Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE:

Various proposals have been made to redesign well-child care (WCC) for young children, yet no peer-reviewed publication has examined the evidence for these. The objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review on WCC clinical practice redesign for children aged 0 to 5 years.

METHODS:

PubMed was searched using criteria to identify relevant English-language articles published from January 1981 through February 2012. Observational studies, controlled trials, and systematic reviews evaluating efficiency and effectiveness of WCC for children aged 0 to 5 were selected. Interventions were organized into 3 categories: providers, formats (how care is provided; eg, non–face-to-face formats), and locations for care. Data were extracted by independent article review, including study quality, of 3 investigators with consensus resolution of discrepancies.

RESULTS:

Of 275 articles screened, 33 met inclusion criteria. Seventeen articles focused on providers, 13 on formats, 2 on locations, and 1 miscellaneous. We found evidence that WCC provided in groups is at least as effective in providing WCC as 1-on-1 visits. There was limited evidence regarding other formats, although evidence suggested that non-face-to-face formats, particularly web-based tools, could enhance anticipatory guidance and possibly reduce parents’ need for clinical contacts for minor concerns between well-child visits. The addition of a non–medical professional trained as a developmental specialist may improve receipt of WCC services and enhance parenting practices. There was insufficient evidence on nonclinical locations for WCC.

CONCLUSIONS:

Evidence suggests that there are promising WCC redesign tools and strategies that may be ready for larger-scale testing and may have important implications for preventive care delivery to young children in the United States.

KEY WORDS: well-child care, practice redesign, patient-centered medical home

Well-child care (WCC) during infancy and early childhood provides a critical opportunity to address important social, developmental, behavioral, and health issues for children. Ideally, WCC provides parents with the knowledge and confidence necessary to ensure that their children meet their full developmental potential and optimal health status. In our current WCC system, this opportunity is often missed; many children either do not receive these important services or receive low-quality services.1,2 Many parents leave visits with unaddressed psychosocial, developmental, and behavioral concerns,3–5 and many children do not receive recommended screening for developmental delay.6,7

WCC in the United States is structured so that the clinician (pediatrician, family physician, or nurse practitioner [NP]) is expected to provide nearly all recommended services in 13 face-to-face visits during the first 5 years of life. The number of recommended services has expanded beyond what can be accomplished in the typical visit, perhaps contributing to the wide variation in the quantity and quality of services received.8–10 Pediatric practices interested in changing how they provide WCC can turn to the pediatric literature for a variety of clinical practice redesign options. Researchers and clinicians have described options for improving the delivery of care by focusing on changes to structural elements of care (eg, personnel and organization used for care provision). These changes include using nonphysicians to provide more WCC services, providing some services in non–face-to-face visits, and offering some services outside the clinical setting.11–18 A comprehensive review of these proposed tools and strategies is needed to help providers make evidence-based decisions regarding WCC clinical practice redesign. To our knowledge, this article provides the first such published systematic review.

The objective of this systematic review is to examine tools and strategies for WCC clinical practice redesign for US children aged 0 to 5, focusing on changes to the structure of care (nonphysician providers [eg, nurses, lay health educators], nonmedical locations [eg, day-care centers, home visits], and alternative formats [eg, group visits, Internet]) that may affect receipt of WCC services, child health and developmental outcomes, and overall quality of WCC.

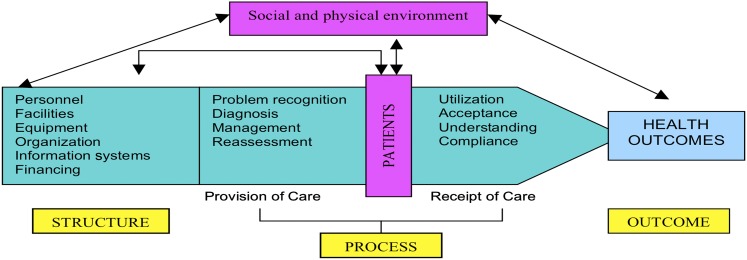

The conceptual model for this review is based on Donabedian’s model for assessing the quality of care based on structure, process, and outcome.19,20 Structures of care (eg, facilities, equipment, personnel, and organization used for the provision of care) directly influence processes of care (ie, how care is provided and received), ultimately leading to health outcomes (eg, health status),21 as detailed by Starfield (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual model: dynamics of health outcome (adapted from Starfield21).

Methods

Data Sources and Article Selection

We searched PubMed for peer-reviewed English-language articles published January 1, 1981, through February 1, 2012 using keywords for WCC (WCC, well-baby care, health supervision) and MeSH terms (primary care, preventive care). We also searched the references of accepted articles. We looked for articles that evaluated a practice-based intervention to change WCC delivery for children aged 0 to 5.

This review focused on interventions to change WCC delivery in primary care settings in the United States. To fulfill this objective, interventions had to be practice-based, applicable to WCC delivery, and based in the United States or other developed country. We did not include articles that (1) evaluated a quality improvement process without identifying a specific change to care delivery, (2) addressed only 1 topic within WCC (eg, car-seat safety) and not WCC services more generally (eg, anticipatory guidance), (3) focused on changes to WCC content or screening without addressing changes in the delivery of services, or (4) evaluated interventions designed solely to increase compliance with or use of typical WCC.

Accepted articles were systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), nonrandomized trials, or observational studies of interventions that included children aged 0 to 5 and reported findings related to receipt of WCC services, child health and developmental outcomes, and quality of care.

Three investigators independently screened the initial list of titles to exclude those that appeared irrelevant to the search. Abstracts for all potentially relevant titles were screened by 2 investigators (TC, CM) using a brief structured screening tool to determine whether the article met the inclusion criteria, including (1) study design (systematic review, RCT, non-RCT, observational study), (2) study topic (WCC clinical practice redesign), (3) target population (aged 0–5 years), and (e) country (developed nation22). The third investigator (PC) reviewed abstract screening results; disagreements were resolved by consensus. Full-text articles were obtained for accepted abstracts; 2 investigators used a structured form to extract data on design, methods, outcomes, and findings. For RCTs, overall methodologic quality was assessed using the 5-point Jadad score, which evaluates the quality of randomization, blinding, and description of withdrawals and dropouts.23 Double-blinding is part of the criteria and accounts for 2 points; however, because double-blinding is not feasible in most clinical practice redesign interventions, 3 out of 5 was our maximum score. For observational studies and nonrandomized trials, we used a modified version of the Downs and Black checklist to assess overall methodologic quality, focusing on external validity (3 items), bias (5 items), confounding (4 items), and power (1 item).24 The maximum possible total score was 13 (1 point per item).

Results

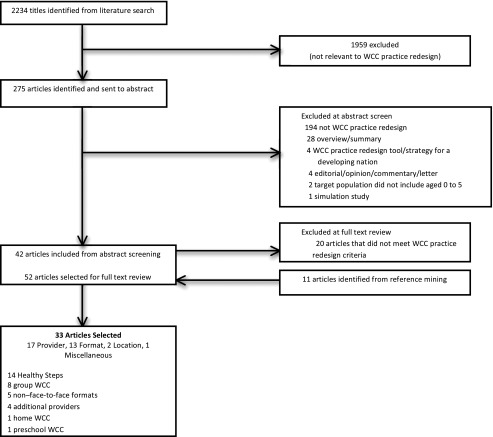

Our initial PubMed search yielded 2234 titles (Fig 2). After 1959 titles were excluded because they were not relevant to WCC clinical practice redesign, 275 titles remained for abstract screening. Of these, 233 abstracts did not meet inclusion criteria for reasons described in Fig 2; 42 abstracts went on to full-text article data extraction. Twenty articles were rejected because they did not meet criteria for WCC clinical practice redesign. Eleven articles were identified through a reference search of accepted articles. Thirty-three articles were accepted; these included 13 articles primarily on alternative formats for WCC,16,25–36 2 articles primarily on nonclinical locations for WCC,37,38 17 articles primarily on nonphysicians/non-NPs added to enhance WCC,17,39–54 and 1 miscellaneous article.55

FIGURE 2.

Article selection.

Of 13 WCC format articles, 5 were on non–face-to-face formats,25–28,36 and 8 were on group visit formats.16,29–35 Of the 17 WCC provider articles, 13 articles and 1 systematic review reported on the Healthy Steps for Young Children Program (HS, which uses a developmental specialist in WCC),17,39–51 2 articles reported on a study using a developmental specialist in another intervention,52,53 and 1 reported on use of a parent coach.54 The WCC location articles included 1 intervention of home WCC37 and 1 for preschool-based WCC.38 The miscellaneous article reported findings from an intervention that included a social worker in visits and so was placed in the provider category. The RCT quality scores (Jadad) were 2 to 3 points; the observational and non-RCT quality scores (modified Downs and Black) were 6 to 12 points (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5).

