Abstract

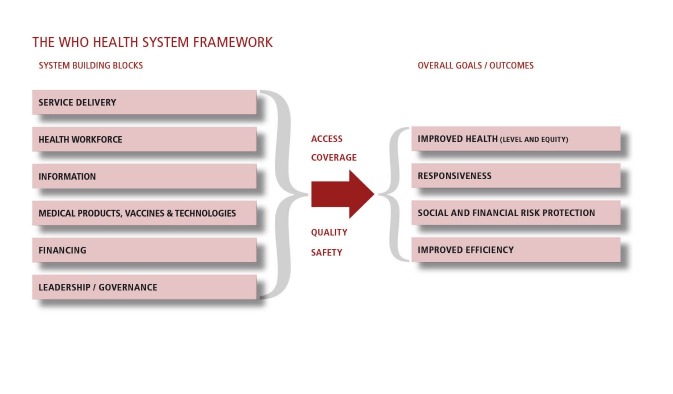

Background: Family Planning (FP) program in Pakistan has been struggling to achieve the desired indicators. Despite a well-timed initiation of the program in late 50s, fertility decline has been sparingly slow. As a result, rapid population growth is impeding economic development in the country. A high population growth rate, the current fertility rate, a stagnant contraceptive prevalence rate and high unmet need remain challenging targets for population policies and FP programs. To accelerate the pace of FP programs and targets concerned, it is imperative to develop and adopt a holistic approach and strategy for plugging the gaps in various components of the health system: service delivery, information systems, drugs-supplies, technology and logistics, Human Resources (HRs), financing, and governance. Hence, World Health Organization (WHO) health systems building blocks present a practical framework for overall health system strengthening.

Methods: This descriptive qualitative study, through 23 in-depth interviews, explored the factors related to the health system, and those responsible for a disappointing FP program in Pakistan. Provincial representatives from Population Welfare and Health departments, donor agencies and non-governmental organizations involved with FP programs were included in the study to document the perspective of all stakeholders. Content analysis was done manually to generate nodes, sub-nodes and themes.

Results: Performance of FP programs is not satisfactory as shown by the indicators, and these programs have not been able to deliver the desired outcomes. Interviewees agreed that inadequate prioritization given to the FP program by successive governments has led to this situation. There are issues with all health system areas, including governance, strategies, funding, financial management, service delivery systems, HRs, technology and logistic systems, and Management Information System (MIS); these have encumbered the pace of success of the program. All stakeholders need to join hands to complement efforts and to capitalize on each other’s strengths, plugging the gaps in all the components of FP programming.

Conclusion: All WHO health system building blocks are interrelated and need to be strengthened, if the demographic targets are to be achieved. With this approach, the health system shall be capable of delivering fair and responsive FP services.

Keywords: Systems Thinking, Stakeholder Analysis, Family Planning (FP), Developing Countries, Pakistan

Introduction

Family planning (FP) is a significant and effective approach to reach the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Despite the well-recognized benefits of FP, many governments in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) have made only limited investments in these programs because priority is given to other programs and donors’ varied interest (1). Moreover, political commitment, improvements in the logistic system, performance based financing, training of service providers, and coordination between donors and government agencies resulted in a remarkable decline in unmet need for FP in many countries (2). Most of the Islamic countries have reasonably good FP indicators. The well-organized FP programs of Iran and Egypt are worth mentioning, as well. Some of the success stories indicate that a conducive environment at the FP centers, reorientation of FP services, capacity building of service providers, free of cost contraceptives, and services, etc. can actually make the difference (3). Many countries in the region have realized the importance of FP and implementing the programs successfully through political support, providing effective services, information systems, commodity security, and adequate planning and policies (4,5).

Pakistan was one of the few Asian countries to start a FP program, but fertility decline is slower as compared to neighbouring countries (6). It ranks sixth among the populous countries in the world with a population of 184.8 million. Pakistan is one of the countries where population size is expected to double by 2050. Despite a long history of FP programs, the population growth rate is still high at 2.1% with a contraceptive prevalence rate of 35%, unmet need at 20% and the total fertility rate at 3.8 (7). This has resulted in high levels of unintended pregnancies leading to adverse health consequences such as maternal mortalities and morbidities (8) (Table 1).

