Abstract

Background:

Cesarean section (CS) is the one of the most common surgical procedure in women. There is preoperative stress effect before the delivery of the baby as (intubation and skin incision). There is acute postoperative pain, which may be progressed to chronic pain. All these perioperative stress effects need for various approach of treatment, which including systemic and neuraxial analgesia. The different analgesia modalities may affect and impair early interaction between mother and infant. Preemptive intravenous (I.V.) paracetamol (before induction) may reduce stress response before the delivery of the baby, intraoperative opioids and postoperative pain.

Objectives:

The aim of this study to compare between the administration of I.V. paracetamol as: Preemptive analgesia (preoperative) and preventive analgesia (at the end of surgery) as regards of hemodynamic, pain control, duration of analgesia, cumulative doses of intraoperative opioids and their related side-effects and to compare between two different protocols of postoperative analgesia and their cumulative doses.

Patients and Methods:

Sixty patients undergoing elective CS were randomly enrolled in this study and divided into two groups of 30 patients each. Group I: i.V. paracetamol 1 g (100 ml) was given 30 min before induction of anesthesia. Group II: i.V. paracetamol 1 g (100 ml) was given 30 min before the end of surgery. Heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and peripheral oxygen saturation were recorded. Postoperative pain was assessed by visual analog score. Postoperative pethidine was given by two different protocols: group I: 0.5 mg/kg was divided into 0.25 mg/kg intramuscular and 0.25 mg/kg I.V. Group II was given pethidine 0.5 mg/kg I.V. Doses of intraoperative fentanyl, postoperative pethidine, duration of paracetamol analgesic time, time to next analgesia, and side-effects of opioid were noted and compared.

Result:

Preemptive group had hemodynamic stability, especially before delivery of the baby P < 0.001. Preventive group had longer duration of paracetamol analgesia and higher intraoperative opioid P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively. Preemptive group had longer time for next analgesia and lower incidences of postoperative side-effects P < 0.001 and P < 0.05. Preemptive group had higher pain scores in immediate postoperative and after 6 h but preventive group had higher pain scores in 4 and 8 h postoperatively P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively.

Conclusion:

Preemptive paracetamol and immediate postoperative opioid analgesia were more effective than preventive paracetamol.

Keywords: Cesarean section, paracetamol, preemptive analgesia, preventive analgesia

