Summary

Dietary composition has an important role in shaping the gut microbiota. In turn, changes in the diet directly impinge on bacterial metabolites present in the intestinal lumen. Whether such metabolites play a role in intestinal cancer has been a topic of hot debate. In this issue of Cancer Discovery, Bultman and colleagues show that dietary fiber protects against colorectal carcinoma in a microbiota-dependent manner. Furthermore, fiber-derived butyrate acts as an HDAC inhibitor, inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells experiencing the Warburg effect.

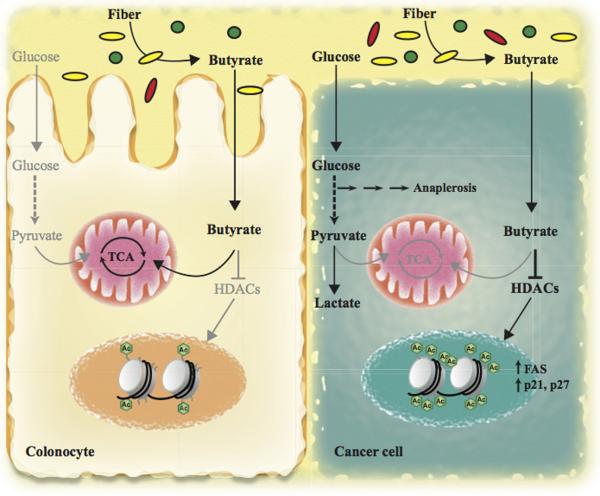

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer mortality in the world (1). This disease usually develops over many years via the accumulation of numerous genetic changes. Although some types of CRC are hereditary (2), most CRC cases are associated with diet and lifestyle (1). In line with this, the intestinal microbiota has been proposed to be a major contributor to the development of CRC (3). Increasing amount of data has demonstrated that dietary composition has an important effect on the gut microbiota, which, in turn, lead to changes in bacterial metabolites released to the intestinal lumen affecting intestinal tumorigenesis. In this context, dietary fiber is among the most studied components of the diet on the pathology of CRC. However, the role of fiber on CRC is controversial, mainly due to the fact that human cohort-based epidemiologic studies have yielded conflicting results. Furthermore, from those studies claiming a protective role, it is still unclear how fiber protects against CRC. Two possible mechanisms have been proposed. First, insoluble fiber may speed colonic transit decreasing the exposure time of the colonic epithelium to carcinogens, and, second, intestinal bacteria can metabolize soluble fiber into metabolites with protective action, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). In this issue, Donohoe et al. shed light on these controversies and elegantly demonstrate that, indeed, dietary fiber protects against CRC by increasing bacterial butyrate levels in the colon, which acts as a histone deacetylase inhibitor halting proliferation and promoting apoptosis of colon cancer cells (Figure 1; ref. 4).

High fiber diet leads to butyrate production in the colon by the action of butyrate-producing bacteria (depicted as yellow ovals), which is used by colonic epithelial cells as a primary source of energy. However, cancer cells use glucose to obtain energy and feed anaplerotic reactions (Warburg effect), leading to the accumulation of non-oxidized butyrate, which acts as a HDAC inhibitor, in turn increasing histone acetylation and expression of key pro-apoptotic and cell cycle regulatory genes suppressing tumor growth.

Genetic heterogeneity, differences in the composition of the gut microbiota and the utilization of different sources of fiber are among the possible causes underlying the inconclusive results obtained from human studies (5). To overcome these hurdles, Donohoe et al. utilized BALB/c mice with a strictly defined gut microbiota kept on gnotobiotic isolators, thus avoiding colonization by other commensal bacteria (4). Then, they colonize some of the animals with Butyrivibrio fibrosolvens, a butyrate-producing bacterium, and fed the mice with either low- or high-fiber diets that were otherwise identical in composition and calorically matched. This experimental system allowed the authors to rule out any effect of differences in genetics, intestinal microbiota and fiber source on CRC development. Using this gnotobiotic mouse model, they found that mice fed with high-fiber diet and colonized with B. fibrosolvens were protected against azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate (AOM/DSS)-induced CRC. Strikingly, these mice developed fewer, smaller and less aggressive tumors than all the other experimental groups. Importantly, high-fiber diet per se did not have any protective effect on this CRC model, indicating that, only in combination with the right microbiota, dietary fiber could be beneficial in protecting against CRC. Based on these results, the authors propose that human epidemiologic studies should be revisited to incorporate differences in participants’ gut microbiota to better address the role of dietary fiber on CRC.

Another important conclusion one can immediately draw from this result is that a metabolic product from fiber fermentation by B. fibrosolvens must be involved in the tumor suppressive effect of dietary fiber. In line with this, mice fed with high-fiber diet and colonized with B. fibrosolvens had increased luminal levels of butyrate, but not acetate and propionate, the other two major SCFAs. This result clearly points to butyrate as a key bacterial metabolite inhibiting CRC development. To confirm this hypothesis, the authors modulated luminal butyrate levels by two different means. First, they colonized mice with a mutant B. fibrosolvens strain (that produces 7-fold less butyrate when cultured) and fed them with low- or high-fiber diet as before. After AOM/DSS treatment, they found that mutant B. fibrosolvens conferred an attenuated protective effect to high-fiber diet in these mice. Alternatively, they provided control mice a tributyrin-fortified diet, which increases colonic butyrate levels independently of microbiota. Following AOM/DSS regimen, these mice were almost completely protected against CRC, indicating that exogenous butyrate could recapitulate the protective effect of high-fiber diet and B. fibrosolvens. Together, these two experiments clearly demonstrated that fiber fermentation by B. fibrosolvens protects from CRC by increasing luminal levels of bacterial butyrate.