Table 1 . FP indicators of Islamic and regional countries .

| Country | Total fertility rate | Contraceptive prevalence rate % | Population growth rate % |

| Saudi Arabia | 2.8 | 24.0 | 1.8 |

| Egypt | 2.9 | 60.0 | 2.0 |

| Turkey | 2.0 | 73.0 | 1.2 |

| Iran | 1.9 | 73.0 | 1.3 |

| Indonesia | 2.3 | 61.0 | 1.3 |

| Bangladesh | 2.3 | 61.0 | 1.6 |

| Afghanistan | 6.2 | 23.0 | 2.8 |

| Bhutan | 2.6 | 66.0 | 1.3 |

| India | 2.5 | 54.0 | 1.5 |

| Maldives | 2.3 | 35.0 | 1.9 |

| Nepal | 2.6 | 50.0 | 1.8 |

| Sri Lanka | 2.2 | 68.0 | 1.2 |

| Pakistan | 3.8* | 35.4* | 2.1 |

FP= Family Planning

Source: 2012 World Population Data Sheet, Population Reference Bureau, *PDHS 2012–3

Collaborative efforts among the Ministries of Health, Population Welfare, Planning and Finance in Pakistan have been lacking, and no joint policy instrument has been developed to address the issue of population growth in the resource constrained country. To achieve better service delivery, resource saving, coordinated information systems, optimal utilization of Human Resources (HRs), and joint supervision and monitoring, a clubbed budgetary allocation to health and population programs can actually be a very pragmatic approach (9). Unchecked population growth, and the narrow impact of population policies and population welfare programs, eventually led to the formulation of the National Population Policy (NPP) in 2010, which remains in limbo owing to political disinterest (10). After devolution in 2011, the Federal Ministry of Population Welfare and the Ministry of Health (MoH) were abolished, which greatly affected the program due to limited ownership by provinces. An effective FP policy and program may have played a vital role in achieving MDG target 5b (11); but implementation remains flawed. FP services have not kept pace with increased demand in Pakistan. Despite donor and NGO interventions to support the government’s program, there have been serious gaps in the supply chain, record keeping and service delivery. Population welfare departments have failed to take up a stewardship role to make the FP program dynamic and responsive to the needs of clients. Staff motivation and incentives have been at an all-time low, affecting the entire service delivery environment. No concrete steps have been taken to overcome the issue of low access and utilization, which were created by religious misinterpretations, and cultural and social barriers (12,13).

Significant weaknesses in all health system components, including governance, service delivery, information systems, supplies, HRs, and financing, resulted in a neglected state of affairs, bringing the country to a stage of population explosion. Weaknesses identified are slow progress, poor integration of the program with health services at the local level, including Management Information System (MIS), and de-motivational factors such as job insecurity and non-payment of salaries on time (14).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an effective and efficient health system is mandatory for achieving MDGs and sustainability thereafter (15). Today, the major challenge for the provincial governments is to integrate the population welfare and health departments to ensure an effective and sustainable service delivery system. Previous policies have created a population-health disconnect between the two departments (9). Provinces need to audit their abilities as well as weaknesses, in terms of governance, service delivery, health information, financial resources, commodities provisions, and HRs in order to improve their FP indicators (16). After the 2011 devolution, population and health are provincial subjects; and all the provincial governments have developed their own health sector strategies. Therefore, it is an opportune time to fill this breach in the health system of Pakistan and to move toward a definite and practical integration of health and FP programs.

The two objectives of this study were: i) to determine and document the health systems related factors that contributed to the failure of FP programs in Pakistan, and ii) to record the possible solutions emerging from the stakeholders’ perspective, for improving FP programming. To study the system level bottlenecks and constraints, it was ideal to employ the WHO’s health system six building blocks model (Figure 1) (17).

Figure 1 .

The building blocks of the health systems: Aims and Attributes. Reproduced with permission from WHO (17) (p. 3).

Methods

This was a descriptive qualitative study, conducted in Islamabad and all provincial capitals of Pakistan from July to September 2013. A total of 23 officials were interviewed from the Planning and Development Division, Population Welfare, and Health Departments from all parts of Pakistan including Baluchistan, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, Gilgit Baltistan, and Azad Jammu Kashmir. Moreover, representatives of donor agencies and the prominent national NGOs involved in FP programming were included in the study.

Purposive sampling of initial key informants led to more respondents identified through the snowball effect. Interviews were conducted until the saturation point was reached, after which no new information was recorded. The final sample consisted of 12 participants from the government, 6 from NGOs, and 5 from donor agencies.

