Abstract

Background and purpose —

The US Food and Drug Administration and the UK Medicines and Health Regulation Agency recommend using MRI in the evaluation of patients with large-diameter metal-on-metal (LD-MoM) hips. Such recommendations do not take into account the relevance of repeated cross-sectional imaging. We therefore investigated the natural course of pseudotumors in patients with LD-MoM hip replacements.

Patients and methods —

Of 888 ASR patients (1,036 hips) 674 patients (798 hips) underwent 2 follow-up visits at our institution. Of these, we identified 124 patients (154 hips) who had undergone repeated clinical assessment including MRI and whole-blood metal ion assessment.

Results —

A change in classification in imaging findings between the 2 MRIs was seen in 17 of the 154 hips (11%). In 13 hips (8%), a significant progression of the pseudotumor was evident, while in 4 (3 %) there was a retrogressive change. 10 of these 13 hips had had a normal first MRI. Patients with a progressive change in the scans did not differ significantly from those without a change in MRI classification regarding follow-up time, time interval between MRIs, or changes in whole-blood Cr and Co levels between assessments.

Interpretation —

A change in classification was rare, considering that all patients had a clinical indication for repeated imaging. Progression of the findings did not appear to correlate clearly with symptoms or whole-blood metal values.

Wear-related adverse soft tissue reactions remain a major concern in patients who have received large-diameter metal-on-metal (LD-MoM) hip replacements. The umbrella term ARMeD (adverse reactions to metal debris) has been proposed to describe all variable manifestations of these reactions (Langton et al. 2010). Intra-capsular findings include metallosis, synovitis, synovial hypertrophy, and capsular necrosis (De Smet et al. 2008, Nishii et al. 2012). In some patients, ARMeD may manifest as an aggressive pseudotumor. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features of pseudotumors adjacent to MoM devices vary greatly (Hart et al. 2012, Hauptfleisch et al. 2012), and there is no consensus regarding the definition of pseudotumor. Pseudotumors appearing partly or fully solid in MRI have been reported to require revision most often (Hauptfleisch et al. 2012). Massive periarticular tissue destruction including osteolysis and tendon avulsion can be found in some of these cases (Fang et al. 2008, Toms et al. 2008, Chang et al. 2012, Hayter et al. 2012). However, occasionally only a thin-walled extracapsular fluid collection adjacent to a MoM hip is detected (Nishii et al. 2012).

The clinical significance of these bursa-like or cystic pseudotumors with typical fluid signals in MRI is not known (Hart el al. 2012, Nishii et al. 2012). This type of soft-tissue lesion has been reported in several papers in recent years, and some authors consider them to be pseudotumors (Hart et al. 2012, Hauptfleischet al. 2012). However, these lesions have also been described in patients with metal-on-polyethylene and ceramic-on-ceramic hips (Carli et al. 2011, Mistry et al. 2011). The natural history of these lesions is, however, largely unknown.

Both the US Food and Drug Administration and the UK Medicines and Health Regulation Agency recommend using MRI in the evaluation of patients with LD-MoM hips (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulation Agency 2012, U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2012). Recommendations do not take into account the relevance of repeated cross-sectional imaging. In a recent study, no relevant changes were seen after 1 year in 14 hips with a pseudotumor using repeated MR imaging (van der Weegen et al. 2013). In a larger study, progression in MRI was seen in 15 of 103 MoM 28-mm total hip replacements (THRs) (Ebreo et al. 2013).

Our main aims were (1) using MRI, to investigate the natural course of pseudotumors in patients with LD-MoM hip replacements who did not require revision surgery, and (2) to determine whether any new pseudotumors emerged in this cohort during the follow-up. A secondary aim was to document the temporal changes in these patients regarding MRI findings, clinical outcomes, and whole-blood chrome (Cr) and cobalt (Co) levels.

Materials and methods

Screening program

After the medical device alert from the MHRA (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulation Agency 2012) regarding ASR hip resurfacings and ASR XL total hip replacements, we established a screening protocol to identify possible articulation-related complications in patients who had received either of these implants at our institution. The screening protocol has already been described in detail (Reito et al. 2013). In short, all patients received an Oxford hip score questionnaire, underwent physical examination at our outpatient clinic, and were also referred for whole-blood metal ion (chrome and cobalt) measurements, plain hip radiographs, and cross-sectional imaging. Our primary imaging modality was MRI. Ultrasound scanning (USS) was used if MRI was contraindicated or if the patient suffered from claustrophobia.