INTRODUCTION

Systemic opioid either intra- or post-operatively had potential serious adverse reactions or had risks for neonate and they act on opioid center in central nervous system.[1] Paracetamol is devoid of risks related to opioid and acts at both central and peripheral points of the pain pathway, by direct inhibition of N-methyl-D-Aspartate receptors and inhibition of the cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) pathway.[2] Preventive analgesia term described any intraoperative analgesic agents able to control pain-induced sensitization of the central nervous system. Preemptive analgesia had been defined as an antinociceptive treatment starting before surgery that prevents establishment of altered central afferent input from injuries and its goal is to decrease pain by timing the analgesic's peak pharmacodynamic effect with anticipated onset of pain or peak pain response.[3] The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of intravenous (I.V.) paracetamol as preemptive or preventive analgesia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A prospective, randomized, and unblinded study was carried out in King Abdul-Aziz Hospital, Saudi Arabia; January 2013 to January 2014. After the Medical Ethics Committee approval and the written informed consents were obtained from all patients. Pregnant women were scheduled for elective cesarean section (CS) for different causes under general anesthesia. The study enrolled 60 pregnant women were American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I and II, aged 18-39 years. We excluded patients had ASA physical status III and IV, allergy to any drug used in the study, preeclampsia, cardiovascular, respiratory, hepatic or renal problems, history of sedative, narcotic or analgesic drugs, morbid obese, seizures or any psychological disorders. Patients were fasted for 6-8 h. No patients received premedication. Patients were randomly allocated according to randomization list by ratio (1:1). In receiving area: Anticubital venous access was secured by 18 gauge I.V. cannula, ringer lactate drip was started by 8 ml/kg/h, and basal heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded for all patients. Group I patients received I.V. paracetamol 1 g (100 ml) (Perfalgan Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Italy) was given over 15-20 min, 30 min before induction of anesthesia as preemptive analgesia. Group II patients did not receive anything except I.V. fluid in the receiving area. In the operating room, standard monitoring with noninvasive arterial pressure electrocardiography and pulse-oximetry was established. After administration of oxygen, anesthesia was induced in both groups with I.V. propofol (2 mg/kg) and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg), after intermittent positive pressure ventilation; airway was secured with appropriate sized cuffed endotracheal tube. Anesthesia was maintained by 0.8-1% sevoflurane in nitrous oxide and oxygen (ratio 1:1). No opioid was given before delivery of the baby. HR, SBP, DBP, and SpO2 were recorded after induction, after intubation, after skin incision and every 5 min until delivery of the baby and every 15 min during the procedure and immediately on arrival recovery unit and on 1 h and 2 h. After delivery of the baby fentanyl 1-2 μg/kg was given for all patients in both groups. Fentanyl (Janssen-Cilag, Belgium) was repeated in the dose 1 μg/kg intraoperatively if both HR and NIBP increased >20% from the baseline despite maintaining adequate depth of anesthesia. Total cumulative doses of intraoperative fentanyl were recorded in both groups. At the end of surgery, group II patients received I.V. paracetamol 1 g (100 ml) over 15-20 min, 30 min before the end of procedure as preventive analgesia. The residual neuromuscular blocked was reversed with I.V. neostigmine 2.5 mg and glycopyrrolate 5 mg. Oral suction and tracheal extubation were performed after onset of spontaneous breathing and adequate motor power judged by head lift for 5 s. The assessment of pain by visual analog score (VAS) was stared in immediate postoperative period when the patients were fully oriented and conscious enough to answer any questions and before shifting her to recovery unit. The patients were given rescue analgesia when they themselves complained for pain and their VAS was ≥7/10. Pethidine 1 mg/kg I.V. bolus was considered as rescue analgesia. These patients were excluded from further comparison in the study. Postoperative pain relief in the study was given when VAS was ≥3/10 and <7/10. The postoperative analgesia was given routinely in immediate postoperative period according to VAS and by two different protocols to be as multimodal analgesia with both preemptive and preventive analgesia by I.V. paracetamol: Group I: Pethidine 0.5 mg/kg was divided into: 0.25 mg/kg intramuscular (I.M.) and 0.25 mg/kg I.V. Group II: Received pethidine 0.5 mg/kg I.V. The duration of paracetamol analgesia recorded from its administration time till time of the first postoperative analgesic drug. Time of second analgesic drug given was recorded to evaluate the efficacy of two different protocols of postoperative analgesic drug. VAS was recorded in recovery unit 1 h, and 2 h, and also 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, and 12 h in surgical ward. Total cumulative doses of pethidine were recorded. Opioids side-effects as postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), respiratory depression or apnea, urine retention, and drowsiness were recorded and treated accordingly. PONV was considered when two or more episodes of nausea and vomiting, and treated by ondansetron 4 mg I.V. Apnea was defined as not having a spontaneous breathing for at least 20 s and decrease SpO2 <92% with oxygen administration and both were treated by support airway and/or assisted ventilation. Urine retention was defined inability to void after removal of urinary catheter. Drowsiness was defined inability to awake the patients by sounds or tactile stimulations.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 30 patients by group was calculated to detect a significant difference of 20% or more in intraoperative opioid consumption with a power of 100% two-tailed and a significant level of 5% (alpha of 0.05) corresponding to level of confidence 95%. Data were reported as mean ± SD and counts (numbers). Statistical assessment included analysis of Student's t-test for continuous data and VAS pain data. Fisher's exact t-test was used to analyze nominal data. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant for all tests. All analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software, version 15 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

