Abstract

Despite widespread endorsement within the field of international family planning regarding the importance of quality of care as a reproductive right, the field has yet to develop validated data collection instruments to accurately assess quality in terms of its public health importance. This study, conducted among 19 higher volume public and private facilities in Kisumu, Kenya, used the simulated client method to test the validity of three standard data collection instruments included in large-scale facility surveys: provider interviews, client interviews, and observation of client-provider interactions. Results found low specificity and positive predictive values in each of the three instruments for a number of quality indicators, suggesting that quality of care may be overestimated by traditional methods. Revised approaches to measuring family planning service quality may be needed to ensure accurate assessment of programs and to better inform quality improvement interventions.

Since the introduction of family planning programs in developing countries in the 1950s, significant reductions in fertility have been observed (Bongaarts, 2011, Cleland et al., 2006). Declines in fertility are most evident in Latin America and Asia where total fertility rates (TFR) in the past 60 years have dropped from nearly 6 births per woman to less than 2.5 (Bongaarts, 2011). In contrast, the majority of countries in sub-Saharan Africa continue to experience high rates of fertility, with a regional TFR of 5.2 births per woman – more than twice the global average (Bongaarts, 2011, Population Reference Bureau, 2011). Global disparities in the prevalence of contraceptive use, apparent since the late 1980s despite substantial improvement in access, prompted many members of the international family planning community to question whether continued improvements in geographic and financial access to services in sub-Saharan Africa would be sufficient to realize further reductions in fertility (Barry, 1996, Bertrand et al., 1995, Bruce, 1994).

Research findings from the late 1980s suggested that the influence of geographic access on contraceptive use was less critical than women’s fear of contraceptive side effects, lack of knowledge, or her community’s disapproval of contraceptive use (Bongaarts and Bruce, 1995, Casterline et al., 1997, Cotten et al., 1992). These findings caused some to conclude that, despite the ability of many family planning programs to reach remote areas of poor countries, the programs were “social failures” for their inability to address cultural factors, health concerns, and misinformation in the populations they served (Bongaarts and Bruce, 1995). In response, many international donors and national policy-makers in the early 1990s began to focus on characteristics of family planning service delivery, with a growing interest in a previously neglected dimension of family planning programs - quality of care (Barry, 1996, Berer, 1993, Brown et al., 1995, Hardee and Gould, 1993, Kols and Sherman, 1998, Jain et al., 1992a, Simmons and Elias, 1994).

The overwhelming and broad support for promotion of service quality in family planning programs was influenced by the establishment, in 1990, of a formal framework which outlined the essential elements of quality of care in family planning service delivery (Bruce, 1990, Hull, 1996). This framework, developed by Judith Bruce, includes aspects of both technical competency and interpersonal relations, reflecting and reinforcing the shift in focus from demographic targets to a client-centered and reproductive rights approach (Hull, 1996). Bruce states that the six elements included in her framework for quality of care in family planning programs “reflect six aspects of services that clients experience as critical”; these include choice of methods, information given to clients, provider competence, interpersonal relations, follow-up mechanisms, and appropriate constellation of services (Bruce, 1990). More recent literature on quality improvement in developing country health systems continues to draw from the Bruce framework, placing an emphasis on delivering services that are acceptable, patient-centered, and offered by competent and skilled providers (World Health Organization, 2006, World Health Organization, 2014).

Since its introduction in 1990, Bruce’s framework for quality of care in family planning service delivery has become a recognized and widely used standard for conceptualizing service quality in the field of international family planning (Askew et al., 1994, Barry, 1996, Brown et al., 1995, Hull, 1996, Jain et al., 1992a, Jain et al., 1992b, Ketting, 1994). However, global adoption of this framework was only a first step; the measurement of the components of the framework posed a whole new set of challenges. The need for systematic, reliable, and relatively fast measures of quality gave rise to the development of a set of instruments known as the Situation Analysis (Simmons and Elias, 1994). As the first attempt to operationalize the concept of quality (Miller et al., 1991), the objectives of the situation analysis were to describe both the quality and infrastructure of family planning services and to evaluate the impact of quality on the outcomes of client satisfaction, realization of reproductive goals, contraceptive prevalence, and fertility (Fisher et al., 1992).

Numerous situation analyses have been conducted in multiple developing countries over the past twenty years, with refinements to the original instruments (Paine et al., 2000). The situation analysis originally included four basic data collection instruments for use at a service delivery point, although a research team may omit one or more of these instruments depending on available resources: a facility audit, an observation guide for use by a third party observer, a questionnaire for interviewing exiting family planning clients, and a questionnaire for interviewing family planning service providers (Fisher et al., 1992, MEASURE DHS, 2012). Large-scale surveys collecting data on population and health indicators, such as the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), often incorporate situation analysis instruments to measure facility-level service quality. DHS’s health facility survey is called the Service Provision Assessment (SPA) and implements situation analysis instruments in more than a dozen developing countries (The DHS Program, 2014).

These different approaches to collecting quality-related data at the facility level each have distinct advantages. For example, the facility audit can capture method availability by noting the current supply and the frequency of stockouts. Audits are also uniquely designed to assess the adequacy of facility infrastructure. Provider interview data can be valuable for identifying low provider knowledge of correct counseling procedures. For example, in some settings providers may not be aware of the necessity or value of discussing warning signs or inquiring into the clients’ reproductive goals. Low prevalence of an indicator from this self-reported data can therefore highlight deficiencies in provider knowledge. Client interview data is uniquely able to measure more subjective constructs like respectful treatment, client satisfaction, and perceptions of quality. Lastly, observational data can be useful for elements of quality where the client is not qualified to make an assessment – such as technical competence – or has limited recall.

However, with the exception of the facility audit, which requires the data collector to physically verify much of the information documented, there are methodological limitations of the situation analysis including courtesy bias, reliability of reporting, the Hawthorne effect, and recall bias. Courtesy bias results when clients feel uncomfortable reporting negative aspects of care. Additionally, provider interviews may lack reliability due to a desire on the part of providers to report their intentions or an “ideal” of service delivery rather than what they do in practice (Simmons and Elias, 1994). The Hawthorne effect results during third party observations for which providers display their “best behavior” (MEASURE Evaluation, 2001, Bessinger and Bertrand, 2001). For example, during a situation analysis conducted in Kenya in 1991, a provider reported, “I usually do not have this much time for clients, but in view of your presence, I had better try to do an especially good job” (Miller et al., 1991). Lastly, when interviewing family planning clients just before they exit the health facility, clients may have difficulty recalling the information that they received during their family planning counseling session, resulting in recall bias. Most of these forms of information bias tend to skew the resulting measures of quality in a positive direction of higher perceived quality (MEASURE Evaluation, 2001, Simmons and Elias, 1994, Bessinger and Bertrand, 2001, Whittaker et al., 1996).

In some cases, these biases may not interfere with study objectives; for example some prior studies contained objectives best achieved by investigating client or provider perceptions of quality without a focus on whether perceived quality differs from actual provider behavior (Agha et al., 2004, Al-Qutob and Nasir, 2008, Bender et al., 2008, Koenig et al., 1997, Mohammad-Alizadeh et al., 2009, Mroz et al., 1999, Nakhaee and Mirahmadizadeh, 2005, Speizer and Bollen, 2000, Tu et al., 2004, Whittaker et al., 1996). However, a large degree of the quality of care research in the field of international family planning contains objectives requiring measures of actual provider behavior. In these cases, biased information may result in false study implications and conclusions. For example, many of the methodologically rigorous investigations of the relationship between quality of care and family planning use have found only a weak association between quality and use (Ali, 2001, Barden-O’Fallon et al., 2011, Gubhaju, 2009, Hong et al., 2006, Khan, 2001, Magnani et al., 1999, Mensch et al., 1996, Mensch et al., 1997). Whether these findings are due to a meager relationship between family planning service quality and contraceptive use or due to significant problems in the way quality is measured remains unknown (Mensch et al., 1994).

