Abstract

Background and purpose —

In orthopedic oncology, computer-assisted surgery (CAS) can be considered an alternative to fluoroscopy and direct measurement for orientation, planning, and margin control. However, only small case series reporting specific applications have been published. We therefore describe possible applications of CAS and report preliminary results in 130 procedures.

Patients and methods —

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all oncological CAS procedures in a single institution from November 2006 to March 2013. Mean follow-up time was 32 months. We categorized and analyzed 130 procedures for clinical parameters. The categories were image-based intralesional treatment, image-based resection, image-based resection and reconstruction, and imageless resection and reconstruction.

Results —

Application to intralesional treatment showed 1 inadequate curettage and 1 (other) recurrence in 63 cases. Image-based resections in 42 cases showed 40 R0 margins; 16 in 17 pelvic resections. Image-based reconstruction facilitated graft creation with a mean reconstruction accuracy of 0.9 mm in one case. Imageless CAS was helpful in resection planning and length- and joint line reconstruction for tumor prostheses.

Interpretation —

CAS is a promising new development. Preliminary results show a high number of R0 resections and low short-term recurrence rates for curettage.

Oncological surgical treatment can be considered to be a trade-off between margins and function, with margins being the most important factor to consider. Accuracy is needed to achieve an efficient but oncologically safe result. To assist in this, most procedures in bone tumor surgery require intraoperative imaging with fluoroscopy and/or measurements with rulers for anatomical orientation and margin control. The best examples of this are pelvic resections. Cartiaux et al. (2008) demonstrated that 4 experienced surgeons could achieve a 10-mm resection margin, with 5-mm tolerance, on pelvic sawbones in only half of the resections. The supportive imaging and measuring modalities have, however, remained more or less unchanged for many years. In a 2-dimensional (2D) workflow such as fluoroscopy, there is still the requirement for an accurate frame of reference based on anatomical landmarks for adequate 3-dimensional (3D) margin control.

In recent years, the use of computer-assisted surgery (CAS) in orthopedic surgery has become more common as an alternative for intraoperative imaging and measurements, providing the necessary precision in bone tumor surgery. The technique that is mostly used in orthopedic oncology is image-based navigation. The patient’s own anatomy (MRI and/or CT) is entered into the system and used during surgery. This provides real-time, continuous, 3D imaging feedback and may lead to more precise margin control, better tissue preservation, and new approaches to reconstruction while remaining oncologically safe. Several publications have supported CAS as being a safe navigation platform for planning and performing resections (Wong et al. 2007, So et al. 2010, Cho et al. 2012). A recent publication describes lessons in the technological approach and offers comments on CAS workflow (Wong 2010). However, to date the largest case series have involved only 20 and 31 cases (Cheong and Letson 2011, Jeys et al. 2013). The reported use has mostly been limited to complex tumor resections (e.g. pelvic), and due to the novelty of the technique, applications, approaches, and set-up times differ greatly (Saidi 2012). Here we describe possible applications of CAS in bone tumor surgery (also outside of complex resections), consider their usefulness, and report preliminary results from 130 CAS procedures performed at a single institution.

Patients and methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at the University Medical Center, Groningen (UMCG) between November 2006 and March 2013. We included all patients with a bone tumor for whom a CAS procedure was planned. The included group was split into a successful CAS procedure group and a CAS set-up failure group. Procedures were regarded as being successful when the CAS set-up was successfully completed and the system was used. If the set-up of the system failed or unsolvable inaccuracies were found during the set-up process, the procedure was regarded as a CAS set-up failure and the surgery was performed by conventional means. The successful CAS procedures were analyzed based on the following outcome parameters: recurrence/residue rate and margins achieved. CAS set-up failures were assessed for cause of failure. These failures were not included in the outcome analysis, as the procedures were performed using conventional methods and the purpose was to analyze the CAS application, not indications.