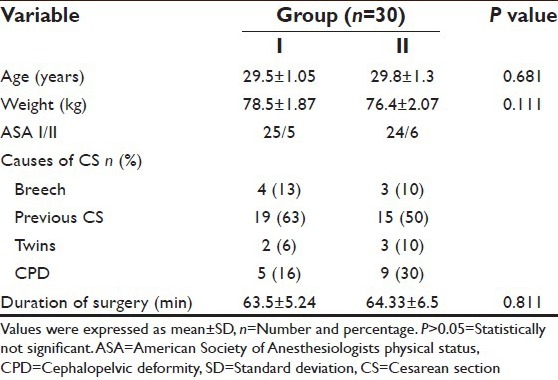

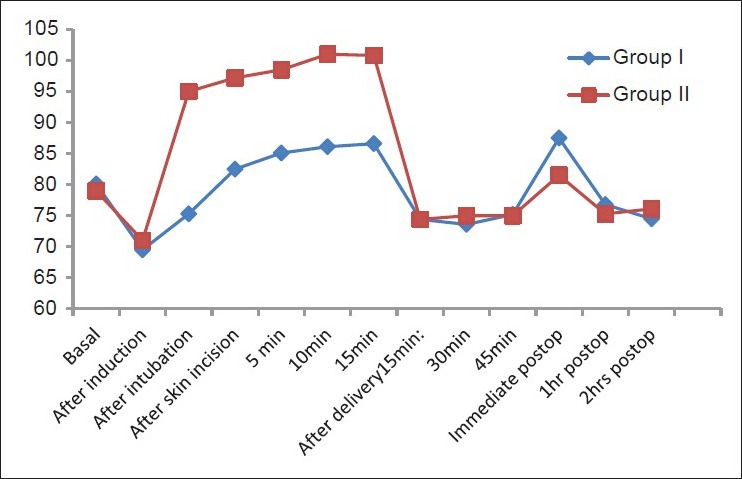

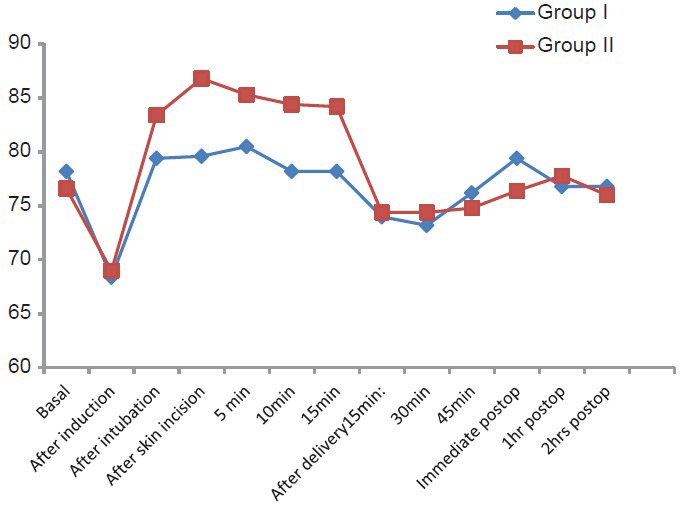

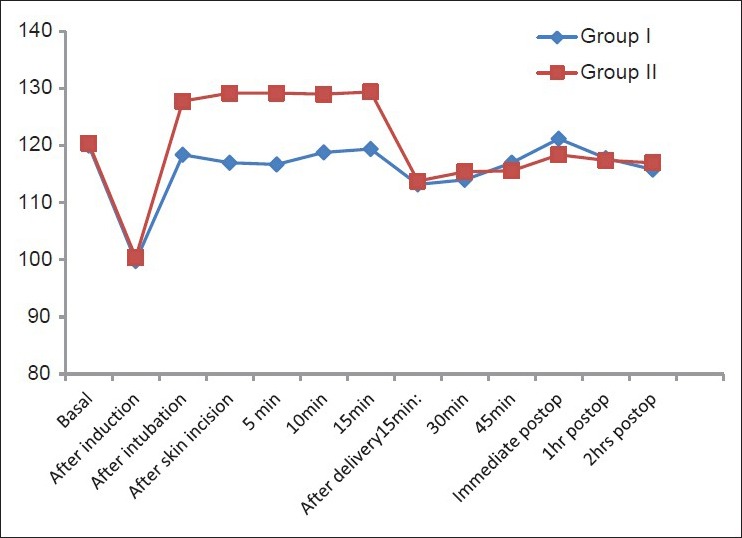

There were no significant differences between both groups as regards age, weight, ASA physical status, causes of CS, and duration of surgery [Table 1]. There were extreme significant higher HR, SBP, and DBP in patients of group II than group I from intubation time till delivery of the baby (P < 0.001) but Group I showed higher HR, SBP, and DBP than Group II immediately postoperative with extreme statistically significant difference (P < 0.001). There were no statistically differences between both groups as regards HR, SBP, and DBP preoperative, after induction, intraoperative (after delivery of baby) and 1 h and 2 h postoperative (P > 0.05) [Figures 1–3].

