Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study is to compare the effectiveness, hemodynamic changes and duration of sedation and analgesia between combinations of fortwin-phenergan-midazolam (FPM) and ketamine - midazolam (KM) along with local anesthesia for the surgeries done under the umbrella of monitored anesthesia care.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 50 patients undergoing surgeries as tympanoplasty, septoplasty, lip repair, dacrocystectomy and cataract under local anesthesia, randomly received either intravenous (IV) fortwin 0.3 mg/kg over 1 min followed by IV midazolam 0.04 mg/kg plus IV phenergan 12.5 mg (Group FPM) or IV ketamine 0.3 mg/kg over 1 min plus IV midazolam 0.04 mg/kg (Group KM). Sedation was titrated to Ramsay sedation score (RSS) of 3. Patients’ mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), saturation peripheral pulse, duration of sedation and need for intraoperative rescue sedation/analgesic were recorded and compared. Satisfaction of patients (using a 1-7 point Likert verbal rating scale) and readiness for discharge towards (time to Aldrete score of 10) were also determined.

Result:

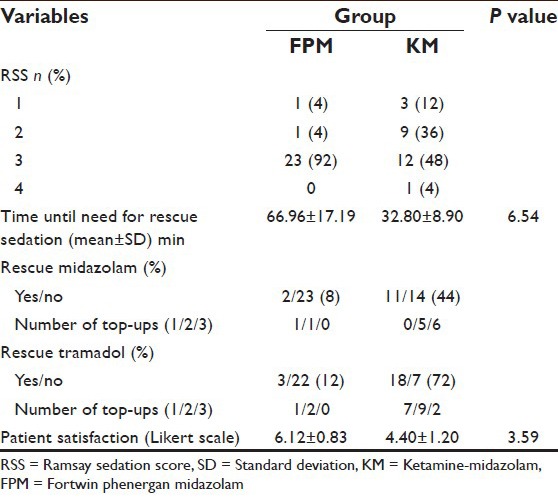

Group KM had significant rise in HR (20-25%) and MAP (25-30%) from 30 min after the bolus dose given until the end of the surgery in contrast to Group FPM. The target sedation level (RSS ≥ 3) was higher in Group FPM (n = 23 [92%]) as compared with Group KM (n = 12 [48%]). Time until need for rescue sedation was 66.96 ± 17.19 min in FPM and 32.80 ± 8.90 min in KM group. The patient satisfaction (Likert scale) is more with the FPM group (6.12 ± 0.83 vs. 4.40 ± 1.20).

Conclusion:

We found that the combination of FPM is superior to the KM combination as per the hemodynamic changes, duration of analgesia, patients’ satisfaction and efficacy of the drugs are concerned.

Keywords: Fortwin, ketamine, local anesthesia, midazolam, monitored anesthesia, phenergan, sedation

INTRODUCTION

Monitored anesthesia care (MAC) has been defined by the American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA), as a specific anesthesia service, meant for a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure done under local anesthesia along with sedation and analgesia.[1] This “conscious” sedation or twilight sleep[2] is a drug-induced depression of consciousness. The process puts the patient calm while remain awake and responsive to follow commands, either alone or accompanied by light tactile stimulation. No intervention is required for maintaining normal respiratory and cardiovascular functions. MAC, as per ASA, includes the nature of the procedure, clinical condition of the patient and/or the potential need to convert sedation to a general or regional anesthesia. The vital signs and level of consciousness as required for the surgical technique is monitored continuously by an Anesthesiologist. The purpose and the three fundamental elements of a conscious sedation during a MAC are safe sedation, control of the patients’ anxiety and pain[3] so that the patient remains motionless and can co-operate actively following verbal commands throughout the procedures. After the procedure is over, the anesthesiologist will discharge the patient fully awake.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