Indications for repeated MRI

The indications for repeated MRI are listed in Table 3. Asymptomatic patients without any abnormal findings in primary MRI or USS, with whole-blood metal ion levels of less than 5 ppb, and who were also asymptomatic, were assigned for regular follow-up visits at 1- to 2-year intervals. These patients had physical examination and plain radiographs together with whole-blood metal ion analysis routinely repeated at each follow-up visit. If either whole-blood Cr or Co exceeded 5 ppb or the patient had become symptomatic, cross-sectional imaging was repeated. Borderline cases, i.e. patients with some abnormal findings (e.g. slightly elevated blood metal ions without any other findings) were scheduled for re-evaluation in 6–12 months. In most of these patients, both whole-blood metal ion measurement and cross-sectional imaging were repeated at the time of the re-evaluation. Moreover, repeated imaging was also done in some patients who had been scheduled for revision in order to update the current status of soft-tissue masses and to investigate their dimensions before revision surgery.

Table 3.

Indications for the repeated MR imaging and results of the primary and repeated MRIs. Other reasons included control imaging due to scheduled revision (8 hips), enchondroma (2 hips), squeaking hip (2 hips), suspicion of latent infection (2 hips), joint effusion in primary MRI (1 hip), and occurrence of palpable lump in lateral thigh (1 hip). 1 patient who had both HR and THR is not shown in the table

| Progressive change in classification |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR patients |

THR patients |

HR patients |

THR patients |

||||||

| Indication for repeated imaging | Unilateral | Bilateral | Unilateral | Bilateral | Unilateral | Bilateral | Unilateral | Bilateral | |

| Control imaging due to elevated | |||||||||

| Co and/or Cr | 5 | 2 | 15 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Occurrence of pain during follow-up | 13 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Control imaging to due increase | |||||||||

| (> 5 ppb) in Co and/or Cr | 2 | 1 | 22 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | |

| Control imaging due to pseudotumor | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Occurrence of pain and elevated | |||||||||

| metal ions during follow-up | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Control imaging due to presence of pain | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 3 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 30 | 11 | 64 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 5 | |

Cross-sectional imaging

In the early phases of the screening program, all MRI findings were evaluated prospectively by a musculoskeletal radiologist using a modified Norwich classification (Anderson et al. 2011). Since September 2012, we have used the Imperial classification in the evaluation of MRIs (Hart et al. 2012). Furthermore, all MRIs performed before September 2012 were also re-classified retrospectively by the same radiologist using the Imperial classification. The locations of the pseudotumors were categorized—based on their anatomical location—as being either trochanteric (posterior) or iliopsoatic (anterior).