Table 1.

Demographic data

Figure 1.

Changes of heart rate between both groups

Figure 3.

Changes of diastolic blood pressure in both groups

Figure 2.

Changes of systolic blood pressure in both groups

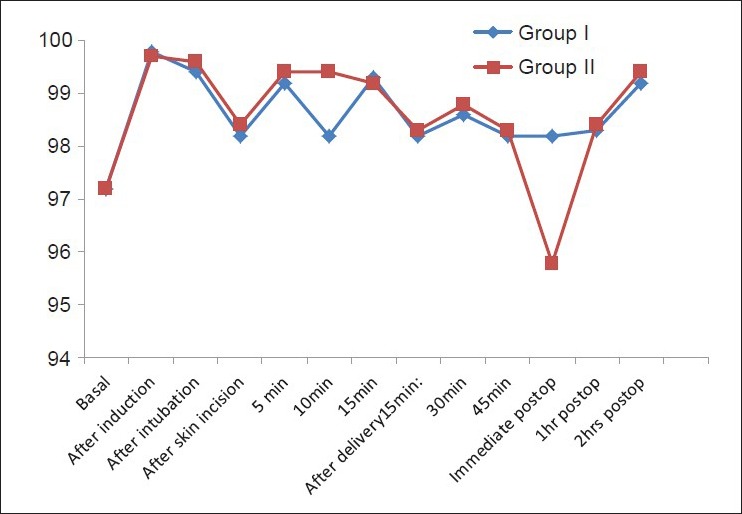

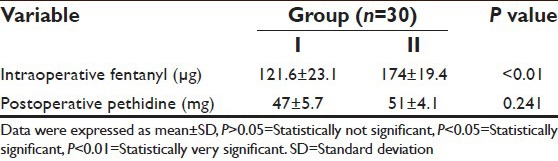

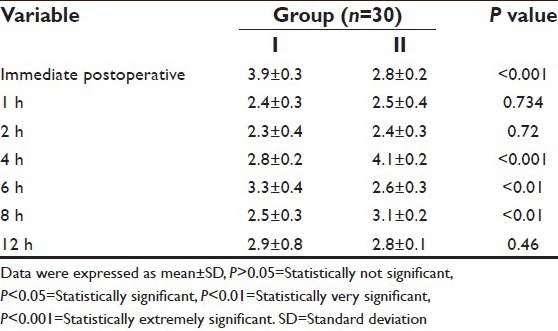

Group II showed lower SpO2 than Group I immediately postoperative (95.8 and 98.2) respectively with high significant (P < 0.01). There were no statistically significant differences as regards SpO2 in preoperative, intraoperative and 1 h and 2 h postoperative (P > 0.05) [Figure 4]. Intraoperative cumulative doses of fentanyl were higher statistically significant in Group II than in group I (174 ± 19.9 and 121.67 ± 23.17) P < 0.01 [Table 2]. Group I patients had extremely higher and higher significant pain scores than patients in Group II (3.9 ± 0.3 and 3.3 ± 0.4 vs. 2.8 ± 0.2 and 2.6 ± 0.3) immediately and after 6 h postoperative P < 0.001 and P < 0.01. There were statistically extreme significant and significant differences as regard pain scores in Group II more than Group I (4.1 ± 0.2 and 3.1 ± 0.2 vs. 2.8 ± 0.2 and 2.5 ± 0.3) in 4 h and 8 h postoperative, respectively P < 0.001 and P < 0.012 [Table 3]. There was no significant difference between both groups as regards postoperative cumulative doses of pethidine P > 0.05 [Table 2].