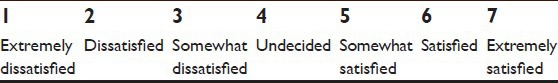

This prospective study was conducted in a teaching hospital during the period between May 2013 and February 2014, after informing the Ethical Committee and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Fifty patients of either sex, aged between 18 and 60 years of ASA Grades I and II, undergoing tympanoplasty, septoplasty, lip repair, dacrocystectomy or cataract surgery under local anesthesia were included. The patients were selected who had no known sensitivity to local anesthetic drug lignocaine, nonallergic to study drugs, not on pain perception modifying drugs, no history of use of any opioid or sedative medications in the month prior to surgery and nonalcoholics. Pregnant and lactating females were excluded from the study. Preanesthetic checkup of the patients to be included in the study, were done a day before surgery and were counselled regarding adequate starvation, sedation, local anesthesia and the operative procedures and were educated about the visual analog scale (VAS)[4] [Score A] and a 1-7 point Likert verbal rating scale[5] [Score B] regarding the rate of experience with the sedation and analgesia.

Score A.

Visual analog scale (0-10 cm)

Score B.

Likert scale

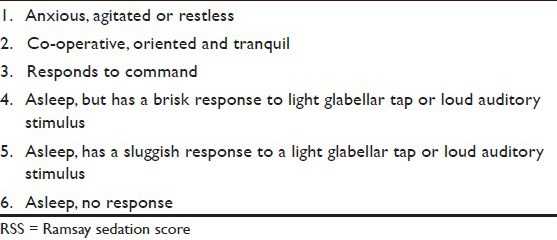

The patients were randomly divided into two equal groups, Group fortwin, phenergan, midazolam (FPM) and Group ketamine, midazolam (KM). Investigations were done according to the institution's protocol. On arrival in the operation theatre, multipara monitor for recording the patient's oxygen saturation, heart rate (HR), ECG, noninvasive arterial blood pressure, respiratory rate, was connected (Philips-Intellivue MP20). Ringer's lactate solution at 2 ml/kg was started intravenous (IV) through a 18 G cannula. Oxygen was administered through a nasal prong at 2 l/min rate.[6] No sedative premedication was used. Once drapings were done, group FPM (n = 25) received IV fortwin 0.3 mg/kg over 1 min followed by IV midazolam 0.04 mg/kg plus IV phenergan 12.5 mg. Group KM (n = 25) received IV ketamine 0.3 mg/kg over 1 min plus IV midazolam 0.04 mg/kg. During this period, the patients were assessed every 2 min using Ramsay sedation score (RSS) [Score C][7] until the target end point RSS = 3 was reached.

Score C.

Ramsay Sedation Score (sedation scale)