The Simulated Client Method

One approach for collecting data on service quality while avoiding many of the biases inherent with tools from the situation analysis is use of the simulated client method (Hardee et al., 2001, Huntington and Schuler, 1993, Leon et al., 2007, Madden et al., 1997, Maynard-Tucker, 1994, Naik et al., 2010, Population Council, 1992, Schuler et al., 1985). In this approach, a woman pretending to be an actual new family planning client presents at a health facility and undergoes a family planning counseling session. During the session the provider is unaware that the client has a research agenda (Madden et al., 1997). Following the session, the under-cover data collector records or reports her observations. The main benefits of this method of conducting observations are that it is an unobtrusive means of collecting data and it is likely to be more accurate than a third party observation; it collects data on actual practice that would be difficult to obtain through other means (Madden et al., 1997). Data from simulated clients are able to measure quality of care, in terms of actual practice, unfettered by the biased perspectives of providers and clients and in this way are expected to provide a more accurate account of objectively measurable aspects of provider behavior.

The key to accuracy with the simulated client method is the employment of simulated clients who present realistically to the providers and have a strong recall of events occurring during their counseling session (Madden et al., 1997). It can be difficult to recruit such clients, especially in small communities where the simulated clients are more likely to be recognized (Boyce and Neale, 2006). A 1991 study of the reliability of data obtained from simulated clients in Peru used pairs of concealed observers and found low levels of agreement (interclass correlation = .5) within pairs indicating the likelihood of rating errors (Leon et al., 1994). One strategy for increasing reliability of simulated client data is the use of a checklist to help the simulated client recall and objectively evaluate providers on listed items.

Although there are many methodological benefits of using simulated clients to collect data on provider-client interactions, there are also ethical concerns with this type of data collection (Madden et al., 1997). Because it is inherently necessary for simulated clients to engage in subterfuge by masking their true purpose and intent, obtaining informed consent from providers is not possible (Huntington and Schuler, 1993). One possible negative consequence of this approach is that once providers become aware that they have been observed without their consent, this realization could undermine the relationship and rapport between providers and their supervisors who have approved such methods. In addition, it is possible that clients may have to undergo an unwanted physical exam in order to maintain the ruse of their visit (RamaRao and Mohanam, 2003, Madden et al., 1997). The ethical concerns related to use of the simulated client method may be responsible for the limited use of this method in the family planning literature.

Guidelines for addressing ethical concerns in epidemiologic research published by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) suggest absence of informed consent may be acceptable in scenarios where full disclosure would interfere with the study purpose (Madden et al., 1997). Huntington and Schuler also suggest ways to uphold ethical integrity while still gaining the benefits of this approach. One solution is to disclose to the provider the possibility of simulated client visits at a future date so that they are aware that they will be observed at some point but will not know when such observations will occur, inhibiting their motivation to change their behavior (Huntington and Schuler, 1993). It may also be possible to train simulated clients on ways to avoid unwanted exams (RamaRao and Mohanam, 2003). Many feel the benefits of employing simulated clients outweigh the ethical concerns (Boyce and Neale, 2006).

Objectives

The objective of this study was to use the simulated client method to assess the validity of three standard instruments frequently used to measure family planning service quality., i.e. to quantify the sensitivity and specificity of provider and client interviews and third-party observations in capturing actual provider behavior as measured by the simulated client method. We hypothesize that current measures of service quality within these instruments are subject to the biases described above and may skew results of quality of care studies in the direction of higher perceived quality. Due to the types of information bias described above, we hypothesize current measures of quality will have low validity, in particular low specificity, when compared to simulated client data, across most aspects of quality measured in all three of the standard instruments tested. This study’s focus on the validity of selected quality of care indicators within these instruments is motivated by the theory that the quality of family planning services directly impacts both uptake and continued use of contraception (Jain, 1989). Quality-related data from these three instruments is often used to identify modifiable deficiencies in quality, estimate the association between various aspects of quality and contraceptive use, or evaluate the effectiveness of quality improvement interventions. Such studies assume standard instruments provide accurate measurement of quality, yet the validity of these tools has not been established1. Therefore, testing the validity of current measures of quality of care in family planning will provide valuable information for these types of studies. For the purposes of this study we focus specifically on service quality as defined by actual provider behavior. Depending on results, future investigations of quality may wish to substitute or supplement exit or provider interviews or third party observations with simulated client observations.

Methodology

Study population

A total of 19 public and private health care facilities were purposively selected for this study, based on their location within the East District of Kisumu in Western Kenya. Included facilities had a minimum patient volume of 10 family planning clients per week, according to the prior week’s record in each facility’s official patient registration log. Within these 19 facilities, an estimated 108 providers offer family planning services and were on-duty during the study period.

Data collection instruments

Data obtained by simulated clients served as the reference standard to assess the accuracy of facility-level instruments designed to measure family planning service quality. Shortly after their visit to a participating facility, simulated clients recorded their observations in an objective and user-friendly checklist. The checklist, informed in part by MEASURE Evaluation’s Quick Investigation of Quality (QIQ) (MEASURE Evaluation, 2001), was designed to capture quantitative data on the six aspects of family planning service delivery quality, according to the Bruce framework (Bruce, 1990). The simulated client checklist contained 25 quality-related questions, each with an exhaustive list of possible responses coupled with user-friendly checkboxes.

Simulated client data were compared to data on provider behavior collected by three other facility-level instruments: an observation guide and questionnaires for interviewing family planning clients and service providers. The observation guide mirrored the simulated client checklist, collecting data on the six aspects of quality included in the Bruce framework. During provider interviews, family planning providers were asked about the quality of the services they provided as well as previous training, use of standard protocols, and consent requirements for delivery of family planning services. Client exit interviews collected data on the quality of services received as well as current and previous method use, wait time, client satisfaction, and perceived treatment.

The questionnaires for interviewing family planning clients and service providers were developed by The Measurement, Learning & Evaluation (MLE) Project. The MLE Project is the evaluation component of the Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (URHI), a multi-country program in India, Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal that aims to improve the health of the urban poor. The MLE project developed client and provider questionnaires for use in facility-level data collection activities conducted in Kenya in 2011 and these tools were adapted for use in this validation study. The last data source used in this study, the observation guide, was also modeled after the Bruce framework with input from the QIQ (MEASURE Evaluation, 2001) and the Population Council’s “Guidelines and instruments for a family planning situation analysis study” (Fisher et al., 1992). Table 1 contains the specific quality-related questions included in each of the four instruments included in this assessment.

Table 1.