TABLE 1.

Articles on Group Well-Child Care

| First author, year | Design, measurement, outcomes | Major findings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Page, 201034 | Controlled trial | Mothers reported the following benefits from group visits: | ||||||

| Enrolled: N = 55 families (13 intervention; 42 comparison) | 1. Support from other women | |||||||

| Intervention: GWCC facilitated by physician | 2. Opportunities to make developmental comparisons with other infants | |||||||

| Child age: 0–12 mo | ||||||||

| Qualitative interviews and chart review | 3. Learning from other participants’ experiences | |||||||

| Outcomes included | 4. Enhanced parental involvement in the visit | |||||||

| • Parent perspectives on GWCC | 5. More time with the provider in the visit | |||||||

| • Health care utilization and clinic retention at 12 mo | ||||||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 8 | Healthcare utilization | GWCC (n = 11) | IWCC (n = 25) | |||||

| ED visits | 7 visits/11 patients (0.64) | 20 visits/25 patients (0.8) | ||||||

| Hospitalizations | 0 hospitalizations | 1 hospitalization | ||||||

| Acute ambulatory visits | 43 visits/11 patients (3.9) | 110 visits/25 patients (4.4) | ||||||

| No statistical testing was performed on quantitative data. | ||||||||

| Saysana, 201130 | Observational study | Results of parent survey: | ||||||

| N = 7 families | Twenty-eight surveys were collected from the 7 intervention families, nearly always answering “agree” or “strongly agree” for | |||||||

| (7 intervention; no comparison group) | ||||||||

| Intervention: 6 scheduled group well-child visits for first year of infant's life | • Satisfaction with visits, | |||||||

| Child age: 1–12 mo | • Understanding of information shared at visits, | |||||||

| Six-item parent survey after each group visit | • Usefulness of information shared, | |||||||

| Outcome: parent satisfaction | • Having their questions answered, and | |||||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 7 | • Having enough time to ask questions at visits | |||||||

| Cluster RCT | ||||||||

| Enrolled: N =27 residents (9 intervention; 18 control) | ||||||||

| Resident survey | ||||||||

| Outcome: resident learning experience (results not reported here) | ||||||||

| Downs & Black score: N/A | ||||||||

| Taylor, 1997, Taylor, 1997a, Taylor, 199831 | RCT | Outcomes (Taylor 199733) | GWCC (n = 106) | IWCC (n = 104) | P value | |||

| Enrolled: n = 220 families (111 intervention; 109 control) | Visit compliance | 47% | 54% | NS | ||||

| Provider time per patient, minute, mean (SD) | 19 (7.1) | 20 (8.6) | NS | |||||

| Intervention: GWCC visits | Immunizations up-to-date at 1 y | 67% | 73% | NS | ||||

| ED visits, mean (SD) | 1.12(1.98) | 1.18(1.62) | NS | |||||

| Child age: 4–15 mo | Child health status score, mean (SD) | 92.4 (1.4) | 92.5(1.1) | NS | ||||

| Parent questionnaires, standardized inventories, and chart review | ||||||||

| Outcomes (Taylor 1998) | GWCC | IWCC | P value | |||||

| Outcomes included the following: | Maternal competence (% with low-risk score) | 41/72 (57%) | 35/69(51%) | NS | ||||

| • Health care utilization | Maternal social isolation (% with low-risk score) | 48/71 (68%) | 61/80 (76%) | NS | ||||

| • Child health status | Maternal social support (% with low-risk score) | 56/75 (75%) | 66/83 (80%) | NS | ||||

| • Maternal competence | Child Protective Services referral | 7/80 (9%) | 7/84 (8%) | NS | ||||

| • Maternal isolation | ||||||||

| • Maternal support | Outcomes (Taylor 199732) | GWCC (n = 50) | IWCC (n = 50) | P value | ||||

| • CPS referral | Bayley motor index, mean (SD) | 103.6(11.5) | 100.0 (12.4) | NS | ||||

| • Infant development (Bayley) | Bayley mental index, mean (SD) | 99.3 (14.8) | 100.4 (14.3) | NS | ||||

| • Maternal-child interactions (NCATS) | NCATS, high risk (%) | 10% | 10% | NS | ||||

| • Home environment (HOME) | HOME assessment, high risk (%) | 4% | 16% | NS | ||||

| Jadad score: 2 | ||||||||

| Rice, 199716 | Controlled trial (sequential assignment to intervention versus control) | Outcomes | GWCC (n = 25) | IWCC (n = 25) | P value | |||

| Knowledge of child health and development, mean score (SD) | 5.08 (3.58) | 3.24 (3.39) | NS | |||||

| Enrolled: n = 50 families (25 intervention; 25 control) | Maternal social support, mean score (SD) | 0.28 (3.96) | 0.48 (5.56) | NS | ||||

| Intervention: GWCC | Maternal depression, mean score (SD) | 2.00 (6.65) | 4.38 (10.45) | NS | ||||

| Child age: 2–10 mo | ||||||||

| Parent questionnaires, standardized instruments, and chart review | Outcomes | GWCC (n = 12) | IWCC (n = 10) | P value | ||||

| Illness-related office visits up to 4 mo of age | NR | NR | NS | |||||

| Outcomes included: | Illness-related office visits from 4–6 mo of age | 5 visits in 12 patients | 27 visits in 10 patients | NR | ||||

| • Parent knowledge of child health and development | ||||||||

| • Maternal social support | ||||||||

| • Depression recovery | ||||||||

| • Illness-related visits | ||||||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 9 | ||||||||

| Dodds, 199335 | Observational study | For most AAP-recommend categories, more content was covered in GWCC versus IWCC visits | ||||||

| N = 76 health supervision visits (14 intervention; 62 comparison group) | Percent of content covered | GWCC | IWCC | P value | ||||

| Intervention: GWCC | Safety | 51% | 25% | <.01 | ||||

| Child age: 2 and 12 mo | Nutrition | 59% | 47% | <.01 | ||||

| 14 GWCC visits observed 62 IWCC visits observed | Behavior and development | 69% | 41% | <.01 | ||||

| Family and parenting issues | 56% | 15% | NS | |||||

| Coded visit content for topic categories | Sleep | 72% | 50% | <.01 | ||||

| Outcome: amount of content covered during health supervision visits | Toilet | 100% | 66% | NS | ||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 10 | ||||||||

| Osborn, 198129 | Controlled study | Outcomes | GWCC N = 42 | IWCC N = 36 | P value | |||

| Enrolled: N = 78 families (42 intervention; 36 control) | Clinician time per infant, min, mean | 15 | 16 | NS | ||||

| Visit compliance, number of visits, mean | 3.4 | 2.9 | NS | |||||

| Intervention: 3 GWCC visits within first 6 mo of life | Number of times illness not reported in infant | 97 | 55 | <.001 | ||||

| Number of times mothers sought advice between visits | 54 | 54 | NS | |||||

| Number of times mothers did not seek advice between visits | 89 | 49 | <.05 | |||||

| Child age: 2 wk–6 mo | Content analysis of visits: | |||||||

| Parent questionnaires, parent interviews, and tape recordings | Comparing GWCC to baseline, more time was spent discussing personal concerns in the infant’s daily care (28% vs 11%, P < .005), and less time was spent discussing medical aspects of care (23% vs 57%, P < .002). Similar results were found comparing GWCC to the IWCC study visits; more time spent discussing personal concerns (28% vs 22%, P < .002) and less time spent discussing medical aspects (23% vs 43%, P < .02) | |||||||

| Outcomes included the following: | Process analysis of visits: | |||||||

| • Clinician time spent per infant | Compared with baseline, providers in GWCC visits had a decrease in direct questions (10% vs 29%, P < .001) and reassurance (4% vs 10%, P < .02) but an increase in explanations (57% vs 28%, P < .001). Compared with IWCC study visits, the intervention visits had more indirect questions (11% vs 7%, P < .02), less reassurance (4% vs 9%, P < .02), and fewer direct questions (10% vs 22%, P < .001). | |||||||

| • Patient visit compliance | ||||||||

| • Health care utilization | ||||||||

| • Content and process of visits | ||||||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 9 | ||||||||

AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; HOME, Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment; NCATS, Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale; NR, not reported; NS, not significant.

TABLE 2.

