Abstract

Background and purpose —

Hip dysplasia can be treated with periacetabular osteotomy (PAO). We compared joint angles and joint moments during walking and running in young adults with hip dysplasia prior to and 6 and 12 months after PAO with those in healthy controls.

Patients and methods —

Joint kinematics and kinetics were recorded using a 3-D motion capture system. The pre- and postoperative gait characteristics quantified as the peak hip extension angle and the peak joint moment of hip flexion were compared in 23 patients with hip dysplasia (18–53 years old). Similarly, the gait patterns of the patients were compared with those of 32 controls (18–54 years old).

Results —

During walking, the peak hip extension angle and the peak hip flexion moment were significantly smaller at baseline in the patients than in the healthy controls. The peak hip flexion moment increased 6 and 12 months after PAO relative to baseline during walking, and 6 months after PAO relative to baseline during running. For running, the improvement did not reach statistical significance at 12 months. In addition, the peak hip extension angle during walking increased 12 months after PAO, though not statistically significantly. There were no statistically significant differences in peak hip extension angle and peak hip flexion moment between the patients and the healthy controls after 12 months.

Interpretation —

Walking and running characteristics improved after PAO in patients with symptomatic hip dysplasia, although gait modifications were still present 12 months postoperatively.

In developmental hip dysplasia, the acetabulum is shallow and oblique with insufficient coverage of the femoral head (Klaue et al. 1991, Jacobsen et al. 2006, Nehme et al. 2009). Periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) reorientates the acetabulum through 3 separate osteotomies and corrects the insufficient coverage (Ganz et al. 1988, Leunig et al. 2011). The goal of the PAO is to reduce pain, improve function, and prevent osteoarthritis (Murphy et al. 1995, Steppacher et al. 2008, Troelsen et al. 2009). Pain reduces participation in sports activities involving walking and running (Nunley et al. 2011, Novais et al. 2013), and this is particularly problematic for young adults who represent the majority of the patients (Hartofilakidis et al. 2000).

The minimally invasive transsartorial approach for PAO was introduced in 2003 by Kjeld Søballe. The approach involves minor incision of the soft tissue and early mobilization (Troelsen et al. 2000). Radiological follow-up (Mechlenburg et al. 2007, 2009) and clinical follow-up (Troelsen et al. 2000) after minimally invasive PAO have been reported, but little is known about objective measures of physical function. Decreased hip flexion moment and reduced walking speed in patients undergoing PAO have been reported in 2 prospective studies (Pedersen et al. 2006, Sucato et al. 2010). In an earlier study, we reported reduced hip extension angle and decreased hip flexion moment during walking in patients with untreated hip dysplasia (Jacobsen et al. 2013). This was also described in 3 earlier studies evaluating untreated hip dysplasia (Romano et al. 1996, Pedersen et al. 2004, Sucato et al. 2010).

In the present study, we compared joint angles and joint moments during walking and running in adults with hip dysplasia—before, and 6 and 12 months after undergoing the minimally invasive approach for PAO—with those of healthy controls.

We hypothesized that the peak hip extension angle and the peak hip flexion moment would increase 6 and 12 months after PAO. We also hypothesized that there would be no significant differences between patients 12 months after PAO and healthy controls, in peak hip extension angle and peak hip flexion moment.

