 1.5 | 42 | 2.0 | ||

| 55–64 years | 63 | 2.2 | 75 | 3.2 | ||

| 65+ years | 99 | 3.9 | 87 | 4.8 | ||

| Overall | 212 | 8.1 | (7.1–9.3) | 221 | 11.0 | (9.7–12.5) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ||||||

| 35–44 years | 6 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.3 | ||

| 45–54 years | 19 | 0.7 | 14 | 0.7 | ||

| 55–64 years | 34 | 1.2 | 24 | 1.0 | ||

| 65+ years | 41 | 1.6 | 30 | 1.7 | ||

| Overall | 100 | 3.8 | (3.1–4.6) | 74 | 3.7 | (3.0–4.6) |

| Mental health: anxiety | ||||||

| 35–44 years | 31 | 1.3 | 21 | 1.2 | ||

| 45–54 years | 53 | 2.1 | 46 | 2.3 | ||

| 55–64 years | 66 | 2.3 | 44 | 2.0 | ||

| 65+ years | 34 | 1.3 | 23 | 1.4 | ||

| Overall | 184 | 7.1 | (6.1–8.1) | 134 | 7.0 | (5.9–8.2)a |

| Mental health: depression | ||||||

| 35–44 years | 55 | 2.4 | 39 | 2.3 | ||

| 45–54 years | 67 | 2.7 | 59 | 2.9 | ||

| 55–64 years | 89 | 3.1 | 47 | 2.2 | ||

| 65+ years | 43 | 1.7 | 26 | 1.6 | ||

| Overall | 254 | 9.8 | (8.7–11.0) | 171 | 9.0 | (7.8–10.4)a |

aDiabetes and asthma, M1, N = 2485: diabetes, M2, N = 1964; asthma, M2, N = 1951; anxiety and sepression, M2, N = 1865.

Both the individual FAMAS and NWAHS studies have been extensively described, with 43 FAMAS papers and 88 NWAHS papers published or submitted. Full details of all papers are provided at the MAILES study website www.adelaide.edu.au/mailes.

What are the main strengths and weaknesses?

The MAILES Study’s main strength comes from the value-added benefit of combining selected participants from two existing high-quality cohort studies to provide a wealth of measured and self-reported information about multiple chronic conditions, together with the data collected on a wide range of biomedical and socio-demographic variables. Other benefits of the study are the storage of blood and urine samples for future research projects and the collection and processing of DNA. The MAILES study has a sound epidemiological base, a comparatively large sample of randomly selected community-dwelling men and a high overall response rate, allowing its findings to be generalised to the broader population.

Further, the cohort design of the MAILES Study and the detailed data it provides about health-service utilisation allow description and targeting, for the purposes of health planning and promotion, of the characteristics of populations either at risk for particular chronic conditions and/or risk factors, or in whom these conditions or factors are currently unidentified. Slight to moderate differences in questions asked and response categories used in the MAILES Study has proven somewhat problematic in some instances, but is considered to have been unavoidable because of differences in the main focus of FAMAS and NWAHS.

Additional strengths of the study include its ability to perform repeat assessments of core conditions, whilst incorporating cross-sectional research on various health-related subjects. From a methodological viewpoint, the study allows the examinination of issues such as refusal to participate and respondent bias.

The limitations of the MAILES Study include its reliance on self-reported information for some lifestyle and medical factors. Moreover, although the study participants were representative of its target population, they were also predominantly Caucasian, aged 35–80 years (at recruitment) and community-dwelling. Consequently, these findings may not be applicable to other population groups. Although attrition remains comparatively low for a study of this type (approximately 2.7% of participants per year of study), this remains an issue being actively monitored for the possible introduction of any systematic biases. It could also be argued that an exclusively male cohort may limit the applicability of findings to the broader population, but the dearth of male ageing studies in Australia seems to warrant such an approach. In addition, the MAILES Study is one of the few ageing studies to incorporate younger participants in a cohort design.

Can I get access to the data? Where can I find out more?

Initial approaches or enquiries regarding the MAILES Study can be made to either the principal investigator (gary.wittert@adelaide.edu.au) or the project coordinator (sean.martin@adelaide.edu.au). All applications for access to data and collaboration are considered by the MAILES Executive and Investigator Committee, following the completion and submission of a MAILES data request and manuscript proposal form. Further information about the MAILES study is available at www.adelaide.edu.au/mailes.