Quality of Care Indicators

| Element of Quality | Simulated client checklist (reference standard) & third party observation guide indicators | Provider interview indicators | Exit interview indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Choice of Methods | * Which methods did the provider mention to the client? | * Do you provide information about different methods? | * Did your provider provide information about different FP methods? |

| * Did the provider ask about/discuss the client’s preferred method or method of choice? | * Do you discuss the client’s FP preferences? | * Did your provider ask about your method of choice? | |

| Information Given to User | * Did the provider help the client select an appropriate method? | * Do you help a client select a suitable method? | * Did your provider help you select a method? |

| * Did the provider tell the client what side effects to expect with her chosen method? | * Do you explain the side effects? | * Did your provider talk about possible side effects? | |

| * Did the provider tell the client how to manage the side effects? | |||

| * Did the provider discuss warning signs? | * Do you explain specific medical reasons to return? | ||

| * Did the provider tell the client how to use her selected method? | * Do you explain the way to use the selected method? | * Did your provider explain how to use the method? | |

| Provider Competence | * Was the client’s medical history taken? | ||

| Client-Provider Relations | * Did the provider give the client a respectful and/or friendly greeting? | * Do you identify reproductive goals of the client? | * During your visit, how were you treated by the provider? |

| * Did the provider enquire about the client’s reproductive goals and plans? | * Did your provider ask your reproductive goal? | ||

| * Did the provider ask the client if she had any questions? | * Did the provider ask you if you had any questions? | ||

| Continuity Mechanism | * Did the provider inform the client when to return for a follow-up visit? | Do you explain when to return for follow-up? | * Did your provider tell you when to return for follow-up? |

| * If yes, was the client given a reminder card or other memory prop? | |||

| * Was the client told what to do if she experienced problems before the next visit? | * Did your provider tell you what to do if you have any problems? | ||

| * Did the provider inform pill and injectable acceptors where to go for resupplies? | |||

| Appropriate Constellation of Services | * In addition to the family planning services you received, did the client receive any other health services from the service provider today? | * In addition to the family planning services you received, did you receive any other health services from the service provider today? |

Data Collection

Data collection occurred between August and October of 2012. Prior to data collection, research staff visited facility supervisors to explain the study design and purpose and to obtain permission for our study team of trained data collectors to undertake provider and client interviews and third party observations. Facility supervisors also consented to unscheduled visits to their facility by simulated or “mystery” clients.

For the simulated client component of this study, six local women, both married (n=4) and unmarried (n=2), ranging in age from 23 to 30 and with parity between zero and three children, were hired and trained on the checklist instrument. Simulated clients were selected to represent the women who come for family planning services in the participating facilities based on data collected at these facilities in 2011. Simulated clients used their true profiles when presenting at participating facilities and were trained to present as new contraceptive users. Each simulated client was assigned a “preferred method” of contraception, in order to observe provider behavior over a range of methods. Assigned methods included oral contraceptive pills, injectables, intrauterine devices, and contraceptive implants. In order to ensure the simulated clients avoided unwanted procedures, those clients assigned to prefer injectables, the IUD, or the implant were trained to conclude their counseling session before a method could be administered; clients assigned to prefer pills accepted 1–3 packs of pills when offered. Each simulated client visited one to two participating health facilities each day and reviewed completed checklists with the study principal investigator (PI) at the end of each day of data collection. Each simulated client filled out a complete checklist no more than two hours after concluding her facility visit. During the time of review between the simulated client and the PI, each recorded response was verbally confirmed.

In addition to visits from simulated clients, all 19 selected facilities participated in third party observations and interviews with exiting family planning clients and service providers. Trained research staff conducted interviews with all on-duty family planning service providers at each of the 19 participating facilities, with the exception of two providers who declined participation. Exit interviews were conducted with a convenience sample of new family planning clients at the facility on the day of data collection. Research staff attempted to interview a minimum of two new family planning clients at each facility and this was possible in all but four facilities, where client flow was lower than expected, given information from the previous week’s patient registration log. Third party observations were conducted on each provider offering services to a new family planning client on days when the research staff was present at the facility. All family planning providers and clients selected for interview or third party observation were asked to participate through an informed consent process. In addition to the one provider who refused an interview, three exiting clients declined participation in an interview. No clients or providers declined participation in a third party observation.

Confidentiality was a key component of the ethics training received by all data collectors during training and each data collector was required to sign a pledge of confidentiality upon completion of the training. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-Chapel Hill) and the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) reviewed and approved the study protocol and informed consent process for this study.

Analyses

Data from all four instruments (simulated client checklist, third party observation guide, questionnaire for interviewing exiting clients, and questionnaire for interviewing providers) were linked by individual provider, using a unique identifier. If a provider received more than one visit by a simulated or new client or if a provider was observed more than once, we chose one observation for the provider at random for this analysis. To determine the degree to which provider behavior was consistent between the simulated client checklist and each standard instrument, we first calculated the percent agreement for each indicator of quality. The percent agreement was calculated as the number of observations with identical responses divided by the total number of observations.

In addition to a measure of agreement between instruments, we also assessed the accuracy of the standard situation analysis measures by computing specificity, positive predictive values, and positive likelihood ratios relative to the simulated client method (treated as the reference standard). These test characteristics were not calculated if the denominator for a given statistic was ≤5. Exact methods were used to calculate confidence intervals for these statistics. Sensitivity, negative predictive values, and negative likelihood ratios were also calculated, but for simplicity of presentation, these results are included only in the appendix and are not discussed in the results section.

The specificity of indicators included in this analysis provides information about the ability of the indicator to accurately identify a true negative outcome (Fletcher and Fletcher, 2012). For example, in this analysis if we are considering the indicator for discussion of side effects in the provider questionnaire, the specificity of this indicator tells us, out of all those providers who do not have such discussions with a simulated client, the proportion who do not report discussing side effects on provider interviews. We hypothesize that those providers who do not practice this behavior – or others of known benefit - will be inclined to report that they actually do so in an effort to demonstrate compliance with good practices and avoid jeopardizing job security. In other words, those providers not engaging in high quality practices will be unlikely to report this to an interviewer and may alter their typical behavior when under observation or when serving clients likely to be interviewed. We therefore theorize that specificity will be low across all indicators and instruments.

In addition to specificity, we also calculated predictive statistics, in the form of positive predictive values and likelihood ratios, in order to understand the ability of standard instruments to accurately forecast provider behavior with simulated clients. The positive predictive value (PPV) of an indicator tells us, out of all providers who report or are observed doing a particular behavior, the proportion who actually engage in the behavior with simulated clients (Fletcher and Fletcher, 2012). For example, if we ask providers whether or not they discuss side effects with a client, the PPV tells us – out of all the providers who respond affirmatively – the percent who actually engage in such discussions when visited by a simulated client. We hypothesize that PPV will vary across indicators and instruments, but may be low for those quality-related behaviors that providers believe they should practice but do not, perhaps due to a lack of resources or time or due to inadequate motivation.

Predictive values depend on the prevalence of the behavior and therefore will be different in different populations. As such, it becomes difficult to generalize such predictive statistics to populations with a different prevalence regarding the indicators associated with the different aspects of family planning service quality. A solution to this limitation is to calculate likelihood ratios, which do not depend on prevalence (Fletcher and Fletcher, 2012). The positive likelihood ratio (LR+), calculated as sensitivity divided by one minus specificity, typically ranges from one to infinity with values close to one suggesting poor predictive ability (i.e., a positive response on the questionnaire does not predict that this behavior will take place with the simulated client) (Fletcher and Fletcher, 2012). When the LR+ falls below one, this is an indication that responses or observations predict behavior that is the opposite of that response. Such a result would suggest the indicator is an especially poor predictor of actual provider behavior. Given the potential for information bias discussed in the introduction, we hypothesize values for positive LRs will be close to the null value of one, indicating poor prediction, across most indicators in each standard instrument.

Recruitment

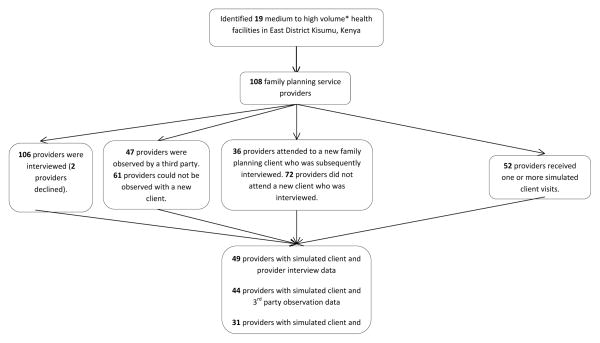

As mentioned previously, this study was conducted at 19 health facilities in East District Kisumu, within which there were an estimated 108 family planning service providers on-duty during the entire study period (Figure 1). The goal was to interview and observe all 108 providers within the participating facilities. Due to facility rotation schedules, many of these providers were delivering services other than family planning (such as child health services) on days when data were collected. As a result, not all 108 on-duty providers at the participating facilities received a visit by a simulated client. Similarly, not all of the 108 providers could be observed by a third party while providing family planning and many did not offer services to a new family planning client during the study period, inhibiting the ability of research staff to obtain client exit interviews with new clients served by each provider. Regarding provider interviews, one provider could not take the time away from workplace responsibilities to be interviewed and one additional provider declined participation in the study.