Patients and methods

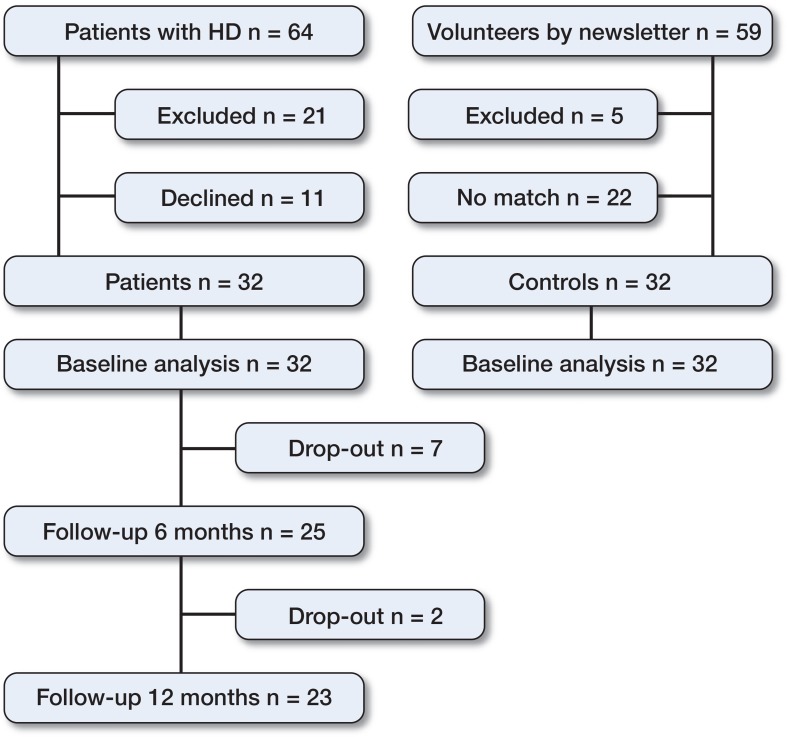

32 patients (26 women) with unilateral or bilateral hip dysplasia were included consecutively at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark (24 patients had bilateral dysplasia). Parallel to the inclusion of patients, a control group of 32 controls (26 women) with no hip, knee, ankle or back problems were included (Figure 1). The median age of the patients was 34 (18–53) years and the median age of the controls was 33 (18–54) years. The mean BMI of both groups was 22. Inclusion and collection of baseline characteristics have been described previously (Jacobsen et al. 2013). Briefly, baseline characteristics were registered using standardized questions prior to PAO. Walking and running characteristics of the lower extremities were recorded before PAO, and at 5.9 (SD 0.9) months and 12.7 (SD 1.1) months after PAO. In addition, the hip and groin outcome score (HAGOS) (Thorborg et al. 2011) and the 100-mm visual analog pain scale (VAS pain) were completed at the same time as the walking and running analysis. Wibergs center-edge (CE) angle (Cooperman et al. 1983), Tönnis’ acetabular index (AI) angle (Tönnis 1987), and osteoarthritis grade were measured on anteroposterior radiographs before and after PAO. In the healthy controls, all outcome measures were recorded at baseline only and no clinical and radiographic examinations were conducted.

Figure 1.

32 patients with hip dysplasia were included from March 1, 2011 to December 1, 2011.

Periacetabular osteotomy

The minimally invasive approach used has already been described (Troelsen et al. 2000).

Patients undergoing PAO were hospitalized for a median of 3 days, and for the first 6–8 weeks the patients were allowed to perform partial weight bearing with a maximum load of 30 kg. During hospitalization, they were introduced to a standardized rehabilitation program. After 6–8 weeks, they started to walk with full weight bearing. In addition, the patients underwent physiotherapist-supervised training twice a week, starting 6 weeks after surgery and continuing until 2.6 (SD 11) months postoperatively. The rehabilitation program focused on strength and stability training and normalization of walking.

Walking and running analysis

Primary outcomes of this study were the peak hip flexion moment during the second half of the stance phase and the peak hip extension angle during stance. Hip flexor muscles form the joint moment of hip flexion together with the joint capsule and the strong capsule ligaments at the end of the stance phase, where the leg is in maximal hip extension. In this position, maximal tension is put on the passive and active structures on the frontal side of the hip, which is the area of pain in hip dysplasia (Klaue et al. 1991, Nunley et al. 2011). Previous studies have found reduced hip extension and hip flexion moment during walking (Romanó et al. 1996, Pedersen et al. 2004, Pedersen et al. 2006), and these particular outcomes were therefore extracted for our analysis. The experimental set-up has already been described (Jacobsen et al. 2013).

The motion capture analysis was performed at the Department of Sports Science, Aarhus University. The participants walked and ran at self-selected speeds along an 8-m walkway. Kinematic data were recorded at 240 Hz with an 8-camera ProReflex MCU 1000 motion capture system (Qalisys AB, Gothenburg, Sweden). Ground reaction forces were simultaneously sampled at 960 Hz using an OR6-7 AMTI force plate (Advanced Mechanical Technology, Watertown, MA). During walking and running, participants were equipped with 13 reflective markers (19 mm) on each limb according to the Visual3D conventional marker set guidelines (C-Motion Inc., Germantown, MD) (Cappozzo et al. 1997, Robertson et al. 2004). In addition to the recordings of walking and running, a static recording with 7 extra markers was made. Before testing, the participants rated pain at rest on a 100-mm VAS scale. After testing, they rated pain during activity.