Non–Face-to-Face Formats

| First author, year | Study design | Major findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paradis, 201127 | RCT | |||||

| Enrolled: N = 137 families (70 intervention; 67 control) | No differences in scores on scales for parent competence, self-efficacy, or knowledge of infant development. | |||||

| Intervention: 15-min educational DVD for anticipatory guidance at newborn visit | Parents in control group had 2.6 times greater odds of having 1 additional office visits between the newborn and 2-mo visits (adjusted odds ratio 2.6, 95% CI: 1.3–5.5) | |||||

| Child age: ≤1–2 mo | ||||||

| Parent survey and chart review | ||||||

| Outcomes included: | ||||||

| • Parent knowledge of infant development | ||||||

| • Self-efficacy with infant care skills | ||||||

| • Problem-solving competence | ||||||

| Jadad score: 3 | ||||||

| Bergman, 200925 | Observational study | Outcomes | E-visit | E-visit + in-person visit | Tailored visit | |

| Families: N = 78 | Parent satisfaction with WCC visit | 80% | 84% | 80% | ||

| • E-visit only (n = 10) | Parent perception that the model of care: | |||||

| • E-visit with brief provider visit (n = 25) | ||||||

| • Extended CSHCN visit (n = 15) | ||||||

| Tailored visit (n = 28)a | Helped them to prepare for visit | N/A | 92% | 94% | ||

| Providers: N = 7 | ||||||

| Intervention: model for WCC that includes 3 visit types | Helped to them identify important topics | 70% | 84% | 80% | ||

| Parent and provider phone surveys | Improved efficiency of WCC visit | 90% | 88% | 80% | ||

| Outcomes included | ||||||

| • Feasibility of intervention | ||||||

| • Acceptance of intervention | ||||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 6 | ||||||

| Christakis, 200628 | RCT | Discussion of prevention topics | ||||

| Enrolled: N = 887 families | • All intervention groups vs control: IRR (CI) 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | |||||

| Web content + provider notification (n = 210) | • Content + notification group vs control: IRR 1.09 (1.00–1.20) | |||||

| Web content only (n = 238) | Implementation of prevention topics | |||||

| Provider notification only (n = 211) | • All intervention groups vs control: IRR 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | |||||

| Control group (n = 228) | • Content + notification group vs control: IRR 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | |||||

| Intervention: tailored, evidence-based web site for prevention topics | ||||||

| Child age: 0–11 y | ||||||

| Parent interview and home visit validation of practices | ||||||

| Outcomes included | ||||||

| • Number of prevention topics discussed | ||||||

| • Number of prevention practices adopted | ||||||

| Jadad score: 3 | ||||||

| Sanghavi, 200526 | Controlled trial | Parent knowledge of AG topics | Intervention (N = 49) | Control (N = 52) | P value | |

| N = 101 families (49 intervention; 52 control) | Perfect score or only 1 question wrong | 35% | 2% | <.001 | ||

| Intervention: interactive, self-guided educational kiosk for anticipatory guidance | Average % of questions correct | 81% | 61% | .01 | ||

| Child age: 6 wk and 4 mo | ||||||

| Parent questionnaire | ||||||

| Outcome: parent knowledge of AG topics | ||||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 12 | ||||||

| Kempe, 199936 | Observational study | Audiotaped survey of users | ||||

| N = 561 audiotaped survey users | PAL made a call to physician unnecessary: 69% | |||||

| PAL made a visit to physician unnecessary: 70% | ||||||

| N = 137 telephone survey users/nonusers (44 users; 93 nonusers) | PAL answered their question: 87% | |||||

| Would use PAL again: 98% | ||||||

| Intervention: Parent Advice Line (PAL), collection of 278 health-related messages accessible by phone | Telephone survey of random sample of users (n = 44) | |||||

| Satisfaction with PAL: 86% | ||||||

| Child age: <12 y | ||||||

| Audiotaped survey and telephone survey | ||||||

| Outcomes included | ||||||

| • Utilization of PAL | ||||||

| • User satisfaction | ||||||

| • Effect on health-seeking behavior | ||||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 8 | ||||||

All participants completed the web-based preassessment tool; participants in the tailored visit group had a regular visit tailored to their responses. AG, anticipatory guidance.

TABLE 3.

Alternative Locations of Care

| First author, year | Study Design | Major Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gance-Cleveland, 200538 | Observational study | The 2 groups of parents were not demographically similar and no adjustments were made in the analysis. Parents without access to the PBHC were more likely to receive public assistance, have a child on the free/reduced lunch program, have a single parent household, and have lower educational goals for their child. | |||

| N = 261 families | |||||

| 130 families from preschool with PBHC | |||||

| 131 families from preschool without PBHC | |||||

| Intervention: PBHC program that included WCC, minor acute care, immunizations, mental health services, and assistance with enrolling in low-cost insurance | The study found no significant differences in parent-reported health problems between the 2 groups, but did find that the PBHC children had fewer parent-reported behavioral problems in school. | ||||

| Child age: 3–5 y | Other significant findings (PBHC vs comparison group): | ||||

| Parent survey | • Access to care (97% vs 89%, P < .001) | ||||

| Outcomes included the following: | • No problems getting care for child (64% vs 50%, P = .019) | ||||

| • Obtaining healthcare services | • No problems getting immunizations (92% vs 82%, P = .005) | ||||

| • Satisfaction with care (results not reported here) | • No problems getting physical health services (84% vs 79%, P = .045) | ||||

| • Parent-perceived child health problems | |||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 6 | |||||

| Christ, 200737 | Controlled triala | Outcomes | Intervention % | Control % | P value |

| Maternal satisfaction with | |||||

| Enrolled: N = 630 families (150 intervention; 480 control) | • Convenience of visit | 91 | 61 | <.05 | |

| • Caring attitude of provider | 93 | 75 | <.05 | ||

| Intervention: home visit for 2-wk well-baby visit | • Time spent with provider | 86 | 64 | <.05 | |

| • Skills/abilities of provider | 90 | 73 | <.05 | ||

| Child age: 2 wk; assessment at 4–6 wk | • Preventive advice given | 85 | 65 | <.05 | |

| • Overall care since birth | 86 | 73 | NS | ||

| Parent telephone questionnaire | Preference for clinic over home visit | 6 | 48 | <.05 | |

| Anticipatory guidance given on | |||||

| Outcomes included the following: | • Sleep position | 96 | 69 | <.05 | |

| • Maternal satisfaction | • Comforting baby | 85 | 55 | <.05 | |

| • Quality of anticipatory guidance | • How to get help for the baby | 97 | 72 | <.05 | |

| • Health care utilization | • Baby’s weight | 99 | 95 | NS | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 47 | 38 | NS | ||

| Utilization outcomes | Intervention no. | Control no. | P value | ||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 9 | Contacted advice lines | 0 | 0 | NS | |

| Acute care visits to ED or clinic | 1 | 1 | NS | ||

NS, not significant; PBHC, preschool-based health center.

The study was likely underpowered to detect differences between the 2 groups; the authors provided a power analysis estimation of 500 patients per study arm.

TABLE 4.

Other Providers Added to the Well-Child Visit

| First author, year | Study Design | Major Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farber, 200954 | Observational study | Parent outcomes | Intervention mean (SD) | Comparison mean (SD) | P value |

| N = 80 families | Total basic needs score (n = 65) | 52.4 (7.8) | 44.9 (9.0) | .001 | |

| (50 intervention; 30 comparison) | 28.0 (3.4) | 20.2 (7.2) | <.001 | ||

| 28.8 (5.0) | 25.5 (5.8) | .025 | |||

| Intervention: parent mentoring with a parent coach to strengthen anticipatory guidance | Total needs and resources scorea | 117.8 (15.9) | 96.1 (20.3) | <.001 | |

| Total knowledge of nurturing practices and childrearing beliefsa (n = 65) | 0.63 (0.76) | 1.50 (1.10) | .001 | ||

| Total resilience score (n = 58) | 108.5 (11.0) | 101.2 (11.2) | .026 | ||

| Child age: newborn–18 mo | |||||

| Standardized inventories and instruments, and chart review | Child Outcomes | Intervention mean (SD) | Comparison mean (SD) | P value | |

| Expressive vocabulary, mean (n = 40) | 83 (9.6) | 73 (12.2) | .01 | ||

| Receptive vocabulary, mean (n = 40) | 89 (11.6) | 79 (12.5) | .02 | ||

| Parent outcomes: | |||||

| • Adequacy of family needs and resources | |||||

| • Parent knowledge of nurturing practices and childrearing beliefs | |||||

| • Personal resilience | |||||

| Child outcomes: | |||||

| • Immunizations | |||||

| • Developmental milestones | |||||

| • Emerging language competency | |||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 6 | |||||

