Abstract

There is an implicit assumption of homogeneity across violent behaviors and offenders in the criminology literature. Arguing against this assumption, I draw on three distinct literatures [child abuse and neglect (CAN) and violence, violence and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and CAN and PTSD] to provide a rationale for an examination of varieties of violent behaviors. I use data from my prospective cohort design study of the long-term consequences of CAN to define three varieties of violent offenders using age of documented cases of CAN, onset of PTSD, and first violent arrest in a temporally correct manner [CAN → to violence, CAN → PTSD → violence (PTSD first), and CAN → violence → PTSD (violence first)], and a fourth variety, violence only. The results illustrate meaningful heterogeneity in violent behavior and different developmental patterns and characteristics. There are three major implications: First, programs and policies that target violence need to recognize the heterogeneity and move away from a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Second, violence prevention policies and programs that target abused and neglected children are warranted, given the prominent role of CAN in the backgrounds of these violent offenders. Third, criminologists and others interested in violence need to attend to the role of PTSD, which is present in about one fifth (21 percent) of these violent offenders, and not relegate the study of these offenders to the psychiatric and psychological literatures.

Keywords: violent behavior, child abuse and neglect, post-traumatic stress disorder, violent offending, longitudinal

“Instead of attempting to predict ‘violence’ as if it was a unitary, homogeneous mode of behavior, efforts should be directed at differentiating meaningful subtypes or syndromes of violent individuals and then determining the diagnostic signs in the clinical data that will enable us to identify individuals of each type.”

“The primary issue we examine concerns the extent to which there are universal patterns of violent behavior over the life course. Based on the available evidence, our best guess is that universal patterns do not exist”.

WITH GREAT APPRECIATION

It is a great honor to have been selected to receive the 2013 Edwin H. Sutherland Award. I want to thank the American Society of Criminology (ASC), the Sutherland Award Committee, and Robert Agnew, President of the ASC. I also want to express my appreciation to Joanne Belknap, 2014 President of the ASC; Preeti Chauhan; and my colleagues and former students around the country for nominating me for this award. It is extremely gratifying to have this support.

Furthermore, I want to express appreciation to the program officers at the National Institute of Justice who provided me with the initial grant support to begin this project. I also want to acknowledge the people that I have been collaborating with all these years. Sally Czaja, Kimberly DuMont, Mary Ann Dutton, Helene Raskin White, Linda Brzustowicz, Carol Worthman, and Helen Wadsworth Wilson have all helped in the design and data collection efforts for various waves of the project. In particular, I want to thank Czaja for more than ten years of managing these complex data sets from the multiple phases of the study and serving as chief data analyst. I want to express a special note of appreciation to Preeti Chauhan, Maureen Allwood, my current doctoral students, and postdoctoral fellows at John Jay who provided critical feedback on earlier drafts of this award address. No acknowledgment would be complete without a word about the administrative support that Ms. Annabella Bernard has provided to the project.

Finally, I would like to thank my husband, Michael G. Maxfield, from whom I have learned so much, who has supported me through the ups and downs of this research project over the 28 years of its existence.

VARIETIES OF VIOLENT BEHAVIOR

When I began to think about what to focus on in this award address, I thought about the work that I have been engaged in for the past years studying the long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect (CAN) and, in particular, the focus on the “cycle of violence” (Maxfield and Widom, 1996; Widom, 1989b). However, I realized that I have given many talks on the cycle of violence and two videos are available through the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (Widom, 1996, 1997). Thus, another talk on the “cycle of violence” did not seem appropriate without the addition of new findings or a new perspective. I also considered talking about the broader consequences of CAN that extend beyond delinquency, crime, and violence and that affect the multiple domains of functioning that my colleagues, students, and I have been documenting over the years (Chauhan and Widom, 2012; Currie and Widom, 2010; Kaufman and Widom, 1999; Perez and Widom, 1994; Schuck and Widom, 2005; Widom, 1999; Widom, DuMont, and Czaja, 2007; Widom and Kuhns, 1996; Widom, Weiler, and Cottler, 1999; Wilson and Widom, 2006). However, for the America Society of Criminology and the Sutherland Award Address, I thought a topic of more direct relevance might be a better choice.

In recent work (Widom and Czaja, 2012), I examined the interrelationships among childhood abuse and neglect, psychopathology, and violence and whether the empirical evidence indicated causal or simply correlational relationships. As I examined our data, I found that there was tremendous heterogeneity in the temporal sequences of these relationships and began to wonder whether this heterogeneity might have relevance for understanding violence.

In this award address, I am suggesting that we may be missing important information about violent offending by assuming homogeneity among violent offenders rather than considering the heterogeneity. I am proposing that there is meaningful heterogeneity in violent behaviors and offenders and that these varieties may have implications for understanding causality and, ultimately, for the design of prevention programs and interventions. Thus, the title of my talk is “varieties of violent behavior.”

At least two examples of earlier work that focused on heterogeneity had an important impact on the field. Each included “varieties” in its title. In Varieties of Police Behavior (1978), James Q. Wilson identified three ways or “styles” of policing—the watchman, the legalistic, and the service styles—that he then analyzed and related to local politics. In Varieties of Criminal Behavior (1982), Jan Chaiken and Marcia Chaiken analyzed self-report data from prison and jail inmates in three states and found that these offenders can be classified into varieties of criminal behavior according to the combinations of crimes they committed concurrently. The Chaikens used the phrase “violent predators” to describe the most serious category of offender, referring to those inmates who usually committed three defining crimes at high rates, and the notion of violent predators captured front page news for several years. Both Wilson’s (1978) and the Chaikens’ (1982) work stimulated considerable research in the field.

I begin with a brief mention of some of the major theories of violence to illustrate my claim that there is an explicit (or implicit) assumption of homogeneity among violent offenders. I then draw on three distinct literatures [child abuse and neglect (CAN) and violence, violence and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and CAN and PTSD] that are not typically considered together to provide a rationale for this examination of varieties of violent offenders. I use data from my prospective cohort study of the long-term consequences of CAN to determine whether varieties of violent behaviors exist and whether individuals who represent these varieties differ in meaningful ways. Advantages of using these data are that 1) the participants in this study have engaged in substantial amounts of violent behavior, 2) information is available from official arrest records and self-reports because each source of information has strengths and weaknesses (Geerken, 1994; Maxfield and Babbie, 2005), and 3) the sample includes women as well as men and Blacks and Whites. The final part of this address summarizes what I have learned from this examination and suggests questions for future research and implications for interventions and prevention efforts.

THEORIES OF VIOLENCE

General theories of violence have existed for years and have ranged from subcultural to biological and genetic and, more recently, environmental. Early on, Wolfgang (1958) and later Wolfgang and Ferracuti (1967) proposed the subculture of violence theory to explain the high levels of violence committed by young men in poor urban neighborhoods who they believed were growing up in subcultures that did not define assaults or violence as wrong or antisocial. A short time later, drawing on psychological research on classic and operant conditioning, Bandura (1973) proposed a social learning theory of aggression, arguing that children learn that aggression is acceptable behavior through modeling, or imitating behaviors, or through the rewards associated with certain behaviors. More recently, in his general strain theory, Agnew (1992, 2012) argued that, in addition to failure to achieve economic or other goals, delinquency is caused by the inability to escape painful or aversive situations. Agnew also explicitly called attention to the role of CAN, pointing to the strain associated with the impact of verbal and physical abuse. Adopting a quite different approach, Felson (2009) argued that aggression and rule breaking or deviance are both instrumental behaviors and that a bounded rational choice approach can account for both behaviors.

Biological theories of crime and violence date back to the time of Lombroso (Lombroso and Ferrero, 1895). Modern versions of biological and genetic theories of violence (Raine, 2002) have focused on the role of biological and psychosocial factors in the etiology of violence and typically have examined interactions between genes and environmental factors, where the risk of violence is highest when biological risks are combined with childhood adversities and psychosocial risks. An important example is the work of Moffitt (2005) and Caspi et al. (2002) who have been applying behavior genetic methods to examine the role of variants in particular genes in conjunction with childhood adversities to predict antisocial and violent behavior. Viding and Frith (2006) also have argued that biological causes, which may explain individual differences in predispositions to violence, need to be investigated.