Study population

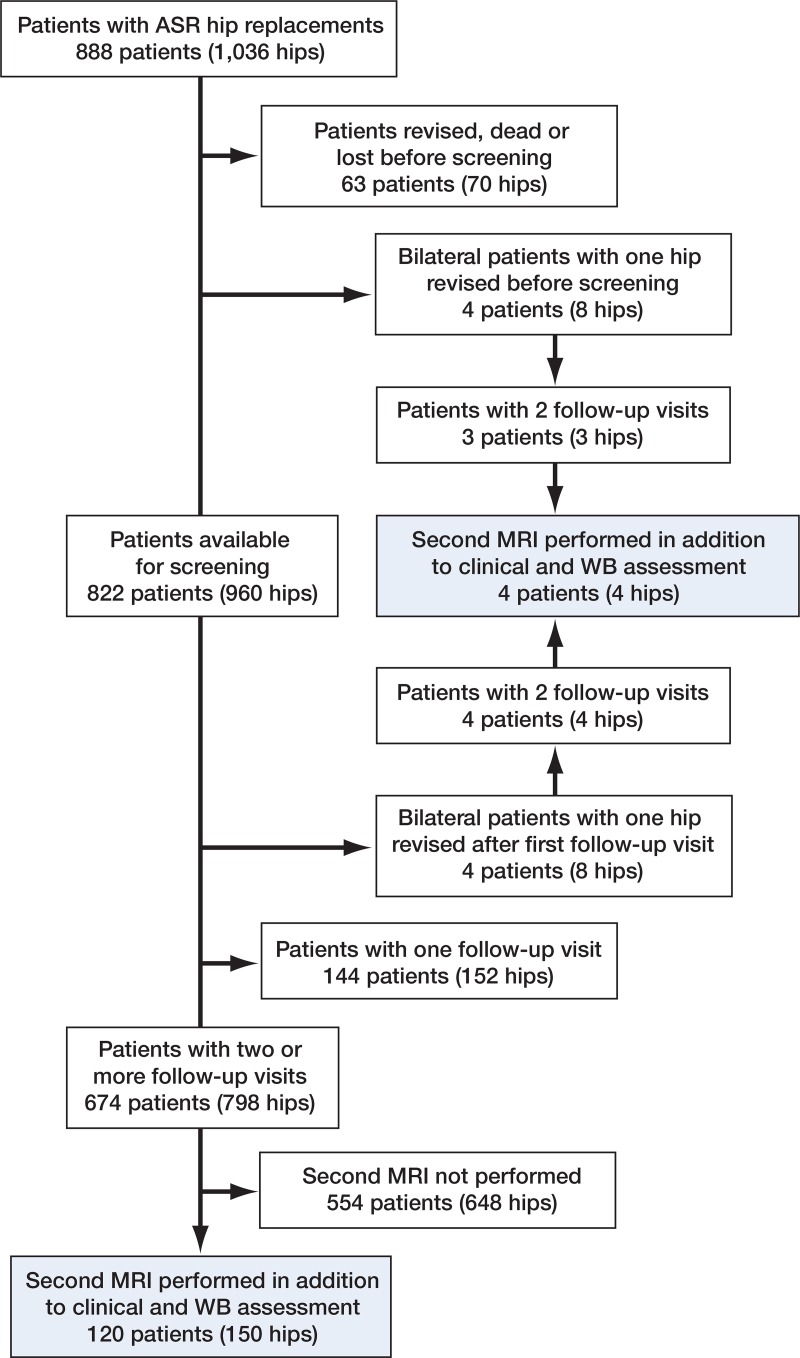

For the purposes of the present study, we identified all ASR patients who had had 2 complete follow-up visits at our institution after initiation of the screening program (including Harris hip score (HHS) and whole-blood metal ion measurements). Of the 888 ASR patients (1,036 hips), 63 (70 hips) were lost to follow-up, had died, or had been revised before the screening was initiated (Figure 1). 144 patients (152 hips) had had only 1 follow-up visit. 76 patients (76 hips) had been revised, 5 patients had died (5 hips), and 18 patients (22 hips) were lost to follow-up after the first visit. In 45 patients (51 hips), the second follow-up visit had been postponed beyond 3 years and they had not yet had it, while 674 patients (798 hips) had had 2 follow-up visits.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the patients

Statistics

For each patient, the indication for repeated MR imaging was recorded. Patient demographics and whole-blood metal ion levels were also recorded. Time from index operation to the first MRI and time between the MR imagings were calculated. None of the study variables were normally distributed, so non-parametric tests were implemented. Mann-Whitney test was used to assess differences between groups. The Wilcoxon signed rank sum test was used to compare 2 consecutive metal ion measurements from the same patient. Chi-square test was used to analyze differences in proportions between groups. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for proportions were established using the Wilson method with Confidence Interval Analysis (CIA) software v.2.2.0 (University of Southampton, UK). Other statistical analyses were done using IBM Statistics v.19.0. Significance was set to 0.05.

Results

We identified 124 patients who had undergone repeated clinical assessment including MRI and whole-blood metal ion assessment (154 hips). There were 90 unilateral patients, 30 bilateral patients, and 4 patients who had had their other hip revised before the second follow-up visit (Table 1). Median values of HHS and whole-blood metal ion levels at the time of the imaging are given in Table 2. Median follow-up time before the first MRI was 3.8 (1.5–7.3) years for the whole cohort. Median time between the 2 MRIs was 19 (4.8–32) months for the whole cohort.

Table 1.

Demographics of the patients

| No. of patients (hips) | 124 (154) |

| No. of males (male hips) | 78 (97) |

| No. of females (female hips) | 46 (57) |

| No. of implants | |

| ASR XL THR | 101 |

| ASR hip resurfacing | 53 |

| Median femoral diameter, mm (range) | |

| ASR XL THR | 51 (41–59) |

| ASR hip resurfacing | 51 (43–59) |

Table 2.

Median clinical outcome scores and whole-blood (WB) metal ion levels at the first and second clinical evaluations

| First examination | Second examination | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| THR patients | |||