| Mendelsohn, 2005,52 200753 | RCT | Outcomes at 21 mo (Mendelsohn 2005) | ANOVA, F statistic | P value | |

| Enrolled: n = 150 families (77 intervention; 73 control) | Cognitive development (MDI) | F = 5.4 (n = 93) | .02 | ||

| Intervention: an approach to WCC that adds a child developmental specialist to the regular well visit from age 2 wk to 3 y | Language development (expressive) | F = 2.0 (n = 91) | .16 | ||

| Language development (receptive) | F = 1.2 (n = 91) | .27 | |||

| Child age: 2 wk–33 mo; assessments at 6, 9, 21, 33 mo | |||||

| Outcomes at 33 mo (Mendelsohn 2007) | Intervention (N = 51) | Control (N = 46) | P value | ||

| Standardized inventories and instruments, and video recording | Parenting stress (PSI), % in clinical range | 39 | 59 | .09 | |

| Parent-child dysfunction subscale, % in clinical range | 37 | 48 | .40 | ||

| Outcomes included: | Difficult child subscale, % in clinical range | 29 | 28 | 1.0 | |

| • Maternal depression (CES-D) | Maternal depression, % in clinical range | 19 | 26 | .61 | |

| • Parenting stress (PSI) and subscales | Cognitive MDI score, % normal | 64 | 44 | .048 | |

| • Child cognitive development (MDI) | Language PLS-3 score, % normal | 31 | 36 | .69 | |

| • Language development (PLS-3) | Behavior CBCL score, % in clinical range | 8 | 17 | .16 | |

| • Child behavior (CBCL) Jadad score: 2 | |||||

| O’Sullivan, 199255 | RCT | Outcomes at 18 mo | Intervention % | Control % | P value |

| N = 243 teen mothers (120 intervention; 123 control) | Visit attendance for well-baby visits | 40 | 18 | .002 | |

| Intervention: physician/nurse practitioner alternating WCC visits; social worker at 2-wk visit; waiting-room health education by NP and trained volunteers using video and slides | Repeat pregnancies | 12 | 27 | .003 | |

| Return to school | 56 | 55 | NS | ||

| Infant fully immunized | 33 | 18 | .011 | ||

| At least 1 ED visit for infant care | 76 | 85 | NS | ||

| Child age: newborn to 18 mo | |||||

| Parent interview, chart review, and school attendance | |||||

| Outcomes: | |||||

| • Repeat pregnancy rate | |||||

| • Mother returning to school | |||||

| • Immunization status | |||||

| • ED visits | |||||

| Jadad score: 2 | |||||

ANOVA, analysis of variance; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist, CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale; MDI, Bayley Scales of Infant Development, 2nd Edition, Mental Development Index; PLS-3, Preschool Language Scale -3; PSI, Parenting Stress Index.

Higher scores on this scale indicate parenting difficulties.

TABLE 5.

Healthy Steps Articles Included in Piotrowski et al Review

| First Author, Year | Design, Outcomes | Findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minkovitz, 200147; Minkovitz, 200317; Minkovitz, 200749 | Controlled trial | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Child age | Article first author, yr | ||

| 6 RCT sites (n = 1987) | ||||||

| 9 quasi-experimental sites (n = 2909) | Quality of care outcomes | |||||

| Parent questionnaire at enrollment | Patient-centeredness | |||||

| • Providers’ helpfulness | 2.09 (1.80–2.43) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| Phone interview at infant age 2–4 mo | • Dissatisfied with provider support | 0.37 (0.30–0.46) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | ||

| • Dissatisfied with provider listening | 0.67 (0.53–0.84) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| Phone interview at child age 30–33 mo | • Dissatisfied with provider respect | 0.79 (0.63–1.00) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | ||

| 6 RCT sites (n = 1593) | Up to date with immunizations at 24 mo | 1.59 (1.27–1.98) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | ||

| 9 quasi-experimental sites (n = 2144) | Had 24 mo WCV | 1.68 (1.35–2.09) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | ||

| Had developmental assessment | 8.00 (6.69–9.56) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| Phone interview at child age 5.5 y | Discussed 5 of 6 AG topics at 2 mo, >7 of 10 AG topics at 30 mo, or >4 of 6 AG topics at 5 y | 2.41 (2.10–2.75) | 2 mo | Minkovitz, 01 | ||

| 10.36 (8.5–12.6) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | ||||

| 1.33 (1.13–1.56) | 5 y | Minkovitz, 07 | ||||

| 6 RCT sites (n = 1724) | Composite measure -clinician provides support for parent | 2.33 (1.82–3.03) | 2 mo | Minkovitz, 01 | ||

| 9 quasi-experimental sites (n = 1441) | 2.70 (2.17–3.45) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| 1.25 (1.02–1.53) | 5 y | Minkovitz, 07 | ||||

| Outcomes: | • Remained at practice | 1.82 (1.57–2.12) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | ||

| • Receipt of intervention services (results not reported here) | 1.19 (1.01–1.39) | 5 y | Minkovitz, 07 | |||

| • Hospitalizations in past year | 1.14 (0.84–1.54) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| • Parenting practices | 0.90 (0.57–1.42) | 5 y | Minkovitz, 07 | |||

| • Perceptions of care | • ED use in past year | 1.03 (0.89–1.20) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | ||

| • Quality of care | • ED use in past year, injury-related | 0.77 (0.61–0.97) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | ||

| • Child behavior | 1.00 (0.83–1.20) | 5 y | Minkovitz, 07 | |||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 12 | Discipline | |||||

| • Ever slap face or spank with object | 0.73 (0.55–0.97) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| 0.68 (0.54–0.86) | 5 y | Minkovitz, 07 | ||||

| • Use harsh discipline | 0.78 (0.62–0.99) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| 0.98 (0.74–1.30) | 5 y | Minkovitz, 08 | ||||

| • Use negotiation | 1.16 (1.01–1.34) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| 1.20 (1.03–1.39) | 5 y | Minkovitz, 07 | ||||

| • Ignore misbehavior | 1.38 (1.10–1.73) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| 1.24 (0.97–1.59) | 5 y | Minkovitz. 07 | ||||

| Parent perception of child behavior and development | ||||||

| • Parent concern for behavior | 1.26 (1.01–1.57) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| 1.35 (1.10–1.64) | 5 y | Minkovitz. 07 | ||||

| Aggressive behavior | 0.40 (0.06–0.75) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| Anxious or depressed | 0.19 (–0.004–0.38) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| Problems sleeping | 0.20 (0.03–0.36) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| Parenting practices | ||||||

| • Follows routines | 1.00 (0.88–1.13 | 2 mo | Minkovitz, 01 | |||

| 1.03 (0.88–1.20) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | ||||

| 1.02 (0.82–1.26) | 5 y | Minkovitz, 07 | ||||

| • Depressed parent discussed sadness with someone in practice | 1.60 (1.09–2.36) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| • Parent and child book sharing | 1.22 (1.07–1.40) | 2 mo | Minkovitz, 01 | |||

| 0.96 (0.82–1.12) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | ||||

| 1.16 (1.00–1.35) | 5 y | Minkovitz, 07 | ||||

| • Lowered water temp on water heater | 1.03 (0.89–1.20) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| • Uses covers on outlets | 1.17 (0.92–1.48) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| • Uses safety latches on cabinets | 1.09 (0.86–1.39) | 30 mo | Minkovitz, 03 | |||

| Caughy, 2003;40 Caughy, 200439 | Observational study of 2 HS randomized sites | Caughv 2003 | ||||

| Parent discipline | ||||||

| N = 378 families at 16- to 17-mo home observation (217 intervention, 161 control) | • Intervention parents were more likely to use inductive/authoritative discipline strategies compared with control group parents at 16 mo; at 34 mo, there was no difference between the 2 groups. There was no difference between groups at either 16 or 34 mo on the use of punitive strategies. | |||||

| N = 233 families at 34- to 37-mo home observation (34 intervention, 99 control) | • Intervention vs control mean scores (SD) for inductive/authoritative: 0.10 (0.07) vs –0.12 (0.08) at 16 mo, P < .05 | |||||

| Child age: birth to 37 mo | Caughv 2004 | |||||

| Parent outcomes | ||||||

| In-home observation and parent interview | • No differences in parent outcomes between intervention and control at 16 mo. At 34 mo, intervention group parents were more likely to interact sensitively and appropriately with their child compared with control parents. | |||||