Other scholars have argued that exposure to environmental contaminants (e.g., lead early in life, polychlorinated biphenyls, methyl mercury, arsenic, and secondhand smoke) is associated with neurobehavioral effects, including lowered IQ, shortened attention span, and increased risk for antisocial behavior. For example, Carpenter and Nevin (2010) have pointed to research suggesting that lead-exposed children suffer irreversible brain alterations that make them more likely to commit violent crimes as young adults.

These general approaches to understanding violence share a common perspective that attempts to explain violence or aggression compared with socialized behaviors and no violence. Not all theorists have assumed homogeneity among violent offenders (Cornell et al., 1996; Jackman, 2002; Megargee, 1970; Yarvis, 1995). Others have suggested that universal patterns of violent behavior may not exist (Laub and Lauritsen, 1993).

Some literature has distinguished among types of aggression, typically separating it into categories. For example, an extensive body of work has focused on reactive (hostile) and proactive (instrumental) aggression (Crick and Dodge, 1996; Dodge, 1991). In children, reactive aggression is displayed as anger or temper tantrums, and it appears to others as behavior that is out of control. Proactive aggression occurs in the form of bullying or attempts to obtain objects. Early traumas, such as physical abuse, are thought to lead to hypervigilance and rage reactions. In Dodge’s social information processing theory, early problems lead to overreactive defensive aggressive responses. Viding and Frith (2006) also have called attention to the distinction between impulsive reactive violence and predatory violence, and they suggested that the biological bases of these two types of aggression are likely to be different.

Moffitt’s (1993) dual taxonomy of offending behavior identified two distinct patterns—life-course persistent and adolescent limited—that have been associated with different causes, sequelae, and long-term consequences. Interestingly, the life-course-persistent offender typically begins offending in childhood and engages in more severe and chronic antisocial behavior and violence than adolescent-limited offenders (Moffitt et al., 1996, 2002). Both biological (e.g., temperament and heritability) and environmental factors (e.g., ineffective parenting and peer involvement) are thought to increase a person’s risk for life-course-persistent offending (Holmes, Slaughter, and Kashani, 2001).

Another approach taken by scholars has been to examine whether it is possible to predict who becomes violent and whether there is specialization (vs. generality) in offending (Osgood and Schreck, 2007). Stalans et al. (2004) divided violent offenders into three groups (generalized, family only, and nonfamily only) and found that the strongest predictor of violent recidivism while on probation was whether the offender was a generalized aggressor. Others have argued against specialization (Simon, 1998), believing that most criminal offenders are generalists who exhibit wide versatility in offending.

In sum, there has been considerable theorizing and empirical research on violence in general and considerably less attention to varieties of violent offending and offenders. I argue that the implicit (if not explicit) assumption of homogeneity may hinder the field in understanding violence and that it is worthwhile to focus on potential heterogeneity among violent offenders and on varieties of violent behaviors. I draw on three distinct literatures to provide a framework for an examination of varieties of violent behaviors.

CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT AND VIOLENCE

In a medical note titled, “Violence Breeds Violence—Perhaps?” Curtis (1963) expressed concern that abused children would “become tomorrow’s murderers and perpetrators of other crimes of violence, if they survive” (p. 386). Numerous theories have been put forth to explain this “cycle of violence” or “intergenerational transmission of violence,” with perhaps the most common explanation based on social learning theory and the assumption that children learn behaviors through direct rewards or punishments or by watching others. According to this theory, physically abused children are thought to learn to use aggression and violence by watching their parents use aggression and violence. Tedeschi and Felson (1994) speculated that maltreated children may perceive aggression as an acceptable form of dealing with anger and punishment, fail to learn alternative and acceptable coping methods for dealing with negative emotions, and see their parents being rewarded for these aggressive behaviors.

In a review article (Widom, 1989c) titled, “Does Violence Beget Violence? A Critical Examination of the Literature,” I concluded that it was difficult to draw policy conclusions about the cycle of violence because of methodological limitations of the earlier empirical research. Since that time, several prospective studies in different parts of the United States have examined this relationship in research designs that have overcome many of the methodological problems of the earlier work. At least eight separate longitudinal studies have reported a relationship between childhood abuse and neglect and increased risk for violence:

In an early empirical paper on the “cycle of violence”, I (Widom, 1989b) reported that children with documented cases of child abuse and/or neglect were at increased risk of arrest for a violent crime, compared with a matched control group of nonabused and non-neglected children. Although not often cited, we found that having a history of CAN doubled the risk of arrest for violence for girls (odds ratio [OR] = 2.38, 95 percent confidence interval = 1.22–4.63) (Maxfield and Widom, 1996).

A study conducted in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina (Zingraff et al., 1993), investigated children with court cases of maltreatment and compared them with two other samples: a general sample and an impoverished sample recruited through the county Department of Social Services. Zingraff et al. found that maltreated children had more arrests at 15 years of age, relative to both comparison samples. The maltreated children also had more arrests for violence than the school sample but not compared with the impoverished sample.

Analyzing data from the Rochester (New York) Youth Development Study, Smith and Thornberry (1995) found that abused and neglected children had more self-reported and officially documented cases of violent delinquency compared with nonabused and non-neglected children, controlling for sex, race, and family structure.

Herrenkohl, Egolf, and Herrenkohl (1997) studied maltreated and nonmaltreated preschool children in Pennsylvania, following them for 16 years to determine their involvement in assaultive behavior. These authors found that severity of physical discipline and sexual abuse as well as negative aspects of the mother’s interaction predicted adolescent assaultive behavior.

In the Pittsburgh Youth Study, abused and neglected boys were more likely to self-report violence and delinquency than nonmaltreated boys (Stouthamer-Loeber et al., 2001).

English, Widom, and Brandford (2001) studied a group of children abused and neglected between 1980 and 1985 in the Northwest region of the United States, finding that children with substantiated cases of abuse and neglect were 11 times more likely than matched controls to be arrested for a violent crime as a juvenile, 2.7 times more likely as an adult, and 3.1 times more likely to be arrested for a violent crime as either a juvenile or an adult.

Using data from multiple sites, Lansford et al. (2007) reported that children who had been physically abused had significantly more court records of violent offenses than nonabused peers, even after controlling for several variables including socioeconomic status.

Mersky and Topitzes (2010) used data from the Chicago Longitudinal Study, a panel study of 1,539 minority children from economically disadvantaged families who were originally assessed in preschool and followed up at approximate 24 years of age, to examine associations between childhood maltreatment and several outcomes. Although rates of crime and incarceration were high in the sample overall, maltreatment was a significant predictor of being arrested.

These studies varied in terms of geographic region, time period, youths’ ages, sex of the children, definition of child maltreatment, and assessment technique. Yet these prospective investigations provide evidence that childhood maltreatment increases later risk for delinquency and violence. Because the limitations of any one study may impact the interpretation of findings, conclusions from research are strengthened through replication (Taubes, 2007). Thus, the replication of this fundamental relationship across several well-designed studies supports the generalizability of these results and increases confidence in them.

I drew several important lessons from this body of research on the cycle of violence:

Child abuse and/or neglect increases a person’s risk not only for delinquency and adult crime but also for violence. This increase in risk affects abused and neglected girls as well as maltreated boys, doubling the risk of violence for abused and neglected girls.

Despite the fact that CAN clearly plays a role as an antecedent to violence, this relationship is not inevitable or deterministic. Most maltreated children in my sample (and in other studies) did not become violent. At the mean age of 32.5 years, 82 percent of the maltreated children in our sample did not have an arrest for violence, although this percentage varied by demographic characteristics of the individuals.

In addition to physically abused children, neglected children are at increased risk for violence. Few theories (with the exception of strain) offer explanations for neglect as a risk factor for violence.

Violence occurs without a history of CAN (that is, 14 percent of the children without histories of abuse and neglect had arrests for violence).

Thus, despite the increase in risk associated with CAN, not all abused and neglected children become violent and not all violent offenders have a history of CAN. There are, therefore, at least two groups of violent offenders—those with a history of CAN and those who do not have an official history of CAN—for whom the mechanisms and processes leading them to violence may differ.