An interview guide for the in-depth interviews, with open-ended questions, was prepared based on the WHO conceptual framework of health system building blocks, and literature available on FP programs. The interview guide was pre-tested for any changes, re-sequencing and merger of questions. Interviews were conducted after receiving written consent. Average duration of interviews was approximately 45 minutes. The principal investigator of this study conducted all of the interviews.

Verbatim notes were taken, and interviews were recorded where allowed by the respondents. Data collected was transcribed and analysis was done manually by thematic content analysis. Specific nodes were developed for the questions and probes of in-depth interviews. Significant findings and responses were aggregated as sub-nodes and later analyzed to develop themes. Information from literature and responses of representatives from government departments, donors, and NGOs were then triangulated to find consensus and conflicts on a variety of issues behind the failure of FP programs in Pakistan.

Ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) was sought before conducting the study. Written consent was also obtained from all respondents after explaining the purpose of the study. Confidentiality, anonymity and privacy of the data were assured.

Results

Each interview was started with conversation about the current results and outcomes of FP programs and concluded with recommendations to revamp the building blocks of the health system for improvement in the current state of affairs.

Performance of family planning programs

If the goals of Pakistan’s FP programs are healthy families who can space their children according to their choice and will, then the study findings suggest that the outcomes have not been satisfactory in terms of equity in access to services, in service responsiveness and system efficiencies, and in reducing social and financial risks. There have been issues from the beginning of the programs in terms of service delivery, outreach and coverage, HRs, budget, commodity procurement etc. FP programs have not been doing well because of the disconnect between health and population ministries. Hence, both ministries had been operating in isolation, not sharing information, resources, or even infrastructure.

“Pakistan is considered to be among few countries to start FP programs in South Asia. See where do we stand now? We are the worst performers in terms of CPR. FP was not the prime agenda. We did not keep pace with the global objectives and our modus operandi got out dated due to lack of support from the health department” (NGO representative).

Donors and government representatives’ views corroborate with those of NGO representatives.

Political and governance aspects

A majority of respondents admitted that there has been a lack of good governance regarding FP programs, resulting in issues of coordination, regulation, strategic planning, resource allocation, and management of health and population ministries. Effective leadership, political commitment and ownership were missing, too.

“After the devolution of 2011, the program has further suffered from lack of coherence and coordination. Unfortunately, provincial governments have shown a lack of commitment towards this program. Allocation of funds has been as meager, as has always been the case; the situation has become even worse” (Government official).

Donors and NGOs offered their full support in this period of transition to implement the new agenda of the provincial governments.

Financing mix

All the respondents agreed on the role of government in providing funds. Resource flow has been three dimensional. A major source of funding has been government whereas the donors and NGOs have been providing intermittent support. Even the combined pool of money did not suffice.

“So far the major operational cost is being provided by the Government. Capacity building of personnel and up gradation of service delivery outlets is the area of focus for donor agencies, along with the financing of advocacy and awareness programs. Social marketing is flourishing in the non-governmental sector in urban and semi urban areas” (Government official).

Nonetheless, a government spokesperson hinted at the NGOs and donors’ preferences to work in urban and peri-urban areas only; hence keeping the rural population (65%) deprived of easily accessible, safe, and quality FP services.

Financial management

The respondents from all quarters were unanimous on the point that there had been inadequate funding, inappropriate distribution, and, more so, inefficient utilization of funds.

“Resources have always been constrained in both the population and health sector. Provision of resources is not an issue; management of resources is even a more serious issue” (Government official).

Donors and NGOs were of a different opinion though. According to them, many NGOs are criticized for being non-transparent, but there is hardly any criticism over government corruption and financial mismanagement.

Service delivery system

All respondents were focused on the issue of accessibility, the compromised quality of services, gaps in capacity building, and the lack of technical guidance.

“There are two main issues in service delivery: coverage and quality. For FP coverage, one key constraint is that the health department is not providing FP; only the Population Welfare Department is delivering services, with limited coverage and quality. So accessibility becomes an issue. Staff are not competent enough to provide counseling as per protocol. Many times, the methods of choice are not available” (Donor representative).

Government representatives insist that given their circumstances and resources, they are doing the best they can with service delivery.

Human resources for family planning

A common observation of the respondents was that female staff are preferred to be deployed in FP centers, and therefore it restricts men from being deployed to work in the centers. Skills, retention, recruitment, task shifting, supervision and motivation of staff, and non-availability of a supportive environment are all attributable to failure of HR policies, seriously affecting the level of implementation.