| HHS (range) | |||

| Unilateral | 98 (63–100) | 94 (62–100) | 0.08 |

| Bilateral, right | 96 (51–100) | 86 (36–100) | 0.4 |

| Bilateral, left | 98 (51–100) | 86 (36–100) | 0.2 |

| WB Cr (range), ppb | |||

| Unilateral | 2.1 (0.8–11) | 2.6 (0.6–10) | 0.06 |

| Bilateral | 3.0 (1.2–13) | 3.3 (0.8–15) | 0.4 |

| WB Co (range), ppb | |||

| Unilateral | 4.6 (0.8–28) | 5.8 (0.8–32) | 0.001 |

| Bilateral | 9.4 (1.7–29) | 9.6 (1.5–30) | 0.3 |

| HR patients | |||

| HHS (range) | |||

| Unilateral | 86 (59–100) | 86 (59–100) | 0.4 |

| Bilateral, right | 90 (66–100) | 94 (84–100) | 0.7 |

| Bilateral, left | 84.5 (65–100) | 92 (62–100) | 0.5 |

| WB Cr (range), ppb | |||

| Unilateral | 2.7 (1.0–16) | 2.9 (0.6–9.3) | 0.7 |

| Bilateral | 2.8 (1.4–14) | 2.7 (1.0–15) | 0.3 |

| WB Co (range), ppb | |||

| Unilateral | 3.2 (0.8–128) | 3.3 (0.8–47) | 0.8 |

| Bilateral | 2.3 (1.1–9.5) | 2.5 (1.0–23) | 0.1 |

Indications for the repeated MRIs are listed in Table 3. A change in classification in imaging findings between the 2 MRIs was seen in 17 of the 154 hips (11%, CI: 7–17). In 13 hips (8%, CI: 5–14)—13 patients (10%, CI: 6–17)—a significant progression of the pseudotumor was evident, while in 4 hips (3%, CI: 0.1–7)—4 patients (3%, CI: 0.1–8)—there was a retrogressive change. 6 of the patients with unilateral THR (9%, CI: 3–12) had a progressive change and 5 of the 18 patients with bilateral THR (28%, CI: 8–36) had a progressive change (Table 4). 11 of the 13 patients with significant pseudotumor progression had THR and only 2 had HR. Patients with a progressive change in the scans were not significantly different from those without a significant change in MRI regarding follow-up time, time interval between MRIs, and changes in whole-blood Cr and Co levels between assessments (Table 3). Due to the small number of HR patients with progressive change, we only analyzed the THR group.

Table 4.

Comparison of clinical variables between patients with a significant imaging change and those without any change

| Patients with no change in MRI | Patients with a progressive change in MRI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | ||||

| Unilateral | 54 | 6 | 0.1 a | |

| Bilateral | 13 | 5 | ||

| Years until first MRI | b | |||

| Unilateral | 3.5 (1.5–6.4) | 3.6 (2.3–6.1) | 0.5 | |

| Bilateral | 4.3 (1.8–6.1) | 3.2 (3.0–6.8) | 0.6 | |

| Months between imagings b | ||||

| Unilateral | 21 (4.8–29) | 18 (13–30) | 0.8 | |

| Bilateral | 22 (8.2–32) | 12 (12–25) | 0.3 | |

| Change in WB Co, ppb b | ||||

| Unilateral | 0.95 (–7.8 to 12) | 2.25 (–4.1 to 3.8) | 0.4 | |

| Bilateral | 0.60 (–15 to 16) | –0.35 (–0.90 to 1.2) | 0.4 | |

| Change in WB Cr, ppb b | ||||

| Unilateral | 0.1 (–2.2 to 1.7) | 0.35 (–0.8 to 2.3) | 0.3 | |

| Bilateral | 0.4 (–3.3 to 2.1) | 0.15 (–0.4 to 0.30) | 0.5 |

a For prevalences

b Values are median (range)