VIOLENCE AND POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Violence also occurs in individuals with PTSD. PTSD (adapted from National Institutes of Mental Health, n.d.) develops after a major “traumatic” event involving physical harm or the threat of physical harm. Normally, what has been called the “fight-or-flight” response protects a person from harm. However, people with PTSD may feel stressed or frightened even when they are no longer in danger. Briefly, the symptoms of PTSD include 1) reexperiencing—flashbacks, bad dreams, and frightening thoughts; 2) avoidance—avoid places, lose interest, feel “numb,” become depressed, and worry; and 3) hyperarousal—easily startled, feeling “on edge,” and angry outbursts. From a criminological perspective, one might ask whether the hyperarousal or hypervigilance associated with PTSD is the same phenomenon as what others have labeled “reactive aggression” (see earlier discussion). The existing literature focusing on the extent to which violence occurs in conjunction with PTSD can be grouped roughly into three subliteratures as illustrated in the next section.

PTSD AND VIOLENCE AMONG MENTALLY ILL INDIVIDUALS

There has been a long tradition of studying violence among mentally ill individuals (Monahan, 1992; Teplin, 1983), whereas there has been a more recent focus on PTSD in particular. For example, one study of forensic inpatients who had committed serious violent and sexual crimes reported that 9 of 27 patients (33 percent) were diagnosed with PTSD. Of the whole sample, those who had committed more violent crimes like murder and manslaughter had more PTSD symptoms than other violent criminals, and violent criminals had more PTSD symptoms than sexual offenders (Gray et al., 2003). In another study, Papanastassiou et al. (2004) examined a sample of mentally ill offenders who had committed homicide and found that 11 of 19 (58 percent) developed PTSD after their index offense and the offense was perceived as traumatic. Thus, at least one study suggested that PTSD may occur after a history of violence or in response to perpetrating a particularly violent offense.

PTSD ASSOCIATED WITH COMBAT EXPOSURE IN MILITARY PERSONNEL

Interest in the extent to which military personnel who have PTSD or traumatic brain injury engage in violence has been heightened by events such as the deadly rampage at Fort Hood in November 2009, the shooting spree in September 2013 that left 12 people dead at the Washington Navy Yard, and two separate incidents of killing and wounding at Fort Hood in April 2014. This issue is significant. Nearly two million U.S. personnel have been deployed since the commencement of the Iraq war (Polusny et al., 2011), and this figure does not account for previous war veterans.

A body of research has shown an association between PTSD and violence and aggressive acts in veterans (Begic and Jokic-Begic, 2001; Hartl et al., 2005; Jakupcak et al., 2007; Kulka et al., 1990; Lasko et al., 1994; McFall et al., 1999; Taft et al., 2007). More recent research has begun to examine the extent to which military service may be a risk factor for violence. It also is recognized that this research needs to control for preservice predispositions and mental health problems (Black et al., 2005; Yager, Laufer, and Gallops, 1984). Booth-Kewley et al. (2010) examined factors associated with antisocial behavior in combat veterans using a sample of Marines enlisted in the U.S. armed forces who had been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan between 2002 and 2007, and they found that combat exposure was positively and significantly associated with antisocial behavior, after controlling several potential confounders. Killgore et al. (2008) studied 1,252 Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans regarding their combat experiences when they returned from deployment and 3 months later, and it was found that specific combat experiences (e.g., exposure to violent combat and killing another person) predicted high levels of risk taking after these veterans returned home, despite controlling for age, sex, and other relevant sociodemographic factors. In a recent review chapter, MacManus and Wessely (2012) concluded that numerous questions remain about the extent to which these relationships are primarily the result of combat experiences or preexisting characteristics of the individual. They argued that a prospective study would be necessary to establish the temporal sequence of the combat trauma, development of PTSD, and subsequent violent behavior. To quote these authors: “As yet, all of the studies have collected data cross-sectionally and cannot therefore address this issue” (2012: 278). The military is currently in the process of investigating these relationships in prospective studies.

PTSD IN BATTERED WOMEN WHO MURDER THEIR SPOUSES

A third body of research has focused on the relationship between PTSD and violence in battered women. Dutton et al. (1994) found that battered women who had attempted murder or had successfully murdered their abusive spouse had more severe PTSD than a clinical sample of battered women with PTSD who had not attempted murder. O’Keefe (1998) compared battered women who killed their abusers and those incarcerated for other offenses and found that the battered women who had killed or seriously assaulted their batterers experienced more frequent and severe spousal abuse than those in the comparison group. Although the battered women did not report more current PTSD symptoms, O’Keefe found that childhood sexual and physical abuse and past PTSD symptoms predicted present PTSD symptomatology. Roberts (1996) studied a group of incarcerated battered women who had killed their batterers and a community sample of nonviolent battered women. Compared with the community sample, the battered women who killed their abusive partners were more likely to have experienced childhood sexual abuse, dropped out of high school, had an erratic work history, experienced a drug problem, and had access to the batterer’s guns.

Thus, these three separate streams of research suggest an association between PTSD and violence; however, the temporal order of these associations is ambiguous. That is, PTSD may occur first, increasing risk for violence or violence may occur before the PTSD, representing the qualifying event that leads to a person’s PTSD.

CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT AS RISK FACTORS FOR PTSD

Research also has shown that child abuse is implicated as a risk factor in the development of PTSD. In the epidemiological literature, numerous cross-sectional studies have reported associations between retrospective reports of childhood abuse or childhood adversities and PTSD. For example, Breslau (2009; Breslau et al., 1999) reported that the likelihood of developing PTSD increased as the number of experienced traumatic events increased. In the National Comorbidity Study (Kessler et al., 1995), women with PTSD reported rape and childhood sexual abuse as the most upsetting traumatic events ever experienced, and 7–8 percent of men and women with PTSD reported childhood physical abuse as the most upsetting trauma experienced.

In our prospective cohorts design study, I (Widom, 1999) found that individuals with documented histories of childhood physical or sexual abuse or neglect were at increased risk for a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD when followed up and assessed in young adulthood at approximately 29 years of age. Specifically, 30.9 percent of the abuse/neglect group met the criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD, compared with 20.4 percent of the matched control group and 37.5 percent of those with histories of sexual abuse, and 32.7 percent of those with histories of physical abuse. 30.6 percent of histories of neglect met lifetime criteria for PTSD. At the same time, it is important to note that not everyone exposed to childhood traumas developed PTSD.

VARIETIES OF VIOLENT BEHAVIORS

Reviewing these three distinct literatures and research showing bivariate relationships among CAN, PTSD, and violence led me to ask whether a further examination of these phenomena might lead to a better understanding of violence by focusing on varieties of violent behavior. Drawing on these literatures, I hypothesized that there are four distinct groups of violent offenders that may differ across several relevant characteristics and patterns of offending. In this address, I describe the results of this exploratory and descriptive examination rather than report on a formal test of specific hypotheses, particularly because some of the groups are notably small. However, if these varieties of violent behavior are found to be distinct and their differences are meaningful, then I hope others will consider these varieties in their own work and conduct more systematic analyses.

The four varieties of violent behaviors include one group without a documented history of CAN and three groups with histories CAN. I defined four varieties of violent offenders using age of documented cases of CAN, age of onset of PTSD, and age of first violent arrest in a temporally correct manner, so that CAN precedes the onset of PTSD or violence and, in turn, the PTSD or violence comes before or after the other. The four varieties of violent behaviors are defined as violence only, CAN → violence, CAN → PTSD → violence (PTSD first), and CAN → violence → PTSD (violence first).

The first variety contains individuals who had arrests for violence but no history of CAN or PTSD. I refer to this group as violence only (no CAN and no PTSD). Although the individuals in this group have not received much attention, several theories (subcultural, rational choice, and social learning theories) provide possible explanations for such a group. In addition, one would expect that the characteristics of this group and the antecedents of their violence may be quite different than the causes of violence in the CAN or PTSD groups.

The second variety represents the group of abused and neglected children who become violent at some point later in their lives but do not develop PTSD. I refer to this variety as child abuse and neglect → violence (CAN → violence). This group is the focus of many studies that have been conducted to examine the cycle of violence.