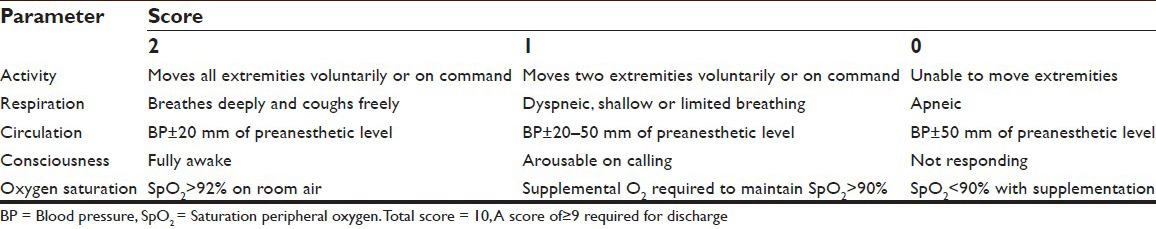

The surgeons were then allowed to administer local anesthetics using 2% lignocaine with adrenaline (6-7 ml) (1:200,000) in the incision line. It is essential for such delicate procedures to have a bloodless surgical field, which can be provided by the addition of a vasoconstrictor agent (usually adrenaline) to the local anesthetic infiltration.[8] Nerve blocks related to the procedures were done 15 min prior to the administration of IV bolus study drug. Surgery was commenced after confirming adequate analgesia. Intraoperatively HR, mean blood pressure mean arterial pressure (MAP) and saturation peripheral oxygen (SPO2) were recorded during loading of bolus dose of the study drugs and thereafter at 10-min intervals until the end of surgery. Sedation level (RSS) was assessed every 10 min and if RSS <3, rescue agents as analgesic (tramadol 1 mg/kg) and sedative (midazolam 0.01 mg/kg) were administered IV as common agents for both groups. The number of rescue doses was recorded. The protocol specified up to a maximum of three rescue doses. Inadequate analgesia was treated with infiltration of 2% lignocaine with adrenaline (2-3 ml more) at the surgical site and noted. At any time, if clinically indicated or if protocol-specified amount of rescue drugs were reached, the sedation technique was converted to any alternative sedative or anesthetic technique and the study was discontinued. Adverse events like bradypnea (RR <10 breaths/min), desaturation (SpO2 <90%), bradycardia (HR <45 bpm), hypotension (drop in systolic blood pressure >20% of baseline or MAP <60 mmHg sustained for >10 min), hypertension (an increase in systolic blood pressure or MAP >20% of baseline), nausea, vomiting or any other event during the procedure were noted. Bradycardia was treated with IV atropine sulfate 0.01 mg/kg, hypotension with fluid replacement, trendelenburg position and if needed, IV mephentermine sulfate 5 mg in incremental doses was administered. In case of bradypnea, patient was woken up and was asked to take deep breaths. Desaturation was treated by increasing O2 flow up to 5 liters and if needed, using bag mask ventilation with Bain's circuit. After the completion of surgery patients were shifted to the postanesthetic care unit where immediately on arrival, hemodynamic parameters, and degree of analgesia monitored, assessment of RSS done or any adverse effects were taken care of. All these were repeated every 30 min thereafter, until the patient leaves for the ward once an Aldrete score of 10 [Score D][9] was achieved.

Score D.

Modified Aldrete Score (postanaesthesia recovery score)

Requirement of postoperative analgesia was noted. The first dose of postoperative analgesic tramadol 100 mg IV was given at VAS >3 and was documented. On the postoperative day 1, in the surgical ward, the patients were asked to grade their overall satisfaction[10] using a 1-7 point Likert verbal rating scale by answering the question, “How would you rate your satisfaction with the sedation and analgesia you have received during surgery?” The targeted end point of our study was efficacy of the sedation technique, which was defined as the ability to complete the surgery without any rescue sedative and analgesic and the patient satisfaction score (1-7 point Likert verbal rating scale). Safety of the technique was based on analgesia/sedation-related intra or postoperative adverse event. Hemodynamics were evaluated using unpaired t-test for intergroup and paired t-test for within group comparisons. Categorical data were analyzed using Chi-square test. P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULT

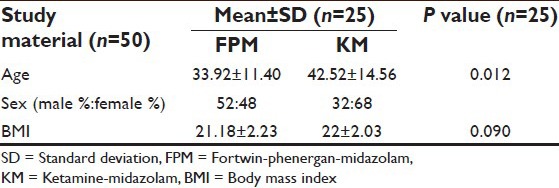

The results constituted the period of peroperative study until the patient was discharged to the ward. No assigned patient was dropped out of the study. The patients were randomly divided equally to two groups viz. FPM and KM. The patients’ characteristics data between the two groups were comparable [Table 1].

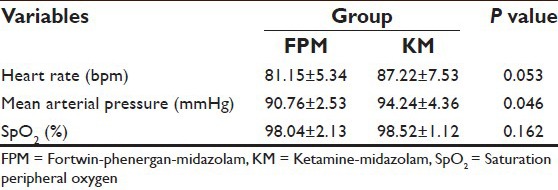

Table 1.