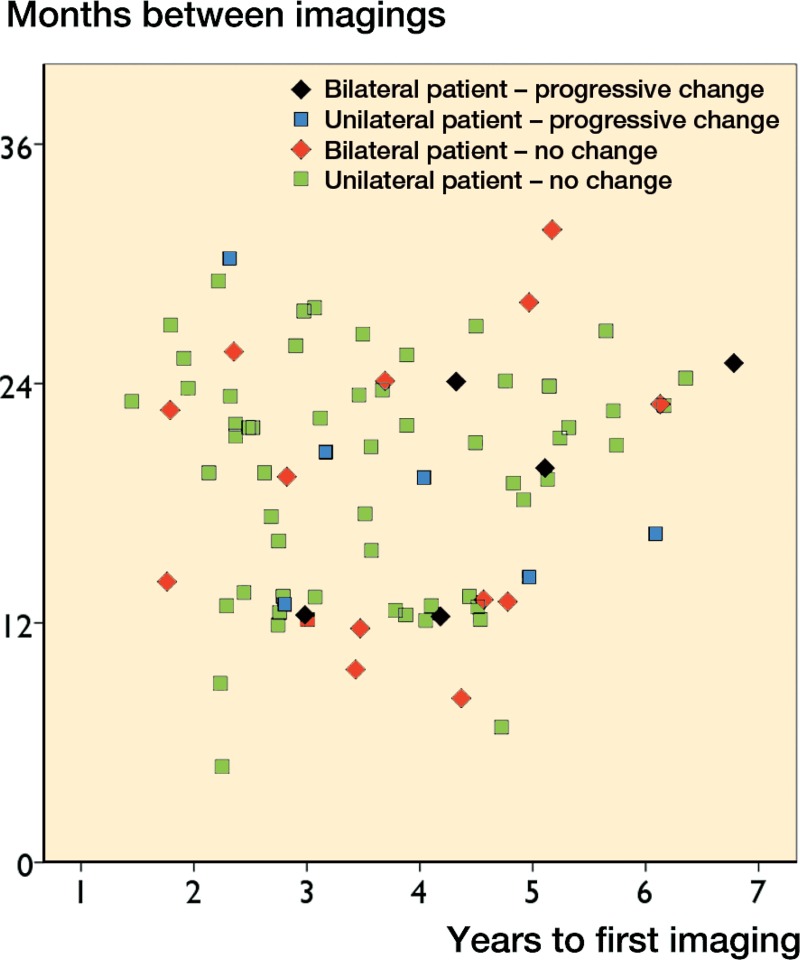

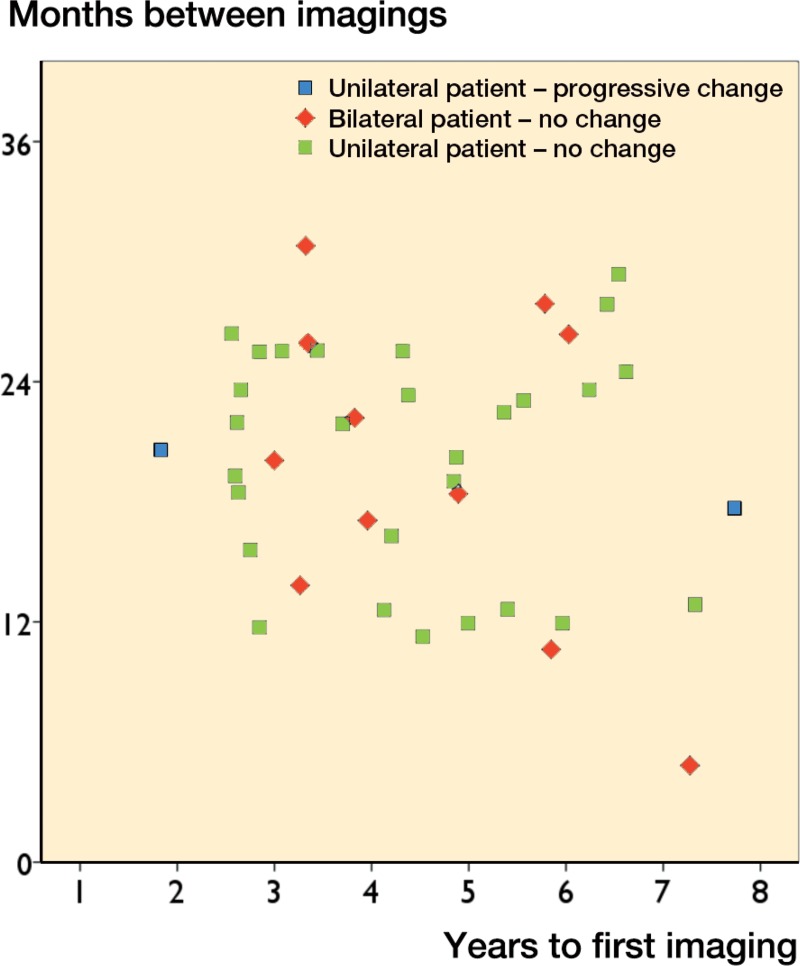

10 of the 13 hips with significant pseudotumor progression had a normal first MRI (Table 5). 7 of them revealed a cystic pseudotumor (PT) of class 1 and 3 a thick-walled PT of class 2 in the second scan. In 3 hips, a thin-walled cystic PT (class 1) had developed into a thick-walled one (class 2A or 2B) in the second MRI. In 4 hips with retrogressive change, a cystic PT (class 1) seen in the first MRI could not be seen any more in the second MRI. There was no significant change in any of the 13 patients (18 hips) in which the second MRI was done less than 12 months after the first one (Figures 2 and 3). 20 THR patients (21 hips) had a follow-up time of less than 2.5 years before the first MRI. A significant change in the second MRI was only seen in 1 of these patients (5%, CI: 0–15). In the HR group, only 1 patient who had a progression had a follow-up time of less than 2.5 years. Most of the significant changes were seen in MRIs performed 1–2 years after the initial MRI, or more than 3 years from the primary operation (Figures 4 and 5).

Table 5.

Contingency table showing MRI findings

| Second MRI |

First MRI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2A | 2B | Total | ||

| First MRI | 0 | 109 | 7 a | 1a | 2a | 119 |

| 1 | 4 c | 20 | 1 b | 2 b | 27 | |

| 2A | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| 2B | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Second MRI | Total | 113 | 27 | 7 | 7 | 154 |

10 of the 13 patients with a progressive change had a normal first scan.

In 3 hips, a thin-walled cystic pseudotumor had developed into a thick-walled pseudotumor in the repeat MRI.

In 4 hips with retrogressive change, an originally diagnosed pseudotumor could not be seen in the repeat MRI.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of follow-up time until first MRI against time interval between MRIs in the THR group.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of follow-up time until first MRI against time interval between MRIs in the HR group.