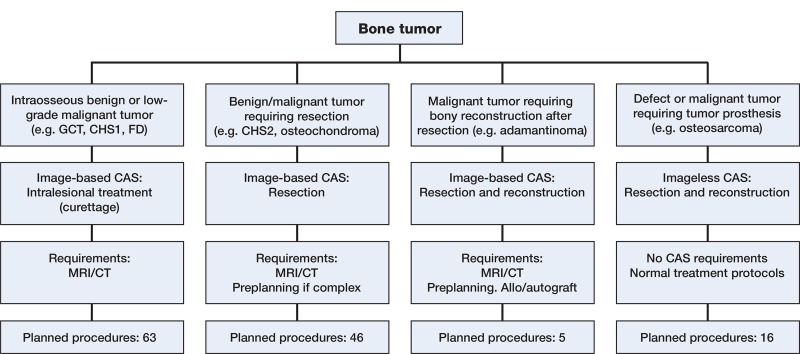

All CAS procedures were first classified according to the technique used: image-based or imageless. The image-based group was then subdivided into “intra-lesional procedures” (curettages), “resection procedures”, and “resection with reconstruction procedures” (Figure 1). The imageless group comprised tumor prosthesis placement around the knee.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the decision-making process on CAS use, requirements per technique, and planned procedures per technique. From left to right: intralesional treatment with a navigated curette, image-based resection, image-based resection and reconstruction, and imageless resection and reconstruction.

Image-based workflow

The standardized preoperative workflow consisted of a CT-scan of the affected bone, following a CAS protocol. Slice thickness was 1.0–1.5 mm for CT. If required, preoperative planning was performed to pre-plan resection planes and/or reconstruction options. This pre-planning was performed in advance on the planning laptop and often included CT/MRI fusion, tumor coloration, and resection planning.

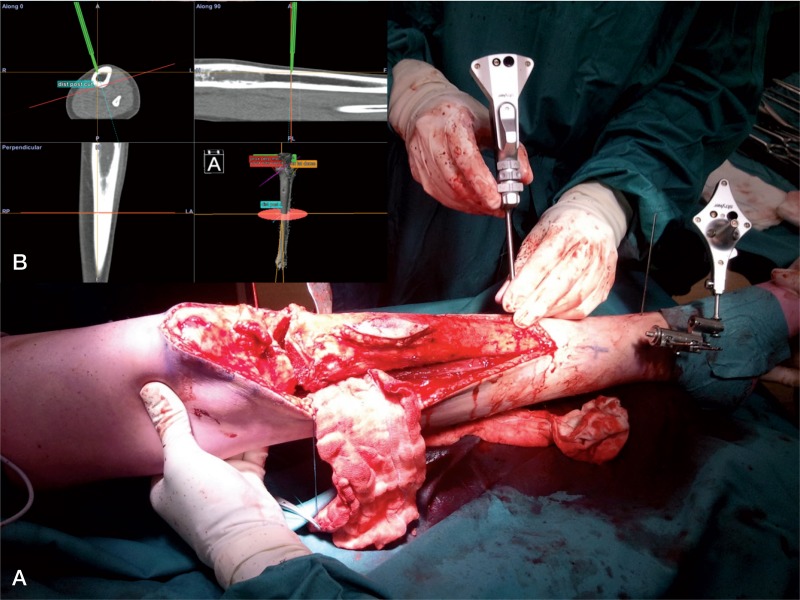

During a CAS procedure, a patient tracker was rigidly attached to the involved bone of the patient (Figure 2). Image-based navigation was set up by entering reference points, first in the navigation system and then on landmarks on the bone. The result was a fairly rough matching with moderate accuracy. This was refined using surface matching, where data points were entered with the pointer tool directly on the navigated bone. The software matched this to the bone surface on the CT. Approximate accuracies under 1.5 mm were accepted and a landmark check was performed routinely. If the landmark check failed after multiple set-up attempts, the procedure was considered to be a CAS set-up failure, the navigation was discontinued, and the surgery was performed by conventional means. Set-up time and accuracy were measured using a digital registration system. Postoperative margins were classified by the R classification (Edge and Compton 2010). Clinical follow-up was routinely performed with radiographs and MRI scans. We used the Stryker Navigation System II with OrthoMap 3D software (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ).