Patient characteristics data (mean±SD and P value)

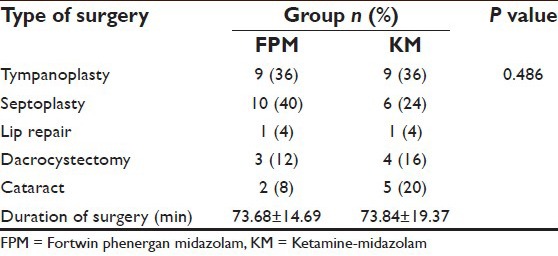

Both groups were comparable regarding demographic characteristics [Table 1], baseline values of HR, MAP, SpO2 [Table 2] and type and duration of surgery [Table 3].

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline vital signs in both groups

Table 3.

Comparison of type and duration of surgery in both groups

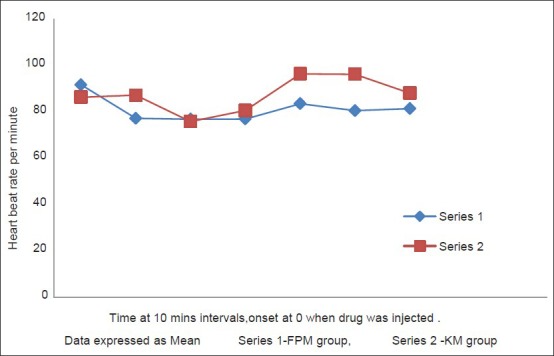

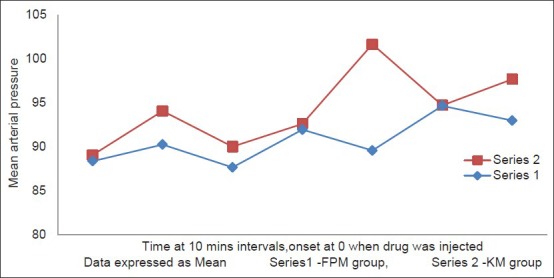

There was no difference in baseline measurements of HR and MAP between the two groups [Table 2]. Group KM had significant rise in HR (20-25%) and MAP (25-30%) after 30 min of the bolus dose given which continued until the end of the surgery. In contrast, Group FPM had no significant change of HR and MAP from baseline until the end of surgery [Figure 1 shows data for 60 min]. Intergroup comparison of HR and MAP at similar time intervals showed difference between the two groups, more after the 30th min of bolus dose, subsequent to which group FPM had no significant change, in comparison to the KM group [Figure 2 shows data for 60 min] until the end of surgery.

Figure 1.

Changes in heart rate over 60 min

Figure 2.

Changes in mean arterial pressure over 60 min

Saturation peripheral oxygen were comparable and within normal limits in both groups except for one patient of desaturation in the FPM group 10 min after the loading dose. The target sedation level (RSS ≥ 3) was achieved by higher number of patients in Group FPM (n = 23 [92%]) as compared with Group KM (n = 12 [48%]) [Table 4]. Time until need for rescue sedation was 66.96 ± 17.19 min in FPM and 32.80 ± 8.90 min in KM group, which shows that the former group gives more sedative and analgesic period than the latter group without any rescue top up dose. The requirement of rescue drugs when RSS <3, were significantly less in patients of FPM group which was 8% (n = 2) for midazolam and 12% (n = 3) for tramadol in contrast to 44% (n = 11) and 72% (n = 18), respectively in KM group. To achieve target sedation score, rescue midazolam required was 1 dose in 1 patient and 2 doses in another, whereas rescue tramadol needed was 1 dose in 1 patient and 2 doses in 2 patients in the FPM group. But in KM group, the rescue top up required for midazolam was 2 doses in 5 and 3 doses in 6 patients and tramadol top up required was 1 dose in 7, 2 doses in 9 and 3 doses in 2 patients. As per the patient satisfaction (Likert scale) is concerned, the result shows that, it is more with the FPM group (6.12 ± 0.83 vs. 4.40 ± 1.20). One patient in Group FPM developed hypotension and bradycardia after completing the loading dose which was successfully treated with IV atropine 0.6 mg and IV mephentermine sulfate 6 mg. There was one episode of desaturation in FPM group and treated with oxygenation. Three patients in KM group had an episode of hypertension which was treated with propofol 100 mg IV.