Figure 1. Recruitment of participating family planning service providers in 19 health facilities in Kisumu, Kenya 2012.

* Medium to high volume facilities are defined as those serving a minimum of 10 family planning clients in the week preceding the start of this study.

Trained research staff completed interviews with 106 providers, third party observations on 47 different providers (53 observations total, with some providers observed more than once), and exit interviews with new family planning clients attended by 36 different providers (57 exit interviews total). Trained simulated clients completed simulated client visits with a total of 52 providers (134 simulated client visits total). Forty-nine providers both received a simulated client visit and completed an interview with research staff (three providers were visited by a simulated client early in the study period and were on leave by the time research staff visited their facility, which prevented their participation in a provider interview). Forty-four providers both received a simulated client visit and were observed by a third party while providing family planning services to a new family planning client. Thirty-one providers both received a simulated client visit and provided services to a new family planning client who subsequently completed an interview with trained research staff.

Sample Characteristics

All of the 19 participating facilities were of medium to high volume and provided child health and HIV services in addition to family planning; 74 percent were public facilities. All 19 facilities were open from 8am to 5pm, and most were open Monday through Friday and closed on weekends. Exiting clients that were new family planning clients were, on average, 25 years of age with two children; 68 percent were married (data not shown). The 49 providers with both simulated client and provider interview data were primarily female (88 percent) and Protestant Christians (76 percent). Three-fourths (76 percent) of these providers reported completion of in-service training in family planning provision. On average, these 49 providers were 37 years old and had 11 years of experience as a health care provider (see Table 2). More than 90 percent of included providers were registered or community nurses (data not shown).

Table 2.

Characteristics of family planning providers and new clients interviewed at 19 health facilities in Kisumu, Kenya 2012

| Provider interview data

|

3rd party observation data

|

Client exit interview data

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Providers with both simulated client and provider interview data | Providers with provider interview data but no simulated client data | Providers with both simulated client & 3rd party observation data | Providers without both simulated client & 3rd party observation data | Providers with both simulated client & new client exit interview data | Providers without both simulated client & new client exit interview data | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| PROVIDERS | n=49 | n=57 | n=44 | n=62 | n=31 | n=75 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Sex | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Female | 88% | 77% | 89% | 77% | 87% | 80% |

| Male | 12% | 23% | 11% | 23% | 13% | 20% |

|

| ||||||

| Religion | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Christian-Catholic | 24% | 33% | 27% | 31% | 35% | 27% |

| Christian-Protestant/other Christian | 76% | 63% | 73% | 66% | 65% | 71% |

| Muslim | 0% | 4% | 0% | 3% | 0% | 3% |

|

| ||||||

| Has received in-service training in family planning provision | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 76% | 68% | 77% | 68% | 84% * | 67% * |

| No | 24% | 32% | 23% | 32% | 16% * | 33% * |

|

| ||||||

| Mean age in years | 36 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 36 |

| Mean number of years as health care provider | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 11 |

The 49 providers who were both interviewed and visited by a simulated client did not differ significantly from those completing interviews but who lack a simulated client visit (n=57) in terms of age, gender, religion, years of experience, or training in family planning. Similarly, the 44 providers with data from both third party observations and simulated client visits were not significantly different from the 62 providers lacking one or both of these types of data. Those providers with both new client exit interview and simulated client data (n=31) differed in one respect from those providers with only one or none of these data sources (n=75); the 31 providers with both real and simulated client data were more likely (84 versus 67 percent, p=0.074) to have in-service training in the provision of family planning (see Table 2).

Results

Prevalence of Quality-Related Behaviors as Measured by Simulated Client Data

Simulated clients visited and assessed the service delivery practices of 52 family planning providers. These providers performed strongly in both aspects of method choice, nearly always discussing multiple methods and inquiring into the client’s family planning preferences (Table 3). Providers also performed well with simulated clients in terms of select aspects of information giving, client relations, and adherence to follow-up mechanisms. Between two-thirds and three-quarters of providers helped the client to select a method, discussed side effects, gave instruction on correct method use, engaged with the client in a respectful manner, and told the client when and where to go for resupply of their method. Other high quality practices were less universal, with fewer than half of providers suggesting ways to manage contraceptive side effects, inquiring as to whether or not the client had any questions, supplying a reminder card for a return visit, or telling the client appropriate actions if they encountered a problem with their selected method. Finally, less than 15 percent of providers were found to engage in such practices as discussing possible warning signs and their appropriate management, inquiry into the client’s reproductive goals, taking the client’s medical history, and offering integrated services.

Table 3.

Family planning providers achieving quality-of-care indicators during simulated client visits occurring in 19 health facilities in Kisumu, Kenya 2012

| n=52 providers | |

|---|---|

| CHOICE | |

|

| |

| Provider discussed 2+ methods with client | 96.2% |

| Provider asked the client their preferred method | 98.1% |

|

| |

| INFORMATION | |

|

| |

| Provider helped the client select a method | 67.3% |

| Provider discussed side effects | 69.2% |

| Provider discussed management of side effects | 48.1% |

| Provider discussed warning signs | 5.8% |

| Provider discussed what to do if warning signs occur | 5.8% |

| Provider told client how to use selected method | 75.0% |

|

| |

| RELATIONS | |

|

| |

| Provider treated client with respect | 86.5% |

| Provider asked the client their reproductive goals | 5.8% |

| Provider asked the client if they have any questions | 38.5% |

|

| |

| TECHNICAL COMPETENCE | |

|

| |

| Provider took the client’s medical history | 13.5% |

|

| |

| FOLLOW-UP MECHANISM | |

|

| |

| Provider told client when to return for resupply/follow-up | 76.9% |

| Provider gave client an appointment/reminder card | 38.5% |

| Provider told the client what to do if they experience problems | 26.9% |

| Provider told the client where to go for resupply (n=22)* | 70.0% |

|

| |

| INTEGRATION | |

|

| |

| Provider offered client services in addition to family planning | 9.6% |

Sample size is smaller for this indicator as long-acting methods do not require re-supply in the short-term and therefore are not included in the denominator

Comparing Simulated Client Data and Provider Interview Data

In the comparison of simulated client data with data from provider interviews, the prevalence of each indicator varies by as much as 45 percentage points between the two instruments (Table 4). In most cases, the prevalence of high quality provider behavior is greater when measured by provider interviews compared to measurements from simulated client observations, as expected. However, for three quality indicators, simulated clients rated provider performance higher than provider self-reports. This was true for explaining proper method use (Table 4) as well as for two indicators displayed only in the Appendix table2: soliciting client preference and informing clients when to return for additional services (Table A1).

Table 4.