The last two varieties involve individuals who were abused and/or neglected as children and then subsequently develop PTSD and become violent. It is expected that these two PTSD groups will be small. However, the question posed here is whether they represent one group with PTSD or two meaningful and distinct PTSD groups with differences in the onset of PTSD or whether they are not different at all from the other violent offenders with histories of CAN.

The third variety represents individuals who have histories of child abuse and neglect, have developed PTSD, and subsequently have been arrested for violence. This third variety is labeled child abuse and neglect → PTSD → violence (CAN → PTSD → violence). For these individuals, the PTSD occurred after the CAN but before the first incidence of recorded violence (that is, these are individuals with “PTSD first”). This temporal sequence might explain the behavior of some of the battered women who shot or killed spouses or partners, assuming that the PTSD existed before the violence and that there was a history of CAN.

The fourth variety represents those individuals who have histories of CAN, engage in violence early in life, and subsequently develop PTSD. I refer to this group as child abuse and neglect → violence → PTSD (CAN → violence → PTSD). Although most likely rare, the rationale for defining this variety is that it is possible that there are people who engage in extremely violent acts, or they engage in so many violent acts, that they develop PTSD as a consequence. As noted, at least one study has reported studying a group of mentally ill offenders who had developed PTSD after their violent index offense (Papanastassiou et al., 2004).

THE STUDY

DESIGN

To address these questions and examine these four types of violent offenders, I draw on data from a prospective cohort design study (Leventhal, 1982; Schulsinger, Mednick, and Knop, 1981) in which abused and neglected children were matched with nonabused and non-neglected children and then followed prospectively into adulthood. Notable features of the design include 1) an unambiguous operationalization of CAN; 2) a prospective design; 3) separate abused and neglected groups; 4) a large sample; 5) a comparison group matched as closely as possible on age, sex, race, and approximate social class background; and 6) an assessment of the long-term consequences of abuse and neglect beyond adolescence and into adulthood (Widom, 1989b).

The prospective nature of the study disentangles the effects of childhood victimization from other potential confounding effects. Because of the matching procedure, participants are assumed to differ only in the risk factor: that is, having experienced childhood neglect or sexual or physical abuse. Because it is obviously not possible to assign participants randomly to groups, the assumption of group equivalency is an approximation. The comparison group also may differ from the abused and neglected individuals on other variables nested within abuse or neglect.

The first phase of this research began as a search of archival records to identify a group of abused and neglected children and matched controls. Then, a criminal history search was conducted to assess the extent of delinquency, crime, and violence (Widom, 1989b). Subsequent phases of the research involved tracing, locating, and interviewing the abused and/or neglected individuals (22–30 years after the initial court cases for the abuse and/or neglect) and the matched comparison group. The four follow-up in-person interviews were approximately 2–3 hours long and consisted of standardized tests and measures.

Throughout all waves of the study, interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study, to the inclusion of an abused and/or neglected group, and to the participants’ group membership. Similarly, the participants were blind to the purpose of the study. Participants were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals who grew up in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the procedures involved in this study, and participants who participated signed a consent form acknowledging that they understood the conditions of their participation and that they were participating voluntarily.

PARTICIPANTS

The rationale for identifying the abused and neglected group was that their cases were serious enough to come to the attention of the authorities. Only court-substantiated cases of CAN were included. Cases were drawn from the records of county juvenile and adult criminal courts in a metropolitan area in the Midwest during the years 1967 through 1971 (N = 908). To avoid potential problems with ambiguity in the direction of causality and to ensure that the temporal sequence was clear (that is, CAN → subsequent outcomes), abuse and neglect cases were restricted to those in which children were less than 12 years of age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Physical abuse cases included injuries such as bruises, welts, burns, abrasions, lacerations, wounds, cuts, bone and skull fractures, and other evidence of physical injury. Sexual abuse charges included felony sexual assault, fondling or touching in an obscene manner, rape, sodomy, and incest. Neglect cases reflected a judgment that the parents’ deficiencies in childcare were beyond those found acceptable by community and professional standards at the time. These cases represented extreme failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention to children.

A critical element of this design was the establishment of a comparison or control group, matched as closely as possible on the basis of sex, age, race, and approximate family socioeconomic status during the time period under study (1967 through 1971). To accomplish this matching, the sample of abused and neglected cases was first divided into two groups based on their age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Children who were younger than school age at the time of the abuse or neglect were matched with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (±1 week), and hospital of birth through the use of county birth record information. For children of school age, records of more than 100 elementary schools for the same time period were used to find matches with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (±6 months), same class in same elementary school during the years 1967 through 1971, and home address, within a five-block radius of the abused or neglected child, if possible. Overall, there were 667 matches (73.7 percent) for the abused and neglected children.

Matching for social class is important because it is theoretically plausible that any relationship between child abuse or neglect and later outcomes is confounded or explained by social class differences (Bradley and Corwyn, 2002; Conroy, Sandel, and Zuckerman, 2010; MacMillan et al., 2001; Widom, 1989a). It is difficult to match exactly for social class because higher income families could live in lower social class neighborhoods and vice versa. The matching procedure used here is based on a broad definition of social class that includes neighborhoods in which children were reared and schools they attended. Shadish, Cook, and Campbell (2002) recommend using neighborhood and hospital controls to match on variables that are related to outcomes when random sampling is not possible. Busing was not operational at the time, and students in elementary schools in this county were from small, socioeconomically homogeneous neighborhoods.

If the control group included individuals who had been officially reported as abused or neglected, then this would jeopardize the design of the study. Official records were checked, and any proposed comparison group child who had an official record of childhood abuse or neglect was eliminated. In these cases (n = 11), a second matched person was assigned to the control group to replace the individual excluded. Despite these efforts, it is possible that some members of the control group may have experienced unreported abuse or neglect.

In the first follow-up interviews (1989–1995), 1,307 (83 percent) participants were located and 1,196 (76 percent) were interviewed. Subsequent follow-up interviews were conducted in 2000–2002 (n = 896) and in 2003–2005, when another follow-up interview and medical status examination were conducted (n = 808). Initially, the sample was approximately half male (49.3 percent) and half female (51.7 percent) and approximately two thirds White (66.2 percent) and one third Black (32.6 percent). Although there has been attrition associated with death, refusals, and our inability to locate individuals over the various study waves, the composition of the sample at the four time points has remained about the same. The abuse and neglect group represented 56–58 percent at each time period; White, non-Hispanics were 60–66 percent; and males were 47–51 percent of the samples. There were no significant differences across the samples on these variables or in mean age across the four phases.

The average highest grade of school completed for the sample at the first interview was 11.47 (standard deviation [SD] = 2.19). The occupational status at the time of the first interview was coded according to the Hollingshead Occupational Coding Index (Hollingshead, 1975). The median occupational level of the sample was semiskilled, and less than 7 percent of the overall sample was in levels 7–9 (managers through professionals). Thus, most of the sample is at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum.

MEASURES AND VARIABLES

Violent Offending

Records from three levels of law enforcement (local, state, and federal) agencies were searched for arrests during 1987–1988 (Widom, 1989b) and again in 1994 (Maxfield and Widom, 1996). Arrests for violence include murder/attempted murder, manslaughter and involuntary manslaughter, reckless homicide, rape, sodomy, robbery/robbery with injury, assault, assault and battery, aggravated assault, and battery/battery with injury. The age at first arrest and age at first violent arrest were based on information from the official records.

Self-reports of violence were based on responses to two different measures—the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979) and violence items from Wolfgang and Weiner (1989). For the CTS, participants were asked about their actions toward family members in the context of methods of handling disagreements. Scales developed by Straus and Gelles (1990) for Minor Violence, Severe Violence, and Very Severe Violence are reported. In the second self-report of violence measure, participants were asked whether they had ever engaged in a variety of violent behaviors. Seven items reflect “severe violence,” including 1) hurt someone badly enough he or she required medical attention, 2) threatened someone because he or she wouldn’t give you money or something else, 3) used a weapon to threaten someone, 4) attacked someone with the purpose of killing him or her, 5) used physical force to get money or drugs, 6) forced someone to have sex with you, and 7) shot someone.