The tumor protective effect of butyrate has been mainly attributed to its anti-inflammatory properties. Butyrate downregulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in colonic macrophages, and it has been shown to regulate colonic regulatory T cells in mice, which have a crucial role in controlling intestinal inflammation (3). However, the authors did not find any difference in the number of regulatory T cells and associated cytokines among all the experimental groups, ruling out reduced inflammation as a cause for the protective effect of butyrate. Based on their previous work, the authors hypothesized that the tumor suppressive role of butyrate in CRC could be related to the metabolic differences exhibited by normal and cancerous colonocytes. Butyrate represents the primary source of energy in normal colonic epithelial cells (6). However, CRC cells, like most cancer cells, display an increased glucose uptake and metabolism, a phenomenon termed "Warburg effect" for the German scientist who originally described it in the early 20th century. Such switch towards glycolytic metabolism is required to sustain their energetic and anaplerotic demands. As a consequence, butyrate is not catabolized in these cells to the same extent and, therefore, accumulates to such concentration that can act as an HDAC inhibitor (7). Indeed, the authors found increased levels of butyrate in the tumors of mice colonized with B. fibrosolvens and fed with high-fiber diet, suggesting that more butyrate molecules could be available to function as an HDAC inhibitor. Consistent with this, H3 acetylation levels are increased in the tumors of these mice, compared to adjacent normal colonocytes and tumors from control mice. Importantly, the authors found increased histone 3 acetylation at the promoter region of key pro-apoptotic and cell cycle genes, such as FAS, p21 and p27, leading to increased expression of these genes and the concomitant inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis of CRC cells. Finally, the authors extended these observations to human CRC samples, where they detected elevated levels of butyrate and H3 acetylation compared to matched normal mucosa.

Collectively, this body of work provides convincing evidence that dietary fiber, when combined with butyrate-producing bacteria, can protect from CRC by providing tumors with high levels of butyrate to act as an HDAC inhibitor, thus impairing tumor growth (Figure 1). However, it also raises several intriguing questions. Which other species of bacteria are important in CRC protection? Although this study has focused of B. fibrisolvens, a type of bacteria common in ruminant animals, a large number of genera, including SCFAs-producing species, have been identified in the human colon (8). In this context, different species could generate luminal butyrate at lower concentrations, inducing aberrant proliferation and transformation of colon epithelial cells, as recently reported in an APCMin/+MSH−/− model of CRC (9). In the same way, can other bacterial metabolites play a role in the tumor suppressive effect of dietary fiber? The modest decrease in tumor protection shown in mice colonized with mutant B. fibrisolvens suggests that, very likely, this could be the case. It would be fascinating to elucidate which are these metabolites and their effect on CRC prevention as well as in the metabolism of colon cancer cells. Finally, a better knowledge of how to modulate our intestinal flora by changing our diet would definitively help us to elucidate the complex interaction between diet, intestinal flora and CRC prevention.

Acknowledgements

Work in the Mostoslavsky lab is supported in part by NIH grants GM093072-01, DK088190-01A1, CA175727-01A1 and The Andrew L. Warshaw M.D. Institute for Pancreatic Cancer Research. C.S. is the recipient of a Visionary Postdoctoral Award from the Department of Defense. RM is the Kristine and Bob Higgins MGH Research Scholar and a Howard Goodman Awardee.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louis P, Hold GL, Flint HJ. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2014;12:661–72. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donohoe DR, Holley D, Collins LB, Montgomery SA, Whitmore AC, Hillhouse A, et al. A Gnotobiotic Mouse Model Demonstrates that Dietary Fiber Protects Against Colorectal Tumorigenesis in a Microbiota- and Butyrate-Dependent Manner. Cancer Discovery. 2014 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferguson LR, Harris PJ. The dietary fibre debate: more food for thought. Lancet. 2003;361:1487–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roediger WE. Role of anaerobic bacteria in the metabolic welfare of the colonic mucosa in man. Gut. 1980;21:793–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.9.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donohoe DR, Collins LB, Wali A, Bigler R, Sun W, Bultman SJ. The Warburg effect dictates the mechanism of butyrate-mediated histone acetylation and cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2012;48:612–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pryde SE, Duncan SH, Hold GL, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. The microbiology of butyrate formation in the human colon. FEMS microbiology letters. 2002;217:133–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belcheva A, Irrazabal T, Robertson SJ, Streutker C, Maughan H, Rubino S, et al. Gut microbial metabolism drives transformation of MSH2-deficient colon epithelial cells. Cell. 2014;158:288–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]