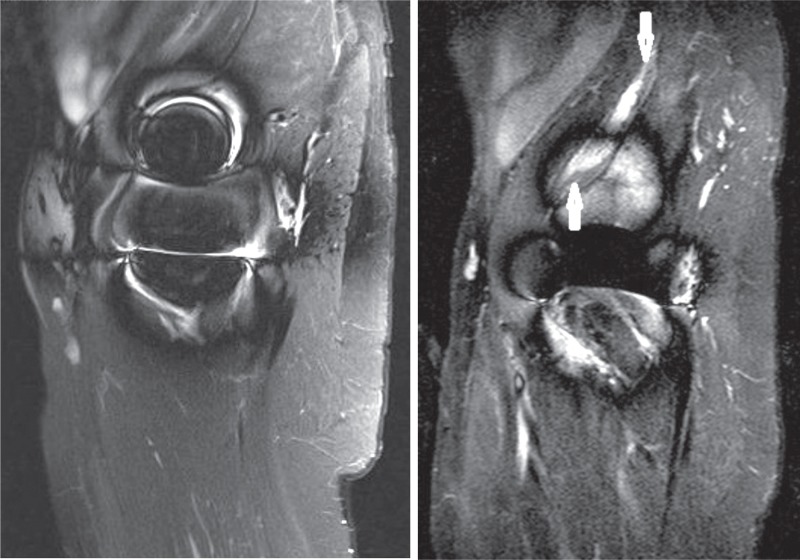

Figure 4.

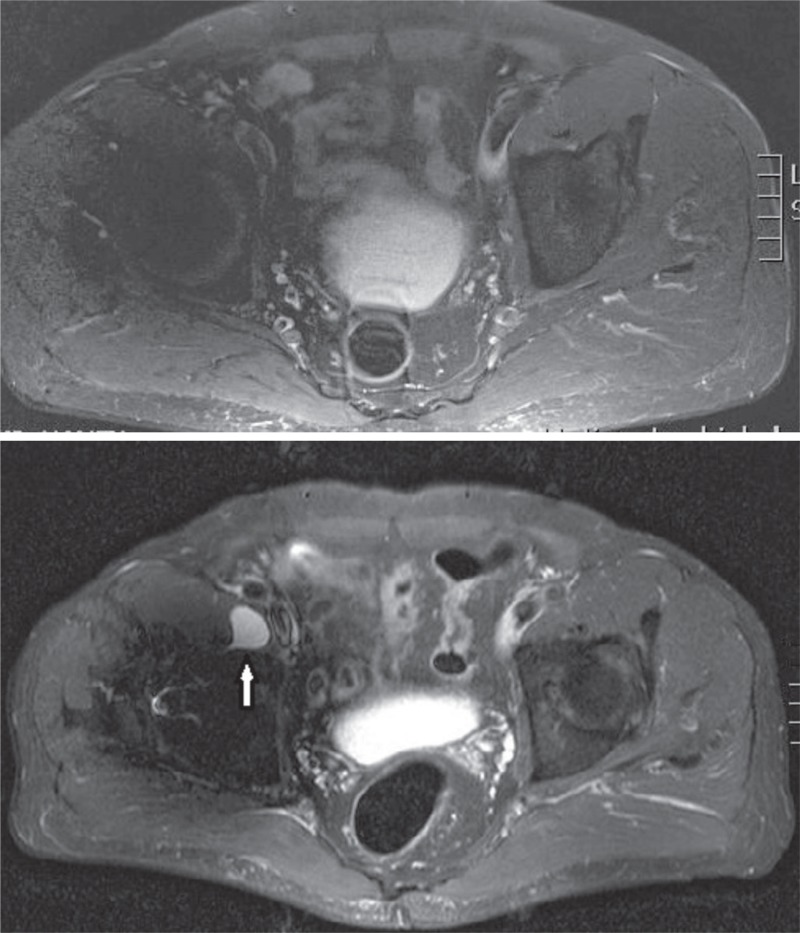

Man aged 41 at the time of the index operation for ASR HR. Time to first MRI (left) was 7.7 years. The time elapsed between imagings was 18 months. Both times, whole-blood Co and Cr remained below 4 ppb. MRI was repeated as a control imaging in the annual follow-up visit due to joint effusion seen in the first scan. However, development of a type-2A pseudotumor was seen.

Figure 5.

A man with ASR XL THR who was 69 years old at the index operation. Time to first MRI (top) was 2.3 years. The time elapsed between imagings was 2.5 years. Both times, whole-blood Cr remained below 4 ppb. Whole-blood Co increased from 7.2 ppb to 16 ppb. MRI was repeated due to increase in whole-blood Co levels and occurrence of stiffness in the operated hip. Control imaging revealed a newly formed cystic lesion (type 1).

Cystic PTs (class 1) were mostly located in the trochanteric area in both MRIs (p = 0.002 for the first MRI, and p < 0.001 for the second MRI).

Discussion

The use of metal-on-metal bearings has decreased substantially in recent years due to increasing numbers of adverse soft-tissue reactions (Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry 2013, National Joint Registry for England and Wales 2013). Both preoperative and perioperative findings—macroscopic and microscopic—in patients diagnosed with ARMeD have been documented by several authors (De Smet et al. 2008, Browne et al. 2010, Langton et al. 2010). A major issue regarding ARMeD is the lack of knowledge regarding the natural history of these lesions. Furthermore, the relevance and clinical implications of repeated MRI in patients with MoM hip replacements is unknown. We therefore studied the natural history of pseudotumors in patients with LD-MoM hip replacements, whether any new pseudotumors emerged during follow-up, and what factors, if any, would predict progression of these lesions. Also, the possible relationship between the imaging findings and symptoms and whole blood metal ion levels was studied.