Demographic Characteristics, IQ, Academic Performance, and Social Indicators

Information was available from the original court records about the age at the time of the abuse/neglect petition. During the first interview (1989–1995), information about a person’s age, sex, and ethnicity was collected, and participants’ IQ and reading ability were assessed. IQ was measured by the Quick Test (Ammons and Ammons, 1962), an easily administered measure of verbal intelligence where the participant can point to a picture on a card. Quick Test scores correlate highly with WAIS full scale (.79–.80) and verbal (.79–.86) IQs (Dizzone and Davis, 1973), and versions have been used with a variety of populations. Reading ability was measured by the Wide Range Achievement Test-Revised (WRAT-R; Jastak and Wilkinson, 1984). WRAT-R internal consistency estimates range from .96 to .99, and concurrent validity with other achievement and ability tests ranges from the high .60s to .80s (Jastak and Wilkinson, 1984). For the measure of high-school graduation, participants were asked about their highest level of school completed at the time of the interview. The information was then dichotomized to indicate whether each participant had graduated from high school. At each interview, participants also were asked about their marital and employment status to track changes over time. Homelessness was assessed based on a person’s response to a question during the first interview (1989–1995) about whether he or she had ever “experienced a period of time when they had no regular place to live for at least a month.”

Family Characteristics

Information about characteristics of the family was based on responses to questions during the first interview about whether the participant had grown up in a single-parent household or had lived with both natural (biological) parents until 18 years of age, the family had received welfare when the person was a child, either parent or siblings had ever been arrested, and either parent had an alcohol or drug problem.

Trauma and Victimization History

The Lifetime Trauma and Victimization History (LTVH) instrument (Widom et al., 2005) was administered during the second interview (2000–2002). The LTVH is a 30-item structured interview that asked participants about “serious events that may have happened to you during your lifetime.” The LTVH demonstrates good predictive, criterion-related, and convergent validity and a high level of agreement between earlier and current reports of certain types of traumas (Widom et al., 2005).

Retrospective Reports of Child Abuse and Neglect

Retrospective self-reports of childhood physical and sexual abuse were collected during the first interview (1989–1995) (see Widom and Morris, 1997, and Widom and Shepard, 1996, for details of the self-report measures). Neglect was assessed during the same interviews with three items that asked whether 1) neighbors fed or cared for you because your parents didn’t get around to shopping or cooking, 2) anyone ever said you weren’t being given enough to eat or kept clean enough or getting medical care when needed, and 3) you were left home alone when you were a very young child while your parents were out shopping or doing something else.

Psychiatric Disorders and Psychopathology

At the first interview (1989–1995), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Diagnostic Interview Schedule-III-Revised (DIS-III-R; Robins et al., 1989) was used to assess several psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD) (Widom, DuMont, and Czaja, 2007), generalized anxiety disorder, dysthymia, PTSD (Widom, 1999), antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), alcohol abuse and/or dependence (Widom, Ireland, and Glynn, 1995), and drug abuse and/or dependence (Widom, Weiler, and Cottler, 1999). The DIS-III-R is a fully structured interview schedule designed for use by lay interviewers. The interviewers received an intensive week of training and were experienced in the administration of the DIS-III-R, which has been used in prior community-based studies of psychiatric disorders and demonstrates adequate reliability and validity (Leaf and McEvoy, 1991). Computer programs for scoring the DIS-III-R were used to compute DSM-III-R diagnoses.

At the second interview (2000–2002) when the participants were mean age 39.5 years, participants were assessed on the extent to which they were experiencing current symptoms of anxiety, depression, and dissociation. The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck and Steer, 1990), a 21-item self-report scale developed to measure the severity of anxiety in clinical populations, has been used extensively in research with nonclinical samples and was used in this study. Respondents were asked to rate how much they have been bothered by each of the symptoms over the past week on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely—it bothered me a lot). The BAI has been shown to have high internal consistency and test–retest reliability as well as good concurrent and discriminant validity (Beck et al., 1988). The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), a 20-item self-report scale, was used to measure depressive symptomatology in the general population. Respondents indicated how often within the past week they experienced the symptoms, with responses ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). The scale has been tested in household interview surveys and in psychiatric settings, and it was found to have high internal consistency and adequate test–retest reliability (Radloff, 1977). The Dissociation Experiences Scale was developed by Bernstein and Putnam (1986) to measure dissociation in normal and clinical populations. Scale items asked about experiences such as “not feeling like your real self” and “watching yourself from far away” (each scored for the last 12 months).

FINDINGS

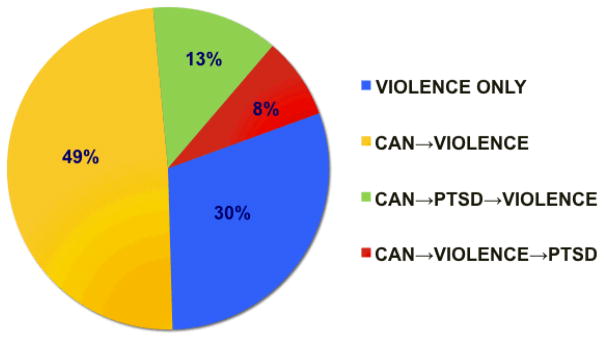

Figure 1 presents the distribution of the four varieties of violent offenders. Of all the violent offenders (N = 196), the largest group—about two thirds (69.9 percent, n = 137)—is composed of individuals who have histories of CAN. The next largest group (30.1 percent, n = 59) represents those individuals who are violent only and have no documented histories of child abuse or neglect and no PTSD. Within the CAN group, the two PTSD groups together represent about one fifth of the sample (21 percent): CAN → PTSD → violence = 12.8 percent (n = 25) and CAN → violence → PTSD = 8.2 percent (n = 16).

Figure 1.

Varieties of Violent Behavior (N = 196)

Because of the small sample size of the two PTSD groups, statistical power is limited. Analyses of variance and logistic regressions were used to compare the four varieties of violent offenders. Findings that may not meet conventional standards of significance, but have substantial ORs, will occasionally be noted to suggest trends worth consideration in the future. In some analyses, there is a fifth group that represents what I am calling the “none” group (defined as no CAN history, no PTSD, and no violence). The “none” group is used as a reference point for comparisons with the violent offenders in the sample. In addition to overall comparisons, pairwise comparisons were computed and significant comparisons are indicated with letters (a, b, c, etc.) reflecting differences across the varieties of violent offenders and the “none” group. When two groups have different letters, this indicates that they are significantly different on that characteristic (p < .05). If two groups have the same letter, then they do not differ.

AGE OF ONSET, EXTENT, AND TYPES OF VIOLENT OFFENDING

The first set of results focuses on the age of onset, extent, and types of violent offending among the four varieties of violent offenders (see table 1). If the varieties have any discriminant validity, then there should be differences in these characteristics. Looking at the age of onset of first arrest, it is striking that the small CAN → violence → PTSD variety (“violence first”) has the youngest age of first arrest for any crime (mean age = 15.0 years) and for a violent crime (mean age = 18.1 years). The CAN → violence group has the next youngest age of onset of criminal behavior and does not differ significantly from the CAN → violence →PTSD. The other three groups do not differ from one another (they all have the letter “c” after the percent). Another noteworthy finding is that the age of first arrest for the violence-only variety is similar to the none group and later in onset than the “violence first” group, CAN → violence → PTSD). In terms of the number of arrests, the CAN → violence and CAN → violence →PTSD groups have the highest mean number of any arrests and arrests for violence. In contrast, the violence-only group and the CAN → PTSD → violence groups have a smaller number of any arrests and arrests for violence.

Table 1.