Comparing results of simulated client visits and provider interviews in the measurement of quality-of-care indicators among 49 family planning service providers; data collected in 19 health facilities in Kisumu, Kenya 2012

| Simulated Clients | Provider Interviews | Percent Agreement (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive Predictive Value | Positive Likelihood Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INFORMATION | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider helped the client select a method | 67% | 82% | 53% | (38, 68) | 6% (1/16) | (0, 30) | 63% (25/40) | (4, 77) | 0.8 |

| Provider discussed side effects | 67% | 82% | 61% | (46, 75) | 19% (3/16) | (4, 46) | 68% (27/40) | (51, 81) | 1.0 |

| Provider discussed warning signs | 6% | 18% | 80% | (66, 90) | 83% (38/46) | (69, 92) | 11% (1/9) | (0, 48) | NA* |

| Provider told client how to use selected method | 73% | 51% | 49% | (34, 64) | 46% (6/13) | (19, 75) | 72% (18/25) | (51, 88) | 0.9 |

|

| |||||||||

| RELATIONS | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider asked the client their reproductive goals | 6% | 51% | 51% | (36, 66) | 50% (23/46) | (35, 65) | 8% (2/25) | (1, 26) | NA* |

|

| |||||||||

| FOLLOW-UP MECHANISM | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider told client when to return for resupply/follow-up | 78% | 59% | 45% | (31, 60) | 18% (2/11) | (2, 52) | 69% (20/29) | (49, 85) | 0.6 |

Test characteristics not estimated if based on 5 or fewer observations

Table A1.

Comparing results of simulated client visits and provider interviews in the measurement of quality-of-care indicators among 49 family planning service providers; data collected in 19 health facilities in Kisumu, Kenya 2012

| Simulated Clients |

Provider Interviews |

Percent Agreement (95% CI) |

Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Predictive Value | Likelihood Ratio |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| + | − | + | − | |||||||||||

| CHOICE | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider discussed 2+ methods with client | 96% | 98% | 94% | (83, 99) | 98% (46/47) | (89, 100) | NA* (n=2) | --- | 96% (46/48) | (86, 100) | NA* (n=1) | --- | NA* | NA* |

| Provider asked the client their preferred method | 98% | 61% | 63% | (48, 77) | 63% (30/48) | (47, 76) | NA* (n=1) | --- | 100% (30/30) | (88, 100) | 5% (1/19) | (0, 26) | NA* | NA* |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| INFORMATION | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider helped the client select a method | 67% | 82% | 53% | (38, 68) | 76% (25/33) | (58, 89) | 6% (1/16) | (0, 30) | 63% (25/40) | (4, 77) | 11% (1/9) | (0, 48) | 0.8 | 4.0 |

| Provider discussed side effects | 67% | 82% | 61% | (46, 75) | 82% (27/33) | (65, 93) | 19% (3/16) | (4, 46) | 68% (27/40) | (51, 81) | 33% (3/9) | (8, 70) | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Provider discussed warning signs | 6% | 18% | 80% | (66, 90) | NA* (n=3) | --- | 83% (38/46) | (69, 92) | 11% (1/9) | (0, 48) | 95% (38/40) | (83, 99) | NA* | NA* |

| Provider told client how to use selected method | 73% | 51% | 49% | (34, 64) | 50% (18/36) | (33, 67) | 46% (6/13) | (19, 75) | 72% (18/25) | (51, 88) | 25% (6/24) | (10, 47) | 0.9 | 1.1 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| RELATIONS | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider asked the client their reproductive goals | 6% | 51% | 51% | (36, 66) | NA* (n=3) | --- | 50% (23/46) | (35, 65) | 8% (2/25) | (1, 26) | 96% (23/24) | (79, 100) | NA* | NA* |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| FOLLOW-UP MECHANISM | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider told client when to return for resupply/follow-up | 78% | 59% | 45% | (31, 60) | 53% (20/38) | (36, 69) | 18% (2/11) | (2, 52) | 69% (20/29) | (49, 85) | 10% (2/20) | (1, 32) | 0.6 | 2.6 |

Test characteristics not estimated if based on 5 or fewer observations

Among the six indicators in Table 4, agreement was low (below 62 percent) for all but one: discussion of warning signs (80 percent agreement). We hypothesized that specificity would be low as a result of provider reluctance to report negative practices. In other words, providers who did not engage in a particular behavior with a simulated client (the reference standard) might nevertheless report such practices. Our results confirm this hypothesis: specificity was low for all but one of the six indicators with sufficient sample size; 83 percent of providers who did not discuss warning signs with a simulated client reported that they do not engage in this behavior with clients.

The positive predictive values and likelihood ratios displayed in Table 4 describe the ability of provider interviews to accurately predict how providers behaved with simulated clients. The PPV, a measure of whether a provider reported a specified practice will also engage in this behavior with an actual client in populations with similar prevalence, was low across all indicators. For four indicators, PPV ranged from 63 to 72 percent (method selection, side effects, method use, and resupply). This tells us that approximately one third of providers who report engaging in these four practices related to client information and follow-up did not actually do so when serving a simulated client. Provider self-reports indicating that they discuss warning signs (11 percent PPV) and reproductive goals (8 percent PPV) with clients only very weakly predicted that providers would have such discussions with a simulated client, suggesting the vast majority reporting such behavior do not actually do it. Surprisingly, provider interview data often revealed low NPV (data shown in appendix). Reasons for this are considered in the discussion section.

To consider the predictive ability of these indicators irrespective of the prevalence of the indicators, we turn to the likelihood ratios. Ratios could be computed for only four indicators, due to low sample size restricting the ability to calculate sensitivity and specificity. Two of these indicators have zero predictive ability: reporting discussion of side effects and giving instructions on correct method use. For the remaining two indicators, which relate to helping the client select a method and ensuring timely follow-up, a positive response from the provider during the interview actually very weakly predicted that the provider would not engage in these activities with a simulated client.

Comparing Simulated Client Data and Third Party Observation Data

In comparing data collected by simulated clients with data from third party observations, most indicators had a difference in prevalence between the two instruments ranging from 10 to 50 percentage points, with simulated client results often lower than the prevalence as determined by third party observation data (Table 5). For two indicators, discussion of multiple methods and informing the client when to return for follow-up, simulated clients rated provider performance slightly higher than third party observers. For the remaining indicators, the prevalence did not differ between the two instruments or was only slightly (less than 10 percentage points) lower for the simulated client checklist.

Table 5.

Comparing results of simulated client visits and third party observations in the measurement of quality-of-care indicators among 44 family planning service providers; data collected in 19 health facilities in Kisumu, Kenya 2012

| Simulated Clients | Third Party Observations | Percent Agreement (95% CI) | Specificity (ratio) (95% CI) | Positive Predictive Value (ratio) (95% CI) | Positive Likelihood Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INFORMATION | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider helped the client select a method | 64% | 98% | 61% | (46, 76) | 0% (0/16) | (0, 21) | 63% (27/43) | (47, 77) | 1.0 |

| Provider discussed side effects | 66% | 80% | 64% | (48, 78) | 27% (4/15) | (8, 55) | 69% (24/35) | (51, 83) | 1.1 |

| Provider discussed management of side effects | 45% | 52% | 52% | (37, 68) | 50% (12/24) | (29, 71) | 48% (11/23) | (27, 69) | 1.1 |

| Provider told client how to use selected method | 73% | 73% | 59% | (43, 74) | 25% (3/12) | (6, 57) | 72% (23/32) | (53, 86) | 1.0 |

|

| |||||||||

| RELATIONS | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider asked the client their reproductive goals | 2% | 41% | 57% | (41, 72) | 58% (25/43) | (42, 73) | 0% (0/18) | (0, 19) | NA* |

| Provider asked the client if they have any questions | 34% | 61% | 45% | (30, 61) | 38% (11/29) | (21, 58) | 33% (9/27) | (17, 54) | 1.0 |

|

| |||||||||

| FOLLOW-UP MECHANISM | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider told client when to return for resupply/follow-up (n=43) | 79% | 74% | 63% | (47, 77) | 22% (2/9) | (3, 60) | 78% (25/32) | (60, 91) | 0.9 |

| Provider gave client an appointment/reminder card | 36% | 66% | 39% | (24, 55) | 29% (8/28) | (13, 49) | 31% (9/29) | (15, 51) | 0.8 |

| Provider told the client what to do if they experience problems (n=41) | 27% | 76% | 37% | (22, 53) | 23% (7/30) | (10, 42) | 26% (8/31) | (12, 45) | 0.9 |

|

| |||||||||

| INTEGRATATION | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider offered client services in addition to family planning | 11% | 61% | 41% | (26, 57) | 38% (15/39) | (23, 55) | 11% (3/27) | (2, 29) | NA* |