We acknowledge that our study had a few limitations. Firstly, median time from index operation to the first imaging was 4.7 years. There were only a few patients with a follow-up time of less than 2 years. This would have resulted in selection bias. We assume that especially patients susceptible to ALVAL (aseptic lymphocytic vasculitis-associated lesions), who had developed an aggressive pseudotumor early, may have been revised at an early stage and would not have been available for second MRI. However, longitudinal imaging in patients with an aggressive and symptomatic pseudotumor may not even be relevant, since these cases do not represent a diagnostic dilemma. Moreover, repeated imaging may be more relevant in borderline cases, such as those with a thin-walled cystic lesion, those who have become symptomatic during follow-up, or those in whom increasing blood metal ion levels are seen. Secondly, the MRI results were analyzed only once and by only 1 observer, so the intra- and interobserver reliability remains unknown.

The clinical significance of thin-walled fluid collections with typical MRI fluid signals is unknown. Recently, this kind of soft tissue lesion has been reported around MoM hips in several papers, and some authors consider them to be pseudotumors (Hart et al. 2012, Hauptfleisch et al. 2012). However, similar lesions have also been described in patients with metal-on-polyethylene and ceramic-on-ceramic hips (Carli et al. 2011, Mistry et al. 2011). An unknown aspect of these fluid collections is their possible progression to thick-walled pseudotumors with atypical fluid signals, or to solid masses, which may cause massive soft-tissue destruction. We observed a thin-walled fluid collection in 27 hips in the first MRI. In most of these cases (20 of 27), the second MRI did not reveal any significant change. In 3 hips, the lesion had progressed to a thick-walled one, and in 4 hips the thin-walled lesion seen in the first MRI could no longer be seen in the second MRI.

Our results show that some of the thin-walled fluid collections changed with time. Some of them clearly progressed to a thick-walled pseudotumor, while others resolved. Fluid collections unrelated to the hip joint may be signs of local inflammation in the bursa. However, in cases with pseudotumor-like progression, the joint space may have become adjacent to the enlarged bursa and the wear debris may have caused pseudotumor tissue formation in the bursa. Based on MRI findings alone, it is often difficult to decide whether the lesion is only an inflamed bursa or a thin-walled pseudotumor with the potential to progress and cause soft-tissue destruction.

To our knowledge, results of repeated MRIs and longitudinal findings in patients with MoM hip replacements have only been reported in 2 publications. Ebreo et al. (2013) stated that late development or progression of soft-tissue lesions is uncommon in patients with a small-head (28-mm) MoM THR. In the present study, most changes appeared between 12 and 24 months of the first MRI. Thus, this may be the most beneficial time interval for repeated MR imaging. The proportion of hips in which development or progression of an extra-capsular soft-tissue reaction was seen in the repeated MRI scan was remarkably similar in the study by Ebreo et al. and in the present study (11% and 15%, respectively). In the study by Ebreo et al., median time to first MRI (over 5 years) was longer than that in our series (3.8 years). Van der Weegen et al. (2013) found that asymptomatic pseudotumors showed little or no variation over 1 year. Their study was case-control in nature, so the prevalence of change cannot be derived from it. Ebreo et al. did not report the indications for repeated MRI and they—along with van der Weegen et al.—used the Norwich classification for MRI findings, whereas we used the Imperial classification (Sabah et al. 2011, Hart et al. 2012). The Norwich classification does not distinguish between cystic lesions and thick-walled pseudotumors, so the results are not entirely comparable (Anderson et al. 2011).

Most of the hips without any abnormal soft-tissue lesions in the primary MRI also had normal findings in the second MRI. In these patients, only 1 thick-walled pseudotumor could be found in the second MRI. Based on this finding, routine re-scanning of patients without any abnormal soft-tissue lesions in the first MRI does not appear to be justified. But how do we find the patients who are prone to progression of cystic lesions, or to development of new lesions? 29 patients were re-imaged due to increasing hip pain, and 7 patients due to persistent hip pain. The second MRI did not reveal any new thick-walled pseudotumors in these patients. In 60 patients with repeatedly or newly elevated whole-blood metal ion levels (> 5 ppb), the second MRI revealed development of a new thick-walled pseudotumor in 3 patients and a new thin-walled lesion in 6 patients. Thus, progression was seen in 15% of the cases that were re-imaged due to elevated blood metal ion levels.