Figure 2.

A. Tracker rigidly attached to the tibia using percutaneous pins. Visible is the pointer tool being used for planning the distal resection plane around a Ewing sarcoma. The corresponding CAS view can be seen in the image. B. Surgical plan: a dome-shaped proximal resection very close to the tibial plateau, distal resection, and then reconstruction with a hybrid, allogenic and autogenic massive allograft.

Intralesional treatment

Intentional intralesional treatment (curettage) was used for benign and low-grade malignant bone tumors such as giant cell tumor (GCT), aneurysmal bone cyst, fibrous dysplasia, and grade-1 chondrosarcoma (CHS-1) (now renamed atypical cartilaginous tumor (ACT)). All CHS-1 lesions were curetted and treated with adjuvant phenol and ethanol. Some lesions were treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) beforehand. Most reconstructions were done with PMMA bone cement; some were done with cancellous bone chip: Vitoss (Orthovita, Malvern, PA). Most recent reconstructions were done with Engipore (Finceramica SpA, Faenza, Italy). We did not use fluoroscopic control at the end of surgery. Follow-up was standardized, with radiographic controls and a baseline MRI scan 3 months postoperatively. As an indicator of the effect of CAS on surgical time, we documented reported surgical time in the operating room management software for all procedures in the largest homogenous group, CHS-1 intralesional treatment, with either CAS and fluoroscopy, within the inclusion period.

Image-based resections

Resection planes were planned before surgery, incorporating the margin required for the specific lesion, and checked intraoperatively. Preoperative planning consisted of CT/MRI image fusion if available, segmentation (coloring) of the tumor and critical structures, depending on tumor type and location. The pointer tool was used before and after each resection to determine and check the resection plane. Planes for the bone saw were sometimes marked with Kirschner wires, placed with navigation, as a guide for plane orientation and angulation. As proof of complete resection, screen shots of the pointer tool or navigated chisel on the planned resection plane behind the tumor were saved on the CAS machine. Every bone resection had a routine postoperative radiographic control and pathological examination.

Image-based resections and reconstructions

This procedure was performed for hemicortical resections, creating and reconstructing a partial defect and 1 full resection. Preoperative planning consisted of CT/MRI image fusion, digital linking of the host bone CT with the allograft CT, planning of the resection planes (and subsequent reconstruction planes), and entering of special interest points where resection planes intersected other planes or the cortex. Exactly the same resection planes were used for both resection of the tumor and creation of the allograft piece, to create an exact-fitting graft. The reconstructions of these defects were done with allogenic inlay bone grafts, in 1 case combined with a vascularized autograft. The allografts from the bone bank were selected based on matching of the dimensions to the host bone. The planned resection was then performed on the patient bone and subsequently repeated on the allograft bone.

Imageless workflow and imageless resection and reconstruction

Imageless workflow comprised a normal imageless knee set-up, with trackers on the femur and tibia. The imageless system provided accurate measurements of length and rotation. The software used in these cases was Precision Knee Navigation on the same navigation system.

All imageless cases were performed on or around the knee joint. The resection length was identified by CAS using the pointer tool. Joint line reconstruction, length-checking, and rotation were done with the normal imageless prosthesis-placement checking tools. We used a modular GSMS/MRH tumor prosthesis (Stryker) in all cases.

Results

The most performed procedure was grade-1 chondrosarcoma curettage (Table). The “reactive lesions” group contained cases where the surgery was performed by oncological principles but the pathological diagnosis was not a tumor. Most CAS procedures were done for a lesion in the femur (68 of 130). Mean follow-up time was 32 (4–80) months.