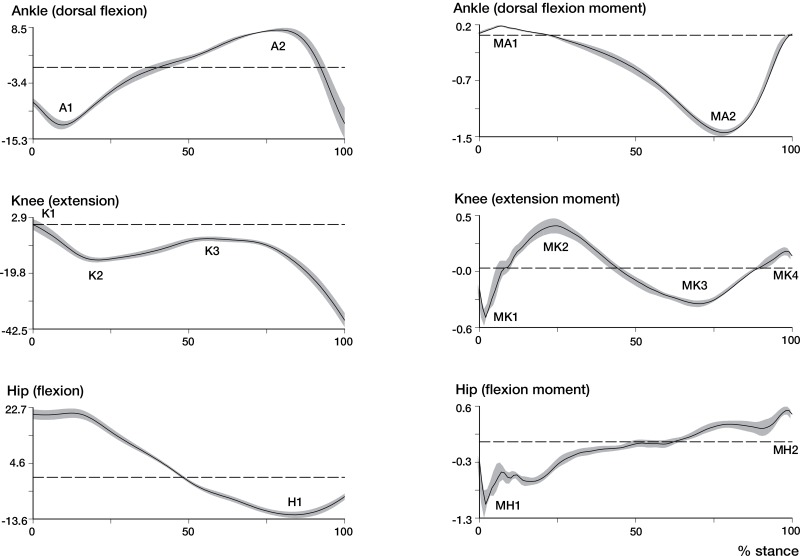

2-D marker position data from each of the 8 cameras were combined into a 3-D representation using Qualisys Tracking Manager software (Qualisys AB, Gothenburg, Sweden). The marker position and force plate data were then exported to Visual3D (C-Motion Inc., Germantown, MD) for further analysis, comprising filtering and inverse dynamics calculation resulting in sagittal joint angles and moments of the hip, knee, and ankle in the stance phase. To identify changes between the groups and at the different follow-ups, peak values of the joint angles and net joint moments were tested statistically. Peak joint angles were peak plantar flexion in the first half of the stance phase (A1) and peak dorsiflexion in the second half of the stance phase (A2). For the knee, the peak values were extension at heel strike (K1), peak flexion in the first half of the stance phase (K2), and peak extension in the second half of the stance phase (K3). For the hip, peak extension (H1) was used in the analysis. Peak joint moments for the ankle joint were peak dorsiflexion moment in the first half of the stance phase (MA1) and peak plantar flexion moment in the second half of the stance phase (MA2). For the knee, peak flexion (MK1) and extension (MK2) moments in the first half of the stance phase and peak flexion (MK3) and extension (MK4) moments in the second half of the stance phase were used. For the hip, peak extension moment in the first half of the stance phase (MH1) and peak flexion moment in the second half of the stance phase (MH2) were used. The extracted outcomes are illustrated in Figure 2. Right or left trials were selected for the statistical analysis based on the affected limb. The means of at least 3 right and 3 left dynamic trials were recorded, where the participant had to hit the force plate with the whole foot and where the walking speed was stable. In patients with bilateral involvement, the trials for the limb undergoing operation were selected. The corresponding trials for the controls were selected for analysis (i.e. involving the same limb).

Figure 2.

Mean values of peak joint angle (degrees) and peak joint moment (N*m/kg) during walking in the sagittal plane as a function of the stance phase (%).

Statistics

The distribution of the data was assessed with scatter plots and histograms. Normally distributed data are presented as mean (SD); otherwise, data are presented as median (range). Categorical data are presented as prevalence. Unpaired Student’s t-test was used to evaluate differences between the 2 groups and paired Student’s t-test was used to evaluate differences among the patients at baseline and at 6 and 12 months postoperatively. Differences between the groups are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and the peak hip extension angle and peak hip flexion moment (primary outcomes) are given with an alpha level of 0.05, but they were tested statistically at a level of 0.025 (Bonferroni correction).

Ethics

The study complied with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, and all the participants gave their consent to be included in the study. The Central Denmark Region Committees on Biomedical Research Ethics approved the study (M-20100206). Permission was granted by the Danish Data Protection Agency and the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01344421).

Results

7 patients declined to participate at the first follow-up; at the second follow-up, 2 more patients declined to participate. Of these, 3 patients agreed to fill out the HAGOS questionnaire and report their intake of analgesia at 6 months and at 12 months; 4 patients agreed to fill out the HAGOS questionnaire and report their intake of analgesia. Of the 9 patients who declined participation, 1 underwent a PAO on the contralateral limb and 3 patients underwent arthroscopy due to symptoms from the acetabular labrum. In addition, 1 patient became pregnant, 1 had a non-traumatic fracture of the inferior ramus of the pubis, and 1 had detachment of the superior anterior iliac spine during the study period.

23 patients completed the second follow-up. Between the first and second follow-up, 4 patients underwent a PAO on the contralateral limb (6.5 (5.5–7-5) months before examinations). 5 patients underwent a hip arthroscopy due to symptoms from the acetabular labrum, and 3 of these did not participate in the gait analysis after the surgery. The other 2 completed gait analysis 6.8 and 6.5 months after hip arthroscopy. 3 patients reported symptoms from the iliopsoas tendon, such as snapping hip and tendinitis.

Baseline characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics a of patients and controls

| Baseline Controls (n = 32) a | Preoperatively Patients (n = 28) a | 6 months Patients (n = 28) a | postoperatively p-value | Preoperatively Patients (n = 29) a | 12 months postoperatively Patients | postoperatively p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAGOS pain (0–100) | 100 (85–100) | 50 (20–95) | 79 (48–100) | < 0.001 | 50 (20–95) | 78 (20–100) | < 0.001 |

| HAGOS symptoms (0–100) | 96 (79–100) | 48 (21–96) | 68 (25–93) | < 0.001 | 50 (21–96) | 71 (25–93) | < 0.001 |

| HAGOS ADL (0–100) | 100 (85–100) | 53 (5–100) | 85 (35–100) | < 0.001 | 60 (5–100) | 90 (30–100) | < 0.001 |

| HAGOS sport/recreation (0–100) | 100 (84–100) | 38 (3–91) | 70 (16–91) | < 0.001 | 38 (3–91) | 63 (6–100) | < 0.001 |

| HAGOS participation (0–100) | 100 (50–100) | 25 (0–100) | 50 (0–100) | 0.05 | 25 (0–100) | 50 (0–100) | 0.02 |

| HAGOS quality of life (0–100) | 100 (75–100) | 38 (0–80) | 55 (0–90) | 0.001 | 40 (0–80) | 65 (10–100) | < 0.001 |

| VAS score at rest, mm | 0 (0–11) | 11 (0–71) b | 0 (0–19) b | < 0.001 | 12 (0–71) c | 0 (0–41) c | 0.002 |

| VAS score during walking, mm | 0 (0–2) | 9 (0–83) b | 1 (0–21) b | 0.005 | 9 (0–83) c | 0 (0–49) c | 0.008 |

| VAS score during running, mm | 0 (0–8) | 19 (0–72 b | 5 (0–63) b | < 0.001 | 13 (0–72) c | 3 (0–54) c | 0.03 |

| Non-prescription analgesia, n | - | 5 | 1 | - | 5 | 1 | - |

| Prescription analgesia, n | - | 8 | 3 | - | 7 | 3 | - |

aBaseline characteristics are presented as median values (range) and as numbers for patients and healthy controls before and after PAO.