The current guidelines regarding surveillance of patients with MoM implants do not take a stance on the role of repeated cross-sectional imaging (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulation Agency 2012, U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2012). In the present study, 154 hips underwent repeated MR imaging. In 13 hips, a significant change—i.e. development of a new soft-tissue lesion or progression of the lesion seen in the first MRI—was observed. Thus, a significant change was rare, considering that all patients had a clinical indication for repeated imaging. Our results confirm an earlier conclusion that repeated MRI offers little or no new information if it is performed less than 1 year after the first MRI, or with follow-up of less than 3.5 years from the primary operation (van der Weegen et al. 2013). Moreover, repeat MRI appears to be less useful in patients with HR. Furthermore, routine re-scanning of patients with no soft-tissue findings in the primary MRI does not appear to be beneficial. How to choose the patients for re-scanning remains a clinical problem, since progression of the findings does not appear to correlate clearly with symptoms or whole-blood metal ion values, although change in imaging findings was more prevalent in the latter group. Further studies to answer this question are warranted, and especially to study the exact clinical relevance and behavior of cystic lesions seen around MoM hips, to fully understand the clinical implications of our findings.

Acknowledgments

All the authors participated in the study design. AR performed data recording and statistical analysis. PE performed the MRI analyses. AR wrote the manuscript and all the other authors participated in critical evaluation of and commenting on the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Anderson H, Toms AP, Cahir JG, Goodwin RW, Wimhurst J, Nolan JF. Grading the severity of soft tissue changes associated with metal-on-metal hip replacements: reliability of an MR grading system . Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:303–7. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-1000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report 2013 2013 https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au/annual-reports-

- Browne JA, Bechtold CD, Berry DJ, Hanssen AD, Lewallen DG. Failed metal-on-metal hip ar-throplasties: a spectrum of clinical presentations and operative findings . Clin Orthop. 2010;468:2313–20. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1419-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli A, Reuven A, Zukor DJ, Antoniou J. Adverse soft-tissue reactions around non-metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty - a systematic review of the literature . Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis (Suppl 1) 2011;69:S47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EY, McAnally JL, Van Horne JR, et al. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: Do symptoms correlate with MR imaging findings? . Radiology. 2012;265:848–57. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet K, De Haan R, Calistri A, et al. Metal ion measurement as a diagnostic tool to identify problems with metal-on-metal hip resurfacing . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 4) 2008;90:202–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebreo D, Bell PJ, Arshad H, Donell ST, Toms A, Nolan JF. Serial magnetic resonance imaging of metal-on-metal total hip replacements. Follow-up of a cohort of 28 mm Ultima TPS THRs . Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:1035–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B8.31377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CS, Harvie P, Gibbons CL, Whitwell D, Athanasou NA, Ostlere S. The imaging spectrum of peri-articular inflammatory masses following metal-on-metal hip resurfacing . Skeletal Radiol. 2008;3(7):715–22. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0492-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AJ, Satchithananda K, Liddle AD, et al. Pseudotumors in association with well-functioning metal-on-metal hip prostheses: a case-control study using three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012;94:317–25. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauptfleisch J, Pandit H, Grammatopoulos G, Gill HS, Murray DW, Ostlere S. A MRI classifica-tion of periprosthetic soft tissue masses (pseudotumors) associated with metal-on-metal resurfacing hip arthroplasty . Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:149–55. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayter CL, Gold SL, Koff MF, et al. MRI findings in painful metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty . AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:884–93. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton DJ, Jameson SS, Joyce TJ, Hallab NJ, Natu S, Nargol AV. Early failure of metal-on-metal bearings in hip resurfacing and large-diameter total hip replacement: A consequence of ex-cess wear . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92:38–46. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B1.22770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulation Agency Medical Device Alert: All metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacements (MDA/2012/036) http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/dts-bs/documents/medicaldevicealert/con155767.pdf .

- Mistry A, Cahir J, Donell ST, Nolan J, Toms AP. MRI of asymptomatic patients with metal-on-metal and polyethylene-on-metal total hip arthroplasties . Clin Radiol. 2011;66:540–5. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 10th Annual Report 2013 http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/NjrCentre/Portals/0/Documents/England/Reports/10th_annual_report/NJR%209th%20Annual%20Report%202013.pdf .

- Nishii T, Sakai T, Takao M, Yoshikawa H, Sugano N. Ultrasound screening of periarticular soft tissue abnormality around metal-on-metal bearings . J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:895–900. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reito A, Puolakka T, Elo P, Pajamaki J, ja Eskelinen A. High prevalence of adverse reactions to metal debris in small-headed ASR hips . Clin Orthop. 2013;471(9):2954–61. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabah SA, Mitchell AW, Henckel J, Sandison A, Skinner JA, Hart AJ. Magnetic resonance imag-ing findings in painful metal-on-metal hips: a prospective study . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:71–6. e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.11.008. 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toms AP, Marshall TJ, Cahir J, Darrah C, Nolan J, Donell ST, Barker T, Tucker JK. MRI of early symptomatic metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective review of radiological findings in 20 hips . Clin Radiol. 2008;63:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration Metal-on-Metal Hip Implants. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/MetalonMetalHipImplants/

- van der Weegen W, Brakel K, Horn RJ, et al. Asymptomatic pseudotumors after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing show little change within one year . Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:1626–31. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B12.32248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]