“HR challenges include political pressures during recruitment of staff, the contractual nature of employment, and low salary packages, causing retention problems. Moreover, lack of capacity building in competency based technical skills and actual practice of these skills under standard protocols, workload, lack of provision of quality services, poor supervision and monitoring of staff are some grave concerns to be looked into” (Government official).

Donors and NGOs may contribute to the lack of capacity building of HRs; however, retention, deployment and motivation are government responsibilities.

Logistic and supply chain systems

There is admittance on part of the government that logistics and the supply chain are crucial to run any service delivery program. There have been issues in distribution and coverage. Frequent stock outs and interrupted supplies have resulted in the dropout of FP clients. The NGOs’ opinion is that monitoring and supervision for contraceptives and maintaining the records of contraceptives are unreliable.

“There are a lot of issues in Pakistan regarding requisition of contraceptives coming from different departments; but sometimes there is merely issue of cost of transportation, due to which supplies get to the facility with significant delay. Monitoring and supervision of the utilization of commodities has to be made robust. There is also gross inconsistency in reporting” (Donor representative).

Government recognizes the donor’s interest for investment in creating a supply chain management system so that the shortage of any contraceptive can be tracked at any point in the country. However, to make it fully functional, still remains a distant dream.

Management Information System (MIS)

Many respondents were of the view that the information system for FP is not standardized. The records are either incomplete or filled with wrong data. Information generated is not used for decision-making.

“The information system does not clearly show demand generation that could be used for decision-making. It is never followed and the record is not completed properly. All programs have their own reporting system, and there is no integration at any level” (Government official).

Integration of FP MIS with the national Health Management Information System/District Health Information System (HMIS/DHIS), which records data of health departments exclusively, must be enforced for evidence based decision-making at all levels.

“Although we have very strong reporting mechanisms and the chain is functional from health facility to district, and then provincial and lastly to federal level, this has not been integrated into one HMIS system yet” (Government official).

Donors and NGOs consider it completely within the government’s domain.

Political credibility and promises

When asked about the policies, declarations, commitments and pledges regarding FP programs not getting translated into action, most of the respondents commented that commitments are made in isolation without adequate stakeholder involvement.

“Commitments and pledges are made at the international level. These commitments have never been brought to the national or grass roots level. Dissemination of information is an issue” (NGO representative).

There is a disagreement within government circles who claim to pursue a wider consultative process whenever it comes to making new policies and programs.

Road map to strengthen health systems

To conclude the interview, suggestions from the respondents were sought, considering the health system related factors, about what areas need to be emphasized more especially in the post devolution scenario. They were all keen to see FP being considered as a national priority program.

“Strict enforcement of policies (or maybe laws) is a foremost requisite. The program will not work until the leadership accelerates it with political commitment” (Government official).

Health and population have been separate departments. Realizing the importance of integration, a participant proposed:

“Integration of the population and health departments is the solution. The health department should be taken on board because it has a huge number of outlets, HRs, and services available” (NGO representative).

Appreciating the significance of service delivery and HRs, a participant stated:

“Improve access and develop linkages with the private sector. Break this isolation through policies, through more effective involvement of health managers and vigorous monitoring. Improve the skill set of the service providers. Introduce them to new technologies to improve choice of method mix” (NGO representative).

We cannot run a program without enough finances. All respondents suggested improving financial flow and supplies and that doing so may improve the outcomes of the program.

“We can reach anywhere if we have adequate financing. Ensuring the availability of contraceptives at doorsteps in rural areas is a big challenge. Involve the private sector to ensure the supplies” (Government official).

Donors agree that following the WHO health system building blocks model is a logical way to decide upon where to plug the gaps first, to allow the FP program to achieve the envisaged outcomes.