Test characteristics not estimated if based on 5 or fewer observations

Three indicators had a high prevalence as reported by both simulated clients and the third party observer: discussion of two or more methods, solicitation of client’s preferred method, and provider treating client with respect (data shown in the Appendix). Three more indicators had a very low prevalence among both instruments: discussion and management of warning signs and taking the client’s medical history. In both cases, whether the indicator was especially high or notably low, agreement was high across the board (84 to 95 percent). Unfortunately, strong agreement and high or low prevalence resulted in low cell counts, making it impossible to calculate specificity. For those statistics that could be computed, specificity was always high (low to mid 90s). Data on these six indicators are shown in the appendix (Table A2). Among the remaining 10 indicators, poor agreement (below 65 percent) was found for all indicators and specificity was universally low, as expected, ranging from zero to 58 percent (Table 5).

Table A2.

Comparing results of simulated client visits and third party observations in the measurement of quality-of-care indicators among 44 family planning service providers; data collected in 19 health facilities in Kisumu, Kenya 2012

| Simulated Clients |

Third Party Observations |

Percent Agreement (95% CI) |

Sensitivity (ratio) (95% CI) |

Specificity (ratio) (95% CI) |

Predictive Value (ratio) (95% CI) | Likelihood Ratio |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| + | − | + | − | |||||||||||

| CHOICE | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider discussed 2+ methods with client | 95% | 89% | 84% | (70, 93) | 88% (37/42) | (74, 96) | NA* (n=2) | --- | 95% (37/39) | (83, 99) | NA* (n=5) | --- | NA* | NA* |

| Provider asked the client their preferred method | 98% | 98% | 95% | (85, 99) | 98% (42/43) | (88, 100) | NA* (n=1) | --- | 98% (42/43) | (88, 100) | NA* (n=1) | --- | NA* | NA* |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| INFORMATION | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider helped the client select a method | 64% | 98% | 61% | (46, 76) | 96% (27/28) | (82, 99) | 0% (0/16) | (0, 21) | 63% (27/43) | (47, 77) | NA* (n=1) | --- | 1.0 | NA** |

| Provider discussed side effects | 66% | 80% | 64% | (48, 78) | 83% (24/29) | (64, 94) | 27% (4/15) | (8, 55) | 69% (24/35) | (51, 83) | 44% (4/9) | (14, 79) | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| Provider discussed management of side effects | 45% | 52% | 52% | (37, 68) | 55% (11/20) | (32, 77) | 50% (12/24) | (29, 71) | 48% (11/23) | (27, 69) | 57% (12/21) | (34, 78) | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Provider discussed warning signs | 2% | 7% | 95% | (85, 99) | NA* (n=1) | --- | 95% (41/43) | (84, 99) | NA * (n=3) | --- | 100% (41/41) | (91, 100) | NA* | NA* |

| Provider discussed what to do if warning signs occur | 2% | 7% | 95% | (85, 99) | NA* (n=1) | --- | 95% (41/43) | (84, 99) | NA * (n=3) | --- | 100% (41/41) | (91, 100) | NA* | NA* |

| Provider told client how to use selected method | 73% | 73% | 59% | (43, 74) | 72% (23/32) | (53, 86) | 25% (3/12) | (6, 57) | 72% (23/32) | (53, 86) | 25% (3/12) | (6, 57) | 1.0 | 1.1 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| RELATIONS | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider treated client with respect | 89% | 100% | 89% | (75, 96) | 100% (39/39) | (91, 100) | NA* (n=5) | --- | 89% (39/44) | (75, 96) | NA* (n=0) | --- | NA* | NA* |

| Provider asked the client their reproductive goals | 2% | 41% | 57% | (41, 72) | NA* (n=1) | --- | 58% (25/43) | (42, 73) | 0% (0/18) | (0, 19) | 96% (25/26) | (80, 100) | NA* | NA* |

| Provider asked the client if they have any questions | 34% | 61% | 45% | (30, 61) | 60% (9/15) | (32, 84) | 38% (11/29) | (21, 58) | 33% (9/27) | (17, 54) | 65% (11/17) | (38, 86) | 1.0 | 1.1 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| TECHNICAL COMPETENCE | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider took the client’s medical history (n=43) | 12% | 12% | 86% | (72, 95) | NA* (n=5) | --- | 92% (35/38) | (79, 98) | NA* (n=5) | --- | 92% (35/38) | (79, 98) | NA* | NA* |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| FOLLOW-UP MECHANISM | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider told client when to return for resupply/follow-up (n=43) | 79% | 74% | 63% | (47, 77) | 74% (25/34) | (56, 87) | 22% (2/9) | (3, 60) | 78% (25/32) | (60, 91) | 18% (2/11) | (2, 52) | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| Provider gave client an appointment/reminder card | 36% | 66% | 39% | (24, 55) | 56% (9/16) | (30, 80) | 29% (8/28) | (13, 49) | 31% (9/29) | (15, 51) | 53% (8/15) | (27, 79) | 0.8 | 1.5 |

| Provider told the client what to do if they experience problems (n=41) | 27% | 76% | 37% | (22, 53) | 73% (8/11) | (39, 94) | 23% (7/30) | (10, 42) | 26% (8/31) | (12, 45) | 70% (7/10) | (35, 93) | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| Provider told the client where to go for resupply (n=14)*** | 64% | 79% | 57% | (29, 82) | 78% (7/9) | (40, 97) | NA* (n=5) | --- | 64% (7/11) | (31, 89) | NA* (n=3) | --- | NA* | NA* |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| INTEGRATATION | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider offered client services in addition to family planning | 11% | 61% | 41% | (26, 57) | NA* (n=5) | --- | 38% (15/39) | (23, 55) | 11% (3/27) | (2, 29) | 88% (15/17) | (64, 99) | NA* | NA* |

Test characteristics not estimated if based on 5 or fewer observations

As specificity approaches zero, the negative likelihood ratio approaches infinity

Sample size is smaller for this indicator as long-acting methods do not require re-supply in the short-term and therefore are not included in the denominator

The PPV, a measure of whether a provider observed in a specified practice will also engage in this behavior with an actual client in populations with similar prevalence, was below 70 percent for eight out of the 10 indicators presented in Table 5. In other words, providers who practiced these eight behaviors when observed by a third party often failed to do so with the simulated client. The remaining indicators – instructing the client on correct method use and telling the client when to return for resupply – had PPVs of 72 and 78 percent, respectively. LRs, which have the benefit of avoiding influence by the prevalence of the indicator, were close to “1” for all eight of the indicators for which LR+ values could be calculated, indicating poor predictive ability.

Comparing Simulated Client Data and Client Exit Interview Data

The prevalence of quality-related behaviors measured by simulated clients was lower than that measured by exit client interviews for the majority of the indicators (Table 6). Unexpectedly, discussing more than one method (data shown in Table A3) or helping the client to select a method was rated much higher (16 to 29 percentage points) by simulated clients than by actual exiting clients. One indicator, soliciting client preferences, had the same prevalence among both instruments.

Table 6.