| Parenting outcomes | Child outcomes | |||||

| • Sensitive parent-child interaction- Nursing Child Assessment by Satellite Training | No differences in child outcome at 16 or 34 mo between intervention and control. | |||||

| • Appropriate Parent Interaction-Parent/Caregiver Involvement Scale (P/CIS) | ||||||

| • Optimal home environment—Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment Inventory | ||||||

| Child outcomes | ||||||

| • Child attachment—Attachment Q-Sort | ||||||

| • Problem behaviors—Child Behavior Checklist | ||||||

| • Self-regulation—Toy Clean Up Task | ||||||

| Discipline outcomes | ||||||

| • Inductive/authoritative discipline strategies (eg, timeouts) vs punitive discipline strategies (eg, spanking)—Parental Responses to Child Misbehavior | ||||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 11 | ||||||

| Huebner, 2004,41; Johnston, 200443; Johnston, 200642 | Quasi-experimental comparison | Outcome | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Enrolled: N = 439 women (301 intervention; 136 comparison) | Child Health and Development (Johnston 2006) | |||||

| Integrated delivery system | 24-mo well-visit attendance | 1.0 9 (0.97–1.22) | ||||

| Three intervention clinics | Immunization up to date at 24 mo | 1.06 (1.02–1.09) | ||||

| Two comparison clinics | Language development | |||||

| Intervention: HS + prenatal component or HS alone | • Combines 2 words at 24 mo | 1.02 (0.94–1.12) | ||||

| Child age: 0–30 mo | • Two-word endings, ≥3 vs <3 | 1.10 (0.82–1.50) | ||||

| Parent survey at 3 mo and 30 mo | Maternal Depression | |||||

| Outcomes | • Clinically significant symptoms | 1.21 (0.80–1.82) | ||||

| • At 3 mo- | • Discussed sadness with provider | 1.45 (0.95–2.21) | ||||

| • Parental knowledge of development | Breastfeeding duration >6 mo | 1.18 (1.11–1.26) | ||||

| • Parenting practices | Parenting Practices | |||||

| • Parental satisfaction with quality of provider | Reads with child | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) | ||||

| • At 30 mo- | Plays with child | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | ||||

| • Child health and development | TV viewing >1 h/d | 0.75 (0.62–0.90) | ||||

| Child behavioral problems | Follows 3 routines | 1.12 (1.03–1.22) | ||||

| • Nurturing parenting style | Injury prevention index (5 vs <5 score) | 1.19 (1.09–1.28) | ||||

| • Parenting self-efficacy | Spanking with object/slapping in face | 0.46 (0.29–0.73) | ||||

| • Health care self-efficacy | Continuous outcomes (Johnston 2006) | Adjusted linear coefficient (95% CI) | ||||

| Maternal depressive symptoms | Child behavior problems | |||||

| Parenting Practices | • Aggressive behavior score, continuous | 0.83 (0.37 to 1.30) | ||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 12 | • Sleep problems score, continuous | 0.09 (−0.29 to 0.48) | ||||

| • Anxious or depressed mood score, continuous | 0.03 (−0.44 to 0.50) | |||||

| Parenting competence score, continuous | −0.92 (−1.40 to −0.44) | |||||

| Health care self-efficacy score, continuous | 0.04 (−0.28 to 0.36) | |||||

| Parenting nurturing scale, continuous | −0.06 (−0.42 to 0.31) | |||||

| Outcome (Johnston 2004) | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) or linear regression coefficient (95% CI) when indicated | |||||

| Parental knowledge | ||||||

| • of infant development, linear regression | 0.02 (0.00– 0.03) | |||||

| • of safe sleep positions | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.04) | |||||

| • of appropriate discipline | 1.08 (1.04 – 1.11) | |||||

| Parenting practices | ||||||

| • Home safety score, linear regression | 0.10 (0.02– 0.17) | |||||

| • Breastfeeding at 3 mo | 1.14 (1.09–1.20) | |||||

| • Tobacco-free home | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | |||||

| • Safe sleep | 1.02 (0.98–1.05) | |||||

| • Reading with child | 1.12 (1.04–1.22) | |||||

| Minkovitz, 2003a | Clinician perspectives | Intervention group providers odds ratio (95% CI) 30-mo vs baseline | ||||

| Cross-sectional survey | Practice barriers | |||||

| N = 118 clinicians at baseline (80 intervention surveys, 70 control surveys) | • Limited staff to address needs of families | 0.43 (0.08–2.40) | ||||

| • Problems with reimbursement | 1.86 (0.76–4.53) | |||||

| N = 99 clinicians at 30-mo follow-up (69 intervention surveys, 70 control surveys) | • Inadequate time with families | 1.87 (0.76–4.56) | ||||

| Discussed family psychosocial risk factors | 0.64 (0.33–1.25) | |||||

| Child age: birth-3 y | Satisfied with ability of clinical staff to meet needs of families | 4.05 (1.15–14.2) | ||||

| Provider and staff surveys | Perceptions of HSS | |||||

| Outcomes included the following: | • Talks to parents about child behavior/development | 7.58 (2.08–27.67) | ||||

| • Perspectives on HSS | • Shows parents activities and gives information about what to do with their child | 5.85 (1.89–18.09) | ||||

| • Perspectives on HS program | • Provides parents with support, helps with stress, and refers for parent emotional problems | 5.84 (1.80–19.01) | ||||

| Results shown are for quasi-experimental group only; changes from baseline to 30 mo | • Discusses temperament and/or sleep problems | 5.64 (1.40–22.68) | ||||

| Downs & Black score: N/Aa | ||||||

| Kizner, 200444 | Observational study | Resident perceptions of HSS (N = 29 residents) | ||||

| N = 37 residents (37 intervention; no comparison) | • 69%: HSS assisted with resident learning of anticipatory guidance | |||||

| Child age: birth to 3 y | • 69%: HSS facilitated resident knowledge of common responses to behavioral and developmental concerns | |||||

| Survey of resident physicians involved with JS | • 69%: HSS helped patients receive information efficiently | |||||

| Outcomes included: | • 62%: HSS did not interfere with resident-parent relationship | |||||

| • Perceptions of HSS | • 66%: Enjoyed working with the HSS | |||||

| • Perception of HS program | • 76%: Would consider using HSS in their future practice | |||||

| Downs & Black score: N/Aa | • 35%: HSS improved clinic efficiency | |||||

| Resident perceptions of Healthy Steps Program (N = 29 residents) | ||||||

| • 90%: HS did not help improve resident knowledge of family violence | ||||||

| • 97%: HS did not help improve resident awareness of mental illness | ||||||

| • 69%: HS did not help the resident establish community contacts and referrals | ||||||

| Niederman, 200750 | Controlled trial | Intervention children had greater continuity of care for well-child visits compared with control children (52% vs 28% with scores indicating excellent continuity). This was measured for intervention and control group children at 1 site (n = 263) using the Continuity of Care Index of Bice and Boxerman. The score is 0 to1, with 0 indicating that all visits were made with different providers and 1 indicating that all visits were made with 1 provider. | ||||

| N = 363 children (71 intervention, 292 control) | ||||||

| Child age: birth to 3 y | ||||||

| Chart review | ||||||

| Outcomes included the following: | There were no statistically significant differences between intervention and control children for | |||||

| • Continuity of care | • longitudinality of care | |||||

| • Longitudinal care | • quality of care (immunizations, anemia and lead screening) | |||||

| • Quality of care | • behavioral, developmental, or psychosocial diagnoses | |||||

| • Rates of diagnoses | ||||||

| Downs & Black score (modified): 9 | ||||||

| McLearn, 200445 | Cross-sectional survey of clinicians (physicians and NPs) at 20 HS program sites | Does not compare intervention versus control clinicians; compares clinician perceptions by income level of patients served | ||||

| N = 104 clinicians at baseline | ||||||

| N = 120 clinicians at 30 mo | ||||||

| Outcome: perspectives on HS program | ||||||

| Downs & Black score: N/A | ||||||

| McLearn, 200446 | Observational study | Does not compare intervention versus control families; compares outcomes for intervention group families by income level | ||||

| N = 1910 families (1910 families; no comparison) | ||||||

| Child age: 1–33 mo; assessments at 2–3 and 30–33 mo | ||||||

| Parent survey | ||||||

| Outcomes: | ||||||

| • Quality of care | ||||||

| • Parent experiences and satisfaction with care | ||||||

| Downs & Black score: N/Aa | ||||||

AG, anticipatory guidance; WCV, well-child visit.