Age of Onset, Extent, and Types of Violent Offending for Four Varieties of Violent Behavior

| Age of Onset (Mean) | None (n = 355) | Violence Only (n = 59) | CAN -> Violence (n = 96) | CAN-> PTSD-> Violence (n = 25) | CAN-> Violence - > PTSD (n = 16) | Overall p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first arrest | 20.4c | 19.6c | 16.9a,b | 19.3b,c | 15.0a | *** |

| Age at first violent arrest | NA | 23.1b | 21.7a,b | 24.1b | 18.1a | *** |

| Number of arrests | 0.9a | 7.2b | 11.5c,d | 8.6 b, c | 12.1d | *** |

| Number violent arrests | NA | 1.8 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Type of Violent Arrests (percent) | Violence Only | CAN -> Violence | CAN-> PTSD-> Violence | CAN-> Violence - > PTSD | Overall p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggravated assault | 0.0 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 12.5 | |

| Assault | 8.5 | 6.2 | 16.0 | .0 | |

| Assault with battery | 8.5a | 9.4a | 4.0a | 31.2b | *** |

| Battery | 62.7 | 60.4 | 52.0 | 56.2 | |

| Battery with injury | 22.0 | 17.7 | 20.0 | 6.2 | |

| Murder, attempted murder, or manslaughter | 3.4 | 9.4 | 12.0 | 6.2 | |

| Rape, sodomy | 11.9 | 12.5 | 4.0 | 18.8 | |

| Robbery with injury | 1.7 | 3.1 | .0 | 6.2 |

NOTES: n = number in subsample; NA = not applicable. The none group contains individuals with no history of CAN, PTSD, or an arrest for violence. The letters (a, b, c) reflect differences or lack of differences in pairwise comparisons. When two groups have different letters, they are significantly different from one another on that characteristic at p < .05.

p < .001.

The bottom half of the table shows the types of violent offenses for which these four varieties of violent offenders have been arrested. As might be expected, the cell sizes for the types of violent arrests are small with many of the cells containing less than five people. However, an inspection of the odds ratios may be valuable here even though the confidence intervals (CI) are large. The CAN → violence → PTSD group has the highest percentage with an arrest for aggravated assault (12.5 percent, OR = 4.43, 95 percent CI = .68–28.89), assault with battery (31.2 percent, OR = 4.91, 95 percent CI = 1.21–19.89), and rape/sodomy (18.8 percent, OR = 1.71, 95 percent CI = .39–7.55), compared with the violence-only offenders. The CAN → PTSD → violence (“PTSD first”) group has the highest percentage with an arrest for murder or attempted murder (12.0 percent, OR = 3.89, 95 percent CI = .61–24.86) and assault (16.0 percent, OR = 2.06, 95 percent CI = .50–8.41), compared with the violence-only group. The violence-only and the CAN → violence groups are fairly comparable in terms of types of violent arrests, with only murder and attempted murder showing a higher percentage for the CAN → violence group (9.4 percent) compared with the violence-only group (3.4 percent) (OR = 2.59, 95 percent CI = .53–12.64).

Thus, on the basis of these patterns of offending and violent offending, these results suggest that there are substantial differences among the four varieties of violent offenders in terms of age of onset, extent, and patterns of violent offending.

SELF-REPORTS OF VIOLENCE

Given the debate in the literature about the validity of official arrest versus self-report data on crime and violence (Maxfield, Weiler, and Widom, 2000) and because these varieties have been determined on the basis of arrests for violence, it is possible that these varieties of violent behavior reflect some biases in the criminal justice system and not real differences in violent behavior. For this reason, I examined the extent to which self-reports of violence produced similar or different patterns compared with the official arrest data, shown in table 2. The none group has the uniformly lowest rates of self-reports of minor, severe, and very severe violence on the Conflicts Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979) and on the self-report of violence items from the Wolfgang and Weiner (1989) scale. The CAN → violence → PTSD variety reports the highest frequency on both self-report indicators. Although slightly higher, the violence-only group does not differ significantly from the none group for any of the self-reports of violence. On these self-reports, the violence-only and the CAN → violence groups do not differ, but both groups report lower rates than the two PTSD groups. In sum, in addition to differences in age of onset, extent, and types of violent offenses based on official arrest data, these four varieties of violent offenders differ substantially in terms of self-reported violent behavior. It does not appear as if the none group has been engaged in substantial violence that has been missed because of our reliance on official arrest data.

Table 2.

Self- Reports of Violence by Four Varieties of Violent Offenders

| Measure (Mean) | None (n = 355) | Violence Only (n = 59) | CAN--> Violence (n = 96) | CAN--> PTSD --> Violence (n = 25) | CAN-> Violence -> PTSD (n = 16) | Overall p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within Family (Frequency) | ||||||

| CTS: Minor violence | .7a | .9a,b | 1.3a,b | 1.5b | 1.6b | *** |

| CTS: Severe violence | .2a | .4a | .5a,b | .6a,b | 1.0b | *** |

| CTS: Very severe violence | .2a | .4a | .4a,b | .5a,b | 1.0b | *** |

| Self-Reports of Violent Behaviors | ||||||

| Number of types | .3a | .81a,b | 1.15b,c | 1.5c | 1.4b,c | *** |

| Frequency | .3a | 1.08a,b | 1.63b,c | 2.1c | 2.1b,c | *** |

PTSD, or an arrest for violence. The letters (a, b, c) reflect differences or lack of differences in pairwise comparisons. When two groups have different letters, they are significantly different from one another on that characteristic at p < .05.

p < .001.

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS, IQ, ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE, AND SOCIAL INDICATORS

Table 3 shows the demographic characteristics of the four varieties of violent offenders and the none group for comparison. The first striking finding is that the violence-only group differs from all other groups (including the none group) in having the lowest percentage of females and being almost exclusively male (only 3.4 percent female). The CAN → violence group also has a lower percentage of females, whereas the none and CAN → PTSD → violence groups have higher rates of females. In terms of race/ethnicity, only the none group differed from all others and had a significantly larger proportion of White, non-Hispanic individuals. Of the three groups with histories of CAN, there were no differences in the mean age at the time of the abuse or neglect petition (6.55, 6.76, and 7.62 years of age).

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics, IQ, Academic Performance, and Social Indicators

| Characteristic | None (n = 355) | Violence Only (n = 59) | CAN--> Violence (n = 96) | CAN--> PTSD --> Violence (n = 25) | CAN-> Violence -> PTSD (n = 16) | Overall p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (percent female) | 49.3a | 3.4c | 19.8b | 36.0a,b, d | 25.0a,b, d | *** |

| Race/ethnicity (percent White, non- Hispanic) | 66.2a | 42.4 | 36.5 | 36.0 | 56.2 | *** |

| Age at abuse/neglect petition (years) | NA | NA | 6.6 | 6.8 | 7.6 | |

| IQ (standardized score) | 95.1c | 89.9b,c | 84.3a,b | 79.7a | 85.1a,b | *** |

| Reading ability (raw score) | 56.2a | 45.8b | 41.4b | 42.0b | 36.1b | *** |

| Reading ability (percent deficient or borderline) | 34.6a | 62.1b | 72.9b,c | 72.0b,c | 93.3c | *** |

| Highest grade of school completed | 12.4b | 11.4a,b | 10.8a | 10.5a | 10.3a | *** |

| High-school graduate (percent) | 73.5 | 52.5 | 38.5 | 40.0 | 43.8 | |

| Currently married, mean age = 29.2 years (percent) | 52.1a | 33.9b | 21.9b,c | 12.0c | 18.8b,c | *** |

| Currently married, mean age = 39.5 years (percent) | 57.0a | 36.4b | 19.7b | 13.6b | 7.7b | *** |

| Employed, mean age, 29.2 years (percent) | 78.3a | 69.5a | 41.7b | 28.0b,c | 12.5c | *** |

| Regularly employed, mean age = 39.5 years (percent) | 84.1a | 72.7a,b | 44.3b | 40.9b | 46.2b | *** |

| Homeless, mean age = 29.2 years (percent) | 7.9a | 18.6b | 26.3b,c | 52.0d | 43.8c,d | *** |

NOTES: n = number in subsample. The none group contains individuals with no history of CAN, PTSD, or an arrest for violence. The letters (a, b, c) reflect differences or lack of differences in pairwise comparisons. When two groups have different letters, they are significantly different from one another on that characteristic at p < .05.

p < .001.

Table 3 also presents findings about the four varieties of violent offenders in terms of cognitive and intellectual ability and other behavioral and social indicators. In terms of IQ, reading ability, and likelihood of graduating from high school, the pattern is fairly similar. There is a clear decline in IQ, reading ability, and high-school graduation from the none group to the violence only to the three CAN groups. Given their backgrounds and documented court cases of maltreatment, it is not surprising that the three CAN groups show lower rates of high-school graduation than the violence-only group and the none group. It is particularly striking that the CAN → violence → PTSD group has by far the highest percentage of deficient or borderline reading ability of all groups (93.3 percent).