Comparing results of simulated client visits and new client exit interviews in the measurement of quality-of-care indicators among 31 family planning service providers; data collected in 19 health facilities in Kisumu, Kenya 2012

| Simulated clients | New Client Exit Interviews | Percent Agreement (95% CI) | Specificity (ratio) (95% CI) | Positive Predictive Value (ratio) (95% CI) | Positive Likelihood Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INFORMATION | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider helped the client select a method | 61% | 32% | 45% | (27, 64) | 67% (8/12) | (35, 90) | 60% (6/10) | (26, 88) | 1.0 |

| Provider discussed side effects | 61% | 87% | 61% | (42, 78) | 17% (2/12) | (2, 48) | 63% (17/27) | (42, 81) | 1.1 |

| Provider told client how to use selected method | 68% | 87% | 68% | (49, 83) | 20% (2/10) | (3, 56) | 70% (19/27) | (50, 86) | 1.1 |

|

| |||||||||

| RELATIONS | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider asked the client their reproductive goals | 0% | 77% | 23% | (10, 41) | 23% (7/31) | (10, 41) | 0% (0/24) | (0, 14) | NA* |

| Provider asked the client if they have any questions | 35% | 84% | 45% | (27, 64) | 20% (4/20) | (8, 44) | 38% (10/26) | (20, 59) | 1.1 |

|

| |||||||||

| FOLLOW-UP MECHANISM | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider told client when to return for resupply/follow-up (n=30) | 80% | 93% | 73% | (54, 88) | 0% (0/6) | (0, 46) | 79% (22/28) | (59, 92) | 0.9 |

| Provider told the client what to do if they experience problems | 32% | 84% | 35% | (19, 55) | 14% (3/21) | (3, 36) | 31% (8/26) | (14, 52) | 0.9 |

|

| |||||||||

| INTEGRATATION | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Provider offered client services in addition to family planning | 13% | 74% | 32% | (17, 51) | 26% (7/27) | (11, 46) | 13% (3/23) | (3, 34) | NA* |

Test characteristics not estimated if based on 5 or fewer observations

Table A3.

Comparing results of simulated client visits and new client exit interviews in the measurement of quality-of-care indicators among 31 family planning service providers; data collected in 19 health facilities in Kisumu, Kenya 2012

| Simulated clients | New Client Exit Interviews | Percent Agreement (95% CI) | Sensitivity (ratio) (95% CI) | Specificity (ratio) (95% CI) | Predictive Value (ratio) (95% CI) | Likelihood Ratio | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| + | − | + | − | |||||||||||

| CHOICE | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider discussed 2+ methods with client | 97% | 81% | 77% | (59, 90) | 80% (24/30) | (61, 92) | NA* (n=1) | --- | 96% (24/25) | (80, 100) | 0% (0/6) | (0, 46) | NA* | NA* |

| Provider asked the client their preferred method | 97% | 97% | 93% | (77, 99) | 96% (27/28) | (82, 100) | NA* (n=1) | --- | 96% (27/28) | (82, 100) | NA* (n=1) | --- | NA* | NA* |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| INFORMATION | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider helped the client select a method | 61% | 32% | 45% | (27, 64) | 32% (6/19) | (13, 57) | 67% (8/12) | (35, 90) | 60% (6/10) | (26, 88) | 38% (8/21) | (18, 62) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Provider discussed side effects | 61% | 87% | 61% | (42, 78) | 89% (17/19) | (67, 99) | 17% (2/12) | (2, 48) | 63% (17/27) | (42, 81) | NA* (n=4) | --- | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| Provider told client how to use selected method | 68% | 87% | 68% | (49, 83) | 90% (19/21) | (70, 99) | 20% (2/10) | (3, 56) | 70% (19/27) | (50, 86) | NA* (n=4) | --- | 1.1 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| RELATIONS | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider treated client with respect | 87% | 100% | 87% | (70, 96) | 100% (27/27) | (87, 100) | NA* (n=4) | --- | 87% (27/31) | (70, 96) | NA* (n=0) | --- | NA* | NA* |

| Provider asked the client their reproductive goals | 0% | 77% | 23% | (10, 41) | NA* (n=0) | --- | 23% (7/31) | (10, 41) | 0% (0/24) | (0, 14) | 100% (7/7) | (59, 100) | NA* | NA* |

| Provider asked the client if they have any questions | 35% | 84% | 45% | (27, 64) | 91% (10/11) | (59, 100) | 20% (4/20) | (8, 44) | 38% (10/26) | (20, 59) | NA* (n=5) | --- | 1.1 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| FOLLOW-UP MECHANISM | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider told client when to return for resupply/follow-up (n=30) | 80% | 93% | 73% | (54, 88) | 92% (22/24) | (73, 99) | 0% (0/6) | (0, 46) | 79% (22/28) | (59, 92) | NA* N=2) | --- | 0.9 | NA** |

| Provider told the client what to do if they experience problems | 32% | 84% | 35% | (19, 55) | 80% (8/10) | (44, 98) | 14% (3/21) | (3, 36) | 31% (8/26) | (14, 52) | NA* (n=5) | --- | 0.9 | 1.4 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| INTEGRATE | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Provider offered client services in addition to family planning | 13% | 74% | 32% | (17, 51) | NA* (n=4) | --- | 26% (7/27) | (11, 46) | 13% (3/23) | (3, 34) | 88% (7/8) | (47, 100) | NA* | NA* |

Test characteristics not estimated if based on 5 or fewer observations

As specificity approaches zero, the negative likelihood ratio approaches infinity

Three indicators had high prevalence, according to both instruments: discussion of two or more methods, solicitation of client’s preferred method, and provider treating client with respect. Agreement for these three indicators ranged from 77 to 93 percent and, due to small sample sizes, specificity could not be computed for any of the three. Data are therefore available in the appendix (Table A3). Among the remaining eight indicators, agreement was low (below 70 percent) for all but one indicator; agreement was 73 percent for providers telling clients when to return for resupply (Table 6). Results for specificity of client exit interviews matched our expectations, with values below 50 percent for all but one indicator; helping the client to select a method had a specificity of 67 percent.

Positive predictive values ranged from zero to 70 percent for seven of the eight indictors; once again, instructions on when to return for resupply were slightly better with a PPV of 79 percent (Table 6). The low predictive values across seven indicators suggest that many or all of the providers who were reported by clients to engage in each of these behaviors often did not do so when serving simulated clients. LR values could only be calculated for six indicators due to small sample size. Across all indicators of quality, positive responses to the client exit interview were extremely poor predictors of the behavior of providers when attending to simulated clients, as demonstrated by LR+ results extremely close to the null value of one.

Discussion

Three standard instruments designed to measure family planning service quality were assessed for their ability to accurately classify and predict provider behavior, with simulated client data serving as the referent. Third party observations quite accurately measured discussion and management of warning signs, respectful client treatment, and all indicators related to method choice and provider competence. At the same time, several indicators of information, relations, follow-up, and integration performed poorly through third party observations. The low specificity and PPVs for nearly all indicators within these categories suggests a poor ability of observational data to identify providers not engaging in high quality service provision and weak confidence that providers observed participating in certain behaviors are likely to do so when unobserved. These findings support the common hypothesis that observational data is subject to Hawthorne bias, as discussed previously.

Like third party observations, interviews with new family planning clients as they exit the facility did a good job of accurately measuring aspects of method choice and client relations, including the client’s method preference and respectful client treatment. Yet misclassification of negative provider behavior was nearly universal among the remaining indicators and very low PPVs were found for most indicators of client relations, follow-up, and integration. Overall, providers did not engage with simulated clients in a way that was consistent with interview responses from actual clients.