Figure 4.

Changes of oxygen saturation in both groups

Table 2.

Cumulative doses of opioids

Table 3.

Postoperative pain scores

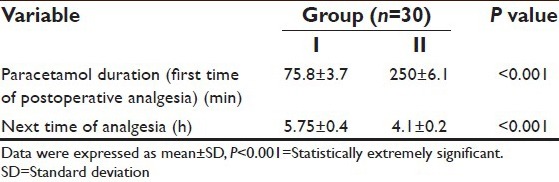

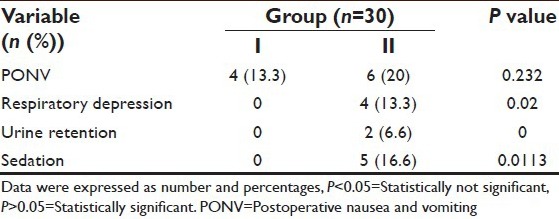

Paracetamol analgesia duration was extremely statistically significant longer in Group II than Group I (250 ± 6.1 min vs. 75.8 ± 3.7 min) P < 0.001 and time of next postoperative analgesia was extremely statistically significant longer in Group I than in Group II (5.75 ± 0.4 h vs. 4.1 ± 0.2 h) P < 0.001 [Table 4]. Group II patients showed more statistically significant complications of opioids than patients in Group I P = 0.02, 0, and 0.011; (13.3%, 6.6% and 16.6% vs. no complications) as regards respiratory depression, urine retention, and sedation respectively and nonsignificant as regards PONV P > 0.05 [Table 5]. There were no patients in both groups received rescue postoperative analgesia.

Table 4.

Analgesia duration and its time

Table 5.

Complications of opioids

DISCUSSION

Patients undergoing CS experience severe to moderate postoperative pain. Pain after CS may impair the ability of mother to care and feed her child, early ambulation, and discharge. Chronic pain is uncommon complication after CS delivery. About 12.3% of patients experience pain scores enough to affect infant care up to 6 months after CS.[4]