Table 4.

Comparison of sedation score and requirement of rescue sedative and analgesic in both groups

DISCUSSION

Monitored anesthesia care is a technique of combining local anesthesia with parenteral drugs for sedation and analgesia.[11] Midazolam, propofol, ketamine and sevoflurane are the most frequently used agents, and all have a quick onset of action and rapid recovery.[12] We used midazolam with fortwin plus phenergan/ketamine. Midazolam is the most frequently used sedative and has been reported to be well tolerated when used in MAC.[13,14] Midazolam got the approval by Food and Drug Administration in 1985.[15] Midazolam causes sedation by GABA receptor activation.[16] Midazolam is a benzodiazepine which has sedative and anxiolytic activities, provides anterograde amnesia, and thus reduces pain perception.[17] Its anxiolytic effect could reduce the emotional component of pain. As anxiety and pain are intimately related, anxiety leads to an exacerbation of pain.[18] Pain during surgery may lead to sympathetic stimulation and a restless patient may have tachycardia and hypertension, leading to increased bleeding in the surgical field.[19,20] Fortwin (pentazocine) is a benzomorphan derivative that possesses opioid agonist as well as weak antagonist actions. The opioid-benzodiazepine combination displays marked synergism in producing hypnosis. Using combination of two agents can provide better patient control and allows the use of smaller doses of each single agent avoiding its undesirable effects.[21]

Phenergan (promethazine) is used as a sedative and hypnotic during anesthesia and as a premedication for anesthesia. It helps to prevent nausea/vomiting and adds a bit of mild sedation with pentazocine. Sarmento, et al.,[22] achieved MAC with IV midazolam (0.03 mg/kg) at the beginning of surgery and 50 mg of intramuscular promethazine 1 h before surgery which (latter 1) is a higher dose than what we had used. Ketamine is a phencyclidine derivative. In sub anesthetic doses (0.25-0.75 mg/kg) it possesses analgesic properties.[23] This study by White[23] can be a comparative one though the dose 0.75 mg/kg was higher than what we had used. Mester et al.,[24] during cardiac catheterization, initiated sedation with dexmedetomidine and a bolus dose of ketamine (2 mg/kg). This dose is much higher than that of ours. The major problem with Ketamine is that it produces psychomimetic effect as hallucination, delusion, agitation that may be associated with postoperative dysphoria, which is attenuated by co-administration of benzodiazepine.[25] Parikh et al.[26] tried MAC with a combination of midazolam 0.06 mg/kg plus IV fentanyl 1 μg/kg versus dexmedetomidine. Kumari et al.,[27] compared midazolam 0.02 mg/kg versus clonidine in MAC during ENT surgery whereas we studied midazolam 0.04 mg/kg with fortwin, phenergan versus ketamine. Mortero et al.,[28] used a mixture of propofol (33 ± 13 mg/kg/min) and ketamine (3.7 ± 1.5 mg/kg/min) for MAC, but our combination consisted of a lower dose of KM.

CONCLUSION

There was a better subjective patient satisfaction and hemodynamic stability with combinations of FPM than midazolam and ketamine in low doses, in patients undergoing shorter duration of surgeries under local anesthesia. Ketamine was accompanied by relative cardiovascular stimulation and delayed recovery room discharge because of hallucination side effects in some patients. Hence, we emphasize on the use of FPM combination in MAC where a patient can enjoy a satisfying and pain free experience.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Monitored Anesthesia Care (MAC) [Last updated on 2014 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.securews.bcbswny.com/web/content/dam/./prov_prot_70201.pdf .

- 2.Jennifer Heisler RN. Monitored anesthesia care (twilight sleep, light sedation) [Last updated on 2009 Jan 04]. Available from: http://surgery.about.com/od/glossaryofsurgicalterms/g/TwilightSleepGl.htm explained .