bn = 25.

cn = 23. Differences between the groups were tested with Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

HAGOS: The Copenhagen hip and groin outcome score; ADL: activities of daily living.

The center-edge (CE) angle achieved after the reorientation of the acetabulum was 33 (27–36) degrees and the acetabular index (AI) angle achieved was 1 (–1 to 5) degrees. Both angles improved from baseline to follow-up (p < 0.001). In all dimensions of HAGOS and VAS scores, improvements were apparent at both 6 months and 12 months after PAO relative to baseline (p < 0.05). At both 6- and 12-month follow-up, the patients reported lower HAGOS scores in all dimensions and higher VAS scores compared to the healthy controls (p < 0.001).

Walking and running analysis (Tables 2 and 3)

Table 2.

Peak joint angles in patients with hip dysplasia and in controls

| Baseline | Baseline | 6 months after PAO |

Baseline | 12 months after PAO |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n = 32) a | Patients (n = 25) a | Patients (n = 25) a | Difference (CI) | p-value | Patients (n = 23) a | Patients (n = 23) a | Difference (CI) | p-value | |

| Walk stance phase, s | 0.6 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 1.0 | 0.6 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.8 |

| Walk velocity, m/s | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.1) | 0.0 (-0.1 to 0.0) | 0.1 | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | 0.0 (-0.1 to 0.0) | 0.2 |

| Peak joint angles in walking, degrees | |||||||||

| Ankle | |||||||||

| A1 | -9.6 (2.4) | -8.5 (1.9) | -8.8 (2.6) | 0.3 (-0.8 to 1.3) | 0.6 | -8.5 (2.0) | -8.8 (2.5) | 0.4 (-0.6 to 1.4) | 0.4 |

| A2 | 7.3 (2.8) | 8.6 (3.8) | 8.9 (3.5) | -0.3 (-1.5 to 0.9) | 0.6 | 8.7 (3.9) | 7.9 (3.9) | 0.7 (-0.6 to 2.0) | 0.3 |

| Knee | |||||||||

| K1 | -4.5 (5.1) | -4.7 (3.8) | -4.5 (4.3) | -0.2 (-2.0 to 1.6) | 0.8 | -5.1 (3.8) | -3.2 (4.7) | -1.8 (-4.0 to 0.4) | 0.1 |

| K2 | -18 (5.5) | -17 (3.7) | -17 (6.2) | 0.1 (-2.4 to 2.6) | 1.0 | -17 (3.6) | -16 (5.8) | -0.9 (-3.1 to 1.2) | 0.4 |

| K3 | -3.0 (4.4) | -6.1 (4.2) | -6.7 (5.4) b | 0.6 (-1.1 to 2.3) | 0.5 | -6.1 (4.4) | -5.0 (5.6) | -1.0 (-3.2 to 1.1) | 0.3 |

| Hip | |||||||||

| H1 | -13 (4.5) | -10 (4.8) | -9.6 (4.6) b | -0.6 (-2.2 to 1.0) | 0.4 | -11 (3.9) | -12 (4.2) | 1.1 (-0.3 to 2.6) | 0.1 |

| Run stance phase, s | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) b | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.2 | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.5 |

| Run velocity, m/s | 2.6 (0.3) | 2.4 (0.4) | 2.4 (0.3) | 0.0 (-0.1 to 0.1) | 0.6 | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.4 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.2) | 0.2 |

| Peak joint angles in running, degrees | |||||||||

| Ankle | |||||||||

| A1 | 2.2 (3.8) | 1.8 (6.0) | 4.1 (3.1) b | -2.3 (-4.7 to -0.0) | 0.05 | 2.6 (6.0) | 3.7 (4.7) | -1.2 (-2.6 to 0.3) | 0.1 |

| A2 | 21 (3.8) | 20 (4.7) | 21 (3.5) | -1.2 (-2.7 to 0.3) | 0.1 | 21 (4.4) | 21 (3.4) | -0.3 (-1.7 to 1.1) | 0.7 |

| Knee | |||||||||

| K1 | -14 (6.6) | -13 (6.5) | -15 (5.8) | 1.7 (-0.9 to 4.4) | 0.2 | -14 (6.5) | -13 (6.4) | -0.6 (-2.7 to 1.5) | 0.5 |

| K2 | -42 (5.8) | -39 (8.2) | -40 (6.4) | 1.2 (-1.3 to 3.7) | 0.3 | -41 (6.1) | -40 (5.9) | -0.7 (-2.6 to 1.2) | 0.5 |