In terms of other social and behavior indicators, the three CAN groups are less likely to be married and less likely to be employed at 29 years of age compared with the none and violence-only groups. At 40 years of age, all four varieties of violent offenders were less likely to be married than the none group, but they did not differ among themselves. For employment at 29 years of age and employment 10 years later (mean age = 39.5 years), the three CAN groups were significantly different than the none and violence-only groups, with the two PTSD groups least likely to be employed at both ages. A similar pattern of problematic behavior was observed for homelessness, with the none group having the lowest risk of being homeless compared with the two PTSD groups with the highest risk, and the violence-only and the CAN → violence group in between and not differing.

FAMILY CHARACTERISTICS

An inspection of table 4 reveals the extent to which the four varieties of violent offenders have problematic family histories and shows a pattern that has emerged across the findings presented thus far. Not surprisingly, the none group has the fewest risk factors in terms of family background—i.e., families with the lowest percentage of problems—and has the highest percentage of a childhood spent living with both (natural) parents. The violence-only group seems to have fewer risk factors than the other three varieties, to be more similar in terms of family characteristics to the none group, and to differ only in terms of being at greater risk for having parents on welfare. In contrast, the three other groups of violent offenders differ from the none and violence-only groups on most family characteristics, including the percentage with a mother arrested, with a father arrested, with a mother and/or father with an alcohol or drug problem, and having lived with both parents until 18 years of age. All four violent offender groups differ significantly from the none group on percentage with parents on welfare. The CAN → violence → PTSD group has the most risk factors—highest percentage of having a parent arrested, sibling arrest, mother with an alcohol or drug problem, and father with an alcohol or drug problem, and the lowest percentage living with both parents until 18 years of age. The CAN → PTSD → violence group has almost as many adverse family characteristics (higher on mother alcohol/drugs) but comes from a family slightly less likely to be on welfare. Again, the pattern of lowest risk in the none group to slightly higher risk in the violence-only group and highest risk in the three CAN groups is evident here in these family characteristics, although the CAN → violence → PTSD variety has the most risk factors.

Table 4.

Family Characteristics of Four Varieties of Violent Offenders

| Measure (percent) | None (n = 355) | Violence Only (n = 59) | CAN--> Violence (n = 96) | CAN--> PTSD --> Violence (n = 25) | CAN-> Violence - > PTSD (n = 16) | Overall p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents on welfare | 29.9a | 48.3c | 62.8b | 48.0b,c | 87.5b | *** |

| Mother arrested | 7.1a | 13.6a,b | 23.4b,c | 40.0c | 43.8c | *** |

| Father arrested | 24.3a | 32.1a | 38.9b | 39.1b | 60.0b | *** |

| Sibling arrested | .20a | .51a,b | .41a | .60a,b | 1.02b | *** |

| Mother alcohol or drug problem | 10.2a | 10.2a | 28.8b | 40.0b | 31.2b | *** |

| Father alcohol or drug problem | 29.9a | 32.1a | 46.7b | 30.4a,b | 66.7b | *** |

| Lived with both parents | 45.9a | 39.0a | 11.5b | 4.0b | 6.2b | *** |

NOTES: n = number in subsample. The none group contains individuals with no history of CAN, PTSD, or an arrest for violence. The letters (a, b, c) reflect differences or lack of differences in pairwise comparisons. When two groups have different letters, they are significantly different from one another on that characteristic at p < .05.

p < .001.

TRAUMAS AND VICTIMIZATIONS: LIFETIME AND RETROSPECTIVE REPORTS OF CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT

In terms of the number of lifetime traumas and victimizations these people have experienced, the picture is more mixed (see top part of table 5). For general traumas (defined as natural or human-made disaster, combat experience, serious accident, or exposure to dangerous chemicals) and being kidnapped or stalked, the groups do not differ significantly. However, for all types of traumas and victimization experiences, the ordering is similar: The two PTSD groups have the highest mean number, followed by the CAN → violence group, which is followed by the violence-only variety, and the none group, which has the lowest reported traumas and victimization experiences. In almost every category, the CAN → PTSD → violence variety has the highest mean number of traumas and victimizations, except for sexual assault. For sexual assault, the CAN → violence → PTSD group has the highest number. The violence-only group does not differ from the none group, although in contrast to expectations, the none group actually reports a slightly higher number of sexual assaults than the violence-only group.

Table 5.

Traumas and Victimization Experiences for Four Varieties of Violent Offenders

| Traumas and Victimizations | None (n = 355) | Violence Only (n = 59) | CAN--> Violence (n = 96) | CAN--> PTSD --> Violence (n = 25) | CAN-> Violence -> PTSD (n = 16) | Overall p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime Traumas and Victimization Experiences (Mean Number) | ||||||

| General traumas | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.0 | |

| Physical assault | 2.7a | 5.2a,b | 7.3b,c | 8.6c | 6.5b,c | *** |

| Sexual assault | .4a | .2a | .5a,b | 1.1b,c | 1.5c | *** |

| Family/friend murdered or suicide | .6a | 1.0a,b | 1.4a,b | 1.6b | 1.2a,b | *** |

| Witnessed trauma | 1.5a | 2.3a,b | 2.8a,b | 3.6b | 3.4b | *** |

| Crime victim | 2.9a | 4.4a,b | 5.8b,c | 6.8c | 4.7a,b,c | *** |

| Kidnapped/stalked | .3 | .2 | .3 | .6 | .3 | |

| Retrospective Reports of Childhood Abuse or Neglect (percent) | ||||||

| Physical abuse | 36.7a | 32.2a | 54.2b | 75.0b | 75.2b | *** |

| Sexual abuse | 10.7a | 8.6a | 14.6a | 36.0b | 43.8b | *** |

| Neglect | 9.9a | 13.6a | 41.8b | 52.2b | 50.0b | *** |

NOTES: n = number in subsample. The none group contains individuals with no history of CAN, PTSD, or an arrest for violence. The letters (a, b, c) reflect differences or lack of differences in pairwise comparisons. When two groups have different letters, they are significantly different from one another on that characteristic at p < .05.

p < .001.

There are numerous advantages to using documented cases of CAN, especially because this eliminates ambiguity about the occurrence of the childhood maltreatment. However, there is always a concern about unreported CAN in the backgrounds of participants in this study. The bottom half of table 5 shows the extent to which these five groups retrospectively report histories of CAN. The three CAN groups with documented cases of CAN report higher levels of physical abuse and neglect compared with the none and violence-only groups. The two PTSD groups report the highest rates of sexual abuse compared with the other three groups. Thus, there is discrimination among the varieties of violent offenders providing some validity to the distinctions between the groups. Looking at the top and bottom of table 5, these results also are consistent in showing the highest mean number of lifetime sexual assaults and the highest percentage who reported childhood sexual abuse by the two varieties of violent offenders with CAN and PTSD (CAN → PTSD → violence and CAN → violence → PTSD).

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY IN YOUNG AND MIDDLE ADULTHOOD

Table 6 shows the prevalence of psychiatric disorders for the four varieties of violent offenders using DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria and the none group for comparison. In addition to their PTSD, both PTSD groups (CAN → PTSD → violence and CAN → violence → PTSD) have a greater incidence of other psychiatric disorders, including depression, dysthymia, and generalized anxiety disorder (although the pairwise comparisons for generalized anxiety disorder were not significant). The varieties of violent offenders with CAN and PTSD also have the highest rates of having alcohol and drug diagnoses. The violence-only and CAN → violence groups have similar rates of psychiatric disorders but lower than the two PTSD groups. It is noteworthy that the four varieties of violent offenders do not differ among themselves on the extent of antisocial personality disorder, although all four varieties of violent offenders differ significantly from the none group.

Table 6.

Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders and Psychopathology for Four Varieties of Violent Offenders in Young and Middle Adulthood

| Psychiatric Disorders and Psychopathology | None (n = 355) | Violence Only (n = 59) | CAN--> Violence (n = 96) | CAN--> PTSD --> Violence (n = 25) | CAN-> Violence -> PTSD (n = 16) | Overall p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime DSM-III-R Diagnosis (percent) (Mean age = 29.2 years) | ||||||

| Major depression disorder | 15.2a | 15.2a | 12.5a | 60.0b | 50.0b | *** |

| Dysthymia | 3.1a | 6.8a | 7.3a | 40.0b | 31.2b | *** |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3.9 | 5.1 | 7.3 | 12.0 | 12.5 | |

| Alcohol abuse and/or dependence | 45.4a | 64.4b | 61.5b | 76.0b | 87.5b | *** |

| Drug abuse and/or dependence | 28.2a | 44.1b,c | 38.5b | 64.0c,d | 75.0d | *** |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 5.1a | 32.2b | 32.3b | 32.0b | 43.8b | *** |

| Current Psychopathology (Mean number of symptoms) (Mean age = 39.5 years) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 6.9a | 7.3a | 9.5a,b | 15.2b | 10.0a,b | *** |

| Depression | 9.1a | 11.3a,b | 15.0a,b, c | 20.2c | 16.4b,c | *** |

| Dissociation | 7.5 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 9.3 | 8.0 | p < .10 |

NOTES: n = number in subsample. The none group contains individuals with no history of CAN, PTSD, or an arrest for violence. The letters (a, b, c) reflect differences or lack of differences in pairwise comparisons. When two groups have different letters, they are significantly different from one another on that characteristic at p < .05.

p < .001.

The bottom half of table 6 shows that the psychopathology remains in middle adulthood. The CAN → PTSD → violence group continues to report the highest level of symptoms of anxiety and depression. The violence-only group is more similar to the none group than to the other three groups of violent offenders.

SUMMARY PATTERN OF CHARACTERISTICS ACROSS THE FOUR VARIETIES OF VIOLENT OFFENDERS

Table 7 summarizes the varieties of violent offenders across many of the domains of functioning examined. Several points are worth noting. First, although they have not engaged in violence, the none group has substantial disadvantages in terms of family characteristics, histories of victimization, and drug abuse compared with what a general population sample might manifest. Second, on a number of characteristics, the violence-only group does not differ substantially from the none group, and this is particularly true for IQ, employment, living with both parents, and depression. Third, the three CAN varieties are more similar to one another than to the violence-only group in terms of offending, reading ability, family characteristics, histories of other traumas and victimization experiences, and employment. Fourth, the two CAN, Violence, and PTSD varieties manifest the most dysfunction and psychopathology. Finally, the CAN → violence → PTSD group has the earliest onset of violent offending, worse offending, most family risk factors, pathology, and inadequate social functioning. In sum, there are substantial differences among these varieties of violent offenders. The evidence suggests that aggregating these four distinct varieties into a larger group of violent offenders, particularly the two PTSD groups, would obscure important differences.

Table 7.

Summary Pattern of Characteristics Across the Four Varieties of Violent Offenders

| Characteristic | None (n = 355) | Violence Only (n = 59) | CAN→ Violence (n = 96) | CAN→P TSD→Violence (n = 25) | CAN→Violence →PTSD (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first arrest, mean (years) | 20.1 | 19.6 | 16.1 | 17.9 | 14.7 |

| Age at first violent arrest, mean (years) | NA | 23.1 | 21.7 | 24.1 | 18.1 |

| Number of violent arrests, mean (years) | NA | 1. 8 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Self-report very severe violence, mean (CTS) | .2 | .4 | .4 | .5 | 1.0 |

| Reading ability (percent deficient) | 22.5 | 46.6 | 58.3 | 60.0 | 86.7 |

| Homeless (percent) | 7.9 | 18.6 | 26.3 | 52.0 | 43.8 |

| Parents on welfare (percent) | 29.9 | 48.3 | 62.8 | 48.0 | 87.5 |

| Parent arrested (percent) | 27.7 | 39.3 | 49.6 | 62.5 | 73.3 |

| Siblings arrested (percent) | 55.3 | 61.8 | 74.5 | 87.0 | 100.0 |

| Father alcohol or drug problem (percent) | 29.9 | 32.1 | 46.7 | 30.4 | 66.7 |

| Physical assaults, mean number | 2.7 | 5.2 | 7.3 | 8.6 | 6.5 |

| Sexual assaults, mean number | .4 | .2 | .5 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| Crime victim, mean number | 2.9 | 4.4 | 5.8 | 6.8 | 4.7 |

| Major depression disorder (percent) | 15.2 | 15.3 | 12.5 | 60.0 | 50.0 |

| Drug abuse and/or dependence diagnosis (percent) | 28.2 | 44.1 | 38.5 | 64.0 | 75.0. |

| IQ (standardized score) | 95.1 | 89.9 | 84.3 | 79.7 | 85.1 |

| Highest grade school completed | 12.4 | 11.4 | 10.8 | 10.5 | 10.3 |

| Employed, mean age = 29.2 years | 78.3 | 69.5 | 41.7 | 28.0 | 12.5 |

| Lived with both parents | 45.9 | 39.0 | 11.5 | 4.0 | 6.2 |

NOTES: n = number in subsample. The none group contains individuals with no history of CAN, PTSD, or an arrest for violence.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

I believe that the results of these analyses support the proposition that the assumption of homogeneity in violent behavior is not warranted. At a minimum, these findings illustrate the need to acknowledge different developmental patterns and characteristics of violent offenders. Each variety of violent behavior warrants further consideration.

First, it is important to point out that slightly less than one third of the violent offenders in this study did not have histories of CAN. This variety of violence-only offenders was most similar to the none group (individuals who had no documented histories of CAN, no arrests for violence, and no PTSD), which is included for comparison purposes. The violence-only group did not differ from the none group in terms of age of first arrest, IQ, highest grade of school completed, being employed at 29.0 years of age, being regularly employed at 39.5 years of age, and family risk factors (having a father or sibling arrested, having a mother or father with an alcohol or drug problem, and living with both parents). The violence-only variety also did not differ from the none group in terms of prior traumas and victimization experiences across all categories, retrospective reports of CAN, or the prevalence of depression, dysthymia, or generalized anxiety disorder. However, they were more likely to have parents on welfare compared with the none group and to have diagnoses for alcohol and drug abuse and for antisocial personality disorder, which are characteristics typical of arrestees and incarcerated offenders.

I would suggest that these violence-only individuals, without histories of CAN, might have been inappropriately ignored in recent years compared with the numerous studies that focus on the link between CAN and violence. Given that the traditional risk factors associated with violence do not seem to characterize the violence-only group, it seems appropriate to ask what theories explain this variety of violent offender. Other than being male and experiencing family poverty, it is a challenge to explain why these individuals engage in violence. The subculture of violence theory may offer an explanation, considering that Wolfgang (1958) and Wolfgang and Ferracuti (1967) originally developed the subculture of violence theory to explain the delinquent behavior of young urban males. Alternatively, rational choice theory may provide an explanation for this violence given the high rates of poverty in this group. Hopefully, others will be stimulated by these findings to focus more attention on this variety of violent offender.

Second, CAN was present in the backgrounds of almost 70 percent of the violent offenders in this study. The varieties of violent offenders with documented histories of CAN were similar in many respects, including the age at abuse/neglect petition, lower IQ, reading ability, high-school graduation, marriage, and being regularly employed at 39.5 years of age. The three CAN varieties of violent offenders did not differ in terms of family characteristics (parents were on welfare, mother or father arrested, and mother or father with an alcohol or drug problem and living with both parents). The CAN → violence group (the largest of the varieties of violent offenders and those who did not develop PTSD) started criminal activity at an early age (early age at first arrest) and had among the highest number of arrests, the highest number of violent arrests, and among the highest reports of physical assaults, but they were less likely to report a history of sexual assaults and less likely to be homeless than the two CAN varieties with PTSD. Across many indicators, they were in between the none and violence-only varieties and the two CAN, PTSD, and violence varieties. The CAN → violence group has more risk characteristics than the violence-only group, but it is not as problematic as the two PTSD groups who themselves differ from one another. Given the totality of these characteristics, it is interesting that the CAN → violence variety has not developed PTSD. Are there certain characteristics or predispositions that might act to protect them?