- 3.Ghisi D, Fanelli A, Tosi M, Nuzzi M, Fanelli G. Monitored anesthesia care. Minerva Anestesiol. 2005;71:533–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldrete JA, Kroulik D. A postanesthetic recovery score. Anesth Analg. 1970;49:924–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 25]. Available from: http://www.gifted.uconn.edu/siegle/research/./likert.html .

- 6.Schlager A, Luger TJ. Oxygen application by a nasal probe prevents hypoxia but not rebreathing of carbon dioxide in patients undergoing eye surgery under local anaesthesia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:399–402. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.4.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 24]. Available from: http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sedation .

- 8.Fedok FG, Ferraro RE, Kingsley CP, Fornadley JA. Operative times, postanesthesia recovery times, and complications during sinonasal surgery using general anesthesia and local anesthesia with sedation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:560–6. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.100495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldrete JA. The post-anesthesia recovery score revisited. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:89–91. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(94)00001-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yung MW. Local anaesthesia in middle ear surgery: Survey of patients and surgeons. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1996;21:404–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1996.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novak LC. ASA updates its position on monitored anesthesia care. ASA Newsl. 1998;62:12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gan TJ. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of medications used for moderate sedation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45:855–69. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200645090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danielsen A, Gravningsbråten R, Olofsson J. Anaesthesia in endoscopic sinus surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260:481–6. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0613-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasen KV, Samartzis D, Casas LA, Mustoe TA. An outcome study comparing intravenous sedation with midazolam/fentanyl conscious sedation versus propofol infusion deep sedation for aesthetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1683–9. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000086363.34535.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leary WE. F.D.A. assailed on approval of drug. Special to the New York Times. 1988. May 6, Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/1988/05/06/us/fda-assailed-on-approval-of-drug.htm .

- 16.Mendelson WB. Neuropharmacology of sleep induction by benzodiazepines. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1992;6:221–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinbroum AA, Szold O, Ogorek D, Flaishon R. The midazolam-induced paradox phenomenon is reversible by flumazenil. Epidemiology, patient characteristics and review of the literature. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2001;18:789–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.2001.00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alhashemi JA. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for monitored anaesthesia care during cataract surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:722–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee WC, Kapur TR, Ramsden WN. Local and regional anesthesia for functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:767–9. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irwin MG, Campbell RC, Lun TS, Yang JC. Patient maintained alfentanil target-controlled infusion for analgesia during extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Can J Anaesth. 1996;43:919–24. doi: 10.1007/BF03011805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey PL, Pace NL, Ashburn MA, Moll JW, East KA, Stanley TH. Frequent hypoxemia and apnea after sedation with midazolam and fentanyl. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:826–30. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199011000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarmento KM, Jr, Tomita S. Retroauricular tympanoplasty and tympanomastoidectomy under local anesthesia and sedation. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129:726–8. doi: 10.1080/00016480802398996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White PF. Use of ketamine for sedation and analgesia during injection of local anesthetics. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;15:53. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mester R, Easley RB, Brady KM, Chilson K, Tobias JD. Monitored anesthesia care with a combination of ketamine and dexmedetomidine during cardiac catheterization. Am J Ther. 2008;15:24–30. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3180a72255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woolf CJ. Recent advances in the pathophysiology of acute pain. Br J Anaesth. 1989;63:139–46. doi: 10.1093/bja/63.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parikh DA, Kolli SN, Karnik HS, Lele SS, Tendolkar BA. A prospective randomized double-blind study comparing dexmedetomidine vs. combination of midazolam-fentanyl for tympanoplasty surgery under monitored anesthesia care. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:173–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.111671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumari I, Naithni U, Bedi V, Gupta S, Gupta R, Bhuie Comparison of clonidine versus midazolam in monitored anesthesia care during ENT surgery - A prospective, double blind, randomized clinical study. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2012;16:157–64. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mortero RF, Clark LD, Tolan MM, Metz RJ, Tsueda K, Sheppard RA. The effects of small-dose ketamine on propofol sedation: Respiration, postoperative mood, perception, cognition, and pain. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1465–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200106000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]