| K3 | -15 (5.6) | -16 (6.8) | -17 (6.4) | 0.8 (-1.4 to 3.0) | 0.4 | -17 (5.4) | -16 (5.5) | -1.3 (-3.1 to 0.6) | 0.2 |

| Hip | |||||||||

| H1 | -5.6 (3.9) | -4.1 (5.6) | -4.3 (4.4) | 0.2 (-1.6 to 2.0) | 0.8 | -5.0 (5.3) | -5.0 (4.0) | 0.0 (-2.1 to 2.1) | 1.0 |

aPeak values are reported as mean values and standard deviation. Differences between the outcomes before and after PAO were tested with paired t-test and are reported as mean differences (95% CI). Differences between patients and healthy controls were tested with unpaired t-test.

bSignificantly different compared with the healthy controls.

PAO: periacetabular osteotomy; A1: peak plantar flexion in the first half of the stance phase; A2: peak dorsiflexion in the second half of the stance phase; K1: extension at heel strike; K2: peak flexion in the first half of the stance phase; K3: peak extension in the second half of the stance phase; H1: peak extension.

Table 3.

Peak joint moments in patients with hip dysplasia and in controls

| Peak joint moments, N*m/kg | Baseline | Baseline | 6 months after PAO |

Baseline | 12 months after PAO |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n = 32) a | Patients (n = 25) a | Patients (n = 25) a | Difference (CI) | p-value | Patients (n = 23) a | Patients (n = 23) a | Difference (CI) | p-value | ||

| In walking | ||||||||||

| Ankle | ||||||||||

| MA1 | 0.20 (0.05) | 0.18 (0.05) | 0.18 (0.05) | 0.00 (-0.02 to 0.02) | 0.8 | 0.18 (0.05) | 0.19 (0.09) | -0.01 (-0.04 to 0.03) | 0.7 | |

| MA2 | -1.56 (0.17) | -1.46 (0.13) | -1.51 (0.11) | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.09) | 0.007 | -1.51 (0.11) | -1.48 (0.35) | -0.03 (-0.16 to 0.10) | 0.7 | |

| Knee | ||||||||||

| MK1 | -0.46 (0.11) | -0.40 (0.14) | -0.45 (0.14) | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.09) | 0.009 | -0.41 (0.11) | -0.47 (0.10) | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.10) | 0.01 | |

| MK2 | 0.46 (0.19) | 0.36 (0.18) | 0.28 (0.20) b | 0.08 (0.02 to 0.15) | 0.02 | 0.37 (0.16) | 0.30 (0.16) b | 0.07 (0.00 to 0.13) | 0.04 | |

| MK3 | -0.54 (0.14) | -0.42 (0.19) | -0.51 (0.19) | 0.10 (0.04 to 0.15) | 0.002 | -0.44 (0.13) | -0.55 (0.15) | 0.12 (0.06 to 0.18) | < 0.001 | |

| MK4 | 0.26 (0.13) | 0.21 (0.06) | 0.29 (0.09) | -0.08 (-0.12 to -0.03) | 0.001 | 0.22 (0.06) | 0.34 (0.11) b | -0.12 (-0.17 to -0.07) | < 0.001 | |

| Hip | ||||||||||

| MH1 | -1.19 (0.20) | -1.05 (0.27) | -1.07 (0.30) | 0.02 (-0.06 to 0.11) | 0.6 | -1.06 (0.21) | -1.09 (0.24) | 0.03 (-0.08 to 0.14) | 0.5 | |

| MH2 | 0.70 (0.22) | 0.57 (0.13) | 0.72 (0.18) | -0.15 (-0.24 to -0.06) | 0.002 | 0.59 (0.13) | 0.80 (0.22) | -0.22 (-0.32 to 0.11) | < 0.001 | |

| In running | ||||||||||

| Ankle | ||||||||||

| MA1 | 0.17 (0.12) | 0.16 (0.17) | 0.16 (0.07) | 0.00 (-0.05 to 0.06) | 0.9 | 0.14 (0.19) | 0.13 (0.10) | 0.01 (-0.05 to 0.07) | 0.7 | |

| MA2 | -2.32 (0.41) | -2.22 (0.40) | -2.16 (0.33) | -0.06 (-0.17 to 0.05) | 0.3 | -2.33 (0.44) | -2.33 (0.35) | 0.00 (-0.12 to 0.12) | 1.0 | |

| Knee | ||||||||||

| MK1 | -0.49 (0.18) | -0.47 (0.21) | -0.44 (0.15) | -0.04 (-0.13 to 0.06) | 0.4 | -0.49 (0.22) | -0.45 (0.14) | -0.04 (-0.12 to 0.04) | 0.3 | |

| MK2 | 1.87 (0.42) | 1.68 (0.48) | 1.48 (0.42) b | 0.20 (0.02 to 0.37) | 0.03 | 1.70 (0.52) | 1.57 (0.41) b | 0.13 (-0.03 to 0.29) | 0.1 | |

| MK3 | -0.20 (0.15) | -0.24 (0.23) | -0.24 (0.18) | 0.00 (-0.10 to 0.09) | 1.0 | -0.30 (0.34) | -0.23 (0.12) | -0.07 (-0.20 to 0.06) | 0.3 | |