CAS patients with distribution of diagnoses for all CAS procedures, and individually for each procedure type. The index of diagnoses has been sorted by the number of patients

| Image-based intralesional treatment | Image-based resection | Image-based resection and reconstruction | Imageless resection and reconstruction | Total no. of procedures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHS grade 1 | 43 | 3 | 46 | ||

| Osteochondroma | 26 | 26 | |||

| Osteosarcoma | 1 | 10 | 11 | ||

| Reactive lesions | 7 | 7 | |||

| Fibrous dysplasia | 7 | 7 | |||

| CHS grade 2 | 5 | 5 | |||

| Adamantinoma | 4 | 4 | |||

| Chondroblastoma | 4 | 4 | |||

| Giant cell tumor | 3 | 3 | |||

| Metastasis | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Other | 2 | 2 | |||

| ABC | 2 | 2 | |||

| CHS grade 3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ewing sarcoma | 1 | 1 | |||

| Total no. of successful CAS | 60 | 43 | 5 | 14 | 122 |

| Total no. of CAS failures | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 | |

| Total no. of procedures | 63 | 46 | 5 | 16 | 130 |

Intralesional treatment

CAS was used as an alternative to fluoroscopy in 60 procedures (Figure 3). The mean follow-up time was 25 (4–68) months. Most procedures were done for CHS-1. In 1 case of CHS-1 of the humerus, the postoperative radiographic control showed residual tumor. This was confirmed by biopsy and was treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA). There was 1 recurrence of a CHS-1, 15 months after primary treatment. A biopsy showed vital tumor tissue and no dedifferentiation, and the lesion was treated with RFA. 43 CHS-1 patients were treated using CAS. This resulted in a recurrence rate of 1 in 43 for this group, at a mean follow-up time of 24 (7–61) months. There were 4 pathological fractures, all of which were treated and healed with internal fixation. Median surgical time was similar in the 2 groups: it was 1 hour and 24 min (0:54–3:10) in 88 non-CAS CHS-1 intralesional treatment procedures and it was 1 hour and 26 min (0:37–2:25) in the 43 CAS procedures (p = 0.7).

Figure 3.

A screen shot acquired on the CAS system during curettage. Patient information has been digitally edited out. The case was a 31-year-old patient with fibrous dysplasia of the femoral head. The location was such that there was a risk of damaging the cartilage on the femoral head during curettage, potentially invalidating the patient. The cavity was filled with PMMA. Weight bearing was 50% in the first 6 weeks, gradually increasing to full in the 6 weeks that followed.

Image-based resection

There were 43 CAS procedures with a mean follow-up time of 39 (5–80) months. 40 of 43 procedures were classified as R0 resections; 1 CHS grade-2 periacetabular resection had R1 margins due to a compromised soft-tissue margin, 1 CHS grade-1B proximal tibia had R1 margins due to a compromised bone margin, and 1 pelvic CHS grade-2A had an R2 resection—also due to compromised bone margins. The patient with peripheral CHS-1 of the fibula with inadequate bone margins (R1) had a re-resection, but it did not show residual tumor, and the patient is disease-free 6 years after surgery.

6 of 17 pelvic resections were performed for high-grade tumors. 2 of 4 Enneking type-2/3 resections (Enneking and Dunham 1978), 1 of 1 type-1/2/3 hemipelvectomy, and 1 of 1 type-2 resection had R0 margins. 1 of 2 type-2/3 resections had a soft-tissue R1 resection as described above. All others, except 1 type-3 resection for a large osteochondroma, were partial resections. All had R0 margins.

There were 4 local recurrences: pelvic chondrosarcoma grade-2 (2 resections, R2 and R0), pelvic CHS grade-3 (1 resection, R0) and osteosarcoma of the femur (1 resection, R0). 3 patients—all of whom had local recurrence and dedifferentiation—died of disease, pelvic CHS grade 2 (2 patients), and pelvic CHS grade 3 (1 patient). In these 3 patients, dedifferentiation of the tumor was found in the biopsy of the local recurrence.