Improper pain control during the perioperative period leads to complications, which affecting the outcome of the patients. Pain relief is very important to the patient as it causes discomfort which affects hemodynamic intraoperative and increases the risk of postoperative complications as atelectasis ineffective coughing and inadequate ventilation. Proper pain control is essential not only intraoperatively, but also in immediate postoperative periods to cover long time period postoperatively. The major role of intra- or post-operative management of pain is reducing the dose of medication to lessen side-effects, while providing adequate analgesia. This role is best accomplished with multimodal and preemptive analgesia.[5] In our study, we used I.V. paracetamol 1 g either preoperative analgesia as a preemptive or as a preventive analgesia at the end of the procedure associated with intra- and post-operative opioids analgesia was considered as multimodal analgesia with different mechanism of actions. We assessed their effects on intraoperative hemodynamic, and analgesia requirements and postoperative analgesic effectiveness, analgesia requirements, duration of analgesia, and the incidences of side-effects. Our study showed that I.V. paracetamol when used as preemptive analgesia before induction by 30 min had significant control of hemodynamic changes before delivery of the baby. It showed more significant reductions of HR, SBP, and DBP when compared with preventive analgesia by paracetamol 30 min before the end of procedure with agreement of Arici et al.,[6] they found decreasing in mean values of HR, SBP, and DBP, intraoperatively after paracetamol administration. Pulse rate and blood pressure were almost equal to baseline values in Group I, they were increased in Group II due to analgesic effect of paracetamol preoperatively with disagreement of Atashkhoy et al.,[7] they suggested that measurement of blood pressure and HR did not affected by 1 g paracetamol, but higher doses as 2 g exhibited stronger nonselective COX inhibitor activity and thereby reducing blood pressure. There were no significant differences after delivery of the baby between both groups as regards HR, SBP, and DBP due to the effect of intraoperative fentanyl. Total doses of intraoperative fentanyl were significant higher in Group II than in Group I. slight increasing in HR, SBP, and DBP immediately postoperative in Group I due to slight pain score <4/10, which was covered by postoperative analgesia by pethidine I.V. and I.M. There were no significant differences between both groups as regards perioperative SpO2 except immediately postoperative in Group II (95%) due to effect of intraoperative fentanyl, which was more in Group II. Desaturation did not need any intervention or treatment, but only air way supports with oxygen similar as in previous study.[6] In our study, the postoperative pain assessment showed increased pain score immediately postoperative on table and before shifting the patient to recovery room in preemptive group which 3.9/10 versus 2.8/10 due to lower intraoperative fentanyl dose and duration of paracetamol was shorter than Group II (75.8 min vs. 250 min), but it was covered by small dose of postoperative analgesia properly with agreement of few studies as in Sinatra et al.,[8] they found reduction in postoperative pain scores after preventive paracetamol in major surgeries and with agreement of Anirban and Rajeef,[9] and Atashkhoy et al.,[7] they found that duration of paracetamol analgesia as a preemptive was 76 min and duration of preventive paracetamol was 265 min, respectively. In our results, no patients were excluded from the study due to high pain scores. In the preventive group patients started to complain pain in 4 h and 8 h postoperative due to longer duration of paracetamol and high doses of intraoperative fentanyl.[10] However, next time of analgesia was earlier than Group II (4.1 h vs. 5.7 h) with agreement Pratyush et al.,[11] they found the mean duration of postoperative analgesia in preemptive group of paracetamol was 4.2 h. Our results showed that lower doses of intra- and post-operative opioids in the preemptive group with agreement of Moon et al.,[12] they found the preoperative paracetamol in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy reduced opioid consumption and opioid related side-effects. The incidences of side-effects of opioids were more in Group II than in Group I due to two reasons: First; there were higher doses of intraoperative opioids in Group II. The second; the route of postoperative pethidine was I.V. in Group II and it was I.M. and I.V. in Group I that lead to reduce the side-effects and to maintain the analgesia duration to be extended up to 6 h in Group I.[13] Six patients were complained from PONV in Group II versus four patients in Group I, but there was any patient complained from respiratory depression or apnea, urine retention or drowsiness in Group I.[14] Patients in Group II were complained respiratory depression (four patients), but no apnea or serious intervention and two patients suffered from urine retention after removal of urinary catheter, but it was mild. There were five patients complained drowsiness (sedation score 1) and were easily arousable only by sounds with disagreement Cok et al.,[15] who found that intraoperative (preventive) paracetamol reduced PONV. Our study reported that I.V. paracetamol when used as preemptive 30 min before induction (before a pain stimulus as surgical incision) as part of multimodal analgesic regime (when associated with another type of analgesia as opioids) had significant reduction of subsequent pain and opioid sparing effect.[16] paracetamol is an attractive component of multimodal analgesic treatment plan because of its efficacy, safety, lack of clinically significant drug interactions and lack of the adverse effects associated with other analgesics. The differences in mechanisms of action between paracetamol and opioids are likely responsible not only the synergistic effect they have when used in combination, but also for the differences in safety profiles observed with the drugs.[3] Our study was one of few studies compared between preemptive and preventive paracetamol in elective CS to evaluate the effect of preemptive paracetamol on hemodynamic before delivery of baby with positive results to control hemodynamic during this stressful period. Our study used balanced regimen of postoperative analgesia with preemptive paracetamol by reducing the doses of pethidine postoperative that helping reducing of opioid related side-effects and prolonged the duration of next analgesia recalling. Our study demonstrated the additive effect of combing I.V. paracetamol as preemptive with intra- and post-operative opioids resulting in decreased opioid amount and in improved pain relief. The different sites of action of these drugs in the nervous system may be the cause of better pain relief. The complimentary analgesic actions of the two drugs make them an important component of multimodal pain therapy. The however, our study had a few limitations; it was not a blind because we liked to administer two different protocols of postoperative pethidine to evaluate it with the preemptive and preventive paracetamol. The power of the study due to different reasons (from weakness of previous studies): First, we estimated the analgesia duration of paracetamol either preemptive or preventive. Second; we estimated the particular postoperative analgesia (pethidine) in both groups and by two different protocols. Third; we reported the time of first analgesia and next time of analgesia needed. Finally, we followed-up the patients in ward for 12 h to evaluate the side-effects related to opioids.