| MK4 | 1.58 (0.41) | 1.35 (0.46) | 1.17 (0.43) b | 0.17 (0.01 to 0.33) | 0.04 | 1.39 (0.47) | 1.25 (0.35) b | 0.14 (-0.00 to 0.28) | 0.06 | |

| Hip | ||||||||||

| MH1 | -1.74 (0.42) | -1.49 (0.43) | -1.47 (0.32) b | -0.02 (-0.19 to 0.15) | 0.8 | -1.55 (0.46) | -1.45 (0.32) b | -0.10 (-0.24 to 0.03) | 0.1 | |

| MH2 | 0.85 (0.30) | 0.70 (0.34) | 0.86 (0.21) | -0.16 (-0.29 to -0.03) | 0.02 | 0.63 (0.48) | 0.86 (0.22) | -0.23 (-0.45 to -0.02) | 0.04 | |

aPeak values are reported as mean values with standard deviation. Differences between the outcomes before and after PAO were tested with paired t-test and reported as mean differences (95% CI). Differences between patients and healthy controls were tested with unpaired t-test.

bSignificantly different compared to healthy controls.

PAO: periacetabular osteotomy; MA1: peak dorsiflexion moment in the first half of the stance phase; MA2: peak plantar flexion moment in the second half of the stance phase; MK1 and MK2: peak flexion and extension moments in the first half of the stance phase; MK3 and MK4: peak flexion and extension moments in the second half of the stance phase; MH1: peak hip extension moment in the first half of the stance phase; MH2: peak hip flexion moment in the second half of the stance phase.

Speed and duration of the stance phase were similar between the groups (Table 2). Except for the duration of the stance phase in running 6 months after PAO, there were no significant differences between the patients and the healthy controls.

The peak hip flexion moment during walking was higher at both the 6-month and the 12-month follow-up than at baseline, with an increase of 26% from baseline to 12-month follow-up (mean 0.59 (0.13) to 0.80 (0.22)). With running, the peak hip flexion moment increased after 6 months but did not reach statistical significance after 12 months. In addition, the hip extension angle during walking increased by 8% 12 months after PAO, though not statistically significantly (–11 (3.9) to –12 (4.2)). For the primary outcome measures, there were no significant differences between the healthy controls and the patients 12 months after PAO. However, for both walking and running, the patients had lower knee extensor moment in the second half of the stance phase at both follow-ups compared to the healthy controls, and for running, knee extensor moment was also lower in the first half of the stance phase at both follow-ups. In addition, the hip extension moment in running was lower at both follow-ups.

Discussion

Our hypothesis was confirmed: hip flexion moment during walking was higher at both 6 and 12 months of follow-up than at baseline. In running, the hip flexion moment also increased at 6 months, but at 12 months the improvement was not statistically significant. In addition, in walking the hip extension angle improved 12 months after PAO, but not statistically significantly so.

Concerning primary outcomes, no differences were found between patients 12 months after PAO and healthy controls; this could indicate a normalization of the gait pattern. However, knee and hip extensor moments were generally smaller in the patients, and this was not associated with smaller joint angles. Thus, the decreased moments could instead indicate a general inhibition mechanism caused by nociceptive inputs. Previous studies have found that a pain avoidance pattern expressed as reduced muscle activity is present before and after experimentally induced muscle pain (Graven-Nielsen et al. 2008, Henriksen et al. 2009), and it is possible that earlier and current pain in the groin and the surrounding muscles affects the gait pattern. We did not measure muscle activity and therefore no conclusions can be made regarding a possible pain avoidance pattern.

Regarding the clinical significance of our present findings, the increase in hip extension at 12 months was only 8%. The difference in hip extension at baseline between healthy controls and patients was also well within the normal range, and therefore a major and clinically significant change from baseline to 12-month follow-up is probably not possible. As opposed to the kinematics, the hip flexion moment increased by 26% from baseline to follow-up, and this indicates that 12 months postoperatively, patients are fully capable of normal force loading at the frontal side of the hip, which together with absence of pain and prevention of osteoarthritis is one of the goals of the PAO.

Since it is time consuming to perform movement analysis, it is relevant to ask what extra information we obtain that cannot be obtained from patient-reported outcomes. Movement analysis is an objective examination of hip mechanics in the patient whereas patient-reported hip status is subjective and therefore measures different aspects of the effects of hip dysplasia—aspects that influence one’s physical function, and aspects that affect the mental impact of hip dysplasia. Objective measures of the hip flexor moment provide information on the mechanical reorientation of the acetabulum and the possibility of normal sagittal-plane kinetics of the hip.

During the study period, 3 patients reported internal snapping hip, 2 patients underwent hip arthroscopy due to labrum pain, and 4 patients had a PAO on their contralateral hip. It is possible that the results from these patients had a negative effect on the results. Yet, they represent patients with hip dysplasia, and if we had excluded these patients, our sample would not have been representative of the target population.