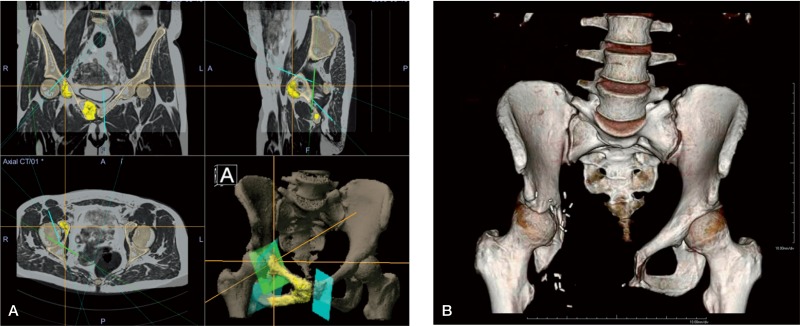

Joint-sparing procedures were performed using CAS, for example using a modified Enneking 2/3 acetabulum-sparing resection in a case of grade-2 chondrosarcoma of the pelvis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A. (left panel). Surgical planning of the resection planes in the Orthomap oncology module with coloration of the tumor on the fused MRI/CT image. Patient information has been digitally edited out in the bottom-left panel. The bottom-right panel shows a 3D rendering of the pelvic bone and the resection planes. Two-thirds of the acetabulum could be saved. The patient was disease-free at the 5-year follow-up, functions well, and has resumed work. B. (right panel). 3D AP volume rendering of the 3.5-year follow-up CT.