Downs and Black checklist was only used for studies that reported parent or child outcomes and included an intervention and comparison group.

Alternative Formats

Group Visits

We found 8 articles (Table 1) that evaluated group WCC (GWCC). In GWCC, families are seen for a well-child visit in a group of 4 to 6 families with similarly aged children. All but 1 study examined GWCC for children from newborn through 12 to 15 months of age; 1 study examined GWCC for children up to age 12. The group discussion section of the GWCC visit was often conducted by the physician or NP and was preceded or followed by measurement, physical examination, and immunization of each child. The group visit took 60 to 90 minutes, allowed parents to have more provider time, and maintained or increased the usual provider time per patient.

Taylor and colleagues31–33 performed an RCT of GWCC among children at high risk (eg, maternal poverty) and reported results in 3 publications. Investigators enrolled 220 mothers (111 GWCC; 109 individual WCC [IWCC]). There were few statistically significant differences between the study arms in health care utilization, visit compliance, maternal outcomes (eg, stress), and child development. The authors concluded that GWCC was at least as effective as IWCC in providing WCC to children aged 4 to 15 months. In a controlled trial of GWCC with 50 families,16 investigators found few differences in outcomes between the 2 study arms, but a chart review showed that intervention children had fewer illness visits between well-child visits than control children (27 visits/10 control patients vs 5 visits/12 GWCC patients). These studies do not report an a priori power analysis for all major outcomes and may not be sufficiently powered. In another controlled trial of GWCC (n = 78), intervention parents were less likely to seek advice concerning their child between well-child visits (did not seek advice 89 vs 49 times, P < .05).29 The reason for this decrease in utilization is unclear; parents could have been less likely to seek advice between visits for a number of reasons, ranging from more effective parent education to weaker doctor-parent relationships. Dodds et al35 conducted an observational study comparing GWCC with IWCC and found that more anticipatory guidance content was covered in GWCC compared with IWCC (eg, 69% vs 41% of behavioral/developmental content, P < .01).

Page et al34 interviewed mothers who participated in GWCC to examine perceptions of the visit format. Participating mothers highlighted several benefits of GWCC, including (1) support from other women, (2) opportunities to make developmental comparisons with other infants, (3) the chance to learn from other participants’ experiences, (4) enhanced parental involvement in the visit, and (5) more time with the provider. Saysana et al30 conducted a study of GWCC in a pediatric residency continuity clinic, with a primary objective of comparing learning experiences for pediatric residents participating in GWCC versus IWCC; the investigators also assessed visit satisfaction for the 7 families who participated in GWCC. Parents were generally satisfied with the visits, but no comparison group was included for parents.

Non–Face-to-Face Formats

Two studies incorporated an Internet-based tool into WCC to deliver anticipatory guidance (Table 2). In Christakis et al,28 parents received a link to a web-based system, MyHealthyChild, before their well-child visit. On the web site, parents could select age-appropriate and personally relevant topics to receive more information on and to discuss with their provider at the next visit. Providers could access parents’ responses and scores on the previsit assessment to tailor the visit. An RCT with 887 parents was conducted, demonstrating a modest increase in the number of topics discussed (8%–9% more topics discussed in intervention visits; incidence rate ratio [IRR] 1.07, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.01–1.14) and in the number of prevention-related changes parents made in response (implemented 5%–7% more topic suggestions; IRR 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.06). A similar tool was studied in Sanghavi et al.26 An educational kiosk provided anticipatory guidance to parents in the waiting room before a 6-week and 4-month well-child visit. The controlled trial showed greater knowledge among intervention versus control parents on prevention-related topics (81% vs 61% of questions answered correctly, P = .01).

Bergman et al25 recognized that one format may not work for all families. This study examined a tailored WCC model in which the provider chose visit type on the basis of the family’s needs. Parents completed web-based developmental and behavioral screening before their visit. Sixty-three families received WCC in 1 of 3 ways: (1) electronically (e-visit) with no in-person contact with the provider, (2) as an e-visit paired with a brief in-office encounter, or (3) as an expanded well-child visit for children with special health care needs. Parents with each visit type were satisfied with their visit and reported that it was more efficient than a usual visit. Parents with an e-visit only did not think that it should be used for all visits.

Two studies examined more “low-tech” formats to enhance anticipatory guidance in WCC. Kemp et al36 examined a parent phone advice line that provided pre-recorded messages on 278 topics related to preventive care, health promotion, behavior and development, and mild acute illness management. Of 561 phone-system users, most reported that their use of the phone system had made a subsequent call (69%) or related visit (70%) to their doctor unnecessary. Paradis et al27 conducted an RCT of an anticipatory guidance DVD shown to 70 parents at the newborn visit. Scores on parent knowledge, self-efficacy, and competency measured after 2 weeks were similar between the 2 groups; however, intervention parents were less likely to have a sick visit or other problem-related visit outside of scheduled WCC visits (39% vs 63%, P = .01). It is not clear whether this decreased utilization was related to a reduced need (eg, improved parent knowledge) or unmet need.

Nonclinical Locations

Two studies examined WCC redesign in terms of location of care (Table 3). Other studies that we reviewed incorporated home visits into their WCC model (ie, HS); however, only 1 study used home visits as its primary location for WCC. There is a large literature on home visitation to improve health and well-being for families with young children; this literature is reviewed elsewhere.56–60 We focus on studies that examined home visits explicitly to deliver WCC.

Christ et al37 conducted a controlled trial of home WCC among military families for the 2-week well-child visit. Home visits lasted 60 to 90 minutes, were provided by an NP, and included all typical WCC services. The investigators compared 480 usual care clinic visits to 150 home visits and found that maternal perceptions of visit quality was higher for home visits (satisfaction with preventive advice given was 85% vs 65%, P < .05), but they found no differences in acute care utilization.

Gance-Cleveland et al38 compared parent-reported child health status, access to care, perceptions of care, and health care utilization for 261 children aged 3 to 5 years at 2 preschools, 1 with and 1 without access to a preschool-based health center that provided WCC. The preschoolers with health center access were less likely to have behavioral problems in school (P = .01, estimates not reported), problems getting care (64% vs 50%, P = .02), and unnecessary emergency department (ED) visits (12% vs 22%, P < .001) reported by parents. However, there were significant differences in respondents’ demographics, suggesting that the 2 schools were not adequately matched on socioeconomics. Parents of children from the preschool without health center access were more likely to receive public assistance (P = .003, point estimates not reported), to use the free or reduced lunch program (P < .001), to have a single-parent household (P value not reported), and to report lower educational goals for their children (P value not reported).

Nonphysician Providers

Studies of 3 interventions examined the use of additional providers to enhance WCC. The first of these interventions, HS, is a program in which a physician and child developmental specialist (typically a nurse, social worker, or early childhood educator61) provide WCC in partnership. The program includes well-child visits conducted jointly or consecutively by the physician and HS specialist (HSS), as well as other services offered by the HSS, including 6 home visits during the first 3 years of life, a child development telephone information line, written information on prevention, and monthly parent group sessions. In 2009, Piotrowski et al published a systematic review of the literature evaluating HS.51 There were 13 articles included in this review, from 1999 to 2007; we have summarized them in Table 5. Among the 13 articles, 8 analyzed data from a large, national 3-year prospective, randomized controlled and quasi-experimental trial at 15 US sites that evaluated the program with 5565 newborns.17,39,40,45–49 Three articles report data from an extension study at a large integrated health maintenance organization,41–43 and 2 report findings from residency continuity clinics that implemented HS as part of the national program.44,50

Chart review and parent interview at child age 30 to 33 months revealed that intervention children were more likely to have timely well-child visits (eg, 12-month visit 90% vs 81%, P < .001), be up-to-date on vaccinations at 24 months (83% vs 75%, P < .001), remain at the practice for ≥20 months (70% vs 57% P < .001), have better parent report of 4 family-centeredness of care measures (eg, disagreed that clinician listened to parent; 10% vs 14%, P < .001), and have discussed more than 6 anticipatory topics during their visits (87% vs 43%, P < .001). There were no statistically significant differences in hospitalizations or ED use in general, but intervention children did have a slightly decreased odds of an ED visit for an injury-related cause (9% vs 11%, adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.77, 95% CI: 0.61–0.97).17