Discussion

Ensuring equitable access to quality FP programs and consequently control over the population growth rate is still to be contemplated in Pakistan. The country is lagging far behind in effective implementation of FP programs, with a host of factors to address and a number of flaws to correct. Cultivating bureaucratic priority and diffusing resistance in various quarters for FP to be integrated in health programs at large, is still achievable (18). The first and foremost step seems to be the integration of the health and population welfare departments. Literature also suggests that inadequate intersectoral coordination, and a lack of functional integration with main stakeholders has resulted in limited outreach and a lack of innovation. Integrating FP and health at the primary healthcare level would be an economical and effective way to improve FP indicators (10,13,16). Involving all stakeholders in wider consultations would be a wise approach to have maximum buy-in from all quarters (2,3). The responsibility of permanent financing ought to be taken up by the government (18). Flow of finances from the donors has always been intermittent, thus resulting in mixed results and creating urban rural disparities. Furthermore, there are serious issues of financial management; and financial flow from the main source, the Ministry of Finance, to executing agencies to implementing departments and finally to field organs has been extremely slow, impinging on timely program implementation (20). As summarized in Table 2, provinces must strategize how to optimally use the allocated funds for maximum outputs. Quality comes with capacity and competency to deliver. There is need to strengthen the existing service delivery structure by introducing performance based budgeting (21). Studies suggest that it is imperative to expand the access to quality services, reaching out to the remote areas with far greater need (2). Lack of contraceptive commodities at service delivery points and frequent stock outs hinder program effectiveness and quality of care resulting in loss of trust among the clients on the overall health system (22). The most worrisome result is the number of unwanted pregnancies and many of these leading to unsafe abortions (13,23,24). The supply system, therefore, needs to be reorganized as an utmost priority. Dearth of skilled HRs for FP along with gender imbalance and issues of their distribution in urban and rural areas are another dilemma of developing countries that needs the attention of the policy-makers (25). A comprehensive HRs policy is required to address the shortage, to develop a system for retention and capacity building of staff and to improve managerial and planning skills at provincial, as well as district, levels (13,26). There is a need for a paradigm shift which considers FP as a resolute path to improved maternal and child health (27). All stakeholders together have to work in close coordination, take ownership of the program, and launch joint efforts, building on each other’s potential and abilities (28).

Table 2 . Strategic plan for strengthening FP programs based on stakeholders’ analyses .

| Building blocks | Strategic actions |

| Governance and accountability |

•Improved stewardship by integrating Departments of Health and population welfare at the provincial level • Introduce community governance for revitalizing the PHC system, inclusive of FP |

| Service delivery |

• Institutionalize FP as part of essential health services package for all levels of care • Introduce client oriented FP services with choice and full range of contraceptives • Encourage private sector to ensure coverage where government does not have the foot print |

| Human resource |

• Establish a HR planning and development unit in every province • Build capacity of personnel on modern lines to offer quality and responsive FP services. |

| Information systems |

• Standardized LMIS for public and private sector health facilities • Develop capacity of health professionals on use of LMIS for effective and timely management of contraceptive supplies |

| Supplies, logistics and technologies |

• Enhance existing logistics and supply chain management system by strengthening procurement, quantification and distribution, with the use of LMIS • Regular reviews of availability of contraceptives to avoid out of stock periods at the facility level |

| Financing |

• Increase in government allocation and development expenditure to the FP program • Improve capacity of the provincial for timely release of funds, and district governments for increasing effective budget utilization |

FP= Family Planning; PHC= Primary Healthcare; HR= Human Resource; LMIS= Logistic Management Information System

Conclusion

This study concludes that the low performance or failure of FP programs is the result of a multitude of inter-related structural and systems performance factors. This study provides clear evidence to consider gaps in all the health system building blocks, and suggests that the breaches need to be addressed cautiously to improve the current state of FP programs in Pakistan. Government, NGOs and donors will have to use a system lens to analyze the performance of the FP programs in the future. In post-devolution times, concrete steps have to be taken to fix and connect all the blocks because these influence each other to shape the system. The strong relationship among all building blocks of the health system suggests that only systems thinking can improve FP programs. This approach has the potential to curtail the unbridled population growth in Pakistan.

Ethical issues

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of Health Services Academy, Islamabad.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SZ and BTS designed the research; SZ conducted the literature searches; SZ and BTS designed the data collection tool; SZ collected the data and analyzed; BTS supervised the write up of first and successive manuscript drafts, and both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Key messages

Implications for policy makers

While revisiting Family Planning (FP) programs in Pakistan in post-devolution times, it is imperative to invest in all the health systems building blocks to ensure a responsive service delivery. Followings are the most important steps that are required at the policy level:

Political ownership of FP to be taken as a national cause;

Integrating FP into larger health policy, programs and service delivery;

Increasing budgetary allocation for FP programs, and the health sector in general;

Incentivizing Human Resources (HRs) by building their capacity, increasing their remunerations, and providing a career structure;

Chalking out a mechanism that ensures the timely delivery of contraceptives at the last mile.

Implications for public

Only a responsive Family Planning (FP) program can ensure access, quality, equity, and safety for those seeking these services.