Image-based resection and image-based reconstruction

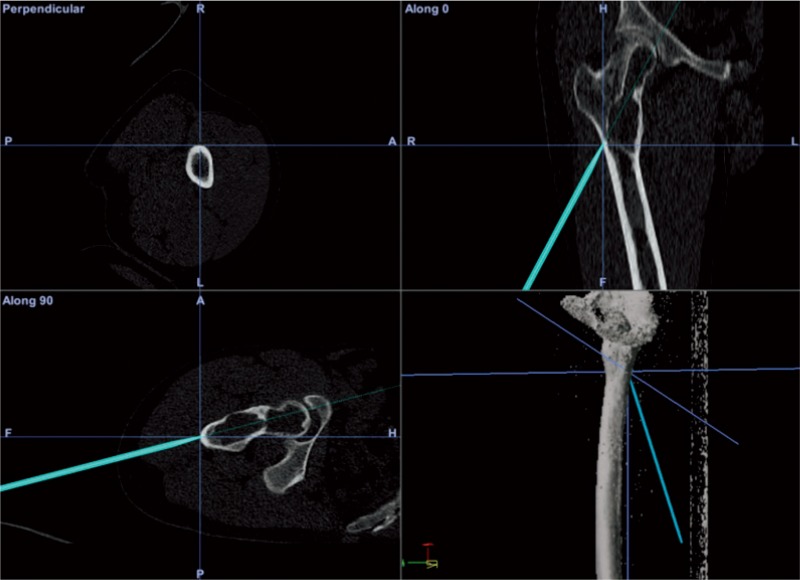

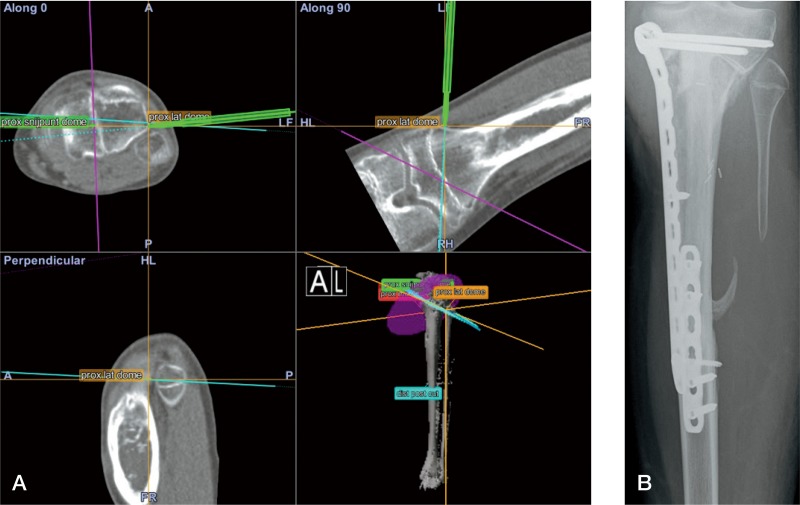

4 adamantinoma cases were treated with hemicortical resections and 1 Ewing sarcoma was treated with a segmental resection and solid allograft bone reconstruction. Mean follow-up time was 20 (10–33) months. The mean length of reconstruction for the hemicortical cases was 8 (6–9) cm, for the segmental reconstruction case it was 19 cm. In 3 of 4 hemicortical cases, half or more of the bone circumference was affected by the tumor. A CT-scan of 1 case showed an mean gap between host and allograft of 0.9 (0–5.4) mm along the 6-cm resection (Figure 5) (Gerbers et al. 2013). All margins were classified as R0. There was 1 local recurrence in an adamantinoma, after an R0 resection with adequate margin, located in the soft-tissue resection plane. There were no complications.

Figure 5.

A. An image-based resection and reconstruction procedure; intraoperative screen shot of the navigation system. The pointer tool is being used to align 1 of the 2 resection planes of the proximal “dome”-type resection. An intraoperative view is shown in Figure 2. B. Anteroposterior radiograph of the patient 11 months after surgery. Progressive incorporation of the allograft and vascularized autograft.

Imageless resection and reconstruction

There were 14 procedures with a mean follow-up of 41 (8–60) months. The CAS group comprised 10 osteosarcomas, 2 metastases, and 2 tumor prosthetic placements in non-union or allograft failure after earlier tumor surgery. All tumor resections were reported as R0 resections. The 10 osteosarcomas could be subdivided using MSTS classification into: IA (1), IB (1), IIB (6), and III (2). There were 2 local recurrences—R0 resections—both of osteosarcomas of the femur with MSTS classifications IIB and III. 1 patient with local recurrence had a re-resection and is disease-free. The other patient was treated with hip ex-articulation but died of metastatic disease. 1 osteosarcoma patient had proven lung metastasis at the time of surgery and had a local recurrence 1 year later. Figure 6 demonstrates a rotation and joint line check.

Figure 6.

Imageless resection and reconstruction. The CAS tibial guide is used to check the cut angulation and placement of the tibial component. Reconstruction was done with a GMRS/MRH prosthesis, with the CAS system being used for rotation control, joint angulation control, and length reconstruction.

CAS failures

There were 8 failures, including 3 set-up failures for intralesional treatment CAS procedures; these were due to matching error, software failure, and loss of match after set-up. 3 failures in image-based resections were due to to software failure, matching error, or loss of match after set-up on the before-first-use accuracy check. These last 2 failures were both in the ulna and were considered to be due to unstable fixation in this small bone, which was detected during the set-up phase. There were 2 failures in imageless CAS mode for tumor prosthesis placement due to tracker issues: 1 due to loss of accuracy on check because of instability caused by a preoperative pathological fracture, and 1 where it proved impossible to place the trackers inside the software-defined work field.

System use

There were no direct complications and no morbidity related to use of the CAS system. There were no fractures or infections due to the pin placement. All software-reported accuracies were between 0.3 mm and 1.2 mm. Set-up time was measured in the last 47 cases. Mean set-up time was 6.5 (2.3–14) min.

Discussion

Intralesional treatment is currently the standard surgical treatment for CHS-1/ACT lesions and an accepted alternative to resection (Hickey et al. 2011, Campanacci et al. 2013). There is a risk of local recurrence with intralesional treatment. Intraoperative image assistance is normally performed with fluoroscopy. The advantages of CAS over fluoroscopy are mainly real-time 3D feedback and high-resolution images. Both the patient and the surgical team are exposed to ionising radiation during a CAS procedure, and although the exposure is usually low, the effects of long-term multiple low-dosage exposure are unknown (Giordano et al. 2011).