CONCLUSION

We concluded that both preventive and preemptive paracetamol were effective in pain relief during anesthetic management of elective CS. Preemptive paracetamol had better control of hemodynamic in the most stressful period before delivery of the baby, lower doses of intra- and post-operative opioids, and longer duration of next analgesia needed. Preventive paracetamol had longer duration of paracetamol analgesia and longer time for first analgesia needed. Divided low doses pethidine gave by I.V. and I.M. postoperatively with preemptive paracetamol provided low incidences of side-effects related opioids, longer time for next analgesia, and effective multimodal analgesia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank all members of Anesthesia Department in my Hospital.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dieterich M, Müller-Jordan K, Stubert J, Kundt G, Wagner K, Gerber B. Pain management after cesarean: A randomized controlled trial of oxycodone versus intravenous piritramide. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286:859–65. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duggan ST, Scott LJ. Intravenous paracetamol (acetaminophen) Drugs. 2009;69:101–13. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen X, Wang F, Xu S, Ma L, Liu Y, Feng S, et al. Comparison of the analgesic efficacy of preemptive and preventive tramadol after lumpectomy. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60:415–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore A, Costello J, Wieczorek P, Shah V, Taddio A, Carvalho JC. Gabapentin improves postcesarean delivery pain management: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:167–73. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181fdf5ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ong CK, Lirk P, Seymour RA, Jenkins BJ. The efficacy of preemptive analgesia for acute postoperative pain management: A meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:757–73. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000144428.98767.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arici S, Gurbet A, Türker G, Yavascaoglu B, Sahin S. Preemptive analgesic effects of intravenous paracetamol in total abdominal hysterectomy. Agri. 2009;21:54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atashkhoy S, Rasouli S, Fardiazar Z, Ghojazadeh M, Marandi P. Preventive analgesia with intravenous paracetamol for post-cesarean section pain control. Int J Women's Health Reprod Sci. 2014;2:132–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinatra RS, Jahr JS, Reynolds LW, Viscusi ER, Groudine SB, Payen-Champenois C. Efficacy and safety of single and repeated administration of 1 gram intravenous acetaminophen injection (paracetamol) for pain management after major orthopedic surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:822–31. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200504000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anirban HC, Rajeef U. Comparison between intravenous paracetamol plus fentanyl and intravenous fentanyl alone for postoperative analgesia during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Essays Res. 2011;5:196–200. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.94777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wininger SJ, Miller H, Minkowitz HS, Royal MA, Ang RY, Breitmeyer JB, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, repeat-dose study of two intravenous acetaminophen dosing regimens for the treatment of pain after abdominal laparoscopic surgery. Clin Ther. 2010;32:2348–69. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pratyush G, Sandeep K, Neha G, Ankit K, Shashi K. Preemptive analgesia with I.V. paracetamol and I.V. diclofenac sodium in patients undergoing various surgical procedures: A comparative study. Int J Biol Med Res. 2013;4:3294–300. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moon YE, Lee YK, Lee J, Moon DE. The effects of preoperative intravenous acetaminophen in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:1455–60. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-1860-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maund E, McDaid C, Rice S, Wright K, Jenkins B, Woolacott N. Paracetamol and selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the reduction in morphine-related side-effects after major surgery: A systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:292–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cakan T, Inan N, Culhaoglu S, Bakkal K, Basar H. Intravenous paracetamol improves the quality of postoperative analgesia but does not decrease narcotic requirements. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2008;20:169–73. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181705cfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cok OY, Eker HE, Pelit A, Canturk S, Akin S, Aribogan A, et al. The effect of paracetamol on postoperative nausea and vomiting during the first 24 h after strabismus surgery: A prospective, randomised, double-blind study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:836–41. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32834c580b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fayaz MK, Abel RJ, Pugh SC, Hall JE, Djaiani G, Mecklenburgh JS. Opioid-sparing effects of diclofenac and paracetamol lead to improved outcomes after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;18:742–7. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]