Pedersen et al. (2006) reported a more upright walking pattern postoperatively than preoperatively, but the hip flexion moment did not improve statistically significantly. In contrast to the study by Pedersen et al. (2006), in the present study the hip flexion moment increased at both 6 and 12 months after PAO during walking and at 6 months during running. Although the joint moment in running did not reach statistical significance after 12 months, we believe that the improvement in running is also valid

Sucato et al. (2010) also reported walking outcomes in patients with hip dysplasia after PAO, and found a lower walking speed in patients 12 months after PAO than in healthy controls. This was not supported in our study, and the walking speed of our patients was similar to the walking speed of the healthy controls in the study by Sucato et al. (2010).

In all dimensions of HAGOS, the patients had clinically meaningful improvements at both follow-ups compared to baseline, but at 12 months differences still existed between the patients and the healthy controls. The psychometric properties of the HAGOS have been evaluated in patients undergoing hip arthroplasty (Kemp et al. 2013). The minimum detectable change (MDC) in patients was 19, indicating that our differences are consistent. Our patients scored lower in all dimensions of the HAGOS at both follow-ups compared to the scores reported in individuals with hip and/or groin pain and patients treated with hip arthroplasty (Thorborg et al. 2011, Kemp et al. 2013). Troelsen et al. (2009) also reported similarly low scores of the physical components of the Short Form-36 in patients with hip dysplasia 7 years after PAO, indicating that the health-related quality of life may not change significantly after a longer follow-up period.

The VAS value at rest, for walking, and for running was between 0 and 5 mm at the 2 follow-ups; this is similar to the VAS values reported by Troelsen et al. (2009) 7 years after PAO in patients with hip dysplasia. The relatively low VAS values together with the relatively low score in the HAGOS dimensions “sport and recreation” and “participation” may indicate that the patients reduce their sport activities and participation after PAO to minimize their symptoms.

We used a Bonferroni correction to reduce the risk of type-1 error, in order to take into account that our 2 primary outcome measures—the peak hip extension angle and the peak net joint moment of hip flexion—were believed to lie in a zone between dependent and independent. We found it relevant to correct the alpha level for these 2 outcomes. We are aware that this might be a conservative approach, but we chose to make the correction in order to minimize the risk of type-1 error.

The limitations of our study design have been discussed in depth in an earlier publication (Jacobsen et al. 2013). Briefly, we cannot rule out that some of our healthy controls may have had undiagnosed asymptomatic hip dysplasia. This would, however, only have led to smaller differences between the groups. The healthy controls were only measured once at baseline, and even though the criteria for selection of the controls were the absence of disease, day-to-day variation is possible—so it is possible that there was variation in the reported values of the healthy controls, which should be kept in mind. Moreover, our participants were walking and running at self-selected speeds, because we wanted to evaluate a normal and spontaneous movement pattern. An effect of the self-selected speed might be that the differences found in the present study may only have been due to differences in speed (Oberg et al. 1994, Stoquart et al. 2008). However, we did not find any differences in speed between the patients at the different follow-ups, and there were no significant differences in speed between the patients and the healthy controls; this indicates that our results were not from differences in gait speed. Another limitation is that only sagittal-plane outcomes were measured. We chose to evaluate outcomes in the sagittal plane as reported by Pedersen et al. (2004, 2006) in order be able to compare outcomes obtained with the minimally invasive method with outcomes obtained with the conventional Bernese PAO, which Pedersen et al. investigated. Sagittal-plane evaluation of movement ought to be sufficient, since Sucato et al. (2010) found no differences in the frontal-plane kinetics in walking in a similar group of patients. Furthermore, Alkjaer et al. (2001) concluded that different models did not affect the inter-individual variation and the simpler 2D model seemed appropriate for human gait analysis. However, in another study Romano et al. (1996) reported differences in the frontal and transversal planes, and we cannot rule out the possibility that differences existed in these planes in our patients. Further studies on gait outcomes in these planes appear warranted.

The hip flexion moment in running did not increase statistically significantly at 12-month follow-up; this could be explained by the fact that the standard deviation in running at baseline turned out to be larger than expected. This is probably due to different running patterns (such as the footfall pattern or the flatfoot pattern) (Robertson et al. 2004). Another reason may be that the stance phase in running lasts a smaller percentage of the gait cycle than in walking, resulting in differences in timing of the angles and joint moment (Robertson et al. 2004). The VAS scores in walking and running were similar after 12 months; thus, pain differences cannot explain why the joint moments in running had not increased significantly at 12 months. However, statistically significant differences were found in walking, indicating that analysis of walking is sufficient and relevant if surgical or training intervention is to be evaluated in future studies.

In conclusion, walking and running characteristics improve after PAO in patients with symptomatic hip dysplasia. Gait modifications are still present 12 months after PAO. Furthermore, future studies should evaluate the role of pelvic and trunk motion together with frontal- and transversal-plane kinetics and kinematics, and also the muscle function.

Acknowledgments

All the authors took part in planning and writing of this study and in the testing. IM concentrated on the design and use of methods, while DBN and HS tested the participants and were responsible for the mechanical part. KS was responsible for the inclusion and operation of patients. JSJ coordinated all elements of the study, and was responsible for inclusion of the participants in collaboration with KS.