Of 60 successful CAS cases, there was only 1 with an inadequate curettage identified on the baseline MRI and another case with recurrence of grade-1 CHS. The follow-up is short, and longer follow-up is needed for a conclusion on CAS curettage. There were 4 fractures in this treatment group, all in the diaphysis of the femur. We then started routine plating and no more fractures occurred. The main indication where CAS offers additional value with better feedback is large lesions, especially situated in difficult anatomical locations such as the femoral head and pelvis. However, with datasets available CAS can be used as a technologically superior alternative without increased surgical time.

Regarding image-based resection, margin control was good with 40 of 43 R0 resections in the CAS cases. 1 was a soft-tissue R1 margin. The R1 and R2 resections in bone occurred in the first 10 cases. Most procedures were osteochondroma resections, where the system was used to support anatomical orientation. There was 1 local recurrence in an osteosarcoma of the tibia after resection with adequate margins. This recurrence may have been caused by multiple core needle biopsy attempts before referral, as 1 attempt punctured the tumor. R0 margin in pelvic resection was reached in 15 of 17 cases. 1 R1 resection was a soft-tissue margin; CAS was not used for this resection plane. The cause of the R2 resection is unknown. Sometimes it was possible, with careful planning and CAS precision support, to spare structures that would otherwise have had to be sacrificed due to lack of resection plane control using conventional means (Gerbers and Jutte. 2013). This—together with the pelvic resections and procedures for malignant lesions—is the main indication for CAS. Osteochondroma resections have little additional value, except better orientation and instrument position feedback.

In image-based resection and image-based reconstruction, the CAS system served as an objective measurement and guidance tool for the allograft-creation process. The ease with which the allograft could be created made the operation less demanding and more precise. A study of hemicortical resections showed complications, early and late fractures, in 6 of 21 patients, and called for better means of reconstruction (Deijkers et al. 2002). Use of CAS for reconstruction enables highly accurate bony reconstruction with massive hybrid (allogenic and autogenic) bone grafts. This may reduce the risk of complications and enable earlier mobilization. More complex resection and reconstruction shapes were possible, for minimal bone loss. We feel that the most inaccurate step at present in this type of procedure is the inaccuracy of the oscillating saw blade.

There have been reports of the use of CAS with good functional results in imageless resection and imageless reconstructions with custom tumor prostheses (Wong and Kumta 2013). As far as we know, there have been no reports of using imageless CAS in the placement of modular tumor prostheses. CAS can be helpful in accurate planning and measurement of resection length. It can also helpful in joint line reconstruction, as direct feedback on angulation, reconstruction length, and rotation is available in the software. However, no specific implant placement data are yet available to clinically support this improved feedback.

Margin control was excellent, with R0 resections in all 12 oncological procedures. The local recurrence rate for osteosarcoma was 20% (2 out of 10)—which is higher than the recurrence rates of around 10% reported in the literature (Grimer et al. 2005, Picci 2007, Allison et al. 2012). The cause of this is unknown. However, in both cases where local recurrence occurred there was a poor response to chemotherapy, a well-known predictor of local recurrence. Use of CAS most likely does not influence recurrence rate, as this is mostly dependent on soft-tissue margins and response to chemotherapy.

Overall margin control using CAS was excellent. The pathologist reported R0 resections in 59 of 62 resections. 1 of the 3 resections that were not R0 was a soft-tissue R1 margin. Of the 18 high-grade tumor resections, there were 16 adequate bone margins.

Most set-up failures occurred early in the learning curve. Set-up time was measured for the last 47 cases and the mean value was 6.55 min. There were no complications related to CAS.

Due to the large heterogeneity and small number of patients per diagnosis and procedure, limited conclusions can be drawn from these data on clinical outcomes and functional results. Furthermore, there was insufficient follow-up and there were insufficient patient numbers for us to be able to draw conclusions about the recurrence rate.

In summary, CAS appears to be a promising new development in orthopedic oncology. With limb salvage and function-saving surgery, there is a need for accurate navigation. It is also our opinion that CAS can be used in less complex procedures such as image-based resections and curettages too, where it is an accurate, technologically superior, and radiation-free alternative to fluoroscopy.