The different findings arising from actual and simulated client data could be the result of a variety of factors. First, clients may knowingly give an incorrect response in an effort to avoid giving negative feedback on their provider. It is also possible that providers modify their behavior with clients when they know the client will be interviewed by a research team. Clients may also unknowingly offer inaccurate information due to a lack of understanding of the question. For example, the client may not know whether or not the provider “helped” them to select a method because they may not know what constitutes “help”. If the client already knew the method she wanted to use upon arrival at the facility and the provider simply asked some questions to determine the client’s medical eligibility, the client may not interpret this as receiving help from the provider in selecting an appropriate contraceptive method. It is also possible that some clients had poor recall of their counseling session. For example, a client who has already selected a method prior to arriving at the health facility may not notice or remember a provider who offers information on other available methods or the client may even preclude such a discussion by verbalizing her predetermined preference early in the counseling session.

Data resulting from interviews with providers were markedly different from simulated client data, with only one indicator – discussion of multiple methods – performing with a high degree of accuracy in predicting actual behavior. The remaining indicators were plagued with low specificity and/or low predictive values. In discussion of warning signs, for example, only 11 percent of providers who self-reported this behavior were found to actually do so with a simulated client; for discussion of reproductive goals, the PPV was a mere eight percent. Surprisingly, the majority of indicators also had very low NPVs, where we would expect this to be high given providers have no incentive to hide positive behavior. For example, nearly all of the providers who reported not asking clients about their method preference actually did so with a simulated client. It is possible that providers misunderstood this question. Regarding the practice of “helping” clients to select a method, providers are trained to ensure clients have the freedom to choose their preferred method, without coercion on the part of the provider; as such providers may shy away from reporting their helpfulness in method selection for fear of being reprimanded for engaging with clients in too directive of a manner. Reasons why providers would fail to report discussion of side effects, instructions on correct method use, and directions for resupply are not obvious to the study team. The results from this questionnaire, in combination, suggest that provider interview responses are of little overall value in measuring actual provider behavior.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, a number of simulated client studies have been employed to assess family planning service quality within the regions of Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia (Hardee et al., 2001, Huntington et al., 1990, Leon et al., 2007, Leon et al., 1994, Maynard-Tucker, 1994, Naik et al., 2010, Population Council, 1992, Schuler et al., 1985). Findings from these studies frequently highlight deficiencies in service quality, utilizing the Bruce framework to identify areas of investigation, and on occasion have been used to measure the impact of recent provider trainings (Huntington et al., 1990, Population Council, 1992, Naik et al., 2010) or assess the quality of services for a specific facility type (Hardee et al., 2001). To our knowledge, however, the simulated client method has not been used previously to assess the accuracy of standard instruments used to measure family planning service quality in measuring actual provider behavior, highlighting the unique contribution of this study to the existing literature.

Limitations

In the initial study design, all 108 on-duty providers at the 19 participating facilities were to receive a visit by a simulated client. This design assumed that all service providers who provide family planning services would do so on a regular basis throughout the study period. Many facilities, however, utilize a service provider rotation schedule in which only one or a small number of the total providers at the facility offer family planning services each month or each quarter. As a result, it was not possible to collect simulated client data on all family planning providers at the 19 facilities during the study period; additionally, many providers were not observed by a third party observer or did not see new clients who were subsequently interviewed by our research team. Multiple attempts were made to collect all types of data on all providers at the participating facilities by repeated visits to facilities by all members the data collection team and the simulated clients. Regarding the simulated clients, these repeat visits often resulted in multiple observations (by different simulated clients) of the same provider.

Our inability to collect all types of data for all providers may have biased our study results. However, as indicated above, few differences were seen in the background and professional characteristics of those providers included in the analysis, compared to those that could not be included. Only in the analysis of client interview data did we find a difference in that the included providers were more often trained in family planning provision. It is unclear how this difference may have affected the results of this aspect of our analysis.

One possible limitation of this analysis is that the reference standard is based on a single simulated client visit; therefore the validity of the results depends on the assumption that providers are consistent in their behaviors across all visits. We were able to test the sensitivity of our results to this assumption by repeating our analysis, using a different random number seed to randomly select a visit for those providers (n=31) who received more than one simulated client visit. Most numerical results were unchanged or marginally affected in the sensitivity analysis, and all substantive conclusions remained the same. In addition, the fact that there are systematic differences in the prevalence of many indicators of provider behavior obtained from the different instruments suggests that the observed inconsistency in indicators at the consultation level is not solely due to random variations in provider behavior across consultations. This supports our assertion that biases exist in the standard instruments for measuring provider behavior.

Concerns exist about the appropriateness of the simulated client method as a reference standard. It is possible that simulated clients will have imperfect understanding and/or recall of the events taking place during counseling sessions with the family planning service providers. Previous studies suggest several strategies to increase the reliability and validity of simulated client data including careful selection and training of simulated clients and use of a focused and objective instrument (Brown et al., 1995, Leon et al., 1994). Following this guidance, we took several steps to ensure data collected by simulated clients are as accurate and reliable as possible. For example, the use of an objective checklist instrument helped to reduce confusion on the part of the simulated client when assessing providers and eliminated any need for subjective interpretation of quality. Simulated clients participated in a week-long training with extensive role-play, followed by several days of pilot-testing the checklist in non-study facilities. During role-play activities, the study PI reviewed completed checklists and verified accurate assessments of quality as well as reliability across all six simulated clients. Additionally, role play activities and pilot-testing served to help simulated clients become comfortable and familiar with the checklist instrument, the type of information they were collecting, and their role as under-cover data collectors. Simulated clients recorded their observations as soon as possible (no more than two hours after concluding the facility visit), upon leaving the health facility, and subsequently reviewed their responses with the study PI on a daily basis, helping to reduce imperfect recall or recording errors. Lastly, simulated clients were carefully selected to represent the clients in the catchment area of participating facilities, helping to ensure their believability as real clients. With all these precautions in place, however, it is important to bear in mind that simulated clients may not completely mimic actual clients in certain ways that could influence provider behavior. For example, simulated clients did not bring children with them on their visits to facilities. As such, a provider may be less likely to offer integrated services related to child health such as immunizations.

Lastly, while this study demonstrates the feasibility of using simulated clients in a sample of 19 facilities, little is known about the logistical or practical constraints of implementing this method of data collection as part of a large-scale, population-based survey. While training of simulated clients is similar in scope to other facility-level data collection instruments, the recruitment of women who realistically represent the catchment area of selected facilities and who demonstrate strong recall ability may require more effort and planning. Similarly, monitoring the quality of such data collection may be challenging, given the covert nature of this method of data collection.

Findings and Application

These study results have implications for future assessments and investigations into family planning service quality as well as quality improvement interventions. Reliance on standard service quality instruments may provide inaccurate data on actual provider practice, misinforming results of service quality assessments and evaluations and potentially biasing results of multivariate analyses investigating the relationship between family planning service quality and contraceptive use.

In light of these findings, modified or expanded methods of data collection on family planning service quality are warranted. Two of the three standard instruments (third party observations and client exit interview) demonstrated some utility for some quality-related behaviors (most notably method choice) and therefore may provide valid data on provider behaviors in future studies. In order to increase the accuracy of data from provider and client interviews, it would be wise to consider revisions to questions that appear to be misunderstood by family planning clients and providers, most notably, questions related to helping the client select a method and soliciting the client’s method preference.

Additionally, simulated client data should be included in quality assessments whenever ethically and logistically feasible. Such inclusion will allow for more complex analysis through triangulation among the instruments; for example, comparing third party observations or provider interviews with simulated client data can highlight which behaviors providers know they should be doing but aren’t actually doing. A comparison of data from actual and simulated clients may help to identify specific types of information not being retained by most clients. Simulated client data can also supplement traditional instruments by illuminating practices not detectable via standard instruments such as corrupt practices or lack of provider availability (Tumlinson et al., 2013). Greater use of the simulated client methodology in more settings will allow for better identification of areas of deficiency in the quality of family planning service delivery.