Intervention parents were less likely to report using harsh discipline (9% vs 12%, P = .006) and slapping their child in the face or spanking them with an object (6% vs 8%, P = .01), and were more likely to report ignoring misbehavior (13% vs 9%, P = .003). Intervention parents scored slightly higher than control parents on a scale for child aggressive behavior and sleeping problems (difference of mean scores, AOR 0.40, 95% CI: 0.06–0.75; AOR 0.20, 95% CI: 0.03–0.36). There were no statistically significant differences in parental practices of reading or playing with the child, following daily routines, or child safety practices. Of those parents at risk for depression, intervention parents were more likely to report discussing sadness with their provider (24% vs 14% P < .001).3

At child age 5.5 years, 2 years after study completion, 57% of parents completed another interview, and some of these positive findings were modestly sustained. Intervention families were less likely to slap or spank their child with an object (10% vs 14%, P < .001) and more likely to use negotiation as a discipline strategy (60% vs 56%, P < .05), book sharing with their child (59% vs 54%, P < .001), and recommended car restraints (43% vs 47% did not use a booster seat, P = .01). There were no differences between the 2 groups in child health status, developmental concerns, perceived social skills, following daily routines, hospitalizations, or ED use.49

Studies also reported clinician perceptions of HS. Overall, clinicians were satisfied with the program and with the role of the HSS with parents.48

Mendelsohn et al52,53 conducted a 3-year RCT of another intervention that added a developmental specialist encounter to each visit. The level of training for the specialists is not delineated in the article, but the study does reference HSS. Children in the intervention group had twelve 30- to 45-minute developmental specialist sessions from 2 weeks to 3 years of age. Visits focused on child development and included discussion of a video recording of the parent and child engaging in an activity. Investigators enrolled 150 Latina mothers without a high school degree and found that at 33 months, intervention children were more likely to have normal cognitive development scores (64% vs 44%, P < .05), but there were no differences at 33 months for language development, behavioral problems, or eligibility for early intervention.

The third study, by Farber et al,54 examined an intervention of parent coaches to strengthen anticipatory guidance for 50 Latino and African American families in Washington, DC. Parent coaches were not medical professionals but had a college degree in early child development. Parent coaches met with families at clinic visits from the newborn through 18-month visit. Compared with the 30 comparison parents, 35 intervention parents had better scores on scales for parenting practices and adequacy of family resources, but no differences were detected in child immunization or developmental status. Intervention children performed better than the comparison group on vocabulary achievement scores for receptive (mean score 89 [SD 11.6] vs 79 [12.5], P = .02) and expressive language (83 [9.6] vs 73[12.2]).

O’Sullivan et al55 reported findings from an RCT of an intervention of enhanced WCC for adolescent mothers. Although the study did not fit well into our 3 WCC clinical practice redesign categories, it used social workers as an additional provider for WCC (Table 4). A social worker was included at the 2-week visit to discuss baby care and family planning; at each well-child visit through 18 months, mothers received teaching on infant care and mild acute illness management in the waiting room. At the end of the study, intervention mothers (n = 120) were more likely to still be attending well-child visits compared with control mothers (n = 123; 40% vs 18%, P < .05), but the dropout rate in both groups was high. Using an intention-to-treat analysis, intervention group children were more likely to be fully immunized at 18 months (33% vs 18%, P = .01); there was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of children in each group with ≥1 ED visit.

Discussion

This is the first published, peer-reviewed systematic review of WCC clinical practice redesign. We found evidence suggesting improved effectiveness and efficiency for WCC delivery using group formats for visits, non–face-to-face formats for anticipatory guidance, and non–medical professional providers for anticipatory guidance and developmental and behavioral services. Studies suggest that these strategies may potentially have an impact on parents’ experiences with care, parenting skills and knowledge, and health care utilization.

Evidence for GWCC suggests that it may be at least as effective in providing care as IWCC. Studies demonstrated efficiency for GWCC; parents had longer visits with more content, but provider time per patient was not increased. Longer WCC visits have been associated with more anticipatory guidance, family-centered care, and parent satisfaction.62 Group visits may be led by non–medical professionals, allowing for even more efficient use of physician time.63 In the GWCC studies, a physician or NP moderated the group discussion. More studies may be necessary to determine whether these findings are replicated in GWCC when the facilitator is not a medical professional.

Evidence for web-based tools for anticipatory guidance was limited; 2 trials demonstrated improvements in parent knowledge, discussion, and action on anticipatory guidance topics. Lack of Internet access may be a barrier in some populations; however, the digital divide may be narrowing as more low-income families are gaining access to the Internet.64

The large HS trial demonstrated important, although somewhat modest, improvements in receipt of WCC services, positive parenting practices, and parent experiences with care. Despite this, its adoption has been limited. In 2010, only 50 sites nationwide were using HS. The median annual program cost of $65 500 has proved to be the greatest barrier to adopting and sustaining the program in community practices.65

Another consideration is whether the studies’ findings justify the costs of implementing these clinical practice redesign tools and strategies. These include financial costs as well the opportunity costs of time, personnel, and effort in implementing these changes compared with other practice improvements that do not alter the structure of care. Break-even analyses and cost-effectiveness analyses may help practices with these decisions.

Most interventions, except for GWCC, were designed as an enhancement, rather than a replacement, for what takes place in usual care. Web-based tools provided additional anticipatory guidance and a way to tailor anticipatory guidance during the visit but did not replace anticipatory guidance in the visit. In HS, parents spend between 15 and 30 minutes with an HSS at each visit,61 with physician time being reduced from 18 to 12 minutes.65 For WCC clinical practice redesign to be sustainable, interventions may need to demonstrate greater efficiencies in physician/NP time per patient.

Parent knowledge of mild acute illness management is a desirable outcome of anticipatory guidance and can reduce unnecessary clinical contacts between scheduled well-child visits. Reduced utilization for acute care was noted in several studies; however, other reasons for decreased utilization (eg, poor patient-doctor relationship; perceived poor access) cannot be excluded in some of these studies.

There are several limitations to consider. We limited our review to peer-reviewed publications on WCC clinical practice redesign for children aged 0 to 5; however, there are redesign tools that are not in the peer-reviewed literature or that have been described but not implemented or evaluated.14,18 Some have been used outside of WCC that might be applicable to child preventive care,66–74 and some that are not practice-based could be adapted for use in a practice setting.75,76 We omitted tools that did not alter the delivery of WCC services (eg, handheld patient records)77,78 and tools that focused on clinical practice redesign for only 1 WCC topic; these tools should be considered in other reviews. Criteria for defining clinical practice redesign were somewhat stringent and limited the number of articles included. A review with a different set of criteria or fewer criteria for article inclusion could be helpful in giving pediatric practices a broader range of options for clinical practice improvements.

Because of the heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes measured, a meta-analysis was not possible. Study design heterogeneity precluded use of a single quality assessment tool for all studies; however, we used the Jadad scale for RCTs and a modified Downs and Black checklist for non-RCTs and observational studies. There is the possibility of publication bias in which studies of interventions with negative results never make it to the peer-reviewed literature.

Despite these limitations, this review has important implications for child preventive care. First, many WCC clinical practice redesign tools examined in this review are also more broadly part of efforts to transform practices into patient-centered medical homes.79–81 Group visits, non–face-to-face formats, and additional providers for WCC can increase accessibility, comprehensiveness, and family-centeredness of care (key elements of the medical home). Practices working toward a transformation into patient-centered medical homes can consider implementing WCC redesign strategies that have demonstrated some promising, albeit preliminary, results for WCC delivery.

Next, there are several provisions of the health care reform law that make WCC clinical practice redesign a timely proposition for primary care practices.82 The Affordable Care Act includes the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Innovation Center, which will investigate new service delivery and payment models, and the Prevention and Public Health Fund, which provides mandatory funding for prevention and wellness programs.

Finally, despite promising evidence for these interventions, they have not been widely adopted. In a recent study examining health plan leaders’ views on WCC clinical practice redesign, participants reported a lack of incentives for practices and health plans to invest in WCC clinical practice redesign. Furthermore, some states require Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program–contracted plans to report on a set of quality measures that reward the number of face-to-face well-child visits and inadvertently discourage the use of non–face-to-face strategies.83

There are promising tools and strategies for WCC clinical practice redesign that may be ready for larger-scale trials. Future directions for research include reporting intervention costs and potential cost savings and a commonly defined set of child and parent outcomes to help researchers build capacity for comparative studies across interventions.

Glossary

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- ED

emergency department

- GWCC

group well-child care

- HS

Healthy Steps for Young Children Program

- HSS

Healthy Steps specialist

- IRR

incidence rate ratio

- IWCC

individual well-child care

- NP

nurse practitioner

- RCT

randomized controlled trials

- WCC

well-child care

Footnotes

Drs Coker, Schuster, and Chung are former Robert Woods Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars.