Acknowledgments

Study conception and design: JG, SB, and PC. Acquisition of data: JG, JP, and PC. Analysis and interpretation of data: JG, MS, JP, and PC. Drafting of manuscript: JG, MS, JP, SB, and PC. Critical revision:JG, MS, JP, SB, and PC.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Allison DC, Carney SC, Ahlmann ER, Hendifar A, Chawla S, Fedenko A, Angeles C, Menendez LR. A meta-analysis of osteosarcoma outcomes in the modern medical era . Sarcoma. 2012;2012:704872. doi: 10.1155/2012/704872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanacci DA, Scoccianti G, Franchi A, Roselli G, Beltrami G, Ippolito M, Caff G, Frenos F, Capanna R. Surgical treatment of central grade 1 chondrosarcoma of the appendicular skeleton . J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14(2):101–7. doi: 10.1007/s10195-013-0230-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartiaux O, Docquier P, Paul L, Francq BG, Cornu OH, Delloye C, Raucent B, Dehez B, Banse X. Surgical inaccuracy of tumor resection and reconstruction within the pelvis: An experimental study . Acta Orthop. 2008;79(5):695–702. doi: 10.1080/17453670810016731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong D, Letson GD. Computer-assisted navigation and musculoskeletal sarcoma surgery . Cancer Control. 2011;18(3):171–6. doi: 10.1177/107327481101800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HS, Oh JH, Han I, Kim HS. The outcomes of navigation-assisted bone tumour surgery: Minimum three-year follow-up . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012;94(10):1414–20. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B10.28638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deijkers RL, Bloem RM, Hogendoorn PC, Verlaan JJ, Kroon HM, Taminiau AH. Hemicortical allograft reconstruction after resection of low-grade malignant bone tumours . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2002;84(7):1009–14. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b7.13032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge SB, Compton CC. The american joint committee on cancer: The 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM . Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471–4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enneking WF, Dunham WK. Resection and reconstruction for primary neoplasms involving the innominate bone . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1978;60(6):731–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbers JG. Jutte PC. Hip-sparing approach using computer navigation in periacetabular chondrosarcoma . Comput Aided Surg. 2013;18(1)(2):27–32. doi: 10.3109/10929088.2012.743587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbers JG, Ooijen P MV, Jutte PC. Computer-assisted surgery for allograft shaping in hemicortical resection: A technical note involving 4 cases . Acta Orthop. 2013;84(2):224–6. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.775045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano BD, Grauer NJ, Miller CP, Morgan TL, Rechtine GR., II Radiation exposure issues in orthopaedics . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011;93(12):1–10. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01328. e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimer RJ, Sommerville S, Warnock D, Carter S, Tillman R, Abudu A, Spooner D. Management and outcome after local recurrence of osteosarcoma . Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(4):578–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey M, Farrokhyar F, Deheshi B, Turcotte R, Ghert M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intralesional versus wide resection for intramedullary grade I chondrosarcoma of the extremities . Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1705–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1532-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeys L, Matharu GS, Nandra RS, Grimer RJ. Can computer navigation-assisted surgery reduce the risk of an intralesional margin and reduce the rate of local recurrence in patients with a tumour of the pelvis or sacrum? . Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(10):1417–24. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B10.31734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picci P. Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma) . Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2(6) doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saidi K. Potential use of computer navigation in the treatment of primary benign and malignant tumors in children . Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2012;5(2):83–90. doi: 10.1007/s12178-012-9124-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So TY, Lam Y, Mak K. Computer-assisted navigation in bone tumor surgery: Seamless workflow model and evolution of technique . Clin Orthop. 2010;468(11):2985–91. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1465-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KC. A practical guide to computer assisted tumor surgery: CATS. Red Corporation Limited. 2010.

- Wong KC, Kumta SM. Joint-preserving tumor resection and reconstruction using image-guided computer navigation . Clin Orthop. 2013;471(3):762–73. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2536-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KC, Kumta S, Chiu K, Antonio G, Unwin P, Leung K. Precision tumour resection and reconstruction using image-guided computer navigation . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007;89(7):943–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]