Citation: Zafar S, Shaikh BT. ‘Only systems thinking can improve family planning program in Pakistan’: A descriptive qualitative study. Int J Health Policy Manag 2014; 3: 393–398. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.119

References

- 1.Bongaarts J. Can Family planning programs reduce high desired family size in Sub Saharan Africa? Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;37:209–16. doi: 10.1363/3720911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne A, Morgan A, Soto J, Dettrick Z. Context-specific, evidence-based planning for scale-up of family planning services to increase progress to MDG 5: health systems research. Reprod Health. 2012;9:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaikh BT, Azmat SK, Mazhar A. Family planning and contraception in Islamic countries: A critical review of the literature. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streatfield P, Kamal N. Population and Family Planning in Bangladesh. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simber M. Achievements of Iranian family planning programmes 1956-2006. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18:279–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Contraceptive Performance Report 2011-2012. Islamabad; 2012.

- 7. National Institute of Population Studies & ICF International. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012-13. Islamabad; 2013.

- 8. Gazdar H, Khan A, Qureshi S. Measuring the economic costs of unsafe abortion mortality and morbidity in Pakistan: Preliminary findings and survey design. Karachi: Collective for Social Science Research; 2010.

- 9.Nishtar S, Amjad S, Sheikh S, Ahmad M. Synergizing health and population in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:S3–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaikh BT. Unmet need for family planning in Pakistan- PDHS 2006-2007: It’s time to re-examine déjà vu. Open Access Journal of Contraception. 2010;1:113–8. doi: 10.2147/OAJC.S13715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed S, Li Q, Liu L, Tsui AO. Maternal deaths averted by contraceptive use: an analysis of 172 countries. Lancet. 2012;380:111–25. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60478-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sami N, Shaikh BT. Leadership in family planning & reproductive health: a university based capacity building and networking initiative in Pakistan. Pak J Public Health. 2012;2:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13. United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Deliver Project Task Order 4. Pakistan: Provincial and district supply chain management situation assessment. Arlington: USAID; 2012.

- 14.Wazir S, Shaikh BT, Ahmed A. National program for family planning and primary health care Pakistan: A SWOT analysis. Reprod Health. 2013;10:60. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Backman G, Hunt P, Khosla R, Jaramillo-Stouss C, Fikre BM, Rumble C. et al. Health Systems and the right to health: an assessment of 194 countries. Lancet. 2008;372:2047–85. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61781-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shaikh BT. Devolution in health sector: challenges and opportunities for evidence based policies. LEAD Pakistan Occasional Paper Series. Islamabad; 2013.

- 17. World Health Organization (WHO). Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes. Geneva: WHO; 2007.

- 18.Shiffman J. Political management in the Indonesian family planning program. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30:27–33. doi: 10.1363/3002704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khanna A, Pradhan J, Rashid HA, Beekink E, Gupta M, Sharma A. Financing reproductive health in Bangladesh. J Health Manage. 2013;15:177–202. doi: 10.1177/0972063413489004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). The state of family planning in Pakistan. Targeting the missing links to achieve development goals. Islamabad: UNFPA; 2013.

- 21. United States Agency for International Development (USAID). IFPS Technical Assistance Project (ITAP). 20 Years of the Innovations in Family Planning Services Project in Uttar Pradesh, India; Experiences, Lessons Learned and Achievements. Gurgaon, Haryana: USAID; 2012.

- 22.Hardee K, Leahy E. Population, fertility and family planning in Pakistan: a program in stagnation. Pop Action Int. 2008;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 23. United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Deliver Project Task Order 1 and Pathfinder International. Contraceptive Security Brief: Engaging Service Delivery Providers in Contraceptive Security. Arlington: USAID; 2010.

- 24.Barros AJ, Ronsmans C, Axelson H, Loaiza E, Bertoldi AD, França GV. et al. Equity in maternal, newborn and child health interventions in Countdown to 2015: a retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. Lancet. 2012;379:1225–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Senanayake H, Goonewardene M, Ranatunga A, Hattotuwa R, Amarasekera S, Amarasinghe I. Achieving Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 in Sri Lanka. BJOG. 2011;118:78–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishtar S, Boerma T, Amjad S, Alam AY, Khalid F, Haq I. et al. Pakistan’s health system: performance and prospects after the 18th Constitutional Amendment. Lancet. 2013;381:2193–206. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhutta ZA, Chopra M, Axelson H, Berman P, Boerma T, Bryce J. et al. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000-10): taking stock of maternal, new born, and child survival. Lancet. 2010;375:2032–44. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chikvaidze P, Madi HH, Mahaini RK. Mapping family planning policy and programme best practices in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region: a step towards coordinated scale-up. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18:911–9. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.9.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]