Dr Moreno is currently affiliated with University of Illinois College of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Chung PJ, Lee TC, Morrison JL, Schuster MA. Preventive care for children in the United States: quality and barriers. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:491–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norlin C, Crawford MA, Bell CT, Sheng X, Stein MT. Delivery of well-child care: a look inside the door. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(1):18–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuster MA, Duan N, Regalado M, Klein DJ. Anticipatory guidance: what information do parents receive? What information do they want? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(12):1191–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Triggs EG, Perrin EC. Listening carefully. Improving communication about behavior and development. Recognizing parental concerns. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1989;28(4):185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bethell C, Reuland CH, Halfon N, Schor EL. Measuring the quality of preventive and developmental services for young children: national estimates and patterns of clinicians’ performance. Pediatrics. 2004;113(suppl 6):1973–1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halfon N, Regalado M, Sareen H, et al. Assessing development in the pediatric office. Pediatrics. 2004;113(suppl 6):1926–1933 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bethell C, Reuland C, Schor E, Abrahms M, Halfon N. Rates of parent-centered developmental screening: disparities and links to services access. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):146–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belamarich PF, Gandica R, Stein REK, Racine AD. Drowning in a sea of advice: pediatricians and American Academy of Pediatrics policy statements. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/4/e964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Council on Pediatric Practice Standards of Child Health Care. Evanston, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care. Elk Grove, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo AA, Inkelas M, Lotstein DS, Samson KM, Schor EL, Halfon N. Rethinking well-child care in the United States: an international comparison. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1692–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coker T, Casalino LP, Alexander GC, Lantos J. Should our well-child care system be redesigned? A national survey of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):1852–1857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergman D, Pisek P, Saunders M. A high-performing system for well-child care: a vision for the future. The Commonwealth Fund. 2006;40:1–59 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schor EL. Rethinking well-child care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):210–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams BC, Miller CA. American Academy of Pediatrics. Preventive health care for young children: Findings from a 10-country study and directions for United States policy. Pediatrics. 1992;89(5 pt 2):981–998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rice RL, Slater CJ. An analysis of group versus individual child health supervision. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1997;36(12):685–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minkovitz CS, Hughart N, Strobino D, et al. A practice-based intervention to enhance quality of care in the first 3 years of life: the Healthy Steps for Young Children Program. JAMA. 2003;290(23):3081–3091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuckerman B, Parker S. Preventive pediatrics—new models of providing needed health services. Pediatrics. 1995;95(5):758–762 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(suppl 3):166–206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starfield B. Health services research: a working model. N Engl J Med. 1973;289(3):132–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations Development Programme Human Development Index. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergman DA, Beck A, Rahm AK. The use of internet-based technology to tailor well-child care encounters. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/124/1/e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanghavi DM. Taking well-child care into the 21st century: a novel, effective method for improving parent knowledge using computerized tutorials. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(5):482–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paradis HA, Conn KM, Gewirtz JR, Halterman JS. Innovative delivery of newborn anticipatory guidance: a randomized, controlled trial incorporating media-based learning into primary care. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(1):27–33 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ, Rivara FP, Ebel B. Improving pediatric prevention via the Internet: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):1157–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osborn LM, Woolley FR. Use of groups in well child care. Pediatrics. 1981;67(5):701–706 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saysana M, Downs SM. Piloting group well child visits in pediatric resident continuity clinic. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(2):134–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor JA, Kemper KJ. Group well-child care for high-risk families: maternal outcomes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(6):579–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor JA, Davis RL, Kemper KJ. A randomized controlled trial of group versus individual well child care for high-risk children: maternal-child interaction and developmental outcomes. Pediatrics. 1997;99(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/99/6/E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor JA, Davis RL, Kemper KJ. Health care utilization and health status in high-risk children randomized to receive group or individual well child care. Pediatrics. 1997;100(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/100/3/E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page C, Reid A, Hoagland E, Leonard SB. WellBabies: mothers’ perspectives on an innovative model of group well-child care. Fam Med. 2010;42(3):202–207 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dodds M, Nicholson L, Muse B, III, Osborn LM. Group health supervision visits more effective than individual visits in delivering health care information. Pediatrics. 1993;91(3):668–670 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kempe A, Dempsey C, Poole SR. Introduction of a recorded health information line into a pediatric practice. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(6):604–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christ M, Sawyer T, Muench D, Huillet A, Batts S, Thompson M. Comparison of home and clinic well-baby visits in a military population. Mil Med. 2007;172(5):515–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gance-Cleveland B, Yousey Y. Benefits of a school-based health center in a preschool. Clin Nurs Res. 2005;14(4):327–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caughy MO, Huang K-Y, Miller T, Genevro JL. The effects of the Healthy Steps for Young Children Program: results from observations of parenting and child development. Early Child Res Q. 2004;19(4):611–630 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caughy MO, Miller TL, Genevro JL, Huang K-Y, Nautiyal C. The effects of Healthy Steps on discipline strategies of parents of young children. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2003;24(5):517–534 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huebner CE, Barlow WE, Tyll LT, Johnston BD, Thompson RS. Expanding developmental and behavioral services for newborns in primary care: program design, delivery, and evaluation framework. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(4):344–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnston BD, Huebner CE, Anderson ML, Tyll LT, Thompson RS. Healthy steps in an integrated delivery system: child and parent outcomes at 30 months. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(8):793–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnston BD, Huebner CE, Tyll LT, Barlow WE, Thompson RS. Expanding developmental and behavioral services for newborns in primary care; Effects on parental well-being, practice, and satisfaction. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(4):356–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kinzer SL, Dungy CI, Link EA. Healthy Steps: resident’s perceptions. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2004;43(8):743–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McLearn KT, Strobino DM, Hughart N, et al. Developmental services in primary care for low-income children: clinicians’ perceptions of the Healthy Steps for Young Children program. J Urban Health. 2004;81(2):206–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLearn KT, Strobino DM, Minkovitz CS, Marks E, Bishai D, Hou W. Narrowing the income gaps in preventive care for young children: families in healthy steps. J Urban Health. 2004;81(4):556–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minkovitz C, Strobino D, Hughart N, Scharfstein D, Guyer B, Healthy Steps Evaluation Team . Early effects of the healthy steps for young children program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(4):470–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Hughart N, et al. Developmental specialists in pediatric practices: perspectives of clinicians and staff. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(6):295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Mistry KB, et al. Healthy Steps for Young Children: sustained results at 5.5 years. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/120/3/e658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Niederman LG, Schwartz A, Connell KJ, Silverman K. Healthy Steps for Young Children program in pediatric residency training: impact on primary care outcomes. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/120/3/e596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Piotrowski CC, Talavera GA, Mayer JA. Healthy Steps: a systematic review of a preventive practice-based model of pediatric care. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(1):91–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mendelsohn AL, Dreyer BP, Flynn V, et al. Use of videotaped interactions during pediatric well-child care to promote child development: a randomized, controlled trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(1):34–41 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mendelsohn AL, Valdez PT, Flynn V, et al. Use of videotaped interactions during pediatric well-child care: impact at 33 months on parenting and on child development. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(3):206–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farber MLZ. Parent mentoring and child anticipatory guidance with Latino and African American families. Health Soc Work. 2009;34(3):179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Sullivan AL, Jacobsen BS. A randomized trial of a health care program for first-time adolescent mothers and their infants. Nurs Res. 1992;41(4):210–215 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sweet MA, Appelbaum MI. Is home visiting an effective strategy? A meta-analytic review of home visiting programs for families with young children. Child Dev. 2004;75(5):1435–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olds DL, Kitzman HJ. Review of research on home visiting for pregnant women and parents of young children. Future Child. 1993;3(3):53–92 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kendrick D, Elkan R, Hewitt M, et al. Does home visiting improve parenting and the quality of the home environment? A systematic review and meta analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2000;82(6):443–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gomby DS, Culross PL, Behrman RE. Home visiting: recent program evaluations—analysis and recommendations. Future Child. 1999;9(1):4–26, 195–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Howard KS, Brooks-Gunn J. The role of home-visiting programs in preventing child abuse and neglect. Future Child. 2009;19(2):119–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zuckerman B, Parker S, Kaplan-Sanoff M, Augustyn M, Barth MC. Healthy Steps: a case study of innovation in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):820–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Halfon N, Stevens GD, Larson K, Olson LM. Duration of a well-child visit: association with content, family-centeredness, and satisfaction. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):657–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]