We thank colleagues at Aarhus University, and at the Departments of (1) Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy and (2) Orthopaedic Surgery, Aarhus University Hospital. Funding was received from the Danish Rheumatism Association, the Aase and Ejnar Danielsen Fund, the Research Programme for Rehabilitation (from disease to daily living) at Aarhus University Hospital (MVU-Fonden), the Danish Physiotherapists Research Foundation, the Research Foundation of the Professional Forum for Physiotherapy in Sports, the Agricultural Foundation, and the Orthopaedic Research Foundation in Aarhus.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Alkjaer T, Simonsen EB, Dyhre-Poulsen P. Comparison of inverse dynamics calculated by two- and three-dimensional models during walking . Gait Posture. 2001;13(2):73–7. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(00)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappozzo A, Cappello A, Della Croce U, Pensalfini F. Surface-marker cluster design criteria for 3-D bone movement reconstruction . IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1997;44(12):1165–74. doi: 10.1109/10.649988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooperman DR, Wallensten R, Stulberg SD. Acetabular dysplasia in the adult . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;175:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;232:26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L. Impact of clinical and experimental pain on muscle strength and activity . Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10(6):475–81. doi: 10.1007/s11926-008-0078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartofilakidis G, Karachalios T, Stamos KG. Epidemiology, demographics, and natural history of congenital hip disease in adults . Orthopedics. 2000;23(8):823–7. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20000801-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen M, Alkjaer T, Simonsen EB, Bliddal H. Experimental muscle pain during a forward lunge-the effects on knee joint dynamics and electromyographic activity . Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(7):503–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.050393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen JS, Nielsen DB, Sorensen H, Soballe K, Mechlenburg I. Changes in walking and running in patients with hip dysplasia . Acta Orthop. 2013;84(3):265–70. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.792030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen S, Romer L, Soballe K. The other hip in unilateral hip dysplasia . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:239–46. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000201151.91206.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp JL, Collins NJ, Roos EM, Crossley KM. Psychometric properties of patient-reported outcome measures for hip arthroscopic surgery . Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2065–73. doi: 10.1177/0363546513494173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaue K, Durnin CW, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome. A clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip . J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(3):423–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leunig M, Ganz R. Evolution of technique and indications for the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy . Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2011;69(Suppl 1):S42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechlenburg I, Kold S, Romer L, Soballe K. Safe fixation with two acetabular screws after Ganz periacetabular osteotomy . Acta Orthop. 2007;78(3):344–9. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechlenburg I, Kold S, Soballe K. No change detected by DEXA in bone mineral density after periacetabular osteotomy . Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(6):761–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SB, Ganz R, Muller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):985–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehme A, Trousdale R, Tannous Z, Maalouf G, Puget J, Telmont N. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: is acetabular retroversion a crucial factor? . Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(7):511–9. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novais EN, Heyworth B, Murray K, Johnson VM, Kim YJ, Millis MB. Physical activity level improves after periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of symptomatic hip dysplasia . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(3):981–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2578-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunley RM, Prather H, Hunt D, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Clinical presentation of symptomatic acetabular dysplasia in skeletally mature patients . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(Suppl 2):17–21. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberg T, Karsznia A, Oberg K. Joint angle parameters in gait: reference data for normal subjects, 10-79 years of age . J Rehabil Res Dev. 1994;31(3):199–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen EN, Simonsen EB, Alkjaer T, Soballe K. Walking pattern in adults with congenital hip dysplasia: 14 women examined by inverse dynamics . Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(1):2–9. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001708010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen EN, Alkjaer T, Soballe K, Simonsen EB. Walking pattern in 9 women with hip dysplasia 18 months after periacetabular osteotomy . Acta Orthop. 2006;77(2):203–8. doi: 10.1080/17453670610045920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson GE, Caldwell GE, Hamill J, Kamen G, Whittlesey SN. Research methods in biomechanics. Human kinetics, Champain. 2004.

- Romano CL, Frigo C, Randelli G, Pedotti A. Analysis of the gait of adults who had residua of congenital dysplasia of the hip . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(10):1468–79. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steppacher SD, Tannast M, Ganz R, Siebenrock KA. Mean 20-year followup of Bernese periacetabular osteotomy . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1633–44. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0242-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucato DJ, Tulchin K, Shrader MW, DeLaRocha A, Gist T, Sheu G. Gait, hip strength and functional outcomes after a Ganz periacetabular osteotomy for adolescent hip dysplasia . J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(4):344–50. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181d9bfa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoquart G, Detrembleur C, Lejeune T. Effect of speed on kinematic, kinetic, electromyographic and energetic reference values during treadmill walking . Neurophysiol Clin. 2008;38(2):105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorborg K, Holmich P, Christensen R, Petersen J, Roos EM. The Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS): development and validation according to the COSMIN checklist . Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(6):478–91. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.080937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troelsen A, Elmengaard B, Soballe K. A new minimally invasive transsartorial approach for periacetabular osteotomy . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;90(3):493–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troelsen A, Elmengaard B, Soballe K. Medium-term outcome of periacetabular osteotomy and predictors of conversion to total hip replacement . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(9):2169–79. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tönnis D. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg New York: 1987. Congenital dysplasia and dislocation of the hip in children and adults. [Google Scholar]