Funding

Project Grant APP627227 from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful for the generosity of the cohort participants in giving their time and effort to the study. The study team also is very appreciative of the work of the clinic, recruiting, and research- support staff for their substantial contribution to the success of the study.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Key Messages.

Weight gain (becoming obese or having an increased waist circumference) results in an increase in inflammatory markers, and conversely, weight loss results in their decrease. Weight losses of small magnitude therefore translate into large benefits in health.

There was an increase between MAILES1 and MAILES2 in the (age-standardised) prevalence of: diabetes (10.4%–13.1%); osteoarthritis (8.1%–11.0%); and angina (5.6%–6.2%) across all age groups.

There was relative stability or a slight decrease between the two time-points in the (age-standardised) prevalence of: asthma (12.8%–13.1%); rheumatoid arthritis (3.8%–3.7%); anxiety (7.1% to 7.0%); overall cardiovascular disease (10.2%–9.6%); and depression (9.8%–9.0%).

Together these data highlight the wide-ranging impact of obesity on the health status of men, and afford the opportunity to look at the detailed interaction between biological and psychosocial factors in relation to several specific disease states.

References

- 1.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2010. Australia's Health 2010. Australia's Health no. 12. Cat. no. AUS 122. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendis S, Puska P, Norrving B, editors. World Health Organization. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241564373_eng.pdf (19 March 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding EL, Song Y, Malik VS, Liu S. Sex differences of endogenous sex hormones and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:1288–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.11.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araujo AB, Dixon JM, Suarez EA, Murad MH, Guey LT, Wittert GA. Clinical review: rndogenous testosterone and mortality in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3007–19. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2011. SA Stats, June 2011. Cat. No. 1345.4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin S, Haren M, Taylor A, Middleton S, Wittert G members of the Florey Adelaide Male Ageing Study. Cohort profile: The Florey Adelaide Male Ageing Study (FAMAS) Int J Epidemiol. 2008;36:302–06. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin SA, Haren MT, Middleton SM, Wittert GA members of the Florey Adelaide Male Ageing Study (FAMAS) The Florey Adelaide Male Ageing Study (FAMAS): design, procedures and participants. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant JF, Taylor AW, Ruffin RE, et al. Cohort profile: The North West Adelaide Health Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;38:1479–86. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant J, Chittleborough C, Taylor A, et al. The North West Adelaide Health Study: Detailed methods and baseline segmentation of a cohort for selected chronic diseases. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2006;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holden CA, McLachlan RI, Pitts M, et al. Men in Australia Telephone Survey (MATeS): a national survey of the reproductive health and concerns of middle-aged and older Australian men. Lancet. 2005;366:218–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66911-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2010. Population by age and sex: Regions of Australia, 2008. Cat. No. 3235.0. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brilleman SL, Pachana NA, Dobson AJ. The impact of attrition on the representativeness of cohort studies of older people. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shields M, Connor Gorber S, Tremblay MS. Estimates of obesity based on self-report versus direct measures. Health Rep. 2008;2:61–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazess RB, Hanson JA, Payne R, Nord R, Wilson M. Axial and total-body bone densitometry using a narrow-angle fan-beam. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:158–66. doi: 10.1007/PL00004178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Med1 Pollicino C, Viney R, Haas M. Measuring health system resource use for economic evaluation: a comparison of data sources. Aust Health Rev. 2002;25:171–78. doi: 10.1071/ah020171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Med2 McCallum J, Lonergan J, Raymond C. Canberra: National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, The Australian National University; 1993. The NCEPH record linkage pilot study: A preliminary examination of individual Health Insurance Commission records with linked data sets. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, Chung SA, Vairavanathan S, Islam S, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812–21. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816d83e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–45. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridker PM. C-reactive protein and the prediction of cardiovascular events among those at intermediate risk: moving an inflammatory hypothesis toward consensus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan JC, Cheung JCK, Stehouwer CDA, et al. The central roles of obesity-associated dyslipidaemia, endothelial activation and cytokines in the metabolic syndrome–an analysis by structural equation modelling. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:994–1008. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cartier A, Cote M, Lemieux I, et al. Age-related differences in inflammatory markers in men: contribution of visceral adiposity. Metabolism. 2009;58:1452–58. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks GC, Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS. Relation of C-reactive protein to abdominal adiposity. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Health and Medical Research Council. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults. Available from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/7AF116AFD4E2EE3DCA256F190003B91D/$File/adults.pdf (19 March 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]